Strategic Microbial Chassis Selection: A Comprehensive Framework for Synthetic Biology in Biomedicine

This article provides a systematic framework for selecting and optimizing microbial chassis in synthetic biology, specifically tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategic Microbial Chassis Selection: A Comprehensive Framework for Synthetic Biology in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for selecting and optimizing microbial chassis in synthetic biology, specifically tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles from genetic tractability to host-circuit interactions, explores emerging non-model organisms with specialized capabilities, details advanced engineering strategies like genome streamlining and combinatorial optimization, and establishes validation protocols for chassis performance. By integrating technical specifications with application-specific requirements, this guide enables rational chassis selection to accelerate the development of novel therapeutics, vaccines, and biomanufacturing platforms in biomedical research.

Core Principles and Emerging Hosts: Laying the Groundwork for Effective Chassis Selection

In synthetic biology, a chassis organism is the foundational host cell engineered to carry out specific synthetic functions, serving as the physical framework that supports the execution of a synthetic system [1] [2]. The selection of an appropriate chassis represents one of the most critical early-stage decisions in synthetic biology project design, significantly influencing the success and efficiency of research and development efforts [1]. Historically, synthetic biology has been biased toward using a narrow set of traditional organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to their well-characterized genetics and extensive engineering toolkits [3]. However, this traditional approach often treats host-context dependency as an obstacle rather than a design opportunity [3].

The emerging paradigm of broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology challenges this conventional approach by reconceptualizing the chassis as an integral design variable that should be rationally chosen to optimize system function [3]. This perspective positions microbial chassis as tunable components rather than passive platforms, enabling researchers to leverage host-specific traits to construct new functions or improve native functions [3]. The chassis can serve as both a "functional" module, where innate traits are integrated into the design, and a "tuning" module, where the host environment adjusts the performance of genetic circuits [3]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the key selection criteria for microbial chassis organisms, framed within the context of advancing synthetic biology research and drug development applications.

Core Selection Criteria for Microbial Chassis

Selecting an optimal chassis organism requires careful consideration of multiple interconnected biological and practical factors. The primary criteria can be categorized into genetic tractability, physiological characteristics, safety considerations, and application-specific compatibility.

Genetic Tractability and Tool Availability

Genetic tractability refers to how easily an organism can be genetically manipulated, including the availability of genetic tools and resources [1]. This encompasses transformation protocols, vectors, genome-editing technologies, and standardized genetic parts [1] [4]. Model organisms traditionally excel in this category due to decades of research investment. For example, E. coli and S. cerevisiae have extensive collections of characterized biological parts, including promoters, ribosomal binding sites, and terminators, as well as robust DNA assembly methods like BioBrick standardization [4].

The expanding synthetic biology toolkit now includes advanced genome editing technologies, particularly CRISPR-based systems, which are being adapted for non-model organisms [2] [5]. The availability of well-characterized constitutive and inducible promoters is also crucial for precise genetic control [5]. Furthermore, the development of broad-host-range tools, including modular vectors and host-agnostic genetic devices such as the Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA), facilitates the expansion of chassis selection beyond traditional models [3].

Physiological and Metabolic Characteristics

Growth characteristics significantly impact the feasibility of large-scale production and include growth rate, nutrient requirements, and stress tolerance [1]. Fast-growing organisms like E. coli are preferred for rapid prototyping and iterations [1]. Beyond growth rate, metabolic versatility and the presence of native biosynthetic pathways compatible with the target application are crucial considerations [3].

Stress tolerance encompasses robustness to environmental conditions such as temperature extremes, osmotic pressure, pH variations, and toxin exposure [3]. Extremophiles offer unique advantages for industrial processes requiring harsh conditions [2]. Additionally, metabolic burden—the impact of engineered genetic circuits on host fitness—must be considered, as it can lead to reduced growth rates and genetic instability [3] [2].

Safety and Regulatory Considerations

Biosafety is paramount, particularly for applications with environmental release potential or therapeutic use [1] [2]. Chassis organisms should ideally be non-pathogenic and Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) [1]. Model organisms like E. coli K-12 and S. cerevisiae have long safety histories in laboratory and industrial settings [1]. For engineered organisms that might interact with environments or humans, containment strategies such as auxotrophies or genetic barriers to horizontal gene transfer become critical design considerations [2].

Application-Specific Compatibility

Pathway compatibility ensures the chassis supports the intended synthetic function [1]. This includes the availability of necessary precursors, cofactors, energy sources, and cellular machinery for proper folding, modification, and localization of target molecules [3] [1]. For instance, cyanobacteria are ideal for photosynthetic applications, while Clostridium species suit anaerobic processes [1]. Expressing complex eukaryotic proteins like G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) often requires chassis with post-translational modification capabilities, making yeast preferable to bacteria [3].

Table 1: Comprehensive Chassis Selection Criteria

| Criterion Category | Specific Factors | Traditional Chassis | Emerging Chassis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tractability | Transformation efficiency, Editing tools, Part libraries, Standardized assembly | Excellent in E. coli and S. cerevisiae | Improving in non-models via BHR tools |

| Physiological Characteristics | Growth rate, Stress tolerance, Metabolic burden, Resource allocation | Fast growth, Limited stress tolerance | Variable growth, Specialized tolerances |

| Safety Profile | Pathogenicity, Environmental persistence, Containment strategies | GRAS status established | Requires careful evaluation |

| Application Compatibility | Native metabolism, Post-translational modifications, Precursor availability | May require extensive engineering | Innate capabilities often exploitable |

| Practical Considerations | Cost, Scalability, Regulatory acceptance, IP landscape | Low cost, Established protocols | Variable cost, Developing protocols |

Quantitative Comparison of Chassis Organisms

Systematic comparison of chassis performance across multiple parameters enables data-driven selection. Recent studies have quantitatively analyzed how identical genetic circuits behave differently across various hosts, revealing significant variations in output signal strength, response time, growth burden, and metabolic impacts [3].

Performance Metrics Across Bacterial Species

Research has demonstrated that host selection can influence genetic circuit performance through resource allocation mechanisms, transcriptional and translational capacity, and regulatory crosstalk [3]. For example, a study comparing inducible toggle switch circuits across Stutzerimonas species revealed divergent bistability, leakiness, and response times correlated with host-specific gene expression patterns [3]. These performance variations provide a spectrum of characteristics that synthetic biologists can leverage when choosing a functional system tailored to specific application requirements [3].

Case Study: Thermus thermophilus as a Specialized Chassis

The thermophile Thermus thermophilus HB27 exemplifies how niche physiological attributes can be leveraged for specific applications. This organism grows optimally at 65-75°C, providing inherent advantages for producing thermostable proteins while reducing contamination risks [5]. Recent engineering efforts have enhanced its chassis capabilities through multiple strategic approaches:

- Promoter Engineering: Screening 13 endogenous promoter regions identified P0984 with 13-fold higher activity than control promoters [5].

- Genome Reduction: Construction of a plasmid-free strain (HB27ΔpTT27) removed 270 kb of genomic DNA, creating a auxotrophy-based selection system [5].

- Protease Knockouts: Systematic deletion of 16 predicted non-essential protease genes significantly reduced recombinant protein degradation [5].

These modifications cumulatively improved T. thermophilus as a dedicated chassis for thermostable protein production, demonstrating the potential of specialized chassis development [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Selected Chassis Organisms

| Organism | Optimal Growth Temp (°C) | Doubling Time (min) | Transformation Efficiency | Specialized Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | 37 | 20-30 | High (10â·-10â¹ CFU/μg) | Rapid prototyping, High-yield production |

| S. cerevisiae | 30 | 90-120 | Moderate (10â´-10ⶠCFU/μg) | Eukaryotic protein production, Metabolic engineering |

| B. subtilis | 37 | 30-60 | Moderate (10â´-10ⶠCFU/μg) | Protein secretion, Industrial fermentation |

| P. putida | 30 | 60-90 | Low to moderate | Bioremediation, Stress-prone processes |

| T. thermophilus | 65-75 | 60-90 | Improved after engineering (100-fold increase) | Thermostable protein production |

| R. palustris | 30-35 | 180-300 | Variable | Photosynthetic applications, Metabolic versatility |

Experimental Framework for Chassis Evaluation

A systematic approach to chassis evaluation ensures comprehensive assessment of suitability for specific synthetic biology applications. The following experimental framework provides a standardized methodology for chassis characterization.

Genetic Tool Compatibility Assessment

Protocol: Transformation Efficiency and Genetic Accessibility

- Vector Compatibility Testing: Introduce broad-host-range vectors (e.g., SEVA system) with standardized origin of replication and selection markers [3].

- Transformation Method Optimization: Evaluate natural competence, heat shock, electroporation, or conjugation protocols [5].

- Editing Efficiency Quantification: Implement CRISPR-Cas systems adapted for the target chassis and measure editing efficiency [5].

- Part Characterization: Test library of standardized promoters, RBSs, and terminators to determine context-dependent behavior [4].

Expected Outcomes: Quantitative transformation efficiency (CFU/μg DNA), editing efficiency (%), and characterization of genetic part performance across different genomic contexts.

Physiological Characterization Protocol

Protocol: Growth and Metabolic Profiling

- Growth Kinetics Analysis: Measure growth rates in standard and application-relevant conditions using spectrophotometry (OD600) and dry cell weight [1].

- Stress Tolerance Assays: Expose to temperature, pH, osmotic, and oxidative stress conditions while monitoring viability [3] [2].

- Metabolic Burden Assessment: Introduce varying genetic load (plasmid copy number, circuit complexity) and quantify impact on growth rate and resource allocation [3].

- Resource Allocation Profiling: Use RNA sequencing and ribosome profiling to measure transcriptional and translational capacity [3].

Expected Outcomes: Growth rate constants, stress tolerance thresholds, burden coefficients, and resource allocation maps under different engineered conditions.

Application-Specific Functional Testing

Protocol: Circuit Performance and Metabolic Compatibility

- Standardized Circuit Transfer: Implement identical genetic circuits (e.g., toggle switches, oscillators) across different chassis to measure performance variations [3].

- Pathway Integration Testing: Introduce target biosynthetic pathways and measure precursor availability, intermediate accumulation, and product yield [1].

- Metabolic Crosstalk Analysis: Use metabolomics and transcriptomics to identify interactions between native metabolism and engineered pathways [2].

- Long-Term Stability Assessment: Conduct serial passaging to evaluate genetic stability and evolutionary dynamics of engineered strains [3].

Expected Outcomes: Circuit performance parameters (response time, dynamic range, leakiness), pathway efficiency metrics, crosstalk identification, and genetic stability measurements.

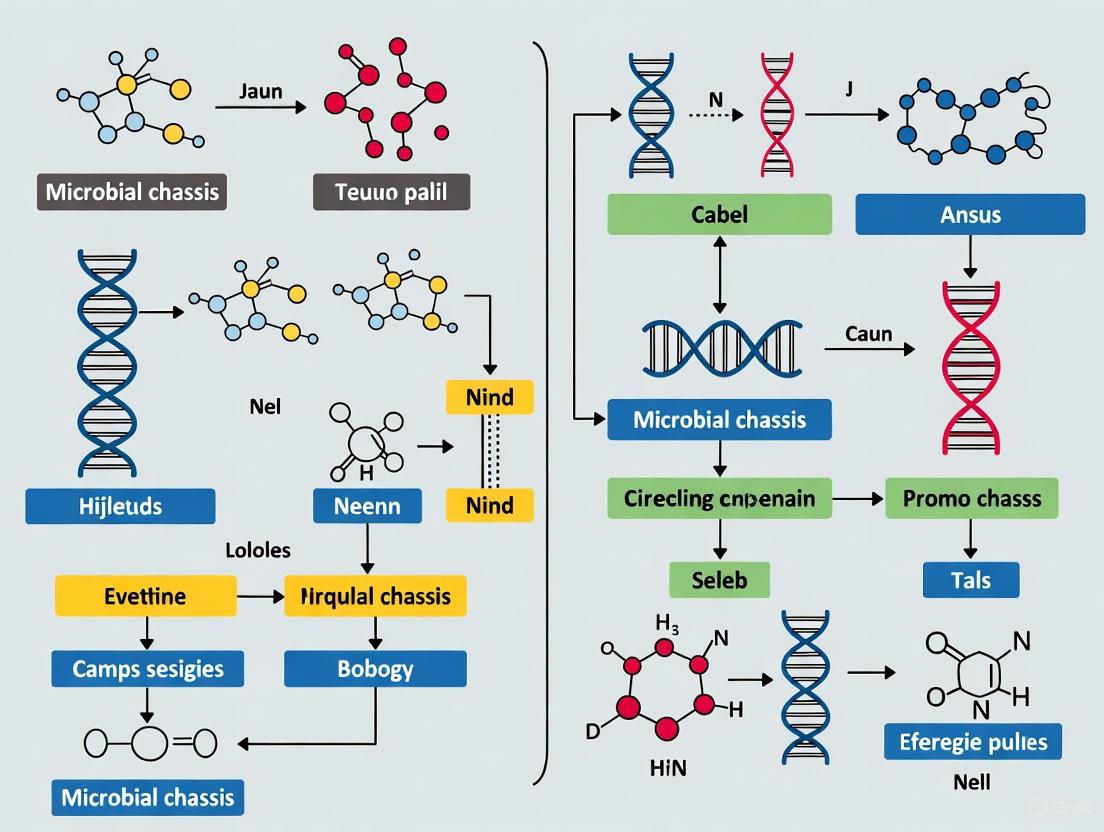

Diagram 1: Experimental Framework for Chassis Evaluation. This workflow outlines the comprehensive multi-parameter assessment strategy for evaluating potential chassis organisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful chassis development and evaluation requires specific research reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials and their applications in chassis characterization and engineering.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Chassis Development and Evaluation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors | SEVA system, RK2-based vectors | Enable genetic manipulation across diverse hosts | Standardized origin of replication, selection markers [3] |

| Genome Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas, recombinase systems | Targeted genome modifications | Optimize for GC content, temperature requirements [5] |

| Characterized Genetic Parts | Promoter libraries, RBS collections, terminators | Standardized genetic control | Context-dependent performance requires validation [4] |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent proteins, β-galactosidase, luciferase | Quantitative measurement of gene expression | Consider thermostability for non-mesophilic hosts [5] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, auxotrophic complementation | Selective pressure for engineered strains | Antibiotic-free systems preferred for industrial use [5] |

| Metabolic Profiling Tools | GC/MS, LC/MS, NMR systems | Analysis of metabolic fluxes and pathway interactions | Essential for identifying metabolic bottlenecks [2] |

| High-Throughput Screening | Microfluidics, robotic liquid handling, plate readers | Rapid characterization of genetic variants | Enables combinatorial testing of parts and conditions [4] |

| Chloramultilide B | Chloramultilide B, MF:C39H42O14, MW:734.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Epostatin | Epostatin, MF:C23H33N3O5, MW:431.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Engineering Strategies for Chassis Optimization

Beyond selection of natural isolates, synthetic biologists are increasingly employing advanced engineering strategies to create enhanced chassis organisms with customized properties.

Genome Reduction and Minimization

Minimal genome chassis represent an extreme approach to reducing complexity and enhancing predictability. Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn3.0, containing only 473 genes, demonstrates that a living cell can function with a minimal gene set, providing a simplified background for engineering with reduced interference from unnecessary genetic elements [2]. Genome reduction strategies include:

- Targeted Deletion: Systematic removal of non-essential genes, mobile elements, and redundant pathways [5].

- Pathway Consolidation: Streamlining metabolic networks to eliminate parallel routes and regulatory complexity [2].

- Codon Reassignment: Unifying codon usage to simplify genetic code implementation [2].

These approaches reduce metabolic burden, improve genetic stability, and enhance resource allocation toward engineered functions [2].

Proteome and Resource Allocation Reengineering

The "chassis effect" largely stems from how different hosts allocate limited cellular resources to endogenous processes versus engineered functions [3]. Recent studies demonstrate that resource competition and growth feedback shape genetic circuit behavior in unpredictable ways [3]. Engineering strategies to address these challenges include:

- Promoter-Toolkit Development: Screening endogenous promoters to identify strong, constitutive options for high-level expression [5].

- Protease Engineering: Targeted deletion of non-essential protease genes to reduce recombinant protein degradation [5].

- Ribosome Engineering: Modifying translation machinery to alter resource allocation patterns [3].

- Chassis-Rewiring: Adjusting global regulatory networks to better accommodate synthetic circuits [3].

Diagram 2: Advanced Engineering Strategies for Chassis Optimization. This diagram illustrates the multi-faceted approaches for enhancing chassis organisms beyond natural isolation.

The ideal chassis organism does not represent a universal solution but rather a platform specifically matched to application requirements through systematic evaluation and engineering. The paradigm shift toward broad-host-range synthetic biology emphasizes host selection as an active design parameter rather than a default choice [3]. This perspective acknowledges that host-context dependency, traditionally viewed as an obstacle, can be leveraged as a tuning mechanism for genetic circuit performance [3].

Future directions in chassis development will be increasingly interdisciplinary, incorporating machine learning-guided design, automated high-throughput characterization, and integrated multi-omics analyses [2]. The expanding repertoire of chassis organisms, from minimal cells to extremophiles and non-model microbes, provides an increasingly diverse palette for synthetic biologists to address challenges in medicine, biofuel production, environmental remediation, and industrial biotechnology [2]. As the field progresses, rational chassis selection and engineering will continue to play a pivotal role in shaping a more sustainable and innovative bio-based economy.

The field of synthetic biology has traditionally been dominated by a handful of model organisms such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. However, the expanding demand for sustainable bioprocesses and novel bioactive compounds has exposed the limitations of these conventional hosts. This whitepaper examines the systematic selection and engineering of non-model microbial chassis, highlighting their untapped potential due to native metabolic capabilities, stress tolerance, and substrate utilization profiles. We provide a technical framework incorporating ecological, metabolic, and genetic criteria for chassis selection, supported by experimental protocols for their domestication and engineering. Finally, we present a systematic approach to guide researchers in selecting appropriate non-model hosts for specific biotechnological applications, emphasizing the integration of techno-economic and sustainability analyses at early developmental stages.

The reliance on model microorganisms in synthetic biology has created a significant bottleneck in biotechnological innovation. While E. coli and S. cerevisiae offer well-characterized genetics and extensive engineering toolkits, they often lack the specialized metabolic capabilities and robustness required for industrial applications and complex natural product synthesis [6]. Non-model microorganisms represent a vast reservoir of genetic diversity and unique physiological traits that are difficult or impossible to engineer into conventional hosts from first principles [7] [8]. These organisms have evolved specialized metabolisms, stress resistance mechanisms, and substrate utilization capabilities that make them ideally suited for specific bioprocess applications.

The paradigm is shifting from engineering heterologous pathways in model hosts to leveraging endogenous production capabilities in native producers [6]. This approach capitalizes on evolutionary optimization, where non-model hosts already possess the necessary enzymatic machinery, cofactor balancing, and cellular infrastructure for target compound production. This review provides a comprehensive framework for selecting and engineering non-model microbial chassis, with emphasis on systematic criteria that align host capabilities with application requirements.

Selection Criteria for Non-Model Microbial Chassis

Selecting an appropriate non-model organism requires a multidimensional analysis that extends beyond conventional genetic tractability considerations. A systematic evaluation should encompass metabolic, physiological, ecological, and genetic factors to identify hosts with innate advantages for specific applications.

Metabolic and Physiological Considerations

Substrate Utilization and Metabolic Efficiency: Potential chassis should be evaluated for their ability to utilize low-cost, sustainable feedstocks. Of particular interest are one-carbon (C1) compounds including methanol, formate, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide, which can be derived from or converted to COâ‚‚, supporting a circular carbon economy [7]. Organisms such as Zymomonas mobilis utilize the Entner-Doudoroff (ED) pathway under anaerobic conditions, providing exceptional glycolytic flux with reduced ATP yield, creating a favorable metabolic background for production of certain compounds [9].

Stress Tolerance and Robustness: Industrial bioprocesses often involve exposure to inhibitory compounds, osmotic stress, temperature fluctuations, and product toxicity. Non-model organisms from extreme environments offer inherent robustness against these conditions. For example, Halomonas bluephagenesis demonstrates high osmotolerance for polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production, while Pseudomonas putida exhibits exceptional solvent tolerance and ability to break down lignin [9] [8].

Product Formation and Yield: Native producers often achieve higher yields of complex natural products through pre-existing optimized metabolic pathways. Engineered Streptomyces species, for instance, can produce complex antibiotics through endogenous biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that would be challenging to reconstruct in heterologous hosts [6] [10].

Table 1: Promising Non-Model Microbes and Their Native Capabilities

| Microorganism | Native Capabilities | Potential Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zymomonas mobilis | High glycolytic flux via ED pathway, high ethanol tolerance | Biofuels, D-lactate, biorefinery platforms | [9] |

| Pseudomonas putida | Solvent tolerance, lignin degradation, diverse substrate utilization | Bioremediation, bioplastics, chemical production | [7] [8] |

| Cupriavidus necator | Chemolithoautotrophic growth on Hâ‚‚ and COâ‚‚ | COâ‚‚ valorization, bioplastics | [7] |

| Lacticaseibacillus species | Food-grade status, efficient sugar fermentation | Food ingredients, therapeutic proteins | [6] |

| Streptomyces species | Extensive secondary metabolite repertoire | Antibiotics, anticancer drugs | [6] [10] |

Ecological and Safety Considerations

Environmental Persistence: For applications involving environmental biosensing or bioremediation, chassis persistence in the target environment is crucial. This requires tolerance to local biotic (e.g., microbial competition) and abiotic (e.g., pH, temperature, oxygen availability) factors [11]. Benchtop incubation studies with environmental samples can help characterize ecological persistence.

Biocontainment Strategies: Environmental applications demand stringent biocontainment to prevent uncontrolled proliferation and gene transfer. Successful approaches include toxin-antitoxin systems, auxotrophy, inducible kill switches, and xenobiology [11]. The NIH recommends an escape frequency of less than 1 in 10⸠cells for deployed organisms [11].

Genetic Tractability and Tool Development

Genetic Accessibility: While non-model organisms may lack established genetic tools, several strategies can overcome this limitation. Broad-host-range plasmids facilitate initial genetic modifications [11], while understanding methylation patterns allows engineers to bypass restriction systems that target foreign DNA [8].

Genome Editing Capabilities: CRISPR-based systems have been adapted for diverse microbial species, enabling gene knockouts, knockdowns via interference, and transcriptional activation [9] [8]. Additionally, recombinase-based systems, transposases, and their CRISPR-hybrid counterparts facilitate genomic integration in non-model bacteria [11].

Engineering and Domestication Strategies

Genome Reduction and Optimization

Genome reduction through top-down approaches (systematic removal of unnecessary genomic regions) enhances genomic stability, improves growth characteristics, and eliminates competing pathways [10]. Key strategies include:

- Deletion of mobile genetic elements: Removal of insertion sequences (IS) and prophages reduces random mutations. An IS-free E. coli strain showed 20-25% improvement in recombinant protein production [10].

- Elimination of antibiotic clusters: Streptomyces albus with 15 deleted native antibiotic gene clusters demonstrated 2-fold higher production of heterologously expressed biosynthetic gene clusters [10].

- Pathway simplification: Reducing metabolic complexity improves predictability and controllability while redirecting cellular resources toward product formation [10].

Metabolic Engineering Approaches

Overcoming Dominant Metabolism: Organisms with strong native pathways require strategic engineering to redirect carbon flux. In Z. mobilis, researchers developed a Dominant-Metabolism Compromised Intermediate-Chassis (DMCI) strategy by introducing a low-toxicity but cofactor-imbalanced 2,3-butanediol pathway before engineering for D-lactate production, achieving titers exceeding 140 g/L from glucose [9].

Orthogonal Pathway Design: Linear and orthogonal pathways with high flux potential, such as the reductive glycine pathway (rGlyP), are typically simpler to implement than circular, autocatalytic cycles, which require tight control at branch points to prevent intermediate depletion [7].

Systems Biology Approaches: Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) constrained with enzyme kinetics (ecModels) successfully predict metabolic fluxes and identify rate-limiting steps. The eciZM547 model for Z. mobilis accurately simulated carbon distribution between acetate and acetoin under aerobic conditions, guiding rational strain design [9].

Tool Development for Genetic Manipulation

Engineering non-model hosts requires developing customized genetic tools:

- Promoter and RBS engineering: Identification and characterization of native constitutive and inducible regulators enable precise metabolic control [9].

- Vector systems: Broad-host-range plasmids adapted with compatible origins of replication and antibiotic markers facilitate initial genetic studies [11].

- DNA delivery optimization: Understanding host-specific restriction-modification systems allows engineers to modify cloning strains to mimic native methylation patterns, improving transformation efficiency [8].

Experimental Workflows for Chassis Development

The development of non-model chassis follows a systematic workflow from selection to performance validation. The diagram below outlines this comprehensive process.

Multi-Omics Characterization

Comprehensive omics profiling provides insights into central carbon metabolism and regulatory networks:

- Genome sequencing and annotation: Essential first step identifying metabolic potential, pathogenic elements, and restriction-modification systems [10].

- Transcriptomics and proteomics: Reveal gene expression patterns and post-translational regulatory mechanisms under different growth conditions [7].

- Fluxomics and metabolomics: Quantify metabolic flux distributions and intracellular metabolite pools, guiding pathway engineering strategies [7] [9].

Metabolic Model Construction and Validation

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) constrained with enzyme kinetics (ecModels) narrow the solution space and improve prediction accuracy compared to classical stoichiometric models [9]. The workflow involves:

- Model reconstruction: Compiling reaction networks from genome annotation and biochemical databases.

- Integration of enzyme constraints: Incorporating kcat values from resources like AutoPACMEN to simulate proteome-limited growth [9].

- Experimental validation: Using ¹³C-metabolic flux analysis (MFA) to verify model predictions under different conditions [9].

Laboratory Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Establishing Genetic Transfer in Non-Model Bacteria

- Identify restriction-modification systems through genome analysis.

- Clone methyltransferase genes from target organism into E. coli cloning strain.

- Construct vectors using broad-host-range origins of replication (e.g., from Jain and Srivastava [11]).

- Test conjugation and transformation protocols with methylated DNA.

- Validate genetic access with reporter gene expression.

Protocol 2: CRISPR-Cas Genome Editing in Non-Model Hosts

- Select CRISPR system based on host compatibility (Cas9, Cas12a, or endogenous systems).

- Design guide RNAs targeting genomic regions of interest.

- Assemble editing construct with homologous repair templates if needed.

- Deliver editing components via conjugation or transformation.

- Screen and validate mutants by colony PCR and sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Engineering Non-Model Microbes

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors | RSF1010, RK2, pBBR1 origins | Plasmid maintenance across diverse species | Select based on host phylogeny and copy number requirements |

| CRISPR Systems | Cas9, Cas12a, endogenous Type I-F | Genome editing, gene regulation | Requires host-specific gRNA design and validation |

| DNA Delivery Tools | Electroporation, conjugation, methyltransferase co-expression | Introduction of foreign DNA | Methylation pattern matching critical for success |

| Reporter Systems | GFP, RFP, lux operon, gas vesicles | Promoter characterization, circuit performance | Codon-optimize for specific host; consider oxygen requirements |

| Metabolic Model Software | COBRA, ECMpy, AutoPACMEN | Predicting metabolic fluxes, identifying bottlenecks | Integrate with omics data for constrained modeling |

| Genome Reduction Tools | CRE-loxP, Red/ET recombination, MADS | Removing non-essential genes, mobile elements | Requires essentiality data; may require iterative approach |

| Peptaibolin | Peptaibolin, MF:C31H51N5O6, MW:589.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| THIP-d4 | THIP-d4, MF:C6H8N2O2, MW:144.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation Roadmap and Future Perspectives

The systematic development of non-model microbial chassis requires careful planning across multiple stages. Implementation should follow a structured approach that integrates technical and economic considerations from the outset.

Integrated Techno-Economic and Sustainability Analysis

Early-stage techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life cycle assessment (LCA) are crucial for guiding engineering efforts toward economically viable and sustainable processes [7]. These analyses should evaluate:

- Substrate selection and availability: Local accessibility reduces transportation carbon footprint [7].

- Product yield requirements: Determining the minimum yield for economic viability accelerates pathway design [7].

- Greenhouse gas emissions: Assessing the carbon footprint of the entire process from feedstock to product [9].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Automation and High-Throughput Screening: Robotic systems enable rapid testing of genetic parts, growth conditions, and enzyme variants in non-model hosts, accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle [12].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI tools predict gene essentiality, optimize metabolic fluxes, and design genetic parts, reducing the time and cost associated with chassis development [13] [10].

Cell-Free Biosynthesis Systems: These bypass cellular constraints and enable rapid prototyping of pathways before implementation in living hosts [13].

Non-model microorganisms represent the next frontier in synthetic biology, offering diverse metabolic capabilities and physiological traits that are difficult to engineer into conventional chassis. Their successful development requires a systematic approach to host selection, guided by metabolic, ecological, and genetic criteria. Advanced engineering strategies, including genome reduction, systems metabolic engineering, and custom tool development, can transform these underexplored microbes into efficient biorefinery chassis. By integrating techno-economic and sustainability analyses early in the development process, researchers can ensure that these innovative microbial platforms contribute meaningfully to a sustainable bioeconomy.

In synthetic biology, the selection of a microbial chassis is a foundational decision that directly influences the success and scalability of any engineering endeavor. The core of this selection process hinges on genetic tractability—the ease with which an organism's genetic material can be modified and controlled. Historically, the field has been biased toward a narrow set of well-characterized organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to their well-established genetic toolkits and known behaviors [3]. However, relying solely on these traditional hosts imposes significant design constraints, potentially overlooking non-model organisms that may offer superior capabilities for specific applications such as biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, or therapeutics [3]. The emerging discipline of broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology seeks to overcome this limitation by reconceptualizing the host chassis not as a passive platform, but as an integral, tunable design parameter [3]. This paradigm shift requires a robust foundation in genetic tool development to domesticate a wider range of microbes, thereby expanding the chassis-design space and unlocking new biotechnological potential.

Core Concepts: Defining Genetic Tractability and the "Chassis Effect"

The Pillars of Genetic Tractability

Genetic tractability is a multifaceted concept encompassing several key capabilities:

- Efficient Genetic Accessibility: The ability to introduce foreign DNA reliably through transformation or conjugation.

- Precise Genome Editing: The capacity to make targeted insertions, deletions, or replacements in the host genome with high efficiency and accuracy.

- Stable Gene Expression: The capability to maintain and express heterologous genes predictably over time without significant performance loss.

- Metabolic and Regulatory Compatibility: The innate cellular environment must support the function of introduced genetic circuits without excessive interference or burden.

The "Chassis Effect" and Host-Construct Interactions

A major challenge in cross-species engineering is the "chassis effect," where identical genetic constructs exhibit different behaviors depending on the host organism [3]. This context dependency arises from complex host-construct interactions, including:

- Resource Competition: Introduced genetic circuits compete with native cellular processes for finite resources such as RNA polymerase, ribosomes, and metabolites [3].

- Regulatory Crosstalk: Differences in transcription factor structure, abundance, and promoter–sigma factor interactions can significantly modulate gene expression profiles across hosts [3].

- Metabolic Burden: The expression of exogenous genes perturbs the host's metabolic state, potentially triggering stress responses or reducing growth rates [3]. These interactions can lead to unpredictable circuit performance, making the understanding and characterization of the chassis effect a prerequisite for reliable biological design.

Quantitative Comparison of Genetic Toolkits Across Microbial Chassis

The development of standardized genetic tools varies significantly across different host organisms. The following table summarizes key tractability metrics and tool availability for prominent microbial chassis, highlighting the current disparity between traditional and non-model organisms.

Table 1: Comparison of Genetic Tractability and Tool Development in Selected Microbial Chassis

| Chassis Organism | Editing Efficiency (%) | Key Genetic Tools | HR Efficiency | Multi-Copy Integration | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | High (Well-established) | CRISPR-Cas9, SEVA vectors, Lambda Red | High | Yes (Plasmids) | Metabolic engineering, protein production [3] [2] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | High (Well-established) | CRISPR-Cas9, Golden Gate assembly | High | Yes (rDNA, delta sites) | Biosynthetic pathways, eukaryotic protein expression [3] [2] |

| Hansenula polymorpha DL-1 | 97.2 (with optimized CRISPR-Cas9) [14] | CRISPR-Cas9, KU80 knockout, rDNA/Ty element targeting | 88.9% (with NHEJ suppression) [14] | Yes (rDNA, Ty elements) [14] | Thermotolerant biomanufacturing, β-carotene (60-fold increase) and squalene (187.2 mg/L) production [14] |

| Halomonas bluephagenesis | Moderate (Emerging) | BHR vectors, metabolic engineering | Moderate | Under development | High-salinity fermentations, natural product accumulation [3] |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (e.g., Lactococcus lactis) | Moderate (Varies by species) | CRISPR-Cas, conjugation | Moderate to Low | Limited | Probiotics, therapeutic delivery (e.g., ADH1B for alcohol metabolism) [15] |

| Cyanobacteria | Moderate (Emerging) | BHR vectors, photosynthetic circuit design | Moderate | Under development | Solar-driven biosynthesis, CO2 utilization [3] [2] |

| Mmp2-IN-4 | Mmp2-IN-4, MF:C19H22N2O5S, MW:390.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | ||

| MTDH-SND1 blocker 2 | MTDH-SND1 blocker 2, MF:C18H12FN3O2S, MW:353.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes from Advanced Tool Deployment in Non-Model Chassis

| Chassis Organism | Genetic Intervention | Experimental Outcome | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hansenula polymorpha DL-1 | KU80 knockout + ScHR genes overexpression [14] | HR rate increased to 88.9% [14] | Overcame strong native NHEJ for precise editing |

| Hansenula polymorpha DL-1 | Multi-copy integration via rDNA and Ty elements [14] | β-carotene production increased ~60-fold; squalene titers reached 187.2 mg/L [14] | Enabled high-yield metabolic engineering |

| Saccharomyces boulardii | CRISPR-based engineering for β-carotene biosynthesis [15] | Localized, sustained micronutrient production in mouse intestines [15] | Demonstrated in vivo functionality of engineered probiotics |

| Lactococcus lactis | Expression of human ADH1B enzyme [15] | Reduced blood acetaldehyde and liver damage in alcohol-exposed models [15] | Engineered therapeutic bacteria for metabolic disorders |

Essential Toolkit: Research Reagents and Solutions for Genetic Engineering

The following reagents and tools constitute the core toolkit for developing genetic tractability in microbial chassis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Tool Development

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-Cas12a, ZFN, TALEN [15] | Create targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) for precise genome modifications. CRISPR-Cas is preferred for efficiency and flexibility [15]. |

| DNA Delivery Methods | Conjugative transfer, electroporation, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (plants) [15] [16] | Introduce foreign DNA into host cells. Conjugation is particularly valuable for non-transformable species [15]. |

| Vector Systems | SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture), BAC (Bacterial Artificial Chromosome) [3] [15] | Maintain and replicate genetic constructs. BHR vectors like SEVA facilitate tool transfer across species [3]. |

| Reporter and Selection Systems | Antibiotic resistance genes, fluorescent proteins, auxotrophic markers | Enable selection of successfully modified cells and visualization of gene expression in real-time. |

| Host Engineering Tools | NHEJ pathway knockout (e.g., KU80), overexpression of HR genes (e.g., from S. cerevisiae) [14] | Modify host genetics to enhance editing efficiency, such as increasing homologous recombination rates [14]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | gRNA design software, genome annotation platforms, pathway modeling tools | Facilitate in silico design of editing constructs and prediction of system behavior. |

| Ebselen derivative 1 | Ebselen derivative 1, MF:C13H10N2O2Se, MW:305.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Griseolutein B | Griseolutein B, CAS:11029-63-3, MF:C17H16N2O6, MW:344.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Key Tool Development Methodologies

Protocol: Developing a High-Efficiency CRISPR-Cas9 System in a Non-Model Yeast

This protocol is adapted from the successful engineering of Hansenula polymorpha DL-1 [14].

Objective: To achieve precise genome editing in a thermotolerant yeast with a strong non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway.

Materials:

- H. polymorpha DL-1 wild-type strain

- CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid optimized for the target host (includes codon-optimized Cas9, gRNA expression cassette, and selectable marker)

- Donor DNA template for homologous recombination (HR)

- Equipment for yeast transformation (e.g., electroporator)

- Ku80 knockout cassette

Methodology:

- Suppress NHEJ Pathway: Disrupt the KU80 gene, a key component of the NHEJ machinery, to reduce error-prone repair. Transform the KU80 knockout cassette into the wild-type strain and select for successful integrants [14].

- Enhance HR Efficiency: Further increase HR rates by overexpressing homologous recombination-related genes from S. cerevisiae (e.g., RAD51, RAD52) in the KU80 knockout strain [14].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery: Introduce the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid, which is programmed with a gRNA targeting the specific genomic locus of interest, into the engineered host [14].

- Co-deliver Donor DNA: Provide a donor DNA template containing the desired modification (e.g., gene insertion, point mutation) flanked by homology arms (typically 500-1000 bp) to the target locus.

- Selection and Screening: Select for transformants using the plasmid's selectable marker. Screen colonies via PCR and sequencing to verify precise genome edits. The reported editing efficiency for this approach in H. polymorpha is 97.2% [14].

Protocol: Establishing Multi-Copy Integration for Pathway Amplification

Objective: To integrate multiple copies of a biosynthetic gene cluster into the host genome to amplify product titers, as demonstrated with β-carotene and squalene production [14].

Materials:

- Engineered host strain with high HR efficiency (from Protocol 5.1)

- Multi-copy integration vector targeting genomic repetitive elements (e.g., rDNA loci, Ty retrotransposons)

- Donor DNA containing the pathway genes flanked by sequences homologous to the target repetitive element

Methodology:

- Identify Neutral Sites: Select genomic loci that can tolerate multiple integrations without disrupting native gene function or causing metabolic burden. In H. polymorpha, rDNA clusters and Ty elements have been successfully used [14].

- Construct Integration Vector: Design a donor construct containing the biosynthetic pathway genes and a selectable marker, flanked by homology arms specific to the chosen neutral site.

- Sequential Transformation: Introduce the integration construct into the engineered host. Utilize increasing antibiotic selection pressure or screening for high-expression clones to isolate strains with multiple integrations.

- Titer Verification: Quantify the final product titer (e.g., via HPLC or GC-MS) and genotype the strains to correlate copy number with yield. This approach has led to a ~60-fold increase in β-carotene production in H. polymorpha [14].

Visualization of Workflows and System Relationships

Workflow for Developing Genetic Tractability in a Non-Model Organism

The "Chassis Effect" on Genetic Circuit Performance

CRISPR-Cas Mediated Genome Editing Workflow

Genetic tractability is not merely a convenience but a fundamental engineering parameter that must be systematically evaluated when selecting a microbial chassis. The development of sophisticated tools like CRISPR-Cas systems, combined with host engineering to manipulate DNA repair pathways, has dramatically expanded the range of organisms accessible for synthetic biology applications [14]. As the field progresses toward broad-host-range synthetic biology, the strategic selection and engineering of chassis based on their native capabilities and genetic accessibility will be crucial for unlocking novel biotechnological applications [3]. Future advancements will likely focus on standardizing toolkits for cross-species compatibility, developing machine learning approaches to predict host-construct interactions, and creating engineered kill switches for biocontainment [15]. By treating the chassis as an active, tunable component rather than a passive vessel, synthetic biologists can harness the full potential of microbial diversity for sustainable biomanufacturing, therapeutic development, and environmental solutions.

Metabolic Network Analysis and Pathway Compatibility Considerations

Selecting an optimal microbial chassis constitutes a critical foundational step in synthetic biology projects, influencing the success of bioproduction, biosensing, and therapeutic applications. This selection process requires a systematic evaluation of an organism's metabolic network to ensure compatibility with the desired pathway and functionality within the target environment. Metabolic network analysis provides the computational framework to quantitatively assess this compatibility, moving beyond trial-and-error approaches to a predictive, engineering-based paradigm. By analyzing pathway structure, flux capacities, and network integration, researchers can identify potential bottlenecks, thermodynamic constraints, and regulatory conflicts before embarking on costly experimental work. This technical guide outlines the core principles, methodologies, and tools for conducting metabolic network analysis specifically within the context of microbial chassis selection for synthetic biology research, providing a structured approach for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Principles of Metabolic Network Analysis

Metabolic networks represent the complete set of metabolic reactions and compounds within a cell, forming a complex biochemical system. Analysis of these networks relies on several foundational principles that enable quantitative assessment of pathway compatibility.

Network Structure and Topology

The topological structure of metabolic networks reveals functional relationships between metabolic components. Analysis begins with constructing a reaction graph where nodes represent biochemical reactions and edges represent metabolite flow between them [17]. In this model, an edge exists from reaction Ri to Rj if at least one metabolite produced by Ri is consumed by Rj [17]. This representation allows researchers to identify connectivity patterns, pathway modules, and potential choke points. For directed analysis, reversible reactions are represented as separate nodes for forward and reverse directions to prevent algorithms from establishing biochemically invalid paths [18].

A key advancement in analyzing complex networks is the transformation of the reaction graph into a metabolic directed acyclic graph (m-DAG). This is achieved by collapsing strongly connected components into single nodes called metabolic building blocks (MBBs), significantly reducing node count while maintaining network connectivity [17]. This simplification enables researchers to more easily interpret the topological organization of metabolic networks and identify core metabolic processes.

Metabolic Pathway Relationships

Integrated analysis of multi-omics datasets covering different levels of molecular organization provides insights into dynamic pathway relationships. Research on yeast stress response has demonstrated that pairwise metabolite correlation levels carry more pathway-related information and extend to farther distances within metabolic pathway networks than associated transcript level correlations [19]. This correlation structure reflects functional relationships, with metabolites detected to correlate more strongly to their cognate transcripts than to remote or randomly chosen transcripts [19].

Temporal hierarchy represents another crucial consideration in metabolic analysis. Under stress conditions, changes in metabolite levels generally precede changes in transcript levels of enzymes linked to the corresponding metabolites via substrate or product relationships [19]. The application of Granger causality analysis to time-series data can reveal directed relationships between metabolites and their cognate transcripts, with most directed pairs agreeing with KEGG-annotated preferred reaction direction when interpreted as substrate-to-product directions [19].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Metabolic Network Topology Analysis

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Interpretation in Chassis Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | Node Degree | Identifies highly connected metabolites (hubs) that may represent thermodynamic bottlenecks |

| Path Analysis | Shortest Path Length | Reveals minimal reaction steps between metabolites; shorter paths often indicate more efficient conversions |

| Centrality | Betweenness Centrality | Highlights metabolites or reactions that control flow through multiple pathways |

| Cluster Analysis | Strongly Connected Components | Identifies functional modules that operate semi-independently (MBBs) |

| Integration | Clustering Coefficient | Quantifies how neighbors of a node connect to each other, indicating network resilience |

Methodological Framework for Analysis

Metabolic Network Reconstruction

The initial step in metabolic network analysis involves reconstructing a comprehensive biochemical network for the potential chassis organism. This process typically begins by retrieving organism-specific metabolic information from curated databases such as KEGG [17], MetaCyc [18], or BioCyc [17]. These databases provide standardized nomenclature and annotations for genes, proteins, enzymes, and pathways, enabling consistent reconstruction across different organisms.

Tools like MetaDAG automate metabolic network reconstruction using various inputs, including single organisms, groups of organisms, specific reactions, enzymes, or KEGG Orthology (KO) identifiers [17]. The reconstruction process generates two computational models: a reaction graph that represents reactions as nodes and metabolite flow as edges, and an m-DAG that collapses strongly connected components to simplify analysis while maintaining connectivity [17]. This flexibility supports reconstruction across diverse sample types, from individual microbial samples to complex metagenomic communities.

For non-model organisms with limited database coverage, genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) can be constructed through genomic annotation followed by metabolic pathway mapping. This approach employs constraint-based modeling to map metabolic pathways and predict phenotypic behavior [20]. The resulting models provide insights into metabolic capabilities, resource allocation, and adaptation to changing conditions [20].

Pathway Compatibility Assessment

Once reconstructed, metabolic networks must be analyzed for compatibility with heterologous pathways. Subgraph extraction techniques provide powerful approaches for predicting pathway integration within existing metabolic networks. These methods extract relevant sub-networks connecting a set of query items (e.g., genes, proteins, compounds) defining seed nodes in the network [18].

Several algorithms have been developed for this purpose, with hybrid strategies combining random walk-based graph reduction with shortest paths-based algorithms demonstrating particularly high accuracy (∼77%) in recovering known metabolic pathways [18]. Weighting policies represent a critical consideration in these analyses, as metabolic networks contain ubiquitous hub compounds (e.g., H2O, NADP, ATP) that can distort pathway prediction if not properly accounted for. Penalizing highly connected compounds by assigning weights equal to their degree (or the square of their degree) prevents algorithms from preferentially crossing these hubs and generating biochemically invalid paths [18].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Network Analysis

| Protocol | Key Steps | Applications in Chassis Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Series Metabolite-Transcript Correlation | 1. Collect time-course transcriptomics and metabolomics data under perturbation2. Calculate pairwise correlation coefficients3. Apply Granger causality analysis4. Map correlations to KEGG pathways | Identify rate-limiting steps and regulatory hierarchies; validate substrate-to-product directions [19] |

| Subgraph Extraction for Pathway Prediction | 1. Define seed nodes from heterologous pathway2. Apply weighting policy to avoid hub compounds3. Execute hybrid random walk/shortest path algorithm4. Validate extracted sub-network against reference pathways | Predict integration points and potential bottlenecks for heterologous pathways [18] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling (GEM) | 1. Reconstruct organism-specific metabolic network from KEGG/MetaCyc2. Apply constraints-based modeling3. Simulate growth with heterologous pathway4. Perform flux balance analysis | Predict metabolic capabilities and identify necessary gene deletions/additions [20] |

| Visualization of Network Dynamics | 1. Map quantitative data to network layout2. Implement fill-level representation for metabolites3. Create smooth interpolation between time points4. Generate animation of metabolic changes | Communicate dynamic system behavior and identify transient metabolic states [21] |

Visualization of Metabolic Dynamics

Effective visualization represents an essential component of metabolic network analysis, particularly for time-course data that captures system dynamics. The GEM-Vis method enables visualization of longitudinal metabolomic data within the context of metabolic network maps through animated sequences of dynamically changing networks [21]. This technique employs fill-level representation of metabolite nodes, allowing human beholders to estimate quantities most precisely based on perceptual research [21].

Implementation involves mapping time-series data to a manually drawn or algorithmically generated metabolic network layout, with smooth interpolation between time points creating seamless animation [21]. This approach facilitates the identification of transient metabolic states and system responses to perturbations that might be missed in static analyses. For chassis selection, such visualizations can reveal how endogenous metabolic states fluctuate and how these fluctuations might impact heterologous pathway function.

Computational Tools and Implementation

Software Platforms for Analysis

Several computational platforms specialize in different aspects of metabolic network analysis, each offering unique capabilities for chassis evaluation:

MetaDAG is a web-based tool that automates metabolic network reconstruction and analysis using KEGG database information [17]. It generates both reaction graphs and metabolic DAGs (m-DAGs) through an intuitive web interface, enabling researchers to visualize complex metabolic interactions efficiently. The tool can reconstruct networks from diverse inputs including specific organisms, groups of organisms, reactions, enzymes, or KO identifiers, making it applicable to both model and non-model organisms [17].

MetaboAnalyst provides a comprehensive web-based platform for metabolomics data analysis, interpretation, and integration with other omics data [22]. Its functionality includes pathway enrichment analysis, which supports over 120 species, and joint pathway analysis that enables simultaneous upload of both gene and metabolite lists for approximately 25 common model organisms [22]. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for assessing how heterologous pathways might interact with the host's native metabolic and regulatory networks.

GEM-Vis, implemented within the SBMLsimulator software, provides specialized visualization capabilities for time-course metabolomic data [21]. The method creates animated videos that display quantitative changes in metabolite levels directly on metabolic network maps, using fill-level, color, or size representations to indicate concentration changes [21]. This dynamic visualization supports hypothesis generation about metabolic state changes during chassis cultivation.

Workflow for Chassis Evaluation

A systematic workflow for evaluating microbial chassis through metabolic network analysis involves multiple stages:

Network Reconstruction: Retrieve organism-specific metabolic information from KEGG or MetaCyc databases and reconstruct the metabolic network using tools like MetaDAG [17].

Topological Analysis: Calculate key network metrics including connectivity, path lengths, and centrality measures to identify critical nodes and potential bottlenecks [18].

Heterologous Pathway Integration: Map the desired heterologous pathway onto the host network using subgraph extraction algorithms, identifying potential integration points and competing reactions [18].

Constraint-Based Modeling: Implement genome-scale metabolic modeling to simulate pathway flux under different nutrient conditions and identify necessary genetic modifications [20].

Dynamic Analysis: If time-series data are available, perform metabolite-transcript correlation analysis and create dynamic visualizations to understand temporal metabolic hierarchies [19] [21].

This structured approach enables comprehensive assessment of pathway compatibility before experimental implementation, significantly de-risking the chassis selection process.

Case Studies and Applications

Evaluation of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Therapeutic Chassis

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) represent promising chassis organisms for therapeutic applications due to their safety profile and industrial relevance. Systematic metabolic network analysis of Lactococcus lactis has demonstrated its potential as a delivery vehicle for vaccines and therapeutic proteins [20]. Genome-scale metabolic modeling of LAB chassis reveals their metabolic capabilities, including vitamin production (folate and riboflavin), biofuel synthesis (ethanol), and therapeutic molecule expression [20].

Metabolic analysis further identifies opportunities for genome reduction in LAB strains without compromising essential functions. Studies have demonstrated that a 6.9% reduction of the L. lactis genome through deletion of prophages and genomic islands resulted in a 17% shortening of generation time, indicating reduced metabolic burden and improved efficiency [20]. Such improvements are particularly valuable for industrial-scale applications where growth rate impacts production throughput.

Environmental Biosensor Chassis Selection

Environmental biosensing presents unique challenges for chassis selection, requiring organisms that persist under specific environmental conditions while maintaining circuit functionality. A conceptual framework for biosensor chassis selection emphasizes four key constraints: safety (elimination of pathogens), ecological persistence (survival in target environment), metabolic persistence (compatibility with environmental conditions), and genetic tractability (engineering capability) [11].

Metabolic network analysis directly addresses the metabolic persistence constraint by evaluating whether an organism's primary metabolism aligns with environmental conditions. For example, obligate aerobes may not persist in soils or sediments with oxygen gradients, making metabolic network analysis essential for identifying suitable chassis [11]. Genome-scale metabolic modeling (GEMs) offers a method to interrogate an organism's metabolic potential and predict cellular growth on diverse substrates relevant to the target environment [11].

Integration with Synthetic Biology Workflow

Metabolic network analysis should be integrated early in the synthetic biology Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle to inform chassis selection and pathway design. The model-guided approach utilizes metabolic models and minimal genome concepts to develop microbial chassis with optimized performance [20]. This integration enables predictive design of chassis organisms tailored to specific applications, whether for bioproduction, biosensing, or therapeutic delivery.

Future directions in the field point toward increased automation in metabolic network reconstruction, more sophisticated dynamic modeling approaches, and enhanced visualization tools that integrate multiple omics data types. As synthetic biology applications expand to non-model organisms, these computational approaches will become increasingly essential for rational chassis selection and engineering.

Diagram 1: Metabolic Network Analysis Workflow for Chassis Selection. This diagram outlines the systematic process for evaluating microbial chassis through metabolic network analysis, beginning with input criteria and progressing through reconstruction, topological analysis, pathway compatibility assessment, and dynamic evaluation to generate chassis scores and modification recommendations.

Diagram 2: Pathway Integration and Compatibility Analysis. This diagram illustrates the critical considerations when integrating heterologous pathways (red) into host metabolic networks (blue), highlighting precursor supply, byproduct formation, and competing flux demands that must be analyzed for successful chassis engineering.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Network Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function in Analysis | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | KEGG Database | Provides curated metabolic pathway information for network reconstruction | Standardized nomenclature enables consistent cross-species comparisons [17] |

| MetaCyc/BioCyc | Offers experimentally validated metabolic pathways for reference validation | Tiered curation system ensures data quality for critical pathways [18] | |

| Software Tools | MetaDAG | Automated reconstruction of reaction graphs and metabolic DAGs from KEGG | Web-based interface enables accessibility without local installation [17] |

| MetaboAnalyst | Statistical and functional analysis of metabolomics data with pathway integration | Supports joint pathway analysis of genes and metabolites [22] | |

| SBMLsimulator with GEM-Vis | Visualization of time-course metabolomic data on network maps | Creates animated videos for dynamic data representation [21] | |

| Analytical Algorithms | Subgraph Extraction | Predicts pathway integration points and potential bottlenecks | Hybrid random walk/shortest path algorithm shows highest accuracy [18] |

| Granger Causality | Identifies directed relationships in metabolite-transcript time-series data | Reveals temporal hierarchies in metabolic regulation [19] | |

| Flux Balance Analysis | Constraint-based modeling of metabolic fluxes through networks | Predicts phenotypic behavior under different conditions [20] |

Within synthetic biology, the concept of a microbial chassis—a host cell engineered to carry out specific synthetic functions—is fundamental [1]. Selecting an appropriate chassis is a critical design decision that significantly influences the success and safety of any bioengineering project [4]. For applications in biomedicine and food, the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status is a pivotal regulatory designation. A GRAS certification indicates that a microorganism is safe for its intended use, based on expert consensus and a history of safe use, and is not a pathogen [11] [23]. This status is not merely a safety checkbox but a foundational engineering parameter that enables the transition of laboratory research into clinically and commercially viable products. Yarrowia lipolytica is one such industrial microbial chassis that has gained prominence due to its robust metabolic capabilities combined with its GRAS status [24]. This guide details the criteria, methodologies, and compliance frameworks for selecting and engineering GRAS-certified microbial chassis for biomedical applications, positioning safety and regulatory adherence as core components of the synthetic biology design cycle.

Regulatory Framework and Key Criteria for GRAS Designation

Foundational Principles and Safety Constraints

The regulatory framework for deploying engineered microbes, especially in medical contexts, is built on a precautionary principle, often summarized as "do no harm" [11]. This foremost constraint eliminates known pathogens from consideration as chassis organisms. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) provides a quantitative benchmark for biocontainment, recommending an escape frequency of no more than 1 in 10^8 cells to prevent uncontrolled proliferation in the environment [11]. To meet this stringent requirement, multiple redundant biocontainment strategies are often employed. These can include:

- Toxin-antitoxin systems

- Auxotrophy for essential metabolites not available in the environment

- Inducible kill switches

- Xenobiology using non-natural nucleotides and amino acids to create genetic firewalls [11]

Beyond these engineered safeguards, a GRAS designation relies on a proven historical record of safe use in processes like food fermentation and an absence of pathogenic traits [23].

Quantitative and Phenotypic Criteria for Chassis Selection

When evaluating a potential microbial chassis for biomedical applications, researchers must assess a suite of quantitative and phenotypic criteria. These criteria ensure the organism is not only safe but also practically suited for industrial-scale bioprocessing and therapeutic production.

Table 1: Key Quantitative and Phenotypic Criteria for GRAS Chassis Selection

| Criterion | Description | Importance in Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Tractability | Availability of tools for transformation, genome editing, and gene expression control [1]. | Enables precise engineering of therapeutic pathways (e.g., insulin, antibodies) and biosafety features. |

| Growth Characteristics | Fast growth rate, simple nutrient requirements, and high stress tolerance [1]. | Reduces production costs, simplifies fermentation media, and ensures process robustness at scale. |

| Metabolic Compatibility | Native metabolic pathways that support or do not interfere with the target synthetic pathway [1]. | Increases yield of target biomolecule (e.g., vaccines, enzymes) and minimizes metabolic burden. |

| Secretory Capacity | Ability to efficiently secrete proteins into the extracellular environment [24]. | Simplifies downstream purification of protein-based therapeutics, reducing manufacturing costs. |

| Historical Safety Data | A long history of safe use in food or industrial processes, with a fully sequenced and annotated genome [11] [23]. | Provides a strong foundation for regulatory approval and reduces the burden of safety testing. |

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Safety and Compliance

A rigorous experimental workflow is essential to characterize a potential chassis and establish its safety and functionality for biomedical use. The following protocol outlines the key stages.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for chassis safety and functional characterization.

Phase 1: Genomic Characterization

Objective: To obtain a complete and annotated genome sequence for the chassis candidate, identifying all potential virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes, and metabolic pathways.

- Methodology:

- Isolate high-quality genomic DNA.

- Perform whole-genome sequencing using a combination of short-read (e.g., Illumina) and long-read (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) technologies to achieve a complete, closed genome [23].

- Annotate the genome using automated pipelines (e.g., RAST, Prokka) and curated databases (e.g., NCBI, UniProt) to identify protein-coding genes, RNAs, and genomic islands.

- Systematically screen the annotated genome against databases of known virulence factors (e.g., VFDB) and antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., CARD).

Phase 2: Pathogenicity and Toxicity Screening

Objective: To empirically confirm the non-pathogenic nature of the chassis and ensure it does not produce toxins.

- Methodology:

- Conduct in vitro cytotoxicity assays using mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK-293, HepG2). Expose cells to lysates and culture supernatants of the chassis and measure cell viability via MTT or WST-1 assays.

- Perform hemolysis assays on red blood cells to detect pore-forming toxins.

- Utilize established in vivo models, such as Galleria mellonella (wax moth larvae), to assess acute toxicity. Inject a standardized dose of the chassis and monitor for survival and signs of disease over 72-96 hours.

Phase 3: Genetic Tool Development

Objective: To establish robust protocols for DNA delivery and genome editing, which are prerequisites for all subsequent engineering.

- Methodology:

- Transformation: Test various DNA delivery methods, including electroporation, chemical transformation, and conjugation, to achieve efficient plasmid introduction [11] [23].

- Genome Editing: Implement a CRISPR-Cas9 system tailored for the chassis. As demonstrated in Y. lipolytica, this involves codon-optimizing the Cas9 gene, driving its expression with a strong promoter (e.g., PTEF), and optimizing sgRNA expression using RNA polymerase III promoters or ribozyme-flanked cassettes [24]. Evaluate editing efficiency by targeting a non-essential gene and screening for knockouts.

Engineering GRAS Chassis for Enhanced Safety and Biomedical Function

Advanced Biocontainment Circuits and Biosensors

For biomedical applications, basic auxotrophies may be insufficient. Advanced orthogonal biocontainment systems must be engineered to ensure the chassis cannot survive outside the controlled production environment. A multi-layered approach is recommended:

- Kill Switches: These are genetic circuits that induce cell death upon detection of an environmental change. For example, a circuit could be designed to express a potent toxin in the absence of a chemical inducer that is exclusively present in the fermentation vessel.

- Auxotrophic Coupling: Engineered auxotrophies for essential nutrients (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides) that are not available in natural environments prevent growth outside the lab [11].

- Metabolic Addiction: The chassis is engineered to rely on a synthetic, non-natural metabolite for the regulation of a critical gene. Without the metabolite, a repressor protein is activated, halting growth [11].

Furthermore, engineered biosensors are crucial for dynamic pathway control and product monitoring. For instance, a xylose-inducible biosensor integrating the E. coli XylR activator has been used in Y. lipolytica to dynamically regulate metabolic flux [24]. Similarly, light-controlled systems (e.g., using CarH or EL222 proteins) offer non-chemical, tunable induction for producing compounds like coumaric acid and naringenin [24].

Pathway Engineering and Host-Context Optimization

A key principle in broad-host-range synthetic biology is to treat the chassis not as a passive platform but as a tunable component of the overall system [3]. This is critical for managing the "chassis effect," where the same genetic construct behaves differently in various hosts due to differences in resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [3].

- Promoter Engineering: To achieve precise expression levels, synthetic promoters can be designed. In Y. lipolytica, hybrid promoters created by modular recombination of a core promoter with tandem upstream activating sequences (UAS) have achieved dynamic ranges exceeding 400-fold [24].

- Orthogonality: Using prokaryotic transcription factors in yeast chassis can create regulatory systems that are decoupled from the host's native networks, reducing metabolic burden and improving stability. The FdeR-FdeO system in Y. lipolytica achieved stable naringenin-sensitive regulation over 324 generations [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for GRAS Chassis Engineering

The following table details key reagents and tools required for the genetic domestication and engineering of a novel GRAS chassis.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Chassis Engineering

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Assembly Systems | Golden Gate Assembly, SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture) plasmids [3] | Standardized, modular assembly of multi-part genetic circuits and pathways. |

| Genome Editing Tools | Codon-optimized CRISPR-Cas9 systems; sgRNA expression constructs with ribozyme flanking sequences (e.g., hammerhead, HDV) [24] | High-efficiency, targeted gene knockouts, integrations, and multiplexed editing. |

| Broad-Host-Range Parts | Constitutive promoters (PTEF, PGPD); Inducible promoters (PXPR2, PICL1); Orthogonal transcription factors (FdeR, XylR) [24] [3] | Reliable gene expression control across diverse microbial hosts, minimizing context-dependency. |

| Biocontainment Modules | Engineered toxin-antitoxin pairs; Arabinose- or tetracycline-dependent kill switches; Xenonucleic acid (XNA) synthetases [11] | Ensures biological safety and environmental containment of the engineered chassis. |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, mCherry); Luciferase enzymes; Gas vesicles [24] [11] | Quantitative characterization of part performance, circuit activity, and chassis persistence. |

| Cyclothiazomycin | Cyclothiazomycin, MF:C59H64N18O14S7, MW:1473.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Periglaucine A | Periglaucine A, MF:C20H23NO6, MW:373.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of GRAS status and rigorous safety engineering into the synthetic biology design cycle is non-negotiable for the successful development of biomedical products. The process extends from a thorough initial screening of chassis candidates against genomic and phenotypic criteria to the implementation of sophisticated, multi-layered biocontainment systems. By adopting a holistic view where the chassis is an active, tunable component, and by leveraging a growing toolkit of standardized genetic parts and editing technologies, researchers can harness the unique capabilities of non-model GRAS organisms. This approach promises to unlock new possibilities in sustainable and safe biomanufacturing of next-generation therapeutics, while robustly addressing the regulatory and safety imperatives of the biomedical field.

The selection of microbial chassis is a cornerstone of synthetic biology, dictating the efficiency, scalability, and ultimate success of biomanufacturing processes. While genetic tractability is often prioritized, the inherent physiological attributes of a host—specifically its metabolic capabilities under varying oxygen conditions and energy sources—are critical, yet sometimes undervalued, determinants of its industrial potential [25]. These attributes define the host's "lifestyle," influencing the thermodynamic feasibility of metabolic pathways, the cost and complexity of bioreactor operation, and the compatibility with desired feedstocks [26] [7].

Understanding these capabilities is not merely descriptive; it provides a rational framework for matching a microbial host to a bioprocess. For instance, anaerobic or micro-aerobic fermentations can significantly reduce energy costs by eliminating the need for vigorous aeration and agitation, while phototrophic hosts offer the potential to utilize light as a sustainable energy source [7]. This guide details the core physiological categories—aerobic, anaerobic, and phototrophic capabilities—and provides the experimental and computational methodologies necessary for their characterization and deployment in synthetic biology research. Integrating this physiological understanding at the outset of project design is essential for engineering robust and economically viable cell factories [7] [25].

Core Physiological Capabilities of Microbial Chassis

Aerobic Metabolism