Constraining Genome-Scale Models with 13C Data: A Comprehensive Guide to the 2S-13C MFA Method

Two-Scale 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (2S-13C MFA) is a powerful computational method that integrates high-resolution isotopic labeling data from 13C-tracer experiments with comprehensive genome-scale metabolic models.

Constraining Genome-Scale Models with 13C Data: A Comprehensive Guide to the 2S-13C MFA Method

Abstract

Two-Scale 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (2S-13C MFA) is a powerful computational method that integrates high-resolution isotopic labeling data from 13C-tracer experiments with comprehensive genome-scale metabolic models. This approach provides unprecedented insights into intracellular metabolic fluxes, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to map carbon and electron flow through entire metabolic networks without relying on evolutionary optimization assumptions. By applying the 'bow tie' approximation—which posits that carbon predominantly flows from core to peripheral metabolism with limited backflow—2S-13C MFA delivers robust flux estimates for both central carbon metabolism and peripheral pathways. This article explores the foundational principles, methodological workflows, optimization strategies, and validation frameworks for 2S-13C MFA, highlighting its transformative applications in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and biomedical research for quantifying cell physiology and identifying therapeutic targets.

Understanding the Core Principles and Bow-Tie Structure of Metabolism

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) is a computational and experimental methodology used to quantitatively determine the rates of metabolic reactions (fluxes) within biological systems. These fluxes represent the integrated functional phenotype of a cell, emerging from multiple layers of biological organization and regulation, including the genome, transcriptome, and proteome [1]. In the context of a broader thesis on 2S-13C MFA for genome-scale model constraint research, understanding MFA is fundamental as it provides the critical link between network reconstruction and physiological function.

The primary importance of MFA lies in its application across multiple domains of biological research and biotechnology. It serves as a powerful tool for (a) determining new metabolic pathways, (b) predicting toxic effects of new drugs, (c) identifying targets after genetic modifications, (d) explaining mechanisms of diseases, and (e) optimizing biotechnological processes in metabolic engineering [2]. For cancer research specifically, MFA has revealed critical insights into metabolic reprogramming, including the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis), reductive glutamine metabolism, and alterations in serine/glycine and one-carbon metabolism [3].

Several flux analysis techniques have been developed, each with distinct characteristics, applications, and data requirements. The table below summarizes the primary MFA methodologies used in contemporary research.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Metabolic Flux Analysis Methods

| Flux Method | Abbreviation | Labelled Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | FBA | No | Yes | Not Applicable | Uses optimization principles; genome-scale capability [4] [2] |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | MFA | No | Yes | Not Applicable | Uses stoichiometric models only; no isotopic data [2] |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis | 13C-MFA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Gold standard; incorporates 13C labeling data [4] [2] |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA | 13C-INST-MFA | Yes | Yes | No | Measures transient labeling; faster than 13C-MFA [2] |

| Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis | DMFA | No | No | Not Applicable | Models flux transients during culture [2] |

| 13C-Dynamic MFA | 13C-DMFA | Yes | No | No | Combines dynamic modeling with 13C labeling [2] |

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) represents the foundational constraint-based approach that uses linear programming to predict flux distributions by assuming the system optimizes an objective function, typically biomass production or growth rate [4] [1]. A key limitation is its reliance on evolutionary optimization principles, which may not hold for engineered strains not under long-term evolutionary pressure [4].

13C-MFA has emerged as the most authoritative and informative method for quantifying intracellular fluxes in central carbon metabolism [4] [3]. This approach uses stable isotope tracers (typically 13C-labeled substrates) to generate experimental data that strongly constrain possible flux distributions, eliminating the need to assume an optimization principle [4]. The method assumes both metabolic steady state (constant fluxes) and isotopic steady state (full incorporation of isotopes) [2].

Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) addresses a key limitation of traditional 13C-MFA by measuring transient labeling patterns before the system reaches isotopic steady state, significantly reducing experiment duration, particularly important for slow-growing cells [2].

Experimental Protocol for 13C-MFA

The following section provides a detailed, practical protocol for conducting 13C-MFA experiments, synthesizing information from multiple methodological guides and research applications.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Pre-culture and Metabolic Steady State Confirmation

- Cultivate cells in appropriate medium until metabolic steady state is achieved, where all metabolic fluxes remain constant over time [2].

- For proliferating cells, confirm exponential growth by plotting the natural logarithm of cell count versus time. The growth rate (μ, 1/h) is determined from the slope of this curve [3]:

- Nx = Nx,0 · exp(μ · t)

- where Nx is cell number, and t is time.

- Calculate doubling time: td = ln(2)/μ [3].

Step 2: Tracer Introduction and Isotopic Labeling

- Replace standard medium with identical medium containing 13C-labeled substrate(s).

- Common tracers for cancer studies include [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, or [U-13C]glutamine [2] [3].

- For 13C-MFA, continue incubation until isotopic steady state is reached (typically 4-24 hours for mammalian cells, depending on cell type and growth rate) [2].

- For INST-MFA, sample at multiple time points during the transient labeling phase before isotopic steady state is reached.

Step 3: Measurement of External Fluxes

- Quantify nutrient uptake and product secretion rates during the labeling experiment.

- For exponentially growing cells, calculate external rates (ri, nmol/10^6 cells/h) using:

- ri = 1000 · (μ · V · ΔCi)/ΔNx

- where V is culture volume (mL), ΔCi is metabolite concentration change (mmol/L), and ΔNx is change in cell number (millions) [3].

- Correct for glutamine degradation (approximately 0.003/h first-order degradation constant) and evaporation effects for long experiments [3].

Step 4: Metabolite Sampling, Quenching, and Extraction

- Rapidly quench metabolism using cold organic solvents (e.g., acetonitrile at -20°C) to stop all enzymatic activity immediately upon sampling [5] [2].

- Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate solvent systems.

- Separate samples for analysis of different metabolite classes (polar, non-polar).

Step 5: Analytical Measurement of Isotopic Labeling

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Approach: Analyze metabolite extracts using GC-MS or LC-MS to measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) - the fractions of molecules with 0,1,2,... 13C atoms [4] [2].

- NMR Spectroscopy Approach: Use 1H- or 13C-NMR to obtain positional labeling information [2] [6].

- For increased resolution, consider tandem mass spectrometry techniques, which allow quantification of positional labeling [1].

Step 6: Computational Flux Estimation

- Utilize specialized software tools (INCA, Metran, OpenFLUX) that implement the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework to efficiently simulate isotopic labeling [4] [3].

- Formulate as a least-squares parameter estimation problem, minimizing differences between measured and simulated labeling patterns [3].

- Include appropriate stoichiometric constraints and mass balances.

Step 7: Statistical Validation and Uncertainty Analysis

- Perform χ²-test of goodness-of-fit to evaluate model agreement with experimental data [1].

- Use statistical methods (e.g., Monte Carlo approaches) to estimate confidence intervals for flux estimates [1].

- Evaluate model fit by examining residuals between measured and simulated labeling data.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for 13C-MFA Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine, [2H7]glucose | Serve as metabolic tracers; carbon sources that introduce detectable labels into metabolic networks [2] [6] [3] |

| Cell Culture Media | Glucose-free DMEM, RPMI-1640 | Custom formulation with labeled substrates; control carbon source availability [6] [3] |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvents | Cold methanol, acetonitrile, chloroform | Quench metabolism; extract intracellular metabolites for analysis [5] [2] |

| Analytical Standards | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards | Quantification of metabolite concentrations; correction for analytical variation [5] |

| Software Platforms | INCA, Metran, OpenFLUX | Perform computational flux estimation; statistical analysis of labeling data [4] [3] |

Limitations of Metabolic Flux Analysis

Despite its powerful capabilities, MFA faces several significant limitations that researchers must acknowledge and address in experimental design and data interpretation.

Technical and Methodological Limitations

Network Scope Restrictions: Traditional 13C-MFA is typically limited to central carbon metabolism (glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle, and anaplerotic pathways) due to computational constraints and limited measurable labeling data [4] [2]. While methods exist to incorporate 13C labeling data with genome-scale models, these approaches remain challenging and computationally intensive [4].

Isotopic Steady State Requirement: Standard 13C-MFA requires the system to reach isotopic steady state, which can take 4-24 hours for mammalian cells, during which metabolic steady state must be maintained [2]. This limitation is particularly problematic for slow-growing cells or systems where metabolic changes occur rapidly.

Analytical Limitations: Current analytical techniques cannot measure all metabolites, creating gaps in labeling data. Additionally, technical limitations include:

- Inability to distinguish isomeric compounds without proper separation

- Difficulty measuring low-abundance metabolites

- Limited positional labeling information with standard MS approaches [2] [1]

Tracer Selection Constraints: Appropriate tracer selection is critical for flux resolution, but optimal tracer design is non-trivial. Different fluxes have varying sensitivity to different tracer patterns, requiring careful experimental design [3].

Computational and Theoretical Limitations

Underdetermined Systems: Metabolic networks typically contain more reactions than measurable fluxes, creating underdetermined systems with multiple feasible flux distributions [4] [1]. While 13C labeling data provides additional constraints, the problem often remains "sloppy" with some fluxes well-constrained and others poorly determined [4].

Model Validation Challenges: Statistical validation of flux models remains challenging. The χ²-test of goodness-of-fit, while widely used, has limitations including sensitivity to measurement error estimates and the potential for model incompleteness to be masked by overestimated errors [1].

Metabolic Steady State Assumption: The fundamental assumption of metabolic steady state limits application to dynamic biological processes. While INST-MFA and DMFA approaches address this limitation, they introduce significant computational complexity [2].

Compartmentation Challenges: Eukaryotic cells contain multiple metabolic compartments (mitochondria, cytosol) with potentially distinct metabolite pools. Most MFA approaches simplify or assume well-mixed pools, potentially missing important biological complexity [3].

Practical Implementation Limitations

Resource Intensity: 13C-MFA requires significant resources including:

- Costly isotopic tracers

- Specialized analytical instrumentation (GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR)

- Computational resources and expertise [3]

Technical Expertise Requirement: Successful implementation demands interdisciplinary expertise in cell culture, analytical chemistry, computational modeling, and statistics, creating barriers to adoption [3].

Scalability to Genome-Scale: While the field is advancing, robust integration of 13C labeling data with genome-scale models remains methodologically challenging. New approaches are needed to effectively use the full information content of 13C labeling data to constrain genome-scale models without relying on optimization principles [4].

Metabolic Flux Analysis provides powerful capabilities for quantifying metabolic phenotypes in biological systems, with 13C-MFA representing the gold standard for flux quantification in central carbon metabolism. The method continues to evolve with advances in INST-MFA, dynamic flux analysis, and computational approaches. However, researchers must remain cognizant of its limitations, particularly regarding network scope, steady-state assumptions, and computational challenges. For thesis research focused on 2S-13C MFA for genome-scale model constraint, addressing these limitations—particularly developing methods to effectively constrain larger network models with isotopic labeling data—represents a significant opportunity for methodological contribution and advancement in the field.

The Evolution from Traditional 13C-MFA to Two-Scale Approaches

For over two decades, 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has served as a cornerstone technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells [7]. By tracing the incorporation of stable 13C isotopes into metabolic pathways, researchers can determine the in vivo rates of biochemical reactions that define cellular physiology [8]. While traditional 13C-MFA has proven invaluable in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and biomedical research, it has been fundamentally limited by its reliance on small-scale metabolic models typically encompassing only central carbon metabolism [9]. This restriction becomes particularly problematic when engineering strains for biofuel production or investigating complex human diseases, where peripheral metabolic pathways play crucial roles [10].

The emergence of Two-Scale 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (2S-13C MFA) represents a paradigm shift that overcomes the scale limitations of traditional approaches [11]. This innovative framework combines the rich experimental constraints of isotopic labeling data with the comprehensive network coverage of genome-scale models, enabling researchers to obtain flux estimates for entire metabolic networks without requiring atom mapping information for every reaction [4]. By formally implementing the "bow tie" structure of cellular metabolism—where carbon sources flow through central metabolic pathways to generate precursor metabolites that then feed into peripheral biosynthesis—2S-13C MFA maintains mathematical tractability while expanding flux analysis to genome scale [11].

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Evolution

Limitations of Traditional 13C-MFA

Traditional 13C-MFA operates using skeletal metabolic networks typically comprising 50-100 reactions primarily from central carbon metabolism [9]. This simplified network structure has historically been necessary due to computational constraints, as the number of isotopic labeling equations scales super-linearly with network size [9]. The elementary metabolite unit (EMU) framework partially alleviated this burden through network decomposition, reducing the number of isotopomer variables from 4612 to 310 for a central metabolic network of E. coli [9]. Nevertheless, the fundamental limitation remained: only a small subset of cellular metabolism could be practically modeled.

This restricted scope introduces significant biological uncertainties, as peripheral reactions that consume or produce core metabolites can indirectly influence flux estimates in the central network [9]. For instance, failure to account for active degradation pathways or incomplete cofactor balances can substantially alter estimated flux ranges [9]. Additionally, traditional 13C-MFA provides no direct information about fluxes in peripheral metabolism, which is often precisely where metabolic engineers need to intervene to improve product yields [10].

Conceptual Framework of 2S-13C MFA

The 2S-13C MFA methodology addresses these limitations through a multi-resolution approach that distinguishes between core and peripheral metabolism [11]. The core encompasses central carbon metabolism and other reactions with defined atom transitions, while the periphery includes the remaining genome-scale reactions. The fundamental bow tie approximation posits that metabolic flux flows predominantly from core to peripheral metabolism with minimal backflow [11]. This assumption is biologically supported by the universal organization of metabolism around twelve precursor metabolites that serve as building blocks for most cellular components [11].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Traditional 13C-MFA vs. 2S-13C MFA

| Characteristic | Traditional 13C-MFA | 2S-13C MFA |

|---|---|---|

| Network Scale | Core metabolism (typically <100 reactions) | Genome-scale (typically >1000 reactions) |

| Atom Mapping Requirements | Required for all reactions in model | Required only for core reactions |

| Peripheral Flux Estimation | Not available | Provides flux estimates with confidence intervals |

| Computational Demand | Moderate | High, but manageable with specialized algorithms |

| Experimental Constraints | Isotopic labeling + extracellular fluxes | Isotopic labeling + extracellular fluxes + genome-scale stoichiometry |

| Implementation in Software | 13C-FLUX2, INCA [12] | jQMM library [11] |

Mathematically, 2S-13C MFA implements this conceptual framework by applying different constraint types to different network regions. For core reactions, both stoichiometric constraints and 13C labeling constraints are enforced, while for non-core reactions, only stoichiometric constraints are applied [10]. This dual-constraint system enables the method to leverage the rich information content of isotopic labeling data while maintaining the comprehensive coverage of genome-scale models.

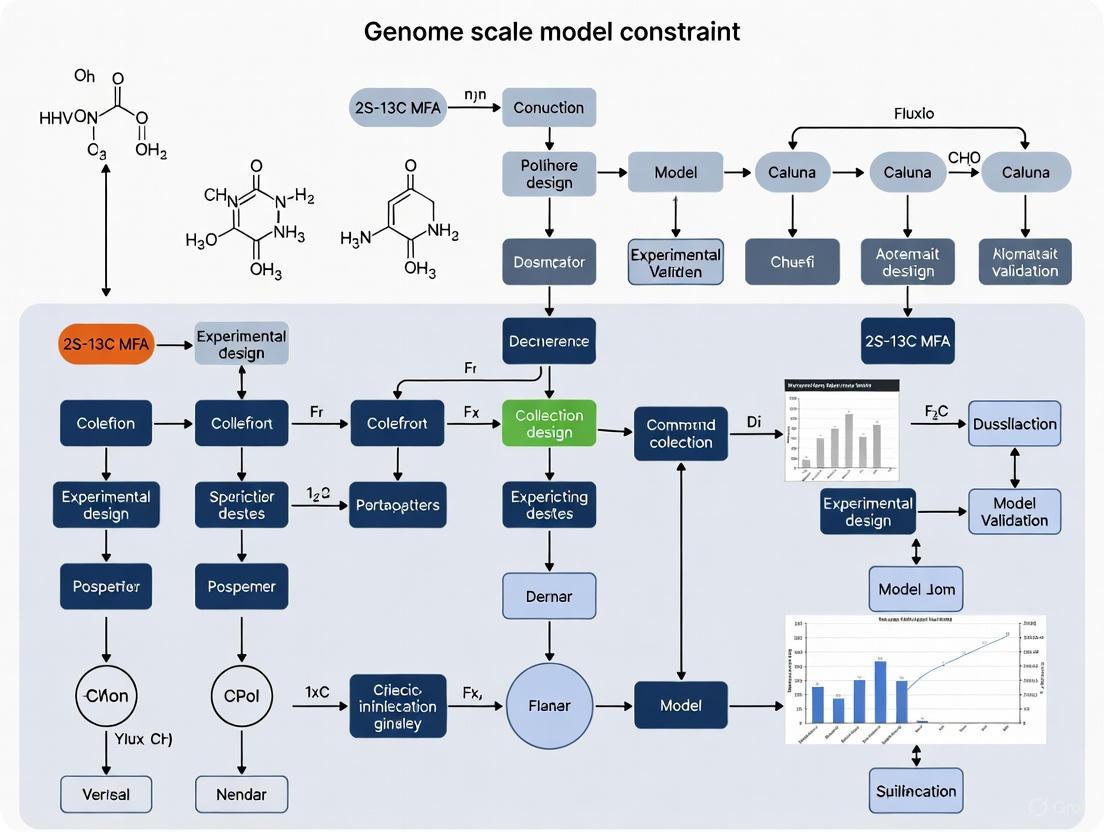

Diagram 1: Conceptual workflow comparison between traditional 13C-MFA and 2S-13C MFA approaches, highlighting the integration of genome-scale models with core metabolic constraints.

Computational Framework and Protocols

Core Algorithmic Implementation

The 2S-13C MFA methodology employs sophisticated algorithms to implement the bow tie approximation systematically. The "Limit Flux to Core" algorithm ensures that reactions with products in core metabolism have their fluxes minimized to the lowest values consistent with observed growth rates and extracellular metabolite measurements [11]. This procedure represents a significant improvement over earlier ad hoc implementations that relied on arbitrary cutoff values and sequential execution.

The algorithm begins by identifying core boundary reactions—those non-core reactions that have products in core metabolism and could potentially alter 13C labeling patterns [11]. Currency metabolites (e.g., ATP, NADH) that participate in core reactions but cannot contribute carbon to simulated metabolites are excluded from this set. Linear programming then identifies the minimum possible fluxes for these boundary reactions while maintaining feasibility with experimental growth and exchange flux measurements [11].

For reversible reactions that cross the core boundary, the algorithm considers only the unidirectional component with products in core metabolism. This nuanced approach ensures biologically relevant flux bounds while maintaining the bow tie approximation's validity. The result is a genome-scale model with refined flux constraints that enable more accurate flux estimation through subsequent 13C labeling analysis.

Core Reaction Set Optimization

A key innovation in 2S-13C MFA is the automated identification of optimal core reaction sets using Simulated Annealing [11]. This computational approach explores the space of possible core metabolisms, minimizing the total flux into the core—a quantitative metric for how well the bow tie approximation holds. The algorithm iteratively evaluates alternative core sets, seeking configurations that minimize backflow from peripheral to core metabolism while maintaining consistency with experimental data.

This automated core identification is particularly valuable when studying non-model organisms or specialized growth conditions where the boundaries of central metabolism may be ambiguous. By systematically evaluating core configurations rather than relying on predetermined reaction sets, researchers can ensure their models more accurately reflect the biological system under investigation.

Practical Implementation Protocols

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

Effective implementation of 2S-13C MFA begins with careful experimental design. Multi-objective optimization approaches can identify cost-effective tracer mixtures that maximize information content while minimizing experimental expenses [13]. For mammalian cells, optimal designs often include [1,2-13C2]glucose combined with uniformly labeled glucose, or [1,2-13C2]glucose with [U-13C]glutamine [13]. These mixtures provide superior flux resolution compared to single tracer experiments, particularly for resolving parallel pathways and metabolic cycles.

Table 2: Recommended Tracer Mixtures for Different Biological Systems

| Biological System | Recommended Tracers | Optimal Mixture | Information Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinoma Cell Lines | Glucose, Glutamine | 1,2-13C2 Glucose + U-13C Glutamine | Resolves TCA cycle fluxes, phosphoglucoisomerase activity |

| S. lividans | Glucose, Aspartate | 1,2-13C2 Glucose + U-13C Aspartate | Resolves pentose phosphate pathway, amino acid biosynthesis |

| S. cerevisiae | Glucose | 1,2-13C2 Glucose + U-13C Glucose | Resolves glycolytic and TCA cycle fluxes |

| E. coli | Glucose | 1,2-13C2 Glucose + U-13C Glucose | Comprehensive central carbon metabolism resolution |

Parallel labeling experiments using multiple tracers significantly enhance flux precision compared to individual tracer studies [1]. The increased resolution comes from the complementary information provided by different labeling patterns, which collectively constrain a broader range of fluxes. This approach is particularly valuable for resolving thermodynamically feasible flux loops and parallel pathway activities that may be ambiguous from single tracer data.

Analytical Measurement Protocols

Modern 2S-13C MFA leverages advancements in analytical platforms that have expanded measurement scope while reducing sample requirements [12]. For comprehensive flux analysis, the following protocol is recommended:

Sample Extraction: Use cold methanol:water (4:1) extraction for intracellular metabolites. Maintain samples at -20°C during processing to preserve labeling patterns.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Employ GC-MS or LC-MS platforms for mass isotopomer distribution (MID) measurements. For GC-MS, derivatize polar metabolites using MSTFA + 1% TMCS. For LC-MS, use HILIC chromatography for polar metabolite separation.

Data Processing: Acquire raw mass isotopomer distributions and correct for natural isotope abundances using standard algorithms [7]. Report uncorrected data alongside corrected values to ensure reproducibility.

Measurement Validation: Include technical replicates to estimate standard deviations for all measurements. Validate instrument performance with standard reference materials with known isotopic enrichment.

Advanced analytical techniques including tandem mass spectrometry and positional isotopomer analysis can provide additional resolution by quantifying labeling in specific fragment ions, further constraining flux solutions [1].

Computational Analysis Workflow

The computational workflow for 2S-13C MFA integrates multiple software tools and analytical steps:

Diagram 2: Computational workflow for implementing 2S-13C MFA, showing the sequential steps from model preparation to flux validation.

Application Case Study: Metabolic Engineering of S. cerevisiae

Engineering Background and Initial Strain

The power of 2S-13C MFA is exemplified by its application to engineer Saccharomyces cerevisiae for overproduction of fatty acids [10]. The parent strain WRY2 had been previously engineered with overexpression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC1) and fatty acid synthases (FAS1, FAS2), along with knockout of fatty acyl-CoA synthetases (FAA1, FAA4) to block fatty acid degradation. This strain produced approximately 460 mg/L of free fatty acids—a respectable titer but insufficient for commercial viability [10].

Initial engineering attempts focused on boosting cytoplasmic acetyl-CoA supply through introduction of a heterologous ATP citrate lyase (ACL) from Yarrowia lipolytica. This intervention was logically sound since acetyl-CoA is the direct precursor for fatty acid biosynthesis. Surprisingly, this genetic modification resulted in only a marginal (~5%) increase in fatty acid production, suggesting that the metabolic network had compensated through other routing decisions [10].

Flux Analysis and Targeted Engineering

Application of 2S-13C MFA to the ACL-engineered strain revealed the metabolic basis for the limited improvement: the additional acetyl-CoA was being largely consumed by malate synthase (MLS) rather than directed toward fatty acid synthesis [10]. The flux analysis identified MLS as the most significant acetyl-CoA sink after ACL introduction. This non-intuitive discovery would have been difficult to predict without comprehensive flux quantification.

Based on this insight, researchers downregulated malate synthase, which resulted in a substantial 26% increase in fatty acid production [10]. Subsequent flux analysis of this improved strain revealed another potential bottleneck: competition for carbon between the acetyl-CoA production pathway and the glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD1) pathway. Knocking out GPD1 further increased fatty acid production by 33% [10]. The cumulative effect of these targeted interventions—informed by sequential flux analysis—was an overall ~70% increase in fatty acid production over the original engineered strain.

Table 3: Summary of Genetic Interventions and Production Outcomes in S. cerevisiae Engineering

| Strain | Genetic Modifications | Free Fatty Acid Production | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| WRY2 (Parent) | ACC1↑, FAS1↑, FAS2↑, ΔFAA1, ΔFAA4 | 460 mg/L | Baseline |

| WRY2 + ACL | Above + ACL expression | ~483 mg/L | +5% |

| WRY2 + ACL + MLS↓ | Above + malate synthase downregulation | ~580 mg/L | +26% |

| WRY2 + ACL + MLS↓ + ΔGPD1 | Above + glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase knockout | ~782 mg/L | +70% |

Implementation Protocol for Strain Analysis

Researchers implementing similar metabolic engineering projects should follow this structured protocol:

Base Strain Characterization:

- Cultivate base strain in defined medium with 13C-labeled substrates

- Measure extracellular fluxes (growth rate, substrate consumption, product formation)

- Quantify mass isotopomer distributions for proteinogenic amino acids and intracellular metabolites

- Perform 2S-13C MFA to establish baseline flux distribution

Identification of Flux Limitations:

- Analyze flux confidence intervals to identify poorly constrained reactions

- Calculate flux control coefficients for target product formation

- Identify competing pathways and metabolite sinks

- Propose genetic interventions based on flux analysis

Iterative Strain Engineering and Validation:

- Implement genetic modifications in prioritized order

- Re-characterize engineered strains using 13C tracing and flux analysis

- Validate predicted flux changes and identify new limitations

- Continue engineering iterations until performance targets are met

This systematic approach demonstrates how 2S-13C MFA moves metabolic engineering from trial-and-error to a rational, predictive discipline.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 2S-13C MFA

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR Spectrometers | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions and positional labeling |

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C2]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine | Creating distinct labeling patterns to resolve metabolic fluxes |

| Computational Tools | jQMM Library, 13C-FLUX2, INCA, OpenFLUX [14] [12] | Performing flux estimation, statistical analysis, and model validation |

| Database Resources | MetRxn, KEGG, MetaCyc [9] | Accessing atom mapping information and reaction stoichiometries |

| Model Construction Tools | COBRA Toolbox, CarveMe, ModelSEED [8] | Building and curating genome-scale metabolic models |

The evolution from traditional 13C-MFA to two-scale approaches represents a significant advancement in metabolic flux analysis. By integrating the rich experimental constraints of isotopic labeling with the comprehensive coverage of genome-scale models, 2S-13C MFA enables researchers to obtain a systems-level view of metabolic flux distributions that was previously unattainable. The methodology's power stems from its formal implementation of the bow tie approximation of cellular metabolism, which allows for tractable computation while maintaining biological fidelity.

As demonstrated by the successful engineering of S. cerevisiae for fatty acid overproduction, 2S-13C MFA provides unique insights into metabolic network function that enable more rational and effective metabolic engineering strategies. The continued development of computational tools, analytical methods, and theoretical frameworks will further expand the applicability of this approach to increasingly complex biological systems, from microbial factories to human diseases.

The study of metabolism at a genome-scale requires frameworks to manage its inherent complexity. The bow-tie approximation provides a powerful architectural model for understanding the global organization of metabolic networks, distinguishing a central, highly interconnected core from specialized input and output peripheral pathways. This structure is not merely topological but fundamentally functional, with the giant strongly connected component (GSC) at the bow-tie core serving as the principal hub for mass flow and metabolic conversion [15]. For researchers employing advanced flux analysis techniques like Two-Scale 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (2S-13C MFA), this approximation offers a critical scaffold for constraining genome-scale models (GSMMs) and generating biologically meaningful flux predictions [16] [10]. This Application Note details experimental and computational protocols for applying the bow-tie framework within 2S-13C MFA studies, enabling a more accurate bridge between isotopic labeling data and system-wide metabolic flux distributions.

Theoretical Foundation: The Bow-Tie Architecture in Metabolism

In the bow-tie model, metabolites and reactions are classified into distinct subsets based on their connectivity and role in network-wide mass flow:

- IN Subset: Metabolites that can only be consumed to produce metabolites in the GSC. These are typically upstream nutrients and catabolic inputs.

- Giant Strongly Connected Component (GSC): The core "knot" of the bow-tie where all metabolites can be interconverted through balanced biochemical pathways. This encompasses central carbon metabolism (e.g., glycolysis, TCA cycle, pentose phosphate pathway) and key metabolic precursors [15].

- OUT Subset: Metabolites that can be produced from the GSC but cannot be consumed to regenerate GSC metabolites. These include anabolic products, biomass constituents, and secreted compounds.

- Isolated Subset (IS): Metabolites that are not connected to the GSC.

The diagram below illustrates the mass flow and the key subsets of the bow-tie architecture.

Traditional Graph-Based Analysis (GBA) often misclassifies metabolites into the GSC by including biologically impossible pathways, as it may ignore stoichiometric and thermodynamic constraints [15]. In contrast, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)-based pathway calculation ensures that only mass-balanced, thermodynamically feasible pathways are considered, leading to a more biologically relevant bow-tie structure. This accurate classification is paramount for effectively integrating 13C labeling data.

Experimental Protocol: FBA-Based Bow-Tie Structure Analysis

This protocol details the steps to determine the biologically relevant bow-tie structure of a genome-scale metabolic model using an FBA-based approach, as validated in BMC Microbiology [15].

Prerequisite Software and Tools

- COBRA Toolbox: A MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling. Required functions:

gapAnalysis,checkMassChargeBalance[15]. - GUROBI Optimizer or similar linear programming solver (e.g., CPLEX) integrated with the COBRA Toolbox.

- BiGG Models Database: A resource for high-quality, curated genome-scale metabolic models (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli) [15].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Model Preprocessing and Curation

- Obtain a genome-scale metabolic model in SBML format.

- Critical Step - Add Special Demand Reactions: For metabolites containing carrier groups (e.g., CoA, ACP, THF, UDP), add demand reactions that allow the carrier to be recycled. This is essential for calculating feasible conversion pathways for acyl-CoA molecules and similar metabolites.

- Example: For Acetyl-CoA (AcCoA), add a demand reaction:

AcCoA ⟶ CoA. When calculating production of AcCoA, the objective is set toAcCoA ⟶ CoA, allowing the CoA moiety to be recycled rather than synthesized from the carbon source [15].

- Example: For Acetyl-CoA (AcCoA), add a demand reaction:

Identification of the GSC Core

- Select a set of key central metabolites (e.g., the 12 biosynthetic precursors: Glc6P, Fru6P, Rib5P, Ery4P, Sed7P, Gly3P, 3PG, PEP, Pyr, AcCoA, OAA, AKG).

- For every pair of metabolites (A, B) in this set, perform two FBA simulations:

- Feasible Production from A to B: Set the uptake of A and the production of B as constraints. Set the objective to maximize the flux of B's export reaction. A non-zero solution confirms A can be converted to B.

- Feasible Production from B to A: Reverse the process. A non-zero solution confirms B can be converted to A.

- Metabolites that can be interconverted with all others in the set through mass-balanced pathways belong to the GSC.

Comprehensive Connectivity Mapping

- Choose a single "seed" metabolite from the confirmed GSC (e.g., pyruvate).

- For every other metabolite (X) in the model, perform two FBA simulations:

- Can X be produced from the seed? Set seed uptake and maximize production of X.

- Can the seed be produced from X? Set X uptake and maximize production of the seed.

- Classify metabolite X based on the results using the logic in the table below.

Table 1: Metabolite Classification in the Bow-Tie Structure

| Production from Seed | Production of Seed | Bow-Tie Subset | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | GSC | Central intermediate |

| No | Yes | IN | Input nutrient |

| Yes | No | OUT | Output product |

| No | No | IS | Peripheral or disconnected metabolite |

- Validation with Carbon Yield

- Calculate the carbon yield (C-atoms in product / C-atoms in substrate) for all identified pathways.

- Pathways with abnormally low carbon yields (< 0.1) should be inspected, as the target metabolite may not be the main product, indicating a potentially misclassified metabolite that requires further manual curation [15].

Integration with 2S-13C MFA

The 2S-13C MFA method leverages the bow-tie structure to efficiently integrate labeling data from core metabolites with the extensive stoichiometry of genome-scale models. The workflow below outlines this integration.

Core Requirements for 2S-13C MFA Integration:

- Core Model Definition: The GSC, as identified in Section 3.2, forms the core model for detailed 13C isotopomer simulation. This includes reactions from glycolysis, TCA cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway [10].

- Peripheral Metabolism: Reactions in the IN, OUT, and IS subsets are simulated using only stoichiometric constraints (from FBA), as their contribution to the labeling patterns of core metabolites is assumed to be negligible [10].

- Software Implementation: Tools like Isodyn (for dynamic or steady-state label simulation) or BayFlux (for Bayesian flux inference on GSMMs) can be adapted to implement this two-scale approach [17] [18].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of Bow-Tie Structures

The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of bow-tie structures in the E. coli iML1515 model, revealing the critical differences between GBA and the more accurate FBA-based method.

Table 2: Comparative Bow-Tie Analysis of E. coli iML1515 Model [15]

| Metric | Graph-Based Analysis (GBA) | FBA-Based Analysis (Protocol 3.2) | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSC Size | Significantly larger | ~1095 metabolites produced from Pyruvate~1072 metabolites consumed to produce Pyruvate | FBA excludes infeasible pathways, giving a more realistic core. |

| Pathway Quality | Includes biologically impossible routes | All pathways are stoichiometrically and thermodynamically feasible | Ensures model predictions are physiologically relevant. |

| Carbon Yield | Not typically calculated | Ranged from 6% to 100% for precursor conversions | Enables evaluation of pathway efficiency; identifies misclassified metabolites (yield << 1). |

| Key Insight | Overestimates connectivity | Reveals essential core and correct metabolite classification | Provides a robust foundation for 2S-13C MFA. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Software for 2S-13C MFA within a Bow-Tie Framework

| Item | Function / Application in Protocol | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracers for 13C labeling experiments to constrain fluxes in the core GSC. | [1,2-13C2] Glucose; [U-13C5] Glutamine [13] [18]. Cost: ~3x more expensive than uniformly labeled glucose [13]. |

| Isodyn Software | Simulates the dynamics of metabolite labeling by stable isotopic tracers; can be applied to core metabolism. | C++ program; solves ODEs for isotopologue concentrations [18]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Performs FBA, gap-filling, and model curation essential for the FBA-based bow-tie analysis. | MATLAB-based; requires a linear programming solver (e.g., GUROBI) [15]. |

| BayFlux Software | Implements Bayesian inference for MFA on GSMMs, quantifying flux uncertainty in genome-scale models. | Uses MCMC sampling; available as cited in PLoS Computational Biology [17]. |

| Demand Metabolites | Critical model components for simulating carrier-group recycling (CoA, ACP, THF, UDP, etc.). | Must be added to model during preprocessing to enable correct pathway analysis for CoA-derived metabolites [15]. |

| N-Propyl-p-toluenesulfonamide | N-Propyl-p-toluenesulfonamide | High-Purity Reagent | N-Propyl-p-toluenesulfonamide for organic synthesis & pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Butyl phenylcarbamodithioate | Butyl phenylcarbamodithioate | High-Purity Reagent | RUO | Butyl phenylcarbamodithioate is a xanthate derivative for organic synthesis & metal chelation research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Key Biological Justifications for the Two-Scale Framework

The integration of 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C MFA) with Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) represents a paradigm shift in constraint-based modeling. This two-scale framework, termed 2S-13C MFA, addresses fundamental limitations in both approaches by creating a synergistic relationship between experimental flux measurements and computational predictions. GEMs provide a comprehensive network of metabolic reactions but often yield degenerate flux solutions with limited biological accuracy due to underdetermination [19]. Conversely, 13C MFA delivers precise, quantitative flux measurements for core central metabolism but lacks genome-scale coverage [20]. The biological justification for this integration stems from the inherent multi-scale nature of cellular metabolism, where local pathway kinetics and global network functionality are intrinsically interconnected. This application note details the protocols, analytical frameworks, and practical implementations for applying the 2S-13C MFA framework to achieve biologically accurate, context-specific flux predictions.

Biological Rationale and Theoretical Foundation

The Multi-Scale Nature of Metabolic Systems

Cellular metabolism operates across multiple spatial and temporal scales. At the local pathway scale, enzyme kinetics and metabolite concentrations determine reaction velocities, which can be precisely quantified using 13C MFA for central carbon pathways. At the genome scale, network functionality emerges from system-wide constraints including reaction stoichiometry, mass conservation, and thermodynamic feasibility [21]. The 2S-13C MFA framework formally recognizes that these scales are not independent; rather, fluxes in core metabolic pathways constrain and are constrained by the broader metabolic network.

The critical biological insight is that local flux measurements from 13C MFA provide ground-truth data that reflect the integrated effects of cellular regulation—including allosteric control, post-translational modifications, and metabolic channeling—that are not explicitly represented in stoichiometric GEMs. By embedding these experimental measurements as constraints in GEMs, the resulting models inherently capture these regulatory effects, leading to more accurate predictions of system-wide metabolic phenotypes [19] [20].

Addressing the Principle of "Forcedly Balanced Complexes"

Recent theoretical work has revealed that metabolic networks contain multireaction dependencies that extend beyond simple pairwise coupling [21]. These dependencies arise from "forcedly balanced complexes"—biochemical complexes (mathematical constructs representing reactant or product sets) that must satisfy balance equations under steady-state conditions. When 13C MFA data is incorporated into GEMs, it effectively forces balance at specific complexes within the network, creating cascading constraints throughout the system. This phenomenon provides a mathematical basis for how relatively few experimental flux measurements can dramatically improve genome-scale flux predictions.

Table 1: Key Concepts in Multi-Scale Metabolic Analysis

| Concept | Theoretical Basis | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Forcedly Balanced Complexes | Complexes where incoming and outgoing fluxes must balance at steady state [21] | Creates system-wide flux dependencies that propagate local constraints |

| Concordance Modules | Sets of complexes with coupled activities across all steady states [21] | Identifies functional metabolic units that respond coordinately to perturbations |

| Coefficients of Importance | Quantifies each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives [22] | Reveals how metabolic networks prioritize reactions under different conditions |

Computational Frameworks and Methodologies

Topology-Informed Objective Finding (TIObjFind)

The TIObjFind framework provides a sophisticated methodology for integrating multi-scale metabolic data. This approach combines Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to systematically infer context-specific metabolic objectives from experimental data [22]. The framework operates through three key computational steps:

Optimization Problem Formulation: Reformulates objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes differences between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal.

Mass Flow Graph Construction: Maps FBA solutions onto a directed, weighted graph that enables pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions.

Pathway Extraction: Applies a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to identify critical pathways and compute "Coefficients of Importance" that quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives.

The resulting framework enhances interpretability of complex metabolic networks by focusing analysis on biologically relevant pathways rather than the entire network, effectively bridging the gap between local flux measurements and global network function [22].

Dynamic Integration Approaches

For modeling metabolic dynamics, the Linear Kinetics-Dynamic FBA (LK-DFBA) framework addresses the critical challenge of capturing metabolite dynamics while retaining computational tractability [23]. This approach discretizes time and "unrolls" the system into a larger stoichiometric matrix that captures metabolite dynamics while maintaining a linear programming structure. The method incorporates linear kinetic constraints that model interactions between metabolites and the reactions they regulate, enabling dynamic simulations without requiring extensive parameter estimation typical of ordinary differential equation models [23].

Table 2: Computational Frameworks for Multi-Scale Metabolic Modeling

| Framework | Primary Function | Advantages | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind | Infers metabolic objectives from experimental data [22] | Topology-informed; Reduces overfitting; Enhances interpretability | MATLAB with Python visualization |

| LK-DFBA | Captures metabolite dynamics in large networks [23] | Retains LP structure; Fewer parameters than ODE models; Computationally efficient | Linear programming with kinetic constraints |

| ANN-FBA Surrogate | Replaces iterative FBA with rapid predictions [24] | Several orders of magnitude faster; Numerically stable | Artificial Neural Networks trained on FBA solutions |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: 13C MFA Experimental Workflow for Ground-Truth Flux Data

Purpose: To generate high-quality experimental flux data for constraining genome-scale models.

Materials:

- 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose)

- Cell culture system (bioreactor or culture flasks)

- Quenching solution (cold methanol for intracellular metabolite arrest)

- Extraction buffer (methanol:chloroform:water for metabolite extraction)

- LC-MS/MS system for metabolite detection and isotopomer distribution analysis

- Data processing software (e.g., OpenFlux, INCA, Metran)

Procedure:

- Culture Setup: Grow cells in defined medium with 13C-labeled carbon source under controlled environmental conditions.

- Metabolite Sampling: Collect samples at metabolic steady-state (verified by constant metabolite concentrations).

- Rapid Quenching: Immerse samples in -40°C quenching solution to immediately arrest metabolic activity.

- Metabolite Extraction: Use extraction buffer to recover intracellular metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Measure mass isotopomer distributions of key metabolic intermediates.

- Flux Calculation: Compute metabolic fluxes by fitting isotopomer data to metabolic network model using computational software.

Critical Considerations: Ensure metabolic steady-state throughout labeling experiment; Verify labeling uniformity; Use multiple tracer compounds for comprehensive flux resolution.

Protocol 2: Computational Integration of 13C MFA Data with GEMs

Purpose: To incorporate experimental flux measurements as constraints in genome-scale models.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (SBML format)

- 13C MFA flux measurements with confidence intervals

- Constraint-based modeling software (COBRA Toolbox, CVX, MATLAB)

- Optimization solver (Gurobi, CPLEX)

Procedure:

- Model Preparation: Load GEM and verify mass and charge balance of all reactions.

- Flux Constraint Definition: For each reaction with 13C MFA data, set flux bounds based on experimental measurements ± confidence interval.

- Model Contextualization:

- Apply additional constraints (e.g., nutrient uptake, byproduct secretion)

- Implement thermodynamic constraints if available

- Flux Variability Analysis: Determine the solution space for each reaction given the applied constraints.

- Objective Function Validation: Test multiple biologically relevant objective functions against experimental data.

- Model Validation: Compare predictions with independent experimental data not used for constraint.

Implementation Note: The TIObjFind framework can be applied at step 5 to systematically identify objective functions that best align with the experimental data [22].

Visualization and Data Integration Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the complete 2S-13C MFA framework, integrating both experimental and computational components:

Two-Scale 13C MFA Framework

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | 13C-labeled substrates | >99% isotopic purity; Multiple labeling patterns | 13C MFA tracer experiments |

| Quenching solution | Cold methanol (-40°C) | Immediate metabolic arrest | |

| Metabolite extraction buffer | Methanol:chloroform:water (specific ratios) | Intracellular metabolite recovery | |

| Computational Tools | COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based constraint-based modeling platform | GEM simulation and analysis [19] |

| TIObjFind code | MATLAB implementation with Python visualization | Objective function identification [22] | |

| LK-DFBA framework | Linear programming with kinetic constraints | Dynamic metabolic modeling [23] | |

| ANN surrogate models | Pre-trained neural networks for FBA | Rapid flux prediction in RTM coupling [24] |

Application in Metabolic Engineering and Drug Development

The 2S-13C MFA framework has transformative potential in both metabolic engineering and drug development. For industrial biotechnology, it enables identification of forcedly balanced complexes with high control over product formation, facilitating targeted engineering of metabolic pathways for enhanced compound production [21]. In pharmaceutical research, the framework can identify metabolic vulnerabilities in pathogens or cancer cells by revealing essential reactions that become lethal when perturbed, providing novel therapeutic targets [21].

Case studies demonstrate the power of this approach. In multi-species systems, the TIObjFind framework successfully captured stage-specific metabolic objectives and showed good agreement with experimental data [22]. Similarly, ANN-based surrogate FBA models enabled rapid simulation of metabolic switching in Shewanella oneidensis, achieving several orders of magnitude reduction in computational time while maintaining accuracy [24].

The 2S-13C MFA framework provides a robust methodological foundation for multi-scale metabolic analysis, addressing fundamental biological challenges in metabolic modeling. By formally integrating experimental flux measurements with genome-scale network reconstructions, this approach captures both the quantitative precision of 13C MFA and the comprehensive coverage of GEMs. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with practical tools to implement this framework across diverse biological systems, from microbial engineering to human disease research. As metabolic modeling continues to evolve, the two-scale integration principle will remain essential for bridging the gap between local pathway kinetics and global network function.

The accurate determination of intracellular metabolic fluxes is crucial for advancing metabolic engineering and systems biology. Metabolic fluxes represent the in vivo conversion rates of metabolites, providing a direct window into a cell's metabolic state and its response to genetic or environmental perturbations [25]. Among the various techniques available, the integration of genome-scale models with 13C labeling data has emerged as a powerful approach for constraining metabolic networks and obtaining precise, system-wide flux estimates. This integration addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which relies on evolutionary optimization principles like growth rate maximization—an assumption that often fails for engineered strains not under long-term evolutionary pressure [26] [4]. The 2S-13C MFA method represents a significant advancement in this field, enabling researchers to leverage the comprehensive coverage of genome-scale models while incorporating the rigorous experimental constraints provided by 13C labeling data, thereby eliminating the need for potentially flawed optimization assumptions [26].

Methodological Framework

Core Concepts and Definitions

The 2S-13C MFA framework is built upon several foundational concepts:

- Metabolic Flux: The in vivo conversion rate of metabolites, including enzymatic reaction rates and transport rates between compartments [25]. Fluxes are typically expressed in units of mmol/gDW/h.

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM): A mathematical representation of the entire metabolic network encoded in an organism's genome, containing hundreds to thousands of biochemical reactions [27].

- 13C Labeling Data: Measurements of isotopic label distribution within intracellular metabolites after feeding cells with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose). The labeling pattern is highly dependent on the flux profile through metabolic pathways [26] [4].

- Mass Distribution Vector (MDV): The fraction of molecules with 0, 1, 2,… 13C atoms incorporated for a given metabolite [26] [4].

The 2S-13C MFA Workflow

The 2S-13C MFA method implements a two-stage approach that effectively constrains genome-scale models using 13C labeling data. The procedure makes the biologically relevant assumption that flux flows predominantly from core to peripheral metabolism without significant backflow, thereby providing strong flux constraints without requiring optimization assumptions [26].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this methodology:

Comparative Analysis of Flux Analysis Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major flux analysis methodologies, highlighting the position of 2S-13C MFA within the methodological landscape:

| Method | Network Scope | Constraints Used | Optimization Principle | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) [26] | Central metabolism (~50 reactions) | Extracellular fluxes, Stoichiometry | None (deterministic calculation) | Metabolic engineering, Biotechnology |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [26] [27] | Genome-scale (>1000 reactions) | Stoichiometry, Capacity constraints | Growth rate maximization | Strain design, Community modeling |

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) [26] [25] | Central metabolism (~100 reactions) | 13C labeling data, Stoichiometry | Fit to labeling data | Pathway elucidation, Metabolic phenotyping |

| 2S-13C MFA [26] | Genome-scale | 13C labeling data, Stoichiometry, Flux coupling | Fit to labeling data | Systems metabolic engineering |

Experimental Protocols

Labeling Experiment Design and Execution

The acquisition of high-quality 13C labeling data is fundamental to the 2S-13C MFA method. The following protocol outlines the critical steps:

Tracer Selection: Choose appropriate 13C-labeled substrates based on the metabolic pathways of interest. Common choices include:

- [U-13C]glucose (uniformly labeled)

- [1-13C]glucose

- Mixtures of labeled and unlabeled glucose [25]

- 13C-acetate or 13C-glycerol for specific pathways

Cell Cultivation: Grow cells in controlled bioreactors (e.g., chemostats) under defined metabolic conditions. For E. coli cultures, use a dilution rate of 0.19 hâ»Â¹ and monitor cell density (target: ~1.6 g/L) and residual substrate concentration (e.g., glucose consumption: ~6.1 g/L) [28].

Isotopic Steady-State Achievement: Maintain constant labeling until isotopic steady state is reached, where the isotopic patterns of intracellular metabolites no longer change with time [25].

Metabolite Sampling and Quenching: Rapidly collect cell samples (typically 10-20 mL) and immediately quench metabolism using cold methanol (-40°C) to preserve isotopic patterns.

Metabolite Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites using a methanol-water-chloroform system. Derivatize metabolites for GC-MS analysis using standard protocols (e.g., methoximation and silylation) [29].

Analytical Measurement of Isotopic Labeling

Accurate measurement of isotopic labeling is performed using mass spectrometry:

Instrument Configuration: Utilize GC-MS systems operated in electron impact ionization mode. Select appropriate scan ranges (e.g., m/z 50-600) for comprehensive metabolite detection.

Chromatographic Separation: Employ DB-5MS or similar capillary columns (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness) with helium as carrier gas (1.0 mL/min). Use a temperature gradient from 60°C to 325°C at 10°C/min [29].

Data Acquisition: Acquire data in either Full Scan or Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode. For targeted flux analysis, SIM mode provides better sensitivity for specific metabolites.

Data Processing: Process raw GC-MS data using specialized software such as DExSI for automated peak annotation, integration, and natural isotope abundance correction [29]. The software identifies metabolites based on retention time and mass spectral patterns, then quantifies the abundance of each mass isotopologue.

Computational Flux Analysis

The computational workflow for 2S-13C MFA involves several key steps:

Model Compilation: Start with a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction in SBML format. The model should include compartmentalization and subsystem assignments [30].

Flux Estimation Formulation: Set up the flux estimation as a non-linear optimization problem:

argmin: (x - xM)Σε(x - xM)^T s.t.: S·v = 0 M·v ≥ b A1(v)X1 - B1Y1(y1in) = dX1/dt ... An(v)Xn - BnYn(ynin, Xn-1, ..., X1) = dXn/dt

Where v represents metabolic fluxes, S is the stoichiometric matrix, x is the vector of simulated isotopic labeling, and xM is the measured labeling data [25].

Parameter Optimization: Solve the optimization problem using non-linear algorithms (e.g., sequential quadratic programming) to find the flux distribution that best explains the experimental labeling data.

Statistical Analysis: Evaluate flux confidence intervals using Monte Carlo sampling or sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the flux estimates [31].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Successful implementation of 2S-13C MFA requires specific reagents, software tools, and computational resources. The table below details the essential components:

| Category | Item/Software | Specific Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labeled Substrates | [U-13C] Glucose | Tracer for carbon labeling experiments | >99% atom 13C [32] |

| [1-13C] Glucose | Tracer for specific pathway analysis | >99% atom 13C [32] | |

| Analytical Software | DExSI [29] | GC-MS data processing for labeled metabolites | Automated peak annotation, Natural isotope correction |

| mfapy [31] | Python package for 13C-MFA | Flexible flux estimation, Simulation capabilities | |

| INCA [32] | Isotopically non-stationary MFA | INST-MFA support, Comprehensive flux mapping | |

| 13CFLUX2 [32] | Metabolic flux analysis | Steady-state MFA, Extensive modeling features | |

| Visualization Tools | MetDraw [30] | Automated visualization of genome-scale models | SBML import, Pathway mapping with omics data |

| VANTED [29] | Visualization of isotopic labeling data | Pathway mapping, Heat map generation | |

| Computational Resources | COBRA Toolbox [26] | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | MATLAB-based, Model simulation & gap-filling |

| SCIP Solver [33] | Optimization for gap-filling and FBA | Mixed-integer programming, High performance |

Applications and Significance

The 2S-13C MFA method provides a reliable platform for improving the design of biological systems [26]. Its unique capability to integrate genome-scale coverage with experimental validation through labeling data makes it particularly valuable for:

Metabolic Engineering: Identification of flux bottlenecks in engineered strains and validation of metabolic interventions. The method has contributed to industrial-scale production of chemicals like 1,4-butanediol [26] [4].

Drug Discovery: Elucidation of pathogen metabolism (e.g., Leishmania mexicana, Toxoplasma gondii) for identifying novel drug targets [29].

Biomedical Research: Investigation of metabolic alterations in disease states, including cancer [26], diabetes [25], and neurological disorders [25].

Microbial Community Modeling: Constraint-based modeling of multi-species consortia for environmental applications and synthetic ecology [27].

The method's robustness to errors in genome-scale model reconstruction and its ability to provide a comprehensive picture of metabolite balancing while maintaining consistency with experimental labeling data represents a significant advancement over traditional approaches [26].

Implementing 2S-13C MFA: From Experimental Design to Flux Calculation

The selection of appropriate carbon tracers is a critical first step in the design of 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) studies. Within the context of the Two-Scale 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (2S-13C MFA) method for genome-scale model constraint research, this choice fundamentally determines the information content that can be extracted from labeling experiments to constrain comprehensive metabolic networks [14]. Unlike traditional 13C-MFA that focuses on central metabolism, 2S-13C MFA aims to provide flux estimates for genome-scale models, making tracer selection even more crucial as it must inform fluxes across a broader metabolic landscape [4] [9].

The fundamental challenge in tracer selection stems from the complex relationship between substrate labeling patterns and the resulting isotopic distributions in intracellular metabolites. Different metabolic pathways produce distinct labeling patterns that serve as fingerprints for flux activity [3]. Carefully selected tracers maximize the information gain for precise flux estimation, while poor tracer choices can leave key fluxes unidentifiable [34] [35]. This protocol provides a systematic framework for selecting optimal 13C tracers and mixtures, with particular emphasis on applications within 2S-13C MFA methodology.

Theoretical Foundation: How Tracer Design Impacts Flux Observability

Fundamental Concepts in 13C-MFA

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis leverages stable isotopic tracers to infer in vivo metabolic reaction rates (fluxes). When cells metabolize 13C-labeled substrates, enzymatic reactions rearrange carbon atoms, producing specific isotopic patterns in downstream metabolites that can be measured using mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [3]. The core principle is that different flux distributions produce distinct isotopic labeling patterns, allowing researchers to mathematically infer the underlying fluxes that best explain the experimental labeling data [25].

The emergence of the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework has significantly advanced 13C-MFA by simplifying the computational burden of simulating isotopic labeling in complex metabolic networks [34] [3]. This framework forms the basis for modern 13C-MFA software tools and enables the extension of flux analysis to genome-scale models through methods like 2S-13C MFA [9] [14].

Tracer Selection and Flux Observability

The concept of flux observability is central to tracer selection. A flux is considered observable if its value can be precisely determined from the available labeling data [34]. The number of independent EMU basis vectors in a network model imposes fundamental limits on how many free fluxes can be determined [34]. By maximizing independent EMU basis vectors through strategic tracer selection, researchers can significantly improve system observability.

Different tracers illuminate different metabolic pathways. For instance, while [1,2-13C]glucose effectively labels glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway, [U-13C]glutamine may be more appropriate for probing TCA cycle fluxes [36]. In 2S-13C MFA, where the goal is to constrain fluxes across genome-scale models, complementary tracers are often necessary to achieve sufficient coverage of the metabolic network [4] [9].

Computational Framework for Tracer Evaluation

Metrics for Evaluating Tracer Performance

Several quantitative metrics have been developed to evaluate tracer performance for 13C-MFA:

Precision Score: This metric evaluates the statistical precision of flux estimates obtained with a particular tracer. It is calculated based on the confidence intervals of the estimated fluxes, with narrower intervals resulting in higher scores [35]. The precision score can be computed as:

( P = \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n} pi ) with ( pi = \left( \frac{(UB{95,i} - LB{95,i}){ref}}{(UB{95,i} - LB{95,i})_{exp}} \right)^2 )

where ( UB{95,i} ) and ( LB{95,i} ) represent the upper and lower 95% confidence bounds for flux i, and "ref" denotes a reference tracer experiment [35].

Synergy Score: This metric is specifically designed for evaluating combinations of tracers in parallel labeling experiments. It quantifies whether the combined information from multiple tracers provides more information than any single tracer alone [35].

D-Optimality Criterion: A classical design criterion that evaluates the determinant of the Fisher information matrix, which relates to the volume of the confidence ellipsoid of the parameter estimates [37].

Design Approaches for Optimal Tracer Selection

Table 1: Computational Approaches for Optimal Tracer Design

| Approach | Key Features | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search [35] | Systematic evaluation of predefined tracers using linearized statistics | Single tracer selection; Limited tracer sets | Computationally efficient but may miss optimal solutions |

| Genetic Algorithm [36] | Evolutionary optimization of tracer mixtures; Tournament selection | Complex tracer mixtures; Multiple substrates | Handles large search spaces; Requires careful parameter tuning |

| Robustified Experimental Design (R-ED) [37] | Flux space sampling to account for uncertainty in prior flux knowledge | Novel organisms/systems with limited prior knowledge | Computationally intensive but robust to flux uncertainty |

| Precision-Score Based Screening [35] | Direct evaluation using nonlinear confidence intervals | Comprehensive tracer evaluation; Parallel labeling designs | Avoids linearization approximations; Computationally demanding |

Diagram 1: Workflow for Computational Design of Optimal 13C Tracers. This workflow outlines the decision process for selecting optimal tracers based on available prior knowledge and research objectives. The Robustified Experimental Design path is particularly relevant for 2S-13C MFA applications with limited prior flux information.

Recommended Tracers for 13C-MFA

Single Tracer Recommendations

Table 2: Optimal Single Tracers for 13C-MFA

| Tracer | Precision Score* | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1,6-13C]glucose [35] | 1.00 | Central carbon metabolism; Glycolysis/PPP splits | Highest precision for most fluxes; Commercially available | Limited TCA cycle resolution |

| [1,2-13C]glucose [35] | 0.95 | Pentose phosphate pathway; Glycolytic fluxes | Excellent for PPP and upper glycolysis | Lower precision for TCA cycle |

| [5,6-13C]glucose [35] | 0.92 | TCA cycle; Anaplerotic reactions | Good TCA cycle resolution | Weaker for glycolytic fluxes |

| [U-13C]glutamine [36] | N/A | TCA cycle; Glutaminolysis | Essential for mammalian cell systems; Good TCA labeling | Poor coverage of carbohydrate metabolism |

*Relative precision scores normalized to [1,6-13C]glucose as reference (1.00) based on Crown et al. [35]

Tracer Mixtures and Parallel Labeling Strategies

For complex metabolic systems or when applying 2S-13C MFA to genome-scale models, single tracers often provide insufficient coverage of the entire metabolic network. In these cases, tracer mixtures or parallel labeling experiments are recommended:

Optimal Two-Tracer Combination: [1,6-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose in parallel experiments provide complementary information that significantly enhances flux precision across multiple pathways [35]. This combination improves the overall flux precision score by nearly 20-fold compared to the commonly used 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose mixture [35].

Glucose-Glutamine Combinations: For mammalian systems that utilize both glucose and glutamine, [1,2-13C]glucose combined with [U-13C]glutamine provides comprehensive coverage of central carbon metabolism [36].

Cost-Effective Mixtures: When tracer costs are a consideration, mixtures of labeled and natural abundance substrates can provide reasonable flux resolution at reduced expense. The commonly used 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose mixture remains a practical option despite not being optimal [35].

Experimental Protocol for Tracer Implementation

Tracer Selection Workflow

Define Metabolic System and Objectives

- Identify key pathways and fluxes of interest

- Determine system complexity (central metabolism vs. genome-scale)

- Assess available prior knowledge about the flux network

Select Computational Design Approach

Execute In Silico Tracer Evaluation

- Simulate labeling patterns for candidate tracers using EMU modeling

- Calculate precision scores for fluxes of interest

- Evaluate statistical identifiability of key fluxes

Select Optimal Tracer Strategy

- Choose single tracer if it provides sufficient flux resolution

- Opt for parallel labeling experiments if complementary information is needed

- Consider practical constraints (cost, availability)

Practical Implementation Guidelines

- Tracer Purity: Use tracers with minimum 99% isotopic purity to minimize natural abundance effects [35]

- Labeling Duration: Ensure isotopic steady-state is reached (typically 2-3 doubling times for microbial systems, longer for mammalian cells) [3]

- Mixture Precision: Precisely prepare tracer mixtures using analytical balances in a controlled environment

- Control Experiments: Include natural abundance controls to correct for background isotopic contributions

Integration with 2S-13C MFA for Genome-Scale Models

The 2S-13C MFA method specifically addresses the challenge of applying 13C labeling constraints to genome-scale metabolic models [4] [14]. When selecting tracers for 2S-13C MFA:

- Prioritize Network Coverage: Select tracers that label multiple pathway modules rather than optimizing for specific central metabolic fluxes

- Address Parallel Pathways: Genome-scale models contain numerous parallel and redundant pathways; choose tracers that can differentiate between these alternatives

- Consider Compartmentation: Eukaryotic systems require tracers that can illuminate compartment-specific metabolism

- Leverage Atom Mapping Databases: Use resources like MetRxn, which contains atom mapping information for over 27,000 reactions, to ensure proper simulation of labeling propagation in genome-scale models [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 13C Tracer Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1,6-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine | Create specific labeling patterns for flux observation | Purity (>99%); Chemical stability; Sterility |

| Analytical Standards | Natural abundance metabolite standards | Quantification and correction of natural isotope abundance | Certified reference materials; Purity verification |

| Mass Spectrometry Supplies | GC-MS columns (DB-5MS); LC-MS columns (HILIC) | Separation and detection of labeled metabolites | Column selectivity; MS compatibility |

| Software Platforms | Metran, INCA, 13CFLUX2 | Flux estimation from labeling data | Model compatibility; Computational efficiency |

| Isotope Mapping Databases | MetRxn, KEGG, MetaCyc | Atom transition information for reaction networks | Coverage of non-central metabolism reactions |

| tert-Butyl octaneperoxoate | tert-Butyl octaneperoxoate|CAS 13467-82-8 | tert-Butyl octaneperoxoate is a peroxy ester used as a radical initiator in polymerization research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Thulium sulfide (Tm2S3) | Thulium Sulfide (Tm2S3) | Rare Earth Sulfide | High-purity Thulium Sulfide (Tm2S3) for advanced materials science and infrared research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Optimal selection of 13C tracers is fundamental to successful metabolic flux analysis, particularly in the context of 2S-13C MFA for constraining genome-scale models. The recommended approach involves computational evaluation of tracer performance using metrics such as precision scores, with [1,6-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose emerging as optimal choices for many applications. For systems with limited prior knowledge, Robustified Experimental Design approaches provide protection against flux uncertainty. Implementation of these tracer selection strategies will enhance the information content of 13C-MFA studies and improve the reliability of flux estimates across metabolic networks.

Core Boundary Identification and Currency Metabolite Handling

In Two-Scale 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (2S-13C MFA), the accurate delineation of core metabolism and proper handling of currency metabolites are fundamental to implementing the bow tie approximation [11] [4]. This approximation posits that carbon flows predominantly from core to peripheral metabolism with minimal backflow, enabling researchers to apply strong flux constraints from 13C labeling data to genome-scale models [11]. The identification of core boundaries ensures that the metabolic network is partitioned correctly, while appropriate treatment of currency metabolites prevents the introduction of biases in flux estimation that could arise from non-carbon carrying molecules [11].

Theoretical Foundation

The Bow Tie Approximation in Metabolic Networks

Cellular metabolism universally exhibits a bow tie structure, where diverse nutrients are transformed through central carbon metabolism into twelve key precursor metabolites [11]. These precursors include glucose-6-phosphate, fructose-6-phosphate, ribose-5-phosphate, erythrose-4-phosphate, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, 3-phosphoglycerate, phosphoenolpyruvate, pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, 2-oxoglutarate, succinyl-CoA, and oxaloacetate [11]. This structural organization allows 2S-13C MFA to implement the bow tie approximation by setting upper bounds for reactions flowing into core metabolism to zero or biologically minimal values consistent with experimental data [11] [4].

The validity of this approximation is empirically supported by the demonstrated ability of core metabolism models to accurately explain isotopic labeling patterns in model organisms, and through successfully engineered strains with verified flux predictions [11]. The metric for validation is the sum of fluxes into the core, with zero representing a perfect bow tie structure [11].

The Role of Currency Metabolites

Currency metabolites participate in core reactions but do not contribute carbon atoms to measured metabolites in 13C labeling experiments [11]. These include energy carriers such as ATP, NADH, NADPH, and cofactors like Coenzyme A [11]. Proper identification and handling of these metabolites is crucial because:

- They participate in reactions throughout metabolism without carrying labeling information

- Their inclusion as carbon contributors would violate the bow tie principle

- They must be excluded from the set of boundary reactions subject to flux minimization [11]

Table 1: Common Currency Metabolites in 2S-13C MFA

| Metabolite Class | Examples | Primary Function | Handling in Core Boundary Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Carriers | ATP, ADP, AMP | Energy transfer | Excluded from boundary reaction set |

| Redox Carriers | NADH, NADPH, NAD+, NADP+ | Electron transfer | Excluded from boundary reaction set |

| Activation Carriers | CoA, Acetyl-CoA | Acyl group transfer | Excluded from boundary reaction set |