A Modern Guide to 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: Protocol, Applications, and Best Practices

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is the gold-standard technique for quantifying intracellular reaction rates in living cells, providing critical insights into cellular physiology for metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and disease research.

A Modern Guide to 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis: Protocol, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is the gold-standard technique for quantifying intracellular reaction rates in living cells, providing critical insights into cellular physiology for metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and disease research. This article provides a comprehensive guide to 13C-MFA, covering its foundational principles from isotopic tracer design to flux calculation. It details a modern high-resolution protocol utilizing parallel labeling experiments and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for precise flux quantification. The guide also addresses advanced topics including model selection, statistical validation, and troubleshooting common pitfalls, with a specific focus on applications in cancer biology and drug development. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging methodologies, this resource aims to equip researchers with the knowledge to design, execute, and interpret robust 13C-MFA studies.

Understanding 13C-MFA: Core Principles and Its Role in Quantitative Metabolism

What is 13C-MFA? Defining Metabolic Fluxes and Their Importance

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a powerful model-based technique for quantifying the in vivo rates of metabolic reactions in living cells. By tracing the path of stable 13C isotopes from labeled substrates through metabolic networks, it provides a quantitative map of cellular metabolism, reflecting the functional phenotype of a biological system under specific conditions [1] [2].

The Principle of 13C-MFA

At its core, 13C-MFA involves feeding cells a substrate labeled with 13C at specific carbon positions. As the cells metabolize this tracer, 13C atoms are distributed through metabolic pathways in a manner dictated by the intracellular reaction rates, or fluxes. The resulting labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites are measured using techniques like Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) [3] [2].

These isotopic labeling data alone are complex and cannot be intuitively interpreted to reveal flux maps. Therefore, a mathematical model of the metabolic network is used to simulate the labeling patterns. Fluxes are estimated by performing a least-squares regression, iteratively adjusting the fluxes in the model until the simulated labeling patterns best match the experimental measurements [3] [2] [4]. This process can quantify fluxes through parallel pathways, metabolic cycles, and reversible reactions, providing a comprehensive view of metabolic activity [1].

Importance and Applications

Quantifying metabolic fluxes is crucial because they represent the final, integrated outcome of cellular regulation, encompassing gene expression, protein levels, and metabolic control. 13C-MFA has become a standard tool in various fields [1] [3]:

- Metabolic Engineering: Guiding the optimization of microbial cell factories for the high-yield production of biofuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals [5].

- Biomedical Research: Uncovering metabolic rewiring in diseases like cancer, identifying critical pathway dependencies for potential therapeutic targeting [3].

- Systems Biology: Providing quantitative data for constructing and validating genome-scale metabolic models [1].

- Basic Research: Elucidating the regulation of metabolic networks in response to genetic or environmental perturbations [6].

Experimental and Computational Workflow

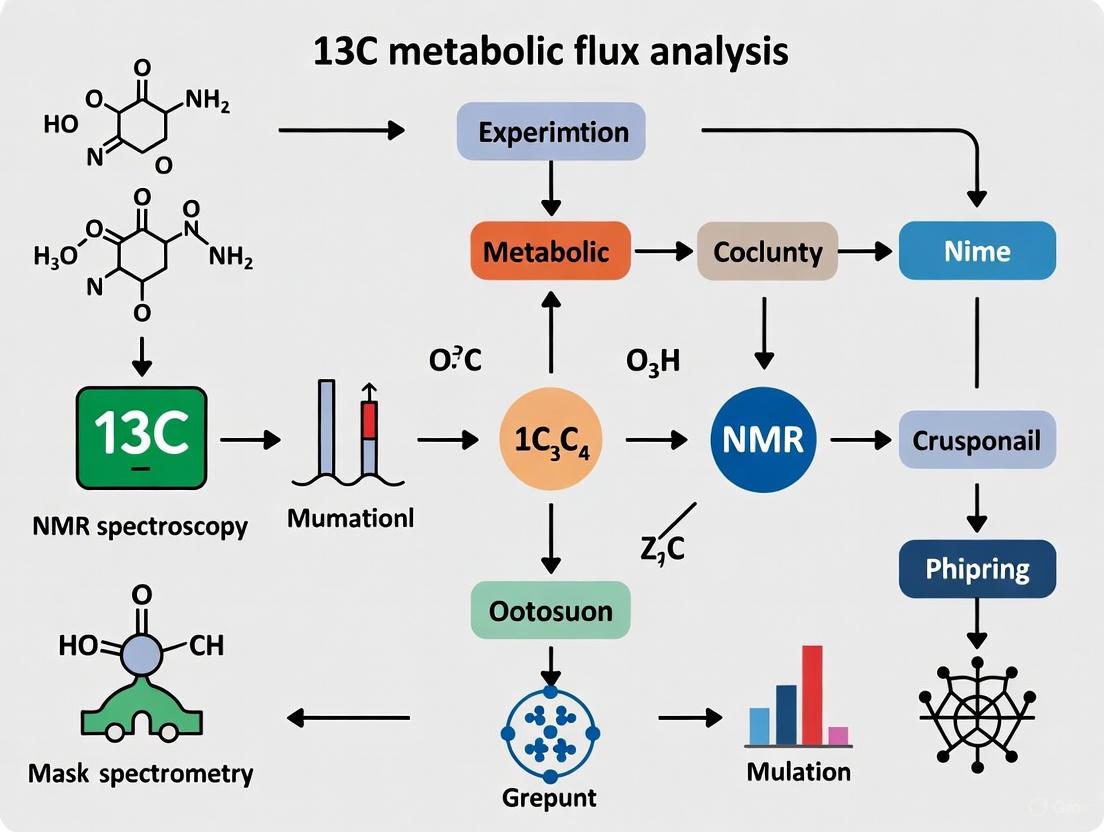

A complete 13C-MFA study follows a multi-step workflow, integrating experimental biology with computational modeling. The key stages are summarized in the diagram below and detailed in the subsequent table.

Diagram 1: The integrated workflow of a 13C-MFA study, showing the key experimental and computational phases.

Table 1: Detailed breakdown of the 13C-MFA workflow.

| Workflow Stage | Key Activities | Protocol Details & Best Practices |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Experiment Design | Selecting appropriate 13C-labeled tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine). Designing parallel labeling experiments (PLEs) using different tracers to improve flux resolution [5] [7]. | The choice of tracer is critical. For central carbon metabolism, 13C-glucose and 13C-glutamine are common. PLEs integrate data from multiple tracers into a single model, greatly enhancing the precision of flux estimates [5]. |

| 2. Cell Culturing & Sampling | Growing cells in media with the 13C tracer under controlled conditions. Sampling the culture during exponential growth to ensure metabolic and isotopic steady state [3]. | Cells are typically harvested in mid-exponential phase. For steady-state MFA, it is crucial to ensure that isotopic labeling in metabolite pools has reached equilibrium, which may take several cell doublings [3] [2]. |

| 3. Analytical Measurements | a) External Rates: Measuring substrate consumption and product secretion rates, and calculating the cellular growth rate (µ) [3].b) Isotopic Labeling: Quenching metabolism and analyzing mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of metabolites via GC-MS or LC-MS [1] [5]. | External fluxes are calculated from concentration changes and growth rates [3]. MIDs are measured from protein-bound amino acids or intracellular metabolite pools. Reporting uncorrected raw data is a key good practice [1]. |

| 4. Data Integration & Flux Estimation | Constructing a stoichiometric metabolic network model. Using software to fit the model to the combined dataset (external rates + MIDs) and estimate the most likely intracellular flux map [3] [2]. | The model includes atom transition information for each reaction. Software platforms like Metran, INCA, 13CFLUX, and Iso2Flux are used for the computationally intensive fitting process [3] [6] [8]. |

| 5. Statistical Validation | Evaluating the goodness-of-fit (e.g., with a χ²-test). Calculating confidence intervals for the estimated fluxes. Performing model selection to identify the most appropriate network topology [1] [4]. | This step ensures the model is statistically sound and that fluxes are reported with their precision. Validation-based model selection using independent data is a robust method to prevent overfitting [4] [9]. |

Classification of 13C-MFA Methods

The 13C-MFA framework encompasses several methodologies, tailored for different biological scenarios. The primary classification is based on the dynamic states of the metabolism and the isotopic labeling.

Table 2: Categories of 13C-based flux analysis methods.

| Method | Applicable Scenario | Key Principle | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA) | Systems where metabolic fluxes and isotopic labeling are constant. | Fits a model to MIDs measured at isotopic steady state. The most established and widely used method [2]. | Medium |

| Isotopically Instationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA) | Systems where fluxes are constant but isotopic labeling is still changing (dynamic). | Fits a model to time-course labeling data, without waiting for isotopic steady state. Ideal for systems with slow turnover [2]. | High |

| Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP) | Systems with constant fluxes and dynamic labeling. | Estimates absolute fluxes through sequential linear reactions based on the kinetics of label incorporation into metabolite pools [2]. | Medium |

| 13C Flux Ratios | Any system with labeling data. | Calculates relative flux contributions at metabolic branch points from specific labeling patterns, without requiring a full network model [2]. | Low to Medium |

| Parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA) | When 13C data alone does not yield a unique solution. | Performs a secondary optimization to find the flux solution that minimizes the total sum of fluxes, optionally weighted by gene expression data [6]. | Medium |

Essential Reagents and Software Toolkit

Successful implementation of 13C-MFA relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and software for 13C-MFA.

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-labeled Glucose (e.g., [1,2-13C], [U-13C]) | Tracing glycolysis, Pentose Phosphate Pathway, and TCA cycle fluxes [3] [7]. |

| 13C-labeled Glutamine (e.g., [U-13C]) | Essential for analyzing glutaminolysis, TCA cycle anaplerosis, and redox metabolism in cancer cells [3] [7]. | |

| Analytical Instruments | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Workhorse for measuring mass isotopomer distributions of amino acids from hydrolyzed protein or organic acids [5] [7]. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Used for measuring isotopic labeling of a wider range of intracellular metabolites with high sensitivity [7]. | |

| Software Platforms | INCA, Metran | User-friendly software suites that implement the EMU framework for efficient flux estimation [3] [5]. |

| 13CFLUX, Iso2Flux | High-performance software platforms for both stationary and instationary 13C-MFA [6] [8]. | |

| Isodyn | Software designed to simulate the dynamics of metabolite labeling, suitable for INST-MFA [10]. |

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) serves as a foundational technique in systems biology for quantifying the in vivo conversion rates of metabolites within living cells. Metabolic flux refers to the rate of enzymatic reactions and transport processes between different cellular compartments, providing crucial information for understanding how cells allocate resources for growth and maintenance in response to environmental changes [11]. By tracing the fate of 13C-labeled atoms from specific substrates through complex metabolic networks, researchers can move beyond static metabolic maps to obtain dynamic, quantitative flux maps that reveal the actual activity of metabolic pathways under specific physiological conditions [11] [12]. This methodology has evolved beyond a single technique into a diverse family of methods that has become the "gold standard" for flux quantification under metabolic quasi-steady state conditions, contributing significantly to quantitative characterization of organisms across biotechnology and health-related research [12] [13].

The fundamental principle underlying 13C-MFA is that the distribution of 13C labels in intracellular metabolites is highly sensitive to the relative flow of carbon through different pathways [14]. When cells are fed specifically designed 13C-labeled substrates, the resulting labeling patterns in metabolic products provide a rich set of constraints that can be used to calculate intracellular reaction rates. The technology plays an indispensable role in understanding intracellular metabolism and revealing pathophysiology mechanisms, with applications ranging from metabolic engineering of industrial microorganisms to investigating metabolic alterations in disease states [11] [12].

Core Principles and Methodological Framework

Theoretical Foundation of Flux Determination

The core principle of 13C-MFA rests on the relationship between the isotopic distribution of substrates and the resulting labeling patterns of intracellular metabolites, which is mathematically determined by the metabolic flux values. The flux estimation process can be formalized as an optimization problem where the goal is to find the flux values that minimize the difference between the experimentally measured isotopic labeling patterns and those predicted by a computational model of the metabolic network [11]. This relationship is captured in the equation:

Where v represents the vector of metabolic fluxes, S is the stoichiometric matrix of the metabolic network, M⋅v ≥ b provides additional constraints from physiological parameters, and the differential equations describe the dynamics of the isotope labeling model [11].

The power of 13C-MFA stems from the data richness provided by isotopic labeling measurements. A typical tracer experiment generates 50 to 100 isotopic labeling measurements to estimate only 10 to 20 independent metabolic fluxes. This significant redundancy greatly improves the accuracy of flux estimation and enhances confidence in the results compared to traditional metabolic flux analysis based only on material balances [14].

Classification of 13C Fluxomics Methods

The field of 13C fluxomics has diversified into several specialized methodologies, each with distinct applications and capabilities:

Qualitative Fluxomics (Isotope Tracing): This approach involves feeding isotope-labeled tracers and tracking the variation in isotopic patterns of metabolites to deduce qualitative pathway activity changes without rigorous quantification [11].

13C Flux Ratios: Based on differences between isotopic compositions of metabolic precursors and products, this method directly calculates the relative fraction of metabolic fluxes converging at metabolic nodes, which is particularly valuable when overall network topology is unclear [11].

13C Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP): KFP assumes that the labeled fraction of metabolite pools changes exponentially during labeling and can estimate absolute fluxes through sequential linear reactions, making it suitable for quantifying fluxes within subnetworks [11].

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): As the most comprehensive approach, 13C-MFA determines absolute flux values throughout global metabolic networks by optimally fitting isotopic labeling values of measured metabolites [11].

COMPLETE-MFA: This advanced methodology combines multiple parallel labeling experiments to improve both flux precision and observability, allowing resolution of more independent fluxes with smaller confidence intervals [15].

Table 1: Comparison of 13C Fluxomics Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Applications | Quantitative Rigor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Fluxomics | Tracking label distribution without rigorous quantification | Pathway discovery, preliminary assessment | Low |

| 13C Flux Ratios | Calculating relative flux fractions at metabolic nodes | Analysis when network topology is incomplete | Medium |

| Kinetic Flux Profiling | Modeling exponential labeling of metabolite pools | Subnetwork flux analysis, kinetic parameters | Medium-High |

| 13C-MFA | Global fitting of labeling patterns to determine absolute fluxes | Comprehensive flux maps, metabolic engineering | High |

| COMPLETE-MFA | Integrated analysis of multiple parallel labeling experiments | High-resolution flux mapping, model validation | Very High |

Experimental Design and Protocol

Tracer Selection and Experimental Configuration

The foundation of a successful 13C-MFA study lies in the careful selection of appropriate isotopic tracers. The choice of 13C-labeled substrate depends on the target microorganism and experimental objectives, with different tracers providing varying levels of resolution for different metabolic pathways [12]. For accurate elucidation of flux distributions, a well-studied glucose mixture containing 80% [1-13C] and 20% [U-13C] glucose (w/w) is often used as it guarantees high 13C abundance in various metabolites [12]. However, pure singly labeled carbon substrates can be more suitable for discovering novel pathways because they simplify tracing of labeled carbons in metabolic intermediates [12].

Recent advances in tracer design have revealed that no single tracer optimally resolves all fluxes in a metabolic network. Tracers that produce well-resolved fluxes in upper metabolism (glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathways) often show poor performance for fluxes in lower metabolism (TCA cycle and anaplerotic reactions), and vice versa [15]. For example, research has demonstrated that the best tracer for upper metabolism in E. coli is 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose, while [4,5,6-13C]glucose and [5-13C]glucose both produce optimal flux resolution in the lower part of metabolism [15]. This understanding has led to the development of COMPLETE-MFA (complementary parallel labeling experiments technique for metabolic flux analysis), which integrates data from multiple tracer experiments to significantly improve flux resolution [15].

Table 2: Commonly Used 13C-Labeled Tracers and Their Applications

| Tracer Type | Cost Range (per gram) | Optimal Application | Pathway Resolution Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1-13C] Glucose | ~$100 | Single tracer experiments | Glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway |

| [1,2-13C] Glucose | ~$600 | High-resolution flux mapping | Glycolytic fluxes, pathway interactions |

| [U-13C] Glucose | ~$1,000 | Comprehensive labeling | Overall network activity, novel pathway discovery |

| Tracer Mixtures | Varies by composition | COMPLETE-MFA studies | Balanced resolution across multiple pathways |

Cell Cultivation Under Metabolic Steady State

A critical requirement for conventional 13C-MFA is achieving metabolic and isotopic steady state, where both the concentration and isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites remain constant [12] [14]. This is typically accomplished using either chemostat cultures or carefully controlled batch cultures during exponential growth phase [12]. Cells are cultivated in strictly minimal medium with the selected 13C-labeled substrate as the sole carbon source to prevent dilution of the isotopic label from unlabeled carbon sources [12].

For steady-state 13C-MFA, the cultivation must continue for a sufficient duration to ensure complete isotopic equilibrium—typically more than five residence times—to guarantee that the system reaches isotopic steady state [14]. In this state, cells continue to grow and consume carbon sources, but the fluxes through metabolic pathways remain constant, providing a reliable basis for subsequent analysis [14]. The implementation of this protocol requires meticulous attention to environmental conditions including temperature, oxygen concentration, and medium composition, all of which must be carefully controlled and monitored throughout the experiment.

Sample Collection and Analytical Techniques

The measurement of 13C-labeling in metabolites represents a crucial step in the 13C-MFA workflow and is typically achieved using mass spectrometry techniques. Two primary approaches are employed:

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): This widely used method requires a derivatization process using agents such as TBDMS or BSTFA to render molecules (e.g., proteinogenic amino acids) volatile enough for GC-MS analysis [12]. GC-MS provides high precision for measuring isotopic enrichment in amino acids and organic acids.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): This technique enables direct analysis of metabolites with trace amounts or high instabilities due to its high sensitivity, eliminating the need for derivatization [12]. LC-MS is particularly valuable for measuring labile or non-volatile metabolites that are not amenable to GC-MS analysis.

Additionally, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy serves as a complementary technique that can provide detailed structural information and atomic position-specific labeling data, though typically with lower sensitivity than mass spectrometry methods [11] [13]. For each analytical method, systematic correction of naturally occurring isotope effects is essential using established algorithms to generate accurate mass distribution vectors (MDVs) for metabolites of interest [12].

Computational Analysis and Flux Estimation

Metabolic Network Modeling and Flux Calculation

The core of 13C-MFA computational analysis involves estimating metabolic flux parameters through nonlinear regression to best fit the experimentally measured isotope labeling patterns and external rate data [14]. This process is computationally demanding due to the complex relationship between isotopic enrichments and fluxes, which is captured in a mathematical model that predicts fractional labeling patterns from given flux values [13]. The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework has emerged as a pivotal innovation that significantly simplifies flux estimation by decomposing complex metabolic networks into basic units for modular analysis [14].

The EMU framework, introduced by Antoniewicz et al., has dramatically reduced the computational burden of 13C-MFA by identifying the minimal set of metabolite fragments needed to simulate isotopic labeling [11] [12]. This framework enables the modeling and solution of metabolic networks to be more operable and repeatable, making comprehensive flux analysis feasible for larger network models [14]. The flux estimation process operates inversely, iteratively adjusting flux values in the model until the differences between predicted and measured labeling patterns are minimized [13].

Software Platforms for 13C-MFA

Several specialized software platforms have been developed to implement the computational algorithms for 13C-MFA:

Table 3: Computational Tools for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Software | Key Features | Algorithm Core | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13CFLUX2 | Steady-state 13C-MFA | EMU | UNIX/Linux |

| Metran | Steady-state 13C-MFA | EMU | MATLAB |

| INCA | Isotopically non-stationary MFA | EMU | MATLAB |

| OpenFLUX2 | Flexible flux estimation | EMU | Various |

| FiatFLUX | User-friendly interface | Not specified | MATLAB |

These tools have democratized the application of 13C-MFA by providing accessible platforms for performing complex flux calculations. The ongoing development of these software packages continues to address computational challenges and expand the scope of tractable metabolic networks [12].

Statistical Validation and Confidence Assessment

Rigorous statistical analysis is essential to ensure the reliability of flux estimates in 13C-MFA. The primary statistical validation involves evaluating the residual sum of squares (SSR), which quantifies the deviation between model predictions and experimental data [14]. The minimized SSR should follow a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom determined by the number of data points and estimated parameters. If the SSR falls outside the expected confidence interval, this may indicate problems such as an incomplete metabolic model, incorrect reaction reversibility settings, measurement errors, or poor-quality isotopic labeling data [14].

Additionally, confidence intervals for flux estimates are typically calculated through sensitivity analysis or Monte Carlo simulation. Sensitivity analysis evaluates how small changes in flux parameters affect the SSR, helping to determine the sensitivity of key fluxes [14]. Monte Carlo simulation generates a distribution of flux solutions through random sampling, enabling statistical calculation of confidence intervals and providing probabilistic reliability assessment of the results [14]. This comprehensive statistical framework ensures that flux estimates are reported with appropriate measures of uncertainty.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 13C-MFA

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in 13C-MFA |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1-13C] Glucose, [U-13C] Glucose, [1,2-13C] Glucose | Serve as isotopic tracers to follow carbon fate through metabolic networks |

| Derivatization Reagents | TBDMS, BSTFA | Render metabolites volatile for GC-MS analysis |

| Culture Media Components | M9 minimal medium salts | Provide strictly defined nutritional environment without unlabeled carbon sources |

| Enzymes | Lyases, isomerases (for analytical procedures) | Assist in sample preparation and metabolite analysis |

| Analytical Standards | 13C-labeled amino acids, organic acids | Enable calibration and quantification in MS and NMR analyses |

| Software Platforms | 13CFLUX2, Metran, INCA | Perform computational flux calculations and statistical analysis |

Pathway Visualization and Data Interpretation

Central Carbon Metabolism Flux Mapping

The primary output of 13C-MFA is a quantitative flux map of central carbon metabolism, which includes glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and anaplerotic reactions. These flux maps reveal the metabolic phenotype of cells under specific conditions, enabling researchers to identify key nodal points where metabolic regulation occurs [12]. For example, 13C-MFA studies have demonstrated that the TCA cycle flux in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with high IgG production is substantially higher than in controls, indicating that TCA cycle activity could be a metabolic phenotype specific to high-producing cells and a potential metabolic engineering target [16].

The flux maps generated through 13C-MFA provide unique insights into metabolic pathway activity that cannot be obtained through other omics technologies. By quantifying the actual flow of carbon through alternative pathways, 13C-MFA can identify futile cycles, parallel pathway usage, and the contribution of various substrates to biomass formation and product synthesis [12] [16]. This information is invaluable for understanding how cells redistribute metabolic resources in response to genetic modifications or environmental perturbations.

Diagram 1: Central Carbon Metabolic Network for 13C-MFA. This diagram illustrates key metabolic reactions and fluxes (v1-v11) in central carbon metabolism that can be quantified using 13C-MFA. Yellow nodes represent metabolic intermediates, while red nodes indicate metabolic outputs. Green arrows show carbon flow toward biomass formation, and the red arrow indicates product synthesis.

Advanced Applications and Specialized Methodologies

As 13C-MFA has matured, several advanced methodologies have extended its applications beyond conventional steady-state flux analysis:

Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA): This approach analyzes isotopic labeling before the system reaches steady state, enabling flux determination in systems where long-term metabolic steady state cannot be maintained, such as mammalian cell cultures or photosynthetic organisms [11] [16].

COMPLETE-MFA: By integrating multiple parallel labeling experiments, this methodology significantly improves flux resolution, with studies demonstrating successful integration of up to 14 parallel labeling experiments in E. coli [15].

Spatial Fluxomics: Recent advances have enabled subcellular compartmentalization of flux measurements, particularly important for eukaryotic cells with compartmentalized metabolism [16].

Integrated Multi-Omics Flux Analysis: Combining 13C-MFA with other omics datasets (transcriptomics, proteomics) provides a more comprehensive understanding of metabolic regulation across different cellular hierarchy levels [16].

Diagram 2: 13C-MFA Workflow. This diagram outlines the sequential steps in a typical 13C-MFA study, from experimental design through results interpretation, highlighting the integrated experimental and computational components.

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis has established itself as an indispensable tool for quantitative analysis of metabolic networks across diverse biological systems. The methodology provides unique insights into cellular metabolism by tracing the fate of individual carbon atoms from substrates to products, enabling researchers to move beyond theoretical pathway maps to actual flux distributions in living cells. The continued development of 13C-MFA—including advanced tracer designs, comprehensive parallel labeling strategies, sophisticated computational algorithms, and integration with other omics technologies—promises to further enhance our understanding of metabolic network operation and regulation. As these methodologies become more accessible and widely adopted, 13C-MFA will continue to drive innovations in metabolic engineering, biomedical research, and bioprocess development by providing unambiguous quantitative information about metabolic fluxes that cannot be obtained through any other analytical approach.

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as a pivotal technique for quantifying the flow of nutrients through metabolic pathways in living cells. By tracing the fate of 13C-labeled substrates, researchers can decode the complex functional phenotype of a cell's metabolic network, which integrates information from the genome, transcriptome, and proteome [17]. This capability is indispensable across diverse fields. In metabolic engineering, it guides the rational rewiring of microbial metabolism for bioproduction. In cancer biology, it reveals how oncogenic mutations and the tumor microenvironment reprogram central metabolism to support rapid proliferation, survival, and resistance to therapy [18] [19]. Furthermore, the ability to map metabolic adaptations in disease states provides a powerful foundation for drug discovery, enabling the identification of novel enzymatic targets and the characterization of metabolic mechanisms of drug action [19] [6]. This article details the key applications of 13C-MFA and provides structured protocols for its implementation.

Application Notes

Metabolic Flux Analysis in Cancer Research

Cancer cells exhibit profound metabolic rewiring, and 13C-MFA is a primary tool for its quantitative characterization. It moves beyond static metabolite measurements to reveal the active flux states that support tumor growth.

- Uncovering Oncogenic Metabolic Reprogramming: 13C-MFA has been instrumental in validating and quantifying classic phenomena like the Warburg effect (aerobic glycolysis) and in discovering more recent paradigms. This includes the reductive metabolism of glutamine for lipogenesis under hypoxia, altered serine/glycine and one-carbon metabolism, and the role of the transketolase-like 1 (TKTL1) pathway [18]. The technique has directly linked oncogenic activation of signaling pathways (e.g., Ras, Akt, Myc) to specific flux changes, such as induced aerobic glycolysis and glutamine catabolism [19].

- Elucidating Metabolic Adaptations to the Tumor Microenvironment: The hypoxic and nutrient-poor core of solid tumors forces distinct metabolic adaptations. 13C-MFA studies comparing 2D monolayer cultures with 3D spheroid models that mimic the tumor microenvironment have revealed that 3D-cultured cancer cells exhibit a distinct metabolic phenotype, including the upregulation of pyruvate carboxylase flux and downregulation of glutaminolytic flux [20]. This has direct implications for drug sensitivity, as these 3D-cultured cells showed lower sensitivity to the glutaminase inhibitor CB-839, highlighting the importance of model selection for accurately predicting drug efficacy [20].

- Identifying Novel Therapeutic Targets: By quantifying flux rewiring in specific genetic contexts, 13C-MFA can reveal induced metabolic dependencies. For example, in breast cancers with PHGDH amplification, 13C-MFA revealed that de novo serine biosynthesis contributes significantly to anaplerotic flux, suggesting the serine synthesis pathway as a therapeutic target [19]. Similarly, IDH1-mutant cells were found to rely on oxidative mitochondrial metabolism, presenting a therapeutic vulnerability [19].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Fluxes Altered in Cancer Cells

| Metabolic Pathway/Feature | Flux Alteration in Cancer | Functional Significance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Glycolysis (Warburg Effect) | ↑ Glycolytic flux, ↑ Lactate secretion | Rapid ATP production, provision of anabolic precursors | [18] |

| Reductive Glutamine Metabolism | ↑ Reductive carboxylation | Lipogenesis under hypoxia or mitochondrial dysfunction | [19] |

| Pyruvate Carboxylase (PC) | ↑ PC flux (in 3D models) | Anaplerosis for TCA cycle, supporting anabolism | [20] |

| Serine/Glycine/One-Carbon Metabolism | ↑ Flux through serine biosynthesis | Production of nucleotides, proteins, and methyl donors | [18] |

| Oxidative Pentose Phosphate Pathway | Altered flux (e.g., via KEAP1 mutation) | NADPH production for redox balance and biosynthesis | [19] |

Metabolic Engineering and Biotechnology

13C-MFA serves as a "gold standard" for quantifying the metabolic flux phenotype of industrial microorganisms, such as E. coli and yeast [14] [15]. It is used to:

- Identify flux bottlenecks in the synthesis pathways of desired products like biofuels, bioplastics, and pharmaceuticals.

- Verify the success of genetic engineering strategies by quantifying changes in carbon flow through engineered pathways.

- Optimize culture conditions to maximize yield and productivity by guiding medium design and feeding strategies. The use of parallel labeling experiments (COMPLETE-MFA) has been established as a powerful approach for achieving very high flux resolution and precision in these systems [15].

Drug Discovery and Development

The application of 13C-MFA in drug discovery is growing rapidly.

- Target Identification: As noted above, 13C-MFA can pinpoint metabolic pathways that are essential in specific disease contexts, thereby nominating them for pharmacological inhibition [19].

- Mechanism of Action Studies: By tracking flux changes in response to drug treatment, researchers can decipher how a compound reshapes cellular metabolism. This is crucial for understanding both efficacy and potential toxicity.

- Biomarker Development: 13C-tracing ex vivo in patient-derived tissues, as demonstrated in human liver studies [21], can potentially be used to stratify patients based on their tumor's metabolic flux profile, guiding therapy selection.

Advancing Model Systems: From 2D to Human Tissue Ex Vivo

A critical application of 13C-MFA is in validating and characterizing experimental models. Research shows that 3D spheroid cultures recapitulate metabolic features of in vivo tumors more accurately than conventional 2D cultures [20]. Furthermore, a groundbreaking advancement is the application of global 13C tracing and MFA to intact human liver tissue cultured ex vivo [21]. This approach preserves the tissue's architecture and core metabolic functions (e.g., albumin and urea production) and has been used to reveal human-specific metabolic activities, such as de novo creatine synthesis, which may differ from rodent models [21]. This ex vivo platform provides an experimentally tractable system for studying human tissue metabolism with high resolution.

Experimental Protocols

A Generic Workflow for 13C-MFA

The following diagram outlines the core steps of a 13C-MFA experiment, from design to validation.

Figure 1: 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow

Protocol: Performing 13C-MFA in Cancer Cell Cultures

Objective: To quantify intracellular metabolic fluxes in cancer cells under a defined condition (e.g., normoxia vs. hypoxia, 2D vs. 3D culture).

I. Experimental Design and Tracer Experiment [18] [14] [1]

- Cell Culture & Model Selection:

- Culture cancer cells (e.g., HCT116, A549) in appropriate medium.

- Choose a model system: 2D monolayer or 3D spheroids (e.g., using ultra-low-attachment plates [20]).

- Tracer Selection:

- Replace the natural-abundance glucose in the medium with a 13C-labeled form. A common and recommended tracer is [1,2-13C]glucose, which provides good flux resolution for central carbon metabolism [14] [15].

- For higher flux precision, consider using a mixture of tracers (e.g., 75% [1-13C]glucose + 25% [U-13C]glucose) or designing parallel labeling experiments with complementary tracers [15].

- Performing the Experiment:

- Seed cells and allow them to attach and resume growth.

- Replace the medium with the tracer-containing medium.

- Culture cells until isotopic steady state is reached, typically after 5 residence times or more [14]. For mammalian cells, this often requires 24-72 hours of labeling.

- Sample Collection: Collect samples at multiple time points for:

- Cell number and viability (to calculate growth rate, μ).

- Medium metabolites (to calculate nutrient uptake and byproduct secretion rates).

- Intracellular metabolites (for isotopic labeling analysis).

II. Data Collection and Analysis [18] [14] [1]

- Calculate External Fluxes:

- Growth rate (μ) is calculated from the exponential increase in cell number over time [18].

- Nutrient uptake and product secretion rates (ri) are determined from changes in metabolite concentrations in the medium, normalized to cell number and time [18]. For proliferating cells, use the formula:

ri = 1000 * μ * V * ΔCi / ΔNx(ri in nmol/10^6 cells/h, ΔCi in mmol/L, ΔNx in millions of cells, V in mL).

- Measure Isotopic Labeling:

- Extract polar metabolites (e.g., using cold methanol-water extraction).

- Analyze metabolites using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS) to obtain Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) [20] [14]. The MIDs represent the fractional abundance of molecules with different numbers of 13C atoms.

III. Computational Flux Analysis [18] [6] [17]

- Define Metabolic Network Model:

- Construct a stoichiometric model of central metabolism (glycolysis, PPP, TCA cycle, etc.) including atom transitions for each reaction.

- Flux Estimation:

- Statistical Validation:

Protocol: Data Processing and Flux Estimation Workflow

The computational phase of 13C-MFA involves a rigorous process of model simulation and statistical evaluation to extract meaningful flux values, as detailed below.

Figure 2: 13C-MFA Data Analysis Workflow

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for 13C-MFA

| Category | Item | Specification / Example | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-Labeled Glucose | [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose | The core substrate for tracing carbon fate through metabolic networks. |

| 13C-Labeled Glutamine | [U-13C]glutamine | To probe glutaminolysis and TCA cycle anaplerosis. | |

| Cell Culture | Defined Medium | Glucose- and glutamine-free DMEM | Allows precise control over nutrient and tracer composition. |

| 3D Culture Plates | Ultra-low-attachment (ULA) plates | Enables formation of tumor spheroids to mimic the in vivo TME [20]. | |

| Analytical Instruments | Mass Spectrometer | GC-MS or LC-MS system | Quantifies mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) in metabolites. |

| Software & Computational | 13C-MFA Software | INCA, Metran, Iso2Flux | Performs flux estimation, simulation, and statistical analysis [18] [6]. |

| Metabolic Network Model | Custom stoichiometric model | The computational representation of the metabolic system under study. |

Metabolic fluxes, the rates at which metabolites are transformed within a cellular metabolic network, are pivotal for understanding cellular physiology in health and disease. Unlike metabolites or proteins, fluxes cannot be measured directly and must be inferred through computational methods that integrate experimental data and mathematical models [19] [22]. For cancer biologists and metabolic engineers, quantifying these fluxes is essential for uncovering how cells rewire their metabolism to support rapid proliferation, adapt to microenvironments, or produce valuable biochemicals [3] [12]. Three powerful techniques for flux inference are 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), and Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP). Each method operates on different principles, requires distinct experimental inputs, and is suited to particular research scenarios. This article provides a detailed comparison of these methods, offering application notes and protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate fluxomics approach for their research objectives.

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics, requirements, and applications of the three fluxomics methods.

Table 1: High-Level Comparison of 13C-MFA, FBA, and KFP

| Feature | 13C-MFA | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Fitting a model to isotopic labeling patterns to infer fluxes [22] | Stoichiometric modeling constrained by an assumed cellular objective (e.g., growth maximization) [19] [22] | Analyzing the kinetics of isotope incorporation into metabolites [23] [19] |

| Primary Data Input | Mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) from MS/NMR; extracellular rates [3] [1] | Genome-scale metabolic model; exchange fluxes (optional) [19] | Time-series MIDs (specifically M+0 fraction); pool sizes [23] |

| Key Assumptions | Metabolic & isotopic steady state [22] | Steady-state mass balance; defined cellular objective function [22] | Isotopically non-stationary state; simplified sub-network [23] |

| Primary Output | Quantitative map of intracellular fluxes in central metabolism [3] | Genome-scale flux distribution [19] | Flux through a specific metabolite or sub-network [23] |

| Scope of Fluxes | Central metabolism (dozens of reactions) [12] | Genome-scale (hundreds to thousands of reactions) [19] | Local, specific reactions or sub-networks [23] |

| Computational Demand | High (non-linear optimization) [19] | Low to Medium (Linear Programming) | Medium (analytical or ODE solutions) [23] |

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting the most appropriate fluxomics method based on research goals and experimental constraints.

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

Workflow and Protocol

13C-MFA is considered the "gold standard" for quantitatively characterizing metabolic phenotypes in both microbial and mammalian cells [3] [12]. The core protocol involves several standardized steps.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for 13C-MFA

| Category | Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Tracers | [1,2-¹³C] Glucose, [U-¹³C] Glutamine | Labeled substrates to trace carbon fate through metabolic pathways [3]. |

| Software | INCA, Metran, 13CFLUX2 | User-friendly tools implementing the EMU framework for efficient flux estimation [3] [19] [12]. |

| Analytical | GC-MS or LC-MS | Measures mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of intracellular metabolites or proteinogenic amino acids [3] [12]. |

Step 1: Experimental Design and Cell Cultivation.

- Tracer Selection: Choose an appropriate ¹³C-labeled substrate. For central carbon metabolism, a mixture of 80% [1-¹³C] and 20% [U-¹³C] glucose is often used to ensure high ¹³C abundance in various metabolites [12]. The tracer must be the sole carbon source in a strictly minimal medium.

- Culture Mode: Cultivate cells in chemostat mode (to achieve both metabolic and isotopic steady state) or in batch mode with careful sampling at metabolic steady state [12]. Ensure that metabolite concentrations and isotopic labeling are constant at the time of sampling.

Step 2: Data Collection.

- Extracellular Fluxes: Quantify nutrient uptake (e.g., glucose, glutamine) and product secretion rates (e.g., lactate, ammonium). For exponentially growing cells, calculate rates (ri) using the formula:

r_i = 1000 * (μ * V * ΔC_i) / ΔN_xwhere μ is the growth rate, V is culture volume, ΔCi is metabolite concentration change, and ΔNx is the change in cell number [3]. - Isotopic Labeling: Quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites. Derivatize samples (for GC-MS) and measure Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) using GC-MS or LC-MS. Correct raw data for natural isotope abundances [3] [1] [12].

Step 3: Model Construction and Flux Estimation.

- Network Definition: Construct a stoichiometric model of central metabolism, including atom transition mappings for each reaction [19] [13].

- Flux Estimation: Use software like INCA or Metran to perform a least-squares regression. The algorithm varies flux values to minimize the difference between simulated and measured MIDs, subject to stoichiometric constraints [3] [19]. This is a non-convex optimization problem, often solved using heuristic algorithms like Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) [19].

Step 4: Statistical Validation.

- Perform a goodness-of-fit analysis (e.g., χ²-test) to evaluate model agreement with data [1].

- Calculate confidence intervals for each estimated flux, for example, using parameter continuation methods, to assess the uncertainty of the flux solution [1] [19].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

Workflow and Protocol

FBA predicts flow through a genome-scale metabolic network based on stoichiometry, mass-balance, and an assumed biological objective [19] [22].

Step 1: Network Reconstruction.

- Obtain or reconstruct a genome-scale metabolic network for the target organism. This network should include all known metabolic reactions and their gene-protein-reaction associations [19].

Step 2: Define Constraints and Objective.

- Apply mass-balance constraints:

S ∙ v = 0, whereSis the stoichiometric matrix andvis the flux vector [22]. - Set constraints on exchange fluxes based on measured nutrient uptake rates, if available [19].

- Define a cellular objective function, Z, to be maximized. The most common objective is the biomass reaction, which is formulated to reflect the organism's macromolecular composition [19] [22].

Step 3: Solve the Linear Programming Problem.

- Solve the problem:

Maximize Z = c^T v, subject toS ∙ v = 0andlb ≤ v ≤ ub. - Use COBRA Toolbox or similar software to compute the flux distribution that maximizes the objective function under the given constraints [19].

Kinetic Flux Profiling (KFP)

Workflow and Protocol

KFP is a local approach for isotopically nonstationary MFA (INST-MFA) used to estimate fluxes in a specific sub-network using kinetic labeling data [23].

Step 1: Experimental Setup.

- Introduce a ¹³C tracer to cells at metabolic steady state.

- Rapidly collect time-series samples (over seconds to minutes) to track the incorporation of the label into metabolites of interest [23] [19].

Step 2: Data Requirements.

- Measure the fraction of unlabeled mass isotopomer (M+0) over time for metabolites in the sub-network [23].

- Determine the absolute concentrations of the same metabolites, as these are required to set up the system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) [23] [19].

Step 3: Flux Calculation.

- For simple network motifs (e.g., a product metabolite made from a single labeled substrate), the system of ODEs describing the labeling kinetics can be solved analytically to yield the flux [23].

- The flux through a metabolite is determined by fitting the analytical solution to the measured decay curve of the M+0 fraction [23].

Advanced Applications and Method Selection

Applications in Cancer Research and Metabolic Engineering

- 13C-MFA in Cancer Biology: 13C-MFA has been instrumental in uncovering metabolic rewiring driven by oncogenes. It has revealed that oncogenic activation of Ras, Akt, and Myc induces aerobic glycolysis, glutamine consumption, and TCA cycle flux alterations [19]. Furthermore, it has been used to identify targets like the serine synthesis pathway in PHGDH-amplified breast cancers [19].

- FBA in Systems Biology: FBA is particularly powerful for integrating multi-omics data. Transcriptomic or proteomic data can be used to create context-specific metabolic models for different cancer cell lines or patient tumors, enabling large-scale predictions of flux vulnerabilities [19].

- KFP for Targeted Analysis: KFP is ideal for resolving rapid metabolic dynamics in specific pathways, such as nitrogen metabolism in plants or central carbon metabolism in bacteria, without the need for a full-network model or isotopic steady state [23].

Guidelines for Method Selection

- Use 13C-MFA when: Your research question requires highly accurate, quantitative flux maps of central metabolism, especially for resolving fluxes in parallel pathways, cycles, or reversible reactions [1] [22]. This is the preferred method for validating metabolic engineering interventions or characterizing fundamental cell physiology [12].

- Use FBA when: You need genome-scale flux predictions or are working with large sets of omics data. FBA is ideal for generating hypotheses, exploring genetic deletion phenotypes, or modeling systems where isotope tracing is impractical [19]. Its reliance on an assumed objective function is a key limitation [22].

- Use KFP when: You are interested in the flux through a specific, well-defined sub-network and can obtain high-time-resolution isotopic labeling data. KFP is a powerful local approach that avoids the computational complexity of global INST-MFA [23]. It is particularly useful when the system cannot reach isotopic steady state.

13C-MFA, FBA, and KFP are complementary tools in the fluxomics arsenal. 13C-MFA is the benchmark for quantitative flux estimation in core metabolism. FBA provides a genome-scale perspective based on stoichiometry and optimization. KFP offers a targeted approach for dynamic flux analysis in specific pathways. The choice of method should be driven by the biological question, the scale of the network under investigation, and the type of experimental data that can be acquired. By following the outlined protocols and guidelines, researchers can effectively apply these powerful techniques to illuminate the functional state of metabolic networks.

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) is a powerful model-based technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells, providing a quantitative map of cellular metabolism that has become indispensable in metabolic engineering, systems biology, and biomedical research [3] [1]. At the heart of 13C-MFA lie three fundamental concepts: Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs), which are the primary experimental measurements; Metabolic Steady-State, which is a key assumption for many flux analysis methods; and Network Topology, which defines the possible metabolic transformations [2] [3]. The accurate determination of metabolic fluxes depends on the precise interplay of these three elements, forming the foundation for understanding how cells utilize nutrients for energy production, biosynthesis, and redox homeostasis [3]. This protocol outlines the essential concepts and practical methodologies for researchers implementing 13C-MFA studies, with a focus on producing reliable, reproducible flux measurements.

Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs)

Theoretical Basis and Definition

Mass Isotopomer Distribution Analysis (MIDA) is a technique for measuring the synthesis of biological polymers based on quantifying the relative abundances of molecular species of a polymer differing only in mass (mass isotopomers) after introducing a stable isotope-labeled precursor [24]. Mass isotopomers are variants of metabolites that differ only in their number of heavy isotopes (e.g., 13C) and are identified by mass spectrometry according to their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [24] [25]. The mass isotopomer pattern or distribution is analyzed according to a combinatorial probability model by comparing measured abundances to theoretical distributions predicted from the binomial or multinomial expansion [24]. For combinatorial probabilities to be applicable, a labeled precursor must combine with itself in the form of two or more repeating subunits, allowing both dilution in the monomeric (precursor) and polymeric (product) pools to be determined [24].

The MID represents the fractional abundance of each mass isotopomer for a given metabolite, typically denoted as M+0, M+1, M+2, etc., where the number indicates how many 13C atoms the molecule contains [24] [3]. For example, M+0 represents molecules containing only 12C atoms, while M+1 contains one 13C atom, and so forth. The sum of all fractional abundances in a MID always equals 1 [24]. Different metabolic pathways produce characteristically different labeling patterns in metabolites, enabling the discrimination of alternative metabolic routes that converge on the same metabolite [2] [26].

Measurement and Analytical Considerations

Mass isotopomer distributions are typically measured using mass spectrometry techniques, with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) being the most commonly employed method in 13C-MFA studies [25] [1]. Other analytical platforms include liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), tandem MS (MS/MS), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, each with distinct advantages and limitations [25]. MS-based platforms provide high sensitivity and can detect low-abundance metabolites, while NMR offers structural information but with lower sensitivity [25].

Critical considerations for accurate MID measurement include:

- Natural Isotope Correction: Raw mass spectrometry data must be corrected for the natural abundance of stable isotopes (13C, 2H, 17O, 18O, 15N, 29Si, 30Si, 33S, 34S) to isolate the labeling resulting from the tracer experiment [24] [25].

- Instrumental Accuracy: Quantitative inaccuracy of instruments represents a major practical challenge, requiring careful calibration and validation of instrument performance [24].

- Concentration Effects: Attention to concentration effects on mass isotopomer ratios is essential, with recommendations to maximize enrichments in the isotopomers of interest to reduce error [24].

- Data Reporting: According to Metabolomics Standards Initiative guidelines, researchers should define identification levels, common names, and structure codes when reporting metabolite annotations [25].

Table 1: Mass Spectrometry Platforms for MID Measurement

| Platform | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Analysis of amino acids, organic acids, sugars, fatty acids | High sensitivity, quantitative robustness, established protocols | Requires volatile compounds or chemical derivatization |

| LC-MS | Analysis of lipids, nucleotides, complex metabolites | Broad metabolite coverage, minimal sample preparation | Less quantitative, matrix effects more pronounced |

| NMR | Structural determination, positional labeling | Non-destructive, provides positional labeling information | Lower sensitivity, requires larger sample amounts |

| GC-MS/MS | Complex mixtures, isotopomer differentiation | Enhanced specificity, reduced chemical noise | More complex operation, higher cost |

Metabolic Steady-State

Concept Definition and Importance

Metabolic steady-state, specifically metabolic and isotopic steady-state, is a fundamental prerequisite for steady-state 13C-MFA [26]. This state occurs when metabolic fluxes, metabolite pool sizes, and isotopic labeling patterns remain constant over time, despite continuous cell growth and metabolic activity [2] [26]. Under these conditions, the net change in concentration for each intracellular metabolite is zero, allowing the application of mass balance equations to calculate metabolic fluxes [26]. The isotopic steady-state is achieved when the labeling patterns of all metabolic intermediates no longer change with time, which requires that the cells be cultured for a sufficient duration in the presence of the isotopic tracer [26].

The metabolic steady-state assumption significantly simplifies the computational complexity of flux estimation by reducing the system from differential equations to algebraic equations [2] [26]. This forms the basis for traditional 13C-MFA, where the isotopic labeling distribution is measured after the system has reached isotopic stationarity [2]. For proliferating cells, exponential growth at a constant rate is often used as a proxy for metabolic steady-state, as constant growth rates typically reflect stable metabolic states [3].

Achieving and Validating Metabolic Steady-State

To ensure metabolic and isotopic steady-state in tracer experiments, several experimental design considerations must be implemented:

- Culture Duration: Cells must be cultured for a sufficient number of generations (typically >5 residence times) on the labeled substrate to ensure complete isotopic equilibration [26] [14]. For mammalian cells, this typically requires 24-72 hours of culture in labeled medium.

- Constant Growth Conditions: Maintenance of constant temperature, pH, oxygen tension, and nutrient availability throughout the labeling experiment is essential to prevent metabolic adaptations [3].

- Exponential Growth Phase: Cells should be maintained in exponential growth phase throughout the labeling period, with careful monitoring of growth kinetics [3].

- Minimizing Environmental Perturbations: Any disturbance to the culture system (e.g., medium changes, passaging) should be minimized during the labeling period.

Validation of steady-state conditions involves:

- Growth Rate Consistency: The specific growth rate (µ) should remain constant during the labeling period, calculated from cell counting data using the equation: Nx = Nx,0 · exp(µ · t), where Nx is cell number at time t [3].

- Metabolite Concentration Stability: Extracellular metabolite concentrations (glucose, lactate, amino acids) should change linearly with time during the labeling period [3].

- Labeling Pattern Stability: For true isotopic steady-state, the MID of key metabolites should remain constant between sequential sampling time points [26].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Metabolic Steady-State Validation

| Parameter | Measurement Method | Validation Criteria | Typical Values for Mammalian Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Growth Rate (µ) | Cell counting, biomass measurement | Constant over time (CV < 10%) | 0.4-0.8 day-1 (doubling time: 20-40 hours) |

| Glucose Uptake Rate | Medium concentration analysis | Linear decrease over time | 100-400 nmol/106 cells/h |

| Lactate Secretion Rate | Medium concentration analysis | Linear increase over time | 200-700 nmol/106 cells/h |

| MID Stability | GC-MS of proteinogenic amino acids | No significant change between time points | Coefficient of variation < 5% for major mass isotopomers |

Network Topology

Fundamental Principles

Network topology in 13C-MFA refers to the comprehensive definition of the metabolic network structure, including all biochemical reactions, metabolite pools, atom transitions, and stoichiometric relationships [27] [1]. The topology defines the possible pathways through which carbon atoms from labeled substrates can flow, creating the specific labeling patterns measured in MIDs [27]. A well-defined network topology includes: the complete set of metabolic reactions with proper stoichiometry; atom mapping information describing how carbon atoms are rearranged in each reaction; subcellular compartmentation (for eukaryotic cells); and definition of biomass composition and biosynthetic requirements [26] [1].

The topology of isotope labeling networks (ILNs) contains all essential information required to describe the flow of labeled material in isotope labeling experiments [27]. Analysis of ILN topology has revealed that these networks consistently break up into a large number of small strongly connected components (SCCs) with natural isomorphisms between many SCCs, a topological feature that can be exploited to significantly speed up computational algorithms for flux estimation [27].

Network Construction and Refinement

Constructing an accurate metabolic network model requires:

- Reaction Stoichiometry: Precise definition of all metabolic reactions with correct stoichiometric coefficients, including cofactors and energy metabolites [1].

- Atom Transitions: Mapping of carbon atom fate through each biochemical reaction, which is essential for simulating isotopic labeling patterns [28] [1].

- Compartments: For eukaryotic cells, proper assignment of reactions to subcellular compartments (cytosol, mitochondria, etc.) [26].

- Biomass Equation: Definition of biomass composition based on experimental measurements of macromolecular content [26].

- Network Reduction: Judicious lumping of metabolic steps or elimination of metabolites with minimal impact on flux determination to reduce computational complexity [26].

The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework has emerged as a powerful approach for modeling isotope labeling in complex metabolic networks by decomposing metabolites into smaller subunits that represent the minimal information needed to simulate the measured labeling patterns [2] [28]. This framework significantly reduces computational complexity while maintaining accuracy in flux estimation [2].

Network Topology Construction Workflow

Integrated 13C-MFA Experimental Protocol

Comprehensive Workflow

The integration of MIDs, metabolic steady-state, and network topology occurs within the complete 13C-MFA workflow, which consists of five fundamental steps [3] [14]:

- Experimental Design: Selection of appropriate isotopic tracers and labeling strategy based on the specific metabolic questions and network topology [29].

- Tracer Experiment: Culturing cells under metabolic steady-state conditions with the selected 13C-labeled substrates [3].

- Isotopic Labeling Measurement: Sampling and analysis of MIDs using appropriate analytical platforms [25].

- Flux Estimation: Computational integration of MID data, external fluxes, and network topology to calculate intracellular fluxes [2] [3].

- Statistical Analysis: Validation of flux estimates through goodness-of-fit tests and confidence interval analysis [1] [14].

13C-MFA Workflow

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

The selection of appropriate 13C-labeled tracers is critical for achieving sufficient flux resolution. Different tracers provide varying levels of information about specific metabolic pathways [29]:

- [1,2-13C]glucose: Excellent for resolving phosphoglucoisomerase flux and TCA cycle fluxes [29].

- [U-13C]glucose: Provides comprehensive labeling information but at higher cost [29].

- [1-13C]glucose: Traditional, cost-effective option but with lower flux resolution for some pathways [29].

Optimal experimental design should consider both information content and experimental costs, with multi-objective optimization approaches available to identify cost-effective tracer mixtures [29]. For parallel labeling experiments, mixtures of differently labeled substrates can significantly enhance flux resolution while controlling costs [29].

Table 3: Tracer Selection Guide for 13C-MFA

| Tracer | Cost Relative to [1-13C]glucose | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1-13C]glucose | 1x (∼$100/g) | General flux analysis, glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway | Cost-effective, widely available | Limited resolution for TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis |

| [U-13C]glucose | 3x | Comprehensive network analysis, complex pathway interactions | Maximum information content | High cost, potential metabolic side effects |

| [1,2-13C]glucose | 6x (∼$600/g) | TCA cycle, gluconeogenesis, glyoxylate shunt | Superior flux resolution for key pathways | Highest cost, limited availability |

| Mixed Tracers | Variable | Targeted pathway resolution, cost-effective designs | Balanced approach, customizable | Increased experimental complexity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for 13C-MFA

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose, 13C-glutamine | Creation of specific isotopic labeling patterns for pathway tracing | Purity > 99%, isotopic enrichment verification required |

| Cell Culture Media | Defined minimal media, dialyzed serum, isotope-free supplements | Maintain metabolic steady-state, eliminate unlabeled carbon sources | Consistent composition, minimal lot-to-lot variation |

| Analytical Standards | Unlabeled metabolite standards, derivatization reagents | Metabolite identification and quantification in MS analysis | High purity, MS-grade compatibility |

| Sample Preparation | Methanol, chloroform, water (MS-grade), solid phase extraction columns | Metabolite extraction and purification | High purity, minimal background contamination |

| Derivatization Reagents | MSTFA, MBTSTFA, methoxyamine hydrochloride | Volatilization of metabolites for GC-MS analysis | Fresh preparation, anhydrous conditions |

| Software Tools | INCA, Metran, 13CFLUX2, OpenMebius | Flux estimation, statistical analysis, data interpretation | Model compatibility, computational requirements |

Computational Flux Estimation and Statistical Validation

Flux Estimation Methodology

The core computational process of 13C-MFA involves estimating intracellular fluxes by minimizing the difference between measured and simulated MIDs [2] [28]. This is formalized as a least-squares parameter estimation problem:

arg min Σ(x - xM)²

where x represents the simulated labeling data and xM represents the measured labeling data [2]. The estimation is subject to stoichiometric constraints (S · v = 0) and must account for the network topology and atom transitions [2].

The flux estimation process involves:

- Model Compilation: Translating the metabolic network topology with atom mappings into the EMU framework [2] [28].

- Labeling Simulation: Calculating the expected MIDs for the current flux values [2].

- Parameter Optimization: Iteratively adjusting flux values to minimize the residual sum of squares between measured and simulated MIDs [28].

- Convergence Testing: Ensuring the optimization algorithm has reached a global minimum [1].

Statistical Validation and Goodness-of-Fit

Comprehensive statistical validation is essential for establishing confidence in flux estimates [1] [14]:

- Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) Evaluation: The minimized RSS should follow a χ² distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of data points minus the number of estimated parameters [14]. The model fit is considered acceptable if the RSS falls within the expected confidence interval (e.g., χ²α/2(n-p) ≤ RSS ≤ χ²1-α/2(n-p) for α=0.05) [14].

- Parameter Identifiability Analysis: Assessment of whether the available measurement data provides sufficient information to uniquely determine all estimated fluxes [1].

- Confidence Interval Calculation: Determination of flux confidence intervals using methods such as Monte Carlo simulation or sensitivity analysis [1] [14].

- Model Validation: Testing whether the metabolic network model adequately represents the experimental system, potentially requiring model refinement if the fit is statistically unacceptable [1].

Successful implementation of these validation procedures ensures that the integrated analysis of MIDs, metabolic steady-state, and network topology yields biologically meaningful and statistically robust flux measurements for understanding cellular metabolism in health and disease.

Executing a High-Resolution 13C-MFA Protocol: From Cell Culture to Data Collection

The choice of isotopic tracer is a critical first step in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) as it fundamentally determines the precision with which intracellular metabolic fluxes can be determined [30]. The labeling pattern of the substrate influences which isotopomers of intracellular metabolites can be formed and governs the sensitivity of mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) to changes in metabolic fluxes [31]. Rational tracer selection moves beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches by using model-based design principles to maximize information content for flux determination [31] [32]. For research organisms and producer strains where prior knowledge about fluxes may be limited, robust experimental design strategies are particularly valuable [32].

Optimal Tracer Recommendations by Metabolic Pathway

Extensive in silico and experimental evaluations have identified optimal tracers for probing specific metabolic pathways in central carbon metabolism. The tables below summarize tracer recommendations based on comprehensive performance assessments.

Table 1: Performance of Single Glucose Tracers for 13C-MFA in E. coli (Precision Scores Relative to Reference Tracer)

| Tracer | Precision Score | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C]Glucose | 7.2 | High precision for glycolysis, PPP, and overall network [30] [33] |

| [1,6-13C]Glucose | 7.4 | One of the best overall single tracers; high flux precision [33] |

| [5,6-13C]Glucose | 6.9 | Excellent performance for upper glycolysis and PPP [33] |

| 80% [1-13C]Glucose + 20% [U-13C]Glucose | 1.0 (Reference) | Widely used low-cost mixture; baseline for comparison [33] |

| [U-13C]Glucose | 3.1 | Good overall coverage but less precise than double labels [33] |

Table 2: Pathway-Specific Tracer Recommendations for Mammalian Cell Systems

| Metabolic Pathway | Recommended Tracer(s) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis & PPP | [1,2-13C]Glucose [30] | Provides superior flux precision for glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway [30] |

| TCA Cycle | [U-13C]Glutamine [30] | Preferred for analysis of TCA cycle fluxes [30] |

| Overall Network | [1,2-13C]Glucose [30] | Highest precision estimates for central carbon metabolism as a whole [30] |

| Parallel Labeling | [1,6-13C]Glucose + [1,2-13C]Glucose [33] | Combined analysis improves flux precision nearly 20-fold versus reference tracer [33] |

Methodologies for Rational Tracer Design

EMU Basis Vector Analysis

The Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework provides a fundamental methodology for rational tracer design [31]. This approach decomposes metabolic network models into basis vectors that represent the fundamental building blocks of isotopic labeling. The core principle involves expressing any metabolite in the network as a linear combination of EMU basis vectors, where coefficients indicate the fractional contribution of each basis vector to the product metabolite [31]. This framework decouples substrate labeling (EMU basis vectors) from the dependence on free fluxes (coefficients), allowing systematic evaluation of how different tracers impact flux observability [31].

Precision and Synergy Scoring

A quantitative scoring system has been developed to evaluate tracer performance for 13C-MFA:

Precision Score (P): Calculated as the average of individual flux precision scores (pi) for n fluxes of interest: ( P = \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n} pi ) with ( pi = \left( \frac{(UB{95,i} - LB{95,i}){ref}}{(UB{95,i} - LB{95,i}){exp}} \right)^2 ) where UB{95,i} and LB{95,i} represent the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals for flux i [33]. This score quantifies the fold-improvement in flux precision relative to a reference tracer experiment.

Synergy Score (S): For parallel labeling experiments, the synergy score quantifies the additional information gained by combining multiple tracers: ( S = \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n} \frac{p{i,1+2}}{p{i,1} + p{i,2}} ) where p{i,1+2} is the precision score for the parallel experiment, and p{i,1}, p_{i,2} are scores for individual tracers [33]. A synergy score >1.0 indicates complementary information content.

Robust Experimental Design (R-ED) for Uncertain Flux States

When prior knowledge about fluxes is limited (e.g., for novel organisms or conditions), Robust Experimental Design (R-ED) provides a sampling-based approach to identify tracers that perform well across a wide range of possible flux states [32]. This method characterizes the extent to which tracer mixtures are informative across all possible flux values, avoiding the chicken-and-egg problem of needing flux knowledge to design optimal tracer experiments [32].

Experimental Protocol for Tracer Selection

In Silico Tracer Evaluation

Purpose: To computationally identify optimal isotopic tracers before conducting wet-lab experiments.

Materials:

- Metabolic network model with atom transitions

- Software for 13C-MFA (e.g., Metran, 13CFLUX2)

- List of commercially available isotopic tracers

Procedure:

- Define Metabolic Network: Formulate a comprehensive metabolic network model including atom transition information for all reactions [1].

- Select Candidate Tracers: Compile a list of physiologically relevant and commercially available 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose, glutamine tracers) [30] [33].

- Assume Reference Flux Map: Use literature values or preliminary data to establish a reference flux map for evaluation [30] [32].

- Simulate Labeling Patterns: For each candidate tracer, simulate the expected mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) for key intracellular metabolites [31] [2].

- Calculate Precision Scores: Compute flux confidence intervals and precision scores for each tracer using statistical methods [33].

- Evaluate Synergy: For parallel labeling designs, identify tracer combinations with high synergy scores [33].

- Select Optimal Tracer(s): Choose the tracer(s) that maximize precision for fluxes of interest while considering practical constraints [32].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Cost-Benefit Analysis:

- Pure glucose tracers generally outperform tracer mixtures and are commercially available [33].

- Consider economic factors: [1,2-13C]glucose provides excellent performance at moderate cost [33].

- For parallel labeling experiments, balance the enhanced precision against increased experimental complexity [34].

Experimental Validation:

- For mammalian cells utilizing multiple substrates, combine [1,2-13C]glucose with [U-13C]glutamine to cover both glycolytic and TCA cycle fluxes [30].

- Use the EMU basis vector method to verify that selected tracers generate sufficient independent measurement information for the number of free fluxes in your model [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 13C-Tracer Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Glucose Tracers | [1,2-13C]Glucose, [1,6-13C]Glucose, [5,6-13C]Glucose [33] | Probing glycolysis, PPP, and overall central carbon metabolism [30] [33] |

| 13C-Labeled Glutamine Tracers | [U-13C]Glutamine [30] | Analysis of TCA cycle and glutaminolysis pathways [30] |

| Culture Medium | Glucose-free DMEM, M9 minimal medium [30] [33] | Defined medium for precise control of labeled substrate availability |

| Software for 13C-MFA | Metran, 13CFLUX2, INCA, Isodyn [35] [2] [10] | Simulation of labeling patterns, flux estimation, and statistical analysis |

| Analytical Instrumentation | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR [30] [2] | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions in intracellular metabolites |

Rational selection of 13C-tracers using the methodologies outlined in this protocol significantly enhances the information content and precision of 13C-MFA studies. The EMU basis vector framework provides fundamental principles for evaluating flux observability, while precision and synergy scoring systems enable quantitative comparison of tracer performance [31] [33]. For researchers working with poorly characterized systems, robust experimental design approaches offer a strategy to overcome the limitation of unknown flux states [32]. Implementation of these optimal tracer selection strategies forms the critical foundation for successful and informative 13C-MFA experiments in both microbial and mammalian systems.

This protocol details the procedure for culturing cells with 13C-labeled substrates and ensuring the achievement of a metabolic steady state, a critical step in 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). The reliability of subsequent flux estimations is entirely contingent upon the precise execution of this phase [3] [17]. The core principle is to maintain cells in a physiological state where metabolic reaction rates (fluxes), metabolite concentrations, and—for the preferred stationary state 13C-MFA—the isotopic labeling of intracellular metabolites remain constant over time [2] [11]. This document provides a detailed, application-oriented guide for researchers.

The procedure for establishing a metabolic steady-state culture with labeled substrates encompasses several key stages, from initial planning to sample collection. The logical sequence and data flow of these stages are illustrated in the following diagram.

Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of this protocol depends on a set of key reagents and materials. The following table catalogues these essential components and their specific functions within the experiment.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Rationale in 13C-MFA |

|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrate (e.g., [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine) | Serves as the isotopic tracer. The specific labeling pattern is chosen to elucidate fluxes in particular pathways of interest [14] [36]. |

| Unlabeled Cell Culture Medium | Provides all necessary nutrients, vitamins, and growth factors. The unlabeled carbon sources are replaced by or supplemented with the labeled tracer. |

| Cell Line of Interest | The biological system under investigation. Cells must be healthy and capable of sustained proliferation or maintenance in culture [3]. |

| Bioreactor or Controlled Culture Vessel | Provides a stable environment (temperature, CO2, humidity) and allows for monitoring and control of parameters like pH and dissolved oxygen, which is crucial for steady-state maintenance [14]. |

| Trypan Blue or Alternative Viability Stain | Used with a hemocytometer or automated cell counter to determine cell concentration and viability, which is essential for calculating growth rates and external fluxes [3]. |