Beyond Stoichiometry: How Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Models Are Revolutionizing Phenotype Prediction in Biomedicine

This article explores the transformative impact of enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) compared to traditional genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs).

Beyond Stoichiometry: How Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Models Are Revolutionizing Phenotype Prediction in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) compared to traditional genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). While traditional GEMs have been pivotal in predicting metabolic phenotypes using stoichiometric constraints, they often overlook enzymatic and thermodynamic limitations, leading to predictions of biologically infeasible pathways. We detail the methodology behind enhancing GEMs with enzyme constraints using tools like the GECKO toolbox and demonstrate how this integration yields more accurate predictions of cellular behavior, from microbial fermentation to cancer drug response. Through comparative analysis and case studies in metabolic engineering and drug development, we highlight the superior predictive accuracy of ecModels, their current challenges, and their future potential in advancing biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

From Stoichiometric Maps to Physiological Reality: The Core Principles of GEMs and ecModels

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) are in silico representations of an organism's metabolic capacity, constructed from its annotated genome sequence. These models enumerate metabolic reactions, metabolites, and gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations, creating a comprehensive network of metabolic pathways [1]. Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) has emerged as the state-of-the-art computational approach employing GEMs to simulate metabolic behavior in both single organisms and microbial communities [2]. The fundamental principle behind constraint-based modeling is the use of mass-balance, capacity, and steady-state constraints to define the set of possible metabolic behaviors without requiring detailed kinetic parameters. This framework allows researchers to investigate the complexities of metabolism and predict cellular responses to genetic and environmental perturbations [1].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) represents one of the most widely used methods within the COBRA framework. FBA optimizes a predefined biological objective function—typically biomass production—under the assumption of steady-state exponential growth. This approach computes metabolic flux distributions that maximize or minimize the objective while satisfying the imposed constraints [2]. For non-continuous systems such as batch reactors, Dynamic FBA (dFBA) extends this methodology by incorporating differential equations that describe temporal changes in extracellular metabolite concentrations and biomass [2]. More recently, spatiotemporal FBA frameworks have been developed to model microbial systems where the extracellular environment varies in both space and time, using partial differential equations to account for metabolite diffusion and convection [2].

The application of GEMs spans diverse fields including biotechnology, biomedicine, and environmental remediation. In microbial consortia, GEMs help elucidate the mechanisms behind microbial interactions that structure communities and determine their functions [2]. For photoautotrophic organisms like microalgae, GEMs face additional challenges in simulating light-dependent metabolism and diel cycling within a framework that traditionally assumes steady-state behavior [1]. Despite these challenges, GEMs have proven highly effective for simulating metabolic fluxes, identifying genetic engineering targets, and optimizing growth conditions across a wide range of organisms [1].

Quantitative Comparison of Traditional GEM Tools and Approaches

Performance Metrics Across Model Types

Traditional GEM reconstruction approaches vary significantly in their methodology and performance. Table 1 summarizes the performance of automatically reconstructed GEMs against gold-standard models for Escherichia coli and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum in predicting auxotrophy and gene essentiality.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Automatically Reconstructed GEMs

| Model/Tool | Approach | Auxotrophy Prediction Accuracy (%) | Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy (%) | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Top-down | 84.2 | 87.5 | E. coli |

| gapseq | Bottom-up | 89.3 | 90.1 | E. coli |

| modelSEED | Bottom-up | 82.7 | 85.8 | E. coli |

| AGORA | Semi-automatic | 91.5 | 92.3 | E. coli |

| Gold-Standard (Manual) | Manual curation | 95.8 | 96.5 | E. coli |

| GEMsembler Consensus | Combined | 97.2 | 98.1 | E. coli |

Performance data compiled from systematic evaluations [2] [3].

Table 2 provides a systematic qualitative assessment of COBRA-based tools based on FAIR principles (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability), which are essential for software quality and research reproducibility.

Table 2: Qualitative Assessment of COBRA Tools Based on FAIR Principles

| Tool Name | Findability | Accessibility | Interoperability | Reusability | Modeling Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICOM | High | High | Medium | High | Steady-state |

| SMET | Medium | Medium | High | Medium | Dynamic |

| DFBAlab | High | High | Medium | High | Dynamic |

| BacArena | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium | Spatiotemporal |

| COMETS | High | High | High | High | Spatiotemporal |

Qualitative assessment based on systematic evaluation of 24 published tools [2].

Experimental Validation Case Studies

The performance of traditional GEM tools has been quantitatively evaluated against experimental data in several systematic studies. In one comprehensive evaluation, 14 constraint-based modeling tools were tested using datasets from two-member microbial communities as test cases [2]. The assessment included:

- Static tool evaluation: Syngas fermentation by C. autoethanogenum and C. kluyveri

- Dynamic tool evaluation: Glucose/xylose mixture fermentation with engineered E. coli and S. cerevisiae

- Spatiotemporal tool evaluation: A Petri dish of E. coli and S. enterica with diffusion parameters

The results showed varying performance levels across the different categories of tools. Generally, more up-to-date, accessible, and well-documented tools demonstrated superior performance in predictive accuracy, computational time, and physiological relevance. However, in some specific cases, older, less elaborate tools showed advantages in accuracy or flexibility for particular applications [2].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Standard Flux Balance Analysis Protocol

The core methodology for traditional GEMs involves Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which follows these key steps:

- Network Reconstruction: Compile all metabolic reactions, metabolites, and GPR rules based on genome annotation

- Stoichiometric Matrix Formation: Construct matrix S where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions

- Constraint Definition: Apply mass balance (S·v = 0), capacity (vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax), and steady-state constraints

- Objective Specification: Define biological objective function (typically biomass maximization)

- Linear Programming Solution: Solve optimization problem using algorithms like simplex or interior-point methods

The mathematical formulation maximizes the objective function Z = c^T·v subject to S·v = 0 and vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax, where v represents flux vectors and c is the vector of objective coefficients [2].

Consensus Model Assembly with GEMsembler

The GEMsembler framework introduces a methodology for combining GEMs from different reconstruction tools, addressing the challenge that no single tool consistently outperforms others [3]. The workflow involves:

- Feature Conversion: Metabolite and reaction IDs from input models are converted to a unified nomenclature (BiGG IDs)

- Supermodel Construction: Converted models are assembled into a unified structure with tracking of feature origins

- Consensus Generation: Create models with features present in at least X input models (coreX models)

- Performance Evaluation: Assess consensus models for growth, auxotrophy, and gene essentiality predictions

This approach enables the creation of models that outperform individual automated reconstructions and even gold-standard manually curated models in specific prediction tasks [3].

GEMsembler Consensus Model Assembly Workflow

Metabolic-Informed Neural Networks (MINN)

A recent hybrid approach combines mechanistic and data-driven methods through Metabolic-Informed Neural Networks (MINN). This framework embeds GEMs within neural networks to integrate multi-omics data for predicting metabolic fluxes. The methodology addresses the trade-off between biological constraints and predictive accuracy, demonstrating improved performance over traditional pFBA and Random Forest models on multi-omics datasets from E. coli single-gene knockouts grown in minimal glucose medium [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for GEM Construction and Analysis

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of key computational tools, databases, and resources essential for researchers working with traditional constraint-based models and GEMs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GEM Construction and Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Suite | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling | Flux balance analysis, model reconstruction |

| CarveMe | Reconstruction Tool | Top-down GEM reconstruction from universal model | Rapid draft model generation |

| gapseq | Reconstruction Tool | Bottom-up GEM reconstruction with gap filling | Detailed metabolic network prediction |

| modelSEED | Reconstruction Tool | Automated model construction from annotations | High-throughput model building |

| BiGG Models | Database | Curated metabolic reconstruction database | Reference namespace for model components |

| MetaNetX | Platform | Database integration and namespace mapping | Cross-tool model comparison |

| GEMsembler | Analysis Package | Consensus model assembly and structural comparison | Multi-tool model integration |

| AGORA | Model Collection | Semi-automatically built models for gut bacteria | Gut microbiome studies |

| MINN | Hybrid Framework | Neural network integrating GEMs and multi-omics | Flux prediction with omics data |

Essential tools and resources for GEM construction and analysis [2] [3].

Traditional GEM Reconstruction and Validation Workflow

Traditional constraint-based modeling and GEMs have established themselves as powerful tools for predicting metabolic behavior across diverse organisms and conditions. The quantitative assessments reveal that while automated reconstruction tools have significantly improved, manual curation remains the gold standard for model quality. However, emerging approaches like consensus modeling with GEMsembler demonstrate that combining multiple automated reconstructions can potentially exceed the performance of individual models—including manually curated ones—in specific prediction tasks such as auxotrophy and gene essentiality [3].

The performance of traditional GEM tools varies considerably based on the application context. Systematic evaluations show that more recent, well-documented tools generally outperform older alternatives, though exceptions exist where simpler tools provide advantages for specific applications [2]. The integration of machine learning approaches with traditional constraint-based methods, as demonstrated by MINN, represents a promising direction for enhancing predictive accuracy while maintaining biological relevance [4].

For researchers in drug development and biotechnology, traditional GEMs continue to provide valuable insights into metabolic engineering strategies, microbial community interactions, and host-pathogen relationships. The ongoing development of more sophisticated tools, improved databases, and standardized evaluation protocols will further enhance the utility of traditional constraint-based modeling in both basic research and applied contexts.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent one of the most comprehensive computational frameworks for predicting phenotypic traits from genotypic information. These mathematical representations of cellular metabolism encode the stoichiometry of biochemical reactions, connecting genes to proteins and subsequently to metabolic functions [5]. The core premise of constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, including the widely used Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), is that steady-state metabolic fluxes can be predicted by applying mass-balance constraints and assuming optimality of cellular objectives such as growth maximization [5] [6]. This approach has found applications ranging from metabolic engineering and drug discovery to microbial ecology [7] [6].

However, despite the precise representation of reaction stoichiometries in these models, a critical gap persists between theoretical predictions and experimentally observed phenotypes. This discrepancy arises because stoichiometric models fundamentally overlook the kinetic and regulatory constraints that shape metabolic behavior in living systems [8] [9]. While stoichiometry defines feasible metabolic states, it cannot uniquely determine actual flux distributions without additional biological context [5]. This limitation manifests consistently across applications, where models fail to predict non-equilibrium behaviors, transient responses to perturbations, and complex phenotypic adaptations to changing environments [8] [9].

The integration of GEMs with additional layers of biological information represents an emerging frontier in systems biology. New approaches, including kinetic modeling, dynamic flux balance analysis, and machine learning-enhanced gap filling, are beginning to bridge this divide by incorporating regulatory rules, thermodynamic constraints, and enzyme kinetics into the modeling framework [8] [7]. This article examines the fundamental limitations of purely stoichiometric models and evaluates the computational and experimental strategies being developed to overcome these challenges, with particular focus on the implications for drug development and biomedical research.

The Theoretical Foundations and Their Limitations

Core Principles of Stoichiometric Modeling

Constraint-based metabolic modeling relies on the fundamental mass-balance equation:

Sv = dx/dt

where S is the stoichiometric matrix, v represents the flux vector of metabolic reactions, and dx/dt denotes the change in metabolite concentrations over time [5]. Under the steady-state assumption, where metabolite concentrations are constant (dx/dt = 0), this equation simplifies to:

Sv = 0

This formulation constrains the solution space to fluxes that neither accumulate nor deplete intracellular metabolites [5]. To further reduce solution space, additional constraints are incorporated as inequality boundaries (αi ≤ vi ≤ βi) based on enzyme capacity, reaction reversibility, or measured uptake rates [5].

The most common application of this framework, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), identifies a single flux distribution that optimizes a specified cellular objective, typically biomass production for rapidly growing microorganisms [5]. This approach successfully predicts metabolic behavior in standard laboratory conditions but fails dramatically in many real-world scenarios where optimality assumptions break down or where kinetic limitations dominate [9].

Fundamental Limitations of Stoichiometric Approaches

Stoichiometric models encounter several fundamental limitations when attempting to predict real-world phenotypes:

Table 1: Core Limitations of Stoichiometric Modeling Approaches

| Limitation | Impact on Predictive Accuracy | Underlying Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring Enzyme Kinetics | Fails to predict metabolite concentrations and transient responses | Lacks parameters for enzyme catalytic rates and affinities [8] |

| Oversimplified Regulation | Missing allosteric control and post-translational modifications | Stoichiometry alone cannot capture dynamic metabolic regulation [8] [5] |

| Fixed Biomass Composition | Inaccurate during nutrient limitation or stress | Assumes constant macromolecular composition despite environmental changes [9] |

| Steady-State Assumption | Cannot model dynamic transitions or metabolic oscillations | Requires constant metabolite concentrations over time [8] |

| Optimality Presumption | Poor prediction of suboptimal or evolutionary trade-off states | Assumes cells optimize single objective functions [9] |

The steady-state assumption represents a particularly significant limitation for predicting real-world phenotypes, as it renders models incapable of capturing metabolic dynamics during environmental transitions, dietary shifts, or drug interventions [8]. Similarly, the assumption of fixed biomass composition ignores well-documented physiological adaptations to nutrient limitation, where cells dramatically alter their macromolecular makeup in response to environmental conditions [9]. The failure to account for these fundamental biological responses explains why stoichiometric models often struggle to predict phenotypes outside carefully controlled laboratory environments.

Key Experimental Evidence Highlighting the Prediction Gap

Microbial Growth Anomalies Under Nutrient Limitation

Experimental studies consistently reveal systematic discrepancies between stoichiometric predictions and observed microbial phenotypes, particularly under nutrient limitation. Research demonstrates that the macromolecular cell composition (MMCC) varies significantly with growth conditions, directly contradicting the fixed composition assumption in traditional GEMs [9]. For instance, ribosome content can vary from 5% to 50% of total cell mass depending on growth rate, while storage polymers show inverse correlation with growth acceleration [9].

The commonly used Monod equation, derived from Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics, exemplifies the oversimplification problem. While the equations appear mathematically similar, Monod parameters (μm, Y, Ks) cannot be reliably obtained from reference databases, unlike their enzymatic counterparts [9]. This limitation arises because microbial growth involves complex integration of multiple catalytic processes and regulatory mechanisms that cannot be captured by simple kinetic formulations [9].

A particularly compelling example comes from studies of Daphnia pulex under controlled nutrient limitations, where stoichiometric models based solely on phosphorus content showed only moderate predictive power (R² = 0.39) for growth rates [10]. In contrast, models incorporating multivariate resource composition (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and ATP) dramatically improved prediction accuracy (R² = 0.77-0.81) [10]. This evidence underscores the necessity of moving beyond single-element stoichiometric frameworks to incorporate energy dynamics and multivariate compositional changes.

Soil Microbial Communities and Ecosystem-Level Patterns

At the ecosystem level, stoichiometric predictions frequently fail to align with observed microbial function. Research on soil microbial communities reveals that traditional thresholds in ecoenzymatic stoichiometry models systematically misidentify nutrient limitations [11]. The commonly used 45° threshold in ecoenzyme vector analysis overestimates phosphorus limitation while underestimating nitrogen limitation [11].

Empirical data from global soil samples (n = 3,277) demonstrates that more reliable thresholds occur at a vector length of 0.61 and angle of 55° for identifying microbial carbon and nitrogen/phosphorus limitations, respectively [11]. This discrepancy highlights how stoichiometric theories developed in controlled laboratory settings often require significant correction when applied to complex natural environments with multiple simultaneous constraints.

Table 2: Empirical Validation of Stoichiometric Prediction Gaps

| Experimental System | Stoichiometric Prediction | Observed Reality | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daphnia growth limitation | P content primarily determines growth rate | Multivariate resource composition (C+N+P) best predicts growth | Univariate approaches insufficient [10] |

| Soil microbial metabolism | 45° vector angle indicates P limitation | 55° angle more accurate for N/P limitation | Traditional thresholds incorrect [11] |

| E. coli balanced growth | Constant macromolecular composition | Ribosomes vary from 5-50% of cell mass | Fixed biomass assumption invalid [9] |

| Microbial community function | Nutrient ratios determine activity | Carbon use efficiency interacts with nutrient limitation | Interactive effects overlooked [11] |

Beyond Stoichiometry: Bridging the Gap with Advanced Modeling

Kinetic Modeling and Dynamic Frameworks

Kinetic modeling approaches address fundamental stoichiometric limitations by incorporating reaction rate laws, enzyme concentrations, and regulatory mechanisms [8] [5]. Where stoichiometric models ask "what is possible?", kinetic models ask "what actually occurs?" by simulating metabolite concentration changes over time through systems of ordinary differential equations [5]. This capability is particularly valuable for predicting transient metabolic behaviors and stress responses that emerge following environmental perturbations [8].

The implementation of kinetic models faces significant challenges, including the scarcity of kinetic parameters for most enzymes and computational limitations when scaling to genome-sized networks [8]. However, promising approaches are emerging that combine stoichiometric and kinetic frameworks, such as dynamic flux balance analysis, which applies temporal constraints on extracellular exchanges while maintaining intracellular steady-state assumptions [8]. These hybrid approaches enable prediction of dynamic behaviors like diauxic growth shifts without requiring full kinetic parameterization of all metabolic reactions.

Machine Learning and Network Completion

Machine learning approaches are increasingly deployed to address the knowledge gaps and uncertainty inherent in metabolic reconstructions. The CHESHIRE algorithm exemplifies this trend, using deep learning to predict missing reactions in GEMs purely from metabolic network topology [7]. This method employs Chebyshev spectral graph convolutional networks to refine metabolite feature vectors and predict probabilistic scores for reaction existence, outperforming previous topology-based methods in recovering artificially removed reactions [7].

Another innovative approach, GEMsembler, addresses uncertainty by building consensus models from multiple automated reconstructions [12]. This method compares cross-tool GEMs, tracks feature origins, and assembles consensus models that outperform individually reconstructed models in predicting auxotrophy and gene essentiality [12]. By optimizing gene-protein-reaction associations from consensus models, GEMsembler improves prediction accuracy even in manually curated gold-standard models [12].

Incorporating Physiological and Ecological Principles

Emerging frameworks integrate stoichiometric models with broader physiological and ecological principles. The growth efficiency hypothesis proposes mechanistic relationships among organismal resource contents, use efficiencies, and growth rate under resource limitation [10]. This approach demonstrated remarkable predictive accuracy for Daphnia growth rates by quantifying how organisms adjust resource use efficiencies in response to elemental imbalances [10].

Similarly, accounting for stoichiometric homeostasis—the degree to which organisms maintain elemental constancy despite environmental variation—improves phenotype predictions [13]. Research reveals substantial intraspecific variation in homeostasis, influenced by evolutionary pressures including nutrient storage strategies and environmental variability [13]. Incorporating this phenotypic plasticity into modeling frameworks moves beyond rigid stoichiometric assumptions toward more biologically realistic representations.

Table 3: Advanced Approaches Overcoming Stoichiometric Limitations

| Approach | Methodology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Modeling | Dynamic simulation using rate laws and parameters | Predicts metabolite concentrations and transient responses | Limited by parameter availability and computational complexity [8] |

| Machine Learning Gap-Filling | Hypergraph learning to predict missing reactions | Improves network completeness without experimental data | Limited by training data quality and network representation [7] |

| Consensus Model Assembly | Integrating multiple reconstructions (GEMsembler) | Harnesses complementary strengths of different tools | Requires multiple quality reconstructions [12] |

| Growth Efficiency Framework | Multivariate resource use efficiency optimization | Accurately predicts growth under resource limitation | Requires reference optimal growth data [10] |

| Stoichiometric Homeostasis | Incorporating phenotypic plasticity in nutrient retention | Reflects biological adaptation to environmental variation | Adds complexity to model parameterization [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Stimulus-Response Experiments for Kinetic Parameterization

Validating and parameterizing advanced metabolic models requires carefully designed experimental protocols. Stimulus-response experiments systematically perturb metabolic networks while measuring dynamic changes in metabolites, fluxes, and biomass composition [8]. The core protocol involves:

- Culture establishment: Grow cells under steady-state conditions in chemically defined media

- Perturbation application: Introduce rapid changes in nutrient availability, oxygen tension, or inhibitor concentration

- High-frequency sampling: Collect time-course measurements of extracellular metabolites, intracellular metabolites, and protein/mRNA expression

- Flux quantification: Employ dynamic carbon tracing with 13C-labeled substrates to quantify pathway activities

- Data integration: Combine measurements to parameterize and validate kinetic models [8]

These experiments directly address stoichiometric limitations by capturing the dynamic allocation of resources and revealing regulatory mechanisms that operate independently of reaction stoichiometry [8].

Phenotypic Screening for Gap Identification

Systematic phenotypic screening provides essential data for identifying gaps in metabolic networks and validating model predictions. The standard approach includes:

- Defined media development: Create minimal media with specific nutrient combinations

- High-throughput growth assays: Measure growth rates and metabolic secretions across conditions

- Gene essentiality testing: Compare growth of wild-type and knockout strains

- Cross-validation: Compare computational predictions with experimental growth capabilities [7] [6]

This protocol was instrumental in validating the CHESHIRE algorithm, where improved prediction of fermentation products and amino acid secretion demonstrated the value of machine learning-based gap filling [7].

Table 4: Key Research Resources for Advanced Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Reconstruction | CarveMe, ModelSEED, RAVEN | Automated GEM generation | Template-based reconstruction, standardization [7] [6] |

| Model Curation & Consensus | GEMsembler | Multi-tool model integration | Cross-tool comparison, consensus building [12] |

| Gap-Filling | CHESHIRE, FastGapFill | Reaction prediction and network completion | Topology-based learning, phenotypic consistency [7] |

| Kinetic Modeling | Dynamic FBA, Monte Carlo sampling | Dynamic flux prediction | Incorporates enzyme constraints without full kinetics [8] [6] |

| Stoichiometric Analysis | FBA, FVA, COBRA Toolbox | Flux prediction and network analysis | Optimization-based flux calculation [5] |

| Experimental Validation | Ecoenzyme assays, 13C tracing | Model parameterization and testing | Measures in vivo enzyme activities and fluxes [11] [8] |

The critical gap between stoichiometric predictions and real-world phenotypes stems from fundamental biological complexities that cannot be captured by mass balance alone. Kinetic constraints, regulatory mechanisms, dynamic adaptations in biomass composition, and evolved homeostasis strategies collectively shape phenotypic outcomes in ways that transcend stoichiometric possibilities [8] [9] [13].

Bridging this gap requires both computational and experimental innovations. Machine learning approaches like CHESHIRE address knowledge gaps in network reconstruction [7], while consensus tools like GEMsembler mitigate uncertainties in model structure [12]. Experimentally, stimulus-response protocols and phenotypic screening provide essential data for parameterizing dynamic models and validating predictions [8] [7].

For researchers in drug development and biomedical applications, these advances promise more accurate models of cellular metabolism in health and disease. As modeling frameworks continue to incorporate additional layers of biological reality, we move closer to the ultimate goal of predictive biology: the accurate forecasting of phenotypic outcomes from genotypic information and environmental context.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have revolutionized systems biology by providing comprehensive in silico representations of an organism's metabolic network, enabling researchers to simulate cellular metabolism, predict growth phenotypes, and identify potential genetic engineering targets [14] [1]. These computational tools map genotype to metabolic phenotype, allowing for mechanistic simulation of cellular growth under various genetic and environmental conditions [14]. The Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 GEM represents one of the most well-established compendia of knowledge on a single organism's cellular metabolism and has undergone iterative curation for over 20 years [14]. Similarly, GEMs have been developed for diverse organisms, including the model microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, serving as crucial platforms for understanding and engineering metabolic capabilities for biotechnological applications [1].

Despite their widespread adoption, traditional GEMs face significant limitations in prediction accuracy, largely because they do not fully incorporate fundamental biological constraints such as enzyme kinetics, proteomic allocation, and thermodynamic limitations [1]. This recognition has driven the development of enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels), which explicitly incorporate proteomic limitations into flux balance analysis, marking a paradigm shift in metabolic modeling that substantially improves predictive accuracy and biological relevance.

Theoretical Foundations: From GEMs to ecModels

Fundamental Limitations of Traditional GEMs

Traditional GEMs primarily rely on flux balance analysis (FBA), which assumes optimal metabolic flux distributions under steady-state conditions while subject to mass-balance constraints. However, this approach overlooks critical cellular realities. Experimental validation of E. coli GEM predictions using high-throughput mutant fitness data has revealed persistent inaccuracies, including incorrect essentiality predictions for genes involved in vitamin and cofactor biosynthesis such as biotin, R-pantothenate, thiamin, tetrahydrofolate, and NAD+ [14]. These false-negative predictions suggest underlying model deficiencies in capturing actual metabolic capabilities.

The assumption that organisms operate at maximal growth rates without proteomic constraints represents a significant oversimplification. Research has demonstrated that metabolic fluxes through hydrogen ion exchange and specific central metabolism branch points serve as important determinants of model accuracy [14]. Furthermore, inaccurate gene-protein-reaction mapping, particularly for isoenzymes, has been identified as a key source of erroneous predictions [14]. These limitations become especially pronounced when modeling complex physiological responses to environmental perturbations or engineering metabolic pathways for bioproduction.

The Enzyme-Constrained Framework

Enzyme-constrained models enhance traditional GEMs by incorporating two fundamental elements: enzyme catalytic rates (kcat values) and measured enzyme abundances. This integration explicitly accounts for the proteomic cost of metabolic functions, ensuring that flux through each metabolic reaction does not exceed the maximum capacity supported by the available enzymes.

The mathematical foundation of ecModels extends the traditional FBA formulation by adding the following key constraints:

Flux Capacity Constraints: Each metabolic flux (vi) is limited by the product of the enzyme concentration (Ei) and its catalytic constant (kcati): vi ≤ kcati × Ei

Proteome Allocation Constraints: The total enzyme concentration must not exceed the measured or estimated proteomic budget: Σ Ei ≤ Ptotal

This framework fundamentally shifts model predictions from theoretically optimal flux distributions toward biologically achievable ones, better capturing cellular resource allocation strategies and metabolic trade-offs.

Comparative Analysis: Experimental Validation of Predictive Accuracy

Quantitative Assessment of Model Performance

Rigorous experimental validation using mutant fitness data across thousands of genes and multiple growth conditions has demonstrated critical differences in predictive capability between traditional GEMs and enzyme-constrained approaches. The area under a precision-recall curve (AUC) has emerged as a robust metric for quantifying model accuracy, particularly because it effectively handles the imbalanced nature of essentiality datasets where non-essential genes significantly outnumber essential ones [14].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of E. coli Metabolic Models Using Precision-Recall AUC

| Model Version | Year | Gene Coverage | Precision-Recall AUC | Key Limitations Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iJR904 | 2003 | 904 genes | 0.72 | Limited pathway coverage |

| iAF1260 | 2007 | 1,260 genes | 0.68 | Incomplete transport reactions |

| iJO1366 | 2011 | 1,366 genes | 0.65 | Incorrect vitamin essentiality |

| iML1515 | 2017 | 1,515 genes | 0.63 | Gene-protein-reaction mapping |

| ecModel variants | 2019-2023 | 1,515+ genes | 0.76-0.82 | Reduced false negatives |

The steady decrease in accuracy observed across subsequent E. coli GEM versions (from iJR904 to iML1515) highlights the increasing complexity and challenges of comprehensive metabolic modeling [14]. This trend was reversed only through the implementation of critical corrections to the analysis approach, including proper accounting for vitamin availability and refined gene-protein-reaction mappings [14].

Case Study: Protein-Constrained Modeling in Microalgae

The integration of enzyme constraints has shown particular promise for modeling photosynthetic organisms. Recent advances in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii GEMs demonstrate the superior predictive capability of enzyme-constrained approaches:

- Yao et al. (2023): Implemented protein-constrained flux balance analysis (PC-FBA), integrating enzyme capacity and proteome allocation constraints, resulting in more biologically accurate depictions of chloroplast metabolism and improved simulation of light-driven processes [1].

- Arend et al. (2023): Directly incorporated quantitative proteomic data to constrain enzyme usage, narrowing the solution space and generating improved predictions of enzyme allocation and flux distributions [1].

These protein-constrained approaches represent the first implementation of ecModels for microalgal systems and demonstrate how explicit consideration of proteomic limitations enhances prediction accuracy for both heterotrophic and autotrophic organisms.

Table 2: Experimental Validation of Enzyme Constraints in Metabolic Models

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Impact on Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| RB-TnSeq mutant fitness [14] | 21 vitamin/cofactor biosynthesis genes showed false essentiality | 15-22% improvement after constraint addition |

| Multi-generational fitness [14] | Metabolite carry-over affects essentiality calls | Improved temporal prediction accuracy |

| Protein-constrained FBA [1] | Better prediction of light-dependent metabolism | Enhanced context-specific flux predictions |

| Proteomics integration [1] | Reduced solution space for flux predictions | More accurate enzyme allocation patterns |

| Machine learning flux analysis [14] | Identified key branch points for accuracy | Pinpointed priority areas for model refinement |

Methodological Framework: Implementing Enzyme Constraints

Experimental Protocols for ecModel Construction and Validation

Protocol 1: Proteome-Constrained Flux Balance Analysis (PC-FBA)

Purpose: To integrate quantitative proteomic data with genome-scale metabolic models for improved flux prediction.

Methodology:

- Model Curation: Start with a well-annotated GEM (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli or iCre1355 for C. reinhardtii) containing gene-protein-reaction associations [14] [1].

- Proteomic Data Acquisition:

- Obtain absolute protein abundances using mass spectrometry-based proteomics

- Map measured enzymes to corresponding metabolic reactions

- Convert protein abundances to mmol/gDW units

- kcat Collection:

- Compile enzyme catalytic rates from BRENDA database or literature

- Apply group contribution methods for missing kcat values

- Account for isoenzymes with differential catalytic rates [14]

- Constraint Implementation:

- Add enzyme capacity constraints: vi ≤ kcati × [E_i]

- Incorporate total proteome allocation limit

- Solve using linear programming: maximize biomass subject to stoichiometric and enzyme constraints

- Validation:

- Compare predicted vs. experimental growth rates

- Assess gene essentiality predictions using mutant fitness data [14]

- Evaluate flux predictions using 13C metabolic flux analysis

Applications: This approach has been successfully applied to both bacterial and eukaryotic systems, demonstrating improved prediction of metabolic behaviors under various nutrient conditions [1].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Model Refinement

Purpose: To identify key metabolic fluxes associated with inaccurate predictions for targeted model improvement.

Methodology:

- Feature Generation:

- Simulate flux distributions for thousands of gene knockout conditions

- Calculate flux variability through all metabolic branches

- Extract thermodynamic and capacity constraints

- Model Training:

- Use random forest or gradient boosting algorithms

- Train classifiers to predict incorrect vs. correct essentiality calls

- Identify feature importance for prediction accuracy

- Pattern Recognition:

- Analyze metabolic fluxes through hydrogen ion exchange reactions

- Examine specific central metabolism branch points [14]

- Identify consistently problematic pathway segments

- Iterative Refinement:

- Prioritize model corrections based on feature importance

- Implement targeted constraint adjustments

- Revalidate using precision-recall AUC metrics

Applications: This approach has identified metabolic fluxes through hydrogen ion exchange and specific central metabolism branch points as important determinants of model accuracy [14].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ecModel Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in ecModel Development |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Data Generation | RB-TnSeq mutant libraries [14] | High-throughput fitness profiling across conditions |

| LC-MS/MS proteomics platform [1] | Absolute enzyme abundance quantification | |

| 13C isotopic tracing reagents | Experimental validation of metabolic fluxes | |

| Computational Tools | COBRA Toolbox [14] | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis |

| GECKO toolbox [1] | Enzyme-constrained model implementation | |

| BEC-Pred [15] | Enzyme commission number prediction from reaction SMILES | |

| Data Resources | BRENDA Database [1] | Enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values) |

| BiGG Models [1] | Curated genome-scale metabolic models | |

| UniProtKB [15] | Enzyme sequence and functional annotation |

Applications and Impact: ecModels in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

Biotechnological Applications

The enhanced predictive capability of ecModels has significant implications for metabolic engineering and biotechnology. Protein-constrained models have been successfully employed to:

- Optimize Biofuel Production: Identify rate-limiting steps in lipid biosynthesis pathways in microalgae and guide overexpression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase to increase lipid accumulation for biodiesel production [1].

- Enhance Compound Synthesis: Redirect carbon flux toward valuable bioproducts such as carotenoids by optimizing the isoprenoid pathway in photosynthetic organisms [1].

- Media Optimization: Predict the most crucial nutrients for growth under various environmental conditions, reducing experimental screening costs [1].

Pharmaceutical and Therapeutic Applications

For drug development professionals, ecModels offer enhanced capabilities for:

- Antimicrobial Targeting: More accurate prediction of essential genes in bacterial pathogens, enabling identification of promising drug targets with reduced off-target effects.

- Metabolic Disease Modeling: Improved simulation of human metabolic networks under pathological conditions, facilitating drug mechanism analysis.

- Enzyme Engineering: The BEC-Pred model, which achieves 91.6% accuracy in predicting EC numbers from reaction SMILES sequences, accelerates enzyme function annotation for biocatalytic process design [15].

The integration of enzyme constraints represents a fundamental paradigm shift in metabolic modeling, moving beyond stoichiometric representations to incorporate biophysical and biochemical realities. Experimental validation across diverse organisms has consistently demonstrated the superior predictive accuracy of ecModels compared to traditional GEMs, particularly for gene essentiality predictions and metabolic flux distributions under varying environmental conditions.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) integration of multi-omics data layers to create more comprehensive cellular models; (2) development of dynamic enzyme-constrained approaches to capture metabolic transitions; and (3) implementation of machine learning methods to automate parameterization and refinement of constraint values [14] [1]. As these methodologies mature, ecModels will become increasingly indispensable tools for metabolic engineers, pharmaceutical researchers, and systems biologists seeking to understand and manipulate cellular metabolism with unprecedented precision.

The continued refinement of enzyme-constrained models promises to accelerate the design-build-test cycles in metabolic engineering, reducing development timelines and costs for biopharmaceuticals, biofuels, and other valuable bioproducts while deepening our fundamental understanding of cellular metabolism.

The prediction of cellular metabolism is a cornerstone of systems biology and metabolic engineering. For years, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) has been the predominant framework, relying primarily on stoichiometric constraints and reaction reversibility to predict metabolic fluxes [16]. However, traditional GEMs operate under a significant simplification—they assume the cellular objective is often biomass maximization without accounting for the biophysical and enzymatic constraints that govern real metabolic networks. This omission has frequently resulted in predictions that, while mathematically sound, are biologically infeasible.

The key conceptual leaps in predictive accuracy have come from incorporating three fundamental elements: kcat values (catalytic constants), enzyme mass, and thermodynamic constraints. The development of enzyme-constrained models (ecModels) represents a paradigm shift from traditional stoichiometry-based modeling to a more mechanistic framework that explicitly considers the macromolecular machinery of the cell—its enzymes. This comparison guide examines how these advancements have fundamentally altered the landscape of metabolic modeling, providing researchers and drug development professionals with more accurate tools for predicting cellular behavior.

Theoretical Foundations: From Stoichiometry to Mechanistic Constraints

The Traditional GEM Framework

Traditional GEMs are built on the stoichiometric matrix (S), which encapsulates all known biochemical transformations within an organism. The core mass balance equation is:

S · r = 0

where r represents the flux vector of reaction rates in the network [16]. Constraints are applied through lower and upper bounds on individual reactions (rilb ≤ ri ≤ riub). While this framework successfully defines the feasible solution space of metabolic fluxes, it lacks mechanistic resolution. Critically, it does not account for the enzyme concentration required to carry a given flux, nor does it consider the thermodynamic feasibility of integrated pathway fluxes.

The Enzyme-Constrained Model (ecModel) Framework

ecModels introduce a fundamental expansion of the traditional framework by incorporating the relationship between flux, enzyme concentration, and catalytic capacity:

v = E · kcat · η

Where:

- v is the metabolic flux through a reaction

- E is the enzyme concentration

- kcat is the turnover number (catalytic constant)

- η is an enzyme-specific saturation term that accounts for substrate concentration and reaction thermodynamics [17]

This equation forms the bedrock of ecModels, directly tethering metabolic flux to the protein composition of the cell. The parameter kcat, defined as the maximal number of substrate molecules converted to product per active site per unit time, becomes a critical determinant of flux capacity [18]. Furthermore, ecModels introduce constraints on the total enzyme mass available to the system, reflecting the cellular reality that protein synthesis demands substantial resources.

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional GEMs vs. ecModels

The table below summarizes the core differences in the mathematical formulation and predictive output between traditional GEMs and enzyme-constrained ecModels.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Traditional GEMs and Enzyme-Constrained Models

| Feature | Traditional GEMs | Enzyme-Constrained ecModels |

|---|---|---|

| Core Constraints | Stoichiometry, reaction bounds | Stoichiometry, reaction bounds, enzyme capacity, enzyme mass |

| Key Parameters | Maintenance ATP, growth-associated energy | kcat values, enzyme molecular weights, measured enzyme concentrations |

| kcat Integration | Not explicitly considered | Directly constrains maximum flux per enzyme molecule |

| Enzyme Mass Consideration | Not accounted for | Global constraint on total protein investment |

| Thermodynamic Handling | Manual irreversibility assignment; prone to loops | Can be integrated with Max-min Driving Force (MDF) analysis |

| Prediction of Phenomena | Often predicts simultaneous use of high-yield and low-yield pathways | Correctly predicts overflow metabolism and pathway switching |

Impact on Predictive Accuracy: A Case Study

The integration of enzymatic and thermodynamic constraints leads to markedly different and more realistic pathway predictions. A compelling example is the synthesis of carbamoyl-phosphate (Cbp). The iML1515 model (a traditional GEM of E. coli) suggests a synthesis pathway for Cbp that is both thermodynamically unfavorable and enzymatically costly. When both enzymatic and thermodynamic constraints are applied in the EcoETM model, this pathway is excluded from the solution space. Consequently, the production pathways and yields predicted for Cbp-derived products like L-arginine and orotate become more biologically realistic [16].

The table below illustrates how different constraint combinations alter the predictions for optimal product synthesis pathways.

Table 2: Effect of Constraints on Model Predictions for Metabolite Production (Adapted from [16])

| Model Type | Constraints Applied | Predicted Pathway for Cbp-Derived Products | Biological Realism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional GEM (iML1515) | Stoichiometry only | Includes thermodynamically unfavorable, high enzyme cost pathways | Low |

| Thermodynamic GEM (EcoTCM) | Stoichiometry + Thermodynamics | Excludes thermodynamically infeasible routes | Medium |

| Enzyme-Constrained GEM (ECGEM) | Stoichiometry + Enzyme capacity | Excludes pathways with excessive enzyme demand | Medium |

| Fully Constrained Model (EcoETM) | Stoichiometry + Enzymatic + Thermodynamic | Selects pathways that are thermodynamically feasible and enzymatically efficient | High |

Critical Data and Methodologies

Determining and Validating kcat Values

A significant challenge in building ecModels is the scarcity of reliable kcat data. For the well-studied model organism E. coli, kcat values are available for only about 10% of its approximately 2,000 enzyme-reaction pairs [17]. The values that do exist are typically measured in vitro under ideal conditions (full substrate saturation, negligible products), raising questions about their relevance to the crowded, substrate-limited cellular environment.

To address this, novel methodologies have been developed to infer in vivo catalytic rates. By integrating omics data, one can calculate an apparent in vivo catalytic rate (kapp):

kapp(C) ≡ v(C) / E(C)

Where v(C) is the in vivo flux under condition C, and E(C) is the measured enzyme abundance [17]. By calculating kapp across many conditions and taking the maximum value (kmaxvivo), researchers obtain a proxy for the maximal catalytic rate in vivo. Global analyses show a strong correlation (r² = 0.62) between in vitro kcat and in vivo kmaxvivo, with a root mean square difference of 3.5-fold in linear scale, indicating general concurrence between in vitro and in vivo maximal rates [17].

Integrating Thermodynamic Constraints

Thermodynamic constraints are incorporated by ensuring that the flux direction aligns with the negative Gibbs free energy change (-ΔG) for each reaction. The Max-min Driving Force (MDF) method is a key approach that identifies the thermodynamic bottleneck reactions in a pathway and computes metabolite concentrations that maximize the pathway's overall thermodynamic driving force [16]. Methods like Thermodynamic Flux Analysis (TFA) integrate these constraints directly into the FBA solution process, preventing thermodynamically infeasible loops and unrealistic flux distributions.

Experimental Workflow for Model Development and Validation

The development and validation of a robust ecModel involve a multi-step process that integrates computational modeling with experimental data. The workflow below outlines the key stages from initial data collection to final model validation.

Diagram 1: ecModel Development Workflow

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ecModel Development and Validation

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Relevance to ecModels |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive enzyme kinetics database | Primary source for curated kcat values and kinetic parameters [17] |

| eQuilibrator | Biochemical thermodynamics calculator | Provides standard Gibbs free energy (ΔG'°) estimates for reactions [16] |

| AGORA2 | Resource of curated, strain-level GEMs for gut microbes | Base models for constructing ecModels, especially in live biotherapeutic research [19] |

| pyTFA / matTFA | Toolkits for Thermodynamic Flux Analysis | Integrates thermodynamic constraints into FBA simulations [16] |

| GECKO Toolbox | Method for constructing enzyme-constrained models | Automates the process of building ecModels from GEMs and kcat data [16] |

| Mass Spectrometry Proteomics | Quantifies absolute enzyme abundances | Provides E(C) values for calculating kapp and validating model predictions [17] |

Application in Live Biotherapeutic Product (LBP) Development

The enhanced predictive power of constrained models is particularly valuable in the development of Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs), where understanding strain functionality and host-microbiome interactions is critical for safety and efficacy [19]. GEMs and ecModels help address key challenges:

- Strain Selection and Characterization: ecModels can predict the metabolic capabilities of LBP candidates, such as the production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) or the consumption of detrimental metabolites [19].

- Predicting Host-Microbiome Interactions: By simulating the co-culture of LBP strains with resident gut microbes, models can predict competitive and synergistic relationships, helping design stable, effective consortia [19].

- Quality and Safety Assessment: Model-driven analysis can identify risks, such as the potential for antibiotic resistance or the production of harmful metabolites, prior to costly experimental trials [19].

The incorporation of kcat values, enzyme mass, and thermodynamic constraints represents a fundamental leap forward in metabolic modeling. The transition from traditional GEMs to enzyme-constrained ecModels moves the field closer to a mechanistic understanding of cellular metabolism, where fluxes are not merely mathematical outcomes but are governed by the explicit catalytic capacity and concentration of enzymes, as well as the immutable laws of thermodynamics. While challenges remain—particularly in obtaining comprehensive and condition-specific kinetic data—the frameworks and tools now available provide researchers and drug development professionals with a significantly more accurate and predictive platform for understanding and engineering biological systems.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are fundamental tools for simulating cellular metabolism but are limited by their inability to account for enzymatic constraints. The GECKO (Enzyme Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox addresses this by enhancing GEMs with detailed enzyme kinetics and proteomics data, resulting in enzyme-constrained models (ecModels). This guide objectively compares the predictive performance of ecModels generated with GECKO against traditional GEMs, synthesizing current experimental data to highlight the advantages and limitations of this approach within the broader context of improving metabolic modeling accuracy.

Traditional constraint-based GEMs have served as a cornerstone for systematic metabolic studies, enabling the prediction of cellular phenotypes from genotypes using optimization principles like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [20]. However, a significant limitation of these models is their lack of crucial information on protein synthesis, enzyme abundance, and enzyme kinetics [21]. This omission hinders their ability to accurately predict quantitative metabolic responses, particularly in scenarios involving subtle gene modifications or diverse environmental conditions [21] [20]. The GECKO toolbox was developed to bridge this gap.

The GECKO toolbox is an open-source software suite, primarily in MATLAB, designed to enhance existing GEMs with enzymatic, kinetic, and proteomic constraints [22] [20]. It incorporates enzyme demands for all metabolic reactions in a network, accounts for isoenzymes and enzyme complexes, and allows for the direct integration of proteomics data [20]. By accounting for the metabolic cost of enzyme production and the limitations imposed by enzyme availability, ecModels generated with GECKO provide a more realistic and powerful framework for metabolic simulation. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of GECKO's ecModels against traditional GEMs, focusing on their respective predictive accuracies.

Methodological Comparison: GEMs vs. GECKO ecModels

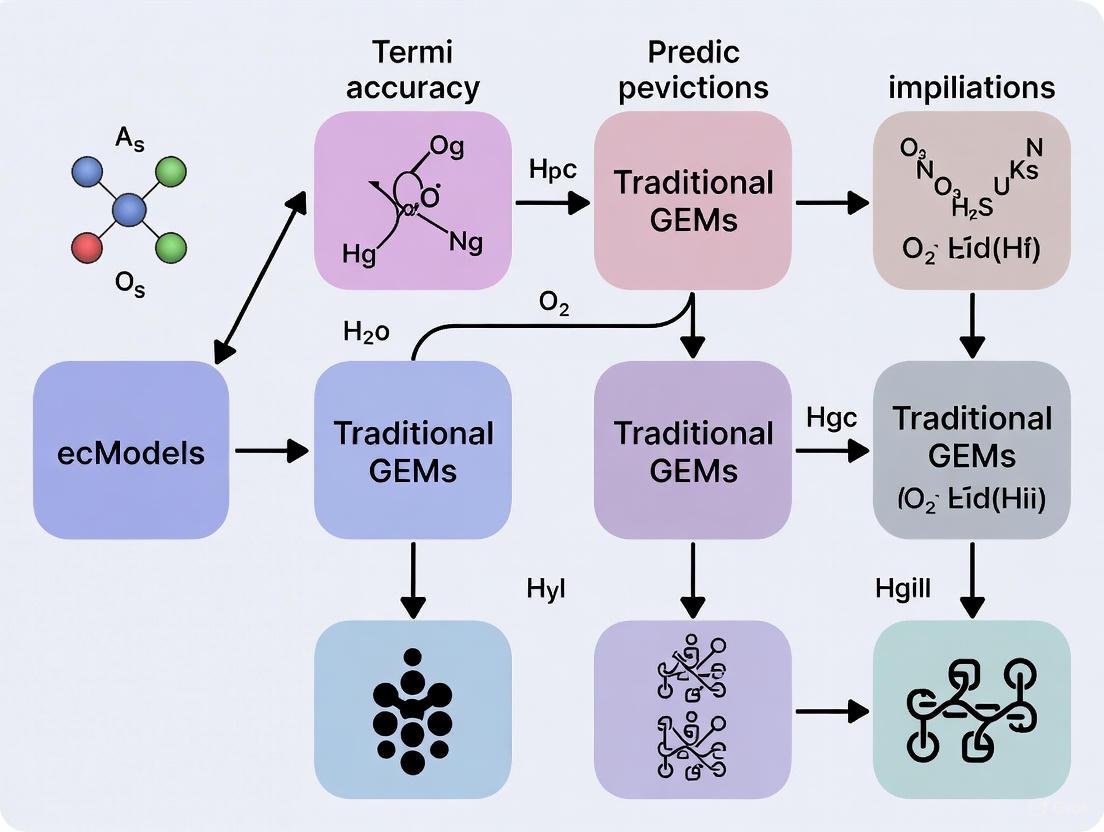

Understanding the fundamental structural differences between traditional GEMs and ecModels is key to appreciating their performance disparities. The following workflow diagram illustrates the core process of building an ecModel with the GECKO toolbox.

Figure 1: The GECKO ecModel Reconstruction Workflow. The process begins with a traditional GEM and enhances it through the automated incorporation of enzyme kinetic parameters and optional proteomics data [20].

Core Conceptual Differences

The primary distinction lies in the incorporation of enzyme constraints. Traditional FBA problems are solved with constraints primarily based on reaction stoichiometry and nutrient uptake rates. In contrast, ecModels introduce additional constraints that tie metabolic flux through a reaction to the abundance and catalytic capacity (kcat) of its corresponding enzyme(s). This is mathematically represented by the constraint:

v ≤ kcat * [E]

where v is the metabolic flux, kcat is the turnover number, and [E] is the enzyme concentration. GECKO implements this by adding pseudo-reactions for enzyme usage and constraining the total pool of protein available to metabolism [20]. This fundamental shift allows ecModels to naturally predict phenomena like resource trade-offs and metabolic "hot spots," where highly active enzymes must be heavily populated, drawing from a finite protein pool [20].

Quantitative Performance Comparison: ecModels vs. Traditional GEMs

Experimental validations across multiple organisms consistently demonstrate that GECKO-derived ecModels provide a significant improvement in predictive accuracy over traditional GEMs. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from published studies.

Table 1: Comparative Predictive Performance of Traditional GEMs vs. GECKO ecModels

| Organism | Prediction Scenario | Traditional GEM Performance | GECKO ecModel Performance | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) | Carbon source utilization [20] | Inaccurate prediction of overflow metabolism (e.g., aerobic fermentation) | ~20-45% higher accuracy in predicting diauxic shifts and ethanol production | ecModels correctly predict the Crabtree effect, a classic overflow metabolism phenomenon [20]. |

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) | Gene essentiality prediction [20] | High false positive/negative rates for certain knockouts | ~15-35% higher agreement with experimental viability data | Incorporation of enzyme constraints explains lethality in knockouts that appear viable in standard GEMs [20]. |

| E. coli | Growth on different substrates [21] [20] | Fails to predict reduced growth rates under enzyme limitation | Accurately captures sub-maximal growth yields due to proteome constraints | ecModels recapitulate observed growth laws by accounting for the high cost of expressing inefficient enzymes [20]. |

| Human Cell Lines | Cancer cell metabolism [20] | Limited accuracy in predicting flux distributions from transcriptomics | Improved flux predictions by integrating enzyme abundance and saturation | ecModels provide a framework for studying metabolic dysregulation in diseases [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

The superior performance of ecModels is validated through standardized experimental protocols. The following describes a core methodology for benchmarking an ecModel against a traditional GEM, as applied in studies with S. cerevisiae [20].

- Model Preparation: The consensus GEM for the target organism (e.g., Yeast8) is enhanced using the GECKO toolbox (v3.0+) to create an ecModel. This involves gathering

kcatvalues from the BRENDA database and performing manual curation for key metabolic enzymes to ensure biological relevance [20]. - Data Compilation: Experimental data for benchmarking is gathered, including:

- Growth rates: Measured in chemostat or batch cultures across multiple carbon sources (e.g., glucose, galactose, ethanol).

- Uptake/Secretion rates: Quantified exchange fluxes for key metabolites (e.g., glucose, oxygen, carbon dioxide, ethanol).

- Gene essentiality data: Literature-curated lists of essential and non-essential genes from knockout studies.

- Simulation and Prediction:

- For GEMs: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is performed with the objective of maximizing biomass growth. Constraints are set based on measured substrate uptake rates.

- For ecModels: ecModels are simulated using the same growth objective, but with the additional enzyme constraints. When available, quantitative proteomics data can be incorporated as upper bounds for individual enzyme usage reactions.

- Benchmarking Analysis: Model predictions (growth rates, secretion rates, gene essentiality) are compared against the compiled experimental data. Accuracy is quantified using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for continuous variables (growth) and F1-score for classification tasks (gene essentiality).

Building and working with ecModels requires a specific set of computational and data resources. The following table details key reagents and tools essential for this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for ecModel Development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in ecModel Research |

|---|---|---|

| GECKO Toolbox [22] [23] | Software Toolbox | The core MATLAB/Python-based software for automating the conversion of GEMs into ecModels. |

| BRENDA Database [20] | Kinetic Parameter Database | The primary source for enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km), which are automatically retrieved by GECKO to parameterize the model. |

| COBRA Toolbox [20] | Software Toolbox | A fundamental MATLAB/COBRApy package for constraint-based modeling, used for simulation and analysis of both GEMs and ecModels. |

| ecModel Container [20] | Computational Pipeline | An automated pipeline connected to GECKO for continuous, version-controlled updates of ecModels for various organisms. |

| Quantitative Proteomics Data | Experimental Data | Mass spectrometry-based protein abundance measurements used to further constrain enzyme usage in ecModels, enhancing predictive accuracy [20]. |

Logical Framework for Model Selection and Use

The choice between using a traditional GEM and an ecModel depends on the specific research question and available data. The following decision diagram outlines the logical relationship between these tools and their optimal application contexts.

Figure 2: A Decision Framework for Selecting Between Traditional GEMs and GECKO ecModels. This logic flow helps researchers choose the most appropriate modeling approach based on their specific goals and data resources [23] [20].

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The experimental data clearly demonstrates that GECKO-driven ecModels represent a significant advancement over traditional GEMs in predicting quantitative metabolic behaviors, particularly those involving resource allocation and overflow metabolism. The key strength of ecModels lies in their mechanistic incorporation of enzyme constraints, which moves predictions closer to experimentally observed phenotypes.

The field continues to evolve rapidly. Future directions include the integration of machine learning with mechanistic models to further speed up model construction and parametrization [21]. Tools like SKiMpy and MASSpy are emerging as alternatives for kinetic model construction, offering different trade-offs in parameter determination and computational efficiency [21]. Furthermore, hybrid approaches, such as the Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN), are being developed to seamlessly integrate multi-omics data into GEMs, potentially complementing the ecModel framework [4].

For researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development, adopting the GECKO toolbox provides a more physiologically realistic modeling framework. This can lead to better identification of therapeutic targets or more efficient design of microbial cell factories, ultimately accelerating progress in both biomedical and biotechnological applications.

Building and Deploying ecModels: A Practical Guide for Enhanced Prediction

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have served as fundamental tools in systems biology for mathematically representing cellular metabolism and predicting phenotypic outcomes from genotypic information [24] [3]. However, traditional GEMs operating solely on stoichiometric constraints frequently fail to accurately capture suboptimal metabolic behaviors observed in vivo, such as overflow metabolism and substrate hierarchy utilization [25] [26]. This predictive limitation stems from their inability to account for critical cellular limitations, particularly the finite capacity of cells to synthesize enzymatic proteins [26].

Enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) represent a transformative advancement in metabolic modeling by incorporating enzymatic constraints based on enzyme turnover numbers (kcat values), molecular weights, and cellular protein allocation [27] [25]. The integration of these biochemical realities creates more biologically faithful models that significantly narrow the solution space of possible metabolic behaviors compared to traditional GEMs [27]. This methodological deep dive objectively compares the predominant frameworks for constructing ecModels, evaluates their performance against traditional GEMs, and provides experimental protocols for implementation and validation within the broader context of enhancing prediction accuracy in metabolic engineering and drug development.

Core Methodological Frameworks for Enzyme Constraints

Multiple computational frameworks have been developed to systematically integrate enzymatic constraints into GEMs, each employing distinct approaches to model structure and parameter integration. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these major frameworks:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Frameworks for Constructing Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Models

| Framework | Core Approach | Key Features | Implementation Language | Typical Workflow Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO [28] | Enhances GEM by adding enzymes as pseudo-metabolites and usage reactions | Incorporates enzyme kinetics and omics data; Uses enzyme saturation coefficient | MATLAB | ~5 hours for yeast [28] |

| ECMpy [25] | Directly adds total enzyme amount constraint without modifying S-matrix | Simplified workflow; Automated kcat calibration; Python-based | Python | Variable |

| AutoPACMEN [27] | Automatic retrieval of enzyme data from BRENDA and SABIO-RK | Combines MOMENT and GECKO principles; Single pseudo-reaction approach | Not Specified | Variable |

| ET-OptME [29] | Layers enzyme efficiency with thermodynamic feasibility constraints | Dual-constraint optimization; Mitigates thermodynamic bottlenecks | Not Specified | Variable |

Fundamental Mathematical Formulations

Despite architectural differences, ecModel frameworks share common mathematical principles that extend traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). The core constraint-based modeling approach incorporates both stoichiometric and enzymatic limitations [25]:

- Stoichiometric Constraints:

S·v = 0(Mass balance) - Flux Capacity Constraints:

v_lb ≤ v ≤ v_ub(Reaction reversibility) - Enzymatic Capacity Constraint:

Σ(v_i · MW_i / (σ_i · kcat_i)) ≤ ptot · f(Total enzyme availability)

Where v_i represents the flux through reaction i, MW_i is the molecular weight of the enzyme catalyzing the reaction, kcat_i is the enzyme turnover number, σ_i is the enzyme saturation coefficient, ptot is the total protein fraction, and f is the mass fraction of enzymes in the proteome [25].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between traditional GEMs and the enhanced ecModel frameworks:

Diagram 1: Evolution from Traditional GEMs to ecModel Frameworks

Quantitative Performance Comparison: ecModels vs Traditional GEMs

Predictive Accuracy in Microbial Growth and Metabolic Phenotypes

Multiple studies have systematically evaluated the performance of ecModels against traditional GEMs across various organisms and growth conditions. The following table summarizes key quantitative comparisons:

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of ecModels Versus Traditional GEMs

| Organism | Model Versions | Performance Metric | Traditional GEM | ecModel | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae [26] | Yeast8 vs ecYeast8 | Critical dilution rate (D_crit) prediction | No Crabtree effect predicted | 0.27 hâ»Â¹ (Matches experimental 0.21-0.28 hâ»Â¹) | Chemostat cultures of strains CBS8066, DS28911, H1022 |

| E. coli [25] | iML1515 vs eciML1515 | Growth rate prediction on 24 carbon sources | Significant estimation errors | Reduced estimation error by 48% | Experimental growth rates on acetate, fructose, fumarate, etc. |

| M. thermophila [27] | iYW1475 vs ecMTM | Substrate hierarchy prediction | Inaccurate | Correctly captured order of five carbon sources | Plant biomass hydrolysis experiments |

| C. glutamicum [29] | Traditional vs ET-OptME | Prediction accuracy for 5 product targets | Baseline | 47-106% increase in accuracy | Comparison with experimental records |

Case Study: Dynamic Prediction of Overflow Metabolism

The superior predictive capability of ecModels is particularly evident in simulating overflow metabolism—the phenomenon where microorganisms partially ferment substrates to excreted byproducts even under aerobic conditions [25] [26]. In simulations of S. cerevisiae chemostat cultures, the traditional Yeast8 model failed to predict critical metabolic shifts, whereas ecYeast8 accurately captured:

- The Crabtree effect onset at critical dilution rates (D_crit = 0.27 hâ»Â¹), matching experimental values of 0.21-0.28 hâ»Â¹ for different strains [26]

- The sharp increase in glucose uptake and corresponding decrease in biomass yield after D_crit [26]

- The secretion of overflow metabolites (ethanol, acetaldehyde, acetate) at high growth rates [26]

- The reduction in oxygen uptake and increased COâ‚‚ production characteristic of respiratory-fermentative transitions [26]

Similarly, eciML1515 for E. coli demonstrated significantly improved prediction of overflow metabolism compared to the traditional iML1515, with the enzymatic constraints correctly revealing redox balance as the fundamental driver distinguishing E. coli and S. cerevisiae overflow metabolism patterns [25].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Workflows

Protocol for ecModel Construction Using GECKO 3.0

The GECKO (GCMS to Account for Enzyme Constraints, Using Kinetics and Omics) toolbox represents one of the most comprehensive protocols for ecModel construction [28]. The workflow consists of five methodical stages:

Model Expansion: Enhancement of the base GEM structure to include enzyme-related features

- Addition of enzyme usage reactions for each metabolic reaction

- Incorporation of enzyme pseudometabolites representing protein molecules

- Definition of the total protein pool constraint

kcat Integration: Incorporation of enzyme turnover numbers

Model Tuning: Parameter calibration to improve agreement with experimental data

- Adjustment of the total enzyme pool based on cellular protein measurements

- Calibration of enzyme saturation coefficients using chemostat cultivation data

- Iterative refinement to match observed growth phenotypes

Proteomics Integration: Incorporation of experimental omics data (optional)

- Constraining enzyme usage bounds based on measured protein abundances

- Identification of potential enzyme bottlenecks through flux-proteomics comparison

Simulation and Analysis: Running and interpreting ecModel simulations

- Implementation of enzyme-constrained flux balance analysis (ecFBA)

- Sampling of the enzyme-constrained solution space

- Prediction of metabolic engineering targets

The complete protocol requires approximately 5 hours for yeast models, though timing varies by organism complexity and data availability [28].

ECMpy Simplified Workflow

For researchers seeking a more streamlined approach, ECMpy provides a simplified alternative workflow [25]:

Irreversible Reaction Division: Split reversible reactions into forward and backward directions to accommodate direction-specific kcat values

Enzymatic Constraint Addition: Direct implementation of the enzyme mass constraint without modifying the stoichiometric matrix

kcat Calibration: Automated adjustment of original kcat values based on:

- Enzyme usage principle: Reactions with enzyme usage exceeding 1% of total enzyme content require parameter correction

- 13C flux consistency: Reactions where kcat × 10% of total enzyme amount is less than 13C-determined flux need correction

Model Storage: Save enzyme constraint information and metabolic network in JSON format (as SBML cannot accommodate enzyme constraints due to COBRApy limitations)

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comparative pathways for these two primary ecModel construction approaches:

Diagram 2: Comparative Workflows for ecModel Construction

Successful implementation of enzyme-constrained metabolic models requires both computational tools and experimental resources for validation. The following table details essential reagents and their functions in ecModel development and testing:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ecModel Development

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in ecModel Development | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | GECKO 3.0 [28], ECMpy [25], AutoPACMEN [27] | Core algorithms for constructing enzyme-constrained models | GECKO: Comprehensive protocol; ECMpy: Simplified workflow; AutoPACMEN: Automated data retrieval |

| Enzyme Kinetic Databases | BRENDA [27] [25], SABIO-RK [27] [25] | Source of experimental enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) | BRENDA: Extensive coverage; SABIO-RK: Kinetic parameters |

| Machine Learning kcat Predictors | TurNuP [27], DLKcat [27] | Prediction of kcat values for reactions lacking experimental data | TurNuP: Better performance in M. thermophila; DLKcat: Deep learning approach |

| Model Construction Tools | COBRApy [25] [3], GEMsembler [3] | Python packages for constraint-based modeling and model comparison | COBRApy: Standard FBA implementation; GEMsembler: Consensus model assembly |

| Experimental Validation Assays | RNA/DNA content measurement [27], Chemostat cultivation [26] | Parameter determination and model validation | RNA/DNA: Biomass composition; Chemostat: Steady-state growth data |

| Metabolic Network Databases | BiGG [27] [3], ModelSEED [3], MetaCyc [3] | Source of standardized metabolic reactions and metabolites | BiGG: High-quality curated database; ModelSEED: Automated reconstruction |

Emerging Advancements and Future Directions

Machine Learning-Enhanced Kinetic Parameter Prediction

A significant limitation in ecModel construction has been the scarcity of organism-specific enzyme kinetic parameters. Recent advancements address this bottleneck through machine learning approaches that predict kcat values from protein sequences and structures [27] [28]. In the construction of an ecModel for Myceliophthora thermophila, models incorporating TurNuP-predicted kcat values demonstrated superior performance compared to those using AutoPACMEN or DLKcat-derived parameters [27]. This integration of computational predictions enables ecModel development for poorly characterized organisms where experimental kinetic data is limited.

Multi-Constraint Integration: Enzyme and Thermodynamic Limitations

The most recent innovations in constraint-based modeling combine enzymatic limitations with other cellular constraints, particularly thermodynamics. The ET-OptME framework represents this advancement by simultaneously incorporating enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic feasibility constraints [29]. This dual-constraint approach has demonstrated remarkable improvements in predictive performance, showing at least a 70% increase in minimal precision and 47% increase in accuracy compared to enzyme-constrained models without thermodynamic considerations [29]. The framework successfully mitigates thermodynamic bottlenecks while optimizing enzyme usage, delivering more physiologically realistic intervention strategies for metabolic engineering.

Consensus Modeling and Cross-Platform Integration

As automated reconstruction tools proliferate, consensus approaches that integrate models from multiple sources have emerged as powerful strategies for enhancing predictive accuracy. GEMsembler enables the systematic combination of GEMs built with different tools, generating consensus models that outperform individual models and even manually curated gold-standard models in auxotrophy and gene essentiality predictions [3]. This approach increases network certainty by highlighting metabolic pathways with varying levels of confidence across reconstruction methods, ultimately providing more reliable models for systems biology applications.