Native Pathway Engineering: Foundational Strategies and Cutting-Edge Tools for Advanced Bioproduction

This article provides a comprehensive overview of native pathway engineering strategies, a cornerstone of modern metabolic engineering for developing microbial cell factories.

Native Pathway Engineering: Foundational Strategies and Cutting-Edge Tools for Advanced Bioproduction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of native pathway engineering strategies, a cornerstone of modern metabolic engineering for developing microbial cell factories. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the evolution from rational design to the current third wave integrating synthetic biology and artificial intelligence. The content systematically covers foundational principles, advanced methodological tools like AI and computational algorithms, practical approaches for troubleshooting and optimizing pathway bottlenecks, and frameworks for validating and comparing engineered systems. By synthesizing the latest advancements, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging pathway engineering to efficiently produce high-value chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and sustainable materials.

The Evolution of Pathway Engineering: From Rational Design to Synthetic Biology

Defining Native Pathway Engineering and Its Role in Sustainable Bioproduction

Native pathway engineering is a specialized discipline within metabolic engineering that focuses on the directed modulation of a host organism's existing metabolic pathways to enhance the production of specific metabolites or to impart new cellular properties [1]. Unlike approaches that rely solely on introducing entirely foreign genetic material, this strategy builds upon the innate biochemical machinery of the cell, optimizing and redirecting native metabolic fluxes toward desired goals. In the context of a burgeoning circular bioeconomy, native pathway engineering provides a powerful framework for developing sustainable bioprocesses. It enables the conversion of low-cost, renewable feedstocks—including one-carbon (C1) compounds like CO₂ and waste products—into high-value chemicals, materials, and fuels, thereby reducing dependence on fossil resources [2] [3].

The core objective is to overcome the natural regulatory constraints and inefficiencies of microbial metabolism. While native pathways are the result of natural evolution for fitness and survival, they are not optimized for industrial-scale metabolite overproduction. Pathway engineering employs a rational, design-driven approach to remove these bottlenecks, rewire regulatory networks, and enhance pathway efficiency, ultimately transforming microorganisms into efficient microbial cell factories [1].

Core Principles and Methodologies

The engineering of native pathways is guided by several key principles and is executed through a suite of sophisticated molecular biology and computational tools.

Key Engineering Strategies

- Elimination of Competing Pathways: Strategic deletion of genes that divert metabolic intermediates away from the target product, thereby concentrating carbon flux.

- Overexpression of Rate-Limiting Enzymes: Identification and amplification of bottleneck steps in a pathway, such as the commitment step, to increase overall flux.

- Dynamic Metabolic Control: Implementation of genetically encoded circuits that allow the cell to autonomously regulate pathway expression in response to metabolite levels, balancing the trade-off between cell growth and product formation [4].

- Cofactor Balancing: Manipulation of intracellular pools of energy carriers (e.g., ATP, NADPH) to ensure adequate supply for biosynthetic reactions.

- Extension of Substrate Range: Modification of native pathways to assimilate non-native, often more sustainable, feedstocks such as C1 compounds [2].

Enabling Tools and Workflows

The field is increasingly driven by data-intensive, iterative workflows. The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is central to this process [3]. In the Design phase, systems biology tools and multi-omics datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) are leveraged to reconstruct metabolic networks and identify potential engineering targets. Build involves the genetic modification of the host organism using techniques from synthetic biology. The engineered strains are then Tested in bioreactors, and high-throughput analytics generate performance data. Finally, in the Learn phase, machine learning (ML) and computational modeling analyze this data to inform the next, more effective design cycle, progressively optimizing the system [3].

Table 1: Key Computational and Experimental Tools in Pathway Engineering

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Pathway Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Omics Technologies | Genomics, Transcriptomics | Identifies native genes, gene clusters, and expression patterns for pathway elucidation [5] [3]. |

| Computational Modeling | Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Predicts theoretical yields, simulates flux distributions, and identifies gene knockout targets [2]. |

| Machine Learning | Deep Learning, Support Vector Machines | Extracts features from complex omics data; predicts enzyme function and optimal pathway configurations [5] [3]. |

| Dynamic Regulators | FapR Transcription Factor | Senses malonyl-CoA levels and dynamically regulates pathway gene expression to optimize flux [4]. |

Application in Sustainable Bioproduction: Key Case Studies

Engineering C1 Metabolism for a Carbon-Negative Future

One-carbon (C1) substrates like carbon dioxide (COâ‚‚), methane (CHâ‚„), and methanol are attractive feedstocks for sustainable bioproduction. Native C1-trophic bacteria possess specialized pathways for assimilating these gases. Quantitative comparisons of the theoretical yields for various products from different C1 feedstocks and pathways guide the rational selection of the optimal host-product pairing [2]. For instance, native pathways in acetogenic bacteria can be engineered to improve yields, often through cofactor engineering. Furthermore, the construction of sequential microbial cultures that combine diverse native metabolisms is an emerging strategy to achieve high production yields from C1 gases, showcasing the power of engineering at a community level [2].

Dynamic Regulation for Fatty Acid-Derived Biofuel Production

A paradigm-shifting application of native pathway engineering is the implementation of dynamic metabolic control. In one seminal study, the native fatty acid biosynthesis pathway in E. coli was rewired using a synthetic malonyl-CoA switch [4]. Malonyl-CoA is a critical precursor for fatty acids and a hub for various biosynthetic reactions. The researchers used the transcription factor FapR from Bacillus subtilis, which natively senses malonyl-CoA and regulates lipid metabolism.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sensor Characterization: Two malonyl-CoA sensor constructs were built and characterized: a T7-based sensor where FapR acts as a repressor, and a pGAP-based sensor where FapR was found to act as an activator.

- Promoter Tuning: The transcriptional activity of the pGAP-based sensor was finely tuned by incorporating different numbers of FapR-binding sites (fapO), creating a library of sensors with varying expression dynamics and malonyl-CoA sensitivity.

- Circuit Implementation: The optimized sensor systems were integrated to dynamically control the expression of both the upstream supply pathway (generating malonyl-CoA) and the downstream sink pathway (consuming malonyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis).

- Performance Analysis: The strain with the dynamic control circuit was compared in bioreactor studies to wild-type and statically engineered strains. Metrics included fatty acid titer, yield, and intracellular malonyl-CoA concentration over time.

Results: The engineered dynamic circuit created an oscillatory pattern of malonyl-CoA, allowing the cell to automatically balance metabolic resources between growth and production. This resulted in a 15.7-fold improvement in FA titer compared to the wild-type strain, dramatically outperforming static overexpression approaches [4].

Tailored Biopolymer Production inPseudomonas putida

Pseudomonas putida has been engineered as a robust chassis for producing tailored polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), a class of biodegradable bioplastics [6]. This work involves the intricate manipulation of the native PHA metabolic and regulatory circuits. By engineering these native pathways, researchers have enabled the biosynthesis of novel polymers with customized properties, including the incorporation of non-biological chemical elements into the PHA structure. This expands the potential of PHAs to disrupt market segments traditionally dominated by petroleum-based plastics [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Protocols

Successful native pathway engineering relies on a toolkit of specialized reagents and well-defined protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| FapR Transcriptional Regulator | Malonyl-CoA biosensor; enables dynamic regulation of pathway genes. | Used to build a metabolic switch for fatty acid production in E. coli [4]. |

| Specialized Host Strains | Engineered microbial chassis with optimized metabolism for production. | Pseudomonas putida strains engineered for polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production [6]. |

| Plasmid Vectors with Tunable Promoters | Vectors (e.g., pBAD, pTrc) allowing controlled expression of pathway genes. | Used to balance expression of enzymes in the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway [4]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Tool for biophysically characterizing protein-DNA (e.g., FapR-fapO) interactions. | Used to validate FapR binding affinity to engineered promoter sequences [4]. |

General Workflow for a Dynamic Metabolic Engineering Project

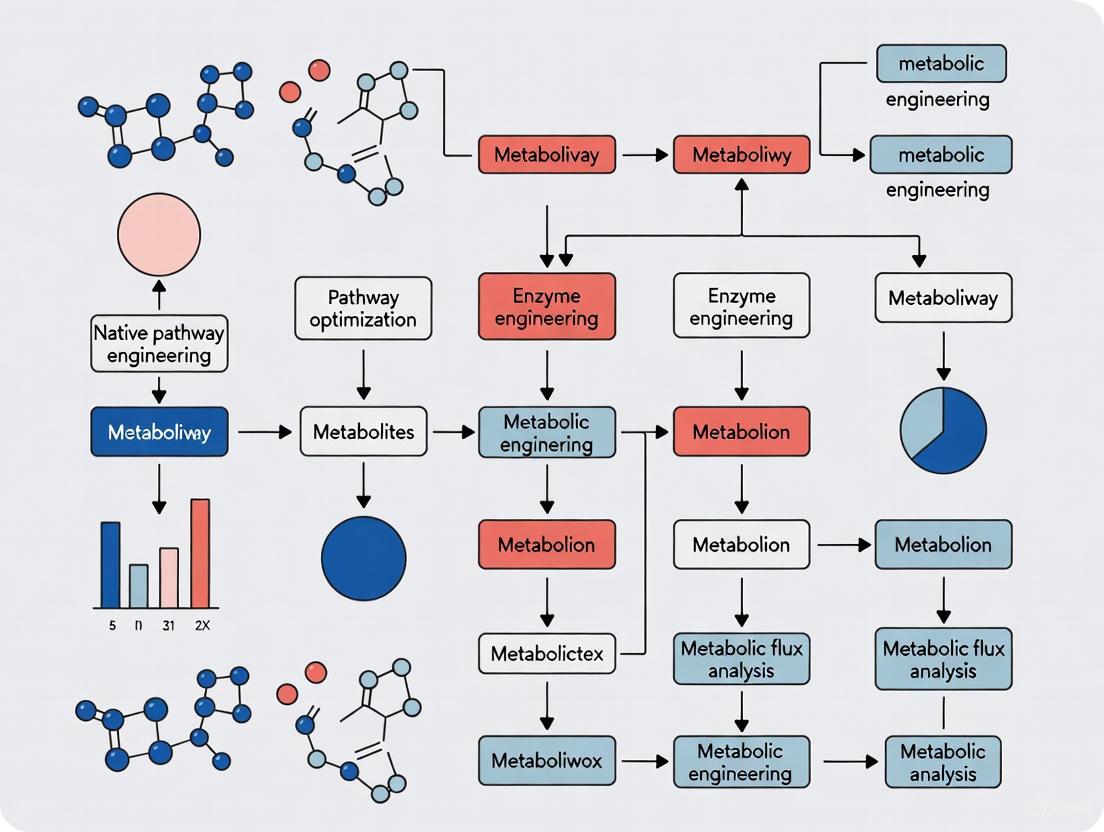

The following diagram summarizes the core experimental workflow for implementing dynamic metabolic control, as exemplified by the fatty acid production case study [4].

Molecular Mechanism of a Malonyl-CoA Sensor

The function of a key reagent, the FapR-based biosensor, is detailed in the following molecular-level diagram.

Quantitative Analysis of Pathway Performance

Rigorous quantitative analysis is indispensable for evaluating the success of pathway engineering efforts and for guiding the initial design.

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes of Native Pathway Engineering Strategies

| Engineering Strategy | Product | Host Organism | Reported Improvement | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Control of Malonyl-CoA | Fatty Acids | Escherichia coli | 15.7-fold increase | Final FA titer [4] |

| Theoretical Yield Calculation | Various from C1 gases | Native C1-trophs | N/A | Guides organism, product, and substrate selection [2] |

| Cofactor Engineering | Biochemicals | Acetogens | Significant yield improvement predicted | Maximal theoretical yield [2] |

Native pathway engineering has established itself as a cornerstone of sustainable bioproduction. By moving beyond static genetic modifications to embrace dynamic control, as exemplified by metabolite-responsive circuits, the field has achieved unprecedented gains in the titer, yield, and productivity of target compounds. The integration of systems biology, sophisticated computational tools, and machine learning into the DBTL cycle is pushing the boundaries of what is possible, enabling the rational design of complex microbial cell factories.

Future advancements will hinge on several key frontiers. The engineering of metabolons—supramolecular complexes of sequential metabolic enzymes—promises to dramatically increase pathway efficiency through substrate channeling [5]. Further, the full integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning will accelerate the discovery of novel pathways and the prediction of optimal genetic designs, moving the field further from trial-and-error and toward predictable engineering [5] [3]. Finally, the expansion of biosynthetic capabilities to include non-biological chemistries and the engineering of synthetic microbial consortia will unlock new pathways for converting a wider array of waste and C1 feedstocks into valuable, sustainable products, solidifying the role of biotechnology in a circular economy.

The field of biological engineering has undergone a profound transformation, evolving through three distinct waves of innovation. This progression began with rational engineering, focused on targeted, single-gene modifications, and advanced toward systems biology, which incorporated network-wide analyses to understand complex interactions. The field is now firmly in the era of synthetic biology-driven engineering, which combines deep computational design with advanced genetic tools to construct entirely new biological systems. This evolution is particularly evident in the domain of native pathway engineering—the strategic rewiring of a host organism's inherent metabolic networks to enhance production of valuable compounds. This whitepaper examines these three waves, detailing their core principles, methodological tools, and impacts, with a specific focus on strategies for engineering native pathways for applications in pharmaceutical and chemical production.

The First Wave: Rational Engineering

The initial wave of rational engineering was characterized by a reductionist approach. Engineers focused on linear pathways and individual rate-limiting steps, using direct genetic modifications to manipulate host metabolism.

Core Principles and Strategies

Rational engineering operates on the principle that a pathway's flux can be predictably enhanced by alleviating a single primary bottleneck. The key strategies include:

- Overexpression of Rate-Limiting Enzymes: Identifying and amplifying the expression of the enzyme with the slowest kinetic activity in a target pathway.

- Knock-out of Competing Pathways: Disrupting genes that divert key intermediates away from the desired product.

- Feedback Resistance Engineering: Introducing mutations to allosteric regulation sites to decouple product formation from native metabolic control mechanisms.

Experimental Protocol: A Classic Rational Engineering Workflow

A typical protocol for a rational engineering approach to enhance metabolite production is as follows [7]:

- Identify Target Gene: Use literature mining and preliminary kinetic data to hypothesize the rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway.

- Design Genetic Construct: Clone the gene encoding the target enzyme into a plasmid under the control of a strong, constitutive promoter.

- Host Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into the microbial or plant host.

- Screening and Validation: Screen transformants for increased product titer using methods like LC-MS or GC-MS.

- Fermentation and Analysis: Cultivate the best-performing strain and quantify the final product yield.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Rational Engineering

| Reagent Type | Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vector | High-copy-number plasmid with strong promoter (e.g., T7, pGAP) | Drives high-level expression of the target gene. |

| Cloning Kit | Gibson Assembly or Restriction Enzyme-based kit | Facilitates the assembly of the genetic construct. |

| Transformation Reagent | Chemical competence kits or Electroporation cuvettes | Enables introduction of DNA into the host organism. |

| Selection Agent | Antibiotic (e.g., Ampicillin, Kanamycin) | Selects for host cells that have successfully incorporated the plasmid. |

| Analytical Standard | Pure target metabolite | Enables accurate quantification of product titer via LC-MS/GC-MS calibration. |

The Second Wave: Systems Biology

The second wave introduced a holistic, network-based perspective. Systems biology acknowledges that metabolic pathways are interconnected networks, and that engineering requires an understanding of these system-wide interactions to avoid unforeseen bottlenecks and compensatory mechanisms [8].

Core Principles and Omics Technologies

This approach relies on global data acquisition and computational modeling to guide engineering efforts.

- Principle of Network Analysis: Understanding that perturbation at one node can have ripple effects throughout the metabolic network.

- Constraint-Based Modeling: Using genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate flux distributions and predict knockout/overexpression targets.

- Multi-Omics Integration: Correlating data from transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to identify non-obvious regulatory nodes and co-expressed gene clusters.

Experimental Protocol: A Systems Biology Workflow

A systems-driven metabolic engineering cycle involves [7]:

- Systems-Wide Data Acquisition: Cultivate the wild-type host and collect multi-omics data (transcriptome, metabolome) under production conditions.

- Computational Model Reconstruction & Simulation: Build or refine a genome-scale metabolic model. Use constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to simulate fluxes and identify new target genes beyond the obvious, linear pathway.

- Model-Guided Genetic Modifications: Implement a combination of gene knock-outs, knock-downs, and overexpressions as suggested by the model. This often involves multiplexed engineering.

- Validation and Model Refinement: Re-profile the omics data of the engineered strain and compare the results with model predictions. Use the discrepancies to refine the model for the next design-build-test cycle.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Systems Biology

| Reagent Type | Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| RNA/DNA Extraction Kit | Commercial kit for high-quality, inhibitor-free nucleic acids | Prepares samples for transcriptomic (RNA-seq) and genomic analysis. |

| Metabolite Quenching/Extraction Solvents | Cold methanol, acetonitrile | Rapidly halts metabolism and extracts intracellular metabolites for metabolomics. |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | High-purity water, acetonitrile, methanol | Enables high-sensitivity, reproducible detection of metabolites in complex mixtures. |

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Publicly available model (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli) | Provides the computational scaffold for simulating metabolic flux. |

| Software for Omics Analysis | CobraPy, MapMan, CoExpNetViz [9] | Tools for flux simulation, pathway mapping, and co-expression network analysis. |

The Third Wave: Synthetic Biology-Driven Engineering

The current wave, synthetic biology-driven engineering, is defined by the use of advanced computational algorithms to design and implement complex, often novel, biochemical pathways that are optimally integrated into the host's native metabolism [10] [8]. This approach moves beyond modifying existing pathways to constructing entirely new metabolic routes.

Core Principles and Computational Tools

- De Novo Pathway Design: Using biochemical databases and retrobiosynthesis algorithms to design pathways to target molecules not naturally produced by the host [10].

- Balanced Subnetwork Integration: Ensuring that heterologous pathways are stoichiometrically and thermodynamically balanced and properly connected to the host's core metabolism for cofactor and energy recycling [10].

- Automated Strain Design: Leveraging algorithms to select an optimal set of reactions from thousands of possibilities to achieve a design goal, such as maximum yield with minimal genetic parts.

Key Tool: The SubNetX Algorithm

A leading tool in this domain is SubNetX, a computational algorithm that extracts reactions from a database and assembles balanced subnetworks to produce a target biochemical from selected precursors [10]. Its workflow is a hallmark of the synthetic biology approach:

- Reaction Network Preparation: A database of balanced biochemical reactions (known and predicted) is defined.

- Graph Search: Linear core pathways from host precursors to the target compound are identified.

- Subnetwork Expansion: The network is expanded to link necessary cosubstrates and byproducts to the host's native metabolism, ensuring thermodynamic and stoichiometric feasibility.

- Host Integration: The subnetwork is integrated into a genome-scale metabolic model of the host (e.g., E. coli).

- Pathway Ranking: A Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) algorithm identifies the minimal set of essential heterologous reactions, and these feasible pathways are ranked based on yield, enzyme specificity, and thermodynamic feasibility [10].

Experimental Protocol: A Synthetic Biology Workflow

Implementing a synthetically designed pathway involves a highly integrated computational and experimental pipeline [10] [9] [7]:

- Target Selection & In Silico Pathway Design: Define the target molecule. Use a tool like SubNetX on a biochemical network (e.g., ARBRE or ATLASx) to extract multiple balanced, feasible biosynthetic routes.

- DNA Synthesis & Construct Assembly: Synthesize the chosen heterologous genes, codon-optimized for the host. Assemble them into multigene constructs using advanced DNA assembly techniques (e.g., Golden Gate assembly).

- Host Transformation & Screening: Transfer the constructs into a heterologous host (commonly E. coli or the plant Nicotiana benthamiana for transient expression). Screen for successful transformants and initial product detection.

- Systems-Level Optimization & Balancing: Fine-tune the system by employing synthetic biology parts (ribosome binding site libraries, promoters of varying strength) to balance the expression of multiple pathway enzymes and minimize metabolic burden [8].

- Fermentation Scale-Up & Production: Scale the production of the best-performing engineered strain in a bioreactor to obtain sufficient yields of the target compound.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Synthetic Biology-Driven Engineering

| Reagent Type | Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Algorithm | SubNetX [10] | Designs stoichiometrically balanced, feasible biosynthetic pathways from biochemical databases. |

| Biochemical Database | ARBRE, ATLASx [10] | Provides the network of known and predicted reactions for pathway extraction. |

| Codon-Optimized Gene Fragments | Synthetic DNA from commercial vendors | Provides heterologous genes optimized for expression in the chosen host organism. |

| Advanced Assembly Kit | Golden Gate Assembly MoClo Toolkit | Enables rapid, standardized assembly of multiple DNA parts into a single construct. |

| Synthetic Genetic Parts | Promoter/RBS libraries, degron tags [8] | Allows for fine-tuning of gene expression and protein levels to balance pathway flux. |

Table 4: Comparison of Engineering Waves for Native Pathways

| Aspect | Rational Engineering | Systems Biology | Synthetic Biology-Driven |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Focus | Single genes & linear pathways | Network-wide interactions & omics data | De novo pathway design & host integration |

| Primary Method | Gene overexpression/KO | Multi-omics & computational modeling | Algorithmic design & DBTL cycles |

| Data Utilization | Literature & kinetics | Genome-scale models & omics datasets | Biochemical databases & retrobiosynthesis |

| Pathway Complexity | Low (1-3 genes) | Medium | High (8+ genes, see Table 5) [9] |

| Key Limitation | Emergence of new bottlenecks | Model inaccuracy & hidden regulation | Enzyme specificity & unpredictable toxicity |

Table 5: Examples of Complex Pathways Engineered in Plants via Synthetic Biology [9]

| Type of Product | Final Product | Host Plant | Number of Expressed Genes | Reported Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoid | Baccatin III | Taxus media var. hicksii | 17 | 10–30 μg gâ»Â¹ DW |

| Phenolic compounds | (−)‑deoxy‑podophyllotoxin | Sinopodophyllum hexandrum | 16 | 4300 μg gâ»Â¹ DW |

| Triterpene glycoside | QS‑21 | Quillaja saponaria | 23 | nr |

| Monoterpene Indole Alkaloid | Strictosidine | Catharantus roseus | 14 | nr |

The journey from rational to synthetic biology-driven engineering represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach native pathway engineering. The first wave provided the essential tools for genetic manipulation. The second wave supplied the necessary holistic context, revealing the complexity of biological systems. The current, third wave synthesizes these elements with powerful computational design, enabling the construction of sophisticated genetic programs for the efficient bioproduction of complex natural and non-natural compounds [10] [9]. As computational tools like SubNetX become more advanced and integrated with machine learning and structural biology predictions, the design-build-test cycle will accelerate further. This progression promises to unlock new frontiers in drug development and the sustainable manufacturing of high-value chemicals, solidifying synthetic biology as the cornerstone of next-generation biomanufacturing.

The development of efficient microbial cell factories is paramount for the sustainable bioproduction of pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and materials. The core performance metrics defining a successful cell factory are titer (the concentration of the target product, e.g., in g/L), yield (the efficiency of substrate conversion to product, e.g., in mol/mol), and productivity (the rate of product formation, e.g., in g/L/h). Achieving high levels of all three simultaneously is the central challenge in metabolic engineering. This challenge is fundamentally rooted in an inherent trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis. Microbes have evolved to optimize resource utilization for growth and survival, not for the overproduction of a single compound. Consequently, engineering strategies that forcefully divert metabolic flux toward a target product often deplete precursors and energy (ATP, NADPH) required for biomass formation, leading to reduced growth, impaired fitness, and ultimately, suboptimal production performance [11].

This technical guide outlines the primary strategies for reconciling this conflict, focusing on native pathway engineering and systems-level approaches to maximize the core objectives. It synthesizes the most recent advances in the field, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design robust and high-performing cell factories.

Foundational Concepts and Quantitative Frameworks

A critical first step in developing a cell factory is the rational selection of a host organism and the evaluation of its innate potential. The Microbial Capacity Atlas, a landmark study, provides a quantitative framework for this selection by comparing the metabolic capabilities of five major industrial microbes for the production of 235 bio-based chemicals [12] [13]. This analysis utilizes genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to compute two key metrics:

- Maximum Theoretical Yield (Y_T): The stoichiometric upper limit of product formation per substrate when all resources are devoted to production, ignoring cell growth and maintenance.

- Maximum Achievable Yield (Y_A): A more realistic yield that accounts for the energy and resources required for cellular maintenance and a minimum growth rate (typically 10% of the maximum), providing a practical benchmark for metabolic capacity [13].

Table 1: Metabolic Capacity of Representative Host Strains for Selected Chemicals (under aerobic conditions with D-glucose) [13]

| Target Chemical | E. coli Y_A (mol/mol) | S. cerevisiae Y_A (mol/mol) | C. glutamicum Y_A (mol/mol) | B. subtilis Y_A (mol/mol) | P. putida Y_A (mol/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Lysine | 0.7985 | 0.8571 | 0.8098 | 0.8214 | 0.7680 |

| L-Glutamate | 0.8182 | 0.8182 | 0.8182 | 0.8182 | 0.8182 |

| Mevalonic Acid | Data not provided | Data not provided | Data not provided | Data not provided | Data not provided |

| Putrescine | Data not provided | Data not provided | Data not provided | Data not provided | Data not provided |

The analysis reveals that while S. cerevisiae shows the highest yield for many compounds, including L-Lysine, the optimal host is often chemical-specific [13]. For instance, C. glutamicum remains the industrial host of choice for L-glutamate production due to its well-known export mechanisms and high tolerance, despite identical theoretical yields across all hosts in the model [13]. This underscores that yield calculations must be integrated with other factors like transport mechanisms and toxin tolerance for host selection.

Core Engineering Strategies for Balancing Growth and Production

Growth-Coupling and Metabolic Rewiring

Growth-coupling is a powerful strategy that genetically links the production of the target compound to the host's ability to grow. This creates a strong selective pressure for high-yield production throughout fermentation, improving both stability and productivity [11]. This is achieved by strategically eliminating native metabolic routes to essential biomass precursors and creating synthetic pathways that simultaneously generate the precursor and the target product.

Table 2: Examples of Growth-Coupling Strategies in E. coli

| Target Compound | Central Metabolite Coupled to Growth | Key Metabolic Modifications | Reported Titer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthranilate & Derivatives [11] | Pyruvate | Deletion of native pyruvate-producing genes (pykA, pykF); overexpression of feedback-resistant anthranilate synthase. |

>2-fold increase over non-coupled strains |

| β-Arbutin [11] | Erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P) & Ribose 5-phosphate (R5P) | Deletion of zwf to block PPP; coupling E4P formation to R5P biosynthesis for nucleotides. |

28.1 g/L (fed-batch) |

| Butanone [11] | Acetyl-CoA | Deletion of native acetate assimilation pathways; coupling acetate assimilation to butanone synthesis via CoA transfer. | 855 mg/L |

| L-Isoleucine [11] | Succinate | Deletion of sucCD and aceA to block succinate formation; overexpression of alternative L-Ile biosynthetic enzymes. |

Data not provided |

The following diagram illustrates the general logic and workflow for implementing growth-coupling strategies in metabolic engineering.

Alleviating Metabolite Toxicity and Metabolic Burden

The accumulation of metabolic intermediates or final products can be toxic, disrupting cellular integrity and inhibiting enzyme function. Furthermore, the excessive expression of heterologous pathways imposes a metabolic burden, sequestering cellular resources like ribosomes, energy, and precursors away from growth and maintenance [14]. Key mitigation strategies include:

- Membrane and Transporter Engineering: Modifying membrane lipid composition to enhance integrity against toxic compounds. This can be achieved by overexpressing genes like

fabAandfabBto increase unsaturated fatty acid content, or introducing cis-trans isomerases to incorporate trans-unsaturated fatty acids, improving tolerance to solvents and acids [15]. Engineering efflux transporters to actively export toxic products from the cell is another highly effective approach [14]. - Transcription Factor (TF) Engineering: Using global or specific TFs to reprogram cellular responses to stress. Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) involves mutating core transcription components like the sigma factor RpoD in E. coli or Spt15 in S. cerevisiae, leading to broad improvements in tolerance to ethanol, solvents, and other inhibitors [15]. Overexpression of heterologous TFs like

IrrEfrom Deinococcus radiodurans can also confer robust tolerance to multiple stresses [15]. - Cofactor Engineering: Balancing the supply and demand of energy and redox cofactors (ATP, NADH, NADPH) is crucial. This can involve swapping the cofactor specificity of key enzymes (e.g., from NADH to NADPH) to better align with pathway requirements or introducing synthetic cycles for cofactor regeneration [12] [13].

Dynamic Regulation and Orthogonal Systems

Static, constitutive overexpression of pathway genes often leads to metabolic imbalance. Advanced strategies employ dynamic control to temporally separate growth and production phases.

- Dynamic Regulation: This uses genetic circuits that sense intracellular metabolites and automatically regulate pathway expression. For example, a circuit can be designed to repress a resource-intensive production pathway during the rapid growth phase and only derepress it once a sufficient cell density is reached, or when a key metabolite accumulates [11].

- Orthogonal Systems: These aim to decouple production from native metabolism entirely. Strategies include creating parallel metabolic pathways that do not interfere with host metabolism, using non-native carbon sources that are exclusively dedicated to product synthesis, and even incorporating synthetic nucleotides (xenobiotic nucleic acids) to create orthogonal genetic and translational systems [11].

Computational and Experimental Tools for Pathway Design

The design of complex pathways, especially for non-natural compounds, has been revolutionized by computational tools. Algorithms like SubNetX can extract and assemble balanced biochemical subnetworks from extensive reaction databases to connect a target molecule to host metabolism [10]. Unlike linear pathway predictors, SubNetX designs branched pathways that draw from multiple native precursors, ensuring stoichiometric and thermodynamic feasibility when integrated into a host's GEM. This approach has been successfully applied to design pathways for 70 industrially relevant, complex pharmaceuticals [10].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions for Cell Factory Engineering

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) [13] | In silico prediction of metabolic fluxes, yield, and gene knockout targets. | Identifying gene deletion targets for growth-coupled production of L-isoleucine. |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems [14] | Precision genome editing for gene knockouts, insertions, and repression. | Rapidly deleting competing pathways or integrating heterologous gene clusters. |

| Global Transcription Factor Library [15] | Broadly reprogram cellular stress response and metabolism. | Engineering ethanol tolerance in E. coli by mutating the rpoD gene. |

| Membrane-Impermeable Biotin Reagent [16] | Selective labeling of cell surface proteins for proteomic studies. | Quantifying apical vs. basolateral protein distribution in polarized epithelial cells. |

| Data-Independent Acquisition (DIA) Mass Spectrometry [16] | Comprehensive, unbiased quantification of proteomes. | Deep profiling of global cell surface proteome changes under stress. |

| Disulfide-Linked Biotin Reagent [16] | Chemoproteomic strategy for labeling extracellular domains of transmembrane proteins. | Identifying extracellular epitopes for diagnostic and therapeutic targeting. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps in a combined computational/experimental approach to pathway engineering, from design to validation.

Maximizing titer, yield, and productivity in microbial cell factories requires moving beyond simple pathway overexpression. The most successful strategies involve a systems-level approach that considers the cell as an integrated whole. This includes rationally selecting the host chassis based on quantitative metabolic capacities, employing growth-coupling to align production with fitness, and using dynamic regulation to optimally manage resources. Furthermore, engineering for robustness against metabolite toxicity and metabolic burden is not an optional step but a prerequisite for industrial-scale performance. The continued integration of advanced computational design tools like SubNetX with high-precision genome engineering and multi-omics analysis promises to further systematize the development of cell factories, transforming biomanufacturing from an empirical art into a predictive engineering discipline [12] [13] [10].

Metabolic engineering is the science of improving product formation or cellular properties through the modification of specific biochemical reactions or the introduction of new genes using recombinant DNA technology [17]. The field has evolved through three distinct waves of technological innovation. The first wave, beginning in the 1990s, relied on rational approaches to pathway analysis and flux optimization to redirect cellular metabolism toward desired products. A classic example from this era is the overproduction of lysine in Corynebacterium glutamicum, where simultaneous expression of pyruvate carboxylase and aspartokinase increased lysine productivity by 150% [17].

The second wave of metabolic engineering emerged in the 2000s with the integration of systems biology technologies, particularly genome-scale metabolic models. This holistic approach enabled researchers to bridge mechanistic genotype-phenotype relationships and explore the full metabolic potential of cell factories [17]. The third and current wave of metabolic engineering began with pioneering work on complete pathway design and optimization using synthetic biology approaches. This wave has expanded the array of attainable products, including natural, non-natural, inherent, and non-inherent chemicals, while dramatically improving production titers and rates [17].

Hierarchical metabolic engineering provides a structured framework for reprogramming cellular metabolism across multiple biological scales, from individual molecular components to entire cellular systems. This approach has enabled the creation of efficient microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical production [17].

Hierarchical Metabolic Engineering Framework

Part-Level Engineering: Foundational Molecular Components

Part-level engineering focuses on the most fundamental biological elements, including enzymes, coding sequences, and regulatory elements such as promoters and ribosome binding sites. At this hierarchy, enzyme engineering is crucial for optimizing catalytic activity, substrate specificity, and stability. Experimental protocols for enzyme engineering typically involve:

- Directed Evolution: Iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening for improved enzyme properties. Key steps include: (1) creating mutant libraries through error-prone PCR or DNA shuffling, (2) expressing variants in a suitable host, and (3) high-throughput screening for desired activities.

- Rational Design: Structure-based engineering using computational tools to identify key residues for mutation based on crystal structures and molecular modeling.

- Cofactor Engineering: Modifying enzyme cofactor specificity or availability to enhance pathway flux [17].

The table below summarizes key part-level engineering strategies and their applications:

Table 1: Part-Level Engineering Strategies and Applications

| Strategy | Technical Approach | Example Application | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Engineering | Directed evolution, rational design | 3-Hydroxypropionic acid production in S. cerevisiae | 18 g/L titer, 0.17 g/g glucose yield [17] |

| Cofactor Engineering | Modifying NADH/NADPH preference | Glycolate production in E. coli | 52.2 g/L titer [17] |

| Promoter Engineering | Synthetic promoter libraries | Itaconic acid production in S. cerevisiae | 1.2 g/L titer [17] |

| Transporter Engineering | Membrane transporter optimization | Lysine production in C. glutamicum | 223.4 g/L titer, 0.68 g/g glucose yield [17] |

Pathway-Level Engineering: Orchestrating Reaction Sequences

Pathway-level engineering involves designing, constructing, and optimizing multi-enzyme pathways to convert substrates into valuable products. Modular pathway engineering is a key strategy at this level, where complex pathways are divided into manageable modules that can be independently optimized. Essential experimental protocols include:

- Pathway Design and Assembly: Computational design of biosynthetic pathways using tools such as RetroPath or ATLAS, followed by physical assembly using DNA synthesis and standard assembly methods (Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate).

- Balancing Gene Expression: Fine-tuning expression levels of pathway enzymes using promoter engineering, ribosome binding site modification, and gene copy number optimization.

- Bottleneck Identification: Using metabolomics and flux analysis to identify rate-limiting steps, followed by targeted enzyme engineering or expression optimization.

Table 2: Representative Pathway-Level Engineering Achievements

| Product | Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid | C. glutamicum | Modular pathway engineering | 212 g/L L-lactic acid, 97.9% yield; 264 g/L D-lactic acid, 95.0% yield [17] |

| Propionic Acid | P. freudenreichii | Modular pathway engineering | 136.23 g/L titer, 0.5 g/g glucose yield, 0.57 g/L/h productivity [17] |

| Malonic Acid | Y. lipolytica | Modular pathway engineering, genome editing, substrate engineering | 63.6 g/L titer, 0.41 g/L/h productivity [17] |

| Muconic Acid | C. glutamicum | Modular pathway engineering, chassis engineering | 54 g/L titer, 0.197 g/g glucose yield, 0.34 g/L/h productivity [17] |

Diagram 1: Modular Pathway Engineering Workflow

Network-Level Engineering: Systemic Metabolic Optimization

Network-level engineering takes a systems-wide perspective, optimizing the complete metabolic network of the cell to support product formation while maintaining cellular fitness. Key approaches include:

- Flux Balance Analysis: Constraint-based modeling of metabolic networks to predict optimal flux distributions and identify gene knockout targets.

- Cofactor Balancing: Global optimization of energy and redox cofactors (ATP, NADH, NADPH) across the entire metabolic network.

- Regulatory Network Engineering: Modulating transcription factors and regulatory networks to rewire global gene expression patterns.

Experimental protocols for network-level engineering involve:

- Genome-Scale Model Reconstruction: Developing organism-specific metabolic models using automated tools like ModelSEED or CarveMe, followed by manual curation.

- Flux Scanning: Enforcing objective flux to identify key overexpression targets, as demonstrated for enhanced lycopene production [17].

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Algorithms that identify key gene knockout targets for production of compounds like cubebol, L-threonine, and L-valine [17].

Genome-Level Engineering: Chromosomal Integration and Scale

Genome-level engineering focuses on large-scale chromosomal modifications, including gene knockouts, integrations, and genome reduction. CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized this hierarchy by enabling precise genome editing. The experimental protocol for CRISPR-mediated genome editing includes:

- Target Selection: Identifying specific genomic loci with high editing efficiency and minimal off-target effects using tools like CHOPCHOP or CRISPRscan.

- gRNA Design and Synthesis: Designing guide RNA sequences with high on-target activity, typically 17-20 nucleotides adjacent to a PAM sequence [18].

- Repair Template Design: Constructing donor DNA templates with homology arms (typically 500-1000 bp) flanking the desired modification.

- Delivery System: Co-delivering Cas9, gRNA, and repair template to target cells via electroporation, nucleofection, or viral vectors.

- Screening and Validation: Isolating edited clones and verifying modifications through PCR, sequencing, and functional assays [18].

Table 3: Advanced Genome Editing Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism | Advantages | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | RNA-guided DSBs, blunt ends | Versatile PAM (NGG), highly efficient | Gene knockouts, point mutations, small insertions [18] |

| CRISPR-Cpf1 | RNA-guided DSBs, staggered ends | T-rich PAM, minimal target site interference | Gene insertion, particularly in AT-rich regions [18] |

| Base Editing | Chemical conversion without DSBs | Reduced indel formation, high precision | Transition mutations (C→T, A→G) [18] |

| Prime Editing | Reverse transcriptase template | Versatile all possible edits, minimal DSBs | Precise insertions, deletions, all base conversions [18] |

Cell-Level Engineering: Integrated Cellular Performance

Cell-level engineering represents the highest hierarchy, focusing on the integrated performance of the engineered cell factory. This includes optimizing cellular physiology, stress tolerance, and community interactions. Key strategies include:

- Tolerance Engineering: Enhancing resistance to inhibitory compounds, osmotic stress, or the target product itself.

- Chassis Engineering: Optimizing host physiology for specific production goals, as demonstrated for 3-hydroxypropionic acid production in K. phaffii (27.0 g/L titer) [17].

- Coculture Systems: Engineering synthetic microbial communities for division of labor in complex biosynthetic pathways.

Diagram 2: Hierarchical Structure of Metabolic Engineering

Enabling Technologies and Computational Tools

Machine Learning in Metabolic Engineering

Machine learning has emerged as a powerful tool across all hierarchies of metabolic engineering. Applications include:

- Protein Function Prediction: Using sequence data to predict enzyme activity and specificity, as demonstrated in engineering cyanobacterial rhodopsins for broad-spectrum energy capture [19].

- Pathway Optimization: Analyzing multi-omics data to identify key regulatory nodes, such as in deciphering cytokinin signaling cascades to prolong photosynthesis and boost yield [19].

- Design-Build-Test-Learn Cycles: Iterative framework where machine learning models use experimental data to improve subsequent design decisions.

Synthetic Biology Tools for Pathway Refactoring

Synthetic biology provides essential tools for pathway refactoring and optimization:

- DNA Synthesis: De novo synthesis of optimized genetic circuits and pathways, enabling codon optimization, removal of regulatory elements, and GC-content adjustment.

- Standardized Assembly: Modular cloning systems (MoClo, Golden Gate) for rapid assembly and testing of pathway variants.

- Dynamic Regulation: Engineering synthetic regulatory circuits for autonomous pathway control, such as metabolite-responsive biosensors that dynamically regulate expression levels.

Experimental Protocols for Functional Analysis

Protein-DNA Binding assays for Regulatory Element Validation

For characterizing regulatory elements identified through hierarchical approaches:

- ChIP-Seq Protocol: (1) Crosslink proteins to DNA with formaldehyde, (2) shear chromatin to 200-500 bp fragments, (3) immunoprecipitate with target transcription factor antibody, (4) reverse crosslinks and purify DNA, (5) sequence and map reads to reference genome [20].

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): (1) Prepare DNA probes surrounding candidate variant (~20-100 bp), (2) incubate with purified TFs or nuclear extracts, (3) separate protein-DNA complexes from free DNA via gel electrophoresis, (4) visualize shift in mobility indicating binding [20].

- DNA-Affinity Pulldown with Mass Spectrometry: (1) Design biotinylated oligonucleotide probes, (2) incubate with nuclear extracts, (3) capture DNA-protein complexes with streptavidin beads, (4) identify bound proteins via mass spectrometry [20].

Genome Editing Workflow for Strain Development

Comprehensive protocol for creating precisely edited production strains:

- Design Phase: (1) Select target locus, (2) design gRNAs with minimal off-target potential, (3) synthesize repair template with 500-800 bp homology arms.

- Delivery Phase: (1) Clone gRNA and repair template into appropriate expression vectors, (2) transform into target organism, (3) induce nuclease expression.

- Screening Phase: (1) Isolate single clones, (2) genotype by colony PCR and sequencing, (3) verify absence of off-target mutations.

- Characterization Phase: (1) Measure production metrics in controlled bioreactors, (2) analyze transcriptome and metabolome, (3) assess genetic stability over multiple generations [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hierarchical Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Targeted DNA cleavage for genome editing | SpCas9 (NGG PAM), FnCpf1 (TTN PAM), LbCpf1 (TTN PAM) [18] |

| DNA Assembly Systems | Pathway construction and refactoring | Gibson Assembly, Golden Gate, MoClo toolkit [17] |

| Promoter Libraries | Tunable gene expression at part level | Synthetic promoters, hybrid promoters, inducible systems [17] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Pathway flux measurement and optimization | GFP, RFP, YFP for transcriptional fusion [17] |

| Biosensors | Dynamic regulation and screening | Metabolite-responsive transcription factors [17] |

| Genome-Scale Models | Network-level optimization and prediction | GEMs for E. coli, S. cerevisiae, C. glutamicum [17] |

| Analytical Standards | Metabolite quantification and validation | LC-MS/MS standards for target metabolites [17] |

| Parishin G | Parishin G, MF:C19H24O13, MW:460.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isomargaritene | Isomargaritene, CAS:64271-11-0, MF:C28H32O14, MW:592.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Hierarchical metabolic engineering represents a mature framework for systematic development of microbial cell factories. The integration of synthetic biology, computational tools, and automation continues to accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle across all biological hierarchies. Future advances will likely focus on:

- Automated Strain Engineering: Combining robotic automation with machine learning for high-throughput design and testing.

- Pangenome Engineering: Moving beyond single reference genomes to engineer across species and construct synthetic pangenomes.

- Community Engineering: Designing synthetic microbial consortia with distributed metabolic functions for complex biotransformations.

The hierarchical framework from parts and pathways to genome and network-level engineering provides a comprehensive roadmap for rewiring cellular metabolism. This approach has already demonstrated remarkable success in producing diverse chemicals, from bulk commodities to complex pharmaceuticals, and will continue to drive innovations in sustainable bioproduction [17].

Advanced Toolkits: Computational Design, AI, and High-Throughput Assembly

The engineering of microbial cell factories for producing valuable chemicals relies on the design and optimization of biosynthetic pathways. Computational pathway design has emerged as a critical discipline that addresses the fundamental challenge of identifying efficient routes for converting available precursors into target biochemicals. Traditional metabolic engineering approaches often face limitations when dealing with complex molecules that require reactions from multiple pathways operating in balanced subnetworks not assembled in existing databases. The sheer complexity of metabolic networks, with their myriad interactions and regulatory mechanisms, makes manual pathway design time-consuming and often suboptimal. For instance, the production of artemisinin required 150 person-years of effort, while propanediol consumed 575 person-years, highlighting the critical need for computational acceleration in this field [21].

The evolution of computational tools has transformed pathway design from a purely experimental endeavor to an integrated computational-experimental workflow. Early approaches relied heavily on known biochemical pathways from curated databases, but these were limited to naturally occurring routes. The recognition that natural evolution predominantly favors cellular survival rather than the production of industrially valuable compounds has driven the development of tools that can design fully nonnatural metabolic pathways [22]. This paradigm shift enables researchers to move beyond nature's blueprint and create novel biosynthetic routes for compounds without known natural pathways, such as 2,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid and 1,2-butanediol [22].

Algorithmic Foundations: SubNetX and Beyond

The SubNetX Algorithm

SubNetX represents a significant advancement in computational pathway design, specifically addressing the challenge of assembling balanced subnetworks for producing target biochemicals. This algorithm extracts reactions from biochemical databases and assembles them into functional subnetworks that connect selected precursor metabolites to target molecules while maintaining stoichiometric balance for energy currencies and cofactors [23] [24]. The core innovation of SubNetX lies in its ability to identify and assemble reactions from multiple pathways that are not naturally connected in existing databases, creating novel routes for complex chemical production.

The algorithm operates through a multi-stage process that begins with pathway extraction from comprehensive biochemical databases, followed by network assembly that ensures thermodynamic feasibility and host compatibility. SubNetX implements sophisticated ranking methodologies that evaluate pathways based on multiple criteria including theoretical yield, pathway length, energy efficiency, and host compatibility [23]. This multi-dimensional assessment allows researchers to select optimal pathways based on their specific design goals, whether prioritizing maximum yield, minimal enzymatic steps, or compatibility with specific host organisms.

Complementary Computational Approaches

Beyond SubNetX, the computational toolbox for pathway design includes two major methodological families: template-based and template-free approaches [22]. Template-based methods rely on known biochemical reaction rules and enzyme functions to propose novel pathways, while template-free approaches generate reactions based on chemical feasibility without being constrained by known enzymatic transformations. The ARBRE computational resource specializes in predicting pathways toward industrially important aromatic compounds, building comprehensive biochemical reaction networks centered around aromatic amino acid biosynthesis [24].

Another significant innovation is the ATLAS of Biochemistry, which serves as a repository of all theoretically possible biochemical reactions based on known biochemical principles and compounds [24]. This expansive database enables researchers to explore novel biochemistry beyond naturally occurring reactions, dramatically expanding the design space for metabolic engineering. The BridgIT method further complements these approaches by identifying candidate enzymes for novel reactions through knowledge of substrate reactive sites, addressing the critical challenge of enzyme annotation for orphan and novel reactions [24].

Essential Biological Databases for Pathway Design

Table 1: Key Databases for Computational Pathway Design

| Category | Database | Primary Function | Application in Pathway Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Information | PubChem [21] | Chemical compound structures and properties | Foundation for reaction and pathway databases |

| ChEBI [21] | Focused on small molecular compounds | Provides detailed structural and biological activity data | |

| NPAtlas [21] | Curated natural products repository | Source for bioactive compound structures | |

| Reaction/Pathway Information | KEGG [21] | Integrated genomic, chemical, and systemic functional information | Reference for known metabolic pathways |

| MetaCyc [21] | Metabolic pathways and enzymes across organisms | Studying metabolic diversity and evolution | |

| Rhea [21] | Biochemical reactions with detailed equations | Enzyme-catalyzed reaction information | |

| BKMS-react [21] | Integrated biochemical reaction database | Non-redundant collection of enzyme-catalyzed reactions | |

| Enzyme Information | BRENDA [21] | Comprehensive enzyme function data | Detailed enzyme mechanisms and specificity |

| UniProt [21] | Protein sequence and functional information | Enzyme function across organisms | |

| AlphaFold DB [21] | Predicted protein structures | Enzyme structure-function relationships | |

| Cinnamtannin D2 | Cinnamtannin D2, CAS:97233-47-1, MF:C60H48O24, MW:1153.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Platycogenin A | Platycogenin A|For Research | Platycogenin A is a key triterpenoid from Platycodon grandiflorus. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The effectiveness of computational pathway design algorithms depends fundamentally on the quality and diversity of underlying biological data. Comprehensive databases covering compounds, reactions, pathways, and enzymes form the foundation upon which tools like SubNetX operate [21]. Compound databases such as PubChem, ChEBI, and specialized collections like NPAtlas provide essential information on chemical structures, properties, and biological activities. These resources are particularly crucial when designing pathways for complex natural products or synthetic compounds with limited characterization.

Reaction and pathway databases offer curated knowledge about metabolic networks and biochemical transformations. KEGG and MetaCyc provide broad coverage of known metabolic pathways across diverse organisms, while specialized resources like Rhea and BKMS-react offer detailed biochemical reaction information with enzyme annotations [21]. For enzyme-centric design, databases including BRENDA, UniProt, and AlphaFold DB provide critical information on enzyme functions, sequences, and structures. The integration of these disparate data sources enables comprehensive pathway predictions that account for biochemical feasibility, enzyme availability, and host organism compatibility.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Computational Workflow Implementation

The implementation of computational pathway design follows a structured workflow that begins with target compound specification and concludes with experimental validation. The initial phase involves precursor selection, where researchers define the starting metabolites available to the production host. This is followed by database mining where tools like SubNetX extract relevant reactions from comprehensive biochemical databases [23]. The core algorithmic processing then assembles these reactions into balanced subnetworks that connect precursors to the target compound while maintaining stoichiometric balance for energy currencies and cofactors.

The subsequent pathway ranking phase employs multi-criteria optimization to evaluate and prioritize the generated pathways. This evaluation typically considers theoretical yield calculations based on stoichiometric constraints, pathway length (number of enzymatic steps), thermodynamic feasibility estimated through energy requirements, and host compatibility assessing whether necessary enzymatic activities exist in the target production host [23] [21]. The highest-ranked pathways are then integrated into genome-scale metabolic models of host organisms to predict physiological impacts and identify potential bottlenecks before experimental implementation.

Pathway Validation and Optimization

Experimental validation of computationally designed pathways follows the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, which has become the cornerstone of modern metabolic engineering [21]. The Design phase involves computational pathway prediction and optimization. The Build phase implements these designs through gene synthesis and assembly, employing techniques such as Golden Gate assembly or CRISPR-Cas genome editing to construct the pathways in microbial hosts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Escherichia coli [25].

The Test phase involves culturing the engineered strains under controlled conditions and employing analytical chemistry techniques to quantify pathway intermediates and products. Key methodologies include mass spectrometry for metabolite identification and quantification, chromatography for compound separation, and enzyme assays to verify catalytic activities [21] [26]. For complex pathway engineering, especially in plants, researchers often use transient expression systems for rapid testing before committing to stable transformation [26]. The Learn phase utilizes the experimental data to refine computational models and identify specific bottlenecks, such as toxic intermediate accumulation, enzyme kinetics limitations, or cofactor imbalances, which then inform the next design iteration [22] [21].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Pathway Engineering

| Category | Reagent/Resource | Function in Pathway Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | BKMS-react [21] | Non-redundant biochemical reactions for pathway extraction |

| ATLAS of Biochemistry [24] | Theoretical biochemical reactions for novel pathway design | |

| ARBRE [24] | Specialized resource for aromatic compound pathways | |

| Enzyme Engineering | BRENDA [21] | Enzyme functional data for enzyme selection |

| UniProt [21] | Protein sequence information for enzyme design | |

| AlphaFold DB [21] | Protein structures for enzyme engineering | |

| Experimental Tools | Golden Gate Assembly [26] | Modular DNA assembly for pathway construction |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems [26] | Genome editing for pathway integration | |

| LC-MS/MS [26] | Metabolite profiling and pathway validation | |

| Host Systems | Saccharomyces cerevisiae [25] | Eukaryotic host with industrial relevance |

| Escherichia coli [21] | Prokaryotic host with well-characterized genetics | |

| Pseudomonas putida [27] | Host for aromatic compound transformation | |

| Shikokianin | Shikokianin | Explore Shikokianin, a high-purity reagent for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Officinaruminane B | Officinaruminane B, MF:C29H36O, MW:400.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The experimental implementation of computationally designed pathways requires a comprehensive toolkit of research reagents and resources. Database resources form the foundation, with BKMS-react providing integrated biochemical reactions, while specialized resources like ATLAS of Biochemistry and ARBRE enable exploration of novel biochemistry beyond naturally occurring pathways [21] [24]. For enzyme engineering, BRENDA offers comprehensive enzyme function data, UniProt provides protein sequence information, and AlphaFold DB delivers predicted protein structures to inform enzyme selection and engineering strategies [21].

Molecular biology tools for pathway construction have evolved significantly, with modular DNA assembly methods like Golden Gate Assembly enabling efficient construction of multi-gene pathways [26]. CRISPR-Cas systems have revolutionized genome editing, allowing precise integration of heterologous pathways into host genomes [26]. Analytical tools, particularly LC-MS/MS systems, provide essential capabilities for metabolite profiling and pathway validation [26]. The selection of appropriate host organisms remains critical, with each offering distinct advantages: Saccharomyces cerevisiae for eukaryotic complexity and industrial robustness, Escherichia coli for rapid growth and well-characterized genetics, and specialized hosts like Pseudomonas putida for handling toxic intermediates or transforming aromatic compounds [25] [27].

Applications and Case Studies

The practical application of computational pathway design tools has demonstrated significant impact across multiple domains. SubNetX has been successfully applied to 70 industrially relevant natural and synthetic chemicals, generating novel production routes that would be challenging to discover through traditional methods [23]. In industrial bioethanol production, pathway engineering strategies have focused on altering the ratio of ethanol production, yeast growth, and glycerol formation to improve yield on carbohydrate feedstocks [25]. These approaches have targeted both energy coupling of alcoholic fermentation and redox-cofactor coupling in carbon and nitrogen metabolism to reduce or eliminate glycerol formation, which represents a carbon diversion from the desired product.

In the realm of plant specialized metabolites, computational pathway design has enabled the engineering of complex, multi-step pathways requiring the expression of at least eight genes for transient transformation and three genes for stable transformation [26]. These efforts face unique challenges, including the need for comprehensive knowledge of genes and enzymes involved, as well as precursors, intermediates, branching points, and final metabolites. Successful cases demonstrate how computer-based predictions offer valuable platforms for the sustainable production of specialized metabolites in plants [26]. For pharmaceutical compounds, computational workflows have been developed for identifying potential derivatives and the enzymes required to produce them, as demonstrated in the noscapine pathway engineered in yeast [24].

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, computational pathway design faces several persistent challenges. The massive search space of possible biochemical reactions, combined with complex metabolic pathway interactions and biological system uncertainties, continues to test the limits of current algorithms [21]. The implementation of nonnatural pathways introduces new challenges, including increased metabolic burden on host organisms and the potential accumulation of toxic intermediates that can impair cellular function [22]. Additionally, there remains a significant gap between computational predictions and empirical feasibility, as highlighted by evaluations of 55 experimentally validated nonnatural pathways [22].

Future developments in the field are likely to focus on integrating multi-omics data to constrain and refine pathway predictions, incorporating kinetic parameters to better predict flux distributions, and developing machine learning approaches to identify patterns across successfully engineered pathways [22] [21]. The integration of protein engineering with pathway design represents another promising direction, enabling the creation of custom enzymes for novel biochemical transformations [21] [24]. As the field progresses, the increasing integration of computational tools with experimental synthetic biology promises to accelerate the design and optimization of microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical production.

The potential impact of these advancements extends across multiple industries, from pharmaceuticals and specialty chemicals to biofuels and biomaterials. By enabling more efficient and sustainable production routes, computational pathway design tools like SubNetX are poised to play a crucial role in the transition toward a circular bioeconomy, reducing dependence on fossil resources and decreasing the environmental footprint of chemical manufacturing.

Harnessing AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Pathway Modeling and Enzyme Engineering

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is fundamentally transforming the fields of predictive pathway modeling and enzyme engineering. This synergy is moving biocatalyst design from a largely trial-and-error based discipline to a predictive science, enabling researchers to navigate the vast complexity of biological systems with unprecedented precision. For researchers and drug development professionals, these technologies offer powerful tools to tackle some of the most persistent challenges in native pathway engineering: optimizing multi-step metabolic pathways, balancing redox cofactors, managing energy metabolism, and engineering enzymes with enhanced catalytic properties for specific industrial applications [25] [28] [9].

The transition is driven by the need for more sustainable bioprocesses and the limitations of conventional methods. Traditional directed evolution, while successful, is often laborious and low-throughput, constraining the exploration of protein sequence space and frequently missing beneficial epistatic interactions [29]. Similarly, metabolic pathway engineering often relies on iterative, time-consuming experimental cycles. AI and ML are now breaking these barriers by enabling the rapid generation and interpretation of large datasets, providing data-driven insights for forward engineering of biocatalysts and pathways [29] [28]. This technical guide delves into the core computational methods, experimental protocols, and practical tools that are defining the cutting edge of this integrated approach.

Computational Foundations for Enzyme Engineering

Computational tools are indispensable for rational enzyme engineering, providing a strategic framework to guide experimental campaigns and drastically improve their success rates [28] [30]. These tools can be systematically categorized based on the specific biocatalytic property they are designed to optimize.

A Toolbox for Specific Biocatalytic Properties

The following table summarizes key computational tools and their applications for enhancing critical enzyme properties, providing a practical guide for researchers to select the appropriate software for their protein engineering campaigns [30].

Table 1: Computational Tools for Engineering Key Biocatalytic Properties

| Target Property | Computational Approach | Example Tools/Methods | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand Affinity/Selectivity | Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Binding Free Energy Calculations | Docking software (AutoDock, Vina), MD packages (GROMACS, NAMD) | Predicts binding poses and interaction energies to optimize substrate specificity and inhibitor design. |

| Catalytic Efficiency | Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM), Transition State Analysis | QM/MM software | Models enzyme mechanism and transition state stabilization to inform mutations for improved ( k{cat} ) or lowered ( Km ). |

| Thermostability | Flexibility Analysis, In Silico Saturation Mutagenesis, FoldX | FoldX, Rosetta | Identifies rigidifying mutations (e.g., disulfide bridges, proline substitutions) to enhance stability at elevated temperatures. |

| Solubility & Expression | Surface Engineering, Aggregation Propensity Prediction | Tools for predicting solubility and aggregation | Reduces aggregation-prone regions and optimizes surface charges to improve recombinant protein yield. |

The effectiveness of these tools hinges on their scoring functions, which are designed to evaluate and predict the impact of mutations. For instance, tools like FoldX and Rosetta use empirical force fields and physical energy functions, respectively, to calculate the change in free energy upon mutation, allowing for the rapid in silico screening of thousands of variants [30]. This capability is critical for moving away from random mutagenesis and towards focused libraries with a higher probability of containing improved enzymes.

Machine Learning-Guided Directed Evolution

A powerful paradigm that has emerged is ML-guided directed evolution. This approach uses machine learning models trained on sequence-function data to navigate the fitness landscape and predict highly active enzyme variants, significantly reducing experimental screening burden [29].

A landmark study demonstrated this by engineering the amide synthetase McbA. The workflow involved:

- Generating a large dataset: A site-saturation mutagenesis library of 1216 single-point mutants was created and tested for activity on three distinct pharmaceutical substrates.

- Training ML models: The resulting sequence-function data was used to train supervised ridge regression models, augmented with an evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictor.

- Predicting and validating improved variants: The trained models were used to extrapolate and predict higher-order mutants with increased activity. The result was a set of engineered enzymes with 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity relative to the wild-type enzyme across nine different small molecule pharmaceuticals [29].

This DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) cycle exemplifies how ML can exploit nonlinearities and epistatic interactions in sequence space that are often missed by low-throughput screening methods.

Diagram 1: ML-guided DBTL cycle for enzyme engineering.

Predictive Modeling of Native Pathways

Predictive pathway modeling extends the principles of computational design to the scale of metabolic networks. The goal is to model and predict the flux of metabolites through interconnected biochemical pathways to identify key engineering targets for improved product yield.

Software and Databases for Pathway Analysis

Several bioinformatics platforms are essential for this work. Pathway Tools is a comprehensive software package that supports the development of organism-specific databases, metabolic reconstruction, and metabolic-flux modeling using flux-balance analysis [31]. It is instrumental in creating metabolic models from genomic data and identifying potential choke points in metabolic networks. Similarly, the Reactome Pathway Database provides a curated resource of human biological pathways, which is crucial for understanding the native context of drug targets and metabolic processes [32].

Engineering Complex Multi-Gene Pathways in Plants

Engineering native pathways in plants for the production of specialized metabolites is a major application of predictive modeling. This process involves the reconstruction of complex, multi-step pathways in heterologous plant systems like Nicotiana benthamiana [9]. Success in this area requires deep knowledge of the pathway enzymes, regulators, and transporters, as well as strategies to overcome challenges such as the toxicity of pathway intermediates and competition with endogenous metabolism.

The quantitative outcomes of several successful complex pathway engineering efforts in plants are summarized in the table below, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach for high-value compounds.

Table 2: Selected Examples of Complex Metabolic Pathway Engineering in Plants

| Final Product | Host Plant | Number of Expressed Genes | Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Momilactones | Oryza sativa (Rice) | 8 | 167 μg gâ»Â¹ dry weight | [9] |

| Cocaine | Erythroxylum novogranatense | 8 | 398.3 ± 132.0 ng mgâ»Â¹ dry weight | [9] |

| Baccatin III (precursor to paclitaxel) | Taxus media var. hicksii | 17 | 10–30 μg gâ»Â¹ dry weight | [9] |

| (–)-deoxy-podophyllotoxin | Sinopodophyllum hexandrum | 16 | 4300 μg gâ»Â¹ dry weight | [9] |

| N-Formyldemecolcine | Gloriosa superba | 16 | 6.3 ± 1.3 μg gâ»Â¹ dry weight | [9] |

The roadmap for such engineering begins with comprehensive 'omics' data integration (genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics) to elucidate the pathway and identify candidate genes. In silico tools like GeNeCK and MapMan are then used for co-expression and differential expression analysis to prioritize gene targets [9]. Finally, the pathway is assembled and optimized in a heterologous host, a process increasingly guided by computational models to balance flux and avoid rate-limiting steps.

Diagram 2: Predictive pathway engineering workflow for specialized metabolites.

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Translating computational predictions into validated engineered systems requires robust experimental workflows. Below is a detailed protocol for an integrated AI/ML-driven enzyme engineering campaign, as exemplified by the ML-guided cell-free platform for amide synthetase engineering [29].

Detailed Protocol: ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering with Cell-Free Expression

Objective: To engineer an enzyme for enhanced activity on a specific substrate using a machine-learning guided, cell-free platform. Key Features: This protocol bypasses traditional cloning and transformation in living cells, enabling rapid generation of sequence-defined protein libraries for ML model training.

Materials & Reagents:

- Template DNA: Plasmid containing the wild-type gene of the enzyme of interest (e.g., McbA).

- PCR Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and mutagenic primers for site-saturation mutagenesis.

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFE) System: A reconstituted transcription-translation system containing all necessary components for protein expression (e.g., T7 RNA polymerase, ribosomes, tRNAs, amino acids, energy sources) [29].

- Functional Assay Reagents: Substrates, cofactors (e.g., ATP), and detection methods (e.g., LC-MS, fluorescence) for measuring enzyme activity.

Procedure:

Design and Build Variant Library:

- In Silico Design: Select target residues for mutagenesis (e.g., residues within 10 Ã… of the active site).

- PCR with Mutagenic Primers: For each target residue, perform PCR using primers containing a nucleotide mismatch to introduce all 19 possible amino acid substitutions. This creates a library of mutated plasmid DNA.

- DNA Assembly and Preparation:

- Digest the parent plasmid with DpnI to eliminate methylated template DNA.

- Perform intramolecular Gibson assembly to form circular mutated plasmids.

- Amplify linear DNA expression templates (LETs) via a second PCR. LETs are directly used in the CFE system without the need for bacterial transformation [29].

Test Library for Sequence-Function Data:

- Cell-Free Expression: Use the LETs in the CFE system to express the enzyme variants in a high-throughput format (e.g., 96-well or 384-well plates).