Engineered Streptomyces Hosts for Heterologous Expression: A Comprehensive Guide for Natural Product Discovery and Optimization

The rediscovery of natural products as a critical source of new therapeutics has been greatly advanced by the development of engineered Streptomyces hosts for heterologous expression.

Engineered Streptomyces Hosts for Heterologous Expression: A Comprehensive Guide for Natural Product Discovery and Optimization

Abstract

The rediscovery of natural products as a critical source of new therapeutics has been greatly advanced by the development of engineered Streptomyces hosts for heterologous expression. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of why Streptomyces is the preferred chassis, the latest methodological advances in host engineering and platform development, essential troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome common expression barriers, and a comparative analysis of validated host strains. By integrating data from over 450 studies and the most recent technological breakthroughs, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to efficiently exploit microbial biosynthetic diversity for the discovery and production of novel, biologically potent metabolites.

Why Streptomyces? Unlocking the Genetic and Metabolic Potential of a Versatile Chassis

The Rediscovery of Natural Products as a Therapeutic Source

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance and the persistent challenges in treating complex diseases have catalyzed a renaissance in natural product (NP) research. Historically, NPs have been an unparalleled source of drug leads, characterized by their structural complexity and diverse bioactivities [1] [2]. However, traditional discovery approaches have been plagued by high rates of rediscovery and the inability to access the vast majority of biosynthetic potential encoded in microbial genomes [1].

Advances in genome sequencing have revealed a critical paradox: while actinobacterial genomes are rich in biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), the majority of these clusters remain silent or "cryptic" under standard laboratory conditions [1] [3]. To unlock this hidden potential, the field has pivoted toward heterologous expression strategies, with engineered Streptomyces species emerging as the predominant host platform [1]. This whitepaper examines how the development of specialized Streptomyces chassis strains is fueling the rediscovery of natural products as a therapeutic source, enabling researchers to access previously inaccessible chemical diversity.

Streptomyces as a Versatile Heterologous Host

Innate Advantages for Natural Product Production

Streptomyces species possess several intrinsic biological properties that make them ideal chassis for heterologous BGC expression. Their high GC content is genomically compatible with many actinobacterial BGCs, reducing the need for extensive codon optimization [1]. These organisms have evolved sophisticated regulatory networks and possess the necessary precursor supply and enzymatic machinery to produce complex polyketides and non-ribosomal peptides [1]. Furthermore, Streptomyces exhibit remarkable tolerance to cytotoxic compounds, making them suitable for producing bioactive molecules that would inhibit growth in simpler hosts [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Heterologous Expression Trends

Analysis of over 450 peer-reviewed studies published between 2004 and 2024 reveals a clear upward trajectory in the use of Streptomyces for heterologous BGC expression [1]. The period from 2016 to 2021 saw nearly 90 relevant publications per three-year interval, reflecting growing methodological maturity and successful applications [1].

Table 1: Preferred Streptomyces Host Strains for Heterologous Expression

| Host Strain | Key Genetic Features | Advantages | Production Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. coelicolor M1152 | Deletion of four native BGCs (act, red, cpk, cda); rpoB mutation [3] | Well-characterized genetics; 20-40 fold yield increases reported [3] | Benchmark for various polyketides [3] |

| S. lividans TK24 | SLP2 and SLP3 plasmid-free [3] | Low protease activity; accepts methylated DNA [3] | Daptomycin, Mithramycin A [3] |

| S. albus J1074 | Minimized genome (Del14 strain) [3] | Clean metabolic background; reduced interference [3] | Nybomycin [4] |

| S. sp. A4420 CH | Deletion of 9 native PKS BGCs [3] | Rapid growth; high sporulation rate; superior polyketide production [3] | Streptazolin; multiple tested polyketides [3] |

| S. explomaris | Wild-type marine isolate [4] | Compatible with marine feedstocks; high precursor flux [4] | Nybomycin (57 mg/L) [4] |

Engineering Advanced Streptomyces Chassis Strains

Genome Minimization and Background Reduction

A fundamental strategy in chassis development involves the targeted deletion of native BGCs to eliminate competitive metabolic pathways and reduce background interference. The S. coelicolor M1146 strain was created by removing actinorhodin, prodiginine, coelimycin, and calcium-dependent antibiotic BGCs [3]. Similarly, the S. lividans ΔYA11 strain has nine metabolically active BGCs deleted, resulting in superior production levels for heterologous metabolites while maintaining robust growth [3]. The S. albus Del14 strain represents a more extensive minimization with 15 native secondary metabolite pathways removed [3].

Enhanced Genetic Integration Systems

Chromosomal integration of heterologous BGCs has been revolutionized by recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) systems. The Micro-HEP platform employs modular RMCE cassettes (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, and phiBT1-attP) for precise BGC integration without plasmid backbone incorporation [5]. This system enables copy number optimization, as demonstrated with the xiamenmycin BGC, where increasing copy numbers directly correlated with yield improvements [5].

Table 2: Genetic Toolkits for Streptomyces Engineering

| Tool Category | Specific Elements | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinase Systems | Cre-loxP, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, phiC31-att [5] | Site-specific integration; marker-free genome editing; RMCE |

| Promoter Systems | ermEp, kasOp [1] | Strong constitutive expression |

| Inducible Systems | Tetracycline, thiostrepton, cumate-responsive [1] | Temporal control of gene expression |

| DNA Assembly Tools | TAR, ExoCET, Redα/Redβ recombineering [1] [5] | BGC capture and modification in E. coli |

| Conjugation Systems | oriT-containing plasmids with Tra proteins [5] | Efficient BGC transfer from E. coli to Streptomyces |

Experimental Workflows for Heterologous Expression

BGC Capture and Engineering Pipeline

The foundational workflow for heterologous expression involves four critical stages: BGC identification, capture, modification, and host integration [5]. Bioinformatic tools like antiSMASH enable genome mining to predict and analyze BGCs of interest [5]. Cloning strategies such as transformation-associated recombination (TAR) and exonuclease combined with RecET recombination (ExoCET) allow direct capture of large BGCs from genomic DNA [1] [5]. For BGC modification, the Red recombination system (mediated by λ phage-derived recombinases Redα/Redβ) enables precise DNA editing using short homology arms in E. coli [5].

Modular Engineering of Complex Pathways

For exceptionally large or complex BGCs, modular engineering approaches have proven successful. In the case of the 33-gene doxorubicin BGC, researchers grouped genes responsible for each biosynthetic stage into six distinct functional subclusters: polyketide backbone synthesis, anthracyclinone formation, sugar moiety biosynthesis, glycosylation, post-modification, and regulation/resistance [6]. This systematic modularization identified the glycosylation and post-modification subcluster as having the greatest capacity to boost production, ultimately resulting in a 15-fold increase in doxorubicin yield when introduced into S. albus J1074 [6].

Case Studies in Production Optimization

Tacrolimus Production inS. tsukubaensis

Tacrolimus (FK506), an important immunosuppressive drug, exemplifies successful production enhancement through combined strain and process engineering. Researchers developed a high-yield mutant, 2108N-1-4, through natural isolation and physical mutagenesis [7]. Transcriptome analysis identified the regulatory gene fkbN as a key modification target. Engineered strains carrying three copies of fkbN achieved tacrolimus yields of 1342 mg/L [7]. To address end-product inhibition in late fermentation, adsorbents (LX-60 and β-cyclodextrin) were added, further increasing yields to 3746 mg/L in shake flasks and 3639 mg/L in a 5 L fermenter—the highest production yield reported to date [7].

Nybomycin Production inS. explomaris

Nybomycin, a reverse antibiotic with activity against fluoroquinolone-resistant bacteria, presented production challenges with native producers yielding less than 2 mg/L [4]. Heterologous expression in S. explomaris identified this marine strain as a superior host. Transcriptomic analysis revealed transcriptional repression and precursor limitation as key bottlenecks [4]. Sequential engineering included:

- Deletion of repressors nybW and nybX (NYB-1 strain)

- Overexpression of precursor supply genes (zwf2, nybF)

The resulting NYB-3B strain achieved 57 mg/L nybomycin—a fivefold increase over previous benchmarks [4]. Furthermore, cultivation on brown seaweed hydrolysates demonstrated compatibility with sustainable feedstocks, achieving 14.8 mg/L without nutrient supplementation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Streptomyces Heterologous Expression

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) | Bacterial Strain | Donor for biparental conjugation with Streptomyces [5] |

| Micro-HEP Platform | Engineered System | Bifunctional E. coli strains and optimized S. coelicolor chassis for BGC modification and expression [5] |

| pSC101-PRha-αβγA-PBAD-ccdA | Plasmid Vector | Temperature-sensitive plasmid with rhamnose-inducible Redαβγ recombination system [5] |

| RMCE Cassettes | Genetic Parts | Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, phiBT1-attP modules for precise chromosomal integration [5] |

| antiSMASH | Bioinformatics Tool | Genome mining for BGC identification and analysis [5] [3] |

| Rjpxd33 | Rjpxd33, MF:C71H107N15O18S, MW:1490.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Argimicin B | Argimicin B, MF:C32H62N11O9+, MW:744.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The rediscovery of natural products as a therapeutic source is intrinsically linked to advances in Streptomyces metabolic engineering. Future efforts will focus on expanding the panel of specialized chassis strains, with recent additions like Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH demonstrating the value of exploring phylogenetically diverse isolates [3]. The integration of artificial intelligence for predicting BGC expression and optimizing genetic design represents the next frontier [2].

The continued development of synthetic biology tools—including modular regulatory elements, advanced recombinase systems, and precision genome editing—will further streamline heterologous expression workflows [1] [5]. Additionally, the application of systems metabolic engineering approaches that combine multi-omics analysis with rational strain design will address persistent challenges in precursor supply and metabolic burden [8] [4].

In conclusion, engineered Streptomyces hosts have transformed natural product discovery by providing a versatile platform for accessing silent biosynthetic potential. Through continued innovation in chassis development, genetic toolkits, and bioprocess optimization, these remarkable organisms will remain central to unlocking nature's chemical diversity for therapeutic applications.

Intrinsic Advantages of Streptomyces as a Heterologous Host

The discovery of novel natural products (NPs) has been revolutionized by heterologous expression strategies, with Streptomyces species emerging as the predominant microbial chassis. This in-depth technical guide examines the intrinsic advantages of Streptomyces hosts, focusing on their genomic compatibility, metabolic capabilities, and physiological traits that facilitate successful heterologous production of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Within the broader context of engineered Streptomyces platforms for heterologous expression research, we present quantitative data analyses, detailed experimental methodologies, and essential research reagents that enable researchers to harness the full potential of these versatile hosts for drug discovery and natural product research.

Natural products represent an invaluable source of bioactive compounds, characterized by structural complexity and high specificity for biological targets, offering broader chemical space than most synthetic molecules [1]. The rediscovery of NPs as a critical source of new therapeutics has been greatly advanced by developing heterologous expression platforms for BGCs [1]. Among these, Streptomyces species have emerged as the most widely used and versatile chassis for expressing complex BGCs from diverse microbial origins [1] [9]. Comprehensive analysis of over 450 peer-reviewed studies published between 2004 and 2024 reveals clear trends in the adoption of Streptomyces hosts across research laboratories worldwide [1].

This technical guide examines the fundamental advantages that position Streptomyces as preferred heterologous hosts, with particular emphasis on their application within engineered host systems for discovering and producing novel bioactive compounds. We integrate recent technological advances with practical case studies and experimental protocols to provide researchers with a comprehensive resource for leveraging Streptomyces platforms in natural product research and drug development.

Core Advantages of Streptomyces Hosts

Streptomyces species possess a unique combination of biological traits that make them exceptionally suitable for heterologous expression of secondary metabolite pathways. The table below summarizes these key advantages and their practical implications for heterologous expression.

Table 1: Intrinsic Advantages of Streptomyces as Heterologous Hosts

| Advantage Category | Specific Features | Impact on Heterologous Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Compatibility | High GC content; similar codon usage bias with actinobacterial BGCs [1] | Reduces need for extensive gene refactoring and codon optimization [10] |

| Metabolic Capacity | Native ability to produce complex polyketides and non-ribosomal peptides; diverse precursor pool [1] [10] | Supports large, modular biosynthetic pathways; provides essential cofactors and tailoring enzymes [1] |

| Protein Folding Environment | Oxidative extracellular milieu promotes disulfide bond formation; compatible cytoplasmic redox state [10] | Enables correct folding of complex eukaryotic proteins and large PKS/NRPS enzymes [10] |

| Regulatory Systems | Sophisticated native regulatory networks; pathway-specific regulators, sigma factors, global transcriptional regulators [1] | Allows efficient transcription/translation of heterologous BGCs, especially from actinobacterial sources [1] |

| Physiological Tolerance | Native resistance mechanisms; tolerance to cytotoxic secondary metabolites [1] | Enables production of bioactive compounds that inhibit growth in simpler hosts [1] |

| Secretion Capability | Efficient protein secretion systems; Gram-positive structure without outer membrane [10] | Simplifies downstream purification; facilitates proper disulfide bond formation [10] |

| Industrial Scalability | Well-established fermentation processes; robust growth characteristics [1] | Smooth transition from lab-scale production to industrial biomanufacturing [1] |

The exceptional capability of Streptomyces for heterologous expression stems from their natural biological role as prolific producers of secondary metabolites. Approximately 45% of known bioactive microbial natural products originate from actinomycetes, predominantly Streptomyces [5]. Genomic analyses reveal that Streptomyces strains typically contain 20-40 BGCs on average, with some strains possessing up to 70 cryptic BGCs [11] [12], reflecting their inherent metabolic complexity and biosynthetic potential.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Standard Heterologous Expression Workflow

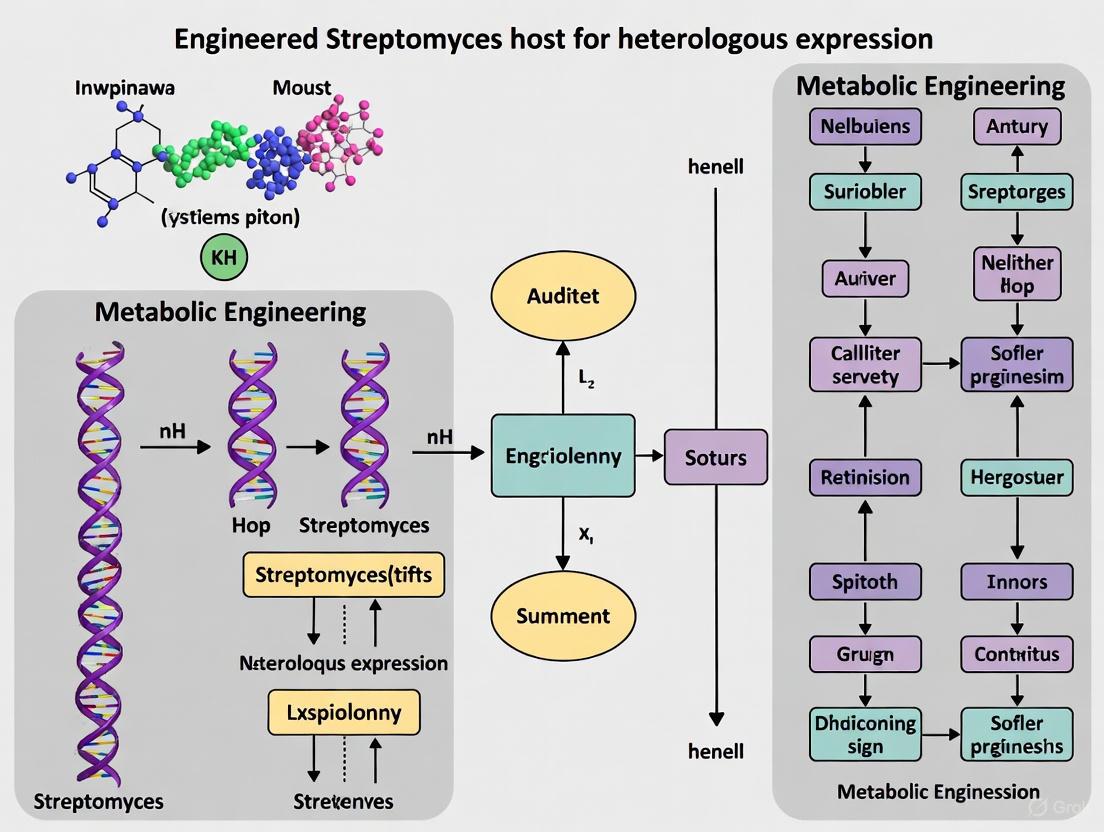

The general workflow for heterologous expression in Streptomyces involves multiple standardized steps, from BGC identification to compound characterization. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive process:

Diagram 1: Heterologous Expression Workflow

Chassis Engineering and Optimization

Engineering optimal Streptomyces chassis involves strategic genetic modifications to enhance heterologous expression capacity. The following diagram outlines key engineering strategies:

Diagram 2: Chassis Engineering Strategies

Detailed Experimental Protocols

BGC Capture via ExoCET Cloning

Purpose: To capture large biosynthetic gene clusters (typically 20-80 kb) from genomic DNA for heterologous expression [5].

Materials:

- Genomic DNA from donor strain

- E. coli GB2005 or GB2006 strains [5]

- ExoCET reaction reagents (recET recombination system)

- Appropriate selection antibiotics

- Electroporation equipment

Procedure:

- Prepare targeting vector: Design and construct a vector containing homology arms (approximately 500 bp) flanking the target BGC, along with necessary selection markers and origin of transfer (oriT) for conjugation.

- Isolate high-quality genomic DNA: Extract intact genomic DNA from the donor strain using standard actinomycete DNA extraction protocols.

- Perform ExoCET reaction: Mix the targeting vector and genomic DNA in a 1:5 molar ratio with the RecET recombination system components. Incubate at 37°C for 60-90 minutes to allow homologous recombination.

- Transform into E. coli: Electroporate the recombination mixture into appropriate E. coli strains (e.g., GB2005) and plate on selective media.

- Screen positive clones: Verify correct assembly by colony PCR and restriction digest analysis of plasmid DNA from selected colonies.

- Sequence validation: Confirm BGC integrity by sequencing across all junction sites and potential problematic regions.

Technical Notes: The ExoCET system enables direct cloning from genomic DNA without the need for library construction, significantly reducing the time required for BGC capture. E. coli strains GB2005 and GB2006 show superior stability for repeat sequences compared to traditional ET12567 (pUZ8002) systems [5].

Chassis Strain Development via CRISPR-Cas9

Purpose: To generate clean deletions of native BGCs in Streptomyces chassis strains to minimize metabolic burden and prevent interference with heterologous expression [12].

Materials:

- Streptomyces spores (e.g., S. griseofuscus DSM 40191)

- CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid system for Streptomyces

- Donor DNA fragments for homologous recombination

- Appropriate antibiotics for selection

- Protoplast preparation and regeneration media

Procedure:

- Design gRNA targets: Identify 20-bp protospacer sequences adjacent to PAM sites flanking the target BGC for deletion.

- Construct CRISPR plasmid: Clone two gRNA expression cassettes targeting upstream and downstream regions of the BGC into a Streptomyces CRISPR-Cas9 vector.

- Prepare donor DNA: Synthesize or amplify linear DNA fragments containing homologous arms (800-1000 bp) with the desired deletion junction.

- Protoplast transformation: Prepare protoplasts from fresh Streptomyces spores, co-transform with CRISPR plasmid and donor DNA using PEG-mediated transformation.

- Selection and screening: Plate on regeneration media with appropriate antibiotics. Screen for double-crossover events by colony PCR.

- Cure CRISPR plasmid: Remove the CRISPR plasmid through non-selective passage and verify by sensitivity to corresponding antibiotics.

- Phenotypic validation: Confirm deletion by loss of native metabolite production and assess growth characteristics.

Technical Notes: This protocol was successfully used to generate S. griseofuscus DEL1 (cured of two native plasmids) and DEL2 (additional deletion of pentamycin and NRPS BGCs), resulting in approximately 5.19% genome reduction with improved growth characteristics [12].

ARTP Mutagenesis for Activation of Silent BGCs

Purpose: To generate random mutations in Streptomyces strains using Atmospheric Room-Temperature Plasma (ARTP) to activate silent or cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters [11].

Materials:

- ARTP mutagenesis system (SiQingYuan Inc., Wuxi, China)

- Fresh spore suspension (10â·-10⸠CFU/mL) in sterile saline

- Helium gas (high purity, ≥99.999%)

- ISP2 agar plates

- Antibiotic activity screening assays

Procedure:

- Prepare spore suspension: Harvest spores from mature Streptomyces cultures (10-14 days), disrupt spore chains using glass beads, and adjust concentration to 10â·-10⸠CFU/mL.

- Optimize treatment conditions: Perform preliminary experiments to determine optimal exposure time (typically 30-180 seconds) using 10 μL of spore suspension.

- ARTP treatment: Expose spore samples to plasma jet under standard conditions (110 W input power, 2 mm distance, 10 slpm helium flow rate).

- Determine lethality rate: Plate diluted samples on ISP2 media and calculate lethality rate: (A-B)/A × 100%, where A is control colony count and B is treated colony count.

- Screen for activated mutants: Plate treated spores at appropriate dilution to obtain isolated colonies. Screen for antimicrobial activity against indicator strains.

- Iterative mutagenesis: Subject positive mutants to additional rounds of ARTP treatment to enhance desired phenotypes.

- Multi-omics validation: Analyze promising mutants using comparative transcriptomics and metabolomics to confirm activation of target BGCs.

Technical Notes: Optimal lethality rates for ARTP mutagenesis in Streptomyces typically range from 85-95%. In one study, 75-second exposure resulted in 94% lethality with 40.94% mutation positive rate. Three iterative cycles increased the proportion of mutants with antibacterial activities by 75% [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential research reagents and their applications in Streptomyces heterologous expression studies are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Streptomyces Heterologous Expression

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning Systems | ExoCET [5], TAR [1], Redα/Redβ/Redγ [5] | Capture and modify large BGCs; facilitate homologous recombination in E. coli |

| Conjugation Strains | E. coli GB2005/GB2006 [5], ET12567(pUZ8002) [5] | Transfer BGC constructs from E. coli to Streptomyces via intergeneric conjugation |

| Integrative Systems | PhiC31-attB [5], Vika-vox [5], Dre-rox [5] | Site-specific integration of BGCs into Streptomyces chromosomes |

| Promoter Systems | ermEp, kasOp [1], tetracycline-inducible, thiostrepton-inducible [1] | Control expression of heterologous genes; constitutive and inducible options |

| Chassis Strains | S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 [5], S. griseofuscus DEL2 [12], S. aureofaciens Chassis2.0 [13] | Engineered hosts with deleted native BGCs and enhanced heterologous expression |

| Mutagenesis Systems | ARTP [11], CRISPR-Cas9 [12], CRISPR-cBEST [12] | Generate mutations for strain improvement or activate silent BGCs |

Case Studies and Applications

Micro-HEP Platform Validation

The Microbial Heterologous Expression Platform (Micro-HEP) represents a recent advancement in Streptomyces-based expression systems. This platform employs specialized E. coli strains for BGC modification and conjugation transfer, coupled with an optimized S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 chassis strain with four deleted endogenous BGCs and multiple recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites [5].

When tested with the xiamenmycin (anti-fibrotic compound) BGC, the platform demonstrated a direct correlation between gene cluster copy number and product yield. Integration of 2-4 copies of the xim BGC via RMCE resulted in progressively increasing xiamenmycin production [5]. The system also successfully expressed the griseorhodin BGC, leading to the discovery of a new compound, griseorhodin H, highlighting the platform's utility for novel natural product discovery [5].

High-Efficiency T2PKS Production in Engineered Chassis

Recent work developing specialized chassis for type II polyketide (T2PKS) production demonstrates the importance of host selection. Researchers identified S. aureofaciens J1-022, a high-yield chlortetracycline producer, as an optimal chassis for T2PKS synthesis [13].

After deleting two endogenous T2PKS gene clusters to create Chassis2.0, the platform demonstrated remarkable versatility:

- Oxytetracycline production: 370% increase compared to commercial production strains [13]

- Tri-ring T2PKS: Successful production of actinorhodin and flavokermesic acid [13]

- Novel compound discovery: Activation of a previously unidentified pentangular T2PKS BGC produced structurally distinct TLN-1 [13]

This case study underscores how industrial high-yield strains can be repurposed as versatile chassis for homologous natural product classes, leveraging their optimized precursor supply and cellular machinery.

Streptomyces species provide an unparalleled platform for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters, combining genomic compatibility, metabolic versatility, and physiological advantages that are particularly suited for complex natural product biosynthesis. The continued development of sophisticated genetic tools, specialized chassis strains, and integrated platforms like Micro-HEP is expanding the boundaries of what can be achieved through heterologous expression strategies.

As the field advances, the strategic engineering of Streptomyces hosts with enhanced precursor supplies, reduced native metabolic burdens, and optimized regulatory networks will further solidify their position as the chassis of choice for natural product discovery and engineering. These developments are particularly crucial in addressing the ongoing need for novel therapeutic compounds to combat emerging infectious diseases and drug-resistant pathogens.

Quantitative Analysis of Two Decades of Expression Trends

This whitepaper presents a comprehensive quantitative analysis of heterologous expression trends in Streptomyces hosts over the past two decades (2004-2024). Through systematic evaluation of over 450 peer-reviewed studies, we identify key technological advances, host strain preferences, and expression success factors that have shaped this rapidly evolving field. The data reveal a clear trajectory toward specialized chassis development, refined genetic toolkits, and sophisticated engineering strategies that collectively enhance our capacity to access microbial natural products. Within the context of engineered Streptomyces hosts, this analysis provides researchers with validated experimental frameworks, quantitative performance metrics, and strategic insights to guide future platform development and natural product discovery efforts.

The rediscovery of natural products (NPs) as a critical source of new therapeutics has been greatly advanced by the development of heterologous expression platforms for biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Among these, Streptomyces species have emerged as the most widely used and versatile chassis for expressing complex BGCs from diverse microbial origins [1]. This analysis covers two decades of technological evolution (2004-2024), during which heterologous expression has transformed from a specialized genetic tool to a central platform for natural product discovery and engineering.

The diminishing returns from conventional bioactivity-guided screening approaches, coupled with advances in genome sequencing, have revealed a vast reservoir of cryptic and silent BGCs within actinobacterial genomes [1]. Unlocking this hidden biosynthetic potential requires robust heterologous expression platforms capable of activating and producing these compounds in scalable quantities. This quantitative review examines how Streptomyces-based expression systems have addressed this challenge, focusing on empirical trends, host engineering strategies, and methodological innovations that define the current state of the field.

Quantitative Trends in Heterologous Expression (2004-2024)

Publication Landscape and Temporal Trends

Analysis of publication patterns reveals a clear upward trajectory in heterologous expression research over the past two decades. The early period (2004-2006) showed relatively modest publication numbers, primarily due to technical limitations in genome sequencing, cloning, and host engineering. From 2007-2012, a steady increase occurred, driven by early genome mining efforts and developing genetic tools for Streptomyces and other actinomycetes. The period 2013-2018 witnessed a sharp rise in publications, coinciding with the expansion of synthetic biology platforms and improved BGC capture methods. Publication activity peaked between 2016-2021, with nearly 90 articles published in each 3-year interval [1].

Table 1: Chronological Distribution of Heterologous Expression Studies in Streptomyces (2004-2024)

| Time Period | Publication Count | Key Technological Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| 2004-2006 | Low | Cosmid/BAC libraries, early genome sequencing |

| 2007-2012 | Steady increase | Early genome mining, improved genetic tools |

| 2013-2018 | Sharp rise | Synthetic biology, TAR/CATCH cloning |

| 2019-2024 | High activity peak | CRISPR engineering, specialized chassis |

Quantitative analysis of host strain utilization reveals distinct preferences within the research community. The data-driven overview of expression trends across BGC types, donor species, and host strain preferences offers the first quantitative perspective on how this field has evolved [1]. Model strains such as S. coelicolor and S. lividans have been widely adopted due to their well-characterized genetics and established manipulation protocols. However, recent trends show increasing diversification toward specialized chassis strains engineered for specific applications.

Table 2: Heterologous Host Performance Comparison for Polyketide BGC Expression

| Host Strain | BGCs Tested | Successful Expressions | Relative Yield Range | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH | 4 | 4 (100%) | High | Deleted 9 native PKS BGCs, superior sporulation and growth |

| S. coelicolor M1152 | 4 | Variable | Medium | rpoB/rpsL mutations, well-characterized |

| S. lividans TK24 | 4 | Variable | Low-medium | Low protease activity, accepts methylated DNA |

| S. albus J1074 | 4 | Variable | Variable | Minimized genome (Del14 strain) |

| S. griseofuscus DEL2 | 1 (actinorhodin) | 1 (100%) | Observable | 5.19% genome reduction, faster growth |

Performance comparisons demonstrate that the choice of heterologous host significantly impacts expression success. In one systematic study evaluating four distinct polyketide BGCs across different hosts, only the engineered Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain demonstrated the capability to produce all metabolites under every condition, outperforming its parental strain and other tested organisms [3]. This highlights the importance of host selection and the value of expanding the repertoire of available chassis strains.

Key Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Expression

Chassis Development and Genome Reduction

Strategic elimination of native biosynthetic pathways represents a cornerstone of chassis development. This approach minimizes metabolic competition for precursors and reduces background interference that complicates metabolite detection. Engineering efforts have progressively targeted multiple native BGCs:

- S. coelicolor M1146: Deletion of actinorhodin, prodiginine, coelimycin, and calcium-dependent antibiotic pathways [3]

- S. coelicolor M1152/M1154: Introduction of rpoB (rifampicin resistance) and rpsL (streptomycin resistance) mutations, resulting in 20-40-fold yield increases for some natural products [3]

- S. lividans ΔYA11: Deletion of nine metabolically active BGCs with additional attB integration sites, showing superior production compared to progenitor TK24 [3]

- S. albus Del14: Elimination of 15 native secondary metabolite pathways [3]

- S. griseofuscus DEL2: Deletion of pentamycin BGC, unknown NRPS BGC, and curing of two native plasmids (≈500 kbp, 5.19% genome reduction), resulting in faster growth [12]

The Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain exemplifies the modern approach to chassis development, with deletion of 9 native polyketide BGCs leading to consistent sporulation and growth that surpasses most existing Streptomyces-based chassis strains in standard liquid growth media [3].

Genetic Tool Development and Integration Strategies

Advanced genetic tools have dramatically accelerated heterologous expression capabilities. The development of modular recombination systems has enabled more sophisticated engineering approaches:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for heterologous BGC expression in engineered Streptomyces hosts, highlighting key technological advancements across the process.

Recent platform developments like Micro-HEP (microbial heterologous expression platform) demonstrate the integration of multiple advanced technologies. This system employs versatile E. coli strains capable of both modification and conjugation transfer of foreign BGCs, combined with optimized chassis Streptomyces strains for expression [5]. The stability of repeat sequences in these specialized E. coli strains was superior to that of the commonly used conjugative transfer system E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) [5].

Integration strategy significantly influences expression levels. The Micro-HEP platform tested BGCs for the anti-fibrotic compound xiamenmycin and griseorhodins, demonstrating that two to four copies of the xim BGC integrated by recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) showed increasing yield with copy number [5]. Modular RMCE cassettes (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, and phiBT1-attP) enable efficient integration of BGCs into chassis strains with defined metabolic backgrounds [5].

Experimental Protocols for Heterologous Expression

BGC Capture and Engineering Methods

The cloning of biosynthetic gene clusters has evolved significantly from traditional library-based approaches to direct capture methods:

- Transformation-associated recombination (TAR): Utilizes yeast homologous recombination system to capture large DNA fragments directly from genomic DNA [1] [14]

- Cas9-assisted targeting of chromosome segments (CATCH): Employs CRISPR-Cas9 to precisely excise target BGCs from native genomes [1]

- Exonuclease combined with RecET recombination (ExoCET): Combines exonuclease treatment with bacterial recombinases for efficient BGC capture [5]

For BGC engineering, the Red recombination system mediated by λ phage-derived recombinases Redα/Redβ enables precise DNA editing using short homology arms (50 bp) in Escherichia coli. Redα possesses 5'→3' exonuclease activity that generates 3' single-stranded DNA overhangs, while Redβ facilitates sequence-specific homologous recombination [5].

Conjugative Transfer and Strain Selection

Bacterial conjugation has become a cornerstone strategy for transferring large BGCs from E. coli to Streptomyces. The process typically utilizes E. coli ET12567 harboring the IncP plasmid pUZ8002 as a donor for biparental conjugation with Streptomyces [15] [5]. However, limitations including low electroporation transformation efficiency and instability of repeated sequences have prompted development of improved conjugation systems [5].

Host selection should consider multiple factors, including:

- Genetic tractability and transformation efficiency

- Compatibility with BGC GC-content and codon usage

- Native enzymatic capabilities for required post-assembly modifications

- Growth characteristics and fermentation scalability

- Background metabolite profile

Case studies demonstrate the critical importance of host selection. In one systematic effort to express the thiopeptide GE2270A, a statistically significant yield improvement was obtained in S. coelicolor M1146 through data-driven rational engineering of the BGC, including introducing additional copies of key biosynthetic and regulatory genes [15]. However, the highest production level remained 12× lower than published titres achieved in the natural producer and 50× lower than titres obtained using Nonomuraea ATCC 39727 as expression host [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Streptomyces Heterologous Expression

| Reagent/Strain | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 | Conjugative transfer of DNA to Streptomyces | Standard conjugation system, but shows limitations with large repetitive sequences [15] [5] |

| S. coelicolor M1146/M1152 | Model heterologous hosts | Well-characterized genetics, multiple engineered derivatives available [3] |

| S. lividans TK24 | Heterologous host | Accepts methylated DNA, low protease activity [3] |

| pSET152-based vectors | Integration vectors for BGC expression | phiC31-based integration, stable maintenance [5] |

| RMCE Cassettes (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, phiBT1-attP) | Site-specific integration | Modular systems for precise BGC integration without plasmid backbone [5] |

| Redα/Redβ/Redγ recombination system | BGC engineering in E. coli | Enables precise DNA editing with short homology arms [5] |

| Berkeleylactone E | Berkeleylactone E, MF:C20H32O7, MW:384.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Melithiazole N | Melithiazole N, MF:C20H24N2O5S2, MW:436.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks

Understanding the regulatory networks governing secondary metabolism in Streptomyces provides opportunities for enhancing heterologous expression. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analyses have revealed extensive regulatory complexity, with protein phosphorylation at Ser/Thr/Tyr modulating development and secondary metabolism [16].

Figure 2: Regulatory networks influencing secondary metabolism in Streptomyces, integrating phosphoproteomics insights.

Recent phosphoproteomic studies using immobilized zirconium (IV) affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry have mapped 361 phosphorylation sites (41% pSer, 56.2% pThr, 2.8% pTyr) and discovered four novel Thr phosphorylation motifs in S. coelicolor [16]. The identification of 154 novel phosphoproteins almost doubled the number of experimentally verified Streptomyces phosphoproteins, including cell division proteins (FtsK, CrgA) and specialized metabolism regulators (ArgR, AfsR, CutR, and HrcA) that were differentially phosphorylated in vegetative and antibiotic-producing sporulating stages [16].

Key regulatory proteins with experimentally validated phosphorylation include:

- FtsZ: Phosphorylation pleiotropically affects actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin production [16]

- DivIVA: Controls polar growth and hyphal branching [16]

- AfsR: Transcriptional activator of secondary metabolism, phosphorylated by AfsK [16]

- AfsK: Ser/Thr kinase that globally controls biosynthesis of several secondary metabolites [16]

These regulatory insights provide potential engineering targets for enhancing heterologous expression of BGCs in Streptomyces chassis strains.

Quantitative analysis of two decades of heterologous expression trends in Streptomyces reveals a field transformed by synthetic biology, genome engineering, and systems biology approaches. The progression from model strains to specialized chassis systems has significantly expanded our capacity to access diverse natural products. Current data indicate that even with advanced engineering, expression success remains variable, emphasizing the need for continued host diversification.

Future developments will likely focus on orthogonal regulatory systems, dynamic pathway control, and integration of machine learning approaches to predict optimal host-BGC pairings. The expanding toolkit of genetic parts, recombination systems, and analytical methods positions Streptomyces heterologous expression as a continuing cornerstone of natural product discovery and engineering. As these platforms mature, they will play an increasingly vital role in addressing the ongoing challenge of antibiotic resistance and unmet therapeutic needs.

Navigating Streptomyces Taxonomy and Genomic Diversity for Host Selection

The genus Streptomyces, a group of high G+C Gram-positive bacteria within the phylum Actinomycetota, represents one of the largest and most economically significant bacterial taxa [17] [18]. With approximately 700 species with validly published names and estimates suggesting the total number may be close to 1600, this genus exhibits remarkable genomic diversity [18] [19]. Streptomycetes are characterized by complex secondary metabolism, with between 5-23% (average: 12%) of their protein-coding genes dedicated to secondary metabolite biosynthesis [18]. This exceptional biosynthetic capacity, coupled with their ability to secrete proteins directly into the extracellular medium, has established Streptomyces species as premier chassis for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) and recombinant proteins [20] [21].

The genomic architecture of Streptomyces features large linear chromosomes ranging from 5.7-12.1 Mbps (average: 8.5 Mbps) with high GC content varying from 68.8-74.7% (average: 71.7%) [18] [21]. These genomes demonstrate remarkable plasticity, characterized by ancient single gene duplications, block duplications (mainly at chromosomal arms), and extensive horizontal gene transfer [18]. This plasticity enables rapid adaptation but also presents challenges for systematic host selection and engineering. The 95% soft-core proteome of the genus consists of approximately 2000-2400 proteins, while the pangenome remains open, continually expanding with the characterization of new strains [18].

Taxonomic Framework and Classification Systems

Historical Development and Current Challenges

The taxonomy of Streptomyces has evolved significantly since the genus was first described by Waksman and Henrici in 1943 [17] [18]. Early classification relied heavily on morphological characteristics such as spore color, spore chain morphology, melanoid pigment production, and utilization patterns of various carbon sources [19]. The International Streptomyces Project (ISP) established standardized descriptions for type strains of 458 Streptomyces species, creating an important foundation for taxonomic consistency [19].

Molecular approaches have progressively refined streptomycete taxonomy. The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis became standard in the 1980s, yet its resolution often proves insufficient for species delimitation within this genus [19]. Many Streptomyces species share >99% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity, necessitating additional methods for reliable classification [19]. The gold standard for species identification remains DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) with a 70% relatedness threshold, though this method is labor-intensive and has reproducibility challenges [19].

Modern Reclassification Efforts

Recent advances in whole genome sequencing have catalyzed significant reclassifications within the genus. In the past decade, approximately 34 Streptomyces species have been transferred to other genera including Kitasatospora, Streptacidiphilus, Actinoalloteichus, and newly proposed genera [19]. Additionally, 63 species were reclassified as later heterotypic synonyms of previously recognized species in 24 published reports [19]. These reclassifications have practical implications for host selection, as phylogenetic relationships often correlate with metabolic capabilities and genetic compatibility.

Table 1: Genomic Features of Selected Streptomyces Strains

| Strain | Chromosome Size (bp) | GC Content (%) | Protein-Coding Genes | Notable Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | 8,667,507 | 72.1 | 7,825 | Model organism for genetic studies | [18] |

| S. avermitilis MA-4680 | ~9,000,000 | ~70.5 | ~7,500 | Producer of avermectins | [3] [18] |

| S. scabiei | 10,100,000 | ~71.0 | 9,107 | Largest known Streptomyces genome | [18] |

| S. griseofuscus DSM 40191 | 8,721,740 | ~71.0 | ~7,500 | Contains 3 linear plasmids | [12] |

| S. cyaneofuscatus CTM50504 | 8,591,922 | 71.0 | 7,700 | Extracellular hydrolase producer | [22] |

| Streptomyces sp. A4420 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Engineered as polyketide chassis | [3] |

Genomic Diversity and Metabolic Potential

Chromosomal Organization and Plasticity

Streptomyces genomes exhibit distinctive architectural features that influence their utility as heterologous hosts. The chromosomes typically display functional organization, with evolutionarily stable genomic elements localized mainly at the central region, while evolutionarily unstable elements tend to occupy the chromosomal arms [18]. This arrangement positions essential housekeeping genes in the core region while allocating conditionally adaptive genes, including many BGCs, to the more plastic arms.

The number of BGCs per Streptomyces genome averages approximately 36.5 when analyzed by antiSMASH, reflecting the tremendous potential for diverse secondary metabolites and their biosynthetic enzymes [21]. This biosynthetic richness directly impacts host selection for heterologous expression, as native BGCs can compete for precursors, regulatory factors, and cellular machinery.

Comparative Genomic Insights

Comparative genomic analyses reveal both conserved and variable elements across Streptomyces species. A study comparing S. griseofuscus DSM40191 with model strains S. coelicolor A3(2) and S. venezuelae ATCC 10712 identified 3,918 genes shared across all three genomes (core genome), while S. griseofuscus shared an additional 937 and 522 genes with S. coelicolor and S. venezuelae, respectively [12]. Metabolic pathway analysis showed that S. griseofuscus possesses significantly more genes involved in terpenoid and polyketide metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and xenobiotics biodegradation compared to other strains [12].

Table 2: Metabolic Capabilities of Streptomyces Strains Based on Phenotype Microarray

| Metabolic Category | S. griseofuscus DSM40191 | S. coelicolor | S. venezuelae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Substrates Utilized | 171 | 172 | 117 |

| Carbon Sources | 64 | 72 | 61 |

| Nitrogen Sources | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| Unique Substrates | Ethanolamine, 2-aminoethanol, cytidine, thymidine, D-serine, D-threonine | 19 unique substrates | 7 unique substrates |

| Common Substrates (all three strains) | 90 substrates | 90 substrates | 90 substrates |

Streptomyces as Heterologous Expression Hosts

Advantages and Limitations

Streptomyces species offer several advantages as heterologous expression hosts. Their robust and scalable growth, well-established in industrial fermentation, provides a practical foundation for large-scale production [21]. As Gram-positive bacteria lacking an outer membrane, streptomycetes efficiently secrete proteins directly into the extracellular medium, simplifying downstream purification [21]. Additionally, they exhibit low toxicity and do not produce lipopolysaccharides, avoiding potent immunostimulatory endotoxins that complicate production in Gram-negative systems [21].

The cellular environment of Streptomyces is particularly suited for expressing complex bacterial BGCs. Their high GC content matches that of many actinobacterial BGCs, eliminating the need for codon optimization frequently required in low-GC hosts like E. coli [21]. Furthermore, Streptomyces provides appropriate redox conditions for correct disulfide bond formation and folding of complex enzymes such as polyketide synthases (PKSs) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) [21].

However, significant challenges remain. Streptomycetes often have complex growth patterns, forming dense mycelial clumps that complicate fermentation scale-up. Genetic manipulation can be more challenging compared to model organisms like E. coli, though tool development has accelerated recently [21]. Native regulatory networks and competing metabolic pathways can also interfere with heterologous production, necessitating extensive host engineering.

Current Host Strain Panel

Several Streptomyces strains have emerged as preferred hosts for heterologous expression. A comprehensive analysis of over 450 peer-reviewed studies published between 2004 and 2024 reveals distinct host preferences within the research community [20] [9].

Streptomyces coelicolor derivatives, particularly M1152 and M1154, are among the most characterized hosts. M1152 was engineered by deleting four native BGCs (actinorhodin, prodiginine, coelimycin, and calcium-dependent antibiotic) and introducing a point mutation in the rpoB gene, resulting in 20-40-fold yield improvements for certain natural products [3].

Streptomyces lividans TK24 is valued for its ability to accept methylated DNA and low protease activity. Recent engineering efforts created strain ΔYA11 with nine deleted BGCs and additional attB integration sites, demonstrating superior production for several metabolites compared to its progenitor [3].

Streptomyces albus J1074 provides a naturally reduced genome and has been minimized further through the Del14 strain, where 15 native secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways were deleted [3].

Streptomyces sp. A4420 represents a newly developed chassis specifically engineered for polyketide production. The CH strain derivative had nine native polyketide BGCs deleted and demonstrated capability to produce all four tested polyketides across various conditions, outperforming established hosts like S. coelicolor M1152, S. lividans TK24, and S. albus J1074 [3].

Figure 1: Strategic Framework for Streptomyces Host Selection

Engineering Optimized Chassis Strains

Genome Reduction and Metabolic Streamlining

A primary strategy in chassis development involves eliminating native BGCs to reduce metabolic burden and background interference. The engineered Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain exemplifies this approach, with deletion of 9 native polyketide BGCs resulting in improved heterologous production while maintaining robust growth and sporulation [3]. Similarly, S. albus Del14 had 15 native secondary metabolite pathways removed, creating a cleaner background for heterologous expression [3].

S. griseofuscus DSM 40191 has been engineered through the deletion of two native plasmids and two BGCs (pentamycin and an unknown NRPS cluster), resulting in strain DEL2 with approximately 500 kbp genome reduction (5.19% of the genome) [12]. This reduced strain exhibited faster growth and lost the ability to produce three main native metabolites (lankacidin, lankamycin, pentamycin and their derivatives), while maintaining capacity for heterologous production of compounds like actinorhodin [12].

Enhanced Integration and Expression Systems

Advanced genetic tools have been developed to facilitate efficient BGC integration and expression. The Micro-HEP (microbial heterologous expression platform) utilizes versatile E. coli strains for BGC modification and conjugation transfer, coupled with optimized Streptomyces chassis strains [5]. This system addresses limitations of conventional conjugative transfer systems, particularly instability of repeated sequences that hampered previous approaches [5].

Chromosomal amplification strategies represent another key engineering approach. Multiple recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites have been incorporated into chassis genomes to enable site-specific integration of multiple BGC copies. In S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023, modular RMCE cassettes (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, and phiBT1-attP) were constructed for integrating BGCs into predefined chromosomal loci [5]. This system demonstrated that increasing copy number of the xiamenmycin BGC from two to four copies correlated with increasing yield of the final product [5].

Figure 2: Streptomyces Chassis Development Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Host Evaluation

Comprehensive Phenotype Characterization: Detailed physiological profiling using platforms such as BioLog microarrays enables systematic assessment of substrate utilization capabilities. This approach, applied to S. griseofuscus DSM40191, tested 379 substrates including 190 carbon sources, 95 nitrogen sources, and 94 phosphate/sulphur sources, providing a metabolic fingerprint for host selection [12]. The activity index (0-9 scale) with a cutoff >3 defined growth capacity, revealing that S. griseofuscus utilized 171 substrates, comparable to S. coelicolor (172) and superior to S. venezuelae (117) [12].

Comparative Production Assessment: Rigorous evaluation of heterologous production capability should employ multiple benchmark BGCs with diverse chemical products. The assessment of Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain utilized four distinct polyketide BGCs encoding benzoisochromanequinone, glycosylated macrolide, glycosylated polyene macrolactam, and heterodimeric aromatic polyketide products [3]. This multi-cluster approach provided comprehensive insight into host performance across different metabolic pathways.

Matrix-Based Strain Scoring: A systematic evaluation framework involving 15 parameters enables objective comparison of potential hosts [3]. This multidimensional analysis assesses critical attributes including growth rate, sporulation efficiency, genetic manipulability, precursor availability, secretion capacity, and production yields, generating a quantitative profile to guide host selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Streptomyces Engineering

| Reagent/System | Type | Function | Application Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | Bioinformatics tool | BGC identification and analysis | Genome mining of native BGCs for deletion targeting | [3] [12] |

| pSC101-PRha-αβγA-PBAD-ccdA | Temperature-sensitive plasmid | rhamnose-inducible Redαβγ recombination | Markerless DNA manipulation in E. coli donor strains | [5] |

| E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) | Conjugative donor strain | BGC transfer from E. coli to Streptomyces | Intergeneric conjugation for large DNA fragment transfer | [5] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Genome editing tool | Targeted gene/BGC deletion | Curing native plasmids and deleting competing BGCs | [12] |

| RMCE cassettes (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, phiBT1-attP) | Site-specific integration system | BGC integration at defined chromosomal loci | Multi-copy BGC integration for enhanced production | [5] |

| BioLog Phenotype Microarrays | Metabolic profiling platform | High-throughput substrate utilization assessment | Comprehensive metabolic capability characterization | [12] |

| Wilfortrine | Wilfortrine, MF:C41H47NO20, MW:873.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Ebov-IN-9 | Ebov-IN-9, MF:C25H22O8, MW:450.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The field of Streptomyces host engineering is advancing toward specialized chassis tailored for specific product classes. The development of Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH as a polyketide-focused chassis represents this trend, demonstrating how phylogenetic distance from commonly used hosts can provide unique metabolic advantages [3]. Future efforts will likely produce additional specialized chassis optimized for specific BGC types, such as those encoding non-ribosomal peptides, hybrid molecules, or specific chemical classes.

Integration of systems biology approaches with synthetic biology design principles will further advance chassis development. The design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycle enables iterative refinement of host strains, incorporating multi-omics data to guide targeted modifications [21]. As the relationships between species phylogeny and secondary metabolite-biosynthetic gene clusters become clearer, taxonomic classification will provide increasingly valuable information for predicting host suitability for specific BGC types [19].

The expanding panel of well-characterized Streptomyces hosts, coupled with advanced genetic tools and systematic evaluation frameworks, promises to significantly increase the success rate of heterologous BGC expression. This progress is essential for unlocking the biosynthetic potential encoded in the countless silent or cryptic BGCs identified through genome mining, enabling discovery and production of novel bioactive compounds with applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry.

The Critical Challenge of Silent and Cryptic Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

Microbial natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have been indispensable in modern medicine, forming the foundation for a substantial proportion of antimicrobial, anticancer, and immunosuppressant drugs [23] [3]. Traditionally, the discovery of these compounds has relied on laboratory cultivation of microorganisms and analysis of their metabolic output. However, the advent of widespread microbial genome sequencing has revealed a startling discrepancy: the vast majority of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs)—physically grouped genes encoding the enzymatic pathways for natural product synthesis—remain silent or cryptic under standard laboratory conditions [23] [24]. These BGCs are bioinformatically detectable but do not yield detectable amounts of their encoded compounds, creating a significant bottleneck in natural product discovery [23]. This review examines the critical challenge these silent BGCs represent and details the sophisticated strategies, particularly those involving engineered Streptomyces hosts, being developed to access this hidden chemical wealth.

Genomic analyses consistently demonstrate that silent BGCs outnumber constitutively active ones by a factor of 5–10 in prolific producers like streptomycetes [24]. For example, in the entomopathogenic bacteria Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus, pangenome analysis of 45 strains revealed 1,000 BGCs belonging to 176 families, with non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) being the most abundant class [25]. This hidden biosynthetic potential underscores that our current arsenal of natural therapeutic agents is based on only a tiny fraction of microbial biosynthetic capacity [23]. Unlocking silent BGCs is therefore not merely a technical challenge but a fundamental imperative for drug discovery and for understanding microbial ecology and physiology [24].

Defining the Challenge: What Makes a Gene Cluster Silent?

Terminology and Underlying Causes

The terms "silent," "cryptic," and "orphan" are often used interchangeably to describe BGCs that do not produce detectable metabolites under standard laboratory conditions [23]. Several interdependent factors can contribute to this silence, creating a multi-faceted problem for researchers.

- Complex Regulation: The expression of many BGCs is controlled by intricate regulatory networks that may not be activated in artificial culture conditions. These can include pathway-specific regulators, global regulatory systems, and quorum-sensing mechanisms [23] [24].

- Missing Environmental Cues: In their natural habitats, bacteria exist within complex communities and are exposed to specific chemical and physical signals from competitors, predators, or symbiotic partners. The absence of these elicitors in axenic laboratory culture leaves many BGCs dormant [24] [26].

- Insufficient Precursor Supply: The biosynthesis of complex natural products requires specific metabolic precursors and cofactors. The necessary metabolic flux may not be present if the native host's primary metabolism is not appropriately aligned with the secondary metabolic pathway [23].

- Genetic Inaccessibility: For some BGCs, the native producer is uncultivable under laboratory conditions or exhibits poor growth and sporulation, making conventional fermentation and genetic manipulation impractical [23] [3].

The Heterologous Expression Solution

Heterologous expression—the transfer and expression of a BGC in a genetically tractable surrogate host—has emerged as a powerful and generalizable solution to these challenges [23] [27]. This approach bypasses the native host's complex regulation, circumvents culturing difficulties, and allows for the refactoring of BGCs with strong, constitutive promoters [24]. A successful heterologous host must possess several key attributes: genetic tractability, rapid growth, abundant biosynthetic precursor availability, compatibility with conjugation-based DNA transfer, and ideally, a low background of native secondary metabolites to simplify the detection of new compounds [3] [27].

EngineeredStreptomycesChassis Strains for Heterologous Expression

The genus Streptomyces is renowned for its prolific production of secondary metabolites and has become the primary chassis for heterologous expression of actinobacterial BGCs. Recent research has focused on systematically engineering optimized Streptomyces hosts that maximize the success rate of BGC expression.

Table 1: Engineered Streptomyces Chassis Strains for Heterologous Expression

| Chassis Strain | Parental Strain | Key Genetic Modifications | Demonstrated Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH [3] | Streptomyces sp. A4420 | Deletion of 9 native polyketide BGCs [3] | Outperformed established hosts (S. coelicolor M1152, S. lividans TK24, S. albus J1074); produced all four tested polyketides; rapid growth and high sporulation rate [3]. |

| S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 [27] | S. coelicolor A3(2) | Deletion of four endogenous BGCs (actinorhodin, prodiginine, coelimycin, CDAs); introduction of multiple RMCE sites (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, phiBT1-attP) [27]. | Enables markerless, multi-copy integration of BGCs via orthogonal recombination systems, increasing product yield with copy number [27]. |

| S. coelicolor M1152 [3] | S. coelicolor M1154 | Deletion of four BGCs (actinorhodin, prodiginine, coelimycin, CDA); introduction of point mutations (rpoB, rpsL) conferring antibiotic resistance [3]. | Well-characterized; yields of heterologously expressed compounds increased 20-40 fold compared to wild-type [3]. |

| S. lividans ΔYA11 [3] | S. lividans TK24 | Deletion of nine native BGCs; introduction of two additional attB integration sites [3]. | Superior production levels for tested metabolites compared to TK24 and M1152; robust growth [3]. |

| S. albus Del14 [3] | S. albus J1074 | Deletion of 15 native secondary metabolite BGCs [3]. | "Clean" metabolic background simplifies detection of heterologous products [3]. |

The development of Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH exemplifies a modern chassis engineering approach. This strain was selected from a natural isolate library for its rapid initial growth and high inherent metabolic capacity [3]. Subsequent genome sequencing and antiSMASH analysis identified nine native polyketide BGCs, which were deleted to create a metabolically simplified CH (chassis) strain [3]. In a head-to-head comparison with other common heterologous hosts, the A4420 CH strain was the only one capable of producing all four benchmark polyketides—a benzoisochromanequinone, a glycosylated macrolide, a glycosylated polyene macrolactam, and a heterodimeric aromatic polyketide—under every tested condition [3].

Advanced Toolkits for Heterologous Expression

Beyond the chassis strains themselves, integrated platforms that streamline the entire process from BGC cloning to expression are critical. The recently developed Micro-HEP (microbial heterologous expression platform) exemplifies this trend [27]. This system utilizes:

- Versatile E. coli Donor Strains: Engineered for high-efficiency Red recombinase-mediated modification of BGCs and stable conjugative transfer, even for large DNA fragments with repetitive sequences.

- Optimized Chassis Strain: S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023, engineered with multiple recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites.

- Modular RMCE Cassettes: Orthogonal integration systems (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, phiBT1-attP) that allow for markerless, multi-copy integration of BGCs without plasmid backbone integration, enabling increased product yield with higher copy number [27].

The platform was validated by expressing the xiamenmycin (xim) BGC, where increasing the copy number from two to four led to a corresponding increase in xiamenmycin production, and the griseorhodin (grh) BGC, which resulted in the discovery of a new compound, griseorhodin H [27].

Diagram 1: Heterologous Expression Workflow for Silent BGC Activation. This flowchart outlines the key steps in a modern heterologous expression pipeline, from BGC identification to compound characterization.

Complementary Activation Strategies in the Native Host

While heterologous expression is a powerful and general strategy, endogenous approaches that activate the BGC within its native producer remain vital for physiological relevance and for studying chemical ecology [23]. These methods have also seen significant advancements.

Genetic and Chemogenetic Approaches

Table 2: Endogenous Strategies for Activating Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

| Strategy | Methodology | Key Features | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Promoter Knock-in [24] | Replacement of native promoter with constitutive/inducible promoters using CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. | High efficiency; applicable in genetically intractable strains; allows refactoring of complex clusters. | Activation of a type II PKS in S. viridochromogenes led to a novel brown pigment with an unusual cyclohexanone modification [24]. |

| Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS) [23] | Fusion of a reporter gene (e.g., antibiotic resistance, fluorescence) to the target BGC promoter; screening of mutant libraries for activated clones. | Allows direct selection for activation; identifies regulatory genes via transposon insertion. | Identification of thailandenes, novel antimicrobial polyenes, in Burkholderia thailandensis via transposon mutagenesis [23]. |

| High-Throughput Elicitor Screening (HiTES) [24] | Insertion of a reporter gene (e.g., eGFP) into the silent BGC; screening of small-molecule libraries for inducers. | Identifies natural chemical signals; no prior knowledge of regulation needed. | Ivermectin and etoposide identified as elicitors of the sur NRPS cluster in S. albus, leading to 14 novel cryptic metabolites [24]. |

| Regulatory Gene Overexpression [26] | Constitutive expression of a pathway-specific activator gene (e.g., LAL regulators) located within the BGC. | Physiologically relevant activation; simple if the regulator is known. | Activation of a silent type I PKS in S. ambofaciens led to antitumor polyketides [26]. |

| AnCDA-IN-1 | AnCDA-IN-1, MF:C16H13ClN4O2, MW:328.75 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Sdh-IN-17 | Sdh-IN-17, MF:C24H19BrN2O5, MW:495.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram 2: Decision Workflow for Selecting a Silent BGC Activation Strategy. This diagram outlines the logical process for choosing the most appropriate method based on genetic tractability and available information.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: HiTES with a Fluorescent Reporter

The HiTES protocol provides a powerful method for identifying small molecules that induce silent BGCs [24]. The following is a generalized protocol:

Reporter Strain Construction:

- Fuse the promoter region (P~BGC~) of the silent BGC of interest to a strong reporter gene, such as a triple copy of enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFPx3).

- Integrate this P~BGC~-eGFPx3 construct into a neutral site on the chromosome of the native host using a site-specific integration system (e.g., phiC31, T7). Alternatively, integrate the eGFPx3 cassette directly downstream of the native P~BGC~.

- Validate the reporter strain by confirming the absence of fluorescence under non-inducing conditions.

High-Throughput Screening:

- Grow the reporter strain in a 96-well or 384-well format in a suitable liquid medium.

- Add a library of potential elicitor molecules (e.g., natural product libraries, FDA-approved drug libraries, cell lysates) to the cultures. Include negative controls (DMSO or solvent alone).

- Incubate the plates with shaking for a period that allows for gene expression and protein maturation (e.g., 24-72 hours for streptomycetes).

Hit Identification and Validation:

- Measure fluorescence intensity using a plate reader. Normalize fluorescence to cell density (OD~600~) to account for growth effects.

- Select hits that show a statistically significant increase in fluorescence relative to controls.

- Re-test the hit compounds in a dose-response experiment to confirm induction.

Metabolite Analysis:

- Cultivate the wild-type strain in the presence and absence of the confirmed elicitor.

- Extract the culture broth and mycelia with organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate, methanol).

- Analyze the extracts using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) and compare chromatograms to identify metabolites unique to or enhanced in the elicitor-treated culture.

- Isulate and purify the novel metabolites using preparative HPLC and determine their structures using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Silent BGC Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Software | Identifies and annotates BGCs in genome sequences. | antiSMASH: Standard for BGC prediction and analysis [3] [25]. PRISM: Predicts chemical structures from genomic data [23]. BiG-FAM: Classifies BGCs into Gene Cluster Families [25]. |

| Cloning Systems | Captures large DNA fragments containing entire BGCs. | TAR (Transformation-Associated Recombination): Yeast-based homologous recombination for direct cloning from gDNA [24] [27]. ExoCET: Combines exonuclease and RecET recombination for direct cloning [27]. |

| Recombineering Systems | Enables precise genetic modification of BGCs in E. coli. | λ-Red (Redα/Redβ/Redγ): Allows efficient gene knock-in, knockout, and promoter replacement using short homology arms [27]. |

| Conjugal Transfer System | Transfers large, unstable BGC constructs from E. coli to Streptomyces. | E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002: Common but limited donor. Micro-HEP E. coli strains: Improved stability for repeated sequences and transfer efficiency [27]. |

| Site-Specific Integration Systems | Stably integrates BGCs into the chromosome of the heterologous host. | PhiC31-attB/attP: Most common serine recombinase system. Tyrosine Recombinases (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox): Enable orthogonal, markerless RMCE for multi-copy integration [27]. |

| Reporter Genes | Provides a readout for BGC expression in HiTES and RGMS. | Fluorescent Proteins (eGFP): For quantitative screening. Antibiotic Resistance Genes (neo, Kan^R^): For direct selection of activated clones [23] [24]. |

| Analytical Chemistry Tools | Detects, quantifies, and characterizes novel cryptic metabolites. | HPLC-MS/MS: For metabolite separation and initial identification. Imaging MS (IMS): Spatially resolves metabolite production on plates [23]. NMR Spectroscopy: Essential for full structural elucidation [28]. |

| Apicularen A | Apicularen A, MF:C25H31NO6, MW:441.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DNA polymerase-IN-5 | DNA polymerase-IN-5, MF:C20H19F3N2O4, MW:408.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The challenge of silent and cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters represents both a significant bottleneck and an extraordinary opportunity in natural product discovery. The genomic era has unequivocally revealed the vastness of this untapped resource. Fortunately, the field has responded with an equally sophisticated and diverse arsenal of strategies to meet this challenge. As detailed in this review, the engineered Streptomyces heterologous expression platform stands as a cornerstone of these efforts, with continuously improving chassis strains like Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH and integrated systems like Micro-HEP demonstrating remarkable success in activating and producing complex metabolites from diverse BGCs [3] [27].

The future of this field lies in the intelligent integration of multiple approaches. Genome mining will become increasingly predictive, guiding the selection of high-priority BGCs. Heterologous expression platforms will continue to evolve towards greater efficiency and broader host range, potentially encompassing non-Streptomyces chassis for expressing BGCs from phylogenetically distant organisms. Meanwhile, endogenous strategies like HiTES and CRISPR-Cas9 editing will remain indispensable for uncovering the physiological roles and regulatory logic of these cryptic pathways. By leveraging this comprehensive toolkit, researchers are well-positioned to systematically illuminate the "dark matter" of microbial metabolism, accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents and deepening our understanding of microbial chemical communication.

Building a Better Host: Advanced Engineering Strategies and Platform Technologies

The efficient heterologous production of microbial natural products (NPs) is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and biotechnology. Within this field, Streptomyces species have emerged as the most widely used and versatile chassis for expressing complex biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from diverse microbial origins [20]. However, a significant bottleneck exists: the native metabolic background of a host strain can severely interfere with the production of foreign compounds. Host strain tailoring, specifically the deletion of competing native BGCs, is therefore a critical initial step in constructing a high-performance heterologous expression platform [21].

This process creates a "metabolically simplified" chassis with several key advantages. It eliminates the production of native secondary metabolites that can complicate the detection and purification of the target compound. Furthermore, it removes internal competition for essential biosynthetic precursors, such as acyl-CoAs for polyketides and amino acids for non-ribosomal peptides, thereby redirecting cellular resources toward the heterologous pathway [21]. It also provides a cleaner background for analytical techniques like HPLC and MS, facilitating the discovery of new compounds. Finally, engineered chassis often exhibit more consistent growth and sporulation patterns, enhancing the reproducibility of fermentation processes [3]. This guide details the core principles and methodologies for implementing this essential strategy, framing it within the broader context of developing engineered Streptomyces hosts for heterologous expression research.

Core Principles and Strategic Deletion Frameworks

The deletion of native BGCs is not a random process but follows a rational design strategy. The primary goal is to remove gene clusters that compete for the same cellular resources required by the target heterologous pathway, with a particular focus on polyketide synthase (PKS) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) clusters, which are major consumers of key precursors.

A leading example is the engineering of the Streptomyces sp. A4420 strain. In this case, researchers identified and deleted 9 native polyketide BGCs to create a specialized, polyketide-focused chassis strain known as the CH strain [3]. This extensive deletion aimed to maximize the availability of precursors like malonyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA for incoming heterologous PKS pathways. The resulting CH strain demonstrated consistent sporulation and growth, and in a comparative study, it was the only host capable of producing all four tested heterologous polyketides, outperforming other common hosts like S. coelicolor M1152 and S. albus J1074 [3].

Similar approaches have been successfully applied to other popular host strains, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Engineered Streptomyces Chassis Strains with Deleted Native BGCs

| Chassis Strain | Parental Strain | Number of BGCs Deleted | Primary Focus / Outcome | Key Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH [3] | Streptomyces sp. A4420 | 9 | Polyketide production; outperformed several common hosts. | Produced all four tested heterologous polyketides. |

| S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 [5] | S. coelicolor A3(2) | 4 | Serves as a versatile host in the Micro-HEP platform. | Enabled high-yield production of xiamenmycin and griseorhodin. |

| S. coelicolor M1152 [3] | S. coelicolor M145 | 4 (Act, Red, CDA, CPK) | "Cleaner" background with additional advantageous mutations. | Shows remarkable increases in natural product yields (20-40 fold). |

| S. lividans ΔYA11 [3] | S. lividans TK24 | 9 | Enhanced production of heterologous metabolites. | Superior production for three metabolites vs. progenitor TK24. |

| S. albus Del14 [3] | S. albus J1074 | 14 (15 pathways) | Minimized genome host for natural product production. | Streamlined detection of heterologously expressed products. |

The strategic thinking behind these deletions is encapsulated in the following workflow, which outlines the key decision points in developing a tailored host strain.