Strategic Host Organism Selection for Heterologous Natural Product Expression: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select optimal host organisms for the heterologous expression of natural products.

Strategic Host Organism Selection for Heterologous Natural Product Expression: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to select optimal host organisms for the heterologous expression of natural products. It covers foundational principles, from defining key selection criteria to profiling the most utilized microbial chassis, including Streptomyces, E. coli, yeast, and fungal systems. The content delves into advanced methodological applications for activating silent biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) and scaling production, alongside practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome common expression barriers. Finally, it examines validation techniques and comparative analyses of host performance, integrating recent advances in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering to guide efficient and sustainable bioproduction.

Understanding the Fundamentals: Key Criteria and Major Hosts for Heterologous Expression

Selecting an optimal host organism is a critical first step in the successful heterologous expression of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). This in-depth technical guide examines three foundational selection criteria—genomic GC content, codon usage bias, and host metabolic capability—through the lens of modern synthetic biology and systems biology approaches. We present quantitative frameworks for evaluating potential expression hosts, detailed experimental protocols for criterion validation, and cutting-edge computational tools that enable predictive host performance assessment. By integrating these multifaceted selection parameters, researchers can systematically identify ideal chassis organisms that maximize titers of valuable natural products, from therapeutic compounds to industrial enzymes, thereby accelerating the development of microbial-based biotechnological processes.

The heterologous expression of natural products involves transferring genetic material from a source organism into a surrogate host that lacks the native biosynthetic pathway. This approach has become a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, enabling the production of pharmaceuticals, industrial enzymes, and fine chemicals [1] [2]. However, successful expression hinges on selecting an appropriate host organism that can not only express the foreign genes but also support the complete biosynthetic pathway and produce the target compound at viable yields.

Host selection represents a critical bottleneck in the heterologous expression pipeline. Suboptimal hosts may fail to express complex natural products due to incompatible molecular machinery, insufficient metabolic capacity, or inability to support proper protein folding and post-translational modifications. The three criteria examined in this guide—GC content, codon usage, and metabolic capability—form an interconnected framework for evaluating host potential. GC content influences DNA stability and gene expression efficiency; codon usage bias affects translation rates and protein fidelity; while metabolic capability determines whether the host can supply necessary precursors and cofactors [3] [4] [5]. Emerging approaches in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering now allow researchers to address limitations in these areas through host engineering, but selecting a naturally compatible chassis organism remains the most efficient strategy.

GC Content Considerations

Fundamental Principles and Biological Significance

Genomic GC content, expressed as the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) nucleotides within a DNA sequence, significantly influences the physical and functional properties of nucleic acids [6]. The GC pair forms three hydrogen bonds compared to two in AT pairs, resulting in greater thermal stability for GC-rich DNA sequences. This stability manifests practically as higher melting temperatures (Tm), with GC-content elevation of 1% corresponding to a Tm increase of approximately 0.41°C in standard saline conditions [6]. This relationship follows the established formula:

[ T_m \approx 69.3 + 0.41 \times (\% GC) ]

GC-content varies substantially across organisms, ranging from less than 25% in AT-rich species like some Mycoplasma to around 72% in GC-rich Streptomyces [6]. In plants, GC content varies between 33.6% and 48.9% across monocot species, with several groups exceeding the GC content known for any other vascular plant group [3]. These variations have profound functional implications. GC-rich regions in eukaryotic genomes are typically gene-dense, enriched in housekeeping genes, and associated with higher transcriptional activity and open chromatin structures [6].

Experimental Determination Methods

Table 1: Methods for Experimental Determination of GC Content

| Method | Principle | Applications | Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buoyant Density Centrifugation | Equilibrium sedimentation in CsCl density gradients | Direct GC content measurement | Ultracentrifugation equipment, purified DNA |

| Thermal Denaturation | Hyperchromic shift during DNA melting | Indirect estimation via T_m | Spectrophotometer with temperature control |

| Hydrolysis with HPLC/LC-MS | Base separation after enzymatic/acid hydrolysis | Direct base composition | HPLC or LC-MS equipment, nucleoside standards |

| Flow Cytometry | Fluorescent dye binding (Hoechst 33258 for AT, chromomycin A3 for GC) | Rapid analysis of multiple samples | Flow cytometer, calibrated standards |

Beyond experimental methods, computational approaches using bioinformatics algorithms can efficiently calculate GC content from digital nucleotide sequences. These approaches enable both global and local analyses through sliding window algorithms (typically 500 bp windows with 100 bp steps) to reveal compositional heterogeneity like isochores [6]. Programming libraries like Biopython facilitate batch GC analysis through downloadable nucleotide databases.

Implications for Heterologous Expression

Substantial disparities in GC content between source DNA and host genome can create significant expression challenges. High GC content in donor genes can lead to problematic secondary structures in DNA and RNA that hinder transcription and translation efficiency [7] [8]. Furthermore, GC-rich sequences may contain methylated cytosine residues (CpG islands) that can trigger silencing mechanisms in certain hosts [8].

Research has revealed that GC content shows a quadratic relationship with genome size and may have deep ecological relevance [3]. Increased GC content has been documented in species able to grow in seasonally cold and/or dry climates, possibly indicating an advantage of GC-rich DNA during cell freezing and desiccation [3]. These adaptations highlight how environmental factors shape genomic architecture and should be considered when designing expression systems for industrial applications where environmental control may be limited.

Codon Usage Optimization

Biological Basis of Codon Usage Bias

Codon usage bias refers to the non-uniform usage of synonymous codons—different codons that encode the same amino acid—across the genome [4] [2]. This phenomenon arises from the degeneracy of the genetic code, where 61 sense codons encode 20 standard amino acids, with only methionine and tryptophan encoded by single codons [4] [8]. The bias reflects a balance between mutational pressures and natural selection for translational optimization, with highly expressed genes typically showing stronger codon bias [2].

The primary mechanism underlying codon usage effects involves the correlation between preferred codons and the abundance of cognate tRNA molecules [4] [2]. In Escherichia coli, for example, high-frequency-usage codons correlate with abundant tRNA isoacceptors, optimizing translational efficiency and accuracy [4]. This relationship is particularly important for highly expressed genes involved in essential cellular functions like protein synthesis and cell energetics [4]. When heterologous expression introduces rare codons disproportionate to available tRNAs, ribosome stalling, translation errors, and reduced protein yields can occur [2] [8].

Quantitative Assessment and Optimization Strategies

Table 2: Key Metrics for Assessing Codon Usage Bias

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) | Measures similarity of codon usage to highly expressed reference genes | Ranges 0-1; higher values indicate stronger bias | Primary predictor of gene expression level |

| Frequency of Optimal Codons (FOP) | Proportion of codons defined as optimal | Higher values suggest translation optimization | Comparison across genes/species |

| Codon Bias Index (CBI) | Measure of non-uniform codon usage | Values near 1 indicate strong bias | Identifying highly expressed genes |

| Effective Number of Codons (ENc) | Measure of overall bias from equal usage | Ranges 20-61; lower values indicate stronger bias | Genome-wide analyses |

Multiple codon optimization strategies have been developed, ranging from simple rare codon replacement to sophisticated algorithms that consider multiple parameters:

One Amino Acid-One Codon Approach: Replaces all occurrences of a given amino acid with the most abundant host codon [2]. While straightforward, this approach can deplete specific tRNAs and cause translational termination [7].

Host-Specific Codon Usage Tables: Adjusts codon usage to match the natural distribution in the host organism, preserving slow translation regions important for proper protein folding [7] [2].

Deep Learning-Based Optimization: Emerging approaches use bidirectional long short-term memory conditional random field (BiLSTM-CRF) models to learn codon distribution patterns from host genomes and generate optimized sequences [7]. These methods introduce the concept of "codon boxes"—sets of codons containing the same bases in different orders—to simplify sequence recoding [7].

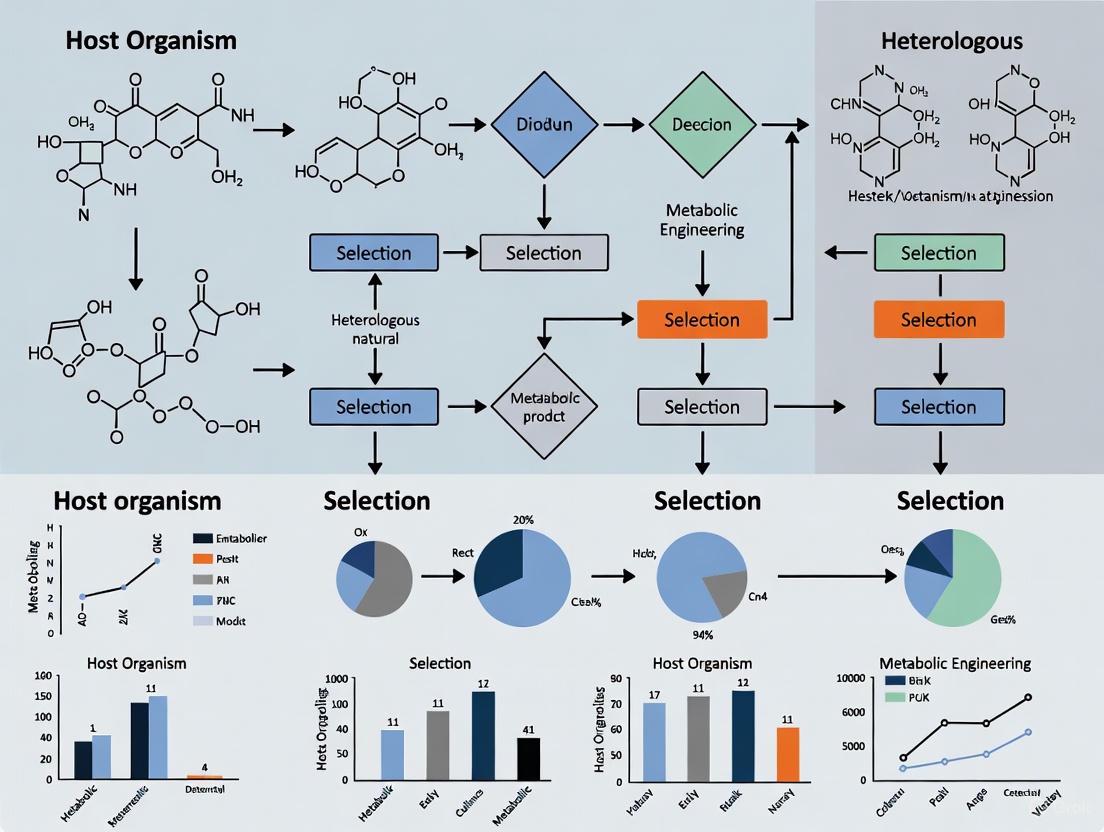

Figure 1: Codon Optimization Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in systematic codon optimization, from initial analysis to final sequence validation.

Experimental Validation of Optimization

Codon optimization outcomes must be validated experimentally, as in silico predictions don't always translate to improved expression. A seminal study expressing 154 green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants in E. coli revealed that synonymous codon substitutions affecting mRNA secondary structure stability, particularly in the first 40 nucleotides, significantly correlated with protein abundance [4]. This highlights the importance of 5' mRNA end optimization beyond mere codon frequency matching.

Beyond expression levels, codon optimization can affect protein conformation and function. Systematic single-codon substitutions in slower translation regions have been shown to alter translation kinetics, impact in vivo folding, and significantly change protein solubility and specific enzyme activity [4]. These findings underscore that codon optimization is not merely about maximizing speed but about achieving the appropriate translation kinetics for proper folding.

Metabolic Capability Assessment

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GEM)

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide powerful computational frameworks for evaluating host metabolic capabilities [5] [9]. GEMs are mathematical representations of an organism's metabolic network, comprising comprehensive sets of biochemical reactions, metabolites, and enzymes based on genome annotation [5]. These models enable in silico simulation of metabolic fluxes and prediction of organism behavior under different conditions.

The reconstruction of GEMs typically follows these steps:

- Data Collection: Gathering genome sequences, metagenome-assembled genomes, and physiological data

- Model Reconstruction: Using curated databases, literature, or automated pipelines like ModelSEED, CarveMe, or gapseq to generate draft models [5]

- Model Integration: Combining individual models into a unified computational framework [5]

Constrained-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) is the predominant framework for metabolic modeling, using flux balance analysis (FBA) to estimate reaction fluxes through the metabolic network while assuming steady-state conditions (mathematically represented as S·v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector) [5].

Host-Microbiome Metabolic Interactions

Integrated host-microbiome metabolic models represent the cutting edge of metabolic capability assessment [5] [9]. These multi-species models simulate metabolite flow between hosts and microbes, providing insights into their complex interdependencies. Recent research applying this approach to aging mice revealed a pronounced reduction in metabolic activity within the aging microbiome, accompanied by reduced beneficial interactions between bacterial species [9]. These changes coincided with the downregulation of essential host pathways, particularly in nucleotide metabolism, predicted to rely on microbiota and critical for preserving intestinal barrier function [9].

Figure 2: Host-Microbiome Metabolic Model. This diagram illustrates the compartmentalized structure of integrated metabolic models, showing metabolite exchange between host tissues via the bloodstream and with microbial communities via the gut lumen.

For natural product expression, metabolic models can predict whether a potential host can supply necessary precursors, cofactors, and energy molecules for the heterologous pathway. A study examining 181 gut microorganisms in mice found strong correlations between microbial purine metabolism and mitochondrial respiration in the host, and between microbial lipid metabolism and host DNA damage responses [9]. Such insights help identify hosts with naturally compatible metabolic networks or highlight engineering targets for host improvement.

Metabolic Engineering Strategies

When native host metabolism is insufficient, several engineering strategies can enhance metabolic capability:

- Precursor Enhancement: Overexpression of genes in precursor biosynthesis pathways

- Cofactor Regeneration: Engineering systems to regenerate ATP, NADPH, and other essential cofactors

- Competing Pathway Knockout: Eliminating pathways that divert flux away from target products

- Transport Engineering: Modifying metabolite transport to prevent intermediate leakage

- Regulatory Network Manipulation: Rewiring genetic regulators to enhance flux through desired pathways

Integrated Selection Framework

Systematic Host Evaluation

An effective host selection strategy requires integrated assessment across GC content, codon usage, and metabolic capability parameters. The following protocol provides a systematic approach:

GC Content Compatibility Assessment

- Calculate global and regional GC content for both source genes and potential hosts

- Identify sequences with extreme GC content (>70% or <30%) that may require optimization

- Evaluate need for synthetic gene redesign to improve compatibility

Codon Usage Analysis

- Calculate CAI and other bias metrics for heterologous genes in each potential host

- Identify rare codons that may cause ribosomal stalling

- Design optimized sequences using multi-parameter algorithms

Metabolic Capability Evaluation

- Reconstruct or retrieve GEMs for potential hosts

- Introduce heterologous reactions into the model

- Perform flux balance analysis to predict pathway functionality

- Identify potential metabolic bottlenecks or cofactor limitations

Integrated Scoring and Selection

- Develop weighted scoring system based on project priorities

- Rank potential hosts by composite scores

- Select top candidates for experimental testing

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Host Selection

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Specific Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codon Optimization Software | GenScript OptimumGene | Multi-parameter gene optimization | Optimizing gene sequences for expression |

| ThermoFisher Codon Optimization Tool | Web-based codon usage analysis | Preliminary sequence assessment | |

| CodonW | Multivariate codon usage analysis | Academic research applications | |

| Metabolic Modeling Platforms | ModelSEED | Automated metabolic model reconstruction | Draft model generation from genomes |

| CarveMe | Template-based model reconstruction | Rapid model building | |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based modeling and analysis | Flux balance simulations | |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | E. coli BL21(DE3) | Robust protein production | Bacterial expression trials |

| HEK293 cells | Mammalian protein expression | Eukaryotic proteins requiring modifications | |

| Xenopus laevis oocytes | Membrane protein studies | Transporters and channel proteins | |

| Analytical Tools | HPLC with UV detection | Nucleoside separation and quantification | Experimental GC content verification |

| Spectrophotometer with temperature control | DNA melting curve analysis | T_m determination for GC estimation | |

| Echinatine N-oxide | Echinatine N-oxide, MF:C15H25NO6, MW:315.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Littorine | Littorine, MF:C17H23NO3, MW:289.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The field of host selection for heterologous expression is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends. Deep learning approaches are being increasingly applied to both codon optimization and metabolic modeling, potentially enabling more accurate predictions of host performance [7]. The development of universal "codon optimization indices" that integrate multiple parameters represents an active area of research [7] [2].

The integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) with metabolic models is creating more context-specific simulations that better predict in vivo behavior [5] [9]. For aging research, these integrated models have revealed a considerable reduction in microbiome metabolic activity with age, connected to aging-related changes in the host [9]. Similar approaches could be adapted to predict host performance for specific natural product classes.

Advances in synthetic biology are also enabling more radical engineering of host organisms. CRISPR-based genome editing allows precise manipulation of host genomes to enhance compatibility with heterologous pathways. The construction of minimal genomes provides simplified chassis organisms with reduced metabolic complexity and regulatory conflicts.

In conclusion, successful host selection requires careful consideration of GC content compatibility, codon usage optimization, and metabolic capability. By systematically evaluating these criteria using the frameworks and tools described in this guide, researchers can significantly improve the success rate of heterologous expression projects. As our understanding of these fundamental biological parameters deepens and computational tools become more sophisticated, the process of host selection will increasingly shift from empirical testing to predictive design, accelerating the discovery and production of valuable natural products.

The selection of an appropriate eukaryotic host organism is a critical determinant of success in the heterologous expression of natural products and recombinant proteins. While insect cell systems offer advanced post-translational modification capabilities for complex biologics, microbial fungal platforms provide unparalleled advantages in scalability and yield for a wide range of applications. Yeast systems, particularly Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Komagataella phaffii, offer a well-characterized genetic toolbox and rapid growth, while filamentous fungi, including various Aspergillus and Trichoderma species, deliver exceptional protein secretion capacity and natural product synthesis capabilities. This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of these eukaryotic platforms, including performance metrics, engineering methodologies, and strategic considerations for host selection in biopharmaceutical and industrial applications.

Eukaryotic expression systems bridge the gap between simple bacterial hosts and complex mammalian systems, offering sophisticated protein processing with manageable cultivation requirements. The global market for therapeutic proteins, currently approaching $400 billion annually, increasingly relies on these platforms to meet demand for complex biologics, enzymes, and natural products [10] [11].

Yeast systems combine prokaryotic advantages (rapid growth, genetic tractability) with eukaryotic processing capabilities. S. cerevisiae remains a foundational model organism with extensive characterization, while non-conventional yeasts like K. phaffii offer superior secretion efficiency and stronger promoters [11] [12]. Recent advances in yeast glycoengineering have enabled production of antibodies with "human-like" glycosylation patterns, expanding their therapeutic applicability [11].

Filamentous fungi represent industrial workhorses for enzyme production, with species such as Aspergillus niger achieving remarkable secretion titers exceeding 30 g/L for native proteins [10] [13]. Their GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status, efficient protein secretion machinery, and ability to synthesize complex natural products make them particularly valuable for industrial-scale production [14] [13]. The filamentous growth habit, however, presents challenges in fermentation viscosity and oxygen transfer.

Insect cell systems utilize baculovirus expression vectors to produce complex eukaryotic proteins with post-translational modifications more similar to mammals than microbial systems. While not covered extensively in the search results, they remain valuable for structural biology and viral vaccine production where higher-order assembly is required.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Eukaryotic Expression Platforms

| Platform | Typical Hosts | Max Protein Yield | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast | S. cerevisiae, K. phaffii | ~1-5 g/L (varies by protein) | Rapid growth, well-established genetics, GRAS status available | Hypermannosylation, secretion bottlenecks for complex proteins [11] [15] |

| Filamentous Fungi | A. niger, A. oryzae, T. reesei | Up to 30 g/L (homologous), ~100-400 mg/L (heterologous) [10] [13] | Exceptional secretion capacity, diverse natural product synthesis, GRAS status | High background proteases, complex genetics, longer fermentation cycles |

| Insect Cells | Sf9, Sf21, High Five | ~1-500 mg/L (highly variable) | Proper folding of mammalian proteins, complex PTMs, baculovirus scalability | Viral expression system, different glycosylation patterns, higher costs |

Table 2: Representative Heterologous Production Achievements Across Platforms

| Host System | Target Product | Yield | Key Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. niger (AnN2 chassis) | Glucose oxidase (AnGoxM) | ~1276-1328 U/mL [10] | CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multi-copy integration at high-expression loci |

| A. niger (AnN2 chassis) | Pectate lyase (MtPlyA) | ~1627-2106 U/mL [10] | Combined genomic engineering and COPI vesicle trafficking enhancement |

| A. niger | Alkaline serine protease | 10.8 mg/mL [10] | CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multi-copy expression system |

| A. oryzae | Recombinant antibodies (adalimumab) | Functional production achieved [14] | GRAS host with strong protein secretion capability |

| T. reesei | Human interferon alpha-2b | 4.5 g/L in bioreactor [13] | Strain engineering and optimized cultivation conditions |

| S. cerevisiae | Unspecific peroxygenase (AaeUPO) | 13.9-fold improvement over WT [12] | Signal peptide engineering using Gaussia luciferase screening |

Yeast Expression Systems

Genetic Tools and Engineering Strategies

Yeast expression systems benefit from extensive genetic toolboxes including episomal plasmids, efficient homologous recombination, and CRISPR-Cas9 systems for precise genome editing. Inducible promoters (e.g., galactose-inducible GAL1, copper-inducible CUP1) and synthetic hybrid promoters enable temporal control of gene expression, while a library of signal peptides (including α-mating factor pre-pro leader) facilitates efficient protein secretion [12] [16].

Recent advances focus on addressing glycosylation limitations through humanization of glycosylation pathways and engineering of secretion machinery components. For example, the deletion of OCH1 gene reduces hypermannosylation, while overexpression of protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident chaperones enhances proper folding of complex proteins [11].

Signal Peptide Optimization Protocol

Signal peptide efficiency critically determines secretion yields in yeast. The following high-throughput protocol enables rapid screening of optimal signal peptides for target proteins:

Experimental Workflow for Signal Peptide Optimization

- Library Construction: Perform error-prone PCR on the native signal peptide sequence of your target gene to generate sequence diversity [12].

- Reporter Fusion: Clone mutated signal peptides upstream of a truncated target protein domain (first 55 amino acids of mature protein) fused C-terminally to Gaussia luciferase (GLuc) in a yeast expression vector (e.g., pESC-TRP for S. cerevisiae) [12].

- Transformation and Screening: Transform the library into appropriate yeast strain (e.g., INVSc1) and plate on selective medium. Pick colonies into 96-well deep-well plates containing selective medium with glucose as carbon source [12].

- Expression Induction: Grow cultures to saturation, then induce protein expression by switching to medium with galactose as carbon source. Continue incubation for 24-48 hours [12].

- Luciferase Assay: Collect supernatant and assay for luciferase activity using coelenterazine substrate in 96-well format, measuring luminescence at 475 nm [12].

- Hit Validation: Select clones showing highest luminescence for sequence analysis. Validate best-performing signal peptides by expressing full-length target protein without luciferase fusion and quantify yield [12].

This protocol enabled identification of signal peptide mutations that improved expression of unspecific peroxygenase (AaeUPO) in S. cerevisiae by 13.9-fold compared to wild-type signal peptide [12].

Filamentous Fungal Platforms

Genomic Engineering and Chassis Development

Filamentous fungi offer exceptional protein secretion capacity but require extensive engineering to optimize heterologous production. A key strategy involves developing low-background chassis strains through systematic deletion of endogenous high-abundance proteins and proteases. For example, engineering of A. niger strain AnN1 involved deletion of 13 out of 20 copies of the native glucoamylase (TeGlaA) gene and disruption of the major extracellular protease gene PepA, resulting in the AnN2 chassis strain with 61% reduction in extracellular protein background [10].

Fungal Chassis Development Workflow

Secretory Pathway Engineering

Beyond genomic deletions, enhancing the secretory capacity of filamentous fungi involves multiple engineering targets:

- Vesicle Trafficking: Overexpression of COPI vesicle trafficking component Cvc2 enhanced production of pectate lyase MtPlyA by 18% in A. niger [10].

- Unfolded Protein Response (UPR): Engineering transcription factor HacA to enhance endoplasmic reticulum folding capacity [13].

- Cell Wall Engineering: Modification of cell wall composition to reduce protein adsorption and increase release of secreted proteins [13].

- Morphological Engineering: Deletion of racA gene to induce hyperbranching morphology, increasing hyphal tips where secretion occurs [10] [14].

CRISPR-Cas9 Protocol for Multi-Copy Gene Integration

Efficient multi-copy integration into transcriptionally active loci is crucial for high-level heterologous expression in fungi:

- Design gRNA Targets: Design CRISPR gRNAs targeting the 5' and 3' flanking regions of native high-expression gene copies (e.g., glucoamylase loci in A. niger) [10].

- Prepare Donor DNA: Construct donor DNA containing your gene of interest driven by a strong promoter (e.g., AAmy promoter) and terminator (e.g., AnGlaA terminator), with homology arms matching the target loci [10].

- Co-transformation: Co-transform fungal protoplasts with Cas9-expressing plasmid, gRNA constructs, and linear donor DNA using standard PEG-mediated transformation [10].

- Screening and Validation: Screen transformations for successful integration via antibiotic resistance and confirm by PCR and Southern blotting. Quantify copy number through qPCR [10].

- Marker Recycling: For sequential integrations, remove selection markers using Cre-loxP or FLP-FRT recombination systems between rounds of integration [10].

This approach enabled successful expression of diverse proteins in A. niger, including glucose oxidase (AnGoxM), thermostable pectate lyase (MtPlyA), bacterial triose phosphate isomerase (TPI), and the medicinal protein Lingzhi-8 (LZ8), with yields ranging from 110.8 to 416.8 mg/L in shake-flask cultures [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Eukaryotic Expression Systems

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Tools | Cas9 nucleases, gRNA expression vectors | Targeted genome editing; gene knockouts, precise integrations [10] [14] |

| Modular Genetic Parts | Constitutive promoters (gpdA, ermEp), inducible systems (Tet-on, copper), signal peptides (α-MF, native SPs) | Control of gene expression timing and strength; directing protein secretion [10] [17] [12] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance (hygromycin, phleomycin), auxotrophic markers (ura3, trp1) | Selective pressure for transformants; marker recycling systems [10] [12] |

| Secretory Pathway Reporters | Gaussia luciferase (GLuc), alkaline phosphatase | Quantifying secretion efficiency; signal peptide screening [12] |

| Vectors and Cloning Systems | Bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs), SEVA vectors, Golden Gate assembly systems | Large DNA fragment cloning; modular vector design [17] [18] |

| Cultivation Media | Minimal media, induction media (galactose, tetracycline) | Controlled culture conditions; induction of expression systems [12] [15] |

| Sirt2-IN-17 | Sirt2-IN-17, MF:C24H15N3O2S, MW:409.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kushenol O | Kushenol O, MF:C27H30O13, MW:562.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Perspectives

Strategic selection of eukaryotic expression platforms requires careful consideration of target molecule complexity, yield requirements, and production timeline. Yeast systems offer the fastest pathway to initial protein production with reasonable yields, particularly with recent advances in glycoengineering and secretion optimization. Filamentous fungal platforms deliver superior yields for industrial enzymes and complex natural products but require more extensive host engineering. Insect cell systems remain valuable for proteins requiring complex assembly or post-translational modifications not achievable in microbial systems.

Future directions in eukaryotic host engineering include the development of broad-host-range synthetic biology tools that function across diverse fungal species, machine learning-assisted optimization of genetic elements, and integration of multi-omics data for systems-level engineering [18] [16]. The emerging paradigm of "host context as a design variable" rather than a fixed parameter will further enhance our ability to match platform capabilities to product requirements, accelerating the development of next-generation biopharmaceuticals and sustainable bioprocesses [18].

The selection of an optimal host organism is a critical, foundational decision in the successful heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) for natural product (NP) discovery and production. This process is central to accessing the vast reservoir of uncoded chemical diversity found in microbial genomes, estimated to be as high as 97% unexplored [19]. While empirical experience has traditionally guided host selection, recent advances in large-scale sequencing, bioinformatics, and synthetic biology are enabling a more quantitative, data-driven paradigm. This review synthesizes recent quantitative studies to outline clear trends in host performance, providing researchers and drug development professionals with an evidence-based framework for selecting and engineering heterologous expression hosts. The shift from trial-and-error to predictive design holds immense potential for accelerating the discovery and development of novel pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and other high-value bioproducts.

Quantitative Landscape of Heterologous Expression Success

Large-scale heterologous expression studies provide the most direct quantitative measure of success rates across different hosts and strategies. These studies reveal that while heterologous expression is a powerful discovery tool, significant challenges remain in consistently achieving high success rates.

Table 1: Success Rates from Large-Scale Heterologous Expression Studies

| BGC Source | Number of BGCs Cloned | Cloning Success Rate | Host(s) Used | BGCs Expressed (Success Rate) | New NP Families Isolated | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharothrix espanaensis | 17 | 68% | S. lividans DYA, S. albus J1074 | 4 (11%) | 2 | [19] |

| 14 Streptomyces spp., 3 Bacillus spp. | 43 | 100% | S. avermitilis SUKA17, S. lividans TK24, B. subtilis JH642 | 7 (16%) | 5 | [19] |

| 100 Streptomyces spp. | 58 | 72% | S. albus J1074, S. lividans RedStrep 1.7 | 15 (24%) | 3 | [19] |

| 1 Bacteroidota, 10 Pseudomonadota, 3 Cyanobacteriota, 5 Actinomycetota, 8 Bacillota | 83 | 86% | E. coli BL21(DE3) | 27 (32%) | 3 | [19] |

Analysis of these studies indicates an average expression success rate of approximately 11% to 32%, with the highest success reported in E. coli for ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) [19]. The variability in success rates underscores the context-dependent nature of host selection, influenced by factors such as BGC size, biosynthetic class, and phylogenetic distance between the source organism and the heterologous host.

Quantitative Performance of Major Host Organisms

Different host organisms offer distinct advantages and limitations, quantified through key performance metrics such as protein yield, success rate for specific NP classes, and scalability.

Prokaryotic Hosts:E. coliandStreptomyces

Escherichia coli remains one of the most widely used hosts for recombinant protein expression due to its rapid growth, well-characterized genetics, and extensive molecular toolset. Over 100 protein products expressed in E. coli have reached successful commercial applications [20]. However, large-scale expression studies reveal specific challenges; for instance, a study of 9,644 protein genes found that over one-fifth failed to express in E. coli BL21(DE3), even in the absence of toxicity, signal peptides, or transmembrane domains [20]. The primary quantitative challenges in E. coli include protein misfolding and aggregation, with soluble expression of complex proteins like single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) often below 20% without optimization [21]. Co-expression of molecular chaperones has proven to be a quantitatively effective strategy, with Trigger Factor (pTf16) demonstrated to improve soluble scFv yield from a baseline of 14.20% to 19.65% [21].

Streptomyces species are the preferred hosts for expressing complex natural products, particularly polyketides and non-ribosomal peptides from actinobacteria. The development of optimized Streptomyces chassis strains has shown quantifiable improvements in yield. For example, the Micro-HEP platform utilizing an engineered S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 chassis demonstrated a direct correlation between BGC copy number and product yield, with a 2-to-4-fold increase in xiamenmycin production achieved through multi-copy chromosomal integration [22]. This platform also successfully expressed the griseorhodin BGC, leading to the discovery of a new compound, griseorhodin H [22].

Table 2: Key Host Organisms and Their Quantitative Performance Metrics

| Host Organism | Typical Yield Range | Optimal NP Class | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Variable; scFv yield improved from 14.2% to 19.65% with chaperones [21] | RiPPs, peptides, small proteins [19] | Rapid growth, high transformation efficiency, extensive toolkit | Limited PTMs; >20% failure rate for some protein classes [20] |

| Streptomyces spp. | Yield increase proportional to BGC copy number (2-4 fold) [22] | PKS, NRPS, PKS-NRPS hybrids [19] [22] | Native ability to produce complex secondary metabolites | Lower expression success rate (11-24% in large studies) [19] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Quantitative data from large studies is limited | NRPS, RiPPs [19] | Efficient protein secretion, Generally Regarded As Safe (GRAS) status | Used in only 16% of successful large-scale studies [19] |

| Cell-Free Systems | Emerging technology; enables rapid prototyping [23] | RiPPs, pathway prototyping [23] | Bypasses cellular constraints, open system | Scaling challenges, high cost for production [23] |

Emerging Hosts and Technologies

Cell-free synthetic biology represents a paradigm shift away from whole-cell systems. This technology uses purified cellular components for in vitro transcription and translation, offering unique advantages for prototyping and producing toxic compounds or pathways with complex requirements [23]. While quantitative yield comparisons to traditional hosts are still emerging, its value lies in rapid pathway debugging and enzyme characterization, accelerating the overall discovery pipeline [23].

Data-Driven Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The transition to quantitative host selection is underpinned by sophisticated experimental and computational protocols designed to systematically test and optimize expression.

Protocol: High-Throughput BGC Cloning and Cross-Host Screening

This protocol, derived from large-scale studies, is designed for empirically determining the most suitable host for a given BGC [19].

- BGC Prioritization & Bioinformatics: Identify target BGCs using genome mining tools (e.g., antiSMASH). Prioritize based on predicted structural novelty, biosynthetic class, or phylogenetic origin of the source organism [19] [24].

- Cloning Vector Assembly: Select appropriate cloning vectors compatible with the intended hosts. For large BGCs (>10 kb), use cosmic or BAC vectors. Incorporate host-specific elements such as origins of replication and selectable markers for E. coli and Streptomyces [25] [22].

- BGC Capture: Clone the BGC from genomic DNA. Methods include Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) cloning, exonuclease combined with RecET recombination (ExoCET), or advanced in vitro techniques like Golden Gate assembly for synthetic clusters under 18 kb [19] [22].

- Multi-Host Transformation: Transfer the constructed library into a panel of heterologous hosts. Standard panels often include:

- E. coli BL21(DE3) for RiPPs and small proteins.

- Streptomyces albus J1074 or S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 for actinobacterial PKS/NRPS clusters.

- Bacillus subtilis for NRPS and RiPPs from Firmicutes. Conjugation from E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) or similar donor strains is typically used for DNA transfer into Streptomyces [19] [22].

- Expression Analysis & Metabolite Profiling: Screen for successful expression by cultivating exconjugants and analyzing metabolite extracts using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). Compare chromatographic profiles to control strains to identify new or overproduced compounds [19] [24].

Protocol: Chaperone-Assisted Soluble Expression inE. coli

For targets prone to misfolding in E. coli, a systematic chaperone co-expression protocol can significantly improve yields [21].

- Strain and Plasmid Preparation: Transform E. coli BL21(DE3) with a panel of chaperone plasmids (e.g., pG-KJE8, pGro7, pKJE7, pG-Tf2, pTf16). Each plasmid encodes a different set of chaperones (DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE, GroEL/ES, Trigger Factor, or combinations).

- Expression Strain Generation: Subsequently, transform the pET-based target protein plasmid into the pre-made chaperone-containing strains.

- Induction and Folding Assistance: Cultivate the co-expression strains and induce both the target protein (with IPTG) and the chaperone systems (with L-arabinose or tetracycline, as required by the specific plasmid).

- Quantitative Analysis: Quantify soluble expression yield via His-tag ELISA and SDS-PAGE. Assess functional activity and structural fidelity using techniques like competitive ELISA and circular dichroism spectroscopy to determine the optimal chaperone system for the specific target [21].

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Computational models are becoming increasingly important for predictive host selection. The Quantitative Heterologous Pathway Design algorithm (QHEPath) represents a significant advance. This algorithm, used with a Cross-Species Metabolic Network Model (CSMN), can evaluate thousands of biosynthetic scenarios to predict whether introducing heterologous reactions can break the native yield limit of a host [26]. Systematic calculations using this approach have revealed that over 70% of product pathway yields can be improved by introducing appropriate heterologous reactions, and have identified 13 common engineering strategies effective across various products and hosts [26].

Flowchart for Host Selection and Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful heterologous expression relies on a suite of specialized reagents and genetic tools. The following table details key solutions for constructing and optimizing expression in different hosts.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Heterologous Expression

| Reagent / Tool Name | Function | Key Application & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| pET Series Vectors | High-copy number expression plasmids for T7 RNA polymerase-driven expression in E. coli [20]. | Standard for recombinant protein expression in E. coli BL21(DE3); provides strong, inducible control. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Sets (e.g., pG-KJE8, pTf16) | Plasmid systems for co-expressing molecular chaperones like DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE, GroEL/ES, and Trigger Factor [21]. | Enhances soluble yield of misfolding-prone proteins in E. coli; pTf16 improved scFv yield by ~5.5% [21]. |

| E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) | A non-methylating, conjugative donor strain for transferring DNA from E. coli to actinomycetes [22]. | Essential for moving large BGC constructs into Streptomyces and other Gram-positive hosts. |

| Optimized Streptomyces Chassis (e.g., S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023) | Engineered host with deleted endogenous BGCs to reduce metabolic burden and background interference, plus multiple recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites [22]. | Provides a "clean" background for heterologous expression and allows for multi-copy BGC integration to boost yield. |

| RMCE Cassettes (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox) | Modular DNA cassettes for site-specific, multi-copy integration of BGCs into the genome of the chassis host [22]. | Enables stable, high-level expression of BGCs without plasmid backbone integration, avoiding instability. |

| antiSMASH Software | A comprehensive bioinformatic platform for the identification and analysis of BGCs in genomic data [22] [23]. | Primary tool for genome mining to prioritize BGCs for heterologous expression based on novelty and class. |

| Daphnilongeridine | Daphnilongeridine, MF:C32H51NO4, MW:513.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NSD2-PWWP1 ligand 1 | NSD2-PWWP1 ligand 1, MF:C25H27N3O3, MW:417.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The field of heterologous expression for natural product discovery is undergoing a fundamental shift from empirical art toward quantitative science. Data from large-scale studies now provide clear benchmarks for success rates, firmly establishing that no single host is universally optimal and that strategic selection is paramount. The emerging trend is the use of integrated platforms, such as Micro-HEP for Streptomyces, which combine specialized E. coli strains for DNA engineering with highly optimized chassis strains for expression, leading to quantifiable improvements in yield and success in discovering novel compounds [22].

Future progress will be driven by the expansion of such integrated platforms and the increasing incorporation of machine learning and sophisticated metabolic models like QHEPath [26] [27]. The critical bottleneck to developing predictive models is the lack of large, high-fidelity, and openly available protein expression datasets [27]. As these datasets grow and algorithms improve, the community can anticipate a future where host selection and genetic design are guided by predictive in silico models, dramatically reducing experimental trial and error and accelerating the rate at which nature's chemical diversity can be harnessed for drug discovery and biotechnology.

The Role of Host Physiology in Tolerating Cytotoxic Secondary Metabolites

The pursuit of novel natural products, such as cytotoxic and antimicrobial compounds, is a mainstay of pharmaceutical discovery [28]. A significant challenge in this field arises when the native producer of a valuable metabolite is unculturable, difficult to manipulate genetically, or produces the compound in minuscule yields. Heterologous biosynthesis has emerged as a powerful solution, wherein the biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) responsible for producing these compounds are transferred into a surrogate host organism [29] [30]. The core thesis of this whitepaper is that the successful heterologous production of cytotoxic secondary metabolites is not merely a function of transferring genetic material but is fundamentally constrained and enabled by the physiological tolerance of the host organism to the toxic compounds it is engineered to produce. Selecting a host that can withstand the cytotoxic effects of its own metabolic output is therefore a critical determinant of success in natural product research and development.

This guide provides an in-depth examination of the mechanisms hosts employ to tolerate cytotoxic compounds, the strategic selection of host systems, and the experimental protocols essential for evaluating and engineering this vital physiological trait.

Host Defense Mechanisms Against Cytotoxic Metabolites

When a host organism is engineered to produce a cytotoxic compound, it encounters a paradoxical "self-toxicity" problem. Successful hosts have evolved or can be engineered with sophisticated mechanisms to manage this internal threat. The defensive strategies can be broadly categorized into cellular, compartmental, and molecular mechanisms.

Cellular and Compartmental Defense Strategies

At the cellular level, hosts utilize physical and spatial strategies to minimize self-harm.

- Efflux Transport Systems: Many host organisms, particularly bacteria like E. coli and Streptomyces, encode membrane-bound efflux pumps. These proteins actively recognize and export toxic secondary metabolites from the cytoplasm or cell membrane into the extracellular environment. This is a first-line defense that reduces the intracellular concentration of the compound to sub-lethal levels [31].

- Vacuolar Sequestration: In eukaryotic hosts, such as yeasts, a key tolerance mechanism involves the transport of cytotoxic compounds into membrane-bound vacuoles. This process effectively sequesters the toxin away from critical metabolic machinery in the cytosol, mitochondria, and nucleus, thereby insulating the cell from its own products.

- Metabolic Shielding and Detoxification: Some hosts possess enzymes that can modify the toxic compound into a less active or inactive derivative. This can involve conjugation (e.g., glycosylation), functional group modification (e.g., methylation, acetylation), or even degradation. The genetics of the host strain directly influence its innate capacity for such detoxification pathways [31].

Molecular and Signaling Pathways

The interaction between a host and an endophyte—or, by analogy, a host and an introduced BGC—triggers a complex molecular dialogue. The host's immune system must be modulated to allow for a stable symbiotic relationship rather than a pathogenic one [31]. Key signaling pathways involved in this balance include:

- Jasmonic Acid (JA) Pathway: This pathway is often primed or upregulated in symbiotic relationships. It prepares the host for a faster, stronger, and more durable defense response against adverse conditions, which may include the stress induced by producing cytotoxic metabolites [31].

- Salicylic Acid (SA) Pathway: In contrast to the JA pathway, the SA pathway is often suppressed during endophytic colonization. This suppression is crucial, as SA is typically associated with pathogen defense responses; its inhibition may be necessary to establish a tolerant state for the heterologous biosynthetic machinery [31].

- Balanced Antagonism: This theory posits that the relationship is not a simple absence of defense but a precise equilibrium. The virulence factors of the microbe (or the cytotoxicity of the metabolite) are balanced against the host's defense and immune system. If the virulence/toxicity is too high, the host succumbs; if the defense is too strong, the biosynthetic process is halted [31].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and cellular mechanisms a host employs to manage cytotoxic stress.

Strategic Host Organism Selection

Choosing an appropriate heterologous host is a foundational decision that predetermines the feasibility and yield of producing cytotoxic metabolites. The selection process must move beyond technical convenience to a holistic evaluation of physiological and genetic compatibility.

Criteria for Host Selection

The ideal host for heterologously expressing cytotoxic natural products should fulfill a set of interlinked criteria, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Key Criteria for Selecting a Heterologous Host for Cytotoxic Metabolite Production

| Criterion | Description | Rationale & Physiological Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Safety & Manipulability | The host should be safe for laboratory use and have established genetic tools [32]. | Enables rigorous experimentation and genetic modification without excessive biohazard risk. |

| Growth Rate & Conditions | Should exhibit rapid growth under scalable conditions (aerobic, microaerophilic, or anaerobic) [33]. | A fast doubling time (e.g., 40-60 min for S. mutans) accelerates R&D cycles. Physiological conditions must match BGC requirements. |

| Genetic & Metabolic Background | Well-annotated genome and understood central metabolism [32] [33]. | Allows for precise metabolic engineering, including precursor supplementation and knockout of competing pathways or native nucleases. |

| Capacity for Large DNA | Versatile tools to accept and integrate large (>40 kb) DNA fragments [33]. | Most natural product BGCs are large; efficient cloning systems (e.g., NabLC) are essential for capturing entire clusters. |

| Precursor Supply | Native ability to supply key precursors (e.g., acyl-CoA, amino acids) [30]. | The host's innate physiology must provide the molecular building blocks for the target metabolite's biosynthesis. |

| Phylogenetic Relatedness | Closely related to the native producer of the BGC [33]. | Increases likelihood of shared codon usage, regulatory elements, post-translational modifications, and inherent toxin tolerance. |

Comparative Analysis of Common Host Systems

Different host systems offer distinct advantages and limitations rooted in their unique physiologies. The choice often involves a trade-off between ease of use and physiological sophistication.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Heterologous Host Organisms

| Host Organism | Key Physiological Features | Advantages | Disadvantages for Cytotoxic Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Gram-negative facultative anaerobe, rapid growth (~20 min doubling) [29]. | Extensive genetic tools, well-understood physiology, low-cost cultivation [29] [30]. | Often lacks innate tolerance; prone to protein aggregation; no native PKS/NRP machinery; produces endotoxins [29] [32]. |

| Streptomyces spp. | Gram-positive, filamentous, high-GC soil bacteria, obligate aerobes. | Native producers of many drugs; possess inherent BGC expression machinery; high tolerance for diverse metabolites [29]. | Slow growth; complex morphology; genetic manipulation can be challenging and time-consuming. |

| Bacillus subtilis | Gram-positive, non-pathogenic, facultative anaerobe [32]. | Secretes proteins directly into medium; does not produce LPS; well-studied [32]. | Produces extracellular proteases that can degrade heterologous proteins; lower expression levels than E. coli [32]. |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) | Unicellular eukaryote, rapid growth (~90 min doubling) [32]. | Post-translational modifications; proper protein folding; food-safe (GRAS status) [32]. | May hypermannosylate proteins; expensive media; may lack specific precursors common in bacteria. |

| Streptococcus mutans UA159 | Gram-positive facultative anaerobe, oral microbiota member [33]. | Model for anaerobic BGCs; short doubling time (40-60 min); naturally competent for DNA uptake [33]. | Pathogenic potential requires careful handling; primarily suited for BGCs from related Firmicutes. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Host Tolerance

A systematic experimental approach is required to evaluate a host's capacity to tolerate and produce a target cytotoxic metabolite. The workflow below outlines a generalized protocol that can be adapted for specific host-metabolite systems.

Detailed Methodology for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Growth Kinetics Analysis Under Cytotoxic Stress

- Objective: To quantitatively assess the impact of a cytotoxic metabolite on host viability and proliferation.

- Materials:

- Culture Media: Appropriate sterile liquid medium for the host (e.g., LB for E. coli, TSB for Streptomyces).

- Metabolite Stock: Purified cytotoxic metabolite in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMSO). Prepare a solvent-only control.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer (for OD~600~ measurements), microplate reader or shaking incubator with flasks, sterile 96-well plates.

- Procedure:

- Inoculate a primary culture of the host strain and grow to mid-exponential phase.

- Dilute the culture to a standardized OD~600~ (e.g., 0.05) in fresh medium.

- Aliquot the diluted culture into separate flasks or a 96-well plate.

- Add varying concentrations of the cytotoxic metabolite to the test cultures and an equivalent volume of solvent to the control.

- Incubate under optimal conditions with shaking. For 96-well plates, use a plate reader to take OD~600~ readings every 15-30 minutes.

- Plot growth curves (OD~600~ vs. time) for each condition.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key parameters:

- Lag Phase Extension: Increased duration indicates cellular stress and adaptation.

- Maximum Growth Rate (μ~max~): A significant reduction suggests metabolic burden or toxicity.

- Final Cell Density: A lower yield implies irreversible growth inhibition or cell death.

Protocol 2: Heterologous BGC Expression using the NabLC Technique

- Objective: To clone and express a large biosynthetic gene cluster from an anaerobic bacterium in Streptococcus mutans UA159 [33].

- Materials:

- Bacterial Strains: S. mutans UA159 recipient strain with a pre-integrated capture cassette.

- DNA Fragments: Genomic DNA from the donor anaerobic bacterium.

- Reagents: Competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) or comX-inducing peptide (XIP) for inducing natural competence in S. mutans [33]. Selective agar plates containing an antibiotic where the counterselection marker is sensitive.

- Procedure:

- Recipient Strain Preparation: Culture the engineered S. mutans UA159 recipient strain to early exponential phase.

- Induction of Competence: Add CSP or XIP to the culture to induce the natural competence state [33].

- Transformation: Add the donor genomic DNA, containing the target BGC, directly to the competent culture. The natural transformation machinery will internalize large DNA fragments.

- Homologous Recombination: The target BGC integrates into the host genome via homologous recombination between the capture arms (CAL and CAR) and the ends of the BGC, replacing the counterselection marker.

- Selection & Screening: Plate the transformation mixture on selective media. Surviving colonies will be those that have successfully integrated the BGC and lost the counterselection marker. Confirm integration via colony PCR and sequencing.

- Metabolite Analysis: Culture positive clones and analyze the supernatant and cell extracts for the production of the target cytotoxic metabolite using LC-MS/MS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimentation in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Heterologous Expression of Cytotoxic Metabolites

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Competence-Stimulating Peptide (CSP) | A signaling peptide that induces a state of natural competence in bacteria like S. mutans [33]. | Essential for the NabLC technique, enabling the direct uptake of large, complex BGCs from genomic DNA. |

| Counterselection Marker | A gene that confers sensitivity to a specific agent (e.g., an antibiotic), allowing for selection against its presence. | Used in the capture cassette of the NabLC system. Successful integration of the BGC removes this marker, allowing cells to grow on selective media. |

| Constitutive Promoter (e.g., CP25) | A promoter that drives continuous, high-level gene expression independent of regulatory cues [33]. | Placed upstream of the integrated BGC in the host genome to ensure consistent expression of the biosynthetic genes. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | An analytical chemistry technique for separating, identifying, and quantifying compounds in a complex mixture. | The primary method for detecting and confirming the production of the target cytotoxic metabolite in host culture extracts. |

| Global Natural Product Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) | An online platform for the organization and analysis of mass spectrometry data [28]. | Used for dereplication (avoiding rediscovery of known compounds) and identifying novel metabolites based on MS/MS fragmentation patterns. |

| Task-1-IN-1 | Task-1-IN-1, MF:C22H20N2O2, MW:344.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Isoengeletin | Isoengeletin, MF:C21H22O10, MW:434.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The physiology of the host organism is not a passive backdrop but an active and decisive factor in the heterologous production of cytotoxic secondary metabolites. A deep understanding of host defense mechanisms—from efflux pumps and signaling pathways to metabolic plasticity—is paramount. Strategic host selection, guided by criteria such as phylogenetic relatedness, genetic tractability, and innate precursor supply, provides a foundation for success. Furthermore, the experimental frameworks and tools outlined in this guide, from growth kinetic analyses to advanced cloning techniques like NabLC, equip researchers with the means to rigorously evaluate and engineer host tolerance. By systematically addressing the challenge of self-toxicity, scientists can more effectively harness the vast potential of heterologous biosynthesis to access novel cytotoxic compounds, thereby accelerating the pipeline for drug discovery and development.

From Cloning to Production: Practical Workflows and Successful Case Studies

The exploration of microbial natural products (NPs), a cornerstone of pharmaceutical and agricultural discovery, has been revolutionized by genome sequencing technologies. These advances have revealed a vast untapped reservoir of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encoding potential novel compounds [19]. However, a significant challenge persists: the majority of these BGCs are silent or cryptic under standard laboratory conditions, and a large proportion of microbial sources are uncultivable [34]. Heterologous expression—the process of capturing and expressing these BGCs in a well-characterized host organism—has emerged as a pivotal strategy to overcome these barriers, enabling the discovery of new bioactive metabolites and the efficient production of known compounds [35] [22].

Within this strategy, the initial steps of BGC capture and assembly are critical bottlenecks. The success of downstream expression and product isolation hinges on the efficient and faithful reconstruction of often large and complex BGCs. This technical guide focuses on three advanced methods for this purpose: Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR), Cas9-Assisted Targeting of Chromosome segments (CATCH), and Linear-Linear Homologous Recombination (LLHR). These techniques are framed within the overarching thesis that careful host organism selection is fundamental to heterologous expression research. The chosen host must not only provide a permissive background for BGC expression but also be compatible with the genetic engineering tools used for cluster capture and refactoring [34] [22].

The selection of an appropriate BGC capture method is influenced by multiple factors, including BGC size, the availability of starting DNA, and the desired speed and fidelity of the process. The following sections provide a detailed examination of three prominent techniques.

Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR)

Principles and Workflow

Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) is a in vivo cloning technique that harnesses the innate homologous recombination machinery of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The method relies on a linear TAR vector and genomic DNA fragments containing the target BGC [22].

The TAR vector is engineered with two "hooks" or homology arms, each typically 40-500 base pairs long, which are specific to the 5' and 3' ends of the target BGC. When this vector and co-transformed genomic DNA fragments are introduced into yeast cells, the host's recombination system mediates the assembly of the complete BGC into a single, circular yeast artificial chromosome (YAC). This YAC can be subsequently isolated and transferred into a bacterial host for further manipulation and storage.

Figure 1: The TAR cloning workflow for BGC capture.

Key Experimental Protocol

A standard TAR cloning protocol involves several key stages [22]:

Vector Construction: A TAR vector is assembled containing:

- A yeast centromere and autonomous replication sequence (CEN/ARS) for maintenance in yeast.

- A yeast selectable marker (e.g.,

URA3orHIS3). - A bacterial origin of replication and selectable marker for subsequent shuttling to E. coli.

- Two homology arms targeting the flanking regions of the BGC.

Preparation of Genomic DNA: High-molecular-weight genomic DNA is partially digested with restriction enzymes or sheared mechanically to generate fragments larger than the target BGC.

Yeast Transformation: The linearized TAR vector and genomic DNA fragments are co-transformed into competent yeast cells using a method such as the lithium acetate/polyethylene glycol (LiAc/PEG) protocol.

Selection and Validation: Yeast transformants are selected on appropriate dropout media. Correct clones are identified by colony PCR, restriction analysis, or full sequencing.

Cas9-Assisted Targeting of Chromosome Segments (CATCH)

Principles and Workflow

Cas9-Assisted Targeting of Chromosome Segments (CATCH) is an in vitro method that utilizes the CRISPR-Cas9 system for the precise excision of large genomic regions. This strategy allows for the targeted capture of a BGC directly from a native microbial chromosome, avoiding the need for library construction [34].

The CATCH method involves designing two guide RNAs (gRNAs) that bind sequences flanking the target BGC. The Cas9 nuclease, complexed with these gRNAs, introduces double-strand breaks at these specific sites, liberating the entire BGC as a linear DNA fragment. This fragment can then be captured and circularized into a suitable vector using methods such as Gibson Assembly or ligation.

Figure 2: The CATCH method for precise BGC excision.

Key Experimental Protocol

The CATCH protocol can be broken down into the following steps [34]:

gRNA Design and Synthesis: Two gRNAs are designed to target sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the BGC. The gRNAs can be synthesized in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase.

Cas9 Cleavage Reaction: Purified Cas9 nuclease is complexed with the gRNAs to form ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). This RNP mixture is then incubated with high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the native producer to execute the double-strand breaks.

Fragment Isolation and Purification: The linear BGC fragment is separated from the rest of the genomic DNA by gel electrophoresis (e.g., using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for large fragments) and extracted from the gel.

Ligation and Circularization: The purified linear fragment is ligated into a predigested capture vector containing compatible ends, or assembled using an isothermal method like Gibson Assembly, which also serves to circularize the construct.

Linear-Linear Homologous Recombination (LLHR)

Principles and Workflow

Linear-Linear Homologous Recombination (LLHR) is a powerful in vitro cloning strategy that leverages bacterial recombinase systems, such as the RecET system from E. coli or the λ-Red system from bacteriophage lambda. This method is particularly useful for direct cloning and manipulation of large BGCs in engineered E. coli strains [22].

In LLHR, a linear vector backbone and a linear donor DNA fragment (the target BGC) are co-electroporated into a bacterial strain that is induced to express recombinase proteins (e.g., RecE/RecT or Redα/Redβ). These proteins facilitate homologous recombination between short homology arms (as short as 50 bp) present on the ends of both the vector and the insert, resulting in a circular, replicable plasmid.

Figure 3: LLHR cloning using bacterial recombinase systems.

Key Experimental Protocol

A typical LLHR protocol, often referred to as recombineering, involves [22]:

Strain Preparation: An E. coli host strain (e.g., GB2005 or GB2006) harboring a plasmid with an inducible recombinase system (e.g., pSC101-PRha-αβγA-PBAD-ccdA for λ-Red) is grown and induced with L-rhamnose and/or L-arabinose.

Preparation of Linear DNA: The linear vector backbone is generated by PCR or restriction digestion. The donor BGC DNA is prepared as a linear fragment, either by PCR, synthesis, or extraction from a native source. Both molecules must possess terminal homology arms.

Electroporation: The linear vector and insert are co-electroporated into the induced, recombinase-expressing E. coli cells.

Outgrowth and Selection: Cells are allowed to recover in liquid medium to permit recombination and plasmid circularization, after which they are plated on selective media to isolate correct clones.

Comparative Analysis of BGC Capture Techniques

Selecting the optimal method for a given project requires a clear understanding of the strengths and limitations of each technique. The table below provides a structured comparison based on key performance parameters.

Table 1: Technical comparison of advanced BGC capture methods

| Feature | TAR | CATCH | LLHR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | In vivo yeast homologous recombination | In vitro CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage | In vivo/in vitro bacterial recombinase-mediated recombination |

| Typical Insert Size | Very large (>100 kb) | Large (10-100 kb) | Large (10-100 kb) |

| Key Advantage | Captures very large clusters directly from genomic DNA; high fidelity | Precise, targeted excision; no library required | Highly efficient in specialized E. coli strains; uses short homology arms |

| Primary Host | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | In vitro system | Engineered E. coli |

| Critical Reagents | TAR vector, yeast strain, genomic DNA | Cas9 protein, custom gRNAs, genomic DNA | Linear vector/insert, E. coli strain with inducible recombinase |

| Typical Workflow Duration | Several weeks | 1-2 weeks | 1-2 weeks |

| Success Rate (Cloning) | Varies; can be high for suitable constructs | High with optimized gRNAs and DNA quality | Very high in optimized systems |

The choice of method is also influenced by the success rates of heterologous expression in general. Large-scale studies have reported varying success rates, which contextualizes the performance of these capture techniques.

Table 2: Heterologous expression success rates from large-scale studies

| BGC Source | BGCs Cloned | Cloning Success Rate | BGCs Expressed | Expression Success Rate | New NP Families Isolated | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharothrix espanaensis | 17 | 68% | 4 | 11% | 2 | [19] |

| 17 various Streptomyces & Bacillus spp. | 43 | 100% | 7 | 16% | 5 | [19] |

| 100 Streptomyces spp. | 58 | 72% | 15 | 24% | 3 | [19] |

| 27 various bacterial phyla | 83 | 86% | 27 | 32% | 3 | [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing TAR, CATCH, and LLHR requires a suite of specialized biological reagents and genetic tools. The following table details key components for establishing these platforms.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for advanced BGC capture

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TAR Vector System | Yeast-E. coli shuttle vector with CEN/ARS, markers, and multiple cloning site for homology arm insertion. | Capturing large PKS and NRPS clusters directly from genomic DNA in yeast [22]. |

| RecET / λ-Red System | Plasmid encoding inducible recombinase genes (e.g., Redα/Redβ/Redγ or RecE/RecT). | LLHR in E. coli for markerless DNA manipulation and BGC assembly using short homology arms [22]. |

| Cas9 Nuclease & gRNAs | CRISPR-associated protein 9 and target-specific guide RNAs for precise DNA cleavage. | CATCH method for excising specific BGCs from native chromosomal DNA [34]. |

| AntiSMASH | Bioinformatics platform for BGC identification, annotation, and boundary prediction. | Essential first step for all methods to define target cluster and design homology arms/gRNAs [34] [22]. |

| PhiC31 Integrase System | Site-specific recombination system for integrating cloned BGCs into the genome of Streptomyces hosts. | Stable chromosomal integration of BGCs for heterologous expression in a defined genetic locus [22]. |

| RMCE Cassettes | Recombineering cassettes (e.g., Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox) for precise, multi-copy genomic integration. | Enables copy-number optimization and stable expression of BGCs in engineered chassis strains like S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 [22]. |

| Pelirine | Pelirine, MF:C21H26N2O3, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Taxachitriene B | Taxachitriene B, MF:C30H42O12, MW:594.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Heterologous Host Selection

The choice of BGC capture method is intrinsically linked to the selection of the eventual heterologous host. Streptomyces species have emerged as the most versatile and widely used chassis for expressing complex BGCs from diverse microbial origins [35]. This preference is driven by their native capacity to produce a wide array of secondary metabolites, providing a rich internal pool of essential biosynthetic precursors, and their familiarity with the complex enzymatic machinery required for compound maturation (e.g., for polyketides and nonribosomal peptides) [34] [22].

The development of optimized Streptomyces chassis strains, such as S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 which has multiple endogenous BGCs deleted and contains orthogonal recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites, is a key advancement [22]. These strains provide a "clean" metabolic background that minimizes interference with native metabolism and simplifies the detection of heterologously produced compounds. Furthermore, the integration of captured BGCs into such defined loci via systems like PhiC31, Cre-lox, or Vika-vox allows for reliable comparison of expression levels across different clusters and enables yield optimization through copy number control [22].

Therefore, the initial decision to use TAR, CATCH, or LLHR should be made with the final Streptomyces host in mind. The capture vector must be designed with the appropriate genetic elements (e.g., origins of transfer, integration sites, selectable markers) that are functional in the intermediate hosts (yeast or E. coli) and compatible with the final conjugation and integration steps into the Streptomyces chassis. This end-to-end strategy ensures that valuable captured BGCs can be efficiently transferred and robustly expressed, ultimately unlocking their potential for novel natural product discovery.

The selection of an appropriate host organism is a critical strategic decision in heterologous natural product expression research. Beyond traditional model chassis like Escherichia coli, a new generation of specialized hosts including methanogenic archaea, proteobacteria, and Streptomyces species are being developed for their unique metabolic capabilities and biosynthetic potential [35] [18] [36]. The effectiveness of these hosts hinges on the availability of genetic toolboxes that enable precise control of gene expression at both transcriptional and translational levels. These toolboxes—comprising promoters, ribosome binding sites (RBSs), and inducible systems—allow researchers to fine-tune metabolic pathways, balance enzyme expression, and minimize metabolic burden while maximizing product yield [36].

The emerging field of broad-host-range synthetic biology reconceptualizes host selection as an active design parameter rather than a passive platform, treating the microbial chassis as a tunable component that influences genetic device performance through resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [18]. This paradigm shift underscores the necessity for well-characterized, standardized genetic tools that function predictably across diverse microbial systems, enabling researchers to harness the full potential of non-model organisms for natural product biosynthesis.

Core Components of Genetic Toolboxes

Promoter Libraries for Transcriptional Control

Promoters serve as the primary regulatory gatekeepers for transcriptional initiation, with strength and regulation being key determinants of their utility in metabolic engineering. Comprehensive promoter libraries have been developed for diverse microorganisms, enabling graded transcriptional control across several orders of magnitude.

Table 1: Characterized Promoter Libraries Across Diverse Microorganisms

| Host Organism | Library Size | Dynamic Range | Notable Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanococcus maripaludis [36] | 81 constitutive promoters | ~10â´-fold | Identification of base composition rules for strong archaeal promoters; weak promoters enhanced by up to 120-fold | Archaeal biology studies, COâ‚‚ fixation, protein expression |

| Zymomonas mobilis [37] | 38 promoters (19 strong, 9 medium, 10 weak) | Classified by strength categories | Strength predicted from systems biology datasets (microarray, RNA-Seq, proteomics) | Metabolic engineering for biofuels and biochemicals |

| Proteobacteria [38] | 12 inducible systems | >50-fold induction in 8/9 species | Function across diverse species; variant libraries created for improved performance | Broad-host-range synthetic biology, biosensors |

The development of these libraries has revealed organism-specific design principles. For instance, in M. maripaludis, strong promoters were found to possess distinct base composition patterns, enabling the rational remodeling of weak promoters to enhance their activity by up to 120-fold [36]. In Z. mobilis, promoter strength was successfully predicted through systematic analysis of omics datasets, with downstream gene expression values providing reliable indicators of promoter activity [37].

Ribosome Binding Sites (RBS) for Translational Control

Ribosome binding sites control the initiation of translation, working in concert with promoters to determine final protein expression levels. RBS libraries provide a means to fine-tune translation efficiency without altering promoter strength or coding sequences.

Table 2: Characterized RBS Libraries Across Diverse Microorganisms

| Host Organism | Library Size | Dynamic Range | Prediction Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanococcus maripaludis [36] | 42 RBS sequences | ~100-fold | Experimental characterization | Enables precise tuning of translation initiation |

| Zymomonas mobilis [37] | 4 synthetic RBSs | High correlation (R² > 0.9) | RBS calculator prediction | Validation of computational design approaches |