Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Production Yields: Feedstocks, Technologies, and Sustainability Metrics

This article provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparative analysis of biofuel production yields for researchers and scientists.

Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Production Yields: Feedstocks, Technologies, and Sustainability Metrics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparative analysis of biofuel production yields for researchers and scientists. It explores foundational yield data across diverse feedstocks, examines advanced production and optimization methodologies including machine learning, and presents rigorous validation frameworks for comparing biofuel sustainability. Synthesizing current research and market trends, the analysis offers critical insights for strategic decision-making in renewable energy development, highlighting pathways to maximize yield efficiency and environmental benefits.

Benchmarking Biofuel Yields: A Foundation of Feedstocks and Projected Outputs

Global Biofuel Market Trajectory and Yield Implications

The global biofuel market is on a significant growth trajectory, propelled by the worldwide push for decarbonization and energy security. For researchers and scientists, understanding this trajectory is intrinsically linked to a central challenge: optimizing production yields to make bioenergy a scalable and economically viable alternative. This guide provides a comparative analysis of biofuel production yields, framing the discussion within the broader context of market evolution. It synthesizes current market data with experimental findings on yield optimization, detailing the methodologies and reagents that are foundational to advancing research in this critical field.

The global biofuel market is demonstrating robust growth, driven by stringent government policies and rising demand for clean energy. The following table summarizes the projected market size from different authoritative sources.

Table 1: Global Biofuel Market Size Projections

| Source | Base Year/Period | Market Size | Projected Year/Period | Projected Market Size | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precedence Research [1] | 2025 | USD 141 billion | 2034 | USD 257.61 billion | 6.90% |

| Technavio [2] | 2024 | - | 2029 | Increase of USD 32.6 billion | 3.8% |

Regional leadership and policies are key market drivers. As of 2024, North America dominates the global market, holding a 40.49% share [1]. This leadership is reinforced by policies like the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), which mandates significant biofuel blending [1]. Meanwhile, the Asia-Pacific region is expected to be the fastest-growing market between 2025 and 2034, fueled by ambitious national policies such as India's target for a 20% ethanol blend (E20) by 2025 and China's push for nationwide E10 adoption [1] [2].

Investment trends further underscore this positive outlook. Global investment in biofuels is projected to rise by 13% in 2025 to over $16 billion [3]. Regionally, the U.S. and Brazil are dominating investment in biodiesel and ethanol, with the U.S. also accounting for half of the global projected growth in Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) and Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) output [3].

Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Production Yields

Yield optimization is paramount for enhancing the economic and environmental sustainability of biofuels. The following studies provide a comparative analysis of yields across different feedstocks and production processes.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Yield and Performance

| Study Focus | Feedstock | Key Finding on Yield/Optimum Condition | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodiesel Yield Optimization [4] | Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) | Maximum yield of 95% achieved with 3% catalyst concentration, 80°C reaction temperature, and 6:1 methanol-to-oil ratio. | Resulting biodiesel showed 26% lower CO emissions and 13% lower smoke emissions compared to conventional diesel. |

| Harvesting Cost & Efficiency [5] [6] | Switchgrass | Stepwise Method: Most cost-effective for large, high-yield fields (\$37.70/ton).Integrated Method: Reduced GHG emissions by 9% and energy use by 5% in small, low-yield fields. | Informs feedstock supply chain logistics, demonstrating a trade-off between cost and emission reductions based on operational strategy. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Biodiesel from Waste Cooking Oil

This study utilized a machine learning approach to optimize the transesterification of Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) into biodiesel using a sustainable, eggshell-derived CaO catalyst [4].

- Feedstock Preparation: WCO was collected and filtered to remove food residues and other impurities. It was then heated to eliminate moisture. Due to high Free Fatty Acid (FFA) content, a pre-treatment acid-catalyzed esterification was performed using Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ and methanol to reduce FFA levels and prevent soap formation [4].

- Catalyst Synthesis: Eggshells were cleaned, dried, and crushed into a fine powder using a planetary ball mill. The powder was then calcined in a furnace at 600°C for 6 hours to convert calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) into active calcium oxide (CaO) [4].

- Transesterification Reaction: The pre-treated WCO was mixed with methanol and the synthesized CaO catalyst in a closed reactor system equipped with a reflux condenser to prevent methanol loss. The mixture was stirred continuously under controlled conditions [4].

- Machine Learning Optimization: 16 experimental runs were conducted. Four boosted machine learning algorithms (XGBoost, AdaBoost, GBM, and CatBoost) were employed to model the process. The models used hyperparameter tuning and k-fold cross-validation (k=5) to predict the optimal combination of catalyst concentration, reaction temperature, and methanol-to-oil molar ratio for maximizing yield [4].

- Product Separation & Validation: After the reaction, the mixture was allowed to settle, facilitating the separation of biodiesel from glycerol. The biodiesel phase was washed with warm water and dried. The fuel was then tested in a diesel engine to validate performance and emissions [4].

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized below:

Protocol 2: Analyzing Switchgrass Harvesting Methods

This study compared the economic and environmental impact of two harvesting methods for switchgrass, a key bioenergy feedstock [5] [6].

- Field Data Collection: A comprehensive dataset was collected over three years (2019-2021) from 125 commercial-scale switchgrass fields. Data included fuel consumption per hectare, operation type, machinery used, operational time, field size, and biomass yield [5].

- Harvesting Methods:

- Analysis:

- Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA): Quantified the harvesting costs per ton for each method under different field scenarios (varying field sizes and biomass yields).

- Lifecycle Assessment (LCA): Used the GREET model to quantify GHG emissions and energy consumption associated with each harvesting method [5].

- Regression Analysis: Identified key operational and climate factors (e.g., field size, biomass yield, temperature) influencing fuel consumption [5].

The logical relationship and outcomes of this analysis are as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing biofuel yield research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for experimental work in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofuel Yield Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., CaO) | Catalyze the transesterification reaction; reusable and environmentally friendly compared to homogeneous catalysts. | Synthesis of biodiesel from waste cooking oil; derived from sustainable sources like eggshells [4]. |

| Biofuel Enzymes (e.g., Cellulases, Amylases) | Break down complex biomass structures (cellulose, starch) into fermentable sugars for advanced bioethanol production. | Crucial for the commercialization of lignocellulosic ethanol and starch-based ethanol processes [7]. |

| Methanol | Acts as the alcohol reactant in the transesterification process for biodiesel production. | Standard reagent for converting triglycerides in oils into fatty acid methyl esters (biodiesel) [4]. |

| Non-Food Feedstocks (e.g., Switchgrass, Jatropha, Algae) | Second-generation feedstocks that avoid competition with food supply; offer high biomass yield potential. | Switchgrass is studied for its adaptability to marginal lands; Algae (3rd-gen) is researched for high fuel yield per acre [1] [2] [5]. |

| Acid Catalysts (e.g., Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Used in the pre-treatment esterification step to reduce Free Fatty Acid (FFA) content in low-grade feedstocks. | Pre-treatment of waste cooking oil to prevent soap formation during subsequent transesterification [4]. |

| Phenethyl acetate | Phenethyl Acetate CAS 103-45-7 - Research Chemical | High-purity Phenethyl acetate for research. Study its role as an insect odorant receptor agonist and its applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Dimethylamine-SPDB | Dimethylamine-SPDB, CAS:1193111-73-7, MF:C15H19N3O4S2, MW:369.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The global biofuel market is poised for substantial growth, creating an imperative for research that bridges market trends with scientific innovation. The comparative data and experimental protocols presented in this guide highlight a clear trajectory: the future of biofuel yield optimization lies in leveraging non-food feedstocks, developing sustainable and efficient catalysts, and employing data-driven methodologies like machine learning for process refinement. For researchers and industry professionals, success will depend on the continuous improvement of these core processes to enhance yield, reduce costs, and minimize environmental impact, thereby solidifying the role of biofuels in a sustainable energy landscape.

The transition to a sustainable bioeconomy hinges on the efficient utilization of biomass resources for biofuel production. Feedstocks for biofuels are broadly categorized into first-generation sources, such as corn and soybeans, which are derived from food crops, and second-generation sources, which utilize non-food biomass including agricultural residues like corn stover and wheat straw, as well as dedicated energy crops like switchgrass [8]. The choice of feedstock significantly influences the sustainability, economic viability, and technological pathway of biofuel production. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the yield potentials and production methodologies for prominent biofuel feedstocks, offering researchers a objective evaluation of their performance characteristics. The focus on yield is critical, as it directly impacts the land use efficiency and economic competitiveness of biofuels against conventional fossil fuels.

Recent advancements in conversion technologies and the integration of machine learning for process optimization are reshaping the potential of these feedstocks [4]. Furthermore, supportive public policies, such as the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) in the United States, are major drivers of demand for feedstock like corn and soybeans, highlighting the intertwined nature of agriculture and energy policy [9]. This analysis synthesizes experimental data and technological reviews to present a clear comparison of feedstock-specific yield potentials, from traditional corn to advanced cellulosic materials.

Feedstock Characteristics and Experimental Methodologies

The conversion of biomass into biofuels involves distinct technological pathways tailored to the specific chemical composition of the feedstock. The following section details the core characteristics and standard experimental protocols for evaluating the yield potential of various feedstocks.

First-Generation Feedstocks: Corn and Soybeans

Corn for Bioethanol: Corn is a primary feedstock for bioethanol production, particularly in the U.S., where policies like the RFS have driven significant demand [9]. The starch in corn kernels is readily broken down into sugars, which are then fermented into ethanol.

- Typical Experimental Protocol: The conventional process for corn ethanol involves dry milling. Corn kernels are ground, mixed with water to form a mash, and cooked. Enzymes (alpha-amylase and glucoamylase) are added to hydrolyze the starch into fermentable sugars (e.g., glucose). Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is then introduced to ferment the sugars into ethanol over 48-72 hours. The ethanol is subsequently purified through distillation and dehydration. Yield is calculated as the volume of anhydrous ethanol produced per dry ton of corn.

Soybeans for Biodiesel: Soybeans are a major source of biodiesel, primarily through the extraction and transesterification of their oil content.

- Typical Experimental Protocol: Soybeans are first crushed to separate the oil from the meal. The extracted soybean oil undergoes a transesterification reaction. A typical laboratory-scale procedure involves reacting the oil with an alcohol, usually methanol (at a 6:1 molar ratio), in the presence of a homogeneous alkaline catalyst like potassium hydroxide (KOH) at approximately 1% weight of the oil [4]. The reaction is conducted with constant stirring at 60-70°C for 1-2 hours. After the reaction, the mixture is allowed to settle, separating into biodiesel (upper layer) and glycerol (lower layer). The biodiesel is then washed and purified. Yield is measured as the volume or mass of purified biodiesel produced per unit mass of soybean oil.

Second-Generation Feedstocks: Cellulosic Materials

Second-generation feedstocks, such as agricultural residues and energy crops, are composed of lignocellulose—a complex matrix of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. This robust structure requires more intensive processing than first-generation feedstocks.

Corn Stover and Wheat Straw: These are abundant agricultural residues comprising the stalks, leaves, and husks left after harvest.

- Experimental Protocol - Pretreatment and Saccharification: A critical first step is pretreatment to disrupt the lignocellulosic structure. An advanced method, as demonstrated by Washington State University, uses a Ammonium Sulfite-based Alkali Pretreatment [10]. In this protocol, milled corn stover is treated with a solution of potassium hydroxide and ammonium sulfite at mild temperatures (e.g., 120°C) for a defined period. This process dissolves a significant portion of the lignin and hemicellulose, making the cellulose more accessible. After pretreatment and washing, enzymatic hydrolysis (saccharification) is performed using a cocktail of cellulase and hemicellulase enzymes to break down the cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars (e.g., glucose, xylose). The resulting sugar hydrolysate can then be fermented into ethanol or other biofuels.

Switchgrass for Bioenergy: A perennial grass, switchgrass is a promising dedicated energy crop due to its high biomass yield and adaptability to marginal lands [6].

- Experimental Protocol for Biomass Estimation: Yield potential for switchgrass is assessed through field trials. Biomass is harvested from predefined plot areas at the end of the growing season. The fresh weight is recorded, and a sub-sample is dried to determine moisture content, allowing for the calculation of dry biomass yield per hectare. This biomass can then be processed via various pathways, including biochemical conversion (similar to corn stover) for bioethanol or thermochemical conversion for bio-oil and biogas.

Waste Cooking Oil (WCO): As a waste-derived feedstock, WCO offers a sustainable alternative for biodiesel production.

- Experimental Protocol with Heterogeneous Catalysts: A novel approach involves using a reusable heterogeneous catalyst, such as CaO derived from eggshells [4]. The pre-treated WCO is reacted with methanol at an optimized molar ratio (e.g., 6:1) and a catalyst concentration of 3% by weight. The transesterification is carried out at 80°C with stirring. The CaO catalyst can be separated by filtration after the reaction, and the biodiesel is purified. Machine learning models, such as CatBoost, have been employed to optimize parameters like catalyst concentration, reaction temperature, and methanol-to-oil ratio to maximize yield [4].

The workflow below illustrates the general experimental pathways for converting different feedstocks into biofuels, highlighting the key steps involved.

Comparative Yield Data and Technical Performance

A critical comparison of feedstocks requires examining their quantitative yield potentials, conversion efficiencies, and the resulting biofuel quality. The following table consolidates key performance metrics from recent research.

Table 1: Comparative Yield Potentials and Characteristics of Biofuel Feedstocks

| Feedstock | Fuel Type | Key Conversion Technology | Reported Yield | Key Influencing Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Grain [9] | Bioethanol | Fermentation of Starch | ~400 L/tonne (est. from industry) | Starch content, fermentation efficiency |

| Soybeans [9] | Biodiesel | Transesterification (Homogeneous Catalyst) | ~180 L/tonne of beans (est. from industry) | Oil content (~18%), catalyst type |

| Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) [4] | Biodiesel | Transesterification (Heterogeneous CaO Catalyst) | 95% yield (by weight) | Methanol-to-Oil Ratio (6:1), Catalyst Concentration (3%), Temperature (80°C) |

| Corn Stover [10] | Fermentable Sugars | Ammonium Sulfite Pretreatment + Enzymatic Hydrolysis | Competitive sugar cost of $0.28/lb | Pretreatment severity, enzyme loading |

| Switchgrass [6] | Biomass Feedstock | Integrated Harvesting | ~Cost: $37.70/ton (for high-yield large fields) | Field size, biomass yield, harvesting method |

Performance and Emissions Analysis

Beyond sheer yield, the performance of the resulting biofuels in engines and their environmental impact are crucial metrics.

Biodiesel from WCO vs. Conventional Diesel: Engine performance tests of biodiesel produced from WCO using a CaO catalyst demonstrated significant environmental benefits. Compared to conventional diesel, this biodiesel showed a 26% reduction in Carbon Monoxide (CO) emissions and a 13% reduction in smoke emissions [4]. This confirms the potential of waste-derived biofuels to improve urban air quality. There is a trade-off in engine efficiency, with studies noting a marginal 2.83% decline in brake thermal efficiency and a 4.31% increase in fuel consumption due to the lower energy density of biodiesel [4].

Cellulosic vs. First-Generation Pathways: The primary advantage of cellulosic feedstocks like corn stover and switchgrass is their ability to utilize non-food biomass, thereby avoiding competition with food supply chains. Furthermore, their lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are typically lower than those of first-generation biofuels [6] [8]. However, a major technical challenge remains the presence of lignin and phenolic acids in these straws, which can inhibit subsequent fermentation and biogas production processes, necessitating effective pretreatment [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in biofuel production relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items used in the featured methodologies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofuel Production Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Oxide (CaO) Catalyst | Heterogeneous base catalyst for transesterification. | Derived from waste eggshells; used for biodiesel production from WCO due to its reusability and low environmental impact [4]. |

| Ammonium Sulfite & Potassium Hydroxide | Alkali salts for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. | Used in the pretreatment of corn stover to break down lignin and enhance enzymatic digestibility [10]. |

| Cellulase & Hemicellulase Enzymes | Enzyme cocktails for enzymatic hydrolysis (saccharification). | Break down cellulose and hemicellulose polymers in pretreated biomass into fermentable sugars [8] [10]. |

| Methanol | Alcohol reagent for transesterification. | Reacts with triglycerides in the presence of a catalyst to produce biodiesel (FAME) and glycerol [4]. |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Microbial yeast for ethanol fermentation. | Ferments hexose sugars (e.g., glucose) from corn starch or cellulosic hydrolysates into bioethanol. |

| Clocortolone | Clocortolone, CAS:4828-27-7, MF:C22H28ClFO4, MW:410.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Thiol-PEG12-acid | Thiol-PEG12-acid, CAS:1032347-93-5; 2211174-73-9, MF:C27H54O14S, MW:634.78 | Chemical Reagent |

This comparative analysis clearly illustrates the trade-offs between different biofuel feedstocks. First-generation feedstocks like corn and soybeans offer well-established, high-yield pathways but raise concerns regarding food-versus-fuel competition. Second-generation cellulosic feedstocks, such as corn stover and switchgrass, provide a sustainable alternative by utilizing waste resources and dedicated crops, though they require more complex and costly conversion technologies. Waste-derived feedstocks like WCO stand out for their high conversion efficiency and favorable emission profile when paired with novel catalysts.

Future yield improvements are likely to be driven by interdisciplinary approaches. Machine learning integration, as demonstrated in the optimization of WCO conversion, is a powerful tool for modeling complex reaction dynamics and maximizing output [4]. Continued innovation in pretreatment technologies, such as microwave-assisted pyrolysis and the use of ionic liquids, promises to enhance the economic viability of cellulosic biofuels by improving efficiency and reducing costs [8]. Finally, the development of advanced heterogeneous and nano-catalysts will be crucial for making biodiesel production more sustainable and cost-effective [4]. As policies continue to evolve and these technologies mature, the yield potential of both conventional and advanced feedstocks is expected to rise, solidifying the role of biofuels in the global energy landscape.

This comparison guide quantitatively assesses complex crop rotation systems as a sustainable strategy for enhancing biofuel production. Using a regional case study approach and synthesized experimental data, we compare the performance of multi-field crop rotations against monoculture systems and simpler rotations. The analysis focuses on biofuel yield potential, agricultural productivity, and environmental synergies, providing researchers with validated protocols and datasets to inform bioenergy cropping system design.

The transition to a sustainable bioeconomy requires cropping systems that simultaneously address energy production, food security, and environmental stewardship. Complex crop rotations—defined as sequenced cultivation of multiple crop species across time—represent a promising ecological intensification strategy. This guide provides a comparative analysis of complex rotation performance based on field experimental data, quantifying their potential to enhance biofuel feedstock production while maintaining agricultural productivity and soil health.

Methodology for Data Collection and Analysis

Literature Screening and Selection Criteria

This analysis synthesized data from peer-reviewed field studies, meta-analyses, and regional case studies published between 2016-2025. Primary selection criteria included: (1) field-scale replication of crop rotations; (2) quantitative yield measurements of biofuel feedstocks or convertible biomass; (3) documentation of management practices; and (4) inclusion of comparator systems (typically monocultures). Studies without controlled comparisons or sufficient methodological detail were excluded.

Quantitative Synthesis Approach

For each qualifying study, we extracted quantitative data on: (1) biomass yields; (2) biofuel potential yields (ethanol, biodiesel, biogas); (3) soil quality indicators; (4) nutrient use efficiency; and (5) economic returns. Data were normalized to common units (Mg haâ»Â¹ for biomass yields, L haâ»Â¹ or GJ haâ»Â¹ for bioenergy) where possible. When studies reported multi-year data, we calculated mean values across experimental durations.

Regional Case Study: Ukraine's 10-Field Crop Rotation System

System Configuration and Experimental Design

A comprehensive assessment of a 10-field crop rotation system in Ukraine (2020-2024) demonstrates the scalability of complex rotations for integrated biofuel and food production [11]. The system integrated food crops (wheat, barley, sunflower, soybeans) with dedicated energy crops (sugar beet, corn, rapeseed) in a carefully sequenced rotation. Key design elements included:

- Field Arrangement: Ten distinct fields, each following the same crop sequence but phased temporally

- Crop Sequencing: Strategic alternation of deep-rooted and shallow-rooted species, nitrogen-fixing and nitrogen-demanding crops

- Organic Amendment Integration: Systematic application of digestate from biogas production as organic fertilizer

- Experimental Duration: Five-year monitoring period (2020-2024) with continuous data collection

Table 1: Biofuel Production Potential from Ukraine's 10-Field Crop Rotation System

| Biofuel Type | Annual Production Potential | Energy Equivalent | Primary Feedstock Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioethanol | 11.1 million tons | ~244 PJ | Sugar beet, corn |

| Biodiesel | 3.16 million tons | ~118 PJ | Rapeseed, sunflower |

| Biogas | 6.18 billion m³ | ~148 PJ | Agricultural residues, cover crops |

| Solid Biofuel | 3.87 million tons | ~58 PJ | Crop residues, biomass crops |

Comparative Yield Performance

The Ukrainian case study demonstrated significant yield advantages for the complex rotation system compared to regional monoculture benchmarks [11]. Overall crop yields increased by 10-20% despite reduced cultivated area, attributable to more efficient nutrient cycling and reduced pest pressure. Specific yield enhancements included:

- Digestate Integration: Crop yields increased by 53-83% with digestate application compared to unfertilized controls

- Soil Health Improvement: Systematic organic amendment led to normalized soil acidity and improved soil organic carbon

- Land Use Efficiency: The system achieved higher total productivity per unit area through complementary crop phenologies and resource needs

Global Meta-Analysis of Rotation Benefits

Productivity and Nutritional Advantages

A recent global meta-analysis synthesizing 3,663 paired field observations provides robust statistical evidence for rotation benefits across diverse agroecosystems [12]. The analysis revealed:

- Yield Enhancement: Crop rotations increased subsequent crop yields by 20% on average compared to monocultures

- Legume Advantage: Legume pre-crops outperformed non-legume pre-crops, yielding 23% versus 16% average increases

- System-Level Benefits: Considering complete rotation sequences (pre-crop plus main crop), rotations increased total yields by 23%, dietary energy by 24%, and protein by 14% compared to continuous monoculture

- Temporal Stability: Rotation systems demonstrated 0.21 lower yield variability (lnCV) than monocultures, indicating enhanced climate resilience

Table 2: Rotation System Performance Across Continents

| Continent | Average Yield Gain | Legume Pre-crop Advantage | Key High-Performing Crop Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oceania | 27% | Not significant | Wheat following faba bean |

| Asia | 25% | Moderate | Maize-legume rotations |

| Europe | 24% | Moderate | Wheat-red clover rotations |

| Africa | 22% | Strong (29% vs 16%) | Millet-legume systems |

| South America | 19% | Not significant | Soybean-maize rotations |

| North America | 18% | Strong (22% vs 14%) | Maize-soybean-wheat |

Biofuel-Specific Crop Combinations

Research has identified particularly effective crop combinations for integrated biofuel production systems [13] [14]:

- Biomass Sorghum Intercropping: Biomass sorghum intercropped with sunn hemp (legume) achieved yields of 23 Mg haâ»Â¹ (fertilized) and 19 Mg haâ»Â¹ (unfertilized)

- Complementary Rooting Systems: Strategic pairing of deep-rooted (sorghum, pearl millet) and shallow-rooted legumes (sunn hemp) enhanced resource capture

- Nitrogen Fixation Benefits: Legume integration reduced synthetic nitrogen requirements by 41-46% while maintaining high biomass yields

- Feedstock Quality Enhancement: Intercropping improved biomass composition for biofuel conversion, increasing cellulose content (+17%) and reducing detrimental alkali elements

Experimental Protocols for Rotation System Assessment

Field Trial Establishment

Standardized protocols for establishing rotation experiments ensure comparable, replicable data [13] [11] [14]:

- Site Characterization: Comprehensive pre-experiment soil analysis (pH, organic matter, N, P, K), climate baseline establishment, and topographic mapping

- Experimental Design: Randomized complete block designs with sufficient replication (typically 3-4 blocks) to account for field heterogeneity

- Treatment Structure: Inclusion of both rotation systems and appropriate monoculture controls within the same experiment

- Management Standardization: Consistent management practices (tillage, planting dates, pest control) across treatments except for the rotation variable itself

Data Collection and Measurement

Essential measurements for comprehensive rotation assessment include [13] [12]:

- Biomass Yield Quantification: Aboveground biomass harvesting at physiological maturity from standardized plot areas

- Soil Nutrient Dynamics: Seasonal monitoring of soil N, P, K, and organic matter at multiple depth increments

- Nitrogen Fixation Estimation: Isotopic methods or N difference approaches to quantify biological N fixation in legume-containing rotations

- Biofuel Conversion Efficiency: Laboratory assessment of biomass composition (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) and conversion potential to various biofuels

Statistical Analysis Framework

Robust statistical approaches for rotation studies include [12]:

- Mixed Effects Models: Accounting for both fixed (treatment, year) and random (block, site) effects

- Land Equivalent Ratio (LER): Quantifying land use efficiency in intercropping systems where LER = (Yab/Yaa) + (Yba/Ybb)

- Economic Analysis: Calculation of net returns, accounting for both production costs and market values of all rotation components

- Multivariate Analysis: Principal component analysis to identify relationships among multiple response variables

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Crop Rotation Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Field Equipment | Soil corers, GPS units, quadrant frames, portable spectrometers | Precise spatial sampling, georeferencing, non-destructive plant measurement |

| Soil Analysis | Soil sampling probes, soil test kits, ion exchange membranes, isotopic tracers (¹âµN) | Nutrient availability assessment, nitrogen fixation quantification |

| Plant Biomass Assessment | Plant presses, drying ovens, ball mills, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) | Biomass quantification, compositional analysis for conversion potential |

| Biofuel Conversion Assessment | Laboratory-scale reactors, HPLC systems, calorimeters, gas chromatographs | Biofuel yield potential, biomass quality characterization |

| Data Collection & Management | Field sensors (soil moisture, temperature), weather stations, electronic data loggers | Microclimate monitoring, continuous environmental data collection |

| Galanganone B | Galanganone B, MF:C34H40O6, MW:544.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anticancer agent 189 | Anticancer agent 189, MF:C42H56N4O10, MW:776.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Complex crop rotation systems demonstrate significant advantages over monoculture for integrated biofuel and food production. The Ukrainian case study exemplifies the scalability of these systems, with potential to produce substantial biofuel volumes while enhancing food crop yields. Global meta-analysis confirms consistent benefits across diverse agroecologies, with yield increases of 16-27% depending on system design and regional context. Effective rotation systems leverage ecological principles—particularly legume integration and strategic sequencing—to enhance productivity, improve system resilience, and reduce synthetic input requirements. Future research should prioritize optimization of crop combinations for specific regional contexts and development of integrated assessment frameworks that capture both productivity and sustainability metrics.

Establishing Baseline Yields for Ethanol, Biodiesel, and Biogas

The global transition toward sustainable energy systems has intensified the need for renewable alternatives to fossil fuels. Biofuels, including ethanol, biodiesel, and biogas, represent promising substitutes that can mitigate environmental pollution and enhance energy security. Establishing baseline production yields is critical for researchers and industry professionals to evaluate process efficiency, conduct techno-economic analyses, and guide policy development. This guide provides a comparative analysis of production yields and methodologies for these three prominent biofuels, synthesizing current research data to offer a standardized reference for comparison and optimization.

Comparative Yield Data for Biofuels

The baseline yield for a biofuel is a primary indicator of process efficiency and economic viability. It varies significantly based on feedstock type, production methodology, and process optimization. The table below summarizes characteristic yield ranges from recent research for each biofuel category.

Table 1: Characteristic Baseline Yields for Ethanol, Biodiesel, and Biogas

| Biofuel Type | Feedstock | Key Process Parameters | Reported Yield | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biodiesel | Melia azadirachta (Neem) Seed Oil | Transesterification with KOH catalyst | ~86% (by weight of oil) | [15] |

| Biodiesel | Manilkara zapota Seed Oil | Transesterification (6:1 methanol:oil, 1% KOH, 90 min, 50°C) | 94.83% | [16] |

| Biogas | Pretreated Ulva Intestinalis Linnaeus (Macroalgae) | Ultrasonication Pretreatment (15 power/time, 40 min) | 181.0 mL·gVSâ»Â¹ | [17] |

| Biogas | Pretreated Ulva Intestinalis Linnaeus (Macroalgae) | Ozonation Pretreatment (15.0 mg/min, 40.0 min) | 164.0 mL·gVSâ»Â¹ | [17] |

| Ethanol | Market Fuel Blending (from corn) | Splash blending with gasoline (Low to Mid-level blends) | (Reported as emissions reduction, not volumetric production yield) | [18] |

Yield Analysis: The data indicates that biodiesel production via transesterification consistently achieves high yields, often exceeding 85-90% from optimized oilseed feedstocks. Biogas yield is highly dependent on the substrate and pretreatment method, with advanced pretreatment techniques like ultrasonication significantly enhancing biogas volume per gram of volatile solids. A definitive baseline production yield for ethanol was not available in the search results, which instead focused on its emission characteristics when blended with gasoline.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Understanding the experimental methodology is crucial for interpreting yield data and reproducing results. This section details the standard protocols for producing biodiesel and biogas, as evidenced in the cited research.

Biodiesel Production via Transesterification

The production of biodiesel from neem seed oil, as detailed by [15], follows a two-stage protocol: oil extraction followed by transesterification.

1. Oil Extraction from Seeds:

- Feedstock Preparation: Fresh neem seeds (Melia azadirachta) are washed with clean water and dried in a microwave oven at 105°C for 24 hours. The dried seeds are pulverized into a powder and sieved to ensure particles are less than 5 mm.

- Solvent Extraction: Approximately 50 g of the powdered seed is enclosed in filter paper and placed in a Soxhlet apparatus. The solvent, n-hexane, is heated to 70°C in a round-bottom flask, and the extraction process continues for about two hours. The oil is separated from the solvent by heating the extract to 70°C in an oven. The oil yield is calculated using the formula provided in Eq. (1) [15].

2. Transesterification Reaction:

- Reaction Setup: The extracted neem oil is reacted with methanol in the presence of a potassium hydroxide (KOH) catalyst. This process, known as transesterification, converts the triglycerides in the oil into fatty acid methyl esters (biodiesel).

- Optimization & Characterization: The reaction conditions, including catalyst concentration, temperature, reaction time, and stirring speed, are optimized to achieve the maximum yield (~86%). The resulting biodiesel is then characterized using advanced instruments like Gas Chromatography (GC) and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm its chemical properties and quality [15].

Biogas Production via Anaerobic Digestion

The protocol for optimizing biogas yield from macroalgae, as per [17], involves a critical pretreatment step before anaerobic digestion.

1. Substrate Pretreatment:

- Objective: The complex cell wall structure of algal biomass is a rate-limiting step. Pretreatment disrupts this structure, enhancing the material's biodegradability.

- Methods: Several pretreatment methods can be applied:

- Ultrasonication (US): Uses ultrasonic waves to disrupt cell walls.

- Ozonation (O3): Employs ozone to break down lignin and other complex polymers.

- Microwave (MW): Uses microwave radiation to rapidly heat and disrupt the biomass.

- Nanoparticle Additives: Utilizes additives like Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles to improve the digestion process.

2. Anaerobic Digestion (AD) Process:

- Process Stages: The pretreated substrate is subjected to AD, a biological process occurring in four stages: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis. This process is facilitated by a consortium of bacteria in an oxygen-free environment.

- Biogas Collection: The final product is biogas, primarily composed of 55-75% methane (CHâ‚„), with the remainder being carbon dioxide and trace gases. The yield is measured in milliliters of biogas produced per gram of volatile solids (VS) added (mL·gVSâ»Â¹) [17].

Research Workflow and Pathway Visualization

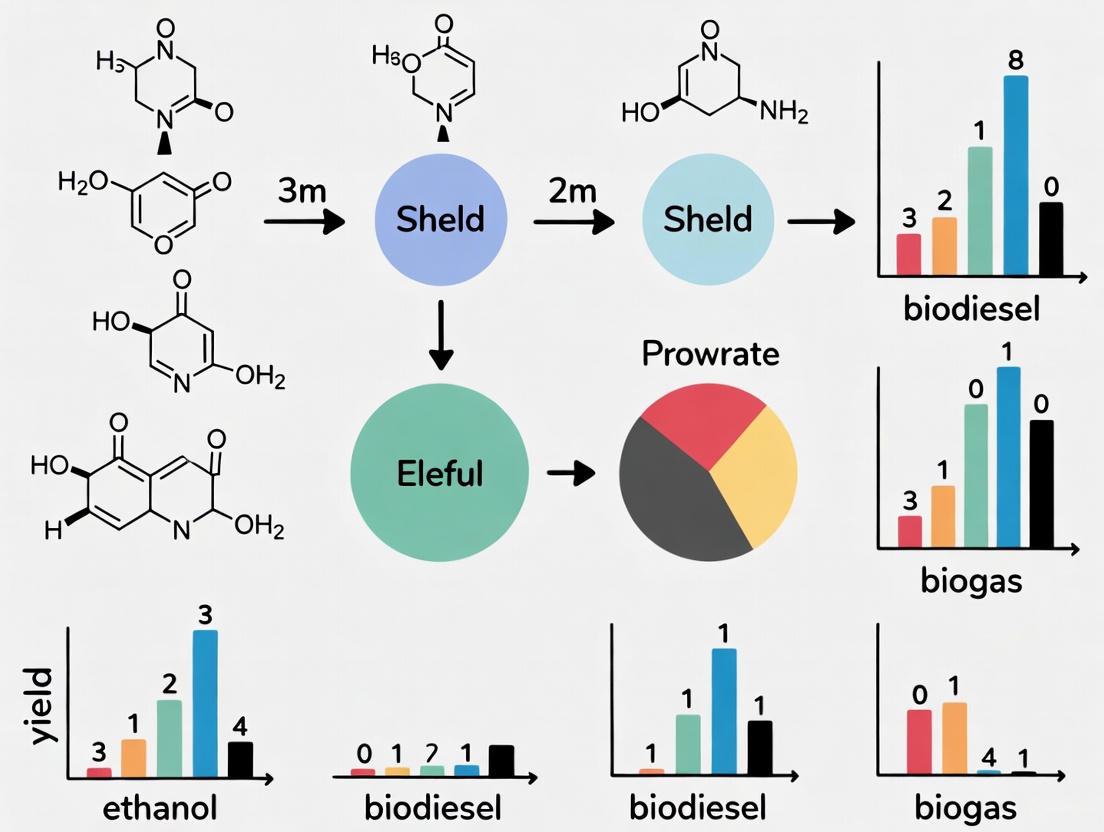

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing and optimizing biofuel production yields, integrating both experimental and modeling approaches as described in the research.

Diagram 1: Biofuel yield establishment workflow. The workflow involves feedstock preparation, processing, and conversion, with data from initial cycles feeding into optimization models (RSM, ANN, ANFIS) to refine parameters and establish a final baseline yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful biofuel production and analysis rely on specific chemical reagents and materials. The following table details essential items used in the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofuel Production

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biofuel Production | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol (CH₃OH) | Reactant in transesterification; provides the methyl group for biodiesel (FAME) formation. | Used in biodiesel production from neem and M. zapota seed oils [15] [16]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Homogeneous base catalyst to accelerate the transesterification reaction. | Catalyst for biodiesel production [15] [16]. |

| n-Hexane | Organic solvent for extracting oil from solid seed material. | Used in Soxhlet apparatus for neem oil extraction [15]. |

| Inoculum (Anaerobic Sludge) | Source of microbial consortium required for the anaerobic digestion process. | Essential for initiating biogas production in digesters [17]. |

| Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles | Additive to improve the efficiency and yield of the anaerobic digestion process. | Used as a pretreatment method for macroalgae to enhance biogas yield [17]. |

| Phenolphthalein Indicator | Acid-base indicator used for titrations to determine the acid value of oils. | Used in acid value measurement of extracted neem oil [15]. |

| 8-pCPT-cGMP-AM | 8-pCPT-cGMP-AM, MF:C19H19ClN5O9PS, MW:559.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TCO-PEG12-TFP ester | TCO-PEG12-TFP ester, MF:C42H67F4NO16, MW:918.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This guide establishes baseline production yields for biodiesel and biogas based on recent, optimized research. Biodiesel production from non-edible oilseeds like Melia azadirachta and Manilkara zapota demonstrates high conversion efficiencies, with yields reaching 86-95%. Biogas production from pretreated macroalgae shows more variable yields, highly dependent on the pretreatment method, with ultrasonication yielding up to 181 mL·gVSâ»Â¹. The available data for ethanol in the provided research pertained to its emission profile rather than its production yield, highlighting a potential area for further data collection. The integration of advanced modeling techniques like RSM and ANFIS is proving to be a powerful tool for refining these baseline yields further, offering researchers a data-driven path to optimize biofuel production processes for greater efficiency and sustainability.

Advanced Production Methodologies and Yield Enhancement Techniques

Machine Learning for Process Parameter Optimization

The optimization of process parameters in biodiesel production represents a significant challenge due to the complex, non-linear relationships between reaction variables and final yield. Traditional experimental methods are often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and inefficient at capturing these complex interactions. Recently, machine learning (ML) technologies have emerged as powerful tools for modeling, predicting, and optimizing biodiesel production processes, enabling researchers to achieve higher yields with greater efficiency and reduced experimental workload. This review provides a comparative analysis of various ML approaches applied to biodiesel production parameter optimization, examining their predictive performance, implementation requirements, and suitability for different research scenarios within the broader context of advancing biofuel production yields research.

ML algorithms excel at identifying complex patterns in multivariate experimental data that might elude traditional statistical methods. In biodiesel production, key process parameters such as alcohol-to-oil molar ratio, catalyst concentration, reaction temperature, and reaction time significantly influence the transesterification efficiency and final biodiesel yield [19]. By learning from experimental data, ML models can predict optimal parameter combinations, significantly reducing the number of experiments required while maximizing biodiesel production efficiency.

Key Machine Learning Technologies and Performance Comparison

Several machine learning approaches have been successfully applied to optimize biodiesel production parameters, each with distinct strengths and implementation characteristics. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are particularly effective at modeling complex non-linear relationships between process parameters and biodiesel yield [20] [19]. Ensemble methods such as gradient boosting algorithms have demonstrated exceptional predictive accuracy by combining multiple weak learners to create stronger predictive models [4] [21]. Hybrid approaches that integrate multiple ML techniques or combine ML with traditional optimization methods have also shown promising results for specific biodiesel production scenarios [22].

The selection of an appropriate ML technology depends on multiple factors including dataset size, feature complexity, computational resources, and the specific optimization objectives. Tree-based algorithms generally offer better interpretability through feature importance metrics, while neural networks excel at capturing complex interactions in high-dimensional data. For research applications where understanding parameter influence is crucial, models providing interpretability insights alongside predictive capability are particularly valuable.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Biodiesel Yield Prediction

| ML Algorithm | Best Reported R² | Best Reported RMSE | Optimal Yield | Key Advantages | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost [4] | 0.955 | 0.83 | 95% | Handles categorical features well, robust to overfitting | Waste cooking oil with heterogeneous catalysts |

| Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) [21] | 0.744 | 10.78 | N/A | High performance on large, diverse datasets | Multi-study analysis (3038 samples across 111 studies) |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [19] | 0.98-0.99 (range) | N/A | 84-98% | Excellent for complex nonlinear relationships | Various feedstocks and production methods |

| XGBoost [4] | N/A | N/A | N/A | High computational efficiency, scalability | Large-scale optimization problems |

| Random Forest [21] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Good interpretability, robust to outliers | Initial exploratory analysis with complex parameter interactions |

Table 2: Influence of Process Parameters on Biodiesel Yield Across ML Studies

| Process Parameter | Range in Experimental Studies | Reported Influence on Yield | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol-to-Oil Molar Ratio [4] | 3:1 to 12:1 | Highest impact factor in multiple studies | 6:1 to 9:1 |

| Catalyst Concentration [4] | 0.5% to 3% wt | Second most influential parameter | 1% to 3% |

| Reaction Temperature [4] | 50°C to 80°C | Moderate to high influence | 60°C to 80°C |

| Reaction Time [19] | 30 min to 120 min | Varies significantly by catalyst type | 60-90 min |

| Feedstock Type [20] [19] | Various edible and non-edible oils | Significant impact on optimal parameter sets | Depends on FFA content |

The performance comparison reveals that while advanced ensemble methods like CatBoost achieve exceptional predictive accuracy for specific experimental setups, ANN models consistently demonstrate high reliability across diverse production scenarios. The Gradient Boosting Regressor applied to a large dataset of 3038 samples from 111 studies achieved respectable performance (R² = 0.744), demonstrating the capability of ML models to generalize across different reaction systems and experimental conditions [21]. This cross-study validation is particularly valuable for establishing robust optimization frameworks applicable to novel biodiesel production scenarios.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative Experimental Workflow

A comprehensive understanding of experimental protocols is essential for proper interpretation of ML optimization results in biodiesel research. The following diagram illustrates a typical integrated experimental and ML workflow for biodiesel process optimization:

Diagram 1: Integrated ML and Experimental Workflow for Biodiesel Optimization. This workflow illustrates the systematic approach combining laboratory experimentation with machine learning optimization, including critical feedback loops for continuous improvement.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Based on the analysis of multiple studies, a representative experimental protocol for ML-based biodiesel optimization includes the following key stages:

Feedstock Preparation and Characterization: Waste cooking oil (WCO) is collected and subjected to filtration to remove food residues and other particulate matter. The filtered oil is then heated to approximately 110°C to remove moisture content, which can interfere with the transesterification reaction. Free Fatty Acid (FFA) content is determined through titration, and if FFA exceeds 2%, a two-step process (esterification followed by transesterification) is implemented [4].

Catalyst Synthesis: For heterogeneous catalyst systems, calcium oxide (CaO) derived from waste eggshells has demonstrated excellent performance. The synthesis protocol involves thoroughly cleaning eggshells with distilled water, drying at 60°C for 12 hours, grinding to fine powder using planetary ball milling, and calcining at 600°C for 6 hours to convert calcium carbonate to active CaO [4]. This sustainable catalyst approach aligns with the principles of circular economy in biodiesel production.

Transesterification Reaction Optimization: The core experimental phase involves conducting multiple transesterification runs while systematically varying key parameters: catalyst concentration (0.5-3 wt%), methanol-to-oil molar ratio (3:1-12:1), reaction temperature (50-80°C), and reaction time (60-120 minutes). The reactions are typically performed in batch reactors equipped with reflux condensers to prevent methanol loss [4]. Each experimental run generates data points that populate the training dataset for ML models.

Product Separation and Purification: After the transesterification reaction is complete, the mixture is transferred to a separation funnel and allowed to settle for 4-12 hours. Gravity separation partitions the mixture into upper layer (biodiesel) and lower layer (glycerol). The biodiesel layer is then washed with warm water to remove residual catalyst and impurities, followed by drying to remove moisture [4].

Machine Learning Implementation Framework

Model Development and Training Protocol

The implementation of machine learning for parameter optimization follows a systematic protocol to ensure robust and reliable predictions:

Dataset Construction: Experimental data is organized into a structured dataset where each row represents an experimental run and columns represent input parameters (catalyst concentration, reaction temperature, methanol-to-oil ratio, reaction time) and the output variable (biodiesel yield). The dataset size varies across studies, with comprehensive analyses incorporating thousands of data points from multiple studies [21].

Algorithm Selection and Training: Multiple ML algorithms are typically implemented to identify the best performer for the specific experimental system. The CatBoost algorithm has demonstrated exceptional performance in biodiesel yield prediction, achieving R² values of 0.955 with RMSE of 0.83 in comparative studies [4]. Other algorithms including XGBoost, Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and AdaBoost are also employed with performance comparisons conducted through rigorous validation protocols.

Hyperparameter Tuning and Validation: Optimal model performance requires careful tuning of algorithm-specific parameters through techniques such as grid search coupled with k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5) [4]. This process helps prevent overfitting and ensures model generalizability. Residual plots and learning curves are analyzed to verify model stability and prediction reliability across the parameter space.

Model Interpretation and Optimization

Feature Importance Analysis: ML models provide insights into the relative importance of each process parameter, enabling researchers to focus optimization efforts on the most influential factors. In multiple studies, methanol-to-oil ratio and catalyst concentration consistently emerge as the most significant parameters affecting biodiesel yield [4].

Partial Dependence Plots: These visualization tools illustrate the relationship between specific input parameters and biodiesel yield while marginalizing the effects of other parameters, providing valuable insights for process optimization [4].

Optimization and Validation: The trained ML models are employed to predict optimal parameter combinations maximizing biodiesel yield. These predictions are subsequently validated through confirmatory experiments, completing the iterative optimization cycle. Studies report yield improvements to 84-98% through this ML-guided approach compared to traditional unoptimized methods [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for Biodiesel Optimization

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biodiesel Production Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Experiment | Notes on Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Oils | Waste cooking oil, soybean oil, microalgae oil, non-edible oils | Primary reactant providing triglycerides | Selection impacts FFA content, requiring pretreatment |

| Alcohol Reagents | Methanol (≥99% purity) | Reactant in transesterification | High purity reduces side reactions; methanol preferred for reactivity and cost |

| Homogeneous Catalysts | KOH, NaOH (≥85% purity) | Accelerate transesterification reaction | High activity but difficult separation and generate waste |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | CaO from eggshells, mixed metal oxides | Reusable catalysts for sustainable production | Enable easier separation, reusability (4-5 cycles) |

| Acid Catalysts | Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ (concentrated, 95-98%) | Esterification pretreatment for high-FFA feedstocks | Reduces FFA to prevent soap formation |

| Analytical Standards | Methyl ester standards (C8-C24) | GC calibration for yield quantification | Essential for accurate yield measurement |

| Separation Materials | Distilled water, centrifugation equipment | Purification and separation of biodiesel | Critical for achieving fuel purity standards |

The selection of appropriate reagents and materials significantly influences both biodiesel yield and quality parameters. Heterogeneous catalysts derived from waste materials, particularly CaO from eggshells, have gained prominence due to their sustainability, reusability, and reduced environmental impact compared to traditional homogeneous catalysts [4]. The trend toward utilizing waste feedstocks such as waste cooking oil aligns with the principles of circular economy while addressing concerns about food-versus-fuel competitions associated with first-generation biodiesel feedstocks [20].

Comparative Analysis of ML Optimization Pathways

The relationship between different ML approaches and their optimization pathways can be visualized through the following diagram:

Diagram 2: Machine Learning Optimization Pathways Comparison. This diagram illustrates the three primary ML approaches applied to biodiesel optimization, their respective strengths, and limitations to guide algorithm selection.

Machine learning technologies have revolutionized the optimization of process parameters in biodiesel production, enabling unprecedented precision in predicting optimal reaction conditions. Through comparative analysis, ensemble methods like CatBoost and Gradient Boosting Regressors demonstrate exceptional predictive accuracy, while ANN models provide robust performance across diverse feedstocks and production conditions. The integration of ML approaches with traditional experimental methods creates a powerful framework for accelerating biodiesel research, reducing experimental workload, and maximizing production yields. As these technologies continue to evolve, their implementation is poised to play an increasingly vital role in advancing sustainable biofuel production and supporting the global transition to renewable energy sources. Future research directions should focus on developing more interpretable ML models, expanding applications to emerging feedstocks, and creating standardized benchmarking frameworks for objective performance comparison across studies.

The transition to a sustainable energy future is heavily reliant on advancing biomass conversion technologies. Among the most prominent are fermentation, hydrolysis, and gasification—each offering distinct pathways to transform organic matter into usable fuels. These processes vary significantly in their operational mechanisms, efficiency metrics, and suitability for different feedstock types. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these technologies, focusing on their conversion efficiency, which is paramount for commercial viability and environmental sustainability. The evaluation is contextualized within the broader biofuel yield research landscape, examining both mature and emerging approaches that are shaping the future of renewable energy. Recent advances, particularly in enzyme engineering and process integration, are pushing the boundaries of what is technically achievable, while artificial intelligence is emerging as a transformative tool for optimizing complex biochemical and thermochemical processes [23].

The following sections provide detailed comparisons of these technologies, supported by experimental data and methodological details to assist researchers in selecting and optimizing appropriate pathways for specific feedstocks and target products.

Technology Comparison Tables

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Core Biofuel Conversion Technologies

| Parameter | Fermentation | Hydrolysis | Gasification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Type | Biochemical | Biochemical | Thermochemical |

| Common Feedstocks | Corn, sugarcane, sugar crops [2] [24] | Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., agricultural residues, non-food crops) [2] [7] | Diverse, including wet/dry biomass, waste oils, all organic components (including lignin) [25] [26] |

| Key Intermediate Product | Sugars | Sugars | Syngas (CO, Hâ‚‚, COâ‚‚) [26] |

| Final Fuel Products | Bioethanol, Butanol [26] | Cellulosic Ethanol, Biogas | Syngas, Bio-oil, Renewable Diesel, Biojet Fuel [2] [25] |

| Representative Energy Efficiency | Varies by process and microbe | Varies with pretreatment and enzyme efficiency | ~20% to >80% (depending on system and integration) [25] |

| Technology Readiness Level | Commercial (1st Gen) / Demonstration (2nd Gen) | Pilot to Commercial Scale [7] | Pilot to Commercial Scale |

| Key Advantage | Established commercial process for sugars/starch | Utilizes non-food biomass, reduces "food vs. fuel" concern | Highest feedstock flexibility, utilizes all organic components including lignin [26] |

| Primary Challenge | Feedstock limitation & competition with food supply | High enzyme cost, requires efficient pretreatment | Tar formation, management of trace gaseous species, high capital cost [26] |

Table 2: Advanced and Integrated Process Performance Data

| Process / Technology | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value / Range | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gasification-Fermentation | Carbon Conversion Efficiency | Higher than hydrolysis-fermentation | By utilizing lignin, it converts a greater portion of biomass carbon to fuel [26] |

| Supercritical Water Gasification (SCWG) | Energy Efficiency | ~20% to >80% [25] | Strongly influenced by operating conditions and system integration (e.g., with fuel cells) [25] |

| Anaerobic Co-digestion | Methane Yield Increase | Up to ~28% [23] | Achieved with mechanical pretreatment (bead milling) to decrease particle size [23] |

| AI-Optimized Biomass Conversion | Model Types Used | ANN, SVM, Decision Trees, Hybrid Models [23] | Used to optimize parameters for anaerobic digestion, gasification, pyrolysis, etc. [23] |

| Syngas Fermentation | Substrate Requirement Flexibility | High (no strict CO:Hâ‚‚:COâ‚‚ ratio required) [26] | Avoids the need for energy-intensive syngas reforming [26] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Integrated Gasification-Fermentation

This protocol describes the thermochemical-biological platform for producing alcohols from biomass-derived syngas, a promising integrated approach [26].

Biomass Preparation and Gasification:

- Feedstock Preparation: Reduce biomass (e.g., switchgrass, wood residues, agricultural wastes) to a uniform particle size suitable for the gasifier (typically 1-5 mm) to ensure consistent feeding and conversion [26].

- Syngas Production: Feed the biomass into a fluidized bed gasifier operating at high temperatures (typically >800°C) in an oxygen-limited environment. Use gasifying agents such as air, steam, or oxygen. The primary product is syngas, a mixture of CO, CO₂, H₂, and N₂, along with trace contaminants like tars and hydrogen sulfide [26].

- Syngas Cleaning and Cooling: Critically, the raw syngas must be cleaned and cooled before fermentation. This involves passing it through a series of units: a cyclone for particulate removal, a tar reformer or scrubber, and a condenser to bring the gas to a temperature suitable for the microorganisms (typically ~37°C) [26].

Syngas Fermentation:

- Inoculum and Medium Preparation: Use a suitable acetogenic strain, such as Clostridium species (e.g., C. carboxidivorans) or Alkalibaculum bacchi. Prepare a sterile, anaerobic medium in a bioreactor. Corn steep liquor can be used as a low-cost nutrient replacement for yeast extract [26].

- Bioreactor Operation: Sparge the cleaned, cooled syngas into the bioreactor containing the microbial culture. Maintain strict anaerobic conditions. Key operational parameters to monitor and control include:

- pH: Maintain at a level optimal for the chosen microbe (e.g., near neutral for many strains).

- Temperature: Typically 35-37°C for mesophilic cultures.

- Agitation Rate: Ensure sufficient mass transfer of syngas from the headspace into the liquid medium [26].

- Product Recovery: The fermentation process converts the syngas components into products like ethanol, n-butanol, and n-propanol. These can be recovered from the fermentation broth using techniques such as distillation or pervaporation [26].

Protocol for AI-Optimized Anaerobic Digestion

This protocol leverages machine learning to enhance the efficiency of biogas production [23].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Input Variable Collection: Compile a comprehensive dataset from historical or experimental runs of anaerobic digesters. Key input variables include:

- Feedstock Characteristics: Macronutrient ratios (Carbon/Nitrogen), composition, particle size, and volatile solids content.

- Process Parameters: Temperature, pH, hydraulic retention time, organic loading rate.

- Co-digestion Mixes: Types and ratios of different substrates (e.g., animal manure, food waste, sewage sludge) [23].

- Output Variable Definition: The primary output variable for model training is typically the Specific Methane Yield.

- Data Cleaning: Normalize the collected data to remove noise and handle missing values, creating a structured dataset for model training [23].

- Input Variable Collection: Compile a comprehensive dataset from historical or experimental runs of anaerobic digesters. Key input variables include:

Model Training and Optimization:

- Model Selection: Choose an appropriate AI model. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), particularly Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) or Backpropagation Neural Networks (BPNNs), are effective for capturing the non-linear relationships in anaerobic digestion. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) are also highly suitable [23].

- Training: Feed the preprocessed dataset into the selected model to learn the complex relationships between input parameters and methane yield.

- Prediction and Optimization: Use the trained model to predict methane yields under untested conditions. Furthermore, employ optimization algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) in conjunction with the AI model to identify the optimal set of input parameters that will maximize methane production and minimize carbon emissions [23].

Process Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biofuel Conversion Research

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Acetogenic Bacteria (e.g., Clostridium carboxidivorans, Alkalibaculum bacchi) | Key microbial catalysts for syngas fermentation. They convert CO, COâ‚‚, and Hâ‚‚ into alcohols and other products via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway [26]. |

| Biofuel Enzymes (e.g., Cellulases, Amylases, Lipases) | Biological catalysts that break down complex biomass polymers (cellulose, starch) into fermentable sugars or assist in transesterification for biodiesel production [7]. |

| Corn Steep Liquor | A low-cost, sustainable nutrient source used as a replacement for yeast extract in fermentation media to support microbial growth, improving process economics [26]. |

| Lignocellulosic Feedstock | Non-food biomass (e.g., agricultural residues, energy crops like switchgrass). Primary raw material for advanced (2nd-gen) biofuel processes, mitigating the "food vs. fuel" dilemma [2] [7]. |

| Gasification Agents (Air, Steam, Oxygen) | Reactants introduced into the gasifier to control the partial oxidation process, influencing the composition and quality of the produced syngas [23] [26]. |

| Machine Learning Models (ANN, SVM, ANFIS) | Computational tools used to model, predict, and optimize complex, non-linear biofuel production processes by analyzing vast datasets from experimental or operational systems [23]. |

| BC21 | BC21, MF:C32H40Cl2Cu2N2O2+, MW:682.7 g/mol |

| Jqad1 | Jqad1, MF:C48H52F4N6O9, MW:933.0 g/mol |

Agrivoltaics, the co-location of agriculture and solar photovoltaics (PV) on the same land parcel, represents a transformative approach to meeting growing global food and energy demands simultaneously [27]. By integrating solar energy production with agricultural activities, these systems address fundamental challenges in land-use competition while contributing significantly to renewable energy targets and climate change mitigation [28]. The conceptual foundation of agrivoltaics was established in 1981, but the practice has gained substantial momentum globally in recent decades, with countries like Japan operating nearly 2,000 agrivoltaic farms by 2021 [28].

The fundamental premise of agrivoltaics involves strategic land sharing to achieve multiple benefits that would not be possible when agriculture and energy production operate in isolation. These integrated systems are particularly valuable in the context of biofuel production, as they can enhance biomass yields while generating clean electricity, thereby creating synergistic relationships between energy crops and renewable energy infrastructure [27] [28]. Research demonstrates that agrivoltaic systems can increase overall land productivity by 60-70% compared to separate agricultural and energy production systems [28], making them particularly relevant for biomass production where land use efficiency is a critical consideration.

Comparative Analysis of Agrivoltaic System Performance

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The effectiveness of agrivoltaic systems for biomass production can be evaluated through multiple performance dimensions, including land productivity, water efficiency, and economic returns. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on agrivoltaic systems.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Agrivoltaic Systems for Biomass Production

| Performance Indicator | Traditional Agriculture | Agrivoltaic System | Improvement | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Productivity | Baseline | 60-70% higher overall productivity [28] | 60-70% | Multiple crop types |

| Land Use Efficiency | Single-purpose use | Dual production capacity [27] | Up to 200% improvement [27] | Systematic review |

| Crop Water Use Efficiency | Baseline | 157% for jalapeño peppers [28] | 57-157% | Arid conditions |

| Soil Moisture Retention | Daily irrigation required | 15% higher with bi-daily irrigation [28] | 15% reduction in irrigation frequency | Controlled study |

| Economic Returns | Single revenue stream | Multiple revenue streams [29] | Up to 15x higher revenue [27] | Financial analysis |

| Installation Costs | Conventional PV baseline | Co-located AVS [27] | 5-40% higher [27] | Cost comparison |

Biomass-Specific Production Data

Research on specific biomass crops in agrivoltaic systems reveals significant variations in performance based on crop type, solar configuration, and environmental conditions. The following table summarizes experimental data for crops relevant to biofuel production.

Table 2: Biomass Crop Performance in Agrivoltaic Systems

| Crop Type | Traditional Yield | Agrivoltaic Yield | Water Efficiency Change | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter Wheat | Baseline | 3% higher yield [28] | Not specified | Drought conditions |

| Potato | Baseline | 3% higher yield [28] | Not specified | Drought conditions |

| Celeriac | Baseline | Higher yield (specific % not provided) [28] | Not specified | Drought conditions |

| Tomatoes | Control baseline | Accelerated growth, larger fruit [30] | 65% improvement for cherry tomatoes [28] | Spectral filtering study |

| Pasture Grasses | Baseline | Maintained or improved productivity [27] | 150-300% improvement [27] | Livestock integration |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Field-Scale Agrivoltaic Research Design

The foundational methodology for assessing agrivoltaic systems involves comparative field studies with controlled experimental conditions. The California Central Valley study analyzed 925 solar PV arrays (2.53 GWp capacity covering 3,930 hectares) installed on former agricultural land [29]. Researchers employed a business-as-usual counterfactual scenario, comparing resource flows and economic outcomes against continued agricultural production without solar PV installation [29]. The experimental protocol included:

- Site Selection: Identification of agriculturally co-located solar PV installations through spatial analysis and land-use records

- Baseline Establishment: Documentation of pre-conversion agricultural practices, crop types, yields, and resource inputs

- Monitoring Framework: Tracking of electricity generation, water usage, and microclimate conditions post-conversion

- Economic Analysis: Calculation of landowner cash flows including net energy metering benefits and land lease agreements

- Resource Accounting: Comprehensive assessment of food, energy, and water (FEW) nexus impacts over projected 25-year system lifespan

This methodology enabled researchers to quantify trade-offs between displaced agricultural production and gains in energy generation, water conservation, and economic returns [29].

Spectral Optimization for Biomass Production

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) developed advanced experimental protocols for optimizing plant growth under solar panels through spectral manipulation [30]. The "No Photon Left Behind" project employed:

- BioMatch Filtering: Custom organic photovoltaic filters that transmit only the light spectrum most beneficial to specific plants while using remaining wavelengths for electricity generation

- Control Groups: Parallel cultivation of the same plant varieties under full solar spectrum conditions

- Growth Metrics: Continuous monitoring of plant height, leaf area, photosynthetic yield, and fruit production

- Environmental Controls: Identical irrigation, nutrient, and temperature conditions for both test and control groups

- Taste Testing: Blind sensory evaluation of produce to assess qualitative differences alongside quantitative metrics

This methodology demonstrated that tomatoes grown under spectrally-filtered light accelerated growth and produced larger fruits despite receiving 30% less total light [30].

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

Resource Flow Pathways in Agrivoltaic Systems

The diagram below illustrates the integrated resource flows and synergistic relationships in agrivoltaic systems for biomass production.

Experimental Workflow for Agrivoltaic Research

The following diagram outlines the systematic methodology for evaluating agrivoltaic systems for biomass production.

Research Reagent Solutions for Agrivoltaic Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Equipment for Agrivoltaic Biomass Studies

| Research Tool | Specifications | Application in Agrivoltaics | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Photovoltaic Filters | BioMatched spectral properties [30] | Selective light transmission | Optimize light spectrum for specific crops while generating electricity |

| Soil Moisture Sensors | Wireless, continuous monitoring capability | Below-panel soil moisture tracking | Quantify water conservation benefits and irrigation requirements |

| Portable Photosynthesis Systems | Infrared gas analysis, chlorophyll fluorescence | Plant physiological measurements | Assess photosynthetic efficiency under partial shading |

| Microclimate Stations | Multi-parameter (temp, humidity, radiation) | Microclimate characterization | Document moderated temperature extremes under solar arrays |

| Biomass Analysis Kits | Calorimetric, fiber composition analysis | Biomass quality assessment | Determine biofuel potential and chemical composition of crops |

| Drones with Multispectral Sensors | NDVI, thermal imaging capabilities | Crop health monitoring | Large-scale assessment of vegetation status across agrivoltaic facilities |

Discussion and Research Implications

Synergistic Benefits for Biofuel Production

Agrivoltaic systems demonstrate significant potential for enhancing the sustainability of biomass production for biofuels through multiple synergistic mechanisms. The microclimate moderation provided by solar panels reduces plant heat stress and water requirements, particularly valuable in arid regions where water scarcity limits agricultural productivity [27] [28]. Research shows that agrivoltaic systems can improve water use efficiency by 150-300% for certain crops, a critical advantage for biomass production where irrigation represents a substantial operational cost and environmental impact [27].

The dual-revenue model of agrivoltaics addresses fundamental economic challenges in biofuel feedstock production. By generating electricity alongside biomass, these systems can achieve up to 15 times higher revenue compared to conventional agriculture alone [27]. This economic resilience is particularly important for biofuel crops, which often face market volatility and competitive pressure from food crops. The integrated approach also mitigates land-use conflicts between energy and food production, a significant barrier to scaling biofuel operations [31].

Research Gaps and Future Directions

While current research demonstrates the viability of agrivoltaics for biomass production, several knowledge gaps require further investigation. First, optimal crop selection criteria for biofuel feedstocks in agrivoltaic systems need refinement, particularly regarding shade tolerance, water requirements, and biomass composition [27] [30]. Second, the performance of different solar panel technologies (bifacial vs. monofacial, fixed-tilt vs. tracking) with various biomass crops remains inadequately characterized [27]. Third, long-term impacts on soil health, nutrient cycling, and ecosystem services require monitoring beyond the typical research timeframe.

Future research should prioritize the development of integrated assessment frameworks that simultaneously evaluate energy production, biomass yield, environmental impacts, and socioeconomic factors [32] [33]. The SENSE project represents a promising approach, developing indicator matrices to quantify circularity within integrated crop-livestock-forestry systems [33]. Similar methodologies could be adapted specifically for agrivoltaic biofuel production systems, enabling more comprehensive sustainability assessments.

Advanced technologies like artificial intelligence and sensor networks offer significant potential for optimizing agrivoltaic systems for biomass production. AI algorithms can accelerate the development of specialized enzymes for biofuel processing [34], while integrated sensor networks can provide real-time monitoring of crop status and environmental conditions [33]. These technological innovations, combined with the fundamental synergies of agrivoltaic systems, position integrated land-use approaches as a promising pathway for sustainable biofuel production within the broader context of renewable energy transitions.

The transition from laboratory-scale innovation to industrial-scale production represents a critical juncture in the development of sustainable biofuels. This guide provides a comparative analysis of scalable production frameworks, focusing on the evolution from sequential optimization processes to integrated industrial applications. As global investment in bioenergy is projected to increase by 13% in 2025 [35], understanding the techno-economic and operational characteristics of different production pathways becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and development professionals. This analysis examines multiple biofuel generations and conversion technologies, providing structured comparative data to inform research and development priorities in the bioenergy sector.

Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Production Frameworks

Biofuel production technologies are categorized into generations based on feedstock type and technological sophistication. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these frameworks, highlighting their feedstocks, technological processes, yields, and scalability considerations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Production Frameworks by Generation

| Generation | Feedstock Type | Technology & Process | Yield (per ton feedstock) | Scalability Status | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|