Host-Aware Models: The New Framework for Predictive Biomanufacturing Design

This article explores the paradigm shift in metabolic engineering toward host-aware computational models.

Host-Aware Models: The New Framework for Predictive Biomanufacturing Design

Abstract

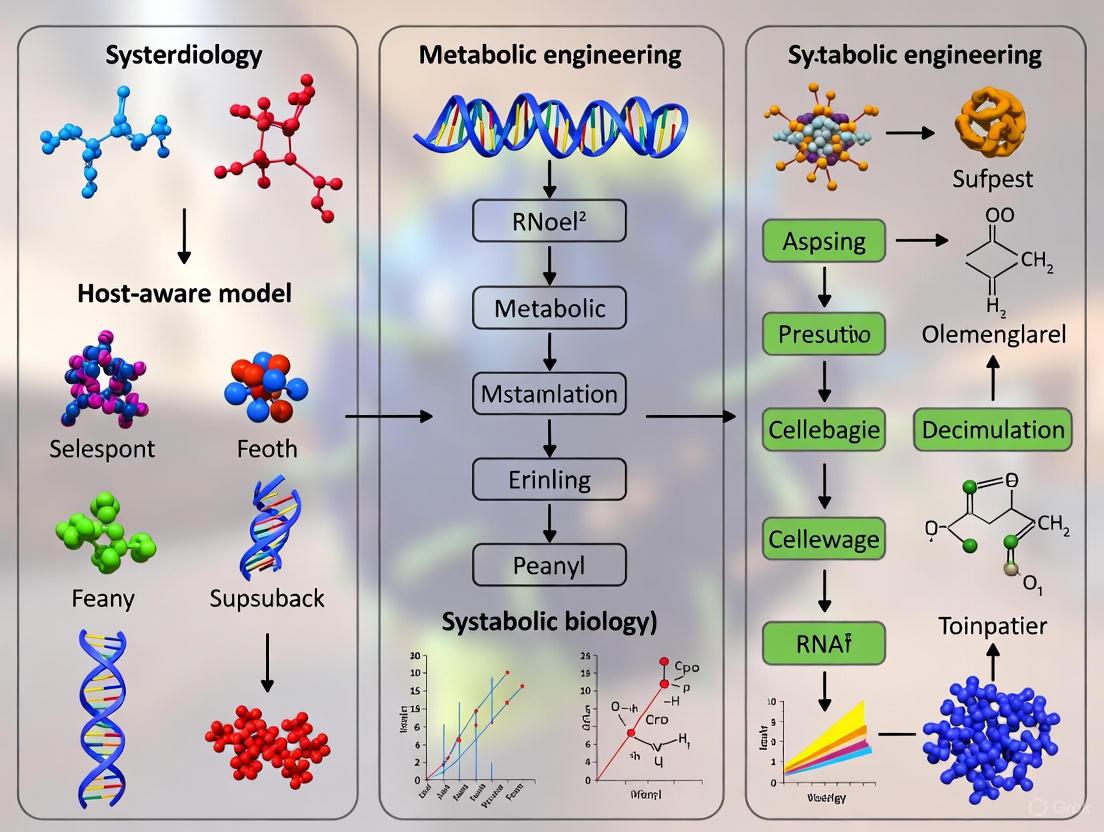

This article explores the paradigm shift in metabolic engineering toward host-aware computational models. These multi-scale frameworks move beyond traditional static optimization by integrating cell-level dynamics—including metabolism, gene expression, and resource competition—with population-level behavior in bioreactors. We detail how these models uncover design principles that maximize volumetric productivity and yield, guide the implementation of dynamic genetic circuits, and enable the strategic selection of microbial chassis. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides a roadmap for leveraging host-aware models to overcome the fundamental growth-production trade-off, thereby facilitating the construction of more efficient, reliable, and scalable microbial cell factories for therapeutic and chemical production.

Beyond Static Optimization: How Host-Aware Models Rethink the Growth-Production Trade-Off

The engineering of microbial cell factories for chemical production represents a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, promising sustainable routes to pharmaceuticals, fuels, and specialty chemicals [1] [2]. However, this promise is constrained by a fundamental biological dilemma: the inherent competition between cellular growth and product synthesis. When cells are engineered with heterologous pathways, these synthetic constructs compete with native processes for finite cellular resources, including precursors, energy (ATP), cofactors, and the gene expression machinery (RNA polymerases and ribosomes) [3]. This reallocation of resources creates a "metabolic burden," which manifests as impaired cell growth, reduced genetic stability, and suboptimal product yields [3] [4].

Understanding and managing this resource competition is critical for constructing efficient microbial cell factories. The emerging paradigm of host-aware synthetic biology moves beyond simple pathway insertion to consider the complex interactions between synthetic constructs and their host organisms [3]. By using multi-scale models that capture both cell-level and population-level dynamics, researchers can now predict how engineering decisions affect overall system performance, leading to novel design principles that maximize bioproduction [1] [2]. This whitepaper examines the core principles of resource competition and outlines strategic solutions for optimizing microbial factories, framed within the context of host-aware model frameworks.

Quantitative Analysis of the Growth-Production Trade-off

Competition for shared cellular resources creates an inherent trade-off between microbial growth and product synthesis. A computational host-aware framework analyzing this relationship revealed that maximum volumetric productivity in batch cultures is not achieved by maximizing either growth or synthesis rates individually [1]. Instead, optimal performance requires a carefully balanced intermediate state.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Engineered Strains Across the Growth-Synthesis Spectrum

| Strain Type | Specific Growth Rate (minâ»Â¹) | Specific Synthesis Rate | Volumetric Productivity | Product Yield | Key Engineering Principle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Growth-High Synthesis | Low (e.g., 0.01) | High | Low | High | High expression of synthesis enzymes (Ep, Tp); Low expression of host enzyme (E) [1] |

| Medium Growth-Medium Synthesis | Medium (e.g., 0.019) | Medium | Maximum | Medium | Balanced expression of host and heterologous enzymes [1] [2] |

| High Growth-Low Synthesis | High (e.g., 0.03) | Low | Low | Low | High expression of host enzyme (E); Low expression of synthesis enzymes (Ep, Tp) [1] |

The data indicates that strains with very high growth rates consume most substrates for biomass rather than product, while strains with too low growth rates produce smaller populations that take longer to accumulate product [1]. The optimal sacrifice in growth rate (approximately 0.019 minâ»Â¹ in the model) is necessary to achieve maximum volumetric productivity, which is a key culture-level performance metric directly linked to capital investments in production plants [1].

Computational Methodologies for Host-Aware Modeling

Multi-Scale Mechanistic Modeling

The host-aware computational framework involves a multi-scale model that integrates single-cell dynamics with population-level behavior in batch culture [1]:

Single-Cell Model Components:

- Cell growth dynamics

- Simplified metabolism with branch points between native and heterologous pathways

- Host enzyme and ribosome biosynthesis

- Heterologous gene expression and product synthesis

- Competition for transcriptional and translational resources

Population-Level Model Components:

- Population growth dynamics

- Nutrient consumption kinetics

- Product accumulation in batch culture

Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Volumetric productivity (product per unit reactor volume per unit time)

- Product yield (substrate converted to product)

- Specific growth and synthesis rates

Multiobjective Optimization Framework

The optimal engineering of strains can be formulated as a multiobjective optimization problem [1]:

Design Variables: Transcription rate scaling coefficients for host enzyme (sTXE) and synthesis pathway enzymes (sTXEp, sTXTp)

Objective Functions:

- Pareto optimization of growth rate (λ) and synthesis rate (rTp)

- Direct optimization of volumetric productivity and product yield

Algorithm Implementation:

- Exploration of Pareto fronts exhibiting trade-offs between objectives

- Identification of optimal scaling values for enzyme expression

- Validation through batch culture simulations

Experimental Strategies for Burden Mitigation

Dynamic Genetic Circuit Design

Static optimization approaches often prove suboptimal because the ideal state for cell proliferation rarely aligns with the ideal state for chemical production [2]. Dynamic control strategies decouple growth and production phases through engineered genetic circuits:

The most effective genetic circuits for two-stage production actively inhibit host native metabolic enzymes upon induction, effectively re-routing cellular resources from growth to product synthesis [1] [2]. Surprisingly, simplified circuits that suppress host metabolism without directly activating production enzymes can perform nearly as well as more complex designs, offering more robust engineering solutions [2].

Host and Vector Selection Criteria

Choosing an appropriate host organism is a critical step in minimizing resource competition:

Table 2: Host Organism Selection Guide for Heterologous Pathway Expression

| Host Organism | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Extensive genetic tools; Rapid growth; Well-characterized physiology [3] | Limited post-translational modifications; Potential toxicity issues [5] | Non-complex proteins; Natural product synthesis from central metabolites [1] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Eukaryotic protein processing; GRAS status; Robust genetic tools [5] | Hyperglycosylation potential; Tough cell wall [5] | Eukaryotic enzymes requiring post-translational modifications (e.g., P450 systems) [5] |

| Pichia pastoris | Strong inducible promoters; High protein expression; GRAS status [5] | Methanol requirement for some promoters [5] | High-level protein production; Metabolic engineering with regulated expression [5] |

| Filamentous Fungi | Rich secondary metabolism; Secretion capability [5] | Complex genetics; Competing native pathways [5] | Secondary metabolite production; Natural product diversification [5] |

| Plant Systems | Appropriate compartmentalization; Self-sufficiency [5] | Slow growth; Complex transformation [5] | Plant-specific natural products requiring specialized organelles [5] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Burden Engineering

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Investigating Resource Competition

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Parts for Expression Tuning | Promoters of varying strengths; RBS libraries; Terminators [1] [5] | Fine-control of enzyme expression levels to balance resource allocation [1] |

| Burden-Responsive Parts | Stress-responsive promoters (e.g., σ32-mediated); Metabolic biosensors [3] | Dynamic regulation based on cellular state; Feedback control of synthetic constructs [3] |

| Modeling & Computational Tools | Host-aware modeling frameworks; Constrained allocation models; Pareto optimization algorithms [1] | Prediction of host-construct interactions; Identification of optimal engineering strategies [1] |

| Vectors for Pathway Assembly | Modular cloning systems (e.g., Golden Gate); Multi-copy and integration vectors [5] | Stable maintenance of heterologous pathways; Control of gene copy number and expression [5] |

| Metabolic Analysis Tools | Constrained metabolic models; Cofactor balancing tools; Flux analysis software [4] | Analysis of metabolic flux distribution; Identification of bottleneck reactions [4] |

Advanced Engineering Solutions

Resource Allocation Control Systems

Engineering solutions that explicitly manage resource allocation include:

Orthogonal Ribosomes: Create separate translation systems for heterologous genes to minimize competition with native genes [3].

Burden-Responsive Controllers: Implement feedback systems that downregulate synthetic constructs when burden exceeds optimal thresholds [3].

Metabolic Valve Controllers: Dynamically control flux distribution at key metabolic branch points through targeted enzyme inhibition [1] [2].

Context-Dependent Strategies

The optimal engineering approach depends on the relationship between the target product and host metabolism:

Products Competing with Protein Translation: When chemicals are synthesized from precursors essential for protein translation (e.g., amino acids), the optimal strategy shifts toward repressing the production pathway during growth phase to preserve vital building blocks [2].

Energy-Dense Products: For products requiring substantial ATP or cofactors, engineering ATP regeneration systems or balancing redox cofactors becomes critical [4].

Toxic Intermediates: Pathways with toxic intermediates benefit from spatial organization (enzyme complexes) or temporal separation through dynamic control [3].

The fundamental challenge of resource competition between native metabolism and heterologous pathways necessitates a paradigm shift from static to dynamic engineering approaches. Host-aware modeling frameworks provide the predictive capability to design strains that optimally balance growth and production, either through static intermediate states or sophisticated dynamic control systems. The design principles emerging from these models—particularly the strategic inhibition of host metabolism and context-dependent resource allocation—enable the construction of microbial cell factories with significantly enhanced performance. As the field advances, integrating these host-aware principles with high-throughput automated engineering platforms will be crucial for realizing the full potential of microbial biomanufacturing.

In the competitive and costly landscape of biopharmaceutical manufacturing, selecting the correct metrics to guide process development is not merely an academic exercise—it is a critical business decision with profound economic implications. Traditional measures such as titre and specific rates provide valuable cell-level information but fall short in capturing the overall efficiency and cost-effectiveness of a production culture. This whitepaper, framed within the context of host-aware model for biomanufacturing design principles, argues that volumetric productivity and product yield are the paramount culture-level performance metrics for optimizing microbial and mammalian cell factories. We demonstrate how a host-aware computational framework, which accounts for competition for native cellular resources, reveals design principles that maximize these key performance indicators (KPIs). Furthermore, we present experimental protocols and modeling approaches that enable researchers to transition from strain selection based on simple growth and synthesis rates to a more holistic strategy that ensures superior performance at the production scale.

The biopharmaceutical industry faces mounting pressure to reduce the manufacturing costs of biologic drugs, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), vaccines, and cell/gene therapy products. Despite their therapeutic success, production remains expensive, impacting market accessibility and value-based healthcare decisions [6]. While cell line engineering and process optimization have steadily increased product titres, a high final concentration does not necessarily equate to a cost-efficient process.

A host-aware modeling framework posits that engineered production is affected by competition for the host's finite native resources, both metabolic and gene expression-related [1]. This competition creates a fundamental trade-off: engineering a cell for high synthesis rates often attenuates its growth. Therefore, selecting a production strain based solely on its specific productivity or growth rate can be misleading, as it ignores the dynamics of the entire batch culture.

Volumetric productivity specifies how much product is made per unit of reactor volume per unit of time. This metric is directly linked to capital investment, as higher productivity allows for meeting market demand with smaller, more affordable bioreactors [1] [7]. Product yield measures the efficiency of converting consumed substrates into the desired product, minimizing raw material wastage and operational costs [1]. In contrast, titre (the final product concentration) ignores the time factor, and specific rates (e.g., per cell) do not reflect the total output of the culture system. This paper details why a shift in focus to volumetric productivity and yield is essential for the design of economically viable bioprocesses.

Defining the Key Performance Indicators

Volumetric Productivity

Volumetric productivity is a rate metric that quantifies the output of the entire bioprocess system. It is defined as the total amount of product formed divided by the bioreactor working volume and the total process time.

[ \text{Volumetric Productivity} = \frac{\text{Total Product Amount}}{\text{Bioreactor Working Volume} \times \text{Total Process Time}} ]

Importance: It is a direct determinant of the production plant's output capacity. Maximizing volumetric productivity minimizes the required reactor size for a given annual output, thereby significantly reducing capital expenditure [1] [7].

Product Yield

Yield is an efficiency metric that evaluates the conversion of a key substrate (e.g., glucose) into the product.

[ \text{Product Yield} = \frac{\text{Total Product Amount}}{\text{Total Substrate Consumed}} ]

Importance: A high yield indicates minimal waste of often expensive raw materials, directly lowering the cost of goods sold (COGS) and making the process more sustainable [1].

The Shortcomings of Titre and Specific Rates

- Titre: While a high final product concentration can simplify downstream processing, it does not account for how long it took to achieve that concentration. A process with a high titre but a long duration may be less productive than a process with a moderate titre and a short cycle time.

- Specific Rates: Metrics like the specific growth rate (μ) or specific production rate (qP) are intrinsic properties of the cell at a given point in time. They are useful for understanding cell physiology but are agnostic to the final cell density achieved in the bioreactor. A culture of highly productive cells that fail to reach a high density will have a low overall output.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Bioprocess Performance Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Primary Significance | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Productivity | Product mass / (Reactor Volume × Time) | Capital Cost Driver; defines output capacity per unit time. | Does not account for substrate consumption efficiency. |

| Product Yield | Product mass / Substrate mass consumed | Operational Cost Driver; measures conversion efficiency. | Does not account for process time or rate. |

| Titre | Product mass / Reactor Volume | Downstream Impact; final product concentration. | Ignores the time factor required to achieve that concentration. |

| Specific Production Rate (qP) | Product mass / (Cell mass × Time) | Cell Physiology; intrinsic productivity of a cell. | Agnostic to the final cell density achieved in the culture. |

Host-Aware Modeling: Unveiling Design Principles for Culture-Level Performance

Computational host-aware models that integrate intracellular resource allocation with population-level dynamics are powerful tools for identifying optimal strain design strategies. These models capture the competition for metabolic precursors and gene expression machinery (e.g., ribosomes) between native host functions and introduced heterologous pathways [1].

The Fundamental Growth-Synthesis Trade-Off

Multi-objective optimization using host-aware models consistently reveals a Pareto front between specific growth rate (λ) and specific synthesis rate (rTp). This means that for a given system, it is impossible to engineer a strain that simultaneously achieves maximum growth and maximum production; a trade-off must be made [1].

Crucially, the strains on this Pareto front exhibit a wide range of performances when evaluated at the culture-level.

- High Growth-Low Synthesis Strains: Consume most of the substrate for biomass, resulting in a large population but low product yield.

- Low Growth-High Synthesis Strains: Achieve high yield but can have low volumetric productivity because the smaller population takes longer to produce the same amount of product.

- Optimal Strain: The strain that achieves maximum volumetric productivity is found at an intermediate point on the Pareto front, requiring an optimal sacrifice in growth rate to allocate sufficient resources to production without overly compromising the final cell density [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a host-aware modeling framework for identifying optimal strain designs.

Diagram 1: Host-Aware Model Workflow. This workflow uses multi-objective optimization to identify strain designs that balance growth and synthesis for optimal culture-level performance.

Quantitative Design Principles from Modeling

Host-aware modeling translates the growth-synthesis trade-off into concrete engineering guidelines for tuning enzyme expression levels.

Table 2: Strain Design Principles for Different Performance Goals [1]

| Performance Goal | Host Enzyme (E) Expression | Synthesis Enzyme (Ep, Tp) Expression | Resulting Cell Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Product Yield | Low | High | Low Growth, High Synthesis |

| High Volumetric Productivity | High (but not maximal) | Medium-High | Medium Growth, Medium-High Synthesis |

| High Cell Growth (Suboptimal for Production) | High | Low | High Growth, Low Synthesis |

These principles demonstrate that blindly engineering for maximum expression of pathway enzymes is not optimal. Instead, a balanced re-allocation of the host's resources is required, which can be achieved by tuning transcription rates or ribosome binding sites for both host and heterologous enzymes [1].

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Optimization

Theoretical models require empirical validation. The following section outlines key experimental methodologies for quantifying culture-level performance and testing intensification strategies.

Protocol: Quantifying KPIs in a Standard Fed-Batch Process

This protocol is foundational for establishing a baseline and evaluating engineered strains [8].

- Inoculation: Inoculate a bioreactor with cells (e.g., CHO cells) at a predefined density (e.g., (0.3 \times 10^6) cells/mL) in a defined basal medium.

- Process Control: Maintain critical parameters (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) at setpoints throughout the run.

- Feeding: Initiate a fixed-bolus or parametrically-controlled feeding strategy with nutrient concentrates (e.g., FMA, FMB) to prevent nutrient depletion.

- Monitoring: Sample the culture daily to measure:

- Viable Cell Density and Viability: (e.g., via trypan blue exclusion).

- Metabolite Concentrations: (e.g., glucose, glutamine).

- Product Titer: (e.g., via HPLC or ELISA).

- Harvest: Terminate the process when cell viability drops below a threshold (e.g., 70%).

- Calculation:

- Volumetric Productivity: (Final Titer × Harvest Volume) / (Bioreactor Volume × Total Process Time)

- Product Yield: (Total Product Mass) / (Total Mass of Key Substrate Consumed, e.g., Glucose)

Protocol: A Novel Hybrid Process with Intermediate Harvest

This intensified protocol demonstrates a method to surpass the limitations of standard fed-batch by decoupling growth and production phases [8].

- First Production Phase: Conduct a standard fed-batch cultivation until a desired point in the stationary or death phase (e.g., day 9-11).

- Intermediate Harvest: a. Transfer the entire cell broth from the bioreactor into a centrifuge. b. Centrifuge at a mild g-force (e.g., 190 ×g for 3 minutes) to pellet cells while leaving the product in the supernatant. c. Harvest the product-containing supernatant.

- Cell Washing and Return: a. Resuspend the cell pellet in fresh basal medium. b. Repeat the centrifugation step to remove residual spent media and by-products. c. Resuspend the washed cells in a mix of fresh basal and feed media. d. Return the concentrated, viable cells to the original bioreactor.

- Second Production Phase: Continue the cultivation with standard feeding and control until viability declines again.

- Analysis: Compare the total volumetric productivity and yield against the standard fed-batch control. This process has been shown to increase total mAb amount by 254% using the same reactor size and process duration [8].

The workflow for this intensified process is depicted below.

Diagram 2: Intermediate Harvest Process. This hybrid process intensifies production by removing spent media and by-products, enabling a second high-yield production phase from the same cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Implementing advanced bioprocesses requires a suite of specialized reagents, equipment, and computational tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioprocess Optimization

| Item / Technology | Function / Application | Relevance to KPI Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Defined Media Systems | Provides consistent, animal-origin-free nutrients for cell growth and production. | Optimizing yield by ensuring efficient substrate conversion and consistent product quality [8]. |

| Single-Use Bioreactors (SUBs) | Pre-sterilized, disposable culture vessels (e.g., Wave, ambr systems). | Enhances flexibility and reduces cross-contamination risk, facilitating rapid process development and intensification [9]. |

| Cell Retention Devices (ATF, TFF, FBC) | Enables perfusion by retaining cells in the bioreactor while removing spent media. | Critical for achieving very high cell densities, thereby dramatically increasing volumetric productivity [8] [7] [9]. |

| Host-Aware Modeling Software | Computational frameworks that simulate resource competition within engineered cells. | Identifies optimal genetic designs to maximize yield and productivity before lab construction, reducing experimental burden [1] [6]. |

| Multi-Parallel Bioreactor Systems | Miniaturized, high-throughput bioreactor systems (e.g., ambr15). | Allows for parallel screening of many process parameters and strain candidates, accelerating the optimization of volumetric productivity [8]. |

| Fluidized Bed Centrifuge (FBC) | Aseptic separation of cells from supernatant for intermediate harvest processes. | Enables novel hybrid process intensification, leading to step-change increases in total product output per reactor volume [8]. |

| Flufenoxadiazam | Flufenoxadiazam, CAS:1839120-27-2, MF:C16H9F4N3O2, MW:351.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Datpt | Datpt, MF:C24H39ClN6O3, MW:495.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the framework of host-aware biomanufacturing design, volumetric productivity and product yield stand as the definitive metrics for culture-level performance. They provide an unambiguous link to the primary economic drivers of bioproduction: capital and operational costs. While titre and specific rates retain value as diagnostic tools for cell physiology, they are insufficient as primary optimization targets.

The path forward requires the integrated use of host-aware computational models to identify optimal strain designs that strategically balance the innate growth-synthesis trade-off, coupled with the implementation of intensified operational modes like perfusion and hybrid fed-batch with intermediate harvest. By adopting this holistic approach, researchers and drug development professionals can design microbial cell factories and bioprocesses that are not only scientifically elegant but also economically superior, ultimately fostering a more efficient and accessible biopharmaceutical industry.

The transition from laboratory-scale discoveries to industrial-scale bioproduction represents a critical bottleneck in biotechnology and pharmaceutical development. A primary reason for this challenge is the context dependency of biological functions—the same genetic construct behaves differently across various host organisms and scales of operation [10]. Historically, synthetic biology has focused on optimizing engineered genetic constructs within a limited set of well-characterized chassis organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, often treating host-context dependency as an obstacle to be overcome rather than a design parameter to be exploited [10]. This approach has left significant potential untapped, as different microbial hosts possess unique physiological traits that could enhance biomanufacturing outcomes.

Host-aware modeling emerges as a transformative paradigm that explicitly accounts for how host physiology influences the function of engineered genetic systems. By creating computational bridges between molecular-level events, cellular resource allocation, and population-level dynamics in controlled bioreactor environments, these multi-scale models offer a path to more predictable and efficient bioprocesses [11] [10]. The "chassis effect"—whereby identical genetic manipulations exhibit different behaviors depending on the host organism—is no longer viewed merely as a nuisance but as a tunable design variable [10]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical framework for constructing and applying host-aware models across biological scales, with direct implications for biomanufacturing design principles.

Single-Cell Foundations: Resource-Aware Whole-Cell Models

Theoretical Framework and Key Components

At the core of host-aware modeling lies the resource-aware whole-cell model, which moves beyond simple phenomenological relationships to mechanistically represent the intracellular trade-offs and resource allocations that characterize biological systems [11]. These models explicitly simulate how heterologous gene expression competes with native cellular processes for finite resources.

Adapted from the framework published by Weiße et al., a comprehensive resource-aware model for E. coli incorporates several key elements [11]:

- Cellular Resource Pools: The model tracks shared cellular resources including ribosomes, RNA polymerase, and energy molecules (ATP equivalents).

- Proteome Partitioning: The proteome is divided into four categories: ribosomal proteins (r), transport proteins (et), metabolic proteins (em), and housekeeping proteins (q).

- Translation-Centric Energy Use: The model assumes translation accounts for total cellular energy consumption, with each amino acid addition requiring one energy unit.

The ordinary differential equations (ODEs) describing this whole-cell model capture the dynamics of 14 intracellular molecules, including mRNAs, mRNA:ribosome complexes, and proteins for each proteome category, plus imported substrate and energy molecules [11].

Modeling Division of Labor in Microbial Consortia

Resource-aware models can be extended to microbial consortia implementing division of labor (DOL) strategies, which distribute metabolic pathways across multiple strains to reduce cellular burden [11]. For a two-strain consortium degrading complex substrates like starch, one strain expresses an endohydrolase while another expresses an exohydrolase. Modeling reveals a critical balance where increasing enzyme expression enhances degradation until a threshold of burden is reached, beyond which the consortium consistently outperforms an equivalent single-cell monoculture [11].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Resource-Aware Whole-Cell Models

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Proteome Allocation | Ribosomal proteins (r), Transport proteins (et), Metabolic proteins (em), Housekeeping proteins (q) | Determines cellular capacity for different functional categories |

| Kinetic Parameters | mRNA degradation rate, Substrate import rate, Translation elongation rate | Governs temporal dynamics of gene expression and metabolism |

| Growth Laws | Relationship between ribosome concentration and growth rate | Links resource allocation to cellular fitness |

| Burden Parameters | Heterologous protein expression levels, Resource competition coefficients | Quantifies impact of engineered functions on host physiology |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Host Burden

Objective: Measure the burden imposed by heterologous gene expression on host growth and resource allocation.

Methodology:

- Strain Construction: Engineer isogenic strains with inducible expression systems controlling heterologous gene(s) of interest.

- Growth Rate Quantification: Measure growth rates (optical density) in controlled bioreactors across a range of expression induction levels.

- Resource Allocation Profiling: Use mass spectrometry to quantify proteome allocation changes under different burden conditions.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit experimental data to resource-aware model equations to estimate host-specific parameters.

Key Measurements:

- Growth rate (μ) as a function of inducer concentration

- Absolute protein abundances for ribosomal, metabolic, and heterologous proteins

- mRNA concentrations for key genes

- Metabolic flux measurements using isotopic tracers

Bridging Scales: From Cellular to Population Dynamics

Incorporating Host-Specific Physiological Traits

The transition from single-cell models to population-level predictions requires accounting for host-specific physiological traits that influence bioprocess performance. Different microbial hosts possess unique resource allocation strategies, metabolic network topologies, and regulatory mechanisms that significantly impact the performance of engineered genetic systems [10]. For instance, studies comparing genetic circuit behavior across multiple bacterial species have demonstrated that host selection influences key performance parameters including output signal strength, response time, growth burden, and expression of native carbon and energy pathways [10].

Recent advances in broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology facilitate the systematic exploration of chassis space by developing genetic tools that function across diverse microbial hosts [10]. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) provides one such modular system for cross-species genetic engineering [10]. This approach reconceptualizes the host chassis as a tunable module rather than a passive platform, enabling synthetic biologists to select optimal hosts based on application-specific requirements such as stress tolerance, substrate utilization capabilities, or biosynthetic pathway compatibility.

Model-Based Prediction of Chassis Effects

Computational models can predict chassis effects by incorporating host-specific parameters such as:

- Transcription and translation rates: Varying RNA polymerase and ribosome kinetics across species

- Metabolic network architecture: Differences in central carbon metabolism and energy generation

- Resource availability: Variations in pools of amino acids, nucleotides, and cofactors

- Stress response systems: Host-specific adaptation to bioprocess conditions

Table 2: Host-Specific Parameters Influencing Biomanufacturing Outcomes

| Parameter Category | Traditional Organisms (E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Non-Traditional Hosts (Rhodopseudomonas, Halomonas) |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Characteristics | Fast growth (20-60 min doubling), Moderate yields | Variable growth rates, Often higher biomass yields |

| Stress Tolerance | Limited native stress resistance | Specialized tolerances (high salinity, temperature extremes) |

| Metabolic Capabilities | Standard carbon utilization (glucose, glycerol) | Diverse substrate ranges (COâ‚‚, lignin derivatives, light) |

| Genetic Toolkits | Extensive, well-characterized | Emerging, limited modularity |

| Resource Allocation | Competitive at high growth rates | Often optimized for stress survival |

Bioreactor Control Architectures for Consortium Stabilization

A Novel Bioreactor Architecture for Composition Control

Industrial deployment of microbial consortia requires robust control strategies to prevent competitive exclusion and maintain stable community composition. Recent research has established a versatile control architecture for regulating density and composition of two-strain consortia without genetic engineering or drastic environmental changes [12]. This system comprises:

- Mixing Chamber: Hosts co-culture of both populations where the primary bioprocess occurs

- Reservoir Chamber: Maintains monoculture of the slower-growing population

- Interconnection System: Enables controlled transfer of the slower-growing strain from reservoir to mixing chamber

The control system utilizes three independent inputs:

- Dâ‚: Flow rate of fresh media into the mixing chamber

- Dâ‚‚: Flow rate of slower species from reservoir into mixing chamber

- D_R: Flow rate of fresh media in the reservoir

This architecture enables stable coexistence of competing populations with non-complementary growth rates (where one species always grows faster than the other) by actively managing the inflow of the slower-growing strain to balance natural competitive dynamics [12].

Control Strategies and Implementation

Both model-based and learning-based control strategies have been successfully implemented for consortium regulation:

Model-Based Control:

- Density Regulation: Uses measurements of optical density (OD) in each chamber to maintain biomass setpoints

- Ratio Control: Adjusts Dâ‚ and Dâ‚‚ to achieve desired population ratios in the mixing chamber

- Decoupled Architecture: Enables independent regulation of reservoir biomass, simplifying mixing chamber control

Sim-to-Real Learning Control:

- Synthetic Training: Uses calibrated mathematical models to generate training data

- Real-World Deployment: Transfers learned control policies to physical bioreactor systems

- Data Efficiency: Achieves robust control with minimal experimental data [12]

Experimental validation using E. coli consortia demonstrates precise regulation of consortium density and composition, including tracking of time-varying references and recovery from perturbations [12].

Experimental Protocol: Bioreactor Control Implementation

Objective: Implement and validate control strategies for maintaining desired composition in a two-strain microbial consortium.

Equipment Setup:

- Bioreactor Configuration: Interconnect two Chi.Bio reactors or similar systems with peristaltic pumps for media transfer [12].

- Sensing: Utilize integrated optical density (OD) sensors for real-time biomass monitoring.

- Control Interface: Establish communication between bioreactor microcontroller and host computer for advanced control implementation.

Control Implementation:

- Reservoir Control: Design controller for D_R to maintain xâ‚‚á´¿ at desired density despite dilution effect of Dâ‚‚.

- Mixing Chamber Control: Design controllers for Dâ‚ and Dâ‚‚ to regulate total biomass (xâ‚+xâ‚‚) and strain ratio (xâ‚/xâ‚‚).

- Constraint Management: Implement safeguards to prevent population extinction (minimum density constraints).

Validation Experiments:

- Setpoint Tracking: Test ability to achieve different consortium compositions

- Disturbance Rejection: Introduce perturbations and measure recovery performance

- Dynamic Tracking: Evaluate performance in tracking time-varying references

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Host-Aware Model Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Vector Systems | Cross-species genetic engineering | Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) for broad-host-range cloning [10] |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Tunable control of gene expression | Chemical-inducible (aTc, IPTG) or light-inducible systems for burden modulation [11] |

| Optical Density Sensors | Real-time biomass monitoring | Integrated OD sensors in Chi.Bio or similar bioreactor systems [12] |

| Resource Allocation Reporters | Quantify cellular resource status | Fluorescent reporters for ribosomal capacity, energy status, or stress responses |

| Metabolite Sensors | Monitor substrate consumption and product formation | Extracellular NMR or LC-MS for metabolic flux analysis |

| Peristaltic Pump Systems | Precise medium and culture transfer | Computer-controlled pumps for bioreactor interconnections [12] |

| Whole-Cell Modeling Software | Implement resource-aware models | Custom ODE solvers in Python/MATLAB incorporating proteome allocation [11] |

| Deferiprone-d3 | Deferiprone-d3, CAS:1346601-82-8, MF:C7H9NO2, MW:142.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Endophenazine D | Endophenazine D, MF:C24H26N2O7, MW:454.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Future Directions: Integrating Foundation Models and Multi-Scale Data

The next frontier in host-aware modeling involves the integration of biological foundation models (FMs) that leverage multimodal data—including sequence, structure, chemical properties, and textual information—to reason across biological scales [13]. Models like ProCyon (an 11-billion-parameter multimodal foundation model) combine unstructured textual information with molecular and structural embeddings to enable biological question answering and functional prediction [13].

Emerging capabilities in controllable generation allow direct embedding of manufacturability constraints into molecular design processes. Systems like PoET-2 support in-context controllable generation, enabling designers to specify desired properties or motifs during sequence synthesis [13]. Similarly, ForceGen represents the first generative framework to optimize for nonlinear mechanical and stability properties, incorporating real-world manufacturability considerations directly into the design process [13].

The integration of these advanced AI systems with mechanistic host-aware models creates powerful multi-scale design environments that can predict how genetic designs will perform from molecular through bioreactor scales, ultimately accelerating the development of robust biomanufacturing processes.

Multi-scale host-aware models represent a transformative approach to bioprocess development that explicitly accounts for how host physiology influences the performance of engineered biological systems. By creating computational bridges between resource-aware whole-cell models, population dynamics, and bioreactor control strategies, these integrated frameworks enable more predictable scaling from laboratory discovery to industrial bioproduction.

The architecture presented—spanning from single-cell resource allocation to bioreactor control systems—provides a roadmap for implementing host-aware design principles in biomanufacturing research. As foundation models and AI-driven design tools continue to advance, the integration of multimodal biological data and manufacturability constraints will further enhance our ability to design biological systems that perform predictably across scales, ultimately accelerating the development of sustainable biomanufacturing processes for pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and materials.

The engineering of biological systems is fundamentally constrained by a pervasive challenge: synthetic gene circuits do not function in isolation but are deeply embedded within and influenced by their host cellular environment. This phenomenon, termed the "host-effect," describes how the specific genetic, physiological, and metabolic context of a host cell dictates the performance of introduced genetic constructs [14] [15]. In the domain of biomanufacturing, where predictable and robust production is paramount, understanding and mitigating these effects is critical for transitioning from laboratory prototypes to deployable biological systems [14] [1]. The host-effect contravenes classical engineering principles of modularity and predictability, as the same genetic circuit can exhibit vastly different dynamics, stability, and output depending on the organism in which it operates [15].

The core of the issue lies in the fact that a host cell is not an empty vessel but a complex, self-regulating system with finite resources and evolved regulatory networks. Introducing a synthetic circuit creates an interdependent system where the circuit consumes host resources, thereby imposing a metabolic burden that can reduce host fitness, which in turn feedbacks to alter circuit function [14] [16] [17]. Framing biomanufacturing design principles within a "host-aware" model is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a necessary evolution for the field. This approach explicitly accounts for the dynamic interplay between construct and chassis, moving beyond simple component design to a holistic, system-level engineering strategy that is essential for achieving reliable, high-yield, and stable production processes [1] [16].

The Mechanistic Basis of the Host-Effect

The host-effect emerges from several interconnected biological phenomena. A comprehensive host-aware modeling framework must integrate these factors to accurately predict system behavior, as illustrated in the conceptual model below.

Figure 1: A conceptual model of core circuit-host interactions. This host-aware framework illustrates the key feedback loops, including growth feedback and resource competition, that generate complex, emergent dynamics and dictate the performance of synthetic genetic constructs.

Growth Feedback and Cellular Burden

A primary manifestation of the host-effect is growth feedback, a multiscale feedback loop where the operation of a synthetic circuit impacts the host's growth rate, which in turn alters circuit function. The expression of heterologous genes consumes cellular resources—such as nucleotides, amino acids, and energy—diverting them from native host processes essential for growth. This cellular burden manifests as a reduced cellular growth rate [14] [16]. Critically, growth rate is not merely an output but a key input that influences circuit dynamics; it sets the dilution rate for cellular components, including the circuit's own mRNA and proteins. A higher growth rate leads to faster dilution, potentially driving a circuit out of a desired state (e.g., turning off a bistable switch), while severe burden can slow dilution sufficiently to create entirely new stable states [14]. For example, significant burden from a self-activation circuit can induce emergent bistability in a system that would otherwise be monostable, while ultrasensitive growth feedback can even lead to tristability [14].

Resource Competition

At a more granular level, resource competition arises from the finiteness of the host's gene expression machinery. Synthetic circuits and native genes compete for a limited pool of shared resources, primarily RNA polymerases (RNAP) and ribosomes [14] [17]. This competition creates hidden, indirect coupling between seemingly independent genetic modules; the activity of one module can repress another by depleting the shared resource pool [14]. The dominant form of competition differs between biological systems: translational resources (ribosomes) are typically the primary bottleneck in bacterial cells, whereas competition for transcriptional resources (RNAP) is more dominant in mammalian cells [14]. Beyond the core machinery, competition can also occur for sigma factors, shared transcription factors, and degradation machinery [14].

Context-Dependent Genetic Interactions

The host-effect is also governed by local genetic context. Intergenic context factors, such as the relative order and orientation of genes (syntax), can lead to transcriptional interference or retroactivity, where a downstream module sequesters a signal from an upstream module, altering its function [14]. Furthermore, identical genetic circuits can exhibit divergent performances across different microbial hosts due to profound differences in their underlying physiology, a clear demonstration of the chassis effect [15]. Hosts with more similar physiological metrics, such as growth parameters and molecular composition, tend to support more similar circuit performance, highlighting that host physiology is a key determinant of the host-effect [15].

Quantitative Impacts: Measuring the Host-Effect

The host-effect has tangible, measurable consequences on bioproduction metrics. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from host-aware modeling studies that illustrate the trade-offs between growth, production, and evolutionary stability.

Table 1: Quantitative Impacts of Host-Effect on Bioproduction and Circuit Stability

| Metric | Host System | Impact of Host-Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Productivity | Engineered E. coli | An optimal sacrifice in growth rate (to ~0.019 minâ»Â¹) is required for maximum productivity; both too high and too low growth rates reduce output. | [1] |

| Product Yield | Engineered E. coli | High yield requires high expression of synthesis enzymes but low expression of a key host metabolic enzyme, leading to a slow-growth, high-synthesis phenotype. | [1] |

| Functional Half-Life (Ï„â‚…â‚€) | Engineered E. coli with genetic controllers | Growth-based feedback controllers can extend the functional half-life of a circuit over threefold compared to open-loop systems. | [16] |

| Stable Output Duration (τ±â‚â‚€) | Engineered E. coli with genetic controllers | Negative autoregulation (intra-circuit feedback) can significantly prolong the time output remains within 10% of its initial value. | [16] |

These data underscore a fundamental growth-synthesis trade-off in engineered systems [1]. Strains engineered for very high growth rates consume most of the substrate for biomass, resulting in low product yield and titers. Conversely, strains with extremely low growth but high synthesis rates also achieve low volumetric productivity because the small cell population takes too long to accumulate a significant amount of product [1]. Therefore, maximizing culture-level performance is a balancing act that requires a host-aware perspective.

Methodologies for Characterizing the Host-Effect

Host-Aware Computational Modeling

A powerful approach to deconvolute the host-effect is the use of multi-scale mechanistic models. These "host-aware" frameworks integrate dynamics at multiple levels: the single cell (capturing growth, metabolism, and gene expression), the population (batch culture growth and nutrient consumption), and even evolutionary timescales (mutation and selection) [1] [16]. For example, one study augmented a model of host-circuit interactions with a population dynamics model that simulates an evolving population of E. coli, where different strains (mutants) compete for nutrients, and mutation is implemented as transitions between these strains [16]. This allows for the in silico quantification of evolutionary longevity metrics like Ï„â‚…â‚€ and τ±â‚â‚€ [16]. Similarly, multiobjective optimization within such models can reveal Pareto fronts that define the optimal trade-offs between growth rate, synthesis rate, volumetric productivity, and yield, providing clear design principles for strain engineering [1].

Experimental Tools and Protocols

Several key experimental methodologies have been developed to quantify and mitigate the host-effect.

Capacity Monitor Assay: This protocol uses a stably integrated genetic construct to measure a host cell's available gene expression capacity [17].

- Purpose: To provide a quantitative, high-throughput proxy for the cellular burden imposed by a synthetic circuit.

- Procedure:

- A construct expressing a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) from a constitutive promoter is integrated into the host genome. This serves as the reference "capacity monitor."

- The synthetic circuit of interest is introduced into this engineered host.

- The fluorescence output of the genomic capacity monitor is measured. A decrease in its fluorescence indicates that the synthetic circuit is consuming cellular resources (RNAP, ribosomes), thereby reducing the capacity available for the monitor's expression.

- The reduction in monitor fluorescence is correlated with the burden imposed by the circuit, allowing for the screening of low-burden construct designs [17].

Host-Associated Quantitative Abundance Profiling (HA-QAP): While developed for plant root microbiomes, the principle of this method is broadly applicable. It addresses the limitation of relative abundance data in amplicon sequencing by quantifying the absolute abundance of microbes relative to the host [18].

- Purpose: To accurately examine total microbial load and the colonization of individual microbiome members relative to host tissue, avoiding spurious conclusions from relative abundance data.

- Procedure:

- DNA is extracted from a host-associated sample (e.g., plant root).

- The copy numbers of a microbial marker gene (e.g., bacterial 16S rRNA gene) and a single-copy host gene (from the plant genome) are quantified using qPCR.

- The copy-number ratio of the microbial gene to the host gene is calculated. This ratio provides a direct measure of the total microbial load relative to the host biomass.

- This absolute ratio can then be used to normalize data from high-throughput amplicon sequencing, moving from relative to host-adjusted absolute abundance [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

To effectively study and engineer within the context of the host-effect, researchers can leverage a growing toolkit of reagents and strategies, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Host-Effect Mitigation

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Key Feature / Benefit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity Monitors | Genomic fluorescent reporter to quantify available cellular resources. | Enables high-throughput screening of genetic parts and circuits for low burden. | [17] |

| Orthogonal Ribosomes | Engineered ribosomes that only translate mRNAs from synthetic circuits. | Insulates circuit translation from host competition, reducing burden and retroactivity. | [17] |

| Feedback Controllers (Transcriptional) | Transcription-factor based systems that sense and regulate circuit output. | Can maintain set-point expression levels and improve robustness; e.g., negative autoregulation. | [16] [17] |

| Feedback Controllers (Post-Transcriptional) | Small RNA (sRNA) based systems that silence circuit mRNA. | Provides strong control with lower burden than TF-based controllers; enhances evolutionary longevity. | [16] |

| Growth-Based Feedback Controllers | Genetic circuits that use host growth rate as an input for regulation. | Extends the functional half-life (persistence) of circuits in evolving populations. | [16] |

| Host-Aware Model Frameworks | Multi-scale computational models integrating circuit, host, and population dynamics. | Predicts emergent dynamics and identifies optimal engineering strategies in silico. | [1] [16] |

| Macquarimicin B | Macquarimicin B, MF:C22H28O6, MW:388.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| ALG-000184 | ALG-000184, MF:C23H20FN4Na2O8P, MW:576.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Visualization: An Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive, integrated workflow that combines computational and experimental approaches to characterize and mitigate the host-effect, embodying the host-aware design principle.

Figure 2: A host-aware design-build-test-learn (DBTL) workflow for characterizing genetic constructs. This integrated pipeline leverages computational modeling, cell-free prototyping, and physiological assays to account for host-context from the outset.

The 'host-effect' is an inescapable reality in synthetic biology and bioprocess engineering. The evidence is clear: successful biomanufacturing design must transition from a circuit-centric view to a host-aware paradigm that explicitly incorporates the dynamic interplay between the synthetic construct and its cellular context [14] [1] [16]. This requires a synergistic combination of multi-scale modeling, sophisticated experimental tools for burden quantification, and genetic control strategies that actively maintain circuit function and host health.

Future research must focus on enhancing the generality and predictive power of host-aware models. Key challenges include extending these frameworks to more complex circuit architectures, diverse host organisms, and dynamic industrial environments [14]. Furthermore, the development of robust, context-insulated genetic parts and the creation of minimal or specialized chassis strains will be crucial for reducing the unpredictable nature of the host-effect [17]. By systematically integrating host-aware principles into the DBTL cycle, the field can overcome a major bottleneck, paving the way for more predictable, stable, and efficient biomanufacturing systems that perform reliably from the lab bench to industrial deployment.

From Theory to Strain: Implementing Host-Aware Design Principles for Maximum Output

The pursuit of maximal performance in microbial cell factories has long been guided by the intuitive goal of maximizing either specific growth or product synthesis rates. However, emerging research leveraging host-aware computational models demonstrates that this maximization paradigm is fundamentally flawed. This technical guide elaborates on the principle of the 'Myth of Maximization,' which posits that the highest volumetric productivity in batch cultures is achieved not at maximum rates of growth or synthesis, but through a carefully balanced medium-growth, medium-synthesis phenotype [1] [2]. We dissect the quantitative evidence underpinning this principle, detail the experimental and computational methodologies for its implementation, and contextualize its vital role within a broader host-aware framework for biomanufacturing design.

In metabolic engineering, a persistent challenge has been the inherent trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis due to competition for the host's finite native resources, such as precursors, energy, and gene expression machinery [19]. Conventional strain engineering often selects for candidates with the highest specific growth rate (λ) or product synthesis rate (rTp), operating on the assumption that maximizing one or both of these cell-level metrics will translate to superior culture-level performance [1].

Host-aware modeling challenges this assumption by integrating cell-level dynamics—encompassing metabolism, resource competition, and gene expression—with population-level behavior in a batch culture. This multi-scale modeling reveals that the culture-level metrics of volumetric productivity and product yield are not linearly correlated with cell-level growth and synthesis rates [1] [2]. The "Myth of Maximization" is the revelation that pushing either growth or synthesis to its extreme diverts excessive cellular resources, ultimately crippling the overall output of the batch process. Instead, peak performance is found at an intermediate operating point, a counter-intuitive but critical insight for rational bioprocess design.

Computational Evidence: Unveiling the Optimal Balance

The 'Myth of Maximization' was systematically uncovered through multi-objective optimization of a host-aware model, exploring the scaling of transcription rates for a host enzyme (E) and synthesis pathway enzymes (Ep, Tp) [1].

The Performance Trade-Off at the Culture Level

When strains are optimized for high growth and synthesis rates at the single-cell level, their performance in a batch culture reveals a critical trade-off. The following table summarizes the culture-level performance of three characteristic strains from the Pareto front, illustrated in the diagram below.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Different Strain Designs

| Strain Type | Specific Growth Rate (λ, minâ»Â¹) | Specific Synthesis Rate (rTp) | Volumetric Productivity | Product Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Growth, High-Synthesis | Low (e.g., ~0.01) | High | Low | High |

| Medium-Growth, Medium-Synthesis | Medium (e.g., 0.019) | Medium | Maximum | Medium |

| High-Growth, Low-Synthesis | High (e.g., >0.019) | Low | Low | Low |

Diagram 1: The Growth-Synthesis Trade-Off and Culture Performance. Strains on the Pareto front (green) exhibit a trade-off between growth and synthesis. The strain with a balanced medium-growth, medium-synthesis profile (B) achieves the highest volumetric productivity at the culture level, while strains at the extremes (A, C) perform poorly [1].

Simulations of batch culture kinetics demonstrate that the high-growth, low-synthesis strain consumes most of the substrate for biomass rather than product, leading to low yield and productivity. Conversely, the low-growth, high-synthesis strain generates a population that is too small to produce a high volume of product quickly, despite its efficient use of substrate. The balanced medium-growth, medium-synthesis strain optimally leverages a sufficiently large population and efficient per-cell production to achieve peak volumetric productivity [1].

Optimal Expression Levels for Balanced Strains

The host-aware model identifies distinct design principles for engineering these balanced strains.

Table 2: Enzyme Expression Tuning for Optimal Performance

| Enzyme / Protein | Role | Expression Level for High-Yield Strains | Expression Level for High-Productivity Strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Enzyme (E) | Catalyzes a growth-limiting step in native metabolism | Low | High |

| Synthesis Enzymes (Ep, Tp) | Catalyze steps in the heterologous product pathway | High | Low to Medium |

| Substrate Transporter | Facilitates nutrient uptake | Universally beneficial to boost expression for improved productivity |

The optimal design for maximum productivity requires a non-intuitive sacrifice in growth rate (e.g., to approximately 0.019 minâ»Â¹ in the model) and a precise, moderate expression level of synthesis enzymes [1] [2]. This delicate balance is difficult to identify through traditional lab engineering alone, highlighting the value of predictive host-aware modeling.

Experimental Protocol: From In Silico to In Vivo

Implementing this principle requires a cyclical workflow of computational design, genetic implementation, and phenotypic validation.

Host-Aware Model Simulation and Multi-Objective Optimization

Objective: Identify the Pareto-optimal set of transcription rate scaling factors (sTXE, sTXEp, sTXTp) that balance growth (λ) and synthesis (rTp), or productivity and yield. Methodology:

- Model Formulation: Develop a mechanistic, multi-scale model that integrates:

- Cell-Level Dynamics: Cell growth, core metabolism, host enzyme and ribosome biosynthesis, heterologous gene expression, and product synthesis, accounting for resource competition [1] [2].

- Culture-Level Dynamics: Population growth, nutrient consumption, and product accumulation in a batch reactor [1].

- Optimization: Apply multi-objective optimization algorithms (e.g., genetic algorithms) to the model to compute the Pareto front for the chosen objectives (e.g., growth rate vs. synthesis rate) [1].

- Culture Simulation: Simulate batch cultures for each Pareto-optimal strain design to calculate the key performance metrics (KPIs): volumetric productivity and product yield [1].

Strain Construction and Library Generation

Objective: Create a library of strain variants with modulated expression of target enzymes. Methodology:

- Genetic Modulation: For each target gene (E, Ep, Tp), create a library of expression variants by:

- Altering promoter sequences (RNA polymerase binding strength).

- Engineering ribosome binding sites (RBS) [1].

- High-Throughput Assembly: Use advanced synthetic biology platforms (e.g., self-selecting vector systems) to rapidly assemble thousands of genetic construct combinations for in-silico predicted optimal expression levels [2].

Phenotypic Characterization and Validation

Objective: Measure the growth, synthesis, and culture-level performance of engineered strains. Methodology:

- Cell-Level Assays: In controlled bioreactors, measure the specific growth rate (λ) and specific product synthesis rate (rTp) for each strain variant [1].

- Batch Culture Performance: Conduct small-scale batch fermentation for selected leads. Monitor biomass (OD600), substrate concentration, and product titer over time.

- KPI Calculation: Calculate volumetric productivity (grams product per liter per hour) and yield (grams product per gram substrate) from the batch culture data [1].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Principle 1. A cyclic workflow integrating computational modeling and experimental validation to identify strains that embody the 'Myth of Maximization' principle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Implementing Principle 1

| Reagent / Material / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Host-Aware Model Software | Computational framework simulating cell & culture dynamics. | In-silico prediction of optimal enzyme expression levels and strain performance [1] [2]. |

| Promoter Library | A collection of DNA sequences with varying transcriptional strengths. | Genetically tuning the expression levels of host (E) and pathway (Ep, Tp) enzymes [1]. |

| RBS Library | A collection of ribosome binding sites with varying translational strengths. | Fine-tuning protein expression levels of target enzymes independently of transcription [1]. |

| Chemically Defined Media | A medium with a precise and known chemical composition, free of animal-derived components. | Ensuring reproducible cell growth and metabolic analysis during strain characterization [20]. |

| Fed-Batch or Perfusion Bioreactor Systems | Bioprocessing systems for controlled cell culture. | Performing batch culture validation to measure volumetric productivity and yield under controlled conditions [21]. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm | Computational method for optimizing conflicting objectives (e.g., growth vs. synthesis). | Identifying the Pareto front of optimal strain designs in the host-aware model [1]. |

| SID 3712249 | SID 3712249, CAS:522606-67-3, MF:C17H21N7, MW:323.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganoderic acid TR | Ganoderic acid TR, MF:C30H44O4, MW:468.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The principle of the 'Myth of Maximization' represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, moving the field away from intuitive maximization and toward a rational, host-aware design philosophy. By demonstrating that peak volumetric productivity is achieved through a balanced medium-growth, medium-synthesis phenotype, this principle provides a concrete target for strain engineering efforts. Its successful implementation relies on the synergistic use of multi-scale host-aware models, high-throughput genetic engineering, and precise phenotypic validation. As a core tenet of a broader host-aware framework, this principle is foundational to the future development of efficient, scalable, and economically viable microbial cell factories.

The pursuit of efficient microbial cell factories is fundamentally challenged by a cellular dilemma: the competition for finite metabolic and gene expression resources between cell growth and the synthesis of a desired product [1]. Traditional metabolic engineering, which attempts to optimize a cell for both growth and production simultaneously, often results in suboptimal compromises due to this inherent trade-off [2]. This limitation becomes acutely visible at the scale of batch cultures, where strain performance is measured by volumetric productivity and yield—metrics that do not always correlate directly with high specific growth or synthesis rates observed at the single-cell level [1].

The emergence of host-aware computational models provides a transformative framework for understanding and overcoming this challenge. These multi-scale models integrate cell-level dynamics—including metabolism, resource competition, and gene expression—with population-level behavior in a batch culture [1] [2]. This "host-aware" perspective reveals that the highest volumetric productivity is not achieved by simply maximizing growth or synthesis rates. Instead, these models identify a carefully balanced "medium-growth, medium-synthesis" point as optimal for single-phase systems [2]. However, to break past the fundamental limits of this trade-off, a more sophisticated strategy is required: dynamic two-stage control, which temporally separates the objectives of growth and production [1].

This principle of decoupling growth from production involves programming cells to first dedicate all resources to achieving high biomass during a growth phase. Then, at a defined switch time, the population is triggered to transition to a high-synthesis, low-growth state dedicated to product manufacture [1] [22]. By analyzing different genetic circuit topologies, host-aware models have shown that the highest performance is achieved by circuits that, upon induction, actively inhibit the host's native metabolic enzymes responsible for growth, effectively re-routing the cell's resources toward the synthesis of the target chemical [2]. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the implementation, mechanisms, and quantitative assessment of this foundational principle for next-generation biomanufacturing.

Core Mechanism and Key Signaling Pathways

Dynamic two-stage control operates on the principle of metabolic deregulation. Central metabolic networks in microbes are highly regulated and responsive to environmental conditions. While this adaptability benefits survival, it is detrimental to process robustness in industrial fermentation, as subtle changes in conditions can significantly alter product synthesis fluxes [23]. Implementing dynamic control during a nutrient-limited stationary phase deliberately deregulates this central metabolism.

The deregulation is achieved by dynamically reducing the levels of key central metabolic enzymes. This alteration of metabolite pools removes native regulatory inhibitions, resulting in a metabolic network that is less sensitive to environmental variations and more amenable to redirecting flux toward product formation [23] [24]. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing and benefiting from a two-stage dynamic control bioprocess.

At the molecular level, this deregulation unfolds through several key signaling and metabolic pathways, as elucidated in studies using E. coli:

- Alleviation of Glucose Uptake Inhibition: Reducing citrate synthase (GltA) levels leads to a decrease in alpha-ketoglutarate pools. This alleviates alpha-ketoglutarate-mediated inhibition of glucose uptake, thereby increasing carbon flux into the system [23].

- Improvement of NADPH Fluxes: Decreasing enoyl-ACP reductase (FabI) activity reduces fatty acid metabolite pools. This alleviates the inhibition of the membrane-bound transhydrogenase (PntAB), which is crucial for generating NADPH, a key cofactor for many biosynthesis pathways [23].

- Activation of the SoxRS Regulon and Acetyl-CoA Flux: Reducing glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf) levels lowers NADPH pools. This drop activates the SoxRS regulon, which among other actions, increases the expression of pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (YdbK). The increased YdbK activity drives higher acetyl-CoA flux. Furthermore, the reduced ferredoxin generated by YdbK can be used by a ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (Fpr) to reduce NADP+ to NADPH, thus enhancing NADPH fluxes despite the initial pool reduction [23].

The following pathway diagram details this interconnected molecular mechanism.

Quantitative Performance Data

The efficacy of dynamic two-stage control is demonstrated by its successful application in producing a range of industrially relevant chemicals. The strategy not only achieves high titers but, more importantly, confers exceptional process robustness, enabling straightforward scalability without the need for extensive re-optimization [23].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from documented case studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Two-Stage Dynamic Control in Engineered E. coli

| Target Chemical | Maximum Titer Achieved | Key Enzymes Dynamically Regulated | Primary Regulatory Mechanism Unlocked | Scalability Demonstration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xylitol [23] | ~200 g/L | FabI, Zwf | Improved NADPH flux via transhydrogenase activation & SoxRS regulon. | Successful scale-up from microfermentation screens to instrumented bioreactors. |

| Citramalate [23] | ~125 g/L | GltA, Zwf | Alleviation of glucose uptake inhibition & increased acetyl-CoA flux. | Facile scale-up without traditional process optimization. |

| L-Alanine [23] | Information in search results is limited | GltA, FabI, Zwf (inferred) | General deregulation of central metabolism for improved robustness. | Improved process robustness and scalability validated. |

From a host-aware modeling perspective, the performance can be understood through the lens of culture-level metrics. Simulations reveal that for a single-stage process, the maximum volumetric productivity is achieved at a carefully balanced "medium-growth, medium-synthesis" point, not at the extremes of either rate [1] [2]. However, two-stage dynamic control supersedes this static trade-off.

Host-aware models have quantified the superiority of two-stage strategies, showing that the highest performance is achieved by genetic circuits which, after an optimal switch time, inhibit host metabolism to redirect resources toward product synthesis [1] [2]. This approach allows the population to first reach a high density (high growth) before switching to a high-synthesis, low-growth state, thereby maximizing both the catalyst (cell) concentration and its specific productivity.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines the core methodologies for implementing a two-stage dynamically controlled bioprocess, from the genetic tools to the fermentation protocol.

Molecular Biology Toolkit: Implementing Dynamic Control

The dynamic deregulation of metabolism is implemented using a combination of synthetic biology tools. A highly effective method involves the use of "metabolic valves" that employ a two-pronged approach to reduce enzyme levels [23].

- Controlled Proteolysis: Target genes are engineered to encode C-terminal degron tags (e.g., DAS+4). These tags signal the cellular degradation machinery to rapidly break down the protein, reducing its functional level within the cell [23].

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): The native E. coli CRISPR Cascade system is utilized for gene silencing. Silencing gRNAs (guided RNAs) targeting the genes of interest are expressed from plasmids (e.g., pCASCADE plasmids). When the Cascade system is induced, it complexes with the gRNAs and blocks transcription of the target genes, leading to a further reduction in enzyme levels [23].

The combination of these two methods has been shown to achieve >95% reduction in Zwf levels and an 80% reduction in GltA levels [23].

Standardized Two-Stage Fermentation Process

The following protocol describes a standardized two-stage, phosphate-depleted process for E. coli, which has been successfully used for the production of citramalate and xylitol [23].

Stage 1: Growth Phase

- Inoculum & Media: Inoculate a bioreactor containing a defined mineral medium with essential nutrients, including a source of phosphate.

- Conditions: Maintain optimal growth conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen for aerobic processes).

- Objective: Allow cells to grow exponentially until the phosphate source is nearly completely depleted. Phosphate depletion serves as a natural and effective trigger for the transition to stationary phase and the induction of the production stage.

Stage 2: Production Phase & Induction of Dynamic Control

- Induction: Upon phosphate depletion, induce the expression of the dynamic control systems. This typically involves:

- Adding an inducer (e.g., arabinose) to activate the expression of the CRISPR Cascade system and the proteolysis machinery.

- Initiating a feed of carbon source (e.g., glucose) to provide continuous substrate for product synthesis.

- Conditions: Maintain conditions suitable for enzyme activity and cell viability (e.g., pH, aeration), though growth is now severely limited.

- Monitoring: Monitor carbon source feeding, product formation, and byproducts until the end of the fermentation run.

- Induction: Upon phosphate depletion, induce the expression of the dynamic control systems. This typically involves:

Alternative Induction Triggers and Circuits

While phosphate depletion and chemical inducers are effective, other induction triggers can be used in a two-stage framework, each with advantages and limitations.

- Chemical Inducers (aTC, IPTG): Well-characterized and widely used but can be costly at an industrial scale and irreversibly change cell expression [22].

- Temperature Shifts: Using thermo-sensitive promoters (e.g., PR/PL). Easily applied and removed but suboptimal temperatures can stress cells and affect the activity of native enzymes [22].

- Optogenetic Systems (Blue Light/Red Light): Offer high temporal precision. However, light penetration can be poor in high-density cultures, and the requirement for specialized equipment can be a barrier [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key reagents and genetic tools essential for constructing and testing microbial strains engineered for dynamic two-stage control.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Dynamic Metabolic Control

| Reagent / Tool Name | Type/Category | Key Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DAS+4 Degron Tag [23] | Proteolysis Tag | Appended to the C-terminus of a target protein to flag it for rapid cellular degradation, reducing enzyme activity. |

| pCASCADE Plasmids [23] | CRISPRi Vector | Plasmid system for expressing silencing gRNAs that guide the CRISPR Cascade complex to block transcription of target metabolic genes. |

| Phosphate-Limited Media [23] | Fermentation Media | Defined mineral media where phosphate depletion serves as a natural metabolic trigger to transition from growth to production phase. |

| aTC / IPTG [22] | Chemical Inducer | Small molecule inducers used to externally trigger the expression of dynamic control circuits (e.g., CRISPRi) at a pre-determined time. |

| PR/PL Promoter System [22] | Temperature-Sensitive Promoter | A promoter system repressed at 30°C and activated at 37-42°C, used to trigger the production phase via a simple temperature shift. |

| EL222 Optogenetic System [22] | Light-Sensitive Circuit | A system using blue light to induce a conformational change in the EL222 protein, activating transcription from a target promoter (e.g., PC120). |

| Emerimicin IV | Emerimicin IV, MF:C77H120N16O19, MW:1573.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Halomicin C | Halomicin C, MF:C43H58N2O13, MW:810.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The principle of dynamic two-stage control represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, moving beyond static optimization to embrace the temporal dimension of cell programming. By decoupling growth from production, this strategy directly addresses the core conflict of resource allocation in engineered microbes, leading to significant gains in process robustness, volumetric productivity, and scalability [23] [1].