Integrating Flux Variability Analysis with 13C Constraints: A Comprehensive Guide for Enhanced Metabolic Network Predictions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) with 13C-derived metabolic constraints, a powerful approach to refine genome-scale metabolic models.

Integrating Flux Variability Analysis with 13C Constraints: A Comprehensive Guide for Enhanced Metabolic Network Predictions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) with 13C-derived metabolic constraints, a powerful approach to refine genome-scale metabolic models. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling, practical methodologies for implementing 13C-MFA-constrained FVA, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing analyses, and robust techniques for model validation and selection. By synthesizing recent methodological advances, this guide aims to enhance the precision and reliability of in vivo flux predictions, with significant implications for metabolic engineering and biomedical research.

Core Principles: Understanding Flux Variability Analysis and 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

The Fundamental Challenge of Underdetermined Metabolic Networks

A fundamental challenge in metabolic network analysis is that the system of equations describing cellular metabolism at steady-state is typically underdetermined. This means there are more unknown metabolic fluxes (reaction rates) than mass balance equations, leading to infinite possible flux distributions that satisfy all constraints [1] [2]. The core mathematical problem originates from the stoichiometric matrix N, where for m metabolites and n reactions, the system Nv = 0 has n-m degrees of freedom when n > m [1]. This underdeterminacy severely limits our ability to uniquely determine intracellular flux distributions using conventional constraint-based modeling approaches alone.

This challenge permeates virtually all flux analysis techniques. In Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), underdeterminacy results in multiple optimal flux distributions that maximize biomass production [3]. In 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), the problem traditionally limited analysis to central carbon metabolism [2]. Overcoming this limitation requires innovative approaches that integrate complementary data types and computational frameworks to constrain the solution space to biologically relevant fluxes.

Methodological Frameworks for Addressing Underdeterminacy

Computational Approaches

Several computational strategies have been developed to tackle underdetermined metabolic networks, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): This approach determines the minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction while maintaining optimality of an objective function (e.g., growth rate) within a specified fraction. Traditional FVA requires solving 2n+1 linear programming problems, though improved algorithms can reduce this computational burden [4].

Flux Sampling: Instead of identifying a single flux solution, this method randomly samples the feasible flux space to determine distributions of biologically relevant states, providing a probabilistic view of metabolic capabilities [5].

Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA): This technique identifies flux distributions in mutant strains that minimize the distance from wild-type fluxes using quadratic programming, recognizing that engineered strains may not immediately reach optimal states [3].

Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) Analysis: EFMs represent minimal, non-decomposable metabolic pathways. The complete set of EFMs defines all possible metabolic routes, though computation becomes intractable for genome-scale networks [1].

Table 1: Computational Methods for Addressing Underdetermined Metabolic Networks

| Method | Mathematical Approach | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Linear Programming | Predicts optimal flux distribution | Multiple optima; assumes optimality |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | Linear Programming | Quantifies flux flexibility | Computationally intensive for large models |

| Flux Sampling | Random Sampling | Characterizes solution space | Does not provide unique solution |

| MOMA | Quadratic Programming | Predicts suboptimal mutant behavior | Requires known wild-type state |

| EFM Analysis | Convex Analysis | Identifies all pathway possibilities | Combinatorial explosion in large networks |

Experimental Constraints Using 13C Labeling

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis provides critical experimental constraints to reduce underdeterminacy by measuring intracellular reaction rates through isotopic labeling patterns [2] [6]. When cells are fed 13C-labeled substrates, the resulting mass isotopomer distributions in metabolic products provide information about the metabolic pathways that generated them. This approach effectively constrains fluxes without assuming evolutionary optimization principles [2].

Recent methodological advances have enabled the integration of 13C labeling data with genome-scale models, moving beyond traditional 13C-MFA limited to central carbon metabolism [2]. This integration provides a comprehensive picture of metabolite balancing and predictions for unmeasured extracellular fluxes while maintaining the validation benefits of matching experimental labeling measurements [2]. The synergy between 13C-MFA and FBA has proven particularly powerful for understanding metabolic adaptation to environmental changes [6].

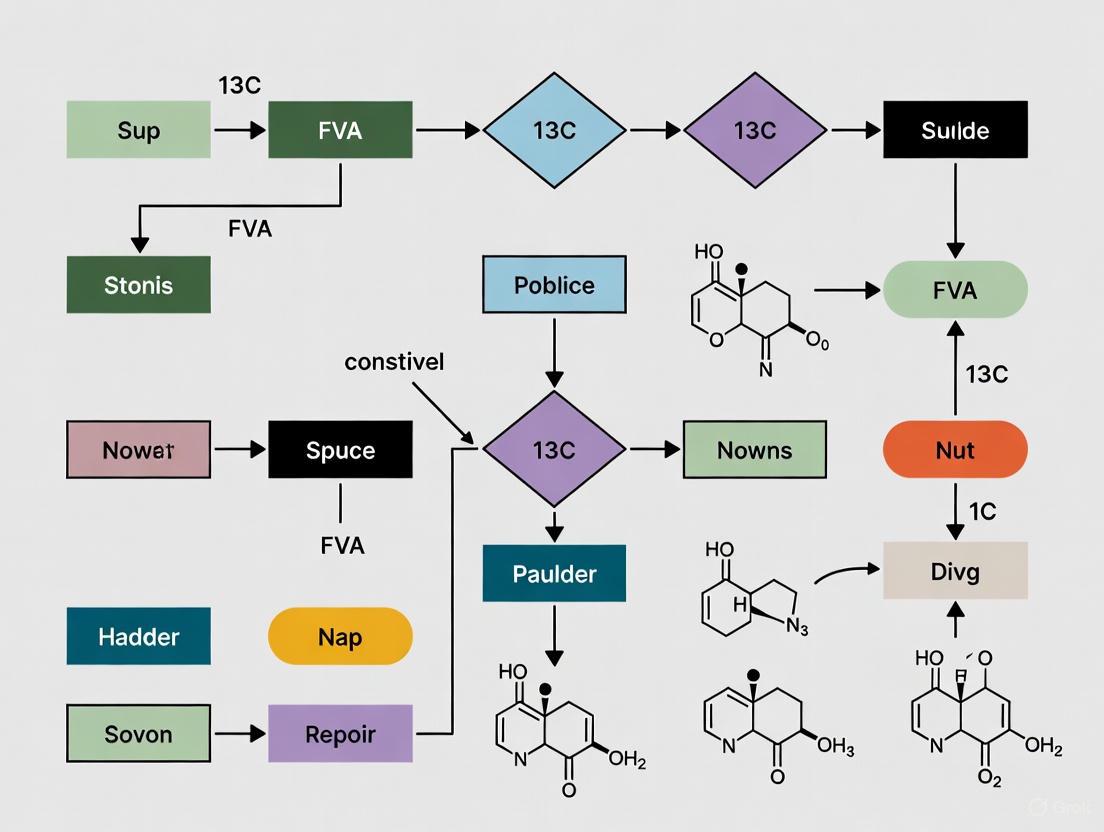

Figure 1: Integrated framework combining experimental and computational approaches to resolve underdetermined metabolic networks.

Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-Constrained FVA

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 13C-Constrained Flux Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracing carbon fate through metabolic networks | [1,1-13C]glucose for glycolytic flux determination [6] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Measuring mass isotopomer distributions | GC-MS analysis of proteinogenic amino acids [6] |

| Stoichiometric Models | Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction | iJR904 E. coli model [6], Recon3D human metabolism [4] |

| Flux Analysis Software | Implementing FVA and 13C-MFA algorithms | COBRA Toolbox [7], OpenFLUX [2] |

| Isotopomer Modeling | Simulating labeling patterns | Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework [8] |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Integrating 13C Constraints with Genome-Scale FVA

Objective: To determine intracellular flux distributions in E. coli under anaerobic conditions by integrating 13C labeling data with genome-scale flux variability analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- E. coli K-12 MG1655 strain (ATCC 47076)

- M9 minimal medium with [1,2-13C]glucose (2 g/L) as sole carbon source

- Equipment for GC-MS analysis

- COBRA Toolbox or similar metabolic modeling software

- Genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iJR904 for E. coli)

Procedure:

- Culture Conditions: Grow E. coli in M9 minimal medium with [1,2-13C]glucose at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. Monitor growth until mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5).

- Extracellular Flux Measurements: Quantify substrate uptake and product secretion rates using enzymatic assays, NMR spectroscopy, or HPLC.

- Isotopic Labeling Analysis: Harvest cells and derivatize proteinogenic amino acids for GC-MS analysis. Measure mass isotopomer distributions of intracellular metabolites.

- Flux Balance Analysis: Perform initial FBA using the genome-scale model with measured extracellular fluxes as constraints. Use biomass maximization as the objective function.

- Flux Variability Analysis: Implement FVA to determine the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal growth within a specified fraction (typically 90-99% of maximum).

- 13C Constraints Integration: Incorporate labeling data as additional constraints using a mixed-integer programming approach or by adding artificial metabolites to represent labeling patterns.

- Solution Space Reduction: Iteratively refine flux ranges by eliminating solutions incompatible with experimental labeling data.

- Validation: Compare predicted and measured mass isotopomer distributions to validate the constrained flux solution.

Expected Results: The protocol should yield a significantly reduced flux solution space compared to FVA alone. For E. coli under anaerobic conditions, expect to identify increased ATP maintenance requirements (≈51% of total ATP production) and non-cyclic TCA operation [6].

Protocol: Improved FVA Algorithm Implementation

Objective: To efficiently solve FVA problems with reduced computational time using an improved algorithm that leverages basic feasible solution properties.

Materials:

- Metabolic model in SBML format

- Linear programming solver (e.g., GLPK, CPLEX)

- MATLAB, Python, or R programming environment

Procedure:

- Phase 1 - Optimal Solution: Solve the initial FBA problem to find the maximum objective value Z0 using linear programming.

- Solution Inspection: Check if intermediate LP solutions are at upper or lower bounds for any flux variables.

- Phase 2 - Flux Range Determination: For each reaction, solve the maximization and minimization problems only if the bound was not already attained during solution inspection.

- Warm Starting: Use the simplex method with warm starts from previous solutions to reduce computation time.

- Parallelization: Implement parallel processing for independent optimization problems to further accelerate computation.

Expected Results: This algorithm reduces the number of linear programs required from 2n+1, showing a 30-50% reduction in computation time for models ranging from iMM904 to Recon3D [4].

Figure 2: Constraint strategies for resolving underdetermined metabolic networks, showing both experimental and computational approaches.

Applications and Future Directions

The integration of 13C constraints with FVA has enabled significant advances in both basic science and biotechnology applications. In metabolic engineering, these approaches have facilitated the development of microbial strains for industrial production of chemicals such as 1,4-butanediol, with commercial production reaching millions of pounds annually [2]. In biomedical research, constrained flux analysis provides insights into cancer metabolism, revealing adaptations such as heme biosynthesis compensation for dysfunctional TCA cycles [2].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on several key areas:

- Multi-omics integration: Combining transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to generate context-specific metabolic models [5]

- Dynamic flux analysis: Extending constraint-based methods to non-steady-state conditions using instationary 13C labeling [8]

- Machine learning approaches: Leveraging pattern recognition to predict flux distributions from partial data

- Single-cell fluxomics: Developing methods to analyze metabolic heterogeneity in cell populations

As these methodologies mature, the fundamental challenge of underdetermined metabolic networks will continue to diminish, enabling more accurate prediction and engineering of metabolic behavior across biological systems from microbes to human tissues.

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) methods provide a powerful mathematical framework to investigate metabolic states in biological systems by leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) [9]. These methods use mathematical representations of biochemical reactions, gene-protein-reaction associations, and physiological constraints to simulate metabolic network behavior. Unlike kinetic models that require extensive parameter determination, constraint-based approaches rely on mass-balance constraints and optimization principles to define the capabilities of metabolic networks [10]. Two fundamental techniques in this domain are Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Flux Variability Analysis (FVA), which enable researchers to predict metabolic flux distributions under steady-state conditions. When integrated with experimental data such as 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA), these methods become particularly powerful for quantifying intracellular metabolism and identifying metabolic vulnerabilities in diseases such as cancer [11] [12].

The core principle of constraint-based modeling is that metabolic networks must obey physicochemical constraints, including mass conservation, energy maintenance, and network connectivity [9]. Under the steady-state assumption, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, the metabolic network can be represented mathematically as a stoichiometric matrix S, with the mass balance equation S · v = 0, where v is the vector of metabolic fluxes [11] [10]. The solution space defined by these constraints can be explored using optimization techniques to identify flux distributions that maximize or minimize specific biological objectives, such as biomass production or ATP synthesis [10].

Theoretical Foundations

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Flux Balance Analysis is a mathematical approach for predicting metabolic flux distributions in genome-scale metabolic models [10]. FBA operates on the principle of steady-state mass balance, where the production and consumption of each metabolite within the system are balanced. The method formulates metabolism as a linear programming problem, seeking to identify a flux distribution that optimizes a specified cellular objective while satisfying all imposed constraints.

The core mathematical formulation of FBA comprises:

- Stoichiometric Constraints: Represented by the equation S · v = 0, where S is the m × n stoichiometric matrix (m metabolites and n reactions) and v is the vector of reaction fluxes.

- Capacity Constraints: Lower and upper bounds on reaction fluxes, defined as α ≤ v ≤ β, where α and β represent minimum and maximum allowable flux values for each reaction.

- Objective Function: A linear combination of fluxes specified as Z = c^Tv to be maximized or minimized, where c is a vector of weights indicating the contribution of each flux to the objective.

For microbial systems, the objective function is typically set to maximize biomass production, representing cellular growth, while for medical applications, objectives may be tailored to specific pathological contexts [10].

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)

Flux Variability Analysis extends FBA by determining the minimum and maximum possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining a near-optimal objective value [10]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying alternative optimal flux distributions and understanding pathway flexibility within metabolic networks.

The FVA algorithm involves:

- First performing FBA to determine the optimal objective value (Z_opt)

- Defining a slightly suboptimal value (e.g., 90-99% of Z_opt) to allow biological flexibility

- For each reaction i in the model:

- Maximize vi subject to S · v = 0, α ≤ v ≤ β, and c^Tv ≥ γZopt (where γ is the optimality fraction)

- Minimize v_i subject to the same constraints

- The resulting range [vi,min, *v*i,max] represents the feasible flux variability for each reaction

FVA is particularly useful for identifying blocked reactions (where vi,min = *v*i,max = 0), essential reactions, and network gaps [10].

Integration with 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a powerful experimental technique for quantifying in vivo metabolic pathway activity by utilizing 13C-labeled substrates and measuring the resulting isotope patterns in intracellular metabolites [11] [12]. The combination of 13C-MFA with constraint-based modeling creates a powerful framework for improving flux predictions by incorporating experimental measurements as additional constraints.

The fundamental principle of 13C-MFA involves:

- Introducing 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose) to cellular systems

- Measuring the resulting isotopic labeling patterns in metabolic intermediates using mass spectrometry or NMR

- Using computational methods to infer metabolic fluxes that best explain the observed labeling patterns [12]

When integrated with FVA, 13C-MFA data significantly reduces the solution space of possible flux distributions, leading to more accurate and biologically relevant predictions [11]. This integration is formally represented as:

Where x represents simulated isotopic labeling, x_M represents measured labeling, and Σ_ε is the covariance matrix of measurements [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

13C-MFA experiments require careful planning and execution to generate high-quality data for flux determination [13] [12].

Culture Conditions and Tracer Experiment

Bioreactor Setup: Perform cultures in controlled bioreactors with monitoring capabilities for temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and off-gas composition [13]. For bacterial systems, maintain optimal growth conditions (e.g., 50°C for B. methanolicus, 37°C for mammalian cells).

Medium Preparation: Prepare defined culture medium with essential nutrients. Example composition per liter:

- 3.48 g Na₂HPO₄·12H₂O

- 0.606 g KHâ‚‚POâ‚„

- 2.5 g NHâ‚„Cl

- 0.048 g yeast extract

- 1 ml of 1 M MgSOâ‚„ solution

- 1 ml trace salt solution

- 1 ml vitamin solution

- 0.05 ml Antifoam 204

- Carbon source (e.g., 150 mM methanol or 25 mM glucose) [13]

Tracer Pulse: Introduce 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., 100 mM 13C-methanol, 99% 13C) when cultures reach mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 2.5) [13]. Ensure precise measurement of tracer concentration and timing.

Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points after tracer introduction:

- For isotopically instationary MFA (INST-MFA): Sample rapidly (e.g., 13 time points within 3.5 minutes) to capture labeling kinetics [13]

- For stationary MFA (SS-MFA): Sample after isotopic steady state is reached (typically 24-48 hours)

Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

Sampling and Quenching: Rapidly collect culture samples (1-5 ml) and immediately quench metabolism using cold methanol or other appropriate quenching methods [13].

Metabolite Extraction:

- Separate cells from medium by rapid centrifugation (13,000 × g, 60 seconds)

- Extract intracellular metabolites using cold methanol/water/chloroform mixtures

- Collect aqueous phase for polar metabolites

- Dry samples under nitrogen or vacuum

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze metabolite extracts using ion chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (IC-MS/MS) [13]

- Use liquid anion-exchange chromatography for separation

- Employ internal standards (e.g., 13C-labeled E. coli extract) for quantification

- Measure isotopologue distributions for key central carbon metabolites

Data Correction:

- Correct raw MS data for natural isotope abundance using software such as IsoCor [13]

- Identify and remove cross-contaminated isotopologue measurements

Flux Calculation

Model Preparation: Define a comprehensive metabolic network model including atom transitions for each reaction.

Parameter Estimation: Use specialized software (e.g., INCA, Metran) to estimate fluxes by minimizing the difference between measured and simulated labeling patterns [12].

Statistical Analysis: Determine confidence intervals for estimated fluxes using Monte Carlo sampling or sensitivity analysis.

Protocol for Integrating 13C-MFA with FVA

The integration of experimental 13C-MFA data with FVA significantly enhances the predictive power of metabolic models by constraining the solution space [11] [10].

GEM Preparation: Start with a well-curated genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli or Recon3D for human) [10].

Integration of 13C-MFA Data:

- Convert 13C-MFA estimated fluxes into additional constraints for the model

- For each reaction i with flux estimate vi,13C, add constraint: *v*i,13C - δi ≤ *v*i ≤ vi,13C + *δ*i

- Where δ_i represents the confidence interval from 13C-MFA

Flux Variability Analysis with 13C Constraints:

- Perform standard FBA to determine optimal objective value (Z_opt)

- Set optimality fraction γ (typically 0.9-0.99)

- For each reaction i in the model:

- Maximize vi subject to S · v = 0, capacity constraints, 13C-derived constraints, and c^Tv ≥ γZopt

- Minimize v_i subject to the same constraints

- Record the flux range for each reaction

Interpretation of Results:

- Identify reactions with significantly reduced variability due to 13C constraints

- Pinpoint key branch points where flux splits are well-determined by 13C data

- Recognize reactions where large variability persists despite 13C constraints, indicating areas requiring additional experimental data

Computational Implementation

Python Tools for Constraint-Based Modeling

The development of open-source Python tools has dramatically increased the accessibility of constraint-based modeling methods [9]. These tools provide comprehensive capabilities for model reconstruction, simulation, and analysis.

Table 1: Python Packages for Constraint-Based Modeling

| Package | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | Core FBA/FVA simulations | Model loading, editing, simulation, basic analysis | Flux prediction, gap filling [10] [9] |

| ECMpy | Enzyme-constrained modeling | Integration of enzyme kinetics, kcat data | Metabolic engineering, pathway optimization [10] |

| MTEApy | Metabolic task analysis | TIDE algorithm implementation, pathway activity inference | Drug response analysis, cancer metabolism [14] |

| INCA | 13C-MFA | Isotopic labeling simulation, flux estimation | Experimental flux determination [12] |

Workflow Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for combining 13C-MFA with constraint-based modeling:

Integrated 13C-MFA and FVA Workflow

Code Example: FVA with 13C Constraints

The following Python code demonstrates how to perform FVA with additional constraints derived from 13C-MFA:

Research Applications

Case Study: Drug-Induced Metabolic Changes in Cancer

Constraint-based modeling with FVA and 13C-MFA has been successfully applied to investigate metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells and response to drug treatments [14]. A recent study analyzed the effects of kinase inhibitors (TAKi, MEKi, PI3Ki) and their synergistic combinations on the gastric cancer cell line AGS using transcriptomic profiling and metabolic modeling [14].

The research approach involved:

Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing of AGS cells under different drug treatment conditions to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

Metabolic Task Analysis: Application of the TIDE (Tasks Inferred from Differential Expression) algorithm to infer changes in metabolic pathway activity from gene expression data [14]

Flux Analysis: Integration of transcriptomic constraints with FVA to identify metabolic vulnerabilities

Key findings included:

- Widespread down-regulation of biosynthetic pathways, particularly in amino acid and nucleotide metabolism

- Strong synergistic effects in the PI3Ki-MEKi combination affecting ornithine and polyamine biosynthesis

- Identification of condition-specific metabolic alterations providing insight into drug synergy mechanisms [14]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for 13C-MFA and Constraint-Based Modeling

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Metabolic flux tracing | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine, 13C-methanol (99% 13C) [13] [12] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Isotopologue measurement | IC-MS/MS, GC-MS for metabolite separation and detection [13] |

| Metabolic Models | Computational simulations | iML1515 (E. coli), Recon3D (human), tissue-specific models [10] [9] |

| Software Tools | Data analysis and flux estimation | INCA, Metran (13C-MFA); COBRApy, ECMpy (constraint-based modeling) [12] [9] |

| Cell Culture Systems | Controlled biological experiments | Bioreactors with monitoring capabilities (temperature, pH, dissolved Oâ‚‚/COâ‚‚) [13] |

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic pathway analysis of drug-induced changes in cancer cells:

Drug-Induced Metabolic Changes Analysis

The integration of constraint-based modeling techniques such as FBA and FVA with experimental 13C metabolic flux analysis represents a powerful paradigm for investigating cellular metabolism with unprecedented quantitative precision. This combined approach enables researchers to leverage the strengths of both computational and experimental methods: computational models provide a comprehensive framework of metabolic network capabilities, while 13C-MFA delivers critical experimental constraints that refine flux predictions and reduce solution space uncertainty.

The continuing development of open-source computational tools in Python has dramatically increased the accessibility of these methods to the broader research community [9]. Meanwhile, advances in analytical technologies for measuring isotopic labeling patterns and computational algorithms for flux estimation continue to enhance the resolution and accuracy of metabolic flux maps [11] [12]. These developments position constraint-based modeling with 13C constraints as an increasingly essential methodology for addressing fundamental questions in metabolic engineering, cancer biology, and drug development.

13C-MFA as the Gold Standard for Empirical Flux Constraint

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has established itself as the empirical gold standard for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells. By integrating data from 13C tracer experiments with sophisticated computational models, 13C-MFA provides unique constraints that significantly enhance the resolution and predictive power of flux variability analysis (FVA). This protocol outlines the rigorous application of 13C-MFA for deriving empirical flux constraints, detailing experimental design, data integration, and model validation practices essential for generating high-quality, reproducible fluxomics data.

Quantitative knowledge of metabolic fluxes is fundamental to understanding cellular physiology in fields ranging from metabolic engineering to biomedical research [11] [15]. While constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and FVA can predict flux distributions across genome-scale networks, they often rely on hypothetical objective functions and yield solution spaces containing numerous possible flux maps [16] [7]. 13C-MFA addresses this limitation by providing experimental measurements of intracellular fluxes, serving as a gold standard for validating and refining constraint-based models [17].

The principal advantage of 13C-MFA lies in its use of stable isotope tracers, typically 13C-labeled substrates, to track the fate of individual atoms through metabolic pathways [18]. The resulting labeling patterns in metabolites are highly sensitive to relative pathway fluxes, providing a rich dataset of redundant measurements that far exceeds the number of estimated flux parameters [18]. This redundancy significantly improves the accuracy and confidence of flux estimations compared to approaches relying solely on extracellular measurements [11] [17]. When integrated with FVA, 13C-derived fluxes provide critical empirical constraints that dramatically reduce the feasible solution space, leading to more biologically relevant predictions [16].

Table 1: Classification of 13C-Based Flux Analysis Methods

| Method Type | Applicable System | Computational Complexity | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Fluxomics (Isotope Tracing) | Any system | Easy | Provides only local and qualitative flux information [11] |

| Metabolic Flux Ratios Analysis | Systems where fluxes, metabolites, and labeling are constant | Medium | Provides only local and relative quantitative values [11] |

| Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) | Systems where fluxes, metabolites, and labeling are constant | Medium | Not applicable to dynamic systems [11] |

| Isotopically Instationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA) | Systems where fluxes and metabolites are constant but labeling is variable | High | Not applicable to metabolically dynamic systems [11] |

| Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP) | Systems where fluxes and metabolites are constant while labeling is variable | Medium | Provides only local and relative quantitative flux values [11] |

Fundamental Principles and Experimental Design

Theoretical Basis of 13C-MFA

13C-MFA operates on the principle that metabolic flux distributions directly influence the isotopic labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites [11]. When cells are fed 13C-labeled substrates, the carbon atoms are distributed through metabolic networks in patterns determined by the fluxes of enzymatic reactions. The relationship between fluxes and labeling patterns is formalized through mathematical models that simulate carbon atom transitions [11] [19]. Flux values are estimated by solving an inverse problem where the differences between model-predicted and experimentally measured isotopic labeling are minimized [11] [16].

The core optimization problem in 13C-MFA can be formalized as:

Where v represents the vector of metabolic fluxes, S is the stoichiometric matrix, x is the vector of simulated isotopic labeling, and xM is the corresponding experimental measurement [11]. The constraints ensure that the solution satisfies mass balance and physiological feasibility.

Critical Design Considerations

Tracer Selection

The choice of isotopic tracer significantly impacts flux resolution. While early studies often used single-labeled substrates like [1-13C]glucose, current best practices recommend mixtures of differently labeled tracers or novel tracers like [2,3-13C]glucose and [4,5,6-13C]glucose to improve flux observability throughout the metabolic network [20]. Different tracers resolve fluxes in different parts of metabolism effectively; for example, 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose optimizes flux resolution in upper glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathways, while [4,5,6-13C]glucose performs better for TCA cycle and anaplerotic reactions [20].

Culture Conditions

Metabolic and isotopic steady-state must be achieved and rigorously maintained throughout the experiment [15] [18]. For microbial systems, this is typically accomplished in chemostat cultures or carefully controlled batch cultures during exponential growth [15]. The cultivation medium should be strictly minimal with the selected 13C-labeled substrate as the sole carbon source to prevent dilution of the isotopic label [15]. The incubation time should exceed five residence times to ensure the system reaches isotopic steady state [18].

Diagram 1: 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow for Flux Constraint Generation

Experimental Protocol: Isotopic Tracer Experiment

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for 13C-MFA

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose, [4,5,6-13C]glucose [20] | Carbon sources for tracing metabolic pathways; selection depends on pathways of interest and organism |

| Culture Medium Components | M9 minimal medium (for E. coli), defined minimal media [20] | Provides essential nutrients while maintaining isotopic purity; must contain labeled substrate as sole carbon source |

| Derivatization Reagents | TBDMS, BSTFA [15] | For GC-MS analysis; increases volatility of metabolites for separation and detection |

| Enzymes for Hydrolysis | Acid or base catalysts for protein hydrolysis [15] | Releases proteinogenic amino acids from biomass for isotopic analysis of protein-bound metabolites |

| Internal Standards | 13C-labeled internal standards for LC-MS [15] | For quantification and correction of instrumental variance in mass spectrometry |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Tracer Preparation and Culture Setup

- Prepare stock solutions of selected isotopic tracers at appropriate concentrations (e.g., 20% w/v glucose in distilled water) [20]. For tracer mixtures, prepare fresh stock solutions at the desired ratios.

- Formulate minimal medium with the 13C-labeled substrate as the sole carbon source. Filter-sterilize the medium to maintain isotopic purity.

- Inoculate cultures at appropriate cell density and incubate under controlled conditions (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen) relevant to the organism.

- Maintain steady-state growth: For chemostat cultures, allow at least 5 residence times to achieve metabolic and isotopic steady state before sampling [18]. For batch cultures, harvest during mid-exponential growth phase.

Sample Collection and Quenching

- Harvest culture samples rapidly using rapid filtration or cold quenching techniques to immediately halt metabolic activity.

- Separate cells from medium via rapid filtration or centrifugation.

- Wash cells with appropriate buffer (e.g., isotonic saline) to remove residual medium components.

- Flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until extraction.

Metabolite Extraction and Derivatization

- Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate methods. For GC-MS analysis of proteinogenic amino acids:

- For LC-MS analysis, extract polar metabolites using methanol/water mixtures without derivatization.

Analytical Methods: Isotopic Labeling Measurement

Mass Spectrometry Techniques

Table 3: Analytical Techniques for Isotopic Labeling Measurement

| Technique | Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Analysis of proteinogenic amino acids, organic acids | High sensitivity, widespread availability, well-established protocols [15] | Requires derivatization, limited to volatile compounds |

| LC-MS | Analysis of labile metabolites, central carbon intermediates | No derivatization required, high sensitivity for polar metabolites [15] | Potentially lower chromatographic resolution than GC-MS |

| GC-MS/MS | Complex metabolic networks, high precision requirements | Enhanced sensitivity and resolution through multiple mass analyses [18] | More complex instrumentation and data analysis |

| NMR | Positional isotopomer analysis, pathway identification | Provides positional labeling information, non-destructive [17] | Lower sensitivity compared to MS techniques |

Data Processing and Correction

- Correct raw mass isotopomer distributions for natural abundance of stable isotopes (13C, 2H, 15N, 18O, 29Si, 30Si) using established algorithms [15].

- Generate Mass Distribution Vectors (MDVs) for each measured metabolite.

- Calculate standard deviations from biological and technical replicates to weight measurements appropriately during flux fitting [17].

Computational Flux Analysis and Integration with FVA

Flux Estimation Using Computational Tools

- Select appropriate software for flux estimation (e.g., OpenFLUX2, 13CFLUX2, Metran, INCA) [15].

- Define metabolic network model including:

- Complete stoichiometric matrix

- Atom transitions for all reactions

- Balanced and non-balanced metabolites [17]

- Input experimental data including:

- Corrected MDVs for measured metabolites

- External flux measurements (substrate uptake, product secretion, growth rates)

- Measurement standard deviations [17]

- Perform nonlinear regression to minimize the difference between simulated and measured labeling patterns:

Model Validation and Statistical Analysis

- Evaluate goodness-of-fit using the χ²-test or similar statistical tests [17] [7]. The minimized SSR should follow a χ² distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of data points minus the number of estimated parameters [18].

- Calculate confidence intervals for estimated fluxes using sensitivity analysis, Monte Carlo sampling, or parameter continuation methods [18] [17].

- Perform model selection using validation-based approaches, particularly when comparing alternative network topologies [21].

Diagram 2: Integration of 13C-MFA Derived Flux Constraints with FVA

Integration with Flux Variability Analysis

- Translate 13C-MFA flux estimates into constraints for genome-scale models:

- Incorporate estimated net fluxes and exchange coefficients as additional constraints

- Apply confidence intervals as flux bounds rather than point estimates

- Perform FVA with the added 13C-derived constraints to identify the feasible flux space.

- Compare flux ranges between unconstrained and constrained FVA to assess the information gain from 13C-MFA data.

Advanced Applications: COMPLETE-MFA and Genome-Scale 13C-MFA

The COMPLETE-MFA (Complementary Parallel Labeling Experiments Technique) approach significantly enhances flux resolution by integrating data from multiple parallel tracer experiments [20]. In a landmark study analyzing 14 parallel labeling experiments in E. coli, COMPLETE-MFA improved both flux precision and observability, resolving more independent fluxes with smaller confidence intervals, particularly for exchange fluxes that are difficult to estimate using single tracer experiments [20].

Emerging approaches now extend 13C-MFA to genome-scale coverage (GS-MFA), addressing limitations of traditional core metabolic models. GS-MFA eliminates flux range contraction artifacts caused by simplified network models and provides more accurate flux distributions by accounting for alternative pathways with similar carbon transitions [16].

13C-MFA provides the most rigorous empirical constraints for intracellular metabolic fluxes, serving as an indispensable tool for refining and validating flux predictions from constraint-based models. The protocols outlined here—from careful experimental design through computational integration with FVA—enable researchers to generate high-quality flux constraints that significantly enhance the biological relevance of metabolic models. As 13C-MFA continues to evolve toward genome-scale applications and more sophisticated statistical frameworks, its role as the gold standard for empirical flux constraint will further solidify, enabling more accurate predictions of metabolic behavior across biological and biomedical research domains.

The Synergy of Combining Genome-Scale FVA with 13C Labeling Data

Constraint-based modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), has emerged as a fundamental tool for predicting metabolic behavior in genome-scale metabolic models. However, a significant limitation of conventional FBA is that it typically predicts a single flux distribution that optimizes a biological objective, such as growth rate, failing to capture the inherent flexibility and redundancy in metabolic networks [7]. Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) addresses this limitation by quantifying the range of possible fluxes through each reaction while maintaining optimal cellular objective function, thus characterizing the solution space of possible metabolic states [7].

The integration of 13C labeling data with genome-scale models represents a paradigm shift in metabolic flux analysis, moving from purely optimization-based predictions to data-driven constraints that significantly enhance biological relevance. This synergy enables researchers to leverage the comprehensive coverage of genome-scale models while incorporating the rich, dataset-specific information provided by 13C labeling experiments [22] [2]. This integrated approach provides a more accurate and comprehensive picture of metabolic network function, bridging the gap between top-down constraint-based modeling and bottom-up 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA) [2].

Theoretical Foundation and Methodological Advances

Fundamental Principles of 13C-MFA and FVA

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) operates on the principle that when cells are fed with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose), the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites provide a unique fingerprint of metabolic pathway activities [23] [12]. The mass distribution vector (MDV), which describes the fractional abundance of different isotopologues, serves as the primary data source for flux estimation [23]. Unlike FBA, which relies on evolutionary optimization assumptions, 13C-MFA directly utilizes experimental measurements to infer fluxes, providing a powerful validation mechanism for model predictions [22] [2].

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) extends FBA by computing the minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction while maintaining optimal growth or other specified cellular objectives. This approach recognizes that multiple flux distributions may achieve the same optimal objective value, thus characterizing the range of metabolic flexibility available to the cell [7]. When combined, these approaches leverage their complementary strengths: 13C-MFA provides high-resolution flux constraints for central carbon metabolism, while FVA contextualizes these constraints within the broader genome-scale metabolic network.

Key Methodological Developments

Recent methodological advances have significantly enhanced our ability to integrate 13C labeling data with genome-scale models. The approach developed by GarcÃa MartÃn et al. incorporates data from 13C labeling experiments to constrain genome-scale models without assuming an evolutionary optimization principle [22] [2]. This method makes the biologically relevant assumption that flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism and does not flow back, effectively constraining the solution space. The results of this method show strong agreement with traditional 13C-MFA for central carbon metabolism while additionally providing flux estimates for peripheral metabolism [2].

The COMPLETE-MFA (complementary parallel labeling experiments technique for metabolic flux analysis) approach has emerged as a powerful strategy for enhancing flux resolution [24]. By integrating multiple parallel labeling experiments, this methodology improves both flux precision and observability, resolving more independent fluxes with smaller confidence intervals. In a landmark study, integrated analysis of 14 parallel labeling experiments with E. coli demonstrated that no single tracer was optimal for the entire metabolic network, highlighting the importance of strategic tracer selection [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Metabolic Flux Analysis Techniques

| Method | Network Scope | Primary Constraints | Key Assumptions | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBA/FVA | Genome-scale | Stoichiometry, uptake/secretion rates | Optimization principle (e.g., growth maximization) | Comprehensive network coverage; predictive capability | Relies on assumed optimization principles |

| 13C-MFA | Central metabolism | 13C labeling patterns, extracellular fluxes | Metabolic and isotopic steady state | Direct experimental validation; high precision for central metabolism | Limited to central metabolism; experimentally intensive |

| Integrated FVA-13C | Genome-scale | 13C labeling patterns, stoichiometry, uptake/secretion rates | Flux from core to peripheral metabolism | Combines coverage and precision; eliminates need for optimization assumption | Computational complexity; requires careful experimental design |

Experimental Design and Protocol

Tracer Selection and Experimental Setup

The foundation of successful integrated FVA-13C analysis lies in careful experimental design, particularly in selecting appropriate isotopic tracers. Research has demonstrated that no single tracer is optimal for resolving fluxes across the entire metabolic network. Tracers that produce well-resolved fluxes in the upper part of metabolism (glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathways) often show poor performance for fluxes in the lower part of metabolism (TCA cycle and anaplerotic reactions), and vice versa [24]. For example, in E. coli studies, the best tracer for upper metabolism was 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose, while [4,5,6-13C]glucose and [5-13C]glucose both produced optimal flux resolution in the lower part of metabolism [24].

Parallel labeling experiments using multiple tracers have emerged as the gold standard for achieving high flux resolution. The COMPLETE-MFA approach enables researchers to obtain more precise flux estimates with narrower confidence intervals, particularly for exchange fluxes that are difficult to estimate using single tracer experiments [24]. When designing tracer experiments, it is crucial to ensure that the system is at both metabolic steady state (constant metabolite levels and fluxes) and isotopic steady state (stable labeling patterns over time) to simplify data interpretation [23] [12].

Figure 1: Integrated FVA-13C Workflow. The diagram outlines the key stages in combining 13C labeling experiments with flux variability analysis, from experimental design to model validation.

Protocol for High-Resolution 13C-MFA

The following protocol outlines the key steps for generating high-quality 13C labeling data suitable for constraining genome-scale FVA, adapted from established methodologies [25]:

Strain and Culture Conditions:

- Grow microbes in two or more parallel cultures with different 13C-labeled glucose tracers

- Use defined growth medium (e.g., M9 minimal medium for E. coli) with appropriate carbon sources

- Maintain controlled environmental conditions (temperature, aeration, pH) to ensure metabolic steady state

Sampling and Quenching:

- Collect samples during exponential growth phase to monitor cell growth and substrate uptake

- Rapidly quench metabolism to preserve isotopic labeling patterns

- Record optical density (OD600) and convert to cell dry weight concentrations using predetermined relationships

Analytical Measurements:

- Perform gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) measurements of isotopic labeling of protein-bound amino acids, glycogen-bound glucose, and RNA-bound ribose

- Correct mass isotopomer distributions for natural isotope abundances using established algorithms [23]

- Measure extracellular fluxes (substrate uptake, product secretion, growth rates) using concentration measurements and equations accounting for exponential growth [12]

Data Integration and Flux Calculation:

- Use specialized software (e.g., Metran, INCA) for 13C-MFA to estimate metabolic fluxes

- Perform comprehensive statistical analysis to determine goodness of fit and calculate confidence intervals for estimated fluxes

- Implement computational frameworks that incorporate the locally coupled reactions and global transcriptional regulation to improve flux predictions [26]

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for FVA-13C Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Specifications | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled Glucose Tracers | [1,2-13C]glucose, [4,5,6-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, custom mixtures | Create distinct labeling patterns to resolve different pathway fluxes |

| Defined Growth Medium | M9 minimal medium or equivalent with precisely controlled carbon sources | Maintain metabolic steady state and defined nutritional environment |

| Derivatization Reagents | MSTFA, TBDMS, or other GC-MS derivatization agents | Enable chromatographic separation and detection of metabolites |

| Internal Standards | 13C-labeled internal standards for relevant metabolites | Correct for analytical variability and quantify absolute concentrations |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Metabolite detection kits (e.g., glucose, lactate, glutamine) | Quantify extracellular metabolite concentrations for flux constraints |

Computational Integration Framework

Algorithmic Implementation

The computational integration of 13C labeling data with FVA involves a multi-step process that translates labeling measurements into constraints for genome-scale models. The core innovation lies in using the information-rich 13C labeling data to effectively constrain the high-dimensional solution space of genome-scale models without relying solely on optimization principles [22] [2]. This approach recognizes that while genome-scale models may contain hundreds of degrees of freedom, 13C-MFA represents a nonlinear fitting problem where some degrees of freedom are highly constrained while others remain flexible [2].

Advanced implementations incorporate local flux coordination principles, recognizing that metabolic networks contain topologically coupled reaction modules through which fluxes are coordinated. This local coupling is evidenced by high correlations between fluxes of neighboring reactions in conventional pathways (e.g., correlation coefficients of 0.913 for glycolysis reactions in E. coli) [26]. By identifying sparse linear basis vectors representing these coupled reactions, models can more accurately capture the coordinated regulation of metabolic fluxes in response to perturbations.

Model Validation and Selection

Robust validation is essential for establishing confidence in integrated FVA-13C predictions. The goodness of fit between measured and simulated labeling patterns provides a critical validation metric that is absent from traditional FBA [7] [2]. Statistical tests, particularly the χ2-test, can assess whether the model adequately explains the experimental data, though complementary validation approaches are recommended [7].

Additional validation strategies include:

- Comparison with 13C-MFA results for central carbon metabolism to ensure consistency in core metabolic fluxes

- Prediction of unmeasured extracellular fluxes and comparison with experimental measurements when available

- Sensitivity analysis to evaluate robustness to uncertainties in model structure and measurement errors

- Cross-validation using independent datasets to assess predictive capability

The integration of transcriptomic data provides another layer of validation, though studies have shown that transcript levels alone may not reliably predict metabolic fluxes due to post-transcriptional regulation [27] [26]. The Decrem model, which incorporates both local flux coordination and global transcriptional regulation, demonstrates improved prediction of flux and growth rates in E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and B. subtilis [26].

Applications and Case Studies

Metabolic Engineering and Biotechnology

The integration of FVA with 13C constraints has proven particularly valuable in metabolic engineering applications, where precise flux quantification is essential for strain optimization. This approach has contributed to successful engineering of microbial strains for industrial production of valuable chemicals, including 1,4-butanediol, a commodity chemical used to manufacture over 2.5 million tons annually of high-value polymers [22] [2]. The ability to precisely quantify fluxes using integrated FVA-13C allows identification of rate-limiting steps, redundant pathways, and thermodynamic constraints that impact product yield.

In bioprocess optimization, integrated FVA-13C provides insights into how metabolic fluxes change in response to bioreactor conditions (e.g., dissolved oxygen, nutrient feeding strategies). The quantification of flux variability under different process conditions helps identify optimal operating parameters and control strategies to maximize product titer, yield, and productivity while maintaining metabolic functionality.

Biomedical Research and Drug Development

In biomedical research, particularly cancer biology, integrated FVA-13C has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding metabolic rewiring in disease states. The approach has been used to characterize the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) and other metabolic alterations in cancer cells, identifying potential therapeutic targets [12]. The ability to quantify fluxes in central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and TCA cycle, provides insights into how cancer cells meet their biosynthetic and energy demands for rapid proliferation.

The application of integrated FVA-13C in drug development includes:

- Target identification by quantifying essential fluxes in pathogenic organisms or diseased cells

- Mechanism of action studies by tracking flux changes in response to drug treatment

- Biomarker discovery by identifying flux patterns associated with disease progression or treatment response

- Therapeutic optimization by understanding how metabolic network flexibility contributes to drug resistance

Figure 2: Application Areas of Integrated FVA-13C. The diagram shows how the methodology supports various applications from industrial biotechnology to biomedical research.

The synergy between genome-scale FVA and 13C labeling data represents a significant advancement in metabolic flux analysis, combining the comprehensive network coverage of constraint-based modeling with the experimental precision of 13C-MFA. This integrated approach addresses fundamental limitations of both individual methods, providing a more complete and accurate picture of metabolic network function.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on:

- Dynamic flux analysis incorporating time-course labeling data to capture metabolic transitions

- Multi-omics integration combining flux constraints with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data

- Single-cell flux analysis overcoming population averaging to characterize metabolic heterogeneity

- Machine learning approaches to enhance flux prediction from limited experimental data

- Automated model refinement using 13C labeling data to identify and correct gaps in metabolic reconstructions

The continued refinement and application of integrated FVA-13C methodology will enhance our fundamental understanding of metabolic regulation and accelerate the engineering of biological systems for biotechnology and therapeutic applications. As the field moves toward more comprehensive and predictive metabolic models, the synergy between experimental labeling data and computational analysis will remain essential for validating model predictions and generating biological insights.

Key Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Biomedical Research

Metabolic flux analysis, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), provides a powerful framework for quantifying intracellular reaction rates (fluxes) in living systems [28]. These constraint-based approaches use metabolic network models operating at steady state, where reaction rates and metabolic intermediate levels remain invariant [28]. The integration of 13C labeling constraints with flux variability analysis has significantly enhanced the predictive power and practical utility of these methods across multiple domains.

In metabolic engineering, these techniques enable rational design of microbial cell factories for producing valuable chemicals [2]. In biomedical research, they facilitate the identification of metabolic vulnerabilities in human diseases, particularly in cancer [28]. This article details key applications and provides standardized protocols for implementing these advanced flux analysis techniques.

Key Applications

Metabolic Engineering

Table 1: Metabolic Engineering Applications of 13C-Constrained FVA

| Application | Organism/System | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Optimization for Chemical Production | Escherichia coli | Development of 1,4-butanediol hyperproducing strains; 5 million pound commercial production achieved | [2] |

| Lysine Production | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Creation of lysine hyper-producing strains through targeted metabolic rewiring | [28] |

| Chemoautotrophic Growth Engineering | Escherichia coli | Successful rewiring of central metabolism to enable growth on CO2 as carbon source | [28] |

| Metabolic Burden Assessment | Streptomyces lividans | Identification of flux redistribution during heterologous protein production | [29] |

Biomedical Research

Table 2: Biomedical Research Applications of 13C-Constrained FVA

| Application | Biological System | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Metabolism | Carcinoma Cell Lines | Identification of forcedly balanced complexes with lethal effects in cancer but minimal impact on healthy tissues | [30] |

| Tumor Metabolism | Cancer Cells | Discovery of heme biosynthesis/degradation compensation for dysfunctional TCA cycle | [2] |

| Metabolic Target Identification | Lung Carcinoma | Optimal tracer selection (1,2-13C2 glucose) for precise flux quantification in cancer cells | [29] |

| Disease Mechanism Elucidation | Mammalian Cells | Resolution of compartment-specific fluxes and reversible reaction fluxes in disease states | [17] |

Experimental Protocols

13C-MFA with FVA Constraints: Integrated Workflow

Protocol 1: 13C Tracer Experiment Design

Objective: Establish optimal conditions for isotopic labeling experiments to maximize flux resolution while minimizing costs.

Materials:

- Cell culture system (microbial or mammalian)

- Unlabeled basal medium

- 13C-labeled substrates (see Table 4 for selection guidelines)

- Metabolic quenching solution (e.g., cold methanol)

- Sample processing equipment

Procedure:

- Tracer Selection: Choose tracer mixture based on multi-objective optimization considering both information content and cost [29]. For mammalian cells, optimal mixtures often contain 1,2-13C2 glucose combined with uniformly labeled glucose or glutamine.

- Experiment Setup: Cultivate cells in defined medium containing the selected 13C tracer mixture. Ensure metabolic steady-state is reached before sampling.

- Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points during isotopic non-stationary phase (INST-MFA) or at endpoint for stationary MFA.

- Metabolite Extraction: Use appropriate extraction protocols for intracellular metabolites.

- Labeling Measurement: Analyze mass isotopomer distributions using GC-MS or LC-MS.

Protocol 2: Flux Variability Analysis with 13C Constraints

Objective: Determine feasible flux ranges while satisfying both stoichiometric and isotopic labeling constraints.

Materials:

- Metabolic network model (stoichiometric matrix)

- Experimentally measured external fluxes

- Isotopic labeling data

- Computational resources (COBRA Toolbox, 13C-FLUX2, or similar)

Procedure:

- Initial FBA: Solve the base FBA problem to determine optimal objective value (e.g., maximal growth rate).

- Solution Space Characterization: Implement FVA to determine minimum and maximum possible fluxes for all reactions while maintaining optimal or sub-optimal objective function value.

- Algorithm Optimization: Use improved FVA algorithms that reduce the number of linear programming solutions required from 2n+1 by inspecting intermediate solutions [4].

- 13C Constraints Integration: Incorporate labeling constraints by adding penalty terms to the objective function or by directly including labeling balances as additional constraints [2].

- Flux Range Calculation: Compute refined flux variability ranges that satisfy both stoichiometric and isotopic constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Uptake Assay Kit | Quantify glucose consumption rates | Constraint definition for FBA/FVA models |

| ATP Assay Kit | Measure cellular energy status | Validation of energy maintenance predictions |

| PEP Assay Kit | Phosphoenolpyruvate quantification | Glycolytic flux validation |

| 13C-labeled Substrates (e.g., 1,2-13C2 glucose) | Tracing carbon fate through metabolic networks | 13C-MFA experiments for flux determination |

| Mass Spectrometry Standards | Instrument calibration and quantification | Accurate measurement of mass isotopomer distributions |

| Dioxouranium;dihydrofluoride | Dioxouranium;dihydrofluoride, CAS:13536-84-0, MF:F2H2O2U, MW:310.040 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methyl 3-ethylpent-2-enoate | Methyl 3-ethylpent-2-enoate |

Table 4: 13C Tracer Selection Guide

| Tracer Type | Cost Relative to U-13C Glucose | Optimal Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-13C glucose | Low | Central carbon metabolism mapping | Cost-effective for basic flux mapping |

| U-13C glucose | Medium | Comprehensive flux analysis | Broad coverage of metabolic pathways |

| 1,2-13C2 glucose | High (3x U-13C glucose) | Resolving parallel pathways/cycles | Superior for phosphoglucoisomerase flux |

| U-13C glutamine | High | Mammalian cell culture studies | Effective for TCA cycle anaplerotic fluxes |

Computational Implementation

Metabolic Network Analysis: Core Concepts

Enhanced FVA Algorithm

The improved FVA algorithm reduces computational burden by leveraging basic feasible solution properties of linear programs [4]:

Algorithm Implementation:

- Solve initial FBA problem to obtain optimal objective value Zâ‚€

- For each reaction i, instead of automatically solving max/min problems:

- Inspect intermediate LP solutions for flux variables at bounds

- Skip redundant optimizations when bounds are already known

- Use warm-starts for sequential LPs to reduce computation time

- Employ simplex method to guarantee basic feasible solutions

This approach reduces the number of LPs required from 2n+1, with demonstrated speedups of 30-220x compared to naive implementations [31].

The integration of 13C constraints with flux variability analysis represents a significant advancement in metabolic modeling capability. In metabolic engineering, these methods have demonstrated direct industrial application, enabling successful commercialization of bio-based chemical production [2]. In biomedical research, they provide unique insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [30]. The standardized protocols and analytical frameworks presented here offer researchers comprehensive tools for implementing these powerful techniques in diverse biological systems.

Future developments will likely focus on enhanced integration of multi-omics data, dynamic flux analysis capabilities, and improved algorithms for handling genome-scale models with higher computational efficiency. The establishment of minimum reporting standards for 13C-MFA studies [17] will further enhance reproducibility and comparability across studies, accelerating progress in both fundamental and applied metabolic research.

A Practical Framework for Implementing 13C-Constrained FVA

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) are powerful constraint-based modeling frameworks for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes. 13C-MFA uses stable isotope tracers to experimentally determine metabolic pathway activities, while FVA characterizes the range of possible reaction fluxes in metabolic networks. The integration of 13C-derived flux constraints with FVA creates a more accurate and biologically relevant representation of metabolic capabilities under different physiological conditions [2] [32]. This protocol provides a detailed workflow for implementing 13C-constrained FVA, enabling researchers to obtain high-resolution insights into metabolic network flexibility and limitations.

Theoretical Background

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

13C-MFA quantifies in vivo metabolic fluxes by utilizing 13C-labeled substrates and measuring the resulting isotope patterns in intracellular metabolites. The fundamental principle is that different flux distributions produce distinct isotopic labeling patterns, allowing computational inference of metabolic fluxes [11]. The method assumes metabolic steady-state, where metabolite concentrations and reaction fluxes remain constant. 13C-MFA has evolved into a diverse method family with applications spanning microbial, plant, and mammalian systems [11] [33].

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)

FVA extends Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) by determining the feasible range of each reaction flux within a metabolic network while satisfying physiological constraints and maintaining optimal or sub-optimal biological objective function values [4]. Traditional FBA finds a single optimal flux distribution, but FVA characterizes the solution space of all possible flux distributions, identifying flexible and rigid reactions in the network [4].

The Rationale for Integration

Combining 13C-MFA with FVA leverages the strengths of both approaches: 13C-MFA provides experimental validation and thermodynamic constraints, while FVA offers comprehensive network analysis capabilities. This integration significantly reduces the solution space of genome-scale models by incorporating empirical flux measurements, leading to more accurate predictions of metabolic capabilities [2] [32].

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

Tracer Selection Principles

Selecting appropriate 13C-tracers is crucial for obtaining meaningful flux constraints. The optimal tracer depends on the specific metabolic pathways of interest and the biological system under investigation [34]. Rational tracer design should consider:

- Pathway-specific resolution: Different tracers illuminate different metabolic pathways

- Cost-effectiveness: Balance between information content and experimental cost

- Biological relevance: Match tracer to primary carbon sources utilized by the organism

Table 1: Commonly Used 13C-Tracers and Their Applications

| Tracer | Application Focus | Pathway Resolution | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1-13C] Glucose | Glycolysis, PPP | Moderate | Low |

| [U-13C] Glucose | Comprehensive central carbon metabolism | High | Medium |

| [1,2-13C] Glucose | Phosphoglucoisomerase flux, PPP | High | High |

| [U-13C] Glutamine | TCA cycle, anaplerosis | High | High |

| [3,4-13C] Glucose | Pyruvate carboxylase activity | Specific | Medium |

Optimal Tracer Design

Advanced tracer design employs computational frameworks like Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) decomposition to systematically evaluate tracer effectiveness. For mammalian cells, optimal tracers include [2,3,4,5,6-13C]glucose for oxidative pentose phosphate pathway flux and [3,4-13C]glucose for pyruvate carboxylase flux quantification [34]. Multi-objective optimization approaches can identify cost-effective tracer mixtures that maximize information content while minimizing experimental expenses [29].

Wet-Lab Experimental Protocol

Cell Culture and Labeling

- Preparation: Grow cells in appropriate medium until mid-exponential phase

- Labeling Medium: Replace with fresh medium containing selected 13C-tracer(s)

- For parallel labeling experiments (PLEs): Use multiple tracers in separate cultures

- Maintain metabolic steady-state through chemostat or controlled batch culture

- Sampling: Collect samples at isotopic steady-state (typically 2-3 generations for microbial systems, longer for mammalian cells)

- Quenching: Rapidly quench metabolism using cold methanol or other appropriate methods

Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

- Extraction: Use appropriate extraction buffers for intracellular metabolites

- Cold methanol/water/chloroform mixtures for comprehensive metabolite extraction

- Analysis:

- GC-MS or LC-MS: For mass isotopomer distribution (MID) analysis

- NMR: For positional isotopomer information (less common but valuable)

- Measurement:

- Extract extracellular flux data (substrate uptake, product secretion rates)

- Determine biomass composition and growth rates

- Quantify mass isotopomer distributions of intracellular metabolites

Computational Workflow

13C-MFA Flux Estimation

The core of 13C-MFA involves solving an optimization problem to find flux values that minimize the difference between simulated and measured isotopic labeling patterns:

The mathematical formulation can be represented as:

argmin:(x-xM)Σε(x-xM)T s.t. S·v = 0 M·v ≥ b A1(v)X1 - B1Y1(y1in) = dX1/dt ... [11]

Where v represents metabolic fluxes, S is the stoichiometric matrix, x is the simulated labeling pattern, and xM is the measured labeling pattern.

Flux Variability Analysis with 13C Constraints

The improved FVA algorithm incorporates 13C-derived flux constraints:

The FVA problem is formalized as:

Phase 1: Z₀ = max cTv subject to Sv = 0, vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax Phase 2: max/min vi subject to Sv = 0, cTv ≥ μZ₀, vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax [4]

Where c is the biological objective vector, Z₀ is the optimal objective value, and μ is the fractional optimality factor.

Implementation with Solution Inspection

The enhanced FVA algorithm reduces computational burden through solution inspection:

- Solve initial FBA problem to find Zâ‚€

- For each reaction i, traditionally solve 2n LPs to find min and max fluxes

- Apply solution inspection: check if intermediate LP solutions already reveal flux bounds

- Skip redundant LP calculations when bounds are already determined

- This reduces the number of LPs needed from 2n+1 to a significantly lower number [4]

Data Integration and Model Construction

Constraint Integration Framework

Integrating 13C-MFA results with genome-scale models requires careful constraint formulation:

Table 2: Types of Constraints for Genome-Scale Models

| Constraint Type | Source | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Flux Bounds | 13C-MFA flux confidence intervals | vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax |

| Flux Ratios | 13C-MFA flux correlation analysis | vi/vj = ratioij |

| Directionality | Thermodynamic constraints from 13C-MFA | vi ≥ 0 or vi ≤ 0 |

| Objective Function | Biological context | Biomass, ATP production, etc. |

Model Specification with FluxML

For reproducible model exchange, use the FluxML standard:

FluxML provides a standardized format for exchanging 13C-MFA models, ensuring reproducibility and transparency [35].

Validation and Quality Control

Statistical Validation Methods

- Goodness-of-fit testing: χ²-test between measured and simulated labeling patterns

- Flux uncertainty estimation: Monte Carlo methods or linear approximation

- Parameter identifiability analysis: Assess which fluxes are well-constrained by data

Model Selection Framework

Implement a comprehensive validation protocol:

- Compare model predictions with experimental data not used in fitting

- Test model adequacy through statistical measures

- Evaluate flux sensitivity to measurement errors

- Assess prediction accuracy for external fluxes [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled Substrates | Experimental | Carbon source for tracing metabolic fluxes | [1-13C] Glucose, [U-13C] Glucose, 13C-Glutamine |

| GC-MS System | Analytical | Measure mass isotopomer distributions | Agilent, Thermo Fisher systems |

| LC-MS System | Analytical | Measure mass isotopomer distributions | Waters, Sciex systems |

| 13CFLUX2 | Software | 13C-MFA flux estimation | OpenFLUX, INCA |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software | Constraint-based modeling and FVA | cobrapy, COBRApy |

| FluxML | Standard | Model specification and exchange | XML-based format [35] |

| MEMOTE | Software | Model quality assessment | Metabolic model testing [7] |

| Beryllium boride (BeB2) | Beryllium Boride (BeB2) Powder|High Purity | Bench Chemicals | |

| zinc 2-aminobenzenethiolate | zinc 2-aminobenzenethiolate, CAS:14650-81-8, MF:C12H10N2S2Zn-4, MW:313.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Issues and Solutions

Poor flux resolution:

Large flux confidence intervals:

- Cause: Insufficient labeling measurements

- Solution: Increase measurement points, use tandem MS, implement INST-MFA [11]

Model incompatibility:

- Cause: Differing network topologies between 13C-MFA and genome-scale model

- Solution: Use consistent reaction identifiers, validate network connectivity

Advanced Applications

- Integration with INST-MFA: For systems where metabolic steady-state cannot be achieved

- Dynamic 13C-MFA: For analyzing metabolic transitions and nonstationary conditions [8]

- Multi-omics integration: Combining flux constraints with transcriptomic and proteomic data

The integration of 13C-MFA with FVA provides a powerful framework for metabolic network analysis that combines experimental validation with comprehensive pathway exploration. This protocol outlines a standardized workflow from tracer selection to constrained FVA implementation, enabling researchers to obtain more accurate predictions of metabolic capabilities across various biological systems and conditions. The continued development of computational tools, standardized formats like FluxML, and multi-objective experimental design approaches will further enhance the applicability and reliability of this integrated approach.

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) is a fundamental constraint-based modeling technique used to determine the robustness of metabolic models under various simulation conditions. By calculating the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction in a network while maintaining a physiological state—such as supporting a specific percentage of maximal biomass production—FVA helps researchers explore network flexibility, redundancy, and alternative optimal solutions [31]. This capability makes FVA invaluable for metabolic engineering and drug development applications, including optimal strain design and investigating flux distributions under suboptimal growth conditions.

The core computational challenge of traditional FVA implementation lies in its demanding nature. For a metabolic network with n reactions of interest, FVA requires the solution of 2n linear programming (LP) problems [31]. Each of these problems finds the minimum or maximum flux for a particular reaction subject to the stoichiometric constraints and an additional constraint that ensures the biological objective is maintained: wTv ≥ γZ₀, where Z₀ is the optimal solution from an initial flux balance analysis, and γ controls whether the analysis is done with respect to suboptimal (0 ≤ γ < 1) or optimal (γ = 1) network states [31]. This requirement means that FVA computation time scales directly with network size, making it prohibitively slow for large-scale metabolic models involving thousands of biochemical reactions without specialized algorithmic approaches.

Traditional vs. Modern LP Solvers for FVA

Families of LP Algorithms

The efficiency of FVA computations depends critically on the performance of the underlying LP solver. Three principal families of LP algorithms are relevant to FVA implementations, each with distinct characteristics and performance profiles.

Table 1: Comparison of Major LP Algorithm Families for FVA

| Algorithm Family | Key Mechanism | Advantages for FVA | Limitations | Representative Solvers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplex Methods | Moves along vertices of the feasible region [36] | Returns sparse vertex solutions; efficient for sequences of problems with fixed feasible region [36] | Can be slow for very large problems; limited parallelization potential [37] | GLPK [31], CPLEX [31], Glop [36] |

| Barrier/Interior-Point Methods | Moves through interior of feasible region toward optimum [36] [37] | Polynomial-time convergence; reliable performance for large problems [36] | Solutions may not be vertices; typically requires crossover for vertex solutions [36] | CPLEX [36], Gurobi [36] |

| First-Order Methods (FOM) | Uses gradient information to guide iterations [36] [38] | Highly parallelizable; low memory requirements; scales to very large problems [36] [37] | May struggle with high accuracy requirements; sensitive to numerical issues [36] | PDLP [38] [37] |

Algorithmic Advances and GPU Acceleration

Recent algorithmic advances have significantly expanded the capabilities of LP solvers for large-scale FVA computations. The introduction of Primal-Dual Hybrid Gradient (PDHP) algorithm and its enhancement for linear programming (PDLP) represents a particular breakthrough for massive parallelization [38] [37]. PDLP improves upon standard PDHG by implementing a "restarting" mechanism that shortens the convergence path by leveraging the algorithm's cyclic behavior [38]. This approach uses predominantly matrix-vector multiplications rather than computationally expensive matrix factorizations, reducing memory requirements and making it exceptionally suitable for implementation on modern hardware architectures like GPUs [37].