Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Discovery

Enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) represent a transformative advancement over traditional genome-scale metabolic models by integrating catalytic constraints and proteomic data.

Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

Enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) represent a transformative advancement over traditional genome-scale metabolic models by integrating catalytic constraints and proteomic data. This article provides a comprehensive exploration for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of ecModels, key methodologies including GECKO, AutoPACMEN, and ECMpy frameworks, and their diverse applications from metabolic engineering to drug discovery. We detail practical approaches for parameter optimization and kcat prediction using deep learning tools like DLKcat, present rigorous model validation techniques, and compare predictive capabilities across different platforms. Through case studies in cancer research and industrial biotechnology, we demonstrate how ecModels enable more accurate prediction of cellular phenotypes, identification of therapeutic vulnerabilities, and design of efficient microbial cell factories.

Understanding Enzyme Constraints: The Foundation of Next-Generation Metabolic Modeling

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) has revolutionized systems biology by providing a mathematical framework to study metabolic networks. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent the biochemical reactions occurring within an organism and enable the prediction of metabolic phenotypes using computational methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). However, traditional GEMs consider only stoichiometric constraints, leading to a linear increase in predicted growth and product yields as substrate uptake rates rise, which often diverges from experimental observations [1] [2].

The integration of enzymatic constraints into GEMs has emerged as a transformative advancement, addressing fundamental limitations of traditional models. Enzyme-constrained models (ecModels) incorporate kinetic parameters and proteomic limitations, enabling more accurate predictions of metabolic behaviors, including overflow metabolism and protein resource allocation [1] [3]. This evolution from GEMs to ecModels represents a significant milestone in constraint-based modeling, enhancing its applications in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and drug development.

This protocol article details the methodologies for constructing and analyzing ecModels, framed within the broader context of a thesis on enzyme-constrained metabolic models. We provide comprehensive application notes, experimental protocols, and visualization tools to empower researchers in implementing these advanced modeling approaches.

Background and Theoretical Framework

The Need for Enzyme Constraints

Traditional GEMs assume that metabolic fluxes are constrained only by reaction stoichiometry and uptake rates. While valuable for many applications, this approach fails to account for the physiological limitations imposed by enzyme kinetics and the cellular proteome. Consequently, GEMs cannot predict the seemingly wasteful strategy of overflow metabolism, where cells utilize fermentation instead of more efficient respiration under certain conditions [1] [3].

ecModels address these limitations by incorporating fundamental physicochemical constraints:

- Enzyme kinetics: Catalytic constants (kcat values) define the maximum turnover rate for each enzyme

- Proteome allocation: The total cellular protein content limits the sum of all enzyme concentrations

- Molecular crowding: The finite physical space within cells restricts the maximum concentration of enzymes [3]

The integration of these constraints has proven particularly valuable for predicting metabolic engineering targets to enhance the production of commodity chemicals, including riboflavin, menaquinone 7, and acetoin in Bacillus subtilis [1].

Key Methodological Approaches

Several computational frameworks have been developed for constructing ecModels, each with distinct advantages:

Table 1: Comparison of Major ecModel Construction Platforms

| Platform | Primary Language | Key Features | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO | MATLAB | Automated retrieval of kinetic parameters from BRENDA; direct integration of proteomics data | S. cerevisiae, E. coli, Homo sapiens [3] [4] |

| ECMpy | Python | Machine learning-predicted enzyme kinetics; accounts for protein subunit composition | B. subtilis (ecBSU1), E. coli [1] [2] |

| AutoPACMEN | Not specified | Simplified model structure with minimal pseudo-reactions and metabolites | Early B. subtilis models [1] |

Protocols for ecModel Reconstruction and Analysis

Protocol 1: ecModel Construction with GECKO Toolbox 3.0

The GECKO (Enhanced GEMs with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox represents one of the most comprehensive platforms for ecModel development [4]. The protocol consists of five main stages:

Stage 1: Expansion from a Starting Metabolic Model to an ecModel Structure

- Begin with a high-quality GEM in SBML format

- Add enzyme pseudometabolites and enzyme usage reactions for each metabolic reaction

- Incorporate constraints representing the total protein pool available for metabolism

Stage 2: Integration of Enzyme Turnover Numbers

- Retrieve kcat values from the BRENDA database using automated hierarchical matching

- Implement deep learning-predicted enzyme kinetics for reactions lacking experimental data

- Apply wildcard search for enzymes with missing specific EC numbers (56.03% of kcat values in ecYeast7 were obtained this way) [3]

Stage 3: Model Tuning

- Calibrate the model to reproduce known physiological growth rates

- Identify and correct kinetically limiting reactions that may create bottlenecks

- Adjust enzyme mass fraction constraints based on proteomic data

Stage 4: Integration of Proteomics Data

- Incorporate absolute protein abundance measurements from resources like PAXdb

- Calculate enzyme mass fractions using the formula: $f = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{p_num} Ai MWi}{\sum{j=1}^{g_num} Aj MWj}$ where $Ai$ and $Aj$ represent protein abundances, and $MW$ represents molecular weights [1]

- Apply individual enzyme constraints for measured proteins while constraining unmeasured enzymes by the remaining protein pool

Stage 5: Simulation and Analysis

- Perform phenotype predictions using constraint-based methods

- Analyze flux distributions under various environmental conditions

- Identify potential metabolic engineering targets

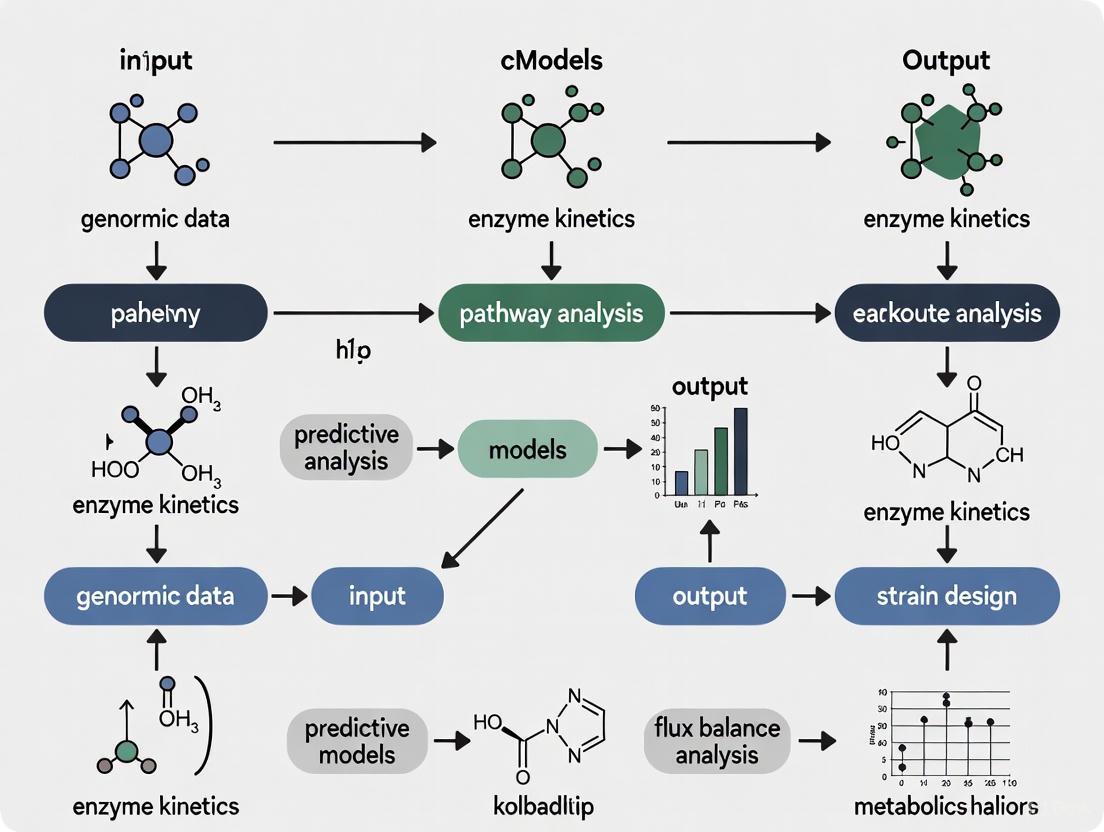

Diagram 1: GECKO 3.0 Workflow

Protocol 2: ecModel Development with ECMpy 2.0

ECMpy provides a Python-based alternative for ecModel construction, with particular emphasis on automated parameter retrieval and machine learning approaches to enhance parameter coverage [2].

Step 1: Model Preprocessing

- Systematically correct EC numbers and Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) relationships

- Convert metabolite and reaction identifiers to BiGG IDs for consistency

- Divide reversible reactions into pairs of irreversible reactions

- Split reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into separate reactions

Step 2: Enzyme Molecular Weight Calculation

- Download molecular weights from UniProt database according to gene IDs

- Parse 'Interaction information' in UniProt to determine subunit composition

- Calculate molecular weight for enzyme complexes using: $MW = \sum{j=1}^{m} Nj \times MWj$ where $m$ represents different subunits, and $Nj$ represents the number of jth subunits [1]

Step 3: Kinetic Parameter Acquisition

- Obtain kcat values from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases using EC numbers

- Apply machine learning prediction to fill gaps in kinetic parameters

- Use hierarchical matching criteria when organism-specific parameters are unavailable

Step 4: Incorporation of Enzyme Constraints

- Introduce enzymatic constraint: $\sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{vi \times MWi}{\sigmai \times kcati} \leq ptot \times f$ where $ptot$ is total protein content, $f$ is enzyme mass fraction, and $\sigmai$ is enzyme saturation coefficient [1]

- Implement total enzyme amount constraint directly into the GEM

Step 5: Parameter Calibration

- Calculate enzyme cost of each reaction with biomass maximization as the objective

- Rank reactions by enzyme cost and select reactions with largest costs as candidates for correction

- Modify reaction kcat to maximal corresponding kcat in databases iteratively until growth rate reaches experimentally reported values [1]

Diagram 2: ECMpy 2.0 Workflow

Protocol 3: Analysis of Enzyme-Constrained Models

Phenotype Phase Plane (PhPP) Analysis

- Vary substrate uptake and oxygen supply rates within physiological ranges (e.g., 0-15 mmol/gDW/h glucose, 0-50 mmol/gDW/h oxygen)

- Perform parsimonious FBA (pFBA) calculations with biomass maximization as objective

- Identify optimal growth regions and phase transitions between metabolic states [1]

Growth Rate Prediction on Different Carbon Sources

- Simulate growth on multiple carbon sources (e.g., 8 substrates for B. subtilis)

- Compare prediction results with literature values

- Calculate estimation error for growth rate and normalized flux error [1]

Overflow Metabolism Simulation

- Analyze the transition between respiratory and fermentative metabolism

- Identify critical dilution rates where overflow metabolism occurs

- Examine the trade-off between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency

Applications and Case Studies

Case Study 1: ecBSU1 forBacillus subtilis

The construction of ecBSU1, the first genome-scale ecModel for B. subtilis, demonstrates the practical implementation of these protocols. Using ECMpy, researchers systematically updated the iBsu1147 model through GPR correction and biomass reaction standardization [1].

Table 2: Key Improvements in ecBSU1 Compared to Traditional GEM

| Feature | iBsu1147 (GEM) | ecBSU1 (ecModel) | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constraints | Stoichiometry only | Enzyme kinetics + proteome allocation | More realistic flux predictions |

| Overflow Metabolism | Unable to predict | Accurate prediction of fermentative/respiratory transitions | Explains experimental observations |

| Growth Prediction | Moderate accuracy (varies with substrate) | High accuracy across 8 carbon sources | R² = 0.94 with experimental data [1] |

| Engineering Targets | Limited identification | Enhanced identification of gene targets | Improved guidance for strain design |

The model successfully identified target genes for enhancing the yield of commodity chemicals, most of which were consistent with experimental data, while some may represent novel targets for metabolic engineering [1].

Case Study 2: ecModels for Microbial Communities

Recent advances have extended ecModel applications to microbial communities. Comparative analysis of community models reconstructed from automated tools (CarveMe, gapseq, KBase) reveals significant structural and functional differences [5].

Consensus approaches that combine multiple reconstruction tools yield models with:

- Larger number of reactions and metabolites (enhanced coverage)

- Reduced dead-end metabolites (improved network connectivity)

- Stronger genomic evidence support for reactions [5]

These consensus models facilitate more accurate prediction of metabolite exchanges and interactions in complex microbial systems.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ecModel Development

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | Kinetic database | Primary source of enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) | https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/ [3] |

| SABIO-RK | Kinetic database | Supplementary source of enzyme kinetic parameters | http://sabio.h-its.org/ [1] |

| UniProt | Protein database | Molecular weights and subunit composition data | https://www.uniprot.org/ [1] |

| PAXdb | Proteomics database | Protein abundance data for constraint calculation | https://pax-db.org/ [1] |

| ModelSEED | Biochemical database | Reaction database for gap-filling and validation | https://modelseed.org/ [5] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software platform | Constraint-based modeling and simulation | https://opencobra.github.io/ [3] |

The evolution from GEMs to ecModels represents a paradigm shift in constraint-based modeling, addressing fundamental limitations through the integration of enzymatic constraints. The protocols outlined herein provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for constructing, validating, and applying ecModels to diverse biological questions.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on:

- Enhanced machine learning approaches for kinetic parameter prediction

- Integration of multi-omics data for context-specific constraints

- Expansion to eukaryotic systems and complex microbial communities

- Development of standardized validation frameworks

As ecModels continue to mature, they will play an increasingly vital role in metabolic engineering, drug development, and fundamental biological research, enabling more accurate predictions of cellular behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions.

Enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) represent a significant advancement in systems biology by integrating catalytic and proteomic constraints into traditional genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). While classical GEMs have been cornerstone tools for predicting cellular metabolism, they operate on stoichiometric and steady-state principles, lacking crucial information on enzyme kinetics, abundance, and the metabolic costs of protein synthesis [6]. This limitation restricts their ability to predict quantitative metabolic responses across diverse phenotypes, particularly under dynamic conditions or when subtle gene modifications are involved [6]. ecModels address this gap by explicitly incorporating enzyme turnover numbers (kcat), molecular weights, and enzyme mass fractions, enabling more accurate predictions of physiological states, metabolic fluxes, and growth rates by accounting for the inherent proteomic limitations faced by the cell [1]. The integration of these constraints has proven valuable across multiple domains, from fundamental physiological discovery to applied metabolic engineering in biotechnology and drug development [7] [1].

The theoretical foundation of ecModels rests on the principle that cellular metabolism is subject to resource allocation constraints, where the total pool of available enzyme protein is limited. These models mathematically represent the trade-off between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency, allowing researchers to simulate overflow metabolism and identify rate-limiting enzymes in biosynthetic pathways more effectively than traditional methods [1]. By directly coupling enzyme levels, metabolite concentrations, and metabolic fluxes within a single modeling framework, ecModels provide a more physiologically realistic representation of cellular processes, capturing dynamic regulatory effects and complex interactions that steady-state models cannot [6]. Recent methodological advancements, increased availability of enzyme kinetic parameters, and enhanced computational resources have accelerated the development and application of ecModels across diverse organisms, paving the way for their use in high-throughput studies and large-scale metabolic engineering projects [6].

Key Methodologies and Modeling Frameworks

Comparative Analysis of ecModel Construction Approaches

The construction of enzyme-constrained models has been streamlined through several automated and semi-automated computational workflows, each with distinct advantages and implementation considerations. The table below summarizes the principal methodologies currently employed in the field.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ecModel Construction Methodologies

| Method | Core Approach | Key Features | Typical Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO [1] | Adds enzyme pseudo-metabolites and usage constraints | Introduces enzyme saturation coefficients; Proteomic data integration | Growth prediction; Metabolic engineering | Increased model complexity; Manual calibration in initial versions |

| AutoPACMEN [1] | Simplified constraint addition | Single pseudo-reaction and metabolite; Database-driven kcat assignment | Genome-scale ecModel construction | Less complex than GECKO; Direct parameter expansion |

| ECMpy [1] | Direct total enzyme amount constraint | Automated kcat calibration; Cost-based parameter correction | High-throughput ecModel development; Target identification | Python-based; Automated wrong parameter identification |

| CORAL [8] | Incorporates underground metabolism | Integrates promiscuous enzyme activities; Increases flux flexibility | Robustness analysis; Metabolic defect simulation | Requires knowledge of enzyme promiscuity |

| ET-OptME [7] | Layered enzyme-thermo constraints | Combines enzyme efficiency with thermodynamic feasibility | Metabolic engineering design; DBTL cycle acceleration | Mitigates thermodynamic bottlenecks |

Workflow for ecModel Construction and Implementation

The development and application of ecModels follow a systematic protocol that integrates diverse biological data into a cohesive computational framework. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for constructing and implementing ecModels, from initial data acquisition to final model application.

Protocol for Building an Enzyme-Constrained Model Using ECMpy

Protocol 1: Genome-Scale ecModel Construction with ECMpy Workflow

This protocol describes the systematic process for constructing an enzyme-constrained metabolic model using the ECMpy workflow, as demonstrated for Bacillus subtilis (ecBSU1) [1]. The procedure integrates enzymatic constraints into a base GEM through sequential data integration and constraint layering.

Initial Requirements:

- A well-annotated genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) in standard format (SBML)

- Python environment with ECMpy installed

- Access to biological databases (UniProt, BRENDA, SABIO-RK, PAXdb)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Model Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Systematically correct Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) relationships and EC number annotations using tools like GPRuler and protein homology analysis [1].

- Convert metabolite and reaction identifiers to a consistent namespace (e.g., BiGG IDs) to ensure database compatibility.

- Validate mass and charge balance for all reactions, and standardize the biomass reaction composition based on experimental data.

Data Acquisition and Curation

- Molecular Weight Data: Retrieve molecular weights (MW) for each enzyme from UniProt using gene identifiers. For enzyme complexes, calculate total MW as the sum of all subunits: ( MW = \sum{j=1}^{m} Nj \times MWj ), where ( Nj ) is the copy number of the jth subunit [1].

- Kinetic Parameters: Obtain kcat values from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases using EC numbers as primary search terms. Resolve conflicting values through geometric mean calculation or manual literature verification [9] [1].

- Proteomic Data: Download protein abundance data from PAXdb or organism-specific databases. Calculate the enzyme mass fraction using the formula: ( f = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{p_num} Ai MWi}{\sum{j=1}^{g_num} Aj MWj} ), where ( A ) represents protein abundance, and ( p_num ) and ( g_num ) represent proteins in the model and entire proteome, respectively [1].

Enzyme Constraint Integration

- Split reversible reactions into irreversible forward and backward reactions.

- Separate reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into distinct reactions, ensuring each reaction maps to a single enzyme.

- Introduce the enzymatic capacity constraint: ( \sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{vi \times MWi}{\sigmai \times kcati} \leq p{tot} \times f ), where:

- ( vi ) = flux through reaction i

- ( \sigmai ) = enzyme saturation coefficient

- ( p_{tot} ) = total protein fraction [1]

Model Calibration and Validation

- Identify reactions with disproportionately high enzyme usage costs during biomass maximization.

- Iteratively replace problematic kcat values with the highest available database values until the growth rate reaches experimentally reported levels.

- Validate the calibrated model by predicting growth rates on different carbon sources and comparing with literature values. Calculate normalized flux errors to quantify predictive accuracy [1].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If model fails to produce realistic growth rates: Check kcat values for transport and ATP maintenance reactions, as these often require calibration.

- If numerical instability occurs: Verify reaction directionality and thermodynamic consistency.

- If enzyme costs seem unrealistic: Ensure correct molecular weight calculations for enzyme complexes.

Advanced Applications and Experimental Protocols

Simulating Metabolic Robustness with Underground Metabolism

Protocol 2: Analyzing Metabolic Flexibility Using the CORAL Toolbox

This protocol utilizes the CORAL toolbox to integrate underground metabolism (enzyme promiscuity) into constraint-based models, enabling analysis of metabolic robustness and flexibility in response to genetic perturbations [8].

Theoretical Background: Underground metabolism refers to the native promiscuous activities of enzymes that are not their primary catalytic functions. Integrating these activities into metabolic models significantly increases predicted metabolic flux variability and improves the accuracy of simulating growth under metabolic defects [8].

Procedure:

Model Expansion with Promiscuous Activities

- Identify potential promiscuous enzyme activities through literature mining, enzyme homology analysis, or experimental data.

- Add secondary reactions for promiscuous enzymes to the base metabolic model using the CORAL toolbox.

- Define stoichiometry and directionality for each promiscuous reaction based on biochemical evidence.

Flux Variability Analysis

- Perform flux variability analysis (FVA) on both the original and CORAL-expanded models.

- Compare the range of possible fluxes for each reaction between the two models.

- Calculate the percentage increase in flux solution space: ( \frac{FV{expanded} - FV{original}}{FV_{original}} \times 100\% )

Simulating Metabolic Defects

- Simulate gene knockout strains by constraining the flux through the primary reaction of a promiscuous enzyme to zero while allowing its promiscuous activities to remain active.

- Quantify the redistribution of flux through alternative pathways and promiscuous activities.

- Compare growth rate predictions between the original and expanded models for single and double gene knockout scenarios.

Data Interpretation

- Promiscuous enzymes typically show less impact on growth when knocked out compared to non-promiscuous enzymes, demonstrating their role in metabolic robustness [8].

- Analyze flux distributions to identify which promiscuous activities contribute to growth maintenance under metabolic defects.

Application Example: When applying CORAL to an E. coli enzyme-constrained model, simulations revealed that underground metabolism increased flux flexibility by 15-30% across different conditions. Knockout simulations showed that promiscuous enzymes could compensate for metabolic defects, with only minimal enzyme redistribution to side activities required to maintain cellular function [8].

Integrating Thermodynamic and Enzyme Constraints for Metabolic Engineering

Protocol 3: Enzyme-Thermo Optimization with ET-OptME Framework

This protocol describes the implementation of ET-OptME, a framework that systematically incorporates both enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic feasibility constraints into GEMs for improved metabolic engineering design [7].

Principle: ET-OptME combines kcat-derived enzyme usage constraints with thermodynamic feasibility analysis to identify and mitigate kinetic and thermodynamic bottlenecks in metabolic pathways, resulting in more physiologically realistic intervention strategies [7].

Experimental Workflow:

Base Model Preparation

- Start with a genome-scale metabolic model with accurate GPR rules and elemental balancing.

- Ensure all reactions are elementally and charge-balanced to enable thermodynamic calculations.

Thermodynamic Constraint Layering

- Estimate standard Gibbs free energy (ΔG'°) for each reaction using group contribution or component contribution methods.

- Calculate the Gibbs free energy (ΔG') for reactions under physiological conditions: ΔG' = ΔG'° + RTln(Q), where Q is the mass-action ratio.

- Constrain reaction directionality based on thermodynamic feasibility: reactions can only proceed in the direction of negative ΔG' [7].

Enzyme Constraint Integration

- Integrate kcat values as described in Protocol 1, ensuring consistency with thermodynamic constraints.

- Add total enzyme capacity constraint based on measured or estimated cellular protein content.

Optimal Strain Design Identification

- Use the constrained model to identify gene knockout, upregulation, and downregulation targets for enhanced product synthesis.

- Compare predictions with those from stoichiometric methods (e.g., OptForce) and enzyme-constrained methods without thermodynamic constraints.

- Calculate prediction accuracy and precision metrics: ( Precision = \frac{TP}{TP+FP} ), ( Accuracy = \frac{TP+TN}{TP+TN+FP+FN} ), where TP, TN, FP, FN represent true/false positives/negatives compared to experimental data [7].

Validation Metrics: In evaluations using Corynebacterium glutamicum models for five product targets, ET-OptME demonstrated at least 292%, 161%, and 70% increase in minimal precision and at least 106%, 97%, and 47% increase in accuracy compared to stoichiometric methods, thermodynamic-constrained methods, and enzyme-constrained algorithms respectively [7].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of enzyme-constrained modeling requires specialized computational tools and data resources. The following table comprehensively catalogs the essential reagents, databases, and software platforms referenced in the protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for ecModel Development

| Category | Resource Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Parameter Databases | BRENDA [9] [1] | Comprehensive enzyme kinetic data | Manually curated data; Extensive coverage | https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/ |

| SABIO-RK [9] [1] | Enzyme kinetic parameters | High-quality manual curation | http://sabio.h-its.org/ | |

| SKiD [9] | Structure-oriented kinetics dataset | Links 3D enzyme structures with kinetics | https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-025-05829-5 | |

| Protein and Genomic Databases | UniProt [1] | Protein sequence and functional information | Molecular weights; Subunit composition | https://www.uniprot.org/ |

| PAXdb [1] | Protein abundance data | Whole-organism proteomic data integration | https://pax-db.org/ | |

| Software and Modeling Platforms | ECMpy [1] | ecModel construction workflow | Automated kcat calibration; Python-based | https://github.com/NaGeZ/ECMpy |

| CORAL [8] | Underground metabolism integration | Analyzes enzyme promiscuity effects | Reference implementation from publication | |

| ET-OptME [7] | Enzyme-thermo optimization | Combines kinetic and thermodynamic constraints | Reference implementation from publication | |

| RAVEN Toolbox [10] | De novo model reconstruction | KEGG/MetaCyc integration; Gap-filling | https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/RAVEN | |

| Modeling Frameworks | SKiMpy [6] | Kinetic modeling framework | Efficient parameter sampling; Parallelizable | https://github.com/skimpys/skimpy |

| MASSpy [6] | Kinetic modeling with mass action | COBRApy integration; Computationally efficient | https://github.com/SysBioChalmers/MASSpy |

Future Directions and Implementation Considerations

The integration of enzyme kinetics and protein allocation constraints represents a paradigm shift in metabolic modeling, moving from purely stoichiometric representations toward more physiologically realistic models. As the field advances, several emerging trends are poised to further enhance the capabilities and applications of ecModels. The incorporation of machine learning approaches with mechanistic models is accelerating parameter estimation and model construction, reducing development time from months to days while maintaining biochemical realism [6]. Additionally, the growing availability of structure-oriented kinetic datasets like SKiD, which maps kcat and Km values to three-dimensional enzyme structures, promises to enhance our understanding of the structural determinants of catalytic efficiency and enable more accurate prediction of enzyme kinetics from structural features [9].

For research teams implementing these methodologies, successful adoption requires careful consideration of several practical factors. Organizations should establish standardized workflows for continuous data integration from the expanding ecosystem of kinetic databases, ensuring model parameters remain current with the latest experimental findings. Computational infrastructure must be scaled appropriately, as enzyme-constrained models typically require greater processing power and memory than traditional GEMs, particularly for large-scale flux variability analyses or parameter sampling studies. Finally, interdisciplinary collaboration between biochemical modelers, enzymologists, and experimentalists remains essential for validating model predictions and refining parameter estimates, creating an iterative cycle of model improvement and biological discovery.

As these technical and collaborative frameworks mature, enzyme-constrained models are positioned to become indispensable tools in both basic research and applied biotechnology, enabling more accurate prediction of metabolic behavior and more efficient design of engineered biological systems for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Classical Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) employing stoichiometric genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) has become an established tool for predicting cellular phenotypes across diverse organisms. However, these traditional models face inherent limitations as they do not explicitly account for critical biological constraints, including enzyme kinetics, enzyme availability, and proteome allocation. This often results in overly optimistic predictions of metabolic capabilities and growth rates, failing to capture well-known physiological phenomena such as overflow metabolism [11] [12]. Enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) have emerged as a powerful extension that addresses these limitations by incorporating enzymatic constraints based on kinetic parameters and proteomic information, leading to more accurate and biologically relevant predictions [13] [14] [15].

The integration of enzyme constraints fundamentally changes the solution space of metabolic models. Where traditional FBA with a single constraint typically selects the pathway with the highest yield (biomass per substrate), ecGEMs operate under multiple constraints that better reflect cellular reality [11]. This advancement allows researchers to exclude thermodynamically unfavorable and enzymatically costly pathways that would otherwise be selected in standard FBA simulations, resulting in more realistic phenotype predictions [13].

Key Advantages of Enzyme-Constrained Models

Enhanced Prediction Accuracy for Metabolic Phenotypes

Enzyme-constrained models demonstrate superior performance in predicting critical physiological parameters compared to traditional GEMs. By incorporating enzyme kinetics and abundance data, these models can more accurately simulate cellular growth rates, substrate uptake rates, and metabolic flux distributions under various genetic and environmental conditions [14] [16] [17].

Table 1: Quantitative Improvements in Prediction Accuracy with ecGEMs

| Organism | Model Comparison | Key Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ecGEM vs. traditional FBA | Accurately predicted increased glucose uptake (29 vs. 23 mmol/gCDW/h) and product formation in engineered strain | [16] |

| Aspergillus niger | ecGEM (eciJB1325) vs. base model | Significantly reduced flux variability in >40% of metabolic reactions | [14] [17] |

| Escherichia coli | EcoETM (with enzymatic/thermodynamic constraints) vs. iML1515 | Excluded thermodynamically unfavorable and enzymatically costly pathways | [13] |

| Myceliophthora thermophila | ecMTM vs. iYW1475 | Improved prediction of substrate hierarchy utilization from plant biomass | [18] |

A notable example comes from metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for anaerobic co-production of 2,3-butanediol and glycerol. The enzyme-constrained model accurately predicted the necessary increase in glucose consumption rate (29 mmol/gCDW/h) and corresponding enzyme reallocation from ribosomes to glycolysis that was subsequently confirmed experimentally [16]. This demonstrates how ecGEMs can reliably guide metabolic engineering strategies and predict consequent physiological adaptations.

Overcoming Fundamental FBA Limitations

Traditional FBA suffers from several significant limitations that ecGEMs effectively address:

Explanation of Overflow Metabolism: Standard FBA often fails to explain why microorganisms utilize seemingly inefficient metabolic strategies such as overflow metabolism (e.g., ethanol production in yeast under aerobic conditions). Enzyme-constrained models successfully predict these metabolic behaviors by accounting for the limited proteomic capacity and different enzyme costs of alternative pathways [11] [15]. The Crabtree effect in yeast, characterized by a switch to fermentative metabolism at high glucose uptake rates, is accurately captured by ecGEMs without needing to artificially constrain substrate uptake rates [15] [17].

Reduction of Solution Space: The incorporation of enzyme constraints significantly reduces the feasible solution space of metabolic models. In the case of Aspergillus niger, enzyme constraints reduced flux variability in over 40% of metabolic reactions, leading to more precise and biologically relevant predictions [14]. This reduction in flexibility more accurately reflects the limited metabolic options available to cells under physiological constraints.

Exclusion of Infeasible Pathways: ecGEMs naturally exclude metabolically expensive or thermodynamically unfavorable pathways that might be selected in traditional FBA. For E. coli, the synthesis pathway for carbamoyl-phosphate was identified as both thermodynamically unfavorable and enzymatically costly, and was consequently excluded in the enzyme-constrained model, leading to more realistic production pathways for derived metabolites like L-arginine and orotate [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Constructing Enzyme-Constrained Models with GECKO

The GECKO (Genome-scale model enhancement with Enzymatic Constraints accounting for Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox provides a standardized framework for constructing enzyme-constrained models [14] [15] [17]. The following protocol outlines the key steps:

Step 1: Model Preparation

- Obtain a high-quality stoichiometric GEM in standard format (SBML)

- Convert all reversible reactions to irreversible representations

- Verify gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations for completeness and accuracy

Step 2: Kinetic Parameter Collection

- Retrieve enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) from databases (BRENDA, SABIO-RK)

- Implement hierarchical matching: first organism-specific, then enzyme-specific, and finally reaction-specific kcat values

- For less-studied organisms, utilize machine learning-based kcat prediction tools (TurNuP, DLKcat) [18]

- Apply manual curation for key metabolic enzymes to ensure biological relevance

Step 3: Proteomics Data Integration

- Obtain absolute protein abundance data from proteomics studies or databases (PAXdb)

- For proteins without experimental data, use homolog-based abundance estimation

- Set upper bounds for enzyme usage reactions based on abundance measurements

Step 4: Model Extension

- Introduce enzymes as pseudo-metabolites in reactions with stoichiometry of 1/kcat

- Add enzyme usage reactions to represent enzyme allocation

- Incorporate pseudo-metabolites to distinguish isozyme activities

- Implement total enzyme pool constraint based on cellular protein capacity

Step 5: Model Validation and Calibration

- Validate model predictions against experimental growth rates and flux measurements

- Calibrate total enzyme pool size to match physiological protein content

- Adjust kcat values for key reactions if necessary to improve prediction accuracy

Figure 1: Workflow for constructing enzyme-constrained metabolic models using the GECKO framework.

Protocol: Validating ecGEM Predictions Experimentally

Experimental validation is crucial for verifying ecGEM predictions. The following protocol outlines key validation approaches:

Growth Rate and Substrate Consumption Measurements:

- Cultivate organisms under defined conditions (carbon sources, nutrient limitations)

- Measure growth rates (optical density or dry cell weight)

- Quantify substrate consumption rates and metabolic byproduct secretion

- Compare experimental values with model predictions across multiple conditions

Proteomic Analysis for Enzyme Allocation:

- Perform absolute quantitative proteomics to determine enzyme abundances

- Compare predicted versus measured enzyme allocation patterns

- Verify proteome reallocation in response to genetic or environmental perturbations

- For the engineered S. cerevisiae strain, proteomics confirmed the predicted reallocation from ribosomes (decrease from 25.5% to 18.5%) to glycolysis (increase from 28.7% to 43.5%) [16]

Metabolic Flux Analysis:

- Employ 13C-labeling experiments to determine intracellular flux distributions

- Compare measured fluxes with ecGEM predictions

- Validate exclusion of thermodynamically infeasible pathways

Gene Knockout Studies:

- Construct knockout strains for key metabolic enzymes

- Measure growth phenotypes and metabolic capabilities

- Verify ecGEM predictions of essential genes and metabolic adaptations

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ecGEM Development

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Database | Function and Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Toolboxes | GECKO Toolbox | MATLAB-based toolbox for automated ecGEM construction | [14] [15] |

| ECMpy | Python-based framework for ecGEM construction | [18] | |

| AutoPACMEN | Automated parameter collection and model enhancement | [19] | |

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA | Comprehensive enzyme kinetics database | [15] [19] |

| SABIO-RK | Database for biochemical reaction kinetics | [19] | |

| Proteomics Data | PAXdb | Protein abundance database across organisms | [14] [17] |

| Machine Learning Tools | TurNuP | Predicts kcat values using protein sequences | [18] |

| DLKcat | Deep learning-based kcat prediction | [18] | |

| Modeling Frameworks | COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB package for constraint-based modeling | [14] [17] |

| COBRApy | Python implementation of COBRA tools | [15] |

Implementation Considerations and Future Directions

The successful implementation of enzyme-constrained models requires careful consideration of several factors. The quality and coverage of kinetic parameters significantly impact model performance, with organism-specific kcat values preferred over generic estimates [15] [18]. For less-studied organisms, machine learning approaches for kcat prediction have shown promising results, though manual curation of central metabolic enzymes remains advisable [18].

Computational frameworks for ecGEM construction continue to evolve, with GECKO 2.0 offering improved parameterization procedures and expanded organism coverage [15]. The integration of enzyme constraints with other cellular limitations, such as thermodynamic constraints [13] and membrane space limitations [12], represents a promising direction for further improving prediction accuracy.

Future applications of ecGEMs span basic science, metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology. In drug development, these models can enhance our understanding of metabolic adaptations in disease states and support the identification of novel therapeutic targets [12] [20]. For industrial biotechnology, ecGEMs provide powerful tools for predicting optimal enzyme allocation patterns and guiding strain engineering strategies for improved product yields [16] [18].

Figure 2: Logical framework showing how enzyme constraints enhance traditional metabolic models and enable diverse applications.

Enzyme limitations are a fundamental governing principle in cellular metabolism, determining metabolic phenotypes, flux distributions, and cellular fitness across biological kingdoms. While stoichiometric genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have enabled remarkable advances in predicting cellular behavior, they often yield overly optimistic predictions by not accounting for the substantial protein cost of enzymatic catalysis [12]. The incorporation of enzyme constraints into metabolic models represents a paradigm shift in systems biology, moving from what is stoichiometrically possible to what is physiologically feasible given the finite proteomic resources of the cell [21] [22].

The biological rationale for enzyme constraints stems from three fundamental physical and evolutionary realities: (1) cells operate in a molecularly crowded environment with limited capacity for enzyme deployment [23], (2) enzymatic catalysis requires substantial protein investment with significant biosynthetic costs [22], and (3) evolution has shaped metabolic networks to balance efficiency, yield, and rate under these inherent constraints [24] [23]. This application note explores the biological foundations of enzyme limitations and provides practical methodologies for incorporating these constraints into predictive metabolic models.

Table 1: Fundamental Energy Demands and Enzyme Limitations in Cellular Metabolism

| Energy Demand Scale | Quantitative Range | Governing Enzyme Constraint | Physiological State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance Energy | ~0.3 mol ATP/L/h (mammalian cells) | Molecular motors fluidizing cytoplasm [23] | Basal metabolic state |

| Metabolic Switch Threshold | ~2 mol ATP/L/h (10x maintenance) | Molecular crowding limits oxidative phosphorylation enzymes [23] | Transition to aerobic fermentation |

| Maximum Metabolic Rate | ~8 mol ATP/L/h (mammalian cells) | Absolute enzyme packing density limitation [23] | Maximum growth conditions |

Fundamental Principles of Enzyme-Driven Metabolism

The Physical Basis of Enzyme Limitations

Cellular metabolism operates within the context of an intracellular milieu crowded with macromolecules and organelles [23]. Molecular crowding imposes a fundamental limit on the maximum density of metabolic enzymes, thereby constraining maximum metabolic rate [23]. This physical limitation creates a trade-off between pathway efficiency and enzyme molecular crowding cost—at low metabolic rates, cells can utilize high-yield pathways like oxidative phosphorylation, but at high metabolic rates, they must employ pathways with higher horsepower per enzyme volume, such as fermentation [23].

The entropic pressure of molecular crowding can be quantified as:

[ PS \approx \frac{kB T}{V_c} \ln \frac{\Phi}{\Phi - \phi} ]

where (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, (Vc) is crowder volume, (\Phi) is maximum packing density, and (\phi) is excluded volume fraction [23]. Cells counteract this entropic pressure through ATP-driven molecular motors that fluidize the cytoplasm, representing a significant component of the maintenance energy demand [23].

Evolutionary Retention of Non-Enzymatic Reactions

Despite the evolution of highly specific enzymes, modern metabolism retains numerous non-enzymatic reactions that occur either spontaneously or through metal catalysis [24]. These non-enzymatic reactions divide into three classes: (I) broad chemical reactivity with low specificity, (II) specific reactions occurring exclusively non-enzymatically, and (III) reactions occurring parallel to enzyme functions [24]. The retention of Class III reactions, which operate alongside enzymatic counterparts, demonstrates that enzyme constraints have shaped metabolic network evolution, with many enzymes functioning primarily to prevent undesirable side products rather than to enable thermodynamically favorable reactions [24].

Figure 1: Fundamental principles of enzyme constraints in cellular metabolism, showing physical and evolutionary factors that govern metabolic network structure and function.

Methodological Approaches for Incorporating Enzyme Constraints

Enzyme-Constrained Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (ecGEMs)

Several computational frameworks have been developed to incorporate enzyme constraints into genome-scale metabolic models, significantly improving phenotype predictions [21] [22]. The core mathematical formulation introduces an enzymatic constraint to traditional flux balance analysis:

[ \sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{vi \cdot MWi}{\sigmai \cdot k{cat,i}} \leq p{tot} \cdot f ]

where (vi) is metabolic flux, (MWi) is enzyme molecular weight, (k{cat,i}) is turnover number, (\sigmai) is enzyme saturation coefficient, (p_{tot}) is total protein fraction, and (f) is the mass fraction of enzymes [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Major ecGEM Construction Frameworks

| Framework | Mathematical Approach | Key Features | Organisms Applied |

|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO [22] | Enhances GEM with enzyme usage reactions | Automated BRENDA parameter retrieval; proteomics integration | S. cerevisiae, E. coli, H. sapiens |

| ECMpy [21] [18] | Direct enzyme constraint without S-matrix modification | Simplified workflow; machine learning kcat prediction | E. coli, M. thermophila, B. subtilis |

| AutoPACMEN [18] | Combined MOMENT and GECKO principles | Automatic enzyme data retrieval from databases | C. ljungdahlii, S. coelicolor |

| MOMENT [12] | Metabolic modeling with enzyme kinetics | Incorporates known enzyme kinetic parameters | E. coli, S. cerevisiae |

Experimental Protocol: Constructing an Enzyme-Constrained Model with ECMpy

Protocol 1: Enzyme-Constrained Model Construction Using ECMpy

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Model: Stoichiometric model in JSON or SBML format (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli)

- Enzyme Kinetic Parameters: kcat values from BRENDA, SABIO-RK, or machine learning prediction tools (TurNuP, DLKcat)

- Molecular Weight Data: Enzyme molecular weights from UniProt or model-specific databases

- Protein Content Constraint: Experimentally determined total enzyme mass fraction for target organism

Methodology:

- Model Preparation: Convert reversible reactions to irreversible representations to accommodate direction-specific kcat values [21].

- Enzyme Data Integration: Collect kcat values and molecular weights for each reaction enzyme:

- For isoenzymes: Split reaction into multiple isoenzyme-catalyzed reactions

- For enzyme complexes: Use minimum kcat/MW value among complex subunits [21]

- Constraint Formulation: Implement the enzyme capacity constraint using the equation above, with organism-specific ptot and f values [21].

- Parameter Calibration: Adjust kcat values to ensure biological consistency:

- Identify reactions with enzyme usage >1% of total enzyme content

- Correct reactions where 10% of total enzyme capacity yields flux below experimentally determined values [21]

- Model Simulation: Utilize COBRApy functions for constraint-based analysis and phenotype prediction [21].

Figure 2: Workflow for constructing enzyme-constrained metabolic models using computational frameworks such as ECMpy, showing key steps from initial model preparation to final application.

Applications and Biological Insights from Enzyme-Constrained Models

Predicting Overflow Metabolism and Substrate Utilization

Enzyme-constrained models have successfully explained the long-standing puzzle of overflow metabolism—the seemingly wasteful fermentation of glucose to acetate or ethanol even in the presence of oxygen [21] [23]. Traditional stoichiometric models predict pure respiratory metabolism as optimal, but ecGEMs reveal that under high carbon uptake rates, the enzyme cost of oxidative phosphorylation becomes prohibitive due to molecular crowding constraints [23]. For E. coli, ecGEMs have demonstrated that redox balance, not just glucose abundance, drives the transition to overflow metabolism [21].

Protocol for Predicting Metabolic Engineering Targets

Protocol 2: Identifying Enzyme Optimization Targets with ecGEMs

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Enzyme-Constrained Model: Validated ecGEM for target organism (e.g., ec_iHN637 for C. ljungdahlii)

- Flux Sampling Algorithm: OptKnock or similar constraint-based optimization tools

- Proteomics Data: (Optional) Absolute protein abundances for key enzymes

- Kinetic Parameter Database: Organism-specific kcat values for alternative enzyme variants

Methodology:

- Growth-Coupled Production Analysis: Use OptKnock framework to identify reaction knockouts that enhance product formation while maintaining growth capability [25].

- Enzyme Cost Evaluation: Calculate reaction enzyme cost using: [ \text{Reaction enzyme cost}i = \frac{vi \cdot MWi}{\sigmai \cdot k{cat,i}} ] and energy synthesis enzyme cost as: [ \text{Energy synthesis enzyme cost}i = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} \text{Reaction enzyme cost}i}{v_{net_generated_ATP}} ] [21]

- Enzyme Usage Efficiency Trade-off Analysis: Determine the optimal balance between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency by minimizing total enzyme amount while maximizing growth rate at varying substrate uptake rates [21].

- Implementation in C. ljungdahlii: For mixotrophic growth targeting acetate and ethanol overproduction, identify knockouts that redirect carbon flux while maintaining CO2 fixation capability [25].

Insights from Multi-Organism ecGEM Analysis

Large-scale implementation of enzyme constraints across multiple organisms has revealed fundamental principles of proteome allocation. Analysis of enzyme-constrained models for S. cerevisiae, Yarrowia lipolytica, and Kluyveromyces marxianus under stress conditions demonstrated consistent upregulation and high saturation of enzymes in amino acid metabolism, suggesting metabolic robustness rather than optimal protein utilization as a key cellular objective under nutrient limitation [22].

Table 3: Performance Improvements with Enzyme-Constrained Models

| Organism | Traditional GEM | Enzyme-Constrained GEM | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli [21] | iML1515 | eciML1515 | Accurate prediction of overflow metabolism and growth on 24 carbon sources |

| S. cerevisiae [22] | Yeast7 | ecYeast7 | Prediction of Crabtree effect and protein allocation profiles |

| C. ljungdahlii [25] | iHN637 | ec_iHN637 | Improved prediction of product profiles and mixotrophic growth |

| M. thermophila [18] | iYW1475 | ecMTM | Prediction of hierarchical carbon source utilization |

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

While enzyme-constrained models represent a significant advancement in metabolic modeling, several challenges remain. Kinetic parameter coverage, especially for less-studied organisms, requires improved machine learning approaches for kcat prediction [18] [22]. Integration of proteomics data enhances model accuracy but introduces technical variability that must be accounted for [22]. Future developments will likely focus on multi-scale models that incorporate transcriptional regulation, signaling networks, and metabolic adaptation over temporal scales [26].

The biological rationale for enzyme constraints extends beyond microbial systems to human metabolism and disease. Enzyme-constrained models of human cells have already provided insights into cancer metabolism and potential therapeutic targets [22], demonstrating the broad applicability of this fundamental principle across biological systems.

Enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) represent a significant advancement over traditional stoichiometric models by incorporating fundamental enzyme kinetic and proteomic constraints. These models rely on three core quantitative parameters to accurately simulate cellular metabolism: enzyme turnover numbers (kcat), molecular weights (MWs) of enzymes, and the total enzyme pool capacity. The integration of these constraints enables more accurate predictions of metabolic phenotypes, proteome allocations, and physiological diversity across different organisms and environmental conditions [27] [21].

The kcat value, or turnover number, defines the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time, serving as a direct measure of catalytic efficiency. Molecular weights determine the metabolic cost of enzyme synthesis, while the enzyme pool represents the finite cellular resources allocated to metabolic proteins. Together, these parameters constrain flux distributions through metabolic networks, explaining phenomena such as overflow metabolism and metabolic switches that traditional models fail to capture [21] [19].

This application note provides a comprehensive guide to the essential components of ecModels, including current methodologies for parameter acquisition, experimental protocols for kinetic characterization, and computational workflows for model construction and validation, framed within the context of ongoing research in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Core Components of ecModels

Key Parameter Definitions and Significance

Table 1: Essential Components of Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Role in ecModel | Common Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover Number | kcat |

Maximum substrate molecules converted per enzyme per second | Limits maximum flux through enzymatic reactions | sâ»Â¹ (or hâ»Â¹) |

| Molecular Weight | MW | Mass of one mole of the enzyme protein | Determines metabolic cost of enzyme synthesis | g/mmol |

| Enzyme Pool | P | Total mass fraction of proteome allocated to metabolic enzymes | Global constraint on all enzyme-catalyzed reactions | g/gDW |

The kcat value represents the intrinsic catalytic efficiency of an enzyme under saturating substrate conditions, defining the upper thermodynamic limit for reaction flux. Molecular weights determine the biosynthetic cost of producing and maintaining enzymes within the cell. The enzyme pool size represents the finite proteomic resources available for metabolic functions, creating competition between pathways for catalytic capacity [21] [19].

In ecModels, these parameters collectively implement the enzyme capacity constraint formalized in the following equation:

Where vi represents the flux through reaction i, σi is the enzyme saturation coefficient, ptot is the total protein content, and f is the mass fraction of enzymes in the proteome [21]. This constraint fundamentally alters model predictions by introducing protein allocation trade-offs that mirror biological reality.

Research Reagent and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for ecModel Development

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Repository of curated enzyme kinetic parameters | Primary source for experimental kcat and KM values |

| Kinetic Analysis Software | ICEKAT, renz (R package) | Calculate initial rates and kinetic parameters from raw data | Analysis of continuous enzyme kinetic assays |

| ecModel Construction Tools | ECMpy, GECKO, AutoPACMEN | Automated pipeline for building enzyme-constrained models | Integration of kinetic parameters into GEMs |

| kcat Prediction Tools | DLKcat, UniKP | Deep learning-based prediction of missing kcat values |

Genome-scale parameter estimation |

| Experimental Platforms | BMG LABTECH microplate readers | High-throughput kinetic measurements | Experimental determination of kinetic parameters |

These tools collectively enable researchers to acquire, analyze, and implement the core parameters required for ecModel construction. Database resources provide curated experimental values, analysis software facilitates parameter determination from raw data, and computational pipelines automate model construction and parameter integration [27] [21] [2].

Methodologies for Parameter Acquisition

Experimental Determination of kcat Values

Continuous Assay Protocol Using Microplate Readers

Materials:

- Purified enzyme solution

- Substrate stock solutions in appropriate buffer

- 96-well or 384-well microplates

- Microplate reader with temperature control and injectors (e.g., BMG LABTECH)

- Product standard solutions for calibration curve

Procedure:

- Prepare substrate dilutions spanning a concentration range typically from 0.1× to 10× the estimated KM value.

- Pipette 190 μL of assay buffer and 10 μL of enzyme preparation into each well.

- Program the microplate reader to inject 40 μL of substrate solution using onboard injectors.

- Configure absorbance measurements (e.g., 410 nm for p-nitrophenol assays) every second for 90 seconds at the optimal temperature (e.g., 37°C).

- Include appropriate controls: substrate without enzyme (autohydrolysis blank) and enzyme without substrate (negative control).

- Generate a product standard curve by measuring known concentrations of the reaction product under identical assay conditions [28].

Data Analysis:

- Convert raw absorbance values to product concentration using the extinction coefficient derived from the standard curve.

- Calculate initial velocities (vâ‚€) from the linear portion of the progress curve for each substrate concentration.

- Fit the [S] vs. vâ‚€ data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine KM and Vmax.

- Calculate

kcatusing the formula:kcat = Vmax / [E]total, where [E]total is the molar concentration of active enzyme [29] [28].

Software tools such as ICEKAT (Interactive Continuous Enzyme Analysis Tool) semi-automate initial rate calculations through multiple fitting modes, including Maximize Slope Magnitude, Linear Fit, Logarithmic Fit, and Schnell-Mendoza global fitting to the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation [29]. The R package 'renz' provides complementary analysis capabilities through both linear transformation methods and direct nonlinear regression, minimizing error propagation in parameter estimation [30].

Computational Prediction of Missing kcat Values

Deep Learning-Based Prediction (DLKcat):

For reactions lacking experimental kinetic data, deep learning approaches such as DLKcat predict kcat values using substrate structures and protein sequences as inputs. The methodology employs a graph neural network (GNN) for substrate representation and a convolutional neural network (CNN) for protein sequences, trained on curated datasets from BRENDA and SABIO-RK [27].

Protocol for Genome-Scale kcat Prediction:

- Data Curation: Compile enzyme kinetic data from BRENDA and SABIO-RK, filtering incomplete entries and ensuring unique substrate-enzyme pairs.

- Input Preparation: Convert substrates to molecular graphs from SMILES strings and split protein sequences into overlapping n-gram amino acids (typically 3-gram).

- Model Training: Configure optimal parameters (r-radius substrate subgraphs = 2; vector dimensionality = 20; time steps in GNN = 3; CNN layers = 3).

- Validation: Assess model performance using root mean square error (RMSE) and Pearson correlation coefficients on test datasets [27].

This approach has demonstrated a test set RMSE of 1.06, with predictions within one order of magnitude of experimental values, and successfully differentiates between native and underground metabolism substrates [27].

ecModel Construction Workflow

Automated Pipeline for ecModel Reconstruction

ECMpy Workflow Protocol:

- Model Preparation: Start with a genome-scale metabolic model in SBML format (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli).

- Reaction Processing: Split reversible reactions into forward and backward directions to accommodate direction-specific

kcatvalues. - Parameter Integration:

- Incorporate

kcatvalues from experimental data or computational predictions - Add enzyme molecular weights from UniProt annotations

- Define enzyme subunit composition for complex reactions

- Incorporate

- Constraint Implementation: Add the enzyme capacity constraint as a mass balance equation:

- Model Calibration: Adjust

kcatvalues and the enzyme pool size to fit experimental growth and flux data [21] [2].

Alternative tools such as AutoPACMEN implement simplified frameworks (sMOMENT) that reduce model complexity while maintaining predictive accuracy by directly incorporating enzyme constraints without adding numerous variables [19].

Model Validation and Quality Assessment

Protocol for ecModel Validation:

- Growth Rate Predictions: Simulate maximal growth rates across multiple carbon sources and compare with experimental measurements.

- Flux Predictions: Validate intracellular flux distributions against ¹³C fluxomics data where available.

- Proteome Comparisons: Compare predicted enzyme usage with experimental proteomics data.

- Phenotype Screens: Assess accuracy in predicting auxotrophies and substrate utilization patterns [21] [31].

The Bayesian calibration pipeline in DLKcat automatically adjusts parameters to improve consistency with experimental growth phenotypes and proteomic allocations [27].

Workflow Diagram

Workflow for ecModel Construction and Application

This workflow illustrates the integrated process for constructing ecModels, highlighting the critical role of kcat values, molecular weights, and enzyme pool parameters in transforming traditional GEMs into enzyme-constrained frameworks with enhanced predictive capabilities.

Applications in Metabolic Research

Predictive Phenotype Analysis

ecModels parameterized with accurate kcat values, molecular weights, and appropriate enzyme pool constraints significantly improve predictions of microbial growth phenotypes. For example, enzyme-constrained E. coli models have demonstrated superior accuracy in predicting growth rates on 24 single-carbon sources compared to traditional models [21]. Similarly, ecModels successfully explain overflow metabolism in E. coli and the Crabtree effect in S. cerevisiae by capturing the proteomic trade-offs between different metabolic pathways [21] [19].

Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology

The integration of enzyme constraints dramatically alters predicted optimal metabolic engineering strategies. By accounting for the metabolic cost of enzyme expression, ecModels identify different gene knockout targets compared to traditional models. For instance, enzyme-constrained models of Clostridium ljungdahlii have been used to identify knockout strategies for enhancing production of valuable metabolites under both syngas fermentation and mixotrophic growth conditions [32].

Physiological Diversity and Proteome Allocation

ecModels facilitate comparative analysis of metabolic strategies across different organisms by linking catalytic efficiency with proteome allocation. DLKcat-based analysis of 343 yeast species revealed how kcat differences contribute to physiological diversity and evolutionary adaptation [27]. These models enable quantitative prediction of how microorganisms allocate their limited proteomic resources to different metabolic pathways under varying environmental conditions.

The essential components of kcat values, molecular weights, and enzyme pools form the foundation of next-generation enzyme-constrained metabolic models. The integration of these parameters transforms traditional stoichiometric models into predictive frameworks that accurately capture proteome allocation constraints and metabolic trade-offs. Current methodologies combining experimental determination, computational prediction, and automated model construction have made ecModels increasingly accessible for researching diverse biological systems. As these approaches continue to mature, they promise to enhance both fundamental understanding of cellular metabolism and applied efforts in metabolic engineering and drug development.

Building and Applying ecModels: Methodologies and Real-World Implementations

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become powerful frameworks for predicting cellular phenotypes, but they possess a significant limitation: they consider only stoichiometric constraints, leading to predictions where growth and product yields increase linearly with substrate uptake rates, a pattern that often deviates from experimental observations [21] [33]. This discrepancy arises because traditional GEMs ignore the fundamental biological limitation of finite enzyme resources and their catalytic capacities. Enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) address this gap by incorporating enzymatic parameters, notably the turnover number (kcat) and enzyme molecular weight (MW), to impose additional constraints on metabolic fluxes, thereby generating more biologically realistic predictions [19] [34]. The integration of these constraints has proven essential for explaining critical metabolic phenomena, such as overflow metabolism in E. coli and the Crabtree effect in yeast, which cannot be accurately predicted by stoichiometric models alone [19] [21] [34]. Over the past decade, several computational toolboxes have been developed to automate the construction of ecModels, with GECKO, AutoPACMEN, and ECMpy representing three prominent approaches. This article provides a detailed comparison of these toolboxes, offering application notes and protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate framework for their specific biological research contexts.

Toolbox Comparison: Core Methodologies and Features

The GECKO, AutoPACMEN, and ECMpy toolboxes share the common goal of enhancing GEMs with enzyme constraints but employ distinct methodological approaches and offer different features, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of ecModel Construction Toolboxes

| Feature | GECKO | AutoPACMEN | ECMpy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Expands the stoichiometric matrix (S-matrix) with enzyme pseudometabolites and usage reactions [34] [35]. | Implements a simplified MOMENT (sMOMENT) approach; uses a single pooled enzyme constraint [19] [35]. | Adds a global enzyme amount constraint directly to the model without modifying the S-matrix [21] [33]. |

| Primary Input | A starting GEM in SBML format [34]. | A starting GEM in SBML format [19]. | A starting GEM (initially iML1515 for E. coli) [21]. |

| Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Acquisition | Manual curation and deep learning predictions [2] [34]. | Automated retrieval from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases [19] [35]. | Automated retrieval from databases (BRENDA, SABIO-RK) and machine learning prediction in v2.0 [2] [36]. |

| Handling of Protein Complexes | Explicitly considered in the model expansion [34]. | Requires correction of GPR rules and subunit composition for accurate MW [35]. | Requires consideration of subunit composition for accurate MW calculation [21] [35]. |

| Proteomics Data Integration | Direct integration of measured enzyme concentrations as flux constraints [34] [37]. | Can incorporate enzyme concentration measurements [19]. | Calculates enzyme mass fraction from proteomics data [21] [33]. |

| Key Output | An ecModel with expanded S-matrix [34]. | An sMOMENT model in standard constraint-based format [19]. | An enzyme-constrained model in JSON format compatible with COBRApy [21] [33]. |

| Model Tuning/Calibration | Includes a model tuning step to adjust parameters [34]. | Provides tools to adjust kcat and enzyme pool parameters based on flux data [19]. | Automated calibration of enzyme kinetic parameters based on enzyme usage and 13C flux data [21] [33]. |

The fundamental workflows for constructing ecModels with each toolbox can be visualized in the following diagrams, highlighting their distinct logical sequences.

Diagram 1: GECKO Toolbox Workflow

The GECKO workflow begins with a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) in SBML format. It first expands the model structure by adding enzyme pseudometabolites and reactions that represent enzyme usage. The next critical step is the integration of enzyme turnover numbers (kcat), which can be sourced from databases or deep learning predictions. The model then undergoes a tuning process to calibrate parameters, followed by the optional integration of proteomics data to further constrain enzyme levels. Finally, the tuned ecModel is used for simulation and analysis [34].

Diagram 2: AutoPACMEN Workflow

The AutoPACMEN workflow also starts with a GEM in SBML format. It includes a preprocessing step where reversible reactions are split. A key feature is the automatic retrieval of enzymatic data (kcat and molecular weights) from databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK. The core of the workflow is the application of the sMOMENT method, which incorporates enzyme constraints using a simplified, pooled approach. The model is then refined through parameter calibration using experimental flux data [19].

Diagram 3: ECMpy Workflow

The ECMpy workflow emphasizes simplicity. After starting with a GEM, it involves preprocessing the model and correcting Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules to ensure accurate protein complex representation. It then gathers kcat values, with version 2.0 leveraging machine learning to enhance parameter coverage. The central step is to add a global enzyme amount constraint directly to the model without altering the stoichiometric matrix. This is followed by an automated calibration process based on principles of enzyme usage and consistency with 13C flux data, resulting in an ecModel stored in JSON format for simulation with standard tools like COBRApy [21] [2] [33].

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Constructing an ecModel with GECKO 3.0

The following detailed protocol, adapted from the Nature Protocols publication, outlines the construction of an ecModel using GECKO 3.0 [34].

Stage 1: ecModel Structure Expansion

- Input Preparation: Obtain a high-quality GEM for your target organism in SBML format. Ensure that gene identifiers are consistent with a source that can be mapped to UniProt IDs for accurate enzyme assignment.

- Model Enhancement: Use the GECKO functions to expand the base model. This involves:

- Adding enzymatic reactions as new columns to the S-matrix.

- Introducing enzyme pseudometabolites as new rows.

- Defining exchange reactions for each enzyme to represent their usage.

- Total Protein Pool: Introduce a metabolite representing the total protein pool and a reaction that draws from this pool to supply the required enzymes.

Stage 2: Integration of Enzyme Turnover Numbers

- kcat Collection: Collect turnover numbers for as many enzyme-catalyzed reactions as possible. GECKO 3.0 facilitates this by incorporating deep learning-predicted kcat values, which are particularly valuable for organisms with limited experimental data [34].

- kcat Assignment: Match the collected kcat values to the corresponding enzymatic reactions in the model. For reactions without a specific kcat, implement a decision process (e.g., using the minimum, maximum, or median kcat from isozymes, or employing a geometric mean of kcat values from similar organisms).

Stage 3: Model Tuning

- Simulate Growth: Perform a simulation to predict the maximal growth rate using the ecModel.

- Adjust Total Enzyme Pool: Compare the simulated growth rate with experimental data. If the prediction is too low, the total enzyme pool might be underestimated; if it is too high, the pool might be overestimated. Adjust the total protein pool constraint accordingly.

- Fit kcat Values: Systematically adjust the kcat values for reactions that are identified as flux-limited, ensuring that the model can achieve experimentally observed growth rates and flux distributions.

Stage 4: Integration of Proteomics Data

- Data Input: Incorporate absolute proteomics measurements if available.

- Apply Constraints: Use the proteomics data to set upper bounds for the respective enzyme usage reactions, thereby constraining the maximum flux based on the measured enzyme abundance [34] [37].

Stage 5: Simulation and Analysis

- Phenotype Prediction: Use the finalized ecModel to run simulations such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict growth rates, nutrient uptake, and byproduct secretion under different conditions.

- Advanced Analysis: Leverage the ecModel for more complex analyses, including flux variability analysis (FVA), and prediction of metabolic engineering targets.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The construction and validation of ecModels rely on a combination of computational tools and biological data resources. The table below details essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ecModel Construction

| Resource Type | Name | Function in ecModel Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Database | BRENDA [19] [35] | A comprehensive enzyme database providing curated kcat values for a vast number of enzymes from diverse organisms. |

| Kinetic Database | SABIO-RK [19] [35] | A database specializing in biochemical reaction kinetics, including kinetic parameters and related rate laws. |

| Machine Learning Tool | TurNuP [18] / DLKcat [2] | Predicts kcat values for enzyme-metabolite pairs, filling gaps in experimental data and enabling ec construction for less-studied organisms. |

| Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox [34] | A MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling. Essential for simulating and analyzing models built with GECKO. |

| Modeling Software | COBRApy [21] [33] | A Python version of the COBRA toolbox, used as the simulation backend for ECMpy-generated models. |

| Protein Database | UniProt [35] | Provides protein sequences, functional information, and crucially, molecular weights (MW) for enzymes, which are needed to calculate enzyme mass constraints. |

| Complex Database | Complex Portal [35] | A resource of macromolecular complexes, which aids in determining the correct subunit composition for accurate molecular weight calculation. |

Case Studies and Applications in Research

The practical utility of ecModels is demonstrated by their successful application across various organisms to predict metabolic phenotypes and identify engineering targets.

- Predicting Overflow Metabolism in E. coli: The ECMpy toolbox was used to construct an enzyme-constrained model for E. coli, eciML1515. This model accurately simulated overflow metabolism—the production of acetate under high glucose conditions—which the standard stoichiometric model could not explain. By analyzing enzyme costs, the model revealed that redox balance, rather than just ATP yield, is a key driver of this metabolic switch in E. coli [21] [33].

- Guiding Metabolic Engineering for Amino Acid Production: An enzyme-constrained model for Corynebacterium glutamicum (ecCGL1) was built using the ECMpy workflow. This model was employed to identify gene knockout and overexpression targets for enhancing L-lysine production. The predictions from ecCGL1 were consistent with previously reported successful genetic modifications, validating the model's utility in providing reliable guidance for metabolic engineering [35].

- Simulating Substrate Hierarchy in a Filamentous Fungus: The first ecModel for Myceliophthora thermophila (ecMTM) was constructed using ECMpy with machine learning-predicted kcat values. This model successfully captured the hierarchical utilization of five different carbon sources derived from plant biomass hydrolysis, a phenomenon that is difficult to predict with traditional GEMs. Furthermore, ecMTM predicted new potential metabolic engineering targets for chemical production in this industrially relevant fungus [18].

The adoption of enzyme constraints has undeniably enhanced the predictive power of genome-scale metabolic models. GECKO, AutoPACMEN, and ECMpy offer robust, automated pathways to this end. The choice among them depends on the specific research goals, available data, and desired model characteristics.

- Select GECKO when seeking a highly detailed and mechanistically explicit representation of enzyme usage, when proteomics data integration is a key component of the study, and when working within a MATLAB/COBRA Toolbox environment [34].