Resolving Underdetermined Flux Distributions in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a powerful technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic reaction rates, a crucial capability for understanding cell physiology in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and disease mechanism research.

Resolving Underdetermined Flux Distributions in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a powerful technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic reaction rates, a crucial capability for understanding cell physiology in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and disease mechanism research. However, a fundamental challenge in 13C-MFA is the inherent underdeterminacy of metabolic networks, where insufficient measurements prevent unique flux determination. This article provides a comprehensive framework for tackling this underdeterminacy, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the mathematical foundations of underdetermined systems, review classical and emerging computational strategies for flux resolution, provide best practices for experimental design and troubleshooting, and critically evaluate methods for model validation and statistical uncertainty quantification. By synthesizing established protocols with recent advances in parallel labeling, Bayesian statistics, and high-performance computing, this guide empowers scientists to generate more reliable and precise flux maps, thereby enhancing confidence in model-derived biological insights.

Understanding the Underdeterminacy Problem in Metabolic Networks

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Metabolic Flux Analysis. This resource is designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who are encountering challenges with underdetermined metabolic networks in their 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) work. Underdeterminacy—a state where available experimental data is insufficient to calculate a unique flux distribution—is a fundamental characteristic of complex metabolic systems. This guide provides practical troubleshooting advice and foundational knowledge to help you navigate these challenges, framed within the broader thesis that understanding underdeterminacy is crucial for developing robust strategies to constrain biological solutions and extract meaningful physiological insights.

Understanding the Core Problem

What is an underdetermined metabolic system?

An underdetermined metabolic system occurs when the number of unknown intracellular fluxes exceeds the number of available independent equations derived from mass balances and extracellular measurements [1]. This situation is mathematically represented by a stoichiometric matrix N where the number of independent rows (representing balanced metabolites) is less than the number of columns (representing metabolic reactions) [1]. In practice, this means that infinitely many flux distributions can satisfy the available constraints, forming a solution space rather than yielding a single, unique solution [1] [2].

Why are metabolic networks frequently underdetermined?

Most metabolic networks are inherently underdetermined because [1]:

- Network Complexity: Metabolic networks typically contain numerous parallel pathways, cycles, and reversible reactions, creating more degrees of freedom than constraints.

- Measurement Limitations: Experimental techniques can only measure a limited number of extracellular uptake/secretion rates, while most fluxes are intracellular and cannot be directly measured.

- Stoichiometric Constraints Alone Are Insufficient: The steady-state mass balance equation Nv = 0 (where v is the flux vector) typically defines a solution space with multiple dimensions rather than a single point [1].

The diagram below illustrates why an underdetermined system lacks a unique solution.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How can I determine if my metabolic network is underdetermined?

Answer: Calculate the degrees of freedom in your system using the formula [1]:

If the degrees of freedom are greater than zero, your system is underdetermined. For example, in a network with 8 fluxes and 5 independent metabolites, you have 3 degrees of freedom, indicating an underdetermined system [1].

Troubleshooting Tip: Use software tools like 13CFLUX2 [3] or Metatool [1] to automatically analyze your network structure and identify the number of free fluxes.

FAQ 2: What practical approaches can I use to resolve underdeterminacy?

Answer: Two main strategies exist for tackling underdeterminacy [1]:

Table 1: Strategies for Handling Underdetermined Systems

| Strategy | Description | Common Methods | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dealing with Underdeterminacy | Characterizing the range of possible solutions without eliminating ambiguity | Flux Variability Analysis (FVA), Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs), Random Sampling [1] | When seeking to understand possible flux ranges rather than single values |

| Reducing/Eliminating Underdeterminacy | Adding constraints to narrow or uniquely determine the solution | 13C-MFA, Thermodynamic constraints, Optimality principles (FBA), Most Accurate Fluxes [1] [2] | When a single, unique flux distribution is required |

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for designing tracer experiments to reduce underdeterminacy?

Answer: Effective 13C-MFA experimental design should incorporate these key practices [4] [5] [3]:

- Use Parallel Labeling Experiments: Employ multiple 13C-labeled tracers (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose) in parallel cultures to generate complementary labeling information [5].

- Apply Robust Experimental Design (R-ED): When prior flux knowledge is limited, use sampling-based approaches to identify tracer mixtures that are informative across a wide range of possible flux values [3].

- Measure Multiple Labeling Patterns: Analyze protein-bound amino acids, glycogen-bound glucose, and RNA-bound ribose via GC-MS to obtain extensive labeling data for flux constraints [5].

- Validate Tracer Purity: Always measure the isotopic purity of tracers and actual labeling in the medium, as impurities can significantly impact flux results [4].

Troubleshooting Tip: If working with novel organisms or pathways with unknown fluxes, implement the R-ED workflow [3] to avoid the "chicken-and-egg" problem where tracer design requires prior flux knowledge.

FAQ 4: How can I validate the results from my flux analysis in underdetermined systems?

Answer: Implement these validation techniques [4] [1]:

- Goodness-of-fit Testing: Perform statistical analysis (eχ²-test) to determine how well the estimated fluxes explain the experimental labeling data [4].

- Flux Confidence Intervals: Calculate confidence intervals for all estimated fluxes to quantify their precision and identifiability [4] [5].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to determine the minimum and maximum possible values for each flux within the solution space [1].

- Cross-Validation: If possible, compare flux results obtained using different tracers or analytical methods.

FAQ 5: What software tools are available for handling underdetermined systems?

Answer: Several specialized software packages support work with underdetermined networks:

Table 2: Software Tools for Underdetermined Metabolic Networks

| Software | Primary Function | Underdeterminacy Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX2 | 13C-MFA simulation and flux estimation | Flux confidence intervals, statistical analysis | [3] |

| mfapy | Python-based 13C-MFA package | Customizable flux estimation, support for trial-and-error analysis | [6] |

| EFMtool | Elementary Flux Mode calculation | Pathway analysis for underdetermined systems | [1] |

| Metatool | EFM computation | Decomposition of flux space into minimal pathways | [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) for CharacterUnderdetermined Systems

Purpose: To determine the range of possible values for each flux in an underdetermined metabolic network [1].

Materials:

- Stoichiometric matrix of the metabolic network

- Measured extracellular fluxes (if available)

- Flux analysis software (e.g., COBRA Toolbox, 13CFLUX2)

Procedure:

- Formulate the mass balance constraints: Nv = 0

- Add constraints for measured extracellular fluxes: Nmv = vm

- Apply physiological constraints (e.g., flux reversibility, enzyme capacity)

- For each flux vi in the network: a. Minimize vi subject to all constraints b. Maximize v_i subject to all constraints

- Record the minimum and maximum values for each flux

- Analyze fluxes with large ranges as key targets for additional experimental constraints

Protocol 2: Robust Tracer Design for Systems with Unknown Fluxes

Purpose: To design informative 13C-labeling experiments when prior flux knowledge is limited [3].

Materials:

- Metabolic network model in FluxML format

- 13CFLUX2 software suite

- Custom Python/Matlab scripts for evaluation

Procedure:

- Formulate the 13C-MFA model including atom transitions

- Sample the feasible flux space to represent possible flux distributions

- Evaluate different tracer mixtures using a design criterion that characterizes how informative each mixture is across all possible flux values

- Screen sampled experimental designs for best compromise solutions considering both information content and cost

- Select the tracer mixture that provides the best trade-off between informativeness and practical implementation

The workflow below illustrates this robust experimental design process.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 13C-MFA Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose) | Tracers for metabolic labeling experiments | Use multiple tracers in parallel; verify isotopic purity >99% [5] [3] |

| GC-MS instrumentation | Measurement of isotopic labeling in metabolites | Analyze protein-bound amino acids for labeling patterns [5] |

| FluxML model files | Standardized representation of metabolic networks | Use for consistent model specification across software tools [3] |

| Custom Python/Matlab scripts | Automated evaluation of flux identifiability | Implement statistical analysis and confidence interval calculation [3] |

| Cell culture media components | Defined medium for controlled labeling experiments | Avoid complex carbon sources that complicate labeling interpretation [4] |

Advanced Methodologies for Flux Determination

Most Accurate Fluxes (MAF) Approach

For researchers requiring a unique solution from an underdetermined system, the Most Accurate Fluxes (MAF) method provides a systematic algorithm [2]. This approach introduces a measure of flux accuracy and iteratively determines the fluxes with the highest possible accuracy given the available constraints. The MAF distribution has been shown to be similar to the mean values obtained from uniform sampling of admissible solutions, providing a mathematically justified single solution [2].

Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis (DMFCA)

When working with time-varying systems such as fed-batch cultures, Dynamic Metabolic Flux Analysis based on convex analysis (DMFCA) can be applied to compute the time evolution of bounded flux intervals [7]. This approach is particularly valuable for bioprocess applications where metabolic activity changes throughout the cultivation process.

Underdeterminacy is not a limitation to be overcome but rather a fundamental property of metabolic systems that must be understood and managed. By applying the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and methodologies outlined in this technical support resource, researchers can design more informative experiments, interpret their flux results with appropriate caution, and make meaningful physiological inferences even in the face of mathematical ambiguity. The continued development of robust experimental design strategies and analytical frameworks will further enhance our ability to extract biological insights from underdetermined metabolic networks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental role of the stoichiometric matrix in metabolic flux analysis?

The stoichiometric matrix (denoted as N) is the algebraic core of any metabolic model under a steady-state assumption. It mathematically represents the entire metabolic network, where each row corresponds to an intracellular metabolite and each column corresponds to a reaction [1]. The matrix entries describe the stoichiometric coefficients of each metabolite in every reaction. The fundamental equation N · v = 0 encapsulates the mass balance constraint, stating that for every intracellular metabolite, the sum of its production fluxes must equal the sum of its consumption fluxes, leaving no net accumulation [1] [8]. This equation forms the primary set of constraints that defines all possible, feasible flux distributions (the solution space) within the network.

FAQ 2: What are "degrees of freedom" (DOF) in the context of 13C-MFA, and why are they a problem? Degrees of freedom represent the number of independent variables (fluxes) that are not uniquely determined after accounting for all existing constraints (like mass balances and measured external fluxes) [1]. In simple terms, if your system has more unknowns (fluxes) than independent equations (constraints), it is underdetermined. This means there is not a single unique solution but an infinite number of flux distributions that satisfy all the constraints [1]. The number of DOF is calculated as the total number of unknown fluxes minus the number of independent constraints [1] [9]. Underdeterminacy is a central problem because it prevents the precise quantification of intracellular fluxes from external measurements alone.

FAQ 3: What is the minimum number of measurements required to resolve fluxes in an underdetermined system? In theory, you need a number of independent measurements at least equal to the degrees of freedom of the system. However, in practice, 13C-MFA utilizes isotopic labeling data, which provides a wealth of additional information. Each measured mass isotopomer fraction of an intracellular metabolite acts as a non-linear constraint that further narrows the solution space [10] [11]. Often, the rich information from 13C-labeling patterns is sufficient to reduce the feasible solution space to a single, unique flux map, even for networks that are highly underdetermined when only external flux measurements are considered [11].

FAQ 4: How can I check if my 13C-MFA model is well-determined and has a unique solution? A successful 13C-MFA result typically provides not only a set of estimated fluxes but also confidence intervals for each flux. A well-determined model is characterized by small, statistically justified confidence intervals [12] [11]. Furthermore, model validation techniques, such as the χ²-test of goodness-of-fit, are used to check whether the difference between the measured labeling data and the model-predicted labeling is statistically insignificant, indicating that the model and the estimated flux map are a good fit for the experimental data [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The model solution space is too large, leading to wide confidence intervals for estimated fluxes.

This is a classic symptom of an underdetermined system where the available data is insufficient to precisely pinpoint the intracellular fluxes.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description and Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Verify External Flux Measurements | Re-check the accuracy of your measured uptake and secretion rates (e.g., glucose, lactate, ammonia). Ensure calculations account for cell growth, evaporation, and spontaneous degradation (e.g., of glutamine) [11] [13]. Inaccurate external fluxes propagate error and enlarge the solution space. |

| 2. Optimize Tracer Selection | Not all tracers are equally informative for all pathways. If fluxes in a specific pathway (e.g., pentose phosphate pathway, reductive TCA cycle) are poorly resolved, consider switching to a tracer that provides better positional labeling information for that pathway, or use parallel labeling experiments with multiple tracers [12] [11]. |

| 3. Increase Labeling Data Points | Incorporate measurements of additional metabolite isotopologues. Using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to obtain positional (fragment) labeling data can provide more powerful constraints than overall mass isotopomer distributions alone [12]. |

| 4. Apply a Parsimony Principle | If the solution space remains large, use parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA). This method selects the flux map from the feasible solution space that minimizes the total sum of absolute fluxes, a principle often consistent with cellular economy. This can be weighted by gene expression data to favor fluxes through enzymes with higher expression [14]. |

| 5. Re-evaluate Network Topology | Ensure your metabolic network model includes all relevant reactions for your biological system. An overly simplified model that omits active pathways will be unable to fit the labeling data well, leading to a large residual error and unreliable flux estimates [12]. |

Problem: The model fails the goodness-of-fit test (e.g., high χ² value).

A poor statistical fit indicates a discrepancy between the experimental measurements and the labeling patterns simulated by the model.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description and Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Check for Measurement Outliers | Carefully scrutinize your isotopic labeling data and external flux measurements for outliers or technical errors. Even a single grossly inaccurate data point can significantly degrade the model fit [12]. |

| 2. Inspect Metabolic Steady-State | 13C-MFA assumes the system is at metabolic and isotopic steady state. For INST-MFA, ensure accurate measurement of metabolite pool sizes. For SS-MFA, verify that the labeling pattern has reached equilibrium and that cell physiology (growth, uptake rates) remains constant during the experiment [10] [11]. |

| 3. Review Atom Mapping | Incorrect atom transitions in the model will generate wrong simulated labeling patterns. Double-check the carbon atom mapping for every reaction in your network, paying special attention to complex reactions in the TCA cycle and pentose phosphate pathway [11]. |

| 4. Consider Model Extension | The poor fit may suggest the activity of an alternative pathway not included in your model (e.g., glyoxylate shunt, transketolase-like reactions, futile cycles). Explore and test alternative network architectures to see if they yield a better fit to the data [12]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential reagents and materials for 13C-MFA experiments.

| Item | Function in 13C-MFA |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine) | The core reagents that introduce a measurable pattern into metabolism. The specific labeling pattern of the tracer determines which pathways can be elucidated [11]. |

| Quenching Solution (e.g., cold aqueous methanol) | Rapidly halts all metabolic activity at the time of sampling to preserve the in vivo isotopic labeling state of metabolites [11]. |

| Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS, LC-MS) | The primary analytical instrument for quantifying the relative abundances of different mass isotopomers (M+0, M+1, M+2, etc.) in extracted metabolites [10] [11]. |

| Cell Culture Media (custom, tracer-compatible) | A defined medium without unaccounted carbon sources that could dilute the label and complicate the analysis. It serves as the vehicle for the tracer [11]. |

| Software Platforms (e.g., INCA, Metran, Iso2Flux) | User-friendly tools that implement the computational machinery of 13C-MFA, including the EMU framework, non-linear parameter fitting, and statistical analysis [11] [14]. |

| A-385358 | A-385358, MF:C32H41N5O5S2, MW:639.8 g/mol |

| Abarelix Acetate | Abarelix Acetate|GnRH Antagonist |

Workflow Visualization

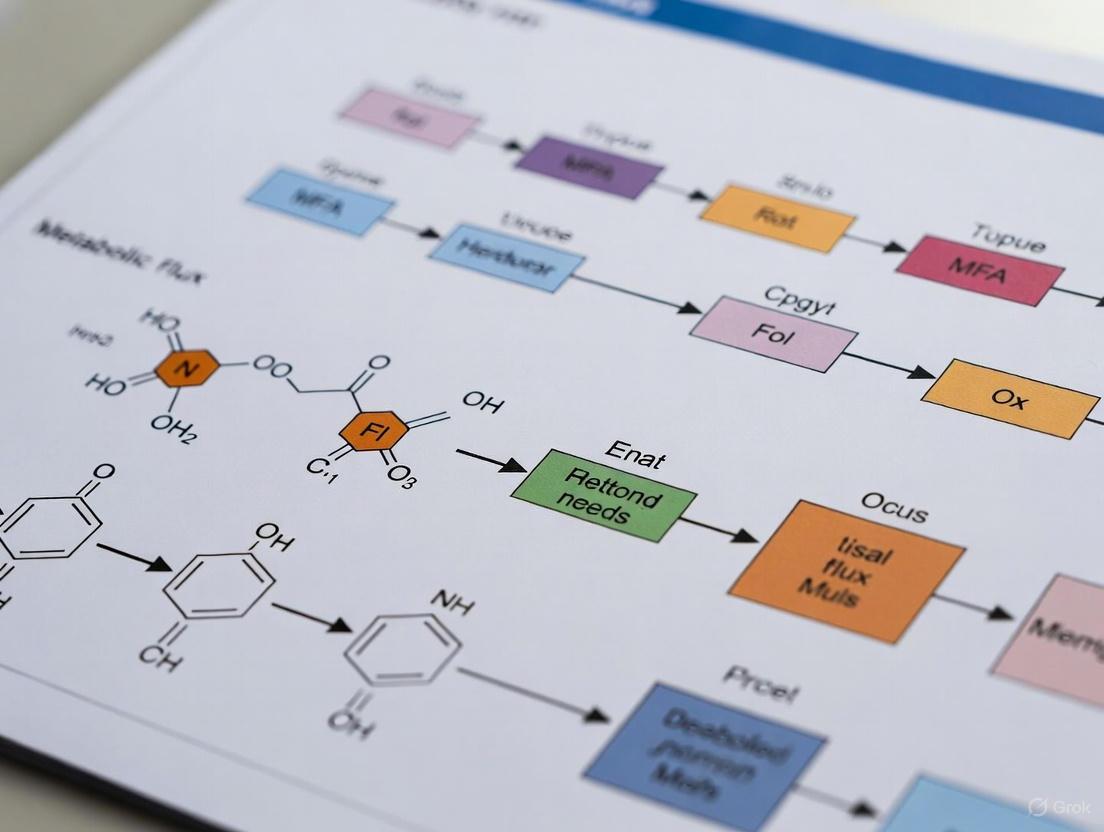

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving the core problem of underdeterminacy in 13C-MFA, linking the stoichiometric matrix, degrees of freedom, and solution strategies.

Diagram: A workflow for diagnosing and resolving underdeterminacy in 13C-MFA.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining External Fluxes for Exponentially Growing Cells

Accurate external flux measurements are critical constraints that directly reduce the degrees of freedom in the model.

- Cell Culture and Sampling: Culture cells in a defined medium. Record the exact culture volume (V, in mL). At two or more time points (t1, t2), take a sample and perform two actions simultaneously:

- Calculate Growth Rate (µ): Plot the natural logarithm of the cell number (ln Nx) versus time. The growth rate µ (1/h) is the slope of the resulting line. For two time points, use:

- Calculate External Fluxes (ri): For each metabolite i, calculate the external flux using the formula for exponentially growing cells:

- Apply Necessary Corrections:

- Glutamine Degradation: Correct the apparent glutamine uptake rate for spontaneous degradation (using a first-order degradation constant of ~0.003/h) to obtain the true net uptake rate [11] [13].

- Evaporation: For long-term experiments, run a control without cells to estimate evaporation rates and correct concentrations accordingly [11].

Table: Example calculation of a glucose uptake rate.

| Parameter | Value at t1 (24h) | Value at t2 (48h) | Change (Δt=24h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Number (million) | 1.0 | 3.5 | ΔNx = 2.5 |

| Glucose Concentration (mM) | 25.0 | 10.2 | ΔC = -14.8 mM |

| Culture Volume (mL) | 10 | 10 | V = 10 mL |

| Growth Rate (µ) | (ln(3.5) - ln(1.0)) / 24 = 0.052 /h |

||

| Glucose Uptake Rate (r_glc) | 1000 * (0.052 * 10 * -14.8) / 2.5 ≈ -307 nmol/10^6 cells/h |

FAQ: Understanding the Core Problem

What is underdeterminacy in metabolic flux analysis? Underdeterminacy occurs when a metabolic system has more unknown fluxes than available mass balance equations to constrain them [15] [1]. This means that infinitely many flux distributions can perfectly fit the same experimental data, posing a significant challenge for obtaining a unique, biologically correct solution [15].

Why is underdeterminacy a critical problem for biomedical researchers? A model that appears accurate for one dataset may fail dramatically under different conditions [15]. In drug development or when engineering metabolic pathways, an incorrect flux model can lead to the identification of poor therapeutic targets or inefficient bioproduction strains [12]. Relying on a single, potentially non-unique solution without assessing uncertainty can lead to incorrect biological conclusions and wasted resources.

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Underdeterminacy

Problem: My flux solution is not unique. How can I reduce the degrees of freedom? Solution: Systematically add biologically reasonable constraints to reduce the feasible solution space.

- Method 1: Integrate Additional Experimental Data

- 13C Tracer Experiments: Use stable-isotope tracing (e.g., with 13C-labeled glucose or glutamine) to generate intracellular labeling data. This provides additional information that drastically reduces the space of possible fluxes [11] [12].

- Measure External Rates: Precisely quantify nutrient uptake and waste secretion rates, as these provide critical boundary constraints [11] [1]. The methodology is outlined in the table below.

Table: Key External Rates for Constraining Flux Models in Proliferating Cells

| External Rate | Typical Range (nmol/10^6 cells/h) | Function as a Constraint |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose Uptake | 100 - 400 | Constrains upper bound of glycolytic and TCA cycle fluxes |

| Lactate Secretion | 200 - 700 | Indicates glycolytic and Warburg effect activity |

| Glutamine Uptake | 30 - 100 | Constrains nitrogen metabolism and anaplerotic fluxes |

- Method 2: Apply Computational and Theoretical Constraints

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Assume the cell optimizes an objective (e.g., growth rate) to select a single flux distribution from the feasible set [1] [16].

- Thermodynamic Constraints: Incorporate knowledge of reaction reversibility/irreversibility to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible cycles [1].

- Stepwise Inference: Use algorithms that iteratively reduce degrees of freedom by identifying the most likely flux profiles in a statistical sense [15].

Problem: How do I know if my flux estimates are reliable? Solution: Quantify the uncertainty of your flux estimates.

- Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): For each reaction, calculate the minimum and maximum possible flux it can carry while still satisfying all model constraints and optimality objectives. This reveals which fluxes are well-determined and which have large ranges of uncertainty [1].

- Use Statistical Sampling: Sample the space of all possible flux distributions to build a probability distribution for each flux. The standard deviation of this distribution provides a confidence interval for your estimate [17] [18]. The workflow below visualizes this process.

Problem: I have a candidate flux solution. How can I validate it? Solution: Use model validation and selection techniques.

- Goodness-of-fit Test: In 13C-MFA, a χ2-test is commonly used to compare the fit between the model-predicted and experimentally measured isotopic labeling patterns. A good fit suggests the model is consistent with the data [12].

- Incorporate Metabolite Pool Sizes: When using Isotopically Nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA), including measurements of intracellular metabolite concentrations (pool sizes) during the fitting process provides a more robust validation [12].

- Compare Against Independent Data: Validate your flux predictions against data not used in the model fitting, such as enzyme knockout phenotypes or gene expression data [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Software for 13C-MFA

| Item | Function / Explanation | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C]Glucose | Tracer to elucidate glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathway fluxes [11]. | Different labeling positions (e.g., [1-13C], [U-13C]) probe different pathways. |

| 13C-Glutamine | Tracer to analyze TCA cycle and reductive metabolism [11]. | Correct for spontaneous degradation in culture medium for accurate uptake rates [11]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS, LC-MS) | Measures the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of metabolites from tracer experiments [11] [12]. | Tandem MS provides higher resolution for positional labeling. |

| User-Friendly 13C-MFA Software (INCA, Metran) | Software tools that convert isotopic labeling data into flux maps using the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework [11]. | Designed for accessibility to researchers without deep computational backgrounds. |

| Flux Sampling Software | Generates a distribution of possible fluxes to quantify uncertainty [17] [18]. | Essential for understanding the reliability of predictions in underdetermined systems. |

| Ac-DEVD-pNA | Ac-DEVD-pNA, CAS:189950-66-1, MF:C26H34N6O13, MW:638.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Acemetacin | Acemetacin, CAS:53164-05-9, MF:C21H18ClNO6, MW:415.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: Core 13C-MFA Workflow

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for a foundational 13C-MFA experiment to estimate intracellular fluxes.

1. Experimental Design and Setup

- Cell Culture: Use exponentially growing cells to approximate metabolic steady-state [11].

- Tracer Selection: Choose a tracer that best differentiates the pathways of interest (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose to resolve pentose phosphate pathway activity) [11].

- Labeling Experiment: Replace the standard growth medium with an identical medium containing the 13C-labeled substrate. Ensure adequate duration for the labeling to reach isotopic steady-state in central metabolites (typically 12-24 hours, but must be optimized).

2. Data Collection

- External Rates:

- Sample the culture medium at multiple time points.

- Measure concentrations of key metabolites (glucose, lactate, glutamine, etc.) using standard biochemical assays or HPLC.

- Count cell numbers to determine the growth rate (µ) using the formula:

µ = (ln(Nx,t2) - ln(Nx,t1)) / Δt[11]. - Calculate nutrient uptake and product secretion rates (ri) in nmol/10^6 cells/h using:

ri = 1000 * µ * V * ΔCi / ΔNx[11].

- Isotopic Labeling:

3. Computational Flux Analysis

- Model Construction: Define a stoichiometric model of the metabolic network, including atom transitions.

- Data Integration: Input the measured external rates and MIDs into 13C-MFA software (e.g., INCA) [11].

- Parameter Estimation: Solve the least-squares optimization problem to find the flux map that minimizes the difference between simulated and measured MIDs [11] [12].

- Uncertainty Analysis: Perform statistical sampling or profiling to compute confidence intervals for each estimated flux [17] [12].

The logical flow of this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My 13C-MFA solution space is too large to identify a unique flux distribution. How can I reduce it? A large solution space, or underdetermined system, is common when the number of unknown reactions exceeds the available labeling data [14]. You can reduce it by:

- Applying the Parsimony Principle: Run a secondary optimization that selects the flux distribution minimizing the total sum of absolute reaction fluxes within the 13C-MFA solution space. This is the core of the p13CMFA approach [14].

- Integrating Transcriptomic Data: Weight the flux minimization by gene expression evidence. This penalizes fluxes through reactions with low gene expression, steering the solution toward biologically relevant values [14].

- Incorporating Additional Experimental Constraints: Use measured extracellular rates (e.g., nutrient uptake, secretion rates) and growth rates to provide boundary constraints that further narrow the solution space [11].

FAQ 2: My Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) model has become infeasible after integrating measured flux values. What should I do? Infeasibility occurs when the measured fluxes violate model constraints like mass balance or reaction reversibility [19]. To resolve this:

- Identify the Core Conflict: Use linear programming (LP) or quadratic programming (QP) methods to find the minimal corrections required for your measured flux values to make the FBA problem feasible again [19].

- Check Reaction Directionality: Ensure that fixed fluxes for irreversible reactions are not set to a value that violates their thermodynamic constraints [19].

- Review Steady-State Assumptions: Verify that the measured fluxes are consistent with the steady-state mass balance assumption for internal metabolites [19].

FAQ 3: How can I validate if my metabolic model is a good fit for the experimental data? Beyond detecting gross measurement errors, you can assess model fit statistically.

- Employ a Generalized Least Squares (GLS) Framework: Formulate the MFA as a GLS problem. This allows you to use a t-test to check if each calculated flux is significantly different from zero [20].

- Simulate for Significance: Generate ideal flux profiles from your model, perturb them with estimated measurement error, and then re-calculate the fluxes. Comparing the significance of fluxes from this ideal data to your real data helps differentiate between measurement error and a poor model fit [20].

FAQ 4: What are the advantages of using Bayesian methods for 13C-MFA? Bayesian 13C-MFA offers several advantages over conventional best-fit approaches:

- Handles Model Uncertainty: It allows for multi-model inference, so you don't have to rely on a single model. Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) weights the evidence from multiple plausible models, providing a more robust flux inference [21].

- Quantifies Uncertainty Naturally: It provides full probability distributions for the estimated fluxes, giving a complete picture of the uncertainty associated with each prediction [21].

- Tests Bidirectional Reactions: The framework makes it statistically testable whether a reaction step is bidirectional or unidirectional [21].

FAQ 5: What is the fundamental geometric representation of the flux solution space? The space of all feasible flux distributions that satisfy the mass-balance (steady-state) and thermodynamic constraints forms a convex polytope [22].

- H-representation: The polytope is defined by a set of linear inequalities (e.g., ( A^{\ddagger}v \leq b^{\ddagger} )) derived from stoichiometry and flux bounds [22].

- V-representation: The same polytope can be described by its set of vertices ( ( V^{\ddagger} ) ), which correspond to elementary flux modes. Any feasible flux distribution can be represented as a convex combination of these vertices [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Underdetermined System in 13C-MFA Symptoms: A wide range of flux values provide a similarly good fit to your isotopic labeling data, leading to high uncertainty in flux estimates. Solution: Apply Parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA).

| Step | Action | Technical Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perform Standard 13C-MFA | Identify the set of all flux distributions that fit the labeling data within a defined statistical threshold [14]. | ||

| 2 | Define the Objective Function | Minimize the total weighted sum of absolute fluxes: ( \sum w_i | v_i | ). If gene expression data is available, use it to set the weights ( w_i ) [14]. |

| 3 | Run Secondary Optimization | Solve the linear programming problem to find the flux distribution within the feasible set that minimizes the objective function [14]. |

Problem: Infeasible FBA Scenario Symptoms: The FBA solver returns an "infeasible" error after constraining reactions with measured flux values. Solution: Find minimal flux corrections to restore feasibility.

| Step | Action | Technical Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Formulate the Infeasible Problem | The problem is: find ( v ) such that ( Nv = 0 ), ( lb \leq v \leq ub ), and ( vi = fi ) for ( i \in F ), which has no solution [19]. | ||

| 2 | Set Up the Correction Model | Introduce a correction variable ( \deltai ) for each fixed flux. The new constraint becomes ( vi = fi + \deltai ) [19]. | ||

| 3 | Solve the Optimization | Minimize ( \sum | \delta_i | ) (LP) or ( \sum \delta_i^2 ) (QP) subject to the mass balance and bound constraints. The solution gives the smallest adjustments to your measurements that make the model feasible [19]. |

Problem: Lack of Model Fit in MFA Symptoms: Calculated fluxes are not statistically significant, or confidence intervals are unreasonably large. Solution: Implement a statistical validation protocol.

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Formulate as Regression | Frame the MFA as ( -So vo = Sc vc + \varepsilon ), where ( \varepsilon ) is the residual [20]. |

| 2 | Estimate Covariance | Estimate the variance-covariance matrix ( \text{Cov}(\varepsilon) ) from measurement uncertainties [20]. |

| 3 | Compute t-statistics | For each calculated flux ( v{c,i} ), compute its t-statistic: ( ti = \frac{\hat{v}{c,i}}{\text{SE}(\hat{v}{c,i})} ), where SE is the standard error [20]. |

| 4 | Interpret Results | Fluxes with a t-statistic below the critical value (e.g., < 2) are not statistically significant and may indicate a problem with the model's structure for those pathways [20]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the process for validating flux models using the t-test approach:

Workflow for Flux Model Validation

Comparative Analysis of MFA Methods

The table below summarizes key quantitative and methodological aspects of different flux analysis approaches to guide method selection.

| Method | Key Principle | Applicable Scene | Computational Complexity | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Fluxomics (Isotope Tracing) [10] | Deduce pathway activity by comparing isotopic labeling patterns. | Any system. | Easy. | Provides only local and qualitative flux information. |

| 13C Metabolic Flux Ratios [10] | Calculate relative flux fractions at metabolic branch points from isotopic patterns. | Systems where fluxes and labeling are constant. | Medium. | Provides only local and relative quantitative values. |

| Stationary State 13C-MFA [10] | Optimize fluxes to fit isotopic labeling data at isotopic steady state. | Systems where fluxes, metabolites, and their labeling are constant. | Medium. | Not applicable to dynamic or transient systems. |

| Parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA) [14] | Selects the flux solution with the minimal sum of absolute fluxes from the 13C-MFA feasible set. | Underdetermined systems where 13C-MFA yields a wide solution space. | Medium. | Relies on the biological assumption of flux parsimony. |

| Bayesian 13C-MFA [21] | Uses Bayesian inference to compute posterior probability distributions of fluxes. | Any 13C-MFA scenario, especially when model uncertainty is high. | High. | Computationally intensive; requires familiarity with Bayesian statistics. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational and methodological tools for advanced flux analysis.

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) Framework [10] [11] | A computational framework that dramatically simplifies the simulation of isotopic labeling in large metabolic networks. | Essential for efficiently calculating the labeling patterns of metabolites in any arbitrary biochemical network model during 13C-MFA. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) [16] [20] | A mathematical matrix where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. The core of all constraint-based modeling. | Used to enforce mass-balance constraints (( S \cdot v = 0 )) in both FBA and MFA, defining the space of possible flux distributions. |

| Isotopically Instationary MFA (INST-MFA) [10] | A variant of 13C-MFA that analyzes transient labeling patterns before isotopic steady state is reached. | Used for measuring fluxes in systems with very fast metabolic dynamics or for probing fluxes in specific metabolite pools. |

| Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) [23] | Weights that quantify each reaction's contribution to a cellular objective function in FBA. | In the TIObjFind framework, CoIs are used to identify the objective function that best aligns FBA predictions with experimental flux data. |

| Linear & Quadratic Programming (LP/QP) [16] [19] | Optimization techniques used to solve FBA problems and resolve infeasible scenarios. | LP is used for standard FBA (e.g., growth maximization). QP can be used to find minimal least-squares corrections for infeasible flux measurements. |

| Actarit | Actarit, CAS:18699-02-0, MF:C10H11NO3, MW:193.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Actinonin | Actinonin, CAS:13434-13-4, MF:C19H35N3O5, MW:385.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The following diagram illustrates the Bayesian Model Averaging process, a robust approach to flux inference that accounts for model uncertainty.

Bayesian Model Averaging for Flux Inference

Computational and Experimental Strategies to Constrain Flux Solutions

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does it mean for a metabolic system to be "underdetermined," and how do extracellular measurements help? An underdetermined system is one where the number of unknown intracellular fluxes exceeds the number of available mass balance equations, leading to a range of possible flux solutions rather than a single, unique answer [1]. Integrating extracellular rate measurements (e.g., substrate uptake or product excretion rates) adds crucial equality constraints to the stoichiometric model. This significantly reduces the space of feasible flux solutions, bringing the analysis closer to a unique determination of the intracellular flux map [1].

2. Which extracellular rates are most critical to measure for constraining central carbon metabolism? The most critical measurements are the uptake rates of carbon sources (e.g., glucose, glutamine) and the production rates of major metabolites such as lactate, ammonia, and carbon dioxide. Additionally, the specific growth rate of the cells is essential, as it defines the drain of metabolites into biomass precursors [4]. Accurate measurement of these rates provides the foundation for applying stoichiometric constraints.

3. My model is still underdetermined after adding all available extracellular measurements. What are my options? This is a common scenario. Your options include:

- Conduct Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): This method computes the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction within the constrained solution space, identifying which fluxes are well-determined and which remain uncertain [1].

- Apply a Parsimony Principle: Techniques like parsimonious FBA (pFBA) or parsimonious 13C MFA (p13CMFA) can be used. These methods find the flux distribution that fits the data while minimizing the total sum of absolute fluxes, which often reflects a biologically efficient state [24] [14].

- Integrate 13C Labeling Data: 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) uses isotopic tracer data to provide additional, highly specific constraints on intracellular reaction pathways, further narrowing the solution space [24] [12].

4. How can I validate that my extracellular measurements are sufficient and accurate?

- Check Carbon and Electron Balances: Perform a carbon and (if possible) electron balance check. A significant imbalance (e.g., >10%) often indicates missing measurements, inaccurate assays, or the presence of unmeasured byproducts [4].

- Goodness-of-Fit Test: In 13C-MFA, a chi-squared (χ²) goodness-of-fit test is used to evaluate whether the differences between the experimental measurements and the model's predictions are statistically acceptable [12] [4].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Analyze how sensitive your key flux predictions are to small variations in your extracellular measurements. If fluxes change dramatically, those measurements are highly influential and their accuracy is critical [25].

# Troubleshooting Guides

### Problem 1: Implausibly High or Infinite Flux Ranges in FVA

Issue: After integrating extracellular measurements and performing Flux Variability Analysis (FVA), some reactions show extremely wide or even infinite flux ranges, indicating the system is poorly constrained.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check Constraints | The stoichiometric constraints and extracellular measurements are insufficient to bound the flux for particular network cycles or pathways. | Add all available exchange flux measurements (e.g., secretion of acetate, succinate, etc.). Review literature for known thermodynamic constraints (irreversible reactions) and apply them as flux bounds [1]. |

| 2. Identify Futile Cycles | The network may contain thermodynamically infeasible cycles (futile cycles) that can carry flux without a net change in metabolites. | Apply additional thermodynamic constraints to prevent these infeasible loops [1]. Tools like NetworkReduce can systematically detect and remove such cycles. |

| 3. Apply Parsimony | The solution space contains flux distributions with unnecessarily high total flux. | Implement a parsimonious constraint. First, find the solution that fits your data with the minimum sum of absolute fluxes (pFBA). Then, perform FVA within a small tolerance of this optimal parsimonious solution [24] [1]. |

### Problem 2: Poor Goodness-of-Fit in 13C-MFA

Issue: The metabolic model, after integration with extracellular fluxes, fails the χ² goodness-of-fit test when fitting 13C-labeling data, indicating a mismatch between the model and experimental measurements [12].

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Verify Measurement Accuracy | Inaccurate extracellular flux or 13C-labeling data can cause a poor fit. | Re-check the standard deviations of all measurements. Ensure raw mass isotopomer distributions are properly corrected for natural isotope abundances [4]. |

| 2. Inspect Model Completeness | The stoichiometric model may be missing key reactions or contain incorrect atom transitions. | Verify the atom mapping for all reactions, especially less common ones. Check if an alternative nutrient (e.g., glutamine) is contributing significantly to biomass and should be included as a labeled input [4]. |

| 3. Evaluate Model Overfitting | The model might be too complex for the available dataset, or a simpler model might be more appropriate. | Use statistical model selection techniques. Compare the fit of different model variants (e.g., with/without a specific pathway) using criteria like the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Model Averaging [12] [21]. |

### Problem 3: Failure to Achieve a Carbon Balance

Issue: The measured carbon inputs (from substrates) do not match the measured carbon outputs (in products, biomass, and COâ‚‚), suggesting missing data.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify Major Missing Outputs | Common byproducts like acetate, ethanol, or secreted amino acids are often not measured. | Review the metabolic capabilities of your organism. Implement assays for common fermentation products or use extracellular metabolomics to profile the medium [4]. |

| 2. Account for Biomass | The biomass composition and its associated carbon drain may be inaccurately defined. | Use a detailed, experimentally determined biomass equation specific to your organism and growth conditions. Ensure the growth rate measurement is accurate [4]. |

| 3. Check for Evasive Products | Gaseous products other than COâ‚‚ (e.g., Hâ‚‚) or volatile compounds (e.g., ketones) may be unaccounted for. | Consult literature on the organism's metabolism. If suspected, implement headspace analysis or specific sensors for these volatile compounds. |

# Experimental Protocols

### Protocol 1: Quantifying Key Extracellular Metabolites

Objective: To accurately measure the uptake and secretion rates of major metabolites to constrain the stoichiometric model.

Materials:

- Cell culture supernatant from timed samples.

- HPLC system with UV/RI detector or a similar analytical platform (e.g., GC-MS).

- Standards for metabolites (e.g., glucose, lactate, glutamine, ammonia, amino acids).

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Collect culture supernatant at multiple time points during steady-state growth (e.g., in chemostat or mid-exponential batch culture). Immediately filter (0.2 µm) and freeze at -80°C.

- Instrument Calibration: Prepare a standard curve for each metabolite of interest using known concentrations.

- Analysis: Run samples and standards on the HPLC/GC-MS. Quantify metabolite concentrations by comparing peak areas to the standard curve.

- Rate Calculation: Plot concentration against time. The specific consumption/production rate (mmol/gDW/h) is calculated from the slope of the linear regression, the culture volume, and the cell dry weight (gDW) [4].

### Protocol 2: Implementing Parsimonious Flux Analysis

Objective: To find the most efficient flux distribution that fits the extracellular measurements by minimizing the total flux.

Methodology: This is a two-step optimization process [24] [14]:

- Primary Optimization (Standard FBA): Solve the FBA problem to find the optimal objective (e.g., growth rate) given the stoichiometric and extracellular flux constraints.

- Mathematical Formulation:

Maximize: c^T * vsubject toS * v = 0andlb ≤ v ≤ ub, wherevis the flux vector,Sis the stoichiometric matrix, andcis the objective vector.

- Mathematical Formulation:

- Secondary Optimization (Flux Minimization): Fix the primary objective to its optimal value and solve a second optimization problem that minimizes the sum of absolute fluxes.

- Mathematical Formulation:

Minimize: Σ |v_i|subject toS * v = 0,lb ≤ v ≤ ub, andc^T * v = Z_opt, whereZ_optis the optimal objective from step 1 [24].

- Mathematical Formulation:

Software Tools: This protocol can be implemented using COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB or with Python packages like COBRApy.

# Workflow Visualization

### Logical Workflow for Constraining Fluxes

# Research Reagent Solutions

The following materials are essential for successfully implementing this strategy.

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Strategy |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose) | Serves as isotopic tracers in 13C-MFA; the pattern of label propagation provides extra constraints on internal pathway fluxes [26] [25]. |

| Stoichiometric Model (in SBML/FluxML format) | A computational representation of the metabolic network, defining the S matrix for mass balance constraints [26] [4]. |

| COBRA Toolbox / 13CFLUX2 | Software suites used to set up constraints, perform FVA, FBA, and 13C-MFA simulations, and conduct statistical analysis [24] [25]. |

| HPLC / GC-MS Platform | Essential analytical equipment for accurately quantifying the concentrations of extracellular metabolites in the culture medium to calculate uptake/secretion rates [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary cause of underdetermined flux distributions in 13C-MFA? Underdetermined flux distributions occur when the available experimental data and constraints are insufficient to define a unique solution for all intracellular metabolic fluxes. This is common because the system of stoichiometric equations is often larger than the number of measured fluxes and labeling data points. The solution space includes a range of feasible flux values rather than a single, unique set [1].

FAQ 2: How can I reduce underdeterminacy in my 13C-MFA study? Underdeterminacy can be reduced by:

- Increasing measurement constraints: Using parallel labeling experiments with multiple tracers provides more labeling data to constrain the system [14] [1].

- Integrating other data types: Incorporating additional data, such as transcriptomics data, can help constrain the solution space [14].

- Applying advanced statistical methods: Techniques like Bayesian Model Averaging or parsimonious 13C-MFA can help select a biologically relevant solution from the set of possible fluxes [21] [14].

FAQ 3: Why is correcting for natural abundance critical, and what are the best methods? Natural abundance of heavy isotopes (e.g., 1.1% for 13C) contributes to the measured mass isotopomer distribution. If not accurately corrected, this leads to significant errors in the calculated isotopic enrichment and subsequent flux estimates [27]. The "skewed" correction method or using modern software tools like ElemCor, which accounts for high-resolution mass spectrometry data, is recommended over outdated "classical" methods [27] [28].

FAQ 4: What is the difference between metabolic steady state and isotopic steady state?

- Metabolic steady state: Intracellular metabolite levels and metabolic fluxes are constant over time [29].

- Isotopic steady state: The 13C enrichment in metabolites no longer changes over time [29]. For straightforward interpretation of labeling data, the biological system should be at a metabolic pseudo-steady state, and the tracer experiment must be long enough for the relevant metabolites to reach isotopic steady state [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Non-Unique or Physiologically Implausible Flux Solutions

Symptoms: The flux estimation software returns a wide range of possible values for many fluxes, or the best-fit solution suggests flux through a pathway that is not supported by other biological evidence.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description and Action |

|---|---|

| Verify Data Quality | Ensure the accuracy of measured external rates (e.g., nutrient uptake, by-product secretion) and labeling patterns. Inaccurate data is a major source of ill-constrained solutions [13] [11]. |

| Use Multiple Tracers | Employ a set of complementary tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine). Different tracers illuminate different pathways, collectively providing more comprehensive constraints [14] [1]. |

| Apply Flux Minimization | Use parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA). This approach selects the flux solution that minimizes the total sum of fluxes from the set of solutions that fit the labeling data equally well, often yielding more physiologically relevant results [14]. |

| Integrate Omics Data | Weigh the flux minimization by gene expression data. This penalizes fluxes through enzymes with low gene expression, further steering the solution toward biological relevance [14]. |

| Adopt Bayesian Methods | Use Bayesian 13C-MFA. This framework does not rely on a single model but performs multi-model inference, providing a robust flux estimation that accounts for model uncertainty [21]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for tackling this problem.

Problem 2: Inaccurate Correction for Natural Abundance

Symptoms: Corrected mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) do not match expected patterns, leading to poor model fits and unreliable flux estimates, even when using high-resolution mass spectrometry data.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description and Action |

|---|---|

| Identify Correction Method | Review the correction method used. Avoid the outdated "classical" method. Use the correct "skewed" method or matrix-based approaches [27]. |

| Account for Derivatization | If using GC-MS, ensure the correction algorithm accounts for all atoms introduced during the chemical derivatization of metabolites [29]. |

| Use High-Resolution Tools | For high-resolution LC-MS data, use specialized software like ElemCor. It uses Mass Difference Theory (MDT) or Unlabeled Sample (ULS) data to perform resolution-dependent corrections, significantly improving accuracy [28]. |

| Validate with Unlabeled Samples | Run unlabeled control samples. The corrected MIDs for these samples should show negligible enrichment (e.g., M+0 ~100%). This serves as a quality control for the correction process [28]. |

Problem 3: Failure to Reach Isotopic Steady State

Symptoms: Labeling patterns for key metabolites (especially amino acids) continue to change over the duration of the tracer experiment, making data interpretation difficult.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description and Action |

|---|---|

| Confirm Metabolic Steady State | Ensure cells are in a metabolic pseudo-steady state (e.g., exponential growth phase with non-limiting nutrients) before and during the tracer experiment [29] [11]. |

| Optimize Experiment Duration | Perform a time-course experiment to track labeling in key metabolites (e.g., TCA cycle intermediates, amino acids). The experiment duration should be based on the time required for the slowest-metabolizing pool of interest to reach isotopic steady state [29]. |

| Check Media Composition | Be aware that amino acids present in the culture media can rapidly exchange with intracellular pools, preventing the intracellular pool from ever reaching full isotopic steady state. For these metabolites, quantitative, formal modeling approaches are required instead of simple intuitive interpretation [29]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and computational tools for conducting robust 13C tracer experiments.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Substrates with specific carbon atoms replaced with 13C (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine) to trace metabolic pathways [13] [29]. |

| Mass Spectrometry Instrumentation | Analytical equipment (e.g., GC-MS, LC-MS) to measure the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of metabolites, providing the primary data for flux calculation [13] [27]. |

| Natural Abundance Correction Software | Tools like ElemCor to accurately remove the spectral contribution from natural isotopes, which is critical for correct MID determination [28]. |

| 13C-MFA Software Platforms | Computational tools such as INCA, Metran, and Iso2Flux that integrate external rates and labeling data to estimate intracellular metabolic fluxes [13] [14] [28]. |

Experimental Workflow for Robust Flux Determination

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow, from experimental design to flux calculation, incorporating strategies to handle underdeterminacy.

The Challenge of Underdetermined Flux Distributions

A fundamental challenge in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is system underdeterminacy, where the algebraic system formed by steady-state mass balance equations does not define a unique solution for intracellular flux distributions. Instead, it defines a set of solutions belonging to a convex polytope [1]. This underdeterminacy arises because metabolic networks typically contain more reactions than metabolites, creating degrees of freedom that cannot be resolved with single tracer experiments alone [1] [19].

What are Parallel Labeling Experiments?

Parallel labeling experiments represent an advanced 13C-MFA approach where multiple labeling experiments are conducted under identical biological conditions but with different isotopic tracers [30]. This methodology, termed COMPLETE-MFA (Complementary Parallel Labeling Experiments Technique for Metabolic Flux Analysis), has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome underdeterminacy by providing complementary information that collectively constrains the flux solution space [31].

Table: Comparison of Single Tracer vs. Parallel Labeling Approaches

| Aspect | Single Tracer Experiment | Parallel Labeling Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Flux Precision | Limited, especially for exchange fluxes | Significantly improved for overall network |

| Flux Observability | Partial resolution of independent fluxes | More independent fluxes resolved |

| Tracer Coverage | Optimal for specific pathway sections | Comprehensive network coverage |

| Experimental Complexity | Lower | Higher, but with greatly enhanced information |

| Computational Requirements | Standard | Increased, but manageable with modern tools |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Design

COMPLETE-MFA Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for implementing parallel labeling experiments:

Tracer Selection Strategies

Selecting optimal tracers is crucial for successful parallel labeling experiments. Research demonstrates that no single optimal tracer exists for resolving all fluxes in a metabolic network [31] [32]. Tracers that produce well-resolved fluxes in upper metabolism (glycolysis, PPP) often show poor performance for lower metabolism (TCA cycle), and vice versa [31].

Table: Performance of Selected Glucose Tracers in Different Metabolic Regions

| Tracer | Upper Metabolism Performance | Lower Metabolism Performance | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C]Glucose | High | Moderate | Optimal for parallel experiments, doubly labeled [32] |

| [1,6-13C]Glucose | High | High | Best single tracer, 20x improvement over reference [32] |

| 75% [1-13C]Glucose + 25% [U-13C]Glucose | Best for upper metabolism | Poor | Optimal mixture for glycolysis and PPP [31] |

| [4,5,6-13C]Glucose | Poor | Best for lower metabolism | Optimal for TCA cycle and anaplerotic reactions [31] |

| [5-13C]Glucose | Poor | Best for lower metabolism | Optimal for TCA cycle resolution [31] |

Precision and Synergy Scoring

A key advancement in parallel labeling experimental design is the development of quantitative scoring systems [32]:

Precision Score Formula:

Where:

- P = Overall precision score

- n = Number of fluxes of interest

- UB95,ref and LB95,ref = 95% confidence intervals for reference tracer

- UB95,exp and LB95,exp = 95% confidence intervals for experimental tracer

Synergy Score Formula:

This score quantifies the benefit of conducting tracer experiments in parallel rather than individually [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Parallel Labeling Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specifications | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Glucose Tracers | [1,2-13C]glucose (99.8%), [1,6-13C]glucose (99.2%), [4,5,6-13C]glucose (99.9%) [31] [32] | Carbon source with specific labeling patterns to probe different metabolic pathways |

| Culture Medium | M9 minimal medium [31] | Defined growth medium ensuring tracer is sole carbon source |

| Mass Spectrometry Derivatization Agents | TBDMS or BSTFA [33] | Rendering molecules volatile for GC-MS analysis |

| Strain | Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 [31] | Model organism with well-characterized metabolism |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS systems [33] | Measuring isotopic labeling patterns in metabolites |

| Software Tools | 13CFLUX2, Metran, INCA, OpenFLUX2 [33] | Computational flux analysis and data integration |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How many parallel experiments are typically needed for sufficient flux resolution?

Answer: The number of parallel experiments depends on network complexity and desired flux precision. Most studies use 2-4 parallel experiments, though comprehensive studies have successfully integrated up to 14 parallel labeling experiments [31]. The key is selecting truly complementary tracers rather than maximizing quantity. Begin with 2-3 optimally chosen tracers targeting different network regions, then assess if additional experiments are needed for specific flux uncertainties.

FAQ 2: How do we address biological variability between parallel cultures?

Answer: Implement strict standardization protocols:

- Use the same seed culture for all parallel experiments [30]

- Maintain identical growth conditions (temperature, pH, aeration)

- Control for equivalent growth phases at sampling time

- For microbial systems, use mini-bioreactors with controlled aeration (e.g., 5 mL/min air flow) [31]

- Monitor growth parameters (OD600) and convert to consistent cell dry weight measurements

FAQ 3: What computational approaches best integrate data from parallel experiments?

Answer: Employ integrated data analysis where labeling data from all experiments are simultaneously fitted to a single metabolic model [31] [30]. This approach:

- Improves both flux precision and observability

- Resolves more independent fluxes with smaller confidence intervals

- Particularly enhances estimation of exchange fluxes, which are notoriously difficult with single tracers

- Uses nonlinear optimization to minimize differences between simulated and measured isotopologue distributions across all experiments

FAQ 4: How do we validate that our parallel labeling strategy has successfully resolved underdeterminacy?

Answer: Implement these validation strategies:

- Calculate nonlinear confidence intervals for all estimated fluxes [32]

- Perform statistical tests (chi-square test) for model goodness-of-fit

- Use precision scores to quantify improvement over single tracer approaches [32]

- Check if previously unobservable fluxes now have finite confidence intervals

- Validate with theoretical simulations before experimental implementation

FAQ 5: What are common pitfalls in tracer selection for parallel experiments?

Answer: Avoid these common mistakes:

- Selecting tracers with redundant information content (poor synergy)

- Neglecting cost-benefit analysis - some moderately performing tracers offer better value

- Over-optimizing for specific fluxes at the expense of global resolution

- Ignoring commercial availability and purity of proposed tracers

- Failing to consider the specific biological system and its dominant metabolic pathways

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Bayesian Approaches for Flux Inference

Recent advancements include Bayesian 13C-MFA, which provides several advantages for parallel labeling studies:

- Unifies data and model selection uncertainty in a single framework

- Enables multi-model flux inference for robust conclusions

- Enables statistical testing of bidirectional reaction steps [21]

- Bayesian Model Averaging helps overcome model selection uncertainty [21]

Parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA)

The p13CMFA approach addresses situations where 13C measurements alone cannot fully constrain the flux solution space:

- Runs secondary optimization in the 13C-MFA solution space

- Identifies solutions that minimize total reaction flux while maintaining fit to experimental data

- Can be weighted by gene expression data for biological relevance [24]

- Particularly valuable for large metabolic networks or limited measurement sets

Integration with Other Constraints

The flux resolution from parallel labeling can be further enhanced by incorporating:

- Thermodynamic constraints to eliminate infeasible flux directions [1]

- Enzyme capacity constraints based on proteomic data

- Compartmentalization information in eukaryotic systems

- Gas exchange measurements for additional flux constraints

Conceptual Framework: How Parallel Labeling Resolves Underdeterminacy

The following diagram illustrates how information from complementary tracers constrains the flux solution space:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a biological objective function in FBA, and why is it important? In FBA, a biological objective function is a linear combination of metabolic reactions that the model is programmed to maximize or minimize. It represents a hypothesized cellular goal, such as maximizing growth rate or ATP production [34]. Selecting an appropriate objective is crucial because it determines which single flux distribution is predicted from the vast space of possible solutions that are all consistent with the network stoichiometry [34] [35]. An inaccurate objective function will lead to predictions that do not match experimental data.

Q2: My FBA-predicted growth rate does not match the experimentally measured value. How can I troubleshoot this? Discrepancies between predicted and experimental growth rates often point to issues with model constraints or the objective function itself. Follow these troubleshooting steps:

- Verify Biomass Composition: Ensure the biomass reaction in your model accurately reflects the organism's known macromolecular composition (e.g., proteins, lipids, nucleic acids) under your specific experimental conditions.

- Check Exchange Flux Boundaries: Confirm that the upper and lower bounds for substrate uptake (e.g., glucose, oxygen) and product secretion in the model match the measured uptake and secretion rates from your experiment [34].

- Inspect the Objective Function: Ensure the model is correctly set to maximize the flux through the biomass reaction. Use tools like MEMOTE for quality control to check that biomass precursors can be synthesized from the provided substrates [36].

- Evaluate Network Completeness: The model may be missing reactions critical for growth under your conditions. Use gap-filling algorithms to identify and add essential missing reactions [34].

Q3: What advanced methods can help identify the correct objective function for my system? For systems where the true biological objective is unknown, data-driven frameworks can be used. Methods like ObjFind and TIObjFind use experimental flux data (e.g., from 13C-MFA) to calculate "Coefficients of Importance" for different reactions [35]. These coefficients form a weighted objective function that, when maximized, yields flux predictions that best align with the experimental data, thereby inferring the organism's metabolic objectives [35].

Q4: How can I visualize an FBA-calculated pathway to check its biological feasibility? Manually interpreting a list of reactions from an FBA result is challenging. Use dedicated visualization tools that automatically generate pathway maps from the flux distribution. Tools like CAVE (a cloud-based platform) can take your model and FBA solution to create an interactive graph of the pathway, helping you quickly examine mass flow and identify unusual routes or errors [37]. Escher is another tool that allows visualization on pre-drawn metabolic maps [37].

Q5: How does FBA complement 13C-MFA in analyzing underdetermined flux distributions? 13C-MFA and FBA have a synergistic relationship when dealing with underdetermined systems.

- 13C-MFA uses experimental isotopic labeling data to estimate a single, statistically justified flux map, effectively reducing the space of possible solutions [36] [38].

- FBA can use the fluxes determined by 13C-MFA (e.g., substrate uptake or growth rates) as constraints to define its solution space. Conversely, the flux map from 13C-MFA can be used to validate the predictions of an FBA model or to infer its objective function, creating a cycle of model improvement and hypothesis testing [36] [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: FBA Predicts Non-Viable Growth After Gene Knockout, but the Mutant Grows in the Lab

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Metabolic Flexibility: The model may not account for alternative pathways or isozymes that can compensate for the knocked-out gene.

- Solution: Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to assess the range of possible fluxes for each reaction. The existence of feasible alternate pathways in the FVA results suggests redundancy [34].

- Regulatory Misrepresentation: Standard FBA does not include regulatory rules that might activate compensatory pathways in the real organism.

- Solution: Use methods like Regulatory FBA (rFBA) if regulatory information is available, or manually relax constraints on putative bypass reactions [35].

- Incorrect Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Association: The association between the knocked-out gene and its catalyzed reaction(s) in the model may be incomplete or incorrect.

- Solution: Manually curate the GPR rules for the affected reaction to ensure they accurately represent gene essentiality [39].

Problem: FBA Predicts Unrealistic ATP or Reductant (NADPH) Yields

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Unconstrained Energy Metabolism: The model may be generating ATP without any thermodynamic or kinetic penalties.

- Solution: Apply additional constraints, such as setting a non-growth-associated ATP maintenance (NGAM) demand or using a method like parsimonious FBA (pFBA) to find the flux distribution that minimizes total enzyme usage [37].

- Infinite Sinks for Currency Metabolites: The model might lack necessary demand or exchange reactions for cofactors, allowing them to be created or consumed without cost.

- Solution: Review the model's boundaries for metabolites like ATP, NADH, and NADPH. Tools like CAVE allow for easy checking and modification of these reaction bounds [37].

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol: Validating an FBA Model with Experimental Data

Objective: To assess the predictive accuracy of a genome-scale metabolic model by comparing its growth predictions to experimental data across multiple conditions.

Materials:

- Software: A computational environment with an FBA solver (e.g., COBRA Toolbox [34] or cobrapy [36]).

- Model: A genome-scale metabolic model in SBML format.

- Data: Experimentally measured growth rates and substrate uptake rates for the organism grown on different carbon sources.

Methodology:

- Define the Biological Objective: Set the model's objective function to maximize the flux through the biomass reaction [34].

- Constrain the Model: For each growth condition (e.g., glucose, glycerol):

- Run Simulation: Perform FBA for each condition to predict the optimal growth rate.

- Validate: Compare the predicted growth rates against the experimentally measured rates. A strong positive correlation indicates a well-constrained and accurate model [36].

Protocol: Inferring an Objective Function Using Experimental Fluxes

Objective: To determine the set of metabolic reactions a cell prioritizes by reconciling FBA predictions with 13C-MFA flux data.

Materials:

- Software: Implementation of the TIObjFind framework or similar [35].

- Model: A metabolic network model.

- Data: Experimentally determined internal flux map (

v_exp) from 13C-MFA.

Methodology:

- Formulate the Optimization Problem: The framework solves for a vector of Coefficients of Importance (

c) that defines a weighted objective function (Z = c^T * v). - Align Prediction with Data: The optimization finds the

cthat, when used in FBA, produces a flux distribution (v) that is as close as possible to the experimental data (v_exp) [35]. - Interpret Results: The resulting Coefficients of Importance (

c) quantify the contribution of each reaction to the inferred cellular objective. Reactions with high coefficients are those the metabolism is optimized for under the measured conditions [35].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Common Biological Objective Functions in FBA

| Objective Function | Mathematical Formulation | Biological Rationale | Typical Use Case | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximize Biomass | Z = v_biomass |

Simulates natural selection for maximum growth rate. | Predicting wild-type growth phenotypes and nutrient requirements [34]. | ||

| Maximize ATP Yield | Z = v_ATPM |

Assumes energy production is a key driver. | Studying energy metabolism under stress [34]. | ||

| Minimize Total Flux | `Z = ∑ | v_i | ` (or pFBA) | Mimics evolutionary pressure to minimize enzyme investment. | Finding the most efficient pathways; often used with other constraints [37]. |

| Maximize Product Yield | Z = v_product |

A user-defined objective for metabolic engineering. | Optimizing microbial strains for chemical production [35]. |

Table 2: Summary of FBA Software and Tools

| Tool Name | Key Features | User Skill Level | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Comprehensive suite for constraint-based analysis in MATLAB. | Advanced | [34] |

| cobrapy | Python version of COBRA tools; good for scripting. | Intermediate | [36] |

| CAVE | Cloud-based; no coding required; integrated calculation & visualization. | Beginner/Intermediate | [37] |

| Escher | Web-based tool for visualizing FBA results on pathway maps. | Beginner | [37] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for FBA

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB suite providing the core algorithms for FBA and other constraint-based methods. | Essential for implementing advanced methods like OptKnock for metabolic engineering [34]. |

| cobrapy | A Python package that provides similar functionality to the COBRA Toolbox. | Enables FBA integration into larger Python-based data analysis and bioinformatics workflows [36]. |

| SBML Format | Systems Biology Markup Language; a standard format for exchanging and storing metabolic models. | Allows models to be used across different software tools and shared with the community [34] [39]. |

| BiGG Models Database | A repository of high-quality, curated genome-scale metabolic models. | Provides reliable, ready-to-use models for many organisms, facilitating reproducible research [37]. |

| 13C-MFA Flux Data | Experimentally determined internal flux maps. | Serves as the ground-truth data for validating FBA models or inferring objective functions [36] [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary benefit of adding thermodynamic constraints to 13C-MFA? Integrating thermodynamic constraints eliminates thermodynamically infeasible flux solutions by relating reaction directions and fluxes to Gibbs free energy values. This significantly reduces the solution space in underdetermined systems, leading to more accurate and physiologically relevant flux estimates [40].

2. My flux solution is thermodynamically infeasible. What is the first parameter I should check? You should first verify the physicochemical parameters used in the calculations, particularly the ionic strength (I) and temperature (t). Many tools use default values (e.g., I=0.25 M, t=25°C) that may not match your experimental conditions. Using incorrect parameters, especially with adjustment equations that are only valid for I < 0.1 M, can lead to incorrect estimations of Gibbs free energy and thus infeasible fluxes [40].

3. How can I use enzyme capacity as a constraint? Enzyme capacity can be incorporated via the parsimonious 13C MFA (p13CMFA) approach. This method runs a secondary optimization that minimizes the total reaction flux in the network. This flux minimization can be weighted by gene expression data, ensuring that the selected flux solution favors pathways with higher enzymatic evidence and is more biologically relevant [14].