Enzyme-Constrained vs Stoichiometric Models: A Performance Guide for Biomedical Researchers

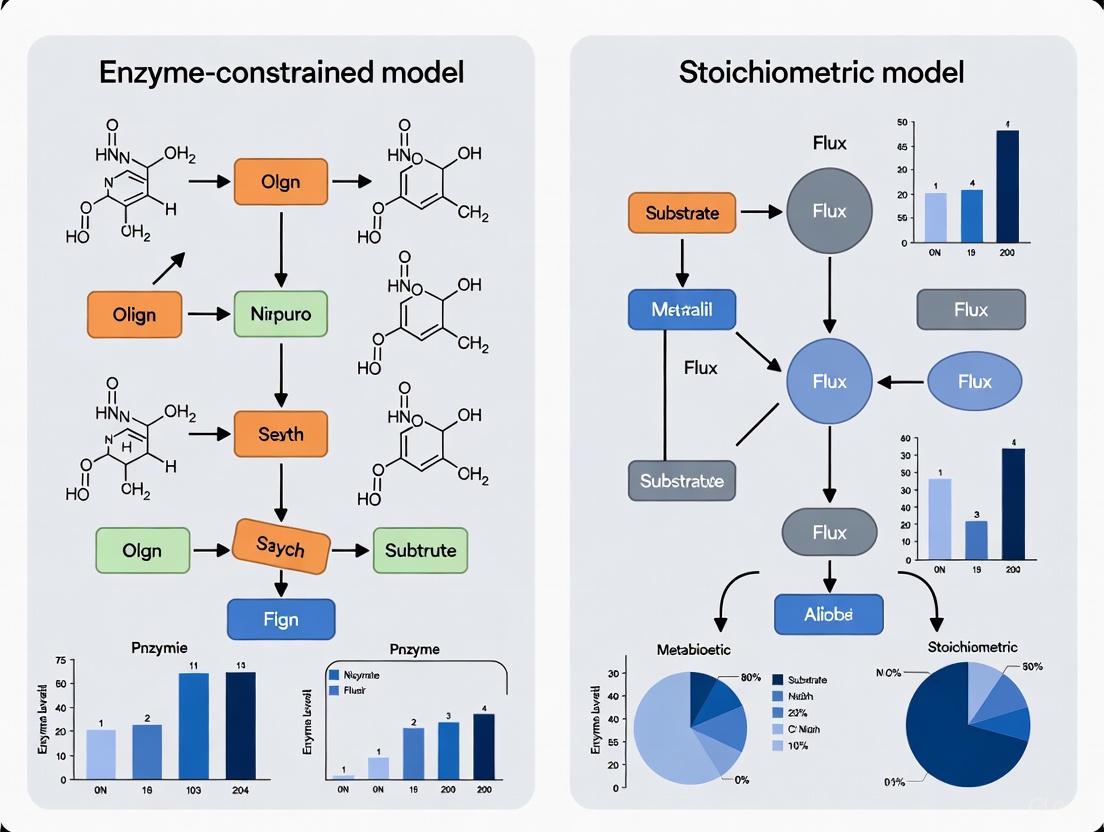

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the performance and application of enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) versus traditional stoichiometric models.

Enzyme-Constrained vs Stoichiometric Models: A Performance Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the performance and application of enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) versus traditional stoichiometric models. We explore the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling, detail the methodologies for constructing and applying ecModels with tools like GECKO and ECMpy, and address key optimization challenges such as parameterization and integration of proteomic data. Through comparative validation, we demonstrate how ecModels significantly improve prediction accuracy for phenotypes, proteome allocation, and metabolic engineering strategies, offering enhanced reliability for biomedical and clinical research applications.

Core Principles: From Stoichiometric Balances to Enzyme Constraints

The Basis of Constraint-Based Stoichiometric Modeling

Constraint-Based Stoichiometric Modeling is a cornerstone of systems biology, providing a computational framework to predict metabolic behavior by leveraging the stoichiometry of biochemical reaction networks. The core principle of this approach is the use of mass balance constraints and the steady-state assumption to define the set of all possible metabolic flux distributions achievable by an organism [1] [2]. Unlike kinetic models that require detailed enzyme parameter information and can simulate dynamics, stoichiometric models focus on predicting steady-state fluxes, making them particularly suitable for genome-scale analyses where comprehensive kinetic data are unavailable [1] [3].

These models are mathematically represented by the equation S·v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix containing the coefficients of all metabolic reactions, and v is the vector of metabolic fluxes [2]. This equation, combined with constraints on reaction directionality (α ≤ v ≤ β) and uptake/secretion rates, defines the solution space of possible metabolic phenotypes [1] [2]. The most common analysis method, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), identifies a particular flux distribution within this space by optimizing an objective function, typically biomass production, which represents cellular growth [4] [2].

Stoichiometric models have evolved from small-scale pathway analyses to comprehensive genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) that encompass the entire known metabolic network of an organism [1] [2]. This expansion has been fueled by growing genome annotation data and their demonstrated utility in biotechnology and biomedical research, from guiding metabolic engineering strategies to informing drug discovery [5] [2].

Core Constraints in Stoichiometric Modeling

The predictive power of constraint-based models derives from the systematic application of physicochemical and biological constraints that restrict the solution space to physiologically relevant flux distributions.

Fundamental Physicochemical Constraints

- Mass Balance Constraints: The foundational constraint requires that for each internal metabolite, the rate of production equals the rate of consumption at steady state, formalized as S·v = 0 [1] [2]. This ensures compliance with the law of mass conservation.

- Energy Balance Constraints: Derived from the first law of thermodynamics, these constraints account for energy conservation in the system, though they are less frequently implemented than mass balance in standard formulations [1].

- Thermodynamic Constraints: These constraints enforce reaction directionality based on Gibbs free energy calculations, ensuring fluxes proceed only in thermodynamically favorable directions under given metabolite concentrations [1] [4]. Implementation often requires metabolomics data to estimate metabolic concentrations [4].

Biological and System-Level Constraints

- Reaction Directionality and Capacity Constraints: Based on enzyme characteristics and cellular conditions, each flux vi is bounded between lower (αi) and upper (βi) limits (αi ≤ vi ≤ βi) [1] [2].

- Stoichiometric Modeling Assumptions: The steady-state assumption is essential, positing that internal metabolite concentrations remain constant over time despite ongoing metabolic activity [1]. This assumption is valid when metabolic transients are rapid compared to cellular growth or environmental changes.

Table 1: Classification of Constraints in Stoichiometric Models

| Constraint Category | Basis | Application Preconditions | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Constraints | Universal physicochemical principles | Applicable to any biochemical system | [1] |

| Organism-Level Constraints | Organism-specific physiological limitations | Require knowledge of specific organism | [1] |

| Experiment-Level Constraints | Specific experimental conditions | Require details of experimental setup | [1] |

The Emergence of Enzyme-Constrained Modeling

While traditional stoichiometric models have proven valuable, they often fail to predict suboptimal metabolic behaviors such as overflow metabolism, where organisms partially oxidize substrates despite oxygen availability [6]. This limitation stems from their inability to account for protein allocation costs and enzyme kinetics [3] [6]. Enzyme-constrained models address this gap by incorporating fundamental limitations on cellular proteome resources.

Theoretical Foundation

The central premise of enzyme-constrained modeling is that flux through each metabolic reaction is limited by the amount and catalytic capacity of its corresponding enzyme(s). This relationship is formalized as vi ≤ kcat,i · ei, where kcat,i is the enzyme's turnover number and ei represents enzyme concentration [7] [6]. A global proteome limitation is typically imposed through the constraint ∑ ei · MWi ≤ P · f, where MWi is the molecular weight of enzyme i, P is the total protein content, and f is the mass fraction of metabolic enzymes [7] [6].

These constraints introduce fundamental trade-offs in metabolic optimization: cells must balance the catalytic efficiency of their enzymes with the biosynthetic cost of producing them, leading to seemingly suboptimal flux distributions that maximize overall fitness under proteome limitations [6].

Implementation Approaches

Several computational frameworks have been developed to integrate enzyme constraints into stoichiometric models:

- GECKO (Genome-scale model with Enzyme Constraints using Kinetics and Omics): Expands the stoichiometric matrix with enzyme pseudometabolites and incorporates enzyme kinetics via kcat values, allowing integration of absolute proteomics data [4] [6].

- MOMENT (Metabolic Modeling with Enzyme Kinetics): Uses the same fundamental enzyme constraints but with a different mathematical formulation [7].

- sMOMENT (short MOMENT): A simplified version that reduces model complexity while maintaining predictive accuracy, enabling more efficient computation [7].

- ECMpy: A Python-based workflow that simplifies construction of enzyme-constrained models without modifying existing metabolic reactions [6].

- ET-OptME: A recently developed framework that simultaneously applies both enzyme and thermodynamic constraints for improved prediction accuracy [8] [4].

Performance Comparison: Stoichiometric vs. Enzyme-Constrained Models

Direct comparisons between traditional stoichiometric and enzyme-constrained models reveal significant differences in predictive performance across multiple applications.

Prediction of Metabolic Phenotypes

Enzyme-constrained models demonstrate superior accuracy in predicting microbial growth rates across different nutrient conditions. In E. coli, enzyme-constrained implementations such as eciML1515 show significantly improved correlation with experimental growth rates on 24 single carbon sources compared to traditional stoichiometric models [6]. Similar improvements have been documented for S. cerevisiae models, with enzyme constraints enabling quantitative prediction of the Crabtree effect (the switch to fermentative metabolism at high glucose uptake rates) without explicitly bounding substrate uptake rates [7] [6].

Perhaps most notably, enzyme-constrained models successfully explain overflow metabolism, a phenomenon where cells produce byproducts like acetate or ethanol during aerobic growth on glucose—behavior that traditional FBA fails to predict under assumption of optimality [6]. Analysis using E. coli enzyme-constrained models revealed that redox balance, rather than solely enzyme costs, drives differences in overflow metabolism between E. coli and S. cerevisiae [6].

Metabolic Engineering Applications

Enzyme constraints substantially alter predicted optimal metabolic engineering strategies. For example, when optimizing E. coli models for sucrose accumulation, the introduction of enzyme constraints dramatically reduced the theoretically possible objective function value from 2.6×10^6 to 4.7, while simultaneously eliminating unrealistic predictions of 1500-fold metabolite concentration increases [1]. This demonstrates how enzyme constraints guide more realistic and practically implementable engineering strategies.

Studies systematically comparing engineering target predictions have found that enzyme constraints can "markedly change the spectrum of metabolic engineering strategies for different target products" [7]. The ET-OptME framework, which integrates both enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic constraints, demonstrated at least 70-292% improvement in precision and 47-106% improvement in accuracy compared to traditional stoichiometric methods across five product targets in Corynebacterium glutamicum models [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Modeling Approaches

| Performance Metric | Traditional Stoichiometric | Enzyme-Constrained | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate Prediction | High error across conditions | Significant improvement on 24 carbon sources | [6] |

| Overflow Metabolism | Cannot predict without artificial constraints | Naturally emerges from constraints | [7] [6] |

| Engineering Strategy Precision | Baseline | 70-292% increase | [8] |

| Engineering Strategy Accuracy | Baseline | 47-106% increase | [8] |

| Computational Complexity | Lower | Higher, but mitigated by sMOMENT/ECMpy | [7] [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Model Construction

Workflow for Enzyme-Constrained Model Construction

The construction of enzyme-constrained models follows a systematic workflow that enhances standard stoichiometric models with proteomic and kinetic data.

Model Construction Workflow

Key Methodological Steps

- Base Model Preparation: Start with a validated stoichiometric model in SBML format. Irreversible reactions are preferred, so reversible reactions are typically split into forward and backward components with separate enzyme constraints [7] [6].

- Enzyme Kinetic Data Integration: Collect enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) and molecular weights (MW) from databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK [7] [6]. For reactions catalyzed by enzyme complexes, use the minimum kcat/MW ratio among subunits; for isoenzymes, create separate reaction entries [6].

- Proteomic Constraints Implementation: Incorporate either global or enzyme-specific constraints. The global protein pool constraint takes the form: ∑(vi · MWi)/(kcat,i · σi) ≤ P · f, where σi is the enzyme saturation coefficient and f is the fraction of total proteome allocated to metabolic enzymes [6].

- Parameter Calibration: Adjust kcat values to ensure consistency with experimental flux data. Reactions whose enzyme usage exceeds 1% of total enzyme content or where predicted flux falls below 13C-measured values require parameter adjustment [6].

- Model Validation: Validate predictions against experimental growth rates, flux distributions, and metabolic phenotypes across multiple conditions [6].

Data Reconciliation in Enzyme-Constrained Models

A significant challenge in enzyme-constrained modeling is reconciling proteomic data with metabolic flux predictions, as raw proteomic measurements often yield infeasible models [4]. The geckopy 3.0 package addresses this with relaxation algorithms that identify minimal adjustments to proteomic constraints needed to achieve model feasibility, implemented as linear or mixed-integer linear programming problems [4].

Successful implementation of constraint-based modeling requires specialized computational tools and data resources.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Constraint-Based Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Construction | COBRApy, RAVEN Toolbox | Stoichiometric model development and analysis | Reaction addition, gap-filling, simulation [7] |

| Enzyme Constraints | GECKO, ECMpy, AutoPACMEN | Integration of enzyme kinetics into models | kcat integration, proteomic constraints [7] [6] |

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Source of enzyme kinetic parameters | kcat, Km values with organism-specific annotations [7] [6] |

| Thermodynamic Constraints | pytfa, geckopy 3.0 | Add thermodynamic feasibility constraints | Gibbs energy calculations, directionality [4] |

| Model Standards | SBML, FBC package | Model representation and exchange | Community standards, interoperability [4] [2] |

Integrated Modeling Frameworks and Future Directions

The field is evolving toward multi-constraint frameworks that simultaneously incorporate multiple layers of biological limitations. The ET-OptME framework exemplifies this trend, demonstrating that combined enzyme and thermodynamic constraints yield better predictions than either constraint alone [8]. Similarly, geckopy 3.0 provides an integration layer with pytfa to simultaneously apply enzyme, thermodynamic, and metabolomic constraints [4].

These integrated approaches recognize that cellular metabolism is subject to multiple competing limitations: stoichiometric balances, proteome allocation constraints, thermodynamic feasibility, and spatial constraints [1] [4]. The resulting models provide more accurate predictions and deeper biological insights, albeit with increased computational complexity and data requirements.

Future directions include the development of more automated workflows for model construction, improved databases of enzyme parameters with better organism coverage, and methods for efficiently integrating multiple omics data types [7] [4] [6]. As these tools mature, they will further bridge the gap between theoretical metabolic potential and experimentally observed physiological behavior.

Constraint Integration Pathway

Constraint-based metabolic models, particularly Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), have become indispensable tools for predicting cellular behavior in biotechnology and biomedical research. These models traditionally rely on chemical stoichiometry, mass balance, and steady-state assumptions to define a space of feasible metabolic flux distributions. However, this traditional stoichiometric approach fundamentally overlooks two critical aspects of cellular physiology: reaction thermodynamics and enzyme resource costs.

The absence of these constraints represents a significant limitation, as cells operate under strict thermodynamic laws and face finite proteomic resources. Models that ignore these factors often predict physiologically impossible flux states and fail to recapitulate well-known metabolic phenomena, ultimately reducing their predictive accuracy and utility for strain design and drug development. This review objectively compares the performance of traditional stoichiometric models against emerging enzyme-constrained and thermodynamics-integrated approaches, examining the experimental evidence that highlights the critical importance of these previously neglected constraints.

Fundamental Limitations of Traditional Stoichiometric Models

The Sole Reliance on Chemical Stoichiometry

Traditional stoichiometric models are built primarily on the foundation of mass balance. The core mathematical representation is the equation Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix containing the coefficients of each metabolite in every reaction, and v is the vector of metabolic fluxes [4]. This equation, combined with reaction directionality constraints and uptake/secretion rates, defines the solution space. The primary analysis method, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), identifies a particular flux distribution within this space by optimizing an objective function, typically biomass formation for microbial growth simulation [4] [1].

While this framework is powerful for analyzing large networks, its simplicity is its main weakness. By considering only stoichiometry, it implicitly assumes that any flux distribution satisfying mass balance is equally feasible for the cell, provided sufficient substrate is available. This ignores the kinetic and thermodynamic barriers that fundamentally shape real metabolic networks.

The Critical Omissions: Enzyme Costs and Thermodynamics

Traditional models lack mechanisms to account for two fundamental biological realities:

Enzyme Resource Costs: Cells have limited capacity for protein synthesis and allocation. Catalyzing any metabolic reaction requires the expression of its corresponding enzyme, which consumes cellular resources (energy, amino acids, ribosomal capacity) and occupies physical space. Traditional stoichiometric models completely ignore this protein allocation cost, treating enzymes as invisible, free catalysts [1] [7].

Reaction Thermodynamics: Every biochemical reaction is governed by thermodynamics, specifically the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG). A reaction can only carry a positive flux in the direction of negative ΔG. Traditional models often use reaction reversibility assignments based on database annotations but fail to dynamically assess the thermodynamic feasibility of flux distributions under specific metabolite concentration conditions [4] [1].

The failure to incorporate these constraints leads to predictions that violate basic principles of cellular physiology, reducing the practical utility of these models for researchers and developers who require accurate predictions of cellular behavior.

Advanced Constrained Models: Integrating Physiology

To overcome these limitations, next-generation models incorporate additional layers of physiological constraints, significantly enhancing their predictive accuracy and biological relevance.

Enzyme-Constrained Models (ECMs)

ECMs explicitly incorporate the protein cost of metabolism. The core principle is that the flux through an enzyme-catalyzed reaction ((vi)) cannot exceed the product of the enzyme's concentration ((gi)) and its turnover number ((k{cat,i})): (vi \leq k{cat,i} \cdot gi) [7]. A global constraint reflects the limited total protein budget of the cell, often formulated as (\sum gi \cdot MWi \leq P), where (MW_i) is the molecular weight of the enzyme and (P) is the total enzyme mass per cell dry weight [7].

Several implementations exist, including:

- GECKO: Extends GEMs by adding enzyme pseudometabolites and associated reactions, allowing direct integration of absolute proteomics data [4] [7].

- MOMENT/sMOMENT: Incorporates enzyme allocation constraints using a different mathematical formulation, which can be simplified (sMOMENT) to reduce computational complexity while yielding equivalent predictions [7].

Thermodynamics-Constrained Models

These models integrate the second law of thermodynamics to ensure that flux solutions are energy-feasible. The key addition is the constraint on the Gibbs free energy: a reaction can only carry flux in the direction of negative ΔG. The Thermodynamics-based Flux Analysis (TFA) method incorporates reaction Gibbs free energies ((\Delta G_r)), which are functions of metabolite concentrations, as constraints into the model [4] [1]. This not only eliminates thermodynamically infeasible cycles but also allows for the integration of metabolomics data to define more realistic metabolite concentration ranges.

Hybrid Multi-Constraint Frameworks

The most recent advances involve the simultaneous application of multiple constraints. The ET-OptME framework is a leading example, systematically integrating both Enzyme and Thermodynamic constraints into a single model [9] [8]. It features two core algorithms: ET-EComp, which identifies enzymes to up/down-regulate by comparing different physiological states, and ET-ESEOF, which scans for regulatory signals as target flux is forced to increase [9]. This hybrid approach aims to capture the synergistic effect of these constraints on cellular metabolism.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Rigorous benchmarking studies provide experimental data demonstrating the performance gains achieved by incorporating enzyme and thermodynamic constraints.

The table below summarizes the performance improvements of the ET-OptME framework over traditional and single-constraint models for predicting metabolic engineering targets in Corynebacterium glutamicum across five industrial products [9] [8].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Model Types in Predicting Metabolic Engineering Targets

| Model Type | Increase in Minimal Precision vs. Stoichiometric Models | Increase in Accuracy vs. Stoichiometric Models | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Stoichiometric (e.g., OptForce, FSEOF) | Baseline | Baseline | Low computational cost; simple to implement |

| Thermodynamics-Constrained | ≥ 161% | ≥ 97% | Eliminates thermodynamically infeasible solutions |

| Enzyme-Constrained | ≥ 70% | ≥ 47% | Predicts enzyme allocation; explains overflow metabolism |

| Hybrid Enzyme- & Thermodynamic-Constrained (ET-OptME) | ≥ 292% | ≥ 106% | Highest physiological realism; overcomes metabolic bottlenecks |

Explaining Physiological Phenomena

The table below compares the ability of different model types to explain and predict key metabolic behaviors observed in real cells.

Table 2: Capabilities of Model Types to Explain Specific Metabolic Phenomena

| Metabolic Phenomenon | Traditional Stoichiometric Models | Enzyme-Constrained Models | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overflow Metabolism (e.g., Crabtree Effect) | Cannot predict without arbitrary flux bounds | Accurately predicts as optimal resource allocation | Explained in E. coli and S. cerevisiae with GECKO/sMOMENT [7] [9] |

| Metabolic Switches/Phase Transitions | Poor prediction | High prediction accuracy | Demonstrated in E. coli models [7] |

| Growth Rate/Yield Trade-offs | Partially captured | Accurately predicts based on enzyme allocation costs | Validated across multiple carbon sources [7] [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical roadmap, this section details the key experimental and computational protocols used in the cited studies.

Workflow for Constructing an Enzyme-Constrained Model

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for enhancing a traditional GEM with enzyme constraints using tools like AutoPACMEN or the GECKO method.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Constructing an Enzyme-Constrained Model

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Initial Curation: Begin with a high-quality, well-annotated GEM in SBML format. Preprocessing often involves splitting reversible reactions into forward and backward components to assign distinct (k_{cat}) values [7].

- Data Retrieval: Automatically or manually retrieve enzyme kinetic data ((k_{cat}) values) and molecular weights (MW) from databases such as BRENDA and SABIO-RK. This can be automated with toolboxes like AutoPACMEN [7].

- Model Extension: The core structural change. Following the GECKO approach, extend the stoichiometric matrix S by adding:

- Enzyme Pseudometabolites: New metabolite entries representing each enzyme.

- Enzyme Usage Reactions: For each enzyme-catalyzed reaction

i, add the enzyme as a reactant with a stoichiometric coefficient of (1/k_{cat,i}) [4] [7]. - Enzyme Exchange Reactions: Pseudo-reactions that supply each enzyme, with upper bounds set by experimental proteomics data if available.

- Constraint Application: Apply the total enzyme capacity constraint: (\sum (vi / k{cat,i}) \cdot MW_i \leq P), where

Pis the measured total protein content mass per gram of cell dry weight [7]. This can be implemented directly or via a protein pool reaction. - Model Calibration: Adjust uncertain (k_{cat}) values and the global protein pool size

Pto fit experimental growth rates and flux data. This ensures the model accurately reflects the organism's physiology [7].

Protocol for Thermodynamics Integration (TFA)

The integration of thermodynamic constraints follows a distinct pathway, as shown below.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Integrating Thermodynamic Constraints

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Directionality Assignment: Review and curate the reversibility assignments for all model reactions based on literature and database information [1].

- Thermodynamic Data Collection: Compile standard Gibbs free energies of formation ((\Delta G_f^\circ)) for all metabolites in the model from databases or group contribution methods [1].

- Concentration Bounds: Define physiologically plausible minimum and maximum concentrations for intracellular metabolites. These can be informed by metabolomics data or literature values [4] [1].

- Gibbs Free Energy Calculation: For each reaction, calculate the actual Gibbs free energy ((\Delta Gr)) as (\Delta Gr = \Delta G_r^\circ + RT \ln(Q)), where

Qis the reaction quotient. The value ofQdepends on the variable metabolite concentrations [1]. - Constraint Implementation: Integrate these calculations as constraints in the model. For a reaction to carry a positive flux, (\Delta G_r < 0) must hold, and vice-versa. This is typically enforced using a mixed-integer linear programming formulation [4] [1].

The successful development and application of advanced constraint-based models rely on a suite of computational tools, databases, and software.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Constraint-Based Modeling Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA | Database | Comprehensive enzyme kinetic data ((k{cat}), (Km)) | Primary source for (k_{cat}) values in enzyme-constrained models [7] |

| SABIO-RK | Database | Kinetic data and reaction parameters | Alternative source for enzyme kinetic data [7] |

| AutoPACMEN | Software Toolbox | Automated construction of ECMs | Automates retrieval of kinetic data and model extension for various organisms [7] |

| geckopy 3.0 | Software Package | Python layer for enzyme constraints | Manages enzyme constraints, integrates with pytfa for thermodynamics, and reconciles proteomics data [4] |

| pytfa | Software Library | Thermodynamic Flux Analysis (TFA) in Python | Adds thermodynamic constraints to metabolic models [4] |

| CAC Platform | Cloud Platform | Multi-scale model construction (Carve/Adorn/Curate) | Simplifies building models with multiple constraints using a machine-learning aided strategy [11] |

| ET-OptME | Algorithmic Framework | Metabolic target prediction with enzyme & thermo constraints | Provides a ready-to-use framework for high-precision strain design [9] [8] |

The evidence from comparative studies is unequivocal: traditional stoichiometric models are fundamentally limited by their neglect of enzyme allocation costs and thermodynamic feasibility. The integration of these constraints is not merely a refinement but a necessary step toward achieving physiologically realistic simulations. Quantitative benchmarks show that hybrid frameworks like ET-OptME can improve prediction precision by nearly 300% compared to traditional methods [9] [8].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the implications are clear. The adoption of enzyme-constrained and thermodynamics-integrated models significantly de-risks metabolic engineering and discovery projects by providing more reliable and actionable predictions. While these advanced models require more extensive data and computational power, the availability of automated toolboxes like AutoPACMEN and geckopy is steadily lowering the barrier to entry. As the field moves forward, the continued development and application of multi-constraint models represent the path toward a more predictive and accurate understanding of cellular metabolism.

Constraint-Based Modelling (CBM) has established itself as a powerful framework for predicting cellular behavior by applying mass-balance constraints to stoichiometric representations of metabolic networks [12]. However, traditional stoichiometric models, while valuable for predicting steady-state fluxes, lack crucial biological details that limit their predictive accuracy. They operate on the assumption that reactions are constrained only by stoichiometry and reaction directionality, ignoring the fundamental biological reality that enzymes—with their specific catalytic efficiencies and finite cellular concentrations—actually catalyze these reactions [1] [12].

The integration of enzyme constraints represents a paradigm shift in metabolic modelling, moving beyond mere stoichiometry to incorporate fundamental principles of enzyme kinetics and proteome allocation. This approach explicitly recognizes that metabolic fluxes are not merely stoichiometrically feasible but must also be catalytically achievable given the cell's finite resources for enzyme synthesis [12]. The cornerstone parameters enabling this advancement are the enzyme turnover number (kcat), which quantifies catalytic efficiency, and enzyme mass, which represents the proteomic investment required for catalysis [13] [12]. This comparative guide examines how incorporating these constraints transforms model predictions and performance compared to traditional stoichiometric approaches.

Theoretical Foundation: The Core Constraints

The Fundamental Parameters

Enzyme-constrained models introduce two pivotal constraints that tether theoretical metabolic capabilities to physiological realities:

kcat(Turnover Number): This kinetic parameter defines the maximum number of substrate molecules an enzyme molecule can convert to product per unit time, typically expressed as sâ»Â¹ [12]. It represents the intrinsic catalytic efficiency of an enzyme. In modelling terms, the flux (v_i) through an enzyme-catalyzed reaction is limited by the product of the enzyme concentration (g_i) and itskcatvalue:v_i ≤ kcat_i • g_i[12].Enzyme Mass Constraint: This encapsulates the fundamental proteomic limitation of the cell. The total mass of metabolic enzymes cannot exceed a defined maximum capacity (

P), formalized as:Σ (g_i • MW_i) ≤ PwhereMW_iis the molecular weight of each enzyme [12]. This constraint reflects the cellular trade-off between producing different enzymes within a limited proteomic budget.

From Principles to Mathematical Implementation

The synergy between these constraints creates the enzyme mass balance. By substituting the flux-enzyme relationship into the total enzyme mass constraint, we derive the core inequality governing enzyme-constrained models: Σ (v_i • MW_i / kcat_i) ≤ P [12]. This simple yet powerful expression couples the flux through each metabolic reaction directly to the proteomic resources required to achieve it, creating a natural feedback that prevents biologically unrealistic flux distributions.

Table 1: Core Constraints in Metabolic Models

| Constraint Type | Mathematical Representation | Biological Principle | Role in Modelling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Constraints | S • v = 0 |

Mass conservation | Ensures mass balance for all metabolites in the network |

| Enzyme Kinetic Constraint | v_i ≤ kcat_i • g_i |

Enzyme catalytic efficiency | Links reaction flux to enzyme concentration and efficiency |

| Enzyme Mass Constraint | Σ (g_i • MW_i) ≤ P |

Finite proteomic capacity | Limits total enzyme investment across all metabolic reactions |

Performance Comparison: Enzyme-Constrained vs. Stoichiometric Models

Quantitative Improvements in Prediction Accuracy

Multiple studies have demonstrated that incorporating enzyme constraints significantly enhances the predictive performance of metabolic models across diverse organisms and conditions. The ET-OptME framework, which systematically integrates enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic feasibility constraints, shows remarkable improvements over traditional approaches. When evaluated on five product targets in Corynebacterium glutamicum, this enzyme-constrained approach demonstrated at least a 292% increase in minimal precision and a 106% increase in accuracy compared to classical stoichiometric methods [8].

Similarly, the construction of an enzyme-constrained model for Myceliophthora thermophila (ecMTM) using machine learning-predicted kcat values resulted in a reduced solution space with growth simulations that more closely resembled realistic cellular phenotypes [13]. The model successfully captured hierarchical carbon source utilization patterns—a critical phenomenon in microbial metabolism that traditional stoichiometric models often fail to predict accurately.

Qualitative Advantages in Capturing Metabolic Behaviors

Beyond numerical accuracy, enzyme-constrained models exhibit superior capability in capturing complex metabolic behaviors:

Overflow Metabolism: Traditional models require artificial bounds to explain phenomena like aerobic fermentation (Crabtree effect) in yeast or acetate overflow in E. coli. Enzyme-constrained models naturally capture these behaviors as emergent properties of optimal proteome allocation under high substrate conditions [12].

Resource Trade-offs: Enzyme constraints reveal fundamental trade-offs between biomass yield and enzyme usage efficiency. The M. thermophila ecGEM demonstrated how cells balance metabolic efficiency with enzyme investment at varying glucose uptake rates [13].

Metabolic Engineering Targets: Perhaps most significantly, enzyme constraints alter the predicted optimal genetic interventions for strain improvement. The sMOMENT approach applied to E. coli showed that enzyme constraints can significantly change the spectrum of metabolic engineering strategies for different target products compared to traditional stoichiometric models [12].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Model Types

| Performance Metric | Stoichiometric Models | Enzyme-Constrained Models | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Prediction Accuracy | Limited without artificial uptake bounds | Superior prediction across multiple carbon sources without uptake rate fiddling [12] | Consistent with measured growth rates [12] |

| Overflow Metabolism Prediction | Requires artificial flux bounds | Emerges naturally from enzyme allocation optimization [12] | Matches observed aerobic fermentation patterns [12] |

| Carbon Source Hierarchy | Limited predictive capability | Accurate prediction of substrate preference patterns [13] | Aligns with experimental utilization sequences [13] |

| Metabolic Engineering Target Identification | Based solely on flux redistribution | Considers enzyme cost and catalytic efficiency trade-offs [13] [12] | Reveals new, physiologically relevant targets [13] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Constructing an Enzyme-Constrained Metabolic Model

The ECMpy workflow provides an automated methodology for constructing enzyme-constrained models, as demonstrated for M. thermophila [13]:

Stoichiometric Model Refinement:

- Update biomass composition based on experimental measurements of RNA, DNA, protein, and amino acid content

- Correct Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules using genomic annotations and experimental data

- Consolidate redundant metabolites and standardize identifiers

kcat Data Collection:

- Retrieve organism-specific

kcatvalues from databases (BRENDA, SABIO-RK) - Supplement with machine learning-predicted

kcatvalues using tools like TurNuP, DLKcat, or AutoPACMEN - Map

kcatvalues to corresponding reactions in the metabolic model

- Retrieve organism-specific

Model Integration:

- Incorporate enzyme constraints using the ECMpy framework

- Add enzyme usage reactions to the stoichiometric matrix

- Set the total enzyme pool constraint based on experimental proteomic data

Model Validation and Calibration:

- Compare predicted vs. experimental growth rates across conditions

- Validate substrate uptake and product secretion patterns

- Adjust enzyme pool size if necessary to improve predictions

Protocol: Evaluating Model Performance

Comprehensive evaluation follows a standardized approach [8] [13]:

Quantitative Metric Calculation:

- Calculate prediction accuracy:

(TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) - Determine precision:

TP / (TP + FP) - Assess error magnitude for continuous variables (e.g., growth rates)

- Calculate prediction accuracy:

Phenomenological Validation:

- Test prediction of diauxic growth shifts

- Evaluate overflow metabolism under high substrate conditions

- Assess metabolic engineering strategy predictions against experimental results

Solution Space Analysis:

- Compare flux variability ranges between constrained and unconstrained models

- Analyze correlation between predicted and measured fluxes via 13C-flux analysis

Visualization: Conceptual Framework of Enzyme Constraints

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships and constraints that govern enzyme-constrained metabolic models:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Enzyme-Constrained Modelling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| kcat Prediction Tools | TurNuP [13], DLKcat [13], RealKcat [14] | Machine learning approaches for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters from sequence and structural features |

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA [12], SABIO-RK [12], KinHub-27k [14] | Curated repositories of experimental enzyme kinetic parameters for model parameterization |

| Model Construction Frameworks | ECMpy [13], AutoPACMEN [12], GECKO [12] | Automated workflows for integrating enzyme constraints into stoichiometric models |

| Stoichiometric Model Databases | BiGG [13], ModelSEED | Curated genome-scale metabolic models serving as scaffolds for enzyme constraint integration |

| Validation Data Types | Proteomics data, 13C-flux analysis, Growth phenotyping | Experimental datasets for parameterizing and validating enzyme-constrained model predictions |

The integration of kcat and enzyme mass constraints represents a fundamental advancement in metabolic modelling methodology. By bridging the gap between stoichiometric possibilities and physiological realities, these constraints yield more accurate predictions of cellular behavior across diverse conditions. The performance data clearly demonstrates that enzyme-constrained models outperform traditional stoichiometric approaches in both quantitative accuracy and qualitative prediction of complex metabolic phenomena.

For researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development, enzyme-constrained models offer superior guidance for identifying strategic intervention points. They naturally capture the proteomic costs of metabolic engineering strategies, revealing trade-offs that are invisible to traditional stoichiometric analysis. As kinetic parameter databases expand and machine learning prediction tools improve, enzyme-constrained models are poised to become the standard for in silico metabolic design, enabling more efficient development of industrial bioprocesses and therapeutic interventions.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and the Solution Space

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone mathematical approach in constraint-based modeling of cellular metabolism, used to compute the flow of metabolites through biochemical networks [15]. By leveraging stoichiometric coefficients from genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), FBA identifies an optimal flux distribution that maximizes a biological objective—such as biomass production or metabolite yield—within a constrained solution space [16] [15]. This solution space encompasses all possible metabolic flux distributions that satisfy physical and biochemical constraints, including stoichiometry, reaction reversibility, and nutrient uptake rates [17].

A fundamental challenge in FBA is that the predicted optimal flux is rarely unique. The solution space is often large and underdetermined, meaning multiple flux distributions can achieve the same optimal objective value [18]. Consequently, interpreting why a specific solution was selected or assessing the reliability of flux predictions becomes difficult. This is particularly problematic in sophisticated applications like drug development and metabolic engineering, where accurate and interpretable model predictions are crucial. Understanding the full solution space, rather than just a single optimal point, is therefore essential for drawing robust biological conclusions [18].

Comparative Analysis of Solution Space Investigation Methods

Several computational methodologies have been developed to characterize the FBA solution space, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and suitability for different research scenarios. The table below provides a structured comparison of the key methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Investigating the FBA Solution Space

| Method | Core Approach | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) [18] | Determines the min/max range of each reaction flux while maintaining optimal objective value. | Computationally efficient; identifies flexible and rigid reactions. | Provides only per-reaction ranges, not feasible flux combinations; high-dimensional solution space occupies a negligible fraction of the FVA bounding box [17]. | Identifying essential reactions; assessing network flexibility [18]. |

| Solution Space Kernel (SSK) [17] [19] | Extracts a bounded, low-dimensional polytope (the kernel) and a set of ray vectors representing the unbounded aspects of the solution space. | Provides an amenable geometric description of the solution space; intermediate complexity between FBA and elementary modes; specifically handles unbounded fluxes [17]. | Computational complexity can be high for very large models. | Bioengineering strategy evaluation; understanding the physically meaningful flux range [17]. |

| CoPE-FBA [18] | Decomposes alternative optimal flux distributions into topological features: vertices, rays, and linealities. | Characterizes the solution space in terms of a few salient subnetworks or modules. | Can be computationally expensive. | Identifying correlated reaction sets; modular analysis of metabolic networks [18]. |

| NEXT-FBA [20] | A hybrid approach using pre-trained artificial neural networks (ANNs) to derive intracellular flux constraints from exometabolomic data. | Improves prediction accuracy by integrating omics data; minimal input data requirements for pre-trained models. | Requires initial training data (e.g., 13C fluxomics and exometabolomics). | Bioprocess optimization; refining flux predictions for metabolic engineering [20]. |

| Random Perturbation & Sampling [18] | Fixes variable fluxes to random values within their FVA range and recalculates FBA, generating a multitude of optimal distributions. | Computationally cheaper than exhaustive sampling; provides a whole-system overview of sensitivity. | Not an exhaustive exploration of the solution space; results can vary between runs. | Analyzing robustness of FBA solutions; studying phenotypic variability at metabolic branch points [18]. |

| TIObjFind [21] | Integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to infer data-driven objective functions using Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). | Aligns model predictions with experimental flux data; enhances interpretability of complex networks. | Risk of overfitting to specific experimental conditions. | Inferring context-specific metabolic objectives; analyzing metabolic shifts [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Protocol for Solution Space Kernel (SSK) Analysis

The SSK approach aims to reduce the complex solution space into a manageable geometric object. The following protocol is implemented in the publicly available SSKernel software package [17] [19].

- Input Preparation: Provide a stoichiometric model (

N), a defined objective function (e.g., biomass), and constraints on reaction rates (vi ≤ Ci). - Identification of Fixed Fluxes: The algorithm separates all reaction fluxes that remain fixed over the entire solution space when the objective is optimized [17].

- Ray Vector Calculation: Identify directions in the flux space for which the solution space is unbounded and find the corresponding ray vectors that encapsulate these unbounded aspects [17].

- Kernel Construction:

- Identify the bounded faces of the solution space polyhedron, known as Feasible, Bounded Faces (FBFs).

- Introduce additional "capping constraints" that bound the ray vectors without truncating the bounded faces. This creates the bounded SSK polytope [17].

- Kernel Delineation: Delineate the extent and shape of the SSK by finding a set of mutually orthogonal, maximal chords that span it.

- Output Generation: The output includes the bounded kernel, a set of ray vectors, and a "peripheral point polytope" (PPP) that covers the central ~80% of the kernel, providing a simplified set of vertices for analysis [17].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for SSK Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Model (N) | Defines the metabolic network structure and mass-balance constraints. |

| SSKernel Software | The primary computational tool for performing all stages of the kernel calculation [17]. |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver | Used internally by SSKernel to solve optimization problems at various stages, such as identifying FBFs. |

| Objective Function | Defines the cellular goal (e.g., biomass) used to reduce the solution space to the optimal surface. |

Protocol for the NEXT-FBA Workflow

NEXT-FBA is a hybrid methodology that improves the accuracy of intracellular flux predictions by integrating extracellular metabolomic data.

- Data Collection:

- Gather training data comprising paired sets of exometabolomic profiles (extracellular metabolite levels) and intracellular flux distributions, the latter typically measured via 13C-labeling experiments, for example in CHO cells [20].

- Neural Network Training:

- Train an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to learn the underlying relationships between the exometabolomic data (input) and the intracellular fluxomic data (output) [20].

- Constraint Derivation:

- Use the trained ANN, in conjunction with new exometabolomic data, to predict biologically relevant upper and lower bounds for intracellular reaction fluxes [20].

- Constrained FBA:

- Perform a standard Flux Balance Analysis using the genome-scale model, but incorporate the neural network-derived flux constraints to significantly narrow the solution space.

- Validation:

- Validate the predicted intracellular flux distributions against experimental 13C fluxomic data to demonstrate improved alignment compared to existing methods [20].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for NEXT-FBA

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Exometabolomic Data | Serves as the input for the trained neural network to predict intracellular flux constraints [20]. |

| 13C-Labeling Fluxomic Data | Provides the "ground truth" intracellular flux data for training the neural network and validating predictions [20]. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | The core computational model that learns the exometabolome-fluxome relationship. |

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | The metabolic network used for the final constrained FBA simulation. |

Integration with Enzyme-Constrained Modeling

A primary method for refining the FBA solution space involves incorporating enzyme constraints. Traditional FBA, which relies solely on stoichiometry, can predict unrealistically high fluxes and has a large solution space [15]. Enzyme-constrained models (ecModels) address this by capping reaction fluxes based on enzyme availability and catalytic efficiency (kcat values), introducing tighter thermodynamic and physio-logical constraints [15].

Workflows like ECMpy facilitate this integration by adding an overall total enzyme constraint without altering the fundamental structure of the GEM, avoiding the complexity and pseudo-reactions introduced by other methods like GECKO [15]. The practical implementation involves:

- Splitting reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions to assign

kcatvalues. - Splitting reactions with multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions.

- Obtaining enzyme molecular weights, abundance data (e.g., from PAXdb), and

kcatvalues (e.g., from BRENDA). - Setting a cellular protein mass fraction [15].

This approach directly informs the solution space by replacing ad-hoc flux bounds with mechanistic constraints, leading to more accurate and biologically plausible flux predictions. The diagram below illustrates the logical relationship between different model constraints and the resulting solution space.

The choice of a solution space analysis method depends on the specific research goal. For a rapid assessment of flux flexibility, FVA remains a standard first step. For a more comprehensive geometric understanding of feasible flux states, particularly in the context of bioengineering, the SSK approach is powerful. When high-quality omics data are available, hybrid methods like NEXT-FBA can leverage this information to generate the most accurate and biologically relevant intracellular flux predictions. Ultimately, moving beyond a single FBA solution to characterize the entire space of possibilities is critical for generating robust, testable hypotheses in metabolic research and biotechnological application.

Building and Applying Enzyme-Constrained Models: Methodologies and Tools

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become established tools for systematic analysis of metabolism across a wide variety of organisms, primarily using flux balance analysis (FBA) to predict metabolic fluxes under the assumption of steady-state metabolism and optimality principles [22]. However, traditional stoichiometric models often fail to accurately predict suboptimal metabolic behaviors such as overflow metabolism, where microorganisms incompletely oxidize substrates to fermentation byproducts even in the presence of oxygen [6]. This limitation arises because classical FBA lacks constraints representing fundamental cellular limitations, including the finite capacity of the cellular machinery to express metabolic enzymes [6] [23].

Enzyme-constrained GEMs (ecGEMs) address this gap by incorporating enzymatic limitations into metabolic networks, leading to more accurate phenotypic predictions [23] [22]. These models explicitly account for the thermodynamic and resource allocation constraints imposed by the proteome, providing a more physiologically realistic representation of cellular metabolism [8]. The enhancement of GEMs with enzyme constraints has successfully predicted overflow metabolism, explained proteome allocation patterns, and guided metabolic engineering strategies across multiple microorganisms [6] [23] [22]. This guide compares the leading workflows for constructing enzyme-constrained models, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for selecting and implementing these advanced modeling approaches.

Comparative Analysis of Reconstruction Workflows

Several computational workflows have been developed to convert standard GEMs into enzyme-constrained versions. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of three prominent approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Enzyme-Constrained Model Reconstruction Workflows

| Workflow | Core Approach | Key Features | Implementation | Representative Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO | Enhances GEM with enzymatic constraints using kinetic and omics data | Accounts for isoenzymes, enzyme complexes, and promiscuous enzymes; Direct proteomics integration; Automated parameter retrieval from BRENDA | MATLAB, COBRA Toolbox | ecYeastGEM (S. cerevisiae), ecE. coli, ecHuman [22] |

| ECMpy | Simplified workflow with direct enzyme amount constraints | Direct total enzyme constraint; Protein subunit composition consideration; Automated kinetic parameter calibration | Python | eciML1515 (E. coli) [6] |

| AutoPACMEN | Automatic construction inspired by MOMENT and GECKO | Minimal model expansion with one pseudo-reaction and metabolite; Simplified constraint structure | Not specified | B. subtilis, S. coelicolor [6] |

Core Methodological Principles

Despite implementation differences, these workflows share fundamental methodological principles for incorporating enzyme constraints. The central mathematical formulation introduces an enzymatic constraint to the traditional stoichiometric constraints of FBA, typically expressed as:

[ \sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{vi \cdot MWi}{\sigmai \cdot kcat_i} \leq ptot \cdot f ]

Where (vi) represents the flux through reaction (i), (MWi) is the molecular weight of the enzyme, (kcati) is the turnover number, (\sigmai) is the enzyme saturation coefficient, (ptot) is the total protein fraction, and (f) is the mass fraction of enzymes in the proteome [6]. This constraint effectively limits the total flux capacity based on the cell's finite capacity to produce and maintain enzymatic proteins.

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow common to most enzyme-constrained model reconstruction approaches:

Generalized ecGEM Reconstruction Workflow

Technical Implementation Comparison

Workflow-Specific Methodologies

Each major workflow implements the core enzyme constraint principle with distinct technical approaches:

GECKO (Genome-scale model to account for enzyme constraints, using Kinetics and Omics) employs a comprehensive expansion of the metabolic model, where each metabolic reaction is associated with a pseudo-metabolite representing the enzyme, and hundreds of exchange reactions for enzymes are added to the model [6] [22]. This detailed representation accounts for various enzyme-reaction relationships, including isoenzymes, enzyme complexes, and promiscuous enzymes. GECKO 2.0 incorporates a hierarchical procedure for retrieving kinetic parameters from the BRENDA database, significantly improving parameter coverage [22].

ECMpy implements a simplified approach that directly adds total enzyme amount constraints without modifying existing metabolic reactions or adding new reactions [6]. For reactions catalyzed by enzyme complexes, it uses the minimum kcat/MW value among the proteins in the complex. ECMpy features an automated calibration process for enzyme kinetic parameters based on principles of enzyme usage consistency with experimental flux data [6].

AutoPACMEN strikes a middle ground by introducing only one pseudo-reaction and pseudo-metabolite to represent enzyme constraints, minimizing model complexity while maintaining physiological relevance [6]. This approach reduces computational overhead while still capturing the essential proteomic limitations on metabolic flux.

Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Handling

A critical challenge in ecGEM construction is obtaining reliable enzyme kinetic parameters. The workflows differ significantly in their parameterization approaches:

Table 2: Kinetic Parameter Handling Across Workflows

| Workflow | Primary Data Sources | Parameter Coverage Strategy | Organism-Specificity Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Hierarchical matching: organism-specific → phylogenetically close → general | Filters by phylogenetic similarity using KEGG phylogenetic tree [22] |

| ECMpy | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Automated calibration using enzyme usage and 13C flux consistency principles | Calibration against experimental growth data [6] |

| AutoPACMEN | Not specified | Not explicitly described | Not explicitly described |

GECKO 2.0 addresses the uneven distribution of kinetic data across organisms through an enhanced matching algorithm. When organism-specific parameters are unavailable, it employs a phylogenetic similarity approach, prioritizing data from closely related species [22]. This is particularly important given that kinetic parameters can vary by several orders of magnitude even for enzymes with similar biochemical mechanisms [22].

Experimental Validation and Performance Assessment

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rigorous validation is essential for establishing the predictive capabilities of enzyme-constrained models. The following performance comparisons demonstrate the advantages of ecGEMs over traditional stoichiometric models:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Enzyme-Constrained vs. Stoichiometric Models

| Validation Metric | Traditional GEM | Enzyme-Constrained GEM | Experimental Data | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth rate prediction error (24 carbon sources) | Higher error rates | Significant improvement (eciML1515) [6] | Reference values | E. coli |

| Glucose uptake rate (mmol/gCDW/h) | 23 (predicted) | 29 (predicted and confirmed) [23] | 29 (measured) | S. cerevisiae |

| Overflow metabolism prediction | Fails to predict | Accurate prediction of acetate secretion [6] | Observed experimentally | E. coli |

| ATP yield enzyme cost | Not accounted for | Predicts tradeoff between yield and enzyme usage [6] | Consistent with physiology | E. coli |

Case Study: Redox Engineering in E. coli

The ECMpy workflow was used to construct eciML1515, an enzyme-constrained model of E. coli. This model successfully predicted overflow metabolism and revealed that redox balance, rather than optimal ATP yield alone, explains the differences in overflow metabolism between E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [6]. The model accurately predicted growth rates on 24 single-carbon sources, significantly outperforming previous enzyme-constrained models of E. coli [6].

Case Study: Pathway Engineering in S. cerevisiae

A notable validation of ecGEM predictive capability came from engineering S. cerevisiae to replace alcoholic fermentation with equimolar co-production of 2,3-butanediol and glycerol [23]. The enzyme-constrained model predicted that this pathway swap, which reduces ATP yield from 2 ATP/glucose to just 2/3 ATP/glucose, would necessitate a substantial increase in glucose uptake rate to sustain growth. The model predicted growth at 0.175 hâ»Â¹ with increased glucose consumption, closely matching the experimentally observed growth of 0.15 hâ»Â¹ with one of the highest glucose consumption rates reported for S. cerevisiae (29 mmol/gCDW/h) [23]. Proteomic analysis confirmed the predicted reallocation of enzyme resources from ribosomes to glycolysis [23].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of enzyme-constrained modeling requires specific computational tools and data resources:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ecGEM Construction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in Workflow | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Source of enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) | Publicly available [6] [22] |

| Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox, COBRApy, RAVEN Toolbox | Constraint-based simulation and model reconstruction | Open-source [6] [24] [22] |

| Genome Annotation | KEGG, MetaCyc, ModelSEED | Draft reconstruction of metabolic networks | Publicly available [25] [24] |

| Proteomics Data | Species-specific proteomics measurements | Parameterization and validation of enzyme constraints | Experimental or public databases [23] [22] |

| Reconstruction Tools | CarveMe, gapseq, KBase | Automated draft GEM generation | Open-source [25] |

Advanced Applications and Integration

Multi-Constraint Integration

Recent advances have combined enzyme constraints with other physiological limitations. The ET-OptME framework integrates both enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic feasibility constraints into GEMs, delivering more physiologically realistic intervention strategies [8]. Quantitative evaluation in Corynebacterium glutamicum models revealed at least 70% increase in accuracy and 292% increase in minimal precision compared with enzyme-constrained algorithms alone [8].

Community-Scale Modeling

Enzyme-constrained approaches are also being extended to microbial communities. Comparative analysis of community metabolic models revealed that consensus approaches combining reconstructions from multiple tools (CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase) encompass larger numbers of reactions and metabolites while reducing dead-end metabolites [25]. This suggests that consensus modeling may improve the functional prediction of metabolic interactions in complex microbial systems.

The following diagram illustrates the expanding capabilities of enzyme-constrained models beyond traditional applications:

Expanding Applications of Enzyme-Constrained Models

The development of enzyme-constrained genome-scale models represents a significant advancement in metabolic modeling capability. Workflows including GECKO, ECMpy, and AutoPACMEN provide distinct approaches with complementary strengths: GECKO offers comprehensive enzyme-reaction mapping, ECMpy provides simplified implementation, and AutoPACMEN balances completeness with computational efficiency.

Experimental validations consistently demonstrate that enzyme-constrained models outperform traditional stoichiometric models in predicting physiological behaviors, particularly in scenarios involving proteome allocation tradeoffs, overflow metabolism, and metabolic pathway engineering. The integration of enzyme constraints with other physiological limitations, such as thermodynamic feasibility and microbial community interactions, represents the frontier of constraint-based modeling research.

As kinetic databases expand and proteomic measurement technologies advance, enzyme-constrained models will increasingly become standard tools for metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and fundamental biological research. The ongoing development of automated, version-controlled ecModel pipelines promises to make these sophisticated modeling approaches accessible to a broader research community [22].

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become established tools for systematically analyzing cellular metabolism across a wide variety of organisms, with applications spanning from model-driven development of efficient cell factories to understanding mechanisms underlying complex human diseases [26] [22]. The most common simulation technique for these models is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which predicts metabolic phenotypes based on reaction stoichiometries and optimality principles [26]. However, traditional stoichiometric models face a significant limitation: they do not explicitly account for the enzyme capacity and proteomic constraints that fundamentally shape cellular metabolism in vivo [26]. This omission often results in overly optimistic predictions of growth and production yields, as these models assume metabolic fluxes can increase linearly with substrate uptake without considering the finite protein synthesis capacity of cells [26] [6].

To address these limitations, several enzyme-constrained modeling frameworks have been developed, with GECKO (Genome-scale model with Enzyme Constraints using Kinetics and Omics), MOMENT (Metabolic Modeling with Enzyme Kinetics), and ECMpy (Enzyme-Constrained Models in Python) emerging as prominent approaches [26] [22] [6]. These frameworks enhance standard GEMs by incorporating enzymatic constraints based on kinetic parameters and proteomic limitations, enabling more accurate predictions of metabolic behaviors including overflow metabolism and substrate utilization patterns [6] [27]. This comparison guide examines the practical implementation, performance characteristics, and experimental applications of these three key frameworks within the broader context of enzyme-constrained versus stoichiometric models performance research.

GECKO (Genome-scale model with Enzyme Constraints using Kinetics and Omics)

The GECKO framework, originally developed in 2017 and upgraded to version 2.0 in 2022, provides a comprehensive approach for enhancing GEMs with enzymatic constraints using kinetic and proteomic data [22]. GECKO extends classical FBA by incorporating a detailed description of enzyme demands for metabolic reactions, accounting for all types of enzyme-reaction relations including isoenzymes, promiscuous enzymes, and enzymatic complexes [22]. The framework enables direct integration of proteomics abundance data as constraints for individual protein demands, represented as enzyme usage pseudo-reactions, while unmeasured enzymes are constrained by a pool of remaining protein mass [22].

GECKO's implementation involves expanding the stoichiometric matrix to include protein "metabolites" where each enzyme participates in its respective reaction as a pseudometabolite with the stoichiometric coefficient 1/kcat, where kcat is the turnover number of the enzyme [4]. Proteins are supplied into the network through protein pseudoexchanges, with the upper bounds of these exchanges representing protein concentrations [4]. GECKO 2.0 introduced a modified set of hierarchical kcat matching criteria to address how kcat numbers are assigned, significantly improving parameter coverage even for less-studied organisms [22].

MOMENT (Metabolic Modeling with Enzyme Kinetics)

The MOMENT framework incorporates enzyme constraints by considering known enzyme kinetic parameters and physical proteome limitations [6] [27]. This approach introduces both crowding coefficients and cell volume constraints to limit the space occupied by enzymes, successfully simulating substrate hierarchy utilization in E. coli [6]. MOMENT accounts for the enzyme capacity and simple kinetic limitations at genome scale, with mathematical formulations that can range from linear programming (LP) problems containing only continuous variables to more computationally demanding mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problems [26].

A variation called "short MOMENT" has also been developed, providing a simplified approach to enzyme constraint integration [27]. The MOMENT framework generally requires manual collection of enzyme kinetic parameter information, which can be challenging for less-studied organisms [28].

ECMpy (Enzyme-Constrained Models in Python)

ECMpy represents a simplified Python-based workflow for constructing enzyme-constrained metabolic models [28] [6]. Unlike GECKO, which modifies every metabolic reaction by adding pseudo-metabolites and exchange reactions, ECMpy directly adds a total enzyme amount constraint to existing GEMs without extensively modifying the model structure [6]. This approach considers protein subunit composition in reactions and includes an automated calibration process for enzyme kinetic parameters [6].

The core enzymatic constraint in ECMpy is formulated as:

[ \sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{vi \cdot MWi}{\sigmai \cdot kcat_i} \leq ptot \cdot f ]

Where (vi) is the flux through reaction i, (MWi) is the molecular weight of the enzyme catalyzing reaction i, (\sigmai) is the enzyme saturation coefficient, (kcati) is the turnover number, (ptot) is the total protein fraction, and (f) is the mass fraction of enzymes calculated based on proteomic abundances [6]. ECMpy 2.0 has broadened its scope to automatically generate enzyme-constrained GEMs for a wider array of organisms and incorporates machine learning for predicting kinetic parameters to enhance parameter coverage [28].

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Enzyme-Constrained Modeling Frameworks

| Feature | GECKO | MOMENT | ECMpy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Expands stoichiometric matrix with enzyme pseudometabolites | Incorporates crowding coefficients & volume constraints | Adds total enzyme constraint without modifying reaction stoichiometries |

| Kinetic Parameter Source | Hierarchical matching from BRENDA | Manual collection from literature & databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, plus ML-predicted values |

| Proteomics Integration | Direct constraint of individual enzymes with measured abundances | Limited incorporation of proteomic data | Utilized for calculating enzyme mass fraction |

| Software Base | MATLAB/Python hybrid | Not specified | Python |

| Model Size Impact | Significantly increases model size | Moderate increase | Minimal increase |

Framework Comparison: Technical Specifications and Performance

Mathematical Formulations and Computational Requirements

The mathematical foundation for enzyme-constrained models builds upon traditional FBA, which solves a linear programming problem to optimize an objective function (typically biomass production) subject to stoichiometric constraints and reaction bounds [26]:

[ \begin{align} &\text{maximize } Z = c^T v \ &\text{subject to } Sv = 0 \ &\text{and } lbj \leq vj \leq ub_j \end{align} ]

Where (Z) is the objective function, (c) is the coefficient vector, (v) is the vector of reaction fluxes, (S) is the stoichiometric matrix, and (lbj) and (ubj) are lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux [26].

Enzyme-constrained formulations extend this base problem by adding proteomic constraints. GECKO, for instance, expands the stoichiometric matrix (S) to include protein metabolites and adds protein exchange reactions [4]. The ECMpy approach incorporates an additional enzymatic constraint as shown in Section 2.3 without modifying the original stoichiometric matrix [6]. These differences in mathematical implementation lead to varying computational requirements, with GECKO typically producing larger models due to the addition of pseudoreactions and metabolites, while ECMpy maintains a similar problem size to the original GEM [15] [6].

Predictive Performance Across Biological Contexts

Multiple studies have evaluated the predictive capabilities of enzyme-constrained models compared to traditional stoichiometric models. The enzyme-constrained model for E. coli constructed with ECMpy (eciML1515) demonstrated significantly improved prediction of growth rates across 24 single-carbon sources compared to the base model iML1515 [6]. The enzyme-constrained model also successfully simulated overflow metabolism, a phenomenon where microorganisms incompletely oxidize substrates to fermentation products even under aerobic conditions, which traditional FBA fails to predict accurately [6].

Similarly, an enzyme-constrained model for Clostridium ljungdahlii developed using the AutoPACMEN approach (based on similar principles as MOMENT) showed improved predictive ability for growth rate and product profiles compared to the original metabolic model iHN637 [27]. The model was successfully employed for in silico metabolic engineering using the OptKnock framework to identify gene knockouts for enhancing production of valuable metabolites [27].

GECKO-based models have demonstrated particular success in predicting the Crabtree effect in yeast and explaining microbial growth on diverse environments and genetic backgrounds [22]. The ecYeast7 model provided a framework for predicting protein allocation profiles and studying proteomics data in a metabolic context [22].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Enzyme-Constrained Models

| Performance Metric | Traditional GEM | GECKO-enhanced | MOMENT-enhanced | ECMpy-enhanced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate Prediction | Overestimated at high uptake rates | Improved agreement with experimental data | Better capture of metabolic switches | Significant improvement across multiple carbon sources |

| Overflow Metabolism | Fails to predict | Accurately predicts Crabtree effect in yeast | Explains substrate hierarchy | Reveals redox balance as key driver in E. coli |

| Enzyme Usage Efficiency | Not accounted for | Enables proteome allocation analysis | Accounts for molecular crowding | Quantifies trade-off between yield and efficiency |

| Genetic Perturbation Predictions | Often unrealistic flux distributions | Improved prediction of mutant phenotypes | Limited published data | Reliable guidance for metabolic engineering |

Parameter Requirements and Coverage

A critical challenge in enzyme-constrained modeling is obtaining sufficient coverage of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat values). The BRENDA database contains kinetic parameters for enzymes, but the distribution is highly skewed toward well-studied model organisms [22]. Analysis has shown that while entries for H. sapiens, E. coli, R. norvegicus, and S. cerevisiae account for 24.02% of the total database, most organisms have very few kinetic parameters available, with a median of just 2 entries per organism [22].

Each framework addresses this challenge differently. GECKO implements a hierarchical kcat matching criteria that first searches for organism-specific values, then values from closely related organisms, and finally non-specific values [22]. ECMpy employs machine learning to predict kcat values, significantly enhancing parameter coverage [28]. MOMENT typically relies on manual curation and literature mining for kinetic parameters [6].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol: Constructing an Enzyme-Constrained Model with ECMpy

The ECMpy workflow for constructing an enzyme-constrained model involves several methodical steps [6]:

Model Preparation: Begin with a functional genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli). Identify and correct any errors in gene-protein-reaction (GPR) relationships, reaction directions, and metabolite annotations using databases like EcoCyc.

Reaction Processing: Split all reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions to assign separate kcat values. Similarly, split reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions, as they may have different associated kcat values.

Parameter Acquisition:

- Calculate enzyme molecular weights using protein subunit composition from relevant databases

- Obtain kcat values from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases

- For enzymes lacking experimental kcat values, use machine learning prediction tools like UniKP (integrated in ECMpy 2.0)

- Gather protein abundance data from sources like PAXdb for calculating enzyme mass fraction

Parameter Calibration: Implement a two-principle calibration process:

- Identify reactions where enzyme usage exceeds 1% of total enzyme content for parameter correction

- Identify reactions where kcat multiplied by 10% of total enzyme amount is less than the flux determined by 13C experiments

- Adjust kcat values within physiologically reasonable ranges to improve agreement with experimental data

Model Simulation: Incorporate enzyme constraints into the model and perform FBA using COBRApy functions. For growth predictions, set substrate uptake rates to experimentally relevant values (e.g., 10 mmol/gDW/h for carbon sources) and compare predicted vs. experimental growth rates.

Diagram 1: ECMpy Model Construction Workflow

Protocol: Metabolic Engineering with Enzyme-Constrained Models

Enzyme-constrained models can be powerful tools for identifying metabolic engineering targets. The following protocol outlines their application using the OptKnock framework [27]:

Model Validation: Before performing in silico metabolic engineering, validate the enzyme-constrained model by comparing its predictions of growth rates and metabolic secretion profiles with experimental data under relevant conditions.

Condition Specification: Define the specific growth conditions for the metabolic engineering design, including:

- Substrate uptake rates (e.g., syngas composition for acetogens)

- Nutrient availability

- Environmental factors (pH, temperature if modeled)

OptKnock Implementation: Apply the OptKnock algorithm to identify gene knockout strategies that couple growth with production of target metabolites:

- Set biomass production as the objective for inner optimization

- Set product secretion rate as the objective for outer optimization

- Constrain the maximum number of reaction knockouts based on practical implementation considerations

Strategy Evaluation: Analyze the proposed knockout strategies for:

- Physiological feasibility

- Redundancy across different target products

- Robustness to minor changes in growth conditions

- Compatibility with known regulatory constraints

Experimental Validation: Implement promising knockout strategies in the laboratory and compare results with model predictions to iteratively refine the model.

Case Study: E. coli Enzyme-Constrained Model for Overflow Metabolism