The EMU Framework: Revolutionizing Isotopic Analysis for Metabolic Flux and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework, a powerful computational methodology that has transformed 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA).

The EMU Framework: Revolutionizing Isotopic Analysis for Metabolic Flux and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework, a powerful computational methodology that has transformed 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of EMU, which dramatically reduces the computational complexity of modeling isotopic labeling in metabolic networks. The scope extends from core concepts and decomposition algorithms to advanced methodological applications, software tools, and optimization strategies for designing effective tracer studies. A comparative analysis validates the EMU framework against traditional methods, highlighting its superior efficiency and pivotal role in elucidating cellular physiology for metabolic engineering and disease research.

What is the EMU Framework? Unpacking the Core Concepts and Computational Advantages

Defining Elementary Metabolite Units (EMUs) as Distinct Subsets of Metabolite Atoms

Elementary Metabolite Units (EMUs) provide a foundational framework for modeling isotopic distributions in metabolic networks, enabling efficient computational analysis of metabolic fluxes. Unlike traditional isotopomer methods that track entire labeled molecules, the EMU approach identifies the minimal subsets of atoms within metabolites that are necessary to simulate measurable isotopic labeling patterns. This decomposition strategy dramatically reduces the number of equations and computational resources required for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA), particularly when using multiple isotopic tracers. This Application Note defines the EMU formalism, quantifies its computational advantages, and provides detailed protocols for implementing EMU-based metabolic modeling in research settings.

Conceptual Definition and Formal Basis

An Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) is formally defined as any distinct subset of atoms within a metabolite [1] [2]. This framework represents a bottom-up modeling approach that decomposes metabolites into functional atomic subgroups, focusing computational resources only on the atoms relevant to predicting experimental measurements.

- Size Specification: The EMU size corresponds to the number of atoms comprising the subunit. For a metabolite with N atoms, there are 2^N -1 possible EMUs [1].

- Notation System: EMUs are denoted using subscripts that identify the specific atoms included. For example, for a metabolite A with three atoms, the possible EMUs include three size-1 EMUs (Aâ‚, Aâ‚‚, A₃), three size-2 EMUs (Aâ‚â‚‚, Aâ‚₃, A₂₃), and one size-3 EMU (Aâ‚₂₃) [1].

- Structural Consideration: Atoms within an EMU are not necessarily connected by chemical bonds, allowing the framework to represent diverse molecular arrangements [1].

The Need for EMU Framework in Metabolic Flux Analysis

Traditional Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) methods face significant computational limitations when dealing with complex networks or multiple isotopic tracers:

- Isotopomer Explosion: For a metabolite with N atoms having two possible labeling states (e.g., ¹²C vs. ¹³C), there are 2^N possible isotopomers [1]. This number becomes prohibitive with multiple tracers.

- Glucose Example: Glucose (C₆Hâ‚â‚‚O₆) presents 64 carbon isotopomers, 4,096 hydrogen isotopomers, and 2.6×10âµ combined carbon-hydrogen isotopomers [1]. When oxygen tracers (¹â¶O, ¹â·O, ¹â¸O) are included, this expands to 1.9×10⸠possible isotopomers [1] [2].

- Cumomer Limitation: The cumomer method, while efficient for some applications, maintains a one-to-one relationship with isotopomers and thus does not solve the scalability problem [1].

The EMU framework addresses these limitations by identifying the minimum information required to simulate isotopic labeling, dramatically reducing model complexity without sacrificing accuracy [1] [2].

Quantitative Advantages of the EMU Framework

Computational Efficiency Gains

The EMU framework provides substantial performance improvements over traditional isotopomer and cumomer methods:

Table 1: Computational Efficiency Comparison Between Modeling Frameworks

| Modeling Framework | Number of Variables for Gluconeogenesis Pathway | Computational Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopomer/Cumomer | >2,000,000 variables [1] [2] | High memory and processing time |

| EMU Framework | 354 EMUs [1] [2] | Reduced by approximately one order of magnitude |

| E. coli Model | 238 reactions [3] | 10-fold decrease in variables with EMU and flux coupling |

For a typical ¹³C-labeling system, the EMU framework reduces the number of equations by one order of magnitude (100s of EMUs vs. 1000s of isotopomers) [1]. This efficiency enables previously infeasible studies with multiple isotopic tracers (²H, ¹³C, and ¹â¸O) that would require millions of variables under traditional approaches [2].

Application Scope and Impact

Table 2: EMU Framework Applications and Performance

| Application Domain | EMU Implementation | Impact and Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Gluconeogenesis Pathway | 354 EMUs vs. >2×10ⶠisotopomers [1] | Enabled multiple tracer analysis |

| E. coli Metabolic Model | EMU with flux coupling [3] | 10-fold decrease in variables; 2% of original computation time for flux specification |

| TCA Cycle Modeling | Adjacency matrix approach [4] | Intuitive decomposition and efficient simulation |

| Tracer Selection | EMU basis vector methodology [5] [6] | Rational design of isotopic tracers for improved flux observability |

The implementation of EMU modeling in software tools such as EMUlator demonstrates how the adjacency matrix method provides an intuitive approach to EMU decomposition, making the technique more accessible to researchers [4].

Experimental Protocol: EMU-Based Metabolic Modeling

Workflow for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

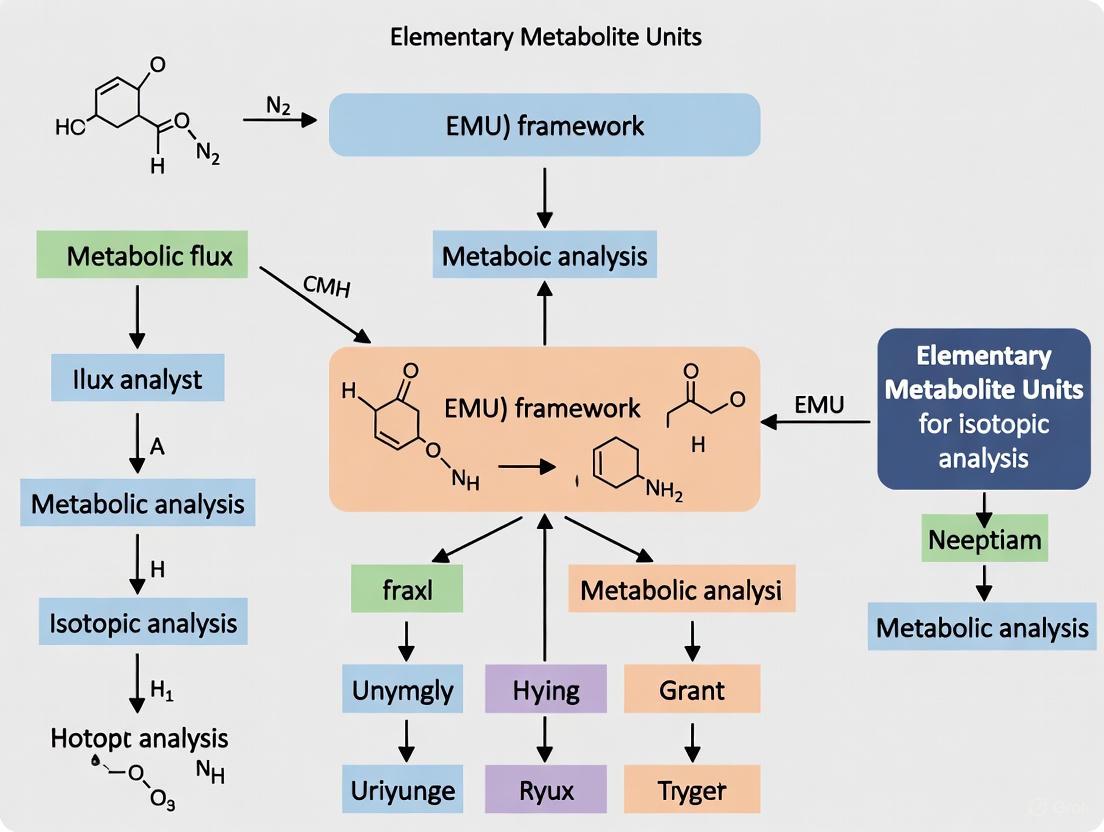

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for implementing EMU-based metabolic flux analysis:

Protocol Steps in Detail

Step 1: Network Definition and Atom Transition Mapping

- Reconstruction: Build a stoichiometric model of the metabolic network including all relevant reactions [7].

- Atom Tracking: For each reaction, define the atom transition map specifying how atoms in the substrates map to atoms in the products [1] [4].

- Example: For the condensation reaction Aâ‚â‚‚ + B₠→ Câ‚₂₃, the mapping shows how atoms from A and B combine to form C [1].

Step 2: EMU Decomposition Algorithm

- Bottom-Up Approach: Begin with the EMU size needed for the measured metabolites and identify all contributing smaller EMUs [1].

- Minimal Set Identification: The algorithm identifies the minimum number of EMUs required to simulate the measurable labeling patterns [1] [2].

- Iterative Process: For each product EMU, identify all substrate EMUs that contribute atoms to it, continuing until reaching substrate EMUs [4].

Step 3: EMU Balance Equations

- Equation Formulation: Set up mass balance equations for each EMU in the decomposed network [1].

- Flix Representation: Express each EMU balance as a function of metabolic fluxes and contributing EMUs:

Step 4: Flux Estimation and Validation

- Parameter Estimation: Solve the inverse problem using iterative least-squares fitting to determine fluxes from experimental labeling data [1] [7].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate confidence intervals for estimated fluxes to assess reliability [7] [5].

- Validation: Compare simulated labeling patterns with experimental data to verify model accuracy [1].

Adjacency Matrix Implementation

The adjacency matrix method provides a systematic approach for EMU decomposition:

- Matrix Construction: Create a square matrix with all metabolites as both row and column indices [4].

- Connectivity Representation: Each element indicates reaction(s) connecting reactant (row) to product (column) [4].

- Substrate Identification: Columns without elements represent network substrates [4].

- EMU Tracing: Use breadth-first search to identify all precursor EMUs for a target EMU [4].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EMU-Based MFA

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-¹³C]glucose, [U-¹³C]glucose [5] | Create distinct labeling patterns for flux observation |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, NMR Spectroscopy [1] [7] | Measure isotopic labeling distributions in metabolites |

| Software Platforms | EMUlator (Python) [4], Metran [6] | Implement EMU decomposition and flux calculation |

| Mathematical Tools | Adjacency Matrix [4], EMU Basis Vectors [5] | Network decomposition and tracer selection design |

Tracer Selection Guidance

The EMU basis vector methodology enables rational tracer selection by:

- Decoupling Substrate Labeling: EMU basis vectors represent substrate labeling independent of fluxes [5] [6].

- Flux Observability: The number of independent EMU basis vectors limits how many free fluxes can be determined [5].

- Optimal Tracer Identification: Select tracers that maximize independent EMU basis vectors for improved flux resolution [5].

The EMU framework represents a fundamental advancement in metabolic flux analysis by focusing computational resources on the minimal atomic subsets needed to simulate isotopic labeling. Through its efficient decomposition algorithm and reduced variable count, EMU modeling enables studies of complex metabolic networks with multiple isotopic tracers that were previously computationally prohibitive. The continued development of EMU-based tools and methodologies promises to further enhance our ability to quantify metabolic fluxes in increasingly complex biological systems.

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) has emerged as a tool of great significance for metabolic engineering and mammalian physiology, providing critical insights into cellular physiology in fields ranging from metabolic engineering to the study of human metabolic disease [1]. The most powerful methods for flux determination in complex biological systems utilize stable isotopes, where metabolic conversion of isotopically labeled substrates generates molecules with distinct labeling patterns that can be detected by mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [1]. Quantitative interpretation of the resulting isotopomer data requires mathematical models that describe the relationship between metabolic fluxes and observed isotopomer abundances [1]. Traditional modeling approaches, particularly the isotopomer and cumomer methods, have faced significant computational challenges that limit their practical application, especially when using multiple isotopic tracers—a limitation that the Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework successfully overcomes [1] [8].

The Limitations of Traditional Modeling Approaches

Computational Complexity of Isotopomer and Cumomer Methods

Isotopomers are defined as isomers of a metabolite that differ only in the labeling state of their individual atoms. For a metabolite comprising N atoms that may be in one of two (labeled or unlabeled) states, 2N isotopomers are possible [1]. This creates a combinatorial explosion that dramatically increases computational requirements:

Table 1: Computational Complexity of Traditional Methods for Glucose Analysis

| Tracer Type | Number of Atoms Considered | Isotopomers/Cumomers | EMUs Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-13 only | 6 carbon atoms | 64 | ~100s |

| Hydrogen only | 7 stable hydrogen atoms | 128 | ~100s |

| Carbon + Hydrogen | 6 carbon + 7 hydrogen atoms | 8,192 | ~100s |

| C, H, & O tracers | 6C + 7H + 6O atoms | >2,000,000 | 354 |

The fundamental limitation of both isotopomer and cumomer methods is that they require solving for the complete set of all possible isotopomers/cumomers, regardless of whether this full complexity is needed to simulate actual measurements [1]. The cumomer method, while providing an efficient procedure for solving isotopomer models, cannot solve this scalability problem because there remains a one-to-one relationship between cumomers and isotopomers [1]. This computational burden has historically restricted the realm of tracer experiments to single tracers, despite the recognized power of multiple isotopic tracers for elucidating complex physiology [1].

The EMU Framework: A Novel Approach

Conceptual Foundation

The Elementary Metabolite Units framework introduces a fundamentally different approach based on a highly efficient decomposition method that identifies the minimum amount of information needed to simulate isotopic labeling within a reaction network [1]. An EMU is defined as a moiety comprising any distinct subset of a compound's atoms [1]. For example, metabolite A consisting of 3 atoms has 7 possible EMUs: 3 EMUs of size 1 (A1, A2, A3), 3 EMUs of size 2 (A12, A13, A23), and 1 EMU of size 3 (A123), where the subscript denotes the atoms included in the EMU [1].

The key insight of the EMU framework is that simulating isotopic labeling often requires only a very small fraction of all possible EMUs, in stark contrast to isotopomer and cumomer methods that always use the complete set of all possible isotopomers/cumomers [1]. This bottom-up approach significantly reduces the number of system variables without any loss of information, enabling efficient simulation of labeling distributions for multiple isotopic tracers [1] [8].

EMU Reactions and Simulation

The EMU framework introduces the concept of EMU reactions, which provide the mathematical basis for simulating mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) [1]. Three fundamental reaction types illustrate how MIDs of products are determined:

- Condensation reactions: The MID of product C123 is determined by the convolution of MIDs of EMUs A12 and B1: C123 = A12 × B1

- Cleavage reactions: The MID of product C123 equals the MID of A123

- Unimolecular reactions: The MID of product C123 equals the MID of A123

For the condensation reaction, the M+0 abundance of C123 is calculated as the product of M+0 abundances of A12 and B1: C123,M+0 = A12,M+0 · B1,M+0 [1]. The full MID is obtained from the convolution (Cauchy product) of the MIDs of the precursor EMUs [1]. This efficient mathematical framework enables accurate simulation of isotopic labeling with dramatically reduced computational requirements.

Quantitative Advantages and Performance

Computational Efficiency Gains

The EMU framework provides substantial computational advantages over traditional methods, particularly for complex systems involving multiple isotopic tracers [1] [8]. In a typical carbon-13 labeling system, the total number of equations that needs to be solved is reduced by one order-of-magnitude (100s EMUs vs. 1000s isotopomers) [1]. The most dramatic efficiency gains are observed when modeling systems with multiple tracers. For example, analysis of the gluconeogenesis pathway with 2H, 13C, and 18O tracers requires only 354 EMUs, compared to more than 2 million isotopomers [1] [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Modeling Frameworks

| Framework | Number of Variables | Computational Time | Multi-Tracer Capability | Information Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopomer | Very high (1000s to millions) | Prohibitive for complex systems | Limited | Complete |

| Cumomer | Same as isotopomers | More efficient than isotopomer but still limited | Limited | Complete |

| EMU | Low (100s) | Significantly reduced | Excellent | Complete |

Application to Cancer Metabolism Research

The EMU framework has proven particularly valuable in cancer metabolism research, where understanding metabolic reprogramming is critical [9]. Cancer cells alter metabolic pathways in different contexts, leading to complex metabolic heterogeneity within tumors [9]. The ability of the EMU framework to efficiently handle multiple isotopic tracers enables researchers to characterize how cancer cells utilize environmental resources to evolve, spread, and survive therapies [9]. Isotope tracing combined with metabolic flux analysis using the EMU approach provides insights into how cancer cells reprogram their metabolism in response to standard-of-care therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy [9].

Experimental Protocols for EMU-Based MFA

Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction

For cell culture studies, begin by growing cells in appropriate media containing stable isotope-labeled substrates (e.g., 13C-glucose, 15N-glutamine, or 2H-labeled compounds) [9]. Ensure metabolic and isotopic steady state by maintaining cells in labeled media for sufficient time (typically 2-3 doubling times for metabolic steady state and additional time for isotopic steady state) [10]. Quench metabolism rapidly using cold organic solvent such as acetonitrile:methanol:formic acid (74.9:24.9:0.2, v/v/v) maintained at -20°C [10] [9]. This stops all enzymatic activity immediately, preserving metabolic profiles. Extract intracellular metabolites using the cold organic solvent solution, incorporating stable-labeled internal standards such as l-Phenylalanine-d8 and l-Valine-d8 for quality control and normalization [10]. Centrifuge extracts at high speed (e.g., 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C) to remove precipitated protein and cellular debris, then transfer supernatant to clean vials for analysis [10].

Chromatographic Separation and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Separate metabolites using appropriate chromatographic methods based on the chemical properties of your target metabolites. For polar metabolites relevant to central carbon metabolism, employ hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) with a Waters Atlantis HILIC Silica column or equivalent [10]. Prepare mobile phase A consisting of 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate in LC/MS-grade water, and mobile phase B consisting of 0.1% formic acid in LC/MS-grade acetonitrile [10]. Use a gradient elution program optimized for your metabolite panel, typically starting with high organic content (e.g., 85% B) and gradually increasing aqueous content. Analyze samples using high-resolution accurate mass instrumentation such as an Orbitrap mass spectrometer, operating in both positive and negative ionization modes to maximize metabolite coverage [10]. For gas chromatography, derivative polar metabolites to increase volatility using appropriate derivatization agents such as MSTFA (N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) after extraction [9].

Data Processing and EMU Simulation

Process raw mass spectrometry data to extract mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) for target metabolites. Use software tools such as MetaboAnalyst 6.0 for initial data processing, normalization, and statistical analysis [9]. For EMU-based flux analysis, implement the EMU decomposition algorithm to identify the minimal set of EMUs required to simulate the measured MIDs [1]. Construct EMU balance equations based on the network stoichiometry and known atomic transitions, then solve for metabolic fluxes using iterative least-squares fitting procedures that minimize the difference between simulated and measured MIDs [1]. Apply appropriate statistical methods such as Monte Carlo sampling or bootstrap analysis to determine confidence intervals for estimated fluxes [1].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EMU-Based MFA

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isotope-Labeled Substrates | 13C-Glucose (e.g., [U-13C] or [1,2-13C]) | Tracing carbon fate through metabolic pathways |

| 15N-Glutamine | Studying nitrogen metabolism and amino acid utilization | |

| 2H-Labeled compounds (e.g., 2H2O) | Probing hydrogen exchange and lipid metabolism | |

| Extraction Solvents | Acetonitrile:methanol:formic acid (74.9:24.9:0.2) | Quenching metabolism and extracting polar metabolites |

| Cold methanol (-20°C or -80°C) | Rapid metabolic quenching | |

| Internal Standards | l-Phenylalanine-d8 | Quality control for sample preparation and analysis |

| l-Valine-d8 | Normalization of extraction efficiency and instrument performance | |

| Chromatography | HILIC columns (e.g., Waters Atlantis HILIC Silica) | Separation of polar metabolites for mass spectrometry |

| GC columns (e.g., DB-5MS) | Separation of volatile metabolites or derivatives | |

| Computational Tools | EMU decomposition algorithms | Identifying minimal EMU sets for efficient simulation |

| MetaboAnalyst 6.0 [9] | Statistical analysis and visualization of metabolomics data | |

| Least-squares fitting routines | Flux estimation from isotopomer data |

The Elementary Metabolite Units framework represents a significant advancement in metabolic flux analysis by overcoming the fundamental computational limitations of traditional isotopomer and cumomer methods. By focusing on the minimal set of metabolic subunits needed to simulate isotopic labeling, the EMU framework reduces computational complexity by orders of magnitude while preserving complete information about the system [1] [8]. This enables researchers to design more sophisticated tracer experiments using multiple isotopic labels simultaneously, providing unprecedented insights into complex metabolic networks, particularly in cancer metabolism and other areas where metabolic plasticity plays a critical role in disease progression and treatment response [9]. The continued development and application of the EMU framework promises to further advance our understanding of cellular metabolism in health and disease.

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) represents a cornerstone technique for quantitatively understanding cellular physiology in fields ranging from metabolic engineering to the study of human metabolic disease [2] [1]. A pivotal advancement in MFA has been the integration of stable isotope tracing, where isotopically labeled substrates are metabolized by cells, generating molecules with distinct labeling patterns that can be detected by mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [1]. The computational interpretation of these labeling data, however, has been hampered by the inherent complexity of modeling all possible isotopic isomers (isotopomers) within metabolic networks, particularly when multiple isotopic tracers are employed [2]. The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework was developed specifically to overcome this fundamental limitation. The EMU decomposition algorithm provides a novel, bottom-up modeling approach that identifies the minimum amount of information required to simulate isotopic labeling without any loss of information, thereby enabling the efficient analysis of complex labeling experiments that were previously computationally intractable [2] [1].

Theoretical Foundation of the EMU Framework

The Computational Challenge in Isotopic Modeling

Traditional methods for modeling isotopic distributions, such as the isotopomer and cumomer methods, require balancing equations for all possible labeling states of a metabolite. For a metabolite with N atoms, 2^N isotopomers are possible. This number becomes astronomically large for multiple tracers. For instance, analysis of the gluconeogenesis pathway with ²H, ¹³C, and ¹â¸O tracers can require modeling over two million isotopomers [2] [1]. The cumomer method, while providing an efficient solution procedure, does not reduce the number of variables, as there remains a one-to-one relationship between cumomers and isotopomers [1]. This limitation historically restricted the realm of practical tracer experiments primarily to single tracers, despite the recognized power of multiple isotopic tracers for elucidating complex physiology [2].

Elementary Metabolite Units (EMUs): A Definition

An Elementary Metabolite Unit is defined as a moiety comprising any distinct subset of a compound's atoms [2] [1]. Consider a metabolite A consisting of 3 atoms (A1, A2, A3). The possible EMUs include:

- 3 EMUs of size 1: Aâ‚, Aâ‚‚, A₃

- 3 EMUs of size 2: Aâ‚â‚‚, Aâ‚₃, A₂₃

- 1 EMU of size 3: Aâ‚₂₃

In general, for a metabolite with N atoms, 2^N -1 EMUs are possible [1]. The key innovation of the EMU framework is that it does not require the complete set of all possible EMUs. Instead, through its decomposition algorithm, it identifies and utilizes only a very small, relevant fraction of EMUs needed to simulate the measured labeling patterns [1].

The EMU Decomposition Algorithm

The EMU decomposition algorithm is a bottom-up approach that traces the flow of atomic arrangements through the metabolic network. The algorithm identifies the minimal set of EMUs required to compute the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) for a metabolite of interest by working backwards from the target EMU through the network's atom transitions [11]. This process involves recursively identifying all precursor EMUs that contribute atoms to the target EMU, continuing until the network substrates are reached. The result is a dramatically simplified set of balance equations. For a typical ¹³C-labeling system, this reduces the number of equations by an order of magnitude (100s of EMUs versus 1000s of isotopomers) [2] [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Modeling Frameworks for a Gluconeogenesis Pathway Model

| Modeling Framework | Number of Variables | Computational Efficiency | Multi-Tracer Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopomer | >2,000,000 | Low | Limited |

| Cumomer | >2,000,000 | Medium | Limited |

| EMU | 354 | High | Excellent |

Computational Implementation and Protocols

Adjacency Matrix-Based Decomposition

A powerful implementation of the EMU decomposition algorithm utilizes an adjacency matrix approach, which provides an intuitive, graph-theoretical representation of the metabolic network [11]. In this representation, the metabolic network is transformed into a directed graph where metabolites are nodes and reactions are edges.

The implementation involves two primary stages:

- Metabolite Adjacency Matrix (MAM): A square matrix where row and column coordinates represent metabolites. Elements in the matrix indicate connecting reactions between reactants (rows) and products (columns). Substrates are identified as columns without elements, and final products are identified as rows without elements [11].

- EMU Adjacency Matrix (EAM): The MAM is decomposed into smaller EAMs, each corresponding to a specific EMU size. The decomposition starts from the target EMU (e.g., Gluâ‚₂₃₄₅ for glutamate) and iteratively traces backwards through the network using the known atom transitions to identify all contributing precursor EMUs of smaller sizes until network substrates are reached [11].

Table 2: Key Software Tools Implementing the EMU Framework

| Software Tool | Platform/Language | Key Features | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX(v3) [12] | C++ backend with Python interface | High-performance; supports isotopically stationary & nonstationary MFA; Bayesian inference | Universal for 13C-MFA scenarios |

| EMUlator [11] | Python | Novel adjacency matrix method; intuitive and transparent modeling | Steady-state metabolic modeling |

| Metran | Matlab | EMU-based modeling | Steady-state 13C-MFA |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of the EMU decomposition algorithm using the adjacency matrix approach:

Protocol for EMU-Based Metabolic Network Decomposition

Objective: To decompose a metabolic network into its constituent EMUs for efficient simulation of mass isotopomer distributions.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Metabolic network stoichiometry with atom transition mappings

- Python environment with EMUlator package [11] or 13CFLUX(v3) [12]

- List of target metabolites for which labeling patterns need to be simulated

Procedure:

- Network Definition: Define the metabolic network stoichiometry, including all reactions, metabolites, and atom transitions. For example, in the TCA cycle, specify how carbon atoms from acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate are rearranged through each reaction [11].

- Matrix Construction: Transform the metabolic network into a Metabolite Adjacency Matrix (MAM). Represent all metabolites as both row and column coordinates, with matrix elements indicating connecting reactions.

- Target Identification: Identify the specific EMUs of interest (e.g., Gluâ‚₂₃₄₅ for glutamate labeling simulation).

- Recursive Decomposition: For each target EMU, recursively trace backwards through the EAM to identify all precursor EMUs:

- For condensation reactions: Identify all combinations of smaller EMUs that contribute atoms to the target EMU.

- For cleavage and unimolecular reactions: Identify the direct precursor EMU.

- Network Reduction: Simplify the resulting EAMs by:

- Eliminating unimolecular reaction columns and renaming corresponding rows with their precursors.

- Combining multiple rows with identical metabolite names.

- Identifying and combining equivalent EMUs arising from rotationally symmetric molecules.

- Equation Formulation: Set up mass balance equations for each EMU in the reduced system, relating EMU abundances to metabolic fluxes and substrate labeling.

- Validation: Verify the completeness of the decomposition by ensuring all pathways from substrates to target EMUs are captured.

Applications and Advanced Extensions

High-Throughput Flux Phenotyping

The computational efficiency of the EMU framework enables high-throughput flux analysis. For instance, EMUlator was applied to understand the phosphoketolase flux in Clostridium acetobutylicum xylose catabolism. The EMU-based simulation revealed a correlation between phosphoketolase flux and the fractional labeling of acetate, enabling a novel, non-invasive methodology for quantitatively monitoring this pathway in vivo [11].

Multi-Tracer and Isotopically Nonstationary MFA

The EMU framework is particularly advantageous for complex labeling studies. Modern software implementations like 13CFLUX(v3) leverage the EMU framework to support both isotopically stationary and nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) with multi-tracer designs [12]. The system automatically chooses between cumomer and EMU representations using a heuristic to maximize dimensionality reduction, handling systems that often exceed 1000 dimensions [12].

Bayesian Inference and Uncertainty Quantification

Recent advances have integrated the EMU framework with Bayesian inference approaches. The computational efficiency of EMU simulations enables comprehensive uncertainty quantification and robust statistical analysis of flux estimates, allowing researchers to address novel questions about the impact of model uncertainty on estimated fluxes [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX(v3) [12] | High-performance simulation engine for 13C-MFA | C++ backend with Python interface; supports multi-experiment data integration |

| EMUlator [11] | Python-based isotope simulator using adjacency matrix method | Open-source; intuitive graph-based representation of metabolic networks |

| FluxML [12] | Universal flux modeling language | XML-based format for describing metabolic models, atom transitions, and experimental data |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., [1,2-¹³C]glucose) | Generate distinct labeling patterns in metabolic networks | Enable tracing of atom fates through biochemical pathways |

| GC-MS or LC-MS/MS | Measure mass isotopomer distributions of intracellular metabolites | Provide experimental data for flux estimation |

| SUNDIALS CVODE [12] | Solver for ordinary differential equations in INST-MFA | Used for isotopically nonstationary simulations with adaptive step size control |

| 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide | 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide | | RUO | High-purity 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide for research. A versatile beta-hydroxyamide intermediate. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 1-Butanone, 3-hydroxy-1-phenyl- | 1-Butanone, 3-hydroxy-1-phenyl-, CAS:13505-39-0, MF:C10H12O2, MW:164.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework represents a transformative computational approach in metabolic flux analysis (MFA) that has significantly advanced our capability to model isotopic labeling in complex biological systems. Metabolic flux analysis has emerged as a tool of great significance for metabolic engineering and mammalian physiology, enabling researchers to quantify the integrated responses of metabolic networks [2] [1]. Traditional MFA methodologies faced a substantial limitation: the enormous number of isotopomer or cumomer equations that needed to be solved, particularly when utilizing multiple isotopic tracers. This computational restriction severely constrained the ability of researchers to fully leverage the power of multiple isotopic tracers in elucidating physiology in realistic scenarios comprising complex bioreaction networks [2].

The EMU framework addresses this fundamental challenge through a novel decomposition method that identifies the minimum amount of information required to simulate isotopic labeling within a reaction network. This framework utilizes knowledge of atomic transitions occurring in network reactions to generate functional units called EMUs, which form the basis for generating system equations that describe the relationship between fluxes and stable isotope measurements [2] [1]. The power of this approach lies in its ability to simulate isotopomer abundances identical to those obtained using traditional isotopomer and cumomer methods, while requiring significantly less computation time – typically reducing the number of equations that need to be solved by an order of magnitude (100s EMUs vs. 1000s isotopomers) for a typical 13C-labeling system [2].

Fundamental Concepts of EMU Reactions

Definition of Elementary Metabolite Units

An Elementary Metabolite Unit is formally defined as a moiety comprising any distinct subset of a compound's atoms [2] [1]. Consider a metabolite A consisting of 3 atoms. The possible EMUs for this metabolite include: 3 EMUs of size 1 (Aâ‚, Aâ‚‚, A₃), 3 EMUs of size 2 (Aâ‚â‚‚, Aâ‚₃, A₂₃), and 1 EMU of size 3 (Aâ‚₂₃), where the subscript denotes the atoms included in the EMU. In general, for a metabolite comprising N atoms, 2^N -1 EMUs are theoretically possible [2]. However, in practical applications, only a very small fraction of all possible EMUs is typically required to simulate isotopic labeling, making the approach highly efficient [1].

The EMU framework differs fundamentally from isotopomer and cumomer methods in that it does not require the complete set of all possible isotopomers/cumomers for simulation. Instead, it employs a bottom-up modeling approach that identifies and utilizes only the minimal set of EMUs needed to simulate the measurements of interest [1]. This approach becomes particularly advantageous when analyzing complex systems with multiple isotopic tracers, as demonstrated by the analysis of gluconeogenesis pathway with ²H, ¹³C, and ¹â¸O tracers, which required only 354 EMUs compared to more than two million isotopomers [2].

Types of EMU Reactions

The EMU framework categorizes biochemical transformations into three fundamental reaction types that govern isotopic labeling patterns: condensation reactions, cleavage reactions, and unimolecular reactions. Each reaction type follows distinct rules for determining the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of products based on the labeling patterns of substrates [1].

Mathematical Formalism of EMU Reactions

Computational Basis of EMU Reactions

The mathematical foundation of EMU reactions relies on the concept of convolution operations to determine mass isotopomer distributions of products from substrate EMUs. For condensation reactions, the MID of the product EMU is calculated as the convolution (Cauchy product) of the MIDs of the substrate EMUs [1]. For a condensation reaction where EMU Câ‚₂₃ is formed from EMU Aâ‚â‚‚ and EMU Bâ‚, the mass isotopomer distribution of Câ‚₂₃ is given by:

Câ‚₂₃ = Aâ‚â‚‚ × Bâ‚

Where '×' denotes the convolution operation. For example, the M+0 abundance of Câ‚₂₃ equals the product of M+0 abundances of Aâ‚â‚‚ and Bâ‚: Câ‚₂₃,M+0 = Aâ‚â‚‚,M+0 · Bâ‚,M+0 [1].

For cleavage and unimolecular reactions, the MID of the product EMU is identical to the MID of the substrate EMU. In the case of cleavage reactions, atoms not transferred to the product EMU are simply not considered in the EMU reaction [1]. This mathematical simplicity contributes significantly to the computational efficiency of the EMU framework.

Table 1: Mathematical Operations for Different EMU Reaction Types

| Reaction Type | Mathematical Operation | Example | Information Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condensation | Convolution (×) | Câ‚₂₃ = Aâ‚â‚‚ × Bâ‚ | MIDs of all substrate EMUs |

| Cleavage | Direct Transfer | Câ‚₂₃ = Aâ‚₂₃ | MID of single substrate EMU |

| Unimolecular | Identity Transfer | Bâ‚₂₃ = Aâ‚₂₃ | MID of single substrate EMU |

EMU Framework Implementation

The implementation of the EMU framework typically follows a structured decomposition algorithm that identifies the minimal set of EMUs required for simulation. This process can be efficiently implemented using adjacency matrix approaches, which provide a mathematical representation of metabolic networks as directed graphs [4]. The EMUlator software, a Python-based isotope simulator, utilizes this approach to transform metabolic networks into metabolite adjacency matrices (MAM), which are subsequently decomposed into EMU adjacency matrices (EAM) [4].

The decomposition process begins with the target EMU size that needs to be simulated and iteratively identifies all precursor EMUs through the adjacency matrix until the substrates of the network are reached. This method systematically reduces the computational complexity while preserving all essential information for accurate simulation of isotopic labeling [4]. The adjacency matrix approach provides an intuitive and straightforward implementation that can be conveniently mastered for various customized purposes in metabolic flux analysis.

Experimental Protocols for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

Stable Isotope Tracer Preparation

The foundation of any EMU-based metabolic flux analysis begins with careful preparation of stable isotope tracers. Different stable isotopes including ¹³C, ²H, ¹âµN, and ¹â¸O are utilized for various metabolic pathways in fluxomic analyses [13]. The selection of tracer depends on the specific pathways under investigation:

Carbon Backbone Tracing: ¹³C-labeled substrates (e.g., [U-¹³C]-glucose, [1,2-¹³C]-glucose) are most commonly used to track carbon fate through central metabolic pathways including glycolysis, TCA cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway [14] [15].

Oxygen Exchange Studies: Hâ‚‚[¹â¸O] based labeling enables tracking of oxygen exchange rates in metabolic pathways, particularly useful for studying Krebs cycle dynamics and phosphotransfer networks [13].

Nitrogen Metabolism: ¹âµN labeled tracers (e.g., ¹âµN-glutamine) allow investigation of amino acid metabolism and nucleotide biosynthesis [13].

Protocol for tracer administration varies depending on the biological system. For in vitro cell culture studies, tracers are typically administered by replacing culture media with media containing the isotopic tracers at appropriate concentrations [13] [16]. For in vivo studies, more sophisticated administration methods including continuous infusion or bolus injection may be employed [15].

Sample Processing and Metabolite Extraction

Proper sample processing is critical for accurate determination of isotopic labeling patterns. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for metabolite extraction from cell culture systems:

Rapid Quenching: Terminate metabolic activity rapidly using cold quenching solutions (e.g., liquid nitrogen-cooled methanol for microbial systems or rapid washing with cold saline for mammalian cells) [13].

Metabolite Extraction:

- Add 1 mL of -20°C methanol:water (80:20, v/v) extraction solvent per 10ⷠcells

- Vortex vigorously for 30 seconds

- Add 0.5 mL of chloroform per 10â· cells

- Vortex for an additional 30 seconds

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Collect polar phase (upper layer) for analysis of water-soluble metabolites [13] [16]

Sample Concentration: Evaporate polar phase to dryness under nitrogen stream and reconstitute in appropriate solvent for subsequent analysis by GC-MS or LC-MS [13].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Mass spectrometry serves as the primary analytical technique for measuring isotopic labeling in EMU-based studies. Both gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) platforms are commonly employed:

Table 2: Mass Spectrometry Platforms for Isotopic Labeling Analysis

| Platform | Ionization Method | Metabolite Coverage | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Electron Impact (EI) | Central carbon metabolites, organic acids, amino acids | High reproducibility, quantitative analysis [13] [17] |

| LC-MS | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) | Broad coverage including nucleotides, cofactors | Untargeted analysis, high sensitivity [14] [16] |

| Tandem MS | Multiple | Fragment-specific labeling information | Improved flux resolution, complex networks [17] |

For GC-MS analysis, metabolites typically require chemical derivatization to increase volatility. Common derivatization methods include:

- Methoxyamination: Protection of carbonyl groups using methoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine

- Silylation: Addition of trimethylsilyl groups using MSTFA or BSTFA + 1% TMCS [17]

LC-MS methods typically employ reverse-phase chromatography with volatile buffers (e.g., ammonium acetate or formate) compatible with mass spectrometric detection [16].

Data Processing and Isotopologue Quantification

Raw mass spectrometry data requires specialized processing to extract accurate isotopologue distributions:

- Peak Integration: Extract chromatographic peaks for each metabolite and its isotopologues

- Natural Isotope Correction: Correct raw isotopologue abundances for naturally occurring isotopes using appropriate algorithms [17]

- Mass Isotopomer Distribution: Calculate fractional abundance of each mass isotopomer (M+0, M+1, M+2, etc.)

- Labeling Pattern Analysis: For positional labeling information, utilize tandem MS or NMR approaches

Advanced computational tools such as MetTracer enable global tracking of isotopically labeled metabolites with metabolome-wide coverage, significantly expanding the scope of EMU-based studies [16]. These tools leverage high coverage of untargeted metabolomics and high accuracy of targeted extraction to identify and quantify hundreds of labeled metabolites simultaneously.

Applications in Metabolic Research

Analysis of Central Carbon Metabolism

The EMU framework has been extensively applied to investigate flux distributions in central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and TCA cycle. The approach has been particularly valuable in characterizing metabolic alterations in various disease states and engineered biological systems [14] [15].

For example, EMU-based ¹³C metabolic flux analysis revealed distinct pathway utilization in cancer cells, including enhanced glycolysis (Warburg effect), glutamine dependency, and reductive carboxylation [15]. In a study of clear cell renal cell carcinoma, in vivo tracing with U-¹³C₆-glucose combined with EMU modeling demonstrated increased glycolysis and suppressed TCA oxidation in tumors [15].

Table 3: Selected Tracers and Their Applications in Central Carbon Metabolism

| Tracer | Metabolite Readouts | Information Obtained | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1,2-¹³C]glucose | Lactate M+1, M+2 | PPP overflow/glycolysis ratio | Cancer metabolism, proliferating cells [14] |

| [U-¹³C]glutamine | Citrate M+5, Malate M+3 | Reductive carboxylation flux | Hypoxic cancer cells, mitochondrial dysfunction [14] [15] |

| 50% [U-¹²C]:50% [U-¹³C] glucose | Glucose-6-phosphate M+3, FBP M+3 | Glycolytic reversibility | Metabolic flexibility, substrate cycling [14] |

| Hâ‚‚[¹â¸O] | Krebs cycle intermediates | Oxygen exchange rates | Cellular energetics, enzyme activities [13] |

Neuron-Glia Metabolic Interactions

Isotope tracing with EMU modeling has significantly advanced our understanding of brain metabolism and neuron-glia interactions. The technique has revealed the metabolic collaboration between neurons and astrocytes that is essential to sustain neurotransmission through the glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle [18].

Studies utilizing U-¹³C₆-glucose and U-¹³C₅-glutamine tracing have demonstrated metabolic flexibility in neurons, with the capability to utilize alternative substrates when glucose metabolism is impaired. For instance, inhibition of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) promotes glutamate oxidation to maintain TCA cycle activity, as evidenced by altered ¹³C-enrichment patterns from different tracers [15]. These findings have important implications for understanding and treating neurodegenerative diseases where metabolic alterations contribute to disease progression [18].

In Vivo Metabolic Flux Analysis

Recent methodological advances have extended EMU-based metabolic flux analysis to in vivo systems, enabling investigation of whole-body metabolism in physiologically relevant contexts. These approaches have revealed systemic metabolic interactions between different tissues and organs [16] [15].

A notable application includes the discovery of tumor-liver metabolic coupling in zebrafish models, where alanine serves as a circulating carrier that enables nitrogen removal from tumors while supporting hepatic gluconeogenesis to meet the high glucose demand of cancer cells [15]. Such system-level metabolic insights would be challenging to obtain without the computational efficiency of the EMU framework for analyzing complex labeling data from in vivo tracer experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers | Label metabolic pathways | ¹³C-glucose, ¹³C-glutamine, H₂¹â¸O | Purity, enrichment level, cost [14] [13] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Enable GC-MS analysis | MSTFA, BSTFA, methoxyamine | Completeness of derivation, stability [17] |

| Extraction Solvents | Metabolite extraction | Cold methanol, chloroform, water | Extraction efficiency, metabolite coverage [13] |

| Chromatography Columns | Metabolite separation | GC columns (DB-5MS), LC columns (HILIC) | Resolution, peak shape, retention [17] [16] |

| Internal Standards | Quantification normalization | ¹³C-labeled internal standards | Not present in biological system [16] |

| Software Tools | Data analysis and modeling | EMUlator, MetTracer, OpenFlux | Algorithm efficiency, user interface [17] [4] |

| Triacontyl hexacosanoate | Triacontyl Hexacosanoate | High-Purity Ester | Triacontyl hexacosanoate, a high-purity long-chain ester. For research into wax biosynthesis & material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Lithium fluorosulfate | Lithium Fluorosulfate | Battery Research Material | Bench Chemicals |

The EMU framework has revolutionized metabolic flux analysis by providing a computationally efficient methodology for modeling isotopic labeling in complex biological systems. The framework's elegant mathematical foundation, based on decomposition into elementary metabolite units and simulation of EMU reactions through convolution operations, has enabled researchers to address biological questions that were previously computationally intractable.

Future developments in EMU-based methodologies will likely focus on several key areas. First, integration with emerging analytical technologies, particularly global isotope tracing metabolomics approaches that provide metabolome-wide coverage of labeling patterns, will expand the scope of measurable fluxes [16]. Second, application to single-cell metabolomics may reveal metabolic heterogeneity in complex biological systems. Third, continued development of computational tools with improved user interfaces and integration with metabolic network reconstruction databases will make EMU-based flux analysis more accessible to non-specialists [4].

The EMU framework's ability to efficiently handle multiple isotopic tracers makes it particularly well-suited for investigating complex metabolic phenomena such as metabolic compartmentalization, intercellular metabolic coupling, and dynamic metabolic adaptations. As stable isotope tracing continues to evolve as an essential technology in metabolic research, the EMU framework will remain a cornerstone methodology for translating labeling measurements into quantitative biological insights.

The condensation, cleavage, and unimolecular transformations that form the basis of EMU reactions provide a comprehensive mathematical formalism for simulating the fate of isotopic labels through metabolic networks. By leveraging these fundamental reaction types, researchers can design informative tracer experiments, develop accurate computational models, and ultimately generate deeper understanding of metabolic physiology in health and disease.

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) is an indispensable tool in metabolic engineering and systems biology, enabling researchers to quantify intracellular metabolic reaction rates [2]. The most informative variant of this methodology, 13C-based Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), utilizes stable isotope tracers and analytical measurements to infer these fluxes [19]. However, a significant limitation of traditional MFA has been the computational burden associated with simulating isotopic labeling patterns, especially when using multiple isotopic tracers to probe complex metabolic networks [2] [1].

The core of the problem lies in the exponential increase of possible isotopic isomers (isotopomers) as metabolic networks grow in size and complexity. For a metabolite with N atoms that can be in one of two states (labeled or unlabeled), 2N isotopomers exist [2]. When multiple tracers are applied simultaneously (e.g., 2H, 13C, and 18O), this number multiplies dramatically. For glucose (C6H12O6), considering all carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms leads to approximately 190 million isotopomers [2] [1]. Traditional isotopomer and cumomer modeling approaches require solving balance equations for all these possibilities, resulting in systems with thousands to millions of variables that are computationally intensive to simulate [4] [20].

The Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework was developed specifically to address this computational bottleneck. This novel modeling approach, introduced by Antoniewicz et al., is based on a highly efficient decomposition method that identifies the minimum amount of information needed to simulate isotopic labeling within a reaction network [2] [8] [1]. By focusing only on the relevant subsets of atoms, the EMU framework dramatically reduces the number of system variables without any loss of information, enabling more efficient and comprehensive analysis of metabolic networks, particularly with multiple isotopic tracers [20].

The EMU Framework: Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

What is an Elementary Metabolite Unit?

An Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) is defined as a moiety comprising any distinct subset of a compound's atoms [2] [1]. The EMU framework represents a bottom-up modeling approach that systematically decomposes metabolites into these functional subunits, which form the new basis for generating system equations that describe the relationship between metabolic fluxes and stable isotope measurements [1].

The size of an EMU is defined as the number of atoms included in the subset. For a hypothetical metabolite A consisting of 3 atoms, there are 7 possible EMUs:

- 3 EMUs of size 1 (A1, A2, A3)

- 3 EMUs of size 2 (A12, A13, A23)

- 1 EMU of size 3 (A123)

The subscripts denote the specific atoms included in the EMU. It is important to note that atoms in an EMU are not necessarily connected by chemical bonds [2] [1]. In general, for a metabolite comprising N atoms, 2N-1 EMUs are theoretically possible. However, in practice, only a very small fraction of all possible EMUs is required to simulate isotopic labeling in metabolic networks [1].

EMU Reactions and Network Decomposition

The EMU framework introduces the concept of EMU reactions, which describe how these elemental units transform through biochemical reactions [1]. The framework distinguishes three fundamental reaction types:

- Condensation reactions: Two smaller EMUs combine to form a larger EMU. The mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of the product is obtained through the convolution of the MIDs of the precursor EMUs [1].

- Cleavage reactions: A larger EMU is split, and a smaller EMU is transferred to the product. The MID of the product EMU is identical to the MID of the precursor EMU [1].

- Unimolecular reactions: EMUs undergo rearrangement without changing their size or composition. The MID is preserved through the reaction [1].

The EMU decomposition algorithm is a crucial innovation that identifies the minimal set of EMUs required to simulate the measurable labeling patterns [2] [4]. This algorithm starts from the EMUs of interest (typically those corresponding to measurable metabolites) and works backward through the metabolic network, identifying only the precursor EMUs that contribute to the labeling of the target EMUs [4]. This approach eliminates the need to consider all possible isotopomers, focusing computational resources only on the relevant variables [4].

Figure 1: Conceptual overview of how the EMU framework reduces computational complexity compared to traditional modeling approaches. The EMU framework achieves an order of magnitude reduction in system variables by focusing only on metabolically relevant atom subsets.

Quantitative Analysis of Variable Reduction

Comparative Analysis of Model Complexity

The efficiency of the EMU framework becomes particularly evident when examining specific cases from metabolic research. The following table summarizes quantitative comparisons between traditional isotopomer/cumomer methods and the EMU approach across different metabolic systems:

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Variables in Isotopomer/Cumomer vs. EMU Frameworks

| Metabolic System | Tracers Applied | Isotopomers/Cumomers | EMUs Required | Reduction Factor | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical 13C-labeling system | 13C | 1000s variables | 100s variables | ~10-fold | [2] [8] [1] |

| Gluconeogenesis pathway | 2H, 13C, 18O | >2,000,000 isotopomers | 354 EMUs | ~5650-fold | [2] [8] [1] |

| Gluconeogenesis pathway | 2H, 13C | >30,000 cumomers | 300 EMUs | ~100-fold | [20] |

| E. coli model | 13C | Not specified | ~95% reduction | ~20-fold | [4] |

The data demonstrates that the EMU framework consistently reduces the number of system variables by approximately one to two orders of magnitude across different metabolic systems and tracer combinations [2] [20]. This reduction is most dramatic when multiple isotopic tracers are applied simultaneously, as the combinatorial complexity of traditional methods increases multiplicatively while the EMU approach maintains efficiency by focusing only on relevant atom transitions [2].

Mathematical Basis of Variable Reduction

The mathematical efficiency of the EMU framework stems from its fundamental difference in representing metabolic labeling states. While isotopomer models must account for all possible labeling configurations of a metabolite, the EMU framework decomposes the problem into smaller, independent subproblems [2] [1].

For a metabolite with N atoms, traditional isotopomer models require balancing 2N isotopomer species. In contrast, the EMU framework identifies only the k-sized EMUs that are necessary to simulate the measurable labeling data, where k is typically much smaller than N [1]. The number of possible k-sized EMUs for a metabolite with N atoms is given by the binomial coefficient C(N,k), which grows polynomially rather than exponentially [1].

Furthermore, through the decomposition algorithm, only a subset of these possible EMUs is actually required for simulation, as many EMUs are not interconnected to the measurable EMUs or are not affected by the applied tracers [4]. This dual reduction—focusing on smaller EMUs and then identifying only the relevant ones—explains the dramatic decrease in system complexity [2] [1].

Implementation Protocols and Methodologies

EMU Decomposition Workflow

The implementation of the EMU framework follows a systematic workflow that transforms a traditional metabolic network into an efficient EMU-based model:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EMU Decomposition Algorithm | Computational method | Identifies minimal set of EMUs needed for simulation | Core mathematics of EMU framework [2] |

| Adjacency Matrix | Data structure | Represents metabolic network as connected graph | Python implementation in EMUlator [4] |

| Metabolite Adjacency Matrix (MAM) | Modeling construct | Maps all metabolite connections in network | Transform network into square matrix [4] |

| EMU Adjacency Matrix (EAM) | Modeling construct | Maps EMU connections by size | Created iteratively from MAM [4] |

| 13CFLUX(v3) | Software platform | High-performance flux analysis with EMU support | C++ backend with Python interface [12] |

| EMUlator | Software tool | Python-based isotope simulator | Implements EMU via adjacency matrix [4] [21] |

Figure 2: Workflow for implementing the EMU framework, from network definition to simulation of labeling patterns. The EMU-specific steps (highlighted in yellow) represent the core innovations that reduce system complexity.

Protocol for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Metabolic network model with atom transitions

- EMU-compatible software (e.g., 13CFLUX, EMUlator, INCA, Metran)

- Isotopic labeling data (MS or NMR measurements)

- Nutrient uptake and secretion rates

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Network Definition and Atom Mapping

EMU Decomposition

Equation Formulation

System Solution and Flux Estimation

- Solve the system of EMU balance equations numerically

- Simulate mass isotopomer distributions for target metabolites

- Iteratively adjust flux parameters to minimize difference between simulated and experimental labeling data [19]

Validation and Quality Control:

- Verify that simulated labeling patterns match those obtained from traditional methods

- Confirm that the sum of all mass isotopomer fractions equals 1 for each metabolite

- Check consistency with external flux measurements [19]

Applications and Impact in Metabolic Research

Case Study: Gluconeogenesis with Multiple Tracers

The EMU framework enabled a comprehensive analysis of the gluconeogenesis pathway in cultured primary hepatocytes using a novel, custom-synthesized isotopic tracer [U-13C3,2H5]glycerol [20]. This study provided unprecedented insights into hepatic metabolism:

- Quantified gluconeogenesis contribution: 50±2% in hepatocytes from fed mice vs. 90±2% in hepatocytes from fasted mice [20]

- Revealed pathway equilibria: Phosphoglucoisomerase (PGI) reaction at 70±5% equilibrium, contrary to the common belief of 100% equilibrium [20]

- Characterized pentose phosphate pathway: Transketolase and transaldolase fluxes were small (<10% of gluconeogenesis flux) [20]

- Established precursor efficiency: Glycerol contributes ~30% to glucose production [20]

Critically, these results could not have been obtained with conventional isotopomer/cumomer methods due to the prohibitive computational burden of simulating over 30,000 cumomers [20]. The EMU framework accomplished this analysis with only 300 EMUs, representing a 100-fold reduction in system complexity [20].

High-Throughput Flux Estimation in Industrial Biotechnology

The EMUlator software, which implements the EMU framework through an adjacency matrix approach, has enabled high-throughput, non-invasive estimation of phosphoketolase flux in Clostridium acetobutylicum [4] [21]. This application demonstrates how the EMU framework facilitates rapid metabolic phenotyping:

- Non-invasive flux estimation: Correlated phosphoketolase flux with fractional labeling of extracellular acetate [4]

- High-throughput capability: Enabled systematic design and prediction of isotope-based metabolic models [4]

- Strain characterization: Provided quantitative understanding of phosphoketolase pathway in response to environmental and genetic perturbations [4]

The adjacency matrix implementation in EMUlator makes EMU modeling intuitively straightforward, allowing researchers to efficiently decompose complex networks and focus computational resources on biologically relevant questions [4].

Advanced Implementation: Software Tools and Computational Advances

Current Software Ecosystem

The EMU framework has been incorporated into several specialized software tools that make this powerful approach accessible to non-expert researchers:

Table 3: Software Tools Implementing the EMU Framework for Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Software Tool | Platform | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX(v3) | C++ backend with Python interface | Supports isotopically stationary/nonstationary MFA; uses EMU and cumomer methods; Bayesian inference | Microbial, plant, and mammalian cell flux analysis [12] |

| EMUlator | Python | Adjacency matrix-based EMU implementation; intuitive and transparent modeling | High-throughput flux estimation; educational purposes [4] [21] |

| Metran | MATLAB | EMU-based flux estimation; comprehensive statistical analysis | Cancer metabolism; microbial physiology [19] |

| INCA | MATLAB | Integration of 13C-MFA with kinetic modeling | Detailed analysis of metabolic regulation [19] |

The Adjacency Matrix Implementation

A significant advancement in EMU implementation is the adjacency matrix approach, which provides a graphically intuitive representation of the algorithm [4]. This method involves:

- Metabolite Adjacency Matrix (MAM): A square matrix with all metabolites in rows and columns, where elements indicate connecting reactions [4]

- EMU Decomposition: Starting from the target EMU size, work iteratively backward to identify precursor EMUs of decreasing sizes [4]

- EMU Adjacency Matrix (EAM): Separate matrices for each EMU size, showing connectivity between EMUs through biochemical reactions [4]

This implementation transforms the abstract mathematical decomposition into a visually comprehensible procedure, making the EMU framework more accessible to researchers with limited computational background [4].

The Elementary Metabolite Units framework represents a fundamental advancement in metabolic flux analysis by systematically addressing the computational limitations of traditional isotopomer and cumomer methods. Through its innovative decomposition algorithm that identifies the minimal information required to simulate isotopic labeling, the EMU framework achieves a consistent order-of-magnitude reduction in system variables—from thousands to hundreds in typical 13C-labeling systems, and from millions to hundreds when multiple isotopic tracers are applied simultaneously.

This dramatic reduction in computational complexity has enabled previously impossible metabolic studies, particularly those involving multiple isotopic tracers and complex metabolic networks. The framework's efficiency stems from its bottom-up approach, which focuses only on relevant atom subsets and their transformations through metabolic reactions, eliminating redundant variables while preserving all information necessary for accurate flux determination.

As metabolic research continues to address increasingly complex biological systems, the EMU framework provides an essential computational foundation that enables comprehensive, multi-tracer investigations of metabolic physiology. Its implementation in user-friendly software tools has democratized access to sophisticated flux analysis, empowering researchers across metabolic engineering, systems biology, and biomedical research to obtain quantitative insights into cellular metabolism that were previously beyond computational reach.

Implementing EMU: From Metabolic Network Modeling to Rational Tracer Design

A Step-by-Step Workflow for Building an EMU-Based Metabolic Model

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) is a cornerstone technique in metabolic engineering and systems biology, providing critical insights into the intracellular flow of carbon through biochemical networks [22]. When combined with stable isotope tracing, particularly using 13C-labeled substrates, MFA enables the precise quantification of metabolic fluxes that define cellular physiology [2] [23]. However, a significant computational challenge has traditionally limited the application of this powerful methodology: the exponentially large number of isotopomer variables that must be simulated, especially when using multiple isotopic tracers [1] [2].

The Elementary Metabolite Units (EMU) framework represents a transformative advancement in this field. Developed by Antoniewicz et al., this novel modeling approach identifies the minimal set of information required to simulate isotopic labeling patterns without any loss of information [1] [8]. By decomposing metabolites into distinct subsets of atoms (EMUs) rather than tracking all possible isotopomers, the framework achieves dramatic reductions in computational complexity—typically reducing the number of equations by an order of magnitude (from 1000s of isotopomers to 100s of EMUs) while producing identical simulation results [1] [2]. This efficiency gain is particularly valuable for analyzing complex labeling experiments involving multiple isotopic tracers (e.g., 2H, 13C, and 18O), where the EMU framework can reduce the system from millions of isotopomers to just hundreds of EMUs [1].

This protocol provides a comprehensive, practical guide to implementing the EMU framework for metabolic flux analysis, enabling researchers to build more efficient and scalable metabolic models for investigating cellular physiology and optimizing bioprocesses.

Materials and Equipment

Computational Tools and Software Environments

Table 1: Software Solutions for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Software Name | Platform/Language | Key Features | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenFLUX [23] | MATLAB | User-friendly spreadsheet interface for reaction definition; automated generation of EMU balance models | Steady-state 13C-MFA |

| EMUlator [4] [11] | Python | Novel adjacency matrix approach for EMU decomposition; intuitive graph-based implementation | Steady-state 13C-MFA |

| 13CFLUX [12] | C++ backend with Python interface | High-performance simulator supporting both isotopically stationary and nonstationary MFA; utilizes both cumomer and EMU methods | Advanced stationary and instationary 13C-MFA |

| INCA [4] | MATLAB | Comprehensive flux analysis tool with EMU implementation | Steady-state 13C-MFA |

Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Solutions

Table 2: Key Experimental Reagents for EMU-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled substrates | Tracer compounds for metabolic labeling; enable tracking of carbon fate through networks | Selection depends on pathways of interest; common tracers include [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine |

| Derivatization reagents | Chemical modification of metabolites for GC-MS analysis; enhance detection and separation | Selection depends on target metabolites; commonly used for amino acids, organic acids |

| Quenching solutions | Rapid halt of metabolic activity at specific time points; preserves intracellular metabolite labeling patterns | Typically cold organic solvents (e.g., methanol-based); must ensure rapid cooling and minimal leakage |

| Extraction solvents | Release intracellular metabolites from cells while maintaining labeling integrity | Combinations of chloroform, methanol, water; optimized for different metabolite classes |

| Mass spectrometry standards | Internal standards for quantification and instrument calibration | Stable isotope-labeled internal standards for absolute quantification |

Computational Protocol

Step 1: Define the Metabolic Network and Atom Transitions

Begin by compiling a comprehensive list of all metabolic reactions to be included in your model. For each reaction, specify the exact atomic mapping between substrates and products. This atom transition information is fundamental to the EMU framework, as it defines how labeling patterns are transformed by each biochemical conversion [1].

Detailed Methodology:

- Create reaction list: Document all metabolic reactions relevant to your system, including central carbon metabolism, biosynthetic pathways, and transport processes.

- Specify atom transitions: For each reaction, define the precise carbon (and other atom, if applicable) mapping from reactants to products. For example, for the condensation of OAA and AcCoA to citrate:

- Citrate C1, C2 ↠AcCoA C1, C2

- Citrate C3, C4, C5, C6 ↠OAA C1, C2, C3, C4

- Verify network consistency: Ensure all reactions are elementally and charge balanced.

- Document in machine-readable format: Prepare the metabolic network definition in a structured format compatible with your chosen modeling software (e.g., spreadsheet format for OpenFLUX [23]).

Step 2: Identify Target Metabolites for Simulation

Determine which metabolite labeling patterns need to be simulated based on your experimental measurements. This targeted approach is key to the efficiency of the EMU framework, as it focuses computational resources only on the necessary portions of the network [1] [4].

Implementation Guide:

- List measurable metabolites: Identify metabolites for which you have or will obtain experimental labeling data (e.g., via GC-MS).

- Specify atom subsets: For each target metabolite, define the specific EMU(s) that correspond to your measurement capabilities. For mass spectrometry, this typically involves the entire carbon skeleton; for NMR, specific carbon positions may be targeted separately.

- Prioritize by information content: Focus on metabolites that provide the greatest discrimination power for fluxes of interest.

Step 3: Perform EMU Decomposition

Execute the core EMU decomposition algorithm to identify the minimal set of EMU variables required to simulate the target labeling patterns. This step systematically traces backward through the metabolic network to find all precursor EMUs that contribute to the target EMUs [1] [4].

Diagram 1: EMU Decomposition Workflow - This flowchart illustrates the iterative process of identifying the minimal set of EMUs required to simulate target labeling patterns.

Technical Execution: The EMU decomposition can be implemented using the adjacency matrix approach as implemented in EMUlator [4] [11]:

- Construct Metabolite Adjacency Matrix (MAM): Create a square matrix where rows and columns represent metabolites, and elements indicate connecting reactions.

- Build EMU Adjacency Matrices (EAM): For each EMU size (starting with the largest target), create matrices that track how EMUs are connected through reactions.

- Iterative backward tracing: For each target EMU, trace backward through the EAMs to identify all precursor EMUs of smaller sizes.

- Continue until substrates are reached: The decomposition is complete when all EMUs can be traced back to labeled substrate EMUs.

Step 4: Generate EMU Balance Equations

Formulate mathematical equations that describe the relationship between EMUs based on metabolic fluxes and reaction stoichiometry. These equations form the core mathematical model that will be simulated [1].

Equation Formulation:

- For unimolecular reactions: The product EMU equals the reactant EMU scaled by the reaction flux.

- Example: A123 → B123: v * A123 = v * B123

- For condensation reactions: The product EMU is the convolution of the reactant EMUs scaled by the reaction flux.

- Example: A12 + B3 → C123: v * (A12 × B3) = v * C123

- For cleavage reactions: The product EMU equals the corresponding portion of the reactant EMU.

- Account for all contributing reactions: For each EMU, sum all producing and consuming fluxes to create the complete balance equation.

Step 5: Implement the EMU Model in Computational Software

Translate the EMU balance equations into a computational model using specialized MFA software. This step transforms the mathematical framework into an executable simulation [23] [4].

Implementation Options:

- Using OpenFLUX: Input the metabolic network definition via spreadsheet template; the software automatically generates the EMU balance model and MATLAB code [23].

- Using EMUlator: Utilize the Python-based adjacency matrix approach to build the EMU model programmatically [4].

- Custom implementation: Develop specialized code for unique applications, following the EMU framework principles [1].

Step 6: Simulate Labeling Patterns and Estimate Fluxes

With the EMU model implemented, simulate the expected labeling patterns for a given set of metabolic fluxes and compare these simulations with experimental data to estimate the most likely flux values [1] [23].

Flux Estimation Procedure:

- Initial flux guess: Start with an initial estimate of metabolic fluxes, often based on stoichiometric constraints or literature values.

- Forward simulation: Use the EMU model to simulate the expected mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) for the current flux values.

- Compare with experimental data: Calculate the difference between simulated and measured MIDs.

- Iterative optimization: Adjust flux values to minimize the difference between simulated and experimental data using nonlinear least-squares algorithms.

- Statistical evaluation: Assess the goodness of fit and calculate confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes.

Diagram 2: Flux Estimation Process - This workflow shows the iterative process of fitting metabolic fluxes to experimental labeling data using the EMU model.

Application Example: Analysis of Gluconeogenesis Pathway

To illustrate the power of the EMU framework, consider its application to the gluconeogenesis pathway with multiple isotopic tracers (2H, 13C, and 18O). Where traditional isotopomer methods would require simulating more than 2 million isotopomers, the EMU framework achieves equivalent results with only 354 EMUs—a reduction of four orders of magnitude in computational complexity [1] [2].

Implementation Details:

- Network definition: Include all reactions of gluconeogenesis from various precursors to glucose.

- Tracer design: Strategically select multiple isotopic tracers to maximize flux resolution.

- EMU decomposition: Identify the minimal set of EMUs needed to simulate the glucose labeling pattern.

- Flux estimation: Determine the fluxes through parallel and cyclic pathways in gluconeogenesis.

This example demonstrates how the EMU framework enables complex metabolic studies that would be computationally prohibitive with traditional methods.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Challenges and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for EMU-Based Metabolic Modeling

| Challenge | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor flux identifiability | Insufficient labeling information; redundant pathways | Use multiple tracers; design optimal tracer experiments [22] |

| Slow simulation | Inefficient EMU decomposition; unnecessary large EMUs | Verify decomposition algorithm; check for redundant EMUs |

| Optimization convergence issues | Poor initial guess; model overparameterization | Use sequential quadratic programming; reduce free flux parameters |

| Discrepancy between simulated and measured MIDs | Incorrect atom mappings; missing reactions | Verify all atom transitions; check network completeness |

Performance Optimization Strategies

- Lump unimolecular reactions: Combine sequential unimolecular reactions to reduce model size without affecting simulation accuracy [4].

- Identify equivalent EMUs: Recognize and combine rotationally symmetric EMUs to further reduce variables [11].

- Use appropriate software: Select computational tools that efficiently implement the EMU framework, such as OpenFLUX for user-friendly application or EMUlator for flexible, Python-based implementation [23] [4].