Metabolic Engineering Fundamentals: From Core Concepts to Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with essential knowledge in metabolic engineering.

Metabolic Engineering Fundamentals: From Core Concepts to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with essential knowledge in metabolic engineering. Covering foundational principles, cutting-edge methodologies, optimization strategies, and validation techniques, it bridges basic science with clinical applications. The content explores how engineered metabolic pathways enable sustainable production of therapeutic compounds, drug precursors, and biomarkers, incorporating the latest advances in AI, computational modeling, and heterologous expression systems for biomedical innovation.

Core Principles and Historical Evolution of Metabolic Engineering

Metabolic engineering is a discipline dedicated to the optimization of native metabolic pathways and regulatory networks, or the assembly of heterologous metabolic pathways, for the production of targeted molecules using molecular, genetic, and combinatorial approaches [1]. The primary goal is to generate efficient microbial cell factories that produce cost-effective molecules at an industrial scale from renewable feedstocks [2] [1]. Since the term was coined in the late 1980s-early 1990s, the field has expanded substantially, moving beyond manipulations of single enzymes to encompass the holistic design and optimization of entire metabolic networks [2]. This evolution has been driven by advances in adjacent fields, including DNA sequencing, genetic tool development, and sophisticated analytical and modeling techniques [2] [3].

The applications of metabolic engineering are vast, spanning the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), specialty chemicals, biofuels, and bulk chemicals [2]. A key advantage over traditional synthetic organic chemistry is the ability to produce complex natural products that are otherwise difficult or impossible to synthesize chemically [2]. The field is guided by the central metrics of titer, yield, and rate (TYR), which have become the benchmarks for evaluating the cost-competitiveness of an engineered cell factory [1].

Core Principles and Methodologies

The practice of metabolic engineering requires the consideration of multiple, interconnected factors. Successful projects typically involve [1]:

- Selection of a Host Organism: Choosing a safe, robust host with genetic and physiological advantages for the target product (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae, or the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica).

- Pathway Understanding: Comprehensive knowledge of the metabolic pathways, co-factor balances (e.g., NADPH, ATP), and regulatory networks involved.

- Genetic Tool Availability: Access to effective enzymes, genetic elements, and efficient transformation technologies.

- Analytical and Modeling Frameworks: The use of stoichiometric, thermodynamic, and kinetic analyses to identify and overcome pathway bottlenecks.

The process can be conceptualized as an iterative Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle [1]. In this framework, computational models are used to design a cell factory, which is then constructed and tested experimentally. The resulting data is analyzed to refine the model and inform the next cycle of engineering, progressively optimizing the system [1] [3].

Key Engineering Strategies at the Network Level

Modern metabolic engineering has shifted from targeting a handful of genes to implementing complex designs requiring the modification of dozens of genes across diverse metabolic functions [1]. A systematic computational study evaluating 12,000 biosynthetic scenarios revealed that over 70% of product pathway yields can be improved by introducing appropriate heterologous reactions, and identified 13 universal engineering strategies [4]. The five most effective strategies, applicable to over 100 products, are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: High-Impact Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Breaking Stoichiometric Yield Limits

| Strategy Category | Specific Mechanism | Example Action | Key Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Conserving | Non-oxidative glycolysis (NOG) | Replaces the classic Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas glycolysis pathway [4] | Increases yield of acetyl-CoA-derived products (e.g., farnesene, PHB) [4] |

| Carbon-Conserving | Reductive TCA cycle | Assimilates COâ‚‚ and fixes it into central metabolism [4] | Enhances carbon efficiency for various products |

| Energy-Conserving | ATP-efficient pathways | Utilizes NADH-generating glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [4] | Improves ATP yield and overall metabolic efficiency |

| Energy-Conserving | Bypassing ATP-inefficient steps | Replaces phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase with an ATP-insensitive enzyme [4] | Conserves ATP, increasing energy available for biosynthesis |

| Cofactor Balancing | Transhydrogenase cycles | Shuttles reducing equivalents between NADH and NADPH pools [4] | Balances cofactor availability, relieving thermodynamic constraints |

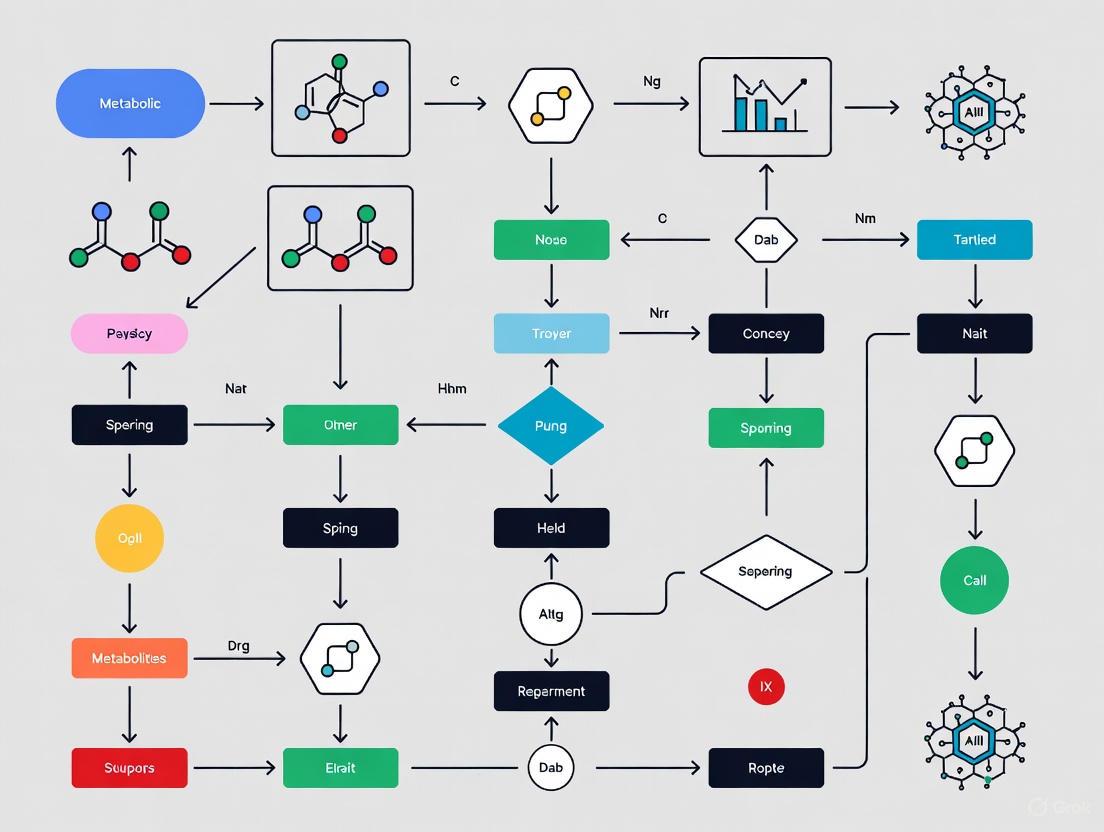

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these strategies are integrated into a modern, model-driven metabolic engineering pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Computational and Analytical Frameworks

The complexity of modern metabolic engineering necessitates a suite of sophisticated computational tools to model, predict, and analyze cellular metabolism. These tools are integral to the "Design" and "Learn" phases of the DBTL cycle.

Metabolic Modeling and Flux Analysis

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) are comprehensive representations of an organism's metabolism, integrating all metabolic reactions annotated from its genome [4]. GEMs are typically used with Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a constraint-based method that predicts steady-state metabolic fluxes to optimize a biological objective, such as biomass growth or product formation [4] [3]. For more advanced analysis, 13C-based Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is considered the gold standard for experimentally estimating intracellular metabolic fluxes. It involves culting microbes on 13C-labeled carbon substrates, measuring the resulting isotope patterns in metabolites, and using computational optimization to identify the flux distribution that best fits the experimental data [5].

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Platforms for Metabolic Engineering

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEMs + FBA [4] [3] | Predicting metabolic flux distributions | Genome-scale network reconstruction; constraint-based optimization | In silico prediction of gene knockout targets, nutrient requirements, and theoretical yield limits. |

| QHEPath [4] | Quantitative heterologous pathway design | Algorithm to identify heterologous reactions that break host's yield limit | Systematically design pathways to surpass stoichiometric yield limits of native host metabolism. |

| Fluxer [6] | Flux network visualization | Web application for FBA and visualization of GEMs as interactive graphs | Visualize major metabolic pathways and identify key routes between metabolites of interest. |

| mfapy [5] | 13C-MFA data analysis | Open-source Python package for non-linear optimization of flux distributions | Estimate intracellular fluxes from isotope labeling data; supports custom model development and experimental design. |

| CSMN [4] | Cross-species metabolic network modeling | Integrated model combining reactions from multiple organisms and databases | Serves as a universal biochemical reaction database for heterologous pathway design in non-native hosts. |

| Blestriarene A | Blestriarene A, MF:C30H26O6, MW:482.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dracaenoside F | Dracaenoside F|Supplier | Dracaenoside F is a steroidal saponin for research use. Isolated from Dracaena sp. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Visualizing Metabolic Networks and Regulation

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting the vast amounts of data generated from GEMs and flux analyses. Tools like Fluxer enable the automated visualization of complete GEMs, displaying flux distributions as spanning trees, dendrograms, or complete graphs to help researchers identify the most important pathways contributing to a product of interest [6]. Beyond fluxes, understanding regulation is key. The concept of Regulatory Strength (RS) provides a quantitative measure of how strongly a metabolite (effector) up- or down-regulates a reaction step compared to its non-regulated state [7] [8]. This allows for the visualization of inhibitory or activating interactions within a network, which is crucial for explaining why metabolic fluxes are at certain levels even when substrate and product concentrations suggest otherwise [7].

The diagram below illustrates how these computational and data layers integrate to form a comprehensive understanding of a metabolic network, from gene to function.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol for Computational Strain Design Using GEMs

This protocol outlines the use of genome-scale models to predict gene knockout targets for maximizing product yield [4] [3].

- Model Selection and Preparation: Obtain a curated GEM for your host organism (e.g., from the BiGG Models database). Ensure the model includes a reaction for the synthesis of your target product. If not, add the necessary heterologous reactions.

- Define Constraints and Objective: Set constraints to reflect the experimental conditions, such as substrate uptake rate (e.g., glucose uptake = 10 mmol/gDW/h). Define the objective function to be maximized, typically the flux through the product synthesis reaction.

- In silico Gene Deletion Analysis: Use a algorithm such as OptKnock. Perform simulations that systematically "knock out" one or more gene-associated reactions in the model while maximizing the product formation objective.

- Output and Interpretation: The algorithm will output a set of gene deletion candidates that couple product formation to growth. These predictions represent potential metabolic engineering targets.

- Validation and Iteration: Construct the proposed strain in the laboratory and characterize its performance in bioreactors. Use omics data (transcriptomics, metabolomics) from the engineered strain to refine the model and identify the next cycle of targets.

Case Studies in Industrial Production

Metabolic engineering has successfully led to the commercial production of a diverse range of molecules. Key examples include:

- 1,3-Propanediol and 1,4-Butanediol: These bulk chemicals, used as polymer precursors, are produced in engineered E. coli by DuPont and Genomatica, respectively. The engineering involved transferring genes from Klebsiella pneumoniae and S. cerevisiae into E. coli to create a novel pathway from glucose [2] [1].

- Artemisinic Acid: A precursor to the antimalarial drug artemisinin is produced in engineered S. cerevisiae by Amyris. This project involved transferring the complex biosynthetic pathway from the plant Artemisia annua into yeast, and is a prime example of how metabolic engineering can rival synthetic chemistry for producing complex APIs [2] [1].

- Advanced Biofuels: Engineered microbes now produce hydrocarbons compatible with existing infrastructure. For example, linear alkanes and alkenes for diesel and jet fuel are produced via the fatty acid biosynthetic pathway, while branched hydrocarbons are produced via the isoprenoid pathway [2]. These fuels often diffuse out of the cells and phase-separate, simplifying downstream purification [2].

Metabolic engineering has matured from a discipline focused on single-enzyme manipulations to a sophisticated field of network-level design. The integration of systems biology, computational modeling, and advanced genetics through the DBTL cycle has enabled the rational development of microbial cell factories for a sustainable bio-economy. The future of the field lies in enhancing the predictability of models by further integrating regulatory and kinetic information, improving the scale and precision of genome editing, and developing more dynamic control systems to autonomously manage metabolic resources. As these tools advance, the scope of products accessible through biological production will continue to expand, solidifying metabolic engineering as a cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology.

Metabolic engineering leverages cellular pathways to produce valuable chemicals, fuels, and therapeutics. Its foundation rests on seminal Nobel Prize-winning discoveries that have elucidated how cells convert energy, recycle components, sense their environment, and catalyze reactions. This guide synthesizes these foundational discoveries into a coherent framework for researchers and drug development professionals, connecting historical insights to modern engineering principles. By understanding the mechanistic basis of metabolism—from the central Krebs cycle to engineered enzymes—we can better design microbial cell factories and therapeutic interventions. The following sections detail the key discoveries, their experimental proofs, and the practical tools they have inspired.

Nobel Prize-Winning Discoveries in Metabolism

Several Nobel Prizes have been awarded for discoveries that form the bedrock of our understanding of cellular metabolism. The table below summarizes the most critical ones for metabolic engineering.

Table 1: Foundational Nobel Prizes in Metabolic Research

| Year | Laureate(s) | Key Discovery | Significance for Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Hans Krebs [9] | The Citric Acid Cycle (Krebs Cycle) | Defined the central pathway for the oxidation of acetyl-CoA to produce energy and precursor metabolites. |

| 1953 | Fritz Lipmann [9] | Coenzyme A and its importance for intermediary metabolism | Identified the essential cofactor (CoA) that activates metabolic intermediates, such as acetyl-CoA, for entry into the Krebs cycle. |

| 2016 | Yoshinori Ohsumi [10] | Mechanisms of Autophagy | Elucidated the pathway for cellular recycling, allowing cells to degrade and reuse cytoplasmic components, a key consideration in cellular efficiency. |

| 2019 | W. G. Kaelin Jr., P. J. Ratcliffe, G. L. Semenza [11] | Oxygen-sensing mechanism of cells via the HIF-1α pathway | Revealed how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability, a critical factor in large-scale bioreactor fermentations and tumor metabolism. |

| 2018 | Frances H. Arnold [12] [13] | Directed evolution of enzymes | Pioneered a method to engineer highly efficient and novel enzymes for industrial catalysis, including the synthesis of pharmaceuticals and biofuels. |

Detailed Analysis of Key Discoveries

The Krebs Cycle and Coenzyme A: The Energetic Core

The 1953 Nobel Prize awarded to Hans Krebs and Fritz Lipmann established the core of energetic metabolism [9]. Krebs identified the cyclic metabolic pathway that converts the energy in carbohydrates, fats, and proteins into usable chemical energy. Lipmann discovered coenzyme A (CoA), the critical molecule that "activates" metabolic fragments, most notably two-carbon acetyl groups, for entry into this cycle.

- Molecular Mechanism: The Krebs cycle occurs in the mitochondrial matrix. Acetyl-CoA, the activated form of acetate, condenses with oxaloacetate (a four-carbon compound) to form citrate. Through a series of eight enzymatic steps, citrate is progressively decarboxylated and oxidized, regenerating oxaloacetate. These reactions produce ATP, the high-energy electron carriers NADH and FADH2, and CO2. NADH and FADH2 then feed electrons into the electron transport chain to drive the production of most of the cell's ATP.

- Experimental Foundation: Krebs's work involved studying the oxygen consumption of pigeon breast muscle suspensions. By adding various suspected metabolic intermediates and measuring their effect on the rate of oxygen consumption, he was able to deduce the cyclic nature of the pathway. Lipmann's discovery of Coenzyme A was the result of persistent biochemical fractionation and experimentation, isolating the heat-stable cofactor necessary for the acetylation of sulfonamides.

- Metabolic Engineering Context: The Krebs cycle is a primary source of precursor metabolites for biosynthesis. To engineer a cell for high-yield production of a target compound, one must often divert carbon flux away from the Krebs cycle. This requires a deep understanding of its regulation and the availability of key intermediates like α-ketoglutarate (for glutamate synthesis) and oxaloacetate (for amino acid and lysine synthesis).

Autophagy: Cellular Recycling and Quality Control

Yoshinori Ohsumi's 2016 Nobel Prize-winning work defined the molecular mechanisms of autophagy, a fundamental process for degrading and recycling cellular components [10].

- Molecular Mechanism: Autophagy (meaning "self-eating") involves the sequestration of cytoplasmic cargo (damaged organelles, protein aggregates) within a double-membraned vesicle called an autophagosome. The autophagosome then fuses with the lysosome (or vacuole in yeast) to form an autolysosome, where the encapsulated contents are degraded by hydrolases and the resulting macromolecules are recycled back into the cytoplasm.

- Experimental Foundation: Ohsumi's groundbreaking experiment used baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as a model. He engineered mutant yeast strains lacking vacuolar degradation enzymes and then starved the cells to induce autophagy. Under the microscope, he observed the accumulation of non-degraded autophagosomes within the vacuole, proving the existence of autophagy in yeast. This visual assay provided a powerful tool for his subsequent screening of yeast mutants, which led to the identification of the first essential autophagy genes (ATG genes) [10].

- Metabolic Engineering Context: In bioproduction, autophagy can be a double-edged sword. It can be engineered to recycle nutrients during stress, sustaining cell viability and productivity in long-term fermentations. Conversely, it can also degrade engineered enzymes or pathway intermediates. Understanding and controlling autophagic flux is therefore crucial for optimizing microbial cell factory performance.

Oxygen Sensing: The HIF Pathway and Metabolic Adaptation

The 2019 Nobel Prize to William G. Kaelin Jr., Sir Peter J. Ratcliffe, and Gregg L. Semenza was for their discovery of how cells sense and adapt to oxygen availability [11].

- Molecular Mechanism: The central player is the transcription factor HIF (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor). Under normal oxygen levels (normoxia), HIF-α subunits are continuously synthesized but rapidly degraded. This degradation is triggered by oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), which mark HIF-α for recognition by the VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, leading to its proteasomal degradation. Under low oxygen (hypoxia), PHD activity is inhibited, allowing HIF-α to stabilize, enter the nucleus, dimerize with HIF-β, and activate the transcription of hundreds of genes involved in angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, and metabolic adaptation [11].

- Metabolic Adaptation: A key metabolic shift induced by HIF is the switch from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis. HIF activates genes for glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes while suppressing mitochondrial function. This allows cells to generate ATP without consuming oxygen, a critical adaptation in solid tumors and ischemic tissues.

- Experimental Foundation: Key experiments included Semenza's identification of HIF binding to the EPO gene enhancer, Ratcliffe's demonstration of the ubiquitous nature of oxygen sensing, and Kaelin's discovery that the VHL tumor suppressor protein was necessary for HIF degradation. The final piece was the simultaneous discovery by both Ratcliffe and Kaelin that oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylation is the signal for VHL binding [11].

- Metabolic Engineering Context: Oxygen availability is a major scale-up challenge in industrial bioreactors. Understanding the HIF pathway provides insights into how production cells (including mammalian cell cultures) respond to hypoxic pockets in large fermenters. Engineering strategies may involve modulating HIF pathway components to enhance cell viability and product yield under sub-optimal oxygen conditions.

Diagram: The HIF Oxygen-Sensing Pathway

Directed Evolution of Enzymes: Engineering Novel Catalysts

Frances H. Arnold was awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for pioneering the directed evolution of enzymes, a method that allows engineers to create optimized biocatalysts for specific industrial processes [12] [13].

- Core Principle: Directed evolution mimics natural selection in a laboratory setting. It involves iterative rounds of (1) introducing genetic diversity into a protein-coding gene and (2) screening or selecting the resulting variant proteins for the desired enhanced or novel function.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Gene Diversification: The gene of interest is mutated using methods like error-prone PCR to create a large library of variants.

- Expression: The gene library is expressed in a host system (e.g., bacteria).

- Screening/Selection: The population is subjected to a high-throughput screen or selection that identifies variants with improved performance (e.g., activity in organic solvents, higher thermostability, or novel catalytic function).

- Gene Amplification: The genes from the best-performing variants are isolated and used as the template for the next round of evolution.

- Metabolic Engineering Context: Directed evolution is a powerful tool for creating custom enzymes that are not found in nature. This allows metabolic engineers to design new biosynthetic pathways or optimize existing ones. Examples cited for Arnold's work include evolving enzymes for the environmentally friendly production of pharmaceuticals and the biosynthesis of renewable biofuels like isobutanol [13].

Diagram: The Directed Evolution Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Protocols

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Modern metabolic research relies on a suite of reagents and tools to probe pathway function.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose | Glycolysis Inhibitor | Competitively inhibits hexokinase, allowing measurement of glycolytic dependency in ATP production assays [14]. |

| Oligomycin A | ATP Synthase Inhibitor | Inhibits mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, allowing quantification of its contribution to total ATP production [14]. |

| Metformin | AMPK Activator / Complex I Inhibitor | Induces metabolic stress and is used to study cellular adaptation to energy deprivation, relevant in cancer and diabetes research [14]. |

| Luminescent ATP Assay | Quantify Cellular ATP Levels | Provides a high-throughput, direct readout of cellular energy status after metabolic perturbation [14]. |

| Metabolic Pathway Databases (KEGG, MetaCyc) | Reference for Pathway Reconstruction | Provide curated maps of metabolic reactions and pathways across different organisms, essential for pathway comparison and design [15]. |

| 16-Deoxysaikogenin F | 16-Deoxysaikogenin F, MF:C30H48O3, MW:456.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Alpinumisoflavone acetate | Alpinumisoflavone acetate, MF:C22H18O6, MW:378.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A Representative Experimental Protocol: Metabolic Dependency Analysis

A 2024 protocol provides a modern method for analyzing the relative contribution of different metabolic pathways to ATP production, a key question in metabolic engineering and cancer biology [14]. This method is high-throughput and directly measures ATP, the functional energy output.

Protocol: Analyzing Energy Metabolic Pathway Dependency [14]

- Cell Seeding: Harvest and count cells (e.g., HepG2 liver carcinoma cell line). Seed cells at a uniform density in a 96-well plate.

- Perturbation/Treatment: Treat cells with the compound of interest (e.g., Metformin) to perturb metabolism. Include appropriate control groups.

- Systematic Metabolic Inhibition: In a separate plate, treat cells with a panel of specific metabolic inhibitors to block specific pathways:

- Glycolysis Inhibition: Use 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose.

- Oxidative Phosphorylation Inhibition: Use Oligomycin A.

- Other inhibitors can target fatty acid oxidation or amino acid metabolism.

- Viability and ATP Assay: After an incubation period, assay each well for both cell viability (e.g., using an XTT-based assay) and ATP content (using a luminescent ATP detection assay kit).

- Data Calculation and Analysis:

- Normalize the luminescent ATP readings to the cell viability data to obtain a viability-corrected ATP level.

- Calculate the dependency on a specific pathway using the following type of calculation:

- Glycolytic Capacity = (ATP level from untreated cells - ATP level after Oligomycin treatment) / (ATP level from untreated cells)

- The results provide a quantitative profile of how a cell relies on different pathways for its energy needs.

The journey from foundational Nobel Prize discoveries to modern metabolic engineering is a powerful demonstration of how basic biological research enables technological innovation. The discovery of core pathways like the Krebs cycle and autophagy, the elucidation of sensory systems like the HIF oxygen-sensing pathway, and the development of powerful engineering tools like directed evolution provide a comprehensive toolkit for today's researchers. By integrating these historical foundations with contemporary high-throughput protocols and computational analyses, scientists can continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in the production of renewable chemicals, advanced biofuels, and next-generation therapeutics.

Central carbon metabolism (CCM) constitutes the fundamental biochemical network responsible for the conversion of carbon-containing molecules into energy, reducing power, and precursor metabolites essential for cell growth, proliferation, and survival [16]. This network acts as the core "processing hub" within the cell, tightly linking numerous catabolic and anabolic processes [17]. For researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development, a rigorous understanding of CCM is indispensable. It provides the foundational knowledge required to rationally redesign microbial hosts for the sustainable production of valuable chemicals, biofuels, and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [2]. The core of CCM primarily comprises three interconnected pathways: Glycolysis (the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, or EMP pathway), the Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle, and the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) [17] [16]. These pathways collectively transform simple sugars into a diverse set of metabolic intermediates that serve as building blocks for biosynthesis.

Table 1: Core Components of Central Carbon Metabolism

| Pathway Name | Primary Function | Key Inputs | Key Outputs | Cellular Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis (EMP) | Glucose breakdown to pyruvate, net ATP/NADH production | Glucose, ATP, NAD+ | Pyruvate, ATP, NADH | Cytoplasm |

| TCA Cycle | Complete oxidation of acetyl-CoA, high-yield NADH/FADH2 generation | Acetyl-CoA, NAD+, FAD, GDP/ADP | ATP/GTP, NADH, FADH2, CO2 | Mitochondrial Matrix |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | Generation of NADPH and pentose sugars | Glucose-6-phosphate, NADP+ | Ribose-5-phosphate, NADPH, CO2 | Cytoplasm |

The Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) Pathway: Glycolysis

Glycolysis is a universal metabolic pathway involving the ten-step conversion of a single glucose molecule into two pyruvate molecules within the cytoplasm [17]. This process is divided into two distinct phases: an energy-investment phase and an energy-payoff phase.

Experimental Analysis of Glycolytic Flux

A key methodology for quantifying flux through glycolysis is Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA). This technique relies on feeding cells substrates labeled with stable isotopes (e.g., ^13C-glucose) and tracking the incorporation of these labels into downstream metabolites using mass spectrometry [16] [18]. The resulting isotopic distribution data allows for the quantitative determination of intracellular metabolic reaction rates. For dynamic profiling, Fluxomics approaches combine this isotopic labeling with mathematical models, such as flux balance analysis (FBA), to estimate the flow of metabolites through the network under different genetic or environmental perturbations [16].

Table 2: Glycolysis (EMP Pathway) Reaction Sequence and ATP Balance

| Step | Reactants | Products | Enzyme | ATP/NADH Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glucose | Glucose-6-phosphate | Hexokinase | -1 ATP |

| 2 | Glucose-6-phosphate | Fructose-6-phosphate | Phosphohexose isomerase | - |

| 3 | Fructose-6-phosphate | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate | Phosphofructokinase-1 | -1 ATP |

| 4 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) & Dihydroxyacetone phosphate | Aldolase | - |

| 5 | Dihydroxyacetone phosphate | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) | Triose phosphate isomerase | - |

| 6 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate + NAD+ | 1,3-Bisphosphoglycerate + NADH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | +2 NADH* |

| 7 | 1,3-Bisphosphoglycerate + ADP | 3-Phosphoglycerate + ATP | Phosphoglycerate kinase | +2 ATP |

| 8 | 3-Phosphoglycerate | 2-Phosphoglycerate | Phosphoglycerate mutase | - |

| 9 | 2-Phosphoglycerate | Phosphoenolpyruvate | Enolase | - |

| 10 | Phosphoenolpyruvate + ADP | Pyruvate + ATP | Pyruvate kinase | +2 ATP |

| Net Yield per Glucose | 2 ATP, 2 NADH, 2 Pyruvate |

Note: Values account for the doubling of all molecules from one glucose to two G3P molecules.

The Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle

The TCA cycle, also known as the Krebs or citric acid cycle, is the central aerobic hub for oxidizing acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins [19]. Located in the mitochondrial matrix, it completes the energy-yielding oxidation of carbon fuels and provides key precursors for biosynthesis [17].

Protocol: Investigating Cycle Activity with Isotope Tracing

The operation of the TCA cycle can be studied using ^13C-glutamine or ^13C-glucose tracing followed by analysis via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). Cells are cultured in media containing the labeled substrate. Metabolites are then extracted and analyzed to determine the ^13C enrichment pattern in TCA cycle intermediates (e.g., citrate, α-ketoglutarate, succinate). The mass isotopomer distributions reveal the relative flux through various segments of the cycle and ancillary pathways, such as reductive carboxylation, which is often upregulated in cancer cells [16].

Table 3: TCA Cycle Reactions and Energy Carriers Generated

| Step | Reaction | Enzyme | Energy Carriers Produced | Type of Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Oxaloacetate + Acetyl-CoA → Citrate | Citrate synthase | - | Aldol condensation |

| 1 | Citrate cis-Aconitate Isocitrate | Aconitase | - | Dehydration/Hydration |

| 2 | Isocitrate + NAD+ → α-Ketoglutarate + CO2 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | 1 NADH | Oxidative decarboxylation |

| 3 | α-Ketoglutarate + NAD+ + CoA → Succinyl-CoA + CO2 | α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase | 1 NADH | Oxidative decarboxylation |

| 4 | Succinyl-CoA + GDP/Pi → Succinate + GTP/ATP | Succinyl-CoA synthetase | 1 GTP/ATP | Substrate-level phosphorylation |

| 5 | Succinate + Ubiquinone (Q) → Fumarate | Succinate dehydrogenase | 1 FADH2 (as QH2) | Oxidation |

| 6 | Fumarate + H2O → L-Malate | Fumarase | - | Hydration |

| 7 | L-Malate + NAD+ → Oxaloacetate + NADH | Malate dehydrogenase | 1 NADH | Oxidation |

| Total per Acetyl-CoA | 3 NADH, 1 FADH2, 1 GTP/ATP |

The Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP)

The PPP operates in the cytoplasm parallel to glycolysis and serves two critical biosynthetic roles: generating ribose-5-phosphate for nucleotide synthesis and producing NADPH for reductive biosynthesis and oxidative stress defense [17] [16]. The pathway consists of an oxidative and a non-oxidative phase.

Methodology: Quantifying NADPH Production via the PPP

The flux through the oxidative branch of the PPP can be specifically measured by monitoring the release of ^14CO2 from glucose labeled at the C1 position (1-^14C-glucose). As the first step of the PPP is the decarboxylation of glucose-6-phosphate, the amount of CO2 released from C1 is directly proportional to PPP activity. This can be compared to CO2 release from other labeled positions (e.g., 6-^14C-glucose) to differentiate PPP flux from glycolytic flux [16].

Table 4: Pentose Phosphate Pathway Phases and Outputs

| Phase | Key Reactions | Key Enzymes | Primary Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative | Glucose-6-phosphate → 6-Phosphoglucono-δ-lactone | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | 2 NADPH (per G6P entering oxidative phase) |

| 6-Phosphoglucono-δ-lactone → 6-Phosphogluconate | Lactonase | ||

| 6-Phosphogluconate → Ribulose-5-phosphate + CO2 | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 1 Ribulose-5-phosphate | |

| Non-Oxidative | Ribulose-5-phosphate Ribose-5-phosphate Xylulose-5-phosphate | Pentose phosphate isomerase & epimerase | Various sugar phosphates (C3, C4, C5, C6, C7) |

| Transketolase & Transaldolase Reactions | Transketolase, Transaldolase | Fructose-6-phosphate, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate |

Regulation of Central Metabolic Pathways

The flux through central carbon metabolism is precisely controlled via multiple regulatory mechanisms to maintain metabolic homeostasis and respond to cellular energy demands and nutrient availability [17] [16].

Allosteric Regulation: Key enzymes are modulated by effectors that signal the cell's energy status. For instance, phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), the rate-limiting enzyme of glycolysis, is allosterically inhibited by high levels of ATP and activated by AMP, signaling low energy [17] [16]. Similarly, citrate synthase, the first enzyme of the TCA cycle, is inhibited by ATP and succinyl-CoA [17].

Covalent Modification: Enzyme activity is rapidly and reversibly modified through processes like phosphorylation. Glycogen synthase is inhibited by phosphorylation, redirecting carbon flow away from storage and into glycolysis when energy is needed [17].

Feedback Inhibition: The end-products of pathways inhibit earlier steps. Accumulation of ATP feeds back to inhibit PFK-1, preventing excessive glycolysis when energy is abundant [17] [16].

Substrate Availability: High glucose concentrations activate hexokinase, driving glucose into the metabolic network [17].

Metabolic Engineering Applications and Experimental Workflow

Metabolic engineering applies a Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle to construct efficient microbial cell factories for producing molecules ranging from biofuels to pharmaceuticals [1] [2]. Central carbon metabolism is a primary target for these engineering efforts.

A Metabolic Engineering DBTL Workflow

A standard DBTL cycle for engineering CCM involves [1]:

- Design: Using genomic and modeling tools (e.g., Flux Balance Analysis on a Genome-Scale Model, or GSM) to identify gene knockout, knockdown, or overexpression targets to redirect flux toward a desired product.

- Build: Employing molecular biology techniques (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9, promoter engineering, gene assembly) to implement the genetic modifications in a host organism (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae, or the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica).

- Test: Culturing the engineered strain and applying analytical techniques like LC-MS, NMR, and stable isotope tracing (e.g., with ^13C-glucose) to measure metabolite levels, product titer, yield, productivity (TYR metrics), and actual metabolic fluxes (MFA).

- Learn: Analyzing the T&L data to identify unforeseen bottlenecks (e.g., regulatory issues, toxic intermediate accumulation, cofactor imbalances) and inform the next round of design.

Success Stories in Metabolic Engineering

- Artemisinic Acid: The precursor to the antimalarial drug artemisinin is now produced in engineered S. cerevisiae by integrating plant-derived genes into the host's native isoprenoid pathway, which draws on acetyl-CoA from central metabolism [2].

- 1,3-Propanediol and 1,4-Butanediol: These bulk chemicals are commercially produced in engineered E. coli by introducing heterologous pathways that divert central metabolic intermediates like dihydroxyacetone phosphate (glycolysis) and succinyl-CoA (TCA cycle) [1] [2].

- Advanced Biofuels: Hydrocarbons with properties similar to diesel and jet fuel have been produced by engineering the fatty acid (from acetyl-CoA) and isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways in various microbial hosts [2].

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ^13C-labeled Substrates (e.g., ^13C-Glucose, ^13C-Glutamine) | Stable isotope tracers for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Quantifying carbon flow and pathway fluxes in live cells [16]. |

| LC-MS / GC-MS Systems | Analytical instruments for identifying and quantifying metabolites | Measuring concentrations and ^13C isotopic enrichment in metabolic intermediates [16] [20]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models of an organism's entire metabolism | Predicting growth phenotypes, gene essentiality, and optimal genetic modifications in silico [21] [18]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Tools | For precise genome editing (knockouts, knock-ins, point mutations) | Engineering microbial hosts to delete competing pathways or insert heterologous genes [1]. |

| KEGG / MetaCyc Databases | Curated databases of metabolic pathways and enzymes | Retrieving reference pathways and enzyme information for pathway design [22]. |

| Metabolic Network Tools (e.g., MetaDAG, GEMsembler) | Software for reconstructing, visualizing, and comparing metabolic networks | Analyzing and comparing metabolic networks across different organisms or conditions [22] [21]. |

This guide provides an in-depth examination of the primary molecular carriers of metabolic energy and reducing power: adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). Framed within the context of metabolic engineering, this resource is designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking a foundational understanding of these crucial cofactors. Cellular metabolism encompasses thousands of reactions necessary for growth and proliferation, requiring both Gibbs free energy and molecular building blocks [23]. ATP and NADH sit at the core of this network, serving as universal currencies for energy transfer and redox reactions. Their fundamental principles are foundational for efforts in metabolic engineering, which modifies and optimizes biochemical pathways in microorganisms to produce valuable compounds [24]. A thorough grasp of their function is essential for designing new biochemical pathways or redesigning existing ones for applications in biofuel, pharmaceutical, and chemical production.

Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP): The Primary Energy Currency

Structure and Chemical Properties

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a nucleoside triphosphate consisting of three primary components: a nitrogenous base (adenine), the sugar ribose, and a triphosphate group [25]. The triphosphate unit comprises three phosphoryl groups labeled alpha (α), beta (β), and gamma (γ) [25]. In neutral aqueous solutions at physiological pH, ATP exists primarily as the ion ATPâ´â» [25]. A key property is its ability to bind divalent metal cations, particularly magnesium (Mg²âº), with high affinity. The resulting ATP-Mg²⺠complex is the predominant cellular form and is crucial for most enzymatic interactions involving ATP [25].

Energetics of ATP Hydrolysis

The hydrolysis of ATP is a highly exergonic reaction that provides the driving force for countless cellular processes.

- Hydrolysis to ADP: ATP + H₂O → ADP + Pi with ΔG°' = -30.5 kJ/mol (-7.3 kcal/mol) [25]

- Hydrolysis to AMP: ATP + H₂O → AMP + PPi with ΔG°' = -45.6 kJ/mol (-10.9 kcal/mol) [25]

Under actual intracellular conditions, where the ATP/ADP ratio is maintained far from equilibrium, the free energy change (ΔG) for ATP hydrolysis is even more favorable, reaching approximately -57 kJ/mol (-12 kcal/mol) [25] [26]. This significant release of free energy qualifies the phosphoanhydride bonds in ATP as "high-energy bonds," not because of special chemical properties, but because their hydrolysis releases a large amount of usable energy under cellular conditions [26].

ATP-Dependent Coupling of Metabolic Reactions

ATP functions as a universal energy currency by coupling its exergonic hydrolysis to endergonic biochemical reactions, making them thermodynamically favorable. A classic example is the first reaction in glycolysis, the conversion of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate [26]. This reaction is energetically unfavorable on its own (ΔG°′= +3.3 kcal/mol) but becomes favorable when coupled to ATP hydrolysis (ΔG°′= -7.3 kcal/mol), yielding a net ΔG°′ of -4.0 kcal/mol for the coupled reaction [26]. This coupling mechanism is universal across living cells, allowing ATP to drive essential processes including muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, active transport, and biosynthesis of macromolecules [25] [26].

Table 1: Standard Free Energy of ATP Hydrolysis Under Different Conditions

| Reaction | Conditions | ΔG°' (kJ/mol) | ΔG°' (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP → ADP + Pi | Standard Biochemical Conditions | -30.5 | -7.3 |

| ATP → AMP + PPi | Standard Biochemical Conditions | -45.6 | -10.9 |

| ATP → ADP + Pi | Typical Cellular Conditions | ~ -57 | ~ -12 |

NADH: The Key Electron Carrier in Redox Reactions

Structure and Redox Function

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) exists in two interconvertible forms: the oxidized form (NADâº) and the reduced form (NADH). Its primary role is to serve as a reversible carrier of reducing equivalents (electrons and protons) in metabolic pathways. The nicotinamide ring is the active site where a hydride ion (Hâ») is transferred during redox reactions. This reversible reduction of NAD⺠to NADH is central to metabolic energy extraction.

Generation and Utilization in Catabolic Pathways

NADH is predominantly generated during the oxidative phases of catabolism. Key generating reactions include:

- Glycolysis: Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate is oxidized to 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, coupled to the reduction of NAD⺠to NADH [26].

- Citric Acid Cycle: Multiple steps within the mitochondrial matrix involve oxidation of substrates like isocitrate, α-ketoglutarate, and malate, producing NADH [27].

The reducing power of NADH is primarily utilized in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. NADH donates its electrons to Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase), initiating the process of oxidative phosphorylation [27]. This electron transfer is crucial for establishing the proton gradient that drives ATP synthesis.

Energy Equivalency of NADH

The oxidation of NADH is a highly exergonic reaction. The transfer of a pair of electrons from NADH to oxygen has a standard free energy change (ΔG°′) of -52.5 kcal/mol [27]. This substantial release of energy is harnessed gradually as electrons pass through the electron transport chain. This process ultimately leads to the synthesis of approximately 2.5 to 3 molecules of ATP per NADH molecule oxidized, depending on the organism and specific cellular conditions [27]. This quantitative relationship is fundamental for calculating metabolic yields.

Integrated Metabolic Pathways and Energy Yield

The complete oxidation of glucose demonstrates the integrated roles of ATP and NADH in energy metabolism. The process involves three major stages: glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation.

Glycolysis: Substrate-Level Phosphorylation

In the cytosol, glycolysis breaks down one glucose molecule into two pyruvate molecules, yielding a net gain of 2 ATP molecules and 2 NADH molecules [26]. This ATP is produced via substrate-level phosphorylation, where a high-energy phosphate is directly transferred to ADP from a metabolic intermediate like 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate or phosphoenolpyruvate [26] [27].

Oxidative Phosphorylation: Chemiosmotic Coupling

The majority of ATP from glucose oxidation is generated through oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria. This process involves two coupled phases:

- Electron Transport Chain: Electrons from NADH (and FADHâ‚‚) are transferred through a series of protein complexes (I-IV) in the inner mitochondrial membrane. This exergonic electron flow is coupled to the active pumping of protons from the matrix to the intermembrane space, creating an electrochemical gradient [27].

- ATP Synthesis: The potential energy stored in the proton gradient is harvested by ATP synthase (Complex V). The energetically favorable flow of protons back into the matrix through ATP synthase drives the mechanical rotation of its subunits, catalyzing the synthesis of ATP from ADP and Pi—a process known as chemiosmotic coupling [27].

The complete oxidation of one glucose molecule via glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation yields approximately 30-32 molecules of ATP [27]. This high yield underscores the efficiency of cellular respiration in harnessing the energy stored in nutrient molecules through the coordinated action of ATP, NADH, and other cofactors.

Diagram 1: Central Energy Metabolism Pathway

Quantitative Analysis of Energy Equivalents

Understanding the quantitative yield of ATP from different substrates and cofactors is critical for metabolic flux analysis and pathway engineering. The following table summarizes key energy equivalents in central metabolism.

Table 2: Energy Equivalents and ATP Yield in Glucose Metabolism

| Molecule / Pathway | ATP Yield (Molecules per Glucose) | Primary Metabolic Process |

|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis (Net) | 2 | Substrate-Level Phosphorylation |

| NADH from Glycolysis | 3-5* | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| NADH from Citric Acid Cycle | 15 | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| FADHâ‚‚ from Citric Acid Cycle | 3 | Oxidative Phosphorylation |

| Citric Acid Cycle (GTP) | 2 | Substrate-Level Phosphorylation |

| Total from Complete Oxidation | 30-32 | Combined Processes |

Note: The yield depends on the shuttle system used to transfer electrons from cytosolic NADH into the mitochondria.

Table 3: Standard Free Energy Changes of Key Metabolic Reactions

| Reaction | ΔG°' (kJ/mol) | ΔG°' (kcal/mol) | Location/Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose + 6 O₂ → 6 CO₂ + 6 H₂O | -2870 | -686 | Overall Cellular Respiration |

| ATP → ADP + Pi | -30.5 | -7.3 | Universal |

| PEP → Pyruvate | -61.9 | -14.8 | Glycolysis |

| 1,3-BPG → 3-PG | -49.3 | -11.8 | Glycolysis |

| NADH + ½ O₂ → NAD⺠+ H₂O | -219.7 | -52.5 | Electron Transport Chain |

Metabolic Engineering Applications and Protocols

Foundational Principles in Metabolic Engineering

Metabolic engineering is "the modification and optimization of metabolic pathways, mainly in microorganisms, by altering genes, nutrient uptake, or metabolic flow to allow the production of novel compounds" [24]. The field relies on a systematic approach, often involving an analytical phase (pathway analysis) followed by a synthesis phase (pathway modification) [24]. A core principle is the redirection of metabolic flux toward a desired product, which requires a deep understanding of the energy and redox balances governed by ATP and NADH.

Essential Research Reagents and Host Organisms

Successful metabolic engineering relies on a standardized toolkit of reagents and host organisms.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Organism | Function / Characteristic | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Model bacterium; rapid growth; well-established genetic tools [24] | Production of interferon, insulin, growth hormone [24] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Baker's yeast; non-pathogenic; established fermentation technology [24] | Biosynthesis of isoprenoids; lactic acid production [24] |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Precision genome editing for gene knockout, knockdown, or insertion [24] | Deleting competing pathways or inserting heterologous genes |

| Plasmid Vectors | Carriers for introducing foreign genetic material into a host organism [24] | Expressing enzymes from a non-host organism to extend a pathway |

| Analytical Tools (e.g., LC-MS, GC-MS) | Tracking metabolites and quantifying pathway fluxes [24] [28] | Identifying metabolic bottlenecks during strain development |

Protocol: Computational Modeling of Metabolic Pathways

Computational models are indispensable for predicting the behavior of engineered metabolic systems before laboratory implementation.

Objective: To create a quantitative model of a target biochemical pathway for in silico analysis and optimization. Methodology:

- System Definition: Define the set of reactants (species and enzymes) and the stoichiometry of all reactions in the pathway [28].

- Kinetic Law Selection: Assign appropriate kinetic laws (e.g., Mass-Action, Michaelis-Menten) to each reaction. Mass-action kinetics are often suitable for initial modeling, where the reaction rate is proportional to reactant concentrations [28].

- Model Representation: Represent the network, for instance, using a Petri net formalism. Basic component patterns can be defined, such as a binding reaction (P1 + P2 → P3) and an unbinding reaction (P3 → P1* + P2*) [28].

- Parameterization: Populate the model with kinetic rate constants, which can be obtained from literature, databases, or experimental fitting [29].

- Simulation and Analysis: Use a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to simulate the system's dynamics over time. Analyze flux distributions and identify control points [28] [23].

- Uncertainty Quantification and Experimental Design: Apply Bayesian optimal experimental design (BOED) to identify which experimental measurements would most effectively reduce uncertainty in model predictions, thereby guiding efficient laboratory work [29].

Diagram 2: Metabolic Engineering Workflow

Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of ATP and NADH in Cultured Cells

Measuring intracellular ATP and NADH/NAD⺠ratios is crucial for assessing the metabolic state of engineered strains.

Objective: To quantify the energy and redox states of microbial production hosts under different fermentation conditions. Materials:

- Cell Culture: Engineered E. coli or S. cerevisiae strain.

- ATP Assay Kit: Luciferin-luciferase based bioluminescence assay.

- NAD/NADH Assay Kit: Enzymatic cycling assay.

- Quenching Solution: Cold methanol or perchloric acid for rapid metabolite arrest.

- Cell Disruption System: Bead beater or sonicator.

- Luminometer or Plate Reader: For detecting assay signals.

Procedure:

- Culture and Sampling: Grow the engineered host in a controlled bioreactor. At defined time points (e.g., during exponential growth and production phase), rapidly extract a known volume of culture.

- Metabolite Quenching: Immediately quench the sample in cold quenching solution (-40°C methanol) to instantaneously halt all metabolic activity and preserve in vivo metabolite levels.

- Metabolite Extraction: Pellet the quenched cells and resuspend in an appropriate extraction buffer to release intracellular ATP and NAD(H). Use separate extraction protocols for NAD⺠and NADH to preserve the in vivo ratio (e.g., acidic extraction for NADâº, basic for NADH).

- Assay Performance: Follow the specific protocols of the commercial assay kits.

- For ATP: Mix the sample with luciferase reagent and measure the resulting bioluminescence, which is proportional to ATP concentration.

- For NAD/NADH: Use enzymatic reactions that reduce a tetrazolium salt to a colored formazan product, the formation of which is proportional to the concentration of NAD(H).

- Data Analysis: Calculate concentrations by comparing sample readings to standard curves. Normalize values to cell density (OD₆₀₀) or protein content. The NADH/NAD⺠ratio is a key indicator of the cellular redox state.

ATP and NADH are fundamental cofactors that power and regulate cellular metabolism. ATP serves as the universal energy currency, with its hydrolysis driving endergonic processes, while NADH acts as a central carrier of reducing power, feeding electrons into the energy-yielding pathway of oxidative phosphorylation. Their quantitative yields and interactions form the basis for calculating metabolic efficiency. In metabolic engineering, manipulating the pathways that generate and consume these cofactors is a primary strategy for optimizing the production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and renewable chemicals. A deep, quantitative understanding of ATP and NADH is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for the rational design of efficient microbial cell factories.

The selection of an appropriate host organism is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering and biopharmaceutical development. These microbial cell factories are engineered to produce complex molecules, from life-saving therapeutic proteins to high-value industrial compounds. The field primarily relies on two well-established microbial workhorses: the prokaryotic bacterium Escherichia coli and various eukaryotic yeast species. Each platform offers a distinct set of advantages and limitations based on its unique cellular machinery, post-translational capabilities, and cultivation requirements. Understanding the core characteristics of these hosts is essential for designing efficient metabolic pathways, optimizing bioprocesses, and successfully bringing new products from the laboratory to the market. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of E. coli and yeast platforms, compares their capabilities through structured data, outlines key experimental methodologies for their engineering, and explores emerging trends shaping the future of microbial biotechnology.

Comparative Analysis of Major Production Platforms

Escherichia coli Platforms

Escherichia coli is one of the most widely used and well-understood prokaryotic hosts for recombinant protein production and metabolic engineering. Its rapid growth, high achievable cell densities, and extensive genetic toolbox make it a default choice for many applications [30]. The genetics of E. coli are the most comprehensively understood in the microbial world, facilitating straightforward genetic manipulation [30]. A key advantage of this platform is the rapid strain development cycle; a microbial strain for heterologous protein production can be developed in as little as four weeks, and short fermentation batch cycles (around one week) make it highly attractive for fast-paced development and production [30].

However, E. coli, being a prokaryote, lacks the cellular machinery for performing eukaryotic post-translational modifications, such as glycosylation, which is essential for the activity and stability of many therapeutic proteins [30]. It is also prone to forming inclusion bodies—aggregates of misfolded protein—which can complicate downstream processing, although this can sometimes be an advantage for initial product concentration and isolation. Recent research continues to expand E. coli's capabilities, as demonstrated by the engineering of the E. coli W strain for enhanced flavonoid glycosylation. This strain shows superior tolerance to toxic substrates and, when optimized through Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) and metabolic engineering, can efficiently utilize sucrose to produce high-value compounds like chrysin-7-O-glucoside at bench-scale titers reaching 1844 mg/L [31].

Yeast Platforms

Yeasts, as eukaryotic organisms, bridge the gap between simple bacterial systems and complex mammalian cell cultures. The most common yeast species used in production include Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Komagataella phaffii (formerly Pichia pastoris), and Hansenula polymorpha [32]. Yeasts offer several practical advantages, including ease of genetic engineering, rapid growth, high biomass yield, and the absence of endotoxins [32]. A significant advantage over E. coli is their ability to perform certain post-translational modifications and secrete correctly folded proteins into the culture supernatant, simplifying downstream purification [30].

S. cerevisiae has a long history of safe use in food and pharmaceutical production, with commercialized vaccines for hepatitis B and human papillomavirus (HPV) [32]. K. phaffii has gained prominence due to its strong, inducible promoters like AOX1, which enable very high levels of protein expression—sometimes constituting up to 30% of total cell protein [32]. It can achieve high cell densities and high product titers of secreted proteins (>3 g/L) [30]. Furthermore, the development of "customized" glycosylation pathways in yeasts like P. pastoris is a significant advancement, allowing for the humanization of protein glycosylation patterns, which is critical for many therapeutic biologics [30].

Quantitative Platform Comparison

Table 1: Key Characteristics of E. coli and Yeast Expression Platforms

| Feature | E. coli | Yeast (e.g., K. phaffii) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type | Prokaryote | Eukaryote |

| Growth Rate | Very High (doubling time ~20 min) | High (doubling time ~1-2 hrs) |

| Post-Translational Modification | Limited (no glycosylation) | Capable (glycosylation possible) |

| Protein Secretion | Generally limited; often forms inclusion bodies | Efficient secretion possible with appropriate signals |

| Typical Product Titer | Varies; high for some proteins [31] | >3 g/L for secreted proteins [30] |

| Cost & Scalability | Low-cost media, highly scalable | Low-cost media, highly scalable |

| Regulatory Status | Well-established for many products [30] | GRAS status; approved for human vaccines [32] [30] |

| Genetic Tools | Extensive and highly advanced [30] | Advanced, but clonal variation can require more screening [30] |

Table 2: Commercial and Industrial Market Context (2025)

| Platform | Market Context | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Strains | Market size estimated at USD 2.26 Bn in 2025 [33] | Recombinant protein production, biopharmaceutical development, industrial processes [33] |

| Yeast | Market size estimated at USD 4.19 Bn in 2025 [34] | Baker's yeast (38.7%), therapeutic proteins, vaccines, bioethanol [32] [34] |

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

Strain Engineering and Selection

A critical first step in metabolic engineering is the introduction of heterologous DNA into the host organism. For E. coli, this is typically achieved via plasmid-based expression cassettes (e.g., ColE1, p15A), which allow for rapid gene expression and high copy numbers [30]. In contrast, for yeasts like K. phaffii, expression constructs are usually integrated directly into the host chromosome via homologous recombination. While this creates mitotically stable strains, it can also lead to significant clonal variation in productivity, necessitating the screening of hundreds or even thousands of transformants to identify high-producing clones [30]. This process is greatly enhanced by automated high-throughput screening methods.

Promoter selection is another vital component. E. coli systems often use inducible promoters like the T7 lac promoter or constitutive promoters of varying strengths. In K. phaffii, the methanol-inducible AOX1 promoter is one of the strongest and most widely used, though constitutive promoters such as GAP are also common [32]. The genetic engineering toolkit has been expanded with advanced techniques like CRISPR-Cas9, which allows for precise and efficient genome editing in both E. coli and yeast, accelerating the construction of complex production strains [33].

Metabolic Engineering and Bioprocess Optimization

Overcoming metabolic limitations is key to achieving high yields. A prime example is the engineering of E. coli W for flavonoid glycosylation [31]. The success of this platform relied on several interconnected strategies:

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): The native E. coli W strain was subjected to ALE to enhance its ability to utilize sucrose as a carbon source, improving its growth and robustness [31].

- Metabolic Rerouting: Key genes in central carbon metabolism (xylA, zwf, pgi) were knocked out to redirect carbon flux away from biomass and toward the synthesis of uridine diphosphate glucose (UDPG), the essential precursor for glycosylation [31].

- Pathway Overexpression: Genes encoding enzymes for the glycosylation pathway, including a sucrose phosphorylase (for breaking down sucrose) and a glycosyltransferase (YjiC from Bacillus licheniformis), were overexpressed to drive the conversion of chrysin to chrysin-7-O-glucoside (C7O) [31].

The diagram below illustrates the overall workflow for developing such a platform.

Diagram 1: Strain and Bioprocess Development Workflow. This chart outlines the key stages in developing a high-performance production strain, from initial host selection to final scaled-up production, highlighting the iterative nature of metabolic engineering.

Following strain construction, bioprocess optimization is critical for scaling up production. This involves moving from shake flasks to controlled bioreactors. Key parameters to optimize include pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, and nutrient feeding strategies. For the engineered E. coli W platform, implementing a fed-batch process in a 3 L bioreactor was essential to achieve the reported high titer of 1844 mg/L C7O, as it allowed for careful control of substrate and toxin levels [31]. Similarly, fed-batch bioprocesses are used in yeast cultivations, such as for a recombinant vaccine against Entamoeba histolytica in K. phaffii, where optimization led to a 12-fold increase in production compared to shake flasks [32].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The experimental workflows described rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components of a metabolic engineer's toolkit.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids for gene cloning and expression. | Shuttle vectors for E. coli (e.g., ColE1 origin) or integrative plasmids for yeast (e.g., for K. phaffii) [32] [30]. |

| Inducible Promoters | DNA sequences that control gene expression in response to a signal. | AOX1 promoter in K. phaffii (induced by methanol) [32]; T7/lac promoter in E. coli (induced by IPTG). |

| Engineering Tools (CRISPR-Cas9) | Molecular scissors for precise genome editing. | Knocking out genes like pgi or zwf in E. coli to reroute metabolic flux [31] [33]. |

| Specialized Media Components | Nutrients and inducers for selective growth and protein production. | Using sucrose as a carbon source for engineered E. coli W [31] or methanol for induction in K. phaffii [32]. |

| Chromatography Resins | Matrices for purifying target proteins from cell lysates or culture supernatant. | Protein A chromatography for antibody purification; ion exchange and affinity chromatography for general protein purification [32]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of microbial production is continuously evolving, driven by technological advancements and market demands. Several key trends are shaping its future:

- Advanced Genetic Engineering: The application of CRISPR-Cas9 and synthetic biology tools is becoming standard, allowing for more precise and efficient strain modification. This facilitates the creation of E. coli and yeast strains with optimized genomes for higher protein yields and better post-translational modifications [33].

- Platform Specialization and Robustness: There is a growing focus on engineering non-model but inherently robust strains, such as E. coli W, which demonstrates enhanced tolerance to toxic compounds like flavonoids compared to the standard K-12 strain [31]. This highlights a move towards tailoring the host organism to the specific stresses of the production process.

- Glyco-engineering in Yeast: A significant innovation trend is the humanization of yeast glycosylation pathways. Companies are engineering yeast strains like P. pastoris to produce proteins with human-like N-glycans, making yeast a more viable and cost-effective alternative to mammalian cells for complex therapeutic proteins [30].

- AI and Automation Integration: The use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning is rising to manage the complexity of metabolic networks. AI can analyze large datasets to predict optimal gene edits and fermentation conditions. Furthermore, automated high-throughput screening is becoming indispensable for rapidly identifying top-performing yeast clones amidst significant clonal variation [35] [30].

- Sustainability Drivers: The push for environmentally friendly solutions is increasing interest in using microbial hosts for sustainable production of biofuels, bioplastics, and the conversion of waste streams, reinforcing the role of metabolic engineering in the circular bioeconomy [33].

E. coli and yeast platforms form the cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology. The choice between them hinges on the specific requirements of the target molecule, particularly the need for post-translational modifications, tolerance to process conditions, and overall production economics. E. coli remains the champion for rapid, high-yield production of proteins that do not require eukaryotic processing, while yeast offers a powerful eukaryotic alternative with superior secretion and evolving glycosylation capabilities. For beginners in metabolic engineering, mastering the genetic tools, metabolic strategies, and bioprocess principles associated with these two dominant platforms provides a strong foundation for contributing to the future of biomanufacturing. The ongoing integration of advanced gene editing, automation, and AI-driven design promises to further enhance the productivity and scope of these versatile microbial cell factories.

The field of metabolic engineering has undergone a fundamental transformation, evolving from a discipline focused on single-gene manipulations to one that embraces the complexity of entire biological systems. This evolution from genetic engineering to systems biology represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach the design and optimization of biological systems for industrial and therapeutic applications. Where early metabolic engineering relied on sequential trial-and-error modifications, the modern approach leverages computational modeling, multi-omics data integration, and machine learning to develop predictive understanding of cellular behavior. This comprehensive review examines the technological advances driving this evolution, detailing the experimental methodologies and computational frameworks that now enable researchers to bridge the gap between genetic modifications and system-level phenotypes.

The significance of this transition extends across multiple industries, from sustainable energy to pharmaceutical development. In biofuel production, for instance, the integration of systems biology has enabled the engineering of microbial chassis with significantly enhanced capabilities. Advanced biofuels derived from non-food lignocellulosic feedstock demonstrate how systems-level approaches can address both economic and sustainability challenges that limited earlier generations of biofuel technology [36]. Similarly, in pharmaceutical development, the ability to map intricate interaction networks between different layers of biological molecules has created new opportunities for investigating complex disease etiology and identifying therapeutic targets [37].

The Generational Evolution of Bioengineering Approaches

The progression from simple genetic manipulations to sophisticated systems-level engineering can be observed through the development of biofuel technologies, which serve as an exemplary case study of this evolution. Each generation represents not only technical advancement but also a fundamental shift in engineering philosophy.

Table 1: Generational Evolution of Bioengineering Approaches in Biofuel Production

| Generation | Feedstock | Engineering Approach | Key Technologies | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Food crops (corn, sugarcane) | Conventional fermentation | Transesterification, distillation | Food vs. fuel competition, high land use |

| Second | Non-food lignocellulosic biomass | Microbial strain engineering | Enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentation | Biomass recalcitrance, process complexity |

| Third | Microalgae | Photosynthetic efficiency optimization | Photobioreactors, hydrothermal liquefaction | Scale-up challenges, production costs |

| Fourth | Engineered microorganisms & synthetic systems | Synthetic biology, systems-level design | CRISPR-Cas, pathway engineering, AI-driven optimization | Regulatory hurdles, technical complexity |

First-generation biofuels primarily relied on conventional fermentation and distillation of food crops like corn and sugarcane, employing basic genetic engineering techniques to improve yield but facing significant limitations regarding food competition and land use [36]. Second-generation approaches transitioned to non-food lignocellulosic biomass, requiring more sophisticated microbial engineering to efficiently convert resistant plant materials into fermentable sugars. This generation saw the development of specialized enzymes such as cellulases, hemicellulases, and ligninases to break down recalcitrant biomass, alongside engineering of microbial hosts like S. cerevisiae for improved xylose utilization [36].

The third generation marked a shift toward photosynthetic microorganisms, particularly microalgae, with engineering efforts focused on enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and lipid accumulation. This approach resolved the food-versus-fuel dilemma but introduced new challenges in scaling and economic viability [36]. Contemporary fourth-generation biofuel production fully embraces systems biology, integrating synthetic biology tools with computational modeling to create engineered microbial systems capable of producing advanced drop-in fuels. These systems employ CRISPR-Cas for precise genome editing, de novo pathway engineering for compounds like butanol and isoprenoids, and AI-driven optimization to overcome previous yield limitations [36]. Notable achievements include 91% biodiesel conversion efficiency from microbial lipids and a threefold increase in butanol yield in engineered Clostridium species [36].

Fundamental Technological Transitions

From Single-Gene Editing to Programmable Genome Engineering

The development of increasingly sophisticated DNA manipulation tools has been instrumental in enabling the transition to systems biology. Early genetic engineering depended on homologous recombination and basic recombinase systems (Cre-lox, Flp-FRT) that required pre-engineered recognition sequences and offered limited programmability [38]. While valuable for specific applications, these technologies were poorly suited for systems-level engineering due to their low throughput and inability to perform complex multiplexed edits.

The advent of CRISPR-based systems has dramatically expanded engineering capabilities. Initial CRISPR-Cas9 systems enabled targeted double-strand breaks, allowing more precise gene edits but still relying on endogenous DNA repair mechanisms that often produced heterogeneous outcomes [38]. The development of homology-directed repair (HDR) strategies improved editing precision but remained constrained by cell cycle dependence and competition with error-prone non-homologous end joining pathways [38].

Recent advances have overcome these limitations through several innovative approaches:

CRISPR-Assisted Transposase (CAST) Systems: These technologies combine CRISPR targeting with transposase-mediated DNA insertion, enabling precise integration of large DNA fragments (up to 30 kb) without double-strand breaks [38]. Type I-F CAST systems achieve this through a Cascade complex (Cas6, Cas7, Cas8) for target recognition and a heteromeric transposase (TnsA, TnsB, TnsC) for DNA integration approximately 50 bp downstream of the target site [38]. Type V-K systems utilize the single-effector Cas12k with integration occurring 60-66 bp downstream of the PAM site [38].

Prime Editing: This more recent innovation uses catalytically impaired Cas enzymes fused to reverse transcriptase, enabling precise point mutations and small insertions without double-strand breaks [38].

Vibrio natriegens Toolkit (Vnat Collection): This comprehensive, modular genetic toolkit exemplifies modern engineering approaches, featuring optimized Golden Gate assembly with improved junction sequences that achieve up to 300-fold increased assembly efficiency, novel operon connectors for multi-gene pathway construction, and refined NT-CRISPR methods that eliminate intermediate purification steps [39].

Diagram 1: Evolution of genetic engineering technologies from traditional recombinase-based methods to modern DSB-free systems.

The Rise of Multi-Scale Modeling and Omics Integration

Where early metabolic engineering focused on individual pathways, systems biology approaches now integrate multiple layers of biological information through sophisticated computational frameworks. This integration occurs across two primary domains: Systems Biology (SB) and Process Systems Engineering (PSE), which are increasingly converging into the unified discipline of Biotechnology Systems Engineering (BSE) [40].

Systems Biology provides mathematical and computational methods for understanding biological phenomena across different omics levels, utilizing several key modeling approaches:

Constraint-Based Modeling: This approach treats metabolic fluxes as decision variables in biologically inspired optimization problems, addressing system underdetermination by considering biologically relevant objective functions (e.g., maximizing growth) subject to mass-balance and physiological constraints [40]. When solved under pseudo-steady-state assumptions, it provides metabolic flux distribution snapshots for given temporal states.

Kinetic Modeling: Unlike constraint-based approaches, kinetic modeling explicitly describes fluxes as time-dependent functions governed by enzyme kinetics and metabolite concentrations, capturing accumulation of both metabolic intermediates and extracellular species [40]. Though more biologically insightful, these models present numerical challenges for optimization and parameterization.

Process Systems Engineering focuses on mathematical modeling and computer-aided methods for design, optimization, and control at macroscopic scales, emphasizing bioreactor-level variables like feed rates, oxygen availability, temperature, and pH [40]. Control strategies range from conventional proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control to advanced model predictive control (MPC) and reinforcement learning (RL) [40].

The emerging Biotechnology Systems Engineering framework integrates these approaches, creating multi-scale models that link intracellular metabolism with bioreactor dynamics and overall biomanufacturing facility performance [40]. This integration enables adaptive learning, continuous model updating, and self-adaptive optimization through digital twins that combine mechanistic modeling with machine learning [40].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Types and Their Applications in Metabolic Engineering

| Omics Layer | Analytical Focus | Engineering Applications | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence and structure | Identification of metabolic potential, CRISPR target selection | Whole-genome sequencing, SNP arrays |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression levels | Analysis of regulatory mechanisms, promoter engineering | RNA-seq, microarrays |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance and modifications | Enzyme expression optimization, metabolic flux analysis | Mass spectrometry, protein arrays |

| Fluxomics | Metabolic reaction rates | Pathway flux quantification, bottleneck identification | 13C tracing, metabolic flux analysis |

| Metabolomics | Metabolite concentrations | Pathway dynamics, intermediate accumulation | GC/MS, LC/MS, NMR |

Experimental Frameworks and Methodologies

The Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycle for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

The DBTL cycle represents a systematic framework for metabolic engineering that embodies the integration of genetic engineering with systems biology principles. This iterative approach provides structure to the engineering process while incorporating computational tools at each stage [41].

Design Phase: Computational tools pathway design, enzyme selection, and pathway discovery using scientific programming environments like Scientific Python [41]. This phase leverages both evidence-based networks (constructed from experimentally validated interactions in databases) and statistically inferred networks (derived from multi-omics data correlation analyses) [37]. For plant natural products, this may involve identifying key enzymes and transcription factors in biosynthetic pathways for CRISPR targeting [42].