Unlocking Cellular Factories: A Guide to Metabolic Flux Analysis for Identifying Pathway Bottlenecks

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to identify critical bottlenecks in metabolic pathways.

Unlocking Cellular Factories: A Guide to Metabolic Flux Analysis for Identifying Pathway Bottlenecks

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to identify critical bottlenecks in metabolic pathways. We cover the foundational principles of MFA, explore core methodologies like 13C-MFA and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with their practical applications in strain engineering and biomedical research, address troubleshooting and optimization strategies for complex networks, and detail validation and comparative analysis techniques to ensure robust, reliable flux maps. By synthesizing these areas, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to systematically overcome metabolic limitations and enhance bioproduction or understand disease states.

The Fundamentals of Metabolic Flux Analysis: From Static Snapshots to Dynamic Network Insights

Core FAQ: Understanding Metabolic Flux Analysis

What is Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA)? Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) is an experimental technique used to examine the production and consumption rates of metabolites in a biological system. It quantifies metabolic fluxes—the rates at which molecules flow through biochemical pathways—thereby elucidating the central metabolism of the cell [1]. In essence, it provides a quantitative map of the dynamic activities within a metabolic network [2].

What is the core principle of MFA? The core principle of MFA is the precise quantification of in vivo reaction rates within a living organism. This is predicated on the fundamental understanding that biological compounds are in a "steady state of rapid flux," meaning they are constantly turning over through synthesis, breakdown, and conversion [3]. MFA quantifies these dynamics, moving beyond static "snapshot" measurements to capture the functional metabolic phenotype [3] [4].

Why is quantifying fluxes more informative than measuring static concentrations? A change in a metabolite's pool size (concentration) can result from an imbalance between its rate of appearance (synthesis) and its rate of disappearance (breakdown or conversion) [3]. Measuring the concentration alone does not reveal the underlying kinetics. Two systems can have identical metabolite pool sizes but vastly different turnover rates, which can affect the system's functional quality and responsiveness [3]. Fluxes provide a direct readout of cellular activity and phenotype.

How does MFA help identify bottlenecks in metabolic engineering? By directly quantifying the flow of carbon through interconnected pathways, MFA can pinpoint bottleneck enzymes—rate-limiting reactions that restrict the productivity of a biosynthetic pathway [1] [4]. For instance, Thermodynamics-Based MFA (TMFA) can identify thermodynamic bottleneck reactions by calculating the Gibbs free energies of reactions within a metabolic network [1]. Identifying these bottlenecks is crucial for guiding targeted engineering efforts to enhance the production of desired compounds, such as biofuels or pharmaceuticals [1] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

The following table outlines common challenges researchers face during MFA experiments and evidence-based solutions.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Design | Uninformative labeling data [5] | Poor choice of tracer; lack of prior flux knowledge for the organism. | Use Robustified Experimental Design (R-ED) workflows that evaluate tracer performance across a wide range of possible fluxes, rather than relying on a single flux guess [5]. |

| Difficulty reaching isotopic steady state [2] | Slow metabolic turnover (e.g., in mammalian cells); long experiment duration. | Employ Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) to measure transient labeling patterns before isotopic steady state is reached [1] [2]. | |

| Data & Modeling | Poor fit between model and data [6] | Model error (incomplete/incorrect network); measurement error. | Perform statistical validation (e.g., t-test) on calculated fluxes to distinguish measurement error from model error. A lack of significance indicates poor model fit [6]. |

| Intracellular fluxes are underdetermined [7] [4] | Fewer measured extracellular rates than unknown intracellular fluxes. | Incorporate 13C-labeling data from tracer experiments to provide additional constraints and resolve parallel, cyclic, and reversible pathways [1] [7]. | |

| Analytical | Low sensitivity for metabolite detection [8] | Limited sample volume; low abundance of key metabolites. | Leverage advancements in mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) that have significantly reduced sample volume requirements and expanded the measurable metabolome [8]. |

Workflow for Diagnosing Model Fit Problems

The logic flow below outlines a systematic approach to troubleshoot poor model fit, based on statistical methods [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in MFA | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Serve as the source of isotopic label that is incorporated into the metabolic network, enabling the tracing of carbon fate. | [1,2-13C]glucose; [U-13C]glucose; 13C-CO2; 13C-NaHCO3 [2] [5]. The choice of tracer is critical for information gain. |

| Quenching Solution | Rapidly halts cellular metabolism at the time of sampling to preserve the in vivo metabolic state. | Methanol, often combined with water for metabolite extraction [1]. |

| Analytical Standards | Used for instrument calibration and accurate quantification of metabolite concentrations and isotopic enrichment. | Unlabeled and uniformly labeled (13C) versions of target metabolites. |

| Software for 13C-MFA | Computational platforms used for simulation, flux calculation, and statistical analysis of labeling data. | 13CFLUX2 [1] [5], OpenFLUX [1], INCA (for INST-MFA) [1] [8]. |

Standard 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow

A typical Isotopically Stationary 13C-MFA procedure involves several key stages, from cell culture to flux calculation [1] [2].

Key Methodological Insights for Bottleneck Identification

- Go Beyond Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): While FBA is useful for predicting theoretical capabilities, its predictions are not always consistent with fluxes measured by 13C-MFA, especially for engineered strains [7]. For reliable bottleneck identification, empirical flux quantification via 13C-MFA is superior.

- Leverage INST-MFA for Complex Systems: For systems where reaching isotopic steady state is impractical (e.g., slow-growing cells, mammalian cells), INST-MFA is a powerful alternative that analyzes transient labeling patterns [1] [2].

- Validate Your Model: Always assess the goodness-of-fit between your metabolic model and the experimental data. Use available statistical methods to ensure your flux map is a reliable representation of the underlying biology before investing in engineering strategies based on its predictions [6].

FAQ 1: Why doesn't the presence of an enzyme guarantee high metabolic activity or product yield?

A high enzyme concentration does not automatically result in high flux through a metabolic pathway. The catalytic activity of an enzyme is the critical factor, which can be limited by several mechanisms:

- Thermodynamic Constraints: A reaction might be thermodynamically unfavorable in the physiological direction, preventing flux even if the enzyme is abundant [9].

- Enzyme Kinetics: An enzyme may have naturally low catalytic efficiency (low

kcat/KM) for its substrate, making it a slow step in the pathway [10]. - Cofactor/Limiting Substrate Availability: The reaction might be limited by the supply of essential cofactors (e.g., NADH, ATP) or a specific substrate, which restricts the enzyme's operational capacity [11].

- Post-Translational Regulation: The enzyme's activity could be inhibited or activated by other molecules, or through structural modifications, meaning its presence does not reflect its functional state [12].

- Gene Epistasis (Inter-enzyme Interactions): The performance of a specific enzyme can be enhanced or suppressed by the expression levels and activities of other enzymes in the same pathway, a phenomenon known as gene epistasis. An enzyme that is highly active in one genetic background may become a bottleneck when placed in a different background [13].

FAQ 2: What is gene epistasis and how does it create bottlenecks?

Gene epistasis in metabolism refers to a context where the effect of a mutation in one gene (e.g., a beneficial mutation that increases an enzyme's activity) depends on the genetic background, specifically the alleles present in other genes within the pathway [13].

- How it Creates Bottlenecks: A beneficial mutation that optimizes one enzyme might inadvertently cause another enzyme in the pathway to become the new rate-limiting step. For instance, research on a naringenin production pathway showed that beneficial TAL enzyme mutants were masked when expressed in a high-copy plasmid background because other enzymes (4CL and CHS) became the new bottlenecks. The "best" enzyme variant is not absolute but depends on its interaction partners in the pathway [13].

- Solution: To overcome this, researchers can use automated platforms to evolve multiple pathway enzymes synchronously under controlled, low-expression backgrounds. This "debugs" the pathway by creating clear evolutionary trajectories for each enzyme, preventing the masking of beneficial mutations and ensuring all steps are optimized in concert [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating Metabolic Bottlenecks

| Problem Scenario | Possible Underlying Cause | Recommended Experimental Approach | Key Technique Explained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low product yield despite high pathway enzyme expression. | Thermodynamic infeasibility or inefficient enzyme usage. | Use a framework like ET-OptME that layers enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic constraints onto metabolic models. | ET-OptME is a computational algorithm that integrates enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) and reaction thermodynamics into genome-scale metabolic models. It outperforms traditional stoichiometric methods by predicting more physiologically realistic intervention strategies, significantly improving prediction accuracy and precision [9]. |

| Cell growth impairment upon introducing a new metabolic pathway. | Insufficient energy (ATP) or reducing power (NADPH) due to an imbalance in the pathway. | Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) on a genome-scale model to identify energy depletion. | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based modeling approach that uses an organism's genome-scale metabolic network to predict metabolic flux distributions. It assumes steady-state mass balance and uses linear programming to optimize an objective (e.g., biomass growth). FBA can pinpoint reactions whose low flux disrupts energy metabolism [10]. |

| Unknown rate-limiting step in a central metabolic pathway. | Lack of quantitative data on in vivo metabolic flux distribution. | Conduct 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). | 13C-MFA is an experimental technique that uses 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose) to trace the fate of carbon atoms through metabolic networks. The incorporation of 13C into proteinogenic amino acids or other metabolites is measured by GC-MS or LC-MS. Computational modeling of this isotope labeling data allows for the precise quantification of in vivo metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) in central carbon metabolism [11]. |

| Difficulty predicting optimal enzyme expression levels to maximize flux. | Complex gene epistasis effects between multiple pathway enzymes. | Combine automated high-throughput screening with machine learning. | ProEnsemble Machine Learning Framework: This approach involves building a library of genetic constructs with varying expression levels of pathway enzymes (e.g., using different promoters). A machine learning model (ProEnsemble) is then trained on a balanced dataset of expression levels and product titers. The model learns to predict optimal expression combinations that minimize epistatic conflicts and maximize pathway efficiency, drastically reducing the experimental screening space [13]. |

Table 1: Quantitative Findings from Bottleneck Identification Studies

| Organism / System | Target Product | Analytical Method | Key Identified Bottleneck | Validation Strategy & Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli [10] | Glycolic Acid | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Insufficient activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase (AldA) | Replaced native E. coli AldA with a superior enzyme from Buttiauxella agrestis (BaAldA) with 1.49-fold higher kcat/KM. Result: 1.59x higher production. |

| Myceliophthora thermophila [11] | Malic Acid | 13C-MFA | Low flux through pyruvate carboxylation; low cytosolic NADH. | Increased cytoplasmic NADH via oxygen-limited culture and knockout of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT). Result: Enhanced malic acid accumulation. |

| E. coli [13] | Naringenin | Automated Screening & Machine Learning | Gene epistasis between TAL, 4CL, and CHS enzymes. | Used ProEnsemble model to predict optimal promoter combinations, overcoming epistasis. Result: Achieved 3.65 g/L naringenin in a bioreactor, the highest reported from tyrosine. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Metabolic Bottleneck Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., [U-13C] Glucose) | The tracer for 13C-MFA experiments. It allows for the measurement of intracellular metabolic fluxes by incorporating a measurable isotope pattern into metabolites [11] [14]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | A computational representation of an organism's metabolism. It serves as the foundation for constraint-based analyses like FBA and FVA to predict flux distributions and identify targets [10] [9]. |

| Enzyme Kinetics Assay Kits | Used to measure the catalytic efficiency (kcat, KM) of purified enzymes. This data is crucial for building enzyme-constrained models [10] [9]. |

| Automated Robotic Platform | Enables high-throughput construction of genetic variants and screening of thousands of clones, which is essential for debugging epistasis and generating data for machine learning [13]. |

| LC-MS / GC-MS Systems | The core analytical instrumentation for metabolomics and for measuring the mass isotope distributions needed for 13C-MFA [15] [11] [14]. |

| (25S)-3-oxocholest-4-en-26-oyl-CoA | (25S)-3-oxocholest-4-en-26-oyl-CoA, MF:C48H76N7O18P3S, MW:1164.1 g/mol |

| 6-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA | 6-hydroxyoctanoyl-CoA, MF:C29H50N7O18P3S, MW:909.7 g/mol |

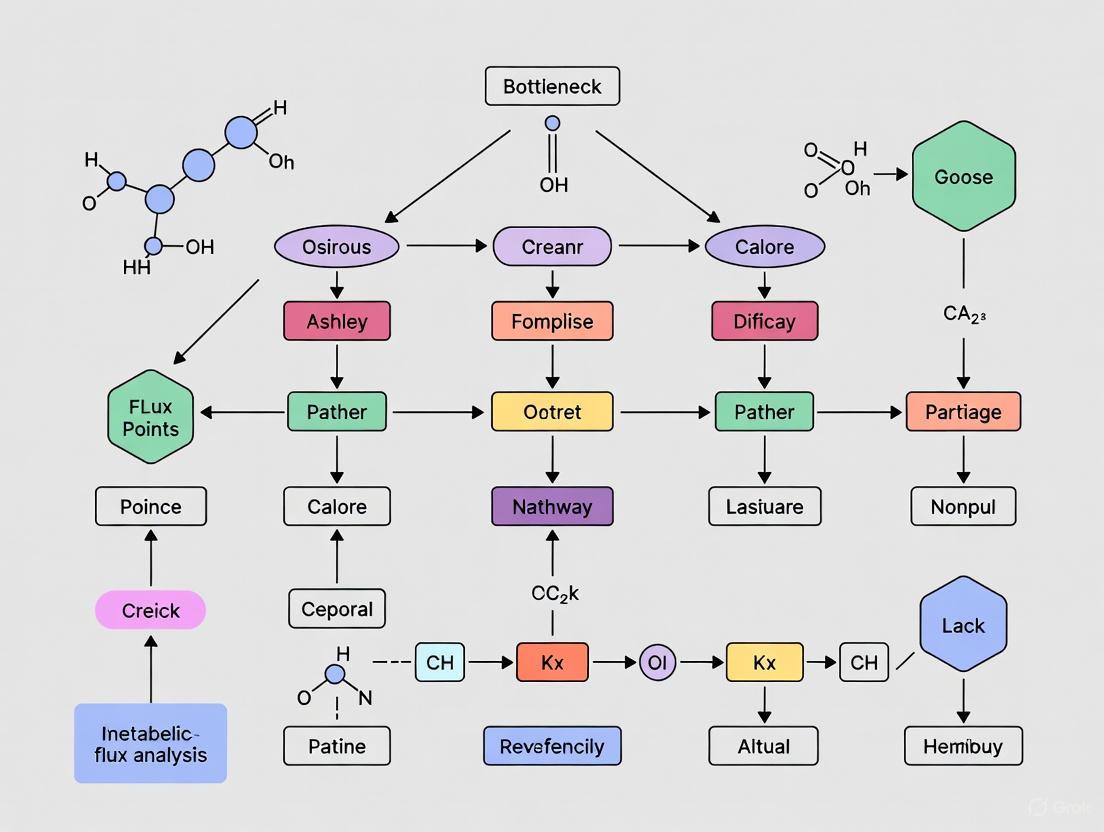

Experimental Pathway & Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate a key experimental workflow and a core metabolic concept related to identifying metabolic bottlenecks.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between 13C-MFA and FBA?

A1: The core difference lies in their methodologies and the type of data they use. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constraint-based, in silico modeling approach that uses the stoichiometry of a metabolic network and assumes a metabolic steady-state to predict optimal flux distributions, typically to maximize growth or product formation [2]. It does not require experimental measurement of intracellular fluxes. In contrast, 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is an experimental approach that uses stable isotope tracers (e.g., 13C-glucose) to measure in vivo metabolic fluxes [2] [16]. It tracks how these labeled atoms are incorporated into metabolites, providing an experimentally determined flux map.

Q2: My 13C-MFA experiment failed to provide precise flux estimates for key reactions. What could be the cause?

A2: Imprecise flux estimates, or non-identifiability, often stems from a suboptimal experimental design. The primary cause is frequently an ill-chosen tracer substrate [5]. For example, using [1-13C] glucose may not generate sufficient labeling information to resolve fluxes in the pentose phosphate pathway versus glycolysis. The solution is to perform in silico experimental design before wet-lab work. Tools like 13CFLUX2 can simulate different tracer mixtures (e.g., [U-13C] glucose, or mixtures of labeled and unlabeled substrates) to identify which one provides the most information for your pathways of interest, robustifying your design against uncertainties in prior flux knowledge [5].

Q3: When should I use Dynamic FBA instead of standard FBA?

A3: Use Dynamic FBA when your system is not at a metabolic steady-state. Standard FBA assumes constant extracellular concentrations and metabolic fluxes over time [2]. Dynamic FBA is necessary when you need to model transient conditions, such as batch bioreactor fermentations where nutrient levels deplete and by-products accumulate over time [2]. It works by dividing the culture period into discrete time steps and applying standard FBA at each step, updating the extracellular environment accordingly.

Q4: How can I visually communicate a complex flux map involving multiple pathways to my colleagues?

A4: Creating a clear multi-pathway diagram is crucial. Follow these principles:

- Optimize Flow: Arrange pathways in a logical, directional flow (e.g., left-to-right) to guide the viewer [17].

- Use Color Strategically: Apply high saturation and contrast to highlight key fluxes or pathways, like the "flowers" of your diagram, to draw immediate attention [17].

- Maintain Consistency: Use consistent lines and arrows for reactions, and group related elements closely (principle of proximity) to reduce clutter [17].

- Utilize Software: Tools like the Pathway Collage viewer in BioCyc or commercial illustration tools like BioRender can help assemble and style personalized multi-pathway diagrams effectively [18] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting FBA: "No Feasible Solution" Error

A "no feasible solution" error indicates that the linear programming solver cannot find a flux distribution that satisfies all model constraints.

| Step | Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Growth Medium | Verify that all essential nutrients for your model organism are present in the medium and that their uptake reactions are open. A missing essential nutrient (e.g., a carbon source, nitrogen, or phosphate) will make growth impossible. |

| 2 | Inspect Model Constraints | Review all reaction bounds for overly restrictive constraints. A common error is setting an irreversible reaction to carry a negative flux. Ensure lower bounds for irreversible reactions are set to zero. |

| 3 | Check Mass and Charge Balance | Imbalanced metabolic reactions can make the entire system infeasible. Use your modeling software's diagnostics tools (e.g., in COBRApy) to identify and correct reactions that do not conserve mass or charge. |

Troubleshooting 13C-MFA: Poor Fit Between Model and Labeling Data

A poor fit (high residual sum of squares) between the experimental labeling data and the model simulation suggests the inferred fluxes do not accurately represent the biological system.

| Step | Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Validate Isotopic Steady State | For 13C-MFA, ensure cells were harvested after reaching isotopic steady state. For mammalian cells, this can take 4 hours to a full day [2]. Premature harvesting will provide non-stationary data that 13C-MFA cannot accurately fit. |

| 2 | Verify the Metabolic Network | Check the model for incorrect or missing reactions, especially around branching points and cofactor usage. An incomplete network model is a common source of systematic error. |

| 3 | Confirm Tracer Purity and Measurement | Ensure the purity and composition of your labeled tracer substrate. Also, validate the accuracy of your mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements and data processing pipelines [2]. |

Troubleshooting Dynamic FBA: Unrealistic Metabolite or Flux Predictions

Dynamic FBA simulations can sometimes produce predictions where metabolite concentrations become negative or fluxes oscillate unrealistically.

| Step | Problem | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adjust Time Step Size | A time step that is too large can lead to numerical instability and unrealistic predictions. Reduce the size of the time step (Δt) in your simulation to improve accuracy. |

| 2 | Implement Dynamic Constraints | As substrates deplete, constrain their uptake rates to zero once the extracellular concentration hits zero. This prevents the model from unrealistically consuming non-existent nutrients. |

| 3 | Incorporate Regulatory Rules | Basic Dynamic FBA lacks transcriptional regulation. For more realistic predictions, consider using regulatory FBA (rFBA) if regulatory knowledge is available, to dynamically turn reactions on/off based on environmental cues. |

Comparative Analysis of MFA Approaches

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three MFA approaches to help you select the right method for your research objective.

Table 1: Comparison of Key MFA Techniques for Pathway Bottleneck Identification

| Feature | 13C-MFA | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Dynamic FBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Experimental measurement using 13C tracers [16] | In silico prediction using optimization [2] | In silico prediction across time [2] |

| Type of Data | Isotopic labeling (MS/NMR), extracellular rates [2] [19] | Stoichiometric model, growth/uptake rates [2] | Stoichiometric model, dynamic concentration changes |

| Steady-State Assumption | Metabolic & isotopic steady state (for 13C-MFA) [2] | Metabolic steady state only [2] | No steady-state (for extracellular metabolites) |

| Primary Application | Accurate measurement of in vivo fluxes in central metabolism [2] [19] | Hypothesis testing, predicting optimal yields, gene essentiality [2] | Simulating batch/transient processes, dynamic phenomena |

| Key Strength | High accuracy and resolution for core fluxes [16] | Fast, requires no experimental data beyond the model | Models complex, time-dependent bioprocesses |

| Main Limitation | Experimentally intensive, limited network scope [2] | Relies on optimization assumption (e.g., growth maximization) | Requires kinetic parameters for uptake/secretion |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: 13C-MFA for Mammalian Cells

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing a 13C-MFA experiment to identify metabolic bottlenecks in cultured mammalian cells, such as cancer cell lines [16].

1. Pre-culture and Steady-State Growth:

- Grow cells in standard medium until they reach a metabolic steady state, characterized by constant growth and metabolite consumption/production rates [2] [16].

- Quantify the growth rate (µ) and external rates (nutrient uptake and waste secretion) during this phase using cell counting and metabolite concentration assays (e.g., HPLC or enzymatic assays) [16]. Calculate rates using the formula for exponentially growing cells:

r_i = 1000 * µ * V * ΔC_i / ΔN_x, whereVis culture volume,ΔC_iis metabolite concentration change, andΔN_xis the change in cell number [16].

2. Tracer Experiment:

- Replace the standard medium with an identical medium where the carbon source (e.g., glucose) has been replaced by its 13C-labeled equivalent (e.g., [U-13C] glucose).

- Cultivate the cells for a sufficient duration to reach isotopic steady state, where the labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites no longer change. For mammalian cells, this can take 4 hours to a full day [2].

3. Metabolite Quenching and Extraction:

- Rapidly quench cellular metabolism instantly using cold methanol or similar cryogenic methods to "freeze" the metabolic state.

- Extract intracellular metabolites using a solvent system like methanol/water/chloroform.

4. Analysis of Isotopic Labeling:

- Analyze the extracted metabolites using Mass Spectrometry (MS) (most common) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to determine the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of key metabolic intermediates [2].

- The MID represents the fraction of a metabolite molecule that contains 0, 1, 2, ... 13C atoms.

5. Computational Flux Estimation:

- Use a metabolic network model of central carbon metabolism (glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle, etc.) with defined atom transitions.

- Input the measured external rates and MIDs into dedicated 13C-MFA software (e.g., INCA, 13CFLUX2) [2] [16] [5].

- The software will perform a non-linear regression to find the set of intracellular fluxes that best fits the experimental MID data.

Diagram 1: 13C-MFA experimental workflow.

Protocol: Implementing FBA with COBRApy

This protocol provides a basic workflow for performing FBA using the COBRApy package in Python to predict flux distributions in a genome-scale metabolic model [20] [21] [22].

1. Installation and Setup:

- Install COBRApy using pip (

pip install cobra) or conda (conda install -c conda-forge cobra) [20]. - In your Python script or Jupyter notebook, import the package:

import cobra

2. Load a Metabolic Model:

- Load a model in a standard format (e.g., SBML, JSON). For example:

model = cobra.io.read_sbml_model('your_model.xml')

3. Inspect the Model:

- Examine model components:

print("Reactions:", len(model.reactions))print("Metabolites:", len(model.metabolites))print("Genes:", len(model.genes))

4. Set Environmental Conditions:

- Constrain the uptake rates of nutrients to reflect your experimental conditions. For example, to set glucose uptake to 10 mmol/gDW/h and oxygen to 20 mmol/gDW/h:

model.reactions.EX_glc__D_e.bounds = (-10, 0)model.reactions.EX_o2_e.bounds = (-20, 1000)

5. Define the Objective Function:

- Set the biological objective the model will maximize (or minimize). The most common objective is biomass production:

model.objective = 'Biomass_Reaction'

6. Run FBA and Interpret Results:

- Perform the optimization:

solution = model.optimize() - Inspect the solution:

print("Growth Rate:", solution.objective_value)print(solution.fluxes)Usemodel.summary()to get an overview of input and output fluxes.

Diagram 2: FBA computational workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software for MFA

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracer | A substrate with carbon-13 atoms at specific positions; provides the "tracking signal" for 13C-MFA [2]. | [1,2-13C] Glucose, [U-13C] Glutamine. Choice is critical for information gain [5]. |

| Mass Spectrometer (MS) | Analytical instrument used to measure the mass isotopomer distribution (MID) of metabolites in 13C-MFA [2]. | GC-MS or LC-MS are most common. High resolution is preferred. |

| Metabolic Model | A stoichiometric matrix representing all metabolic reactions in the organism; the core of any FBA or 13C-MFA study. | Can be sourced from databases like BioModels, or reconstructed manually. |

| COBRApy | A Python package for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) of metabolic models [20] [21]. | Enables FBA, FVA, gene knockout simulations. |

| 13C-MFA Software | Specialized software to fit fluxes to isotopic labeling data. | INCA [16], 13CFLUX2 [5], OpenFLUX [2]. Often uses the EMU framework for efficiency [2] [16]. |

| Pathway Visualization Tool | Software to create clear, publication-quality diagrams of metabolic pathways and flux maps. | Pathway Collage [18], BioRender [17], Cytoscape [18]. |

| 3,5,7-Trioxododecanoyl-CoA | 3,5,7-Trioxododecanoyl-CoA, MF:C33H52N7O20P3S, MW:991.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| trans-19-methyleicos-2-enoyl-CoA | trans-19-methyleicos-2-enoyl-CoA, MF:C42H74N7O17P3S, MW:1074.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Critical Role of Stoichiometric Models and Mass Balance Constraints

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my stoichiometric model predicting unrealistic growth yields or infeasible metabolic fluxes? This often results from missing or incorrect mass balance constraints [23]. First, verify that the mass conservation principle is correctly applied to all metabolites in your network [23]. Second, check that you have implemented thermodynamic constraints to limit reaction directionality, as this reduces the solution space and prevents thermodynamically infeasible cycles [23]. Third, for more realistic predictions, consider applying an organism-level constraint, such as the total enzyme activity constraint, which limits the sum of enzyme concentrations based on the organism's physiological limitations [23].

Q2: How can I improve the accuracy of my model's predictions for genetic engineering targets? Integrate multiple constraint types. While stoichiometric models with mass balance are foundational, their predictive power is enhanced by incorporating homeostatic constraints (limiting internal metabolite concentration changes to physiologically plausible ranges) and experiment-level constraints (incorporating measured uptake/secretion rates) [23]. For finer resolution, complement your model with 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), which provides an experimental snapshot of in vivo metabolic flux distributions, allowing you to validate predictions and identify true bottlenecks [24].

Q3: My model has a feasible solution, but the engineered strain fails to produce the target compound. What could be wrong? The solution may be mathematically feasible but biologically inaccessible. Ensure your objective function (e.g., maximizing growth) reflects the true selective pressure. The model might lack regulatory constraints or not account for kinetic limitations in key reactions [23]. Furthermore, cytotoxic metabolite levels might be reached but are not constrained in your model [23]. Re-evaluate the model using dynamic FBA or by applying homeostatic constraints on metabolite concentrations to ensure the predicted flux distribution is sustainable for the cell [23].

Q4: What are the emerging computational methods that could help with large, complex models? For genome-scale models or multi-species communities where classical computations become intractable, quantum computing algorithms are being explored [25]. Early research shows that quantum interior-point methods can solve core metabolic-modeling problems like Flux Balance Analysis, potentially offering acceleration for problems with extremely large and sparse matrices, such as those in dynamic simulations or microbiome research [25]. However, this technology is still in its preliminary stages.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Infeasible Model Solution

Symptoms: Solver returns an "infeasible" error; no flux distribution satisfies all constraints.

Resolution Steps:

- Check Mass Balance: Systematically audit your stoichiometric matrix (S-matrix) to ensure every metabolite is mass-balanced [23].

- Verify Exchange Reactions: Confirm that all nutrients required for growth and production are provided in the media setup and can be taken up by the model.

- Loosen Bounds: Temporarily relax the upper and lower bounds on reaction fluxes to see if a solution appears, then identify the tight bound causing the issue.

- Inspect the Objective: Ensure your biomass objective function is correctly formulated and all necessary precursors can be produced.

Issue: Model Predictions Do Not Match Experimental Data

Symptoms: The model predicts high product yields, but lab results show low titers; or predicted growth rates are significantly higher than observed.

Resolution Steps:

- Apply Additional Constraints: Incorporate measured constraints, such as the ATP maintenance cost (ATPm) or the total enzyme activity constraint, to better reflect the organism's physiological limits [23].

- Integrate 13C-MFA Data: Use experimental flux data from 13C-MFA to constrain your model. For example, if 13C-MFA shows low flux through the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, you can constrain this flux in your model to recalculate more accurate predictions [26] [24].

- Validate Network Completeness: Check if all pathways essential for the observed phenotype are present in the model reconstruction. A missing transporter or an incomplete pathway can lead to incorrect predictions.

Issue: Poor Numerical Performance with Large-Scale Models

Symptoms: Long solver times, failure to converge, or out-of-memory errors.

Resolution Steps:

- Convert to Irreversible Model: Split reversible reactions into two irreversible steps, which can improve solver stability for some algorithms.

- Check Condition Number: Models with a high condition number can be unstable. Techniques like null-space projection, as explored in quantum algorithms for metabolic networks, can help reduce this value and improve accuracy and performance [25].

- Model Reduction: Employ network gap-filling to remove dead-end metabolites and reactions that cannot carry flux, reducing the problem size.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology for 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

Purpose: To quantitatively determine the in vivo flux distribution in a central metabolic network [26] [24].

Workflow:

- Tracer Experiment:

- Grow the organism (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Myceliophthora thermophila) in a defined medium where the carbon source (e.g., glucose) is replaced with a 13C-labeled version (e.g., [1-13C]glucose) [26] [24].

- Harvest cells during mid-exponential growth phase while metabolic steady-state is maintained.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Extract and derivatize proteinogenic amino acids from the biomass.

- Analyze the derivatized amino acids using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

- Measure the Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) of the amino acid fragments.

Flux Calculation:

- Use a stoichiometric model of the central metabolism.

- Employ computational software (e.g., INCA, OpenFLUX) to fit the simulated MIDs to the experimentally measured MIDs by iteratively adjusting the metabolic fluxes.

- The best-fit fluxes are those that minimize the difference between the simulated and experimental data.

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and data flow in a 13C-MFA workflow.

The table below summarizes key physiological and fluxomic findings from a 13C-MFA study on Saccharomyces cerevisiae in complex media, compared to a synthetic medium [26].

| Parameter / Organism | Synthetic Dextrose (SD) Medium | Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose (YPD) Complex Medium |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Sources Used | Glucose primarily | Glucose, Glutamic Acid, Glutamine, Aspartic Acid, Asparagine [26] |

| Key Flux Finding | Higher flux through anaplerotic pathways and oxidative PPP [26] | Reduced flux through anaplerotic and oxidative PPP pathways [26] |

| Physiological Outcome | More carbon loss via CO2 in branching pathways [26] | Elevated carbon flow toward ethanol production via glycolysis [26] |

Application in Troubleshooting: This data demonstrates how 13C-MFA can reveal fundamental shifts in pathway usage. If your engineered strain in a complex medium is not performing as predicted by a model built on synthetic media data, constraining your model with these flux observations can lead to more accurate design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions for foundational metabolic modeling and flux analysis experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates (e.g., [1-13C]Glucose) | Essential tracer for 13C-MFA experiments. The pattern of 13C incorporation into biomass components reveals in vivo metabolic fluxes [26] [24]. |

| Stoichiometric Model (e.g., Genome-Scale Reconstruction) | A mathematical representation of the metabolic network. Serves as the core framework for both Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C-MFA [23]. |

| Defined (Synthetic) Media | Media with a known, precise composition. Critical for performing controlled 13C-tracing experiments and for building accurate stoichiometric models with correct mass balance [26]. |

| Complex Media Components (e.g., Yeast Extract, Peptone) | Rich, undefined media used in industrial fermentations. Studying metabolism in these media requires 13C-MFA to account for parallel consumption of multiple carbon sources [26]. |

| Constraining Data (e.g., measured uptake/secretion rates) | Experimental data on nutrient consumption and product formation. Used to constrain the stoichiometric model, narrowing the solution space and improving prediction accuracy [23] [24]. |

| 11-Methyltridecanoyl-CoA | 11-Methyltridecanoyl-CoA, MF:C35H62N7O17P3S, MW:977.9 g/mol |

| Phthalimide-PEG1-amine | Phthalimide-PEG1-amine, MF:C12H14N2O4, MW:250.25 g/mol |

Core Pathway Visualization

The following diagram represents the central carbon metabolic pathways, highlighting key junctions where flux is often regulated and where bottlenecks can be identified using stoichiometric modeling and 13C-MFA [26] [24].

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) is a powerful technique that quantitatively describes the in vivo rates of biochemical reactions within metabolic networks. While other omics technologies provide static snapshots of cellular components—genomics reveals potential, transcriptomics shows expression, proteomics identifies enzyme presence, and metabolomics measures metabolite concentrations—only MFA captures the dynamic functional phenotype of the metabolic system [27]. This capability to quantify pathway activity makes MFA uniquely positioned to identify critical bottlenecks in metabolic pathways that limit the production of desired compounds, from pharmaceuticals to biofuels [24].

The fundamental principle of MFA is that it uses stable isotope tracers (most commonly 13C-labeled substrates) and mathematical modeling to infer intracellular metabolic fluxes [27]. Unlike direct metabolite concentration measurements, which represent a static pool size, fluxes represent the actual flow of metabolites through pathways, providing a direct readout of metabolic activity [27]. This dynamic information is crucial for metabolic engineering and drug discovery, as it reveals which pathway steps truly control flux toward a target metabolite.

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies and Their Limitations in Capturing Metabolic Activity

| Technology | What It Measures | Limitations for Metabolic Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence and structural variations | Reveals potential, not actual metabolic activity |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression levels | Poor correlation with metabolic flux rates |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance and modifications | Does not reflect enzyme activity or metabolic throughput |

| Metabolomics | Metabolite pool concentrations | Cannot distinguish between production and consumption rates |

| MFA | Metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) | Provides direct measurement of pathway activity |

Technical Foundations: How MFA Works

Core Principles and Methodologies

MFA operates on the principle that in tracer experiments, the isotope labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites are determined by the fluxes through metabolic pathways [27]. By measuring these labeling patterns with techniques like Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), and applying computational modeling, researchers can infer the metabolic fluxes [27]. Under metabolic and isotopic steady state, the labeling pattern of a metabolite is the flux-weighted average of the labeling patterns of its substrates [27].

The most common MFA approaches include:

- Steady-State 13C-MFA: The gold standard method where cells are cultivated with 13C-labeled substrates until both metabolic and isotopic steady state are reached [27].

- Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA): Used for systems where achieving steady state is impractical, such as photosynthetic organisms [28]. INST-MFA has been applied to map metabolic fluxes in Arabidopsis leaves and Camelina sativa [28].

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A constraint-based approach that predicts flux distributions at steady state by optimizing an objective function, such as biomass production [28] [29]. FBA is particularly useful for genome-scale metabolic models [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Key MFA Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Best Suited For | Key Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State 13C-MFA | Fitting fluxes to isotopic steady-state labeling data | Microbial systems, mammalian cell cultures | 13CFLUX2, OpenFLUX, METRAN |

| INST-MFA | Fitting fluxes to transient isotopic labeling data | Photosynthetic organisms, tissue systems | INCA, OpenMebius |

| FBA | Optimization of flux distribution using stoichiometric constraints | Genome-scale models, hypothesis generation | COBRA toolbox, various GSM platforms |

Key Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core MFA workflow from experimental design to flux estimation:

Diagram 1: Core MFA Workflow

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MFA Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracing carbon fate through metabolic networks | Position of label (e.g., 1,2-13C2-glucose) determines information gain |

| Quenching Solution | Rapidly halts metabolism at sampling time | Must preserve metabolic state without damaging cell integrity |

| Metabolite Extraction Buffers | Extracts intracellular metabolites for analysis | Different protocols for polar vs. non-polar metabolites |

| Internal Standards | Corrects for analytical variation in MS/NMR | Isotopically labeled versions of target metabolites |

| Enzymes for Biomass Hydrolysis | Breaks down cellular macromolecules for analysis | 6M HCl for amino acid analysis; specific enzymes for other components |

| MS/NMR Reference Standards | Metabolite identification and quantification | Unlabeled chemical standards for retention time matching |

Frequently Asked Questions: MFA Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: How do I select the appropriate isotope tracer for my MFA experiment?

Answer: Tracer selection should be guided by the specific metabolic pathways you wish to probe. The fundamental principle is that MFA can distinguish the relative contributions of converging pathways only when these pathways produce substrates with different labeling patterns for the shared product [27]. For central carbon metabolism:

- [1,2-13C2]glucose is excellent for elucidating glycolysis, PPP, and TCA cycle fluxes, as it allows observation of reversibility in upper glycolysis through labeling patterns in fructose bisphosphate [27].

- Uniformly 13C-labeled substrates provide extensive labeling information but are more expensive.

- Multiple tracers may be necessary for complex systems. For example, in photosynthetic studies, 13CO2 labeling has been used to map fluxes in the Calvin-Benson cycle [28].

Answer: The most significant sources of error include:

- Inadequate biomass composition data: The biomass synthesis reaction significantly influences carbon flux distribution [24]. Always use organism-specific biomass composition data. For example, in M. thermophila, accurate amino acid composition of the dry biomass was essential for reliable flux analysis [24].

- Poor labeling steady state: For INST-MFA, insufficient time series data can lead to large confidence intervals. Ensure proper experimental design with sufficient time points.

- Network incompleteness: Missing reactions or pathways in your metabolic model will force fluxes through incorrect routes. Use genome annotation and biochemical literature to build comprehensive networks.

- Extracellular flux measurements: Inaccurate measurements of substrate uptake and product secretion rates propagate through the entire model. Use biological replicates and precise analytics.

FAQ 3: My MFA results show high statistical confidence intervals for key fluxes. How can I improve precision?

Answer: High confidence intervals typically indicate insufficient measurement information to precisely determine certain fluxes. Consider these approaches:

- Supplemental measurements: Incorporate additional extracellular flux data, such as nutrient uptake rates, byproduct secretion rates, and growth rates [24].

- Tracer combination: Use multiple complementary tracers to provide orthogonal labeling information. For example, in liver studies, both glutamine and lactate tracers revealed distinct TCA cycle flux patterns [30].

- Metabolite concentration data: INST-MFA can incorporate concentration measurements to improve flux precision.

- Reduce network complexity: Focus on the core metabolic network relevant to your research question to minimize underdetermination.

FAQ 4: How can I validate MFA-predicted flux bottlenecks experimentally?

Answer: MFA-predicted bottlenecks require experimental validation through genetic or environmental manipulations:

- Gene knockout/overexpression: Modify expression of enzymes identified as potential flux controllers. In M. thermophila, NNT gene knockout validated predictions about NADH levels affecting malic acid production [24].

- Enzyme assays: Measure in vitro enzyme activities to confirm capacity constraints.

- Environmental perturbations: Change culture conditions (e.g., oxygen limitation) to test model predictions. Oxygen-limited culture of M. thermophila increased malic acid accumulation as predicted by MFA [24].

- Correlate with other omics data: Check if transcriptomic or proteomic data support the identified bottlenecks.

FAQ 5: What software tools are available for MFA, and how do I choose?

Answer: Multiple software platforms exist with different strengths:

- INCA: Supports both steady-state and INST-MFA, with user-friendly interface [27].

- 13CFLUX2: Comprehensive platform compatible with multiple data types [27].

- OpenFLUX: Enables efficient flux estimation with options for experimental design [27].

- Metabolic Topography Mapper (MET-MAP): A deep-learning approach for spatial flux analysis, recently used to map liver and intestine metabolic gradients [30].

Selection criteria should include your experimental design (steady-state vs. instationary), computational expertise, and specific organism/system requirements.

Case Study: MFA for Malic Acid Production in Myceliophthora thermophila

A recent study exemplifies how MFA identifies metabolic bottlenecks for bioproduction optimization [24]. Researchers compared a high malic acid-producing strain (JG207) of M. thermophila to the wild type using 13C-MFA. The experimental protocol involved:

- Strain Cultivation: Both strains were cultured in minimal medium with 13C-labeled glucose as tracer.

- Physiological Characterization: Measured glucose uptake, oxygen consumption, CO2 evolution, and biomass formation rates.

- Isotope Labeling Measurement: Analyzed isotopic labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites using GC-MS.

- Flux Calculation: Used computational modeling to estimate metabolic fluxes.

Table 4: Physiological Parameters of M. thermophila Strains [24]

| Parameter | Wild Type | JG207 (High Producer) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Growth Rate (h-1) | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | No change |

| Glucose Uptake Rate (mmol/gDCW·h) | 3.03 ± 0.26 | 4.13 ± 0.41 | +36% |

| Malic Acid Production (mmol/gDCW·h) | Not detectable | 1.15 ± 0.31 | Significant |

| Oxygen Uptake Rate (mmol/gDCW·h) | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 5.69 ± 0.03 | -14% |

| Biomass Yield (Cmol/Cmol) | 0.592 ± 0.008 | 0.426 ± 0.012 | -28% |

The flux analysis revealed that JG207 had elevated flux through the EMP pathway and downstream TCA cycle, with reduced oxidative phosphorylation flux [24]. This redistribution provided more precursors and NADH for malic acid synthesis. Based on these findings, researchers implemented two successful interventions:

- Oxygen-limited culture to further increase NADH availability

- NNT gene knockout to modulate NADH/NADPH balance

Both strategies significantly enhanced malic acid production, validating the MFA-predicted bottleneck [24]. The following diagram illustrates the key metabolic engineering strategy informed by MFA:

Diagram 2: MFA-Driven Metabolic Engineering

Advanced Applications: Integrating MFA with Other Technologies

Spatial MFA and Single-Cell Applications

Recent advances enable MFA at spatial and single-cell resolutions. For example, MALDI imaging mass spectrometry combined with isotope tracing and deep learning (MET-MAP) has revealed spatial metabolic gradients in mouse liver and intestine [30]. This approach showed that over 90% of measured metabolites exhibited significant spatial concentration gradients along liver lobules and intestinal villi [30].

Machine Learning and MFA Integration

Emerging approaches like the Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN) integrate multi-omics data into genome-scale metabolic models to predict metabolic fluxes [31]. These hybrid models combine the strengths of mechanistic modeling (GEMs) and data-driven machine learning, offering improved prediction performance [31].

Dynamic Flux Analysis for Pathway Regulation

Dynamic MFA approaches can capture temporal changes in metabolism during growth, development, and environmental responses [28]. In plants, dynamic models have elucidated complex regulatory mechanisms in specialized metabolic pathways like monolignol biosynthesis [28].

Methodologies in Action: Applying 13C-MFA, FBA, and Advanced Frameworks to Real-World Problems

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do I choose the right 13C-tracer for my specific pathway of interest? The choice of tracer depends heavily on the metabolic pathways you wish to interrogate. Using multiple tracers in parallel experiments can dramatically improve flux resolution [32] [33]. For central carbon metabolism, well-studied glucose mixtures (e.g., 80% [1-13C] and 20% [U-13C] glucose) are often used to ensure high 13C abundance in various metabolites [34]. For specific pathways:

- To distinguish PDH vs. PC entry into TCA cycle: Use [U-13C6]-glucose. PDH-derived citrate will be [M+2], while PC-derived citrate will be [M+3] [35].

- To resolve oxidative vs. non-oxidative PPP flux: Use [1,2-13C2]-glucose. The ratio of [M+1] to [M+2] in downstream lactate reveals the flux split [35].

Q2: Why must I correct my mass spectrometry data, and how is it done? Mass spectrometers measure the isotopic distribution of entire molecules, which includes the natural abundance of heavy isotopes from other elements (e.g., 17O, 18O). This introduces error into the 13C-labeling data, especially for molecules containing many non-carbon atoms [36]. Correction is essential for accurate flux estimation. The process involves:

- Algorithmic Correction: Using software tools like IsoCor or AccuCor, or custom Python scripts to build a correction matrix that deconvolutes the measured mass isotopomer distribution (MID) and removes the natural isotope effects [36] [35].

- Pre-processing: This data correction is a mandatory pre-processing step before the MIDs are used for flux calculation in 13C-MFA software [36].

Q3: My model fit is poor. What are the common causes? A poor model fit (high sum of squared residuals, SSR) indicates a discrepancy between the simulated and measured labeling patterns. Common causes include:

- Incorrect Model Assumptions: The metabolic network model may be missing active reactions or contain incorrect atom transitions [32] [37].

- Non-Steady-State Metabolism: The core assumption of isotopic steady state may be violated. For rapidly changing systems, Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA) should be used instead [38] [37].

- Low-Quality Measurements: Errors in measuring external rates (uptake/secretion) or isotopic labeling can lead to poor fits [16]. Ensure cultures are in metabolic steady state (e.g., chemostat or mid-exponential phase in batch) [32].

Q4: How can 13C-MFA reliably identify a true metabolic bottleneck? A bottleneck is not just a highly expressed enzyme, but a reaction whose flux is inversely correlated with product formation and is a competitive drain on precursors. 13C-MFA identifies bottlenecks by:

- Comparative Flux Analysis: Quantifying fluxes in high- vs. low-producing strains. For example, in cyanobacteria, INST-MFA revealed that pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PPC) fluxes were inversely correlated with aldehyde production [38].

- Validation: Genetically manipulating the candidate bottleneck (e.g., knocking down PDH) and confirming improved product yield validates the finding [24] [38].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Common 13C-MFA Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions and Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Flux Resolution | Suboptimal tracer choice; insufficient labeling measurements [32] [33]. | - Use parallel labeling with tracer mixtures (e.g., [1,2-13C] and [1,6-13C] glucose) [32].- Expand measurements to proteinogenic amino acids, glycogen glucose, and RNA ribose [32]. |

| Low Signal-to-Noise in Labeling Data | Natural isotope abundance effects [36]; low cell density; metabolite degradation. | - Apply natural isotope correction algorithms [36] [35].- Ensure sufficient biomass for GC/LC-MS analysis.- Optimize sample quenching and extraction protocols. |

| Failure to Reach Isotopic Steady State | Slow metabolic turnover; incorrect culture duration. | - For batch cultures, sample during mid-exponential phase [32].- For continuous cultures, ensure >5 volume turnovers before sampling [32].- Use INST-MFA for non-steady-state systems [38]. |

| Inconsistent External Rate Data | Evaporation; glutamine degradation; non-exponential growth [16]. | - Perform control experiments without cells to correct for evaporation and abiotic degradation [16].- Calculate rates only during confirmed exponential growth. |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Standard Workflow for Steady-State 13C-MFA

The following protocol outlines the core steps for a steady-state 13C-MFA experiment, as established in the literature [32] [16] [34].

1. Design the Isotopic Labeling Experiment

- Select Tracers: Choose 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose, glutamine) based on the pathways of interest. Mixtures of tracers are often optimal for flux resolution [32] [33] [34].

- Culture Mode: Use a defined, minimal medium with the tracer as the sole carbon source. Chemostat cultures are ideal for steady state. For batch cultures, harvest cells during mid-exponential growth phase [32] [34].

2. Perform Cultivation and Measure External Rates

- Grow Cells: Cultivate cells in the 13C-medium, ensuring metabolic and isotopic steady state is achieved [34].

- Quantify Rates: Measure cell growth and the uptake/secretion rates of all key nutrients and products (e.g., glucose, lactate, ammonium). These external fluxes constrain the model [16]. Calculate specific rates using established formulas [16].

3. Measure Isotopic Labeling

- Sample and Quench: Rapidly collect and quench culture samples to halt metabolic activity.

- Derivatize and Analyze: Extract intracellular metabolites. Derivatize samples (e.g., for GC-MS) and analyze using mass spectrometry to obtain Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) for key metabolites, typically proteinogenic amino acids [32] [34].

- Correct Data: Apply natural isotope correction to the raw MID data [36].

4. Perform Flux Analysis

- Define Metabolic Model: Construct a stoichiometric model of the central metabolic network, including carbon atom transitions [32].

- Estimate Fluxes: Use software (e.g., INCA, Metran, 13CFLUX) to find the set of intracellular fluxes that best fit the measured MIDs and external rates [32] [39] [37].

- Statistical Analysis: Assess the goodness-of-fit (e.g., using χ² test) and calculate confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes to determine their precision [32].

Protocol for Identifying Metabolic Bottlenecks

This methodology is demonstrated in multiple successful case studies [24] [38] [39].

- Engineer and Cultivate Strains: Generate a high-producing strain (e.g., via genetic engineering) and compare it to a reference strain (e.g., wild-type) under controlled conditions.

- Conduct 13C-MFA: Perform the standard 13C-MFA workflow (as above) for both strains to quantify their metabolic flux distributions.

- Perform Comparative Flux Analysis: Identify reactions where flux differences correlate with product synthesis.

- Validate the Bottleneck: Genetically manipulate the candidate reaction(s) (e.g., overexpression, knockdown) in the producer strain. An improvement in product titer or yield confirms the bottleneck [24] [38].

Diagram 1: A systematic cycle for identifying and overcoming metabolic bottlenecks using 13C-MFA, illustrating an iterative metabolic engineering process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Item | Function/Role in 13C-MFA | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Serve as the metabolic probes to trace carbon fate. | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [1-13C]glutamine. Choice is critical for flux resolution [32] [33] [35]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | The primary tool for measuring isotopic labeling in metabolites. | GC-MS and LC-MS. GC-MS often requires derivatization; LC-MS is suitable for unstable metabolites [32] [34]. |

| MFA Software Platforms | Computational engines for flux calculation from labeling data. | INCA [39], Metran [16], 13CFLUX[v3] [37]. They implement algorithms (e.g., EMU) to solve the flux map. |

| Defined Culture Media | Ensures the 13C-tracer is the sole carbon source, preventing dilution of the label. | Minimal media with known composition. Chemically defined media is essential for accurate flux estimation [34]. |

| Natural Isotope Correction Software | Corrects raw mass spec data for naturally occurring heavy isotopes (e.g., 17O, 18O). | IsoCor, AccuCor, or custom Python scripts. This is a mandatory data pre-processing step [36] [35]. |

| Linoelaidyl methane sulfonate | Linoelaidyl methane sulfonate, MF:C19H36O3S, MW:344.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 11-methylnonadecanoyl-CoA | 11-methylnonadecanoyl-CoA, MF:C41H74N7O17P3S, MW:1062.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: The core 13C-MFA workflow, showing the progression from experimental design and tracer application through analytical measurement to computational flux estimation.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical approach for analyzing the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling researchers to predict organism behavior such as growth rates or the production of specific metabolites [40]. This constraint-based methodology operates without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, instead relying on the stoichiometry of metabolic reactions and physicochemical constraints to define a space of possible metabolic behaviors [40] [41]. Within metabolic engineering and drug development, FBA has become an indispensable tool for identifying pathway bottlenecks—points in metabolic networks where limited enzymatic activity or regulatory constraints restrict carbon flow toward desired products [42] [19]. By systematically quantifying how metabolic fluxes change under different genetic or environmental conditions, FBA provides a computational framework for diagnosing limitations and guiding targeted engineering strategies to optimize microbial cell factories for bioproduction [42] [43].

The fundamental principle underlying FBA is that metabolic networks operate under steady-state conditions, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, and within physico-chemical constraints that define allowable metabolic flux distributions [40] [41]. This approach is particularly valuable for bottleneck identification because it can predict how perturbations to the metabolic network (e.g., gene knockouts, enzyme overexpression) redistribute fluxes throughout the entire system, often revealing unanticipated limitations that emerge after initial modifications [42]. For researchers investigating disease mechanisms or developing antimicrobial strategies, FBA also enables the identification of essential genes and reactions that represent potential therapeutic targets [40] [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Isotopically Nonstationary Metabolic Flux Analysis (INST-MFA)?

FBA is a constraint-based modeling approach that uses stoichiometric models of metabolism and optimization principles to predict flux distributions without requiring experimental measurement of metabolic fluxes [40]. It assumes steady-state metabolism and identifies optimal flux distributions based on defined biological objectives (e.g., biomass maximization) [41]. In contrast, INST-MFA is an experimental approach that uses isotopic tracer experiments with (^{13}\mathrm{C}) or (^{15}\mathrm{N}) labels combined with mass spectrometry or NMR measurements to determine actual in vivo metabolic fluxes [42] [19]. While FBA provides predictions based on network structure, INST-MFA provides empirical measurements of metabolic activity, making it particularly valuable for validating FBA predictions or studying systems where regulatory mechanisms may prevent optimal metabolic function [42].

Q2: How can FBA specifically identify metabolic bottlenecks in engineered pathways?

FBA identifies metabolic bottlenecks by comparing flux distributions between different strain variants or growth conditions to pinpoint reactions that limit metabolic throughput [42]. For example, when engineering cyanobacteria for isobutyraldehyde production, researchers used FBA to analyze fluxes around the pyruvate node and discovered that pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PPC) competed strongly for pyruvate, creating a bottleneck that limited flux toward the desired product [42]. By calculating flux variability ranges or performing sensitivity analysis on objective functions, FBA can identify reactions where small changes in capacity produce large effects on product formation, indicating potential bottleneck locations [40] [41].

Q3: What are the most common causes of infeasible FBA solutions, and how can they be troubleshooted?

Infeasible FBA solutions typically occur when the constraints imposed on the model create a solution space with no possible flux distributions that satisfy all conditions simultaneously. Common causes include:

- Incorrect reaction directionality: Setting irreversible reactions to operate in thermodynamically infeasible directions [44]. Check and adjust reaction bounds using

changeRxnBoundsor similar functions in COBRA Toolbox. - Mass balance violations: Errors in the stoichiometric matrix where atoms are not conserved in metabolic reactions [40]. Verify stoichiometric coefficients for all reactions, particularly in custom-added pathways.

- Over-constrained exchange reactions: Setting nutrient uptake or product secretion rates that cannot support maintenance energy requirements [41]. Loosen bounds on exchange reactions and ensure carbon and energy sources are available.

- Network gaps: Missing reactions that create "dead-end" metabolites that can be produced but not consumed, or vice versa [40]. Use gap-filling algorithms to identify and correct network incompleteness.

Q4: What computational tools are available for implementing FBA, and which are best for beginners?

Several software tools are available for FBA, with varying levels of accessibility and computational requirements:

Table: Computational Tools for Flux Balance Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Features | Best For | Language/Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Comprehensive suite for constraint-based modeling [40] | Researchers with MATLAB experience [40] | MATLAB |

| openCOBRA | Open-source constraint-based reconstruction and analysis [44] | Python users seeking flexibility [44] | Python |

| MASS-Toolbox | General introduction to constraint-based modeling [44] | Beginners learning fundamental concepts [44] | Mathematica |

| Escher | Visualization of flux distributions on pathway maps [44] | Creating publication-quality flux maps [44] | Web-based |

For beginners, the COBRA Toolbox provides extensive documentation and tutorials using well-curated models of E. coli core metabolism, making it an excellent starting point despite requiring MATLAB [40]. The MASS-Toolbox offers a gentler introduction for those with Mathematica access [44].

Q5: How can I validate FBA predictions of metabolic bottlenecks experimentally?

Experimental validation of FBA-predicted bottlenecks typically involves:

- INST-MFA: Comparing predicted flux distributions with experimentally measured fluxes using (^{13}\mathrm{C}) isotopic tracing [42]

- Enzyme activity assays: Measuring in vitro activity of enzymes identified as potential bottlenecks

- Genetic manipulations: Testing bottleneck predictions by overexpressing identified enzymes and measuring product formation [42] [43]

- Cell-free systems: Using purified enzyme systems to directly test pathway capacity without cellular regulation [43]

For example, a study validating FBA-predicted bottlenecks in isobutyraldehyde production used INST-MFA to confirm that downregulation of PDH and PPC fluxes correlated with improved product formation, then genetically engineered these nodes to achieve significant titer improvements [42].

Troubleshooting Common FBA Implementation Issues

Problem 1: Inaccurate Growth or Product Yield Predictions

Symptoms: FBA predictions consistently overestimate or underestimate experimentally measured growth rates or product yields, particularly under conditions where the objective function should be appropriate.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect biomass composition: The biomass objective function may not accurately reflect the organism's actual biomass composition under the simulated conditions.

- Solution: Review literature for organism-specific biomass compositions in similar conditions and update the biomass reaction accordingly.

- Missing maintenance energy requirements: The model may not properly account for non-growth associated maintenance (ATPM) energy demands.

- Solution: Add or adjust the ATP maintenance reaction (ATPM) based on experimental measurements of substrate consumption during non-growth phases.

- Incomplete metabolic network: Gaps in the metabolic reconstruction may force unrealistic flux routes.

- Solution: Use gap-filling algorithms like ModelSEED or RAVEN Toolbox to identify and fill network gaps based on comparative genomics and experimental data.

Diagnostic Experiment: Compare FBA predictions across multiple carbon sources. Consistent overprediction across substrates suggests issues with the biomass objective function or maintenance energy requirements, while substrate-specific discrepancies may indicate pathway gaps or incorrect annotations.

Problem 2: Failure to Predict Known Auxotrophies or Lethal Mutations

Symptoms: The model fails to correctly predict growth defects when specific genes are knocked out in silico, indicating possible network incompleteness or incorrect constraint application.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Network redundancy: Alternative isozymes or bypass routes may compensate for the knocked-out reaction in the model but not in vivo.

- Solution: Review genetic evidence for isozyme functionality and add tissue- or condition-specific reaction constraints where appropriate.

- Incorrect gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations: The Boolean relationships connecting genes to reactions may be incomplete or inaccurate.

- Solution: Manually curate GPR associations using recent literature and databases like BiGG Models or MetaCyc.

- Missing thermodynamic constraints: The model may allow thermodynamically infeasible cyclic flux loops that bypass the knocked-out reaction.

- Solution: Apply thermodynamic constraints using methods like loopless FBA or implement energy balance analysis.

Diagnostic Experiment: Systematically test single gene knockout predictions against experimental essentiality data from databases like OGEE or EcoGene, focusing on discrepancies to guide model refinement.

Problem 3: Numerically Unstable Solutions or Solver Failures

Symptoms: Linear programming solvers fail to converge, return errors, or produce significantly different solutions with small changes to model parameters.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Numerically ill-conditioned stoichiometric matrix: Very large or very small stoichiometric coefficients can create numerical instability.

- Solution: Check for and normalize extreme coefficients, particularly in biomass and transport reactions.

- Reversible reactions with large flux ranges: Reactions that can operate in both directions with wide flux bounds can create solution space degeneracy.

- Solution: Implement parsimonious FBA (pFBA) to find the simplest flux distribution or use flux variability analysis to identify poorly constrained reactions [41].

- Solver-specific issues: Different linear programming solvers may have varying tolerances and algorithm implementations.

- Solution: Compare results across multiple solvers (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX, GLPK) when possible [44].

Diagnostic Experiment: Perform flux variability analysis to identify reactions with large flux ranges that may indicate network gaps or missing constraints, then systematically apply additional biological constraints to these reactions.

Experimental Protocols for FBA Validation

Protocol 1: INST-MFA for Experimental Flux Determination

Purpose: To experimentally measure metabolic fluxes for validating FBA predictions using isotopic labeling and mass spectrometry [42] [19].

Materials:

- (^{13}\mathrm{C})-labeled substrates (e.g., NaH(^{13}\mathrm{CO}_3) for photosynthetic organisms [42])

- Quenching solution (e.g., cold methanol or acetonitrile)

- Extraction solvents (methanol/chloroform/water for metabolite extraction)

- LC-MS or GC-MS system with appropriate analytical columns

- Software for INST-MFA data analysis (e.g., INCA, OpenFLUX)

Procedure:

- Grow cells in biologically relevant conditions until mid-exponential phase.

- Rapidly introduce the (^{13}\mathrm{C})-labeled tracer substrate to the culture.

- Collect samples at multiple time points (e.g., 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 minutes after tracer administration) to capture isotopic non-stationary dynamics [42].

- Immediately quench metabolism using cold methanol (-40°C) and extract intracellular metabolites.

- Derivatize metabolites if necessary for GC-MS analysis or analyze directly via LC-MS.

- Measure mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) for key metabolic intermediates.

- Use INST-MFA software to estimate metabolic fluxes that best fit the experimental MIDs and extracellular flux measurements.

- Compare INST-MFA determined fluxes with FBA predictions to validate or refine the model.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Ensure rapid sampling and quenching to accurately capture metabolic dynamics

- Include appropriate internal standards (e.g., norvaline) for quantification [42]

- Optimize MS parameters for specific metabolites of interest to maximize signal-to-noise ratios

Protocol 2: Cell-Free System Bottleneck Validation

Purpose: To directly test FBA-predicted pathway bottlenecks using cell-free expression systems that allow manipulation of individual pathway components [43].

Materials:

- Cell-free protein synthesis system (e.g., purified enzyme systems or crude cell lysates)

- DNA templates for pathway enzymes

- Metabolic intermediates for supplementation experiments

- Analytical methods for quantifying metabolites and products (HPLC, LC-MS)

- Equipment for maintaining optimal reaction conditions (temperature-controlled shakers)

Procedure:

- Prepare cell-free system according to established protocols for your organism of interest.

- Set up complete pathway reactions containing all necessary enzymes, cofactors, and substrates.

- Systematically supplement with potential bottleneck metabolites (e.g., phosphoenolpyruvate, ATP, acetyl-CoA) and measure product formation rates.

- Identify metabolites that significantly increase product formation when supplemented – these represent potential pathway bottlenecks.

- Validate bottlenecks by modulating enzyme concentrations through DNA template addition or direct protein supplementation.

- Correlate in vitro bottleneck identification with FBA predictions from genome-scale models.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Optimize cell-free reaction conditions (pH, ionic strength, energy regeneration systems)

- Include proper controls to account for non-enzymatic reactions or background metabolite levels

- Use the cell-free system to test proposed bottleneck solutions before implementing in whole cells [43]

Table: Key Reagents and Resources for FBA and Bottleneck Identification

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Example Sources/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | (^{13}\mathrm{C})-labeled substrates (glucose, bicarbonate) | Enables experimental flux measurement via INST-MFA [42] | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories |

| Analytical Instruments | LC-MS/MS systems with high mass accuracy | Quantifies isotopic labeling patterns and metabolite concentrations [45] | SCIEX, Thermo Fisher, Agilent |

| Cell-Free Systems | Purified enzymes or crude cell lysates | Enables direct manipulation of pathway components for bottleneck testing [43] | Custom preparation following published protocols |

| Software Tools | COBRA Toolbox, openCOBRA, INCA | Performs FBA calculations and INST-MFA flux estimation [40] [44] | Open-source or academic licenses |

| Metabolic Models | Genome-scale reconstructions (e.g., E. coli iJO1366) | Provides stoichiometric framework for FBA simulations [40] | BiGG Models database |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems, inducible promoters | Implements predicted bottleneck solutions in vivo [42] | Addgene, commercial suppliers |

Visual Guide to FBA Workflow and Bottleneck Identification

Diagram 1: FBA Workflow for Bottleneck Identification

Diagram Title: FBA workflow for identifying metabolic bottlenecks

Diagram 2: Metabolic Network with Bottleneck Identification

Diagram Title: Metabolic bottleneck at pyruvate node

Diagram 3: INST-MFA Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: INST-MFA workflow for experimental flux validation

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a powerful technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes, enabling researchers to identify critical bottlenecks that limit the production of valuable biochemicals [2] [16]. This case study examines how 13C-MFA was applied to engineer Myceliophthora thermophila as a cell factory for enhanced malic acid production [11] [46]. Malic acid, a C4 dicarboxylic acid, serves as a crucial platform chemical with extensive applications in food, beverage, agricultural, and pharmaceutical industries [11]. Through comparative flux analysis of a high-production strain versus wild-type, researchers identified key metabolic constraints and validated targeted engineering strategies that significantly improved malic acid yield [11] [46].

Experimental Physiology and Key Findings

Physiological Characterization of Strains

The high malic acid-producing strain M. thermophila JG207 was developed by engineering the wild-type (WT) strain with heterologous genes including a malate transporter (Aomae) and pyruvate carboxylase (Aopyc) from Aspergillus oryzae DSM1863 [11]. Physiological characterization during batch culture revealed significant differences between the engineered and wild-type strains, summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Physiological Parameters of Wild-Type and Engineered JG207 Strains [11]

| Physiological Parameter | Wild-Type Strain | Engineered JG207 | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Growth Rate | Baseline | No significant change | ~0% |

| Glucose Uptake Rate | Baseline | Increased | +36% |

| Biomass Yield | Baseline | Decreased | -30% |

| Oxygen Uptake Rate (qOâ‚‚) | Baseline | Decreased | Not specified |

| COâ‚‚ Evolution Rate (qCOâ‚‚) | Baseline | Increased | Not specified |

| Malic Acid Yield | Baseline | Increased | 18.6% (Cmol/Cmol) |

| Succinic Acid Yield | Baseline | Increased | 5.2% (Cmol/Cmol) |

Metabolic Flux Distribution Revealed by 13C-MFA

The 13C-MFA experiments provided quantitative insights into how metabolic fluxes were redistributed in the high-production strain. Metabolic fluxes were determined by fitting a metabolic model to experimental mass isotopomer distribution data from amino acids, with statistical validation using χ² tests [11]. The key findings from the flux analysis included: