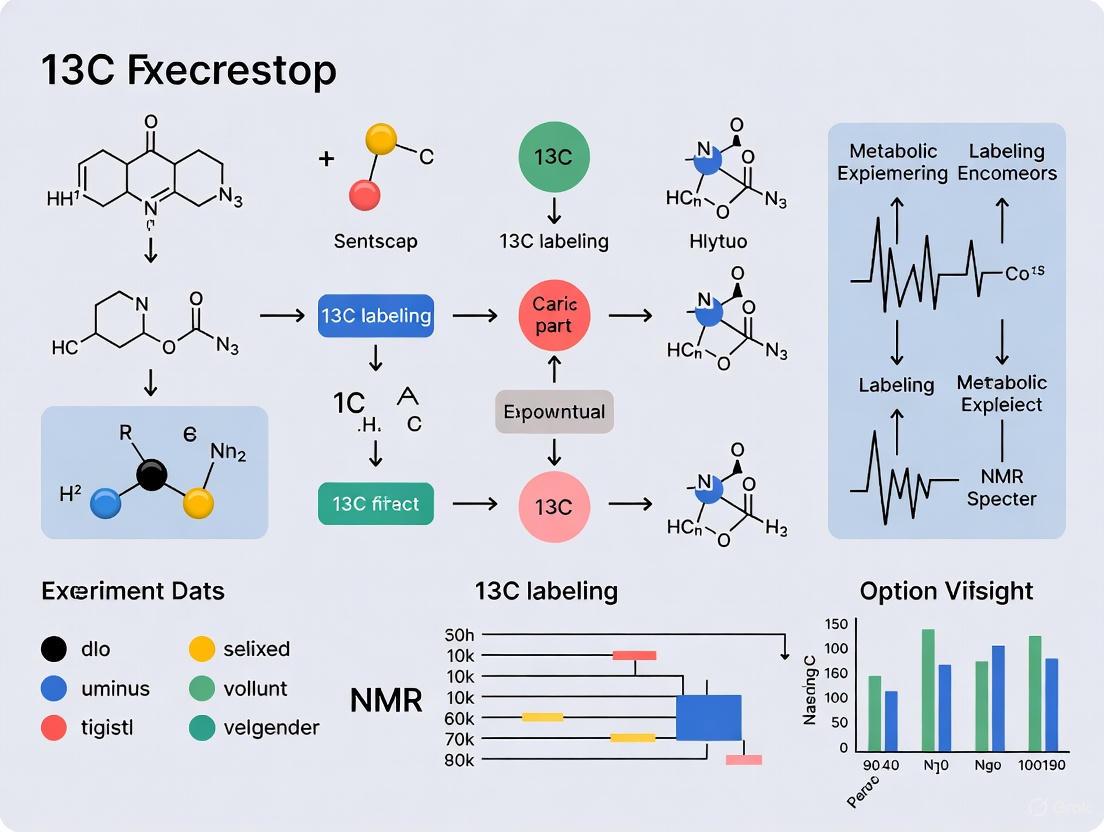

A Comprehensive Protocol for 13C Labeling Experiments and NMR Spectroscopy in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing and executing successful 13C labeling experiments with NMR spectroscopy.

A Comprehensive Protocol for 13C Labeling Experiments and NMR Spectroscopy in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing and executing successful 13C labeling experiments with NMR spectroscopy. It covers foundational principles of isotopic labeling, from tailored labeling strategies to minimize dipolar couplings in solid-state NMR to the selection of specific 13C-labeled precursors like [1-13C]-glucose. The protocol details methodological aspects including hardware setup, pulse sequence selection, and data acquisition parameters optimized for sensitivity. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization techniques for enhancing signal-to-noise ratio and managing RF power deposition. Finally, the guide outlines systematic approaches for spectral validation and comparative analysis, ensuring reliable metabolic flux measurements and accurate compound identification in complex biological systems.

Core Principles and Strategic Design of 13C Labeling

Solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (ssNMR) spectroscopy has emerged as a pivotal technique for determining the structure and dynamics of complex biological systems, including plant cell walls and membrane proteins. However, the low natural abundance of the 13C isotope (approximately 1.1%) presents a fundamental challenge, resulting in inherently weak signals and limited sensitivity for conventional NMR analysis [1] [2]. 13C isotopic labeling serves as a critical strategy to overcome this limitation, artificially enriching samples with 13C to significantly boost the signal-to-noise ratio. This enables the application of advanced multi-dimensional correlation experiments essential for detailed structural elucidation [1] [3]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on NMR protocol development, details the principles, methodologies, and practical protocols for 13C labeling and sensitivity enhancement, providing a structured guide for researchers in the field.

13C-Labeling Strategies

The core objective of 13C-labeling is to incorporate 13C isotopes into a target molecule or organism at a level substantially higher than its natural occurrence. Different strategies are employed based on the system under study and the specific research goals.

Uniform 13C-Labeling of Plant Cell Walls

For plant materials, a simplified and cost-effective protocol using a vacuum-desiccator has been developed to achieve high levels of uniform labeling. This method avoids the need for large, specialized growth chambers and large quantities of expensive 13CO2 [1].

Key Steps of the Protocol [1]:

- Sterilization and Germination: Surface-sterilized rice seeds (Oryza sativa - Kitaake cultivar) are placed on a half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media supplemented with 1% (w/v) 13C-labeled glucose. They are germinated for 4-5 days under continuous light.

- 13CO2 Supplementation: The germinated seedlings in their jars are transferred to a dry-seal vacuum-desiccator. A vacuum is applied to the desiccator, and 1L of 13CO2 (99.0 atom % 13C) is released into the chamber from a balloon.

- Growth and Harvest: The seedlings continue to grow inside the sealed desiccator for two weeks under continuous light before the 13C-labeled plant material is harvested.

This protocol achieves approximately 60% 13C-labeling of the cell walls, a level sufficient for all conventional 2D and 3D correlation ssNMR experiments [1].

Random Fractional 13C-Labeling for Membrane Proteins

For eukaryotic membrane proteins, a random fractional labeling strategy in P. pastoris expression systems can be used to enhance spectral resolution. This approach reduces the strong 13C-13C dipole-dipole couplings and spin diffusion that can broaden resonance lines in uniformly labeled samples [3].

Key Steps of the Protocol [3]:

- Expression System: The target membrane protein (e.g., eukaryotic rhodopsin from Leptosphaeria maculans) is expressed in P. pastoris, which can use methanol as a sole carbon source.

- Methanol Feed: The yeast is cultured in a medium containing a specific mixture of natural abundance methanol and 13C-methanol.

- Optimization: A 13C enrichment level of 25% (achieved with a 1:3 ratio of 13C-methanol to NA-methanol) has been determined to provide an optimal balance between spectral sensitivity and resolution, reducing average 13C linewidths by half compared to uniform labeling [3].

Table 1: Comparison of 13C-Labeling Strategies

| Strategy | Target System | Labeling Precursor | Typical Enrichment Level | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Labeling [1] | Plant Cell Walls | 13C-glucose & 13CO2 | ~60% | High sensitivity for multi-dimensional NMR |

| Random Fractional Labeling [3] | Membrane Proteins | 13C-methanol / NA-methanol mixture | ~25% | Improved spectral resolution |

Sensitivity Enhancement in 13C NMR

Beyond isotopic labeling, several technical approaches are employed to further enhance sensitivity in 13C NMR experiments.

- Signal Averaging: The signal-to-noise ratio is improved by repeatedly collecting and averaging multiple scans, which reduces the impact of random noise. This is particularly crucial for 13C NMR due to the low natural abundance of 13C [2].

- Proton Decoupling: This technique removes the splitting of 13C signals by bonded protons, simplifying the spectrum and increasing signal intensity by collapsing multiplets into single peaks [2].

- Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE): The NOE allows for the transfer of spin polarization from the more abundant 1H nuclei to the 13C nuclei, effectively boosting the 13C signal intensity [2].

- Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement: The addition of paramagnetic relaxation reagents, such as 10 mM Cu(II)Na2EDTA, can reduce 1H T1 relaxation times from several hundred milliseconds to 60-70 ms. This permits the use of shorter recycle delays between scans, leading to faster signal accumulation and sensitivity enhancements by a factor of 1.4 to 2.9 [4].

- Cryogenic Probes: The use of superconducting technology to cool the NMR detection coils significantly reduces thermal noise, thereby greatly increasing the signal-to-noise ratio [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: 2D Constant-Time 13C HSQC

The following protocol describes a 2D constant-time (CT) 13C-HSQC experiment, optimized for aliphatic regions in proteins. This experiment produces high-resolution 13C-1H correlation spectra and is vital for resonance assignment and interaction studies [5].

Required Isotope Labeling: U-15N,13C or U-13C. It is not suitable for uniformly deuterated samples. Application to natural abundance samples requires high concentration and sensitive probes [5].

Experimental Workflow

Step 1: Initial Setup and Sample Preparation

- Begin with a uniformly 13C/15N-labeled protein sample in an appropriate buffer.

- Insert the sample into the magnet. Ensure the sample is locked, and the 1H, 13C, and 15N channels are tuned and matched. Acquire a basic 1D 1H spectrum with water suppression to assess sample quality [5].

Step 2: Create Experiment and Load Parameters

- Create a new dataset, incrementing the experiment number (EXPNO).

- Select the starting parameter set

HSQC_CT_13C_ALI_xxx.par(wherexxxcorresponds to the spectrometer frequency, e.g., 900, 800) [5]. - Load the pulse program

hsqcctetgpsisp_ali.nan(or equivalent), which uses sensitivity-enhanced echo-antiecho gradient coherence selection [5].

Step 3: Pulse Calibration and Parameter Adjustment

- Calibrate the 1H 90° pulse width (

P1) and its power level (PLW1). Use thegetprosolcommand to load the PROSOL table values for 13C and 15N pulses, or use thebtprepcommand if parameters were optimized via the BioTop GUI [5]. - Key parameters to inspect and adjust:

- Spectral Width (SW): Set 1 SW (13C) and 2 SW (1H) appropriately.

- Offset (O1P, O2P): Set 1H (O1P) and aliphatic 13C (O2P) carrier frequencies.

- Constant-Time Delay (D23): Typically set to 0.0133 s (1/1JCC) or 0.0266 s (2/1JCC), where 1JCC is ~37.5 Hz. The choice affects peak signs and resolution [5].

- Acquisition Time (AQ): Set the direct acquisition time (2 AQ) between 50 ms (for large proteins) and 120 ms (for small proteins) [5].

Step 4: Data Acquisition and Processing

- Run the experiment. For optimal signal-to-noise and resolution, the number of points in the indirect dimension (1 TD) should be set to the maximum allowed value, as dictated by the constant-time scheme [5].

- Process the data with appropriate window functions (e.g., Gaussian line broadening) and Fourier transformation to generate the final 2D spectrum [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for 13C-Labeling and NMR Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Glucose | Carbon source for uniform labeling of plant or microbial systems | Cambridge Isotope Labs (CLM-1396-PK) [1] |

| 13CO2 Gas | Carbon source for photosynthetic labeling of plants | 99.0 atom % 13C (e.g., Sigma Aldrich 364592) [1] |

| 13C-Methanol | Carbon source for random fractional labeling in P. pastoris | Used in mixture with natural abundance methanol [3] |

| Cu(II)Na2EDTA | Paramagnetic relaxation reagent to reduce 1H T1 times | 10 mM concentration in sample [4] |

| Cryogenic Probe | NMR hardware that cools detection coils to reduce thermal noise | Significantly enhances signal-to-noise ratio [2] |

| Vacuum-Desiccator | Sealed chamber system for efficient 13CO2 labeling of plants | ~2.2 L volume, enables cost-effective labeling [1] |

Concluding Remarks

The strategic implementation of 13C isotopic labeling—whether uniform for high sensitivity or fractional for improved resolution—is a cornerstone of modern biomolecular NMR. When combined with robust experimental protocols and sensitivity enhancement techniques such as paramagnetic doping and cryoprobes, researchers can effectively overcome the intrinsic sensitivity challenges of 13C NMR. These integrated methodologies provide a powerful framework for advancing structural biology and drug discovery efforts, enabling the detailed analysis of complex systems from plant biomass to therapeutic membrane protein targets.

Advantages of 13C-Detection over 15N-Detection in Solid-State NMR

In solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (SSNMR) spectroscopy, the choice of the observed nucleus is a fundamental decision that profoundly influences the sensitivity, resolution, and overall feasibility of an experiment. For researchers investigating the structure and dynamics of biological macromolecules and complex organic materials, 13C-detection and 15N-detection represent two principal pathways. This application note delineates the technical and practical advantages of 13C-detection over 15N-detection, providing a foundational rationale for its prioritized adoption in protocol development for 13C-labeling experiments. The superior gyromagnetic ratio (γ) of 13C and its higher natural isotopic abundance are the core physical principles that confer significant sensitivity benefits, making 13C-detection the more efficient and versatile choice for a wide range of applications in pharmaceutical and bioenergy research [6] [7].

Fundamental Physical and Practical Advantages

The performance differential between 13C- and 15N-detection in SSNMR stems from intrinsic nuclear properties and their experimental consequences. The following table summarizes the key comparative parameters.

Table 1: Fundamental Nuclear Properties of 13C and 15N and Their Experimental Implications

| Parameter | 13C | 15N | Experimental Impact of 13C Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gyromagnetic Ratio (γ) | ≈ 10.7 × 10^7 rad T^-1 s^-1 | ≈ -4.3 × 10^7 rad T^-1 s^-1 | 13C has a γ roughly 2.5 times larger than 15N, directly contributing to a higher intrinsic sensitivity [6]. |

| Natural Isotopic Abundance | 1.1% | 0.37% | The nearly 3-fold higher natural abundance of 13C is beneficial for experiments on natural abundance samples and reduces the required level of isotopic enrichment [6] [7]. |

| Receptivity (Relative to 13C) | 1.0 | 0.021 | Combined effect of γ and natural abundance makes 15N-detection inherently less sensitive; 13C is significantly more receptive [6]. |

| Typical Linewidths in Proteins | 0.1 - 0.3 ppm (e.g., 0.11 - 0.33 ppm at 1.1 GHz) [8] | Broader than 13C | Tighter linewidths for 13C directly enhance spectral resolution, crucial for studying large molecular systems. |

| Key Functional Groups Probed | Carbonyls, aliphatics, aromatics/CRAM [9] [7] | Amides, heterocyclic nitrogen [9] | 13C provides a more comprehensive view of molecular backbone and side chains, which is valuable for characterizing complex materials like lignocellulosic biomass [7]. |

The low gyromagnetic ratio of 15N not only reduces its intrinsic sensitivity but also complicates the use of cross polarization (CP), a cornerstone technique for signal enhancement in SSNMR. In deuterated solvent conditions often used for dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP), backbone amide protons are vulnerable to exchange with deuterons, which severely reduces the efficiency of the initial 1H-15N CP transfer step essential for 15N-detection. This necessitates unusually long CP contact times and careful optimization, leading to experimental instabilities, particularly at ultra-low temperatures (e.g., 25 K) [10]. In contrast, 1H-13C CP is far more robust and efficient under the same conditions, making 13C-detection a more reliable and simpler-to-implement approach [10] [7].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Basic Workflow for 13C-Detected SSNMR

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for a 13C-detected SSNMR experiment, highlighting its comparative simplicity versus 15N-detected approaches.

Detailed Protocol: 13C-Detected 2D NCa Correlation Experiment

This protocol is adapted from studies that utilize the Transferred Echo DOuble Resonance (TEDOR) sequence as a robust alternative to 15N-detected experiments, particularly in challenging DNP conditions or with deuterated samples [10].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Isotopic Labeling: Incorporate 13C and 15N labels uniformly or at specific sites (e.g., 13Cα, 15N-backbone).

- Sample Concentration: Ideal concentration is ≥ 1 mM for proteins. For bioenergy applications like lignin, analysis is performed at natural abundance [7].

- Rotor Packing: Pack the solid, crystalline, or amorphous sample into a MAS rotor (e.g., 1.6 mm or 3.2 mm) under controlled humidity if necessary to maintain hydration and sample integrity.

2. Instrument Setup:

- Magnetic Field: Set to desired field strength (e.g., 9.4 T / 400 MHz 1H Larmor frequency or higher).

- MAS Rate: Set to a stable, fast spinning speed (e.g., 12-40 kHz, depending on rotor size and probe capabilities) to minimize spinning sidebands.

- Temperature Control: Regulate the temperature, which is critical for low-temperature DNP experiments (e.g., 25 K with helium gas cooling) [10].

- External Lock (For gigahertz-class systems): If available, activate the external 2H lock system using a D2O-containing capillary to compensate for magnetic field drift, ensuring high spectral resolution [8].

3. Pulse Sequence Execution (ZF-TEDOR):

- 1H-13C CP: Begin with a 1H-13C cross polarization step to transfer magnetization from 1H to 13C. Use a contact time of 1-2 ms.

- 13C-15N TEDOR Transfer: Implement a z-filtered TEDOR period to generate 13C-15N antiphase coherence. This involves a series of rotor-synchronized π pulses on both 13C and 15N channels to recouple the dipolar interaction.

- 15N Evolution (t1): Increment the 15N chemical shift evolution period (t1) to obtain the indirect 15N dimension.

- Back-TEDOR Transfer: A second REDOR period converts the antiphase coherence back to observable 13C single-quantum coherence.

- 13C Detection: Acquire the 13C signal under high-power 1H decoupling (e.g., SPINAL-64 or TPPM) to suppress 1H-13C dipolar couplings.

4. Data Processing:

- Processing: Process the data in both dimensions with appropriate apodization functions (e.g., Lorentzian-to-Gaussian transformation). Apply zero-filling and Fourier transformation.

- Referencing: Reference the 13C and 15N chemical shifts to external standards (e.g., adamantane for 13C) [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of SSNMR experiments relies on specialized materials and reagents. The following table outlines essential items for 13C-based SSNMR research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 13C-Detected SSNMR

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Precursors | Isotopic enrichment of target molecules (e.g., proteins, RNA, metabolic products). | Includes 13C-glucose, 13C-acetate, or site-specific labeled amino acids. Critical for sensitivity. Cost is a major factor [7]. |

| Cryoprotectants / DNP Matrix | Forms a glassy matrix for DNP samples to ensure proper vitrification and polarization transfer. | Common matrix: "DNP Juice" (e.g., d8-glycerol/D2O/H2O). Biradicals (e.g., sulfoacetyl-DOTOPA) are used as polarizing agents [10]. |

| Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) Rotors | Holds the sample and spins at the magic angle (54.74°) to achieve high resolution. | Available in various diameters (1.6 mm, 3.2 mm, 4.0 mm). Smaller rotors enable faster MAS rates, improving resolution [8] [11]. |

| External Lock Solvent | Provides a stable deuterium signal for magnetic field frequency locking in gigahertz-class spectrometers. | High-purity D2O sealed in a capillary. Mitigates field drift, which is a significant challenge in ultra-high field HTS magnets [8]. |

| Chemical Shift Reference Standards | For precise calibration of 13C (and 15N) chemical shifts. | Adamantane is a common solid standard for 13C. Ensures data reproducibility and interoperability between labs [8]. |

Application-Specific Workflows: From Biomolecules to Bioenergy

The advantages of 13C-detection are realized across diverse fields. In structural biology, 13C-detected experiments are employed for backbone and side-chain resonance assignment in proteins and RNAs, which is a critical step in structure determination [11]. For large molecular assemblies exceeding 100 kDa, 13C-detection provides the necessary resolution and sensitivity, as demonstrated by the assignment of over 500 amide backbone pairs in a 144 kDa protein assembly [8].

In organic geochemistry and bioenergy research, 13C CPMAS NMR is indispensable for the characterization of complex heterogeneous materials like marine dissolved organic matter (DOM) and lignocellulosic biomass [9] [7]. The technique provides quantitative insights into the functional group composition of these materials (e.g., quantifying carboxyl-rich alicyclic molecules vs. aromatic carbon) without the need for dissolution or extensive chemical processing [9] [12] [7]. The workflow for such analyses is illustrated below.

13C-detection stands as the superior methodology in solid-state NMR for protocol development involving 13C-labeling, offering compelling advantages in sensitivity, resolution, and experimental robustness over 15N-detection. Its higher gyromagnetic ratio and natural abundance translate directly into time-efficient data acquisition and the ability to study more complex and larger molecular systems, from pharmaceutical formulations to whole biomass. While 15N-detection retains its niche for probing specific nitrogenous functional groups, the broader analytical utility and performance of 13C-detection make it the cornerstone technique for advancing research in structural biology, drug development, and renewable bioenergy.

Solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (ssNMR) spectroscopy has emerged as a pivotal technique for determining the structures and dynamics of complex biological systems, including membrane proteins and plant cell walls. A significant challenge in ssNMR, particularly for large proteins, is the presence of strong 13C–13C homonuclear dipole–dipole couplings in uniformly labeled samples, which lead to broad spectral lines and reduced resolution [13]. To overcome this, tailored isotopic labeling strategies are employed to dilute the 13C spin network, thereby simplifying spectra and enhancing sensitivity [14]. Two primary approaches for achieving this are random fractional 13C labeling and metabolic site-specific labeling. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these strategies, including quantitative data, step-by-step protocols, and visual workflows, to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal labeling method for their ssNMR studies.

Background and Principles

The Need for Sparse Labeling in ssNMR

In solution-state NMR and magic-angle spinning (MAS) ssNMR, rapid molecular tumbling or physical spinning averages out homonuclear 13C–13C couplings. However, in stationary aligned samples used in ssNMR, these couplings remain strong and are not averaged, leading to broadened resonance lines and loss of information [13]. The core principle of sparse labeling is to reduce the probability that two 13C nuclei are directly bonded or in close proximity, thus minimizing these detrimental couplings. This enables the use of sensitive 13C-detected experiments without the need for complex homonuclear decoupling sequences [14].

- Random Fractional 13C Labeling: This method involves incorporating a mixture of 13C-labeled and natural abundance (12C) carbon sources during protein expression. The result is a statistical, random distribution of 13C atoms throughout the protein at a defined, reduced enrichment level [3] [14].

- Site-Specific Metabolic Labeling: This strategy uses metabolic precursors labeled at specific carbon positions (e.g., [2-13C]-glycerol or [1,3-13C]-glycerol). The bacterial or yeast metabolism then directs these labels into specific atomic positions within the amino acids of the expressed protein, creating a predictable, non-random pattern of isotopic enrichment [13] [14].

Random Fractional 13C Labeling

Principle and Workflow

Random fractional labeling takes advantage of the fact that expression hosts like P. pastoris can use methanol as a sole carbon source. By using a defined mixture of 13C-methanol and natural abundance methanol in the growth medium, proteins with a random, sparse distribution of 13C atoms are produced [3]. The probability of two 13C atoms being adjacent is low, thus reducing 13C–13C dipolar couplings.

The following workflow outlines the protocol for random fractional labeling using P. pastoris for a eukaryotic membrane protein:

Detailed Protocol: Random Fractional Labeling forP. pastoris

Key Reagent Solutions:

- 13C-Methanol: The source of 13C label.

- Natural Abundance Methanol: The source of 12C for dilution.

- Minimal Methanol Medium: For protein expression.

Procedure:

- Media Preparation: Prepare the expression medium containing a mixture of 13C-methanol and natural abundance methanol. A 25% 13C-methanol to 75% NA-methanol ratio has been identified as optimal for balancing spectral sensitivity and resolution for a eukaryotic rhodopsin [3].

- Culture and Induction: Inoculate the P. pastoris culture expressing the target protein (e.g., Leptosphaeria maculans rhodopsin). Induce protein expression by adding the prepared methanol mixture.

- Protein Purification: Harvest the cells and purify the target membrane protein using standard purification protocols (e.g., detergent extraction and chromatography).

- Labeling Verification: Verify the extent of 13C incorporation and protein integrity using analytical methods such as mass spectrometry or solution NMR [3].

Expected Outcomes and Data

This protocol, using a 25% enrichment level, resulted in an average 13C linewidth that was half of that observed with uniform 13C labeling for the model protein LR. This linewidth reduction directly led to a 50% increase in the number of well-resolved cross-peaks in 2D 15N-13Cα correlation spectra [3].

Table 1: Impact of Random Fractional 13C Enrichment on Spectral Quality

| 13C-Methanol Ratio | Average 13C Linewidth | Resolved 15N-13Cα Cross-peaks | Cost Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% (Uniform) | Baseline (Wide) | Baseline | High |

| 45% | Reduced | Increased | Moderate |

| 25% | ~50% Reduction | ~50% Increase | Low (Optimal) |

| 15% | Further Reduced | Limited by Sensitivity | Very Low |

Site-Specific Metabolic Labeling

Principle and Workflow

Site-specific labeling utilizes the metabolic pathways of the expression host (typically E. coli) to incorporate 13C from specific precursors into defined atomic positions in the protein. For example, [2-13C]-glycerol leads to labeling primarily at Cα positions for certain amino acids, while [1,3-13C]-glycerol labels Cα and carbonyl (C') positions in a complementary pattern [13]. This creates isolated 13C spins at specific sites of interest.

The metabolic pathway and experimental setup for this strategy are as follows:

Detailed Protocol: Site-Specific Labeling inE. coli

Key Reagent Solutions:

- [2-13C]-Glycerol or [1,3-13C]-Glycerol: The metabolic precursors for site-specific labeling. [2-13C]-glycerol is particularly effective for labeling Cα sites [14].

- 15N-Ammonium Sulfate: For uniform 15N labeling.

- Minimal Medium (e.g., M9): Lacks other carbon sources to ensure the labeled glycerol is metabolized.

Procedure:

- Media Preparation: Prepare minimal medium (e.g., M9) supplemented with the chosen 13C-labeled glycerol (e.g., 2-3 g/L) as the sole carbon source and 15N-ammonium sulfate as the sole nitrogen source [13].

- Culture and Expression: Inoculate with an E. coli strain expressing the target protein (e.g., Pf1 coat protein). Grow the culture and induce protein expression under standard conditions.

- Protein Purification: Harvest cells and purify the target protein.

- Pattern Verification: Analyze the labeling pattern using 2D 1H-13C Heteronuclear Single Quantum Correlation (HSQC) solution-state NMR on a protein sample in micelles. This confirms the expected variations in signal intensities at different carbon sites, such as strong Cα labeling for glycine and serine from [2-13C]-glycerol [13].

Expected Outcomes and Data

Proteins labeled with [2-13C]-glycerol show a substantial increase in sensitivity in 13C-detected ssNMR spectra compared to 15N-detected experiments. The labeling is non-uniform; for Pf1 coat protein, incorporation at Cα positions varied from nearly 100% for glycine and serine to less than 10% for leucine [13]. This tailored approach allows for successful PISEMA and other triple-resonance experiments that typically fail with uniformly 100% 13C-labeled samples [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Site-Specific Labeling Precursors

| Labeled Precursor | Primary Labeling Sites | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [2-13C]-Glycerol | Cα atoms (pattern is amino acid-dependent) | Effective for protein backbone studies; isolates 13Cα spins [14] | Labeling efficiency varies by amino acid type [13] |

| [1,3-13C]-Glycerol | Cα and C' (carbonyl) atoms | Complementary pattern to [2-13C]-glycerol; useful for backbone assignments | Can lead to adjacent 13C labels (e.g., Cα-C') |

| [2-13C]-Glucose | Cα atoms | Highly effective for backbone studies, often superior to glycerol [14] | Can be more expensive than glycerol |

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guide

Side-by-Side Strategy Comparison

Table 3: Strategic Comparison of 13C-Labeling Approaches

| Parameter | Random Fractional Labeling | Site-Specific Metabolic Labeling |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Statistical dilution of 13C spins | Directed labeling via metabolic pathways |

| 13C Distribution | Random throughout protein | Specific to atomic positions (e.g., Cα) |

| Optimal Enrichment | 25% - 35% [3] [14] | N/A (Site-dependent) |

| Key Benefit | General linewidth reduction; cost-effective | Targets specific resonances of interest |

| Primary Application | General improvement of spectral resolution for any site | Focusing on specific regions like the protein backbone |

| Expression Host | P. pastoris (eukaryotic) [3] | E. coli (prokaryotic) [13] |

| Cost | Low (uses economical 13C-methanol) [3] | Moderate (precursors like glycerol are cost-effective) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for 13C-Labeling Strategies

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Methanol | Carbon source for random fractional labeling in P. pastoris | Dilution with NA-methanol to achieve 25% enrichment [3] |

| [2-13C]-Glycerol | Metabolic precursor for site-specific labeling of Cα atoms | Backbone-focused ssNMR studies in E. coli [13] [14] |

| 15N-Ammonium Sulfate | Uniform nitrogen source for dual 13C/15N labeling | Essential for triple-resonance (1H/13C/15N) experiments [13] |

| Minimal Medium (M9) | Defined medium lacking other carbon sources | Forces bacteria to use the supplied 13C-precursor [13] |

| Detergents (e.g., DPC) | Solubilizes and stabilizes membrane proteins | Purification and NMR analysis of membrane proteins [15] |

Implementation Workflow: From Strategy to Spectrum

The following integrated workflow summarizes the decision-making process and experimental steps from project inception to data acquisition:

Concluding Remarks

Both random fractional and site-specific 13C labeling strategies are powerful tools for advancing ssNMR studies of complex biomolecules. The choice between them depends on the research objective, the target protein, and the available expression system. Random fractional labeling (25-35% enrichment) is a robust, cost-effective general approach for improving spectral resolution, making it ideal for initial structural studies of eukaryotic membrane proteins [3]. In contrast, site-specific labeling with precursors like [2-13C]-glycerol provides a targeted method to isolate and study specific regions of the protein, such as the backbone, with high sensitivity [13] [14]. By implementing these detailed protocols, researchers can effectively overcome the challenges of 13C-13C dipolar couplings and unlock high-resolution structural and dynamic insights into their systems of interest.

The selection of an appropriate 13C-labeling precursor is a critical foundational step in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy that directly determines the success and efficiency of structural and dynamic studies of biomolecules. Strategic selection of labeling precursors moves beyond simple uniform enrichment, enabling researchers to control the placement of 13C isotopes to reduce signal overlap, simplify complex spectra, and extract specific metabolic flux information. For researchers investigating membrane protein structures, RNA dynamics, plant cell wall architectures, or cellular metabolic pathways, the choice between precursors like [2-13C]-glucose, various forms of glycerol, and uniformly labeled carbon sources involves careful consideration of biosynthetic pathways, cost, and the specific NMR application. This Application Note provides a structured comparison of these key precursors and details specialized protocols to guide experimental design, ensuring that researchers can effectively balance spectral resolution with experimental sensitivity and cost.

Precursor Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below provides a quantitative summary of key 13C-labeling precursors, their primary applications, and their specific advantages for different experimental needs.

Table 1: Comparison of Common 13C-Labeling Precursors for NMR Spectroscopy

| Precursor | Target System/Application | Key Outcomes & Labeling Efficiency | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Methanol (Random Fractional) | Eukaryotic membrane proteins in P. pastoris [3] | ∼25% enrichment optimal for SSNMR; 50% reduction in 13C linewidth versus uniform labeling; doubled number of resolved cross-peaks [3] | Cost-effective sparse labeling; superior spectral resolution |

| [U-13C]-Glucose | Metabolic flux analysis (e.g., brain Glu/Gln cycling) [16]Cell wall analysis in plants [1]Protein backbone assignment [17] | Enables quantification of neurotransmitter cycle fluxes in human brain [16]>60% 13C-enrichment in plant cell walls [1] | Versatile; widely integrated into core metabolism |

| [1,3-13C]-Glycerol | Nucleotide/RNA synthesis in E. coli mutant strains (e.g., DL323) [18]Protein sidechain labeling [17] | Selective labeling of purine C2/C8 (~90%) and ribose C5' (~90%); isolated spin systems [18] | Specific, isolated labeling to reduce scalar couplings |

| [2-13C]-Glycerol | Nucleotide/RNA synthesis in E. coli mutant strains [18] | Selective labeling of pyrimidine C6 (~96%); ribose labeled except C3'/C5' [18] | Cost-effective route for specific pyrimidine labeling |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for 13C-Labeling Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Methanol Mixture | Random fractional labeling for SSNMR | Creating sparse 13C labels in P. pastoris-expressed membrane proteins [3] |

| [U-13C]-Glucose | Uniform labeling for metabolic flux & structural NMR | Infusion for neuroenergetics studies; carbon source for plant/ bacterial culture [16] [1] |

| 13C-Glycerol Isomers | Selective labeling for RNA & protein NMR | [1,3-13C] or [2-13C] glycerol for nucleotide production in E. coli [18] |

| Methyl Precursor Kit | Specific sidechain labeling for proteins | ILVTA-labeled samples for solution NMR of large proteins [17] |

| 13CO2 | In planta uniform labeling | Supplied in a vacuum-desiccator for labeling entire plant seedlings [1] |

| 13C-Formate | Enhancement of specific sites in nucleotides | Boosts enrichment at purine C8 position when added to growth media [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Random Fractional 13C-Labeling of Membrane Proteins in P. pastoris

This protocol describes a cost-effective method for sparse 13C-labeling to enhance solid-state NMR spectral resolution of eukaryotic membrane proteins, utilizing P. pastoris's ability to metabolize methanol as a sole carbon source [3].

Materials:

- Expression plasmid containing target membrane protein (e.g., Leptosphaeria maculans rhodopsin)

- P. pastoris expression strain

- Natural abundance methanol

- 13C-methanol (99% isotopic purity)

- Minimal media for P. pastoris fermentation

Procedure:

- Transformation & Selection: Transform the expression plasmid into a suitable P. pastoris strain and select recombinant clones following standard protocols.

- Inoculum Culture: Grow a primary inoculum in a rich medium like YPD or minimal glycerol medium to high cell density.

- Induction with Methanol Mixture: Induce protein expression by adding a filter-sterilized mixture of natural abundance methanol and 13C-methanol. A 1:3 ratio of 13C-methanol:NA-methanol (25% enrichment) is recommended as an optimal starting point, balancing cost, sensitivity, and linewidth reduction [3].

- Fed-Batch Fermentation: Maintain the induction phase for 48-96 hours, feeding the methanol mixture to sustain protein production.

- Harvest and Purification: Harvest cells by centrifugation. Subsequently, purify the target membrane protein using appropriate detergent solubilization and chromatography techniques.

- SSNMR Analysis: Analyze the purified, reconstituted protein using SSNMR. Compare 1D-13C and 2D 15N-13C spectra with those from uniformly labeled samples to confirm linewidth reduction and peak resolution enhancement [3].

Protocol 2: Selective 13C-Labeling of Nucleotides in E. coli for RNA NMR

This protocol utilizes mutant E. coli strains and specific glycerol isotopologues to produce nucleotides with tailored 13C-labeling patterns, simplifying NMR spectra of large RNAs [18].

Materials:

- E. coli DL323 strain (lacking succinate and malate dehydrogenases)

- [1,3-13C]-glycerol or [2-13C]-glycerol

- 13C-formate (optional, for enhancing specific sites)

- M9 minimal salts

- 15NH4Cl as sole nitrogen source

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Transform the DL323 E. coli strain with plasmids for nucleotide synthesis, if necessary. Start a small overnight culture in LB medium.

- Inoculation and Growth: Dilute the overnight culture into M9 minimal media containing 15NH4Cl and the chosen 13C-glycerol isotopologue as the sole carbon source.

- Optional Formate Enhancement: To achieve high enrichment (~88%) at the purine C8 position when using [2-13C]-glycerol, supplement the media with 13C-formate [18].

- Nucleotide Extraction: Harvest cells at stationary phase. Extract and purify nucleotides using established enzymatic or chromatographic methods.

- RNA Transcription & Analysis: Use the purified nucleotides for in vitro transcription of the target RNA. Acquire NMR spectra and leverage the simplified coupling patterns for assignment and structural analysis.

Protocol 3: Efficient 13C-Labeling of Plant Cell Walls for ssNMR

This protocol describes a simple and cost-effective method to achieve high levels of 13C-enrichment in plant cell walls using a vacuum-desiccator system, facilitating structural studies via ssNMR [1].

Materials:

- Rice seeds (Oryza sativa), Kitaake cultivar

- Half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media

- [U-13C]-Glucose

- 13CO2 gas (99.0 atom % 13C)

- Vacuum-desiccator (~2.2 L volume) with sleeve valves

- Laminar flow hood

Procedure:

- Seed Sterilization: Surface-sterilize de-husked rice seeds with 70% ethanol and a 40% Clorox solution, followed by multiple washes with sterile distilled water [1].

- Germination on 13C-Glucose: Place the sterilized seeds on jars containing half-strength MS media supplemented with 1% (w/v) [U-13C]-glucose. Incubate at 22°C under continuous light for 4-5 days until germination [1].

- Setup of 13CO2 Supplementation: Transfer the jars to a vacuum-desiccator. Connect a balloon filled with 1L of 13CO2 gas to a sleeve valve on the desiccator lid [1].

- Plant Growth under 13CO2 Atmosphere: Briefly apply a vacuum to the desiccator for approximately 2 minutes to remove an equivalent volume of air. Then, release the 13CO2 from the balloon into the desiccator. Seal the system and grow the seedlings for two weeks under continuous light [1].

- Harvest and NMR Analysis: Harvest the plant tissue. For ssNMR, pack the native (never-dried) plant tissue directly into a magic-angle spinning (MAS) rotor. Acquire 1D 13C cross-polarization (CP) and 2D/3D correlation spectra to resolve polymer interactions within the native cell wall structure [1].

Metabolic Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core metabolic logic of precursor selection and the generalized workflow for a 13C-labeling experiment.

Diagram 1: Metabolic Routing of Labeling Precursors. This diagram outlines how different 13C-labeled precursors feed into central metabolic pathways to become the building blocks for various biomolecules studied by NMR.

Diagram 2: 13C-Labeling Experiment Workflow. This flowchart shows the generalized sequence of steps for a successful 13C-labeling experiment, from initial goal-setting to final data analysis.

The strategic selection of a 13C-labeling precursor is a critical determinant of success in NMR spectroscopy. As detailed in these Application Notes, the choice is not merely technical but conceptual, requiring alignment with the core scientific question. No single precursor is universally superior; the optimal strategy emerges from a clear understanding of the trade-offs between resolution, sensitivity, cost, and biological system constraints. The protocols and comparisons provided herein offer a framework for researchers to make informed decisions, whether the goal is achieving spectral simplification in RNA studies through selective glycerol labeling, enhancing membrane protein spectral resolution via cost-effective fractional methanol labeling in P. pastoris, or performing comprehensive structural analysis of plant cell walls using efficient 13CO2 and glucose incorporation. By applying these principles, scientists can design robust and effective labeling strategies that maximize the return from their demanding NMR investigations.

The Concept of Isotopic Isolation to Minimize Homonuclear Dipolar Couplings

In nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, the homonuclear dipolar coupling interaction between abundant spins, such as 13C-13C, presents a significant challenge for obtaining high-resolution spectra. In solid-state NMR, this network of couplings leads to broad spectral lines and severe overlap, complicating the extraction of detailed molecular information [14] [19]. The concept of isotopic isolation has been developed as a powerful strategy to mitigate these effects. This approach involves tailoring the isotopic labeling pattern to ensure that 13C-labeled sites are spatially isolated from other 13C nuclei, thereby minimizing homonuclear dipolar couplings and eliminating the need for complex homonuclear decoupling sequences [14]. This protocol outlines the theoretical principles and practical methodologies for implementing isotopic isolation in 13C-labeling experiments, providing a framework for enhanced structural studies of biological macromolecules.

Table: Key Challenges Addressed by Isotopic Isolation

| Challenge | Impact on NMR Spectroscopy | Solution via Isotopic Isolation |

|---|---|---|

| Strong 13C-13C Dipolar Network | Broadened resonance lines, low resolution [14] | Spatial dilution of 13C labels to reduce dipolar couplings |

| Homonuclear Decoupling Complexity | Requires multiple-pulse sequences, can reduce sensitivity [14] | Eliminates need for 13C-13C decoupling during acquisition |

| Spectral Overlap in Large Systems | Hinders assignment and structural analysis [20] | Simplifies spectra by reducing J-coupling multiplet structures |

Theoretical Principles and Key Advantages

The fundamental principle behind isotopic isolation is to create a scenario where the probability of two 13C nuclei being directly bonded to each other is statistically low. In a uniformly 13C-labeled sample, the dense network of 13C-13C bonds leads to strong homonuclear dipolar couplings, which are a primary source of line broadening in solid-state NMR spectra of proteins and other biological assemblies [14]. For a 13Cα site to be considered isotopically isolated, it should ideally be bonded to 12Cβ and 12CO nuclei, effectively removing the dominant dipolar coupling partners [14].

The optimal level of random fractional labeling to maximize the population of isolated spins has been quantitatively investigated. Theoretical calculations and experimental data indicate that the maximum probability of obtaining an isolated 13Cα site occurs at a labeling ratio of approximately 25% to 35% [14]. This range represents a sweet spot, providing a sufficient number of NMR-active spins for good sensitivity while keeping the network of dipolar couplings manageable.

The key advantages of employing isotopic isolation include:

- Enhanced Resolution: By minimizing dipolar broadening, isotopic isolation leads to sharper lines, which is critical for resolving signals in complex systems like membrane proteins and amyloid fibrils [14] [21].

- Simplified Experiments: It enables the use of straightforward 13C-detected experiments on stationary aligned samples without the need for sophisticated homonuclear decoupling schemes, thereby improving experimental robustness and sensitivity [14].

- Applicability to Complex Systems: This strategy is particularly valuable for studying large biomolecular complexes where spectral overlap is a major limitation, such as in integral membrane proteins [22] and plant cell walls [23].

Labeling Strategies for Isotopic Isolation

Several biosynthetic labeling strategies can be employed to achieve isotopic isolation, each with specific metabolic consequences and applications.

Random Fractional Labeling

This method involves growing the expression host on a growth medium containing a defined mixture of 12C and 13C carbon sources. Custom algal media can be prepared with specific 13C percentages, such as 15%, 25%, 35%, and 45% [14]. As established, the 25% to 35% range is optimal for creating isolated spins. This approach results in uniform labeling at all carbon sites but to a reduced fractional extent, statistically ensuring that many 13C sites are not directly bonded to another 13C nucleus.

Site-Specific Tailored Labeling

As an alternative to random fractional labeling, specific metabolic precursors can be used to label particular carbon sites within the molecule. This approach leverages the metabolic pathways of the host organism to direct 13C labels to desired positions.

Table: Metabolic Precursors for Tailored Isotopic Labeling

| Labeled Precursor | Primary Labeling Sites | Key Application / Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| [2-13C]-Glucose | Preferentially labels Cα sites in the protein backbone [14] | Effective for studies focusing on protein backbone conformation. Reduces labeling in aliphatic and carbonyl regions [14]. |

| [1,3-13C]-Glycerol | Produces an alternating labeling pattern; specific sites depend on metabolic pathways [14] | Can be used to create specific isolated spin pairs or patterns for dedicated experiments. |

| 13C6-Glucose (Uniform) | Labels all carbon sites uniformly. Used with fractional labeling strategy. | Standard for producing uniform labeling, necessary for comprehensive assignment. |

| 13CO2 | Labels all carbon atoms through photosynthesis [23] | Essential for 13C-labeling of plant materials for solid-state NMR studies of native cell walls [23]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing isotopic isolation in different experimental contexts.

Protocol A: Random Fractional Labeling of Proteins in E. coli

This protocol describes the production of a recombinant protein with random fractional 13C labeling in an E. coli expression system, optimized for solid-state NMR.

- Strain and Plasmid: Transform an appropriate E. coli expression strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)) with a plasmid containing the gene of interest under an inducible promoter (e.g., T7 or autoinduction system [22]).

- Pre-culture: Grow a small overnight culture in a standard, unlabeled rich medium (e.g., LB).

- Cell Transfer and Induction:

- Pellet cells from the pre-culture and resuspend in minimal medium (e.g., M9) supplemented with a carbon source that is a mixture of 12C and 13C-glucose. The 13C fraction should be adjusted to achieve the desired labeling percentage (e.g., 25-35% for optimal isolation [14]).

- Allow the culture to grow until it reaches mid-log phase.

- Induce protein expression by adding IPTG or by leveraging an autoinduction system.

- Harvest and Purification: Harvest cells by centrifugation after the expression period. Proceed with standard protein purification protocols under conditions that maintain the protein's stability and function.

- Sample Preparation for ssNMR: For solid-state NMR, the purified protein must be reconstituted into its functional environment, such as lipid bilayers or vesicles for membrane proteins [22], or other relevant supramolecular complexes. The sample is then packed into a magic-angle spinning (MAS) rotor.

Protocol B: 13C-Labeling of Plant Cell Walls for Structural Studies

This protocol outlines a cost-effective method for achieving sufficient 13C-enrichment (~60%) in plant materials for multi-dimensional solid-state NMR analysis of native cell wall architecture [23].

- Surface Sterilization: Sterilize de-husked rice seeds (or other plant species) by sequential treatment with 70% ethanol for 5 minutes and 40% Clorox solution for 15 minutes, followed by extensive washing with sterile distilled water.

- Germination on 13C-Glucose:

- Place the sterilized seeds on jars containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media supplemented with 1% (w/v) 13C-labeled glucose.

- Incubate at 22°C under continuous light for 4-5 days until germination.

- 13CO2 Supplementation:

- Transfer the jars to a dry-seal vacuum-desiccator.

- Connect a vacuum pump to the desiccator and apply a vacuum for approximately 2 minutes to remove 1L of air.

- Introduce 1L of 13CO2 from a low-pressure cylinder (collected in a balloon) into the desiccator via the sleeve valve.

- Grow the seedlings under continuous light for an additional 2 weeks within the sealed desiccator.

- Harvest and Sample Preparation: Harvest the plant tissue. For ssNMR, pack the native, never-dried plant tissue directly into a 3.2 mm MAS rotor, maintaining its natural hydration state [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of isotopic isolation experiments requires a set of key reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions for these protocols.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Isotopic Isolation Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Glucose (Uniform or Site-Specific) | Carbon source for bacterial growth and metabolic labeling. [2-13C]-glucose preferentially labels protein backbone Cα atoms. [14] | Production of fractionally or site-specifically labeled proteins in E. coli. |

| 13C-Glycerol (e.g., [1,3-13C]) | Alternative carbon source leading to different, tailored labeling patterns via metabolic pathways. [14] | Creating specific isotopic isolation patterns for dedicated NMR experiments. |

| 13CO2 Gas | Essential for photosynthetic 13C incorporation in plants. [23] | Labeling plant cell walls for structural studies of native biomass. |

| Defined Minimal Media (e.g., M9) | Supports bacterial growth with a defined carbon source, essential for controlled isotopic incorporation. [22] | Serves as the base for creating custom fractional or site-specific labeling media. |

| Specialized Growth Chamber / Vacuum Desiccator | Enclosed environment for efficient delivery and recycling of expensive 13CO2 during plant growth. [23] | Cost-effective 13C-labeling of plant materials as described in Protocol B. |

Data Analysis and Expected Outcomes

When isotopic isolation is successfully achieved, the solid-state NMR spectra will exhibit characteristic improvements. The most significant outcome is a reduction in linewidth and the collapse of J-coupling multiplets into singlets, leading to a substantial increase in effective resolution [20]. For example, in a 2D 13C-13C correlation spectrum of a protein, the cross-peaks corresponding to isolated 13Cα sites will appear as sharp, well-defined singlets instead of broadened multiplets, even without the application of homonuclear J-decoupling sequences.

The efficacy of the labeling scheme can be quantified by analyzing solution NMR spectra of the solubilized protein. A combination of 2D projections from three-dimensional heteronuclear solution NMR spectra can be used to quantify the 13C enrichment at specific sites (Cα, Cβ, CO) and confirm the desired isolation pattern [14]. In a sample grown on [2-13C]-glucose, for instance, solution NMR will show a greater extent of 13C labeling in the Cα region (45-65 ppm) and reduced labeling in the aliphatic, aromatic, and carbonyl regions compared to a uniformly labeled sample [14].

Advanced Applications and Integration with Modern Techniques

The principle of isotopic isolation remains highly relevant when integrated with modern NMR technological advances. For instance, it is fully compatible with high-field magic-angle spinning (MAS) instrumentation, which itself helps attenuate homonuclear dipolar couplings [21]. Furthermore, isotopic isolation can be combined with optimal control theory-designed decoupling pulses, such as those that avoid Bloch-Siegert shifts (e.g., BADCOP pulses), to achieve the dual benefits of simplified spin systems and highly accurate resonance frequencies [24].

This strategy is particularly powerful in the study of complex biological assemblies that are intractable by other methods, including:

- Integral Membrane Proteins (IMPs): Isotopic labeling is a major avenue to simplify the overlapped spectra of IMPs, which are crucial for cellular functions but difficult to study [22].

- Amyloid Fibrils: Mixed and tailored labeling strategies are essential for reducing spectral complexity in these repetitive structures, allowing for the disambiguation of inter- and intra-molecular distance restraints [21].

- Native Plant Cell Walls: The simplified spectra resulting from isotopic isolation enable the detailed analysis of polysaccharide-polysaccharide interactions in their native state, informing biomass optimization efforts [23].

Determining the Optimal Labeling Percentage for Spatial Isolation

Spatial isolation, achieved through controlled 13C isotopic labeling, is a critical strategy for simplifying complex Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra and enabling the study of challenging biological systems. The core principle involves diluting the 13C isotopes within molecules to reduce the strong dipolar couplings and J-couplings that cause signal broadening in uniformly labeled samples. However, the labeling percentage must be carefully optimized to balance the conflicting demands of spectral sensitivity and spectral resolution. This application note provides a structured framework, complete with quantitative data and detailed protocols, to guide researchers in determining the optimal 13C enrichment level for their specific experimental needs in structural biology and drug development.

The choice of labeling strategy directly influences the cost, complexity, and outcome of an NMR study. The table below summarizes the primary labeling approaches relevant to spatial isolation.

Table 1: Common 13C Labeling Strategies for NMR Spectroscopy

| Labeling Strategy | Typical 13C Enrichment | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform Labeling | > 99% [3] | Multi-dimensional NMR of proteins/metabolites | Maximizes sensitivity for structure determination |

| Random Fractional Labeling | 25% - 60% [3] [23] | Spectral simplification (Spatial Isolation) | Reduces linewidths by weakening 13C-13C couplings |

| Positional Labeling | Specific positions > 99% [25] | Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Probes specific metabolic pathways |

The optimal labeling percentage is a system-dependent parameter. The following table consolidates empirical findings from recent studies, providing a starting point for experimental design.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Optimal Labeling Percentages

| System Studied | Optimal 13C Labeling | Observed Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eukaryotic Membrane Protein (LR) | ~25% [3] | 50% reduction in 13C linewidth; 50% increase in well-resolved cross-peaks | [3] |

| Plant Cell Wall (Rice) | ~60% [23] | Sufficient for high-resolution 2D/3D correlation ssNMR experiments | [23] |

Figure 1: The trade-off between spectral resolution and sensitivity governed by the 13C labeling percentage. The primary goal of spatial isolation is to achieve narrower linewidths, which favors a lower labeling percentage.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Random Fractional Labeling of a Membrane Protein inP. pastoris

This protocol is adapted from a study on the eukaryotic membrane protein LR (Leptosphaeria maculans rhodopsin) and is ideal for producing samples for Solid-State NMR (ssNMR) [3].

1. Principle: The P. pastoris expression system utilizes methanol as a sole carbon source. By feeding a controlled mixture of 13C-methanol and natural abundance methanol, the expressed protein is randomly and sparsely labeled with 13C, achieving spatial isolation [3].

2. Required Reagents and Materials:

- P. pastoris strain expressing the target membrane protein.

- Natural abundance methanol.

- 13C-methanol (99% atom 13C).

- Standard growth media (e.g., Minimal Glycerol Medium, MGY; Minimal Methanol Medium, MM).

- Buffers for protein purification.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Culture Inoculation. Inoculate a starter culture in MGY and grow overnight at 28-30°C with shaking until saturation.

- Step 2: Induction and Labeling. Pellet the cells from the starter culture and resuspend them in MM supplemented with a specific ratio of 13C-methanol to natural abundance methanol. For a target of ~25% enrichment, use a 1:3 (v/v) mixture of 13C-methanol:NA-methanol [3].

- Step 3: Protein Expression. Induce protein expression by continuing incubation for 24-72 hours at 28-30°C. Maintain labeling by adding the same methanol mixture as needed.

- Step 4: Harvest and Purify. Harvest the cells by centrifugation. Proceed with standard membrane protein purification protocols, including cell lysis, membrane isolation, and solubilization with a suitable detergent (e.g., DDM).

- Step 5: NMR Sample Preparation. Concentrate the purified protein and prepare the ssNMR sample by packing it into a magic-angle spinning (MAS) rotor.

4. Expected Results and Analysis:

- Compare 1D-13C and 2D 15N-13C correlation spectra of samples with different labeling percentages (e.g., 100%, 50%, 25%).

- A 25% enrichment should yield an average 13C linewidth that is approximately half that of a uniformly (100%) labeled sample [3].

- This will manifest as a significant increase (e.g., 50%) in the number of well-resolved cross-peaks in 2D spectra.

Protocol B: Uniform 13C-Labeling of Plant Cell Walls for ssNMR

This protocol describes a cost-effective method for achieving ~60% 13C enrichment in plant seedlings, suitable for multi-dimensional ssNMR studies of cell wall architecture [23].

1. Principle: Plants are autotrophs that fix carbon from CO2. This protocol uses a dual-labeling approach, supplying 13C-glucose through the growth media and 13CO2 gas to the atmosphere within a sealed chamber, resulting in high but sub-stoichiometric enrichment [23].

2. Required Reagents and Materials:

- Rice seeds (Oryza sativa).

- Half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media.

- 13C-labeled glucose.

- 13CO2 gas (99.0 atom % 13C).

- A dry-seal vacuum-desiccator (∼2.2 L volume) with sleeve valves.

- Vacuum pump and gas collection balloon.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Surface Sterilization. Sterilize de-husked rice seeds with 70% ethanol followed by a 40% Clorox solution, then wash thoroughly with sterile ddH2O [23].

- Step 2: Germination on 13C-Glucose. Place the sterile seeds on jars containing half-strength MS media supplemented with 1% (w/v) 13C-labeled glucose. Incubate at 22°C under continuous light for 4-5 days until germination [23].

- Step 3: 13CO2 Supplementation. Transfer the jars to the vacuum-desiccator. Connect a balloon filled with 1L of 13CO2 gas to a sleeve valve. Briefly apply a vacuum to the desiccator (e.g., for ~2 minutes) to remove an equivalent volume of air, then release the 13CO2 from the balloon into the chamber [23].

- Step 4: Seedling Growth. Grow the seedlings for 2 weeks under continuous light inside the sealed desiccator containing the 13CO2-enriched atmosphere.

- Step 5: Harvest and NMR Analysis. Harvest the plant tissue. For ssNMR, pack the native, never-dried tissue directly into a 3.2 mm MAS rotor [23].

4. Expected Results and Analysis:

- 1D 13C Cross-Polarization (CP) spectra will confirm successful labeling.

- A 60% enrichment level is sufficient to acquire high-quality 2D and 3D 13C-13C correlation spectra (e.g., through-space or through-bond experiments) to resolve polysaccharide signals in the plant cell wall [23].

Data Analysis and Validation

Spectral Analysis for Labeling Efficiency

The effectiveness of spatial isolation is quantitatively assessed by measuring spectral parameters.

- Linewidth Measurement: Measure the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of 13C signals in 1D or 2D spectra. A successful protocol will show a significant reduction in FWHM compared to a uniformly labeled control [3].

- Signal Resolution: Count the number of resolvable cross-peaks in a 2D 15N-13C or 13C-13C spectrum. An increase in distinct peaks indicates improved spectral resolution due to reduced overlap and broadening [3].

Indirect Quantification via 1H NMR

For high-throughput analysis, 13C enrichment can be indirectly quantified using 1H NMR, which offers greater sensitivity and shorter experiment times [26].

- Principle: A proton that is directly bonded to a 13C nucleus has a different chemical shift than one bonded to a 12C nucleus due to the one-bond J-coupling. This splits the 1H signal into a doublet (for 13C-bound H) and a central singlet (for 12C-bound H) [26].

- Method: Acquire a 1H NMR spectrum with and without 13C decoupling. Without decoupling, the fractional 13C enrichment can be calculated from the ratio of the intensity of the 13C-satellite signals (the doublet) to the total signal intensity for that specific proton [26].

- Application: This method is highly useful for rapid analysis of metabolic incorporation from 13C-labeled precursors like [1,6-13C]glucose in cell lysates or media [26].

Figure 2: A workflow for analyzing NMR data to determine the optimal labeling percentage, involving direct measurement of spectral quality metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for 13C-Labeling Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Usage | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Methanol | Carbon source for random fractional labeling in methylotrophic yeast. | Used in P. pastoris system for sparse labeling of membrane proteins. | [3] |

| 13C-Glucose / 13CO2 | Carbon source for uniform or high-level labeling in plants, bacteria, and cell cultures. | Dual-labeling of rice seedlings for plant cell wall ssNMR. | [23] |

| Specialized Growth Chambers | Enclosed system for efficient 13CO2 utilization and containment. | Vacuum-desiccator used for cost-effective plant labeling. | [23] |

| Magic-Angle Spinning (MAS) Probes | Essential hardware for high-resolution Solid-State NMR. | Used for data acquisition on native plant tissues and membrane proteins. | [3] [23] |

| NMR Processing Software (e.g., CcpNmr) | Facilitates spectral analysis, assignment, and chemical shift perturbation analysis. | Used for backbone assignment and interaction studies in solution NMR. | [27] |

Metabolic Pathways and Incorporation Patterns in Bacterial Expression Systems

The precise analysis of metabolic pathways is a cornerstone of modern microbiology and biotechnology, enabling advances in therapeutic protein production, antibiotic development, and fundamental cellular research. 13C-isotope labeling combined with Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful methodology for elucidating these pathways and incorporation patterns within bacterial systems. This approach leverages the magnetic properties of the 13C isotope, which possesses nuclear spin unlike the more abundant 12C isotope, making it detectable by NMR [28] [29]. While multidimensional solid-state NMR (ssNMR) provides exceptional structural and dynamic information, its widespread application has been limited by the low natural abundance of 13C (1.1%) and the consequent challenges in achieving sufficient sensitivity [23]. This application note details streamlined protocols for efficient 13C-labeling in biological systems and its application in tracing metabolic fluxes within bacterial expression platforms, providing researchers with practical tools for advanced metabolic analysis.

Theoretical Background: 13C-NMR in Metabolic Analysis

NMR spectroscopy functions on the principle that nuclei with a non-zero spin, when placed in an external magnetic field, can absorb electromagnetic radiation at characteristic frequencies [28]. For 13C-NMR, the subsequent absorbed frequency of carbon nuclei is influenced by their immediate electronic environment—a phenomenon known as nuclear shielding—which causes slight shifts in resonance frequency termed chemical shifts (δ, measured in ppm) [28]. This sensitivity to chemical environment allows researchers to distinguish between different carbon atoms within a metabolite, thereby providing a fingerprint of molecular structure and identity.

The application of 13C-enrichment strategies dramatically enhances the sensitivity of NMR detection. It enables the use of sophisticated correlation experiments (e.g., 2D and 3D 13C-13C correlation spectra) that are essential for resolving complex metabolic mixtures and tracing the incorporation of labeled precursors into downstream metabolites [23] [29]. In metabolic pathway analysis, feeding bacteria with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose, bicarbonate) results in the incorporation of the label into various metabolic intermediates and end-products. The specific pattern of labeling, detected via NMR, reveals the activity and connectivity of the underlying metabolic pathways [29].

A Simplified and Efficient Protocol for 13C-Labeling

The following protocol, adapted from a recent plant cell wall study, provides a cost-effective and accessible method for achieving high levels of 13C-enrichment. While originally developed for plant seedlings, its principles are readily transferable to bacterial and other biological expression systems with appropriate modifications to growth support [23].

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for 13C-Labeling Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Source/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled Glucose | Carbon source for metabolic labeling; incorporated via central carbon metabolism | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (CLM-1396-PK) [23] |

| 13C-labeled Bicarbonate | Carbon source for photosynthetic organisms and autotrophic bacteria; precursor for CO2 fixation | Sigma-Aldrich [29] |

| 13CO2 Gas | Labeling via gaseous carbon delivery for closed systems | Sigma-Aldrich (cat# 364592-1L) [23] |

| Murashige and Skoog (MS) Media | Defined plant growth medium; analogous to defined minimal media for bacteria | Sigma-Aldrich [23] |

| f/2+Si Medium | Defined marine algae growth medium | [29] |

| Methanol-Chloroform Solvent System | Extraction of metabolites and lipids for NMR analysis (Bligh & Dyer method) [29] | N/A |

| Vacuum Desiccator | Sealed chamber system for efficient 13CO2 labeling | [23] |

Step-by-Step Labeling Protocol

Step 1: System Preparation and Sterilization Begin with standard sterile microbiological techniques. For bacterial cultures, prepare a defined minimal medium containing essential salts, vitamins, and a non-labeled carbon source suitable for the specific bacterial expression system. If adapting the plant protocol, surface-sterilize the starting biological material (e.g., bacterial pellets, cell lines) using appropriate sterilants like ethanol and diluted sodium hypochlorite, followed by multiple washes with sterile water [23].

Step 2: Initial Growth Phase with 13C-Labeled Precursor Incorporate a 13C-labeled carbon source directly into the growth medium. Resuspend or inoculate the biological material in this medium. The referenced plant protocol used 1% (w/v) 13C-labeled glucose [23]. For bacterial cultures, the concentration may require optimization. Incubate under standard growth conditions for an initial period to allow for uptake and initial metabolism of the label.

Step 3: Supplemental 13CO2 Labeling (Optional) For systems requiring or benefiting from CO2, a sealed chamber like a vacuum-desiccator can be used. After initial growth, transfer the cultures to the desiccator.

- Vacuum Application: Briefly apply a vacuum (e.g., ~2 minutes) to remove ambient air [23].

- 13CO2 Introduction: Release 13CO2 from a low-pressure cylinder or a pre-filled balloon into the desiccator to maintain a labeled atmosphere [23].

- Continued Incubation: Grow the cultures within the sealed, 13CO2-enriched atmosphere for the desired duration (e.g., 2 weeks in the plant study) [23].

Step 4: Harvesting and Sample Preparation for NMR

- Harvesting: Collect the cells by centrifugation. The referenced protocol for algae and bivalves involved centrifugation at 800-3000 rcf for 10 minutes at 4°C [29].

- Metabolite Extraction: Use a methanol-chloroform extraction (Bligh & Dyer method) for comprehensive metabolite and lipid recovery.

- Homogenize the cell pellet in a methanol-water mixture [29].

- Add chloroform and water, vortex, and let the phases separate [29].

- Recover the upper methanol-water layer (containing hydrophilic metabolites) and the lower chloroform layer (containing lipids) separately.

- Dry both fractions completely using a vacuum concentrator or under a gentle nitrogen stream [29].

- NMR Sample Preparation: Resuspend the dried extracts in a suitable deuterated NMR solvent (e.g., D2O for hydrophilic metabolites, CDCl3 for lipids) and transfer to an NMR rotor or tube.

Expected Outcomes and Efficiency

This integrated labeling approach has been demonstrated to achieve approximately 60% 13C-enrichment in target tissues, a level sufficient for high-resolution 2D and 3D correlation ssNMR experiments [23]. The efficiency makes detailed structural and flux analysis accessible without requiring prohibitively large quantities of expensive 13CO2.

Workflow and Data Analysis

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines the key stages of a 13C-labeling experiment, from preparation to data interpretation.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis Using Computational Tools

Beyond direct experimental analysis, computational prediction of metabolic pathways from genomic data is an invaluable complementary tool. Software like gapseq uses hidden Markov models (HMMs) to search for homologs of key enzymes in bacterial proteomes, enabling the reconstruction of an organism's metabolic network and the prediction of pathways for energy reserves like glycogen, polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), and wax esters [30] [31]. A systematic analysis of 8282 bacterial proteomes revealed that the presence or absence of such pathways is often correlated with bacterial lifestyle (e.g., parasitic vs. free-living) and genome size [30].

Table 2: Key Enzymes as Markers for Major Bacterial Energy Reserve Pathways [30]

| Energy Reserve Pathway | Key Enzyme | Gene | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycogen Metabolism | Glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase | glgC | Commits glucose to glycogen synthesis |

| Glycogen Metabolism | Glycogen synthase | glgA | Extends the glycogen chain |

| Polyphosphate (polyP) Metabolism | Polyphosphate kinase | ppk1 | Synthesizes polyP from ATP |

| Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) Metabolism | PHA synthase | phaC | Polymerizes PHA granules |

| Wax Ester/Triacylglycerol Synthesis | Wax ester synthase/Acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase | wax-dgaT | Catalyzes final step in neutral lipid synthesis |

NMR Data Interpretation and Pathway Mapping

The final stage involves correlating NMR spectral data with metabolic pathways. The chemical shifts of 13C atoms in detected metabolites serve as direct evidence of specific metabolic activities. For instance, tracking the incorporation of 13C from labeled bicarbonate or glucose into fatty acids like eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) or various carbohydrates allows researchers to map active pathways and their fluxes [29]. This is particularly useful for studying environmental effects, such as how temperature shifts alter energy conversion—for example, observing a reduction in unsaturated fatty acids and increased label incorporation into sugars at higher temperatures [29]. The diagram below illustrates the logical flow from raw genomic data to a functional metabolic model.

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

- Maximizing Labeling Efficiency: The combination of a liquid 13C-precursor (e.g., glucose) with a gaseous precursor (13CO2) in a sealed system can significantly boost overall enrichment compared to using a single source [23].

- Adapting for Bacterial Systems: When applying this protocol to bacteria, the growth medium (e.g., LB, minimal M9) must be selected and potentially adapted to support the specific bacterial strain and research objective. The incubation times will be considerably shorter than for plant seedlings.

- NMR Experiment Selection: For uniformly 13C-labeled samples at ~60% enrichment, a wide range of 2D and 3D ssNMR experiments become feasible. Start with 1D 13C cross-polarization (CP) spectra and proceed to 2D 13C-13C correlation experiments for detailed structural and flux analysis [23].

- Validating Computational Predictions: Tools like gapseq have been shown to outperform others in predicting enzyme activity and carbon source utilization [31]. These in silico predictions should be used to guide experimental design and then validated with empirical 13C-NMR data.

Practical Implementation: From Hardware to Spectral Acquisition

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy utilizing 13C-labeled substrates represents a powerful technique for non-invasively measuring metabolic fluxes in living systems, from cultured cells to intact organisms [32]. The method enables researchers to track the incorporation of 13C labels from specific substrates into metabolic products, providing unprecedented insight into pathway dynamics and compartmentalized metabolism. 13C NMR spectroscopy has been instrumental in quantifying neurotransmitter cycling, evaluating substrate importance across tissues, and establishing relationships between energy metabolism and cellular function [32] [33]. The technique's implementation requires careful consideration of NMR hardware configuration, particularly the choice between direct 13C-[1H] and indirect 1H-[13C] NMR detection schemes, each with distinct advantages for specific experimental scenarios.

The fundamental challenge in 13C-based NMR arises from the low natural abundance (1.1%) and intrinsic sensitivity of the 13C nucleus, which necessitates both specialized hardware and isotopic enrichment strategies [1] [34]. Furthermore, the application of in vivo 13C NMR presents additional methodological hurdles including the need for broadband decoupling of 13C-1H J-couplings, large chemical shift dispersion, low sensitivity, and precise signal localization [33]. This application note provides comprehensive guidance for establishing a functional heteronuclear NMR system, with particular emphasis on RF coil configurations, console requirements, and experimental protocols for 13C labeling experiments.

NMR System Hardware Configuration

Essential System Components

A functional heteronuclear NMR system for 13C labeling studies requires several non-standard hardware components that extend beyond conventional 1H NMR capabilities [32]. The core requirements include:

- Dual-Frequency RF Coil: A 13C-[1H] or 1H-[13C] RF coil capable of simultaneous operation at both 13C and 1H frequencies

- RF Filters: Specialized filters to prevent noise injection between channels during decoupling

- Multi-Nucleus Console: A console capable of handling two frequencies simultaneously with appropriate transmitter and receiver chains

- High-Power Amplifiers: Sufficient RF power for broadband decoupling sequences

Table 1: Core NMR System Requirements for Heteronuclear Experiments

| Component | Specification | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF Coil | Dual-tuned 13C-[1H] or 1H-[13C] configuration | Signal excitation and detection | Geometric arrangement critical for minimal coil interaction |

| Console | Multi-nucleus capability with dual channels | Sequence generation and data acquisition | Must handle both 13C and 1H frequencies simultaneously |

| RF Filters | Low-pass and high-pass configurations | Prevent noise injection during decoupling | Minimum 60 dB attenuation at opposing frequency [32] |

| Amplifiers | High peak and average power capability | Support decoupling sequences | Must handle kW-level peak power for 1-5 ms pulses |

RF Coil Design and Configuration

The RF coil represents perhaps the most critical component in the heteronuclear NMR setup. The most commonly employed design for in vivo applications, as originally described by Adriany and Gruetter, features a geometrically optimized configuration that minimizes interaction between the 13C and 1H components [32]. As illustrated in Figure 1, this design incorporates:

- A simple circular surface coil (14-80 mm diameter for rodent-human studies) for 13C detection

- Two larger surface coils (21-130 mm diameter) placed at approximately 90° relative to each other and driven in quadrature for 1H operation

- Spatial arrangement where the sensitive volume of the 1H RF coil exceeds that of the 13C coil to ensure effective decoupling throughout the detected volume