A Comprehensive Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Protocol for E. coli: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on implementing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) for E.

A Comprehensive Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Protocol for E. coli: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on implementing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) for E. coli, a cornerstone constraint-based modeling technique in systems biology and metabolic engineering. We detail the foundational principles of FBA, including stoichiometric modeling, steady-state assumptions, and the use of genome-scale models like iML1515. The protocol covers methodological steps from model selection and constraint setting to advanced optimization techniques, integrating enzyme constraints via ECMpy and addressing dynamic modeling with dFBA. We further explore troubleshooting common pitfalls, optimizing predictions with frameworks like TIObjFind, and validating models through machine learning and experimental data integration. This guide is tailored for professionals in drug discovery and bioprocess development seeking to leverage E. coli metabolic models for predictive analysis and strain optimization.

Understanding Flux Balance Analysis: Core Principles and E. coli Metabolic Networks

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) is a computational framework for analyzing the metabolic capabilities of cells using genome-scale metabolic models [1]. This approach relies on constructing a stoichiometric matrix (S) that represents the entire metabolic network of an organism, with columns representing reactions and rows representing metabolites [1] [2]. The stoichiometric coefficient S(i,j) indicates the participation of metabolite i in reaction j. CBM has become an essential tool in systems biology with applications ranging from bioprocess engineering to drug target identification [1] [2].

The power of CBM lies in its ability to analyze large-scale metabolic networks without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data, which is often unavailable for most enzymes [1] [2]. Instead, CBM imposes constraints based on fundamental biological, chemical, and physical principles to define the set of possible metabolic behaviors. These constraints include: mass balance of metabolites, thermodynamic constraints on reaction directionality, and capacity constraints on enzyme activities and substrate uptake [1].

The Steady-State Assumption: Theoretical Foundation

The steady-state assumption is a cornerstone of constraint-based modeling, stating that the production and consumption of intracellular metabolites are balanced, resulting in no net accumulation or depletion over time [3] [2]. This is mathematically represented as:

S · v = 0

where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v is the vector of metabolic fluxes [2]. This equation formalizes the concept that for each internal metabolite, the sum of fluxes producing it equals the sum of fluxes consuming it [4].

The steady-state assumption can be motivated from two perspectives [3]. First, from a timescale perspective, metabolic reactions typically occur much faster than cellular processes like gene expression and cell division, making the quasi-steady-state approximation reasonable. Second, from a long-term perspective, no metabolite can accumulate or deplete indefinitely in a sustainable biological system. Research has demonstrated that this assumption applies even to oscillating and growing systems without requiring quasi-steady-state at every time point [3].

Mathematical Formulation of Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is the most widely used constraint-based method [2]. FBA converts the underdetermined system of steady-state equations into a determined linear programming problem by introducing an objective function to be optimized [2] [4]. The complete FBA problem can be formulated as:

Maximize: Z = cᵀv Subject to: S · v = 0 vₗᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ vᵤᵢ for all reactions i

where c is a vector of weights indicating which reactions contribute to the cellular objective, and vₗᵢ and vᵤᵢ are lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux vᵢ [2].

The table below summarizes key components of the FBA mathematical framework:

Table 1: Mathematical Components of Flux Balance Analysis

| Component | Symbol | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | S | m × n matrix where m = metabolites, n = reactions | S(i,j) = -1 if metabolite i is consumed, +1 if produced |

| Flux Vector | v | n × 1 vector of reaction fluxes | v = [vâ‚, vâ‚‚, ..., vâ‚™]áµ€ |

| Mass Balance | S·v = 0 | Steady-state constraint | For metabolite i: ∑S(i,j)·vⱼ = 0 |

| Flux Constraints | vₗᵢ, vᵤᵢ | Lower/upper bounds on fluxes | 0 ≤ vᵢ ≤ ∞ for irreversible reaction |

| Objective Function | cáµ€v | Linear combination of fluxes to optimize | cáµ¢ = 1 for biomass reaction, 0 otherwise |

FBA problems are typically solved using linear programming algorithms such as the simplex method [4]. The solution provides a flux distribution that maximizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints.

Protocol: Implementing FBA for E. coli Research

Model Reconstruction and Curation

For E. coli research, the well-curated iML1515 model serves as an excellent starting point [5]. This genome-scale metabolic model includes 1,515 open reading frames, 2,719 metabolic reactions, and 1,192 metabolites [5]. The reconstruction process involves:

Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Association: Establishing Boolean relationships between genes and the reactions they catalyze [5] [2]. For example, (geneA AND geneB) indicates protein subunits, while (geneA OR geneB) indicates isoenzymes [2].

Gap Filling: Identifying and adding missing reactions required for metabolic functionality based on genomic evidence and experimental data [5].

Directionality Assignment: Constraining reaction reversibility/irreversibility based on thermodynamic considerations [5].

Constraints Definition

The following table outlines key constraints for FBA simulations in E. coli:

Table 2: Typical Constraints for E. coli FBA in Aerobic Glucose Minimal Medium

| Constraint Type | Reaction | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Uptake | EXglcDe | -10 | 0 | Glucose uptake rate |

| Oxygen Uptake | EXo2e | -18 | 0 | Aerobic conditions |

| ATP Maintenance | ATPM | 8.39 | 8.39 | Non-growth associated maintenance |

| Byproduct Secretion | EXace | 0 | ∞ | Acetate secretion allowed |

| Biomass Reaction | BIOMASSEciML1515 | 0 | ∞ | Biomass production |

Implementation Workflow

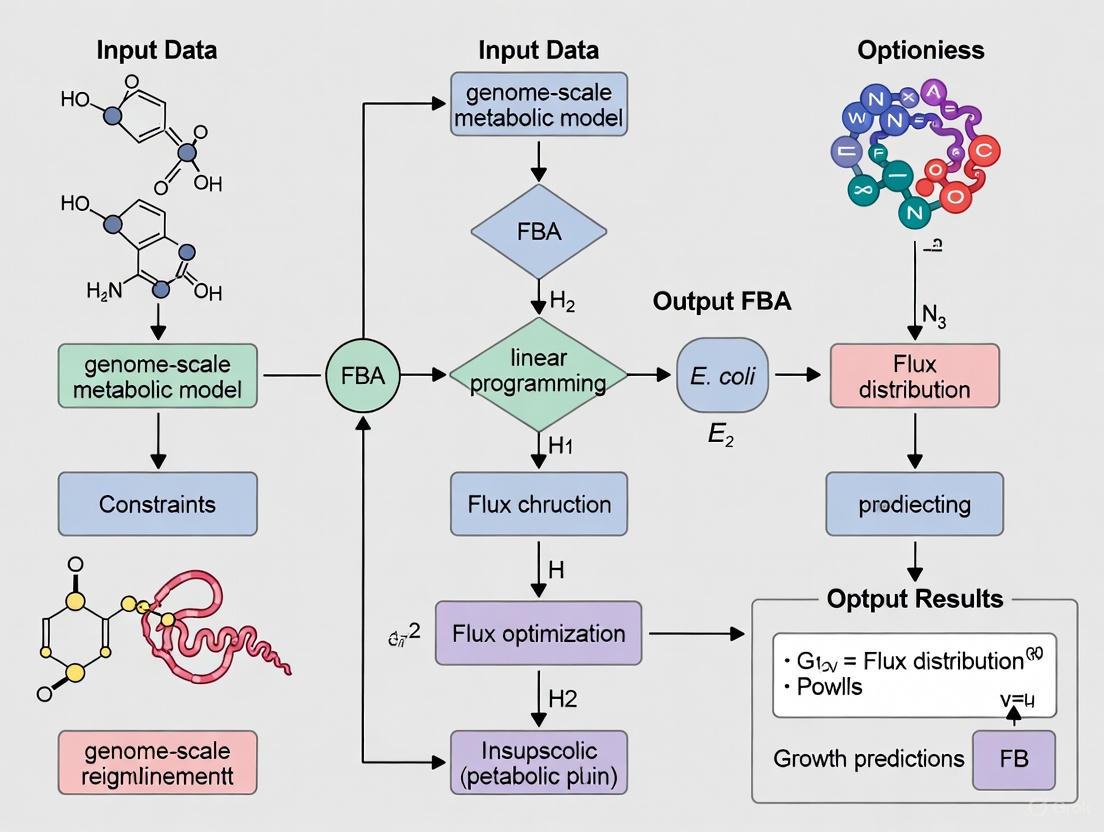

The following diagram illustrates the complete FBA workflow for E. coli research:

Advanced Methods and Extensions

Dynamic FBA

Dynamic FBA extends the basic framework to incorporate time-dependent changes in the extracellular environment [1]. This method simulates time courses by using the outputs of earlier time steps as inputs for subsequent steps [1]. The implementation involves:

- Solving FBA at time t to determine metabolic fluxes

- Updating extracellular metabolite concentrations using the calculated uptake/secretion rates

- Using updated concentrations as constraints for time t+Δt

- Repeating until the simulation endpoint is reached

Regulatory FBA

Regulatory FBA integrates gene regulatory information with metabolic constraints [1]. This approach uses Boolean rules based on regulatory knowledge to activate or deactivate reactions in specific conditions [1]. For E. coli, this can model the effects of carbon catabolite repression and other global regulatory networks.

Enzyme-Constrained Models

Recent advances incorporate enzyme capacity constraints to improve flux predictions [5] [6]. The ECMpy workflow adds total enzyme constraints without altering the stoichiometric matrix structure [5]. Key modifications for E. coli include:

Table 3: Enzyme Constraints for Engineered L-Cysteine Production in E. coli

| Parameter | Gene/Enzyme | Original Value | Modified Value | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcat_forward | PGCD (SerA) | 20 1/s | 2000 1/s | Remove feedback inhibition [5] |

| Kcat_reverse | SERAT (CysE) | 15.79 1/s | 42.15 1/s | Increased mutant activity [5] |

| Gene Abundance | SerA/b2913 | 626 ppm | 5,643,000 ppm | Modified promoter [5] |

| Gene Abundance | CysE/b3607 | 66.4 ppm | 20,632.5 ppm | Increased copy number [5] |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Constraint-Based Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Database | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Models | iML1515 | Base E. coli K-12 MG1655 model | Foundation for strain-specific modifications [5] |

| Software Packages | COBRApy | Python package for FBA simulations | Implementing FBA, FVA, and other CBM methods [5] [7] |

| Enzyme Kinetics | BRENDA | Comprehensive enzyme database | Kcat values for enzyme constraints [5] |

| Protein Data | PAXdb | Protein abundance database | Cellular enzyme concentration data [5] |

| Pathway Database | EcoCyc | E. coli genes and metabolism | GPR associations and metabolic pathways [5] |

| Optimization Solvers | Gurobi, CPLEX | Linear/nonlinear programming solvers | Solving large-scale FBA problems [8] |

Applications in E. coli Research

FBA has been successfully applied to numerous E. coli research areas:

Metabolic Engineering: Identifying gene knockout strategies to improve yields of industrial chemicals like succinate and ethanol [2]. For example, FBA can predict how disabling competing pathways redirects flux toward desired products.

Growth Phenotype Prediction: Simulating growth capabilities in different nutritional environments [2]. These predictions have shown strong correlation with experimental results [2].

Drug Target Identification: Identifying essential reactions and genes in pathogens [2]. Double deletion studies can reveal synthetic lethal interactions for multi-target therapies [2].

The following diagram illustrates a sample application for predicting gene essentiality:

Troubleshooting and Method Validation

Common challenges in constraint-based modeling and their solutions include:

Unrealistically High Flux Predictions: Address by adding enzyme constraints using tools like ECMpy to account for limited cellular protein resources [5] [6].

Incorrect Growth Predictions: Verify medium composition and check for missing transport reactions or blocked metabolites [5].

Non-Unique FBA Solutions: Perform Flux Variability Analysis to determine the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective value [8].

Method validation should include:

- Comparison of simulated growth rates with experimental measurements

- Verification of predicted essential genes against experimental knockout data

- Testing of secretion profile predictions against metabolomics data

Constraint-based modeling with steady-state assumptions provides a powerful framework for analyzing E. coli metabolism and guiding metabolic engineering efforts. The continued development of more comprehensive models and constraint integration methods promises to further enhance the predictive capabilities of this approach.

Escherichia coli is a premier model organism for studying bacterial metabolism, serving as a foundational chassis for systems biology and metabolic engineering. Its well-annotated genome and extensive biochemical characterization have enabled the development of computational models that predict metabolic capabilities under various conditions. The core metabolic network of E. coli consists of central carbon metabolism (glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, TCA cycle), biosynthesis pathways for amino acids, nucleotides, and fatty acids, and energy generation systems that work in coordination to sustain growth and reproduction [9]. Understanding this metabolic landscape is crucial for leveraging E. coli in biotechnology applications, from biochemical production to therapeutic development.

The advent of constraint-based modeling approaches, particularly flux balance analysis (FBA), has transformed our ability to interpret and manipulate E. coli metabolism. FBA utilizes genome-scale metabolic reconstructions to predict flux distributions through metabolic networks at steady state, enabling in silico simulation of metabolic capabilities without requiring extensive kinetic parameters [10] [2]. This protocol-focused article examines the key pathways of E. coli metabolism through the lens of the iML1515 genome-scale model and outlines practical methodologies for implementing FBA in E. coli research.

The iML1515 Genome-Scale Metabolic Model

Model Development and Core Features

iML1515 represents the most complete genome-scale reconstruction of E. coli K-12 MG1655 metabolism to date, building upon earlier models through extensive manual curation and integration of new biochemical knowledge. This knowledgebase accounts for 1,515 open reading frames and 2,719 metabolic reactions involving 1,192 unique metabolites, significantly expanding coverage beyond previous iterations [11] [12]. The model incorporates several key updates discovered since the publication of its predecessor iJO1366, including sulfoglycolysis, phosphonate metabolism, curcumin degradation pathways, and an expanded set of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generating reactions increased from 16 to 166 [11].

A distinctive feature of iML1515 is its integration with structural biology through links to 1,515 protein structures, creating a bridge between systems biology and structural biology [11] [12]. This enables the classic gene-protein-reaction (GPR) relationships to be characterized at catalytic domain resolution through domain-gene-protein-reaction (dGPR) relationships, providing unprecedented insight into enzyme function and promiscuity [11]. The model also incorporates transcriptional regulation information through promoter "barcodes" that indicate whether a metabolic gene is regulated by specific transcription factors and the type of regulation involved [11].

Model Validation and Performance

iML1515 has been rigorously validated through experimental genome-wide gene-knockout screens using the KEIO collection (3,892 gene knockouts) grown on 16 different carbon sources representing different substrate entry points into central carbon metabolism [11]. The model demonstrated 93.4% accuracy in predicting gene essentiality across these conditions, representing a 3.7% increase in predictive accuracy compared to iJO1366 [11]. When customized with proteomics data for E. coli K-12 MG1655 grown on seven carbon sources to create condition-specific models, iML1515 shows an average 12.7% decrease in false-positive predictions and a 2.1% increase in essentiality predictions [11].

Table 1: Key Features and Validation Metrics of iML1515

| Feature Category | Specific Elements | Count/Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | Open Reading Frames | 1,515 |

| Metabolic Reactions | 2,719 | |

| Unique Metabolites | 1,192 | |

| Model Updates | New Genes vs iJO1366 | 184 |

| New Reactions vs iJO1366 | 196 | |

| ROS-generating Reactions | 166 | |

| Validation Metrics | Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy | 93.4% |

| Reduction in False-Positives with Proteomics Data | 12.7% |

Flux Balance Analysis Methodology

Theoretical Foundation

Flux Balance Analysis is a mathematical approach for simulating metabolism using genome-scale reconstructions that leverages the stoichiometric constraints of metabolic networks. The core principle involves applying mass balance constraints to determine feasible metabolic flux distributions at steady state, represented mathematically as:

S • v = 0

where S is the m × n stoichiometric matrix (m metabolites, n reactions) and v is the vector of metabolic fluxes [10] [2]. This system is typically underdetermined, with more reactions than metabolites, requiring the application of additional constraints and optimization principles to identify a biologically relevant solution.

FBA operates under two key assumptions: the steady-state assumption, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, and the optimality assumption, where the organism has evolved to optimize a particular biological objective such as biomass production or ATP yield [2]. The solution space is further constrained by imposing capacity constraints on individual metabolic fluxes:

αi ≤ vi ≤ β_i

where αi and βi represent lower and upper bounds for each flux v_i [10]. A specific flux distribution is identified using linear programming to maximize or minimize an objective function Z = c^T v, where c is a vector defining the linear combination of fluxes to optimize [10] [2].

Computational Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the core computational workflow for implementing FBA:

Figure 1: FBA Computational Workflow. The process begins with loading a metabolic model, followed by applying constraints, setting an objective function, solving the optimization problem, and analyzing results.

Experimental Protocols for FBA in E. coli Research

Protocol 1: Gene Essentiality Prediction

Purpose: To identify metabolic genes essential for growth under specific environmental conditions.

Methodology:

- Model Preparation: Load the iML1515 model or a appropriate subnetwork (e.g., iCH360 for core metabolism studies) in a computational environment such as Python with COBRApy or MATLAB with the COBRA Toolbox [9].

- Condition Specification: Set the environmental constraints to reflect the growth condition of interest, including carbon source uptake rate (e.g., glucose at 10 mmol/gDW/h), oxygen availability (aerobic: 20 mmol/gDW/h; anaerobic: 0 mmol/gDW/h), and other nutrient limitations as needed.

- Gene Deletion Simulation: For each gene in the model:

- Evaluate the gene-protein-reaction (GPR) association to identify all reactions catalyzed by the gene product

- Constrain the fluxes through all associated reactions to zero

- Solve the linear programming problem to maximize biomass production

- Record the predicted growth rate

- Essentiality Classification: Classify a gene as essential if the predicted growth rate falls below a threshold (typically 5-10% of wild-type growth rate) [11].

- Validation: Compare predictions with experimental data from the KEIO collection gene knockout screens [11].

Applications: Identification of potential drug targets, guidance for genetic manipulation strategies, and discovery of synthetic lethal interactions.

Protocol 2: Growth-Coupled Strain Design

Purpose: To engineer E. coli strains where product formation is essential for growth.

Methodology:

- Base Strain Selection: Start with a model of an appropriate chassis strain (e.g., E. coli W3110 for metabolic engineering applications) [13].

- Pathway Integration: Add heterologous reactions for the target product to the model (e.g., dopamine synthesis pathway including hpaBC and DmDdC genes) [13].

- Constraint Implementation: Apply physiological constraints such as ATP maintenance requirements and maximum reaction fluxes based on enzyme capacity measurements.

- Optimization Algorithm Implementation:

- Use OptKnock or similar algorithms to identify reaction deletions that couple target product formation with growth

- Apply mixed-integer linear programming to solve the bilevel optimization problem

- Rank intervention strategies by predicted product yield and growth rate

- Experimental Validation: Implement top genetic modifications in the actual strain and characterize performance in bioreactor studies [13].

Applications: Development of high-y production strains for biochemicals, biofuels, and pharmaceuticals.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for E. coli FBA Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli K-12 MG1655 | Wild-type strain with complete genome sequence | Reference strain for iML1515 model validation and fundamental studies [11] |

| KEIO Collection | 3,892 single-gene knockout mutants | Experimental validation of gene essentiality predictions [11] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based modeling suite | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic models [9] |

| COBRApy | Python-based modeling package | Python implementation of constraint-based modeling methods [9] |

| iCH360 Model | Compact model of E. coli core metabolism | Reduced-scale model for efficient simulation and visualization of central metabolism [9] |

| Escher | Web-based visualization tool | Creation of interactive metabolic maps for flux visualization [9] |

Applications and Case Studies

Metabolic Engineering for Dopamine Production

A recent application of FBA-guided metabolic engineering demonstrated the development of a high-yield dopamine-producing E. coli strain. Researchers constructed a plasmid-free, defect-free E. coli W3110 strain by implementing a coordinated metabolic engineering strategy: (1) constitutive expression of the DmDdC gene from Drosophila melanogaster combined with the hpaBC gene from E. coli BL21, (2) promoter optimization to balance expression of key enzyme genes, (3) increased carbon flux through the dopamine synthesis pathway, (4) elevation of key enzyme copy number, and (5) construction of an FADH2-NADH supply module [13]. The resulting strain, DA-29, achieved a dopamine titer of 22.58 g/L in a 5L bioreactor using a two-stage pH fermentation strategy combined with Fe²⺠and ascorbic acid feeding [13].

Condition-Specific Model Customization

iML1515 can be tailored to specific growth conditions using omics data to improve prediction accuracy. The protocol involves:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain transcriptomics or proteomics data for E. coli under the condition of interest

- Reaction Removal: Remove reactions catalyzed by gene products not expressed in the specific condition

- GPR Modification: Adjust gene-protein-reaction associations based on expression patterns

- Validation: Compare prediction accuracy before and after customization [11]

This approach has been shown to decrease false-positive predictions by 12.7% while increasing essentiality prediction accuracy by 2.1% [11].

Advanced Analysis Techniques

Phenotypic Phase Plane Analysis

Phenotypic Phase Plane (PhPP) analysis involves systematically varying two substrate uptake rates (e.g., carbon and oxygen) and calculating the optimal growth rate for each combination to identify phases of qualitatively different metabolic behavior [10]. The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework for PhPP analysis:

Figure 2: PhPP Analysis Workflow. This technique maps metabolic phases as functions of substrate uptake rates.

Multi-Strain Metabolic Analysis

iML1515 enables comparative analysis across different E. coli strains. Researchers have used the model to build metabolic models for E. coli clinical isolates and human gut microbiome strains from metagenomic sequencing data [11] [12]. By using bi-directional BLAST and genome context to search for metabolic genes present in iML1515 across 1,122 sequenced strains of E. coli and Shigella, a conserved core metabolic network for the species has been defined [11]. This approach facilitates the identification of strain-specific metabolic capabilities and vulnerabilities that could be exploited for targeted antimicrobial therapies.

The integration of comprehensive metabolic models like iML1515 with constraint-based analysis methods represents a powerful framework for understanding and manipulating E. coli metabolism. The protocols outlined in this article provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing FBA in diverse research contexts, from basic metabolic studies to applied metabolic engineering projects. As modeling approaches continue to evolve through integration with machine learning, kinetic modeling, and multi-omics data integration [14], the predictive power and application scope of these methods will further expand, solidifying E. coli's role as a model organism for systems metabolic engineering.

Stoichiometric Matrices, Mass Conservation, and Thermodynamic Constraints

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a fundamental mathematical approach for simulating the metabolism of cells, including the model organism Escherichia coli. This constraint-based modeling method leverages genome-scale metabolic reconstructions to predict metabolic fluxes without requiring extensive kinetic parameter data. FBA operates on the principle of mass conservation, formalized through stoichiometric matrices, and can be enhanced by incorporating thermodynamic constraints to improve biological realism [2] [15]. For E. coli researchers, these methods provide powerful tools for predicting growth rates, identifying essential genes, optimizing bioproduction, and designing novel culture media [5] [16]. This protocol details the practical application of these concepts within the context of a broader thesis on FBA methodology for E. coli research, providing researchers with structured frameworks for implementing these analyses in both standard and advanced scenarios.

Theoretical Foundations

The Stoichiometric Matrix and Mass Balance

The core structural component of any metabolic model is the stoichiometric matrix S, which mathematically represents the network of biochemical reactions within a cell.

- Matrix Composition: In a stoichiometric matrix of dimensions ( m \times n ), each of the ( m ) rows corresponds to a unique metabolite, and each of the ( n ) columns represents a biochemical reaction. The entry ( S_{ij} ) specifies the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite ( i ) in reaction ( j ), with negative values indicating substrate consumption and positive values indicating product formation [17].

Mass Balance Equations: Under the steady-state assumption, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, the system is described by the differential equation:

( \frac{dx}{dt} = S \cdot v = 0 )

Here, ( v ) is the vector of reaction fluxes (reaction rates), and the equation dictates that for each metabolite, the net sum of its production and consumption fluxes must equal zero [2] [17]. This equation encapsulates the principle of mass conservation within the network.

Thermodynamic Constraints

Thermodynamic constraints introduce reaction directionality based on energy considerations, moving predictions closer to biological feasibility.

- Irreversibility Enforcement: A subset of reactions ( T \subseteq N ) is identified as thermodynamically irreversible under physiological conditions. In the model, this is implemented by constraining their fluxes to be non-negative: ( v_j \geq 0 ) for all ( j \in T ) [18].

- Energy Balance Analysis: Beyond simple irreversibility, Energy Balance Analysis (EBA) uses the principles of non-equilibrium thermodynamics to provide additional system constraints. The network structure alone can impose thermodynamic feasibility constraints on flux distributions, which can be analyzed by comparing the sign pattern of the flux vector with the sign patterns of the network's cycles [15].

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Performing Basic FBA forE. coli

This protocol outlines the fundamental steps to set up and run a basic FBA simulation to predict the growth rate of E. coli.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential components for FBA of E. coli metabolism

| Component | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | A structured, computational representation of metabolism. Provides the stoichiometric matrix (S). | iML1515 [9] [5] [19] |

| Software Environment | Programming environment and toolboxes for constraint-based modeling. | Python with COBRApy [5] [19] |

| Linear Programming (LP) Solver | Computational engine to solve the optimization problem. | GLPK or commercial alternatives (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX) [20] |

| Nutrient Uptake Constraints | Defines the available nutrients in the growth medium, setting upper bounds for exchange reactions. | e.g., Glucose: -10 mmol/gDW/hr [19] |

| Objective Function (c) | The reaction flux to be maximized or minimized; typically biomass production for growth simulations. | Core biomass reaction in iML1515 [19] |

| Maintenance Energy | Parameters accounting for energy used for cellular processes not directly related to growth. | GAM: 59.8 mmol gDCWâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹; NGAM: 8.4 mmol gDCWâ»Â¹ hâ»Â¹ [19] |

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Model Acquisition and Import: Download a curated genome-scale metabolic model for E. coli, such as iML1515 [9] [5]. Import the model into your computational environment using a package like COBRApy.

- Medium Configuration: Define the growth medium by setting the upper and lower bounds of the exchange reactions for extracellular metabolites. For a minimal medium with glucose, you would set the lower bound of the glucose exchange reaction (e.g.,

EX_glc__D_e) to a negative value (e.g.,-10) to allow uptake, while setting the bounds for other carbon sources to zero [20] [19]. - Objective Definition: Set the objective function to maximize the flux through the biomass reaction. In COBRApy, this is typically done with the

model.objective = 'BIOMASS_Ec_iML1515_core_75p37M'command [19]. - Thermodynamic Constraining: Ensure the model's irreversibility constraints are correctly applied. Most modern models come with these pre-defined, but they can be reviewed and modified based on thermodynamic data [18] [15].

- Problem Solution: Use the

model.optimize()function in COBRApy to solve the linear programming problem and obtain the growth rate and flux distribution. - Result Visualization and Analysis: Analyze the resulting flux vector. Tools like Escher-FBA can be used to visualize the flux distribution on a metabolic map, where the thickness of reaction arrows is proportional to the flux value [20].

Protocol 2: Incorporating Thermodynamic and Enzyme Constraints

This protocol describes how to add layers of thermodynamic and enzyme capacity constraints to an existing FBA model to increase the predictive accuracy for engineered E. coli strains.

Key Parameters for Advanced FBA

Table 2: Key parameters for thermodynamically- and enzyme-constrained FBA

| Parameter | Role in Constraining Model | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Directionality | Enforces thermodynamic feasibility by blocking flux in infeasible directions. | Model annotation, literature [18], TECR database |

| Turnover Number (Kcat) | Defines the maximum catalytic rate of an enzyme, capping the flux per enzyme unit. | BRENDA database [5] |

| Enzyme Molecular Weight | Used with Kcat to convert flux constraints into enzyme mass constraints. | UniProt, EcoCyc [5] |

| Protein Abundance | Provides a global constraint on the total mass of enzyme available. | PAXdb [5] |

| Protein Fraction | The fraction of total cell dry weight that is protein; a key global constraint. | Literature (e.g., 0.56 for E. coli) [5] |

Workflow for Constraint Integration

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Implement Thermodynamic Constraints: Verify and, if necessary, curate the directionality of reactions in the model. This often involves setting the lower bound of known irreversible reactions to zero. Extreme Semipositive Conservation Relations (ESCRs) can be analyzed to identify thermodynamically feasible flux configurations [18].

- Prepare Kinetic Data: For enzyme constraints, gather data. This includes:

- Kcat values from the BRENDA database.

- Enzyme molecular weights from EcoCyc or UniProt.

- Protein abundance data from PAXdb [5].

- Split Reversible Reactions: For the enzyme-constrained model (ecModel), split all reversible reactions into separate forward and reverse reactions to assign distinct Kcat values [5].

- Integrate Enzyme Constraints: Use a workflow like ECMpy to integrate the collected data into the model. This adds a constraint that the total enzyme mass, calculated from the fluxes and their associated Kcats and molecular weights, cannot exceed the measured total protein mass of the cell [5].

- Validate and Simulate: Test the constrained model by simulating growth under different conditions and compare predictions to experimental data to ensure the constraints improve model performance without over-constraining feasible behaviors.

Advanced Applications

Prediction of Minimal Nutrient Media

The producibility of biomass or a target metabolite can be systematically analyzed by examining the network's conservation relations.

- Theory: A biochemical species is producible if a feasible steady-state flux configuration exists that sustains its non-zero concentration. This is intrinsically linked to the ESCRs of the network. A species is weakly producible if and only if every ESCR that contains it also contains at least one species available in the nutrient media [18].

- Application: This relationship was used to analyze the E. coli iJR904 model. By traversing its 51 anhydrous ESCRs, the algorithm identified 928 minimal aqueous nutrient sets that theoretically support biomass production. After applying thermodynamic constraints, 287 of these sets were found to be feasible, providing testable hypotheses for alternate E. coli growth media [18].

Dynamic FBA for Bioprocess Evaluation

Dynamic FBA (dFBA) extends FBA to time-varying systems like batch and fed-batch cultures, allowing for more realistic simulation of bioproduction processes.

- Methodology: dFBA couples the steady-state metabolic model with ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the time-dependent changes in extracellular substrate and product concentrations, as well as biomass growth [16].

- Case Study - Shikimic Acid Production: dFBA was applied to evaluate a high-producing E. coli strain. Experimental time-course data for glucose and biomass were approximated with polynomial functions. These approximations were differentiated and used to constrain sequential FBA simulations across the cultivation time. The simulation revealed that the experimental strain achieved a shikimic acid titer that was 84% of the theoretical maximum predicted by dFBA under the same substrate consumption and growth constraints, quantitatively evaluating the success of the metabolic engineering effort [16].

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Infeasible Solutions: If an FBA problem returns "infeasible," check for consistency in the medium constraints and reaction directionalities. A common error is a "loop" where a metabolite is produced but cannot be consumed, or vice versa, which violates the steady-state condition when all reactions are irreversible [20].

- Unrealistically High Fluxes: If the model predicts physiologically impossible flux values, consider implementing enzyme constraints as detailed in Protocol 3.2. This explicitly accounts for the proteomic cost of metabolism and prevents solutions that would require more catalytic capacity than the cell can provide [5].

- Validation is Critical: Always validate model predictions against experimental data where possible. Key validations include comparing predicted versus experimental growth rates on different carbon sources and assessing the accuracy of gene essentiality predictions [19].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a fundamental mathematical approach for simulating metabolism in Escherichia coli and other microorganisms at the genome-scale [21] [2]. As a constraint-based method, FBA calculates the flow of metabolites through a metabolic network to predict phenotypic behaviors such as growth rates or chemical production [21]. The core principle of FBA involves solving a system of linear equations representing metabolic reactions under the steady-state assumption, where metabolite concentrations remain constant because production and consumption rates are balanced [2]. The system is mathematically represented as S∙v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix containing the coefficients of each metabolite in every reaction, and v is the vector of metabolic fluxes [21] [2].

Unlike kinetic models that require extensive parameterization, FBA achieves predictive power through the judicious application of constraints that define the solution space for feasible flux distributions [21]. Among these constraints, the definition of system boundaries represents perhaps the most critical implementation step, as it directly determines the interaction between the metabolic model and its simulated environment. Proper boundary definition encompasses three essential components: (1) uptake reactions that govern nutrient availability; (2) export reactions that enable product secretion and waste elimination; and (3) biomass formation reactions that represent the metabolic requirements for cellular growth and replication. This protocol details the theoretical foundation and practical implementation for defining these system boundaries in genome-scale metabolic models of E. coli, providing researchers with a standardized framework for constructing physiologically relevant FBA simulations.

Defining Uptake and Export Reactions

Theoretical Basis for Environmental Boundary Definition

Uptake and export reactions serve as the interface between the metabolic network and its extracellular environment. In FBA formalism, these exchange reactions are typically represented as unidirectional or bidirectional fluxes that transport metabolites across the system boundary [2]. Uptake reactions control the influx of nutrients, substrates, and essential cofactors, while export reactions manage the efflux of metabolic products, by-products, and waste compounds. Proper definition of these exchange fluxes is essential for creating biologically meaningful simulations, as they directly determine the nutritional landscape and metabolic capabilities of the modeled organism.

The implementation of exchange reactions involves setting appropriate flux constraints (upper and lower bounds) that define the directionality and capacity of metabolite transport. For uptake reactions, these bounds typically allow only negative flux (into the network), while export reactions permit only positive flux (out of the network) [22]. The specific values for these constraints can be derived from experimental measurements of substrate consumption rates or product secretion rates, or can be set to theoretically maximum values to explore network capacity.

Protocol: Implementing Experimentally Relevant Uptake Constraints

Objective: Define physiologically relevant uptake constraints for E. coli FBA simulations under specific growth conditions.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model of E. coli (e.g., iJO1366 or iML1515)

- Linear programming solver (e.g., COBRA Toolbox, PyFBA)

- Growth medium composition data

- Experimentally measured substrate uptake rates (if available)

Procedure:

Identify Essential Nutrients: Determine which nutrients must be included based on the simulated growth medium. For standard E. coli cultivation, this typically includes:

- A carbon source (e.g., glucose, glycerol, acetate)

- Nitrogen source (e.g., ammonium)

- Phosphorus source (e.g., phosphate)

- Sulfur source (e.g., sulfate)

- Oxygen (for aerobic conditions)

- Essential minerals and cofactors

Set Uptake Flux Bounds: Apply constraints to the corresponding exchange reactions in the model:

- For the primary carbon source, set an upper bound based on experimental measurements. For example, with glucose as the carbon source:

EX_glc__D_e ≤ -10 mmol/gDW/h[22] - For other essential nutrients, set upper bounds to allow unlimited uptake (unless specific limitations are being modeled):

EX_nh4_e ≤ -1000 mmol/gDW/h - For non-essential or absent nutrients, set the exchange reaction to zero:

EX_lac__D_e = 0

- For the primary carbon source, set an upper bound based on experimental measurements. For example, with glucose as the carbon source:

Validate Nutrient Sufficiency: Perform FBA with biomass production as the objective function to verify that the defined uptake constraints support growth. If no growth is predicted, identify potentially missing essential nutrients or gaps in the metabolic network.

Table 1: Example Uptake Reaction Constraints for E. coli in Minimal Glucose Medium

| Metabolite | Reaction Identifier | Upper Bound (mmol/gDW/h) | Lower Bound (mmol/gDW/h) | Basis for Constraint |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Glucose | EXglcDe | -10.0 | 0.0 | Experimental measurement [22] |

| Ammonium | EXnh4e | -1000.0 | 0.0 | Non-limiting |

| Phosphate | EXpie | -1000.0 | 0.0 | Non-limiting |

| Oxygen | EXo2e | -18.0 | 0.0 | Aeration capacity |

| Sulfate | EXso4e | -1000.0 | 0.0 | Non-limiting |

Protocol: Configuring Export Reactions for Metabolic By-Products

Objective: Implement appropriate export constraints for metabolic products and by-products.

Procedure:

Identify Potential Excreted Metabolites: Based on the metabolic capabilities of E. coli and the specific growth conditions, identify metabolites that may be secreted. Common examples include:

- Carbon dioxide (

EX_co2_e) - Acetate (

EX_ac_e) - particularly under overflow metabolism conditions [23] - Ethanol (

EX_etoh_e) - Succinate (

EX_succ_e) - Water (

EX_h2o_e) - Proton (

EX_h_e)

- Carbon dioxide (

Set Export Flux Bounds: Configure constraints to allow metabolite secretion:

- For common metabolic by-products like COâ‚‚ and water, allow unlimited export:

EX_co2_e ≥ 0 - For fermentative products like acetate, allow secretion under appropriate conditions:

EX_ac_e ≥ 0 - For metabolites not produced or secreted in the simulated condition, set the export flux to zero

- For common metabolic by-products like COâ‚‚ and water, allow unlimited export:

Validate Metabolic Functionality: Perform FBA simulations and check flux variability analysis (FVA) to ensure that export reactions allow for proper metabolic function and by-product secretion where physiologically relevant.

Table 2: Example Export Reaction Constraints for E. coli Under Aerobic Conditions

| Metabolite | Reaction Identifier | Upper Bound (mmol/gDW/h) | Lower Bound (mmol/gDW/h) | Physiological Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Dioxide | EXco2e | 1000.0 | 0.0 | Respiratory by-product |

| Acetate | EXace | 1000.0 | 0.0 | Overflow metabolism [23] |

| Ethanol | EXetohe | 1000.0 | 0.0 | Fermentation product |

| Water | EXh2oe | 1000.0 | 0.0 | Metabolic water |

| Proton | EXhe | 1000.0 | -1000.0 | pH balance |

Implementing Biomass Formation Reactions

Theoretical Foundation of Biomass Representation

The biomass formation reaction represents the metabolic cost of cellular growth by combining all essential biomass precursors in their appropriate stoichiometric ratios [21] [2]. This pseudo-reaction serves as the primary objective function in most FBA simulations of microbial growth, with the flux through this reaction corresponding to the exponential growth rate (μ) of the organism [21]. The biomass reaction effectively "drains" metabolic precursors from the system, simulating their incorporation into cellular components during growth and division.

A properly defined biomass reaction must account for the major macromolecular components of the cell, including:

- Amino acids for protein synthesis

- Nucleotides for DNA and RNA synthesis

- Lipids for membrane biosynthesis

- Carbohydrates for cell wall and glycogen

- Cofactors and essential metabolites

- Energy requirements for macromolecular assembly

Different E. coli models may contain variations of biomass reactions tailored for specific conditions. For example, the iJO1366 model includes both "core" and "wild-type" biomass reactions, with the wild-type version containing precursors for all typical cellular components [22].

Protocol: Configuring and Validating Biomass Reactions

Objective: Implement and validate an appropriate biomass reaction for E. coli FBA simulations.

Procedure:

Select Appropriate Biomass Formulation: Choose a biomass reaction appropriate for your E. coli strain and growth conditions. Common options include:

- "BiomassEcolicore" for basic simulations

- "BiomassEcolimW" or "BiomassEcolimN" for condition-specific simulations

Set as Objective Function: Designate the biomass reaction as the objective function to be maximized during FBA:

Validate Biomass Composition: Verify that the biomass reaction accounts for all major cellular components in physiologically relevant proportions. The reaction should drain precursors at rates proportional to their cellular abundance.

Test Growth Predictions: Perform FBA under different nutrient conditions to verify that the model produces biologically reasonable growth predictions. Compare with experimental growth data when available.

Table 3: Major Components of a Typical E. coli Biomass Reaction

| Biomass Component | Representative Precursors | Stoichiometric Coefficient (mmol/gDW) | Cellular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | 20 amino acids | Varies by amino acid | Enzymes, structure |

| RNA | ATP, GTP, CTP, UTP | Varies by nucleotide | Gene expression |

| DNA | dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP | Varies by nucleotide | Genetic information |

| Lipids | Phospholipids, fatty acids | Varies by lipid class | Membrane structure |

| Cell Wall | UDP-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine | ~0.27 | Structural integrity |

| Cofactors | NAD, ATP, CoA | Varies by cofactor | Metabolic catalysis |

Integrated Workflow and Experimental Design

Comprehensive Protocol: System Boundary Definition for FBA

Objective: Implement a complete system boundary definition for E. coli FBA simulations.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model of E. coli

- COBRA Toolbox or PyFBA [24]

- Growth condition specifications

- Experimental flux data (for validation)

Procedure:

Model Initialization: Load the base metabolic model and remove any existing medium definitions or boundary constraints.

Uptake Reaction Configuration:

- Define the carbon source uptake rate based on experimental conditions

- Set unlimited uptake for essential nutrients (N, P, S sources)

- Block uptake of metabolites absent from the growth medium

- Configure oxygen uptake for aerobic/anaerobic conditions

Export Reaction Configuration:

- Allow unlimited export of metabolic waste products (COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O)

- Enable secretion of relevant metabolic by-products (acetate, ethanol)

- Set appropriate proton exchange for pH balance

Biomass Reaction Setup:

- Select and verify the appropriate biomass reaction

- Set as the objective function for growth simulations

- Validate biomass composition against literature values

Model Validation:

- Perform FBA to verify growth prediction

- Conduct flux variability analysis (FVA) to assess solution space

- Compare predicted exchange fluxes with experimental data

- Test gene essentiality predictions against known auxotrophies

Diagram 1: System Boundary Definition Workflow. This workflow outlines the sequential process for defining uptake, export, and biomass reactions in E. coli FBA models.

Advanced Application: Dynamic FBA for Changing Environments

For simulations involving changing environments (e.g., nutrient shifts or batch culture), Dynamic FBA extends the standard approach by incorporating time-dependent changes to system boundaries [25]. This method is particularly useful for modeling phenomena such as diauxic growth in E. coli, where sequential utilization of carbon sources occurs.

Implementation Steps:

- Initialize system boundaries for initial conditions

- Perform FBA to determine growth and metabolic fluxes

- Update extracellular metabolite concentrations based on predicted uptake/secretion

- Modify uptake bounds to reflect concentration changes

- Repeat steps 2-4 for each time point

Diagram 2: Dynamic FBA Process for Changing Environments. This iterative process allows modeling of time-dependent phenomena like nutrient shifts and diauxic growth.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for E. coli FBA Studies

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Sources/Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling [21] | https://opencobra.github.io/cobratoolbox/ |

| PyFBA | Python-based FBA package for metabolic model construction and simulation [24] | http://linsalrob.github.io/PyFBA/ |

| Model SEED Biochemistry Database | Comprehensive reaction database for metabolic model reconstruction [24] | https://modelseed.org/ |

| RAST Annotation Server | Genome annotation service for identifying metabolic genes [24] | http://rast.nmpdr.org/ |

| EcoCyc Database | Curated E. coli metabolic database with regulatory information [26] | https://ecocyc.org/ |

| iJO1366 Metabolic Model | Genome-scale E. coli metabolic model with 2583 reactions [22] | http://systemsbiology.ucsd.edu/InSilicoOrganisms/E_coli |

| GLPK (GNU Linear Programming Kit) | Open-source linear programming solver for FBA [24] | https://www.gnu.org/software/glpk/ |

| IBM ILOG CPLEX | Commercial optimization solver for large-scale FBA problems [24] | https://www.ibm.com/analytics/cplex-optimizer |

Proper definition of system boundaries represents a foundational step in constructing physiologically relevant FBA models of E. coli metabolism. Through the precise implementation of uptake reactions, export reactions, and biomass formation constraints, researchers can create in silico representations that accurately capture the metabolic capabilities and limitations of this model organism. The protocols presented here provide a standardized framework for boundary definition that supports reproducible and biologically meaningful simulations across diverse research applications, from basic metabolic studies to strain engineering for bioproduction.

As FBA methodologies continue to evolve, incorporating additional layers of biological complexity such as proteomic constraints [23] and transcriptional regulation [26], the accurate definition of system boundaries becomes increasingly critical. By adhering to these established protocols and leveraging the available toolkit of resources, researchers can ensure that their E. coli FBA models provide maximum insight into the intricate relationship between genotype, environment, and metabolic phenotype.

A Step-by-Step FBA Protocol for E. coli: From Model Setup to Simulation

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are structured knowledgebases that provide a mathematical representation of an organism's metabolism. For Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655, the most complete GEM available is iML1515, a comprehensive reconstruction that serves as an invaluable tool for predicting cellular phenotypes through computational methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [11]. This model significantly expands upon its predecessor, iJO1366, by incorporating newly characterized genes, metabolic functions, and updated biochemical data, making it the most accurate representation of E. coli K-12 metabolism to date [11].

iML1515 accounts for 1,515 open reading frames and 2,719 metabolic reactions involving 1,192 unique metabolites [11] [5]. A key advancement in iML1515 is its integration with structural biology; the model is linked to 1,515 protein structures, providing an integrated framework that bridges systems biology and structural biology [11]. This connection enables researchers to characterize gene-protein-reaction (GPR) relationships at catalytic domain resolution, offering unprecedented insight into enzymatic functions and the effects of sequence variations [11].

Table: Key Metrics of the iML1515 Genome-Scale Metabolic Model

| Model Component | Count | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Open Reading Frames | 1,515 | Genes included in the metabolic network |

| Metabolic Reactions | 2,719 | Biochemical transformations in the network |

| Unique Metabolites | 1,192 | Distinct chemical species in the network |

| Protein Structures | 1,515 | Linked protein structures (716 crystal structures + 799 homology models) |

The model incorporates several types of content not present in previous reconstructions, including updated metabolism of reactive oxygen species (ROS), metabolite repair pathways, and newly reported metabolic functions such as sulfoglycolysis, phosphonate metabolism, and curcumin degradation [11]. Furthermore, iML1515 includes regulatory information through promoter "barcodes" that indicate whether a metabolic gene is regulated by specific transcription factors and the type of regulation (activator, repressor, or unknown) [11].

Validation of iML1515 against experimental genome-wide gene-knockout screens across 16 different carbon sources demonstrated a 93.4% accuracy in predicting gene essentiality, representing a 3.7% increase in predictive accuracy compared to the iJO1366 model [11]. This enhanced performance makes iML1515 particularly valuable for metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and fundamental research in bacterial physiology.

Model Acquisition and Curation

Obtaining the Model

The iML1515 model is publicly available through the BiGG Models database (http://bigg.ucsd.edu/models/iML1515), a curated resource of genome-scale metabolic models [27]. From this repository, researchers can download the model in multiple standard formats compatible with most constraint-based modeling software:

- SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language): The model is available as iML1515.xml (also in compressed .xml.gz format), which is the most widely supported format for systems biology models [27].

- JSON (JavaScript Object Notation): The iML1515.json file provides a format easily readable by web applications and modern programming languages [27].

- MAT (MATLAB): The iML1515.mat file enables seamless integration with MATLAB-based tools like the COBRA Toolbox [27].

These standardized formats ensure interoperability across various computational platforms and operating systems, facilitating widespread adoption in the research community.

Strain-Specific Considerations

While iML1515 is specifically designed for E. coli K-12 MG1655, researchers often work with closely related K-12 derivatives such as BW25113 (the parent strain of the Keio collection) [5]. When applying iML1515 to these strains, it is important to recognize that while the core metabolic pathways remain consistent, genetic differences may exist in the form of specific gene deletions or allele variations [5].

For studies requiring modeling of other E. coli strains, iML1515 can serve as a template for constructing strain-specific models. The publication describing iML1515 details methods for establishing a core metabolic network for the species by using bi-directional BLAST and genome context to search for metabolic genes present in iML1515 across 1,122 sequenced strains of E. coli and Shigella [11]. Genes not present in more than 99% of strains can be removed to form a model of conserved "core" E. coli metabolic capabilities [11].

Addressing Gaps and Inconsistencies

During model curation, researchers should be aware of potential gaps or inconsistencies that may require manual correction:

- Database Inconsistencies: The ECMpy workflow has identified errors in iML1515 related to Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) relationships and reaction directions when compared to the EcoCyc database [5]. These should be verified and corrected based on the most current biochemical knowledge.

- Missing Reactions: For specialized applications, certain reactions may be missing from iML1515. For instance, in L-cysteine production studies, the O-acetyl-L-serine sulfhydrylase and S-sulfo-L-cysteine sulfite lyase reaction pathways involved in thiosulfate assimilation were found to be absent and required addition through gap-filling methods [5].

- Mass Balance Issues: When curating universal biochemical networks derived from iML1515, optimization-based methods can be employed to check for generation of "free mass" through imbalanced reactions or mass-generating loops [28].

Table: Common Model Curation Steps and Solutions

| Curation Challenge | Recommended Approach | Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|

| GPR/Reaction Direction Errors | Validate against EcoCyc database | EcoCyc, BiGG Models |

| Missing Metabolic Reactions | Use gap-filling methods | ModelSEED, CarveMe |

| Mass Balance Issues | Optimization-based free-mass checking | COBRA Toolbox, COBRApy |

| Strain-Specific Adaptation | Bi-directional BLAST analysis | BLAST, BioPython |

Protocols for Fundamental Analyses

Gene Essentiality Prediction

Predicting gene essentiality is a fundamental application of genome-scale models that helps identify potential drug targets and understand core metabolic functions. The following protocol outlines the process using iML1515:

Materials:

- iML1515 model in SBML, JSON, or MAT format

- Constraint-based modeling software (COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB or COBRApy for Python)

- Growth medium definition

- Computational environment capable of solving linear programming problems

Method:

- Load the Model and Set Constraints: Import the iML1515 model into your chosen modeling environment. Define the growth medium by setting appropriate upper and lower bounds on exchange reactions. For example, for minimal glucose medium, set the glucose exchange reaction (EXglcDe) to allow uptake while constraining other carbon sources.

Establish Baseline Growth: Calculate the wild-type growth rate by setting the biomass reaction (BIOMASSEciML1515core75p37M) as the objective function and performing FBA. This serves as a reference for evaluating the impact of gene deletions.

Simulate Gene Deletions: For each gene in the model, create a simulation where the gene is knocked out. In practice, this involves constraining all reactions associated with that gene to zero flux. The COBRA Toolbox provides functions such as

singleGeneDeletionthat automate this process.Analyze Results: Compare the predicted growth rate of each deletion strain to the wild-type growth. A gene is typically classified as essential if the deletion results in a growth rate below a predetermined threshold (e.g., <1% of wild-type growth).

Validation: Compare predictions with experimental data from the Keio collection, which contains 3,892 single-gene knockouts of E. coli K-12 BW25113 [11]. iML1515 has been validated against growth data from 16 different carbon sources, achieving 93.4% accuracy in essentiality prediction [11].

Troubleshooting:

- If the model predicts no growth even for wild-type, verify that nutrient uptake reactions are properly constrained.

- If essentiality predictions seem inaccurate for specific pathways, check for missing alternative pathways or incorrect GPR associations.

- Consider using condition-specific models constrained with transcriptomics or proteomics data to reduce false-positive predictions [11].

Gene essentiality prediction workflow using iML1515.

Understanding metabolic capabilities across different nutrient conditions is essential for both basic research and biotechnological applications. This protocol describes how to use iML1515 to simulate growth on alternative carbon sources:

Materials:

- iML1515 model

- Modeling software with FBA capability (COBRA Toolbox, COBRApy, or web-based tools like Escher-FBA)

- Definition of minimal medium composition

Method:

- Load Model and Medium: Import iML1515 and configure a minimal medium. By default, the core E. coli model in Escher-FBA uses D-glucose as the carbon source [29].

Modify Carbon Source: To switch to an alternative carbon source (e.g., succinate), identify the corresponding exchange reaction (EXsucce for succinate) and modify its lower bound to allow uptake (e.g., -10 mmol/gDW/hr) [29]. Simultaneously, constrain the glucose exchange reaction (EXglce) to zero to prevent glucose uptake.

Calculate Growth Rate: With biomass production as the objective function, perform FBA to determine the maximum growth rate on the new carbon source. For example, when switching from glucose to succinate, the predicted growth rate decreases from 0.874 hâ»Â¹ to 0.398 hâ»Â¹, reflecting the lower growth yield of E. coli on succinate [29].

Analyze Flux Redistribution: Examine how metabolic fluxes are redistributed in central carbon metabolism between the different conditions. Tools like Escher-FBA provide immediate visualization of flux changes [29].

Experimental Validation: Compare predictions with experimental growth data. iML1515 has been validated against growth profiles on 16 different carbon sources, including lag time, maximum growth rate, and growth saturation point [11].

Applications:

- Predicting substrate utilization capabilities for metabolic engineering

- Understanding adaptive metabolic responses

- Identifying nutritional requirements for different strains

Advanced Applications and Integration

Incorporating Enzyme Constraints

Standard FBA can predict unrealistically high metabolic fluxes because it doesn't account for enzyme kinetics and capacity limitations. The ECMpy workflow provides a method for integrating enzyme constraints into iML1515:

Materials:

- iML1515 model

- ECMpy package for enzyme-constrained modeling

- Enzyme kinetic data (Kcat values from BRENDA database)

- Protein abundance data (from PAXdb or experimental measurements)

- Molecular weights of enzyme subunits (from EcoCyc)

Method:

- Prepare the Model: Split all reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions to assign separate Kcat values. Similarly, split reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions, as they may have different kinetic parameters [5].

Collect Enzyme Data: Obtain Kcat values from the BRENDA database and protein abundance data from PAXdb. Set the total protein fraction available for metabolism (typically ~0.56 based on literature values) [5].

Modify Engineered Enzymes: For metabolic engineering applications, modify Kcat values and gene abundances to reflect genetic modifications. For example, when modeling L-cysteine overproduction, the Kcat for PGCD (phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase) can be increased from 20 1/s to 2000 1/s to reflect removal of feedback inhibition [5].

Account for Limitations: Note that transport reactions often lack kinetic data in databases and may need to be handled separately or assumed unconstrained [5].

Perform constrained FBA: Solve the optimization problem with the additional enzyme capacity constraints to obtain more realistic flux predictions.

Integration with Kinetic Models and Machine Learning

For advanced applications, iML1515 can be integrated with other modeling approaches to capture dynamic behaviors and improve predictive accuracy:

Hybrid Kinetic-FBA Modeling: A novel strategy integrates kinetic pathway models with iML1515 to simulate host-pathway dynamics [30]. This approach combines the local nonlinear dynamics of pathway enzymes and metabolites with the global metabolic state predicted by FBA. Machine learning surrogate models can replace FBA calculations to achieve simulation speed-ups of at least two orders of magnitude [30].

Machine Learning Enhancement: FlowGAT is a hybrid approach that combines FBA solutions from iML1515 with graph neural networks (GNNs) to predict gene essentiality [31]. This method represents metabolic fluxes as a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) where nodes correspond to enzymatic reactions and edges represent metabolite flow between reactions [31]. The GNN is then trained on knockout fitness data to predict essential genes directly from wild-type metabolic phenotypes, potentially overcoming limitations of the optimality assumption in traditional FBA [31].

Visualization and Interactive Analysis

Visualization is crucial for interpreting the complex results generated from genome-scale models. Escher-FBA provides a web-based platform for interactive FBA simulations with iML1515:

Materials:

- Web browser with JavaScript support

- Escher-FBA application (https://sbrg.github.io/escher-fba)

- iML1515 model in JSON format (available from BiGG Models)

Method:

- Access the Tool: Navigate to the Escher-FBA website. The application loads with a core model of central glucose metabolism in E. coli K-12 MG1655 by default [29].

Load Custom Model: For full-scale analysis, upload iML1515 in JSON format using the upload functionality. The model can be converted to JSON from SBML using COBRApy if needed [29].

Interactive Simulation: Hover over any reaction in the pathway map to access tooltip controls. These allow modification of flux bounds, reaction knockouts, and objective functions with immediate visual feedback [29].

Scenario Testing:

- Anaerobic Growth: Simulate anaerobic conditions by knocking out the oxygen exchange reaction (EXo2e) [29].

- Compound Objectives: Use the "Compound Objectives" mode to set multiple objectives, such as maximizing growth while minimizing flux through specific reactions [29].

- Metabolic Yields: Determine maximum yields of metabolites by setting appropriate objectives (e.g., maximize ATP production through the ATP maintenance reaction) [29].

Interactive analysis workflow using Escher-FBA.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for iML1515-Based Research

| Resource | Type | Function | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| iML1515 Model | Metabolic Reconstruction | Base model for FBA simulations | BiGG Models (bigg.ucsd.edu) |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Package | MATLAB-based FBA simulation | Open Source (opencobra.github.io) |

| COBRApy | Software Package | Python-based FBA simulation | Open Source (opencobra.github.io) |

| Escher-FBA | Web Application | Interactive FBA visualization | https://sbrg.github.io/escher-fba |

| BRENDA Database | Kinetic Data | Enzyme Kcat values for constraint-based modeling | brenda-enzymes.org |

| PAXdb | Protein Abundance Data | Protein abundance data for enzyme constraints | pax-db.org |

| EcoCyc | Biochemical Database | Curated information on E. coli genes, metabolism, and regulation | ecocyc.org |

| Keio Collection | Experimental Data | Gene knockout strains for model validation | Multiple repositories |

iML1515 represents the most comprehensive and accurate genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of E. coli K-12 MG1655 available to date. Its extensive curation, inclusion of newly discovered metabolic functions, and integration with structural biology data make it an indispensable resource for researchers studying bacterial metabolism. The protocols outlined in this application note provide a foundation for utilizing iML1515 in diverse research contexts, from basic investigations of gene essentiality to advanced metabolic engineering designs.

By following the curated workflows for model acquisition, gap-filling, constraint incorporation, and visual analysis, researchers can leverage the full potential of iML1515 to generate testable hypotheses and guide experimental design. The continued development of tools that integrate iML1515 with kinetic modeling and machine learning approaches promises to further enhance its predictive capabilities and applications across microbiology, biotechnology, and drug development.

In flux balance analysis (FBA) of E. coli and other microorganisms, the accurate definition of environmental conditions through medium composition and uptake reaction bounds is fundamental to predicting physiological behavior. FBA is a constraint-based method that computes metabolic fluxes at steady state, requiring researchers to mathematically define the organism's environment by setting constraints on exchange reactions that represent metabolite uptake and secretion [21]. Unlike kinetic models that incorporate metabolite concentrations, FBA operates entirely on flux constraints, where upper and lower bounds on reactions define the allowable solution space [4] [21]. The conversion from extracellular concentrations to uptake flux bounds represents a critical limitation in classical FBA, as there is no simple relationship between concentration measurements and the flux constraints needed for simulations [32].

The growth medium in FBA simulations is implemented by setting upper bounds on exchange reactions representing metabolite import. By default, these bounds are often set to unrealistically high values (e.g., 1000 mmol/gDW/hr) for metabolites present in the medium, while constraints for absent metabolites are set to zero [33]. This approach effectively defines the nutritional environment without requiring precise kinetic parameters, though it necessitates careful consideration of physiologically realistic uptake rates [21] [33]. For E. coli research, proper specification of these parameters enables predictions of growth rates, substrate utilization, gene essentiality, and metabolic engineering strategies under various conditions.

Theoretical Framework: From Composition to Constraints

Mathematical Foundation of Uptake Constraints

The mathematical representation of environmental conditions in FBA originates from the steady-state mass balance constraint, represented as Sv = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix containing stoichiometric coefficients of metabolites in each reaction, and v is the flux vector of all reaction rates in the network [4] [21]. In this formulation, each row corresponds to a metabolite and each column to a reaction, with negative coefficients indicating consumed metabolites and positive coefficients indicating produced metabolites [21].

Environmental constraints are implemented as inequality constraints on the flux vector v through lower and upper bounds (lb ≤ v ≤ ub). For uptake reactions, these bounds typically take specific forms:

- Lower bounds (lb) on exchange reactions are set to negative values to represent metabolite uptake, as negative flux indicates material entering the system

- Upper bounds (ub) on exchange reactions are typically set to zero or positive values, with zero indicating no secretion and positive values allowing metabolite export

- The magnitude of the negative lower bound defines the maximum uptake rate for a metabolite [21] [33]

For example, if glucose is available in the medium at a concentration that would permit a maximum uptake rate of 10 mmol/gDW/hr, the corresponding exchange reaction EXglcDe would typically have bounds set as -10 (lower bound) and 0 or a positive value (upper bound) [33].

Conceptual Relationship Between Medium Components and Model Constraints

Table 1: Relationship between experimental components and FBA implementation

| Experimental Component | FBA Implementation | Typical Bound Values | E. coli Example Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Source | Exchange reaction lower bound | Negative value (e.g., -10) | EXglcDe (D-glucose) |

| Electron Acceptor | Exchange reaction lower bound | Negative value for aerobic, 0 for anaerobic | EXo2e (oxygen) |

| Nitrogen Source | Exchange reaction lower bound | Negative value | EXnh4e (ammonium) |

| Phosphorus Source | Exchange reaction lower bound | Negative value | EXpie (phosphate) |

| Absent Metabolite | Exchange reaction bounds set to 0 | 0 (no uptake or secretion) | EXsucce (succinate) when absent |

| Secretion Products | Exchange reaction upper bound | Positive value (if allowed) | EXace (acetate) |

The conceptual framework for translating experimental conditions to FBA constraints involves several key considerations. The steady-state assumption requires that internal metabolites cannot accumulate, necessitating balanced production and consumption [4]. External metabolites (prefix "X" in some notations) are not subject to this balance and represent inputs and outputs to the system [4]. The objective function, typically biomass production for growth simulations, provides the optimization goal that drives flux distribution within the constrained system [21].

Figure 1: Workflow for translating experimental medium conditions to FBA constraints

Computational Implementation

Practical Implementation in COBRA Tools

The COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) toolbox provides standardized methods for implementing medium composition and uptake bounds in metabolic models. In COBRApy, the current growth medium of a model is managed through the medium attribute, which returns a dictionary of active exchange reactions and their upper import bounds [33].

The following protocol describes the essential steps for setting environmental conditions in an E. coli model:

- Load the model using

load_model()function - Examine current medium using

model.mediumto view active exchange reactions - Modify medium composition by creating a modified medium dictionary and assigning it to

model.medium - Apply changes to simulate specific environmental conditions

- Perform FBA using

model.slim_optimize()to obtain growth predictions [33]

A critical technical consideration is that model.medium cannot be assigned to directly, as it returns a copy of the current exchange fluxes. Instead, users must create a modified dictionary and assign it back to model.medium [33]:

Defining Anaerobic Conditions

To simulate anaerobic growth of E. coli, the oxygen exchange reaction must be constrained to prevent uptake:

This simulation typically shows reduced growth yield for E. coli under anaerobic conditions (approximately 0.21 hâ»Â¹) compared to aerobic growth (approximately 0.87 hâ»Â¹) [33], consistent with experimental observations [21].

To investigate growth on different carbon sources, disable the default carbon source and enable an alternative:

This approach allows researchers to predict growth capabilities on different substrates and identify potential nutrient limitations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and resources for setting environmental conditions in E. coli FBA

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRApy | Python package for constraint-based modeling | Setting medium composition and uptake bounds | https://cobrapy.readthedocs.io/ |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB suite for constraint-based modeling | FBA simulation with different environmental conditions | https://opencobra.github.io/cobratoolbox/ |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase of genome-scale metabolic models | Accessing curated E. coli metabolic models | http://bigg.ucsd.edu/ |

| Escher-FBA | Web application for interactive FBA | Visualizing effects of medium changes on flux distributions | https://sbrg.github.io/escher-fba/ |

| Fluxer | Web application for flux analysis | Visualizing genome-scale metabolic networks under different conditions | https://fluxer.umbc.edu/ |

| AGORA | Resource of genome-scale metabolic models for gut bacteria | Studying E. coli in community context | https://vmh.life/ |

Advanced Applications and Protocols

Minimal Medium Computation

An important application in metabolic modeling is identifying the minimal medium required to support a specific growth rate. COBRApy provides the minimal_medium() function for this purpose, which identifies the medium with the lowest total import flux [33]:

The function can also identify minimal media with the smallest number of active imports using the minimize_components=True argument, though this requires mixed-integer programming and is computationally more intensive [33].

Table 3: Example minimal medium compositions for E. coli core metabolism

| Carbon Source | Growth Rate (hâ»Â¹) | Required Nutrients | Uptake Flux (mmol/gDW/hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-Glucose | 0.87 | NHâ‚„, Oâ‚‚, POâ‚„ | EXglcDe: 10.0, EXnh4e: 4.77, EXo2e: 21.80, EXpie: 3.21 |

| Succinate | 0.40 | NHâ‚„, Oâ‚‚, POâ‚„ | EXsucce: 10.0, EXnh4e: ~2.5, EXo2e: ~15.0, EXpie: ~1.5 |

| Glucose (Anaerobic) | 0.21 | NHâ‚„, POâ‚„ | EXglcDe: 10.0, EXnh4e: ~2.0, EXpie: ~1.0 |

Protocol: Systematic Analysis of Gene Essentiality Across Environmental Conditions

This protocol enables researchers to identify condition-dependent essential genes in E. coli:

- Define baseline medium composition reflecting the environment of interest

- Identify all metabolic genes in the model using

model.genes - For each gene in the model:

- Create a copy of the model using

model.copy() - Knock out the gene using

model.genes.get_by_id(gene_id).knock_out() - Calculate growth rate using

model.slim_optimize() - Compare to wild-type growth rate

- Create a copy of the model using

- Classify genes as essential (growth rate < threshold) or non-essential

- Repeat under different environmental conditions to identify conditionally essential genes

This approach can reveal how environmental factors influence gene essentiality, with applications in drug target identification [4] [21].

Protocol: Dynamic Environment Simulation Using COMETS

For modeling microbial communities or changing environments, the COMETS (Computation of Microbial Ecosystems in Time and Space) tool extends FBA to incorporate spatial and temporal dimensions [34]: