AMN Hybrid Models: Revolutionizing Metabolic Prediction for Drug Development with AI

Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN) hybrid models represent a transformative approach in systems biology, integrating mechanistic Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) with machine learning to overcome the limitations of traditional constraint-based methods.

AMN Hybrid Models: Revolutionizing Metabolic Prediction for Drug Development with AI

Abstract

Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN) hybrid models represent a transformative approach in systems biology, integrating mechanistic Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) with machine learning to overcome the limitations of traditional constraint-based methods. This article provides a comprehensive exploration for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of AMNs, their core methodology and applications in predicting metabolic fluxes and gene knockout phenotypes, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance, and a rigorous validation against established techniques. By synthesizing current research and real-world applications, this content serves as a critical resource for leveraging AMNs to enhance predictive accuracy in metabolic engineering and precision medicine, ultimately accelerating therapeutic discovery.

The Genesis of AMNs: Bridging Mechanistic Models and Machine Learning for Superior Metabolic Insight

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) stands as a cornerstone mathematical approach within constraint-based modeling for understanding metabolite flow through biochemical systems. By utilizing a numerical matrix of stoichiometric coefficients from genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), FBA defines a solution space bounded by physicochemical constraints. From this space, an optimization function identifies the specific flux distribution that maximizes a biological objective—such as biomass production or metabolite synthesis—while satisfying all imposed constraints [1]. A foundational assumption of traditional FBA is that the metabolic system operates under steady-state conditions, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time because production and consumption rates are balanced [1]. Although FBA is computationally efficient and avoids the need for difficult-to-measure kinetic parameters, this and other inherent simplifications introduce significant limitations that this application note will explore in detail, framing them within the emerging context of Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN) hybrid models.

Fundamental Limitations of Traditional FBA

Traditional FBA, while powerful, faces several critical challenges that impede its predictive accuracy and biotechnological application.

Objective Function Selection and Quantitative Predictive Power

A primary weakness of FBA is its strong dependence on the chosen objective function. Conventional applications often assume a single objective, such as maximizing biomass or the production of a target metabolite [2] [1]. However, cells dynamically adjust their metabolic priorities in response to environmental changes, and a static objective fails to capture this adaptive behavior [2]. This often leads to inaccurate quantitative predictions of growth rates or metabolic fluxes. As highlighted in a recent perspective, "FBA suffers from making accurate quantitative phenotype predictions" without labor-intensive measurements of uptake fluxes to constrain the model [3]. Furthermore, selecting an inappropriate objective can yield physiologically irrelevant flux distributions. For instance, optimizing solely for L-cysteine export in E. coli predicts solutions with zero biomass growth, a scenario that does not reflect realistic culture conditions [1].

Oversimplification of Biological Constraints

Traditional FBA often predicts unrealistically high metabolic fluxes because its solution space is constrained only by stoichiometry and simple flux bounds. It lacks inherent constraints to represent enzyme kinetics, thermodynamic feasibility, or cellular resource allocation [1]. This oversight becomes particularly problematic in strain design, where engineered enzymes with modified catalytic rates (Kcat values) can drastically alter metabolic flux distributions in ways traditional FBA cannot anticipate [1]. The assumption of steady-state conditions further limits FBA's application to dynamic biological processes or engineered systems designed for time-dependent functions, such as metabolite-triggered genetic circuits [1].

Table 1: Core Limitations of Traditional FBA and Their Experimental Implications

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Model Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Function | Static, single objective [2] | Fails to capture shifting cellular priorities; reduces quantitative accuracy [3] |

| Biological Constraints | Lack of enzyme kinetics [1] | Predicts unrealistically high, non-physiological flux values |

| Biological Constraints | Ignoring thermodynamic feasibility [4] | Permits thermodynamically infeasible flux distributions |

| System Dynamics | Steady-state assumption [1] | Unable to model transient or dynamic cellular processes |

| Data Integration | Inability to leverage multi-omics data [5] | Model remains uninformatted by rich genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets |

The Challenge of Multireaction Dependencies

Metabolism is governed by physico-chemical constraints that create complex dependencies among multiple reactions. Recent research has revealed that metabolic networks harbor functional relationships that extend beyond simple reaction pairs [4] [6]. The concept of a "forcedly balanced complex"—a set of metabolites where the sum of incoming fluxes must equal the sum of outgoing fluxes when an additional constraint is imposed—illustrates these multi-reaction dependencies. Manipulating these complexes can have significant functional consequences; for example, certain forcedly balanced complexes are lethal in models of specific cancer types but have minimal effect on healthy tissue models [4] [6]. Traditional FBA frameworks are not designed to systematically identify or exploit these higher-order dependencies, representing a significant gap in our ability to manipulate metabolic networks for biotechnological or therapeutic goals.

The Paradigm Shift: Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN) Hybrid Models

To overcome these limitations, a new paradigm combines mechanistic modeling with machine learning (ML) to create hybrid models. These models leverage the strengths of both approaches: the structured, knowledge-driven framework of mechanistic models and the pattern recognition and predictive power of ML trained on experimental data [3] [5] [7].

Architecture and Workflow of AMN Hybrid Models

The core innovation of AMN hybrid models is the embedding of a mechanistic metabolic model within a trainable neural network architecture. This design allows for gradient backpropagation, enabling the model to learn from data while adhering to biochemical constraints [3]. The workflow typically involves:

- A trainable neural layer that processes input conditions (e.g., medium composition, gene knockouts) to predict uptake flux bounds or initial flux vectors [3] [5].

- A mechanistic solver layer that computes a steady-state flux distribution satisfying the stoichiometric constraints of the GEM. This replaces the traditional simplex solver with differentiable alternatives (e.g., Wt-solver, LP-solver, QP-solver) to enable end-to-end training [3].

- A hybrid training process where the model is trained to minimize the difference between its predicted fluxes and experimentally measured fluxes, while simultaneously respecting the fundamental constraints imposed by the metabolic network [3] [5].

Benchmarking Performance Against Traditional FBA

Hybrid models like the Neural-Mechanistic model and the Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN) have demonstrated systematic outperformance of traditional constraint-based models. Key advantages include:

- Superior Predictive Accuracy: Hybrid models achieve significantly better agreement with experimental flux data across different media and gene knockout conditions [3] [5].

- Data Efficiency: These models require training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than classical machine learning methods, effectively tackling the "curse of dimensionality" by incorporating mechanistic constraints [3].

- Multi-omics Integration: Frameworks like MINN seamlessly integrate transcriptomic or proteomic data directly into flux predictions, a task that is challenging for traditional FBA [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AMN Development

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Function in AMN Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Mechanistic Model | Provides stoichiometric constraints; defines network topology | iML1515 (E. coli) [3] [1] |

| Differentiable Solver | Computational Method | Replaces simplex solver; enables gradient backpropagation | Wt-solver, LP-solver, QP-solver [3] |

| Enzyme Kinetics Data | Model Constraint | Caps fluxes based on enzyme availability & catalytic turnover | Kcat values from BRENDA [1] |

| Experimental Flux Data | Training Data | Ground truth for training and validating hybrid models | 13C-MFA flux distributions [8] [3] |

| Pathway Analysis Tool | Analytical Framework | Identifies critical pathways & computes coefficients of importance | TIObjFind [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Basic AMN Hybrid Model

This protocol outlines the core steps for constructing an AMN that integrates a GEM with a neural network for flux prediction [3].

Step 1: Problem Formulation and Data Preparation

- Define the prediction task (e.g., growth rate or flux distribution under different media or gene KOs).

- Compile a training set of paired input conditions (e.g., carbon source, gene essentiality) and output experimental flux data or FBA-simulated fluxes.

- Normalize all input and output data to ensure stable neural network training.

Step 2: Model Architecture Implementation

- Input Layer: Design to accept your defined condition features.

- Neural Pre-processing Layer: Implement a fully connected neural network to map input conditions to an initial flux vector (Vâ‚€) or uptake flux bounds (V_in).

- Mechanistic Layer: Embed a differentiable solver (e.g., the QP-solver) that takes the output of the neural layer and computes a steady-state flux distribution (V_out) constrained by the stoichiometric matrix of the GEM.

Step 3: Model Training and Validation

- Define a custom loss function that combines a data fidelity term (e.g., Mean Squared Error between predicted V_out and experimental fluxes) and a constraint satisfaction term.

- Use an optimizer (e.g., Adam) to minimize the loss function, iteratively updating the weights of the neural network.

- Validate the trained model on a held-out test set of conditions to assess its generalizability and compare its performance against traditional FBA.

Protocol 2: Integrating Multi-omics Data with a Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN)

This protocol extends the basic AMN to incorporate transcriptomic or proteomic data for enhanced flux prediction [5].

Step 1: Data Collection and Pre-processing

- Obtain a dataset pairing gene expression (transcriptomics) or protein abundance (proteomics) with corresponding measured metabolic fluxes (e.g., from 13C-MFA).

- Map the omics features to their corresponding reactions in the GEM using Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules.

Step 2: MINN Architecture and Training

- Construct a neural network where the first layer processes the multi-omics data.

- The output of this layer is used to inform the constraints or parameters of a subsequent GEM-embedded mechanistic layer, for example, by setting enzyme capacity constraints.

- Train the model end-to-end, allowing the neural network to learn how omics data inform flux constraints, thereby improving the mechanistic model's predictions.

Step 3: Conflict Mitigation and Interpretation

- Monitor for conflicts between the data-driven omics signals and the mechanistic flux constraints during training.

- Apply strategies to mitigate these conflicts, such as coupling the MINN output with a final parsimonious FBA (pFBA) step to enhance the interpretability and thermodynamic plausibility of the final flux solution [5].

Protocol 3: Identifying Context-Specific Metabolic Objectives with TIObjFind

This protocol uses the TIObjFind framework to infer data-driven objective functions from experimental fluxes, moving beyond assumed objectives like biomass maximization [2].

Step 1: Flux Data Collection and Network Representation

- Perform FBA under a range of environmental conditions relevant to your study (e.g., different stages of fermentation).

- Map the FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), a directed graph representing the flow of metabolites through the network.

Step 2: Optimization and Coefficient Calculation

- Formulate and solve an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred, weighted metabolic goal.

- The framework calculates "Coefficients of Importance" (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to this inferred objective function.

Step 3: Pathway Analysis and Hypothesis Generation

- Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to identify critical pathways connecting key inputs (e.g., glucose uptake) to target outputs (e.g., product secretion).

- Analyze the CoIs across different system states (e.g., different fermentation phases) to reveal how metabolic priorities shift and generate testable hypotheses about cellular regulation [2].

The integration of artificial intelligence with mechanistic metabolic models represents a transformative shift in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Future developments will likely focus on creating more sophisticated hybrid architectures, improving the efficiency of differentiable solvers for large-scale models, and expanding applications to complex systems like synthetic cells [9] or cancer metabolism [8] [4]. The exploration of multi-reaction dependencies and forced balancing opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention, suggesting that targeting specific metabolic complexes could selectively disrupt cancer growth [6]. As these AMN hybrid models continue to evolve, they will profoundly enhance our ability to design high-performance cell factories for biomanufacturing and to uncover novel metabolic vulnerabilities in disease, ultimately bridging the critical gaps left by traditional constraint-based models.

Artificial Metabolic Networks (AMNs) represent a innovative class of hybrid neural-mechanistic models specifically designed to enhance the predictive power of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs). Traditional constraint-based metabolic models, such as those analyzed with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have been used for decades to predict microbial phenotypes in different environments. However, their quantitative predictive power is limited unless labor-intensive measurements of media uptake fluxes are performed [3]. AMNs address this fundamental limitation by serving as an architecture for machine learning that embeds metabolic networks within artificial neural networks. This hybrid approach grasps the power of machine learning while fulfilling mechanistic constraints, thus saving time and resources in typical systems biology or biological engineering projects [3].

The core innovation of AMNs lies in their ability to surrogate constraint-based modeling and make metabolic networks suitable for backpropagation, enabling them to be used as a learning architecture [10]. Unlike previous approaches that used machine learning either as a pre-process or post-process for FBA, AMNs fully embed the metabolic model into the neural network framework, creating a truly integrated hybrid system [3] [11]. This represents a significant paradigm shift in metabolic modeling: instead of relying on a constrained optimization principle performed for each condition independently (as in classical FBA), AMNs use a learning procedure on a set of example flux distributions that attempts to generalize the best model for accurately predicting the metabolic phenotype of an organism across diverse conditions [3].

The Conceptual Framework of AMN Models

Fundamental Architecture and Components

The architecture of an Artificial Metabolic Network consists of two primary components: a trainable neural layer followed by a mechanistic layer. The neural layer computes an initial value for the flux distribution (V₀) from either medium uptake flux bounds (Vᵢₙ) when working with FBA-simulated training sets, or directly from medium compositions (Cₘₑd) for experimental training sets [3]. This initial flux distribution serves to limit the number of iterations required by the subsequent mechanistic layer.

The mechanistic layer implements surrogate methods for traditional FBA solvers that are compatible with gradient backpropagation. Three alternative mechanistic methods have been developed to replace the traditional Simplex solver while producing equivalent results: the Wt-solver, LP-solver, and QP-solver [3]. These solvers can take any initial flux vector that respects flux boundary constraints and iteratively refine it to produce a steady-state metabolic phenotype prediction.

Training of the neural component is based on the error computation between the predicted fluxes (Vₒᵤₜ) and reference fluxes, while simultaneously enforcing respect for mechanistic constraints through a custom loss function [3] [11]. This dual optimization allows AMNs to learn relationships between environmental conditions (either Vᵢₙ or Cₘₑd) and steady-state metabolic phenotypes that generalize across a set of conditions, unlike traditional FBA which treats each condition in isolation.

Comparative Analysis: AMN vs. Traditional Metabolic Modeling

Table 1: Comparison between Traditional FBA and AMN Approaches

| Feature | Traditional FBA | AMN Hybrid Models |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Paradigm | Pure mechanistic modeling | Hybrid neural-mechanistic approach |

| Computational Method | Linear programming with Simplex solver | Neural network with specialized solvers (Wt-, LP-, QP-solver) |

| Data Requirements | Condition-specific constraints | Training sets of flux distributions |

| Gradient Computation | Not possible through Simplex solver | Enabled via surrogate solvers |

| Generalization Capability | Limited to single-condition optimization | Learns relationships across multiple conditions |

| Implementation | Cobrapy and similar libraries [3] | Custom neural network architectures |

| Primary Application | Condition-specific phenotype prediction | Cross-condition phenotype prediction and pattern learning |

Key Methodological Approaches in AMN Development

Core Implementation Frameworks

Three primary solver methodologies have been developed to enable the integration of metabolic networks with neural networks, each providing a different approach to making FBA constraints amenable to gradient-based learning:

Weighted Solver (Wt-solver): This approach uses a fixed number of iterations with carefully designed update rules to converge toward a steady-state flux distribution that respects mass-balance constraints. The weights in the update rules are optimized during training to minimize both prediction error and constraint violation [3].

Linear Programming Solver (LP-solver): The LP-solver formulates the flux balance problem as a differentiable linear programming problem, enabling gradient computation through the optimization process. This requires specialized techniques to maintain differentiability while solving the linear program [3].

Quadratic Programming Solver (QP-solver): This method reformulates the FBA problem as a quadratic program, which offers advantages for certain types of optimization problems and can provide more stable convergence properties during training [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AMN Implementations

| AMN Implementation | Training Efficiency | Prediction Accuracy | Data Requirements | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt-solver AMN | Moderate | High (R²=0.78 on E. coli growth rates) [10] | Lower | Growth rate prediction in diverse media |

| LP-solver AMN | High | High for flux distributions | Moderate | Gene knockout phenotype prediction |

| QP-solver AMN | Lower | Highest for complex constraints | Higher | Systems with additional constraints |

| MINN Framework [5] | Moderate | Superior to pFBA and Random Forest | Higher (requires multi-omics) | Multi-omics integration scenarios |

Workflow and Implementation Protocols

Protocol 3.2.1: Basic AMN Implementation for Growth Rate Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing an AMN to predict microbial growth rates across different media compositions, based on the methodology described in Faure et al. [10].

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Collect training data comprising growth rates and/or flux distributions across different environmental conditions (media compositions or genetic backgrounds).

- For FBA-simulated training sets, use the medium uptake flux bounds (Vᵢₙ) as input features.

- For experimental training sets, use the medium composition (Cₘₑd) as input features, typically represented as concentration vectors.

- Normalize all input features to ensure stable network training.

Network Architecture Configuration

- Design the neural preprocessing layer with appropriate dimensions based on input feature size.

- Select the mechanistic solver type (Wt-, LP-, or QP-solver) based on the problem complexity and available computational resources.

- Define the output layer to match the target predictions (growth rate, key flux values, or full flux distributions).

Model Training and Validation

- Implement a custom loss function that combines prediction error (e.g., mean squared error) with mechanistic constraint violations (e.g., mass-balance deviations).

- Utilize cross-validation with held-out conditions to assess model generalization capability.

- Monitor both training and validation performance to prevent overfitting, using early stopping if necessary.

Model Interpretation and Analysis

- Extract learned parameters from the neural preprocessing layer to identify patterns in condition-specific constraint prediction.

- Compare predictions with experimental measurements or gold-standard simulations to quantify performance improvement over traditional FBA.

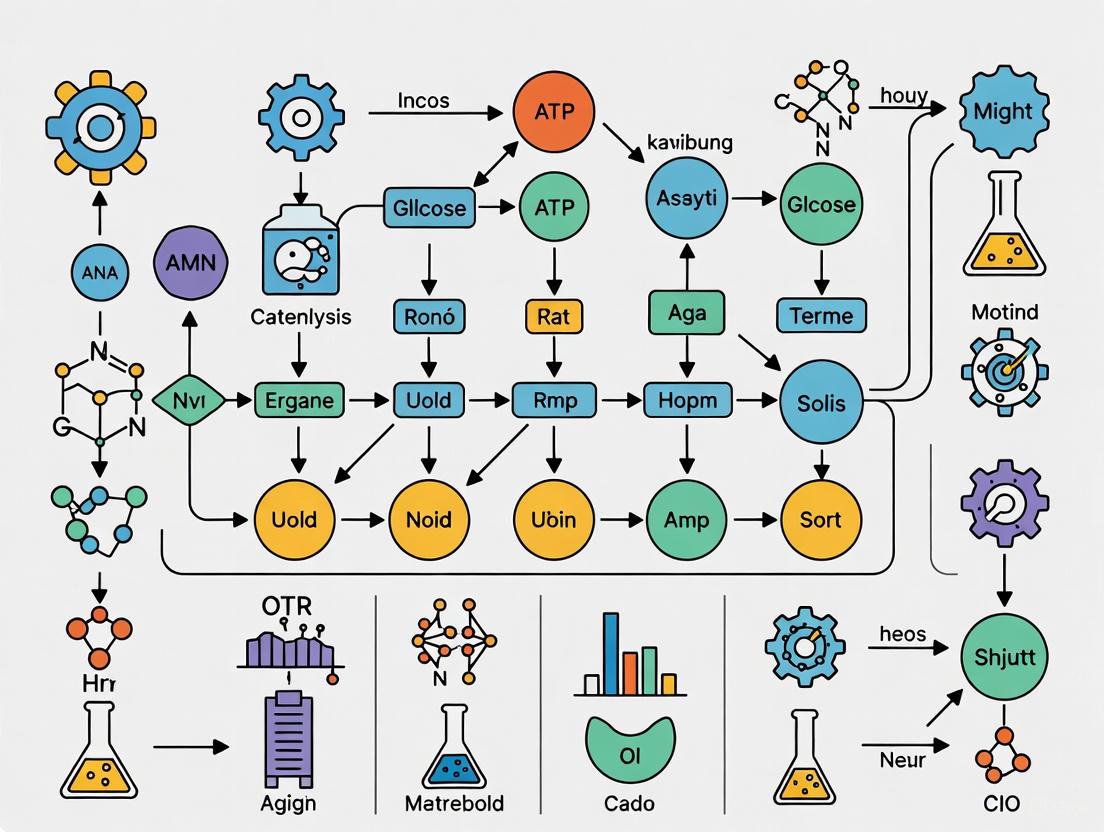

Figure 1: AMN Implementation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for developing and training an Artificial Metabolic Network, highlighting the integration between neural and mechanistic components.

Advanced Applications and Extensions

Multi-Omics Integration with Metabolic-Informed Neural Networks

A significant extension of the AMN framework is the Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN), which specifically addresses the integration of multi-omics data into genome-scale metabolic modeling [5]. MINN utilizes hybrid neural networks to incorporate diverse molecular data types (such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) while maintaining the constraints imposed by metabolic networks.

The MINN framework demonstrates how conflicts can emerge between data-driven objectives and mechanistic constraints, and provides solutions to mitigate these conflicts [5]. Different versions of MINN have been tested to handle the trade-off between biological constraints and predictive accuracy, with results showing that MINN outperforms both parsimonious Flux Balance Analysis (pFBA) and Random Forest models on multi-omics datasets from E. coli single-gene knockout mutants grown in minimal glucose medium [5].

Industrial and Biotechnology Applications

AMN technology has significant implications for biotechnology and industrial applications, particularly in the design of high-performance cell factories [7]. The deep integration of artificial intelligence with metabolic models is crucial for constructing superior microbial chassis strains with higher titers, yields, and production rates—key determinants in the economic viability of bio-based products competing with petroleum-based alternatives [7].

In the context of Industry 4.0 and 5.0, hybrid modeling approaches like AMN facilitate the implementation of "smart manufacturing" in biochemical industries [12]. By combining first-principles understanding with the flexibility of data-driven techniques, AMNs enable better process control and optimization, particularly in sectors where data generation is resource-intensive and fundamental processes are not fully understood [12].

Figure 2: AMN Application Landscape. This diagram showcases the diverse applications of Artificial Metabolic Networks across biotechnology, drug discovery, industrial bioprocessing, and basic research.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AMN Implementation

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | Cobrapy [3] | Reference FBA implementation for generating training data | Essential for creating simulated training sets |

| Model Organisms | Escherichia coli GEMs (iML1515) [3] | Benchmark organism with well-curated models | Extensive validation data available |

| Model Organisms | Pseudomonas putida GEMs [3] | Alternative organism for method validation | Tests generalizability across species |

| Data Types | Multi-omics datasets (transcriptomics, proteomics) [5] | Training data for MINN implementations | Requires appropriate normalization |

| Software Libraries | SciML.ai [3] | Scientific machine learning infrastructure | Provides differential equation solvers |

| Performance Metrics | R² regression coefficient [10] | Quantitative assessment of prediction accuracy | Enables cross-study comparisons |

| Validation Methods | Cross-validation on held-out conditions [3] | Assessment of model generalization | Critical for evaluating practical utility |

Future Directions and Development Opportunities

The development of AMN models represents a significant step toward building high-performance, insightful whole-cell models—an ambitious goal in systems biology [11]. Future research directions likely include extending the AMN framework to incorporate dynamic and multi-strain modeling capabilities, building on approaches used in traditional GEMs to understand metabolic diversity across strains [13].

Another promising direction involves the application of AMN methodology to human metabolic networks and their implications for drug discovery [14]. As noted in early work on human metabolic network reconstruction, such networks "provide a unified platform to integrate all the biological and medical information on genes, proteins, metabolites, disease, drugs and drug targets for a system level study of the relationship between metabolism and disease" [14]. The enhanced predictive capability of AMNs could significantly advance this vision.

Further technical development will also be needed to improve the scalability and interpretability of AMN models. Current research indicates that while AMNs require training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than classical machine learning methods, there remains a trade-off between model complexity and practical utility [3] [5]. Developing more efficient training algorithms and better visualization tools for understanding the learned relationships will be crucial for widespread adoption in industrial and research settings.

Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN) hybrid models represent a groundbreaking architecture that fuses the pattern-recognition power of machine learning (ML) with the structured knowledge of mechanistic biological models [3]. These models are designed to overcome the individual limitations of pure data-driven and pure mechanistic approaches. While mechanistic models, such as Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), provide a structured framework based on biochemical principles, they often lack accuracy in quantitative phenotype predictions unless constrained by labor-intensive experimental measurements [3]. On the other hand, pure ML models can uncover complex patterns but typically require prohibitively large training datasets and lack interpretability [5]. The AMN hybrid framework elegantly bridges this gap by embedding mechanistic models within a trainable neural network architecture, creating models that are both predictive and physiologically constrained [3] [7].

At its core, the AMN architecture consists of two fundamental components: a neural pre-processing layer that learns to convert raw experimental conditions into biologically meaningful constraints, and a mechanistic solver that computes the resulting metabolic phenotype while respecting biochemical laws [3]. This combination allows the model to generalize from a set of example flux distributions, learning a relationship between environmental conditions and metabolic outcomes, rather than solving each condition in isolation as in traditional constraint-based modeling [3]. The following sections detail the core components, their implementation, and practical applications in biological research and drug development.

The Neural Pre-Processing Layer

Function and Architecture

The neural pre-processing layer serves as a critical interface between raw experimental inputs and the mechanistic model. Its primary function is to convert medium composition or gene knockout information into appropriate inputs for the metabolic model, effectively capturing complex biological phenomena that are difficult to model explicitly, such as transporter kinetics and metabolic enzyme regulation [3]. In technical terms, this layer is a trainable neural network that takes either medium uptake flux bounds (Vin) or direct medium compositions (Cmed) as input and produces an initial flux vector (V0) for the mechanistic solver [3].

This layer typically consists of a feed-forward neural network architecture, which is the fundamental type of neural network where information flows in one direction from input to output layers [15] [16]. Like all neural networks, it comprises interconnected artificial neurons organized in layers, including an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer [17]. Each neuron receives inputs, performs mathematical operations using weights and biases, and produces outputs through activation functions that introduce non-linearity, enabling the network to learn complex relationships [15] [17].

Implementation and Training

The implementation of the pre-processing layer involves several critical components and steps:

- Input Processing: The layer can handle various data types, including extracellular concentrations, gene knockout information, or multi-omics data [3] [5]. For categorical data (e.g., strain genotypes), embedding layers or lookup tables are often employed [18].

- Stateful Pre-processing: For certain data types, particularly text or categorical variables, stateful pre-processing layers such as

layer_string_lookup()andlayer_text_vectorization()are used. These layers require anadapt()step on a training dataset to build necessary lookup tables before being integrated into the full model [18]. - Integration with Model: The pre-processing layer can be implemented as part of the main model architecture or as part of a separate data input pipeline, with the choice often depending on performance considerations [18].

- Training Process: During training, the weights of the pre-processing layer are adjusted through backpropagation. In this process, the error between predicted and reference fluxes is calculated and propagated backward through the network to update connection weights, gradually improving the layer's predictive accuracy [16].

Table 1: Key Components of the Neural Pre-Processing Layer

| Component | Description | Function in AMN |

|---|---|---|

| Input Layer | Initial layer receiving external data [15] [17] | Loads medium composition (Cmed) or uptake bounds (Vin) |

| Hidden Layers | Intermediate layers performing computations [15] [17] | Extract features and transform inputs through weighted connections |

| Weights and Biases | Parameters associated with connections between neurons [17] | Adjusted during training to optimize predictions |

| Activation Functions | Mathematical functions introducing non-linearity [15] [17] | Enable learning of complex, non-linear relationships in data |

| Output Layer | Final layer producing the network's outputs [15] [17] | Generates initial flux vector (V0) for mechanistic solver |

Diagram 1: Neural pre-processing layer architecture showing transformation of raw inputs into initial flux vectors.

The Mechanistic Solver

Role in AMN Architecture

The mechanistic solver constitutes the "white-box" component of the AMN hybrid model, ensuring that all predictions adhere to fundamental biochemical principles. It replaces the traditional Simplex solver used in standard Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with gradient-friendly alternatives that can be embedded within neural networks [3]. This component is responsible for computing the steady-state metabolic phenotype (Vout)—comprising all metabolic fluxes in the network—that satisfies the constraints of the metabolic model while optimizing cellular objectives [3].

The solver operates under the same fundamental constraints as traditional constraint-based models: mass-balance constraints according to the stoichiometric matrix, and upper and lower bounds for each flux in the distribution [3]. At metabolic steady state—typically assumed during the mid-exponential growth phase—the solver identifies a flux distribution that maximizes a cellular objective, most commonly biomass production (growth rate) [3]. By integrating this mechanistic component directly into the learning architecture, AMNs gain the ability to produce biochemically feasible predictions even when training data is limited.

Solver Variants and Implementation

Three alternative mechanistic solvers have been developed to replace the traditional Simplex solver in FBA, each producing equivalent results but enabling gradient backpropagation [3]:

- Wt-solver: A weighted approach that leverages biochemical priors to guide flux solutions

- LP-solver: A linear programming-based solver reformulated for differentiability

- QP-solver: A quadratic programming variant that can incorporate additional optimization constraints

These solvers accept the initial flux vector (V0) produced by the neural pre-processing layer and iteratively refine it to arrive at a steady-state solution that respects all metabolic constraints [3]. The integration of these solvers within the neural network architecture represents a significant technical advancement, as it enables end-to-end training of the entire hybrid model while maintaining biochemical fidelity.

Table 2: Comparison of Mechanistic Solvers in AMN Frameworks

| Solver Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wt-Solver | Uses weighted optimization with biochemical priors [3] | Incorporates domain knowledge; improved convergence | Requires careful tuning of weight parameters |

| LP-Solver | Linear programming formulation [3] | Computational efficiency; well-established theory | May require reformulation for differentiability |

| QP-Solver | Quadratic programming approach [3] | Additional constraint flexibility; smoothing properties | Increased computational complexity |

| Traditional FBA | Standard Simplex-based solver [3] | Widely validated; community standards | Not differentiable; cannot be embedded in ML |

Diagram 2: Mechanistic solver component showing constraint types and solver variants producing steady-state fluxes.

Integrated AMN Architecture and workflow

End-to-End System Integration

The complete AMN architecture seamlessly integrates the neural pre-processing layer with the mechanistic solver to form a unified predictive system. During operation, experimental conditions—such as medium composition or genetic modifications—are fed into the neural pre-processing layer, which transforms them into an initial flux vector (V0) [3]. This initial estimate is then passed to the mechanistic solver, which refines it into a biochemically feasible steady-state flux distribution (Vout) that represents the predicted metabolic phenotype [3].

The training process employs a hybrid approach where the model learns from reference flux distributions, which can be obtained either through experimental measurements or in silico simulations using traditional FBA [3]. The training involves minimizing the difference between the predicted fluxes (Vout) and reference fluxes while simultaneously ensuring adherence to mechanistic constraints [3]. This dual-objective optimization is achieved through custom loss functions that surrogate the FBA constraints, enabling the model to both fit the data and respect biochemical laws [3].

Workflow and Training Protocol

A standardized protocol for implementing and training AMN models includes the following key steps:

- Data Preparation: Collect and preprocess training data, which may include experimental measurements of metabolic fluxes, growth rates, or omics data, or alternatively, FBA-simulated flux distributions [3] [5]. For the neural pre-processing layer, this may involve normalization of continuous variables and encoding of categorical variables.

- Network Architecture Definition: Determine the structure of the neural pre-processing layer, including the number of hidden layers, neurons per layer, and activation functions [17]. Common choices include ReLU activation functions for hidden layers and linear or sigmoid functions for output layers, depending on the required output range.

- Mechanistic Layer Configuration: Select and configure the appropriate mechanistic solver (Wt-solver, LP-solver, or QP-solver) based on the specific metabolic model and prediction task [3]. This includes defining the stoichiometric matrix, flux bounds, and cellular objective function.

- Model Training: Implement iterative training using backpropagation, where each epoch consists of a forward pass (from input to output) and a backward pass (error propagation and weight adjustment) [16]. The custom loss function should combine a data-fitting term (e.g., mean squared error between predicted and reference fluxes) and a constraint satisfaction term.

- Model Evaluation: Assess trained model performance on separate validation and test datasets using domain-appropriate metrics such as growth rate prediction accuracy, flux correlation with experimental measurements, or gene essentiality prediction correctness [3].

- Deployment and Inference: Deploy the trained model for predicting metabolic phenotypes under new conditions, leveraging the integrated architecture where the neural pre-processing layer automatically generates appropriate inputs for the mechanistic solver based on experimental specifications [3].

Diagram 3: End-to-end AMN workflow showing training cycle with forward pass and backpropagation.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Growth Rate Prediction in Escherichia coli

Objective: To train an AMN hybrid model for predicting growth rates of E. coli under various medium conditions and gene knockouts.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological System: E. coli K-12 MG1655 strain and single-gene knockout mutants [3] [5]

- Growth Media: Minimal media with varying carbon sources (e.g., glucose, glycerol, acetate) at different concentrations [3]

- Reference Data: Experimentally measured growth rates or FBA-simulated fluxes using a consensus E. coli GEM (e.g., iML1515) [3] [5]

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Compile a dataset of growth rates for E. coli under different medium conditions and genetic backgrounds. Include at least 20 distinct conditions for training with 5-10 additional conditions for validation [3].

- Model Initialization:

- Implement a neural pre-processing layer with 2 hidden layers of 64 neurons each, using ReLU activation functions [3].

- Configure the mechanistic layer using the E. coli iML1515 metabolic model [3] with biomass maximization as the objective function.

- Initialize using the Wt-solver with uniform random weights between -0.1 and 0.1.

- Training Configuration:

- Set training parameters: learning rate = 0.001, batch size = 8, maximum epochs = 1000 [3].

- Use mean squared error as the primary loss function with additional regularization terms for constraint satisfaction.

- Implement early stopping with a patience of 50 epochs based on validation loss.

- Model Training:

- Execute the training loop, alternating between forward passes and backpropagation.

- Monitor both training and validation loss to avoid overfitting.

- Save model checkpoints at intervals of 50 epochs.

- Validation:

- Evaluate the trained model on the validation set of conditions not seen during training.

- Calculate Pearson correlation coefficient between predicted and measured growth rates.

- Compare performance against traditional FBA predictions.

Expected Outcomes: The AMN model should achieve growth rate predictions with significantly higher correlation to experimental measurements compared to traditional FBA, with typical Pearson R values increasing from ~0.7 with FBA to ~0.9 with AMN [3].

Protocol for Multi-Omics Integration with MINN Framework

Objective: To integrate transcriptomic and metabolomic data with GEMs using the Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN) framework for improved flux prediction [5].

Materials:

- Omics Data: RNA-seq transcriptomics and LC-MS metabolomics data from E. coli cultures under different growth conditions [5]

- Metabolic Model: E. coli core metabolic model or genome-scale model [5]

- Software: MINN implementation (Python-based with TensorFlow/PyTorch) [5]

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize transcriptomic data using TPM normalization and log2 transformation.

- Normalize metabolomic data using autoscaling (mean-centered and unit variance).

- Integrate both datasets to create a multi-omics input matrix.

- MINN Architecture Setup:

- Design the input layer to accommodate the multi-omics feature dimension.

- Implement specialized layers for handling the trade-off between biological constraints and predictive accuracy [5].

- Configure the output layer to predict metabolic fluxes for key reactions.

- Hybrid Training:

- Train the model using a combined loss function that includes both data-fitting terms (mean squared error for flux predictions) and mechanistic constraint terms (mass balance violations).

- Employ gradient descent optimization with adaptive learning rates.

- Model Interpretation:

- Analyze feature importance in the neural network components to identify key omics features driving flux predictions.

- Compare flux predictions with those from parsimonious FBA (pFBA) and random forest models as benchmarks [5].

Expected Results: MINN should outperform both pFBA and pure machine learning methods (e.g., random forest) in predicting metabolic fluxes, particularly when training data is limited [5]. The framework should also provide insights into conflicts between data-driven predictions and mechanistic constraints, suggesting potential regulatory mechanisms [5].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for AMN Implementation

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in AMN Research | Example Sources/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational Model | Provides mechanistic framework for metabolic network | E. coli iML1515 [3], organism-specific GEMs [7] |

| Curiox C-FREE Pluto System | Automation Equipment | Enables scalable automation for sample preparation in validation workflows [19] | Charles River Laboratories [19] |

| Multi-Omics Datasets | Experimental Data | Provides training data for neural components (transcriptomics, metabolomics) [5] | RNA-seq, LC-MS, GC-MS platforms |

| Flux Balance Analysis Software | Computational Tool | Generates reference flux distributions for training [3] | Cobrapy [3], COBRA Toolbox |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Software Library | Implements neural network components and training algorithms | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras [18] |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms | Experimental System | Provides human-relevant data for translational validation [19] | CN Bio, Emulate systems [19] |

In the quest to understand and predict cellular behavior, systems biology has long been divided between two powerful yet imperfect modeling paradigms: mechanistic models and machine learning (ML) approaches. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), which provide structured representations of metabolic networks based on gene-protein-reaction associations and stoichiometric constraints, represent the pinnacle of mechanistic modeling in biology [20] [21]. These models enable the prediction of organism phenotypes through methods such as flux balance analysis (FBA), which optimizes a biological objective like biomass production under steady-state mass balance constraints [3] [22]. For decades, GEMs have served as invaluable tools for metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and fundamental biological research, offering interpretable predictions grounded in biochemical first principles [20] [21]. However, GEMs face significant limitations in quantitative prediction accuracy, particularly because they struggle to incorporate complex cellular regulation and often lack condition-specific parameters such as accurate uptake flux bounds [3].

Simultaneously, the rise of artificial intelligence has brought deep learning and neural networks to the forefront of scientific modeling, offering unparalleled pattern recognition capabilities and the ability to learn complex, non-linear relationships directly from data [3] [5]. Pure ML models can uncover intricate patterns within multi-omics datasets that traditional mechanistic approaches might miss, but they typically require massive training datasets and often function as "black boxes" with limited biological interpretability [5]. Most critically, they lack the structured biochemical knowledge embedded in GEMs, making them prone to unbiological predictions [3].

The emerging hybrid approach, termed Artificial Metabolic Networks (AMNs) or similar frameworks, represents a transformative integration of these paradigms that leverages the strengths of both while mitigating their individual weaknesses [3] [5] [22]. By embedding GEMs within neural network architectures, researchers have created models that respect biochemical constraints while learning complex patterns from experimental data. This fusion addresses a fundamental challenge in biological modeling: how to make predictions that are both data-accurate and biologically plausible. As we explore in this protocol, the rationale for combining GEMs with neural networks extends far beyond incremental improvement, instead offering a new paradigm for predictive biology with applications spanning biotechnology, medicine, and basic research.

The Core Rationale: Complementary Strengths and Weaknesses

Fundamental Limitations of Standalone Approaches

Constraint-Based Modeling with GEMs operates on well-established biochemical principles but faces several critical limitations. Traditional FBA assumes organisms optimize a single biological objective (typically growth rate) across all conditions, an assumption that frequently breaks down for mutant strains or in complex environments [22]. The method also requires precise uptake flux bounds to simulate different environmental conditions, but converting extracellular medium compositions to these internal flux constraints remains challenging without labor-intensive experimental measurements [3]. Furthermore, GEMs typically lack representations of metabolic regulation, enzyme kinetics, and resource allocation, leading to inaccurate quantitative predictions despite correct qualitative trends [3]. While GEMs can predict gene essentiality with approximately 90% accuracy in well-characterized model organisms like E. coli, this performance drops significantly for eukaryotes and less-studied organisms [22].

Pure Neural Networks and Machine Learning face different challenges when applied to metabolic prediction tasks. These data-driven approaches require large training datasets—a particular problem in biology where experimental data are often scarce and expensive to generate [3] [5]. A pure ML model might achieve high accuracy on its training distribution but can produce thermodynamically infeasible or biologically impossible predictions because it lacks inherent knowledge of biochemical constraints [3]. Additionally, the "black box" nature of deep learning models limits biological interpretability, making it difficult to extract mechanistic insights from their predictions [5].

The Hybrid Advantage: Synergistic Benefits

The integration of GEMs and neural networks creates a framework where the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts, as illustrated in the table below which summarizes the complementary strengths of this hybrid approach.

Table 1: Complementary Strengths of GEMs and Neural Networks in Hybrid Models

| Aspect | Standalone GEMs | Pure Neural Networks | Hybrid GEM-NN Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Grounding | Strong biochemical constraints | Limited biochemical knowledge | Embedded mechanistic constraints |

| Data Requirements | Can operate with minimal data | Require large datasets | Reduced data needs via mechanistic priors |

| Interpretability | High mechanistic interpretability | "Black box" predictions | Balance between prediction and insight |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Limited for fluxes and growth rates | High for trained conditions | Improved quantitative phenotype prediction |

| Handling Regulation | Poor representation of regulation | Can learn regulatory patterns | Captures unmodeled regulation effects |

| Generalization | Good extrapolation to new conditions | Limited to training distribution | Improved generalization capabilities |

The hybrid approach demonstrates particular advantage in several key areas. By embedding GEM constraints within neural architectures, these models naturally respect stoichiometric mass balance and thermodynamic constraints while learning complex mappings from environmental conditions to metabolic phenotypes [3]. This integration enables researchers to parameterize GEMs through direct training, significantly enhancing their predictive power without sacrificing biochemical realism [3]. The neural components can effectively capture missing cellular regulation, such as transporter kinetics and gene expression effects, that are not represented in traditional GEMs [3]. Perhaps most importantly, these hybrid models can achieve high accuracy with training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than those required by classical machine learning methods, overcoming a fundamental limitation of pure data-driven approaches in data-scarce biological domains [3].

Quantitative Evidence: Performance Improvements in Practice

Documented Performance Gains Across Applications

Multiple studies have demonstrated significant performance improvements when using hybrid GEM-NN approaches compared to traditional methods. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from recent implementations.

Table 2: Documented Performance of Hybrid GEM-NN Models

| Model/Approach | Task | Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMN (Neural-Mechanistic) | Growth rate prediction (E. coli, P. putida) | Systematically outperformed constraint-based models | [3] |

| MINN (Metabolic-Informed NN) | Metabolic flux prediction (E. coli knockouts) | Outperformed pFBA and Random Forest on small multi-omics dataset | [5] |

| FlowGAT (GNN + GEM) | Gene essentiality prediction (E. coli) | Achieved accuracy close to FBA gold standard across multiple growth conditions | [22] |

| AMN (General Framework) | Training efficiency | Required training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than classical ML | [3] |

These performance gains manifest in several critical applications. In growth rate prediction, hybrid models have demonstrated systematic outperformance over traditional constraint-based approaches for organisms including Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas putida grown in different media [3]. For metabolic flux prediction, the Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN) framework showed superior performance compared to both parsimonious FBA (pFBA) and Random Forest models when predicting fluxes in E. coli across different growth rates and gene knockout conditions [5]. In gene essentiality prediction, the FlowGAT model, which integrates graph neural networks with GEMs, achieved prediction accuracy approaching the FBA gold standard for E. coli across multiple growth conditions, demonstrating the ability to maintain high performance without requiring the optimality assumption for deletion strains [22].

Case Study: FlowGAT for Gene Essentiality Prediction

The FlowGAT implementation provides particularly insightful quantitative evidence of hybrid model advantages. This approach addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional FBA: the assumption that both wild-type and gene deletion strains optimize the same metabolic objective [22]. In reality, knockout mutants may steer their metabolism toward different survival objectives, violating this core FBA assumption. FlowGAT circumvents this problem by using a graph neural network trained on wild-type FBA solutions to predict gene essentiality directly, without assuming optimality in deletion strains [22].

The model constructs a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) from FBA solutions, where nodes represent metabolic reactions and edges represent metabolite mass flow between reactions [22]. This graph structure incorporates both the directionality of metabolite flow and the relative weight of different metabolic paths. A Graph Attention Network (GAT) then processes this representation to predict gene essentiality, effectively learning the relationship between wild-type metabolic network structure and the fitness consequences of gene deletions [22]. Remarkably, FlowGAT achieved prediction accuracy comparable to traditional FBA while generalizing well across various carbon sources without additional training data, demonstrating the method's ability to extract generalizable principles from metabolic network structure [22].

Implementation Protocols: Architectural Frameworks and Methodologies

Core Architectural Framework for AMN Development

The fundamental architecture of artificial metabolic networks involves connecting a trainable neural processing component with a mechanistic GEM-based solver. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and information flow in a typical AMN implementation.

AMN Architecture: Neural-Mechanistic Hybrid Workflow

The AMN framework consists of two primary components: a neural processing layer that learns to predict initial flux distributions from either medium compositions (Cmed) for experimental training sets or uptake flux bounds (Vin) for FBA-simulated training sets, and a mechanistic layer that applies constraint-based solving to satisfy stoichiometric and flux bound constraints [3]. The neural component serves as a trainable feature extractor that captures complex relationships between environmental conditions and metabolic states, while the mechanistic layer ensures biochemical feasibility of the final predictions [3]. During training, the loss function computes both the error between predicted and reference fluxes and any violation of mechanistic constraints, with gradients backpropagated through the entire architecture to optimize the neural parameters [3].

Protocol: Implementing a Basic AMN for Growth Prediction

Objective: Implement a neural-mechanistic hybrid model to predict microbial growth rates from medium composition.

Materials and Reagents: Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| GEM Resources | COBRApy package, Agren et al. GEMs | Constraint-based modeling framework and organism-specific metabolic models |

| ML Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, SciML.ai | Neural network implementation and training |

| Organism Models | E. coli iML1515, S. cerevisiae Yeast7 | Well-curated metabolic models for validation |

| Training Data | Experimental growth data, FBA-simulated fluxes | Reference data for model training and validation |

Methodology:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Collect experimental growth data or generate FBA-simulated training fluxes for various medium conditions

- Normalize input features (metabolite concentrations) and output targets (growth rates, fluxes)

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets (typical ratio: 70/15/15)

Neural Network Component Implementation

- Design a feedforward neural network with 2-3 hidden layers

- Input dimension: number of possible medium components

- Output dimension: number of reactions in the GEM or specific target fluxes

- Use ReLU activation functions in hidden layers

Mechanistic Solver Integration

- Implement one of three alternative solvers to replace traditional Simplex for gradient flow:

- Wt-solver: Weight-based iterative balancing

- LP-solver: Differentiable linear programming approach

- QP-solver: Quadratic programming with penalty methods

- Enforce stoichiometric constraints (Sv = 0) and flux bounds (lb ≤ v ≤ ub)

- Implement one of three alternative solvers to replace traditional Simplex for gradient flow:

Model Training and Optimization

- Define composite loss function: L = α‖Vout - Vref‖ + β‖S·v‖ + γ·constraintviolationpenalty

- Use Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001-0.01

- Implement early stopping based on validation loss

- Train for 100-500 epochs depending on dataset size

Validation and Testing

- Compare predictions against holdout test set

- Benchmark against traditional FBA predictions

- Perform statistical analysis of prediction errors

Technical Notes: The choice of solver involves trade-offs between computational efficiency and biological accuracy. Wt-solver offers fastest computation but may sacrifice some accuracy, while QP-solver provides highest fidelity but increased computational cost [3]. For most applications, starting with the LP-solver approach provides a reasonable balance.

Application Scenarios and Use Cases

Biotechnology and Metabolic Engineering

In industrial biotechnology, hybrid GEM-NN models significantly enhance strain optimization and pathway design. Traditional FBA-based approaches like OptKnock have been used for decades to identify gene knockout strategies that maximize product yield while maintaining growth, but these methods often fail to accurately predict quantitative production levels due to missing regulatory information [20] [21]. Hybrid models overcome this limitation by learning the complex relationships between genetic modifications and metabolic phenotypes from experimental data, enabling more accurate prediction of production strains for bio-based chemicals and materials [3] [21]. The MINN framework, for instance, has demonstrated particular utility for predicting metabolic fluxes in engineered strains, providing critical guidance for metabolic engineering campaigns [5].

Biomedical Research and Drug Development

In biomedical applications, hybrid models enable drug target identification in pathogens and disease modeling in human systems. For pathogenic organisms like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, GEMs have been used to identify essential genes as potential drug targets, but prediction accuracy has been limited by the optimality assumption and missing regulatory constraints [21] [22]. Hybrid approaches like FlowGAT improve essentiality prediction by learning from wild-type metabolic network structure, potentially identifying more reliable therapeutic targets [22]. In cancer research, context-specific GEMs of human cells have been integrated with neural networks to predict metabolic vulnerabilities in tumor cells, with hybrid models providing more accurate predictions of gene essentiality in cancer types than traditional FBA [21].

Systems Biology and Basic Research

For basic research, hybrid models serve as powerful tools for multi-omics data integration and phenotype prediction. GEMs provide an ideal scaffold for integrating transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data, but traditional constraint-based approaches struggle to leverage the full complexity of these datasets [20] [21]. Neural network components can effectively extract patterns from high-dimensional omics data and map them to metabolic states, enabling more accurate prediction of metabolic fluxes and cellular phenotypes from molecular profiling data [5]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying less-characterized organisms where comprehensive metabolic regulation remains unknown.

Future Directions and Implementation Considerations

Emerging Trends and Development Opportunities

The field of hybrid GEM-NN modeling continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising directions emerging. Graph neural networks represent a particularly exciting avenue, as they can naturally represent the inherent graph structure of metabolic networks [22]. Approaches like FlowGAT, which use mass flow graphs derived from FBA solutions, demonstrate how GNNs can capture local dependencies between metabolic reactions and their neighbor pathways to improve prediction accuracy [22]. Another promising direction involves transfer learning, where models pre-trained on well-characterized organisms like E. coli are fine-tuned for less-studied species, potentially overcoming the data scarcity problem that plagues biological ML applications [3].

Integration with multi-scale models represents another frontier, where hybrid metabolic models are connected with neural representations of signaling pathways, gene regulation, and other cellular processes [3]. This could address a fundamental limitation of current GEMs: their inability to represent the complex regulatory hierarchies that control metabolic behavior. Finally, explainable AI techniques are being developed to enhance interpretability of hybrid models, helping researchers extract mechanistic insights from the neural components rather than treating them as black boxes [5].

Practical Implementation Guidelines

For research teams considering implementing hybrid GEM-NN approaches, several practical considerations deserve attention. Teams should assess their data infrastructure capabilities, including tools for storing, analyzing, and integrating complex experimental and in silico data [19]. Validation frameworks must be established to benchmark hybrid model predictions against both experimental data and traditional FBA results [3] [5]. Computational resources must be sufficient for model training, though requirements are typically less demanding than for pure deep learning applications due to the constraint-based regularization [3].

Perhaps most importantly, research teams should embrace an iterative development process that progressively integrates more sophisticated neural components into existing GEM workflows. Starting with simple feedforward networks for specific prediction tasks (e.g., growth rate from medium composition) provides valuable experience before advancing to more complex architectures like graph neural networks or attention mechanisms [3] [22]. This incremental approach maximizes learning while minimizing implementation risk.

The integration of genome-scale metabolic models with neural networks represents a paradigm shift in biological modeling, moving beyond the traditional dichotomy between mechanistic and machine learning approaches. The underlying rationale for this fusion is compelling: by embedding biochemical constraints within flexible learning architectures, hybrid models achieve the quantitative accuracy of data-driven methods while maintaining the biological interpretability and constraint satisfaction of mechanistic models. As the field advances, these hybrid approaches are poised to become standard tools in biotechnology, biomedical research, and systems biology, enabling more accurate prediction of cellular behavior and more reliable design of metabolic interventions.

Key Biological and Computational Problems AMNs Are Designed to Solve

Artificial Metabolic Networks (AMNs) represent a pioneering hybrid computational framework that integrates mechanistic models with machine learning to address long-standing challenges in systems biology and metabolic engineering. Traditional constraint-based metabolic models (GEMs), such as those analyzed with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have been instrumental for decades in predicting phenotypic behavior from genomic information [3]. However, their quantitative predictive power is inherently limited unless supplemented with extensive, labor-intensive experimental data, particularly concerning medium uptake fluxes and gene knock-out effects [3]. AMNs are specifically designed to overcome these limitations by embedding the mechanistic rules of metabolic networks within a trainable artificial neural network architecture. This fusion creates models that are both mechanistically rigorous and data-adaptive, enabling more accurate predictions of organism behavior in various environmental and genetic contexts. Their development is particularly relevant for applications in drug development and bioengineering, where accurate in silico predictions can drastically reduce experimental timelines and costs [23].

Core Biological and Computational Problems

AMNs are engineered to solve critical problems at the intersection of biology and computation, which have traditionally impeded the accurate prediction of cellular phenotypes.

Biological Problems

- Quantitative Phenotype Prediction in Diverse Environments: A fundamental challenge in systems biology is predicting quantitative outcomes, such as growth rates or metabolite production, based solely on the composition of the growth medium [3]. Classical FBA requires precise, condition-specific uptake flux bounds as inputs, which are difficult to determine a priori without experimental measurement. AMNs learn the complex, non-linear relationship between extracellular nutrient concentrations and intracellular uptake fluxes, thereby bypassing this requirement and improving quantitative predictions [3].

- Predicting the Impact of Genetic Perturbations: Understanding the phenotypic consequences of genetic modifications, such as gene knock-outs (KOs), is crucial for metabolic engineering and understanding disease mechanisms. Traditional methods struggle to accurately predict the effects of KOs without ad-hoc adjustments. The neural component of an AMN can learn and generalize the regulatory and compensatory mechanisms that cells employ in response to genetic perturbations, providing more reliable predictions of knockout mutant phenotypes [3].

- Integration of Multi-Omics Data for Personalized Medicine: In human metabolism research, a key problem is leveraging multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) to build patient-specific models for precision medicine [23]. AMNs provide a flexible framework in which these heterogeneous data can be integrated to refine model parameters, enabling more accurate simulations of individual metabolic states for drug development and disease mechanism elucidation [23].

Computational Problems

- The Dimensionality Curse in Machine Learning for Biology: Applying pure machine learning to model whole-cell behaviors is often infeasible due to the curse of dimensionality; the amount of data required to train such models grows exponentially with the complexity of the system [3]. AMNs tackle this by using the mechanistic model as a structural prior, drastically reducing the parameter space and the size of the required training dataset.

- Bridging the Gap Between Mechanistic and Machine Learning Paradigms: Mechanistic models (MM) offer interpretability and understanding but can be inaccurate, while machine learning (ML) models can be highly accurate but are often black boxes. AMNs bridge this gap by embedding MMs directly within ML architectures, creating hybrid models that are both predictive and mechanistically interpretable [3].

- Handling Computational Complexity in Large-Scale Metabolic Networks: As metabolic models expand to genome-scale and beyond to microbial communities, the associated computational problems (e.g., solving large systems of linear equations) can become intractable for classical computers [24]. While AMNs themselves are a classical computing solution, research into quantum algorithms for FBA highlights the computational burden of these problems. The flexible architecture of AMNs is designed to interface with and benefit from such future computational advances [24].

AMN Architecture and Workflow

The core innovation of AMNs lies in their unique architecture, which replaces the traditional, non-differentiable linear programming solver of FBA with a trainable network.

Table 1: Comparison of Classical FBA and the AMN Approach

| Feature | Classical FBA | AMN Hybrid Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input | Pre-defined uptake flux bounds (Vin) | Medium composition (Cmed) or uptake bounds (Vin) |

| Core Solver | Linear Programming (e.g., Simplex) | Differentiable solvers (Wt-, LP-, QP-solver) |

| Learning Mechanism | None (Single condition optimization) | Neural network trained across multiple conditions |

| Key Output | Steady-state flux distribution (Vout) | Predicted flux distribution (Vout) |

| Data Requirement | Labor-intensive flux measurements | Smaller, diverse training sets of flux data |

| Predictive Power | Limited quantitative accuracy | Improved quantitative phenotype predictions |

In classical FBA, each condition (e.g., a specific growth medium) is solved independently by a linear program that maximizes an objective (e.g., biomass) subject to stoichiometric constraints [3]. This process cannot be integrated with gradient-based learning. The AMN framework, illustrated in the workflow below, fundamentally changes this paradigm by introducing a neural pre-processing layer and a differentiable mechanistic layer.

Component Breakdown

- Neural Network Layer: This is the trainable component of the AMN. Its primary function is to take a high-level input, such as the medium composition (Cmed) or nominal uptake bounds (Vin), and predict an initial flux vector (V0). This layer effectively learns to capture complex phenomena like transporter kinetics and metabolic regulation that determine how extracellular conditions translate into metabolic flux constraints [3].

- Differentiable Mechanistic Solver: This component replaces the traditional Simplex solver. It takes the initial flux vector (V0) from the neural network and iteratively refines it to find a flux distribution (Vout) that satisfies the core constraints of the metabolic model: mass balance (stoichiometry) and flux bounds. The use of Wt-, LP-, or QP-solvers ensures that this process is differentiable, allowing error gradients to be backpropagated through the entire network for training [3].

- Training and Loss Function: The AMN is trained on a set of known condition-flux pairs (the training set). The loss function quantifies the discrepancy between the AMN's predicted fluxes (Vout) and the reference fluxes. By minimizing this loss, the neural network learns to generate initial flux vectors that lead the mechanistic solver to accurate, constraint-satisfying solutions [3].

Performance and Quantitative Outcomes

AMNs have demonstrated significant performance improvements over traditional modeling approaches, requiring substantially less data than pure machine learning methods.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of AMN Hybrid Models

| Organism | Prediction Task | Model Type | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Growth rate in different media [3] | AMN Hybrid | Predictive Accuracy | Systematically outperformed classical FBA |

| Pseudomonas putida | Growth rate in different media [3] | AMN Hybrid | Predictive Accuracy | Systematically outperformed classical FBA |

| Escherichia coli | Phenotype of gene knock-out mutants [3] | AMN Hybrid | Predictive Accuracy | Superior performance vs. constraint-based models |

| General Benchmark | Data Efficiency [3] | AMN Hybrid | Required Training Set Size | Orders of magnitude smaller than classical ML |

The ability of AMNs to outperform classical FBA is consistent across different microbial species and prediction tasks, demonstrating the robustness of the approach. A critical advantage is their data efficiency; they achieve high accuracy with training set sizes that are orders of magnitude smaller than those required by classical machine learning methods, effectively overcoming the dimensionality curse for biological applications [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for applying an AMN to a standard metabolic prediction task, such as forecasting microbial growth rates.

Protocol 1: Building an AMN for Growth Rate Prediction

Objective: To construct and train an AMN for predicting organism growth rates from medium composition data.

Materials:

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM): A stoichiometrically reconstructed model of the target organism (e.g., E. coli iML1515) [3].

- Training Dataset: A collection of experimentally measured or FBA-simulated growth rates and flux distributions across multiple, diverse growth media [3].

- Computational Environment: Python with deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) and scientific computing stacks (e.g., SciPy, NumPy). The SciML.ai ecosystem is a valuable resource for hybrid modeling [3].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Format the input data (medium compositions, Cmed) and corresponding target data (growth rates or full flux distributions, Vout).

- Split the data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70/15/15 split).

- Model Initialization:

- Define the Neural Network: Construct a feedforward neural network. The input layer size matches the number of environmental variables (e.g., nutrients in Cmed). The output layer size equals the number of reactions in the GEM, generating the initial flux vector V0.

- Integrate the Mechanistic Solver: Implement one of the differentiable solvers (Wt-, LP-, or QP-solver) that enforces the GEM's stoichiometric constraints and flux bounds. This solver will take V0 as input and output the final predicted flux distribution Vout.

- Model Training:

- Define a loss function, typically the Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the predicted Vout and the target flux distribution from the training set.

- Use a gradient-based optimizer (e.g., Adam) to minimize the loss. In each iteration, gradients are calculated via backpropagation through the differentiable solver and used to update the weights of the neural network.

- Monitor the loss on the validation set to avoid overfitting and determine convergence.

- Model Validation:

- Evaluate the trained AMN on the held-out test set.

- Compare the AMN's predictions of growth rates (a component of Vout) against those made by classical FBA and the ground-truth data. Key metrics include R² correlation and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

Protocol 2: Applying AMNs for Gene Knock-Out Phenotype Prediction

Objective: To adapt and utilize a pre-trained AMN for predicting metabolic phenotypes following gene knock-outs.

Materials:

- A pre-trained AMN from Protocol 1.

- A list of gene knock-outs to simulate.

- The GEM with defined gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules.

Procedure:

- Model Adaptation:

- The AMN's architecture is inherently suited for this task. The neural layer can learn to map the "condition" of a gene knock-out (encoded as an input feature) to altered flux constraints.

- Simulation and Analysis:

- For a given gene knock-out, modify the input vector to the neural network to include this genetic context alongside the medium composition.

- Run the AMN forward pass to obtain the predicted flux distribution (Vout) and growth rate for the mutant.

- Compare the predicted growth rate of the knock-out to the wild-type prediction to classify genes as essential or non-essential.

- Validation:

- Validate predictions against experimental data or established gold-standard simulations for known essential genes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AMN Development

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Database / Software | Provides the mechanistic backbone (stoichiometry, reaction bounds) for the AMN. | E. coli iML1515, P. putida models [3] |

| Cobrapy | Software Library | A classic tool for constraint-based modeling; useful for generating training data and benchmarking AMN performance. | [3] |

| SciML.ai Ecosystem | Software Framework | Provides open-source tools and differential equation solvers tailored for scientific machine learning and hybrid modeling. | [3] |