Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME): A Complete Protocol Guide for Strain Improvement

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME), a powerful directed evolution technique for reprogramming cellular physiology and improving industrial microbial strains.

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME): A Complete Protocol Guide for Strain Improvement

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME), a powerful directed evolution technique for reprogramming cellular physiology and improving industrial microbial strains. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles and step-by-step methodological protocols to advanced troubleshooting, optimization strategies, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current knowledge and best practices, this guide aims to equip practitioners with the tools to effectively implement gTME for applications in biopharmaceuticals, biofuels, and biochemical production, thereby accelerating the development of high-performing microbial cell factories.

Understanding gTME: Principles and Core Concepts for Cellular Reprogramming

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) is an advanced metabolic engineering strategy that enhances complex cellular phenotypes by reprogramming the global transcriptional network. This approach involves the directed evolution of key components of the transcription machinery, such as sigma factors in bacteria or TATA-binding proteins in eukaryotes, to alter promoter recognition and modulate transcriptional profiles genome-wide. This article provides a comprehensive technical overview of gTME methodology, featuring detailed protocols, quantitative performance data, and essential resource guidelines for implementing this powerful strain improvement technique in microbial hosts.

Conceptual Framework

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering by addressing a fundamental limitation: most cellular phenotypes are polygenic traits influenced by many genes [1]. Traditional genetic engineering approaches target individual genes or pathways, which often yields suboptimal results for complex phenotypes involving multiple cellular processes. gTME circumvents this limitation by enabling simultaneous multiple gene modification through strategic engineering of the global transcription apparatus [1].

The fundamental premise of gTME is that cellular phenotypes emerge from complex gene networks rather than individual genes. By engineering components of the core transcription machinery—specifically sigma factors in prokaryotes or TATA-binding proteins in eukaryotes—researchers can induce global perturbations of the transcriptome that unlock phenotypic improvements not accessible through traditional approaches [1]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance in optimizing challenging phenotypes including ethanol tolerance, metabolite overproduction, and multiple stress resistances [1].

Theoretical Rationale

The molecular rationale for gTME centers on the sigma factor's crucial role in promoter recognition and transcription initiation. As the primary sigma factor in bacteria, RpoD (σâ·â°) directs RNA polymerase to specific promoter sequences, thereby controlling the expression of essential housekeeping genes [2]. Mutations in sigma factors can alter promoter preferences of RNA polymerase, leading to modulated transcriptional levels across the entire genome [2]. This global transcriptome engineering enables coordinated expression changes across multiple metabolic pathways simultaneously, making it particularly effective for complex phenotypes that involve trade-offs between growth, production, and stress tolerance.

gTME Methodology and Experimental Workflow

Core Experimental Framework

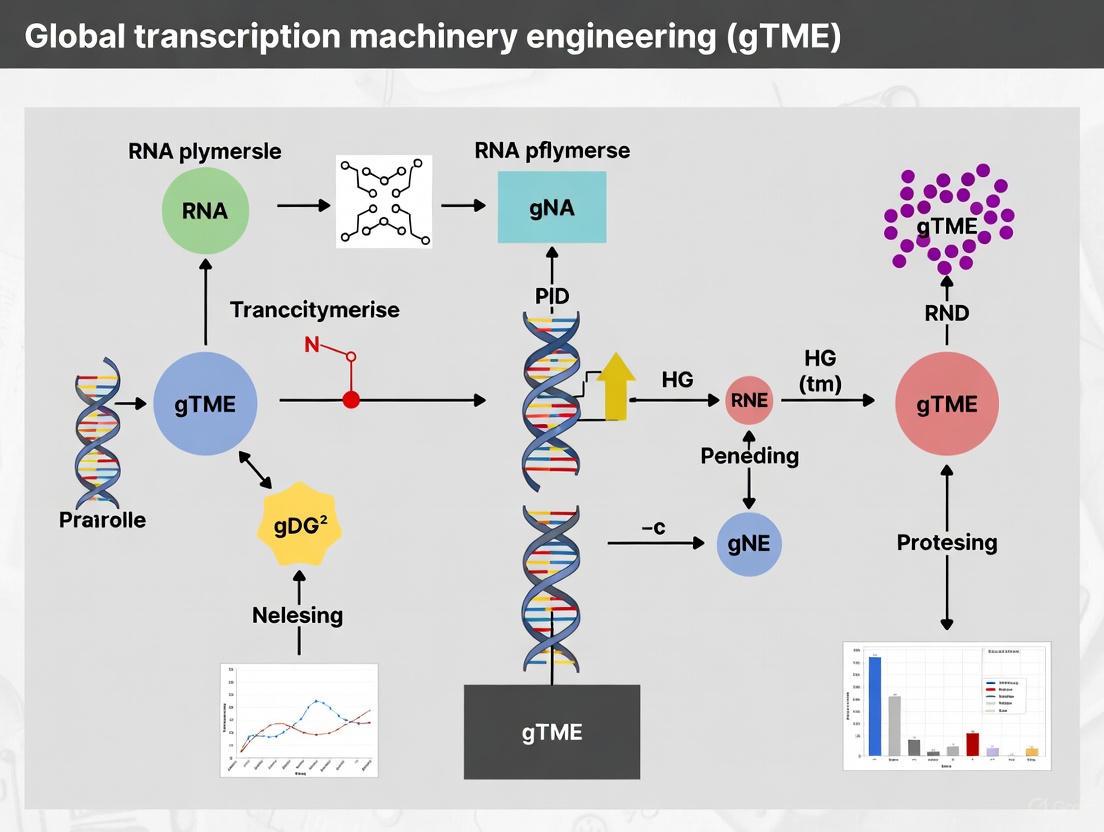

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive gTME workflow from library construction to mutant validation:

Detailed Protocol: Enhancing Ethanol Tolerance in Zymomonas mobilis

Library Construction Phase

Step 1: Error-Prone PCR Mutagenesis

- Template: 180 ng of purified rpoD gene (encoding σâ·â°) [2]

- PCR Conditions: Utilize GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit with varying template concentrations to achieve different mutation rates:

- Low mutation rate: 0–4.5 mutations/kb

- Medium mutation rate: 4.5–9 mutations/kb

- High mutation rate: 9–16 mutations/kb [2]

- Product Purification: Use E.Z.N.A. Gel Extraction Kit according to manufacturer protocols [2]

Step 2: Vector Ligation and Transformation

- Restriction Digestion: Purified PCR products digested with XhoI and XbaI restriction enzymes [2]

- Ligation: Clone into pBBR1MCS-tet expression vector containing PDC promoter and terminator elements [2]

- Electroporation: Transform ligated plasmids into Z. mobilis ZM4 host strain [2]

- Selection Plate: Plate on RM-agar medium containing 5 μg/ml tetracycline; incubate 4–5 days [2]

Phenotypic Selection Phase

Step 3: Enrichment Screening

- Culture Conditions: Inoculate transformants in 5 ml RM medium at 30°C without shaking [2]

- Sequential Selection: Transfer 1% of overnight culture into fresh RM medium with incrementally increasing ethanol concentrations:

- Primary screening: 7% (v/v) ethanol for 24 hours

- Secondary screening: 8% (v/v) ethanol for 24 hours

- Tertiary screening: 9% (v/v) ethanol for 24 hours [2]

- Isolation: After three selection rounds, spread cells on RM-agar plates with 5 μg/ml tetracycline and 9% ethanol stress [2]

- Sequence Verification: Extract plasmids from individual colonies and identify mutations through DNA sequencing [2]

Validation Phase

Step 4: Growth Phenotyping

- Bioscreen Analysis: Cultivate mutant and control strains in Bioscreen C system [2]

- Conditions: 300 μl working volume in RM medium with ethanol concentrations (0%, 6%, 8%, 10% v/v) [2]

- Monitoring: Measure OD₆₀₀ at 1-hour intervals for 48 hours at 30°C with 60-second shaking before each measurement [2]

Step 5: Metabolic Characterization

- Glucose Utilization: Inoculate mid-log phase cells into fresh RM medium with 50 g/l glucose and 9% ethanol stress [2]

- Ethanol Production: Monitor ethanol accumulation during 30–54 hour fermentation period [2]

- Enzyme Assays: Measure pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC) and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) activities at 24 and 48 hours [2]

- Gene Expression: Perform quantitative real-time PCR analysis of key metabolic genes (pdc, adh) after 6 and 24 hours of stress [2]

Quantitative Performance Data

Comparative Growth and Metabolic Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of engineered Z. mobilis strains under ethanol stress

| Parameter | Control Strain ZM4 | Mutant Strain ZM4-mrpoD4 | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate with 9% Ethanol | Baseline | Significantly enhanced [2] | >1.5× [2] |

| Glucose Consumption Rate (9% ethanol) | 1.39 g Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ [2] | 1.77 g Lâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ [2] | 1.27× |

| Residual Glucose After 54h | 5.43% initial [2] | 0.64% initial [2] | 8.5× reduction |

| Net Ethanol Production (30-54h) | 6.6-7.7 g/L [2] | 13.0-14.1 g/L [2] | ~1.9× |

| Pyruvate Decarboxylase Activity (24h) | 23.93 U/g [2] | 62.23 U/g [2] | 2.6× |

| Pyruvate Decarboxylase Activity (48h) | 42.76 U/g [2] | 68.42 U/g [2] | 1.6× |

| Alcohol Dehydrogenase Activity (24h) | Baseline [2] | ~1.4× increase [2] | 1.4× |

| pdc Gene Expression (6h stress) | Baseline [2] | 9.0-fold increase [2] | 9.0× |

| pdc Gene Expression (24h stress) | Baseline [2] | 12.7-fold increase [2] | 12.7× |

Application Spectrum and Performance Benchmarks

Table 2: gTME applications across microbial hosts and phenotypic targets

| Host Organism | Engineering Target | Phenotypic Improvement | Performance Advantage Over Traditional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zymomonas mobilis | RpoD (σâ·â°) [2] | Ethanol tolerance and production [2] | Superior glucose consumption and ethanol yield [2] |

| Escherichia coli | Sigma factors [1] | Metabolite overproduction [1] | Faster optimization of complex phenotypes [1] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | TATA-binding protein [1] | Multiple stress tolerance [1] | Simultaneous improvement of multiple traits [1] |

| Various Microbes | Global transcription machinery [1] | Ethanol tolerance, metabolite production [1] | Quicker and more effective phenotype optimization [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Critical Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for implementing gTME protocols

| Reagent/Resource | Specification | Function in gTME Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | 180 ng rpoD gene [2] | Target for random mutagenesis via error-prone PCR |

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit [2] | Introduces random mutations at controlled rates |

| Expression Vector | pBBR1MCS-tet with PDC promoter/terminator [2] | Plasmid backbone for mutant sigma factor expression |

| Restriction Enzymes | XhoI and XbaI [2] | Digest PCR products for directional cloning |

| Ligation Enzyme | T4 DNA Ligase [2] | Ligates mutated genes into expression vector |

| Host Strain | Zymomonas mobilis ZM4 [2] | Microbial host for mutant library expression |

| Selection Antibiotic | Tetracycline (5 μg/ml) [2] | Selective pressure for plasmid maintenance |

| Growth Medium | RM medium with glucose [2] | Standardized medium for phenotypic selection |

| Selection Stress | Ethanol (7-10% v/v) [2] | Applied stress for enrichment of improved phenotypes |

| DNA Purification Kit | E.Z.N.A. Gel Extraction and Plasmid Kits [2] | Purification of DNA fragments and plasmids |

| ABT-255 free base | ABT-255 free base, CAS:181141-52-6; 186293-38-9, MF:C21H24FN3O3, MW:385.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AZ-27 | AZ-27, MF:C36H35N5O4S, MW:633.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Molecular Mechanisms and Pathway Analysis

gTME-Induced Metabolic Reprogramming

The enhanced ethanol tolerance in Z. mobilis through RpoD engineering demonstrates the profound metabolic reprogramming achievable through gTME. The molecular mechanism involves:

Transcriptional Amplification of Core Metabolic Pathways Mutant sigma factors exhibit altered promoter recognition that preferentially upregulates key enzymes in the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway [2]. The significant enhancement of pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC) activity—increasing 2.6-fold at 24 hours and 1.6-fold at 48 hours—demonstrates targeted amplification of the core ethanol production pathway [2]. Similarly, alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) activity shows consistent elevation (1.4× at 24h, 1.3× at 48h) under ethanol stress conditions [2].

Coordinated Stress Response Network The dramatic upregulation of pdc gene expression (9.0-fold at 6h, 12.7-fold at 24h) indicates that gTME creates a coordinated stress response that maintains metabolic flux under conditions that typically inhibit wild-type strains [2]. This suggests that mutant sigma factors rewire the transcriptional network to maintain energy production and redox balance during ethanol stress.

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic pathways enhanced through gTME in Z. mobilis:

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering represents a powerful methodology for addressing complex phenotypic optimization challenges in metabolic engineering. By targeting the global transcription apparatus, gTME enables coordinated reprogramming of multiple cellular pathways simultaneously, overcoming limitations of single-gene approaches. The documented success in enhancing ethanol tolerance and production in Z. mobilis through RpoD mutagenesis demonstrates the practical utility of this approach, with significant improvements in key metabolic enzymes and stress tolerance mechanisms. The structured protocols, quantitative performance metrics, and essential reagent guidelines provided herein offer researchers a comprehensive framework for implementing gTME strategies in diverse microbial hosts for industrial biotechnology applications.

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. Instead of targeting individual genes, gTME aims to reprogram cellular phenotypes by modifying global transcription factors, thereby altering the expression of broad regulons. This approach is particularly powerful for complex, multigenic traits such as stress tolerance, where traditional methods fall short. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for the engineering of two central transcription components: the TATA-binding protein (TBP) from eukaryotes/archaea and the bacterial alternative sigma factor RpoS (σS). We outline their core structures and functions, present validated experimental workflows for their engineering, and provide a toolkit for researchers aiming to develop microbial strains with enhanced industrial capabilities or to explore novel therapeutic targets. The methodologies described herein are framed within the context of a broader gTME research thesis, emphasizing scalable and applicable protocols for drug development and industrial biotechnology.

Transcription factors are master regulators of gene expression, and among them, TBP and RpoS serve as foundational, global controllers of transcriptional networks. Engineering these proteins allows for the simultaneous optimization of numerous downstream pathways.

TATA-Binding Protein (TBP): TBP is a universal transcription factor required for transcription initiation by all three RNA polymerases (Pol I, II, and III) in eukaryotes and archaea [3] [4]. It functions as the central core of the pre-initiation complex, recognizing and binding the TATA box sequence in gene promoters. Its binding induces a dramatic 80° bend in the DNA, facilitating strand separation and the recruitment of additional general transcription factors and RNA polymerase [3] [5]. TBP is not a solitary actor; it is part of a larger family of TBP-related factors (TRFs/TBPLs) that have evolved to regulate specific transcriptional programs, adding a layer of complexity to its engineering [4] [6].

Sigma Factor RpoS (σS): In bacteria, particularly in E. coli and other proteobacteria, RpoS is the master regulator of the general stress response [7] [8] [9]. This alternative sigma factor directs RNA polymerase to the promoters of nearly 10% of all genes in the E. coli genome, enabling the cell to survive diverse stresses such as nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress, and acid shock [8] [9]. RpoS levels are tightly controlled at transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels, allowing for a rapid and metabolically costly adaptive response [7] [8]. Its engineering can lead to strains with superior resilience in industrial fermentation processes.

Table 1: Core Functional Properties of TBP and RpoS

| Feature | TBP (Eukaryotes/Archaea) | RpoS (Bacteria) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Core component of all three RNA polymerase pre-initiation complexes [3] | Master regulator of the general stress response [8] [9] |

| DNA Recognition | Binds and bends the TATA box (e.g., T-A-T-A-a/t-A-a/t) [3] [5] | Directs RNA polymerase to specific stress-responsive promoters [7] |

| Regulon Size | Critical for transcription of a vast but variable number of promoters [3] | Controls ~500 genes (~10% of the E. coli genome) [8] |

| Key Structural Feature | Saddle-shaped protein with two symmetrical repeats [3] [6] | Structurally related to RpoD (σ70), but lacks the large N-terminal 1.1 region [7] |

| Level of Regulation | Interaction with numerous transcription factors (TFIIA, TFIIB, NC2, etc.) [3] [4] | Multi-level: transcription, translation, and protein stability [8] |

Structural and Functional Analysis

A deep understanding of the structure-function relationship is a prerequisite for the rational engineering of TBP and RpoS.

TBP: Architecture and DNA Binding

The C-terminal core of TBP, which is highly conserved, forms a saddle-like structure that straddles the DNA double helix [3] [4]. This domain contains two direct repeats that exhibit structural symmetry but have undergone significant sequence asymmetry through evolution, enabling diverse protein interactions [6]. The molecular mechanism of DNA binding is exceptional: TBP does not simply contact the DNA; it actively distorts the minor groove by inserting key phenylalanine residues, which kinks the DNA and facilitates the melting of strands necessary for transcription initiation [5]. This interaction is stabilized by a series of positively charged lysine and arginine residues that contact the DNA backbone [5]. The N-terminal region of TBP is more variable and can modulate DNA-binding activity; notably, an expansion of the polyglutamine tract in this region is associated with the neurodegenerative disorder spinocerebellar ataxia 17 [3].

RpoS: Evolution and Multi-Level Regulation

RpoS is believed to have evolved from a gene duplication event of the housekeeping sigma factor RpoD (σ70) prior to the emergence of Proteobacteria [7]. Unlike RpoS, the RpoD protein retains a large N-terminal 1.1 region, the loss of which in RpoS was a key evolutionary innovation [7]. The regulation of RpoS is remarkably complex, allowing the integration of numerous environmental signals:

- Transcriptional Control: The rpoS gene is regulated by transcription factors like ArcA, which responds to aerobic status, and by the global nucleotide ppGpp during nutrient starvation [8].

- Translational Control: The rpoS mRNA has a long 5'-UTR that forms a stem-loop structure, inhibiting ribosome binding. Small RNAs (sRNAs) such as DsrA, RprA, and ArcZ, facilitated by the Hfq protein, bind this region to open the structure and activate translation [8] [9].

- Post-Translational Control: The cellular level of RpoS is tightly controlled by proteolysis. The adaptor protein RssB targets RpoS for degradation by the ClpXP protease, a process influenced by sensor kinases like ArcB [9].

The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory network controlling RpoS activity.

Diagram 1: Multi-level regulatory network of RpoS.

gTME Application Notes & Protocols

This section provides actionable methodologies for engineering TBP and RpoS to achieve desired global phenotypic changes.

Case Study: Engineering Ethanol Tolerance via RpoD (σ70) inZymomonas mobilis

A seminal application of gTME involved enhancing the ethanol tolerance of the biofuel-producing bacterium Zymomonas mobilis by engineering its primary sigma factor, RpoD (σ70), a homolog of RpoS in function and structure [2]. The successful protocol is outlined below.

Table 2: Key Reagents for gTME via Random Mutagenesis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit (e.g., GeneMorph II) | Introduces random mutations into the target gene at a controlled rate (e.g., 0–16 mutations/kb) [2]. | Used to create a diverse library of mutant rpoD genes. |

| Expression Vector (e.g., pBBR1MCS-tet) | A low-to-medium copy number plasmid for expressing the mutant gene in the host. | Harbors the mutant rpoD library under a constitutive promoter. |

| Electroporation System | Method for high-efficiency transformation of DNA libraries into bacterial cells. | Used to introduce the mutant plasmid library into Z. mobilis. |

| Bioscreen C System | Automated microbial growth curve analyzer. | Enables high-throughput monitoring of growth under selective pressure. |

| Enrichment Screening | Sequential application of stress to selectively enrich for fit mutants from a population. | Culturing transformants in progressively higher ethanol concentrations (7% → 9%). |

Experimental Workflow:

Library Construction:

- Amplify the rpoD gene from Z. mobilis ZM4 using error-prone PCR. Vary the initial template concentration to generate libraries with low, medium, and high mutation frequencies [2].

- Digest the PCR product and the pBBR1MCS-tet vector with appropriate restriction enzymes (e.g., XhoI and XbaI).

- Ligate the mutated rpoD fragments into the vector, which contains a constitutive promoter (e.g., PDC promoter) and a tetracycline resistance marker.

- Transform the ligation product into E. coli DH5α for library amplification and plasmid preparation.

Transformation and Selection:

- Introduce the plasmid library into Z. mobilis ZM4 via electroporation.

- Plate the transformants on solid RM-agar plates with tetracycline and incubate for 4-5 days to create the initial library.

- For phenotype selection, perform sequential enrichment in liquid RM medium with increasing concentrations of ethanol (7%, 8%, and finally 9% (v/v)). Incubate for ~24 hours at 30°C at each stage [2].

- After three rounds of selection, plate cells on solid medium containing both tetracycline and 9% ethanol. Pick individual colonies for validation.

Validation and Characterization:

- Isolate plasmids from selected mutants and sequence the rpoD gene to identify mutations.

- Rebuild the mutant plasmid with the identified mutations and transform it into a fresh Z. mobilis wild-type strain to confirm that the phenotype is linked to the rpoD mutation.

- Profile growth of the validated mutant (e.g., ZM4-mrpoD4) and control strains in media with 0%, 6%, 8%, and 10% ethanol using a Bioscreen C system.

- Quantify physiological improvements: measure glucose consumption rate, net ethanol production, and key enzymatic activities (e.g., pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase) under stress conditions [2].

The workflow for this gTME protocol is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: gTME workflow for enhancing ethanol tolerance.

Engineering TBP: Rational and Evolutionary Strategies

While the above protocol focuses on random mutagenesis, engineering a complex protein like TBP often benefits from a combination of rational design and directed evolution.

Rational Design Based on Molecular Signatures: Comprehensive evolutionary analyses have identified key "molecular signature" residues in TBP that are critical for its diverse interactions [6]. For example, a universally conserved phenylalanine at a specific loop position (L5.1) is crucial for DNA binding and distortion. When designing TBP variants, targeting these signature positions through site-saturation mutagenesis allows for focused exploration of functional space. Co-crystal structures of TBP with its partners (TFIIA, TFIIB, NC2, etc.) provide a blueprint for designing mutations that selectively enhance or disrupt specific interactions to tailor transcriptional programs [4] [5] [6].

Directed Evolution for Altered Promoter Specificity: A random mutagenesis approach, similar to the RpoD protocol, can be applied to TBP. The goal would be to select for mutants that confer a desired phenotype (e.g., resistance to a metabolite, improved growth yield) or that activate synthetic promoters with altered TATA-box sequences. Selection can be performed in a yeast system where the native TBP is essential, and the mutant TBP is expressed from a plasmid under conditional control. Survivors under selective pressure would harbor TBP variants with altered functions.

Computational & Design Tools

The integration of computational tools is accelerating the engineering of transcription factors.

- Sequence Analysis and Alignment: The availability of a common TBP-lobe numbering (CTN) system and a comprehensive reference multiple sequence alignment (RefMSA) enables the residue-level interpretation of function and the identification of evolutionarily conserved molecular determinants [6]. This resource is critical for rational design.

- Structure-Based Design: High-resolution structures of TBP in complex with DNA and various partners (available in the PDB, e.g., 1ytb, 1tgh) are indispensable [5] [6]. Molecular modeling software can be used to predict the structural impact of mutations and to design new variants with desired binding properties.

- Database-Driven Prediction: Bioinformatics databases that catalog transcription factors and their binding sites can be used to predict the downstream effects of engineering TBP or RpoS, helping to anticipate global changes in the transcriptome [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Transcription Factor Engineering

| Category | Item | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning & Mutagenesis | Error-Prone PCR Kit (e.g., GeneMorph II) | Creates random mutant libraries of the target TF gene [2]. |

| Restriction Enzymes (e.g., XhoI, XbaI) | Facilitates the directional cloning of mutant genes into expression vectors [2]. | |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Ligates the insert and vector DNA. | |

| Vector Systems | Low-Copy Expression Vector (e.g., pBBR1MCS-tet) | Maintains and expresses the mutant TF gene in the host without excessive metabolic burden [2]. |

| Host Strains | E. coli DH5α | High-efficiency cloning host for library construction and plasmid propagation [2]. |

| Target Organism (e.g., Z. mobilis, S. cerevisiae) | The ultimate host for phenotypic screening and characterization. | |

| Transformation | Electroporator and Cuvettes | Enables high-efficiency transformation of plasmid DNA libraries into microbial cells [2]. |

| Screening & Selection | Selective Antibiotics (e.g., Tetracycline) | Maintains plasmid pressure during library growth and screening. |

| Chemical Stressors (e.g., Ethanol) | The selective agent for enriching mutants with improved phenotypes [2]. | |

| Analysis & Validation | Bioscreen C System or Microplate Reader | For high-throughput, quantitative analysis of growth kinetics under stress [2]. |

| Sanger Sequencing Services | Confirms the DNA sequence of isolated mutant genes. | |

| Enzyme Activity Assay Kits (e.g., for PDC, ADH) | Quantifies the physiological impact of the TF mutation on metabolic pathways [2]. | |

| LpxC-IN-13 | LpxC-IN-13, MF:C25H28N4O3, MW:432.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 11-Oxomogroside II A1 | 11-Oxomogroside II A1, MF:C42H70O14, MW:799.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The engineering of global transcription factors like TBP and RpoS through gTME provides a powerful, systems-level strategy for strain improvement and biological inquiry. The protocols detailed in this document, from the random mutagenesis of RpoD to the rational design of TBP, offer a roadmap for researchers to alter complex cellular phenotypes. By leveraging the provided experimental workflows, computational insights, and reagent toolkit, scientists can harness gTME to develop robust microbial cell factories for biomanufacturing and explore novel interventions in therapeutic contexts. The continued refinement of these protocols will undoubtedly expand the frontiers of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

Transcriptional Regulatory Networks (TRNs) are complex systems that define cell-type- or cell-state-specific gene expression from an identical DNA sequence. These networks are primarily responsible for interpreting cellular genotype into phenotypic outcomes, dynamically controlling cellular identity, function, and response to stimuli [11] [12]. Global perturbation refers to the systematic alteration of these networks through genetic, environmental, or synthetic means to redirect transcriptional programs and achieve desired cellular states. Within Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME), these perturbations represent powerful tools for reprogramming cell fate, modeling disease, and engineering novel cellular functions [13] [12].

The core principle underlying network perturbation is that transcriptional networks demonstrate biased phenotypic variability—certain transcriptional variants emerge more frequently than others in response to different perturbations. Research in E. coli has demonstrated that genes displaying high transcriptional variability in response to environmental perturbations also show heightened sensitivity to genetic perturbations, suggesting that gene regulatory networks channel both environmental and genetic influences toward common transcriptional outcomes [14]. This shared susceptibility provides the mechanistic foundation for redirecting cellular identity through targeted network perturbations.

Key Mechanistic Principles of Network Perturbation

Pioneer Factors as Chromatin Gatekeepers

A critical mechanism in transcriptional redirection involves pioneer transcription factors, a specialized class of factors capable of engaging target sites on nucleosomal DNA in "closed" chromatin that is inaccessible to most transcription factors. Pioneer factors initiate reprogramming events by binding to developmentally silenced genes and enabling subsequent chromatin opening and binding of secondary factors [15]. Key pioneer factors include Oct3/4, Sox2, and Klf4, which play essential roles in reprogramming fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [15]. These factors demonstrate the remarkable ability to scan the genome promiscuously during initial reprogramming stages, with subsequent reorganization establishing stable pluripotent states [15].

Barriers to Reprogramming and Fate Stabilization

Differentiated cells employ robust barrier mechanisms that oppose reprogramming and maintain cell fate stability. A conserved set of four transcription factors (ATF7IP, JUNB, SP7, and ZNF207 - collectively termed AJSZ) has been identified that robustly opposes cell fate reprogramming in lineage- and cell-type-independent manners [16]. Mechanistically, AJSZ maintains chromatin enriched for reprogramming TF motifs in a closed state while simultaneously downregulating genes required for reprogramming. Knockdown of these barrier factors significantly enhances reprogramming efficiency—up to six-fold in mouse embryonic fibroblasts—highlighting their critical role in maintaining transcriptional network stability [16].

Network Architecture and Transcriptional Variability

The architecture of transcriptional networks themselves dictates response patterns to perturbation. Genes regulated by global transcriptional regulators exhibit greater transcriptional variability compared to those regulated by other factors. In E. coli, 13 global transcriptional regulators have been identified that orchestrate coordinated transcriptional changes in their target genes, contributing to predominant directionality of transcriptomic shifts across different perturbations [14]. This demonstrates that network position influences susceptibility to perturbation, with hub genes controlling coordinated transcriptional responses.

Table 1: Key Molecular Players in Transcriptional Network Perturbation

| Molecular Player | Type | Function in Perturbation | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 | Pioneer Factors | Initiate reprogramming by binding closed chromatin, enabling subsequent factor binding | iPSC reprogramming [15] |

| c-Myc | Non-pioneer Factor | Binds open chromatin sites, but can access closed chromatin with pioneer factors | iPSC reprogramming [15] |

| AJSZ (ATF7IP, JUNB, SP7, ZNF207) | Barrier Factors | Maintain chromatin in closed state at reprogramming sites, repress reprogramming genes | Cardiac, neural, iPSC reprogramming [16] |

| Zelda (Zld) | Pioneer Factor | Increases DNA accessibility, facilitates binding of other transcription factors | Zygotic genome activation in Drosophila [15] |

| Global Regulators | Network Hubs | Orchestrate coordinated transcriptional changes across multiple target genes | E. coli transcriptional variability [14] |

Computational Approaches for Mapping Perturbation Effects

Network Inference from Transcriptional Profiles

ProTINA (Protein Target Inference by Network Analysis) is a dynamic network perturbation method that infers protein targets of compounds from gene transcriptional profiles. This approach uses cell-type-specific protein-gene regulatory models to infer network perturbations from differential gene expression data [13]. Candidate protein targets are scored based on network dysregulation, including enhancement and attenuation of transcriptional regulatory activity on downstream genes. For benchmark datasets from drug treatment studies, ProTINA achieved high sensitivity and specificity in predicting protein targets and revealing mechanisms of action [13].

Multi-Omics Integration for Regulatory Networks

Advanced computational frameworks now integrate both cis and trans regulatory mechanisms to model transcriptional regulation more accurately. The PANDA (Passing Attributes between Networks for Data Assimilation) algorithm generates gene regulatory networks by integrating multiple omics data sources, including TF binding motifs, protein-protein interaction networks, and co-expression data [17]. Models incorporating both cis and trans regulatory mechanisms demonstrate significantly improved gene expression prediction compared to cis-only models, with median Pearson correlation coefficients increasing from 0.30 to 0.42 in GM12878 cells [17]. Integration of chromatin conformation data (Hi-C) further refines these models by accounting for long-distance chromatin interactions [17].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Analyzing Transcriptional Perturbations

| Method | Approach | Application | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProTINA | Dynamic modeling of network perturbations from gene expression | Drug target identification, mechanism of action studies | High sensitivity/specificity; accounts for network context [13] |

| PANDA | Integrates motif, PPI, and co-expression networks | Gene regulatory network inference; gene expression prediction | Incorporates both cis and trans regulatory mechanisms [17] |

| Boolean Models | Logical modeling of network states | Circadian clock networks; simple dynamic modeling | Handles complexity with minimal parameters [18] |

| ODE-Based Models | Differential equation-based dynamic modeling | Circadian clock dynamics; quantitative prediction | Captures continuous dynamics and concentration effects [18] |

| PRISM Screening | Randomized CRISPR-Cas perturbation screening | Parkinson's disease model; protective gene discovery | Unbiased exploration of transcriptional network perturbations [19] |

Experimental Platforms for Implementing Global Perturbations

CRISPR-Cas Transcriptional Perturbation

The CRISPR-Cas system has emerged as a versatile platform for targeted transcriptional perturbation. By disabling the nuclease activity of Cas9 and fusing it with effector domains (crisprTFs), researchers can achieve either activation or repression of specific target genes [12] [19]. The PRISM (Perturbing Regulatory Interactions by Synthetic Modulators) platform utilizes randomized CRISPR-Cas transcription factors to globally perturb transcriptional networks in an unbiased manner [19]. In a yeast model of Parkinson's disease, PRISM identified guide RNAs that modulated transcriptional networks and protected cells from alpha-synuclein toxicity, with one gRNA outperforming previously described protective genes [19].

Artificial Transcription Factor Platforms

Artificial transcription factors (ATFs) represent a synthetic biology approach to transcriptional perturbation. ATFs are modular proteins comprising:

- DNA-binding domains (DBDs) that confer sequence specificity (zinc fingers, TALEs, or CRISPR-Cas)

- Effector domains (EDs) that activate or repress transcription

- Interaction domains (IDs) that enable cooperative binding [12]

ATFs can be designed to overcome challenges faced by natural TFs, including feedback regulation, epigenetic barriers, and dependence on partner proteins not expressed in the starting cell type [12]. Libraries of ATFs enable screening thousands of genes in parallel to identify key regulators of phenotypic outcomes without prior knowledge of relevant natural TFs or gene regulatory networks [12].

Synthetic Molecules for Transcriptional Control

Synthetic molecules offer a non-protein alternative for regulating transcription. Polyamides composed of N-methylpyrrole and N-methylimidazole repeats can bind the minor groove of DNA with high affinity and sequence specificity [12]. These synthetic TFs (Syn-TFs) allow fine-tuned control of dosage and timing without introducing genetic material, making them particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where permanent genomic alterations are undesirable [12].

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: PRISM Screening for Protective Modulators

Objective: Identify transcriptional modulators that protect against protein toxicity using randomized CRISPR-Cas perturbation.

Workflow:

- Library Construction: Generate a randomized gRNA library targeting genomic regions without sequence bias

- Vector Assembly: Clone gRNA library into crisprTF vectors (e.g., dCas9-VPR for activation, dCas9-KRAB for repression)

- Screening: Transduce target cells (yeast or mammalian) with lentiviral crisprTF library

- Selection: Apply selective pressure (e.g., alpha-synuclein expression for Parkinson's model)

- Sequencing & Analysis: Recover gRNAs from protected cells via deep sequencing; map to genomic targets

Key Considerations: Include control gRNAs with known effects; use sufficient library coverage (500x minimum); validate hits with secondary assays [19].

Protocol: ProTINA for Drug Target Identification

Objective: Infer protein targets and mechanism of action from transcriptional profiles.

Workflow:

- Data Collection: Obtain genome-wide transcriptional profiles from drug treatments (time-series or steady-state)

- Network Modeling: Construct cell-type-specific protein-gene regulatory network using prior knowledge

- Perturbation Analysis: Score candidate protein targets based on dysregulation patterns in downstream genes

- Validation: Compare top predictions with known targets; test novel predictions experimentally

Key Considerations: Network quality critically impacts performance; use benchmark datasets for validation; integrate with chemical information for improved specificity [13].

Protocol: Enhanced Reprogramming via Barrier Knockdown

Objective: Improve direct cellular reprogramming efficiency by targeting fate-stabilizing factors.

Workflow:

- Target Identification: Select barrier factors (e.g., AJSZ - ATF7IP, JUNB, SP7, ZNF207)

- Knockdown: Transfect with siRNA pools against barrier factors 24 hours prior to reprogramming factor induction

- Reprogramming: Induce expression of lineage-specific factors (e.g., MGT for cardiac, OSKM for pluripotency)

- Monitoring: Track reprogramming efficiency via fluorescent reporters and marker expression

- Validation: Assess functional maturation of reprogrammed cells (e.g., calcium handling for cardiomyocytes)

Key Considerations: Optimize siRNA timing and concentration; monitor for potential pleiotropic effects; use multiple siRNA designs to confirm on-target effects [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Transcriptional Perturbation Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Activation | dCas9-VPR, dCas9-SunTag | Targeted gene activation; transcriptional perturbation | Multiple effector domains enhance activation strength [12] [19] |

| CRISPR Repression | dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-SID4X | Targeted gene repression; network perturbation | Strong repression domains; minimal off-target effects [12] |

| Pioneer Factors | Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, FoxA | Initiate chromatin opening; cell fate reprogramming | Nucleosome binding capability; chromatin remodeling [15] |

| Barrier Factor Reagents | siAJSZ pools, shRNA vectors | Enhance reprogramming efficiency; fate stabilization study | Knockdown of ATF7IP, JUNB, SP7, ZNF207 [16] |

| Synthetic TFs | TALE-VP64, ZF-ED, Polyamides | Targeted regulation without genetic delivery | Modular design; tunable specificity; cell-penetrating [12] |

| Network Analysis Tools | ProTINA, PANDA, BDEtools | Inference of regulatory networks; perturbation modeling | Multi-omics integration; dynamic modeling capability [13] [18] [17] |

| Pneumocandin A4 | Pneumocandin A4, MF:C51H82N8O13, MW:1015.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Cycloviracin B1 | Cycloviracin B1, MF:C83H152O33, MW:1678.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Visualizing Perturbation Mechanisms: Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Core mechanism of network perturbation via pioneer factors and barrier knockdown.

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for computational and experimental perturbation studies.

Metabolic engineering has traditionally relied on static modifications, such as gene knockouts and constitutive overexpression, to rewire microbial metabolism for the efficient production of valuable chemicals [20]. While successful, these approaches often face limitations due to metabolic rigidity, imbalances in resource allocation, and the inability to respond dynamically to changing physiological conditions during fermentation [20]. This document provides a comparative overview of advanced strategies—including dynamic metabolic control, enzyme- and thermodynamic-optimized modeling, and synthetic biology tools—that address these core limitations. Framed within the context of global transcription machinery engineering (gTME) research, which aims to reprogram cellular physiology broadly, these protocols offer researchers and drug development professionals enhanced methodologies for strain development.

Comparative Analysis of Engineering Approaches

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics and characteristics of next-generation methodologies compared to traditional metabolic engineering.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Metabolic Engineering Approaches

| Engineering Approach | Key Characteristic | Reported Improvement/Performance | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Static Engineering | Constit gene overexpression, gene knockouts | Baseline | General chemical production |

| Dynamic Metabolic Control [20] | Autonomous flux adjustment via biosensors & genetic circuits | Improved Titer, Rate, Yield (TRY) metrics; Prevents metabolite toxicity | Fatty acids, aromatics, terpenes |

| ET-OptME Framework [21] | Integrates enzyme efficiency & thermodynamic constraints into genome-scale models | ≥292% increase in precision; ≥106% increase in accuracy vs. stoichiometric methods | Corynebacterium glutamicum model; Predicts intervention strategies |

| Synthetic Biology & gTME [22] | Genome-wide rewiring (e.g., CRISPR-Cas, pathway engineering) | 3-fold butanol yield increase; ~85% xylose-to-ethanol conversion; 91% biodiesel conversion efficiency | Advanced biofuels (butanol, isoprenoids, jet fuel) |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Dynamic Metabolic Control for Product Formation

This protocol outlines the design of a dynamic control system to autonomously regulate a metabolic pathway, preventing metabolite toxicity and enhancing production metrics [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Dynamic Metabolic Control

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Metabolite-Responsive Promoter/Biosensor | Acts as the sensor component; detects intracellular metabolite concentration and transduces it into a transcriptional signal. |

| Genetic Actuator (e.g., CRISPRi/a, T7 RNAP) | Receives the sensor signal and executes a control function, typically regulating target gene expression. |

| Inducible System (e.g., aTc, IPTG) | Used for initial characterization and tuning of the genetic circuit independently of the metabolic state. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (e.g., GFP, mCherry) | Serves as a proxy for real-time monitoring of circuit activity and metabolic states via flow cytometry. |

| Knock-in Homology Arms | Enables stable genomic integration of the biosensor circuit at a specific locus. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sensor Selection & Characterization: Identify or engineer a transcription factor-based biosensor that responds to a key pathway intermediate or the final product. Clone the sensor's promoter element upstream of a fluorescent reporter.

- Circuit Assembly & Integration: Assemble the final genetic circuit where the sensor promoter drives the expression of the actuator, which in turn regulates the target metabolic genes. Integrate the assembled circuit into the host genome using CRISPR-Cas9 and homology-directed repair.

- Dynamic Control Validation: Cultivate the engineered strain in a bioreactor. Monitor cell growth, product titer, and fluorescent reporter signal. Compare performance against a control strain with a constitutively active pathway.

- System Tuning & Optimization: If the dynamic response is suboptimal, fine-tune circuit components. This may involve modifying promoter strength, ribosome binding sites, or transcription factor expression levels to achieve the desired metabolic flux.

The logical workflow for implementing and validating this system is as follows:

Protocol 2: Enzyme- and Thermodynamic-Optimized Modeling (ET-OptME)

The ET-OptME framework enhances the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle by integrating enzyme usage costs and thermodynamic feasibility into metabolic models, yielding more physiologically realistic intervention strategies [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ET-OptME Implementation

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A computational reconstruction of the organism's metabolism (e.g., for C. glutamicum). |

| Enzyme Kinetic Data (kcat, KM) | Catalytic constants and Michaelis constants for key enzymes, used to apply enzyme usage constraints. |

| Thermodynamic Data (ΔG°') | Standard Gibbs free energy of reactions, used to determine reaction directionality and flux constraints. |

| ET-OptME Software Algorithm | The core computational tool that layers constraints onto the GEM. |

| qPCR or Proteomics Equipment | For experimental validation of predicted enzyme expression levels and metabolic fluxes. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Model and Data Curation: Obtain a high-quality genome-scale metabolic model for your production host. Curate a dataset of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) and thermodynamic properties (ΔG°') for reactions within the model.

- Constraint Layering: Run the ET-OptME algorithm to systematically apply:

- Stoichiometric constraints: Based on the base GEM.

- Thermodynamic constraints: To eliminate flux distributions that are thermodynamically infeasible.

- Enzyme efficiency constraints: To account for the protein cost of catalysis.

- Prediction of Intervention Strategies: Use the constrained model to predict genetic modifications (e.g., gene knockouts, up/down-regulations) that maximize the flux towards the target product.

- Experimental Validation & Iteration: Implement the top-predicted interventions in the host organism. Measure product titer, rate, and yield (TRY), as well as metabolic fluxes if possible. Use the experimental results to refine the model and constraints in the next DBTL cycle.

The workflow for this model-driven approach is outlined below:

Integration with gTME Research

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) is a complementary strategy that enhances the efficacy of the advanced metabolic engineering approaches detailed above. While dynamic control and optimized modeling target specific pathways, gTME aims to reprogram global cellular physiology by engineering transcription factors or the transcription machinery itself [22]. This creates a more robust and amenable cellular chassis for implementing precise metabolic interventions. For instance, a gTME-modified host with alleviated carbon catabolite repression would be an ideal platform for implementing dynamic control systems that manage co-utilization of sugar mixtures, a common challenge in biorefinery applications [22]. Similarly, the performance gains predicted by models like ET-OptME are more readily realized in a host strain whose transcriptional network has been globally optimized for industrial resilience and production.

Historical Context and Evolution of the gTME Methodology

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) is a metabolic engineering strategy for optimizing complex cellular phenotypes by manipulating transcription factors (TFs) and their downstream transcriptional regulatory networks (TRNs) [23]. This approach enables comprehensive cellular optimization through focused perturbations of the transcriptome, allowing simultaneous engineering of multiple complex traits including stress resistance, protein expression, and growth rate [23]. The methodology represents a paradigm shift from traditional single-gene modification approaches, which are limited in their capacity to address polygenic cellular phenotypes [24].

Historical Development and Foundational Work

The conceptual foundation of gTME emerged in the mid-2000s as researchers recognized that most cellular phenotypes are affected by many genes [24]. Traditional metabolic engineering approaches relying on sequential deletion or over-expression of single genes proved inadequate for reaching global phenotype optima due to the complexity of metabolic landscapes [24]. The limitations of these "greedy search algorithms," where gene targets are sequentially identified to continuously improve phenotype, prompted investigation of alternative methods for inducing multigenic perturbations [24].

Seminal work published in 2006 demonstrated the efficacy of this approach in eukaryotic systems, showing that mutagenesis and selection of TATA-binding proteins in yeast could improve ethanol tolerance and production [24]. Simultaneously, research in bacterial systems established that engineering the components of global cellular transcription machinery (specifically, σ70 in Escherichia coli) allowed for global perturbations of the transcriptome to unlock complex phenotypes [24]. These proof-of-concept studies across three distinct phenotypes—ethanol tolerance, metabolite overproduction, and multiple simultaneous phenotypes—established that gTME could outperform traditional approaches by quickly and more effectively optimizing phenotypes [24].

Evolution of gTME Applications in Yeast Systems

Expansion toYarrowia lipolytica

The gTME approach has been successfully applied to the non-conventional yeast Yarrowia lipolytica, demonstrating its effectiveness in engineering complex, industrially relevant traits [23]. This dimorphic fungus has emerged as a valuable platform for gTME applications due to its innate capabilities for protein expression, lipid accumulation, and stress resistance [23]. Research has shown that engineering transcription factors in Y. lipolytica enables the optimization of complex phenotypes that are difficult to address through pathway-specific approaches alone [25].

The establishment of rationally designed gTME in Y. lipolytica requires linking specific transcription factors to desired phenotypes, followed by high-throughput screening under multiple conditions with well-developed culturing and analytical protocols to reveal pleiotropic effects [23]. This systematic approach has enabled researchers to map transcriptional programs for enhancing stress resistance and protein production, as evidenced by the YaliFunTome database which identifies TFs that act as "omni-boosters" of protein synthesis [25].

Transcriptional Network Engineering

Advanced gTME strategies in Y. lipolytica have evolved to include comprehensive analysis of transcription factors at transcriptional and functional levels [25]. Different profiles of transcriptional deregulation and varying impacts of overexpression (OE) or knockout (KO) on recombinant protein synthesis have been observed, revealing new engineering targets [25]. Systematic overexpression approaches for 148 putative transcription factors identified 38 TFs impacting lipid accumulation under various growth conditions, providing crucial functional annotations [25].

Inference and interrogation of coregulatory networks has further refined gTME applications, enabling identification of main regulators and cooperative relationships between them during lipid production [25]. These network-level analyses have revealed distinct stages of lipid production and enabled measurement of regulator activity through the concept of "influence" [25].

Quantitative Outcomes of gTME Applications

Table 1: Phenotypic Improvements Achieved Through gTME in Microbial Systems

| Host Organism | Target Phenotype | Engineering Approach | Key Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | Ethanol tolerance | σ70 mutant library | Enhanced growth under high ethanol concentrations | [24] |

| E. coli K12 | Lycopene overproduction | σ70 mutant library | Significant increase in lycopene production | [24] |

| S. cerevisiae | Ethanol tolerance/production | TATA-binding protein engineering | Improved tolerance and production capabilities | [24] |

| Y. lipolytica | Lipid accumulation | Overexpression of 38 impactful TFs | Enhanced lipid production under various conditions | [25] |

| Y. lipolytica | Protein expression/recombinant protein synthesis | TF engineering | Enhanced stress resistance and protein yields | [25] |

Table 2: Analytical Framework for gTME Strain Characterization

| Characterization Method | Key Parameters Assessed | Relevance to gTME Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Growth profiling | Growth rate, biomass yield, stress resistance | Identifies trade-offs between production and fitness |

| Transcriptome analysis | Differential gene expression, pathway activation | Reveals global transcriptional changes |

| Metabolite quantification | Target compound yield, byproduct formation | Quantifies metabolic flux redistribution |

| High-throughput culturing | Multiple condition performance | Identifies context-dependent TF effects |

| Proteomic analysis | Protein expression levels, stress markers | Correlates transcriptional changes with functional outputs |

Experimental Protocols for gTME Implementation

Library Construction and Screening

Mutant Library Generation Protocol:

- Target Selection: Identify and select global transcription factors (σ70 in bacteria or TATA-binding proteins in yeast) based on their central regulatory roles

- Mutagenesis: Perform error-prone PCR on the selected TF gene and upstream intergenic promoter region using conditions that yield 1-5 mutations per kilobase

- Vector Construction: Clone mutated sequences into appropriate low-copy expression vectors to minimize genetic burden

- Library Transformation: Introduce the mutant library into host strains (e.g., E. coli DH5α) containing endogenous, unmutated chromosomal copies of the target gene

- Library Quality Assessment: Verify library diversity through sequencing of random clones and ensure adequate coverage (>10^6 transformants for comprehensive coverage)

Selection and Screening Protocol:

- Primary Selection: Apply selective pressure relevant to the target phenotype (e.g., high ethanol concentrations, limiting nutrients)

- Serial Subculturing: Perform multiple rounds of growth under selective conditions to enrich for beneficial mutants

- Colony Isolation: Plate enriched cultures to isolate individual colonies (typically 20-100 colonies based on selection strength)

- Phenotypic Assay: Quantitatively assess isolated mutants for the target phenotype under controlled conditions

- Secondary Screening: Evaluate top performers in scaled-up conditions to confirm phenotypic stability

Strain Characterization and Validation

Transcriptomic Analysis Protocol:

- RNA Isolation: Extract high-quality RNA from wild-type and engineered strains under identical growth conditions

- Microarray/RNA-seq: Perform global transcriptome analysis using appropriate platforms (e.g., custom microarrays or RNA sequencing)

- Differential Expression: Identify significantly up- and down-regulated genes using appropriate statistical thresholds (e.g., fold-change >2, p-value <0.05)

- Pathway Enrichment: Analyze affected biological pathways using gene ontology and metabolic pathway databases

- Validation: Confirm key transcriptomic changes through qRT-PCR on selected target genes

Phenotypic Characterization Protocol:

- Growth Profiling: Monitor growth kinetics of engineered strains versus wild-type under permissive and selective conditions

- Metabolite Analysis: Quantify target metabolites (e.g., lycopene, lipids) using appropriate analytical methods (HPLC, GC-MS)

- Stress Resistance Assays: Evaluate performance under various stress conditions (ethanol, temperature, osmotic stress)

- Genetic Stability: Assess phenotype maintenance over multiple generations in non-selective conditions

- Comparative Analysis: Benchmark gTME strains against traditionally engineered counterparts

Visualizing gTME Workflows and Regulatory Networks

Diagram 1: Comprehensive gTME workflow from target identification to strain validation

Diagram 2: gTME mechanism of action through transcriptional network modulation

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for gTME Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function in gTME | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Error-prone PCR kit | Introduces random mutations into TF genes | Optimize mutation rate to balance diversity and function |

| Low-copy expression vectors | Maintains mutant TF genes without genetic burden | Ensures stable expression without plasmid loss |

| Specialized growth media | Applies selective pressure for phenotype optimization | Formulate to mimic industrial process conditions |

| RNA isolation kits | Extracts high-quality RNA for transcriptomic studies | Preserve RNA integrity for accurate expression analysis |

| Next-generation sequencing platforms | Characterizes mutant libraries and transcriptomes | Enables comprehensive analysis of diversity and changes |

| Microarray/RNA-seq reagents | Profiles global gene expression changes | Identifies pleiotropic effects of TF engineering |

| Analytical standards (HPLC, GC-MS) | Quantifies metabolite production | Validates metabolic engineering outcomes |

| Yarrowia lipolytica strains | Host platform for gTME applications | Leverage innate capabilities for lipid and protein production |

The evolution of gTME methodology from its initial conception to current applications in yeast and bacterial systems demonstrates its power as a metabolic engineering strategy. By enabling simultaneous optimization of multiple complex traits through targeted perturbations of transcriptional networks, gTME has overcome limitations of traditional sequential engineering approaches. The continued refinement of gTME protocols, particularly in industrially relevant hosts like Yarrowia lipolytica, promises to further enhance capabilities for engineering complex phenotypes including stress resistance, substrate utilization, and production of valuable compounds. Future developments will likely focus on integrating gTME with other metabolic engineering strategies and leveraging increasingly sophisticated computational tools to predict optimal transcription factor modifications.

A Step-by-Step gTME Protocol: From Library Construction to Phenotypic Screening

Defining Phenotypes and Selection Pressures for gTME

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) is a phenotype discovery approach that unlocks complex, multigenic traits by altering genome-wide transcription through engineered transcription factors [26]. Success hinges on precise definition of target phenotypes and corresponding selection pressures.

Table 1: Phenotype and Selection Strategy Design

| Desired Phenotype | Corresponding Selection Pressure | gTME Application Example | Key Measurable Outputs (Quantitative) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Ethanol Tolerance [26] | Incremental increases in ethanol concentration in growth medium. | S. cerevisiae strains for biofuel production. | Cell viability (%), Optical Density (OD600), Ethanol production yield (g/L). |

| Metabolite Overproduction [1] | Growth in media where the target metabolite is a primary carbon source or is required for biomass formation. | E. coli or yeast strains for industrial synthesis of chemicals. | Metabolite titer (g/L), Productivity (g/L/h), Yield (g product/g substrate). |

| Multi-Stress Resistance [26] | Combined stressors (e.g., ethanol + SDS, low pH + high temperature). | Robust industrial production strains for less refined conditions. | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), Zone of Inhibition (mm), Survival rate under stress (%). |

Core Experimental Protocol for gTME

This protocol outlines the key steps for implementing a gTME screen, using enhanced ethanol tolerance in S. cerevisiae as a template [26].

Step 1: Transcription Factor and Plasmid Library Construction

- Transcription Factor Selection: Choose a global transcription factor (e.g., TATA-binding protein or a subunit of the RNA polymerase complex). The choice influences the scope of transcriptome perturbation [26].

- Library Diversity: Create a mutant plasmid library via error-prone PCR or other random mutagenesis techniques. Aim for a library size of >10^6 unique clones to ensure sufficient functional diversity [26].

- Expression System: Clone mutagenized genes into a suitable expression vector. Using the native promoter is common, but inducible or constitutive promoters can also be tested [26].

Step 2: Strain Development and Phenotypic Diversity Assessment

- Transformation: Introduce the plasmid library into a host strain containing the native, chromosomal copy of the transcription factor. This allows for perturbation of the transcriptome without lethal effects [26].

- Check Diversity: Before selection, assess the phenotypic diversity of the untransformed host versus the library. A successful library will show a wider distribution of growth characteristics under non-selective conditions [26].

Step 3: Application of Selection Pressure

- Strategy: Plate serial dilutions of the library or use liquid culture in media containing the predetermined selection pressure (e.g., a high concentration of ethanol).

- Progression: Isolate surviving colonies. To isolate stronger phenotypes, subject positive clones to successive rounds of selection with increasing intensity of the pressure [26].

Step 4: Validation and Characterization

- Plasmid Isolation: Isolate the plasmid from phenotypically superior strains and retransform it into a fresh, naive host strain.

- Confirmation: Test the new transformants for the desired phenotype. A confirmed phenotype indicates it is linked to the plasmid-borne transcription factor variant and not a genomic mutation [26].

- Downstream Analysis: Characterize the transcriptome of validated mutants (e.g., via RNA sequencing) to understand the global expression changes conferring the new phenotype [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for gTME

| Item | Function in gTME Protocol | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenized Plasmid Library [26] | Carries the mutated transcription factor allele; source of transcriptome diversity. | Plasmid with error-prone PCR mutated SPT15 gene, cloned downstream of a constitutive promoter. |

| Host Strain [26] | Provides the native, functional copy of the transcription factor to maintain cell viability. | S. cerevisiae strain with wild-type genomic allele of the targeted transcription factor. |

| Selection Media [26] | Applies the defined pressure to screen for and isolate mutant strains with desired phenotypes. | Synthetic Complete (SC) media lacking appropriate amino acid for plasmid selection, supplemented with a defined stressor (e.g., 6% v/v ethanol). |

| Tools for Library Diversity Assessment [26] | Evaluates the phenotypic variance of the mutant library before selection to ensure quality. | Plate reader for growth curve analysis under non-selective conditions. |

| RNA Sequencing Kits | Analyzes the global transcriptomic changes in validated mutant strains compared to the wild-type. | Commercial kit for mRNA extraction, library preparation, and next-generation sequencing. |

| ROC-325 | ROC-325, MF:C28H27ClN4OS, MW:503.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BAY39-5493 | BAY39-5493, MF:C17H15ClFN3O2S, MW:379.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) is an advanced microbial engineering approach that enhances complex cellular phenotypes by reprogramming global gene regulation networks. This strategy involves the directed evolution of key transcription-related proteins, such as the TATA-binding protein in yeast, encoded by the SPT15 gene. By introducing targeted mutations into these global regulators, gTME simultaneously alters the expression of numerous downstream genes, enabling rapid optimization of industrially relevant traits like ethanol tolerance, stress resistance, and metabolic output without prior knowledge of the specific genetic determinants [27] [23].

The gTME approach is particularly valuable for overcoming challenges in industrial biotechnology, where conventional methods of modifying individual genes often prove insufficient for complex phenotypes involving multiple genes and pathways. Library construction for target genes like SPT15 enables the creation of diverse mutant populations for screening superior industrial strains, making it a powerful tool in strain development for biofuels, chemical production, and pharmaceutical development [28] [2].

Mutagenesis Strategies for SPT15

Error-Prone PCR (Ep-PCR)

Error-prone PCR is a widely adopted method for creating random mutations in target genes such as SPT15. This technique relies on altering standard PCR conditions to reduce replication fidelity, resulting in nucleotide substitutions throughout the amplified gene.

Key modifications to standard PCR protocols include:

- Manganese Ion Incorporation: Adding MnClâ‚‚ to the reaction mixture instead of standard MgClâ‚‚ significantly increases mutation rates by promoting nucleotide misincorporation [29].

- Nucleotide Imbalance: Using unequal concentrations of dNTPs creates preferential incorporation errors during DNA synthesis.

- Polymerase Selection: Utilizing DNA polymerases lacking proofreading activity (e.g., Taq polymerase) ensures mutations are preserved in the final product.

The mutation frequency can be precisely controlled by adjusting MnClâ‚‚ concentration, with research demonstrating optimal results at 0.5 mM MnClâ‚‚, typically yielding 2-10 mutations per kilobase of DNA sequence [29]. This mutation rate provides sufficient diversity while maintaining protein functionality. Following amplification, the mutated SPT15 gene is cloned into an appropriate expression vector and transformed into host cells to create a comprehensive mutant library for phenotypic screening.

CRISPR-Based Base Editing

Recent advances in CRISPR technology have enabled more precise mutagenesis approaches for SPT15. The Target-AID (Activation-Induced Cytidine Deaminase) system represents a CRISPR-based base editing platform that facilitates direct C-to-T substitutions in the yeast genome without requiring double-strand breaks or donor DNA templates [28].

The Target-AID system comprises three key components:

- Cas9 nickase (nCas9, D10A): A modified Cas9 that cleaves only one DNA strand, reducing cellular toxicity.

- PmCDA1: An activation-induced cytidine deaminase ortholog that catalyzes cytidine-to-uridine conversions.

- UGI (Uracil DNA Glycosylase Inhibitor): Prevents repair of the G:U mismatch, increasing editing efficiency.

This system enables highly efficient site-directed mutagenesis with reported efficiencies of 8.8% to 53.1% at various genomic loci, significantly higher than traditional methods [28]. The approach allows for focused mutagenesis within a 17-base editing window positioned -20 to -13 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site, enabling strategic targeting of specific SPT15 domains known to influence transcription machinery interactions.

Quantitative Comparison of Mutagenesis Approaches

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of SPT15 Mutagenesis Methods

| Parameter | Error-Prone PCR | CRISPR Base Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation Type | Random nucleotide substitutions | Targeted C-to-T conversions |

| Mutation Rate | 2-10 mutations/kb [29] | Site-specific with 8.8-53.1% efficiency [28] |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate | High |

| Equipment Requirements | Standard molecular biology lab | Advanced gene editing tools |

| Library Diversity | High (random coverage) | Medium (targeted regions) |

| Screening Throughput | High-throughput compatible | Medium-to-high throughput |

| Key Applications | Broad phenotypic improvement (e.g., 34.9% ethanol reduction [27]) | Specific protein function analysis and strain enhancement [28] |

| Primary Advantages | No prior structural knowledge needed | Precise, efficient editing with less cellular toxicity |

| Main Limitations | Potential for non-beneficial mutations | Restricted to specific nucleotide changes |

Experimental Protocol for SPT15 Mutant Library Construction

Error-Prone PCR Mutagenesis Protocol

Materials Required:

- Template DNA: SPT15 gene (723 bp) from S. cerevisiae genomic DNA

- Primers: SPT15-EcoRI-FW and SPT15-SalI-RV [29]

- PCR reagents: 10× reaction buffer, dNTPs (unequal concentrations), MnCl₂ solution, rTaq DNA polymerase

- Equipment: Thermal cycler, gel electrophoresis system, DNA purification kit

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a 50 μL PCR mixture containing:

- 1× reaction buffer

- 200 μM each dATP and dGTP

- 1 mM each dCTP and dTTP (unequal dNTP ratios enhance misincorporation)

- 0.5 mM MnClâ‚‚ (critical for mutation induction)

- 2.5 U rTaq DNA polymerase

- 10 pmol each primer

- 50 ng SPT15 template DNA

- Nuclease-free water to 50 μL

- Prepare a 50 μL PCR mixture containing:

PCR Amplification:

- Use the following thermal cycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes

- 30 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 58°C for 30 seconds [29]

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute

- Final extension: 72°C for 10 minutes

- Use the following thermal cycling conditions:

Product Analysis and Purification:

- Confirm amplification by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis

- Purify PCR product using DNA gel extraction kit

- Quantify DNA concentration by spectrophotometry

Cloning and Transformation:

- Digest purified PCR product and pYX212 vector with EcoRI and SalI restriction enzymes

- Ligate mutated SPT15 into vector using T4 DNA ligase

- Transform ligation product into E. coli JM109 competent cells for plasmid amplification

- Isolate and sequence plasmids to verify mutation rate and distribution

- Transform validated plasmids into S. cerevisiae host strain for phenotypic screening [29]

Target-AID Base Editing Protocol

Materials Required:

- Target-AID plasmid system (nCas9-PmCDA1-UGI fusion)

- SPT15-specific gRNA expression vector

- Yeast transformation reagents (lithium acetate, PEG, single-stranded carrier DNA)

- Selection media (appropriate antibiotic or auxotrophic selection)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

gRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design gRNA targeting desired SPT15 regions with 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence

- Clone gRNA sequence into appropriate expression vector under RNA polymerase III promoter

Yeast Transformation:

- Grow host yeast strain to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.8-1.0)

- Prepare transformation mix containing:

- 500 μL yeast cells

- 10 μL Target-AID plasmid DNA (500 ng)

- 10 μL gRNA plasmid DNA (500 ng)

- 50 μL lithium acetate (1 M)

- 300 μL PEG 3350 (50% w/v)

- 10 μL single-stranded carrier DNA (10 mg/mL)

- Incubate at 42°C for 40 minutes for heat shock transformation

- Plate on selective media and incubate at 30°C for 2-3 days

Mutant Screening and Validation:

- Pick individual colonies and inoculate into 96-well deep plates

- Screen under selective pressure conditions (e.g., ethanol stress, osmotic stress)

- Israte plasmid DNA from superior performers and sequence SPT15 gene to identify mutations

- Validate phenotypes by retransforming confirmed mutant plasmids into fresh host cells [28]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SPT15 Mutagenesis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Vectors | pYX212, pY16, pBBR1MCS-tet | Expression of mutant genes; contains necessary promoters (TEF1), markers (URA3, AmpR) [27] [29] [2] |

| Host Strains | S. cerevisiae YS59, Z. mobilis ZM4 | Microbial platforms for mutant library screening and phenotypic characterization [27] [2] |

| Polymerases | rTaq DNA polymerase, GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit | Error-prone PCR amplification with controlled mutation rates [29] [2] |

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, SalI, XhoI, XbaI | Vector and insert digestion for cloning mutant libraries [29] [2] |

| Selection Agents | G418, Ampicillin, Tetracycline, 5-FOA | Selection of transformants and enrichment of desired phenotypes [28] [29] |

| Culture Media | YPD, SD, RM, SOB | Strain propagation, fermentation assays, and transformation [27] [29] [2] |

Analytical Methods for Mutant Characterization

Phenotypic Screening Methods

Effective mutant characterization requires multi-faceted phenotypic screening to identify strains with improved industrial properties:

Ethanol Tolerance Assay: Grow mutant strains in media containing elevated ethanol concentrations (6-10% v/v). Monitor growth kinetics (OD600) over 48-72 hours using automated systems like Bioscreen C. Superior mutants demonstrate accelerated growth rates and higher final cell densities under stress conditions [2].

Fermentation Performance: Evaluate mutants in simulated industrial conditions using Triple M medium or YPDT fermentation medium. Key metrics include glucose consumption rate, ethanol production, and byproduct formation (glycerol, acetate). High-performing SPT15 mutants have shown 34.9% reduction in ethanol yield or 1.5-fold increases in fermentation capacity under stress [27] [28].

Stress Resistance Profiling: Subject mutants to various industrial stressors including thermal stress (elevated temperatures), hyperosmotic stress (high sugar/salt concentrations), and inhibitor tolerance (furans, phenolic compounds). Measure viability and metabolic activity under each condition [28].

Molecular Analysis Techniques

Comprehensive molecular characterization elucidates the mechanistic basis of phenotypic improvements:

RNA-Seq Transcriptomics: Isolate total RNA from mid-log phase cultures. Prepare cDNA libraries and sequence using Illumina platforms. Map reads to reference genome (S. cerevisiae S288c) and quantify gene expression using FPKM method. Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) using NOISeq method with significance threshold of fold-change ≥2 and probability ≥0.8 [27].

Metabolome Analysis: Employ LC-MS/MS to profile intracellular metabolites. Identify altered metabolic fluxes, particularly in glycolysis, glycerol production, and NAD+/NADH homeostasis pathways. These analyses reveal how SPT15 mutations rewire central carbon metabolism to redirect flux away from ethanol toward alternative endpoints [27].

Protein Structure Analysis: Model mutation effects using protein structure alignment tools. Identify mutation locations in key functional regions: N-terminal domain (DNA binding), saddle-shaped core (TATA box interaction), and convex surface (transcription factor interactions). Mutations at residues A140, P169, and R238 demonstrate particularly strong effects on stress tolerance [28].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comprehensive gTME workflow for SPT15 mutagenesis, showing parallel mutagenesis strategies and downstream analysis.

Diagram 2: Molecular mechanism of SPT15 mutations, showing how single amino acid changes propagate through the transcription machinery to influence global gene expression and cellular phenotype.

Within Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) research, the strategic introduction of diversity into host strains is a foundational step for reprogramming cellular phenotypes. This process enables the discovery of mutants with enhanced traits, such as improved stress tolerance or metabolite production. The core principle involves creating vast genetic libraries in host strains, followed by rigorous selection to identify beneficial variants. This protocol details a standardized methodology for introducing diversity through random mutagenesis and subsequent selection, providing a critical tool for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to evolve microbial strains for industrial and therapeutic applications. The methods described herein are designed to be adaptable to various bacterial and yeast systems commonly used in gTME studies.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Random Mutagenesis via Error-Prone PCR