Monte Carlo Sampling for 13C Isotope Tracing: A Foundational Guide to Flux Analysis, Uncertainty, and Model Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the application of Monte Carlo sampling in 13C-based metabolic flux analysis (MFA), a critical technique for quantifying reaction rates in living cells.

Monte Carlo Sampling for 13C Isotope Tracing: A Foundational Guide to Flux Analysis, Uncertainty, and Model Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the application of Monte Carlo sampling in 13C-based metabolic flux analysis (MFA), a critical technique for quantifying reaction rates in living cells. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of using Monte Carlo to simulate feasible metabolic states without prior assumption of the flux distribution. The scope extends to practical methodologies for experiment design and optimization, strategies for troubleshooting uncertainty in flux estimates, and advanced protocols for model selection and validation. By synthesizing these core intents, this resource aims to empower scientists to design more robust isotope tracing experiments, leading to more reliable insights into metabolic pathways in health and disease.

Foundations of Monte Carlo Sampling in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

Background and Fundamental Principles

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a cornerstone technique in quantitative systems biology used to estimate in vivo metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) in living cells [1]. By tracking the incorporation of stable 13C isotope from labeled substrates into intracellular metabolites, researchers can infer metabolic pathway activities that are crucial for understanding cellular physiology in bioengineering, medicine, and basic research [2] [3].

The core principle involves cultivating cells on a 13C-labeled carbon source, followed by measuring the resulting 13C labeling patterns in metabolic products using mass spectrometry [2]. The Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID), which represents the fractional abundances of different mass isomers of metabolites, is then used to compute metabolic fluxes [4]. This inverse problem—calculating fluxes from labeling data—is computationally challenging and represents a central focus of 13C-MFA methodology [2].

Core Challenges in 13C-MFA

Despite its powerful capabilities, 13C-MFA faces several significant methodological challenges that impact its resolution and practical implementation.

Table 1: Key Challenges in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Challenge | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| High Measurement Redundancy | Considerable dimensionality in isotopomer data is less than anticipated, creating informational redundancy [2]. | Limits unique information obtained per experiment; constrains flux resolution across large networks [2] [5]. |

| Optimal Tracer Design | The choice of carbon labeling pattern in the input substrate significantly influences the ability to determine specific reaction fluxes [2]. | Suboptimal label selection yields poor flux resolution; optimal patterns are often complex and not commercially available [2]. |

| Computational Complexity | The inverse problem of calculating flux distributions from labeling data is non-linear and computationally intensive [2]. | Requires sophisticated algorithms and high-performance computing for large-scale networks [1]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Precise determination of confidence intervals for estimated fluxes is essential for biological interpretation [4]. | Traditional methods like grid search are computationally expensive; Bayesian approaches are emerging [6] [1]. |

A critical insight from computational analysis is that the effectiveness of 13C experiments for determining reaction fluxes across large-scale metabolic networks is less than previously believed due to inherent limitations in data dimensionality [2] [5]. This necessitates careful experimental design and appropriate computational tools to address specific biological questions effectively.

Monte Carlo Sampling for 13C-MFA

Monte Carlo sampling approaches address several core challenges by generating a uniform set of biochemically feasible flux distributions that obey metabolic constraints [2]. This method enables a priori prediction of how well a proposed labeling experiment can resolve specific metabolic fluxes.

Methodology and Workflow

The Monte Carlo sampling workflow for 13C-MFA involves several key stages that integrate computational modeling with experimental design.

Key Algorithmic Steps

Network Construction: A metabolic network reconstruction defines reaction stoichiometries and carbon atom transitions [2]. The Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework is commonly used to model these transitions efficiently [6] [1].

Flux Space Sampling: A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm samples the convex solution space of feasible steady-state flux distributions, creating a representative set of possible metabolic states [2] [6].

Hypothesis Testing: The sampled flux distributions are partitioned based on experimental objectives (e.g., high vs. low flux through a specific reaction). Isotopomer distributions from different partitions are compared using statistical metrics (e.g., Z-scores) to determine distinguishability [2].

This approach allows researchers to compute potential limitations before conducting expensive experiments and predict whether, and to what degree, specific reaction rates can be resolved [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Global 13C Tracing in Human Liver Tissue Ex Vivo

This protocol adapts recent methodology for measuring metabolic fluxes in intact human liver tissue [3], demonstrating the application of 13C-MFA to complex human systems.

Table 2: Protocol for Ex Vivo Human Liver 13C Tracing

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Preparation | Section fresh human liver tissue into 150-250 μm slices using a vibratome. Culture on membrane inserts. | Maintain tissue viability; ATP content >5 μmol/g protein indicates metabolic health [3]. |

| Tracer Incubation | Replace culture medium with fully 13C-labeled medium containing all 20 amino acids plus glucose. | Ensure nutrient perfusion; monitor essential AA enrichment reaching 60-80% at 2 hours [3]. |

| Metabolite Extraction | Quench metabolism at specific time points (2-24 hours). Extract polar metabolites using cold methanol:water solution. | Preserve metabolic state; avoid degradation of labile metabolites [3]. |

| LC-MS Analysis | Analyze metabolites using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). | Non-targeted approach enables detection of ~733 metabolite peaks; track 13C incorporation [3]. |

| Data Processing | Calculate Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) for detected metabolites. | Compare MIDs between medium and tissue to identify sequestered metabolite pools [3]. |

| Flux Analysis | Perform Metabolic Flux Analysis using appropriate software (e.g., OpenMebius, 13CFLUX). | Optimize flux distribution to minimize residual sum of squares between simulated and measured MIDs [4]. |

Key Technical Considerations

- Tissue Viability Assessment: Monitor albumin production (10-30 mg/g liver/day), APOB secretion (50-200 μg/g liver/day), and urea formation (5-10 mg/g liver/day) as functional viability markers [3].

- Labeling Time Course: Essential amino acids typically reach 60-80% 13C enrichment within 2 hours, though complete labeling may be limited by unlabeled protein turnover [3].

- Environmental Context: Supplementation with 50% dialysed human serum provides fatty acids and insulin, creating more physiologically relevant conditions [3].

Computational Tools and Software Solutions

Multiple software platforms have been developed to address the computational demands of 13C-MFA, each with distinct capabilities and methodological approaches.

Table 3: Software Tools for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Software | Key Features | Methodological Basis |

|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX(v3) [1] | High-performance C++ engine with Python interface; supports isotopically stationary/nonstationary MFA; Bayesian inference. | Cumomers and Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU); dimension-reduced state spaces. |

| METRAN [7] | 13C-MFA, tracer experiment design, and statistical analysis. | Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework. |

| BayFlux [6] | Bayesian genome-scale 13C MFA; Two-Scale MFA with optional add-on. | Monte Carlo sampling; integrates with COBRApy for constraint-based modeling. |

| OpenMebius [4] | Flux distribution optimization to minimize residual sum of squares. | EMU framework; confidence intervals via grid search. |

The integration of Bayesian approaches with traditional 13C-MFA represents a significant advancement, allowing comprehensive uncertainty quantification and leveraging prior knowledge for more robust flux estimation [6] [1].

Experimental Design and Reagent Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for 13C-MFA

| Reagent/Category | Function in 13C-MFA | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Carbon source for tracing metabolic pathways; choice of labeling pattern affects flux resolution. | Fully labeled glucose; uniformly labeled amino acid mixtures; complex patterns often outperform commercial options [2]. |

| Culture Media Components | Maintain cell viability while introducing 13C tracers; composition affects metabolic state. | Fasting-state plasma-like nutrient levels; serum supplementation for physiological relevance [3]. |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits | Assess functional viability of biological systems during tracing experiments. | Albumin, urea, triglyceride quantification assays [3]. |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvents | Quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites for MS analysis. | Cold methanol:water solutions; proper quenching preserves metabolic state [3]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry for MID measurement. | Ultra-pure solvents for precise metabolite separation and detection [3]. |

Optimizing Tracer Design

The fundamental principle for effective experimental design is that the choice of optimal labeled substrate depends on the desired experimental objective [2]. This necessitates computational evaluation of different labeling patterns for their ability to resolve specific metabolic fluxes before conducting wet-lab experiments.

This systematic approach to tracer design emphasizes that complex labeling patterns often outperform commercially available substrates for resolving specific metabolic fluxes [2]. Computational frameworks like Monte Carlo sampling enable researchers to identify these optimal patterns before conducting costly laboratory experiments.

The Role of Monte Carlo Sampling in Exploring Metabolic Flux Spaces

Metabolic fluxes, defined as the rates of metabolic reactions within a cell, are pivotal for understanding cellular physiology as they determine the flow of carbon and energy that enables cell survival and growth [8]. However, unlike molecular quantities such as metabolites or proteins, fluxes cannot be measured directly and must be inferred computationally from experimental data [8] [9]. Constraint-based modeling provides a powerful framework for this analysis by imposing mass balance and steady-state constraints on the metabolic network, defining a closed convex solution space known as a flux polytope [10]. Uniform sampling from this polytope enables the statistical characterization of metabolic behavior, yielding probability distributions for fluxes rather than single points [10].

Monte Carlo sampling has emerged as a critical technique for exploring these high-dimensional flux spaces, especially for genome-scale models where deterministic solutions are infeasible [10] [2]. As a computational algorithm that uses repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results, Monte Carlo simulation is ideally suited to investigate the underdetermined systems typical of metabolic networks [11]. By generating a uniform set of feasible flux distributions, Monte Carlo methods allow researchers to characterize the solution space statistically, assess the impact of uncertainties, and make robust predictions about metabolic function without presupposing a single biological objective [10] [2].

Monte Carlo Sampling Methods for Flux Space Exploration

Algorithmic Foundations and Comparative Performance

Several Monte Carlo sampling algorithms have been developed specifically for navigating the complex flux spaces of metabolic networks. The performance of these algorithms varies significantly in terms of their convergence properties, consistency, and efficiency, particularly when applied to genome-scale models [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Monte Carlo Sampling Algorithms for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Algorithm | Full Name | Formulation | Key Characteristics | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHRR | Coordinate Hit-and-Run with Rounding [10] | Deterministic [10] | Guaranteed distributional convergence; Uses rounding procedures to remove solution space heterogeneity [10] | Performs best among algorithms for deterministic formulation [10] |

| ACHR | Artificial Centering Hit-and-Run [10] | Deterministic [10] | Copes with anisotropy in high-dimensional polytopes; Non-Markovian nature can cause convergence issues [10] | High consistency with CHRR for genome-scale models [10] |

| OPTGP | Optimized General Parallel Sampler [10] | Deterministic [10] | Based on ACHR; Implemented in COBRApy [10] | Suffers from similar convergence problems as ACHR [10] |

| Gibbs Sampler | Gibbs Sampling [10] | Stochastic [10] | Appropriate for sampling truncated multivariate normal distributions at genome scale [10] | Less efficient than samplers for deterministic formulation [10] |

The fundamental challenge these algorithms address is sampling from the convex polytope defined by the steady-state mass balance (Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector) and capacity constraints (vlb ≤ v ≤ vub) [10]. The standard Hit-and-Run (HR) algorithm, a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method, operates by starting at an arbitrary point within the polytope and iteratively: (1) choosing a random direction uniformly distributed on the unit sphere, (2) computing the minimum and maximum step sizes along that direction that keep the point within the polytope, and (3) moving to a new point chosen randomly along this feasible line segment [10].

Deterministic vs. Stochastic Formulations

Monte Carlo sampling in metabolic flux analysis can be applied to two distinct mathematical formulations, each with different implications for how experimental data and biological assumptions are incorporated:

- Deterministic Formulation: This approach imposes an exact steady-state constraint (Sv = 0) and incorporates flux measurements without accounting for experimental noise. The solution space is a convex polytope, and algorithms like CHRR, ACHR, and OPTGP are designed to sample uniformly from this space [10].

- Stochastic Formulation: This more flexible framework relaxes the exact steady-state requirement and explicitly incorporates experimental noise and measurement uncertainty. This formulation results in a more complex solution space that is not necessarily convex, with the Gibbs sampler being the primary method appropriate for genome-scale models in this context [10].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these formulations and their corresponding sampling algorithms:

Application Notes: Monte Carlo Sampling in 13C Isotope Tracing Experiments

Protocol: Designing Optimal 13C Labeling Experiments Using Monte Carlo Sampling

Purpose: To computationally determine the optimal 13C substrate labeling pattern for resolving specific metabolic fluxes or flux ratios before conducting wet-lab experiments [2] [5].

Background: The choice of carbon labeling pattern significantly affects the ability of 13C experiments to determine intracellular reaction fluxes. Monte Carlo sampling provides a method to evaluate different labeling patterns without assuming the true flux distribution beforehand [2].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA Experiments

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1,2-13C] Glucose; [1,6-13C] Glucose; Uniformly labeled [U-13C] Glucose; 13C-CO2; 13C-NaHCO3 [12] | Carbon source that introduces measurable labels into metabolic network for tracking carbon fate [12] |

| Isotopomer Model | Expanded E. coli isotopomer model (313 irreversible reactions) [2] | Computational representation of network stoichiometry and carbon atom transitions for simulating labeling patterns [2] |

| Analytical Instruments | Mass Spectrometry (MS); Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [12] | Measurement of Mass Distribution Vectors (MDVs) or isotopomer distributions from labeled metabolites [12] |

| Sampling Software | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB); COBRApy (Python) [10] | Implementation of ACHR, OPTGP, and CHRR sampling algorithms for constraint-based models [10] |

Methodology:

- Network Sampling: Generate a statistically representative set of feasible flux distributions for the metabolic network of interest using Monte Carlo sampling (e.g., ACHR or CHRR). This creates a uniform sampling of the feasible flux space constrained only by reaction stoichiometry and measured uptake/secretion rates [2].

- Isotopomer Simulation: For each sampled flux distribution v, use an isotopomer model to calculate the corresponding Isotopomer Distribution Vector (IDV) for the substrate labeling pattern being evaluated [2].

- Hypothesis Definition: Define the experimental objective as a partition of the sampled flux set. Common hypotheses include:

- Pattern Evaluation: Calculate a scoring metric (e.g., Z-score) that quantifies how well the labeling patterns from one partition are distinguishable from patterns in the other partition. A higher score indicates the labeling pattern is better for testing the specific hypothesis [2].

- Dimensionality Assessment: Apply singular value decomposition (SVD) to the simulated labeling data to determine the effective dimensionality and thus the information content of the experiment for resolving fluxes [2].

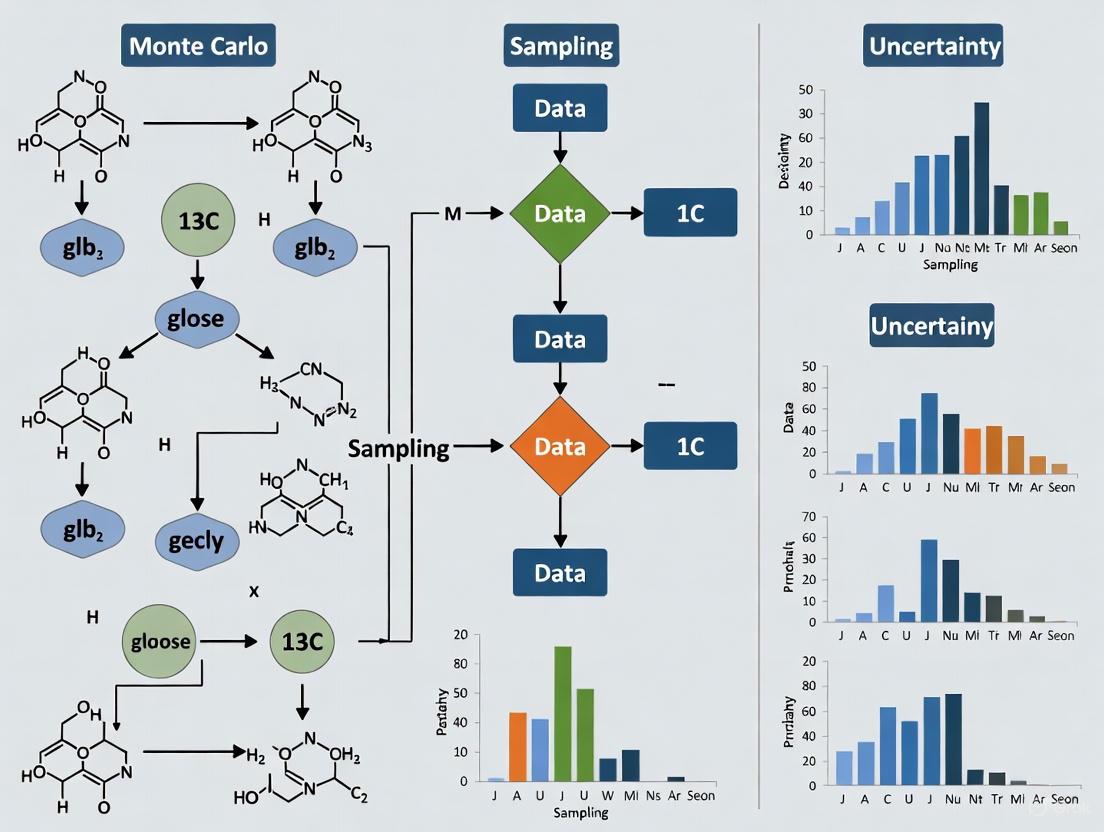

The following workflow diagram illustrates this protocol:

Protocol: Integrating 13C Labeling Data to Constrain Genome-Scale Models

Purpose: To incorporate data from 13C labeling experiments as constraints in genome-scale metabolic models, enabling more accurate flux predictions beyond central carbon metabolism [9].

Background: Traditional 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is typically limited to small models of central carbon metabolism due to computational complexity. The method described by GarcÃa MartÃn et al. (2015) uses 13C labeling data to provide strong flux constraints that eliminate the need for assuming evolutionary optimization principles like growth rate maximization used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [9].

Methodology:

- Experimental Data Collection: Grow cells on 13C-labeled substrate and measure the Mass Distribution Vector (MDV) for intracellular metabolites using Mass Spectrometry (MS) [9].

- Flux Constraint Definition: Implement the key assumption that flux flows from core to peripheral metabolism without flowing back. This biologically relevant constraint effectively reduces the solution space [9].

- Model Optimization: Calculate metabolic fluxes by solving a large-scale constrained non-linear least squares problem that minimizes the difference between experimentally measured MDVs and those simulated from assumed flux configurations [9].

- Validation and Refinement: Use the extra validation provided by matching multiple relative labeling measurements (e.g., 48 in the referenced study) to identify where existing COBRA flux prediction algorithms fail and refine these methods accordingly [9].

Key Applications and Advantages in Metabolic Research

Monte Carlo sampling provides several critical advantages for metabolic flux analysis and 13C isotope tracing experiments:

- Unbiased Exploration: Unlike optimization-based methods like FBA that assume a biological objective (e.g., growth maximization), Monte Carlo sampling uniformly explores the entire feasible flux space without presupposing cellular objectives [2].

- Uncertainty Quantification: By generating probability distributions for fluxes rather than point estimates, Monte Carlo methods naturally accommodate experimental noise and biological variability, providing confidence intervals for flux predictions [10] [13].

- Experimental Design: The ability to computationally test different substrate labeling patterns before conducting wet-lab experiments saves significant time and resources, while also establishing realistic expectations for what fluxes can be resolved by a given experiment [2] [5].

- Systematic Gap Identification: The comprehensive exploration of flux space helps identify inconsistencies in metabolic models and missing knowledge gaps in network reconstructions [9].

Research applying these methods to E. coli models has revealed that the effective dimensionality of 13C experimental data is considerably less than anticipated, suggesting inherent limitations in the amount of information that can be obtained from a single 13C labeling experiment [2] [5]. This insight is valuable for setting realistic expectations about flux resolution capabilities.

Monte Carlo sampling represents an indispensable methodology for exploring metabolic flux spaces, particularly when integrated with 13C isotope tracing experiments. By enabling unbiased statistical characterization of feasible flux distributions, accommodating measurement uncertainties, and facilitating optimal experimental design, these computational approaches provide a robust foundation for understanding metabolic network function. The continuing development of more efficient sampling algorithms like CHRR and their implementation in accessible software platforms ensures that Monte Carlo methods will remain central to advancing flux analysis in both basic metabolic research and applied biotechnology.

A fundamental challenge in traditional 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has been its reliance on assuming a predefined flux distribution before an experiment can be designed or interpreted. This prerequisite introduces significant bias, as the results are inherently constrained by the initial assumptions. However, a novel Monte Carlo sampling algorithm has emerged, revolutionizing this process by eliminating the need for an a priori flux assumption [14] [15]. This methodological advancement represents a significant paradigm shift in systems biology, enabling unbiased exploration of the complete feasible flux space and providing a more robust and objective foundation for designing tracer experiments and interpreting their results.

Core Principle of the Monte Carlo Approach: Instead of testing a single, presumed flux state, the method leverages Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) to define the universe of all biochemically possible flux distributions that obey known reaction stoichiometries and measured nutrient constraints [14]. A Markov Chain, Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm then uniformly samples this vast, high-dimensional space, generating a comprehensive set of possible flux maps [14]. By simulating the 13C labeling outcomes (isotopomer distribution vectors, or IDVs) for each of these diverse flux maps, researchers can preemptively evaluate which tracer designs best distinguish between alternative metabolic states for a given experimental objective, all without presupposing the true intracellular flux state [14].

Computational Methodology and Workflow

The implementation of this Monte Carlo approach involves a structured sequence of computational steps, transforming a genome-scale metabolic reconstruction into a tool for predictive experimental design.

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the protocol, from model preparation to the final evaluation of experimental designs.

Protocol Steps in Detail

Metabolic Network Expansion and Curation

- Begin with a core metabolic reconstruction (e.g., iJR904 for E. coli) containing central pathways like glycolysis, TCA cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway [14].

- Expand the model to include biosynthetic reactions for phospholipids, nucleotides, and co-factors from a comprehensive genome-scale network (e.g., iMC1010) [14].

- Identify and remove blocked reactions that cannot carry flux under the specified growth conditions (e.g., glucose minimal media). Group linear, sequential reactions to reduce model complexity and computational load. The final output is an isotopomer model that tracks carbon atom transitions across hundreds of reactions [14].

Monte Carlo Sampling of the Flux Space

- Apply the MCMC sampling algorithm to the constrained isotopomer model [14].

- The algorithm generates a large set (e.g., thousands) of flux distributions (

v) that are uniformly spread across the biochemically feasible solution space defined by the mass balance and uptake constraints [14]. - This collection of flux maps represents the full range of metabolic states the cell could potentially occupy, without bias toward a single, presumed state.

In Silico Tracer Experiment and Data Simulation

- For each sampled flux distribution (

v), simulate the steady-state 13C labeling pattern by calculating the Isotopomer Distribution Vector (IDV) for metabolites throughout the network [14]. - Convert the simulated IDVs into predicted Mass Distribution Vectors (MDVs), which are the actual data outputs obtained from Mass Spectrometry (MS) experiments [14]. This creates a massive in silico dataset linking potential flux states to measurable experimental outcomes for any given tracer.

- For each sampled flux distribution (

Hypothesis-Driven Tracer Evaluation

- Define a specific Experimental Objective. This is formalized as a hypothesis that partitions the sampled flux distributions into two groups [14]. Common objectives include:

- For each candidate tracer substrate (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose), calculate a Z-score that quantifies how well the tracer's simulated MDVs can distinguish between the two partitions of the hypothesis. A higher score indicates a superior tracer for that specific objective [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful application of this protocol depends on key computational and experimental reagents. The table below summarizes these essential components and their functions.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent / Tool Name | Type | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C] Glucose [16] | Tracer Substrate | A double-labeled carbon source that provides superior flux resolution compared to single-labeled tracers in complex networks. |

| Uniformly 13C-Labeled Glucose (13C6-Glc) [17] | Tracer Substrate | Used in non-steady-state experiments (SIRM) to trace atoms through entire metabolic networks. |

| COBRA Toolbox [14] | Computational Platform | Provides the foundation for constraint-based modeling, simulation, and analysis of metabolic networks. |

| MCMC Sampler [14] | Computational Algorithm | The core engine that performs the random sampling of the feasible flux space to generate possible flux distributions. |

| Isotopomer Model [14] | Computational Model | A curated metabolic network that explicitly tracks the position of 13C atoms in metabolites, enabling IDV/MDV simulation. |

| GC-MS or LC-MS/MS [16] | Analytical Instrumentation | Used to measure the mass distribution vectors (MDVs) of metabolites from actual biological samples after a tracer experiment. |

Experimental Design and Quantitative Outcomes

The power of the Monte Carlo method is demonstrated by its ability to quantitatively rank different tracer designs based on the specific biological question, leading to more informative and cost-effective experiments.

Application to Tracer Selection

The Monte Carlo approach reveals that the "optimal" labeled substrate is not universal but is intrinsically dependent on the specific reaction flux or flux ratio the researcher aims to resolve [14] [15]. For instance, a tracer that is excellent for elucidating pentose phosphate pathway activity may be suboptimal for analyzing TCA cycle anaplerotic fluxes. This method computationally tests various commercially available and complex tracer mixtures, predicting that many standard labels are outperformed by more sophisticated labeling patterns [14]. This allows for strategic investment in more expensive tracers like [1,2-13C] glucose, with the confidence that they will provide the necessary information gain [16].

Quantitative Scoring of Tracer Efficacy

The output of the analysis is a quantitative score for each tracer and hypothesis pair. The following table illustrates the type of comparative results generated by the Monte Carlo scoring metric.

Table 2: Illustrative Tracer Performance Scores for Example Metabolic Objectives

| Experimental Objective (Hypothesis) | Tracer A ([1-13C] Glucose) | Tracer B ([U-13C] Glucose) | Tracer C ([1,2-13C] Glucose) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux through PPP > Median Flux | Low (Z-score: 1.2) | Medium (Z-score: 2.1) | High (Z-score: 8.5) |

| Flux through Anaplerotic Reaction < Median Flux | Medium (Z-score: 2.3) | High (Z-score: 7.8) | Low (Z-score: 1.7) |

| Ratio of Glycolysis : TCA Flux > Threshold | High (Z-score: 8.1) | Medium (Z-score: 2.5) | Medium (Z-score: 2.9) |

Note: Z-scores are illustrative examples. Actual values are determined by the Monte Carlo simulation for a specific metabolic model and hypothesis [14].

A critical insight from this methodology is the assessment of the fundamental resolving power of 13C-MFA. The Monte Carlo analysis, combined with singular value decomposition, indicates that the intrinsic dimensionality of the information contained in 13C labeling data is often lower than previously assumed [14] [15]. This means there is high redundancy in the measurements, which inherently limits the number of independent fluxes that can be simultaneously resolved in a single experiment [14]. However, by using this Monte Carlo framework, researchers can now compute these limitations before an experiment is conducted, predicting whether, and to what degree, the rate of each reaction of interest can be resolved [14] [15].

Integrated Protocol for Practical Application

This section combines the computational and wet-lab procedures into a cohesive, actionable protocol for applying the Monte Carlo-powered experimental design.

Integrated Experimental Workflow

The entire process, from computational design to experimental validation, is summarized in the following workflow diagram.

Step-by-Step Guide

Computational Design Phase:

- Step 1: Load your organism-specific metabolic reconstruction into the COBRA/MCMC computational environment.

- Step 2: Apply the required constraints (e.g., glucose uptake rate, growth rate) and perform Monte Carlo sampling to generate the feasible flux set.

- Step 3: Formally define your experimental hypotheses (Hi-Lo flux or flux ratio objectives).

- Step 4: Simulate IDV/MDV data for all sampled flux points and all candidate tracers.

- Step 5: Calculate the Z-score for each tracer/hypothesis combination and select the tracer with the highest score for your primary objective.

Wet-Lab Execution Phase:

- Step 6: Culture and Tracer Experiment: Grow your biological system (e.g., E. coli, mammalian cells) in a steady-state chemostat or controlled batch culture. Switch the media to contain the optimal 13C-labeled substrate identified in Step 5. Ensure metabolic and isotopic steady state is reached, typically by running the culture for more than five residence times [16].

- Step 7: Sample Collection and Quenching: Rapidly collect cells from the culture and quench metabolism instantly using cold methanol or other validated methods to snapshot the metabolic state.

- Step 8: Metabolite Extraction and Measurement: Extract intracellular metabolites. Analyze the extracts using GC-MS or LC-MS/MS to obtain the experimental Mass Distribution Vectors (MDVs) for key metabolites [16].

Data Integration and Validation Phase:

- Step 9: Flux Estimation: Input the experimentally measured MDVs into a 13C-MFA software tool (e.g., INCA, OpenFLUX) to find the flux distribution that best fits the data [16].

- Step 10: Hypothesis Testing: Compare the final estimated flux for your reaction of interest (

v_j) against the predefined threshold from your original hypothesis. The validity of the hypothesis is confirmed by the flux fit derived from the optimally designed experiment.

Constraint-Based Modeling and Isotopomer Analysis are foundational techniques in systems biology for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes. Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) utilizes genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to define all biochemical transformations within a cell, bounding possible metabolic states using stoichiometry, thermodynamics, and enzyme capacities [14] [18]. The feasible flux distributions form a convex polytope within the solution space [18]. When combined with 13C isotope tracing, this framework allows researchers to elucidate a quantitative map of metabolic flow, as the arrangement of labeled carbon atoms in metabolites (isotopomer distributions) is uniquely determined by the underlying fluxes [19] [20]. Monte Carlo sampling techniques are increasingly deployed to analyze these high-dimensional spaces, enabling robust flux estimation and optimal experimental design without prior knowledge of the true flux distribution [14]. This protocol details the application of Monte Carlo methods for 13C metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA).

Core Methodologies

Foundation of Constraint-Based Modeling

The first step in 13C-MFA is to define the system constraints using a genome-scale metabolic model. The steady-state mass balance for all metabolites is described by:

A'~eq~ · ν = b'~eq~ [18]

where A'~eq~ is the extended stoichiometric matrix, ν is the vector of metabolic reaction rates (fluxes), and b'~eq~ contains the time derivatives of metabolite concentrations (zero at steady-state). Fluxes are further constrained by linear inequalities:

A~in~ · ν ≤ b~in~

which incorporate physiological limitations such as nutrient uptake rates and enzyme capacities [18]. These constraints collectively define a convex flux polytope containing all feasible metabolic states [18].

Isotopomer Modeling and 13C Tracing

Isotopomers (isotopic isomers) are distinct forms of a metabolite that differ in the positional arrangement of 13C atoms [14]. When cells are fed a 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [U-13C]glucose), the chemical reactions of metabolism rearrange the carbon atoms, producing unique isotopomer patterns in downstream metabolites [19] [20]. The Isotopomer Distribution Vector (IDV) contains the fractional abundance of each isotopomer for a given metabolite pool [19] [14]. Experimentally, the labeling patterns are often measured via Mass Spectrometry (MS) as a Mass Distribution Vector (MDV), which represents the fractional abundances of different mass isotopomers (molecules with the same total number of 13C atoms) [14] [21]. The MDV is a linear transformation of the IDV [21]. The Elemental Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework is a computationally efficient method to simulate these labeling patterns by decomposing metabolites into unique subsets of atoms, which are the minimal units required to simulate the measured MS data [19] [21].

Integration via Monte Carlo Sampling

A powerful approach for flux elucidation involves sampling the flux polytope to generate a set of biochemically feasible flux distributions [14]. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm, specifically implementations like Coordinate Hit-and-Run with Rounding (CHRR), is used to draw a uniform sample of flux states from the high-dimensional polytope [18]. For each sampled flux vector v, the corresponding isotopomer distributions (IDVs) for target metabolites are calculated using the EMU framework [14] [21]. These simulated IDVs (or their MDV equivalents) are then compared against experimentally measured labeling data. Flux distributions that produce labeling patterns inconsistent with the experimental data can be statistically ruled out, thereby refining the solution space and identifying the fluxes that best describe the cellular metabolic state [14].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Steady-State 13C-MFA Experiments in Proliferating Mammalian Cells [20]

| Parameter | Typical Range | Unit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate (μ) | Varies | 1/h | Calculated from exponential increase in cell number. |

| Glucose Uptake | 100 – 400 | nmol/10^6^ cells/h | Negative value in flux calculations. |

| Lactate Secretion | 200 – 700 | nmol/10^6^ cells/h | Positive value in flux calculations. |

| Glutamine Uptake | 30 – 100 | nmol/10^6^ cells/h | Correct for spontaneous degradation in medium. |

| Other Amino Acids | 2 – 10 | nmol/10^6^ cells/h | Uptake or secretion. |

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of using Monte Carlo sampling for 13C-MFA.

Diagram 1: Monte Carlo Sampling Workflow for 13C-MFA. The process integrates network definition, constraint-based sampling, and experimental data to resolve metabolic fluxes.

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Monte Carlo Sampling for Flux Elucidation

This protocol describes how to use Monte Carlo sampling to determine metabolic fluxes from 13C labeling data in a mammalian cell system, such as a cancer cell line.

I. Pre-Experiment: Model and Tracer Design

- Network Reconstruction: Obtain a context-specific metabolic network reconstruction. For general purposes, a model including glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle, and key biosynthetic reactions is sufficient [14].

- Tracer Selection: For studying glutamine metabolism, [U-13C~5~]glutamine is a robust tracer to evaluate total contribution to the TCA cycle and lipogenesis. To specifically resolve reductive carboxylation, [1-13C] or [5-13C]glutamine are effective [22]. Computational design using EMU basis vectors can rationally identify optimal tracers [21].

- Polytope Definition: Formulate the flux polytope by defining the stoichiometric matrix A'~eq~ and constraint vectors b'~eq~, A~in~, and b~in~ based on measured external rates [18].

II. Cell Culture and Labeling Experiment

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells (e.g., A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells) at an appropriate density (e.g., 200,000 cells/well in a 6-well plate) in standard growth medium and allow to attach for at least 6 hours [22].

- Tracer Introduction: Replace the growth medium with a specialized medium containing the chosen 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., 4 mM [U-13C~5~]glutamine) and dialyzed FBS to minimize unlabeled nutrient interference [22].

- Harvesting: Incubate cells until both metabolic and isotopic steady state are achieved. For [U-13C~6~]glutamine, TCA cycle metabolites typically reach isotopic steady state within 3 hours during exponential growth. Quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites [22].

III. Data Generation and Flux Analysis

- Measure External Rates: Quantify cell growth and nutrient consumption/secretion rates using Eqs. 3-5 from Section 2.3. Correct glutamine uptake for spontaneous degradation [20].

- Acquire Labeling Data: Analyze metabolite extracts via GC-MS or LC-MS to obtain Mass Distribution Vectors (MDVs) for key metabolites such as TCA cycle intermediates and amino acids [14] [20].

- Perform Monte Carlo Sampling:

- Use the CHRR algorithm to generate a large set (e.g., >10,000) of uniformly sampled flux distributions from the pre-defined polytope [18].

- For each sampled flux vector v, simulate the corresponding MDVs for the measured metabolites using the EMU model [14] [21].

- Statistically compare the simulated MDVs against the experimental MS data. Flux distributions that yield simulated data significantly different from the measurements (e.g., based on a χ² test) are rejected [14].

- The remaining flux distributions define the feasible flux space, from which the most likely flux map and confidence intervals for each reaction flux are calculated [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA [22] [20]

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Carbon source for tracing metabolic pathways. | [U-13C~5~]Glutamine, [1,2-13C~2~]Glucose. Commercial suppliers provide various labeling patterns. |

| Isotope-Enabled Metabolic Model | Computational framework for simulating labeling and inferring fluxes. | EMU-based model in software like Metran or INCA [20] [21]. |

| Specialized Culture Media | Basal medium without components of interest to allow defined tracer introduction. | Glucose- and Glutamine-free DMEM [22]. |

| Dialyzed Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Serum supplement with low-molecular-weight molecules removed to prevent dilution of the tracer. | Typical molecular weight cut-off: 10,000 Da [22]. |

| Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Analytical instrument for measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MDVs) in extracted metabolites. | Workhorse technology for 13C-MFA [19] [20]. |

| Monte Carlo Sampling Software | Tools for uniformly sampling the flux solution space of genome-scale models. | Implementations of the CHRR algorithm [14] [18]. |

| Barium hydride (BaH2) | Barium hydride (BaH2), CAS:13477-09-3, MF:BaH2, MW:139.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Beryllium perchlorate | Beryllium perchlorate, CAS:13597-95-0, MF:Be(ClO4)2, MW:207.91 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The following diagram illustrates the core concept of the EMU framework used in simulating mass isotopomers.

Diagram 2: The EMU Framework for Simulating Mass Isotopomers. The EMU model decomposes metabolites into minimal atom groups to efficiently simulate the mass isotopomer distribution (MDV) resulting from a given flux map and labeled substrate.

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) using 13C isotope tracing is a powerful technique for quantifying reaction rates in living cells. A significant challenge in 13C-MFA is that the complete flux distribution of a metabolic network is often underdetermined by the experimental data. Monte Carlo sampling addresses this by generating a large set of biologically feasible flux distributions that are consistent with both the measured isotope labeling data and the stoichiometric constraints of the metabolic network [2]. Unlike methods that identify a single "best-fit" flux solution, Monte Carlo sampling explores the space of possible fluxes, allowing researchers to assess the reliability of flux estimates and identify which fluxes are well-determined by the data and which are not [2] [23]. This probabilistic approach is particularly valuable for designing optimal isotope tracing experiments in silico before conducting wet-lab experiments, which can be costly and time-consuming [2].

Key Concepts and Biological Hypotheses

From Sampled Flux Distributions to Testable Hypotheses

Interpreting the output of Monte Carlo sampling requires moving from a set of flux distributions to actionable biological insights. This is achieved by defining and testing specific experimental hypotheses [2]. A hypothesis is formally defined as a partition of the sampled set of flux distributions into distinct groups. Two primary classes of rational hypotheses are common:

- Flux Magnitude Hypotheses (hi-lo): This tests whether the flux through a specific reaction is above or below a biologically meaningful threshold. The solution space is partitioned into all points where the flux vj for reaction j is greater than a threshold versus all points where it is less [2]. A natural threshold is the median flux from the entire sample.

- Flux Ratio Hypotheses: This tests the relative activity of different pathways by determining if the ratio of two reaction fluxes, vi/vj, is above or below a defined threshold [2].

The power of a given 13C labeling experiment to answer a specific biological question can be evaluated by how well the isotopomer distributions simulated from one flux partition are distinguishable from those of the other partition [2].

Quantifying Hypothesis Resolution

The ability to distinguish between hypotheses is quantified using a scoring metric. A common heuristic is a Z-score-based metric, which measures the separation between the simulated measurement distributions (e.g., Mass Distribution Vectors - MDVs) arising from the two different flux partitions [2]. As illustrated in the table below, a higher score indicates that the experimental design (including the choice of labeled substrate) is better suited to resolve the biological question of interest.

Table 1: Types of Biological Hypotheses Tested with Sampled Flux Distributions

| Hypothesis Type | Biological Question | Formal Partition of Flux Space | Typical Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Magnitude (hi-lo) | Is the flux through reaction j high or low? | vj > threshold vs. vj < threshold | Median of all sampled vj values [2] |

| Flux Ratio | How does the activity of pathway A compare to pathway B? | vi/vj > threshold vs. vi/vj < threshold | Biologically relevant ratio (e.g., 1.0) |

Workflow for Interpretation and Analysis

A structured workflow is essential for transforming raw sampling outputs into robust biological conclusions. This process involves several key stages, from data preparation to final visualization.

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Before analysis, the quality of the sampled flux distributions must be assessed. This involves:

- Convergence Checking: Ensuring the Monte Carlo sampler has adequately explored the feasible flux space and is not stuck in a local region.

- Constraint Validation: Verifying that all sampled flux distributions obey the steady-state mass balance constraints (S ∙ v = 0) and any measured uptake/secretion rates [2].

- Outlier Identification: Detecting and removing any flux distributions that are statistical outliers or biochemically implausible.

Statistical Analysis and Uncertainty Quantification

A core advantage of Monte Carlo sampling is its inherent quantification of uncertainty. Key analyses include:

- Flux Confidence Intervals: Calculating credible intervals for each reaction flux from the sampled distributions. A narrow interval indicates a well-determined flux [23] [24].

- Correlation Analysis: Identifying pairs of fluxes that are highly correlated or anti-correlated across the samples. This reveals functional couplings between reactions that may not be adjacent in the metabolic network [25].

- Dimensionality Assessment: Using techniques like Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the simulated isotopomer data to determine the effective amount of independent information in a planned experiment. Studies have shown that the dimensionality can be less than anticipated, limiting the number of fluxes that can be resolved [2].

Advanced Bayesian Methods for Flux Inference

While traditional Monte Carlo sampling explores the feasible flux space, modern approaches are increasingly adopting a full Bayesian framework for flux inference [23] [24]. This paradigm shift offers several key advantages:

- Incorporation of Prior Knowledge: Experts' knowledge about likely flux ranges can be formally incorporated via prior distributions, leading to more robust and scientifically realistic parameter estimates [24].

- Unification of Model and Data Uncertainty: Bayesian methods naturally combine uncertainty from measurement noise with uncertainty about the correct model structure itself [23].

- Multi-Model Inference: Instead of relying on a single metabolic model, Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) can be used to average over multiple competing models, providing flux estimates that are robust to model selection uncertainty [23].

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional and Bayesian Approaches to 13C-MFA

| Feature | Traditional Monte Carlo Sampling | Bayesian MFA |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Output | Set of feasible flux distributions [2] | Posterior probability distribution of fluxes [23] [24] |

| Prior Knowledge | Incorporated as hard constraints (flux bounds) | Incorporated as soft constraints (prior distributions) |

| Model Uncertainty | Not typically addressed | Explicitly accounted for via Bayesian Model Averaging [23] |

| Handling of Complex Data | Can be challenging | More flexible; hierarchical models can integrate multi-omics data |

Visualization of High-Dimensional Flux Data

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting the high-dimensional output of flux sampling. Tools like Shu have been developed specifically to visualize distributions and multi-condition data on metabolic maps [26]. Key capabilities include:

- Distribution Mapping: Plotting histograms or kernel density curves directly on reaction edges to represent the full distribution of sampled fluxes, revealing multimodality or skewness that a single value would hide [26].

- Multi-Condition Comparison: Using colored "box points" stacked vertically next to reactions to display point estimates (e.g., median flux) across multiple experimental conditions in a single map [26].

- Interactive Exploration: Allowing users to adjust the position and scale of distribution axes for complex maps, and to save these adjustments for publication-ready figures [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of Monte Carlo sampling for 13C-MFA requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Item | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Specifically labeled nutrients (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine) to trace metabolic pathways. | Tracing glycolysis with [1-13C]glucose or TCA cycle with uniform labels [2] [3]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemicals (e.g., MSTFA) for preparing metabolites for GC-MS analysis, enabling separation of sugar phosphates [27]. | Analysis of central carbon metabolites like glucose-6-phosphate or ribose-5-phosphate [27]. |

| Internal Standards | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards for quantitative mass spectrometry. | Correcting for instrument variability and ensuring quantitative accuracy [27]. |

| Cell/Tissue Culture Media | Chemically defined media for controlled tracer experiments. | Ex vivo culture of human liver tissue slices for metabolic phenotyping [3]. |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Software (COBRA) | Computational platform for simulating metabolic networks and sampling flux distributions [2]. | Generating feasible flux spaces for E. coli and human metabolic models [2] [25]. |

| Visualization Tools (Shu, Escher) | Software for creating and overlaying data on metabolic maps [26]. | Visualizing flux distributions and their uncertainties on a pathway map [26]. |

| 1-(4-(Hydroxyamino)phenyl)ethanone | 1-(4-(Hydroxyamino)phenyl)ethanone, CAS:10517-47-2, MF:C8H9NO2, MW:151.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dioctadecyl phthalate | Dioctadecyl phthalate, CAS:14117-96-5, MF:C44H78O4, MW:671.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: From Tissue to Insight in Human Liver Metabolism

The following detailed protocol, adapted from a study on global 13C tracing in intact human liver tissue, provides a real-world example of how these principles are applied [3].

Sample Preparation and Culture

- Tissue Acquisition: Obtain normal human liver tissue from surgical resections (e.g., from patients undergoing liver tumor resection). Place tissue in cold preservation buffer immediately after resection.

- Tissue Sectioning: Section the liver tissue into 150–250 μm slices using a vibratome or tissue chopper. This thickness ensures adequate oxygenation while preserving tissue architecture.

- Ex Vivo Culture: Culture liver slices on membrane inserts in a medium designed to approximate nutrient levels in fasted-state human plasma. Maintain cultures at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂. Culture duration can be up to 24 hours.

13C Isotope Tracing Experiment

- Tracer Introduction: Replace the culture medium with an identical medium except that it contains a fully 13C-labeled substrate. For a comprehensive analysis, use a medium where all 20 amino acids and glucose are uniformly labeled with 13C ([U-13C]).

- Time-Course Sampling: Harvest tissue and collect spent media at multiple time points (e.g., 2 h and 24 h) after introducing the tracer. This allows observation of the dynamics of 13C incorporation.

Metabolite Extraction and Analysis

- Metabolite Extraction: For tissue samples, use a methanol:water:chloroform extraction protocol to quench metabolism and extract polar metabolites.

- LC-MS Analysis: Analyze the extracted polar metabolites using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). A high-resolution mass spectrometer is recommended for non-targeted analysis of 13C isotopologues.

Data Processing and Flux Sampling

- Isotopologue Data Processing: Extract mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) from the LC-MS raw data. Correct the raw MIDs for natural abundance of heavy isotopes (13C, 29Si, 30Si) introduced from the derivatization process or native atoms [27].

- Flux Space Definition: Use a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., Recon for human metabolism) constrained with measured uptake and secretion rates to define the space of feasible flux distributions.

- Monte Carlo Sampling: Employ a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm to sample thousands of flux distributions uniformly from the feasible space [2] [24].

Hypothesis Testing and Interpretation

- Define Objective: Formulate a specific question, such as "Is gluconeogenic flux in this human liver sample above a clinically relevant threshold?"

- Partition and Score: Partition the sampled flux distributions based on the gluconeogenic flux threshold. Calculate a distinguishability score (e.g., Z-score) to evaluate how well the simulated 13C data from the high and low flux groups can be told apart.

- Validate with Physiology: Correlate the flux estimates with donor physiology. For example, the ex vivo glucose production flux of liver slices can be correlated with the plasma glucose level of the donor to ensure the metabolic phenotype is retained [3].

Implementing Monte Carlo Methods: From Experimental Design to Practical Application

Step-by-Step Workflow for a Monte Carlo-Based 13C-MFA Study

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a powerful model-based technique for the quantitative estimation of intracellular metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) in living cells [28]. It is considered the gold standard for flux quantification and has become an indispensable tool in metabolic engineering, systems biology, and biomedical research [29] [30]. The technique leverages data from isotope labeling experiments (ILEs), where cells are fed with 13C-labeled substrates, and the resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites are measured [28].

The Monte Carlo method plays a crucial role in 13C-MFA for robust statistical analysis [30]. It is primarily used for precisely determining confidence intervals of estimated fluxes, providing a more reliable uncertainty quantification compared to linear approximation methods [30] [31]. This approach involves generating numerous flux datasets by random sampling, allowing for comprehensive propagation of measurement errors and resulting in statistically sound flux resolution estimates [32] [30].

This protocol details a comprehensive workflow for conducting a Monte Carlo-based 13C-MFA study, providing researchers with a structured framework from experimental design to flux validation.

Experimental Design and Tracer Selection

Robust Experimental Design (R-ED) Workflow

The first critical step involves designing informative labeling experiments. When prior knowledge about the intracellular fluxes is limited or uncertain, a Robust Experimental Design (R-ED) approach is recommended [33]. This workflow uses flux space sampling to compute design criteria over a wide range of possible flux values, immunizing the tracer design against uncertainties in initial flux "guesstimates" [33].

The following diagram illustrates the R-ED workflow for selecting optimal tracers when prior flux knowledge is uncertain:

Tracer Selection Strategies

The choice of 13C-labeled tracer(s) significantly impacts the information content of the experiment [33]. The following table summarizes key considerations for tracer selection:

Table 1: Tracer Selection Strategies for 13C-MFA

| Strategy | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Single Tracer | Using one specifically labeled substrate (e.g., [1,2-13C] glucose) | Preliminary studies, well-characterized systems [16] |

| Parallel Labeling Experiments (PLE) | Multiple tracers applied to parallel cultures from the same seed culture | Maximizing flux resolution, comprehensive flux mapping [30] |

| Tracer Mixtures | Using mixtures of isotopomers of the same compound | Resolving specific pathway activities [28] |

| COMPLETE-MFA | Employing all six singly labeled glucose tracers | Highest flux resolution and accuracy [30] |

For microbial systems, commonly used carbon sources include glucose, acetate, and glycerol [16]. The selection should be based on the organism's metabolic capabilities and the pathways of interest. The R-ED workflow enables exploration of suitable tracer mixtures with flexibility to trade off information content and cost metrics [33].

Sample Preparation and Steady-State Cultivation

Establishing Metabolic and Isotopic Steady State

A critical requirement for standard 13C-MFA is achieving both metabolic and isotopic steady state [16]. The following protocol ensures proper steady-state conditions:

- Culture Conditions: Maintain constant temperature, pH, and nutrient availability throughout the labeling experiment [16].

- Labeling Duration: Extend the incubation time to at least five residence times to ensure the system reaches isotopic steady state [16].

- Growth Monitoring: For batch cultures, maintain cells in exponential growth phase where metabolic fluxes remain constant [16].

- Tracer Addition: Add 13C-labeled substrates at the beginning of the experiment or during early exponential growth phase.

- Sampling Point: Harvest cells during mid-exponential phase when both biomass and labeling patterns are stable.

Sample Collection and Quenching

Proper sampling techniques are essential for obtaining accurate intracellular metabolite data:

- Rapid Sampling: Use rapid sampling techniques (e.g., vacuum filtration or fast centrifugation) to immediately halt metabolic activity.

- Metabolite Quenching: Employ cold methanol quenching (-40°C) to instantly freeze metabolic reactions.

- Cell Harvesting: Collect sufficient biomass for subsequent analysis (typically 5-10 mg dry cell weight for GC-MS analysis).

- Sample Storage: Store samples at -80°C until metabolite extraction to prevent degradation.

Isotopic Labeling Measurement

Metabolite Extraction and Derivatization

Prepare samples for mass spectrometric analysis through appropriate extraction and derivatization:

- Metabolite Extraction: Use cold methanol-water-chloroform extraction for intracellular metabolites [16].

- Polar Phase Collection: Recover polar metabolites from the aqueous phase for central metabolic intermediates.

- Derivatization: For GC-MS analysis, derivative metabolites to increase volatility:

- Amino Acids: Use MTBSTFA or TBDMS derivatives for proteinogenic amino acids [28].

- Organic Acids: Use methoxyamine and MSTFA for TCA cycle intermediates.

- Quality Control: Include process blanks and pooled quality control samples.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Several mass spectrometry techniques can be employed for isotopic labeling measurement:

Table 2: Mass Spectrometry Techniques for Isotopic Labeling Analysis

| Technique | Measured Data | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) | Central carbon metabolism intermediates, amino acids | High sensitivity, routine application [16] |

| LC-MS/MS | Mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) | Complex metabolite spectra, non-volatile compounds | Excellent separation, no derivatization needed [16] |

| NMR | Positional isotopomer information | Full positional labeling information, pathway mapping | Structural information, non-destructive [28] |

For GC-MS analysis, measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode for optimal sensitivity. Collect raw isotopomer data as uncorrected mass isotopomer distributions [31].

Metabolic Network Modeling and Flux Estimation

Metabolic Network Reconstruction

Construct a stoichiometric model of the central carbon metabolism:

- Network Definition: Include key pathways: glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, TCA cycle, anaplerotic reactions, and lumped biosynthetic reactions [30].

- Atom Transitions: Define carbon atom transitions for each reaction based on known biochemistry [28].

- Balanced Metabolites: Identify metabolites at pseudo-steady state (balanced pools).

- Free Flux Parameters: Define independent free fluxes that determine the entire flux distribution.

- Model Formulation: Use the universal flux modeling language FluxML for model specification [33].

Flux Estimation Procedure

Estimate metabolic fluxes through iterative model fitting:

- Initialization: Start with initial flux values based on physiological constraints.

- Simulation: Simulate the expected labeling patterns using the current flux values.

- Comparison: Calculate the difference between simulated and measured labeling patterns.

- Optimization: Adjust flux values to minimize the residual sum of squares (RSS) between experimental and simulated data [28].

- Convergence Check: Repeat steps 2-4 until the optimization converges to a minimal RSS.

The flux estimation can be formalized as the optimization problem [28]:

Where v represents metabolic fluxes, S is the stoichiometric matrix, x is the simulated labeling, and xM is the measured labeling.

Monte Carlo Analysis for Flux Uncertainty

Monte Carlo Workflow for Confidence Intervals

The Monte Carlo method provides robust confidence intervals for estimated fluxes [30]. The following diagram illustrates this process:

Implementation Protocol

Implement the Monte Carlo analysis with the following steps:

- Error Model Definition: Define the measurement error covariance matrix based on experimental replicates [34].

- Synthetic Dataset Generation: Create multiple synthetic datasets by adding random noise to the original measurements according to the error model.

- Parallel Flux Estimation: Estimate fluxes for each synthetic dataset using the same optimization procedure.

- Solution Collection: Collect all flux solutions from converged estimations.

- Distribution Analysis: Build probability distributions for each flux from the solution ensemble.

- Confidence Interval Calculation: Determine confidence intervals (typically 95%) from the flux distributions.

This approach is particularly valuable as it does not rely on linear approximations of the parameter space around the optimal flux values, providing more reliable uncertainty estimates, especially for non-linear models [30].

Statistical Validation and Model Selection

Goodness-of-Fit Evaluation

Assess the quality of the flux estimation using statistical tests:

- Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) Evaluation: Calculate the minimized RSS and compare it to a χ² distribution with degrees of freedom (number of data points - number of parameters) [16].

- χ²-test: Perform a χ²-test for goodness-of-fit to evaluate model adequacy [34].

- Residual Analysis: Examine residuals for systematic patterns that might indicate model misspecification.

Validation-Based Model Selection

To address model selection uncertainty, employ validation-based approaches [34]:

- Independent Validation Data: Use independent labeling data not used in model fitting.

- Model Prediction Accuracy: Evaluate how well each candidate model predicts the validation data.

- Model Selection: Choose the model with the best predictive performance.

- Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA): As an advanced alternative, use BMA for multi-model inference, which assigns probabilities to different model structures and provides flux estimates averaged over multiple models [23].

This approach is more robust than traditional methods that rely solely on χ²-tests, especially when measurement errors are uncertain [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential materials and reagents required for a complete 13C-MFA study:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 13C-MFA Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | [1,2-13C] glucose, [U-13C] glucose, [1-13C] glutamine | Carbon source for isotope labeling experiments | Purity > 99%; cost ranges from $100-600/g [16] |

| Cell Culture Media | Defined minimal media, isotope-labeled media formulations | Providing nutritional environment with labeled substrates | Must support metabolic steady-state |

| Derivatization Reagents | MTBSTFA, TBDMS, MSTFA, Methoxyamine | Volatilization of metabolites for GC-MS analysis | Critical for accurate MS detection [16] |

| Internal Standards | 13C-labeled amino acid mixes, U-13C cell extracts | Correction for natural isotope abundance, quantification | Essential for data normalization |

| Extraction Solvents | Methanol, chloroform, water (cold mixtures) | Metabolite extraction and quenching of metabolic activity | Maintain cold chain during extraction |

| Software Tools | 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX2, mfapy, INCA | Flux estimation, statistical analysis, Monte Carlo simulations | Open-source options available [32] [35] [30] |

This protocol provides a comprehensive step-by-step workflow for conducting Monte Carlo-based 13C-MFA studies. The integration of robust experimental design, careful laboratory execution, and advanced computational analysis with Monte Carlo methods ensures reliable quantification of intracellular metabolic fluxes with statistically validated confidence intervals. By following this structured approach, researchers can obtain high-quality flux maps that provide deep insights into cellular physiology, supporting applications in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and biomedical research.

Selecting an optimal (^{13}\text{C})-labeled substrate is a critical step in designing isotope tracing experiments, directly influencing the precision and scope of metabolic flux analysis (MFA). A well-chosen tracer enhances the ability to resolve fluxes through specific pathways of interest, thereby maximizing the information gained from often costly and time-consuming experiments. Within the broader context of Monte Carlo sampling for (^{13}\text{C}) isotope tracing research, computational frameworks enable the a priori evaluation of different labeling patterns, predicting their efficacy in constraining metabolic fluxes without requiring a priori assumptions about the underlying flux distribution [2]. This protocol details the application of Monte Carlo sampling methods to guide the rational selection of (^{13}\text{C})-labeled substrates, providing methodologies and tools for researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development.

The core challenge in (^{13}\text{C})-MFA is solving the inverse problem: determining the intracellular flux distribution that best fits experimentally measured mass isotopomer distributions. The choice of substrate label significantly impacts the conditioning of this problem. As highlighted in a foundational study, the dimensionality of data obtained from (^{13}\text{C}) experiments can be considerably less than anticipated, with high redundancy in measurements limiting the information obtained per experiment [2]. By employing computational design, researchers can identify labeling patterns that maximize the information content for their specific experimental objectives, such as elucidating fluxes in particular pathways like the TCA cycle or pentose phosphate pathway.

This application note integrates the latest software tools and experimental findings to create a structured guide for tracer selection. We present a methodology centered on Monte Carlo sampling to navigate the complex space of feasible metabolic states and evaluate the resolving power of different tracer experiments. The protocols are supplemented with specific reagent solutions, quantitative data tables, and visual workflows to facilitate implementation.

Theoretical Foundation: Monte Carlo Sampling for Tracer Evaluation

Monte Carlo sampling provides a powerful framework for assessing the potential of different (^{13}\text{C})-labeled substrates to determine metabolic fluxes without prior knowledge of the true intracellular flux state. The method leverages constraint-based metabolic models to generate a uniform spread of thermodynamically and stoichiometrically feasible flux distributions across the network [2].

Core Principle and Workflow

The fundamental principle involves simulating the (^{13}\text{C}) labeling patterns (Isotopomer Distribution Vectors, or IDVs) that would result from each sampled flux distribution for a given substrate labeling pattern. By analyzing the simulated data, researchers can score how effectively a particular tracer can distinguish between alternative flux states for a reaction or pathway of interest. An effective tracer produces distinct, separable labeling distributions for different flux states, whereas a poor tracer results in overlapping distributions that cannot be reliably distinguished [2].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying Monte Carlo sampling to the problem of tracer selection:

Formulating Experimental Hypotheses

A key advantage of this approach is its flexibility to test specific experimental hypotheses. Common hypotheses involve partitioning the sampled flux distributions to evaluate a tracer's ability to differentiate between metabolic states. Two rational hypotheses are [2]:

- High-Low Flux (hi-lo): The solution space is partitioned into flux distributions where the flux through a specific reaction

vjis above a defined threshold versus those where it is below. The threshold is often set to the median flux value for that reaction across all samples. - Flux Ratios: The partition is based on the ratio of two reaction fluxes,

vi/vj, being above or below a threshold. This is useful for analyzing pathway splits, such as the flux into the TCA cycle versus the pentose phosphate pathway.

The quantitative evaluation of a tracer's performance for a given hypothesis is typically done using a Z-score heuristic. This metric assesses the distinguishability between the isotopomer distributions emerging from the two partitions of the hypothesis. A higher Z-score indicates greater separation and, therefore, a better tracer for that specific experimental objective [2].

Computational Protocol:In SilicoTester Selection

This protocol details the steps for using Monte Carlo sampling to identify the optimal (^{13}\text{C})-labeled substrate.

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Tracer Design

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | Provides the stoichiometric framework and carbon atom mappings necessary for simulating isotope labeling. | Use organism-specific reconstructions (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli, RECON3D for human metabolism). |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Software | Platform for performing Monte Carlo sampling of the flux solution space. | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) [2] or cobrapy (Python). |

| (^{13}\text{C})-MFA Simulation Software | Simulates isotopomer or mass isotopomer distributions from flux distributions and substrate labels. | 13CFLUX(v3) [1], INCA. |

| Candidate (^{13}\text{C})-Substrates | The labeled compounds to be evaluated in silico. | Commercially available tracers like [1-(^{13}\text{C})]Glucose, [U-(^{13}\text{C})]Glucose, or [1,2-(^{13}\text{C})]Glucose. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Model Preparation: Begin with a high-quality, genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. For efficiency, the model can be reduced by removing blocked reactions and grouping linear biosynthetic pathways, as done in the expanded E. coli isotopomer model comprising 313 irreversible reactions [2].

- Define Constraints: Apply appropriate physiological constraints to the model, such as measured substrate uptake rates, specific growth rates, and byproduct secretion rates. These constraints define the convex solution space of feasible flux distributions.

- Monte Carlo Sampling: Use a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm (e.g., the

sampleCbModelfunction in the COBRA Toolbox) to generate a large set (e.g., thousands) of flux distributions that are uniformly spread across the constrained solution space [2]. - Specify Experimental Objective: Formally define the hypothesis to be tested. For example: "Determine the optimal tracer for resolving whether the flux through phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) is above 50% of the glucose uptake rate."

- Select Candidate Tracers: Compile a list of (^{13}\text{C})-labeled substrates for evaluation. This list should include both commonly used tracers and more complex patterns that may be synthetically available.

- Simulate Labeling Data: For each candidate tracer and each sampled flux distribution, simulate the corresponding isotopomer distribution vector (IDV) or mass distribution vector (MDV) for measurable metabolites using a (^{13}\text{C})-MFA simulation tool.

- Partition and Score: For the target reaction or ratio, partition the sampled flux distributions according to the defined hypothesis. For each partition, analyze the pooled simulated MDVs and calculate a Z-score to quantify the separation between the two groups for each candidate tracer.

- Identify Optimal Tracer: Rank the candidate tracers based on their Z-scores. The label yielding the highest score is predicted to be the most powerful for the stated experimental objective.

Experimental Validation and Practical Considerations

While computational design is powerful, its predictions must be grounded in practical experimental realities. Recent studies provide critical parameters for optimizing in vivo and ex vivo tracing experiments.

OptimizingIn VivoTracer Delivery

A 2025 study on TCA cycle labeling in mouse models offers specific, validated guidelines for bolus-based labeling experiments [36]. The key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Optimal Parameters for In Vivo Tracer Administration in Mice [36]

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Experimental Rationale / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor | ¹³C-Glucose | Outperformed ¹³C-lactate and ¹³C-pyruvate in TCA cycle label incorporation. |

| Dosage | 4 mg/g (body weight) | Larger dosing provided better labeling with minimal impact on basal metabolism. |

| Route | Intraperitoneal (IP) Injection | Superior label incorporation compared to oral administration. |

| Incorporation Time | 90 minutes | Waiting period after administration provided the best labeling. |

| Fasting | Organ-Dependent | A 3h fast improved labeling in most organs, but reduced labeling in the heart. |

Emerging Tools and Model Systems

The field is rapidly advancing with new software and experimental models that enhance tracer design and flux analysis.

- High-Performance Software: Third-generation simulation engines like 13CFLUX(v3) integrate high-performance C++ backends with Python interfaces, offering substantial performance gains for both isotopically stationary and nonstationary MFA [1]. This allows for more rapid and complex in silico tester evaluations.

- Advanced Algorithm: For dynamic flux analysis under non-stationary conditions, Stochastic Simulation Algorithms (SSA) provide an alternative to deterministic methods. SSA computes the temporal evolution of isotopomer concentrations, with computational time that does not scale with the number of isotopomers, making it efficient for complex networks [37].

- Human-Relevant Models: Global (^{13}\text{C}) tracing in intact human liver tissue cultured ex vivo has been demonstrated as a powerful model that retains donor-specific metabolic phenotypes. This system allows for deep, resolutive measurement of human liver metabolism in an experimentally tractable setup, bridging the gap between animal models and human physiology [3].

Integrated Workflow from Computation to Experiment

The following diagram synthesizes the computational and experimental protocols into a single, integrated workflow for designing and executing an optimal tracer experiment.