Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling for Host Selection: A Systems Biology Framework for Therapeutic Development

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a powerful computational framework for predicting host-microbe metabolic interactions, offering transformative potential for therapeutic development.

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling for Host Selection: A Systems Biology Framework for Therapeutic Development

Abstract

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a powerful computational framework for predicting host-microbe metabolic interactions, offering transformative potential for therapeutic development. This article explores how GEMs enable systematic selection of microbial hosts and consortia based on their metabolic capabilities and compatibility with human physiology. We cover foundational principles of constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA), methodological approaches for modeling host-microbe interactions, strategies for optimizing model accuracy and performance, and validation techniques for ensuring biological relevance. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis of current methodologies and applications demonstrates how GEMs facilitate rational design of live biotherapeutic products, identification of drug targets, and personalized medicine approaches through in silico host selection.

Understanding Genome-Scale Metabolic Models: Core Principles and Biological Significance in Host-Microbe Interactions

What Are Genome-Scale Metabolic Models? Mathematical Foundations and Stoichiometric Principles

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of the entire metabolic network of an organism, based on its genomic annotation [1] [2]. These models formally describe the biochemical conversions that an organism can perform, connecting an organism's genotype to its metabolic phenotype [1]. By contextualizing different types of 'Big Data' such as genomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics, GEMs provide a mathematical framework for simulating metabolism in archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotic organisms [1]. The first GEM was reconstructed for Haemophilus influenzae in 1999, and since then, the field has expanded dramatically with thousands of models now available across the tree of life [2].

GEMs have become indispensable tools in systems biology and metabolic engineering with applications ranging from predicting metabolic phenotypes and elucidating metabolic pathways to identifying drug targets and understanding host-associated diseases [1]. In the specific context of host selection research, particularly for the development of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), GEMs provide a systems-level approach for characterizing candidate strains and their metabolic interactions with host cells and adjacent microbiome members [3]. This enables researchers to evaluate strain functionality, host interactions, and microbiome compatibility in silico before proceeding to costly experimental validation [3].

Mathematical Foundations of Stoichiometric Modeling

Core Stoichiometric Principles

At the heart of every GEM lies the stoichiometric matrix, denoted as S [4] [5]. This mathematical structure captures the underlying biochemistry of the metabolic network. The stoichiometric matrix is an m×r matrix where m represents the number of metabolites and r represents the number of reactions in the network [4]. Each element sᵢⱼ of the matrix represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [4].

The fundamental equation governing metabolic networks at steady state is:

where v is the vector of reaction fluxes (reaction rates) [4]. This equation formalizes the mass-balance assumption that for each internal metabolite in the system, the rate of production equals the rate of consumption [4] [5]. The steady-state assumption transforms the potentially complex enzyme kinetics into a linear problem that can be analyzed using linear programming techniques [5].

Chemical Moisty Conservation

An important concept in stoichiometric modeling is chemical moiety conservation, which arises when metabolites are recycled in metabolic networks [4]. Examples include adenosine phosphate compounds (ATP, ADP, AMP) and redox cofactors (NADH, NADPH) [4]. These conservation relationships impose linear dependencies between the rows of the stoichiometric matrix and constrain the possible concentration changes of metabolites [4]. The moiety conservation relationships can be derived from the left null-space of the stoichiometric matrix and used to decompose the matrix into independent and dependent blocks [4].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components of Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation | Role in Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | m × r matrix with elements sᵢⱼ | Network structure: stoichiometry of metabolite i in reaction j | Defines mass balance constraints: S·v = 0 |

| Flux Vector (v) | r × 1 vector of reaction rates | Metabolic activity: flux through each reaction | Variables to be optimized; represent metabolic phenotype |

| Objective Function | cáµ€v (linear combination) | Cellular goal (e.g., biomass production) | Drives flux distribution toward biological objective |

| Constraints | lb ≤ v ≤ ub | Physiological limitations (enzyme capacity, substrate uptake) | Defines feasible solution space |

| Moiety Conservation | L·x = constant | Conservation of chemical moieties (e.g., ATP-ADP-AMP) | Reduces system dimensionality; adds thermodynamic constraints |

Methodological Framework for GEM Reconstruction and Analysis

GEM Reconstruction Workflow

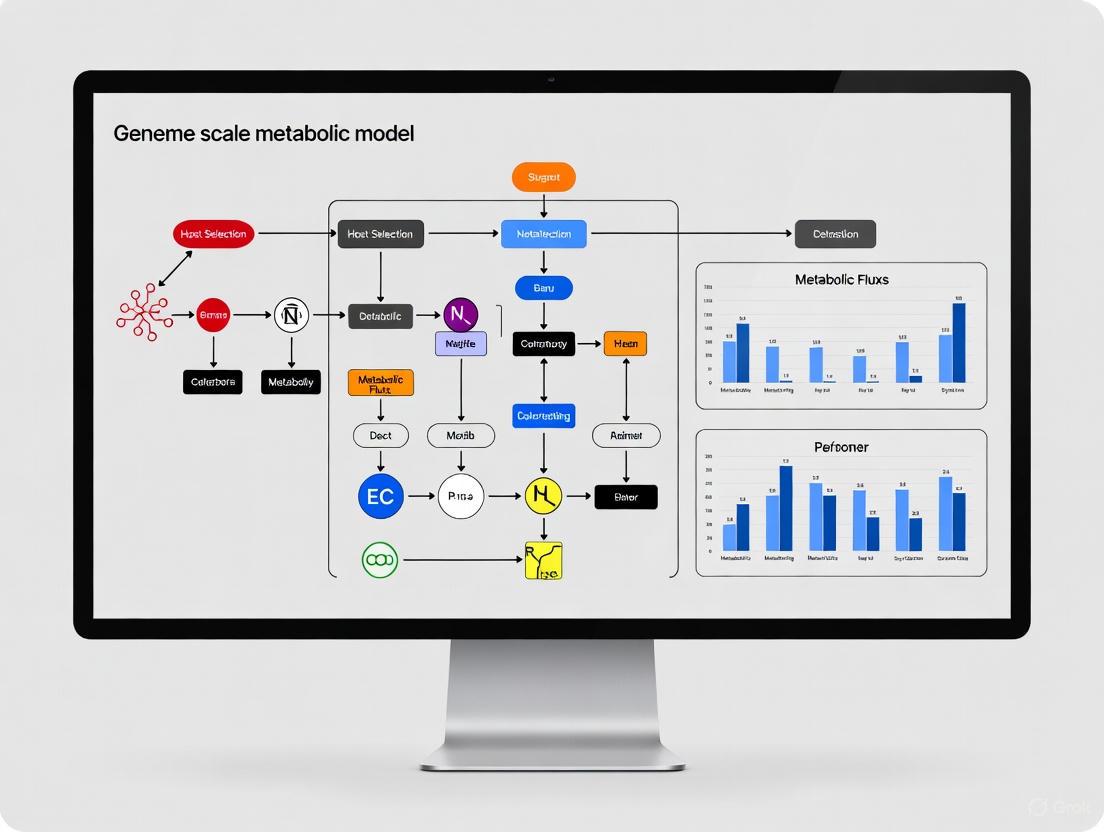

The reconstruction of high-quality GEMs follows a systematic process that integrates genomic, biochemical, and physiological information [6]. The workflow can be conceptually divided into several key stages, as illustrated below:

The process begins with genome annotation, where genes are mapped to metabolic functions using databases such as BiGG, KEGG, and ModelSEED [6]. This step establishes the initial set of metabolic reactions that can be supported by the organism's genome [1] [6]. The draft reconstruction is then refined through network gap-filling, where missing reactions are added to ensure network connectivity and functionality based on physiological evidence [6]. A critical step is the definition of biomass composition, which represents the metabolic requirements for cellular growth and maintenance [4] [6]. The model is subsequently validated using experimental data such as growth phenotypes, gene essentiality, and substrate utilization patterns [6] [2].

For host selection research, the final step involves contextualizing the model using host and microbiome data to enable simulation of host-microbe interactions [3] [5].

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA)

The primary mathematical framework for simulating GEMs is Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) [5]. This approach uses the stoichiometric matrix along with additional physiological constraints to define the feasible solution space of metabolic fluxes [4] [5]. The core methods within the COBRA framework include:

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): FBA is an optimization method that predicts metabolic flux distributions by assuming the cell maximizes or minimizes a specific biological objective function, typically biomass production [1] [5]. The mathematical formulation of FBA is:

Maximize cáµ€v

Subject to: S·v = 0

and lb ≤ v ≤ ub

where c is a vector indicating the objective function, and lb and ub are lower and upper bounds on fluxes, respectively [4] [5].

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): FVA determines the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal or near-optimal objective values [4]. This helps identify alternative optimal flux distributions and assess network flexibility [4].

Dynamic FBA: This extension incorporates dynamic changes in metabolite concentrations and environmental conditions over time, allowing for simulation of batch cultures or changing environments [1] [7].

Experimental Protocols for GEM Validation and Application

Protocol for In Silico Growth Phenotype Prediction

Purpose: To validate GEM predictions against experimental growth data under different nutrient conditions [6] [2].

Methodology:

- Constraint Definition: Define the nutrient availability in the simulation environment by setting bounds on exchange reactions corresponding to the medium composition [6].

- Objective Specification: Set biomass production as the objective function to maximize [5].

- FBA Simulation: Perform flux balance analysis to predict growth rates [5].

- Experimental Comparison: Compare predicted growth capabilities (growth/no-growth) and relative growth rates with experimentally measured values [2].

Interpretation: Models with >80% accuracy in predicting gene essentiality and growth capabilities are generally considered high-quality [2]. For example, the E. coli GEM iML1515 shows 93.4% accuracy for gene essentiality simulation under minimal media with different carbon sources [2].

Protocol for Host-Microbe Interaction Analysis

Purpose: To predict metabolic interactions between microbial strains and host organisms for therapeutic selection [3] [5].

Methodology:

- Model Integration: Combine host and microbial GEMs into a unified modeling framework, creating a compartmentalized system [5].

- Metabolite Exchange Definition: Define the metabolite exchange between host and microbial compartments based on physiological knowledge [3] [5].

- Cross-Feeding Simulation: Implement simulation techniques such as SteadyCom or COMMET to predict stable co-existence and metabolic cross-feeding [3].

- Therapeutic Potential Assessment: Evaluate microbial strains based on production of beneficial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids), consumption of detrimental metabolites, and compatibility with host metabolism [3].

Interpretation: Strains that produce higher levels of therapeutic metabolites, show minimal antagonistic interactions with beneficial resident microbes, and support host metabolic objectives are prioritized for further development [3].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for GEM Reconstruction and Analysis

| Resource Type | Examples | Primary Function | Application in Host Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Databases | BiGG [6], AGORA2 [3] | Curated repository of metabolic models | Access to pre-built models of host-associated microbes |

| Reconstruction Tools | ModelSEED [5], CarveMe [6] [5], RAVEN [5] | Automated generation of draft GEMs from genomic data | Rapid assessment of candidate strain metabolism |

| Simulation Platforms | COBRA Toolbox [8], COBRApy [8] | MATLAB/Python implementations of constraint-based methods | Prediction of strain behavior in host-relevant conditions |

| Community Modeling Resources | metaGEM [9], Microbiome Modeling Toolbox [9] | Tools for multi-species and host-microbe simulations | Evaluation of strain integration into existing communities |

| Standardization Resources | MetaNetX [5] | Namespace reconciliation between models | Enable integration of host and microbial models |

Application in Host Selection Research

Framework for Live Biotherapeutic Product Development

GEMs provide a systematic framework for the selection and design of live biotherapeutic products (LBPs) through a multi-step evaluation process [3]:

- In Silico Screening: Candidate strains are shortlisted from microbial collections (e.g., AGORA2 database containing 7,302 gut microbes) based on qualitative assessment of metabolic capabilities [3].

- Quality Evaluation: Strain-specific traits including metabolic activity, growth potential, and adaptation to gastrointestinal conditions (pH fluctuations, bile salts) are simulated [3].

- Safety Assessment: Potential risks including antibiotic resistance, drug interactions, and production of detrimental metabolites are evaluated [3].

- Efficacy Prediction: Therapeutic potential is assessed through production of beneficial metabolites (e.g., short-chain fatty acids for inflammatory bowel disease) and positive modulation of host metabolism [3].

Table 3: GEM-Based Assessment Criteria for Therapeutic Strain Selection

| Assessment Category | Specific Metrics | Simulation Approach | Therapeutic Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Quality | Growth rate in host-relevant conditions, Nutrient utilization profile | FBA with physiological constraints | Predicts survival and persistence in host environment |

| Metabolic Function | Production potential of therapeutic metabolites (SCFAs, vitamins) | FVA with product secretion maximization | Indicates direct therapeutic mechanism |

| Host Compatibility | Complementarity with host metabolic objectives, Minimal resource competition | Integrated host-microbe FBA | Ensures symbiotic rather than parasitic relationship |

| Microbiome Integration | Positive interactions with resident microbes, Minimal disruption to community | Multi-species community modeling | Predicts successful engraftment and stability |

| Safety Profile | Absence of pathogenicity factors, Detrimental metabolite production | Pathway analysis and secretion profiling | Mitigates potential adverse effects |

Addressing Uncertainty in Model Predictions

A critical consideration in using GEMs for host selection is acknowledging and addressing the multiple sources of uncertainty in model predictions [6]. These include:

- Annotation Uncertainty: Incorrect or incomplete mapping of genes to metabolic functions [6].

- Environment Specification: Imperfect knowledge of the host microenvironment and nutrient availability [6].

- Biomass Formulation: Species-specific variations in biomass composition that affect growth predictions [6].

- Network Gaps: Missing reactions or pathways in the metabolic reconstruction [6].

- Flux Simulation Degeneracy: Multiple flux distributions can achieve the same biological objective [6].

Probabilistic annotation methods and ensemble modeling approaches are emerging as strategies to quantify and manage these uncertainties [6]. For host selection applications, it is recommended to use consensus predictions from multiple model versions and to integrate experimental validation at key decision points [6] [3].

Genome-scale metabolic models provide a powerful mathematical framework for understanding and predicting metabolic behavior across all domains of life. Founded on stoichiometric principles and constraint-based optimization, GEMs enable researchers to move from genomic information to predictive models of metabolic function. The mathematical rigor of these models, combined with their ability to integrate diverse omics data, makes them particularly valuable for host selection research in therapeutic development.

As the field advances, emerging methods in machine learning, improved uncertainty quantification, and enhanced community modeling capabilities promise to further strengthen the application of GEMs in host selection and personalized medicine [1] [6] [3]. For researchers focused on developing live biotherapeutic products, GEMs offer a systematic approach to evaluate strain functionality, safety, and efficacy in silico, potentially accelerating the translation of microbiome research into clinical applications.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are powerful computational frameworks that enable the mathematical simulation of metabolism for archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotic organisms [1]. These models quantitatively define the relationship between genotype and phenotype by integrating various types of Big Data, including genomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics [1]. GEMs represent a comprehensive collection of all known metabolic information of a biological system, structured around several core components: genes, enzymes, reactions, associated gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, and metabolites [1]. This architecture provides a network-based tool that can predict cellular phenotypes from genotypic information, making GEMs invaluable for both basic research and applied biotechnology.

The development and refinement of GEMs have been accelerated by major technological advances that have enabled the generation of biological Big Data in a cost-efficient and high-throughput manner [1]. As our understanding of cellular metabolism has deepened, GEMs have evolved from modeling individual organisms to capturing the complex metabolic interactions in microbial communities and host-microbe systems [10]. This expansion in scope is particularly relevant for host selection research, where understanding the metabolic interdependencies between hosts and their associated microbiomes can inform therapeutic strategies and drug development programs.

Core Architectural Components of GEMs

Fundamental Building Blocks

The architecture of GEMs is built upon several interconnected components that collectively represent the metabolic potential of an organism. Each component plays a distinct role in forming a comprehensive mathematical representation of metabolism.

Table 1: Core Components of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Component | Description | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Genes | DNA sequences encoding metabolic enzymes | Provide genetic basis for metabolic capabilities |

| Proteins/Enzymes | Gene products that catalyze biochemical reactions | Execute catalytic functions in metabolic pathways |

| Reactions | Biochemical transformations between metabolites | Form the edges of the metabolic network |

| Metabolites | Chemical compounds participating in reactions | Serve as substrates and products; nodes in the network |

| GPR Rules | Boolean relationships connecting genes to reactions | Link genomic annotation to metabolic functionality |

Mathematical Representation

At its core, a GEM is represented mathematically as a stoichiometric matrix S, where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent biochemical reactions [5]. The elements Sij of this matrix denote the stoichiometric coefficients of metabolite i in reaction j. This matrix forms the foundation for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods, enabling the simulation of metabolic behavior under various physiological conditions [5].

The metabolic network is subject to mass-balance constraints, requiring that for each internal metabolite, the total production equals total consumption. This is expressed mathematically as S·v = 0, where v is the flux vector representing reaction rates in the network [5]. Additional constraints are applied to define the system's boundaries, including nutrient availability, thermodynamic feasibility, and enzyme capacity constraints.

GEM Reconstruction Workflow

The process of reconstructing a high-quality GEM involves multiple meticulously executed steps that transform genomic information into a predictive metabolic model.

Automated Draft Reconstruction

The reconstruction process begins with an annotated genome, which serves as the foundational blueprint for the metabolic model. Automated reconstruction tools such as ModelSEED [11] [5], CarveMe [11] [5], gapseq [5], and RAVEN [5] generate draft models by mapping annotated genes to known biochemical reactions using template-based approaches. These tools leverage curated databases of metabolic reactions to assign functional capabilities based on genomic evidence, creating an initial metabolic network that represents the organism's potential metabolic functions.

The quality of draft reconstructions varies significantly depending on the completeness of genome annotation and the suitability of the template database. For well-characterized model organisms, automated pipelines can produce reasonably comprehensive drafts, while for non-model organisms with limited annotation, the resulting drafts often contain substantial knowledge gaps that require extensive manual curation.

Manual Curation and Knowledge Integration

Manual curation is the most critical phase in transforming an automated draft into a high-quality, predictive metabolic model. This process involves:

- Literature mining: Systematic review of experimental studies to validate and refine reaction annotations

- Database integration: Incorporation of data from specialized metabolic databases such as BiGG [11] [5] and MetaNetX [5]

- Pathway validation: Ensuring completeness and connectivity of metabolic pathways through gap analysis

- GPR rule refinement: Precisely defining the Boolean relationships between genes and reactions

For host metabolic models, particularly eukaryotic systems, additional complexities arise from compartmentalization of metabolic processes in organelles such as mitochondria, peroxisomes, and endoplasmic reticulum [5]. Multicellular hosts present further challenges due to tissue-specific metabolic specialization, requiring careful consideration of which metabolic functions to include in the model.

Gap-Filling and Network Refinement

A significant challenge in GEM reconstruction is addressing knowledge gaps resulting from incomplete genomic annotation or limited biochemical characterization. Gap-filling methods identify and rectify these deficiencies to create a functional metabolic network.

Table 2: Computational Methods for GEM Refinement and Gap-Filling

| Method | Approach | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CHESHIRE [11] | Deep learning using hypergraph topology | Predicts missing reactions purely from network structure |

| FastGapFill [11] | Flux consistency optimization | Restores network connectivity based on metabolic functionality |

| NHP (Neural Hyperlink Predictor) [11] | Graph neural networks | Predicts hyperlinks in metabolic networks |

| C3MM [11] | Clique closure-based matrix minimization | Identifies missing reactions through matrix completion |

The CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) method represents a recent advancement in gap-filling technology. This deep learning approach predicts missing reactions in GEMs using only metabolic network topology, without requiring experimental phenotypic data as input [11]. CHESHIRE employs a Chebyshev spectral graph convolutional network (CSGCN) to capture metabolite-metabolite interactions and generates probabilistic scores indicating the confidence of reaction existence [11]. This method has demonstrated superior performance in recovering artificially removed reactions across 926 high- and intermediate-quality GEMs compared to other topology-based methods [11].

Simulation Methods and Analytical Approaches

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Flux Balance Analysis is the primary computational method for simulating metabolic behavior using GEMs. FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through the metabolic network under steady-state assumptions, optimizing for a biological objective such as biomass production or ATP synthesis [1] [5].

The mathematical formulation of FBA is: Maximize cᵀv Subject to: S·v = 0 vlb ≤ v ≤ vub

Where c is a vector representing the biological objective function, v is the flux vector, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and vlb and vub are lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes, respectively [5].

FBA predictions have been successfully validated against experimental data for various phenotypes, including growth rates, nutrient uptake, and byproduct secretion [1]. This method enables researchers to predict metabolic behavior under different environmental conditions or genetic modifications, making it particularly valuable for host selection research in therapeutic development.

Advanced Simulation Techniques

Beyond basic FBA, several advanced simulation methods enhance the predictive capabilities of GEMs:

- Dynamic FBA (dFBA): Extends FBA to simulate time-dependent changes in metabolite concentrations and population dynamics [1]

- 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C MFA): Uses isotopic tracer experiments to measure intracellular metabolic fluxes [1]

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determines the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective function value

- ME-models: Incorporate macromolecular expression constraints, including protein synthesis and allocation [1]

These advanced methods provide increasingly sophisticated insights into metabolic function, enabling more accurate predictions of host-microbe interactions and their implications for therapeutic development.

GEM Applications in Host Selection Research

Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) Development

GEMs play an increasingly important role in the systematic development of Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs), which are promising microbiome-based therapeutics [3]. The GEM-guided framework enables rigorous evaluation of LBP candidate strains based on quality, safety, and efficacy criteria [3].

Table 3: GEM-Based Assessment Criteria for LBP Candidate Strains

| Assessment Category | Evaluation Metrics | GEM Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quality | Metabolic activity, Growth potential, pH tolerance | FBA predicts growth under gastrointestinal conditions [3] |

| Safety | Antibiotic resistance, Drug interactions, Pathogenic potential | Identify risks of toxic metabolite production [3] |

| Efficacy | Therapeutic metabolite production, Host-microbe interactions | Predict SCFA production and immune modulation [3] |

For LBP development, GEMs facilitate both top-down and bottom-up selection approaches. In top-down strategies, microbes are isolated from healthy donor microbiomes, and their GEMs are retrieved from resources like AGORA2 (Assembly of Gut Organisms through Reconstruction and Analysis, version 2), which contains curated strain-level GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes [3]. For bottom-up approaches, GEMs help identify strains with predefined therapeutic functions, such as restoring short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production in inflammatory bowel disease [3].

Host-Microbe Metabolic Interactions

GEMs provide a powerful framework for investigating host-microbe interactions at a systems level, enabling the exploration of metabolic interdependencies and emergent community functions [10] [5]. By simulating metabolic fluxes and cross-feeding relationships, GEMs reveal how hosts and microbes reciprocally influence each other's metabolism.

The integration of host and microbial models presents several technical challenges, particularly in standardizing metabolite and reaction nomenclature across different model sources [5]. Tools such as MetaNetX help bridge these discrepancies by providing a unified namespace for metabolic model components [5]. Despite these challenges, integrated host-microbe models have generated valuable insights into the metabolic basis of various diseases and potential therapeutic interventions.

Drug Target Identification

GEMs contribute significantly to drug discovery by identifying potential therapeutic targets through comprehensive metabolic network analysis. For example, Rajput et al. (2021) reported the potential of bacterial two-component systems as drug targets by performing pan-genome analysis of ESKAPPE pathogens [1]. This approach leverages multi-strain GEM reconstructions to identify conserved essential functions across pathogenic strains, highlighting promising targets for antimicrobial development.

GEMs also enable the prediction of drug-microbiome interactions, identifying how pharmaceutical compounds might be metabolized by commensal microbes or how microbial metabolism might influence drug efficacy [3]. These insights are particularly valuable for personalized medicine approaches, where patient-specific microbial communities can be modeled to predict individual treatment responses.

Computational Tools and Databases

The development and application of GEMs rely on a sophisticated ecosystem of computational tools, databases, and analytical resources that collectively support the entire modeling pipeline.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for GEM Construction and Analysis

| Resource | Type | Function | Relevance to Host Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGORA2 [3] | Model Repository | 7,302 curated gut microbial GEMs | Reference models for host-microbiome studies |

| BiGG Models [11] [5] | Knowledgebase | Curated metabolic reconstructions | Standardized biochemical data for model construction |

| CarveMe [11] [5] | Reconstruction Tool | Automated draft GEM generation | Rapid model building for host-associated microbes |

| MetaNetX [5] | Integration Platform | Unified namespace for metabolites | Enables host-microbe model integration |

| CHESHIRE [11] | Gap-Filling Algorithm | Deep learning for reaction prediction | Improves model completeness without experimental data |

| COBRA Toolbox [5] | Analysis Suite | MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based modeling | Standard platform for FBA and related analyses |

Experimental Validation Protocols

While GEMs are computational tools, their development and refinement depend critically on experimental validation. Key experimental methods for validating GEM predictions include:

- Growth Phenotyping: Measuring microbial growth rates under defined nutritional conditions to validate FBA predictions [1]

- Metabolite Profiling: Quantifying extracellular metabolite concentrations using mass spectrometry or NMR to verify metabolic secretion/uptake predictions [1]

- 13C Tracer Experiments: Using isotopically labeled substrates to validate intracellular flux predictions [1]

- Gene Essentiality Studies: Comparing model-predicted essential genes with experimental gene knockout data [1]

For host-focused applications, additional validation approaches include:

- Gnotobiotic Mouse Models: Using germ-free animals colonized with defined microbial communities to validate host-microbe interaction predictions [3]

- Organoid Co-culture Systems: Testing predicted metabolic interactions in simplified host-microbe experimental systems [5]

- Metatranscriptomics: Comparing predicted metabolic fluxes with gene expression patterns in complex communities [3]

These experimental methods provide critical validation of GEM predictions and contribute to iterative model refinement, enhancing the predictive power and biological relevance of the models for host selection research.

Future Perspectives in GEM Development

The field of genome-scale metabolic modeling continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends particularly relevant to host selection research. The integration of machine learning approaches with traditional constraint-based methods represents a promising direction, potentially enabling more accurate predictions of complex host-microbe metabolic interactions [1]. Methods like CHESHIRE demonstrate how deep learning can enhance GEM quality without requiring extensive experimental data [11].

Another significant trend is the development of multi-scale models that incorporate metabolic, regulatory, and signaling networks to provide more comprehensive representations of cellular physiology [1]. For host selection research, these advanced models could capture the complex interplay between metabolic pathways and immune responses, potentially identifying novel mechanisms for therapeutic intervention.

As the field progresses, standardization of model reconstruction, annotation, and validation protocols will be crucial for enhancing reproducibility and interoperability across studies [5]. Community-driven initiatives such as the AGORA resource [3] represent important steps toward this goal, providing consistently curated models that facilitate comparative analyses and meta-studies relevant to host selection and therapeutic development.

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) Framework Explained

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) is a computational systems biology framework that enables the generation of mechanistic, genome-scale models of metabolic networks. This approach provides a mathematical representation of an organism's metabolism, integrating genomic, biochemical, and physiological information to simulate metabolic capabilities under various conditions [12] [13]. The core principle of COBRA methods is the application of physicochemical and biological constraints to define the set of possible metabolic behaviors for a biological system, typically without requiring comprehensive kinetic parameters [14]. These constraints include mass conservation, thermodynamic directionality, and reaction capacity limitations, which collectively narrow the range of possible metabolic flux distributions to those that are physiologically feasible.

The COBRA framework has evolved substantially since its inception, with ongoing development of sophisticated software tools that implement its methodologies. The most prominent implementations include the COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB and COBRApy for Python [14] [12]. These tools provide researchers with accessible platforms for constructing, simulating, and analyzing genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), enabling diverse applications from basic metabolic research to biotechnology and biomedical investigations. The framework's flexibility allows it to be adapted for modeling increasingly complex biological processes, including multi-species interactions and integration of multi-omics data types [14] [13].

In the context of host selection research, COBRA methods offer a powerful approach for investigating metabolic interactions between hosts and microorganisms. By reconstructing GEMs for both host and microbial species, researchers can simulate their metabolic cross-talk, identify potential metabolic dependencies, and predict how these interactions influence host health and disease states [15]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding the mechanistic basis of host-microbe relationships and for identifying potential therapeutic targets that could modulate these interactions for clinical benefit.

Core Principles and Mathematical Foundations

Stoichiometric Matrix and Mass Balance Constraints

The fundamental mathematical structure underlying COBRA models is the stoichiometric matrix S, where each element Sₙₘ represents the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite n in reaction m. This matrix encodes the network topology of the metabolic system and enables the application of mass balance constraints via the equation:

S · v = 0

where v is the vector of metabolic reaction fluxes [16] [13]. This equation enforces the pseudo-steady state assumption, implying that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time despite ongoing metabolic activity. The mass balance constraint ensures that for each internal metabolite, the rate of production equals the rate of consumption, reflecting metabolic homeostasis.

Flux Capacity Constraints and Objective Functions

In addition to mass balance, COBRA models incorporate flux capacity constraints that define the minimum and maximum possible rates for each reaction:

vₘᵢₙ ≤ v ≤ vₘâ‚â‚“

These bounds encode biochemical and physiological limitations, such as enzyme capacity, substrate availability, and thermodynamic feasibility [14] [13]. Irreversible reactions are constrained to carry only non-negative fluxes (v ≥ 0), while reversible reactions can carry either positive or negative fluxes. The flux bounds can be further refined based on experimental measurements, omics data integration, or condition-specific constraints.

To simulate metabolic behavior, COBRA methods employ optimization approaches, typically linear programming, to identify flux distributions that maximize or minimize a biologically relevant objective function. The most common objective function is biomass production, which represents cellular growth and is formulated as a reaction that drains biomass constituents in their experimentally determined proportions [16]. Other objective functions may include ATP production, synthesis of specific metabolites, or minimization of metabolic adjustment.

Figure 1: Mathematical foundation of COBRA methods showing how biological data and constraints are integrated to predict metabolic flux distributions.

COBRA Workflow: From Reconstruction to Simulation

The application of the COBRA framework follows a systematic workflow that transforms genomic information into predictive metabolic models. The key steps in this process include:

Genome Annotation: Identification of metabolic genes and their functions through sequence analysis and comparison with databases [16].

Reaction Network Assembly: Compilation of biochemical reactions associated with the annotated genes, including metabolite stoichiometry, reaction directionality, and compartmentalization [12].

Biomass Composition Definition: Formulation of a biomass objective function that represents the drain of cellular constituents required for growth, based on experimental measurements of macromolecular composition [16].

Model Validation and Refinement: Iterative testing of model predictions against experimental data, followed by gap-filling and curation to improve accuracy [12] [16].

Constraint Integration: Application of condition-specific constraints, such as nutrient availability or gene expression data, to define the metabolic state space [13].

Simulation and Analysis: Use of optimization techniques to predict metabolic phenotypes and interpret the results in a biological context [12].

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for COBRA Implementation

| Tool Name | Platform | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [12] | MATLAB | Comprehensive metabolic modeling | Extensive method library, community support, multi-omics integration |

| COBRApy [14] | Python | Object-oriented constraint-based modeling | Open-source, parallel processing, ME-model support |

| MicroMap [17] | Web-based | Metabolic network visualization | Interactive exploration, modeling result display, educational utility |

| ModelSEED [16] | Web-based | Automated model reconstruction | Rapid draft model generation, gap-filling, standard biochemistry |

For host selection research, this workflow can be extended to construct integrated host-microbiome models. This involves developing separate GEMs for host and microbial species, then connecting them through a shared extracellular environment that enables metabolite exchange [15]. The resulting community models can simulate metabolic interactions, identify cross-feeding relationships, and predict how microbial colonization influences host metabolic states.

Figure 2: Systematic workflow for developing and applying genome-scale metabolic models using the COBRA framework.

COBRA Applications in Host-Microbe Metabolic Modeling

The COBRA framework provides powerful capabilities for investigating host-microbe interactions at a systems level. By simulating metabolic fluxes and cross-feeding relationships, COBRA models enable researchers to explore metabolic interdependencies and emergent community functions that arise from these complex biological relationships [15]. Specific applications in host selection research include:

Identification of Metabolic Cross-Feeding

COBRA methods can predict metabolite exchange between hosts and microbes, revealing how each organism's metabolic capabilities complement the other. For example, models can simulate how gut microbes metabolize dietary components that the host cannot digest, producing short-chain fatty acids and other metabolites that the host then utilizes [15] [17]. These simulations help explain the metabolic basis of microbial colonization and persistence in specific host environments.

Prediction of Community Metabolic States

Integrated host-microbiome models can predict how changes in diet, environmental conditions, or genetic variations affect the metabolic output of the entire system. For instance, researchers have used COBRA approaches to model how different microbial communities influence host energy harvest, vitamin production, and immune modulation [15]. These predictions provide testable hypotheses about how microbial metabolic activities impact host physiology and health outcomes.

Analysis of Pathogen Metabolism

COBRA models of pathogenic microorganisms, such as Streptococcus suis, have been used to identify metabolic vulnerabilities that could be exploited for antimicrobial development [16]. By simulating pathogen metabolism in host-like conditions, researchers can pinpoint essential metabolic functions that are required for virulence or survival in the host environment. These model-driven predictions can guide experimental validation and drug target prioritization.

Table 2: Examples of Metabolic Models in Host-Microbe Research

| Organism/System | Model Characteristics | Application in Host Selection Research |

|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus suis [16] | 525 genes, 708 metabolites, 818 reactions | Identification of virulence-linked metabolic genes and drug targets |

| Human Gut Microbiome [17] | 257,429 microbial reconstructions, 5,064 reactions | Mapping community metabolic capabilities and metabolite exchange |

| Host-Microbe Interactions [15] | Multi-species community modeling | Prediction of metabolic dependencies and cross-feeding relationships |

The MicroMap resource represents a significant advancement for visualizing microbiome metabolism, capturing the metabolic content of over a quarter million microbial GEMs [17]. This visualization tool enables researchers to intuitively explore microbiome metabolic networks, compare capabilities across different microbial taxa, and display computational modeling results in a biochemical context. For host selection research, such resources facilitate the interpretation of how specific microbial metabolic capabilities might complement or disrupt host metabolic functions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Metabolic Model Reconstruction

The reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models follows a standardized protocol implemented in tools like the COBRA Toolbox and COBRApy [12] [16]:

Genome Annotation and Draft Reconstruction

- Annotate the target genome using RAST or similar annotation pipelines

- Generate a draft model using automated tools like ModelSEED

- Identify homologous genes in reference organisms using BLAST (identity ≥40%, match lengths ≥70%)

- Compile gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations from reference models

Manual Curation and Gap-Filling

- Identify metabolic gaps using gapAnalysis algorithms in the COBRA Toolbox

- Manually add missing reactions based on literature evidence and biochemical databases

- Balance reactions for mass and charge by adding H₂O or H⺠as needed

- Validate reaction directionality using thermodynamic calculations

Biomass Objective Function Formulation

- Determine macromolecular composition (proteins, DNA, RNA, lipids, etc.) from experimental data or related organisms

- Calculate biomass precursors based on organism-specific composition

- Incorporate energy requirements (ATP maintenance) for growth-associated maintenance

Model Validation and Testing

- Test model predictions against experimental growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions

- Compare gene essentiality predictions with mutant library screens

- Validate model predictions using leave-one-out experiments in defined media

Flux Balance Analysis Methodology

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the primary simulation technique used in COBRA methods [16] [13]:

Problem Formulation

- Define the stoichiometric matrix S based on the metabolic network

- Set flux bounds vₘᵢₙ and vₘâ‚â‚“ for each reaction based on condition-specific constraints

- Define the objective function Z = cᵀ·v, typically biomass production

Optimization Setup

- Formulate the linear programming problem: Maximize Z = cᵀ·v Subject to: S·v = 0 and vₘᵢₙ ≤ v ≤ vₘâ‚â‚“

- Select an appropriate solver (e.g., GUROBI) for numerical optimization

Simulation and Analysis

- Solve the optimization problem to obtain a flux distribution

- Perform flux variability analysis to identify alternative optimal solutions

- Conduct gene deletion studies by constraining associated reaction fluxes to zero

- Calculate growth rates or metabolite production capabilities

For host-microbiome modeling, additional steps are required to integrate individual models and simulate their interactions [15]:

Community Model Construction

- Create a compartmentalized extracellular space shared between host and microbial models

- Define metabolite exchange reactions that connect the individual metabolic networks

- Implement appropriate constraints on exchange fluxes based on environmental conditions

Community Simulation

- Define joint objective functions that represent community fitness or specific metabolic outputs

- Apply constraints that reflect the physiological context of the host environment

- Simulate metabolic interactions and identify cross-feeding relationships

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for COBRA Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in COBRA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | COBRA Toolbox v.3.0 [12] | Comprehensive protocol implementation for constraint-based modeling |

| COBRApy [14] | Python-based, open-source modeling with support for complex datasets | |

| Database Resources | Virtual Metabolic Human (VMH) [17] | Curated biochemical database for human and microbiome metabolism |

| AGORA2 & APOLLO [17] | Resource of 7302 microbial strain-level metabolic reconstructions | |

| Visualization Tools | MicroMap [17] | Network visualization of microbiome metabolism with 5064 reactions |

| ReconMap [17] | Metabolic map for human metabolism, compatible with COBRA Toolbox | |

| Analysis Functions | Flux Balance Analysis [16] | Prediction of optimal metabolic flux distributions |

| Flux Variability Analysis [14] | Identification of range of possible fluxes for each reaction | |

| Gene Deletion Analysis [16] | Prediction of essential genes and synthetic lethal interactions |

The COBRA framework continues to evolve, with ongoing developments focused on addressing several key challenges in metabolic modeling. Future directions include the integration of multi-omics data types to create more context-specific models, the development of methods for modeling microbial communities of increasing complexity, and the incorporation of additional cellular processes beyond metabolism [15] [13]. For host selection research, these advancements will enable more accurate predictions of how microbial metabolic activities influence host physiology and how these relationships might be targeted for therapeutic intervention.

The creation of resources like MicroMap, which provides visualization capabilities for microbiome metabolism, represents an important step toward making COBRA methods more accessible to researchers without extensive computational backgrounds [17]. Such tools help diversify the computational modeling community and facilitate collaboration between wet-lab and dry-lab researchers. As these resources continue to expand and improve, they will further enhance the utility of COBRA methods for investigating the complex metabolic interactions between hosts and their associated microorganisms.

In conclusion, the COBRA framework provides a powerful systems biology approach for reconstructing and analyzing genome-scale metabolic networks. Its application to host selection research offers unprecedented opportunities to understand the metabolic basis of host-microbe interactions, identify key vulnerabilities in pathogenic organisms, and develop novel therapeutic strategies that target metabolic dependencies. As the field continues to advance, COBRA methods will play an increasingly important role in deciphering the complex metabolic relationships that influence health and disease.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical approach for simulating the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling researchers to predict organism behavior under specific constraints without requiring difficult-to-measure kinetic parameters [18] [19]. As a constraint-based modeling technique, FBA has become indispensable for analyzing genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs)—computational representations of all known metabolic reactions in an organism based on its genomic information [20]. In the context of host selection research, particularly for understanding host-pathogen interactions and human microbiome metabolism, FBA provides a mechanistic framework to investigate how metabolic reprogramming influences disease progression and therapeutic outcomes [21] [22].

The fundamental principle underlying FBA is that metabolic networks operate under steady-state conditions, where metabolite concentrations remain constant because production and consumption rates are balanced [18] [20]. This steady-state assumption, combined with the application of constraints derived from stoichiometry, reaction thermodynamics, and environmental conditions, defines a solution space of possible metabolic behaviors [19]. FBA then identifies an optimal flux distribution within this space by maximizing or minimizing a biologically relevant objective function, such as biomass production (simulating growth) or ATP synthesis [20] [19]. The ability to predict system-level metabolic adaptations makes FBA particularly valuable for studying complex biological systems where host and microbial metabolisms interact.

Mathematical Foundation and Core Principles

Stoichiometric Modeling and Constraint Formulation

The mathematical foundation of FBA begins with representing the metabolic network as a stoichiometric matrix S of size m×n, where m represents the number of metabolites and n represents the number of metabolic reactions [20] [19]. Each element Sᵢⱼ in this matrix contains the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j, with negative values indicating consumption and positive values indicating production [19]. The metabolic fluxes through all reactions are contained in the vector v of length n. The steady-state assumption that metabolite concentrations do not change over time leads to the fundamental mass balance equation:

S â‹… v = 0

This equation states that for every metabolite in the system, the weighted sum of fluxes producing that metabolite must equal the weighted sum of fluxes consuming it [20]. For large-scale metabolic models, this system of equations is typically underdetermined (more reactions than metabolites), meaning multiple flux distributions can satisfy the mass balance constraints [19].

Applying Constraints and Objective Functions

To identify a biologically relevant flux distribution from the possible solutions, FBA incorporates two additional types of constraints:

Flux constraints: Each reaction flux vᵢ is constrained by lower and upper bounds (αᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ βᵢ) that define its minimum and maximum allowable rates [20]. These bounds can represent thermodynamic constraints (irreversible reactions have a lower bound of 0), enzyme capacity limitations, or environmental conditions (e.g., nutrient availability) [18] [19].

Objective function: An objective function Z = cáµ€v is defined, representing a biological goal that the organism is presumed to optimize, such as maximizing biomass production or ATP yield [20] [19]. The vector c contains weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective.

The complete FBA problem can be formulated as a linear programming optimization:

maximize cᵀv subject to S ⋅ v = 0 and αᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ βᵢ for all i

The output is a specific flux distribution v that maximizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints [20] [19].

Computational Framework and Workflow

The practical implementation of FBA follows a systematic workflow that transforms biological knowledge into predictive computational models. The following diagram illustrates the core FBA workflow:

Genome-Scale Metabolic Model Reconstruction

The foundation of any FBA simulation is a high-quality, genome-scale metabolic reconstruction that contains all known metabolic reactions for a target organism [20]. The iML1515 model of E. coli K-12 MG1655 exemplifies such a reconstruction, containing 1,515 genes, 2,719 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites [18]. For host-microbiome research, resources like AGORA2 provide curated metabolic reconstructions for 7,302 human microorganisms, enabling strain-resolved modeling of personalized microbiome metabolism [22]. The reconstruction process involves:

- Genome annotation to identify metabolic genes

- Reaction assembly based on biochemical literature and databases

- Compartmentalization of reactions into appropriate cellular locations

- Biomass composition definition based on experimental measurements

- Gap analysis to identify and fill missing metabolic functions

Environmental and Enzymatic Constraints

To simulate specific experimental or physiological conditions, appropriate constraints must be applied to the metabolic model:

- Media constraints: Upper bounds on exchange reactions define available nutrients [18]. For example, glucose uptake might be limited to 18.5 mmol/gDW/h to simulate a specific growth condition [19].

- Gene knockouts: Simulating gene deletions by constraining associated reaction fluxes to zero [20]. The effects are evaluated using Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules that describe Boolean relationships between genes and reactions [20].

- Enzyme constraints: Incorporating enzyme capacity limitations using kinetic parameters (kcat values) and enzyme abundances to avoid unrealistic flux predictions [18]. Tools like ECMpy facilitate adding these constraints without altering the core stoichiometric matrix [18].

Advanced FBA Techniques for Host-Pathogen Research

Basic FBA has been extended with numerous advanced algorithms to address specific research questions in host selection and pathogen metabolism:

- Dynamic FBA: Extends FBA to multiple timepoints to simulate time-dependent changes in metabolite concentrations and biomass [23].

- Flux Variability Analysis: Identifies the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective function value [19], revealing alternative optimal solutions.

- Regulatory FBA: Incorporates gene regulatory constraints alongside metabolic constraints using Boolean logic rules [23].

- TIObjFind: A recently developed framework that integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis with FBA to identify context-specific objective functions from experimental data [23]. This approach calculates Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to the objective function, particularly valuable for understanding metabolic adaptations in host environments [23].

Experimental Design and Protocol Implementation

Protocol for Constraint-Based Modeling of Host-Pathogen Systems

Implementing FBA for host selection research requires careful experimental design and protocol implementation. The following workflow illustrates the key steps for applying FBA to study host-pathogen metabolic interactions:

Step 1: Model Selection and Customization

Select appropriate genome-scale metabolic models for both host and microbial components. For human host modeling, Recon3D provides a comprehensive reconstruction of human metabolism [17], while for microbiome components, AGORA2 offers 7,302 microbial strain reconstructions [22]. Context-specific models can be created using transcriptomic data to constrain the model to only include reactions active in particular conditions [21]. For example, in studying HIV infection, PBMC-specific models were created using RNA sequencing data from people living with HIV (PLWH) to investigate metabolic reprogramming in immune cells [21].

Step 2: Incorporation of Enzyme Constraints

To improve prediction accuracy, incorporate enzyme constraints using the ECMpy workflow [18]. This process involves:

- Splitting reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions to assign distinct kcat values

- Separating reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions

- Obtaining kcat values from BRENDA database and enzyme abundance data from PAXdb

- Setting the total protein fraction constraint (typically 0.56 for E. coli) [18]

- Modifying kcat values and gene abundances to reflect genetic engineering interventions

Step 3: Medium Composition Definition

Define extracellular environment by constraining uptake reactions for specific medium components. For example, in modeling L-cysteine overproduction in E. coli, the SM1 + LB medium was represented by setting upper bounds on glucose (55.51 mmol/gDW/h), citrate (5.29 mmol/gDW/h), ammonium ion (554.32 mmol/gDW/h), and other components [18]. Critical nutrients like thiosulfate were included with an upper bound of 44.60 mmol/gDW/h to reflect its importance in L-cysteine production pathways [18].

Step 4: Implementation of Lexicographic Optimization

When optimizing for metabolite production rather than growth, implement lexicographic optimization to ensure biologically realistic solutions [18]. This two-step process involves:

- First optimizing for biomass production to determine maximum growth rate

- Then constraining growth to a percentage of maximum (e.g., 30%) while optimizing for the target product (e.g., L-cysteine export) [18]

This approach prevents solutions where product formation is maximized at the expense of cell growth, which may not be sustainable in real biological systems.

Protocol for Drug Metabolism Analysis in Personalized Microbiome Models

For drug development applications, FBA can predict microbial drug metabolism using the following protocol:

- Strain-resolved microbiome modeling: Construct personalized microbiome models using AGORA2, which includes drug degradation and biotransformation capabilities for 98 commonly prescribed drugs [22].

- Drug transformation mapping: Identify which microbial strains in an individual's microbiome contain reactions for specific drug transformations using the MicroMap visualization resource [17].

- Flux prediction: Simulate drug metabolism fluxes under personalized nutritional and pharmacological constraints [22].

- Interindividual variability assessment: Compare drug conversion potential across individuals and correlate with factors like age, sex, BMI, and disease status [22].

Data Presentation and Quantitative Analysis

Metabolic Modeling of HIV Infection Reveals Altered Energy Metabolism

Application of FBA to study metabolic adaptations in HIV infection revealed significant alterations in energy metabolism. Using context-specific PBMC models built from RNA sequencing data, researchers compared people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (PLWHART) with HIV-negative controls (HC) and elite controllers (PLWHEC) who naturally control viral replication [21]. Flux balance analysis identified altered flux in several intermediates of glycolysis including pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate, and glutamate in PLWHART [21]. Furthermore, transcriptomic analysis identified up-regulation of oxidative phosphorylation as a characteristic of PLWHART, differentiating them from PLWHEC with dysregulated complexes I, III, and IV [21].

Table 1: Key Findings from FBA Study of HIV Metabolic Adaptation

| Comparison Group | Key Metabolic Findings | Transcriptomic Signatures | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLWHART (n=19) | Altered flux in glycolytic intermediates; Up-regulated OXPHOS | 1,037 specifically dysregulated genes; OXPHOS pathway enrichment | Pharmacological inhibition of complexes I/III/IV induced apoptosis |

| PLWHEC (n=19) | Distinct metabolic uptake and flux profile | No genes dysregulated vs HC; Unique metabolic signature | Natural control associated with metabolic profile |

| HC (n=19) | Baseline metabolic flux distribution | Reference expression profile | - |

Medium Optimization for Metabolic Engineering

FBA enables precise optimization of growth media components to enhance product yields in metabolic engineering applications. The following table illustrates example upper bounds for uptake reactions in SM1 medium for L-cysteine overproduction in E. coli:

Table 2: Upper Bounds for Uptake Reactions in SM1 Medium for L-Cysteine Overproduction [18]

| Medium Component | Associated Uptake Reaction | Upper Bound (mmol/gDW/h) |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | EXglcDe_reverse | 55.51 |

| Citrate | EXcite_reverse | 5.29 |

| Ammonium Ion | EXnh4e_reverse | 554.32 |

| Phosphate | EXpie_reverse | 157.94 |

| Magnesium | EXmg2e_reverse | 12.34 |

| Sulfate | EXso4e_reverse | 5.75 |

| Thiosulfate | EXtsule_reverse | 44.60 |

Successful implementation of FBA requires specialized computational tools and databases. The following essential resources represent the current state-of-the-art in constraint-based modeling:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Flux Balance Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Application in Host Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [19] | MATLAB Toolbox | Primary computational platform for FBA simulations | Simulation of host and microbial metabolism |

| AGORA2 [22] | Metabolic Reconstruction Resource | 7,302 manually curated microbial metabolic models | Personalized modeling of gut microbiome metabolism |

| Virtual Metabolic Human (VMH) [17] [22] | Database | Integrated knowledgebase of human metabolism | Host-microbiome cometabolism studies |

| DEMETER [22] | Reconstruction Pipeline | Data-driven metabolic network refinement | Generation of high-quality context-specific models |

| ECMpy [18] | Python Package | Addition of enzyme constraints to metabolic models | Improved flux prediction accuracy |

| MicroMap [17] | Visualization Resource | Network visualization of microbiome metabolism | Exploration of metabolic capabilities across microbes |

| BRENDA [18] | Enzyme Database | Comprehensive collection of enzyme kinetic data | Parameterization of enzyme constraints |

| PAXdb [18] | Protein Abundance Database | Global protein abundance measurements | Constraining enzyme capacity limits |

Flux Balance Analysis provides a powerful computational framework for simulating metabolic phenotypes under constraints, with significant applications in host selection research and drug development. By integrating genome-scale metabolic models with context-specific constraints, FBA enables researchers to predict how metabolic reprogramming influences host-pathogen interactions, therapeutic efficacy, and disease progression. The continued development of resources like AGORA2 for microbiome research and advanced algorithms like TIObjFind for identifying context-specific objective functions will further enhance our ability to model complex biological systems. As these methods become more sophisticated and accessible, FBA will play an increasingly important role in personalized medicine approaches that account for individual metabolic variations in both human hosts and their associated microbial communities.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have emerged as powerful computational frameworks for deciphering the complex metabolic interactions between hosts and their associated microbial communities. By providing a mathematical representation of metabolic networks based on genomic annotations, GEMs enable researchers to simulate metabolic fluxes and cross-feeding relationships that underlie host-microbe symbiosis and dysbiosis. This technical review examines how constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) approaches are revolutionizing therapeutic development, particularly for live biotherapeutic products (LBPs), by offering systems-level insights into metabolic interdependencies. We detail the methodological pipeline for constructing and validating host-microbe metabolic models, present quantitative analyses of their applications in disease-specific contexts, and provide standardized protocols for implementing these approaches in therapeutic discovery pipelines. The integration of GEMs with multi-omic data represents a paradigm shift in identifying precise microbial therapeutic targets and designing personalized microbiome-based interventions.

All eukaryotic host organisms exist in intimate association with diverse microbial communities, forming functional metaorganisms or holobionts where host and microbial genomes co-evolve and reciprocally adapt [5]. These complex relationships result in intricate metabolic interactions that profoundly influence host physiology, ranging from immune regulation and nutrient processing to neurological function [5] [3]. The collective metabolic function of these communities emerges from complex interactions among microbes themselves and with their host environments, creating cross-feeding relationships and metabolic interdependencies that stabilize the ecosystem [5].

Disruption of these finely tuned metabolic relationships, known as dysbiosis, has been implicated in a wide range of diseases including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer [3]. Traditional reductionistic approaches have proven limited in capturing the complexity of these natural ecosystems, creating an urgent need for computational frameworks that can integrate host and microbial metabolic capabilities [5]. Genome-scale metabolic modeling has emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, enabling researchers to investigate host-microbe interactions at a systems level and accelerating the development of novel therapeutics targeting these metabolic relationships [5] [3].

Technical Foundations of Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA)

Constraint-based modeling approaches, particularly flux balance analysis (FBA), form the cornerstone of genome-scale metabolic modeling. This mathematical framework represents metabolic networks as a stoichiometric matrix (S) where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent biochemical reactions [5] [24]. The fundamental equation describing metabolic flux distributions is:

Sv = dx/dt

where v represents the flux vector of all reactions and dx/dt denotes changes in metabolite concentrations over time [24]. Assuming steady-state conditions, where internal metabolite concentrations remain constant, this equation simplifies to:

Sv = 0

This formulation ensures mass-balance where the total flux of metabolites into any reaction equals outflux, preventing thermodynamically infeasible metabolite accumulation or depletion [5] [24]. To solve the underdetermined system resulting from more reactions than metabolites, constraint-based modeling applies additional constraints in the form of reaction flux boundaries and optimizes an objective function—typically biomass production for microbial growth or ATP production for host cellular functions [5] [24].

Model Reconstruction and Integration Pipeline

Developing integrated host-microbe metabolic models involves a multi-step process with distinct technical considerations for host and microbial components:

Table 1: Key Steps in Host-Microbe GEM Development

| Step | Host Model Considerations | Microbial Model Considerations | Tools & Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Input Data Generation | Tissue-specific transcriptomics, physiological data | Genome sequences, metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) | Sequencing platforms, metabolic phenotyping |

| 2. Model Reconstruction | Complex due to compartmentalization, incomplete annotations; manual curation essential | Relatively straightforward with automated pipelines | AGORA, BiGG, ModelSEED, CarveMe, gapseq [5] |

| 3. Model Integration | Standardization of metabolite/reaction nomenclature across models | Detection/removal of thermodynamically infeasible loops | MetaNetX, COBRA Toolbox [5] |

| 4. Contextualization | Integration of tissue-specific omics data | Incorporation of community metabolic profiling | mCADRE, INIT, FASTCORE [5] |

Reconstructing host metabolic models, particularly for multicellular eukaryotes, presents unique challenges including incomplete genome annotations, precise definition of biomass composition, and metabolic compartmentalization within organelles [5]. In contrast, microbial metabolic models benefit from well-curated repositories like AGORA2, which contains strain-level GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes, and automated reconstruction tools such as ModelSEED and CarveMe [5] [3]. The integration phase must overcome nomenclature discrepancies between models and eliminate thermodynamically infeasible reaction cycles that create free energy metabolites [5].

GEMs in Therapeutic Development: Applications and Quantitative Insights

Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs) Development

GEMs provide a systematic framework for screening, evaluating, and designing live biotherapeutic products by predicting metabolic interactions between candidate strains, resident microbes, and host cells [3]. The AGORA2 resource, containing 7,302 curated strain-level GEMs of gut microbes, enables both top-down screening (isolating strains from healthy donor microbiomes) and bottom-up approaches (selecting strains based on predefined therapeutic objectives) [3]. For example, pairwise growth simulations have identified 803 GEMs with antagonistic activity against pathogenic Escherichia coli, leading to the selection of Bifidobacterium breve and Bifidobacterium animalis as promising candidates for colitis alleviation [3].

GEMs further support LBP development by optimizing growth conditions for fastidious microorganisms, characterizing strain-specific therapeutic functions, predicting postbiotic production, and identifying gene modification targets for engineered LBPs [3]. This approach has been successfully applied to optimize chemically defined media for Bifidobacterium animalis and Bifidobacterium longum, and to identify gene-editing targets for overproduction of the immune-modulating metabolite butyrate [3].

Insights from Host-Microbe Metabolic Studies

Recent applications of integrated host-microbe metabolic models have revealed crucial aspects of metabolic interdependencies with direct therapeutic relevance:

Table 2: Key Findings from Host-Microbe Metabolic Modeling Studies

| Study System | Key Metabolic Findings | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Aging Mouse Model [25] | Age-related reduction in microbiome metabolic activity; decreased beneficial interactions; specific declines in nucleotide metabolism | Identifies targets for microbiome-based anti-aging therapies; explains inflammaging through metabolic decline |

| Thermophilic Communities [26] | Metabolic complementarity increases with temperature stress; amino acids, coenzyme A derivatives, and carbohydrates are key exchange metabolites | Informs design of microbial consortia for industrial applications; reveals environmental stress as driver of metabolic cooperation |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease [3] | Purine metabolism correlations between host and microbiome; microbial galactose/arabinose degradation negatively correlates with host immune processes | Suggests microbial metabolites as biomarkers; identifies strain-specific therapeutic targets |

In aging research, integrated metabolic models of host and 181 mouse gut microorganisms revealed a pronounced reduction in metabolic activity within the aging microbiome, accompanied by reduced beneficial interactions between bacterial species [25]. These changes coincided with increased systemic inflammation and the downregulation of essential host pathways, particularly in nucleotide metabolism, predicted to rely on the microbiota and critical for preserving intestinal barrier function, cellular replication, and homeostasis [25].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Integrated Host-Microbiome Metabolic Modeling Workflow

GEM-Guided LBP Screening and Validation Protocol

The following detailed protocol outlines the systematic approach for applying GEMs in live biotherapeutic product development:

Candidate Strain Shortlisting

- Perform top-down screening using AGORA2 database or bottom-up approach based on predefined therapeutic objectives

- Conduct qualitative assessment of metabolite exchange reactions across GEMs

- Execute pairwise growth simulations to screen interspecies interactions

- Apply random matrix theory (RMT) to identify significant metabolic interactions

Quality and Safety Evaluation

- Predict growth rates across diverse nutritional conditions using flux balance analysis

- Assess pH tolerance through simulation of gastrointestinal stressors

- Evaluate antibiotic resistance potential by predicting auxotrophic dependencies

- Identify drug interaction risks through curated degradation and biotransformation reactions

Therapeutic Efficacy Assessment

- Simulate production potential of therapeutic metabolites (e.g., SCFAs) under disease-relevant conditions

- Predict interactions between exogenous LBPs and resident microbes

- Identify gene modification targets for engineered LBPs using bi-level optimization

- Validate predictions through in vitro and animal model experiments

Multi-Strain Formulation Optimization

- Quantitatively rank individual strains or combinations based on predictive metrics

- Design personalized formulations accounting for interindividual microbiome variability

- Evaluate strain compatibility and community stability through dynamic flux balance analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Host-Microbe Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Functionality | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Reconstruction | ModelSEED, CarveMe, gapseq, RAVEN, AuReMe | Automated draft model generation from genomic data | Rapid development of strain-specific models for LBP candidates |

| Curated Model Repositories | AGORA2 (7,302 gut microbes), BiGG, APOLLO | Access to pre-curated, validated metabolic models | Screening of therapeutic strains from comprehensive databases |

| Simulation & Analysis | COBRA Toolbox, SBMLsimulator, Gurobi/CPLEX | Flux balance analysis and constraint-based modeling | Prediction of metabolic behavior under therapeutic conditions |

| Data Integration & Standardization | MetaNetX, Escher | Namespace reconciliation and visualization | Integration of host and microbial models; data contextualization |

| Experimental Validation | ¹³C metabolic flux analysis, LC-MS/MS, NMR | Measurement of intracellular fluxes and metabolite levels | Validation of model predictions in laboratory settings |

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Despite significant advances, several technical challenges remain in fully realizing the potential of metabolic modeling for therapeutic development. The lack of standardized formats and model integration pipelines continues to hinder the seamless construction of host-microbe models [5]. Additionally, the compartmentalization of eukaryotic metabolism and incomplete annotation of host genomes complicates the reconstruction of accurate host metabolic models [5]. There is also a critical need for improved methods to incorporate dynamic regulation and spatial organization of metabolic processes within host tissues [5] [24].

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing model precision through integration of multi-omic datasets (metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics), incorporating microbial gene regulatory networks, and accounting for interindividual variability in host and microbiome composition [3] [25]. The emerging application of GEMs in personalized medicine approaches will require streamlined workflows for rapid model construction and validation from patient-specific data [3]. Furthermore, integrating metabolic models with immune signaling pathways and host regulatory networks will provide a more comprehensive understanding of how microbial metabolism influences therapeutic outcomes across different disease contexts [25].

Genome-scale metabolic modeling represents a transformative approach for deciphering host-microbe metabolic interdependencies and accelerating therapeutic development. By providing a systems-level framework to simulate metabolic interactions, GEMs enable researchers to move beyond correlative observations to mechanistic, predictive understanding of how microbial communities influence host health and disease. The continued refinement of these computational approaches, coupled with strategic experimental validation, promises to unlock novel microbiome-based therapeutics precisely targeted to restore beneficial host-microbe metabolic relationships disrupted in disease states. As the field advances, GEMs will play an increasingly central role in bridging the gap between microbial ecology and therapeutic innovation, ultimately enabling more effective and personalized interventions for a wide range of diseases linked to host-microbe interactions.