E. coli vs. S. cerevisiae: Choosing the Optimal Metabolic Engineering Host

Selecting the right microbial host is a critical first step in developing efficient cell factories for the production of fuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals.

E. coli vs. S. cerevisiae: Choosing the Optimal Metabolic Engineering Host

Abstract

Selecting the right microbial host is a critical first step in developing efficient cell factories for the production of fuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the two most established metabolic engineering hosts: the prokaryote Escherichia coli and the eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We explore their foundational biology, contrasting GRAS status, native metabolism, and genetic tools. The discussion extends to methodological applications, highlighting their respective strengths in producing terpenoids, fatty acid-derived compounds, and complex natural products. The review also covers advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies, including CRISPR/Cas9, consortia engineering, and machine learning-guided workflows. Finally, we present a validated, comparative analysis of performance metrics for key products to guide researchers and industry professionals in making data-driven host selection decisions for their specific applications.

Innate Biology and Industrial Suitability of E. coli and S. cerevisiae

Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae serve as foundational pillars in metabolic engineering. This guide provides a structured comparison of their core physiological and metabolic traits, empowering researchers to make data-driven decisions when selecting a microbial host for bioproduction. The analysis covers central metabolism, substrate preferences, product profiles, and experimental methodologies, supported by quantitative data and pathway visualizations.

Core Physiological and Metabolic Traits

The fundamental physiological differences between prokaryotic E. coli and eukaryotic S. cerevisiae directly influence their performance as engineered hosts. The table below summarizes their key distinguishing traits.

Table 1: Core Physiological and Metabolic Traits of E. coli and S. cerevisiae

| Trait | Escherichia coli (Prokaryote) | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Eukaryote) |

|---|---|---|

| Central Carbon Metabolism | Highly efficient glycolysis; Pentose Phosphate Pathway [1] | Efficient glycolysis; Crabtree effect in high glucose [2] |

| Terpenoid Precursor Pathway | Native 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) pathway (from pyruvate & GAP) [2] | Native mevalonate (MVA) pathway (from acetyl-CoA) [2] |

| Redox Cofactor Regeneration | Primarily NADH/NAD+; strong anaerobic fermentation capacity | Primarily NADH/NAD+; can generate cytosolic NADPH via NAD+ kinase [2] |

| Common Metabolic Enzymes | 384 gene products involved in small molecule metabolism [3] | 390 gene products involved in small molecule metabolism [3] |

| Sequence Identity of Common Enzymes | ~70% of common enzymes have 30-50% sequence identity with yeast counterparts [3] | ~70% of common enzymes have 30-50% sequence identity with E. coli counterparts [3] |

| Stress Tolerance | Susceptible to phage infections [2] | Tolerates low pH, high osmotic pressure, and is resistant to phage infections [2] |

| Compartmentalization | None | Can harness subcellular compartments (e.g., mitochondria, ER) for pathway segregation [2] |

| Complex Protein Expression | Limited capacity for functional expression of membrane-bound eukaryotic P450 enzymes [2] | Excellent capacity for functional expression of membrane-bound plant cytochrome P450 enzymes [2] |

Analysis of Central Metabolic Pathways and Product Yields

The distinct metabolic networks of E. coli and S. cerevisiae lead to different theoretical yields and make them uniquely suited for different product classes.

Terpenoid Precursor Supply

A critical comparison lies in the supply of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), the universal terpenoid precursor. The two organisms employ entirely different native pathways.

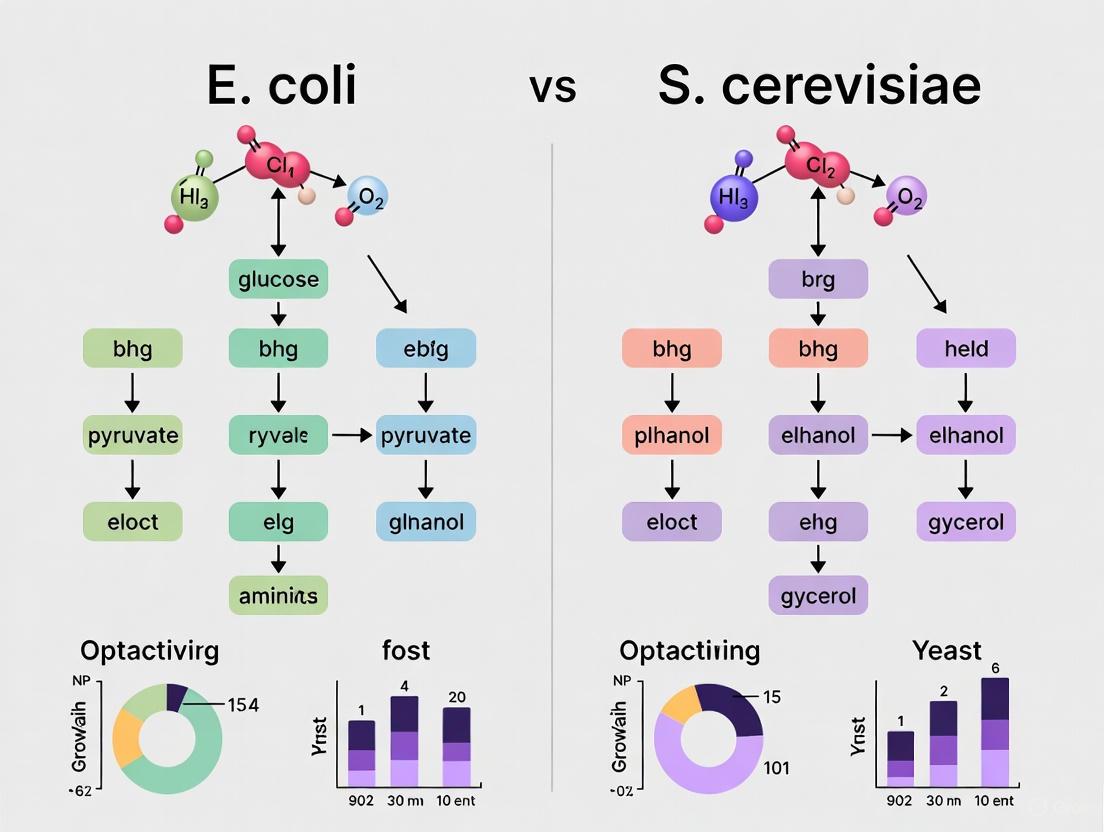

Diagram 1: Contrasting terpenoid precursor pathways.

The stoichiometry of the isolated pathways is identical in carbon yield. However, when integrated with the full central metabolic network, the DXP pathway in E. coli has a higher potential IPP yield from glucose. This is because forming acetyl-CoA from glucose in the MVA pathway results in carbon loss (as COâ‚‚ in the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction) [2]. The yield in both hosts is further constrained by energy (ATP) and redox (NADPH) requirements.

Substrate Utilization and Product Synthesis

Table 2: Comparative Performance on Different Substrates and Products

| Characteristic / Product | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Experimental Conditions & Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Glycerol Valorization (to Ethanol) | Lower performance: 0.17 - 0.45 g/L [4] | Higher performance: 0.49 - 0.73 g/L [4] | Micro-reactors (250 mL) with 10-30 g/L crude glycerol [4] |

| Heme Production | Higher titer reported: Up to 1.03 g/L in engineered strains [5] | Lower titer: 67 mg/L in engineered industrial strain [5] | Fed-batch fermentation in engineered production strains [5] |

| Natural Product Synthesis | Challenging for compounds requiring P450 enzymes [2] | Excellent host for terpenoids, phenylpropanoids (e.g., resveratrol) [6] [2] | Use of engineered strains with optimized precursor supply [6] |

| Specialty Chemical Example: Salidroside | Information not covered in search results | High titer achieved: 18.9 g/L in fed-batch fermentation [7] | Engineered strain with enhanced UDP-glucose supply [7] |

| Biliverdin / Phycoerythrobilin Production | Effective host: Successful production via heterologous expression of ApHO1 and PebS genes [8] | Information not covered in search results | Expression of genes from Arthrospira platensis and Prochlorococcus phage [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: In Silico Profiling of Terpenoid Production Potential

Objective: To compare the theoretical maximum yield of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) in E. coli and S. cerevisiae and identify metabolic engineering targets.

Methodology: Elementary Mode Analysis (EMA) and Constrained Minimal Cut Sets (cMCSs) [2].

- Network Reconstruction: Build genome-scale metabolic models incorporating central carbon metabolism (~65-69 reactions) and the respective terpenoid pathways (DXP for E. coli, MVA for S. cerevisiae).

- Stoichiometric Analysis: Calculate all possible steady-state flux distributions (Elementary Modes) to determine the theoretical maximum yield of IPP from different carbon sources (e.g., glucose, xylose, glycerol).

- Identification of Engineering Targets: Use computational algorithms to compute cMCSs. This identifies a minimal set of gene knockouts that couple cell growth to a high yield of the desired product, forcing the network to achieve production yields higher than those found in the wild-type state.

Key Insight: This in silico approach predicts that E. coli has a higher inherent potential for terpenoid production from glucose, but both hosts require engineering to meet the energy and redox demands for high-yield production [2].

Protocol: Growth-Coupled Selection Strain Development

Objective: To create a stable, high-producing strain by making cell survival dependent on the activity of a desired metabolic pathway.

Methodology: Metabolic Rewiring and Growth Phenotyping [9].

- Strain Design: Genetically engineer an E. coli strain to become auxotrophic for a specific compound (e.g., an amino acid) by knocking out one or more essential genes in its biosynthesis pathway.

- Pathway Integration: Introduce a heterologous biosynthetic pathway that, as a side reaction, produces the essential compound the strain can no longer make itself.

- Validation: Conduct labor-intensive growth phenotyping under various conditions (e.g., different carbon sources, nutrient limitations) to rigorously verify that robust cell growth is coupled to high flux through the production pathway of interest.

Key Insight: This "growth-coupled selection" strategy is highly effective for implementing synthetic metabolism for carbon capture, bioremediation, and bioproduction, as it prevents the loss of the production pathway over generations [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Host |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precision genome editing for gene knock-in, knockout, and repression. | Both [5] |

| Heterologous MVA Pathway | Replaces native DXP pathway to enhance and deregulate precursor supply for terpenoids. | E. coli [2] |

| Truncated HMG1 (tHMG1) | A feedback-insensitive version of a key enzyme to enhance flux through the native MVA pathway. | S. cerevisiae [2] |

| Plasmids for hem Gene Overexpression (e.g., HEM2, HEM3, HEM12, HEM13) | To amplify the heme biosynthetic pathway, increasing the supply of heme and related tetrapyrroles. | S. cerevisiae [5] |

| Plasmids for ho Gene Expression (e.g., ApHO1) | Enables the conversion of heme to biliverdin, a key intermediate for pigments like phycoerythrobilin. | E. coli [8] |

| Plasmids for Bilin Reductases (e.g., PebS) | Converts biliverdin into valuable end-products like phycoerythrobilin (PEB). | E. coli [8] |

| Glycosyltransferases (e.g., RrU8GT33) | Catalyzes the glycosylation of aglycones to produce glycosylated natural products like salidroside. | S. cerevisiae [7] |

| C16-Dihydroceramide | N-(hexadecanoyl)-sphinganine|High-Purity Ceramide | |

| N-Oleoyl taurine | N-Oleoyl taurine, CAS:52514-04-2, MF:C20H39NO4S, MW:389.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between E. coli and S. cerevisiae is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the project goals. E. coli generally offers advantages in growth speed, ease of genetic manipulation, and potentially higher yields for compounds aligned with its native metabolism, such as organic acids and proteins. S. cerevisiae is often the host of choice for complex natural products, especially those requiring eukaryotic post-translational modifications or P450 enzymes, and its GRAS status is beneficial for pharmaceutical and food applications. The most successful metabolic engineering endeavors, the "perfect trifecta," carefully align the choice of organism with the target product and available substrate [6].

In the field of metabolic engineering, the selection of a microbial host is paramount, influencing every aspect of research and development from initial gene cloning to commercial-scale production. Among the plethora of available options, Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have emerged as two preeminent workhorses. This guide provides a objective comparison between these two hosts, focusing on their safety certifications—a critical regulatory and practical consideration—and their demonstrated scalability in industrial bioprocesses. We frame this comparison within the context of metabolic engineering for the production of valuable compounds, presenting structured experimental data and protocols to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in making an informed choice for their specific applications.

Safety and Regulatory Status: GRAS and Beyond

A microorganism's safety status directly impacts its suitability for producing therapeutics, food ingredients, and nutraceuticals. Here, we clarify the formal definitions and typical applications for E. coli and S. cerevisiae.

Table 1: Safety and Regulatory Status of Microbial Chassis

| Host | Formal Status for Laboratory Strains | Key Regulatory Notes | Implications for Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) [10] | Granted GRAS status by the FDA for production of various recombinant proteins and compounds [10]. | Ideal for production of food ingredients, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals; simplifies regulatory approval. |

| Escherichia coli (K12, W) | Host-Vector 1 (HV1) Certified [11] | Certified as safe for use in P1/ML1 laboratory environments; often incorrectly described as GRAS [11]. | Well-established for industrial production of pharmaceuticals and chemicals; may require more scrutiny for direct food applications. |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2440 | Host-Vector 1 (HV1) Certified [11] [12] | A robust metabolic chassis that is explicitly not GRAS, despite frequent misclassification [11]. | Valued for environmental and industrial biocatalysis; its non-GRAS status is a consideration for product applications. |

Clarification of Safety Certifications

It is a common misconception in scientific literature that laboratory strains of E. coli such as K12 and W, as well as P. putida KT2440, hold GRAS status [11]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) grants GRAS status specifically for substances (including specific microbial strains) that are proven to be safe for ingestion [11]. In contrast, HV1 certification indicates that a microbial strain is determined to be safe to work with in a standard P1 (or ML1) containment laboratory, which is the case for E. coli K12 and W strains [11]. This distinction is crucial for research and development professionals when selecting a host for products intended for human consumption.

Comparative Analysis of Industrial Pedigree and Metabolic Performance

Both E. coli and S. cerevisiae have proven their worth in industrial fermentation, but they possess distinct metabolic architectures that make them suitable for different types of products. The following experimental case studies and data highlight their capabilities and the methodologies used to harness them.

Case Study: Enhanced Flavonoid Glycosylation inE. coliW

Experimental Objective: To engineer a robust platform in E. coli W for the glycosylation of poorly soluble flavonoids, overcoming limitations in precursor supply and product toxicity [13].

Protocol Summary:

- Host Selection & Validation: The non-model strain E. coli W was selected and demonstrated to have superior flavonoid tolerance and glycosylation capabilities compared to the model E. coli K12 strain [13].

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): ALE was employed to enhance the strain's sucrose metabolism, making sucrose the primary carbon source for both cell growth and UDP-glucose (UDPG) precursor synthesis [13].

- Metabolic Engineering: Key genes were knocked out (e.g.,

∆xylA,∆zwf,∆pgi) to reroute carbon flux from sucrose-derived glucose exclusively towards UDPG production, while fructose supported biomass formation [13]. - Pathway Overexpression: The gene

YjiCfrom Bacillus licheniformis, a glycosyltransferase that specifically targets the 7-position of flavonoids, was heterologously expressed [13]. - Bioprocess Optimization: A fed-batch process was implemented in a 3 L bioreactor, resulting in the production of 1844 mg/L of chrysin-7-O-glucoside (C7O) with a purification yield of 82.1% [13].

Figure 1: Engineered UDPG and C7O Biosynthesis Pathway in E. coli W. Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) and gene knockouts (Δpgi, Δzwf) optimize carbon flux from sucrose to the key precursor UDP-glucose (UDPG). The heterologous glycosyltransferase YjiC then uses UDPG to glycosylate chrysin, producing the valuable compound chrysin-7-O-glucoside (C7O).

Case Study: Advanced Metabolic Modeling and Protein Production inS. cerevisiae

Experimental Objective: To characterize and engineer S. cerevisiae for efficient heterologous protein production and complex metabolite synthesis [14] [10].

Protocol Summary:

- Strain-Specific Kinetic Modeling: Large-scale, genome-wide kinetic models (k-sacce306-CENPK and k-sacce306-BY4741) were parameterized using ^13^C Metabolic Flux Analysis (^13^C-MFA) data from wild-type and knockout mutants. This revealed that key enzymes in the TCA cycle, glycolysis, and amino acid metabolism drive metabolic differences between strains, indicating that kinetic models are strain-specific [14].

- Systems Metabolic Engineering: A multi-faceted approach is used for protein production [10]:

- Hyperexpression Systems: Codon optimization, promoter/terminator engineering, and increasing gene copy number.

- Protein Secretion Engineering: Engineering the unfolded protein response (UPR), vesicle trafficking, and signal peptides.

- Glycosylation Engineering: Humanizing glycosylation pathways to produce therapeutic proteins with appropriate post-translational modifications.

- Compartmentalization: Pathways are targeted to organelles like the endoplasmic reticulum to increase local metabolite concentrations and sequester toxic intermediates [15].

Table 2: Comparative Production Performance in Engineered Strains

| Host | Product | Titer/ Yield | Key Engineering Strategy | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli W [13] | Chrysin-7-O-glucoside (C7O) | 1844 mg/L (3.3 mM) | Optimized sucrose utilization & UDPG synthesis in a fed-batch bioreactor. | Demonstrates scalability and efficient use of low-cost carbon source for specialized metabolites. |

| E. coli (Engineered) [16] | Succinic Acid | Among highest bacterial titers (specific value not in source) | Native pathway engineering under anaerobic conditions. | High productivity, but requires neutral pH, complicating downstream processing. |

| S. cerevisiae [10] | Heterologous Proteins | Up to 49.3% (w/w) of its own protein | Multi-level engineering of expression, secretion, and glycosylation. | Confirms status as a high-yield platform for complex eukaryotic proteins. |

| Yarrowia lipolytica [16] | Succinic Acid | 209.7 g/L | Engineered pathway and use of crude glycerol feedstock. | Can produce at low pH, simplifying purification; utilizes diverse low-cost feedstocks. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful metabolic engineering in either host relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Host Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Biology Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems [15] [10], Inducible promoters [15], Centromeric (YCp) and episomal (YEp) plasmids [10] | Enables precise genome editing, gene knockout, and controlled gene expression. |

| Analytical & Modeling Software | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [17], ^13^C Metabolic Flux Analysis (^13^C-MFA) [14], Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) [14] | Predicts metabolic fluxes, identifies engineering targets, and validates strain performance in silico. |

| Specialized Enzymes & Pathways | Sucrose phosphorylase (BaSP) [13], Glycosyltransferases (e.g., YjiC) [13], Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) knockout [16] | Introduces or modulates specific heterologous reactions to drive production of target compounds. |

| Bioprocessing Materials | Fed-batch bioreactors [13], In situ extraction techniques [16], Membrane filtration [16] | Provides controlled, scalable environments for high-titer production and simplifies downstream purification. |

| Coniferin | Coniferin | Lignin Biosynthesis Precursor | Coniferin is a key glucoside for plant cell wall and lignin biosynthesis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Z-Gly-Pro-Gly-Gly-Pro-Ala-OH | Z-Gly-Pro-Gly-Gly-Pro-Ala-OH, CAS:13075-38-2, MF:C27H36N6O9, MW:588.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between E. coli and S. cerevisiae is not a matter of which host is universally superior, but which is optimal for a specific application. E. coli, particularly non-model strains like the W strain, offers rapid growth, high achievable titers, and unparalleled ease of genetic manipulation. Its HV1 certification makes it a mainstay for industrial production of chemicals, enzymes, and pharmaceuticals not intended for direct ingestion. S. cerevisiae, with its GRAS status, superior protein secretion machinery, and eukaryotic folding and modification systems, is the chassis of choice for producing therapeutic proteins, food ingredients, and complex natural products where safety and correct post-translational processing are paramount. Advances in systems biology, such as strain-specific kinetic models, and synthetic biology tools are pushing the capabilities of both hosts beyond their native limits, enabling the sustainable production of an ever-expanding portfolio of valuable molecules.

In the field of metabolic engineering, the selection of a microbial host is a critical determinant of bioproduction success. Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have emerged as the predominant workhorses, each possessing distinct native metabolic strengths that make them uniquely suited for different industrial applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two organisms, focusing on their inherent capabilities in high growth rate, stress tolerance, and complex pathway handling. Through analysis of current experimental data and methodologies, we aim to equip researchers with the evidence necessary to select the optimal chassis organism for specific metabolic engineering objectives, particularly in pharmaceutical and chemical production.

The fundamental physiological differences between E. coli and S. cerevisiae significantly influence their performance as metabolic engineering hosts. The table below summarizes their key native metabolic strengths based on current research findings.

Table 1: Native Metabolic Strengths of E. coli and S. cerevisiae

| Characteristic | E. coli | S. cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent Growth Rate | High-speed growth and facile genetic manipulation [18] | Robust in high-density fermentations [19] |

| Stress Tolerance | Engineered for tolerance to lignocellulosic inhibitors (e.g., furfural) [20] | Exceptional tolerance to osmotic stress, ethanol, and low pH [21] |

| Complex Pathway Handling | Modular coculture systems reduce metabolic burden [18] | Native eukaryotic protein processing and compartmentalization [19] |

| Representative Product Titer | 22.58 g/L Dopamine [22] | 67 mg/L Heme [5] |

| Fermentation Strategy | Two-stage pH control with co-factor feeding [22] | Glucose-limited fed-batch fermentation [5] |

In-depth Analysis of Native Strengths

High Growth Rate and Metabolic Flux

E. coli's Capability: E. coli is renowned for its rapid growth, enabling quick generation of biomass and high productivity. This characteristic is advantageous for rapid prototyping and high-yield production. A key strategy to leverage this without overburdening the cell is metabolic division engineering in consortia. By distributing long biosynthetic pathways across multiple specialized strains, this approach reduces the metabolic load on any single strain, preventing trade-offs between productivity and viability. For instance, a co-culture system was successfully employed for the de novo production of 12 flavonoids and 36 flavonoid glycosides, with titers ranging from 1.31 to 325.31 mg/L [18].

S. cerevisiae's Performance: While S. cerevisiae may not match the maximum growth rate of E. coli, it exhibits remarkable robustness in high-density fermentations, a critical trait for industrial-scale bioprocesses [19]. Its metabolism is highly versatile, but engineers must often navigate trade-offs where enhancing carbon flux toward a target product can reduce overall biomass, as observed in some central carbon metabolism engineering projects [19].

Innate Stress Tolerance

S. cerevisiae's Resilience: Industrial fermentations expose microorganisms to various stressors. S. cerevisiae demonstrates superior innate resilience to several of these challenges. A systematic evaluation of commercial strains showed significant variability, with certain strains like ACY19 exhibiting exceptional stress resilience, performing well under osmotic stress (1 M sorbitol), high ethanol concentrations (10%), and glucose limitation [21]. This innate tolerance is often linked to protective mechanisms like trehalose accumulation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) management [21]. Furthermore, its natural tolerance to acidic conditions simplifies the prevention of microbial contamination and simplifies downstream processing [19].

E. coli's Engineered Tolerance: In contrast, E. coli requires more extensive engineering to thrive in harsh industrial environments. For example, in lignocellulosic hydrolysates, inhibitors like furfural can cripple growth. Metabolic engineering interventions, such as expressing the transhydrogenase gene (pntAB) to balance NADPH/NADH ratios and overexpressing oxidoreductases like FucO, have been used to enhance E. coli's tolerance to furfural and hydroxymethyl furfural [20].

Handling Complex Metabolic Pathways

S. cerevisiae's Eukaryotic Machinery: For complex natural products, especially those from plants, S. cerevisiae offers a significant advantage due to its native eukaryotic protein processing machinery and intracellular compartmentalization. This allows for the proper folding, modification, and spatial organization of complex multi-enzyme pathways, which is often essential for the functional expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes and other eukaryotic proteins [19].

E. coli's Modular Coculture Approach: While lacking organelles, E. coli excels through engineering strategies that mimic compartmentalization. The modular coculture approach is a powerful method to handle complex pathways. By dividing a long metabolic pathway into smaller modules housed in separate E. coli strains, this strategy alleviates metabolic burden, minimizes enzyme promiscuity, and avoids the accumulation of toxic intermediates [18]. This was effectively demonstrated in the biosynthesis of flavonoids and their glycosides using stable, mutualistic co-culture systems [18].

Supporting Experimental Data and Protocols

To validate the comparative strengths outlined above, the following section details specific experimental data and protocols from key studies.

Case Study 1: Enhancing Heme Production in S. cerevisiae

This study showcases the engineering of an industrial yeast strain for improved heme production, highlighting its relevance as a flavor enhancer in plant-based meat alternatives [5].

Table 2: Key Experimental Data from S. cerevisiae Heme Production Study [5]

| Strain / Condition | Heme Titer (mg/L) | Fold Improvement vs. Wild-Type |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type KCCM 12638 (Batch) | ~5.3 (calculated) | 1.0x (Baseline) |

| ΔHMX1_H2/3/12/13 (Batch) | 9.0 | 1.7x |

| ΔHMX1_H2/3/12/13 (Fed-Batch) | 67.0 | ~12.6x |

| Medium Optimization (40 g/L YE, 20 g/L Peptone) | ~12.2 (calculated) | 2.3x |

Key Experimental Protocol:

- Strain Selection: An industrial S. cerevisiae strain (KCCM 12638) with naturally high heme content was selected from 31 edible strains [5].

- Medium Optimization: The complex YP medium was optimized by testing nitrogen sources and carbon sources. The highest heme production was achieved with 40 g/L yeast extract and 20 g/L peptone [5].

- Genetic Engineering (CRISPR/Cas9):

- Overexpression: The key rate-limiting enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway (HEM2, HEM3, HEM12, HEM13) were overexpressed. The combination of all four (H2/3/12/13 strain) increased heme by 78% [5].

- Knockout: The HMX1 gene, encoding heme oxygenase responsible for heme degradation, was inactivated to prevent product loss [5].

- Fermentation: Batch and glucose-limited fed-batch fermentations were conducted to assess heme production, with fed-batch drastically improving the final titer to 67 mg/L [5].

Diagram 1: Engineered Heme Biosynthesis Pathway in S. cerevisiae.

Case Study 2: High-Yield Dopamine Production in E. coli

This study illustrates the capacity for engineering E. coli to achieve high-titer production of a valuable chemical, dopamine, relevant to the pharmaceutical industry [22].

Table 3: Key Experimental Data from E. coli Dopamine Production Study [22]

| Parameter | Value / Detail |

|---|---|

| Final Strain | DA-29 (derived from W3110) |

| Final Dopamine Titer | 22.58 g/L |

| Fermentation Scale | 5 L Bioreactor |

| Key Genetic Modifications | Expression of DmDdC and hpaBC; promoter optimization; multi-copy expression; FADH2-NADH module |

| Key Fermentation Strategy | Two-stage pH control & Fe²âº-Ascorbic acid feeding |

Key Experimental Protocol:

- Host Selection: E. coli W3110 was chosen as the plasmid-free, defect-free chassis strain [22].

- Pathway Construction:

- A dopamine biosynthesis module was constructed by expressing hpaBC from E. coli BL21 (for tyrosine hydroxylation) and DmDdC from Drosophila melanogaster (for L-DOPA decarboxylation). DmDdC was selected as the most efficient among five screened decarboxylases [22].

- The tynA gene, encoding tyramine oxidase that degrades dopamine, was knocked out [22].

- Metabolic Optimization:

- Fermentation Strategy: A two-stage pH strategy was developed: the first stage supported cell growth, and the second stage maintained a low pH to reduce dopamine degradation. A combined feeding strategy of Fe²⺠and ascorbic acid was used to combat dopamine oxidation, culminating in a high titer of 22.58 g/L [22].

Diagram 2: Engineered Dopamine Biosynthesis Pathway in E. coli.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments and general metabolic engineering of these hosts.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precision genome editing for gene knockout, knock-in, and overexpression. | Inactivation of HMX1 in S. cerevisiae to prevent heme degradation [5]. |

| Optimized Promoters | Fine-tuning gene expression levels to balance metabolic flux and avoid intermediate accumulation. | Using T7, trc, and M1-93 promoters to regulate hpaBC and DmDdC expression in E. coli [22]. |

| Fed-Batch Fermentation | A process control strategy to maintain substrate limitation, improving product yield and titer. | Achieving 67 mg/L heme in S. cerevisiae via glucose-limited fed-batch fermentation [5]. |

| Specialized Media Components | ||

|  Yeast Extract & Peptone | Complex nitrogen sources in rich media for enhancing microbial growth and product formation. | Optimizing heme production in S. cerevisiae at 40 g/L yeast extract and 20 g/L peptone [5]. |

|  Trace Elements & Cofactors | Essential micronutrients and enzyme cofactors for supporting robust growth and specific enzymatic reactions. | Fe²⺠and ascorbic acid feeding in E. coli fermentation to prevent dopamine oxidation [22]. |

| Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate | A cost-effective, renewable feedstock derived from plant biomass for sustainable bioproduction. | Used as a substrate for biofuel production, though requires engineering for inhibitor tolerance [20] [23]. |

| 2-Chlorooctanoyl-CoA | 2-Chlorooctanoyl-CoA, CAS:149542-21-2, MF:C29H49ClN7O17P3S, MW:928.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NMDAR antagonist 3 | NMDAR antagonist 3, CAS:39512-49-7, MF:C11H14ClNO, MW:211.69 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between E. coli and S. cerevisiae is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with project goals. E. coli excels as a platform for achieving high volumetric yields of target compounds, leveraging its rapid growth and the power of division of labor in co-culture systems. S. cerevisiae stands out for its innate resilience in challenging fermentation environments and its superior capability to natively express and manage complex eukaryotic pathways. Researchers must weigh these native metabolic strengths—high growth and modularity versus stress tolerance and complex pathway handling—against the specific requirements of their metabolic engineering project to ensure success from the lab to industrial scale.

Within metabolic engineering, the selection of a microbial host and its accompanying genetic tools is paramount for success. The model organisms Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are prominent chassis for the production of valuable compounds, such as isoprenoids, with recent advances demonstrating high-yield production of molecules like 2-phenylethanol in engineered E. coli [24] [25]. The efficiency of introducing DNA into these hosts ("transformation") and the precision of subsequent genomic modifications ("genome editing") are critical determinants of project timelines and outcomes. This guide provides a structured, data-driven comparison of these foundational techniques, offering researchers a framework to select the optimal tools for engineering metabolic pathways in E. coli and S. cerevisiae.

Comparing Transformation Efficiency in Bacterial and Yeast Systems

Transformation is the process of introducing foreign DNA into a host cell. In molecular cloning workflows, it is used to amplify recombinant DNA molecules, a step essential for plasmid propagation and storage [26]. The methodology and efficiency of transformation differ significantly between the prokaryotic E. coli and the eukaryotic S. cerevisiae.

Bacterial Transformation inE. coli

The standard workflow for transforming E. coli involves making the cells "competent" to take up DNA, followed by a series of steps to introduce the plasmid and select successfully transformed cells [26] [27]. The two primary methods are heat shock and electroporation.

- Competent Cell Preparation: Naturally, E. coli has low competency, so cells must be treated to become permeable to DNA. For heat shock, this involves incubating cells in calcium chloride (CaClâ‚‚) and other cations to make the cell membrane more permeable [26]. For electroporation, cells are washed repeatedly with ice-cold deionized water or glycerol to remove conductive salts [26].

- Transformation/Heat Shock: Chemically competent cells are mixed with plasmid DNA and subjected to a brief heat shock (e.g., 42°C for 30-60 seconds), which creates a thermal gradient that drives the DNA into the cells [26] [27].

- Cell Recovery: After heat shock, cells are incubated in a nutrient-rich, antibiotic-free liquid medium like SOC. This recovery period allows the bacteria to express the antibiotic resistance gene encoded on the plasmid, which is crucial for subsequent selection [26] [27].

- Cell Plating & Selection: The cells are plated on solid agar media containing an antibiotic. Only cells that have successfully taken up the plasmid and expressed the resistance gene will grow into colonies [26].

The transformation efficiency is a key metric, expressed as the number of colony-forming units (CFU) per microgram of plasmid DNA used (CFU/μg) [26]. Efficiency is highly dependent on the method and the state of the competent cells.

Transformation inS. cerevisiae

While the provided search results focus on E. coli transformation protocols, it is established knowledge in the field that S. cerevisiae transformation differs fundamentally. Yeast, being a eukaryote, has a thick cell wall that must be compromised, often using enzymatic digestion to create protoplasts or treatments with lithium acetate (LiAc) to facilitate DNA uptake. Efficiencies can be high but are generally lower than optimized E. coli protocols. The choice between E. coli and yeast for a specific metabolic engineering project often hinges on other factors, such as the organism's native metabolic capabilities and its ability to perform post-translational modifications required for complex pathway enzymes [24].

Quantitative Comparison of Transformation Efficiency

The table below summarizes key characteristics of the transformation process for E. coli, the system for which detailed protocol data is available in the search results.

Table 1: Transformation Workflow and Efficiency in E. coli

| Feature | Chemical Transformation (Heat Shock) | Electroporation |

|---|---|---|

| Key Principle | Chemical (e.g., CaClâ‚‚) treatment and heat shock create membrane permeability [26] | A high-voltage electric pulse induces transient pores in the cell membrane [26] |

| Typical Efficiency | Ranges from (10^5) to (10^9) CFU/μg for standard plasmids; significantly lower for large plasmids and ligation mixtures [26] [27] | Generally higher than chemical methods, often > (10^{10}) CFU/μg, and more effective for large plasmids/BACs [27] |

| DNA Amount | 1–10 ng of intact plasmid DNA is recommended [26] | Requires less DNA than chemical transformation [27] |

| Critical Steps | - Competent cell thawing on ice- Precise heat-shock timing (30-60 secs)- Adequate outgrowth in SOC medium (∼45 mins) [26] [27] | - Extensive washing to remove all salts- Use of specific electroporation cuvettes (e.g., 0.1 cm gap)- Immediate post-pulse addition of recovery media [26] |

| Best Applications | Routine plasmid amplification, cloning with standard-sized plasmids [27] | Applications requiring high efficiency, such as with low DNA amounts, large plasmids (>10 kb), or BACs [27] |

A Guide to Modern Genome Editing Platforms

Once a host organism is transformed with a cloning vector, more advanced metabolic engineering often requires precise, stable changes to the host's own genome. This is the domain of genome editing technologies, which enable targeted gene knockouts, knock-ins, and corrections.

The Genome Editing Workflow

Genome editing tools function as programmable molecular scissors. They create a double-strand break (DSB) at a specific location in the genome, which the cell then repairs through one of two primary pathways [28] [29]:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. This can disrupt the gene's coding sequence, making NHEJ the preferred pathway for gene knockouts [28] [29].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair mechanism that uses a DNA repair template to fix the break. This allows for specific nucleotide changes, gene insertions, or gene corrections [28] [29].

The fundamental workflow involves designing the editing machinery for the target sequence, delivering it into the cell, and then analyzing the outcomes to identify successfully edited clones.

Diagram 1: Core genome editing workflow showing key steps and repair pathways.

Comparison of Major Editing Platforms

The field is dominated by several nuclease platforms, primarily Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system [28] [29].

- CRISPR-Cas9: The most recently developed system, CRISPR uses a guide RNA (gRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a complementary DNA sequence. The target site must be adjacent to a short PAM sequence (e.g., NGG for SpCas9) [28] [29]. Its simplicity, deriving from easy-to-design RNA guides, has made it the most widely adopted system.

- TALENs: TALENs are engineered proteins that use Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) domains to bind DNA. Each TALE repeat recognizes a single nucleotide. A pair of TALEN proteins must bind on opposite strands of the target DNA with a specific spacing for the FokI nuclease domain to dimerize and create a DSB [29].

- ZFNs: An older technology, ZFNs use zinc finger protein domains to bind DNA (each recognizing a DNA triplet) and the FokI nuclease to create breaks. Like TALENs, they function as pairs and require complex protein engineering for each new target [28].

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Platforms

The table below benchmarks the key performance characteristics of CRISPR-Cas9 against traditional methods like TALENs and ZFNs, based on current literature.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major Genome Editing Platforms

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs | ZFNs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Mechanism | RNA-guided (gRNA) [28] [29] | Protein-DNA binding (TALE repeats) [29] | Protein-DNA binding (Zinc fingers) [28] |

| Ease of Design & Use | Simple; designing a new gRNA is fast and inexpensive [28] | Complex; requires protein engineering for each target [28] [29] | Very complex; requires specialized expertise [28] |

| Targeting Constraints | Requires PAM sequence (e.g., NGG) adjacent to target site [29] | Requires a pair of binding sites with specific spacing; sensitive to DNA methylation [29] | Requires a pair of binding sites with specific spacing [28] |

| Editing Efficiency | High; indel formation rates often >70% reported [29] | Moderate to High; e.g., 33% indel formation in one study [29] | Variable; can be high but difficult to predict [28] |

| Specificity (Off-Target Risk) | Moderate; gRNA can tolerate mismatches, leading to off-target effects. Improved with high-fidelity Cas9, paired nickases, or base editing [28] [29] [30] | High; the long, paired binding site is extremely specific, with little evidence of off-target activity [29] | High; well-validated designs show high specificity [28] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High; capable of editing multiple genes simultaneously by co-expressing several gRNAs [28] | Low; difficult and labor-intensive to engineer multiple TALEN pairs [28] | Low; similar limitations to TALENs [28] |

| Relative Cost | Low [28] | High [28] | High [28] |

Advanced CRISPR Systems: Base and Prime Editing

The core CRISPR system has evolved beyond simple DSBs. Base editing enables direct, irreversible conversion of one DNA base pair to another without requiring a DSB or a donor template, minimizing indel byproducts [28] [30]. Prime editing offers even greater versatility, enabling all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, also without requiring DSBs [28] [30]. A benchmarked prime editing platform has demonstrated remarkably high-efficiency substitution editing, with precise editing rates reaching ~95% in mismatch repair-deficient cells, making it suitable for functional genomics screens [30].

Diagram 2: Evolution of CRISPR systems from traditional nuclease to advanced base and prime editors.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Robust experimental protocols and validation are critical for successful genome editing.

- Thaw Competent Cells: Thaw a 50-100 µL aliquot of chemically competent E. coli on ice.

- Add DNA: Add 1-10 ng of plasmid DNA (or 1-5 µL of a ligation mixture) to the cells. Mix gently by tapping. Do not vortex.

- Incubate on Ice: Incubate the cell/DNA mixture on ice for 20-30 minutes.

- Heat Shock: Transfer the tube to a 42°C water bath for exactly 30 seconds. Do not shake.

- Recovery: Immediately return the tube to ice for 2 minutes.

- Outgrowth: Add 250-1000 µL of SOC or LB medium to the cells. Shake at 37°C for 45 minutes.

- Plate: Spread 10-200 µL of the cell suspension onto a pre-warmed LB agar plate containing the appropriate antibiotic.

- Incubate & Select: Incubate the plate upside down at 37°C overnight (16-24 hours). Pick individual colonies for screening.

Quantifying Genome Editing Efficiency

After performing edits, it is essential to quantify the efficiency and specificity of the modifications. Multiple molecular techniques are available, each with advantages and limitations [31].

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) or SURVEYOR Assay: These are mismatch cleavage assays. PCR amplicons from the edited population are denatured and reannealed, creating heteroduplexes if indels are present. The T7E1 enzyme cleaves these mismatches, and the cleavage products are visualized by gel electrophoresis. The fraction of cleaved DNA is used to estimate editing efficiency [31].

- Sanger Sequencing with Deconvolution Software: PCR amplicons from the edited cell population are Sanger sequenced. The resulting chromatogram is a mixture of signals. Web-based tools like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) or TIDE (Tracking of Indels by DEcomposition) analyze the trace data to deconvolute the mixture and quantify the spectrum and frequency of indels [31].

- Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (AmpSeq): This next-generation sequencing (NGS) method is considered the "gold standard." The target locus is PCR-amplified from the population and sequenced to high depth, providing nucleotide-level resolution of all editing outcomes and their precise frequencies with high sensitivity and accuracy [31].

Table 3: Comparison of Methods for Quantifying Genome Editing Efficiency

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Throughput | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7E1 / SURVEYOR | Mismatch cleavage & gel electrophoresis [31] | Low to Moderate | Low | Inexpensive and quick | Semi-quantitative; no sequence detail |

| Sanger (ICE/TIDE) | Sequencing trace deconvolution [31] | Moderate | Moderate | Cost-effective; provides some sequence info | Lower sensitivity for complex or low-frequency edits |

| PCR-CE/IDAA | PCR fragment analysis by capillary electrophoresis [31] | High | High | Accurate and quantitative for indel sizes | Does not provide actual sequence data |

| AmpSeq (NGS) | High-depth sequencing of amplicons [31] | Very High | High | Gold standard; quantitative with full sequence detail | Higher cost and longer turnaround time |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for executing transformation and genome editing experiments.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| Competent Cells (E. coli) | Specially prepared bacterial cells with enhanced ability to uptake foreign DNA. Available in chemically competent (for heat shock) or electrocompetent (for electroporation) forms with a range of efficiencies [26] [27]. |

| Plasmid Vectors | Carrier DNA molecules containing an origin of replication and a selectable marker (e.g., antibiotic resistance). Used to clone and amplify DNA sequences of interest [26] [27]. |

| SOC Medium | A nutrient-rich recovery medium used after bacterial transformation. Contains glucose and MgClâ‚‚, which help boost cell viability and transformation efficiency by 2- to 3-fold compared to standard LB broth [26]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System Components | Includes the plasmid(s) encoding the Cas9 nuclease and the guide RNA (gRNA). May also include a donor DNA template for HDR-mediated precise editing [28] [29]. |

| TALEN or ZFN Plasmids | Engineered plasmids encoding the sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins fused to the FokI nuclease domain. Used for targeted genome editing with high specificity [28] [29]. |

| Selection Antibiotics | Added to growth media to select for cells that have successfully taken up and express the resistance gene from the plasmid vector (e.g., ampicillin, kanamycin) [26] [27]. |

| Metabolic Pathway Databases (e.g., MetaCyc) | Curated databases of metabolic pathways and enzymes used for prospecting and designing engineered pathways in host organisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae [32] [33]. |

Engineering Strategies and Product-Specific Success Stories

In the pursuit of a sustainable bio-based economy, metabolic engineering has emerged as a pivotal discipline for rewiring microbial metabolism to produce valuable chemicals. Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have established themselves as the preeminent host organisms for industrial bioproduction, each offering distinct advantages and limitations [19]. The strategic selection between these hosts depends critically on the target molecule, pathway complexity, and production requirements. This comparative analysis examines the fundamental principles of heterologous gene expression and modular design in these model organisms, providing researchers with experimentally-validated data to inform host selection and engineering strategies.

While both microorganisms serve as versatile cellular factories, their intrinsic biological differences dictate specialized applications. E. coli typically offers faster growth, higher transformation efficiency, and well-characterized genetics, making it ideal for rapid prototyping and pathway screening. Conversely, S. cerevisiae provides eukaryotic protein processing, superior tolerance to metabolic stress, and generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status, advantages particularly valuable for pharmaceutical production and complex pathway expression [19] [34]. Understanding these distinctions enables researchers to strategically deploy each chassis according to its strengths, ultimately accelerating the development of efficient microbial cell factories.

Host Organism Comparison: E. coli versus S. cerevisiae

The strategic decision between employing E. coli or S. cerevisiae extends beyond their prokaryotic-eukaryotic classification to encompass practical considerations of pathway architecture, product toxicity, and scalability. The table below summarizes key performance metrics and optimal applications for each chassis organism, derived from recent advances in metabolic engineering.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of E. coli and S. cerevisiae as Metabolic Engineering Hosts

| Characteristic | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred Applications | Short pathways, biofuels, organic acids, flavonoids | Long pathways, terpenoids, P450-dependent reactions, pharmaceuticals |

| Typical Titers Achieved | Flavonoids: 61-325 mg/L [18]; Heme: 1.03 g/L [5] | Taxadiene: 528 mg/L [35]; Salidroside: 18.9 g/L [36]; Heme: 67 mg/L [5] |

| Key Engineering Strategies | Co-culture systems [18]; CRISPR/Cas9 [20]; Modular pathway division [18] | Modular engineering [34] [35]; MVA pathway enhancement [35]; Enzyme fusion [35] |

| Native Metabolite Strengths | Aromatic amino acids [18] | Acetyl-CoA, MEVALONATE pathway precursors [34] [35] |

| Glycosylation Capability | Limited, requires pathway engineering [18] | Native capacity, advantageous for flavonoid & pharmaceutical production [18] [36] |

| Tolerance to Fermentation Inhibitors | Engineered tolerance to furfural possible [20] | Native robustness in industrial conditions; tolerance to acidic pH [19] |

Recent research highlights the effectiveness of co-culture systems in E. coli for distributing metabolic burden. One study demonstrated production of 12 flavonoids (61.15–325.31 mg/L) and 36 flavonoid glycosides through metabolic division of labor across engineered bacterial consortia [18]. For S. cerevisiae, modular pathway engineering has proven highly successful, with one investigation achieving ~280-fold improvement in β-ionone production (to 0.98 g/L) by systematically optimizing three dedicated metabolic modules [34].

Case Study: Flavonoid Production in E. coli Consortia

Experimental Design and Engineering Methodology

A groundbreaking approach in E. coli engineering involves designing synthetic microbial consortia that distribute long biosynthetic pathways across specialized strains. This strategy effectively addresses the fundamental challenges of metabolic burden and enzyme promiscuity that often limit production in single-strain systems [18]. The methodology follows a systematic protocol:

Pathway Deconstruction: The target pathway (e.g., for flavonoid biosynthesis) is divided into logical modules at strategic metabolic nodes. For flavonoids, this typically separates p-coumaric acid production, flavonoid skeleton construction, and glycosylation modules [18].

Strain Specialization: Individual E. coli strains are engineered to overexpress specific pathway modules. Auxotrophic markers and orthogonal carbon source utilization are implemented to ensure stable co-culture maintenance through obligate cross-feeding [18].

Metabolic Optimization: Within each specialized strain, codon-optimized genes are expressed under constitutive or inducible promoters. Key nodes are targeted for enhancement, such as knocking out feedback inhibition in the shikimate pathway to increase malonyl-CoA availability [18].

Consortium Cultivation: Engineered strains are cultured in defined media with controlled carbon sources. The stabilization of the community is enforced through mutualistic dependencies, where each strain supplies essential metabolites to others [18].

Key Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for E. coli Pathway Engineering

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precise genome editing; gene knockouts/insertions | Used for metabolic engineering in both E. coli and yeast [5] [20] |

| Codon Optimization Tools | Enhanced heterologous gene expression | Software for designing host-specific gene sequences [37] |

| Auxotrophic Markers | Selection and maintenance of plasmid/strain stability | e.g., uracil markers for selective media [36] |

| Shikimate Pathway Enzymes (Feedback-resistant) | Increased precursor supply for aromatic compounds | AroG^{fbr}, PheA^{fbr} mutants for enhanced p-coumaric acid production [18] |

| Glycosyltransferases | Addition of sugar moieties to flavonoid scaffolds | Production of 36 different flavonoid glycosides [18] |

Case Study: Terpenoid Engineering in S. cerevisiae

Experimental Framework and Modular Design

The complex architecture of terpenoid pathways makes them ideal candidates for modular engineering in S. cerevisiae. The fundamental approach involves partitioning the biosynthetic route into discrete, manageable segments that can be independently optimized before reintegration. The following diagram illustrates this systematic approach to modular pathway engineering:

Diagram 1: Modular pathway design for terpenoid production. Each module is independently optimized before system integration.

The experimental workflow for implementing this strategy involves:

Module Definition: The pathway from glucose to target terpenoid (e.g., taxadiene or β-ionone) is divided into three specialized modules: (1) cytosolic acetyl-CoA supply, (2) mevalonate pathway to GGPP, and (3) product synthesis module [34] [35].

Individual Module Optimization: Each module is engineered and evaluated separately. For the mevalonate pathway, this involves overexpression of rate-limiting enzymes (tHMG1, ERG20, IDI, GGPPS) and downregulation of competing pathways (ERG9) [35].

Combinatorial Assembly: Optimized modules are systematically integrated into the yeast genome using advanced DNA assembly techniques. CRISPR-Cas9 systems specifically developed for Y. lipolytica and S. cerevisiae enable precise, multiplexed integration [34].

System Balancing: The relative expression of modules is fine-tuned using promoter engineering and gene copy number variation to balance metabolic flux and prevent intermediate accumulation or toxicity [35].

Key Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for S. cerevisiae Pathway Engineering

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Yeast genome editing; multiple integrations | pCAS1yl system for Y. lipolytica [34]; various systems for S. cerevisiae [35] |

| MVA Pathway Genes | Enhanced terpenoid precursor supply | tHMG1, ERG20, IDI, GGPPS overexpression [35] |

| Codon-Optimized Synthases | Specialized terpenoid production | Taxadiene synthase (TS) from Taxus brevifolia [35] |

| Constitutive Promoters | Tunable gene expression control | PTEF1, PEXP1, PGPD2 for varying expression strength [34] |

| Episomal Plasmids | Rapid pathway prototyping | URA3-based plasmids for combinatorial testing [35] |

Comparative Analysis of Engineering Outcomes

Direct comparison of engineering outcomes reveals host-specific advantages for different product categories. For flavonoid compounds, E. coli consortia achieved remarkable diversity, producing 12 flavonoids and 36 flavonoid glycosides with titers reaching 325.31 mg/L for aglycones and 191.79 mg/L for glycosides [18]. The co-culture approach successfully alleviated metabolic burden while enabling plug-and-play pathway extensions for isoflavonoids and dihydrochalcones.

For terpenoid biosynthesis, S. cerevisiae demonstrates clear advantages in handling complex eukaryotic pathways. Taxadiene production reached 528 mg/L in engineered yeast through balanced overexpression of mevalonate pathway genes and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase [35]. Similarly, the modular engineering of β-ionone production in Y. lipolytica achieved ~1 g/L in fed-batch fermentation, representing a 280-fold improvement over the baseline strain [34]. These successes highlight the critical importance of pathway balancing, particularly when dealing with toxic intermediates.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in engineering philosophy between the two host systems:

Diagram 2: Comparative engineering strategies for E. coli (distributed) versus S. cerevisiae (modular) approaches.

This comparative analysis demonstrates that both E. coli and S. cerevisiae offer powerful but distinct capabilities for metabolic engineering. E. coli excels in distributed pathway engineering through synthetic consortia, particularly for compounds like flavonoids where pathway segmentation reduces metabolic burden and mitigates enzyme promiscuity [18]. S. cerevisiae provides superior performance for complex terpenoid pathways, where its endogenous mevalonate pathway and eukaryotic protein handling capabilities offer inherent advantages [34] [35].

The decision framework for host selection should consider multiple factors: pathway length and complexity, enzyme requirements (particularly P450 systems), product toxicity, and desired production scale. For rapid prototyping of shorter pathways, E. coli often provides quicker results, while for industrial production of complex molecules, particularly pharmaceuticals, S. cerevisiae frequently delivers superior performance. As engineering tools continue to advance in both host systems, the modular and distributive principles outlined here will remain fundamental to successful metabolic engineering across diverse applications.

The selection of a microbial host is a critical determinant of success in metabolic engineering. While Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been widely used for its historical applications and eukaryotic capabilities, Escherichia coli has emerged as a superior platform for many industrial biotechnology applications. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two metabolic engineering hosts through detailed case studies and experimental data, demonstrating E. coli's particular advantages in achieving high-titer production of organic acids and non-native chemicals.

The Case for E. coli as a Metabolic Engineering Platform

E. coli offers distinct advantages as a metabolic engineering chassis: rapid growth (doubling every 20-30 minutes), comprehensive genetic toolkits, well-characterized metabolism, and ability to utilize diverse carbon sources [38] [39]. Its status as a proven industrial workhorse is reinforced by successful scale-up processes for numerous chemicals.

S. cerevisiae, while possessing beneficial traits such as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status and robustness in industrial fermentations, faces structural limitations in central metabolism that constrain its potential for producing certain non-native chemicals [17] [40]. Comparative analyses have revealed that the structurally limited flexibility of yeast's central metabolism severely reduces cell growth when engineered for production of compounds like butanols and propanols [17].

High-Titer Production of Organic Acids in E. coli

Organic acids represent valuable platform chemicals with applications across chemical, food, and pharmaceutical industries. E. coli has been successfully engineered for high-level production of various organic acids, overcoming inherent toxicity challenges through systematic engineering approaches.

para-Hydroxybenzoic Acid (PHBA) Production Case Study

PHBA is extensively used in food and cosmetics industries as a shelf-life enhancing additive. Recent engineering efforts have achieved remarkable production metrics in E. coli [41].

Table 1: E. coli Engineering Strategy for PHBA Production

| Engineering Strategy | Specific Modification | Impact on Production |

|---|---|---|

| Chassis Selection | Use of L-phenylalanine-overproducing strain | Enhanced precursor availability |

| Pathway Optimization | Modular engineering of key genes | Increased metabolic flux to PHBA |

| Adaptive Evolution | Accelerated evolution system with PHBA-responsive promoter | 47% increase in ICâ‚…â‚€ value for PHBA tolerance |

| Fermentation Optimization | Controlled 5-L bioreactor conditions | Maximized titer and productivity |

Experimental Protocol: The PHBA production strain was constructed through rational metabolic engineering of E. coli Phe, an L-phenylalanine-overproducing strain. Key modifications included reinforcement of the shikimate pathway, deletion of competing pathways, and fine-tuning expression of rate-limiting enzymes. An accelerated adaptive evolution system was implemented using a PHBA-responsive promoter (PyhcN) coupled with a mutation-generating module to enhance strain tolerance. Fed-batch fermentation was performed in a 5-L bioreactor with optimized feeding strategy and dissolved oxygen control [41].

Results: The engineered strain achieved a PHBA titer of 21.35 g/L with a productivity of 0.44 g/L/h and yield of 0.19 g/g glucose. This represents the highest reported PHBA production in E. coli and a 2.66-fold improvement in productivity compared to previous studies [41].

Organic Acid Toxicity and Tolerance Mechanisms

A significant challenge in organic acid production is product toxicity. E. coli experiences growth inhibition at concentrations below economically viable production levels due to both pH effects and anion-specific impacts on metabolism [38]. Undissociated organic acids freely diffuse across membranes and dissociate in the neutral cytoplasm, releasing protons that lower internal pH and anions that inhibit metabolic functions [38].

E. coli has evolved multiple tolerance mechanisms including:

- Decarboxylation reactions that consume intracellular protons

- Ion transporters that remove protons from the cell

- Increased stress gene expression and membrane composition changes

- Activation of specific tolerance systems in exponential growth phase under sublethal pH conditions [38]

Production of Non-Native Chemicals: E. coli vs. S. cerevisiae

The capacity to produce non-native chemicals demonstrates the flexibility and engineering potential of microbial chassis. Comparative studies reveal distinct advantages of E. coli for many compound classes.

Cofactor F420 Production Case Study

Cofactor F420 is a low-potential, two-electron redox cofactor not naturally produced by E. coli but found in some Archaea and Eubacteria. Heterologous production in E. coli required systematic engineering of precursor pathways [42].

Experimental Protocol: Researchers expressed F420 biosynthetic genes from Mycobacterium smegmatis (FbiD, FbiC, FbiB) and Methanosarcina mazei (CofD) in E. coli. Metabolic modeling using the iEco-F420 genome-scale model identified phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP) as a limiting precursor. PEP availability was enhanced through carbon source selection (pyruvate, fumarate) and overexpression of PEP synthase. Fermentations were conducted in mineral medium with various carbon sources to assess F420 production and cell growth [42].

Results: Engineered E. coli achieved a F420 yield of 1.60 μmol/g DCW with a space-time yield of 123 nmol/h/g DCW - a 40-fold improvement over previous reports and 4-fold higher than recombinant M. smegmatis. This demonstrates E. coli's superior capacity for producing complex non-native cofactors when properly engineered [42].

Glycerol Pathway Evolution Case Study

In a compelling demonstration of metabolic flexibility, the S. cerevisiae glycerol pathway was successfully evolved in E. coli to achieve superior production performance [43].

Experimental Protocol: The E. coli central metabolism was engineered to create an obligatory link between glucose consumption and glycerol production by deleting the tpiA gene (encoding triose phosphate isomerase) and introducing the S. cerevisiae glycerol pathway (GPD1 and GPP2) as an artificial bicistronic operon. Continuous culture under metabolic pressure led to emergence of a variant strain with enhanced glycerol production [43].

Results: Evolution in chemostat culture resulted in a spontaneous deletion between GPD1 and GPP2 genes, producing a fusion protein with both glycerol-3-P dehydrogenase and glycerol-3-P phosphatase activities. The fusion enzyme exhibited partial substrate channeling, leading to improved kinetic efficiency including 7-fold reduced transient time and 2-fold increased production rate. The evolved strain produced glycerol from glucose at high yield, concentration, and productivity [43].

Comparative Performance for Non-Native Chemicals

Table 2: Production Performance Comparison for Non-Native Chemicals

| Chemical | Host | Titer | Productivity | Key Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHBA | E. coli | 21.35 g/L | 0.44 g/L/h | Systems metabolic engineering + adaptive evolution [41] |

| PHBA | S. cerevisiae | 2.9 g/L | N/A | Pathway optimization + supplementation [41] |

| PHBA | P. taiwanensis | 9.9 g/L | N/A | Overexpression of key enzymes [41] |

| Cofactor F420 | E. coli | 1.60 μmol/g DCW | 123 nmol/h/g DCW | Metabolic modeling + precursor optimization [42] |

| Cofactor F420 | M. smegmatis | 3.0 μmol/g DCW | 31 nmol/h/g DCW | Native producer, recombinant expression [42] |

| 1-Butanol | E. coli | 30 g/L | N/A | Introduction of clostridial pathway + deletion of competing pathways [17] |

| 1-Butanol | S. cerevisiae | 2.5 mg/L | N/A | Expression of bacterial genes in yeast [17] |

Visualizing Engineering Strategies and Metabolic Pathways

Metabolic Engineering Workflow for Enhanced Production

Organic Acid Toxicity and Tolerance Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Strains | BL21(DE3), W3110, JM109, specialized variants (e.g., L-phenylalanine overproducer) [44] [41] | Chassis for pathway engineering and production |

| Expression Systems | pET vectors, pTrcHisA, pEM, pCDR, pRARE (for rare tRNA supplementation) [44] [41] | Heterologous gene expression and pathway assembly |

| Carbon Sources | Glucose, glycerol, pyruvate, succinate, fructose [45] [42] | Varying entry points to central metabolism for precursor optimization |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC, GC-MS, NMR, enzyme assays [41] [42] | Quantification of metabolites and pathway flux analysis |

| Modeling Software | Genome-scale metabolic models (e.g., iEco-F420), flux balance analysis tools [42] | In silico prediction of metabolic bottlenecks and engineering targets |

| Evolution Systems | Chemostat culture, adaptive laboratory evolution, accelerated evolution systems [41] [43] | Strain improvement through directed evolution |

| Boc-C16-COOH | 18-(tert-Butoxy)-18-oxooctadecanoic Acid|Boc-C16-COOH | 18-(tert-Butoxy)-18-oxooctadecanoic acid is a versatile linker for chemical synthesis. This product is for research use only and is not intended for personal use. |

| H-D-Phe(3-F)-OH | H-D-Phe(3-F)-OH, CAS:110117-84-5, MF:C9H10FNO2, MW:183.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The case studies presented demonstrate E. coli's distinct advantages as a metabolic engineering host for high-titer production of both organic acids and non-native chemicals. Through systematic metabolic engineering approaches—including pathway optimization, tolerance engineering, and precursor balancing—E. coli consistently achieves superior production metrics compared to S. cerevisiae and other microbial hosts.

While S. cerevisiae remains valuable for specific applications requiring eukaryotic protein processing, E. coli offers faster growth, more advanced genetic tools, greater metabolic flexibility, and proven industrial scalability. The integration of systems biology, computational modeling, and high-throughput engineering approaches continues to expand E. coli's capabilities as a microbial cell factory for sustainable chemical production.

For researchers selecting a metabolic engineering host, these data support E. coli as the preferred platform for most bacterial-targeted pathways and non-native chemicals, particularly when high titer, rate, and yield are critical for economic viability.

The selection of an appropriate microbial host is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering, profoundly influencing the efficiency, yield, and economic viability of producing high-value compounds like terpenoids and heme. Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae emerge as the predominant workhorses, each presenting a distinct profile of physiological and metabolic characteristics. This guide provides a structured comparison of these two chassis organisms, focusing on the engineering strategies required to rewire their central metabolism for enhanced production. We objectively evaluate their performance through quantitative data, detail key experimental protocols, and visualize the critical metabolic pathways, offering researchers a evidence-based framework for host selection and engineering.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Metrics

The performance of engineered E. coli and S. cerevisiae strains can be evaluated based on key metrics such as product titer, yield, and productivity. The following tables summarize comparative data for terpenoid and heme production.

Table 1: Comparison of Host Organisms for Terpenoid Production

| Terpenoid / Metric | Engineered E. coli Performance | Engineered S. cerevisiae Performance | Key Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Farnesene (Titer) | 1.3 g/L [46] | Information missing | Enhanced supply of isoprene precursors (IPP/DMAPP) |

| General Higher Alcohols (Yield) | Higher potential yield from flexible central metabolism [17] | Lower yield due to structurally limited flexibility of central metabolism [17] | Gene deletion to restrict metabolic states in E. coli; Gene supplementation from E. coli in S. cerevisiae |

| Artemisinic Acid (Titer) | Not typically produced | 25 g/L [47] | Heavy pathway engineering and precursor supply optimization |

Table 2: Comparison of Host Organisms for Heme Production

| Metric | Engineered E. coli Performance | Engineered S. cerevisiae Performance | Key Challenges & Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Reported Titer | 1.03 g/L (Fed-batch) [48] | 380.5 mg/L (Fed-batch); 4.6 mg/L (Novel CPD pathway in lab strain) [48] | Endotoxin concern in E. coli [48] |

| Native Pathway Thermodynamics | Information missing | Thermodynamically less favorable Protoporphyrin-Dependent (PPD) pathway [48] | Introduction of bacterial Coproporphyrin-Dependent (CPD) pathway in yeast [48] |

| Pathway Compartmentalization | Cytoplasmic (unified pathway) [48] | Bifurcated between cytosol and mitochondria [48] | Mitochondrial compartmentalization via MTS tags in yeast [48] |

| Robustness / GRAS Status | Non-GRAS; endotoxin producer [48] [47] | GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) [47] | Preferred for food and pharmaceutical applications [47] |

Experimental Protocols & Engineering Workflows

Protocol: Modular Pathway Rewiring in S. cerevisiae

The Modular Pathway Rewiring (MPR) strategy is a systematic approach for optimizing complex metabolic pathways, as demonstrated for L-ornithine overproduction [49]. This methodology is highly applicable to pathways for terpenoids and heme.

- Pathway Deconstruction into Modules: Re-cast the target biosynthetic pathway from glucose into discrete, manageable modules. For example:

- Module 1 (Consumption): Contains reactions that degrade or consume the target product.

- Module 2 (Synthesis): Contains all reactions converting a key precursor to the target product.

- Module 3 (Precursor Supply): Includes upstream pathways (e.g., glucose uptake, glycolysis, TCA cycle) for generating precursors.

- Sequential Module Optimization: Begin by engineering the downstream modules before moving upstream.

- Knock out degradation genes in Module 1 (e.g., car2Δ for ornithine).

- Amplify expression of biosynthesis genes in Module 2. Use strong, constitutive promoters (e.g., PGPD).

- Enhance precursor supply in Module 3 by overexpressing key enzymes (e.g., tktA for E4P supply) or attenuating competing pathways (e.g., the Crabtree effect).

- Strain Construction & Evaluation: Construct and evaluate a large number of strains (e.g., >64), each with different combinations of genetic modifications across the modules. Shake-flask and controlled fed-batch fermentations are used to assess performance (titer, yield, productivity).

Protocol: Compartmentalization of Heme Biosynthesis in Yeast

A key limitation for heme production in S. cerevisiae is the bifurcation of its biosynthetic pathway between the cytosol and mitochondria [48]. The following protocol details a strategy to overcome this via compartmentalization.

- Mitochondrial Targeting:

- Amplify genes encoding for the first four enzymes in the heme pathway (HEM2, HEM3, HEM4, HEM12).

- Fuse distinct Mitochondria-Targeting Sequences (MTS) to the N-terminus of each enzyme to avoid homologous recombination. For example, use MTS1 from MMF1 for HEM2 and MTS4 from HSP60 for HEM3 [48].

- Clone these MTS-enzyme fusions under the control of a strong constitutive promoter (e.g., PGPD) in a high-copy plasmid or integrate into the genome.

- Introducing the CPD Pathway:

- Source a hemQ gene from a GRAS bacterium like Corynebacterium glutamicum (hemQCg).

- Fuse an MTS (e.g., MTS9) to the N-terminus of hemQ and express it in the strain from step 1.

- Chaperone Co-expression:

- To improve the functional expression of bacterial HemQ, co-express the Group-I HSP60 chaperonins (GroEL and GroES) from E. coli [48].

- Validation:

- Confirm mitochondrial localization via western blot analysis of fractionated mitochondria.

- Quantify heme titer in the engineered strain compared to the wild-type and control strains using spectrophotometric or HPLC methods.

Metabolic Pathway Diagrams and Engineering Strategies

Terpenoid Biosynthesis and Engineering

The biosynthesis of all terpenoids originates from the universal five-carbon precursors Isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). Two primary pathways, the Mevalonate (MVA) and Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) pathways, produce these precursors [46].

Diagram Title: The Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway for Terpenoid Biosynthesis in Yeast

Heme Biosynthesis and Compartmentalization Engineering

The canonical heme pathway in S. cerevisiae is bifurcated and thermodynamically less favorable than the bacterial CPD pathway. The following diagram illustrates the native state and a compartmentalization engineering strategy [48].

Diagram Title: Engineering a Unified Mitochondrial Heme Pathway in S. cerevisiae

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Engineering in S. cerevisiae

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial Targeting Sequences (MTS) | Directs nuclear-encoded proteins to the mitochondrial matrix for pathway compartmentalization. | MTS1 (from MMF1), MTS4 (from HSP60), MTS17 (from COX4), MTS12 (from LPD1) [48]. |

| Strong Constitutive Promoters | Drives high-level, constant expression of pathway genes. | GPD (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) promoter [48]. |

| Heterologous Enzymes | Completes non-native, thermodynamically favorable pathways or compensates for host limitations. | HemQ from Corynebacterium glutamicum (hemQCg) for the CPD heme pathway [48]. |

| Molecular Chaperones | Improves functional folding and stability of heterologous proteins, especially from bacteria. | E. coli GroEL/GroES (Group-I HSP60) [48]. |

| Modular Pathway Assembly Tools | Facilitates the construction and optimization of multi-gene pathways through standardized parts. | DNA assembly and Modular Pathway Engineering (MOPE) methods [49]. |

| Genome Editing Systems | Enables precise gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and other genomic modifications. | CRISPR-Cas systems for S. cerevisiae [47]. |

| Bima SA | Bima SA, MF:C26H39NO6, MW:461.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mebeverine alcohol | Mebeverine alcohol, CAS:14367-47-6, MF:C16H27NO2, MW:265.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The field of metabolic engineering is increasingly shifting from single-strain approaches to multi-strain microbial consortia that leverage division of labor (DoL) to overcome fundamental biological constraints. This architectural innovation addresses critical challenges including metabolic burden, enzyme promiscuity, and toxic intermediate accumulation that frequently limit the productivity of engineered microbial systems [18] [50]. By distributing complex biosynthetic pathways across specialized microbial strains, consortia achieve a metabolic division of labor that mirrors the efficiency of natural microbial communities and eukaryotic compartmentalization [51].