Metabolic Pathway Modulation: From Foundational Principles to Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of metabolic pathway modulation, a cornerstone of modern biomedical science for developing treatments for conditions like metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) and neurodegenerative diseases.

Metabolic Pathway Modulation: From Foundational Principles to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of metabolic pathway modulation, a cornerstone of modern biomedical science for developing treatments for conditions like metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) and neurodegenerative diseases. It begins by establishing the core principles of anabolic, catabolic, and regulatory pathways. The discussion then progresses to advanced methodological approaches, including proteomic analyses, machine learning, and metabolic engineering, highlighting their application in drug development. The content further addresses key challenges in pathway optimization and the critical role of validation through pre-clinical models and multi-omics integration. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current strategies and future directions for leveraging metabolic pathways as therapeutic targets.

Core Principles of Metabolic Pathways: Anabolism, Catabolism, and Signaling Networks

Metabolic pathways form the core of cellular biochemistry, representing a series of interlinked biochemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes that sustain life through energy management and molecular synthesis [1]. These pathways are indispensable for maintaining homeostasis within an organism, with the flux of metabolites through a pathway being rigorously regulated based on cellular demands and substrate availability [2]. For researchers investigating basic principles of metabolic pathway modulation, understanding these intricate networks provides the foundation for therapeutic interventions in diseases ranging from cancer to metabolic disorders. The coordinated action of metabolic pathways enables cells to extract energy from nutrients, synthesize building blocks for macromolecules, and eliminate waste products, thereby constituting the biochemical infrastructure of all living systems [3].

The architecture of metabolic pathways follows defined principles where reactants, products, and intermediates (collectively known as metabolites) are modified through sequential transformations [2]. Each step in these pathways is catalyzed by specific enzymes, with the product of one enzyme typically serving as the substrate for the next, creating tightly regulated metabolic chains that can be modulated at multiple points [2]. This systematic organization allows for efficient control of metabolic flux and provides natural points for therapeutic intervention through pharmacological modulation of key enzymatic steps.

Core Principles and Classification of Metabolic Pathways

Fundamental Categories of Metabolic Pathways

Metabolic pathways are universally categorized into three principal types based on their functional roles and energy dynamics within the cell. The classification encompasses catabolic, anabolic, and amphibolic pathways, each with distinct characteristics and regulatory mechanisms [2].

Catabolic pathways are primarily exergonic processes that release energy by breaking down complex organic molecules into simpler ones. These pathways are responsible for the oxidative degradation of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, resulting in the production of energy carriers such as ATP, NADH, FADH2, and NADPH [1] [2]. The end products of catabolism are typically small molecules like carbon dioxide, water, and ammonia. A quintessential example includes cellular respiration pathways (glycolysis, citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation) that systematically dismantle glucose to generate ATP through both substrate-level and oxidative phosphorylation [2].

Anabolic pathways represent endergonic processes that consume energy to synthesize complex biomolecules from simpler precursors. These biosynthetic pathways utilize the energy stored in ATP and the reducing power of NADPH, NADH, and FADH2 to construct macromolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, polysaccharides, and lipids [1] [2]. An example is gluconeogenesis, which reverses the glycolytic pathway to synthesize glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors through a pathway that incorporates four distinct enzymes (pyruvate carboxylase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, and glucose-6-phosphatase) to overcome thermodynamic barriers [2].

Amphibolic pathways possess the unique capacity to function both catabolically and anabolically depending on cellular energy requirements and precursor availability [2]. The citric acid cycle (TCA cycle) represents a prime example, operating primarily in a catabolic mode to oxidize acetyl-CoA for energy production while simultaneously supplying intermediates for biosynthetic processes such as amino acid and heme synthesis [2]. Another example is the glyoxylate cycle, an alternative to the TCA cycle that occurs in plants and bacteria, which bypasses decarboxylation steps to preserve carbon skeletons for biosynthesis when glucose is scarce [2].

Quantitative Parameters in Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

| Parameter | Definition | Research Significance | Measurement Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Flux | The rate of turnover of molecules through a metabolic pathway | Determines pathway activity; altered in disease states | 13C-labeling with NMR or GC-MS analysis [2] |

| Enzyme Kinetics | Rates of enzymatic reactions (Km, Vmax) | Identifies rate-limiting steps; predicts drug effects | Michaelis-Menten analysis with substrate variation |

| Energy Charge | Ratio of ATP to ADP + AMP | Indicates cellular energy status | HPLC-based nucleotide quantification |

| Mass Distribution | Labeling patterns in metabolites | Reveals pathway activity and contributions | Mass spectrometry with stable isotope tracing [2] |

Current Research Methodologies in Pathway Modulation

Integrating Metabolome-Genome Wide Association Studies (MGWAS) with Pathway Simulations

Recent advancements in metabolic pathway research have established MGWAS as a powerful approach for identifying genetic variants that influence metabolite levels in biological samples [4]. This methodology integrates high-throughput metabolomic profiling with genome-wide association analysis to reveal how single nucleotide variations throughout the genome influence metabolic traits. However, MGWAS faces inherent limitations, including statistical correlations that may not reflect biological causality, false positives due to chance associations, and potential false negatives from limited sample sizes missing rare genetic variants [4].

To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed sophisticated metabolic pathway model simulations that systematically investigate variant-metabolite combinations [4]. These in silico experiments employ differential equation-based models of metabolic pathways with initial metabolite concentrations and enzyme reaction rates derived from experimental data. By adjusting enzyme reaction rates to simulate genetic variations, these models can predict resulting changes in metabolite concentrations, thereby validating MGWAS findings and identifying biologically relevant associations that may not reach statistical significance in conventional association studies due to sample size limitations [4].

A recent implementation of this approach utilized the human liver cell folate cycle model, which comprises cytosolic and mitochondrial compartments [4]. The model maintained constant total concentrations of folate derivatives while simulating the effects of altered enzyme activities. This simulation strategy successfully replicated most variant-metabolite pairs identified by MGWAS with significant p-values, while additionally revealing marked metabolite fluctuations undetected by conventional MGWAS, demonstrating enhanced sensitivity for identifying metabolic perturbations [4].

Mendelian Randomization for Establishing Causal Relationships

Mendelian randomization has emerged as a pivotal methodology for elucidating causal relationships between metabolites and disease states, particularly in complex conditions like pulmonary hypertension (PH) and cancer [5]. This approach uses genetic variants as instrumental variables to test for causal effects between modifiable risk factors and diseases, thereby overcoming limitations of observational studies susceptible to confounding and reverse causation.

In a comprehensive analysis of 289,365 individuals, researchers applied Mendelian randomization to examine the causal roles of 1,400 metabolites in PH pathogenesis [5]. The study identified 57 metabolites associated with PH risk and investigated key tumor-related pathways through promoter methylation analysis. This integrated approach revealed how metabolic alterations influence disease processes through genomic changes and post-translational modifications, providing a framework for understanding the shared mechanisms between PH and cancer [5].

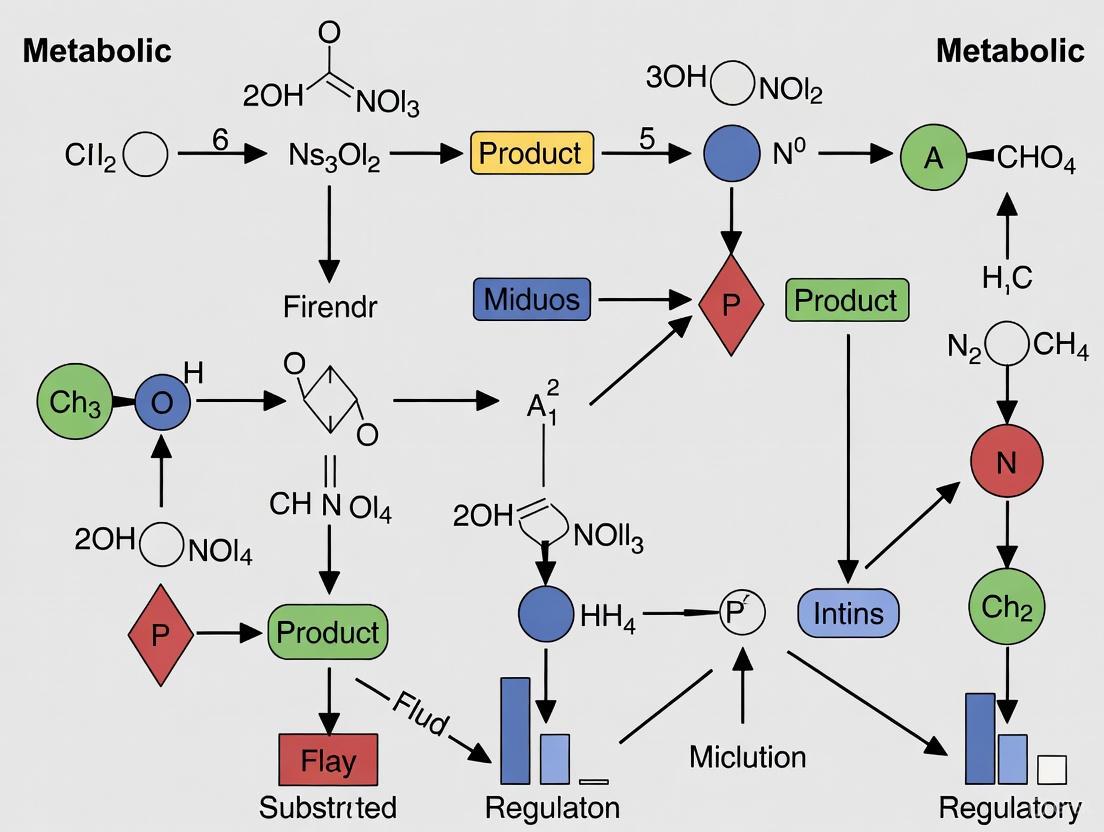

Diagram 1: Integrated MGWAS and Simulation Workflow for Metabolic Pathway Research. This workflow illustrates the complementary approach of combining statistical genetics with computational modeling to validate metabolic associations and identify therapeutic targets.

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Pathway Investigation

Protocol: Metabolome-Genome Wide Association Study (MGWAS)

Objective: To identify genetic variants associated with metabolite concentration changes in human plasma samples.

Materials and Reagents:

- Plasma samples from cohort study participants

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectrometer (e.g., Bruker 600 MHz)

- Targeted MS platform (e.g., Xevo TQ-XS MS/MS with MxP Quant 500 Kit)

- Genotyping arrays or whole-genome sequencing resources

- Metabolite quantification software (e.g., Chenomx NMR Suite, MetIDQ Oxygen)

Methodology:

- Participant Selection: Apply inclusion criteria including non-pregnant status, proper sample storage, available genotype data, and passed quality controls for ancestry and relatedness [4].

- Metabolite Measurement: Perform metabolite extraction followed by NMR spectroscopy at standard temperature (298 K). Acquire standard NOESY and CPMG spectra for each sample. Process data using automated quantification software [4].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Conduct targeted MS using appropriate kits following manufacturer guidelines. Adjust LC and FIA parameters accordingly. Standardize concentrations using dedicated software [4].

- Genotype Processing: Filter genotyped and imputed single-nucleotide variations based on minor allele frequency (<0.01), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p<0.00001), missing genotype rate (>0.05), and INFO scores (<0.9) [4].

- Association Analysis: Perform MGWAS using linear mixed models (e.g., BOLT-LMM) for NMR-measured metabolites and linear regression (e.g., GCTA) for MS-measured metabolites. Log-transform all metabolite concentrations and remove outliers (p<0.001 by Grubbs test) [4].

- Covariate Adjustment: Calculate residuals for log-transformed plasma metabolite concentrations using linear regression with covariates including age, BMI, sex, sample storage duration, and genetic principal components [4].

Protocol: Metabolic Pathway Simulation for Variant Interpretation

Objective: To simulate the effects of genetic variants on metabolite concentrations using computational models.

Materials and Software:

- Established metabolic pathway model (e.g., BioModels database)

- Differential equation solving environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python with SciPy)

- Experimentally derived initial metabolite concentrations

- Enzyme kinetic parameters from literature

Methodology:

- Model Acquisition: Obtain a curated metabolic pathway model from repositories such as BioModels [4]. The human liver cell folate cycle model represents an appropriate starting point, comprising cytosolic and mitochondrial compartments.

- Parameter Initialization: Set initial metabolite concentrations and enzyme reaction rates based on experimental data to replicate normal in vivo conditions [4].

- Compartmentalization: Treat metabolites and enzymes in different cellular compartments as distinct entities while allowing free diffusion for specific molecules across boundaries [4].

- Constraint Application: Maintain constant total concentrations of related metabolite classes (e.g., folate derivatives) while allowing individual species concentrations to fluctuate.

- Variant Simulation: Systematically adjust enzyme reaction rates to simulate the effects of genetic variants, mimicking altered enzyme activity or expression.

- Concentration Monitoring: Observe changes in metabolite concentrations following simulated perturbations, running simulations until steady-state conditions are reached.

- Validation: Compare simulation results with MGWAS findings, identifying concordant and discordant variant-metabolite pairs for further investigation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Pathway Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Metabolic Pathway Investigation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bruker 600 MHz NMR Spectrometer | Quantitative metabolite profiling | Measurement of formate, serine, glycine, methionine, dimethylglycine in plasma [4] |

| Xevo TQ-XS MS/MS with MxP Quant 500 Kit | Targeted metabolomics | Quantification of homocysteine, sarcosine, and other specific metabolites [4] |

| BioModels Database | Repository of computational models | Acquisition of curated metabolic pathway models (e.g., folate cycle) [4] |

| Pathway Commons Database | Integration of pathway information | Researching existing pathway content and interactions [6] |

| CHEBI Database | Chemical entity annotation | Standardized identifiers for metabolic compounds [6] |

| UniProt Database | Protein sequence and function annotation | Precise identifiers for enzymes in pathway models [6] |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (13C-glucose) | Metabolic flux analysis | Tracing carbon fate through pathways like glycolysis and TCA cycle [2] [7] |

Visualization and Modeling of Metabolic Pathways

Standardized Representation for Enhanced Reproducibility

Effective visualization and modeling are crucial for creating reusable, computationally accessible pathway models that advance metabolic research. The implementation of standardized representations enables both intuitive human comprehension and computational analysis [6]. Several established formats support these dual objectives, including Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN) for visual representation, Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) for model encoding, Biological Pathway Exchange (BioPAX) for pathway integration, and Graphical Pathway Markup Language (GPML) for pathway editing and storage [6].

When constructing pathway models, researchers should adhere to key principles to maximize utility and reproducibility. First, whenever possible, reuse and extend existing models from established databases such as Reactome, WikiPathways, BioCyc, KEGG, and Pathway Commons [6]. Second, determine the appropriate scope and level of detail based on the biological process being illustrated, considering which reactions and entities are crucial for understanding the process [6]. Third, employ standardized naming conventions and identifiers for molecular entities using resources like HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) for genes, UniProt for proteins, and ChEBI for chemical compounds to ensure computational interoperability [6].

Diagram 2: Central Carbon Metabolic Pathway with Key Regulation Points. This simplified representation highlights critical junctions in carbohydrate metabolism where flux is regulated, including the irreversible steps catalyzed by hexokinase, phosphofructokinase (PFK), and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), as well as the branch point at pyruvate that determines aerobic versus anaerobic fate.

The investigation of metabolic pathways as series of interlinked biochemical reactions has evolved from descriptive biochemistry to predictive, quantitative science through integrated computational and experimental approaches. The convergence of MGWAS with pathway simulation models represents a paradigm shift in how researchers identify and validate metabolic perturbations in disease states [4]. Furthermore, the application of Mendelian randomization to establish causal relationships between metabolites and complex diseases provides a powerful framework for identifying authentic therapeutic targets rather than mere associations [5].

Future advancements in metabolic pathway modulation research will likely focus on several key areas. First, the development of more sophisticated multi-compartment models that accurately represent subcellular localization and metabolite channeling will enhance predictive capabilities. Second, the integration of single-cell metabolomics with spatial transcriptomics will enable researchers to understand metabolic heterogeneity within tissues and tumors. Third, the application of machine learning approaches to predict metabolic flux distributions from static metabolomic measurements will accelerate the translation of observational data into functional insights. As these technologies mature, they will undoubtedly uncover novel regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities for modulating metabolic pathways in human health and disease.

Metabolism encompasses the vast network of chemical reactions that sustain life within living organisms. These reactions are organized into coordinated sequences known as metabolic pathways, where the product of one reaction serves as the substrate for the next [8]. For researchers investigating metabolic modulation, understanding the fundamental dichotomy between anabolic and catabolic pathways is paramount. These two opposing processes operate in a tightly regulated balance to maintain cellular homeostasis, control energy utilization, and determine metabolic fate at both cellular and organismal levels [8] [9].

Anabolic pathways are biosynthetic in nature, constructing complex cellular components from simpler precursor molecules through processes that require energy input [8] [10]. Conversely, catabolic pathways function as the degradative arm of metabolism, breaking down complex organic molecules into simpler ones while releasing energy that the cell can capture and utilize [11]. The precise regulation between these counteracting processes determines whether an organism is in a state of growth, maintenance, or degradation—a balance that becomes disrupted in numerous disease states including metabolic disorders, cancer, and neurodegenerative conditions [12] [9].

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of anabolic and catabolic pathways, focusing on their distinct roles in molecular synthesis and energy release, their regulatory mechanisms, and the experimental approaches used to investigate them within the context of metabolic pathway modulation research.

Fundamental Principles of Anabolic and Catabolic Pathways

Defining Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

Anabolic pathways are characterized by their energy-dependent biosynthesis of complex molecules from simpler precursors. These constructive processes are essential for cellular growth, maintenance, and differentiation [10]. Key anabolic functions include the synthesis of proteins from amino acids, polysaccharides from simple sugars, and nucleic acids from nucleotides [8]. Anabolic processes consume rather than produce energy, primarily utilizing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as their energy currency [13].

Catabolic pathways involve the systematic breakdown of complex organic molecules into simpler ones, typically releasing energy that is captured by the cell [11]. These destructive processes liberate chemical energy stored in molecular bonds through pathways such as glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation [8]. Catabolism serves multiple essential functions: it generates ATP for cellular work, produces precursor metabolites for biosynthesis, and enables the oxidation of fuel molecules [11].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Anabolic versus Catabolic Pathways

| Parameter | Anabolic Pathways | Catabolic Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Dynamics | Consume energy (endergonic) | Release energy (exergonic) |

| ATP Relationship | Utilize ATP | Produce ATP |

| Molecular Outcomes | Build complex molecules from simple precursors | Break down complex molecules into simple units |

| Redox Cofactors | Utilize NADPH as reducing power | Generate NADH and FADHâ‚‚ as energy carriers |

| Primary Functions | Growth, repair, biosynthesis, storage | Energy production, macromolecule degradation |

| Representative Examples | Protein synthesis, gluconeogenesis, glycogenesis | Glycolysis, β-oxidation, proteolysis |

| Hormonal Regulators | Insulin, growth hormone, testosterone | Cortisol, glucagon, adrenaline, cytokines [14] [11] |

Energy Transfer and Metabolic Interdependence

The interplay between anabolic and catabolic pathways centers on ATP as the universal energy currency. Catabolic processes generate ATP through the breakdown of fuel molecules, while anabolic processes consume ATP to drive biosynthetic reactions [13]. This continuous cycle of ATP production and utilization forms the core of cellular energy metabolism [8].

Beyond ATP, metabolic pathways utilize specialized redox cofactors optimized for their respective functions. Catabolism primarily generates NADH, which is efficiently oxidized in the electron transport chain to produce ATP. Anabolism, conversely, preferentially utilizes NADPH as a electron donor for reductive biosynthesis, reflecting the distinct biochemical demands of these opposing processes [10].

This metabolic interdependence ensures that energy released from catabolic pathways is immediately available to power anabolic processes, creating a continuous energy transfer system that maintains cellular function [13]. The balance between these pathways is dynamically regulated in response to cellular energy status, nutrient availability, and hormonal signaling [14].

Regulation of Metabolic Pathways

Hormonal Control Mechanisms

The balance between anabolism and catabolism is precisely regulated through hormonal signaling. Key anabolic hormones include insulin, growth hormone, and testosterone, which promote biosynthetic processes and cellular growth [14]. These hormones activate intracellular signaling cascades that enhance nutrient uptake, protein synthesis, and energy storage.

Catabolic hormones include cortisol, glucagon, and adrenaline (epinephrine), which are often activated during stress or fasting states [14] [11]. These hormones promote the breakdown of energy stores: glucagon stimulates glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis in response to low blood glucose [11]; cortisol enhances proteolysis and lipolysis during prolonged stress [11]; and adrenaline prepares the body for immediate action by increasing heart rate, bronchodilation, and energy mobilization [11].

Table 2: Key Hormonal Regulators of Anabolic and Catabolic Pathways

| Hormone | Primary Origin | Metabolic Role | Pathway Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | Pancreatic β-cells | Promotes glucose uptake and storage | Strong anabolic: stimulates glycogenesis, lipogenesis, protein synthesis |

| Glucagon | Pancreatic α-cells | Increases blood glucose levels | Catabolic: stimulates glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis |

| Cortisol | Adrenal cortex | Stress response; increases blood glucose | Catabolic: promotes proteolysis, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis |

| Adrenaline | Adrenal medulla | Fight-or-flight response | Catabolic: stimulates glycogenolysis, lipolysis, gluconeogenesis |

| Growth Hormone | Anterior pituitary | Promotes tissue growth and repair | Anabolic: stimulates protein synthesis, lipolysis (to provide energy for growth) |

Molecular Regulation and Key Signaling Nodes

At the molecular level, metabolic pathways are regulated through allosteric control, substrate availability, and enzyme concentration. A critical regulatory node is the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling axis [12]. AMPK functions as a cellular energy sensor that is activated under low-energy conditions (high AMP:ATP ratio), promoting catabolic pathways to generate ATP while inhibiting anabolic processes to conserve energy [12].

Conversely, mTOR is activated when nutrients and energy are abundant, stimulating anabolic processes including protein synthesis, lipid biogenesis, and inhibiting autophagy [12]. The AMPK-mTOR axis represents a fundamental switch that determines metabolic direction in response to cellular energy status and nutrient availability.

Figure 1: AMPK-mTOR Regulatory Axis. This core signaling network functions as a metabolic switch, with AMPK activated during energy deficit to promote catabolism and inhibit mTOR-driven anabolism.

Recent research has elucidated additional regulatory components including sirtuins, NAD+-dependent deacetylases that connect cellular energy status to transcriptional outputs, and hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) that redirect metabolic flux under low oxygen conditions [12]. Understanding these regulatory networks is essential for developing targeted therapies for metabolic disorders.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Metabolic Pathways

Methodologies for Pathway Analysis

Investigating anabolic and catabolic pathways requires a multidisciplinary approach combining biochemical, molecular, and omics technologies. Key methodologies include:

Tracer Studies with Stable Isotopes: Utilizing ¹³C-glucose, ¹âµN-amino acids, or ²H-water to track metabolic flux through specific pathways. Cells or animals are exposed to labeled substrates, and the incorporation of labels into metabolic products is quantified using mass spectrometry to determine pathway utilization and rates [15].

Proteomic and Transcriptomic Profiling: Large-scale analysis of protein and gene expression changes under different metabolic conditions. Aptamer-based proteomic approaches (e.g., SomaScan) can quantify hundreds to thousands of proteins simultaneously in serum or tissue samples, identifying pathway-specific biomarkers [15].

Metabolomic Analysis: Comprehensive profiling of small molecule metabolites using LC-MS/MS or GC-MS to provide a snapshot of metabolic state. This approach can identify pathway intermediates that accumulate or diminish under experimental conditions, revealing nodes of regulation [15].

Histological and Imaging Techniques: Traditional histological staining (e.g., Picrosirius Red for collagen, Oil Red O for lipids) combined with advanced methods like immunofluorescence microscopy for spatial localization of metabolic enzymes and pathway markers in tissues [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Pathway Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Activators/Inhibitors | AICAR (AMPK activator), Rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor), Compound C (AMPK inhibitor) | Pharmacological modulation of specific pathway nodes to establish causal relationships |

| Antibodies for Western Blot/IF | Anti-LC3 (autophagy), Anti-pAMPK/AMPK, Anti-pmTOR/mTOR, Anti-β-hydroxybutyrate | Detection of pathway activation states and subcellular localization of key regulators |

| Protein Analysis Reagents | SomaScan aptamer-based proteomic panel, ELISA kits for specific metabolic hormones | Multiplexed protein quantification for pathway activity assessment; verification of specific protein changes |

| Metabolic Tracers | ¹³C-glucose, ¹âµN-amino acids, ²H-water, ¹³C-palmitate | Flux analysis to quantify carbon/nitrogen routing through specific metabolic pathways |

| Gene Expression Tools | qPCR primers for metabolic genes (SREBP1c, FASN, PGC1α), RNA-seq services | Transcriptional regulation analysis of metabolic pathways |

| Histological Stains | Picrosirius Red (collagen), Oil Red O (lipids), Immunofluorescence antibodies | Tissue-level assessment of metabolic pathway outputs and fibrosis/steatosis evaluation |

Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Pathway Modulation Studies

A typical comprehensive workflow for investigating metabolic pathway modulation integrates multiple methodological approaches:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Metabolic Studies. Comprehensive pathway analysis requires integrated approaches from model selection through multi-omics profiling to functional validation.

Recent Advances and Clinical Implications

Therapeutic Modulation of Metabolic Pathways

Emerging research has identified several promising approaches for modulating anabolic-catabolic balance in disease contexts. Intermittent fasting regimens have been shown to robustly activate autophagy through the AMPK-mTOR axis, enhancing cellular resilience and metabolic homeostasis [12]. Preclinical and clinical studies demonstrate that fasting increases AMPK phosphorylation while inhibiting mTOR activity, leading to enhanced expression of autophagy markers including LC3-II, Beclin-1, and ATG proteins [12].

Pharmacological approaches are also showing promise. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) such as semaglutide have demonstrated significant effects on metabolic pathways in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) [15]. Recent studies show that semaglutide improves histological markers of fibrosis and inflammation while reducing hepatic expression of fibrosis-related and inflammation-related gene pathways [15]. Proteomic analyses identified 72 proteins significantly associated with MASH resolution following semaglutide treatment, most related to metabolism with several implicated in fibrosis and inflammation [15].

Quantitative Assessment of Pathway Modulation

Table 4: Quantitative Effects of Metabolic Interventions in Preclinical and Clinical Studies

| Intervention | Experimental Model | Key Effects on Pathways | Quantitative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent Fasting | Preclinical models and human studies | AMPK activation, mTOR inhibition, autophagy induction | Increased AMPK phosphorylation; 2-3 fold increase in LC3-II/Beclin-1; improved insulin sensitivity [12] |

| Semaglutide (GLP-1 RA) | Phase 2 trial in MASH patients (n=320) | Improved hepatic steatosis, inflammation, ballooning, fibrosis | MASH resolution: 59% vs 17% placebo; steatosis improvement: 55% vs 9% placebo; weight loss: 13% vs 1% placebo [15] |

| Semaglutide | DIO-MASH and CDA-HFD mouse models | Reduced fibrosis and inflammation markers | Significant reduction in Picrosirius Red staining and collagen expression; sustained downregulation of fibrosis-related genes [15] |

The precise balance between anabolic and catabolic pathways represents a fundamental principle in metabolic regulation with profound implications for human health and disease. Anabolic pathways drive the synthesis of complex molecules essential for growth and maintenance, while catabolic pathways break down molecules to release energy and provide metabolic intermediates. The AMPK-mTOR signaling axis serves as a central regulatory node that senses cellular energy status and directs metabolic flux appropriately.

Advanced research methodologies including stable isotope tracing, multi-omics approaches, and integrated experimental workflows are providing unprecedented insights into metabolic pathway regulation. These approaches are revealing novel therapeutic opportunities for modulating metabolic pathways in conditions ranging from metabolic liver diseases to neurodegenerative disorders. Continuing research in this field promises to yield new mechanistic insights and therapeutic strategies for optimizing metabolic health through precise modulation of anabolic and catabolic processes.

Transcriptional control represents a fundamental biological process where cells regulate the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA in response to internal and external signals. This process is predominantly governed by the precise interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and specific DNA sequences, which subsequently modulate gene expression patterns that define cellular identity, function, and adaptive responses. Within the broader context of metabolic pathway modulation research, understanding these regulatory mechanisms provides the foundational knowledge required for therapeutic intervention in complex diseases, ranging from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) to neurodegenerative disorders and cancer [15] [16].

Signal transduction pathways serve as the critical communication link that converts extracellular stimuli into intracellular responses, ultimately fine-tuning transcriptional programs. These pathways regulate gene expression by modulating the activity of nuclear transcription factors, with well-characterized examples including the AP-1 and CREB/ATF proteins that serve as paradigms explaining the transfer of regulatory information from the cell surface to the nucleus [17]. Recent advances have revealed that transcriptional regulation operates within vast and complex regulatory landscapes encompassing promoters, enhancers, and other regulatory elements that work in concert to determine the timing, magnitude, and specificity of gene expression [18].

Core Principles of Transcriptional Regulation

Transcription Factor-DNA Recognition Dynamics

The precise molecular mechanisms underlying transcription factor binding to DNA represent a cornerstone of transcriptional control. Groundbreaking research has demonstrated that transcription factors recognize and bind to specific DNA sequences with remarkable specificity, a process crucial for determining cell fate and function. A recent comprehensive study investigating the transcription factor KLF1, essential for red blood cell development, revealed that these proteins recognize substantially more of the DNA sequence surrounding their binding sites than previously understood [19].

The binding affinity between transcription factors and DNA follows thermodynamic principles that govern these interactions in both simplified in vitro systems and complex cellular environments. Researchers have developed sophisticated experimental methods, including high-throughput measurements that simultaneously quantify transcription factor binding to numerous DNA sequences. These approaches involve imaging DNA sequencing chips with different DNA sequences attached to glass surfaces, combined with fluorescently labeled transcription factors to precisely quantify binding interactions [19]. The consistency observed between in vitro binding measurements and in vivo behavior confirms that fundamental biophysical principles dictate transcription factor-DNA recognition, providing a framework for understanding how mutations in these binding sites contribute to human diseases [19].

Complex Regulatory Architectures

Beyond individual protein-DNA interactions, transcriptional regulation operates within complex architectural frameworks. The human genome contains thousands of putative regulatory elements, including promoters that function as ON/OFF switches and enhancers that provide fine-tuning and cell-type specificity [18]. This regulatory complexity is characterized by:

- Multiple Enhancer-Gene Interactions: Individual genes often interact with up to tens of different enhancers, while enhancer elements frequently engage with more than one target gene [18].

- Combinatorial Control: Most cellular pathways are controlled by larger sets of transcription factors that function with additive effects, where the number rather than the specific type of factors bound often determines expression levels [18].

- Temporal Dynamics: Regulatory elements exhibiting temporal kinetics frequently associate with genes showing similar transcriptional patterns, enabling precise response coordination to cellular signals [18].

Research in innate immune cells has revealed that regulatory complexity (defined as the number of regulatory elements associated with a gene) correlates with crucial gene characteristics: low expression variance across evolution, activation of key cell fate decision genes, and rapid, high activation in signal transduction pathways [18].

Signal Transduction Pathways and Transcriptional Control

Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway represents an evolutionarily conserved signal transduction cascade with critical regulatory roles in cellular proliferation, cell fate determination, and tissue homeostasis. This pathway functions through a carefully orchestrated series of molecular interactions:

- OFF-State: In the absence of Wnt ligands, cytoplasmic β-catenin is constitutively targeted for degradation by a multiprotein destruction complex containing AXIN, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), casein kinase 1α (CK1α), and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β). β-Catenin undergoes sequential phosphorylation, leading to polyubiquitination by β-TrCP and subsequent proteasomal degradation [20].

- ON-State: Wnt ligand engagement with Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors triggers disassembly of the destruction complex in a Dishevelled (DVL)-dependent manner, resulting in β-catenin stabilization and accumulation [20].

- Nuclear Function: Stabilized β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a complex with T-cell Factor (TCF)/Lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) transcription factors to activate target genes including MYC, BIRC5, and CCND1, which regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, self-renewal, and survival [20].

Table 1: Key Components of the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

| Component | Function | Role in Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Wnt Ligands | Extracellular signaling molecules | Initiate pathway activation by binding receptors |

| Frizzled & LRP5/6 | Transmembrane receptors | Receive extracellular Wnt signals |

| β-Catenin | Central pathway mediator | Transduces signal to nucleus; transcriptional co-activator |

| Destruction Complex | Multi-protein complex (AXIN, APC, CK1α, GSK3β) | Regulates β-catenin stability in absence of Wnt signaling |

| TCF/LEF | Transcription factors | DNA-binding partners for β-catenin in nucleus |

Recent research has revealed that β-catenin exhibits functionality beyond its canonical roles, including participation in post-transcriptional processes. β-Catenin has been shown to associate with splicing regulatory RNA-binding proteins and can directly bind RNA, modulating alternative splicing of genes including the adenovirus E1A minigene and oestrogen receptor-β [20]. These findings significantly expand the potential regulatory scope of this central signaling pathway.

Metabolic Signaling and Transcriptional Regulation

Metabolic pathways are intricately connected to transcriptional regulation, creating feedback loops that maintain cellular homeostasis. Recent research on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) has illuminated how pharmacological interventions can modulate these interconnected networks. Semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, demonstrates how targeted therapies can simultaneously influence metabolic, inflammatory, and fibrotic pathways through both direct and indirect mechanisms [15] [21].

Aptamer-based proteomic analyses of serum samples from patients with MASH identified 72 proteins significantly associated with MASH resolution following semaglutide treatment. Most of these proteins were related to metabolism, with several specifically implicated in fibrosis and inflammation pathways. This proteomic signature reverted toward patterns observed in healthy individuals, suggesting a global normalization of pathway regulation [15] [21].

Table 2: Semaglutide-Mediated Pathway Modulation in MASH

| Pathway Category | Key Proteins Modulated | Biological Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Steatosis | PTGR1, GUSB | Reduced hepatic fat accumulation |

| Inflammation | ACY1, TXNRD1, FCGR3B, ADIPOQ, RPN1 | Decreased lobular inflammation |

| Ballooning | PTGR1, AKR1B10, ADAMTSL2 | Improved hepatocyte health |

| Fibrosis | ADAMTSL2, NFASC, COLEC11, FCRL3 | Reduced fibrotic progression |

Mediation analysis revealed that weight loss directly mediated a substantial proportion of MASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis (69.3% of total effect), as well as improvements in steatosis (82.8%) and hepatocyte ballooning (71.6%). Conversely, improvement in histologically assessed fibrosis was mediated through weight loss to a lesser extent (25.1%), indicating that factors beyond weight loss contribute to the antifibrotic effects observed [15].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Advanced Techniques for Studying Transcription Factor Binding

Cutting-edge methodologies have revolutionized our ability to quantify protein-DNA interactions with unprecedented precision:

- High-Throughput SELEX: Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment approaches enable comprehensive profiling of transcription factor binding specificities across thousands of DNA sequences simultaneously [20] [19].

- DNA Sequencing Chip Imaging: Different DNA sequences are attached to glass surfaces, and fluorescently labeled transcription factors are flowed in to bind, allowing precise quantification of binding affinities [19].

- In Vivo Methylation Mapping: DNA sequencing-based methods label DNA with methyl groups except at locations where transcription factors bind, physically blocking methylation and revealing binding sites in cellular contexts [19].

These approaches have demonstrated that thermodynamic principles link in vitro transcription factor affinities to single-molecule chromatin states in cells, bridging simplified biochemical systems with complex biological environments [19].

Synthetic Biology Approaches for Pathway Engineering

Synthetic biology has developed powerful tools for interrogating and engineering transcriptional regulatory networks:

- CRISPRi-Aided Genetic Switches: Recent advances have integrated transcription factor-based biosensors with Type V-A FnCas12a CRISPR systems to create precise, signal-responsive genetic switches. This platform exploits the RNase activity of FndCas12a to process CRISPR RNAs directly from biosensor-responsive mRNA transcripts, enabling sophisticated control of gene expression [22].

- Modular Genetic Parts: Standardized biological components including promoters, ribosome binding sites, and RNA regulatory elements enable predictable engineering of transcriptional networks. Libraries of variable-strength parts facilitate fine-tuning of pathway components [23] [24].

- Transcriptional Terminator Filters: Incorporation of these elements minimizes basal transcription, reduces leaky expression, and increases the dynamic range of target gene regulation in synthetic circuits [22].

These synthetic biology tools allow researchers to dissect complex regulatory relationships and implement engineered control systems for metabolic pathway optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptional Control Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Systems | FndCas12a (nuclease-deficient D917A mutant) | RNA-guided DNA binding for transcriptional regulation; enables complex circuit engineering through inherent RNase activity [22] |

| Plasmid Systems | pFnSECRVi, pG-FncrRNA | Modular vectors for genetic circuit construction; enable ligand-inducible expression and signal-responsive regulation [22] |

| Reporter Genes | GFP, mCherry/RFP | Quantitative assessment of promoter activity and gene expression dynamics; enable real-time monitoring of transcriptional responses [22] |

| Inducible Promoters | PTRC, PBAD, Tetracycline-responsive | Controlled gene expression enabling precise temporal regulation; essential for dynamic pathway modulation studies [22] |

| Aptamer-Based Proteomics | SomaScan SomaSignal Tests | Multiplexed protein quantification for pathway analysis; validated against liver histology to grade steatosis, inflammation, ballooning, and fibrosis [15] |

| Animal Disease Models | DIO-MASH mice, CDA-HFD mice | Preclinical evaluation of therapeutic interventions; model human metabolic diseases with different etiologies for pathway validation [15] |

| Xylose-3-13C | Xylose-3-13C|13C Labeled Isotope|RUO | Xylose-3-13C is a 13C-labeled monosaccharide for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

| Yllemlwrl | Yllemlwrl (LMP1 125-133) Peptide | Research-grade Yllemlwrl peptide, an EBV LMP1 epitope restricted by HLA-A*02:01. For research use only (RUO). Not for human or diagnostic use. |

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

The intricate interplay between transcriptional control and signal transduction pathways represents a fundamental regulatory layer in cellular physiology and metabolic homeostasis. Advances in our understanding of transcription factor binding dynamics, coupled with emerging evidence of multi-functional proteins like β-catenin that operate across transcriptional and post-transcriptional domains, continue to reveal unexpected complexity in these regulatory networks [20] [19].

The development of increasingly sophisticated experimental and engineering approaches, including CRISPRi-aided genetic switches and high-throughput binding measurements, provides researchers with powerful tools to dissect these complex systems [22] [19]. When applied within the framework of metabolic pathway modulation, these approaches hold significant promise for developing targeted therapeutic interventions for complex diseases including MASH, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer [15] [16].

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating multi-omics datasets to build predictive models of transcriptional responses, developing more precise synthetic biology tools for pathway engineering, and translating fundamental insights into novel therapeutic strategies that modulate transcriptional programs in disease contexts. The continued elucidation of these fundamental regulatory principles will undoubtedly expand our ability to therapeutically manipulate metabolic and signaling pathways for human health.

The Role of Enzymes as Catalytic Drivers in Metabolic Networks

Enzymes serve as the fundamental catalytic workhorses within cellular systems, driving the complex network of metabolic reactions essential for life. Their function extends beyond simple catalysis to include intricate roles in metabolic regulation, pathway modulation, and cellular adaptation. In the context of metabolic pathway modulation research, understanding enzyme kinetics, structural evolution, and network-level regulatory principles provides critical insights for applications in drug development, bioengineering, and systems biology. This whitepaper examines enzymes as catalytic drivers through multiple analytical lenses: structural conservation across evolution, network-scale regulatory interactions, mechanistic determination through computational approaches, and kinetic characterization methodologies. The integration of these perspectives reveals the hierarchical organization of metabolic systems and offers powerful approaches for therapeutic intervention and bioindustrial innovation.

Structural Evolution and Conservation in Metabolic Enzymes

Deep Learning-Enabled Structural Analysis

Advances in deep learning, particularly AlphaFold2, have enabled large-scale prediction and analysis of enzyme structures across species, opening new avenues for investigating the relationship between protein structure and metabolic function [25]. A recent evolutionary analysis of 11,269 predicted and experimentally determined enzyme structures across the Saccharomycotina subphylum (representing 400 million years of evolution) revealed that metabolism shapes structural evolution across multiple scales [25]. The study linked 424 orthologue groups (orthogroups) associated with 361 metabolic reactions in 224 metabolic pathways, demonstrating that enzyme evolution is constrained by reaction mechanisms, interactions with metal ions and inhibitors, metabolic flux variability, and biosynthetic cost [25].

Quantitative Metrics for Structural Analysis

Researchers employed two key metrics to quantify structural evolution: Mapping Ratios (MR) and Conservation Ratios (CR). The MR quantifies the percentage of amino acids that are 1:1 mappable to a reference enzyme structure (median MR = 87.4%), while the CR quantifies the percentage of mapped residues identical to the reference structure (median CR = 62.9%) [25]. These metrics revealed that secondary structural elements showed high mapping (mean MR = 95.4%) compared to regions without secondary structures (mean MR = 77.3%), with missing mapping primarily occurring in low-pLDDT scoring regions, including terminal regions and random coils [25].

Table 1: Structural Conservation Analysis Across Metabolic Pathways

| Pathway Type | Conservation Pattern | Key Findings | Notable Enzyme Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central Carbon Metabolism | High divergence in fermenting vs. non-fermenting species | Enzymes showed specialization based on metabolic capabilities | Kgd2p (TCA cycle), Cox7p (respiratory chain) |

| Purine & Amino Acid Biosynthesis | High structural conservation | Early pathway enrichment with high AUC values | Multiple enzymes in purine and specific amino acid biosynthesis pathways |

| Xylose Utilization | Specialization based on substrate use | Differential conservation in acetyl-CoA synthase paralogs | Acs1p (aerobic), Acs2p (anaerobic) |

| Membrane-Associated Metabolism | High divergence | Enriched in "membrane" and "lipid metabolism" GO terms | Erg1p (ergosterol biosynthesis), Met10p (sulfur cycle) |

Metabolic Specialization and Structural Divergence

Structural analysis revealed that metabolic specializations at the species level are reflected in enzyme structures. Enzymes from species capable of fermenting glucose, raffinose, galactose, and sucrose showed significant differences in conservation ratios compared to non-fermenting species [25]. Similarly, enzymes from species growing aerobically on d-xylose displayed distinct structural patterns [25]. The orthogroups of enzymes involved in central carbon metabolism and the electron transport chain showed some of the largest differences in CR between metabolic phenotypes, indicating specialized evolutionary trajectories for enzymes directly related to oxidative metabolism [25].

Network-Scale Regulation of Enzyme Activity

Enzyme Activation Networks

Beyond structural evolution, metabolic regulation occurs through intricate networks of enzyme-metabolite interactions. A comprehensive study integrating the Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolic network with cross-species enzyme kinetic data from the BRENDA database revealed extensive regulatory crosstalk between metabolic pathways [26]. The constructed cell-intrinsic activation network comprised 1,499 activatory interactions involving 344 enzymes and 286 cellular metabolites, demonstrating that 54% of metabolic enzymes are intracellularly activated [26].

Table 2: Enzyme-Metabolite Activation Network Properties

| Network Component | Quantity | Percentage of Total | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activated Enzymes | 344 | 54% of metabolic enzymes | Indicates widespread regulatory potential |

| Activator Metabolites | 286 | 20.7% of metabolome | Essential metabolites predominantly serve as activators |

| Activation Interactions | 1,499 | Scale-free distribution | Network follows power law distribution |

| Non-activated Enzymes | 170 | 27% of metabolic enzymes | Includes enzymes activated by extracellular molecules |

Principles of Metabolic Regulation

The activation network analysis revealed several fundamental principles of metabolic regulation. First, activators have short pathway lengths, indicating they are produced quickly upon nutrient shifts, enabling rapid metabolic adaptation [26]. Second, activators frequently target key enzymatic reactions to facilitate downstream metabolic processes, with highly activated enzymes substantially enriched with non-essential enzymes compared to their essential counterparts [26]. This suggests that cells employ enzyme activators to finely regulate secondary metabolic pathways required under specific conditions, while the activator metabolites themselves are more likely to be essential components [26]. Finally, the network analysis demonstrated that enzyme-metabolite activation interactions primarily exhibit transactivation between pathways, in contrast to inhibitory interactions that predominantly involve self-inhibition within pathways [26].

Figure 1: Metabolic Regulation via Enzyme Activation Network. This diagram illustrates how essential metabolites produced shortly after nutrient shifts activate enzymes in conditional metabolic pathways, enabling rapid metabolic adaptation through trans-activation between pathways.

Methodologies for Investigating Enzyme Mechanisms

Computational Approaches for Mechanism Elucidation

Understanding enzyme reaction mechanisms is fundamental to studying biochemical processes and has important applications in drug discovery and catalyst design. Computational methods provide unique insights into mechanisms that are difficult to obtain experimentally, including structures of transition states and reaction intermediates [27]. Several computational approaches are commonly employed:

Quantum Mechanical (QM) Methods describe the distributions of electrons in molecules explicitly and can model bond breaking and formation. Density functional theory (DFT) methods offer a balance between accuracy and computational expense, while correlated ab initio methods (e.g., MP2, CI, CC) provide higher accuracy but with greater computational demands [27].

Molecular Mechanics (MM) Methods use simple potential functions to simulate protein dynamics but cannot typically model chemical reactions. They are valuable for simulating enzyme dynamics on nano- to microsecond timescales and are often combined with QM methods in QM/MM calculations [27].

Knowledge-Based Approaches, such as EzMechanism, leverage the growing literature on enzyme mechanisms to automatically propose catalytic mechanisms for given three-dimensional active sites [28]. This tool uses catalytic rules compiled from the Mechanism and Catalytic Site Atlas (M-CSA) database, containing over 7,000 catalytic rules derived from 691 enzymes and 2,925 catalytic steps [28].

Experimental Validation and Kinetic Characterization

Experimental protocols for validating enzyme mechanisms and kinetics include:

Kinetic Assays determine enzymatic reaction rates and their dependence on pH, temperature, or chemical species such as cofactors. These assays provide fundamental data on enzyme function and can help distinguish between possible mechanisms [27].

Mutagenesis Studies confirm the roles of potential catalytic residues identified among highly conserved residues. Replacing suspected catalytic residues and measuring the impact on activity provides evidence for their involvement in the mechanism [27] [28].

Spectroscopy Methods, such as electron paramagnetic resonance for metals and radical species or fluorescence for fluorescent intermediates, can confirm or exclude the presence of certain molecular species along the reaction path [27].

Structural Studies using X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy, or NMR provide information about the precise location of catalytic residues, substrates, and cofactors in the active site, offering crucial constraints for proposed mechanisms [27] [28].

Figure 2: Workflow for Computational Enzyme Mechanism Elucidation. This diagram outlines the knowledge-based approach for proposing and validating enzyme reaction mechanisms, combining structural data with catalytic rules from literature-curated databases.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Enzyme and Metabolic Network Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Key Functions | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | Enzyme Kinetic Database | Comprehensive enzyme functional data, including kinetic parameters, activators, inhibitors | Network modeling of metabolic regulation [26] |

| AlphaFold DB | Protein Structure Database | Predicted protein structures for numerous species | Evolutionary analysis of enzyme structures [25] |

| M-CSA (Mechanism and Catalytic Site Atlas) | Mechanistic Database | Curated enzyme reaction mechanisms with catalytic steps | Knowledge-based mechanism prediction [28] |

| BioCyc Collection | Metabolic Pathway Database | 371 pathway/genome databases with metabolic network information | Pathway analysis and network reconstruction [29] |

| KEGG | Pathway Database | Reference metabolic pathways across 700+ species | Comparative pathway analysis and enrichment [29] |

| QM/MM Software | Computational Tool | Simulates enzyme-catalyzed reactions with quantum accuracy | Mechanism validation and transition state analysis [27] |

Metabolic Pathway Databases for Network Analysis

Several specialized databases support metabolic network reconstruction and analysis:

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) provides one of the most complete and widely used databases containing metabolic pathways (372 reference pathways) from over 700 species [29]. These pathways are hyperlinked to metabolite and protein/enzyme information, with over 15,000 compounds, 7,742 drugs, and nearly 11,000 glycan structures [29].

MetaCyc contains nonredundant, experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways with more than 1,100 pathways from over 1,500 different species [29]. It is curated from the scientific experimental literature and includes pathways involved in both primary and secondary metabolism [29].

Reactome offers a curated, peer-reviewed knowledgebase of biological pathways, including metabolic pathways as well as protein trafficking and signaling pathways [29]. It includes data and pathway diagrams for over 2,700 proteins, 2,800 reactions, and 860 pathways for humans [29].

SMPDB (The Small Molecule Pathway Database) provides exquisitely detailed, fully searchable, hyperlinked diagrams of human metabolic pathways, metabolic disease pathways, metabolite signaling pathways, and drug-action pathways [30].

Enzymes function as catalytic drivers within metabolic networks through evolutionarily optimized structures, sophisticated activation mechanisms, and precisely tuned reaction mechanisms. The integration of structural biology with evolutionary genomics reveals that enzyme evolution is intrinsically governed by catalytic function and shaped by metabolic niche, network architecture, cost, and molecular interactions [25]. Meanwhile, network-scale analyses demonstrate that metabolic regulation occurs through extensive activator networks exhibiting trans-pathway crosstalk, with essential metabolites frequently activating conditionally required enzymes [26]. Computational methods for elucidating enzyme mechanisms continue to advance, with knowledge-based approaches complementing first-principles simulations [27] [28]. These fundamental principles of enzyme function and regulation provide the foundation for targeted metabolic pathway modulation with applications in therapeutic development, metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology. The ongoing development of comprehensive databases and analytical tools will further enhance our ability to understand and manipulate these essential catalytic drivers of cellular metabolism.

Metabolic dysregulation represents a fundamental disruption in the intricate network of biochemical processes that maintain cellular homeostasis, emerging as a critical driver in the pathophysiology of diverse diseases. The core principle of metabolic pathway modulation research rests on understanding how perturbations in essential pathways—including glucose metabolism, mitochondrial function, and lipid homeostasis—initiate and propagate disease processes across organ systems. Evidence now clearly establishes that metabolic dysfunction is not merely a secondary consequence but a primary pathogenic mechanism in conditions ranging from neurodegenerative disorders to hepatic disease [31] [32]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms linking metabolic dysregulation to disease pathophysiology, with specific focus on quantitative assessments, experimental methodologies, and core signaling pathways relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

The centrality of metabolic health to overall physiological function is exemplified by the fact that impaired glucose metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and lipid dysregulation are frequently observed in the brains of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients, suggesting that metabolic dysfunction exacerbates neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits [31]. Similarly, in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), dysregulated hepatic metabolism manifests as chronic inflammation, progressive fibrosis, and ultimately cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma [15] [21]. These examples underscore the systems-level impact of metabolic dysregulation and highlight the potential for therapeutic interventions targeting metabolic pathways.

Core Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Energy Production Deficits

At the cellular level, metabolic dysregulation frequently manifests as bioenergetic failure through impaired glucose metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction. In Alzheimer's disease, impaired cerebral glucose utilization leads to neuronal energy deficits and synaptic dysfunction [31]. Research indicates that disruptions in metabolic pathways such as glycolysis or oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) lead to redox stress, bioenergetic failure, and toxic protein accumulation, thereby exacerbating neurodegeneration in cognitive disorders [33]. Neurons appear to strategically limit glycolysis to prevent mitochondrial dysfunction and cognitive decline, with excessive glycolysis disrupting mitochondrial function, though these effects can be reversed by restoring NAD+ or reducing mitochondrial stress [33].

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway represents another crucial node in metabolic regulation, with demonstrated significance in Alzheimer's disease pathology. As mTOR is activated through insulin/IGF signaling, evidence suggests that diabetes and insulin resistance contribute to its dysregulation, creating a bridge between peripheral metabolic dysfunction and central nervous system pathology [32].

Signaling Pathway Disruptions

The gut-brain axis serves as a central signaling hub coordinating metabolic processes across organ systems, with multiple hormones acting through specific signaling pathways to regulate appetite, insulin secretion, and body weight [34]. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) exemplifies this regulatory complexity, operating through central signaling pathways to exert systemic metabolic effects. Through the gut-brain axis, GLP-1 stimulates insulin secretion, enhances insulin sensitivity, delays gastric emptying, suppresses appetite, and influences lipid metabolism [34].

Research has identified glucose-sensitive neurons in the dorsomedial nucleus (DMN) of the brain that express GLP-1 receptors (GLP-1R). These neurons inhibit delayed rectifier potassium channels and lower blood glucose levels through activation of the AMP-protein kinase A (cAMP-PKA) pathway [34]. In the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), GLP-1 influences feeding behavior by modulating postsynaptic membrane excitability, likely mediated through the AC-cAMP-PKA pathway, leading to phosphorylation of serine 845 on the GluA1 subunit of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid receptors (AMPARs) [34]. This phosphorylation promotes recruitment of AMPARs to the membrane, enhances excitatory postsynaptic potentials, and consequently inhibits feeding behavior [34].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Signaling Pathways in Disease

| Pathway | Key Components | Physiological Role | Dysregulation Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| GLP-1R Signaling | GLP-1, GLP-1R, cAMP, PKA, AMPAR | Appetite regulation, Insulin secretion, Glucose homeostasis | Appetite dysregulation, Hyperglycemia, Impaired insulin sensitivity [34] |

| mTOR Signaling | mTOR, Insulin/IGF receptors, downstream effectors | Nutrient sensing, Protein synthesis, Neuronal survival | Insulin resistance, Neuronal dysfunction, Alzheimer's pathology [32] |

| GLP-2R Signaling | GLP-2, GLP-2R, PI3K, Akt, FoxO1 | Intestinal mucosal growth, Glucose homeostasis | Impaired intestinal barrier function, Glucose dysregulation [34] |

| AMPK Signaling | AMPK, upstream kinases, metabolic enzymes | Energy sensing, Mitochondrial biogenesis | Bioenergetic failure, Impaired myelin repair [32] |

Proteostasis Disruption

Recent research has revealed intriguing connections between metabolic intermediates and protein homeostasis. β-hydroxybutyrate (βHB), a ketone body produced during fasting or carbohydrate restriction, has been shown to regulate protein solubility by selectively insolubilizing pathological proteins such as amyloid beta, facilitating their clearance and reducing toxicity in Alzheimer's disease contexts [33]. This mechanism represents a direct link between systemic metabolic states and the management of proteotoxic stress in neurodegenerative conditions.

Simultaneously, chronic hyperglycemia induces mitochondrial alterations in specific brain regions, including the medial habenula and interpeduncular nucleus—areas linked to mood disorders, addiction, and anxiety [32]. Research using mouse models has identified early, transient changes in mitochondrial morphology and increases in mitochondrial numbers in the medial habenula, which normalize over time, alongside alterations in neural lipid composition in the interpeduncular nucleus [32].

Quantitative Analysis of Metabolic Dysregulation

Disease-Specific Metabolic Alterations

Quantitative assessments of metabolic dysregulation provide crucial insights into disease severity and progression. In MASH, semaglutide treatment demonstrates dose-dependent improvements across multiple histological parameters. Proteomic analyses of serum samples from patients with MASH identified 72 proteins significantly associated with MASH resolution and semaglutide treatment, with most related to metabolism and several implicated in fibrosis and inflammation [15] [21].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Semaglutide on MASH Histological Parameters

| Parameter | Semaglutide 0.1 mg | Semaglutide 0.2 mg | Semaglutide 0.4 mg | Placebo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steatosis Resolution | 26% | 43% | 55% | 9% |

| Inflammation Improvement | 53% | 71% | 82% | 32% |

| Ballooning Improvement | 52% | 65% | 80% | 29% |

| Fibrosis Improvement | 44% | 48% | 57% | 16% |

Aptamer-based proteomic analyses further quantified treatment effects on specific protein markers. For steatosis, two proteins (PTGR1 and GUSB) showed statistically significant lower abundance for semaglutide 0.4 mg versus placebo [15]. For hepatocyte ballooning, three proteins (PTGR1, AKR1B10 and ADAMTSL2) showed significant improvement with semaglutide 0.4 mg treatment, while five proteins (ACY1, TXNRD1, FCGR3B, ADIPOQ and RPN1) demonstrated significant improvement for lobular inflammation [15]. These protein signatures not only provide biomarkers for treatment response but also insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying metabolic dysresolution.

Therapeutic Efficacy Metrics

The efficacy of metabolic interventions varies considerably across modalities, highlighting the importance of quantitative comparisons. Behavioral interventions typically lead to a 5–10% weight loss, while GLP-1 receptor agonists can result in an 8–21% reduction, and bariatric surgery achieves a weight loss of 25–30% [34]. This hierarchy of efficacy provides valuable guidance for selecting appropriate intervention intensities based on disease severity.

In Alzheimer's disease, targeting metabolic pathways has shown promising quantitative outcomes in preclinical models. Inhibition of IDO1, which metabolizes tryptophan to kynurenine, restores astrocyte metabolism and improves hippocampal glucose metabolism, leading to the rescue of memory function [33]. Similarly, restoration of NAD+ or reduction of mitochondrial stress reverses the cognitive decline associated with excessive glycolysis [33].

Table 3: Efficacy Metrics of Metabolic-Targeted Therapies Across Diseases

| Therapy | Condition | Primary Efficacy Metric | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide | MASH | Histological resolution without fibrosis worsening | 59% vs 17% with placebo [15] |

| GLP-1 RAs | Obesity | Weight reduction | 8-21% [34] |

| Bariatric Surgery | Obesity | Weight reduction | 25-30% [34] |

| Metformin | Multiple Sclerosis | Enhanced oligodendrocyte differentiation | Improved myelin repair and function [32] |

| IDO1 Inhibition | Alzheimer's Disease | Rescue of memory function | Restoration of hippocampal glucose metabolism [33] |

Experimental Methodologies for Metabolic Pathway Analysis

Pathway Mapping and Analysis Techniques

Elementary mode analysis of metabolic pathways has proven to be a valuable tool for assessing the properties and functions of biochemical systems [35]. This approach involves decomposing steady-state flux distributions to understand how individual elementary modes are used in real cellular states, helping identify dominant metabolic processes and understand how these processes redistribute in biological cells in response to changes in environmental conditions, enzyme kinetics, or chemical concentrations [35].

Application of this methodology to yeast glycolysis revealed that among eight possible elementary modes, the standard glycolytic route (EM8) remains dominant in all cases (elementary mode flux value of 55.5), with only one other elementary mode (EM7, combining ethanol production with derived glycerol production from DHAP) able to gain significant flux values (18.2) in steady state [35]. These results indicate that a combination of structural and kinetic modelling significantly constrains the range of possible behaviors of a metabolic system, with not all elementary modes contributing equally to physiological cellular states [35].

Functional Assessment Assays

Key methodological approaches for evaluating metabolic function include:

OCR and ECAR measurements: Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) measurements are key to assessing metabolic changes, particularly in neuronal and hepatic systems [33]. These parameters provide quantitative assessment of mitochondrial function and glycolytic activity, respectively.

Mitochondrial function assays: Mitochondrial abnormalities, which are directly related to metabolic dysfunction and cell death, can be assessed by various indicators, including measurements of mitochondrial membrane potential, detection of ROS levels, and observation of mitophagy [33].

Aptamer-based proteomics: The SomaScan aptamer-based proteomics approach employs predefined suites of SomaSignal tests validated against tissue histology to grade and stage metabolic parameters such as steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning, and liver fibrosis comprising 12, 14, 5, and 8 protein analytes, respectively [15].

Protein aggregation studies: Aβ aggregation, a key factor in Alzheimer's disease, is often studied in vitro under conditions that promote aggregation, though recent approaches use ex vivo experiments with brain lysates to better mimic physiological conditions [33].

Visualization of Key Metabolic Pathways

GLP-1 Signaling in the Gut-Brain Axis

The following diagram illustrates the central signaling pathways of GLP-1 through the gut-brain axis, highlighting key molecular interactions and their metabolic outcomes:

Graph 1: GLP-1 Signaling Pathways in Metabolic Regulation. This diagram illustrates the dual pathways through which GLP-1 exerts its central metabolic effects: via vagal nerve activation and direct receptor-mediated signaling in hypothalamic nuclei. Key outcomes include insulin secretion and appetite suppression through distinct molecular mechanisms.

Integrated Metabolic Dysregulation in Neurodegeneration

The following diagram provides a systems view of metabolic dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease, integrating multiple pathological mechanisms:

Graph 2: Integrated Metabolic Dysregulation in Alzheimer's Disease Pathophysiology. This systems diagram illustrates how primary metabolic disturbances converge on proteostasis failure and neuroinflammation, ultimately driving cognitive decline through multiple interconnected pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table provides key research tools and reagents essential for investigating metabolic dysregulation in disease contexts:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Dysregulation Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Application | Key Features | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCR Assay Kits | Mitochondrial function assessment | Measurement without Seahorse analyzer required | Assessing metabolic changes in Alzheimer's models [33] |

| Mitochondrial Function Kits | Membrane potential, ROS detection | Multiple parameter assessment | Evaluating mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegeneration [33] |

| SomaScan Platform | Aptamer-based proteomics | Analysis of 72+ proteins associated with metabolism | Identifying protein signatures in MASH resolution [15] |

| SomaSignal Tests | Histological component prediction | Steatosis (12 proteins), inflammation (14 proteins), ballooning (5 proteins), fibrosis (8 proteins) proteomic surrogates | Grading/staging MASH components non-invasively [15] |

| GLP-1R Agonists | Pathway modulation studies | Receptor-specific activation | Investigating gut-brain axis signaling [34] |

| βHB Assays | Ketone body quantification | Metabolic regulator analysis | Studying proteostasis regulation in Alzheimer's models [33] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The expanding recognition of metabolic dysregulation as a fundamental disease driver necessitates continued refinement of our analytical approaches and therapeutic strategies. The emerging field of precision medicine offers opportunities to tailor interventions based on individual metabolic profiles, potentially enhancing treatment efficacy [31]. Despite the growing recognition of metabolic dysfunction in various diseases, translating these insights into effective therapies remains challenging due to disease complexity and heterogeneity [31].

Future research must focus on elucidating the interplay between metabolic pathways and disease pathology, identifying reliable biomarkers, and designing targeted interventions. The combination of structural and kinetic modeling significantly constrains the range of possible behaviors of a metabolic system, suggesting that not all stoichiometrically feasible states are physiologically relevant [35]. This insight should guide the development of more refined metabolic network models that better capture in vivo pathophysiology.

Novel approaches including quantitative elementary mode analysis, aptamer-based proteomic profiling, and integrated pathway mapping provide powerful methodological frameworks for advancing our understanding of metabolic dysregulation across disease contexts. By addressing the metabolic underpinnings of diverse conditions, researchers can develop novel and integrative therapeutic strategies to slow or prevent disease progression and improve patient outcomes [31].

Advanced Methodologies and Therapeutic Applications in Pathway Modulation

Aptamer-based proteomics has emerged as a powerful technological platform for high-throughput protein biomarker discovery and drug mechanism elucidation. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles and applications of this technology in identifying proteomic signatures of drug action, framed within the broader context of metabolic pathway modulation research. By leveraging single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides with high affinity for specific protein targets, researchers can systematically characterize complex biological responses to pharmacological interventions, enabling the discovery of novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers for drug development. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive overview of the methodology, analytical considerations, and practical implementation strategies for deploying aptamer-based proteomics in pharmaceutical research and development.

Aptamer-based proteomics represents a transformative approach in functional proteomics, enabling researchers to profile thousands of proteins simultaneously with exceptional specificity and sensitivity. Single-stranded DNA aptamers are oligonucleotides of approximately 50 base pairs in length that are selected for their ability to bind target proteins with high specificity and affinity [36]. These aptamers are developed through an in vitro evolution process known as Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX), which involves multiple automated rounds of positive and negative selection to identify strongly selective aptamers [37].