Directed Modulation of Metabolic Pathways: A Comprehensive Guide for Therapeutic Discovery and Optimization

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the directed modulation of metabolic pathways, a cutting-edge approach for therapeutic discovery and optimization.

Directed Modulation of Metabolic Pathways: A Comprehensive Guide for Therapeutic Discovery and Optimization

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the directed modulation of metabolic pathways, a cutting-edge approach for therapeutic discovery and optimization. It covers foundational principles, from the Warburg effect in cancer to the role of oncogenes and tumor suppressors in metabolic reprogramming. The article delves into core methodologies like directed evolution and metabolic control analysis (MCA) for pathway engineering, alongside advanced techniques such as LC-MS/NMR for metabolomics. It addresses key challenges including metabolic plasticity, data complexity, and analytical limitations, offering practical troubleshooting strategies. Furthermore, the guide outlines rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks, using real-world case studies like IDH1 inhibitors in leukemia to illustrate the successful translation of metabolic insights into clinical candidates. By integrating these concepts, this resource aims to equip scientists with the tools to systematically target metabolic vulnerabilities in disease.

Core Principles and Pathological Shifts in Cellular Metabolism

Metabolic reprogramming is now recognized as a fundamental hallmark of cancer, enabling tumor cells to meet increased energy demands, support rapid proliferation, and survive in challenging microenvironments [1]. This phenomenon represents the alteration of metabolic pathways and patterns by tumor cells to adapt to various environmental conditions and energy requirements, playing a pivotal role in tumor progression [1]. The most historically significant and well-documented manifestation of this reprogramming is the Warburg effect, first described by Otto Warburg a century ago, which refers to cancer cells' preference for aerobic glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation even when oxygen is available [2]. This metabolic reprogramming allows for rapid energy production and biomass synthesis, supporting uncontrolled growth and survival [2]. Modern research has revealed that oncogenes and tumor suppressors closely regulate these metabolic changes, with altered metabolism playing additional roles in therapy resistance, immune evasion, and tumor progression [2].

The Warburg Effect: A Century of Scientific Inquiry

Historical Context and Core Principles

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg made the seminal observation that tumor tissue slices consume large amounts of glucose and produce lactate even under aerobic conditions [1]. This phenomenon, known as aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect, established the foundation for tumor metabolism research [1]. The Warburg effect describes the propensity of tumor cells to preferentially metabolize glucose through glycolysis, rather than relying on oxidative phosphorylation, even in the presence of oxygen [3]. This unique metabolic phenotype empowers cancer cells to proliferate and invade indefinitely, inducing metabolic adaptations that provide a survival advantage in hypoxic and nutrient-poor environments [3].

Molecular Mechanisms and Regulation

The glycolytic pathway in cancer cells is regulated by various oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, including HIF-1, MYC, p53, and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [1]. Under hypoxic conditions commonly found in the tumor microenvironment, HIF-1α becomes upregulated, promoting the expression of glycolytic enzymes and glucose transporters in tumor cells, thereby enhancing glycolysis [1]. Simultaneously, MYC enhances the expression of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1), while also promoting glutamine metabolism, thereby linking glycolysis to anabolic biosynthesis [4]. This shift is further driven by the upregulation of key glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinase 2 (HK2), phosphofructokinase B3 (PFKFB3), and LDHA [4]. HK2 promotes glucose phosphorylation and mitochondrial binding, facilitating efficient ATP production; PFKFB3 boosts glycolytic flux under growth-promoting conditions; and LDHA converts pyruvate into lactate, maintaining NAD+ regeneration and allowing continuous glycolysis [4].

Table 1: Key Regulators of the Warburg Effect in Cancer Cells

| Regulator | Type | Primary Function in Warburg Effect | Therapeutic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α | Transcription Factor | Upregulates glycolytic enzymes & GLUT transporters under hypoxia | Target for overcoming hypoxia-induced chemoresistance |

| MYC | Oncogene | Enhances expression of LDHA, PFK1; promotes glutamine metabolism | Challenging to target directly; downstream pathways offer alternatives |

| p53 | Tumor Suppressor | Inhibits glycolysis; promotes oxidative phosphorylation | Frequently mutated in cancers, enabling glycolytic phenotype |

| PI3K/Akt/mTOR | Signaling Pathway | Increases glucose uptake and glycolytic flux | Multiple inhibitors in clinical development |

| HK2 | Metabolic Enzyme | Catalyzes first step of glycolysis; mitochondrial binding | Targeted by 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) in preclinical studies |

| LDHA | Metabolic Enzyme | Converts pyruvate to lactate, regenerating NAD+ | Inhibitors under investigation to disrupt lactate production |

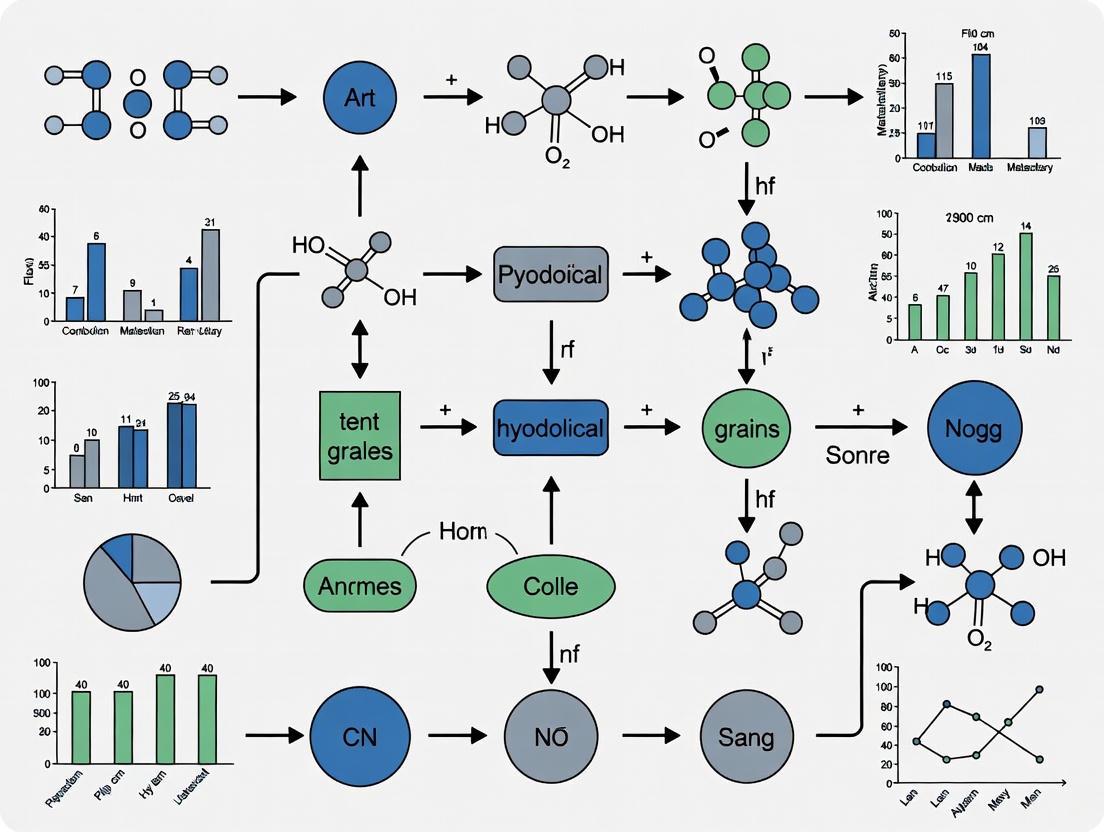

Diagram 1: Molecular regulation of the Warburg Effect and its impact on the tumor microenvironment.

Beyond Glycolysis: Modern Hallmarks of Metabolic Reprogramming

Mitochondrial Metabolism and Oxidative Phosphorylation

While the Warburg effect emphasizes glycolysis, mitochondrial function remains crucial in cancer metabolism. Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles essential for energy metabolism, apoptosis regulation, and cellular signal transduction [1]. Due to mutations in oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and metabolic enzymes, numerous mitochondrial pathways are altered in tumors, including the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid oxidation, glutamine metabolism, and one-carbon metabolism [1]. Recent studies suggest that mitochondrial OXPHOS is crucial for sustaining survival in subpopulations of cancer cells, particularly cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) and drug-resistant clones [4]. These cells exhibit a hybrid metabolic phenotype, characterized by the ability to switch between glycolysis and OXPHOS depending on nutrient availability and oxidative stress [4]. This metabolic plasticity enables more efficient ATP generation and supports the high energy demands of drug-resistant cells [4].

Glutamine Addiction and Amino Acid Metabolism

Beyond glucose metabolism, cancer cells exhibit high dependency on glutamine as a carbon and nitrogen source to fuel the TCA cycle, produce nucleotides, and maintain redox balance [4]. Glutaminase enzymes, particularly GLS1 and GLS2, catalyze the conversion of glutamine to glutamate, a critical step for anaplerosis and biosynthesis [4]. Overexpression of GLS1 has been observed in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) and is correlated with increased aggressiveness and chemoresistance [4]. Additionally, serine and glycine metabolism, which are intimately associated with the one-carbon metabolic network, play essential roles in supporting nucleotide biosynthesis, regulating methylation reactions, and maintaining redox homeostasis through the generation of NADPH and glutathione [4]. Key enzymes such as phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) and serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2) are frequently upregulated in cancers and function as metabolic checkpoints that sustain rapid proliferation of tumor cells [4].

Lipid Metabolism Reprogramming

Cancer progression is further supported by profound reprogramming of lipid metabolism. Tumor cells increase fatty acid uptake, synthesis, and oxidation to meet demands for membrane biosynthesis, energy generation, and signaling lipid production [4]. This metabolic adaptation provides essential components for membrane synthesis during rapid proliferation and serves as an alternative energy source when glucose utilization is compromised. The interconnection between lipid metabolism and other metabolic pathways creates a complex network that supports tumor survival under various environmental stresses.

Table 2: Modern Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming

| Metabolic Hallmark | Key Features | Associated Enzymes/Transporters | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Glycolysis | Lactate production despite oxygen; High glucose uptake | HK2, PFKFB3, LDHA, GLUT1 | Rapid ATP generation; Biosynthetic intermediates |

| Mitochondrial Reprogramming | TCA cycle alterations; OXPHOS in CSCs; ROS signaling | IDH, SDH, FH | Drug resistance; Maintenance of stemness |

| Glutamine Addiction | Anaplerosis; Nitrogen sourcing | GLS1, GLS2, ASCT2 | Nucleotide synthesis; Redox balance |

| Lipid Metabolism Dysregulation | Increased synthesis & uptake; Storage | FASN, ACC, CPT1 | Membrane formation; Signaling molecules |

| Amino Acid Dependency | Serine/glycine pathway; One-carbon metabolism | PHGDH, SHMT2, MTHFD | Purine synthesis; NADPH production |

The Tumor Microenvironment: Metabolic Crosstalk and Immune Evasion

The tumor microenvironment (TME) and tumor metabolic reprogramming are intricately interconnected [1]. The TME encompasses not only cancer cells but also fibroblasts, immune cells, vascular endothelial cells, stroma, and the extracellular matrix [1]. Interactions between tumor cells and these non-tumor cells govern tumor progression through the secretion of cytokines, metabolites, and other signaling molecules [1]. Metabolic reprogramming significantly impacts the TME through multiple mechanisms. The preference of tumor cells for aerobic glycolysis leads to lactate accumulation, resulting in a lowered pH within the TME [1]. This acidic microenvironment fosters tumor progression while inhibiting the activity of T cells and natural killer cells, facilitating immune evasion [1]. Moreover, the aggressive uptake of glutamine by tumor cells limits its availability to immune cells, thereby suppressing the antitumor immune response [1]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can also undergo metabolic reprogramming, secreting metabolites such as lactate and pyruvate that provide additional nutrient sources for tumor cells in a metabolic coupling relationship [1]. This metabolic crosstalk extends to immune cells as well, where tumor-associated macrophages often adopt an M2-like metabolic phenotype that aids tumor cells in evading immune surveillance [1].

Diagram 2: Metabolic crosstalk in the tumor microenvironment impacting immune function.

Methodologies for Studying Metabolic Reprogramming

Experimental Approaches and Workflows

Advancements in metabolic research have been driven by sophisticated methodological approaches that enable detailed investigation of metabolic pathways and fluxes. Isotope tracing has emerged as a powerful technique for tracking nutrient utilization through various metabolic pathways. Recent innovations include spatial metabolomics using isotopically labelled internal standards, which provides a cost-effective normalization strategy that addresses limitations of conventional methods and reveals hitherto unrecognized metabolic remodeling in pathological conditions [5]. For comprehensive analysis of metabolic heterogeneity, single-embryo metabolomics and transcriptomics methods have been developed that capture rapid, small-scale changes in metabolism and how they coordinate with gene expression [5]. These approaches are complemented by hyperpolarized C imaging for real-time assessment of metabolic fluxes in living systems [2].

Diagram 3: Core experimental workflow for studying metabolic reprogramming.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Metabolic Reprogramming Studies

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Research Application | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Nutrients | Metabolic flux analysis | Tracing carbon/nitrogen fate through pathways | U-13C-Glucose; 13C-Glutamine |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | Pathway perturbation | Assessing metabolic dependencies & vulnerabilities | 2-DG (glycolysis); CB-839 (glutaminase) |

| OXPHOS Modulators | Mitochondrial function assessment | Evaluating electron transport chain activity | Metformin; IACS-010759 |

| Genomic Tools | Genetic manipulation of metabolic genes | CRISPR/Cas9; siRNA for loss/gain-of-function studies | sgRNA libraries; siRNA pools |

| Metabolic Phenotyping Assays | Real-time metabolic measurements | Extracellular flux analysis; Metabolite consumption/secretion | Seahorse Assay Kits |

| Antibody Panels | Detection of metabolic proteins | Western blot; IHC for metabolic enzyme expression | Anti-HK2; Anti-LDHA; Anti-GLS1 |

| Ent-toddalolactone | Ent-toddalolactone, MF:C16H20O6, MW:308.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Schineolignin B | Schineolignin B, MF:C22H30O5, MW:374.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Therapeutic Targeting of Metabolic Reprogramming

Current Approaches and Clinical Translation

Targeting tumor metabolism has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy with several metabolic enzymes representing attractive targets [4]. Hexokinase 2 (HK2), lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), glutaminase (GLS1), and fatty acid synthase (FASN) are overexpressed in various cancers and have been implicated in poor prognosis and resistance phenotypes [4]. Inhibitors of these enzymes are currently under preclinical and clinical investigation, either as monotherapies or in combination with existing chemotherapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors [4]. Metabolic inhibitors targeting glycolysis, such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) and PFKFB3 inhibitors, are under investigation as potential sensitizers to chemotherapy [4]. For OXPHOS-dependent cancers, therapeutic strategies such as metformin, IACS-010759, and CPI-613 have shown promise in targeting mitochondrial metabolism and reducing cancer stem cell viability in preclinical models [4]. Dual targeting of glycolysis and OXPHOS may offer synergistic benefits by limiting metabolic compensation and plasticity [4].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Recent bibliometric analysis of the field from 2014-2023 has revealed rapidly evolving research clusters including tumor microenvironment, various cancers, pathological processes, major mechanisms, epigenetics, and mitochondria [1]. The top three frequently occurring keywords in current literature are glycolysis, tumor microenvironment, and mitochondria, indicating these areas as major foci of contemporary research [1]. Emerging frontiers include the application of single-cell and spatial metabolomics, which are improving our ability to map metabolic heterogeneity and guide precision therapies [4] [2]. The integration of metabolomic profiling with isotope tracing and single-cell analyses is enabling unprecedented resolution of metabolic heterogeneity in tumors [4]. Furthermore, the interactions between tumor metabolism, the immune system, and stromal cells represent an area of intense investigation as researchers seek to understand how to overcome resistance and enhance cancer treatment outcomes [2].

Table 4: Selected Metabolic Targets in Cancer Therapy Development

| Target | Therapeutic Agent | Mechanism of Action | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG) | Competitive inhibition of hexokinase | Preclinical/Clinical trials |

| Glutaminase | CB-839 (Telaglenastat) | Inhibits GLS1, blocking glutamine metabolism | Phase II trials |

| Mitochondrial Complex I | IACS-010759 | Inhibits OXPHOS in resistant cells | Early-phase trials |

| LDHA | GNE-140 | Inhibits lactate production | Preclinical development |

| PDHK | Dichloroacetate (DCA) | Shifts metabolism from glycolysis to OXPHOS | Clinical trials |

| PI3K/mTOR | Various inhibitors | Reduces glycolytic flux; Multiple signaling effects | FDA-approved (some agents) |

Metabolic reprogramming represents a core hallmark of cancer that extends far beyond the classical Warburg effect to encompass diverse adaptations in mitochondrial function, nutrient uptake, and biosynthetic pathway utilization. The intricate interplay between tumor cell metabolism and the tumor microenvironment creates dynamic ecosystems that influence disease progression, therapeutic response, and immune evasion. While significant progress has been made in understanding the molecular regulation and functional consequences of metabolic reprogramming, translating these insights into effective clinical strategies remains challenging due to metabolic plasticity and heterogeneity. Future advances will likely depend on innovative approaches that target multiple metabolic vulnerabilities simultaneously, incorporate sophisticated metabolic imaging and profiling technologies, and account for patient-specific metabolic dependencies. As we enter the second century since Warburg's seminal discovery, targeting cancer metabolism continues to offer promising avenues for improving cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes.

Metabolic pathways form the fundamental biochemical network that sustains life, providing energy and building blocks for cellular processes. In health, these pathways maintain precise homeostasis, but in disease, their deregulation drives pathogenesis. Glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), glutaminolysis, and lipid metabolism represent core interconnected metabolic routes that exhibit profound reprogramming in pathological conditions, particularly cancer and metabolic disorders. Understanding their intricate regulation and interactions provides a critical foundation for developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

The directed modulation of these pathways represents a promising frontier in biomedical research. Contemporary investigations focus on elucidating how oncogenes, tumor suppressors, and epigenetic mechanisms rewire cellular metabolism to support rapid growth and survival in hostile environments. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these four key pathways, their regulatory mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic targeting strategies to guide research and drug development efforts.

Pathway Fundamentals and Molecular Mechanisms

Glycolysis: Aerobic Glycolysis in Disease

Glycolysis involves the ten-step enzymatic conversion of glucose to pyruvate in the cytoplasm, generating ATP and NADH. A hallmark of cancer metabolism is the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis), where cells preferentially utilize glycolysis over OXPHOS even in oxygen-sufficient conditions [6] [7]. While inefficient in ATP yield (2 ATP/glucose vs. ~36 via OXPHOS), aerobic glycolysis supports rapid biomass generation by providing metabolic intermediates for nucleotide, amino acid, and lipid synthesis [6].

Key Regulatory Nodes:

- Hexokinase 2 (HK2): Often overexpressed in cancer, catalyzes the first committed step of glycolysis and binds to mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), evading feedback inhibition [7].

- Phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK1): Rate-limiting enzyme regulated by allosteric effectors (AMP, ADP, fructose-2,6-bisphosphate activate; ATP, citrate inhibit).

- Pyruvate Kinase M2 (PKM2): Isoform expressed in cancer cells with lower activity, creating a metabolic bottleneck that shunts intermediates into biosynthetic pathways.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase A (LDHA): Converts pyruvate to lactate, regenerating NAD+ for continued glycolysis and exporting lactic acid to acidify microenvironment [6].

Regulation occurs via oncogenic signaling (MYC, RAS), tumor suppressors (p53), and hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1α) that upregulate glucose transporters (GLUT1) and glycolytic enzymes [6]. HIF-1α activates transcription of multiple glycolytic genes under hypoxia, reinforcing glycolytic flux.

Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS): Mitochondrial Energy Production

OXPHOS occurs in the mitochondrial inner membrane, where electrons from NADH and FADH2 pass through four protein complexes (I-IV), creating a proton gradient that drives ATP synthesis via complex V (ATP synthase) [7]. Despite the Warburg effect, many cancers maintain functional OXPHOS, with heterogeneity in dependency across cancer types [6].

Mitochondrial Structural Organization:

- Outer Mitochondrial Membrane (OMM): Contains porin channels (VDAC) permeable to small molecules; upregulated TOMM20, TOMM34, and FUNDC2 in cancer support proliferation and invasion [7].

- Inner Mitochondrial Membrane (IMM): Folded into cristae to increase surface area; contains electron transport chain complexes; impermeable to ions, maintaining proton gradient.

- Matrix: Contains TCA cycle enzymes, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and ribosomes.

Cancer cells exhibit mtDNA mutations affecting OXPHOS efficiency and driving progression [7]. Mitochondrial dynamics (fission, fusion, mitophagy) enable adaptation to metabolic demands, with cristae density varying by energy requirements.

Glutaminolysis: Anaplerotic Fuel and Nitrogen Source

Glutaminolysis involves the conversion of glutamine to α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) to replenish TCA cycle intermediates (anaplerosis) [6]. Glutamine serves as a key nitrogen donor for nucleotide and amino acid biosynthesis, with cancer cells exhibiting marked glutamine dependency.

Catalytic Pathway:

- Glutaminase (GLS): Converts glutamine to glutamate; frequently upregulated in cancer.

- Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) or Transaminases: Convert glutamate to α-KG, entering TCA cycle.

Oncogenes like MYC transcriptionally upregulate GLS, enhancing glutaminolytic flux [6]. Glutamine-derived carbon can be oxidized through the TCA cycle or used in reductive carboxylation for lipid synthesis under hypoxia. The ammonia produced may contribute to metabolic signaling and microenvironment modulation.

Lipid Metabolism: Membrane Synthesis and Signaling

Reprogrammed lipid metabolism in cancer involves enhanced de novo lipogenesis and altered fatty acid oxidation, providing membrane components, energy storage, and signaling molecules [6].

Key Processes:

- De novo Lipogenesis: Upregulated ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and fatty acid synthase (FASN) in cancer, converting glucose-derived acetyl-CoA to saturated fatty acids.

- Fatty Acid Elongation and Desaturation: Stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) introduces double bonds to create monounsaturated fatty acids.

- Phospholipid Synthesis: Glycerol-3-phosphate pathway generates phosphatidylcholine and other membrane phospholipids.

- Cholesterol Synthesis: Mevalonate pathway upregulated in cancer, providing cholesterol for membranes and prenylation substrates.

- Fatty Acid Oxidation (FAO): Occurs in mitochondria, generating ATP; can be utilized by some cancers under nutrient stress.

Lipid droplets serve as energy reservoirs and protect against lipotoxicity. Cancer-associated fibroblasts can supply lipids to cancer cells via metabolic coupling.

Table 1: Core Metabolic Pathways in Health and Disease

| Pathway | Primary Function | Key Regulatory Enzymes | Dysregulation in Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | Glucose catabolism to pyruvate; ATP generation | HK2, PFK1, PKM2, LDHA | Warburg effect: Enhanced flux even with oxygen; HK2, PKM2 overexpression |

| OXPHOS | ATP generation via electron transport chain | Complex I-V, ATP synthase | mtDNA mutations; Altered complex activity; Heterogeneous dependency in cancers |

| Glutaminolysis | Glutamine conversion to TCA intermediates | Glutaminase (GLS), Transaminases | GLS overexpression; Enhanced anaplerosis in proliferating cells |

| Lipid Metabolism | Lipid synthesis, storage, oxidation | ACLY, ACC, FASN, SCD | Enhanced de novo lipogenesis; Altered fatty acid oxidation |

Metabolic Cross-Talk and Signaling Networks

Metabolic pathways do not operate in isolation but form an integrated network where intermediates from one pathway regulate or feed into others. The TCA cycle serves as the central metabolic hub, connecting carbohydrate, amino acid, and lipid metabolism through common intermediates.

Critical Nodal Points:

- Citrate: Exported from mitochondria and cleaved by ACLY to oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA for fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis.

- Acetyl-CoA: Serves as substrate for lipid synthesis and histone acetylation, linking metabolism to epigenetics.

- α-Ketoglutarate (α-KG): Connects glutaminolysis to TCA cycle; regulates dioxygenases involved in epigenetics (TET proteins, histone demethylases) and hypoxia signaling.

- Succinate: Accumulation inhibits HIF-α prolyl hydroxylases, stabilizing HIF-1α even under normoxia [6].

- Oxaloacetate: Can undergo transamination to aspartate for nucleotide synthesis.

Oncogenic Signaling Integration:

- PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway: Akt promotes glucose uptake and activates mTORC1, which stimulates HIF-1α and SREBP to enhance glycolysis and lipogenesis [7].

- MYC: Transcriptionally upregulates glycolytic enzymes, GLUT1, and glutaminase, coordinating multiple metabolic pathways.

- HIF-1α: Activated under hypoxia, promotes glycolytic gene expression and inhibits PDK1, redirecting flux from mitochondria.

- AMPK: Energy sensor activated by ATP depletion, inhibits anabolic processes (mTORC1, lipogenesis) and promotes catabolism (FAO).

The serine-glycine-one-carbon (SGOC) network branches from glycolysis at 3-phosphoglycerate, generating one-carbon units for nucleotide synthesis and methylation reactions. Key enzymes include phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), frequently amplified in cancer.

Diagram: Metabolic Pathway Interconnections - Core metabolic pathways and their integration, showing glycolytic (yellow), glutaminolytic (blue), mitochondrial (red), and anabolic (green) processes.

Metabolic Dysregulation in Disease States

Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming

Cancer cells extensively reprogram metabolism to support uncontrolled proliferation, survival, and metastasis [6]. Key alterations include:

- Enhanced Glucose Uptake and Glycolysis: Mediated by HIF-1α and oncogene-driven overexpression of GLUT transporters and glycolytic enzymes.

- Glutamine Addiction: Many cancers require glutamine for anaplerosis, biosynthesis, and redox homeostasis.

- Lipogenic Switch: Elevated de novo lipogenesis even in lipid-rich environments.

- Metabolic Heterogeneity: Subpopulations within tumors exhibit different metabolic dependencies, with some utilizing OXPHOS while others rely on glycolysis.

- Microenvironment Interactions: Acidosis from lactate secretion remodels extracellular matrix and inhibits immune cell function.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) creates selective pressures that shape metabolic phenotypes. Hypoxia stabilizes HIF-1α, driving angiogenesis and metabolic adaptation. Cancer-associated fibroblasts undergo metabolic reprogramming (aerobic glycolysis) and secrete metabolites (lactate, ketones) that can be utilized by cancer cells.

Metabolic Syndrome and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Beyond cancer, metabolic pathway dysregulation occurs in diverse pathologies:

- Metabolic Syndrome (MetS): Characterized by insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, with oxidative stress as a pathogenic core. The thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP)/thioredoxin system regulates redox balance, with TXNIP overexpression linked to impaired glucose metabolism and β-cell apoptosis [8].

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: Impaired glucose metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction accelerate disease progression. Neurons exhibit metabolic inflexibility with defective OXPHOS.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Host-microbiome metabolic cross-talk disruption involves altered NAD, amino acid, one-carbon, and phospholipid metabolism [9]. Elevated tryptophan catabolism depletes circulating tryptophan, impairing NAD biosynthesis.

Experimental Methodologies and Research Tools

Metabolic Flux Analysis

13C/15N Isotope Tracing: Cells or organisms are fed 13C-labeled nutrients (e.g., [U-13C]-glucose, [5-13C]-glutamine), and isotopic enrichment in metabolites is quantified via mass spectrometry to determine pathway fluxes.

Protocol Summary:

- Cell Culture with Tracer: Replace medium with identical composition containing 13C-labeled substrate.

- Metabolite Extraction: At designated times, wash cells with saline and extract metabolites with cold methanol/acetonitrile/water.

- LC-MS Analysis: Separate metabolites via hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and analyze with high-resolution mass spectrometer.

- Data Processing: Correct for natural isotope abundance and calculate isotopologue distributions.

- Flux Estimation: Use computational modeling (e.g., Metran, INCA) to infer intracellular fluxes from labeling patterns.

Key Measurements:

- Glycolytic Flux: [U-13C]-glucose → M+3 pyruvate/lactate

- Pentose Phosphate Pathway: Ratio of M+2/M+1 lactate from [1,2-13C]-glucose

- TCA Cycle Flux: 13C-glutamine → M+4/M+3 citrate, M+2 succinate/fumarate/malate

- Anaplerosis: Ratio of M+3 pyruvate carboxylase vs. M+2 pyruvate dehydrogenase-derived oxaloacetate

Mitochondrial Function Assessment

Seahorse XF Analyzer Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in XF plates (optimal density determined empirically); incubate 12-24 hours.

- Media Exchange: Replace with XF assay medium (unbuffered DMEM with glucose, glutamine, pyruvate); incubate 1 hour at 37°C without CO2.

- Compound Loading: Inject port A: oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor); port B: FCCP (mitochondrial uncoupler); port C: rotenone/antimycin A (complex I/III inhibitors).

- Real-Time Measurement: Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) monitored following each injection.

- Parameter Calculation:

- Basal respiration = Last OCR before oligomycin - Non-mitochondrial respiration

- ATP-linked respiration = Last OCR before oligomycin - Minimum OCR after oligomycin

- Maximal respiration = Maximum OCR after FCCP - Non-mitochondrial respiration

- Spare capacity = Maximal respiration - Basal respiration

- Glycolysis = Last ECAR before oligomycin - ECAR after rotenone/antimycin

Metabolomic Profiling

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Rapid quenching of metabolism (liquid N2), metabolite extraction (methanol:acetonitrile:water), protein removal, concentration normalization.

- Chromatographic Separation:

- HILIC: Polar metabolites (glycolytic intermediates, TCA cycle acids)

- Reversed-Phase (RP): Lipids, hydrophobic compounds

- Mass Spectrometry:

- High-Resolution MS: Orbitrap or TOF for untargeted profiling, accurate mass

- Tandem MS/MS: MRM for targeted quantification

- Data Analysis:

- Peak Picking/Alignment: XCMS, Progenesis QI

- Identification: MS/MS matching to databases (HMDB, METLIN)

- Statistical Analysis: Multivariate methods (PCA, PLS-DA), pathway enrichment

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Inhibitors | 2-DG (glycolysis), Oligomycin (OXPHOS), BPTES/CB-839 (glutaminase), Orlistat (FASN) | Pathway perturbation studies; Synthetic lethality screening | Dose-response essential; Off-target effects validation required |

| Isotopic Tracers | [U-13C]-Glucose, [5-13C]-Glutamine, 13C-Palmitate, 15N-Glutamine | Metabolic flux analysis; Pathway contribution quantification | Purity verification; Appropriate labeling position selection |

| Fluorescent Probes | TMRE/MitoTracker (mitochondrial membrane potential), 2-NBDG (glucose uptake), MitoSOX (mitochondrial ROS) | Real-time metabolic monitoring; Subcellular localization | Potential toxicity; Proper controls for quantification |

| Bioenergetic Assays | Seahorse XF Reagents (oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone/antimycin), ATP Luminescence | Mitochondrial function; Glycolytic capacity | Cell density optimization; Background correction |

| Antibodies | Anti-HK2, Anti-GLS, Anti-LDHA, Anti-phospho-AMPK/ACC | Western blot validation of metabolic protein expression | Phospho-specific antibodies require careful handling |

Computational Modeling Approaches

Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling:

- Genome-Scale Models (GEMs): Reconstruction of metabolic network from genomic data; flux balance analysis (FBA) predicts optimal flux distributions.

- Context-Specific Modeling: Algorithms (GIMME, iMAT, FASTCORE) integrate transcriptomic/proteomic data to construct tissue/cell-type specific models.

- Microbiome Modeling: Tools like MicrobiomeGS2 and BacArena model metabolic interactions in microbial communities and host-microbe exchanges [9].

Application Example: IBD host-microbiome modeling identified concomitant changes in NAD, amino acid, one-carbon, and phospholipid metabolism during inflammation, predicting dietary interventions to restore metabolic homeostasis [9].

Therapeutic Targeting and Research Perspectives

Metabolic Pathway Inhibitors

Therapeutic targeting of metabolic pathways exploits cancer-specific dependencies while sparing normal tissues [6].

Glycolysis Targeting:

- GLUT Inhibitors (WZB117): Reduce glucose uptake; preclinical efficacy in SDH-deficient tumors [6].

- Hexokinase Inhibitors (2-DG, Lonidamine): 2-DG competes with glucose; clinical trials limited by toxicity.

- LDHA Inhibitors (GSK2837808A): Suppress lactate production; may enhance oxidative metabolism.

- PKM2 Activators (TEPP-46): Promote glycolytic efficiency but reduce metabolic intermediates for biosynthesis.

Mitochondrial Metabolism Targeting:

- OXPHOS Inhibitors (Metformin, Phenformin): Complex I inhibitors; metformin used for diabetes with potential anticancer effects.

- GLS Inhibitors (CB-839, BPTES): Allosteric inhibitors; clinical trials in RAS-driven and SDH-deficient cancers [6].

- Fatty Acid Metabolism Modulators:

- FASN Inhibitors (TVB-2640): Impairs de novo lipogenesis; in clinical trials.

- CPT1 Inhibitors (Etomoxir): Blocks fatty acid oxidation; potential cardiotoxicity concerns.

Combination Strategies: Targeting multiple pathways addresses metabolic plasticity and compensatory mechanisms. Glycolysis + OXPHOS inhibition may more effectively eliminate bioenergetic capacity.

Synthetic Lethality Approaches

Metabolic synthetic lethality exploits context-specific vulnerabilities created by mutations [6].

TCA Cycle Enzyme Deficiencies:

- SDH Mutations: Accumulation of succinate stabilizes HIF-1α; increases glycolysis dependency; vulnerable to GLUT1 inhibition and glutaminase inhibition [6].

- FH Mutations: Fumarate accumulation upregulates heme synthesis; targetable with heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) inhibitors [6].

- IDH Mutations: Neomorphic enzyme produces 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), altering epigenetics; IDH inhibitors (ivosidenib) approved for leukemia.

Emerging Research Directions

Single-Cell Metabolism: Technologies like SCI-LITE enable high-resolution mapping of mtDNA heterogeneity and metabolic states [7].

Spatial Metabolomics: Integrating PET imaging, respirometry, and electron microscopy reveals mitochondrial network organization in tissue context [7].

Metabolic Immunomodulation: Mitochondria impact immune responses by modulating T-cell survival/function, macrophage polarization, and neutrophil activation [7].

AI-Driven Formulation: Platforms like FormulationDT use machine learning to design optimal formulation strategies for metabolic drugs, addressing developability challenges [10].

Natural Product Discovery: Dual-targeting natural compounds that simultaneously modulate GLP-1 signaling and TXNIP-thioredoxin antioxidant pathways offer multi-target approaches for metabolic syndrome [8].

Diagram: Metabolic Targeting Strategies - Approaches for therapeutic intervention in dysregulated metabolic pathways, including specific enzyme inhibitors and genetic context-dependent synthetic lethality.

The directed modulation of glycolysis, OXPHOS, glutaminolysis, and lipid metabolism represents a promising therapeutic strategy with applications in oncology, metabolic diseases, and beyond. Successful targeting requires understanding pathway interdependencies, regulatory networks, and context-specific vulnerabilities. Future research should prioritize unraveling metabolic heterogeneity, developing selective inhibitors with favorable therapeutic indices, and identifying robust biomarkers for patient stratification. Integrating cutting-edge technologies in metabolomics, metabolic imaging, single-cell analysis, and computational modeling will accelerate the translation of metabolic insights into precision medicine approaches that meaningfully impact patient care.

Cancer is a genetic disease characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation, driven primarily by the activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. These molecular regulators form complex signaling networks that orchestrate fundamental cellular processes, including metabolism, cell cycle progression, and survival. The directed modulation of metabolic pathways has emerged as a critical research focus in oncology, as cancer cells must rewire their metabolic programming to support rapid proliferation, biomass accumulation, and survival in challenging microenvironments. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of four pivotal molecular regulators in cancer—the MYC and RAS oncogenes, and the TP53 and PTEN tumor suppressors. We explore their mechanisms of action, interplay with metabolic pathways, and experimental approaches for their investigation, framing this knowledge within the context of therapeutic development for cancer researchers and drug development professionals.

The metabolic landscape of cancer cells is fundamentally different from that of normal cells, characterized by increased glucose uptake, enhanced glycolysis, elevated glutaminolysis, and augmented biosynthesis of nucleotides, lipids, and proteins. Oncogenes and tumor suppressors sit at the apex of the signaling cascades that control these metabolic shifts. Understanding how these molecular regulators influence metabolic pathways provides not only fundamental insights into cancer biology but also reveals potential vulnerabilities that can be therapeutically exploited.

MYC: Master Regulator of Transcription and Metabolism

Molecular Structure and Regulation

MYC is a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper (bHLH-ZIP) transcription factor that serves as a universal transcription amplifier. The MYC protein contains several structurally and functionally distinct domains: an N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) with conserved Myc Boxes (MB I-IV), and a C-terminal domain comprising the bHLH-ZIP motif that facilitates dimerization with its partner MAX and subsequent DNA binding [11]. MYC's transcriptional activity is tightly regulated at multiple levels, with the protein having an exceptionally short half-life of approximately 20-30 minutes due to rapid proteasomal degradation [12]. This precise regulation is critical as minor perturbations in MYC expression can drive tumorigenesis.

Key regulatory mechanisms include phosphorylation at critical residues—Ser-62 phosphorylation by ERK stabilizes MYC, while subsequent Thr-58 phosphorylation by GSK-3β targets it for degradation [12]. The Ras/Raf signaling cascade enhances MYC stability through ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-62, while PI3K/Akt signaling stabilizes MYC by inhibiting GSK-3β [12]. MYC is also regulated by BRD4, which directly phosphorylates MYC at Thr-58, leading to its destabilization [12]. In normal cells, MYC expression is transiently induced by mitogenic signals, but in cancer, various mechanisms including gene amplification, chromosomal translocations, and super-enhancer activation lead to its constitutive overexpression [12].

Role in Transcriptional Amplification and Metabolic Reprogramming

MYC does not function as a classic transcription factor that activates a specific set of target genes. Instead, it acts as a global amplifier of transcription, increasing the expression of essentially all active genes in a cell [11]. This transcriptional amplification effect has profound implications for cellular metabolism, as MYC boosts the expression of genes involved in virtually every aspect of cell growth and proliferation.

Metabolically, MYC promotes glycolysis by upregulating glucose transporters (GLUT1) and multiple glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinase 2 (HK2), enolase 1 (ENO1), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) [13]. MYC also drives glutaminolysis by increasing the expression of glutamine transporters and enzymes such as glutaminase (GLS), facilitating nitrogen and carbon sourcing for biosynthetic pathways [13]. Furthermore, MYC enhances ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis, supporting the increased translational capacity required for rapid cell growth [11]. Through these coordinated actions, MYC orchestrates a metabolic program that provides both the energy and molecular building blocks necessary for sustained proliferation.

Experimental Approaches for MYC Investigation

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for MYC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| MYC Pathway Inhibitors | JQ1, I-BET151 (BRD4 inhibitors); 10058-F4 (MYC-MAX dimerization inhibitor) | Disrupt MYC transcription or MYC-MAX dimerization; evaluate pathway dependency |

| Genetic Tools | shRNA/siRNA vectors; CRISPR/Cas9 systems for MYC knockout; Doxycycline-inducible MYC expression constructs | Modulate MYC expression to assess functional consequences |

| Protein Interaction Assays | Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) kits; MAX fusion proteins; BioID proximity labeling | Identify MYC-interacting partners and complexes |

| Transcriptional Profiling | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays; RNA-Seq; GRO-Seq | Map MYC genomic binding sites and quantify transcriptional outputs |

| Metabolic Assays | Seahorse XF Analyzer kits; Stable isotope tracing (e.g., 13C-glucose, 15N-glutamine); ATP/NADH/NADPH quantification | Measure glycolytic flux, mitochondrial respiration, and nutrient utilization |

Protocol 1: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for MYC DNA-Binding Analysis

- Cell Fixation: Grow cells to 70-80% confluence and crosslink proteins to DNA using 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Quench with 125mM glycine.

- Cell Lysis and Sonication: Lyse cells in ChIP lysis buffer and sonicate to shear DNA to fragments of 200-500 bp. Confirm fragment size by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Immunoprecipitation: Pre-clear lysate with protein A/G beads. Incubate supernatant with anti-MYC antibody or species-matched IgG control overnight at 4°C with rotation.

- Bead Capture and Washes: Add protein A/G beads and incubate for 2 hours. Wash beads sequentially with low salt, high salt, LiCl, and TE buffers.

- Crosslink Reversal and DNA Purification: Elute complexes and reverse crosslinks by incubating at 65°C overnight with 200mM NaCl. Treat with Proteinase K, then purify DNA using spin columns.

- Analysis: Quantify MYC-enriched DNA by qPCR with primers for known MYC target gene promoters (e.g., CAD, NCL) or by ChIP-seq for genome-wide binding analysis.

RAS: Signaling Hub and Metabolic Rewirer

RAS Isoforms and Activation Mechanisms

The RAS family of small GTPases (KRAS, NRAS, HRAS) operates as critical signaling nodes that transduce signals from activated cell surface receptors to intracellular pathways. RAS proteins cycle between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states, a process regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) [14]. Oncogenic mutations—most commonly at codons 12, 13, and 61—lock RAS in its active GTP-bound state, leading to constitutive signaling output [13]. The mutation frequency and substitution patterns vary significantly across cancer types, with KRAS-G12D being dominant in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and KRAS-G12C prevalent in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) [13].

Beyond its role in proliferative signaling, oncogenic RAS alters the mechanical properties of cells by reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton and increasing actomyosin contractility through RhoA-ROCK signaling [14]. RAS transformation also changes cell-ECM interactions by impacting integrin-based focal adhesions, which influences mechanosensing and cell migration [14]. These mechanical changes contribute to large-scale tissue deformations and loss of epithelial architecture during tumor progression.

Metabolic Pathways Regulated by RAS

Oncogenic RAS orchestrates comprehensive metabolic reprogramming to support tumor growth. The key metabolic pathways regulated by RAS include:

Glycolytic Flux Enhancement: Mutant KRAS upregulates glucose transporter GLUT1 and multiple glycolytic enzymes, including HK1, HK2, PFK1, and LDHA, driving glucose uptake and glycolytic flux even in the presence of oxygen (Warburg effect) [13]. This glycolytic shift provides both ATP and metabolic intermediates for biosynthetic pathways.

Glutaminolysis Promotion: KRAS-mutant cells display increased dependence on glutamine metabolism. KRAS upregulates enzymes involved in glutaminolysis, directing glutamine-derived carbon into the TCA cycle for anaplerosis and lipid biosynthesis [13].

Macropinocytosis Activation: RAS-transformed cells can utilize macropinocytosis to internalize extracellular proteins, which are degraded in lysosomes to generate amino acids and other nutrients that support metabolic homeostasis under nutrient-poor conditions [13].

Redox Homeostasis Maintenance: RAS signaling supports antioxidant production through multiple mechanisms, including increased NADPH generation via the pentose phosphate pathway and upregulation of the xCT cysteine-glutamate antiporter, enhancing glutathione synthesis and protection against oxidative stress [13].

Experimental Approaches for RAS Investigation

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for RAS Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| RAS Inhibitors | G12C-specific inhibitors (Sotorasib, Adagrasib); Farnesyltransferase inhibitors; MEK inhibitors (Trametinib) | Target specific RAS mutants or downstream signaling pathways |

| Activity Assays | RAF-RBD pull-down assays; RAS activation ELISA kits; FRET-based biosensors | Measure GTP-bound active RAS levels in cell lysates or live cells |

| Genetic Models | Inducible RAS expression systems (e.g., HRASG12V); Isogenic cell lines with RAS mutations; CRISPR-mediated endogenous tagging | Enable controlled RAS expression or study specific mutant effects |

| Metabolic Probes | 2-NBDG (glucose uptake); TMRE (mitochondrial membrane potential); C11-BODIPY581/591 (lipid peroxidation/ferroptosis) | Visualize and quantify metabolic parameters in live cells |

| Mechanical Property Assays | Atomic force microscopy (AFM); Traction force microscopy; Microrheology setups | Measure cell stiffness, contractility, and force generation |

Protocol 2: RAF-RBD Pull-Down Assay for RAS-GTP Measurement

- Cell Lysis: Culture RAS-transformed cells to 70-80% confluence. Lyse in Mg2+-containing lysis buffer (25mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL, 10mM MgCl2, 1mM EDTA, 2% glycerol) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Clarification: Clear lysates by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Reserve an aliquot of supernatant for total RAS measurement.

- GST-RAF-RBD Bead Preparation: Express and purify GST-tagged RAF Ras-binding domain (RBD) from E. coli. Bind to glutathione-sepharose beads (10μg GST-RAF-RBD per 20μl bead slurry).

- Pull-Down: Incubate cell lysates with GST-RAF-RBD beads for 30-45 minutes at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads three times with lysis buffer. Elute bound proteins with 2× Laemmli buffer by boiling for 5 minutes.

- Analysis: Detect active GTP-bound RAS and total RAS in input samples by Western blotting using pan-RAS or isoform-specific antibodies. Quantify band intensities to calculate the ratio of RAS-GTP to total RAS.

TP53: Guardian of the Genome and Metabolic Gatekeeper

Molecular Functions and Regulatory Mechanisms

TP53 is a tetrameric transcription factor that serves as a critical tumor suppressor, responding to diverse cellular stresses including DNA damage, oncogene activation, hypoxia, and nutrient deprivation [15] [16]. In unstressed cells, p53 levels are kept low through continuous ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation mediated by its key negative regulators MDM2 and MDMX [16]. Upon stress detection, post-translational modifications (phosphorylation, acetylation) stabilize p53 and enhance its DNA-binding capacity, enabling transcriptional regulation of hundreds of target genes [16].

TP53 activation can lead to multiple cellular outcomes depending on context and signal intensity, including cell cycle arrest, senescence, apoptosis, DNA repair, and metabolic adaptations [15]. The decision between these fates is influenced by the type and duration of stress, cell type, and microenvironmental factors. TP53's role in maintaining genomic stability is so fundamental that it has been dubbed the "guardian of the genome" [17]. TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human cancer, with approximately 50% of all tumors harboring TP53 mutations [16] [17]. These mutations not only abolish p53's tumor suppressor functions but often confer gain-of-function properties that promote tumor progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance.

Metabolic Regulation by TP53

TP53 plays a complex role in cellular metabolism, acting as a critical gatekeeper that suppresses metabolic pathways supporting tumor growth while promoting those that maintain metabolic homeostasis:

Glycolysis Suppression: TP53 transcriptionally represses glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4, and activates synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase 2 (SCO2), which enhances mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation while dampening glycolysis [16].

Antioxidant Response Enhancement: TP53 upregulates genes involved in antioxidant defense, including GPX1 and SESN1/2, reducing intracellular ROS levels and protecting against oxidative damage [16].

Glutamine Metabolism Regulation: TP53 limits glutamine utilization by repressing glutaminase 2 (GLS2) expression, thereby restricting anaplerotic flux through the TCA cycle [16].

Lipid Metabolism Control: TP53 activates genes involved in fatty acid oxidation (e.g., GAMT) while inhibiting de novo lipogenesis, shifting energy production toward more efficient mitochondrial pathways [16].

Ferroptosis Regulation: TP53 modulates susceptibility to ferroptosis—an iron-dependent form of cell death—through transcriptional regulation of SLC7A11, a component of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system [16].

Experimental Approaches for TP53 Investigation

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for TP53 Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| p53 Activators | Nutlin-3 (MDM2 antagonist); RITA; PRIMA-1MET (reactivates mutant p53) | Stabilize p53 or restore function to mutant p53 |

| p53 Reporter Systems | Luciferase reporters with p53 response elements (e.g., from p21/CDKN1A promoter); GFP-p53 localization constructs | Monitor p53 transcriptional activity and cellular localization |

| DNA Damage Inducers | Doxorubicin; Etoposide; UV irradiation; Nutlin-3 | Activate p53 signaling pathways for functional studies |

| Apoptosis/Senescence Assays Annexin V/propidium iodide staining; SA-β-Galactosidase kit; Caspase-3/7 activity assays | Quantify p53-mediated cell fate decisions | |

| Genomic Tools | TP53 knockout cell lines; p53 R273H knock-in mutants; p53 tetramerization domain mutants | Study p53 structure-function relationships and mutant-specific effects |

Protocol 3: Analysis of p53-Mediated Cell Fate Decisions After DNA Damage

- Treatment Optimization: Seed cells at appropriate density and treat with DNA damaging agents (e.g., 0.5μM doxorubicin for 24 hours) or MDM2 antagonist (e.g., 10μM Nutlin-3 for 24 hours) to activate p53.

- Cell Cycle Analysis: Harvest cells by trypsinization, wash with PBS, and fix in 70% ethanol overnight at -20°C. Stain with propidium iodide (50μg/mL) containing RNase A (100μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Analyze DNA content by flow cytometry to quantify G1, S, and G2/M populations.

- Senescence Detection: Fix cells with 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde for 5 minutes at room temperature. Wash and incubate with fresh SA-β-gal staining solution (1mg/mL X-gal, 40mM citric acid/Na phosphate buffer pH 6.0, 5mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5mM potassium ferricyanide, 150mM NaCl, 2mM MgCl2) overnight at 37°C without CO2. Quantify blue-stained senescent cells by bright-field microscopy.

- Apoptosis Measurement: Harvest cells and stain with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide using commercial apoptosis detection kit according to manufacturer's instructions. Analyze by flow cytometry within 1 hour to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V-/PI+) populations.

- Western Blot Validation: Confirm p53 activation and target gene expression by Western blotting for p53, p21, PUMA, and cleaved caspase-3.

PTEN: Phosphatase and Genome Guardian

Molecular Functions and Regulatory Mechanisms

PTEN (Phosphatase and TENsin homolog) is a critical tumor suppressor with both lipid phosphatase and protein phosphatase activities. Its primary tumor suppressor function involves dephosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) to phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2), thereby negatively regulating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [18]. This activity places PTEN as a central negative regulator of a major proliferative and survival signaling cascade. PTEN also possesses phosphatase-independent functions, including roles in maintaining chromosomal stability through regulation of DNA repair processes and as a scaffold protein that modulates various cellular signaling complexes [18].

PTEN activity is regulated through multiple mechanisms, including post-translational modifications (phosphorylation, ubiquitination, oxidation), protein-protein interactions, and subcellular localization [18]. Recent discoveries have revealed the existence of distinct PTEN isoforms and the ability of PTEN to form dimers, adding new layers of complexity to its regulation and function [18]. Even subtle decreases in PTEN expression or activity can promote cancer susceptibility and progression, highlighting its importance as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor.

Metabolic Regulation by PTEN

Through its negative regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, PTEN exerts profound effects on cellular metabolism:

Glycolysis Restraint: By opposing PI3K/AKT signaling, PTEN limits AKT-mediated membrane translocation of glucose transporters and glycolytic enzyme activation, constraining glycolytic flux [18].

Protein Synthesis Inhibition: PTEN antagonizes AKT-mediated activation of mTORC1 signaling, thereby reducing cap-dependent translation and protein synthesis [18].

Lipid Metabolism Regulation: PTEN negatively regulates sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) activity through AKT-dependent and independent mechanisms, limiting de novo lipogenesis [18].

Growth Factor Signaling Attenuation: By converting PIP3 to PIP2, PTEN terminates PI3K-derived signals that promote anabolic metabolism in response to growth factor stimulation [18].

Interplay and Therapeutic Implications

Network Interactions Among Molecular Regulators

The oncogenes and tumor suppressors discussed do not function in isolation but rather form an integrated regulatory network with extensive cross-talk and feedback mechanisms. Key interactions include:

TP53-PTEN Axis: TP53 can transcriptionally activate PTEN expression, creating a cooperative tumor suppressor network that enhances suppression of the PI3K/AKT pathway [16] [18]. Conversely, PTEN loss can attenuate p53 function through various mechanisms, illustrating bidirectional regulation.

RAS-MYC Cooperation: Oncogenic RAS signaling stabilizes MYC protein through ERK-mediated phosphorylation, while MYC enhances the expression of multiple components of the RAS signaling cascade, creating a powerful oncogenic feed-forward loop [12].

TP53 as a Counterbalance to MYC: TP53 activation serves as a critical failsafe mechanism against MYC-driven transformation, inducing apoptosis or senescence in cells with excessive MYC activity [12] [16]. Loss of TP53 function is often required for MYC-driven tumor progression.

Metabolic Integration: These molecular regulators converge on metabolic control, with MYC and RAS promoting anabolic metabolism while TP53 and PTEN restrain it. The balance between these opposing forces determines the metabolic state of the cell.

Figure 1: Regulatory Network of Key Molecular Regulators in Cancer Metabolism

Therapeutic Opportunities and Challenges

The intricate relationships between these molecular regulators present both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention:

Synthetic Lethality Approaches: Tumors with specific genetic alterations (e.g., KRAS mutations) may display unique dependencies that can be therapeutically targeted. For instance, KRAS-mutant tumors show increased sensitivity to inhibitors of mitochondrial translation and oxidative phosphorylation [13].

Metabolic Vulnerabilities: Oncogene-driven metabolic reprogramming creates targetable vulnerabilities. MYC-driven tumors demonstrate heightened sensitivity to inhibitors of nucleotide synthesis and RNA metabolism, while RAS-mutant cancers may be vulnerable to disruption of glutamine metabolism or macropinocytosis [13].

Restoration of Tumor Suppressor Function: Reactivating wild-type p53 function with MDM2 antagonists or restoring function to mutant p53 represents a promising therapeutic strategy currently under clinical investigation [16].

Combination Therapies: Given the network nature of cancer signaling, effective treatments will likely require rational combinations that target multiple nodes simultaneously. For example, combining KRASG12C inhibitors with agents that target adaptive resistance mechanisms may enhance therapeutic efficacy [13].

Table 4: Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressors

| Molecular Target | Therapeutic Approach | Example Agents | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant KRAS | Direct GTP-binding pocket inhibitors; Synthetic lethal combinations | Sotorasib (G12C); Adagrasib (G12C) | Rapid acquired resistance; Tissue-specific efficacy |

| MYC | Indirect targeting via transcriptional/translational control; BRD4 inhibition | JQ1; OTX015; Omomyc cell-penetrating peptide | Lack of direct binding pockets; Therapeutic index concerns |

| Mutant p53 | Reactivation of wild-type conformation; Targeting mutant p53 stability | APR-246; COTI-2; PC14586 | Structural complexity; Mutation heterogeneity |

| PTEN loss | PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibition; PARP inhibition in PTEN-deficient tumors | Ipatasertib (AKT inhibitor); Alpelisib (PI3Kα inhibitor) | Pathway redundancy; Toxicity management |

| RAS/MYC/TP53 network | Rational combination therapies | MEK inhibitors + MDM2 antagonists; CDK4/6 inhibitors + BET inhibitors | Toxicity management; Identifying predictive biomarkers |

The molecular regulators MYC, RAS, TP53, and PTEN form an integrated network that controls critical cellular decisions regarding growth, proliferation, and metabolism. Their interplay creates a delicate balance between anabolic processes driven by oncogenes and homeostatic control maintained by tumor suppressors. Disruption of this balance through oncogenic activation or tumor suppressor inactivation drives the metabolic reprogramming that is fundamental to cancer development and progression.

Understanding the complex relationships between these regulators and their collective impact on metabolic pathways provides a framework for developing targeted therapeutic strategies. Future research should focus on elucidating context-specific functions of these molecules, developing more effective methods to target traditionally "undruggable" proteins, and identifying biomarkers that predict response to targeted therapies. As our knowledge of these fundamental regulators continues to expand, so too will our ability to design innovative treatments that specifically exploit the molecular vulnerabilities of cancer cells.

The Tumor Microenvironment and Epigenetics as Drivers of Metabolic Alterations

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ecosystem where dynamic interactions between cancer cells and surrounding stromal components drive tumor progression. A key feature of this ecosystem is metabolic reprogramming, a hallmark of cancer recently uncovered as a direct driver of epigenetic modification. This review focuses on the emerging role of histone lactylation, a novel post-translational modification, as a critical conceptual link between tumor cell metabolism, the epigenetic landscape, and TME homeostasis. We explore how metabolic reprogramming driven by oncogenic signals leads to the accumulation of lactate, which in turn serves as a precursor for histone lactylation, altering chromatin dynamics and gene expression. This pathway represents a promising frontier for understanding tumor progression and developing targeted therapeutic strategies. The content herein is framed within a broader thesis on the directed modulation of metabolic pathways as a guide for future research.

The "Warburg effect," or aerobic glycolysis, has long been recognized as a common metabolic phenotype in cancer cells, characterized by high glucose uptake and lactate production even in the presence of oxygen [19]. This metabolic reprogramming is not merely a passive consequence of oncogenic transformation but an active process that shapes the TME. The resulting accumulation of lactate, once considered a waste product, is now understood to be a key signaling molecule. In 2019, the discovery of histone lactylation introduced a novel mechanism through which lactate directly influences cellular function [19]. This modification changes the nucleosome structure and regulates chromatin dynamics, providing a direct pathway from metabolic reprogramming to stable changes in gene expression. This review will elucidate the association network connecting metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic modification via histone lactylation, and TME processes such as immune escape and angiogenesis, concluding with an examination of targeted treatment strategies emerging from this knowledge.

Metabolic Reprogramming and Lactate Production in the TME

Metabolic reprogramming is a fundamental adaptation that supports the biosynthetic and energetic demands of rapidly proliferating cancer cells. Carcinogenic signals drive this process, leading to a dependency on glycolysis and resulting in the substantial secretion of lactate into the TME [19]. This lactate is not merely a byproduct but a "fulcrum of metabolism" that plays a central role in tumor biology [19]. The accumulation of lactate contributes to an acidic TME, which can impair immune cell function and promote tumor invasion. Beyond its role in pH regulation, lactate is now recognized as a precursor for histone lactylation, creating an essential conceptual link between metabolism and epigenetics [19]. This pathway allows the metabolic state of the cell to directly influence gene expression programs.

Histone Lactylation: From Metabolic Reprogramming to Epigenetic Modification

Histone lactylation is a post-translational modification where lactate-derived lactyl groups are added to lysine residues on histones. This process directly incorporates the product of metabolic reprogramming into the epigenetic landscape [19]. The modification alters the nucleosome structure and regulates chromatin dynamics, leading to changes in gene expression that are closely associated with poor prognosis in tumors [19]. The discovery of histone lactylation has filled a critical gap in our understanding of how lactate regulates tumor metabolism, immune effects, and microenvironmental homeostasis. It represents an "important conceptual link between metabolism and epigenetics," providing a mechanism for the stable maintenance of a pro-tumorigenic state initiated by metabolic changes [19]. The process of metabolic reprogramming driving epigenetic change via lactylation is outlined in Figure 1.

Experimental Workflow for Investigating Histone Lactylation

A typical experimental protocol to investigate the role of histone lactylation in the TME involves a multi-faceted approach, as detailed below.

Figure 1. Experimental Workflow for Histone Lactylation Research. This diagram outlines the key phases of investigating the lactate-lactylation axis, from model establishment to target identification.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments:

Metabolic Perturbation and Lactate Modulation:

- Lactate Measurement: Intracellular and extracellular lactate levels can be quantified using commercial enzymatic assay kits (e.g., Lactate Dehydrogenase-based kits) or via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) for broader metabolomic profiling.

- Genetic Manipulation: Knockdown or knockout of key glycolytic enzymes (e.g., LDHA) using siRNA, shRNA, or CRISPR-Cas9 to reduce lactate production. Alternatively, overexpression of lactate transporters (e.g., MCT1) can be employed.

- Pharmacological Inhibition: Use of small molecule inhibitors targeting glycolytic pathways (e.g., 2-Deoxy-D-glucose) or lactate dehydrogenase (e.g., GSK2837808A).

Epigenetic Analysis via Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing (ChIP-seq):

- Cell Fixation: Cross-link proteins to DNA in cells or tissues using formaldehyde.

- Chromatin Shearing: Sonicate chromatin to fragment DNA into sizes of 200–500 bp.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate sheared chromatin with a validated, specific anti-histone lactylation antibody (e.g., anti-pan-Kla antibody). Use normal IgG as a control.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Reverse cross-links, purify DNA, and prepare sequencing libraries for high-throughput sequencing on platforms such as Illumina.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome, call peaks to identify genomic regions enriched for histone lactylation, and perform integrative analysis with RNA-seq data.

Functional Validation:

- Gene Expression Analysis: Perform RNA-seq or RT-qPCR on samples with modulated lactate levels or altered histone lactylation to identify downstream target genes.

- Phenotypic Assays: Assess changes in proliferation (MTT assay, colony formation), invasion (Transwell assay), and immune cell function (e.g., T-cell mediated cytotoxicity) in co-culture systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents and materials for studying histone lactylation and its biological functions.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Histone Lactylation Antibody | Immunodetection of lactylated histones for techniques like Western Blot, Immunofluorescence, and ChIP-seq. | Pan-specific anti-Kla antibody; site-specific antibodies (e.g., for H3K18la). |

| LDHA Inhibitor | Pharmacologically reduces endogenous lactate production to study the dependence of lactylation on glycolysis. | GSK2837808A; FX-11 [19]. |

| Recombinant Lactate Dehydrogenase | Enzyme used in coupled enzymatic assays for precise quantification of lactate concentration in cell culture media or lysates. | Available from various biochemical suppliers. |

| Glycolysis Stress Test Kit | Measures the glycolytic flux of cells in real-time using a Seahorse XF Analyzer. | Measures key parameters like Glycolytic Capacity and Glycolytic Reserve. |

| ChIP-seq Kit | Provides optimized buffers, beads, and protocols for performing Chromatin Immunoprecipitation. | Includes components for cross-linking, shearing, immunoprecipitation, and DNA purification. |

| Erythroxytriol P | Erythroxytriol P, MF:C20H36O3, MW:324.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sphenanlignan | Sphenanlignan, MF:C21H26O5, MW:358.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Association Network: Lactylation, TME, and Tumor Progression

Histone lactylation sits at the center of a complex association network, reciprocally influencing and being influenced by the TME. This network is a key driver of tumor progression.

Lactylation-Mediated Immunosuppression

Elevated histone lactylation levels in the TME have been closely linked to immune escape. Lactylation-driven gene expression contributes to immunosuppression, impacting immune monitoring and promoting events such as M2-like macrophage polarization, which supports tumor growth and angiogenesis [19]. This creates a feedback loop where tumor metabolism directly subverts the anti-tumor immune response.

Reverse Regulation: Metabolic Plasticity

The relationship between metabolism and epigenetics is not unidirectional. Evidence suggests that histone lactylation can, in reverse, regulate the plasticity of tumor metabolism [19]. This feedback mechanism fine-tunes metabolic pathways to maintain the tumor's adaptability and resilience, further engaging TME biological processes involving both immune and stromal cells.

The core association network connecting these elements is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Association Network of Lactylation in Tumor Progression. This diagram illustrates the cyclical relationship between metabolic reprogramming, histone lactylation, and pro-tumorigenic outcomes in the TME.

Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

The elucidation of the lactate-lactylation axis has opened new avenues for cancer therapy. Targeting this pathway offers potential for disrupting the crosstalk between metabolism and epigenetics that fuels tumor progression. Emerging strategies focus on key nodes within this network.

Table 2: Summary of potential targeted therapeutic strategies based on the lactate-lactylation network.

| Therapeutic Target | Strategy | Potential Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Lactate Production (e.g., LDHA) | Small molecule inhibitors to reduce lactate generation at the source. | Depletes the substrate for histone lactylation, potentially reversing immunosuppressive gene programs. |

| Histone Lactylation "Writers" / "Erasers" | Develop compounds that inhibit the enzymes adding lactyl groups or activate those removing them. | Directly modulates the epigenetic landscape, altering the expression of lactylation-dependent oncogenic pathways. |

| Lactate Transport (MCTs) | Block lactate export from tumor cells using MCT inhibitors. | Increases intracellular lactate to toxic levels while disrupting lactate signaling in the TME. |

| Lactylation-Downstream Effectors | Identify and target critical proteins encoded by lactylation-driven genes. | Offers a highly specific approach to counter the functional outcomes of lactylation, such as enhanced angiogenesis. |

The discovery of histone lactylation has fundamentally advanced our understanding of cancer biology by providing a direct mechanistic link between metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modification. This review has detailed how lactate, a metabolic byproduct of the Warburg effect, drives histone lactylation to reshape the epigenetic landscape and gene expression, thereby promoting tumor progression through effects on the TME, including immune evasion and angiogenesis. The association network connecting these processes highlights novel molecular targets for therapeutic intervention. Elucidating these problems provides a theoretical basis for further research and clinical application in this field, framing the directed modulation of metabolic pathways as a guiding principle for future scientific inquiry and drug development.

Directed modulation represents a powerful experimental paradigm for optimizing cellular systems, merging the exploratory capacity of directed evolution with the predictive analytical framework of Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA). This approach enables the rational redesign of metabolic pathways for enhanced production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and specialty chemicals. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of directed modulation, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing these strategies in metabolic engineering and drug development projects.

Directed modulation describes the controlled alteration of cellular metabolic pathways through the strategic integration of two complementary approaches: directed evolution and Metabolic Control Analysis. Where directed evolution employs iterative genetic diversification and selection to improve biocatalysts or cellular properties without requiring extensive prior knowledge of the system, MCA provides a quantitative framework for understanding how control is distributed across a metabolic network [20]. The fusion of these methodologies creates a powerful engineering cycle: MCA identifies key control points within a pathway, and directed evolution generates genetic diversity at these precise nodes to optimize flux toward a desired product.

The fundamental principle underlying directed modulation is the treatment of cellular metabolism as an evolvable system responsive to experimental selection pressures. Unlike natural evolution, which occurs under variable environmental pressures, directed evolution is accomplished under controlled selection pressure for predetermined functions, enabling the development of 'non-natural' metabolic activities with practical applications [20]. This deliberate steering of evolutionary trajectories allows researchers to solve complex metabolic engineering challenges that resist purely rational design approaches, particularly when dealing with interconnected pathways with stringent regulatory mechanisms.

Principles of Directed Evolution

Core Concepts and Historical Development

Directed evolution mimics natural evolutionary processes in laboratory settings through iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection. The first in vitro evolution experiments date to 1967, when Sol Spiegelman and colleagues iteratively selected RNA molecules based on their replication efficiency by Qβ bacteriophage RNA polymerase [21]. This pioneering Darwinian experiment established the foundational principle that biomolecules could be experimentally evolved under defined conditions. The field expanded significantly with the development of phage display in the 1980s, which enabled the selection of peptides and proteins with desired binding properties [21].

The directed evolution workflow consists of two fundamental steps: (1) library generation through the introduction of genetic diversity into target sequences, and (2) isolation of variants with improved or novel functions through screening or selection [21]. This cycle is repeated iteratively, allowing beneficial mutations to accumulate while deleterious ones are eliminated, progressively steering the biomolecule or pathway toward the desired functional outcome [20]. The combinatorial aspect of directed evolution distinguishes it from classical strain improvement, as it enables simultaneous incorporation of mutations across genomic elements of multiple parents, leading to more rapid phenotypic improvements [20].

Key Methodological Approaches

Directed evolution employs diverse strategies for generating genetic diversity, each with distinct advantages and applications. The table below summarizes principal techniques used in library generation:

Table 1: Directed Evolution Library Generation Methods

| Technique | Genetic Diversity | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-prone PCR | Point mutations across entire sequence | Simple implementation; no structural knowledge required | Limited sequence space sampling; mutagenesis bias [21] |

| DNA Shuffling | Random sequence recombination | Recombines beneficial mutations from multiple parents | Requires high sequence homology [21] |

| RAISE | Random short insertions and deletions | Enables indels across sequence; mimics natural diversity | Introduces frameshifts; limited to few nucleotides [21] |

| ITCHY/SCRATCHY | Random recombination of any two sequences | No sequence homology required | Does not preserve gene length and reading frame [21] |

| Site-saturation Mutagenesis | Focused mutagenesis at specific positions | Comprehensive exploration of chosen sites | Limited to few positions; large library sizes [21] |

| Orthogonal Replication Systems | In vivo random mutagenesis | Mutagenesis restricted to target sequence | Low mutation frequency; target size limitations [21] |

Figure 1: Directed Evolution Workflow. The iterative process of genetic diversification and selection enables continuous improvement of biomolecular function.

Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) Fundamentals

Theoretical Framework