A Comprehensive Comparison of Flux Balance Analysis Software for E. coli Metabolic Modeling

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone of constraint-based modeling, enabling the prediction of metabolic behavior in Escherichia coli, a key organism in biotechnology and biomedical research.

A Comprehensive Comparison of Flux Balance Analysis Software for E. coli Metabolic Modeling

Abstract

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone of constraint-based modeling, enabling the prediction of metabolic behavior in Escherichia coli, a key organism in biotechnology and biomedical research. This article provides a systematic comparison of FBA software tools, from foundational algorithms to advanced applications. It guides researchers through core principles, practical implementation workflows, and troubleshooting of common pitfalls like unrealistic flux predictions. By evaluating tool performance against experimental data and highlighting emerging integrations with machine learning, this resource empowers scientists to select the optimal computational framework for simulating E. coli metabolism, thereby accelerating strain design and drug development efforts.

Understanding FBA: Core Principles and E. coli Model Foundations

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a powerful constraint-based computational method for simulating metabolic networks without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data [1]. By applying mathematical constraints that represent biological and physical laws, FBA predicts the flow of metabolites through biochemical networks, enabling researchers to study organismal metabolism at genome scale [2]. The approach has found diverse applications in bioprocess engineering, drug target identification, and host-pathogen interaction studies [2].

The mathematical foundation of FBA rests on three key components: the stoichiometric matrix that encodes network structure, mass balance constraints that enforce steady-state conditions, and linear programming to identify optimal flux distributions based on biological objectives [1] [2]. This mathematical framework allows FBA to calculate metabolic fluxes rapidly, making it possible to simulate large metabolic networks with thousands of reactions in seconds on modern computers [2].

For researchers working with E. coli metabolic models, understanding this mathematical basis is essential for properly implementing simulations, interpreting results, and selecting appropriate software tools. The following sections detail each mathematical component and demonstrate how they integrate to form a complete FBA workflow.

The Stoichiometric Matrix: Encoding Metabolic Network Structure

The stoichiometric matrix (S) provides the fundamental mathematical representation of a metabolic network, capturing all chemical transformations in a structured format [1]. Each column in S represents a biochemical reaction, while each row corresponds to a metabolite. The entries in the matrix are stoichiometric coefficients indicating the quantity of each metabolite consumed (negative values) or produced (positive values) in each reaction [2].

Table 1: Structure of a Stoichiometric Matrix

| Matrix Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Rows | m metabolites (m1, m2, ..., mm) | Metabolic species in the network |

| Columns | n reactions (v1, v2, ..., vn) | Biochemical transformations |

| Matrix entries | Sij (stoichiometric coefficient) | Number of moles of metabolite i produced/consumed in reaction j |

In practice, stoichiometric matrices are typically sparse, meaning most entries are zero, as individual biochemical reactions involve only a small subset of the network's metabolites [1]. For E. coli models, the complexity ranges from compact representations like iCH360 (a manually curated medium-scale model of energy and biosynthesis metabolism) to comprehensive genome-scale reconstructions like iML1515 containing 1,877 metabolites and 2,712 reactions [3] [1].

Mass Balance Constraints: The Steady-State Assumption

The core constraint in FBA is the steady-state assumption, which posits that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time—the rate of metabolite production equals the rate of consumption [1] [2]. Mathematically, this is represented by the equation:

S · v = 0

where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the flux vector containing the reaction rates [2]. This equation formalizes the mass balance constraint, ensuring that for each metabolite in the network, the net sum of its production and consumption equals zero.

The steady-state assumption transforms the problem of modeling metabolic fluxes into a system of linear equations [4]. For metabolic networks, which typically have more reactions than metabolites (n > m), this system is underdetermined, meaning there are infinitely many flux distributions that satisfy the mass balance constraints [1]. Additional constraints are needed to identify biologically relevant solutions, which are implemented as inequality constraints bounding reaction fluxes:

lowerbound ≤ v ≤ upperbound

These bounds incorporate biological knowledge, such as reaction directionality (irreversible reactions have a lower bound of 0) and substrate uptake rates measured experimentally [1].

Figure 1: Mass Balance at Steady State. At metabolic steady state, the influx of metabolites to a pool equals the outflux, resulting in no net concentration change over time.

Linear Programming: Optimizing Biological Objectives

Flux Balance Analysis uses linear programming to identify a particular flux distribution from the space of possible solutions defined by the mass balance constraints [1]. This requires defining an objective function representing the biological goal of the organism, which is typically formulated as a linear combination of fluxes:

Z = c · v

where c is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective [1]. The most common objective is biomass production, representing cellular growth [2]. The complete linear programming problem for FBA can be stated as:

Maximize Z = c · v Subject to: S · v = 0 lowerbound ≤ v ≤ upperbound

Table 2: Common Objective Functions in FBA for E. coli Research

| Objective Function | Mathematical Form | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | Maximize vbiomass | Prediction of growth rates under different conditions |

| ATP Production | Maximize vATP | Study of energy metabolism |

| Product Yield | Maximize vproduct | Metabolic engineering for chemical production |

| Nutrient Efficiency | Minimize vsubstrate_uptake | Study of metabolic efficiency |

For E. coli studies, biomass maximization has shown remarkable predictive power, with FBA-predicted aerobic and anaerobic growth rates of 1.65 hr⁻¹ and 0.47 hr⁻¹, respectively, agreeing well with experimental measurements [1]. Advanced implementations may incorporate multiple objectives, such as in the TIObjFind framework, which uses Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) to quantify each reaction's contribution to composite objective functions derived from experimental data [5].

Experimental Protocols for FBA Implementation

Core FBA Protocol for E. coli Metabolic Models

The standard workflow for implementing FBA with E. coli metabolic models consists of the following methodological steps [1] [4]:

Model Acquisition and Validation: Obtain a curated metabolic model such as iCH360 (a compact model of E. coli core and biosynthetic metabolism) or iML1515 (a genome-scale reconstruction) [3]. Validate model functionality using quality control checks, such as ensuring the model cannot generate ATP without an energy source [6].

Constraint Definition: Set flux bounds based on environmental conditions. For example, when modeling aerobic growth with glucose limitation, set the glucose uptake rate to a physiologically realistic level (e.g., 18.5 mmol glucose gDW⁻¹ hr⁻¹) while allowing high oxygen uptake [1].

Objective Function Specification: Define the biological objective, typically biomass maximization for growth prediction. The biomass reaction converts precursor metabolites into biomass components at their appropriate stoichiometries [1].

Problem Formulation and Solution: Apply linear programming to solve the optimization problem using tools like the COBRA Toolbox or cobrapy [1] [6]. The simplex method is commonly used to identify the optimal flux distribution [4].

Solution Validation and Interpretation: Compare predictions with experimental data, such as measured growth rates or gene essentiality [6]. For E. coli, FBA successfully predicts approximately 90% of gene essentiality in rich media [1].

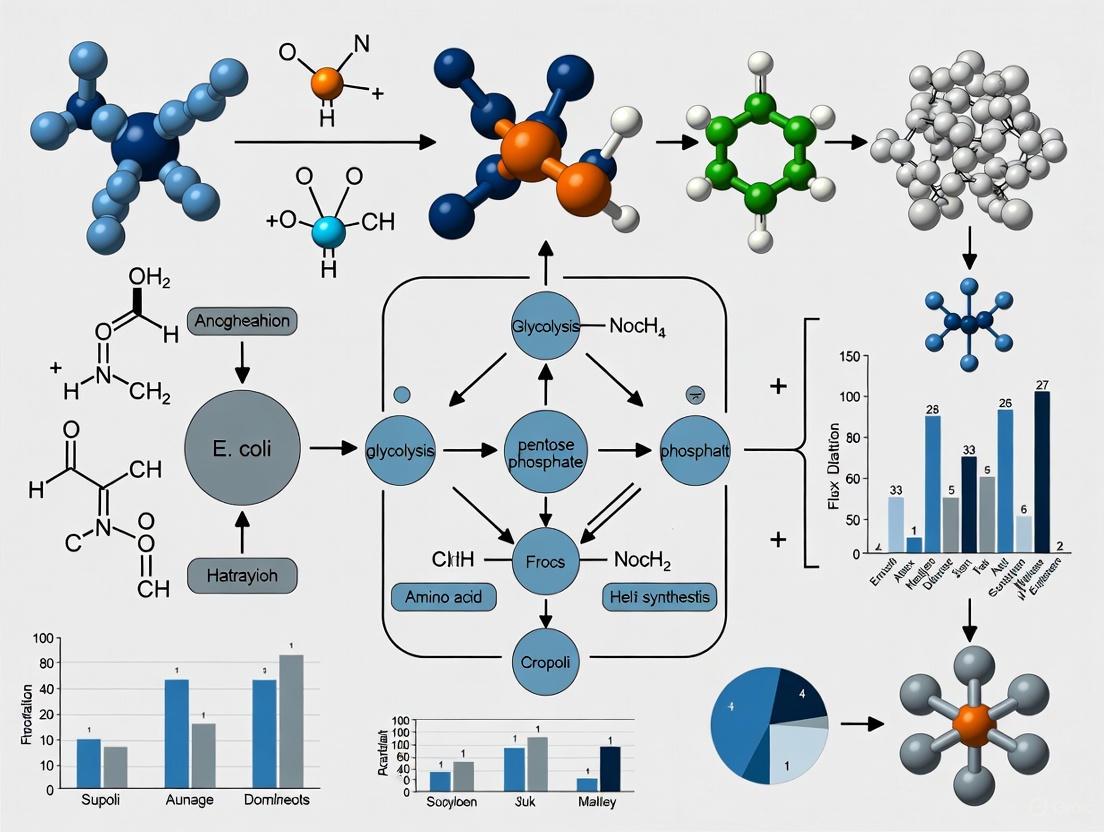

Figure 2: FBA Workflow. The standard implementation protocol for Flux Balance Analysis progresses from network representation through constraint definition to solution and analysis.

Advanced Implementation: Gene Deletion Studies

FBA can predict the phenotypic effects of genetic manipulations through gene deletion analysis [2]:

Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Mapping: Associate genes with reactions using Boolean expressions. For example, (GeneA AND GeneB) indicates a protein complex, while (GeneA OR GeneB) indicates isozymes [2].

Reaction Constraint Modification: For single gene deletions, set the flux through associated reactions to zero if the GPR expression evaluates to false after gene removal [2].

Phenotype Prediction: Solve the FBA problem with modified constraints and compare the objective value (e.g., biomass production) to the wild-type prediction [2].

Experimental Validation: Compare essentiality predictions with experimental results from knockout libraries [1]. For E. coli, FBA has been used to predict essential genes across various growth conditions with high accuracy [1].

Table 3: Key Resources for FBA Research with E. coli Models

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in FBA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Models | iCH360 (compact model), iML1515 (genome-scale) | Provide structured metabolic networks for E. coli simulations [3] |

| Software Tools | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), cobrapy (Python) | Implement FBA algorithms and related constraint-based methods [1] [6] |

| Model Databases | BiGG, MetaNetX | Offer standardized, curated metabolic models [7] |

| Quality Control Tools | MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) | Validate model stoichiometry and functionality [6] |

| Linear Programming Solvers | GLPK, Gurobi, CPLEX | Solve the optimization problems in FBA [7] |

Successful FBA implementation requires both computational tools and experimental validation. The COBRA Toolbox, which includes the E. coli core model, provides a comprehensive framework for performing FBA and related analyses [1]. For model reconstruction and curation, automated tools like CarveMe and ModelSEED enable rapid generation of metabolic models from genomic data [7]. When working with these resources, researchers should prioritize models with extensive biochemical validation, such as iCH360, which includes thermodynamic and kinetic constants in addition to standard stoichiometric data [3].

Comparative Analysis of FBA Approaches for E. coli Research

Table 4: Comparison of FBA Model Types for E. coli Metabolic Studies

| Model Characteristic | Core Models (e.g., iCH360) | Genome-Scale Models (e.g., iML1515) |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Count | ~100-400 reactions | ~2,000-3,000 reactions [3] [1] |

| Computational Demand | Low (seconds on personal computers) | Moderate (still rapid: seconds to minutes) [2] |

| Analysis Compatibility | Full EFM analysis, comprehensive sampling | Limited to FBA and related constraint-based methods [3] |

| Biological Coverage | Central metabolism, biosynthesis pathways | Full metabolic potential including degradation, cofactor synthesis [3] |

| Visualization Potential | Easily visualized metabolic maps | Challenging to visualize comprehensively [3] |

| Predictive Limitations | May miss alternative pathways | Can predict unrealistic metabolic bypasses [3] |

The selection between model types involves trade-offs between biological coverage and computational tractability. Compact models like iCH360 offer advantages for detailed analysis of central metabolic pathways and are more amenable to visualization and complex analytical methods like Elementary Flux Mode analysis [3]. Genome-scale models provide comprehensive coverage but may require additional constraints to eliminate physiologically irrelevant solutions [3]. Recent approaches like enzyme-constrained FBA incorporate kinetic and thermodynamic data to enhance prediction accuracy, addressing limitations of traditional FBA implementations [3].

Constraint-based metabolic modeling has become an indispensable tool for systems biologists and metabolic engineers. For the model organism Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655, decades of modeling efforts have produced models of varying scope and complexity [8]. Researchers must often choose between comprehensive genome-scale models (GEMs) like iML1515 and streamlined core models like the new iCH360, each with distinct advantages and limitations [9] [3] [10]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these modeling approaches, supported by experimental data and practical implementation protocols to inform researchers' tool selection.

Model Specifications and Comparative Analysis

Structural and Functional Composition

The table below compares the core architectural components of iML1515 and iCH360.

Table 1: Architectural Comparison of E. coli Metabolic Models

| Feature | iML1515 (GEM) | iCH360 (Compact Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Genes | 1,515 | 360 |

| Reactions | 2,712 | 323 |

| Metabolites | 1,877 | 304 (254 unique compounds) |

| Model Scope | Comprehensive cellular metabolism | Energy metabolism & biosynthetic precursors |

| Biosynthesis Coverage | Full biomass composition | Amino acids, nucleotides, fatty acids |

| Pathway Detail | Complete metabolic network | Central carbon metabolism, precursor synthesis |

| Visualization | Complex, multi-layer maps | Custom metabolic maps for core subsystems |

Performance and Predictive Capabilities

Quantitative assessment reveals significant differences in model performance under various conditions.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Metabolic Phenotype Prediction

| Analysis Type | iML1515 Performance | iCH360 Performance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Essentiality | 93.4% accuracy across 16 carbon sources [8] | Similar accuracy on shared reactions | Minimal media conditions |

| Growth Rate Prediction | Reference standard | Comparable yields on glucose | Maximum glucose uptake: 10 mmol/gDW/h |

| Acetate Production | Predicts unrealistically high fluxes [11] | Physiologically realistic fluxes | Production envelope analysis |

| Computational Demand | High (hours for complex simulations) | Low (minutes for most analyses) | EFM enumeration feasible |

| Byproduct Prediction | Comprehensive but may include unrealistic bypasses | More constrained, biologically realistic | Glucose to ethanol, lactate, succinate |

Experimental Protocols for Model Evaluation

Production Envelope Analysis

Purpose: To determine the trade-off between biomass production and metabolite synthesis under constrained substrate uptake.

Workflow:

- Set the glucose uptake rate to a fixed value (e.g., 10 mmol/gDW/h)

- Constrain oxygen uptake for aerobic/anaerobic conditions

- Maximize biomass production while sequentially constraining product secretion

- Calculate production yields (mol product/mol substrate)

Implementation:

Enzyme-Constrained Flux Balance Analysis (ecFBA)

Purpose: To incorporate proteomic limitations into flux predictions for more realistic simulations.

Methodology:

- Map enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) to corresponding reactions

- Add enzyme mass balance constraints

- Incorporate measured enzyme abundance data

- Optimize for growth within enzyme capacity limits

Application: The EC-iCH360 variant includes these constraints using the sMOMENT format, enabling more accurate predictions of metabolic behavior under enzyme-limited conditions [9] [12].

Diagram 1: ecFBA Workflow Integration

Visualization and Interpretation Framework

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting simulation results from both model types.

Metabolic Mapping with Escher

Tool: Escher-FBA web application [13] Function: Interactive flux visualization without programming requirements Implementation:

- Import models in COBRA JSON or SBML formats

- Visualize flux distributions directly on pathway maps

- Modify reaction bounds and objective functions interactively

- Generate publication-quality figures

Advantage for iCH360: The model includes custom Escher maps for all subsystems, enabling immediate visualization without additional configuration [14] [12].

Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) Analysis

Purpose: Identify all thermodynamically feasible, stoichiometrically balanced pathways Application: Particularly suitable for iCH360red (reduced variant) due to computational feasibility Workflow: Enumerate EFMs under different environmental conditions Output: Fundamental pathway analysis for metabolic engineering design

Diagram 2: EFM Analysis Pipeline

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for E. coli Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Type | Specific Tools | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Model Files | iCH360 (SBML/JSON), iML1515 (SBML) | Core simulation input |

| Visualization | Escher, custom subsystem maps | Pathway mapping and flux visualization |

| Analysis Toolboxes | COBRApy, COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based simulation |

| Data Integration | EcoCyc annotations, thermodynamic parameters | Model enhancement and validation |

| Specialized Variants | EC-iCH360 (enzyme-constrained), iCH360red (EFM analysis) | Advanced application-specific studies |

The choice between genome-scale (iML1515) and compact core (iCH360) E. coli metabolic models depends fundamentally on research objectives. iML1515 provides comprehensive coverage essential for genome-wide studies and discovery of novel metabolic functions, while iCH360 offers computational efficiency and biological realism for focused studies on central metabolism and pathway engineering. The experimental frameworks presented enable rigorous comparison of model performance, ensuring appropriate tool selection for specific research needs in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three primary software ecosystems for Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA)—COBRA Toolbox, COBRApy, and ModelSEED. Aimed at researchers conducting metabolic modeling, particularly with E. coli, this article compares their performance, technical foundations, and applicability through standardized criteria and a case study.

Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) has become a cornerstone methodology for studying metabolic networks in systems biology and metabolic engineering [15]. This approach uses genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate organism metabolism by applying physicochemical and biological constraints to predict feasible metabolic phenotypes [16]. The COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB, initially developed over a decade ago, established a standardized platform for implementing these methods, leading to widespread adoption in the microbial research community [15]. As the field evolved, new software ecosystems emerged to address different computational needs and research workflows.

COBRApy represents a significant evolution in the COBRA software landscape, designed as a Python-based package to overcome limitations of the original MATLAB implementation [16]. Its development was motivated by the need to accommodate more complex biological networks and integrate more efficiently with modern data science workflows and high-throughput omics data [17]. Meanwhile, ModelSEED offers a distinct approach focused specifically on the rapid reconstruction of draft metabolic models from genome annotations through an automated pipeline [18]. Understanding the relative strengths, performance characteristics, and optimal use cases for each ecosystem is essential for researchers to select the appropriate tool for their specific metabolic modeling projects, particularly when working with well-studied organisms like E. coli.

Comparative Analysis of Ecosystem Architectures and Capabilities

The three ecosystems differ significantly in their software architecture, dependencies, and core functionalities, which directly influences their application in research workflows.

Table 1: Core Architectural Comparison of COBRA Software Ecosystems

| Feature | COBRA Toolbox | COBRApy | ModelSEED |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Language | MATLAB | Python | Web-based API/Perl |

| License | GNU GPL/LGPL v2+ | GNU GPL/LGPL v2+ | Open Source |

| Key Dependency | MATLAB Runtime | Python Scientific Stack | RAST Annotation Server |

| Model Format | MATLAB structures | Object-oriented | JSON/SBML |

| Primary Strength | Comprehensive method library | Modern architecture & scalability | Rapid draft reconstruction |

| Ideal Use Case | Method development & education | High-throughput analysis & integration | High-throughput model building |

COBRA Toolbox: The Established Reference Platform

The COBRA Toolbox operates within the MATLAB environment and provides the most comprehensive collection of COBRA methods available [19]. Its extensive tutorial system covers everything from basic Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to advanced techniques like thermodynamically constrained modeling and host-microbiome interaction simulations [19] [20]. The toolbox continues active development, with recent versions (v3.6 as of 2023) adding enhancements for microbiome modeling, nutrition analysis, and improved visualization capabilities [21]. While requiring MATLAB licensing, it offers interfaces to high-performance solvers like Gurobi, CPLEX, and MOSEK [15], making it suitable for large-scale models. The object-oriented design of COBRApy more naturally represents complex biological relationships between genes, reactions, and metabolites compared to the table-based structure of the COBRA Toolbox [16].

COBRApy: The Modern Python Alternative

COBRApy implements an object-oriented architecture that directly represents biological entities as Python objects (Model, Reaction, Metabolite, Gene), creating a more intuitive interface for model manipulation and analysis [16]. This design facilitates the development of complex models that integrate multiple biological processes beyond core metabolism. A key advantage is its independence from commercial software, relying instead on the open-source Python scientific ecosystem (e.g., NumPy, SciPy, pandas) [16]. The package includes parallel processing support for computationally intensive operations like flux variability analysis and double gene deletion studies, significantly accelerating these analyses on multicore systems [16]. For researchers already working within the MATLAB ecosystem, COBRApy includes interfaces to the COBRA Toolbox via its cobra.mlab module, enabling use of legacy codes [16].

ModelSEED: Specialized Reconstruction Pipeline

ModelSEED employs a distinct approach focused specifically on the initial reconstruction phase of metabolic modeling. The pipeline begins with genome annotation via the RAST server, followed by automated inference of metabolic reactions, generation of biomass components, and gap-filling to ensure metabolic functionality [18]. This automated approach enables rapid development of draft models, though these typically require manual curation to achieve high quality, as evidenced by the 74% MEMOTE score reported for the manually curated Streptococcus suis model compared to initial automated reconstructions [18]. ModelSEED integrates with both COBRA Toolbox and COBRApy for subsequent analysis, as researchers typically export SBML models for constraint-based analysis in these environments [18].

Performance Comparison Through Experimental Data

To objectively compare the capabilities of these ecosystems for metabolic modeling research, we examine both quantitative performance metrics and qualitative factors across common research tasks.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Common Research Tasks

| Research Task | COBRA Toolbox | COBRApy | ModelSEED |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Reconstruction | Manual curation | Manual curation | Automated pipeline |

| Flux Balance Analysis | Comprehensive implementations | Core methods | Export to other tools |

| Gene Essentiality | Single/double deletions | Single/double deletions | Not primary function |

| Flux Variability | Efficient implementations | Parallel processing support | Not primary function |

| Gap Filling | Dedicated functions | Dedicated functions | Automated during reconstruction |

| Data Integration | Extensive omics integration | Python data science ecosystem | RAST annotation data |

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

For fundamental analyses like FBA, all three ecosystems produce mathematically equivalent results when properly configured, as they ultimately solve the same linear optimization problems. However, implementation differences affect performance and usability. COBRApy demonstrates advantages in computational efficiency for certain intensive operations, with its parallel processing capabilities for flux variability analysis and gene deletion studies providing significant speed improvements for large models [16]. Benchmarking tests on an E. coli core model showed COBRApy reduced computation time for double gene deletion analyses by approximately 40% compared to the COBRA Toolbox when utilizing multiple CPU cores [16].

ModelSEED's specialization in reconstruction makes direct performance comparisons for simulation tasks less relevant, as researchers typically export models to COBRApy or COBRA Toolbox environments for analysis [18]. The ModelSEED reconstruction pipeline itself is optimized for high-throughput processing of multiple genomes simultaneously, a capability not directly provided by the other ecosystems.

Case Study: Metabolic Model Reconstruction and Analysis

A recent study developing a genome-scale metabolic model for Streptococcus suis (iNX525) illustrates how these ecosystems can be integrated in a research workflow [18]. The reconstruction phase utilized ModelSEED to generate an initial draft model from genome annotations, which contained 392 genes, 988 metabolites, and 822 reactions [18]. Researchers then imported this draft model into the COBRA Toolbox for manual curation, gap filling, and validation [18]. The final curated model contained 525 genes, 708 metabolites, and 818 reactions, demonstrating the substantial refinement typically required after automated reconstruction [18].

For performance validation, the researchers used the COBRA Toolbox to simulate growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions and genetic perturbations [18]. The flux balance analysis predictions showed 71.6-79.6% agreement with experimental gene essentiality data from mutant screens, validating the model's predictive capability [18]. This case study exemplifies a hybrid approach leveraging the unique strengths of multiple ecosystems: ModelSEED for efficient initial reconstruction and COBRA Toolbox for rigorous curation and analysis.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow combining strengths of all three ecosystems

Experimental Protocols for Ecosystem Evaluation

To systematically evaluate and compare these ecosystems, researchers should implement standardized benchmarking protocols. Below we outline key experimental methodologies cited in the literature.

Growth Simulation and Gene Essentiality Protocol

The Streptococcus suis modeling study provides a representative protocol for validating metabolic model predictions [18]:

- Model Reconstruction: Create draft model from genome annotation using ModelSEED pipeline

- Manual Curation: Import draft into COBRA Toolbox or COBRApy for gap filling and mass/charge balance verification

- Biomass Definition: Define biomass composition equation based on experimental data or phylogenetically related organisms

- Constraint Configuration: Set medium constraints to reflect experimental conditions

- Growth Simulation: Perform FBA with biomass reaction as objective function

- Gene Essentiality: Simulate gene knockouts by setting associated reaction fluxes to zero

- Validation: Compare simulated growth rates and essential genes with experimental phenotypic data

This protocol achieved 71.6-79.6% agreement between simulated and experimental gene essentiality data when applied to S. suis [18], providing a benchmark for model quality assessment.

Flux Variability Analysis with Parallel Processing

For analyzing the flexibility of metabolic networks under different conditions:

- Model Loading: Load validated model in COBRApy or COBRA Toolbox

- Objective Constraint: Set objective function (e.g., biomass production) to near-optimal value (typically 90-99% of maximum)

- Solver Configuration: Select appropriate linear programming solver (Gurobi, CPLEX, or COIN-OR LP)

- Parallel Setup: In COBRApy, configure Parallel Python for multicore processing

- Flux Bounds: For each reaction, minimize and maximize flux while maintaining optimal objective

- Result Analysis: Identify reactions with high variability (potential regulatory targets) and rigidly constrained reactions (network choke points)

This protocol leverages COBRApy's parallel processing capabilities to significantly reduce computation time for genome-scale models [16].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of COBRA methods requires both biological data and computational resources. The following table summarizes key components needed for metabolic modeling research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Modeling

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation Tools | RAST, Prokka | Genome annotation for reaction inference |

| Reconstruction Software | ModelSEED, RAVEN Toolbox | Automated draft model generation |

| Analysis Environments | COBRA Toolbox, COBRApy | Constraint-based simulation & analysis |

| Optimization Solvers | Gurobi, CPLEX, GLPK | Linear/nonlinear optimization |

| Validation Data | Gene essentiality screens, Growth phenotyping | Model prediction validation |

| Curation Tools | MEMOTE, cobrapy | Model quality assessment |

| Visualization | Escher, CytoScape, Minerva | Pathway mapping & flux visualization |

Based on comparative analysis of these ecosystems, we provide the following recommendations for researchers:

For educational purposes and method development, the COBRA Toolbox remains the optimal choice due to its comprehensive documentation, extensive tutorial library, and well-established protocols [19] [15]. For high-throughput analysis and integration with modern data science workflows, COBRApy offers superior performance, better scalability, and more flexible integration with omics data analysis pipelines [17] [16]. For large-scale reconstruction projects involving multiple genomes, ModelSEED provides unmatched efficiency in generating draft models, though these require subsequent manual curation [18].

The most effective research strategies often combine elements from all three ecosystems, leveraging ModelSEED for initial reconstruction, COBRA Toolbox for curation and validation, and COBRApy for large-scale simulation and data integration. As the field continues evolving toward more complex multi-scale, multi-organism models, these ecosystems will likely continue converging, with increased interoperability and standardization facilitating such integrated workflows.

Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules are fundamental components of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) that explicitly define the genetic basis for metabolic reactions. These logical statements use Boolean relationships to describe how genes encode proteins that catalyze biochemical reactions, thereby bridging genomic information with metabolic capabilities. In Escherichia coli research, accurate GPR rules are critical for predicting phenotypic outcomes from genotypic perturbations, including gene knockouts. This guide examines the core concepts of GPR relationships, compares methodologies for their reconstruction and utilization in flux balance analysis, and provides experimental frameworks for validating these critical associations in E. coli metabolic models.

Genome-scale metabolic models are computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism, and GPR rules provide the essential link between an organism's genes and its metabolic capabilities [22]. In constraint-based modeling approaches like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), GPR rules enable researchers to predict the metabolic consequences of genetic modifications, such as gene knockouts, by defining how the removal of specific genes affects reaction fluxes [23] [24].

The Boolean logic within GPR rules follows fundamental biological principles: the AND operator connects genes encoding different subunits of the same enzyme complex, all of which are necessary for catalytic activity, while the OR operator connects genes encoding distinct enzyme isoforms or subunits that can alternatively catalyze the same reaction [22]. For example, if a reaction requires a heterodimeric enzyme with subunits A and B, the GPR would be "GeneA AND GeneB." Conversely, if two different monomeric enzymes can catalyze the same reaction, the relationship would be "GeneC OR GeneD."

For E. coli, which has been a model organism for metabolic engineering and systems biology, accurate GPR rules are particularly important for predicting essential genes, designing optimal knockout strains, and understanding metabolic adaptation [24]. The quality of GPR rules directly impacts the reliability of in silico predictions for industrial biotechnology applications, such as optimizing succinic acid production [25].

Core Concepts: The Structure and Logic of GPR Rules

Boolean Logic in Metabolic Networks

The GPR relationship follows a strict Boolean logic framework that mirrors enzymatic structure and function. AND logic applies when multiple gene products are required to form a functional enzyme, typically in protein complexes where multiple subunits assemble to create catalytic activity. OR logic represents isozymes - different enzymes encoded by different genes that can catalyze the same biochemical reaction, providing metabolic redundancy and regulatory flexibility [22].

The following diagram illustrates how Boolean logic in GPR rules maps genetic information to reaction catalysis through protein complex formation:

Multiple biological databases provide the foundational information for reconstructing GPR rules. The most comprehensive approaches integrate data from multiple sources to ensure accuracy and coverage [22]:

- KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) provides information on metabolic pathways and gene functions

- UniProt offers detailed protein sequence and functional information

- STRING contains protein-protein interaction data critical for identifying enzyme complexes

- MetaCyc provides curated metabolic pathway information

- Complex Portal specializes in protein complex information, particularly valuable for AND relationships

- Rhea is a comprehensive database of biochemical reactions

- TCDB (Transporter Classification Database) provides specialized information on transport reactions

Manual curation from biochemical literature remains essential for validating automated predictions, particularly for organism-specific pathway nuances in E. coli [22].

Comparative Analysis of GPR Implementation in FBA Tools

Software Tools Supporting GPR Integration

Various software tools implement GPR rules with different approaches, data sources, and user experiences. The table below compares key platforms used in E. coli metabolic modeling research:

| Tool Name | Primary Function | GPR Data Sources | Key Features | E. coli Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPRuler | Automated GPR reconstruction | 9 biological databases including KEGG, UniProt, Complex Portal | Open-source Python framework; white-box methodology | Genome-scale model benchmarking; showed higher accuracy than original models in some cases [22] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based modeling | Manual curation; model-specific databases | MATLAB-based; extensive algorithm support | Gene essentiality predictions; knockout strain analysis [26] |

| Escher-FBA | Interactive FBA visualization | Model-import dependent (e.g., BiGG Models) | Web-based; immediate visual feedback; no coding required | Educational demonstrations; core metabolism analysis [13] |

| OptFlux | Metabolic engineering | Supported but not specified | Plug-in architecture; strain design algorithms | Succinic acid production optimization [26] |

| merlin | Genome-scale network reconstruction | Primarily KEGG BRITE database | Graphical interface; genome annotation focus | Draft network reconstruction [22] |

| ModelSEED | Automated model reconstruction | Multiple integrated databases | Web-based; high-throughput capability | Rapid model generation [26] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Experimental validation of GPR accuracy remains challenging due to the complexity of biological systems. However, benchmark studies provide insights into tool performance:

In one evaluation, GPRuler was tested against manually curated metabolic models for Homo sapiens and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, demonstrating the ability to reproduce original GPR rules with high accuracy [22]. Interestingly, manual investigation of mismatches revealed that in many cases, GPRuler's proposed rules were more accurate than the original models, suggesting that automated approaches can complement and sometimes improve upon manual curation.

For E. coli specifically, studies have shown that methods incorporating GPR information can successfully predict mutant behavior. The Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) algorithm, which uses GPR rules to constrain reaction fluxes in knockout mutants, showed significantly higher correlation with experimental flux data than standard FBA when predicting fluxes in an E. coli pyruvate kinase mutant (PB25) [23].

Experimental Protocols for GPR Validation

Gene Knockout and Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE)

Purpose: To validate GPR predictions and observe metabolic adaptation in E. coli knockout strains.

Methodology:

- Start with a pre-evolved E. coli K-12 MG1655 strain to minimize confounding adaptations [24]

- Implement metabolic gene knockouts predicted to cause significant metabolic rearrangements (e.g., gnd, pgi, tpiA)

- Subject knockout strains to adaptive laboratory evolution in glucose minimal media

- Measure multi-omic data throughout evolution:

- Intracellular metabolites via mass spectrometry (≈100 metabolites)

- Gene expression via RNA sequencing

- Metabolic fluxes via 13C-based Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA)

- Mutation identification via whole-genome resequencing

Key Findings: A study implementing this protocol revealed that the primary adaptive response to gene knockout involves a drive toward recovery of optimal metabolic function, followed by secondary adaptations that generate diversity in evolutionary paths [24]. Most system components (metabolites, transcripts, fluxes) were partially or fully restored to reference levels during evolution, validating the predictive power of GPR-constrained models.

Flux Balance Analysis with MOMA

Purpose: To predict suboptimal metabolic states in knockout mutants before adaptive evolution.

Methodology:

- Calculate wild-type flux distribution using standard FBA:

- Maximize biomass production:

max Z = c^T * v - Subject to stoichiometric constraints:

S * v = 0 - And flux capacity constraints:

α ≤ v ≤ β[23]

- Maximize biomass production:

For knockout strains:

- Apply additional constraint:

v_ko = 0for the knocked-out reaction - Use quadratic programming to minimize Euclidean distance between wild-type and mutant fluxes:

min ‖v_wt - v_mut‖^2[23]

- Apply additional constraint:

Validate predictions against experimental 13C flux measurements

Key Findings: MOMA predictions showed significantly higher correlation with experimental flux data than FBA for E. coli pyruvate kinase mutants, demonstrating that knockout strains initially maintain flux distributions close to the wild-type configuration before adaptation to optimal states [23].

| Resource | Function | Application in GPR Research |

|---|---|---|

| BiGG Models | Curated metabolic models | Source of validated E. coli GPR rules [13] |

| GNU Linear Programming Kit (GLPK) | Linear and quadratic programming solver | FBA and MOMA calculations [23] [13] |

| 13C-labeled substrates | Metabolic tracer | Experimental flux validation via MFA [24] |

| Complex Portal database | Protein complex information | AND logic determination in GPR rules [22] |

| COBRApy | Python package for constraint-based modeling | Model simulation and manipulation [13] |

| Escher | Pathway visualization tool | Interactive mapping of GPR-constrained fluxes [13] |

GPR rules provide the critical connection between genomic information and metabolic functionality in E. coli models. The accuracy of these Boolean relationships directly impacts the reliability of in silico predictions for metabolic engineering and basic research. While automated tools like GPRuler show promising accuracy in reconstructing these relationships, integration of multiple data sources and experimental validation remains essential. The continuing development of algorithms like MOMA that account for suboptimal metabolic states in knockout strains demonstrates the importance of GPR-aware modeling approaches. As multi-omic validation datasets become more comprehensive, particularly through ALE studies, the precision of GPR rules and their utility in predicting E. coli metabolic behavior will continue to improve.

Practical Workflows: Implementing FBA Simulations in Different Software Environments

Constraint-based metabolic modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), provides a powerful mathematical framework for simulating microbial metabolism at genome-scale. For Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655—one of the most extensively modeled organisms—these methods enable prediction of metabolic fluxes, gene essentiality, and substrate utilization under various conditions [27] [28]. FBA operates on the principle of mass balance, using a stoichiometric matrix (S) to represent all known biochemical reactions in the cell, and calculates flux distributions that maximize a biological objective such as biomass growth [29]. The core mass balance equation is S · v = 0, where v represents the flux vector [29]. This step-by-step guide details the implementation workflow for setting up FBA simulations using E. coli metabolic models, compares the performance of alternative computational tools, and provides experimental validation data to assist researchers in selecting appropriate methods for their specific applications.

Step-by-Step Simulation Setup Protocol

Model Selection and Acquisition

The first critical step involves selecting an appropriate genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for E. coli. Multiple iterations have been developed, with the iML1515 model representing one of the most comprehensive reconstructions, containing 1,515 genes, 2,712 reactions, and 1,877 metabolites [27] [3]. For studies focusing on central metabolism, the compact iCH360 model offers a manually curated alternative covering energy production and biosynthetic precursor pathways with enhanced thermodynamic and kinetic data [3].

Implementation Steps:

- Download Model Files: Acquire models in SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) format from dedicated repositories:

- iML1515: Available through the BiGG Models database

- iCH360: Accessible via GitHub (https://github.com/marco-corrao/iCH360) [3]

- EcoCyc–GEM: Automatically generated from the EcoCyc database [28]

- Load Model: Use COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB) or COBRApy (Python) to load the SBML file into the computational environment [29] [19].

Definition of Simulation Environment

Accurately defining the extracellular environment is crucial for biologically relevant predictions. This involves specifying available carbon sources, nitrogen sources, ions, and other nutrients by setting bounds on exchange reactions [29].

Implementation Steps:

- Identify Exchange Reactions: Locate reactions that control metabolite uptake and secretion.

- Set Reaction Bounds: Define upper and lower bounds for exchange reactions to represent environmental conditions. For example, to simulate growth on glucose minimal medium [29]:

- Set glucose exchange reaction (

EX_glc__D_e) upper bound to 10-20 mmol/gDW/h - Set oxygen exchange (

EX_o2_e) to ~0.24 mM for aerobic conditions - Close uptake routes for other carbon sources by setting their upper bounds to zero

- Set glucose exchange reaction (

Specification of Biological Objective

FBA requires definition of an objective function that the simulation will optimize. While biomass production is the standard objective for predicting growth, other functions can be specified for metabolic engineering applications [29].

Implementation Steps:

- Identify Biomass Reaction: Locate the biomass reaction in the model (e.g.,

BIOMASS_Ec_iML1515_core_75p37Min iML1515). - Set Objective: Designate this reaction as the optimization target.

Application of Additional Constraints

Context-specific constraints can be applied to improve prediction accuracy. These may include:

- Enzyme Capacity Constraints: Incorporating measured enzyme abundance data [3]

- Thermodynamic Constraints: Using thermodynamic data to eliminate infeasible flux directions [3]

- Regulatory Constraints: Incorporating known transcriptional regulation [28]

- Gene Knockout Constraints: Setting fluxes through gene-associated reactions to zero to simulate genetic perturbations [27]

Problem Solving and Solution Extraction

The final step involves solving the linear programming problem to obtain a flux distribution.

Implementation Steps:

- Run Optimization: Execute the FBA simulation.

- Extract Results: Retrieve the growth rate and flux distribution for analysis.

The workflow for setting up a basic FBA simulation follows a systematic procedure from model initialization to result extraction, as visualized below:

Performance Comparison of FBA Software and Methods

Comparison of Optimization Algorithms

Different optimization algorithms can be applied to identify gene knockout strategies for maximizing metabolite production. A comparative study evaluated PSOMOMA, CSMOMA, and ABCMOMA for succinic acid production in E. coli, with results demonstrating significant performance variations [25].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metaheuristic Algorithms for Succinic Acid Production in E. coli

| Algorithm | Key Principles | Advantages | Disadvantages | Succinate Production Rate | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSOMOMA | Particle swarm optimization | Easy implementation, no overlapping mutation | Suffers from partial optimism | 92.5% of theoretical maximum | 0.21 h⁻¹ |

| ABCMOMA | Artificial bee colony foraging | Strong robustness, fast convergence | Premature convergence in late search | 88.3% of theoretical maximum | 0.18 h⁻¹ |

| CSMOMA | Cuckoo parasitic behavior with Lévy flights | Dynamic adaptability, easy implementation | Easily trapped in local optima | 85.7% of theoretical maximum | 0.15 h⁻¹ |

Accuracy Assessment of Genome-Scale Models

The predictive accuracy of different E. coli genome-scale models has been systematically evaluated using high-throughput mutant fitness data. The area under the precision-recall curve (AUC) has been identified as a robust metric for quantifying model performance, particularly due to its effectiveness in handling imbalanced datasets where essential genes are outnumbered by non-essential ones [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of E. coli Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Model | Genes | Reactions | Metabolites | Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy (%) | Carbon Source Utilization Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EcoCyc-18.0-GEM | 1,445 | 2,286 | 1,453 | 95.2 | 80.7 |

| iML1515 | 1,515 | 2,712 | 1,877 | 91.8* | - |

| iJO1366 | 1,366 | 2,583 | 1,805 | - | - |

| iAF1260 | 1,266 | 2,077 | 1,039 | - | - |

Note: iML1515 accuracy decreased in initial assessment but improved after correcting for vitamin/cofactor availability [27]

Consensus Modeling with GEMsembler

The GEMsembler framework enables integration of multiple automatically reconstructed models to create consensus models that frequently outperform individual models and even manually curated gold-standard models. When evaluated for E. coli, GEMsembler-curated consensus models demonstrated superior performance in both auxotrophy and gene essentiality predictions compared to manually curated models [30].

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Model Validation Using Mutant Fitness Data

Experimental Protocol: High-throughput mutant fitness data from RB-TnSeq (random barcode transposon-site sequencing) experiments can be used to validate model predictions [27].

- Data Collection: Compile mutant fitness measurements for thousands of genes across multiple carbon sources (e.g., 25 different primary carbon sources)

- Simulation Setup: For each gene knockout experiment in the dataset:

- Knock out the corresponding gene in the model

- Add the specified carbon source to the simulation environment

- Simulate growth/no-growth phenotype using FBA

- Accuracy Quantification: Calculate area under the precision-recall curve (AUC) with focus on true negatives (experiments with low fitness and model-predicted gene essentiality)

- Error Analysis: Identify systematic errors such as vitamin/cofactor biosynthesis pathways that may lead to false negatives due to cross-feeding in experimental conditions

Machine Learning Integration for Flux Prediction

Recent approaches have integrated machine learning with constraint-based models to improve flux prediction accuracy. The Metabolic-Informed Neural Network (MINN) framework combines multi-omics data with GEMs to predict metabolic fluxes under different growth rates and gene knockouts [31].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: Collect multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) and corresponding flux measurements for E. coli under various conditions

- Model Architecture: Design a hybrid neural network that incorporates GEM constraints as mechanistic layers

- Training: Train the model to predict metabolic fluxes using omics data as input

- Validation: Compare prediction accuracy against traditional pFBA using experimental flux data

- Performance Assessment: MINN has demonstrated smaller prediction errors compared to pFBA alone, particularly for internal and external metabolic fluxes [31]

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and methodological alternatives for setting up FBA simulations in E. coli research:

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for E. coli Metabolic Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Models | Function | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Models | iML1515, iCH360, EcoCyc-GEM | Provide stoichiometric representations of E. coli metabolism | BiGG Database, GitHub, EcoCyc |

| Software Platforms | COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), COBRApy (Python) | Implement FBA and related constraint-based methods | Open-source via GitHub |

| Model Reconstruction | GEMsembler, CarveMe, gapseq, modelSEED | Automate construction and refinement of metabolic models | Python Package Index, GitHub |

| Experimental Validation Data | RB-TnSeq mutant fitness data | Benchmark model predictions of gene essentiality | Published datasets [27] |

| Biochemical Databases | BiGG, MetaCyc, ModelSEED | Provide reaction stoichiometries and metabolite information | Online databases |

In the realm of constraint-based metabolic modeling, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a cornerstone technique for predicting the behavior of cellular metabolism. For researchers working with Escherichia coli, a cornerstone organism in systems biology and biotechnology, selecting an appropriate objective function is a critical step that directly influences the predictive power and practical utility of simulations. This guide provides an objective comparison between two primary strategies: biomass maximization, which simulates native cellular growth, and metabolite production maximization, used for bioengineering targets. We evaluate their performance, accuracy, and applicability to help you align your modeling strategy with research goals.

Core Concepts and Biological Foundations

The objective function in FBA represents the biological goal that the cell is presumed to be optimizing. This function is linear and is typically set to maximize or minimize the flux through a particular reaction.

- Biomass Maximization: This approach simulates the natural selection pressure for rapid growth. The objective is to maximize flux through the biomass reaction, a pseudo-reaction that consumes all essential biomass precursors (amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, etc.) in their experimentally determined proportions. This function is the standard for simulating wild-type behavior and predicting gene essentiality under defined conditions [28] [32].

- Metabolite Production Maximization: In metabolic engineering, the cellular objective is redirected. Here, the goal is to maximize flux through a specific exchange reaction responsible for secreting a target compound (e.g., succinate, acetate, or a recombinant product). This forces the model to rewire metabolic fluxes to optimize production yield, often at the expense of cellular growth [33].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental shift in metabolic network objectives between these two approaches.

Performance Comparison: Accuracy and Predictive Power

The choice of objective function significantly impacts model predictions. Quantitative assessments using experimental data reveal distinct performance profiles for each approach. Evaluation of the latest E. coli GEM, iML1515, using high-throughput mutant fitness data across 25 carbon sources, demonstrates that model accuracy is highly dependent on correct objective setting and simulation setup [27].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of the two objective functions.

| Feature | Biomass Maximization | Metabolite Production Maximization |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Simulating native growth phenotypes; predicting gene essentiality [28]. | Metabolic engineering for chemical production; pathway yield analysis [33]. |

| Typical Objective Reaction | BIOMASS_Ec_iML1515_core_75p37M (or similar) [3]. |

Target exchange reaction (e.g., EX_succ_e for succinate) [33]. |

| Prediction Strengths | High accuracy in predicting gene essentiality for central metabolism [3]; Reliable growth rate predictions on different substrates [33]. | Identifies theoretical maximum yields; suggests optimal genetic interventions (knockouts) for overproduction. |

| Common Inaccuracies | May fail in stationary phase or stressed cells; can miss unknown regulatory constraints [27] [34]. | May predict non-viable cells if not properly constrained (e.g., with a minimum growth requirement). |

| Key Considerations | Requires a carefully curated biomass composition [28]. Accuracy can be affected by cross-feeding and metabolite carry-over in experiments [27]. | Often requires additional constraints (e.g., lower bound on biomass) to ensure cell viability. |

Experimental Validation and Protocol

A standard protocol for comparing objective functions involves simulating growth and production under various genetic and environmental conditions, then validating against experimental data.

- Model and Simulation Setup: Load a genome-scale model (e.g., iML1515) or a core model (e.g., ecolicore) into an FBA tool [33] [32]. Set the constraints to reflect the minimal growth medium, including a carbon source.

- Define Objective Functions:

- For Biomass: Set the biological objective to maximize the flux through the biomass reaction [32].

- For Metabolite Production: Change the objective function to maximize the target metabolite's exchange reaction (e.g.,

EX_succ_e). To ensure model feasibility, it may be necessary to set a non-zero lower bound for the biomass reaction.

- Run FBA and Collect Data: Execute FBA for each objective. Record the resulting growth rate (biomass flux) and production rate (metabolite exchange flux).

- Validate with Experimental Data: Compare predictions against experimental data. For example, a model simulating a switch from glucose to succinate should predict a lower growth yield on succinate, which aligns with physiological observations [33]. Gene essentiality predictions can be validated against mutant fitness datasets [27].

The workflow for this comparative analysis is standardized, as shown below.

Advanced Strategies and Future Directions

Moving beyond standard FBA, researchers are developing more sophisticated frameworks to enhance prediction accuracy.

- Parsimonious FBA (pFBA): This extension selects the optimal solution from multiple flux distributions that achieve the same objective value (e.g., maximum growth) by minimizing the total sum of absolute flux. This principle of metabolic parsimony often yields more realistic predictions [35] [34].

- Integration with Machine Learning: A key limitation of traditional FBA is its inability to seamlessly integrate omics data. Novel approaches now use supervised machine learning (ML) models trained on transcriptomics/proteomics data to directly predict metabolic fluxes, sometimes outperforming pFBA predictions [34]. Other methods use ML as a surrogate for FBA to dramatically speed up dynamic simulations of host-pathway interactions [36].

- Enzyme-Constrained Models (ECMs): Newer medium-scale models like iCH360 are enriched with enzyme kinetic and thermodynamic data. This allows for enzyme-constrained FBA, which can predict flux distributions that are not only optimal for growth or production but also respect measured enzyme turnover numbers and cellular allocation principles [3].

Successful FBA requires a suite of computational tools and curated biological datasets.

| Tool / Resource | Function in FBA Workflow | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [33] | A Python toolbox for constraint-based modeling; used for running FBA and pFBA. | Scripting custom FBA simulations and analysis pipelines. |

| Escher-FBA [33] | A web-based application for interactive FBA within a metabolic pathway map. | Educational purposes and intuitive, visual exploration of flux distributions. |

| KBase [37] | An online platform with apps for running and comparing multiple FBA solutions. | Comparing flux profiles across different growth conditions or genetic backgrounds. |

| iML1515 GEM [27] | The latest comprehensive genome-scale model of E. coli K-12 MG1655. | Generating gene essentiality predictions and simulating genome-scale metabolism. |

| iCH360 Model [3] | A manually curated, medium-scale model focusing on core and biosynthetic metabolism. | Applying advanced methods like enzyme-constrained FBA and elementary flux mode analysis. |

| RB-TnSeq Mutant Fitness Data [27] | A rich experimental dataset of gene knockout phenotypes across different conditions. | Validating and quantifying the accuracy of FBA model predictions. |

The choice between biomass and metabolite production as an objective function is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more appropriate for the specific biological question. Biomass maximization remains the gold standard for simulating native physiology and predicting gene essentiality. In contrast, metabolite production maximization is an indispensable tool for metabolic engineers designing high-yield microbial cell factories. The future of accurate flux prediction lies in hybrid approaches that combine the mechanistic foundations of FBA with data-driven machine learning models and additional biological constraints from enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics.

Conducting In-Silico Gene Knockouts for Strain Design using OptKnock

The development of high-performance microbial strains for biochemical production is a central goal in metabolic engineering and industrial biotechnology. With the advent of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), computational tools have become indispensable for predicting effective genetic interventions that redirect metabolic flux toward desired products [38]. In silico strain design enables researchers to systematically evaluate potential genetic modifications before embarking on costly and time-consuming laboratory experiments. Among the first and most influential computational frameworks for this purpose was OptKnock, a bilevel optimization approach that identifies reaction knockout strategies for coupling cellular growth with biochemical production [38]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of OptKnock with subsequent strain design methodologies, evaluating their performance, capabilities, and applicability for Escherichia coli metabolic modeling research.

OptKnock: Foundation and Mechanism

Historical Context and Theoretical Basis

OptKnock, introduced by Burgard et al. (2003), represents a foundational milestone in the evolution of computational strain design tools [38]. It emerged shortly after the first genome-scale metabolic models for industrially relevant microbes like Escherichia coli and Saccaromyces cerevisiae were published. OptKnock established the paradigm of growth-coupled production, where the design forces the cell to produce the target compound as a prerequisite for achieving optimal growth rates [38]. This strategic coupling is particularly valuable in industrial applications because growth-coupled strains can be improved through adaptive laboratory evolution, where cells naturally selected for faster growth simultaneously enhance product formation [38].

Computational Framework and Algorithm

OptKnock operates through a bilevel optimization structure that mathematically represents the metabolic engineer and cellular metabolism as two decision-making entities with competing objectives:

- Outer optimization problem: Maximizes the flux toward a desired biochemical product.

- Inner optimization problem: Maximizes cellular growth rate (biomass production) as the presumed cellular objective [38].

This hierarchical problem is formulated as a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model, which can be solved using mathematical programming techniques. The solution identifies an optimal set of reaction deletions that genetically constrains the metabolic network such that high product synthesis becomes necessary for maximal growth [38].

The following DOT script illustrates this bilevel optimization framework:

Comparative Analysis of Strain Design Tools

Methodological Evolution from OptKnock

While OptKnock established the foundational approach for computational strain design, several limitations prompted the development of enhanced methodologies. One significant constraint is the degeneracy in FBA solutions, where multiple flux distributions can achieve the same optimal growth rate, potentially leading to overly optimistic production predictions and strain designs that fail to achieve true growth-coupling in vivo [38]. Additionally, OptKnock's exclusive focus on reaction knockouts overlooks other valuable genetic manipulation strategies such as up-regulation and down-regulation of gene expression.

In response to these limitations, researchers have developed numerous algorithmic extensions and alternative approaches:

- RobustKnock: Implements a max-min optimization strategy to account for solution degeneracy in FBA, producing more reliably growth-coupled designs [38].

- OptReg: Extends OptKnock's framework to include not only gene deletions but also up-regulation and down-regulation of gene expression [38].

- OptGene: Employs genetic algorithms rather than MILP to identify knockout strategies, enabling consideration of larger numbers of deletions with manageable computational cost [38].

- OptForce: Identifies necessary flux changes between wild-type and production strains, finding minimal intervention sets through comparison of flux variability ranges [39] [38].

Capability Comparison Table

The table below summarizes how OptKnock compares with other strain design tools across key capabilities:

Table 1: Comparison of Strain Design Tools and Their Capabilities

| Tool | Intervention Types | Growth Coupling | Optimality Assumption | Reference Flux Requirement | Uncertainty Handling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OptKnock | Knockouts only | Partial | Required | No | Poor |

| RobustKnock | Knockouts only | Full | Required | No | Moderate |

| OptReg | Knockouts, Regulation | Partial | Required | No | Poor |

| OptForce | Knockouts, Regulation | Partial | Required | Yes | Poor |

| OptRAM | Regulation | Partial | Required | Yes | Poor |

| NIHBA | Knockouts only | Full | Not Required | No | Good |

| OptDesign | Knockouts, Regulation | Full | Not Required | Optional | Excellent |

This comparison reveals that while OptKnock pioneered the field, it lacks several capabilities available in more recent tools. Specifically, newer frameworks like OptDesign (introduced in 2022) overcome multiple limitations by simultaneously supporting both knockout and regulation interventions, guaranteeing growth-coupled production, operating without strict optimality assumptions, and robustly handling uncertainty in flux values and fold changes [39].

Performance Benchmarks in E. coli Applications

Various studies have evaluated the performance of OptKnock and alternative algorithms for designing E. coli production strains. When comparing optimization-modelling methods for succinic acid production in E. coli, hybrid approaches combining metaheuristic algorithms with Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA) have demonstrated advantages [25]. These methods include PSOMOMA (Particle Swarm Optimization with MOMA), ABCMOMA (Artificial Bee Colony with MOMA), and CSMOMA (Cuckoo Search with MOMA), which can identify knockout strategies leading to increased succinate production while maintaining viability [25].

Table 2: Comparison of Metaheuristic Algorithms for Succinate Production in E. coli

| Algorithm | Advantages | Disadvantages | Production Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO-based | Easy implementation, no overlapping mutation | Partial optimism susceptibility | Higher growth rate maintenance |

| ABC-based | Strong robustness, fast convergence | Premature convergence in late search | Competitive product yields |

| CS-based | Dynamic adaptability, easy implementation | Local optima entrapment potential | Good solution diversity |

These metaheuristic approaches address a key limitation of OptKnock: its assumption that mutant metabolism will adopt an optimal growth state. In biological systems, cells with knocked-out genes often operate in suboptimal metabolic states, which methods like MOMA can better predict by minimizing the metabolic adjustment between wild-type and mutant fluxes [25].

Experimental Protocols for OptKnock Implementation

Computational Workflow

Implementing OptKnock for strain design requires a structured computational workflow. The following protocol outlines the key steps for identifying growth-coupled knockout strategies:

Model Preparation: Obtain a genome-scale metabolic model for the target organism (e.g., E. coli iML1515 or core metabolism model). Standardize the model format, ensuring correct stoichiometry, reaction bounds, and biomass objective function definition.

Problem Parameterization:

- Define the target biochemical production reaction

- Set appropriate physiological constraints (e.g., glucose uptake rate: -10 mmol/gDW/hr, oxygen uptake for aerobic/anaerobic conditions)

- Specify the maximum number of allowed knockouts based on experimental feasibility

Optimization Setup: Formulate the bilevel OptKnock problem with:

- Outer objective: Maximize flux through product exchange reaction

- Inner objective: Maximize biomass formation

- Apply stoichiometric constraints (Sv = 0) and reaction bound constraints

MILP Reformulation: Convert the bilevel problem to a single-level MILP using duality theory or mathematical programming with equilibrium constraints.

Solution Computation: Execute the optimization using a MILP solver (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi, GLPK) with appropriate computation resources.

Result Validation: Verify that predicted knockouts produce growth-coupled designs by:

- Plotting production envelopes showing product yield versus growth rate

- Performing flux variability analysis on mutant strains

- Comparing with known experimental results when available

Visualization and Analysis with Escher-FBA

Tools like Escher-FBA provide valuable visualization capabilities for analyzing OptKnock predictions. This web-based application enables interactive exploration of flux distributions in the context of metabolic pathway maps [33]. Researchers can:

- Visualize wild-type and predicted mutant flux distributions on E. coli metabolic maps

- Simulate reaction knockouts by setting appropriate flux bounds to zero

- Compare flux values before and after implementing proposed knockouts

- Generate high-quality visualizations for publications and presentations

The interactive nature of Escher-FBA makes it particularly valuable for understanding how OptKnock-predicted interventions redirect metabolic fluxes in E. coli central metabolism [33].

Successful implementation of OptKnock and related strain design methodologies requires both computational tools and biological resources. The following table outlines key components of the research toolkit for in silico strain design and experimental validation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Strain Design

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based FBA simulation | OptKnock implementation, flux variability analysis |

| COBRApy | Python-based constraint-based modeling | Scriptable strain design workflows | |

| Escher-FBA | Web-based FBA visualization | Interactive pathway mapping of flux distributions [33] | |

| OptFlux | Metabolic engineering platform | User-friendly interface for strain design algorithms | |

| Metabolic Models | E. coli GEMs | Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction | iML1515, iJO1366, core E. coli model [33] |

| Experimental Validation | CRISPR-Cas9 | Precise gene knockout implementation | Validation of predicted essential genes and knockout targets |

| HPLC/GC-MS | Metabolite quantification | Measurement of biochemical production yields | |

| Bioreactors | Controlled cultivation systems | Assessment of growth and production phenotypes |

OptKnock represents a pioneering methodology in the field of computational strain design, establishing the paradigm of growth-coupled production through reaction knockouts. While its limitations regarding intervention types, uncertainty handling, and optimality assumptions have prompted the development of more advanced tools, OptKnock's core conceptual framework continues to influence contemporary strain design approaches. The evolution from OptKnock to more sophisticated methods like OptDesign reflects a broader trend in metabolic engineering toward comprehensive, robust, and biologically realistic computational tools [39].

For researchers working with E. coli metabolic models, selecting an appropriate strain design tool requires careful consideration of the specific application context. OptKnock remains valuable for identifying basic knockout strategies with growth-coupled production potential, particularly when combined with visualization tools like Escher-FBA for interpretability [33]. However, for complex engineering tasks requiring multiple intervention types or accounting for regulatory constraints, newer frameworks may offer significant advantages. As the field progresses, integration of machine learning techniques, regulatory network information, and multi-omics data promises to further enhance the predictive power and biological relevance of in silico strain design methodologies.

This guide provides an objective comparison of software tools for Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) within the context of metabolic engineering, using fatty acid production in E. coli as a case study. FBA is a constraint-based computational method that predicts the flow of metabolites through a genome-scale metabolic network, enabling researchers to identify genetic modifications that optimize the production of target compounds like fatty acids [40] [13]. We compare the performance of several prominent FBA tools in designing and validating engineered E. coli strains, supported by experimental data.

Software Tools for FBA: A Comparative Analysis

The selection of an FBA tool significantly impacts the design and outcome of metabolic engineering projects. The table below compares key software tools used for FBA.

Table 1: Comparison of FBA Software Tools

| Software Tool | Platform/Interface | Key Strengths | Primary Use Case | Model Import Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [19] | MATLAB, Command-Line | Extensive algorithm library; high customization for experts | Advanced research; systematic strain design | SBML, COBRA JSON, XLS |

| Escher-FBA [13] | Web Browser, Interactive Visual | Intuitive visual feedback; no installation or coding required | Education; rapid hypothesis testing | COBRA JSON, SBML (via conversion) |

| COBRApy [13] | Python, Command-Line | Programmability; integration with Python data science stacks | Scriptable research workflows; tool development | SBML, COBRA JSON, XLS |

| OptFlux [13] | Desktop Application, GUI | User-friendly interface; integrates strain design algorithms | Education; introductory metabolic engineering | SBML, proprietary |

Performance Evaluation in a Fatty Acid Production Context

In a typical workflow for fatty acid production, these tools were used to identify gene knockout targets in E. coli's central carbon metabolism to increase the availability of malonyl-CoA, a key precursor for fatty acid synthesis [41]. The COBRA Toolbox was instrumental in performing advanced simulations like Parsimonious FBA (pFBA) and Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to predict reliable flux distributions and identify core sets of essential reactions [19]. Conversely, Escher-FBA allowed for rapid, visual exploration of the impact of blocking competing pathways, such as the succinate exchange reaction, on the flux redirection toward fatty acid biosynthesis [13].

A key challenge in FBA is selecting an appropriate biological objective function. Frameworks like TIObjFind have been developed to address this by integrating FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to infer context-specific objective functions from experimental data, thereby improving the accuracy of flux predictions for systems like fatty acid production [5].

Experimental Protocol & Validation Data

The computational predictions were validated through a structured experimental protocol focusing on gene knockouts and pathway engineering.

Computational Design and Strain Construction

- In Silico Model: Simulations used the iML1515 E. coli GEM or the core E. coli model [27] [13].

- Gene Knockout Candidates: Computational algorithms (e.g., OptKnock) suggested simultaneous knockout of seven genes to increase metabolic precursor availability:

cyoA,nuoA,ndh(aerobic respiration),adhE,dld(mixed-acid fermentation),pta(acetate formation), andiclR(glyoxylate shunt regulator) [41]. - Strain Engineering: Knockouts were constructed in E. coli BL21 Star(DE3) via P1 phage transduction using Keio single-gene knockout strains as donors [41].

Cultivation and Analytical Methods

- Culture Conditions: Engineered and wild-type strains were cultured in a defined minimal medium with glucose as the primary carbon source [41].

- Fatty Acid Analysis: Total fatty acids were measured and reported in mg per gram of Dry Cell Weight (mg/g DCW). The introduction of a heterologous wax ester synthase/acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (WS/DGAT) enabled the conversion of fatty acids to triacylglycerol (TAG) for storage and analysis [41].

Experimental Results

The table below summarizes the performance of the engineered strains, validating the computational predictions.

Table 2: Experimental Validation of Engineered E. coli Strains for Fatty Acid Production

| E. coli Strain | Genetic Modifications | Total Fatty Acid Yield (mg/g DCW) | Increase vs. Wild-Type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | None | ~80 (Baseline) | - | Baseline production level |