Integrating 13C-MFA with Constraint-Based Models for Plants: A Roadmap for Predictive Metabolic Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the integration of 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) with constraint-based models (CBMs) in plant systems.

Integrating 13C-MFA with Constraint-Based Models for Plants: A Roadmap for Predictive Metabolic Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the integration of 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) with constraint-based models (CBMs) in plant systems. It covers the foundational principles of both techniques, explores advanced methodologies for their synergistic application, and addresses key challenges in model validation and optimization. By outlining practical frameworks for troubleshooting and multi-model inference, this resource aims to enhance the reliability of metabolic models, thereby accelerating their use in plant metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and biomedical research for developing sustainable production platforms and understanding plant-derived compound synthesis.

The Core Principles: Understanding 13C-MFA and Constraint-Based Modeling in Plant Metabolism

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a forceful tool for quantifying in vivo metabolic pathway activity in biological systems [1]. For plant research, this technology is indispensable for understanding intracellular metabolism and revealing the pathophysiology mechanism underlying responses to environmental stresses [1] [2]. The core principle of 13C-MFA involves using stable isotopic tracers to track carbon flow through metabolic networks, enabling researchers to quantify the absolute conversion rates of metabolites within central carbon metabolism [1] [3]. Unlike other omics technologies that provide static snapshots of cellular components, flux analysis captures the dynamic functional phenotype that emerges from complex interactions across genome, transcriptome, and proteome levels [4].

The integration of 13C-MFA with constraint-based modeling frameworks represents a powerful approach for plant systems biology. While 13C-MFA uses experimental isotopic labeling data to estimate fluxes, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) uses optimization principles to predict flux distributions based on assumed cellular objectives [4] [5]. Combining these approaches allows researchers to leverage the strengths of both methodologies—utilizing the accuracy of 13C-MFA for central carbon metabolism while extending insights to genome-scale metabolic networks through FBA [4]. This integration is particularly valuable for plant research, where metabolic flexibility in response to environmental changes is crucial for adaptation and productivity.

Classification of 13C Metabolic Fluxomics

The 13C-MFA methodology family has evolved into diverse branches, each with specific applications and technical requirements [1]. Understanding these classifications helps researchers select the most appropriate approach for their specific plant research questions.

Table 1: Classification of 13C-Based Metabolic Fluxomics Methods

| Method Type | Applicable Scene | Computational Complexity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Fluxomics (Isotope Tracing) | Any system | Easy | Provides only local and qualitative flux information |

| Metabolic Flux Ratios Analysis | Systems where flux, metabolites, and labeling are constant | Medium | Provides only local and relative quantitative values |

| Kinetic Flux Profiling | Systems where flux, metabolites are constant while labeling is variable | Medium | Provides only local and relative quantitative values |

| Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) | Systems where flux, metabolites and their labeling are constant | Medium | Not applicable to dynamic systems |

| Isotopically Instationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA) | Systems where flux, metabolites are constant while labeling is variable | High | Not applicable to metabolically dynamic systems |

| Metabolically Instationary 13C-MFA | Systems where flux, metabolites and labeling are variable | Very High | Technically challenging to perform |

For plant research, Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) has been widely applied to investigate central metabolic pathways in various plant organs, including maize embryos [1], Arabidopsis leaves [1], and developing camelina seeds [1]. The isotopically instationary approach (INST-MFA) offers advantages for studying systems where achieving isotopic steady state is impractical, such as in slow-growing plant tissues or when investigating rapid metabolic responses to environmental stimuli [1].

Workflow and Principles of 13C-MFA

The standard 13C-MFA workflow involves multiple interconnected steps that integrate experimental biology with computational modeling [2] [3]. The fundamental principle relies on the fact that different flux distributions produce distinct isotope labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites [1]. By measuring these labeling patterns and using computational algorithms to find the flux map that best fits the experimental data, researchers can quantify metabolic flux distributions with remarkable accuracy.

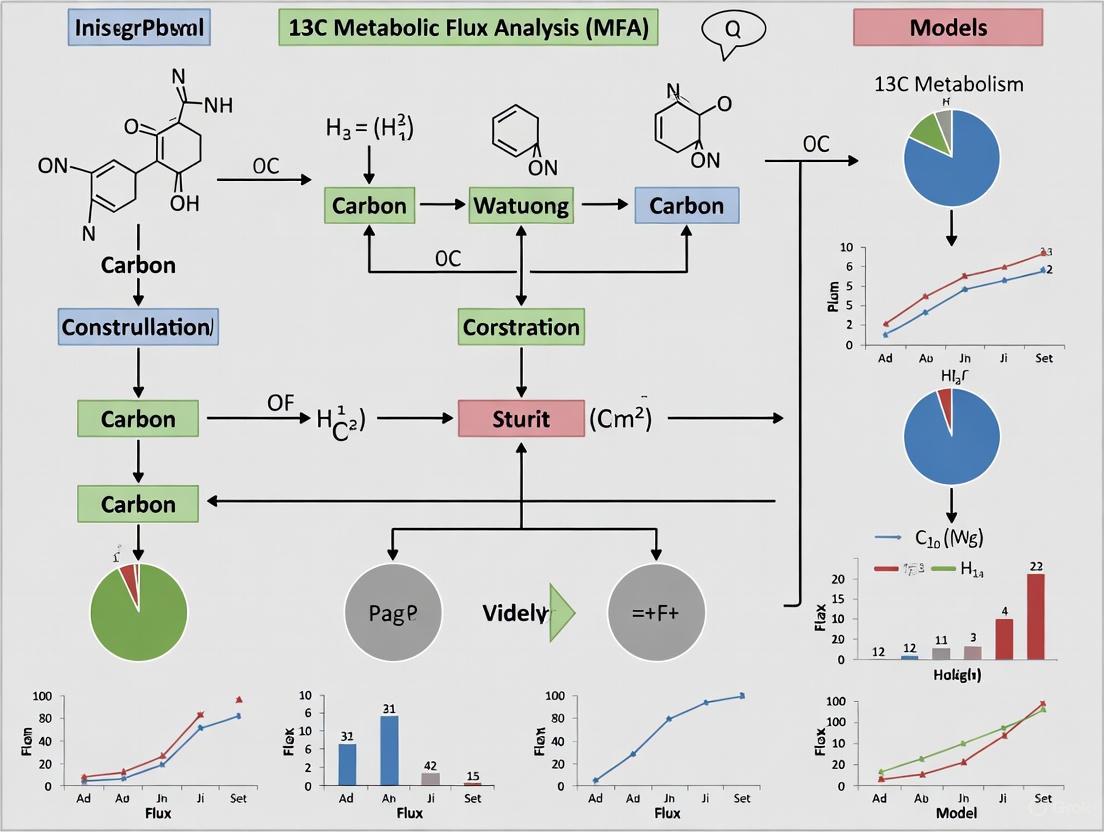

Figure 1: 13C-MFA integrates wet-lab experiments with computational modeling to transform isotopic labeling data into quantitative flux maps.

Mathematical Foundation

The flux estimation process in 13C-MFA can be formalized as an optimization problem [1]. The algorithm searches for the flux vector (v) that minimizes the difference between experimentally measured isotopic labeling patterns (xM) and model-predicted labeling patterns (x), while satisfying stoichiometric constraints (S·v = 0) and other physiological constraints (M·v ≥ b) [1]. The objective function is typically formulated as:

Where Σε represents the covariance matrix of the measured values, An and Bn represent system matrices determined by metabolic reaction topology and atomic transfer relationships, and Xn represents vectors of the isotope labeling model for corresponding elementary metabolite units [1].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

The choice of 13C-labeled substrate is a critical factor that significantly influences the resolution and scope of flux analysis [2] [3]. For plant systems, commonly used carbon sources include glucose, acetate, and glycerol, with glucose being particularly relevant for studying photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic tissues [3].

Table 2: Recommended Tracers for Plant Cell 13C-MFA

| Tracer Type | Applications | Advantages | Cost Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C] Glucose | General purpose flux analysis | Significantly improves flux estimation accuracy | Higher cost (~$600/g) [3] |

| 80% [1-13C] + 20% [U-13C] Glucose Mixture | Standard flux elucidation | Guarantees high 13C abundance in various metabolites | Moderate cost [2] |

| Pure [1-13C] Glucose | Pathway discovery | Easier to trace labeled carbons in intermediates | Lower cost (~$100/g) [3] |

| [U-13C] Glucose | Comprehensive pathway analysis | Enables tracking of complete carbon skeletons | Highest cost |

Cell Cultivation and Sample Collection

Ensuring metabolic and isotopic steady state is crucial for successful SS-MFA experiments [3]. For plant cell cultures, the following approaches are recommended:

- Prolonged incubation: Maintain cells for more than five residence times at constant temperature to ensure the system reaches metabolic and isotopic steady state [3].

- Controlled growth conditions: Maintain constant cell growth rate (e.g., during exponential growth phase) to stabilize metabolic fluxes [3].

- Parallel labeling experiments: Conduct multiple tracer experiments with differently labeled substrates to significantly improve flux estimation accuracy [4]. Research indicates that two parallel labeling experiments can control flux estimation uncertainty within 5% [3].

Isotopic Labeling Measurement

The measurement of 13C-labeling in metabolites is typically achieved using mass spectrometry or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [1] [2].

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): The most commonly used analytical method, providing high-precision determination of isotope distributions in derivatized samples [2] [3].

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Suitable for metabolites with trace amounts or high instability due to high sensitivity [2].

- Tandem MS (GC-MS/MS or LC-MS/MS): Significantly improves detection sensitivity and resolution through multiple mass spectrometry analyses [3].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Provides detailed structural information and positional labeling data, though with generally lower resolution than MS-based methods [3].

Systematic correction of naturally labeled isotopes is essential for generating accurate mass distribution vectors (MDVs) for metabolites of interest [2].

Computational Flux Analysis

Flux Estimation and Model Solution

The core computational step involves deducing metabolic flux parameters through nonlinear regression to best fit the experimentally measured isotope labeling patterns and external rate data [3]. The complexity of this problem has led to the development of specialized computational tools that implement various algorithms.

Table 3: Software Tools for 13C-MFA

| Software Name | Capabilities | Key Algorithm | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX2 [2] | Steady-state 13C-MFA | EMU | UNIX/Linux |

| Metran [2] | Steady-state 13C-MFA | EMU | MATLAB |

| OpenFLUX2 [2] | Steady-state 13C-MFA | EMU | Multiple |

| INCA [2] | Steady-state 13C-MFA | EMU | MATLAB |

| Iso2Flux [5] | Steady-state 13C-MFA with parsimonious optimization | EMU | Multiple |

| FiatFLUX [2] | Steady-state 13C-MFA | Not specified | Multiple |

The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework has revolutionized 13C-MFA by decomposing complex metabolic networks into basic units for modular analysis, significantly simplifying the modeling and solution process [2] [3]. This framework selects the smallest metabolite subsets that preserve the essential information needed to simulate isotopic labeling, dramatically reducing computational complexity compared to simulating entire metabolite pools [2].

Parsimonious 13C-MFA

A recent innovation in flux analysis is parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA), which runs a secondary optimization in the 13C-MFA solution space to identify the solution that minimizes the total reaction flux [5]. This approach can be particularly valuable when analyzing large metabolic networks or when working with limited sets of measurements, situations common in plant research. Furthermore, flux minimization can be weighted by gene expression measurements, enabling seamless integration of transcriptomics data with 13C labeling data [5].

Statistical Analysis and Validation

Ensuring the reliability of flux estimates requires rigorous statistical validation [3] [4]:

- Residual Sum of Squares (SSR) Evaluation: SSR reflects the deviation between model predictions and experimental data, with smaller values indicating better fit [3]. The minimized SSR should follow a χ² distribution, allowing statistical testing of model goodness-of-fit.

- Confidence Interval Calculation: Uncertainty in flux estimates can be quantified through sensitivity analysis (evaluating how small changes in flux parameters affect SSR) or Monte Carlo simulation (generating flux solution distributions through random sampling) [3].

- χ²-test of Goodness-of-Fit: The most widely used quantitative validation approach in 13C-MFA, though researchers should be aware of its limitations and complement it with other validation forms [4].

If statistical tests indicate poor model fit, researchers should investigate potential issues including incomplete metabolic models, incorrect reaction reversibility settings, measurement errors, or insufficient quality of isotopic labeling data [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Cell 13C-MFA

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C] Glucose | Primary carbon tracer for high-resolution flux analysis | Provides optimal flux resolution for central carbon metabolism [3] |

| Strictly Minimal Medium | Maintains controlled labeling conditions | Must contain only the selected 13C-labeled substrate as sole carbon source [2] |

| Derivatization Reagents (TBDMS, BSTFA) | Render metabolites volatile for GC-MS analysis | Essential for preparation of proteinogenic amino acids for isotopic analysis [2] |

| Internal Standards | Enable precise quantification of metabolite levels | Critical for accurate mass isotopomer distribution measurements [6] |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits | Measure extracellular uptake/secretion rates | Provide essential constraints for flux models [4] |

| QC-MS Reference Standards | Instrument calibration and data quality control | Ensure reproducibility across multiple experiments [2] |

| 3-(Pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-enamide | 3-(Pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-enamide | RUO | Supplier | 3-(Pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-enamide for research. Explore its applications in kinase & cancer studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| (4-Nitro-benzyl)-phosphonic acid | (4-Nitro-benzyl)-phosphonic Acid | High Purity | (4-Nitro-benzyl)-phosphonic acid for RUO. A phosphatase & kinase research tool. High-purity, for biochemical studies only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. |

Integration with Constraint-Based Models for Plant Research

The integration of 13C-MFA with constraint-based models, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), creates a powerful framework for plant metabolic engineering and systems biology [4]. This integration can be implemented through several approaches:

Figure 2: Iterative framework for integrating 13C-MFA with constraint-based modeling to develop predictive metabolic models for plant systems.

- Model Validation and Refinement: 13C-MFA provides experimental validation for FBA predictions, particularly for central carbon metabolism fluxes [4]. Discrepancies between predicted and measured fluxes can identify gaps in metabolic network annotations or regulatory effects not captured by stoichiometric models alone.

- Solution Space Reduction: 13C-MFA flux maps can constrain the feasible solution space in FBA, greatly improving the accuracy of genome-scale flux predictions [4] [5].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Advanced approaches like p13CMFA enable the integration of transcriptomic data with 13C labeling data, providing a more comprehensive view of metabolic regulation [5].

For plant research, this integrated approach is particularly valuable for understanding metabolic adaptations to environmental stresses, optimizing the production of valuable plant-derived compounds, and engineering crop species for improved yield and sustainability.

13C-MFA provides a powerful platform for quantifying metabolic fluxes in plant cells, offering unique insights into the dynamic operation of metabolic networks. From carefully designed tracer experiments to sophisticated computational analysis, the methodology enables researchers to move beyond static metabolic maps to quantitative flux distributions that reflect the integrated functional state of plant metabolic systems. The continuing development of 13C-MFA technologies—including instationary approaches, parsimonious flux analysis, and enhanced statistical validation—promises to further expand applications in plant research. When integrated with constraint-based modeling frameworks, 13C-MFA becomes an essential component of plant systems biology, enabling predictive manipulation of plant metabolism for agricultural and biotechnological applications.

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) provides a powerful systems biology framework to investigate metabolic states and define genotype-phenotype relationships through the integration of multi-omics data [7]. These methods utilize mathematical representations of biochemical reactions, gene-protein-reaction associations, and physiological constraints to build and simulate metabolic networks. The core principle involves defining a "solution space" containing all possible metabolic flux maps that are consistent with specified physicochemical and biological constraints, then identifying biologically relevant states within this space [4]. For plant research, these approaches are particularly valuable due to the complexity of plant metabolic networks, which feature extensive compartmentalization, parallel metabolic pathways, and sophisticated transport systems [8] [9].

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) form the computational backbone of constraint-based modeling. These models are structured reconstructions of an organism's entire metabolic network, derived from genome annotations and experimental data [7]. A GEM consists of mass-balanced metabolic reactions, gene-protein associations that map relationships between genes and the proteins catalyzing each reaction, and compartmentalization information that reflects the subcellular organization of metabolism [7]. The integration of 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) with constraint-based models has emerged as a particularly powerful approach for plant systems biology, combining the predictive power of modeling with experimental validation of intracellular fluxes [4].

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Flux Balance Analysis is a constraint-based approach that uses linear programming to predict the distribution of metabolic fluxes throughout a network under steady-state conditions [10]. FBA operates on several key assumptions: the system is at metabolic steady-state (metabolite concentrations and reaction rates are constant), mass-balance constraints must be satisfied, and reaction fluxes are constrained by upper and lower bounds [4]. The mathematical formulation of FBA centers on the stoichiometric matrix S, where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. At steady state, the system is described by the equation:

Sv = 0

where v is the vector of reaction fluxes. This equation is subject to flux constraints:

vlb ≤ v ≤ vub

FBA identifies a flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes an objective function, typically formulated as:

Z = c^T v

where c is a vector of weights indicating how each reaction contributes to the objective [7]. The most commonly used objective function is the biomass objective function (BOF), which maximizes biomass production efficiency (growth rate) by representing biomass as a reaction consuming all necessary biomass precursors in their appropriate ratios [9].

Table 1: Key Components of Constraint-Based Metabolic Models

| Component | Description | Role in Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | m × n matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions | Defines mass-balance constraints: Sv = 0 at steady state |

| Flux Vector (v) | n-dimensional vector of reaction fluxes | Variables to be solved in the optimization |

| Objective Function (Z) | Linear combination of fluxes to be optimized (e.g., biomass production) | Defines biological objective to identify relevant flux distributions |

| Flux Constraints | Lower and upper bounds for reaction fluxes (vlb, vub) | Incorporates thermodynamic and capacity constraints |

| Biomass Reaction | Pseudo-reaction consuming all biomass precursors | Represents biomass composition and growth requirements |

| Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) | Boolean rules linking genes to reactions | Incorporates regulatory information |

Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions are structured knowledge bases that convert genomic information into a mathematical representation of metabolism [7]. The reconstruction process involves four key stages: (1) Draft Reconstruction - generating an initial network from genome annotation and biochemical databases; (2) Network Refinement - manual curation to fill gaps and remove incorrect annotations; (3) Conversion to Model - adding constraints and objective functions; and (4) Validation - comparing model predictions with experimental data [8].

For plant metabolic models, several specialized challenges arise due to extensive subcellular compartmentalization (plastids, mitochondria, peroxisomes, vacuoles), parallel metabolic pathways in different compartments, and complex transport processes [8] [9]. Plant models must also account for source-sink interactions between different plant organs and tissues, which change dynamically throughout development [11].

Table 2: Evolution of Plant Metabolic Models and Their Applications

| Model Type | Key Features | Applications in Plant Research | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell/Tissue Models | Focus on metabolism of specific cell types or tissues | Study of specialized metabolism in specific tissues | Barley seed model [12], Arabidopsis leaf model [11] |

| Multi-Organ Models | Integration of multiple organ-specific models | Analysis of source-sink interactions and carbon partitioning | Barley multiorgan model [11] |

| Dynamic FBA Models | Integration of FBA with dynamic constraints | Study of metabolic shifts during development and environmental changes | Whole-plant barley model [11] |

| Multi-Omics Integrated Models | Incorporation of transcriptomic, proteomic, or metabolomic data | Context-specific model construction and analysis of regulatory mechanisms | Proteome-constrained models [10] |

Integration of 13C-MFA with Constraint-Based Models

Fundamentals of 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is an analytical methodology that quantifies intracellular metabolic fluxes by combining experimental isotopic labeling data with computational modeling [1]. In 13C-MFA, organisms are fed with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose or [U-13C]glucose), and the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites are measured using mass spectrometry or NMR techniques [4] [1]. These labeling patterns depend on the operation of metabolic pathways and thus provide information about intracellular fluxes.

The core computational problem in 13C-MFA involves finding the flux map that minimizes the difference between measured and simulated isotopic labeling patterns:

argmin: (x - xM)Σε(x - x_M)^T

subject to: S·v = 0, M·v ≥ b

where x is the vector of simulated isotopic labeling, xM is the experimentally measured labeling, Σε is the covariance matrix of measurements, S is the stoichiometric matrix, v is the flux vector, and M·v ≥ b provides additional physiological constraints [1]. 13C-MFA can be classified into three main categories based on the system's state: Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) for systems where fluxes, metabolites, and labeling are constant; Isotopically Nonstationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA) for systems where labeling is changing; and Metabolically Nonstationary 13C-MFA for systems where fluxes, metabolites, and labeling are all variable [1].

Synergistic Integration for Plant Metabolism Research

The integration of 13C-MFA with constraint-based models creates a powerful synergistic relationship that enhances both approaches [4]. 13C-MFA provides experimental validation of FBA predictions, thereby increasing confidence in model-derived fluxes. Conversely, FBA and other constraint-based methods can guide the design of 13C-MFA experiments by identifying key fluxes that need to be resolved and predicting optimal tracer strategies [4]. For plant metabolism, this integration is particularly valuable for understanding compartmentalized metabolism, as 13C-labeling data can help resolve fluxes between cytosol, plastids, mitochondria, and other organelles [8].

Recent advances have enabled more sophisticated integrations, including the incorporation of metabolite pool size information into INST-MFA and the development of parallel labeling experiments where multiple tracers are used simultaneously to improve flux resolution [4]. Statistical validation methods, particularly the χ²-test of goodness-of-fit, play a crucial role in evaluating the consistency between model predictions and experimental data, though recent work has highlighted limitations of this approach and proposed complementary validation methods [4].

Experimental Protocols and Computational Workflows

Protocol for Integrated 13C-MFA and FBA in Plant Systems

Phase 1: Experimental Design and Setup

Tracer Selection: Choose appropriate 13C-labeled substrates based on the metabolic pathways of interest. For plant central carbon metabolism, common tracers include [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, and 13COâ‚‚ [1]. For parallel labeling experiments, use multiple tracers simultaneously to improve flux resolution [4].

Plant Culture and Labeling: Grow plant material under controlled environmental conditions. For steady-state MFA, ensure metabolic and isotopic steady state by maintaining labeling for sufficient time (typically several generation times for cell cultures) [1]. For INST-MFA, implement rapid sampling during the labeling time course [1].

Sampling and Quenching: Rapidly collect and quench metabolism using appropriate methods (e.g., liquid nitrogen freezing). Collect sufficient biological replicates for statistical power [1].

Phase 2: Analytical Measurements

Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol:water:chloroform mixtures) while maintaining isotopic integrity [1].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

Data Processing: Convert raw mass spectrometric data to corrected MIDs using appropriate software tools (e.g., iMS2Flux, Flux-P) [12].

Phase 3: Computational Flux Analysis

Model Preparation:

- Define metabolic network structure with atom mappings for 13C-MFA

- Set constraints based on measured extracellular fluxes

- Define biomass composition for relevant plant tissue [9]

Flux Estimation:

- For 13C-MFA: Solve the optimization problem to minimize difference between simulated and measured MIDs

- For FBA: Solve linear optimization problem to maximize objective function

- Use appropriate software tools (see Section 5)

Statistical Evaluation:

- Perform goodness-of-fit testing (χ²-test)

- Calculate confidence intervals for flux estimates

- Validate models using complementary approaches [4]

Protocol for Multi-Organ Plant Metabolic Modeling

Phase 1: Organ-Specific Model Reconstruction

Organ Selection: Identify key organs relevant to the research question (e.g., leaves, stems, seeds, roots) [11].

Network Reconstruction:

- Compile organ-specific metabolic reactions from biochemical literature and databases

- Incorporate organelle-specific metabolism for each organ

- Define organ-specific biomass reactions based on experimental composition data [11]

Model Validation:

- Compare simulation results (e.g., predicted uptake/excretion rates) with experimental data

- Validate pathway patterns against literature knowledge [11]

Phase 2: Whole-Plant Model Integration

Transport Reaction Definition: Specify metabolic transport processes between organs based on physiological knowledge [11].

Dynamic Constraints: Integrate with whole-plant functional models to incorporate carbon and nitrogen partitioning dynamics [11].

Simulation and Analysis:

- Perform dynamic FBA to simulate metabolic behavior throughout development

- Analyze source-sink interactions and metabolic trade-offs [11]

Computational Tools and Research Reagents

The COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) framework provides a comprehensive set of methods for metabolic network analysis, with software implementations available in both MATLAB and Python [7]. The open-source Python ecosystem has rapidly developed to provide accessible tools for constraint-based modeling.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Constraint-Based Modeling and 13C-MFA

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Plant Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | Core constraint-based modeling | Simulation of plant metabolic networks | Object-oriented representation, multiple solver interfaces, FBA and FVA [7] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based constraint-based analysis | Plant metabolic model development and simulation | Comprehensive method collection, community-supported [7] |

| MEMOTE | Model quality assessment | Quality control for plant metabolic models | Automated testing, GitHub integration [7] |

| iMS2Flux | Processing of MS data for 13C-MFA | High-throughput flux analysis in plants | Automated processing of stable isotope MS data [12] |

| Flux-P | Automated metabolic flux analysis | Streamlining 13C-MFA workflows | Laboratory automation integration [12] |

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Uses in Plant Metabolic Research |

|---|---|---|

| [1-13C]Glucose | Isotopic tracer for central carbon metabolism | Mapping glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway fluxes [1] |

| [U-13C]Glucose | Uniformly labeled tracer for comprehensive flux mapping | Analysis of TCA cycle and anaplerotic fluxes [1] |

| 13COâ‚‚ | Photosynthetic carbon fixation studies | Analysis of photosynthetic metabolism and photorespiration [8] |

| GC-MS Platform | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions | Quantitative analysis of isotopic labeling in plant metabolites [1] |

| LC-MS/MS Platform | Tandem MS for positional isotopomer analysis | Enhanced resolution of isotopic labeling patterns [4] |

| Metabolic Databases | Network reconstruction and validation | Access to pathway information (e.g., PlantCyc, MetaCrop) [8] |

The integration of 13C-MFA with constraint-based models represents a powerful paradigm for advancing plant metabolic research. This synergistic approach combines the predictive capabilities of genome-scale models with the experimental validation provided by 13C-flux measurements, enabling more accurate and comprehensive understanding of plant metabolic networks [4]. For plant biology specifically, these integrated approaches are essential for addressing the unique challenges of compartmentalized metabolism, source-sink interactions, and dynamic metabolic shifts during development and environmental responses [11] [8].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) enhanced statistical methods for model validation and selection that address limitations of current approaches like the χ²-test [4]; (2) incorporation of additional omics data layers (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to create more context-specific models [10]; (3) development of multi-scale models that integrate metabolism with regulatory networks and physiological processes [11]; and (4) continued improvement in computational tools to make these methods more accessible to the broader plant research community [7]. As these methodologies mature, they will play an increasingly important role in guiding metabolic engineering strategies for crop improvement and bio-based production of valuable plant compounds [10] [8].

In the quest to understand the complex metabolic networks that underpin plant growth, development, and stress responses, plant systems biology has embraced two powerful computational frameworks: 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Constraint-Based Models (CBMs). While each approach offers unique insights, their integration provides a more complete picture of plant metabolic function than either can deliver alone. 13C-MFA uses isotopic tracers to quantify actual in vivo metabolic flux distributions, offering an experimental snapshot of pathway activities [1] [2]. In parallel, CBMs—including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) analysis—use mathematical constraints to define all theoretically possible flux states of a metabolic network [13] [4]. For plant researchers investigating everything from crop productivity to specialized metabolite biosynthesis, combining these approaches creates a synergistic framework where experimental quantification validates and refines theoretical predictions, while structural analysis guides experimental design and interpretation. This integration is particularly vital for plant systems, where compartmentalization, metabolic plasticity, and complex source-sink relationships create unique analytical challenges [14] [15]. This article details protocols and applications for effectively marrying these methodologies to advance plant research.

Background: Core Concepts and Their Complementary Nature

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

13C-MFA is a powerful experimental technique that quantifies the in vivo rates of metabolic reactions through the use of 13C-labeled substrates and sophisticated computational modeling. The fundamental principle involves feeding cells or tissues a precisely labeled carbon source (e.g., [1-13C] glucose), then tracking how these labels incorporate into and distribute among downstream metabolites [2] [1]. The measured isotopic labeling patterns—detected via Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)—serve as constraints to calculate metabolic fluxes that best explain the observed data [1] [2]. The workflow can be applied under both isotopic stationary (SS-MFA) and non-stationary (INST-MFA) conditions, with the latter being particularly valuable for photosynthetic studies where the rapid kinetics of 13CO2 incorporation can be monitored [1] [16].

Table 1: Classification of 13C-Metabolic Fluxomics Methods

| Method Type | Applicable Scene | Computational Complexity | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Fluxomics | Any system | Easy | Provides only local, qualitative flux information |

| 13C Flux Ratios | Systems with constant fluxes and labeling | Medium | Provides only local, relative quantitative values |

| Stationary 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) | Systems with constant fluxes and labeling | Medium | Not applicable to dynamic systems |

| Instationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA) | Systems with constant fluxes but variable labeling | High | Not applicable to metabolically dynamic systems |

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM)

CBMs represent a top-down approach to metabolic network analysis. These models are built on the stoichiometric matrix of all known biochemical reactions in an organism. The core constraint is the assumption of steady-state metabolism, where metabolite concentrations do not change over time, leading to the mass balance equation: S · v = 0 [4]. Additional constraints based on enzyme capacities, nutrient uptake rates, and thermodynamic feasibility further restrict the solution space. Within this bounded space, different analytical techniques are applied:

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Uses linear programming to find a flux distribution that optimizes a specified biological objective (e.g., biomass maximization) [4].

- Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) Analysis: Identifies all minimal, genetically independent metabolic pathways that can operate within the network [13].

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): Determines the minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction subject to the constraints [4].

The Synergistic Framework

The true power of integration emerges from the complementary strengths and weaknesses of each approach. 13C-MFA provides highly accurate, quantitative flux estimates for core metabolic pathways but is typically limited to central carbon metabolism due to experimental and computational constraints [2]. CBMs can encompass genome-scale metabolic networks but produce predictions that may not reflect in vivo conditions without experimental validation [4] [13]. When integrated, 13C-MFA flux maps can be used to validate and refine CBM predictions, while EFM analysis can identify feasible pathways to target with 13C-MFA experiments [13]. This synergy creates a powerful cycle of hypothesis generation and experimental testing.

Figure 1: Synergistic Integration of 13C-MFA and CBMs. The combination of theoretical network analysis (CBM) with experimental flux measurement (13C-MFA) produces more accurate and predictive metabolic models.

Integrated Workflows and Protocols

Protocol 1: Coupling EFM Analysis with 13C-MFA for Plant Embryo Systems

This protocol outlines the process of using EFM analysis to inform the design of 13C-MFA experiments, as applied to Brassica napus (rapeseed) embryos [13] [17].

Step 1: Network Reconstruction and EFM Computation

- Compile a stoichiometric model of central carbon metabolism including glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle, and biosynthetic pathways to storage reserves (oils, proteins).

- Define input/output metabolites (e.g., glucose, glutamine, alanine, O2, CO2, biomass precursors).

- Use computational tools like CellNetAnalyzer or METATOOL to calculate all Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs). For a B. napus network of 26 reactions, this typically yields 51 EFMs [13].

Step 2: Calculation of Flux Efficiency Coefficients

- For each reaction in the network, calculate a flux efficiency coefficient based on its participation in the complete set of EFMs. This metric reflects the structural importance of a reaction across all possible metabolic states [13].

- Compare efficiency coefficients between different nutritional conditions (e.g., inorganic vs. organic nitrogen sources) to predict which fluxes are most likely to change.

Step 3: Experimental 13C-MFA Validation

- Design 13C-labeling experiments based on EFM predictions. For B. napus, cultures were supplied with [13C] glucose combined with different nitrogen sources [13] [17].

- Quench metabolism, extract metabolites, and derive Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) of proteinogenic amino acids via GC-MS.

- Use software platforms like 13CFLUX2 or OpenFLUX to compute the flux map that best fits the experimental MIDs [1] [2].

Step 4: Comparative Analysis and Model Refinement

- Statistically compare the relative changes in measured fluxes from 13C-MFA with the predicted changes in flux efficiency coefficients from EFM analysis.

- A strong positive correlation validates that the network structure captured by EFMs reflects biological reality. Discrepancies indicate areas where regulatory constraints dominate and require model refinement [13].

Protocol 2: INST-MFA for Photosynthetic Metabolism with a Regression-Based Flux Estimation

This protocol describes INST-MFA for the Calvin-Benson Cycle (CBC) in microalgae, incorporating a Simulation-Free Constrained Regression (SFCR) approach to simplify computation [16].

Step 1: Dynamic 13CO2 Labeling and Sampling

- Grow photoautotrophic cultures (e.g., Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) under controlled light and CO2 conditions.

- Introduce a rapid pulse of 13CO2 at time t=0.

- Collect samples at high temporal resolution (seconds to minutes) over the initial labeling period to capture isotopic non-stationarity [16].

Step 2: Metabolite Quenching, Extraction, and MID Measurement

- Rapidly quench metabolism (e.g., using cold methanol).

- Extract polar metabolites and analyze via LC-MS/MS to measure the Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) of all CBC intermediates (e.g., RuBP, 3PGA, G3P, FBP) [16].

Step 3: SFCR Flux Estimation

- Formulate the flux estimation as a constrained regression problem, avoiding the need for repeated ODE simulation.

- Discretize the system using Forward Euler approximation, converting it to a system of linear equations: P·(x(tᵢ+Δtᵢ) - x(tᵢ)) = S(tᵢ)·v·Δtᵢ, where P is the pool size matrix, x is the MID vector, S is the stoichiometric matrix, and v is the flux vector [16].

- Solve the quadratic programming problem to find the flux distribution v that minimizes the difference between predicted and measured MID dynamics.

Step 4: Model Selection and Flux Validation

- Compare the goodness-of-fit for different model variants (e.g., with/ without metabolite compartmentation in the chloroplast and cytosol).

- Validate SFCR flux estimates against those from established INST-MFA software like INCA, with a typical target correlation of râ‚› > 0.89 [16].

Figure 2: Workflow for Simulation-Free Constrained Regression (SFCR) in INST-MFA. This approach formulates flux estimation as a single regression problem, bypassing the computational cost of repeated ODE simulation [16].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful integration of 13C-MFA and CBMs relies on a suite of specialized reagents and software.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C] Glucose | Doubly-labeled carbon tracer for 13C-MFA | Elucidating flux through Pentose Phosphate Pathway vs. Glycolysis in plant embryos [13] [18]. |

| 13C-Sodium Bicarbonate | Tracer for photosynthetic INST-MFA | Quantifying carbon fixation flux through the Calvin-Benson Cycle in microalgae and plants [16]. |

| TBDMS / BSTFA | Derivatization agents for GC-MS | Rendering amino acids volatile for isotopic analysis to infer labeling of central metabolic intermediates [2]. |

| Custom Minimal Media | Strictly controlled nutrient environment | Ensuring the 13C-labeled substrate is the sole carbon source for definitive flux tracing [2] [18]. |

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Platforms

| Software / Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Applicable Model Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX2 | 13C-MFA Flux Estimation | Uses EMU algorithm, efficient for complex networks [2]. | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, Plant Tissues |

| INCA | INST-MFA & SS-MFA | Integrates compartmentalized models, user-friendly interface [16]. | Cyanobacteria, Microalgae, Plants |

| CellNetAnalyzer / METATOOL | EFM Analysis & CBM | Calculates elementary flux modes, pathway analysis [13]. | C. glutamicum, B. napus |

| OpenFLUX | 13C-MFA Flux Estimation | Flexible, open-source platform for flux estimation [2]. | E. coli, B. subtilis |

Application Notes: Case Studies in Plant Systems

Case Study 1: Engineering Cyanobacteria for Bio-production

Objective: To understand how disruption of the respiratory chain affects CO2 fixation and energy metabolism in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, with the goal of improving bio-production [18].

Integrated Approach:

- A mutant strain (ΔndhF1) with a deleted subunit of the NDH-1 complex (involved in cyclic electron transport) was constructed.

- Both wild-type and mutant strains were cultured with [1,2-13C] glucose and NaHCO3 under photoautotrophic conditions.

- 13C-MFA was performed to quantify absolute metabolic fluxes, including the CO2 fixation rate by RuBisCO.

- Flux distributions were used to calculate the consumption and regeneration rates of ATP and NAD(P)H, linking central metabolism to photosystem function.

Key Findings:

- The ΔndhF1 strain showed a greater than 50% decrease in the CO2 fixation flux and a corresponding decrease in the regeneration of ATP and NADPH by the photosystem.

- Contrary to expectations, the ATP/NAD(P)H production ratio remained unchanged, suggesting the mutant retained a capacity for cyclic electron transfer via alternative pathways.

- Synergistic Insight: 13C-MFA provided quantitative proof of a metabolic bottleneck, while knowledge of the network structure (CBM) was essential for interpreting the energetic coupling between photosynthesis and metabolism. This guides future engineering strategies to bypass this bottleneck [18].

Case Study 2: Multi-Omics Integration for Drought Tolerance in Cassava

Objective: To elucidate systemic metabolic responses to drought in cassava (Manihot esculenta) leaves [14].

Integrated Approach:

- Transcriptome and metabolome data were collected from cassava under well-watered and drought conditions.

- A constraint-based model of leaf metabolism was constructed and contextualized with the omics data.

- The model was used to simulate metabolic behavior and identify key regulatory nodes under drought.

Key Findings:

- The model predicted phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) to be a pivotal enzyme under drought, facilitating CO2 concentration for RuBisCO and ultimately enhancing sugar production for osmotic adjustment.

- Synergistic Insight: The CBM generated a testable hypothesis about PEPC's role. This can now be followed up with targeted 13C-MFA experiments to directly quantify the flux through PEPC and the associated pathways, validating the model prediction and solidifying PEPC's status as a candidate for improving abiotic stress tolerance [14].

The integration of 13C-MFA and constraint-based modeling represents a paradigm shift in plant metabolic research. This powerful synergy moves beyond the limitations of single approaches, enabling researchers to build quantitatively accurate, predictive models of plant metabolism. As protocols become more standardized and computational tools more accessible, this integrated framework is poised to drive breakthroughs in fundamental plant science and accelerate the development of crops with enhanced yield, nutritional value, and resilience to environmental stress.

Application Notes

This document provides a detailed framework for studying the unique challenges in plant metabolism, with a specific focus on integrating 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) with Constraint-Based Models (CBMs). Plant metabolic engineering and systems biology face distinct hurdles due to the compartmentalization of pathways, the occurrence of photorespiration, and the complexities of autotrophic carbon fixation. Effectively combining experimental 13C-MFA with computational CBM provides a powerful approach to overcome these challenges, yielding quantitative insights into in vivo metabolic flux distributions that can inform rational engineering strategies [4] [19].

The Challenge of Cellular Compartmentalization

Plant metabolic networks are highly compartmentalized, with biochemical steps of a single pathway often distributed across multiple subcellular locations such as the chloroplast, mitochondria, peroxisome, and cytosol [20] [21]. This compartmentalization presents a significant challenge for metabolic engineering.

- Precursor Availability: Parallel biochemical pathways in different compartments can create independent precursor pools. For example, the cytosolic mevalonic acid (MVA) and the plastidic methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways both produce isoprenoid precursors, but carbon flux through them is independently regulated [21]. Successful engineering requires targeting enzymes to the compartment with the most abundant precursor pool.

- Enzyme Targeting: Strategic re-targeting of enzymes, including non-endogenous enzymes from bacteria or yeast, to specific organelles has proven successful in enhancing product yield [21].

- Role of Transporters: Metabolite transporters are integral components of metabolic pathways, facilitating the directional movement of intermediates across organellar membranes. Their identification and characterization are central to effective engineering [21].

Integrating compartmentalization into metabolic models is crucial. The reconstruction of compartmentalized metabolic network models for plants will greatly advance the ability to predict engineering outcomes [20] [21].

Photorespiration as a Metabolically Essential Process

Photorespiration, often considered a wasteful process due to its consumption of energy and release of previously fixed COâ‚‚, is now recognized as essential for plant metabolism and stress protection [22] [23]. It is initiated by the oxygenase activity of Rubisco and involves a complex pathway spanning the chloroplast, peroxisome, and mitochondria [23].

- Physiological Roles: Photorespiration is crucial for:

- Nitrogen and Sulfur Assimilation: It provides key intermediates and reducing power for these essential processes [22].

- Abiotic Stress Response: It acts as an energy sink, protecting the photosynthetic apparatus from photooxidation under high light, drought, and other stress conditions [22].

- Redox Homeostasis: It helps manage cellular redox balance by consuming ATP and NADPH [22].

- Engineering Approaches: While complete disruption of photorespiration is detrimental, engineering optimized photorespiratory bypasses has successfully increased biomass and seed yield in model plants and crops like tobacco and rice [22].

Probing Autotrophic Metabolism

Autotrophy, the ability to convert abiotic energy and COâ‚‚ into organic compounds, is a fundamental feature of plants [24]. Quantifying fluxes in autotrophic tissues (e.g., photosynthesizing leaves) presents specific technical challenges.

- Instationary MFA (INST-MFA): Traditional 13C-MFA, which relies on steady-state isotopic labeling, is not suitable for autotrophic metabolism in the light. Instead, INST-MFA must be used. This method tracks the time-dependent passage of 13C-label from a substrate like 13COâ‚‚ through metabolic pools that have not reached isotopic steady state, allowing for the quantification of fluxes in active photosynthetic tissue [19].

- Modeling Autotrophy: Constraint-Based models of plant metabolism must account for the diurnal cycle and the interactions between light and dark metabolism. Diel (day-night) flux balance models have been developed to capture these dynamics in C3 and CAM plants [19].

Protocols

Protocol 1: Compartment-Specific Metabolite Profiling for Constraining Models

Objective: To isolate organelles and profile their metabolite contents, generating quantitative data for the development and validation of compartmentalized metabolic models.

Introduction: Advances in metabolomics are key to understanding compartmentalized metabolism. This protocol outlines a non-aqueous density gradient centrifugation method for the isolation of organelles for subsequent metabolite analysis [21].

Materials:

- Liquid Nitrogen

- Non-aqueous solvent (e.g., heptane/toluene mixture)

- Density gradient medium (e.g., Percoll or customized non-aqueous solvents)

- Ultracentrifuge and fixed-angle or swinging-bucket rotors

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) system

Procedure:

- Rapid Harvest and Quenching: Flash-freeze plant leaf tissue (≥1 g) in liquid nitrogen to instantly halt metabolic activity.

- Freeze-Drying: Lyophilize the frozen tissue to remove all water.

- Tissue Disruption: Gently grind the freeze-dried tissue into a fine powder in a dry, cold environment to preserve organelle integrity.

- Density Gradient Centrifugation:

- Re-suspend the powder in a light non-aqueous solvent.

- Layer this suspension onto a pre-formed, discontinuous density gradient.

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 50,000 x g for 30-60 min) to separate organelles based on their buoyant densities.

- Fraction Collection: Carefully collect distinct bands from the gradient, which correspond to enriched organelle fractions (e.g., chloroplasts, mitochondria).

- Metabolite Extraction and Analysis:

- Extract metabolites from each fraction using a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol:chloroform:water).

- Derivatize extracts for analysis by GC-MS.

- Identify and quantify metabolites by comparing retention times and mass spectra to authentic standards.

Data Integration: The quantified, compartment-specific metabolite pool sizes can be used as additional constraints in 13C-MFA, improving the resolution and statistical confidence of flux estimates [4].

Protocol 2: INST-MFA for Quantifying Fluxes in Photosynthetic Leaf Tissue

Objective: To measure metabolic flux rates in autotrophic plant tissue under illumination by performing instationary 13C-labeling experiments.

Introduction: Standard 13C-MFA requires isotopic steady state, which is not achieved in photosynthetic metabolism during short-term labeling. INST-MFA fits time-course labeling data to a kinetic model to estimate metabolic fluxes [19].

Materials:

- 13CO₂ (≥99% atom enrichment)

- Environmental-controlled leaf chamber (regulating light, temperature, humidity)

- Automated gas-handling system

- Liquid Nitrogen

- GC-MS or LC-MS system

Procedure:

- System Setup: Place a leaf or whole plant (e.g., Arabidopsis) inside a sealed, environmentally controlled chamber. Connect the chamber to a gas flow system delivering air with a defined, low COâ‚‚ concentration.

- 13C-Pulse Initiation: Rapidly switch the COâ‚‚ source from unlabeled (12COâ‚‚) to 13COâ‚‚. Precisely record this as time zero.

- Time-Course Sampling: At defined time intervals (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 300 seconds), quickly harvest leaf discs or tissue pieces and immediately freeze them in liquid nitrogen.

- Metabolite Extraction: Grind the frozen tissue and extract polar metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the extracts using GC-MS or LC-MS to measure the relative abundances of mass isotopomers for key metabolites (e.g., 3-phosphoglycerate, sugar phosphates, malate, glycine, serine).

- Computational Flux Estimation:

- Use a computational model of the metabolic network that includes atom transitions and metabolite pool sizes.

- Fit the model to the measured time-dependent mass isotopomer data to estimate the flux values that best explain the observed labeling kinetics.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Metabolites and Enzymes in the Photorespiratory Pathway

| Metabolite/Enzyme | Subcellular Location | Primary Function/Role in Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Phosphoglycolate (2PG) | Chloroplast | Toxic product of RuBP oxygenation; pathway initiator [22]. |

| Glycolate | Chloroplast/Peroxisome | Transport form of 2PG after dephosphorylation [23]. |

| Glycine | Peroxisome/Mitochondria | Product of glycolate oxidation; condensed in mitochondria [22]. |

| Serine | Mitochondria/Peroxisome | Produced from glycine; returns amino group to the system [22]. |

| Rubisco | Chloroplast | Dual-function enzyme (carboxylase/oxygenase) initiating both photosynthesis and photorespiration [22] [23]. |

| Glycolate Oxidase | Peroxisome | Oxidizes glycolate to glyoxylate [22]. |

| GDC (Glycine Decarboxylase) | Mitochondria | Multi-enzyme complex that decarboxylates glycine, releasing CO₂ and NH₃ [22]. |

Table 2: Experimental Design for 13C-Labeling in Plant MFA

| Growth Condition | Recommended Tracer | Primary Application / Resolved Fluxes | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoautotrophic | 13COâ‚‚ | Calvin-Benson Cycle, Photorespiration, Sucrose Synthesis [19] | Requires INST-MFA protocol due to lack of isotopic steady state in the light. |

| Heterotrophic | [1-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose | Glycolysis, Pentose Phosphate Pathway, TCA Cycle [19] | Standard 13C-MFA applicable. Tracer combination in parallel labeling experiments improves flux precision [4]. |

| Photo-mixotrophic | 13COâ‚‚ or 13C-Glucose | Interaction between light- and dark-driven metabolism [19] | Choice of tracer depends on the specific metabolic cross-talk under investigation. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

Photorespiration spans three organelles

Integrating 13C-MFA with CBMs

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Metabolic Flux Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracers for elucidating intracellular metabolic pathways. | 13COâ‚‚: For photoautotrophic INST-MFA [19]. [U-13C]Glucose: For heterotrophic 13C-MFA in cell cultures or non-photosynthetic tissues [19]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Detection and quantification of metabolites and their isotopic labeling. | GC-MS / LC-MS: Essential for measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) in 13C-MFA [4]. Tandem MS (MS/MS): Can provide positional labeling information, improving flux resolution [4]. |

| Enzymes for Activity Assays | Validation of model predictions by measuring in vitro enzyme activities. | Rubisco: Quantifying carboxylase vs. oxygenase activity [22]. GDC/SHMT: Assessing photorespiratory capacity in mitochondria [22]. |

| Compartmentalized Metabolic Network Models | Computational framework for simulating and predicting metabolic behavior. | AraGEM (Arabidopsis): Genome-scale model for Arabidopsis thaliana [19]. C4GEM: Model for studying C4 plant metabolism [19]. |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) Software | Computational tool for estimating fluxes from time-course 13C-labeling data. | Required for flux analysis in photosynthetic tissues. Fits a kinetic model to time-dependent MIDs [19]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Software | Constraint-based modeling for predicting flux distributions at steady state. | COBRA Toolbox: A widely used MATLAB suite for CBM [4]. Used with genome-scale models to predict phenotypic outcomes. |

| (R)-2-Phenylpropylamide | (R)-2-Phenylpropylamide | High-Purity Chiral Reagent | High-purity (R)-2-Phenylpropylamide for research. A key chiral building block for asymmetric synthesis & medicinal chemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Benzamide, N,N,4-trimethyl- | Benzamide, N,N,4-trimethyl-, CAS:14062-78-3, MF:C10H13NO, MW:163.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Bridging the Gap: Methodologies for Integrating Experimental Flux Data into Plant Metabolic Models

Metabolic flux represents the integrated functional phenotype of a living system, emerging from multiple layers of biological organization and regulation [4]. In plant biology, understanding these fluxes is essential for guiding metabolic engineering strategies aimed at crop improvement and the production of valuable natural products [25]. The integration of 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) with constraint-based modeling approaches like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a powerful framework for quantifying and predicting metabolic flows in plants [4] [25].

This protocol details the workflow for combining experimental tracer studies with computational modeling to achieve a comprehensive understanding of plant metabolic networks. We focus specifically on applications in plant research, addressing the unique challenges posed by plant metabolic complexity, including subcellular compartmentalization and the interaction of distinct cell types [26] [25].

Background and Principles

Core Methodologies

- 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): An experimental approach that utilizes isotopes (typically 13C-labeled substrates) to trace the flow of carbon through metabolic networks. By measuring the incorporation of labels into metabolites via mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), intracellular reaction rates (fluxes) can be computationally estimated [26] [4] [25]. 13C-MFA is considered the gold standard for in vivo flux estimation [27].

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A constraint-based modeling method that predicts flux distributions in a metabolic network at steady state. It uses linear programming to optimize a biological objective function (e.g., biomass production) within the constraints imposed by stoichiometry and reaction capacities [28] [25]. FBA does not require kinetic parameters and is particularly useful for analyzing genome-scale metabolic models (GSMs) [28] [25].

The Rationale for Integration

While 13C-MFA provides accurate, quantitative flux estimates for core metabolic pathways, its coverage is often limited to central carbon metabolism due to experimental and analytical constraints [26] [4]. Conversely, FBA can analyze genome-scale networks but produces predictions that require experimental validation [4]. Integrating these approaches leverages their respective strengths: 13C-MFA generates high-quality flux maps for core pathways, which can then be used to validate and refine genome-scale FBA models, thereby enhancing the accuracy of system-wide flux predictions [4] [25].

Table 1: Comparison of 13C-MFA and FBA for Plant Metabolic Studies

| Feature | 13C-MFA | FBA |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Experimental flux estimation [4] | Flux prediction at steady-state [28] [25] |

| Network Coverage | Core metabolism (due to practical limitations) [26] | Genome-scale [28] [25] |

| Key Inputs | Isotopic labeling data, external rates [26] [25] | Stoichiometric model, objective function, constraints [28] |

| Key Output | Quantitative in vivo flux map [4] | Predicted optimal flux distribution [28] |

| Validation | Statistical goodness-of-fit tests (e.g., χ²-test) [4] | Comparison with experimental data (e.g., 13C-MFA fluxes) [4] |

Integrated Workflow Protocol

The following section outlines a standardized protocol for integrating 13C-MFA with constraint-based models, from experimental design to model validation.

Experimental Design and Tracer Experiments

Step 1: Define Biological Question and System

- Clearly articulate the scientific objective (e.g., understanding carbon partitioning in a specific tissue under stress) [25].

- Select the plant system and growth conditions, ensuring they can be maintained at a metabolic steady-state throughout the labeling experiment, which is a fundamental requirement for 13C-MFA [4].

Step 2: Select and Administer Isotopic Tracer

- Choose an appropriate 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., 13COâ‚‚, [U-13C]-glucose). The choice of tracer is critical and should be informed by the metabolic pathways under investigation [4] [27].

- For plants, 13COâ‚‚ labeling is widely used to study photosynthetic metabolism [25].

- Administer the tracer to the system, ensuring a rapid and complete switch from unlabeled to labeled substrate to achieve a well-defined labeling input.

Step 3: Sampling and Quenching of Metabolism

- Collect time-point samples for Isotopically Nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) or a single end-point sample for stationary MFA after isotopic steady state is reached [4] [27].

- Use rapid quenching techniques (e.g., immersion in cold methanol) to instantly halt metabolic activity and preserve the in vivo labeling patterns [27].

Metabolite Profiling and Data Acquisition

Step 4: Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

- Extract metabolites from quenched samples using suitable solvent systems (e.g., methanol-chloroform-water).

- Analyze the extracts using LC-MS/MS or GC-MS to quantify the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of intracellular metabolites [25] [27]. Tandem MS (MS/MS) can provide positional labeling information, enhancing flux resolution [4].

- Measure external fluxes, including substrate uptake rates, product secretion rates, and biomass accumulation rates [4] [25].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrate (e.g., 13COâ‚‚) | Serves as the tracer for metabolic pathways [26] [25] | Purity is critical; choice defines measurable fluxes. |

| Quenching Solvent (e.g., cold aqueous methanol) | Rapidly halts metabolic activity to preserve in vivo state [27] | Must be cold enough to instantly stop enzyme activity. |

| Extraction Solvents (e.g., methanol-chloroform) | Extracts polar and non-polar metabolites for MS analysis [25] | Composition affects metabolite coverage. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) Platform | Quantifies isotope labeling patterns and metabolite levels [26] [25] | LC-/GC-MS balance coverage, sensitivity, and throughput. |

Computational Flux Analysis and Model Integration

Step 5: 13C-MFA Flux Estimation

- Define a stoichiometric model of core metabolism, including atom transitions for each reaction.

- Use specialized software (e.g., 13CFLUX3 [27]) to simulate the expected MID data for a given flux map and fit the model to the experimental MIDs by varying the fluxes.

- The best-fit flux map is identified by minimizing the difference between simulated and experimental data [4] [25] [27].

Step 6: Genome-Scale Model (GSM) Construction and Curation

- Reconstruct or select a compartmentalized GSM for the target plant species (e.g., Arabidopsis, maize) [25]. This model should include all known metabolic reactions.

- Define constraints based on measured external fluxes and reaction reversibility [28].

Step 7: Integration and Validation of FBA Predictions

- Use the fluxes obtained from 13C-MFA for core metabolism to validate the predictions of the GSM [4].

- If discrepancies exist, the GSM may need refinement (e.g., adjusting reaction bounds, network topology, or the objective function) [4].

- The validated GSM can subsequently be used to predict system-wide flux distributions under different genetic or environmental conditions [25].

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow from tracer experiment to validated model (Max Width: 760px).

Data Analysis, Validation, and Model Selection

Statistical Validation and Uncertainty

- Goodness-of-fit Test: In 13C-MFA, the χ²-test is widely used to validate the model fit against the experimental labeling data [4]. A statistically acceptable fit indicates that the model is consistent with the data.

- Flux Uncertainty Estimation: Evaluate the confidence intervals of estimated fluxes using statistical methods such as Monte Carlo sampling or profile likelihoods [4] [27]. This identifies which fluxes are well-resolved by the data.

- Bayesian Methods: Emerging Bayesian approaches for 13C-MFA, including Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA), provide a robust framework for handling model selection uncertainty and multi-model flux inference [29]. This is particularly valuable for comparing alternative network architectures or regulatory hypotheses.

Model Selection and Refinement

Model selection is critical when multiple model configurations (e.g., different pathway topologies or objective functions) are plausible.

- For 13C-MFA, use statistical criteria to select the most parsimonious model that is supported by the data [4] [29].

- For FBA, test alternative biological objective functions (e.g., growth rate maximization, ATP minimization, or total flux minimization) and select the one whose predictions best align with 13C-MFA flux estimates or other physiological data [4] [25].

Diagram 2: Model validation and selection workflow (Max Width: 760px).

Concluding Remarks

The integration of 13C-MFA with constraint-based modeling represents a powerful paradigm in plant systems biology. This workflow, which moves iteratively from carefully designed tracer experiments to computationally-driven model predictions and validation, allows researchers to bridge the gap between detailed, accurate flux measurements in core metabolism and system-wide flux predictions [4] [25].

Future developments in this field will be driven by advances in high-performance computing tools like 13CFLUX(v3) [27], the adoption of Bayesian statistical methods for robust multi-model inference [29], and improved data integration frameworks that seamlessly combine phenotypic, fluxomic, and other omics data [30] [31]. For plant researchers, this integrated approach is indispensable for unraveling the complex regulation of plant metabolism and for guiding targeted engineering of crops for improved yield, sustainability, and resilience.

Incorporating 13C-MFA Flux Estimates as Additional Constraints in CBMs

The integration of 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) estimates with Constraint-Based Models (CBMs), such as Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), represents a powerful frontier in metabolic network modeling for plant research. While 13C-MFA uses isotopic tracer experiments to estimate intracellular metabolic fluxes, and FBA uses optimization of an objective function to predict fluxes under stoichiometric constraints, both methods assume a metabolic steady-state and provide values for reaction rates (fluxes) that cannot be measured directly [4]. Combining these approaches allows researchers to create more accurate and predictive models by incorporating empirically determined flux constraints into genome-scale stoichiometric models, thereby enhancing their biological relevance and predictive power [4] [1].

Background and Rationale

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a model-based technique that quantifies intracellular metabolic fluxes by leveraging data from 13C-labeling experiments [32]. Cells are cultured with 13C-labeled substrates, and the resulting isotopic patterns in metabolites are measured using mass spectrometry or NMR. A metabolic network model is then used to compute the flux distribution that best fits the experimental labeling data [1] [33]. Its key advantage is the ability to provide accurate, absolute estimates of in vivo flux for central metabolic pathways, including cycles and parallel routes [32].

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM), and specifically Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), is a computational approach used to predict metabolic behavior on a genome scale [4]. It operates by defining a solution space of all possible flux distributions that satisfy mass-balance constraints (the stoichiometric matrix) and capacity constraints on reaction rates. An objective function (e.g., biomass maximization) is typically chosen to identify a single optimal flux map from within this space [4].

The Need for Integration in Plant Research

Plant metabolic networks are complex, featuring extensive compartmentation and parallel pathways. FBA predictions for plants can be highly underdetermined, meaning the solution space is large and the identified flux map may not be physiologically relevant. Integrating flux constraints from 13C-MFA addresses this by:

- Constraining the Solution Space: Empirically measured fluxes from 13C-MFA directly reduce the range of possible flux solutions in the CBM, leading to more accurate and biologically realistic predictions [4].

- Validating and Selecting Model Architecture: Comparing FBA predictions against 13C-MFA estimates provides a robust method for testing different metabolic network structures or objective functions, helping to select the most biologically accurate model [4].

- Enhancing Predictive Power for Metabolic Engineering: In plant biotechnology, refined models can more reliably identify key genetic targets for engineering efforts aimed at improving yield, stress resistance, or the production of valuable compounds [4] [1].

Workflow for Integrating 13C-MFA with CBMs

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating 13C-MFA derived fluxes into a constraint-based modeling framework.

Integration Workflow for 13C-MFA and CBMs

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting 13C-MFA for Flux Estimation

This protocol outlines the core steps for obtaining intracellular flux estimates using 13C-MFA, which will later serve as constraints.

Step 1: Design and Execute the Labeling Experiment

- Tracer Selection: Choose appropriate 13C-labeled substrates. For plant studies, common choices include [U-13C]glucose, [1-13C]glucose, or 13CO2. Using parallel labeling experiments with multiple tracers can significantly improve flux resolution [4] [32].

- Culture Conditions: Grow plant cells, tissues, or seedlings under controlled conditions in the presence of the labeled substrate. Ensure metabolic and isotopic steady-state for Stationary State MFA (SS-MFA), or perform time-course sampling for Isotopically Nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) [1] [33].

- Sampling: Quench metabolism rapidly at the appropriate time point and extract intracellular metabolites.

Step 2: Measure Isotopic Labeling and External Fluxes

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of proteinogenic amino acids or central metabolites using GC-MS or LC-MS. Provide uncorrected MIDs in publications to ensure reproducibility [32].

- External Rates: Precisely measure the consumption rates of substrates (e.g., sugars, CO2) and production rates of end-products (e.g., organic acids, amino acids, CO2, biomass). Calculate yields (e.g., mol product per 100 mol substrate) [32].

Step 3: Model Construction and Flux Estimation

- Define Network Model: Construct a stoichiometric model of the central carbon metabolism relevant to your plant system, including atom transition mappings for each reaction [32].

- Non-Linear Regression: Use dedicated software to find the flux distribution that minimizes the residual sum of squares (RSS) between the simulated and measured MIDs and external fluxes [34]. The optimization problem can be formalized as:

argmin:(x-xM)Σε(x-xM)T s.t. S·v=0, M·v ≥ bwherevis the flux vector,Sis the stoichiometric matrix, andxandxMare the simulated and measured labeling patterns, respectively [1] [33]. - Statistical Assessment: Perform a χ2-test of goodness-of-fit to validate that the model adequately explains the experimental data. Report confidence intervals for all estimated fluxes, for example, through parameter continuation [4] [32].

Protocol 2: Formulating and Applying Flux Constraints in CBMs

This protocol describes how to translate 13C-MFA results into actionable constraints for a genome-scale CBM.

Step 1: Map 13C-MFA Fluxes to the CBM Reaction Set

- Identify the reactions in the large-scale CBM that correspond to the fluxes estimated in the smaller 13C-MFA network. This may involve summing isozyme reactions or splitting a net flux in the CBM that is represented by several steps in the 13C-MFA model.

Step 2: Formulate the Constraints

- Direct Value Constraints: For well-resolved fluxes with narrow confidence intervals, fix the flux value

vito the estimated valuevestimatedor set tight bounds:vestimated - δ ≤ vi ≤ vestimated + δ, whereδrepresents the uncertainty or a small tolerance. - Directionality Constraints: For fluxes with high uncertainty in their absolute value but a reliably determined direction (e.g., net flux through a reversible reaction), set the lower or upper bound accordingly (e.g.,

vi ≥ 0). - Ratio Constraints: To capture relationships between fluxes without fixing their absolute values, impose flux ratios derived from 13C-MFA (e.g.,

vPPP / vGlycolysis = 0.15).

Step 3: Implement and Solve the Constrained Model

- Integrate the new constraints into the CBM's linear programming problem. The core FBA problem then becomes:

Maximize Z = c^T v, subject to: S·v = 0, lb ≤ v ≤ ub, and 13C-MFA constraintswherelbandubare the original lower and upper bounds [4]. - Solve the model using a suitable solver. Subsequently, techniques like Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) can be used to characterize the remaining solution space and assess how effectively the 13C-MFA constraints reduced its size [4].

Quantitative Data and Research Tools

The table below provides examples of central metabolic fluxes that can be constrained in a plant CBM, along with their potential impact.

Table 1: Example 13C-MFA Flux Constraints for Plant CBMs

| Metabolic Pathway/Reaction | Flux Type | Typical Constraint Form | Impact on CBM Solution Space |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | Net flux relative to glycolysis | v_PPP / v_G6PDH = k1 |

Reduces ambiguity in NADPH production and ribose-5P synthesis [35]. |

| Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle | Absolute flux (e.g., citrate synthase) | v_CS = k2 ± δ |

Constrains mitochondrial energy metabolism and anapleurotic flows [35]. |

| Glycolysis | Absolute flux (e.g., phosphofructokinase) | v_PFK = k3 ± δ |

Fixes the core carbon utilization rate [35]. |

| Photorespiration | Net glycine decarboxylation flux | v_GDC = k4 |

Critically defines the metabolic cost of RuBisCO oxygenation in photosynthetic tissues. |

| Transhydrogenation (e.g., malic enzyme) | Reversible flux direction | v_ME ≥ 0 or v_ME ≤ 0 |

Constrains NADPH/NADH interconversion and redox balance. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

A successful integration project relies on specific computational and experimental reagents.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Integration

| Category | Item / Software | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | mfapy [34] | An open-source Python package for performing 13C-MFA; offers flexibility for custom analysis and simulation. |

| Omix [36] | A visual tool suite providing graphical workflows for various aspects of 13C-MFA, enhancing model proofreading and productivity. | |

| Cobrapy | A widely used Python package for constraint-based modeling of metabolism (FBA, FVA). | |

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C2]Glucose [35] | Resolves pentose phosphate pathway vs. glycolysis activity. |

| [U-13C]Glutamine/Aspartate [35] | Traces TCA cycle anaplerosis and nitrogen metabolism. | |

| 13CO2 | Essential for probing photosynthetic and photorespiratory fluxes in autotrophic tissues. | |

| Analytical Techniques | GC-MS / LC-MS [32] [1] | Workhorses for measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) in metabolites. |

| NMR Spectroscopy [1] | Provides positional labeling information; can be used alongside MS data. | |

| 4-Methylcyclohexane-1,3-diamine | 4-Methylcyclohexane-1,3-diamine, CAS:13897-55-7, MF:C7H16N2, MW:128.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Allyl-4-chloroaniline | N-Allyl-4-chloroaniline|CAS 13519-80-7 |