Accelerating Bioprocesses: The DBTL Cycle in Modern Metabolic Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a foundational framework in metabolic engineering for developing microbial cell factories.

Accelerating Bioprocesses: The DBTL Cycle in Modern Metabolic Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle, a foundational framework in metabolic engineering for developing microbial cell factories. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the cycle's core principles, from its application in optimizing pathways for compounds like dopamine and fine chemicals to advanced integration with machine learning and automation. The scope covers practical methodologies, common troubleshooting strategies, and comparative analyses of emerging paradigms, offering a holistic guide for implementing efficient, iterative strain engineering to advance sustainable biomanufacturing and therapeutic development.

The DBTL Framework: Core Principles and Evolutionary Impact in Metabolic Engineering

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is a systematic, iterative framework that has become a cornerstone of modern metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. It provides a structured approach to optimizing microbial cell factories for the production of valuable compounds, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods. By cycling through these four phases, researchers can progressively refine genetic designs, incorporate knowledge from previous iterations, and accelerate the development of economically viable bioprocesses [1] [2]. This guide details the core principles and technical execution of each phase within the context of metabolic engineering research.

The Design Phase

The Design phase involves the strategic planning of genetic modifications to achieve a specific metabolic engineering objective, such as increasing the yield of a target molecule.

Core Objectives and Methodologies

The primary goal is to define which genetic parts to use and how to assemble them to optimize metabolic flux. This includes selecting pathways, enzymes, and regulatory elements.

- Pathway Identification and Selection: Researchers use computational tools to identify biosynthetic gene clusters or perform retrosynthesis to find potential metabolic pathways for the product of interest [2].

- Component Selection: This involves choosing specific enzymes (e.g., codon-optimized coding sequences), promoters, ribosomal binding sites (RBS), and terminators. Libraries of characterized parts are often used to create combinatorial diversity [1] [2].

- Host Strain Engineering: Genome-scale models can identify beneficial host modifications, such as knocking out competing pathways or derepressing feedback inhibition to increase precursor supply [2] [3].

Experimental Protocol: Informing Design with In Vitro Testing

A "knowledge-driven" DBTL cycle uses upstream in vitro experiments to guide the initial design, saving resources.

- Objective: Pre-validate the functionality of a metabolic pathway and assess different enzyme expression levels before committing to in vivo strain construction [3].

- Method:

- Clone the genes of the target pathway (e.g.,

hpaBCandddcfor dopamine production) into plasmids suitable for cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS). - Express the pathway enzymes in a crude cell lysate system derived from a suitable production host (e.g., E. coli).

- Supplement the reaction buffer with necessary precursors (e.g., L-tyrosine) and cofactors.

- Measure the production of the target metabolite (e.g., L-DOPA or dopamine) to determine the most effective enzyme ratios [3].

- Clone the genes of the target pathway (e.g.,

- Outcome: The results from the in vitro test provide a mechanistic understanding and inform the selection of RBS libraries or promoters for the subsequent in vivo Build phase [3].

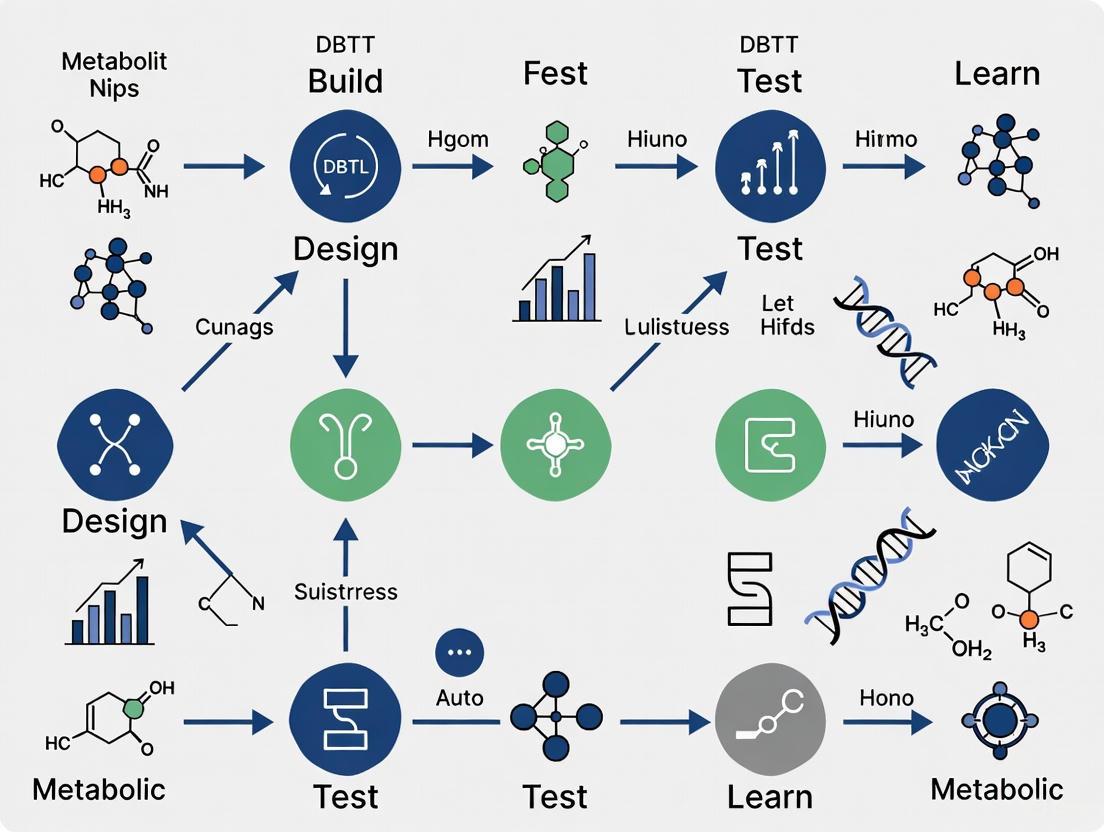

Visualization: Knowledge-Driven DBTL Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow where the Design phase is informed by preliminary in vitro experimentation.

The Build Phase

The Build phase is the physical construction of the genetically engineered organism as specified in the Design phase.

Core Objectives and Methodologies

This phase focuses on the high-throughput assembly of DNA constructs and their introduction into the microbial chassis.

- DNA Assembly: Techniques include Gibson assembly, Golden Gate assembly, and others to combine multiple DNA parts into a functional plasmid or chromosomal integration [4].

- Strain Engineering: Methods like CRISPR/Cas9, MAGE (multiplex automated genome engineering), and transformation are used to introduce the genetic constructs into the production host [2].

- Library Generation: For combinatorial optimization, researchers build diverse variant libraries by employing RBS engineering, promoter engineering, or site-saturation mutagenesis to create a spectrum of expression levels for pathway enzymes [1] [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the Build phase for metabolic engineering.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for the Build Phase

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Build Phase |

|---|---|

| Plasmid Backbones (e.g., pSEVA, pET) | Standardized vectors for gene expression; often contain selection markers (e.g., antibiotic resistance) and origins of replication [4] [3]. |

| Synthesized Gene Fragments | Codon-optimized coding sequences for the enzymes of the heterologous pathway [4] [3]. |

| Restriction Enzymes & Ligases | Molecular tools for cutting and joining DNA fragments in traditional cloning. |

| Assembly Mixes (e.g., Gibson Assembly Mix) | Enzyme mixes for seamless, homology-based assembly of multiple DNA fragments [4]. |

| Competent Cells | Chemically or electro-competent microbial cells (e.g., E. coli DH5α for cloning, production strains like E. coli FUS4.T2) prepared for DNA uptake [3]. |

The Test Phase

The Test phase involves the cultivation of the built strains and the analytical measurement of their performance.

Core Objectives and Methodologies

The goal is to acquire quantitative data on strain performance, including titer, yield, productivity (TYR), and other functional characteristics.

- Cultivation: Strains are cultivated in microplates or bioreactors under defined conditions to evaluate performance in a relevant bioprocess setting [1] [3].

- Analytical Techniques: A hierarchy of methods is used, balancing throughput and informational depth.

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Biosensors coupled to fluorescence or colorimetric outputs, or fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS), can rapidly assay thousands of variants for target molecule production [2].

- Target Molecule Detection: Chromatographic methods (GC, LC) coupled with mass spectrometry (MS) or UV detection provide confident identification and precise quantification of the target molecule and pathway intermediates, though at a lower throughput [2].

- Omics Analysis: For a limited number of top-performing strains, deep omics analysis (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) provides a systems-level view to identify pathway bottlenecks and host interactions [2].

Quantitative Data from Testing

The following table summarizes key performance metrics and analytical methods used in the Test phase.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics and Analytical Methods in the Test Phase

| Performance Metric | Description | Common Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Titer | Concentration of the target product (e.g., in mg/L or g/L) [3]. | HPLC, LC-MS, GC-MS [2]. |

| Yield | Amount of product formed per amount of substrate consumed (e.g., mg/gbiomass) [3]. | HPLC, LC-MS combined with biomass measurement [2]. |

| Productivity | Titer achieved per unit of time (e.g., mg/L/h). | Calculated from titer and fermentation time. |

| Specificity/Sensitivity | Key for biosensors; measures uniqueness and detection limit for a target molecule [4]. | Plate reader assays (fluorescence, luminescence) [4] [2]. |

The Learn Phase

The Learn phase is the analytical core of the cycle, where data from the Test phase is interpreted to generate actionable knowledge for the next Design phase.

Core Objectives and Methodologies

This phase transforms raw data into predictive models or design rules to propose more effective strains in the next iteration.

- Data Integration and Analysis: Statistical analysis is performed to identify correlations between genetic designs and performance outcomes [3].

- Machine Learning (ML): Supervised learning models (e.g., random forest, gradient boosting) are trained on the combinatorial strain data to predict the performance of untested genetic designs. These models are particularly powerful in the low-data regime typical of early DBTL cycles [1].

- Bottleneck Identification: Omics data and kinetic models are used to pinpoint specific enzymatic or regulatory steps that limit flux through the pathway [1] [2].

- Recommendation Algorithms: Using model predictions, algorithms can automatically recommend a new set of strains to build, balancing the exploration of the design space with the exploitation of high-performing regions [1].

Visualization: The Role of Machine Learning in the DBTL Cycle

Machine learning integrates into the DBTL cycle by learning from tested strains to predict new, high-performing designs.

Case Study: Optimizing Dopamine Production inE. coli

A 2025 study exemplifies the knowledge-driven DBTL cycle for producing dopamine [3].

- Design & Learn (from in vitro): The pathway from L-tyrosine to dopamine via L-DOPA was first tested in a cell-free crude lysate system. This in vitro experiment confirmed pathway functionality and informed the initial in vivo design.

- Build: A library of production strains was built in an L-tyrosine-overproducing E. coli host using RBS engineering to fine-tune the expression levels of the two key enzymes, HpaBC and Ddc.

- Test: The strains were cultivated, and dopamine production was quantified, revealing that the GC content of the Shine-Dalgarno sequence significantly influenced RBS strength and final titer.

- Learn & Re-Design: Data from the first in vivo cycle was analyzed, leading to the development of a high-performance strain.

- Outcome: The optimized strain achieved a dopamine titer of 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L, a 2.6-fold improvement over the state-of-the-art, demonstrating the power of the iterative DBTL framework [3].

The Design-Build-Test-Learn cycle is a powerful, iterative engine for metabolic engineering. Its effectiveness is heightened by the integration of upstream knowledge, advanced analytics, and machine learning. As the field evolves, new paradigms like LDBT—where machine learning pre-trained on large datasets precedes design—and the use of rapid cell-free systems for building and testing promise to further accelerate the engineering of biological systems [5].

The Role of DBTL in Systems Metabolic Engineering

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a core engineering framework in synthetic biology and systems metabolic engineering, enabling the systematic and iterative development of microbial cell factories. This rational approach has revolutionized our ability to reprogram organisms for sustainable production of valuable compounds, from pharmaceuticals to fine chemicals. Systems metabolic engineering integrates tools from synthetic biology, enzyme engineering, omics technologies, and evolutionary engineering within the DBTL framework to optimize metabolic pathways with unprecedented precision [6]. The power of the DBTL cycle lies in its iterative nature—each cycle generates data and insights that inform subsequent designs, progressively optimizing strain performance while simultaneously expanding biological understanding.

As synthetic biology has matured over the past two decades, the DBTL cycle has become increasingly central to biological engineering pipelines. Technical advancements in DNA sequencing and synthesis have dramatically reduced costs and turnaround times, removing previous barriers in the "Design" and "Build" stages [7]. Meanwhile, the emergence of biofoundries with automated high-throughput systems has transformed "Testing" capabilities, though the "Learn" phase has presented persistent challenges due to the complexity of biological systems [7]. Recent integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) promises to finally overcome this bottleneck, potentially unleashing the full potential of predictive biological design [8] [7] [9]. This technical guide examines the current state of DBTL implementation in systems metabolic engineering, providing researchers with practical methodologies and insights for advancing microbial strain development.

The Four Phases of the DBTL Cycle

Design Phase

The Design phase initiates the DBTL cycle, encompassing computational planning and in silico design of biological systems. This stage has been revolutionized by sophisticated software tools that enable precise design of proteins, genetic elements, and metabolic pathways. For any target compound, tools like RetroPath and Selenzyme facilitate automated pathway and enzyme selection by analyzing known biochemical routes and evaluating enzyme candidates based on sequence similarity, phylogenetic analysis, and known biochemical characteristics [10]. The design process involves multiple integrated components: Protein Design (selecting natural enzymes or designing novel proteins), Genetic Design (translating amino acid sequences into coding sequences, designing ribosome binding sites, and planning operon architecture), and Assembly Design (planning plasmid construction with consideration of restriction enzyme sites, overhang sequences, and GC content) [9].

A critical advancement in the Design phase is the application of design of experiments (DoE) methodologies to efficiently explore the combinatorial design space. Researchers can design libraries covering numerous variables—including vector backbones with different copy numbers, promoter strengths, and gene order permutations—then statistically reduce thousands of possible combinations to tractable numbers of representative constructs [10]. For instance, in one documented flavonoid production project, researchers reduced 2592 possible configurations to just 16 representative constructs using orthogonal arrays combined with a Latin square for gene positional arrangement, achieving a compression ratio of 162:1 [10]. This approach allows comprehensive exploration of design parameters without requiring impractical numbers of physical constructs.

Table 1: Key Software Tools for the DBTL Design Phase

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| RetroPath | Automated pathway selection | Identifies biochemical routes for target compounds |

| Selenzyme | Enzyme selection | Recommends optimal enzymes for pathway steps |

| PartsGenie | DNA part design | Designs ribosome binding sites and coding sequences |

| UTR Designer | RBS engineering | Modulates ribosome binding site sequences |

| TeselaGen | DNA assembly protocol generation | Automates design of cloning strategies |

Build Phase

The Build phase translates in silico designs into physical biological constructs, with modern approaches emphasizing high-throughput, automated DNA assembly and strain construction. Automation plays a crucial role in enhancing precision and efficiency, utilizing automated liquid handlers from platforms such as Tecan, Beckman Coulter, and Hamilton Robotics for high-accuracy pipetting in PCR setup, DNA normalization, and plasmid preparation [9]. DNA assembly methods like ligase cycling reaction (LCR) and Gibson assembly enable seamless construction of complex genetic pathways, with automated worklist generation streamlining the assembly process [10] [8].

Integration with DNA synthesis providers such as Twist Bioscience and IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies) facilitates seamless incorporation of custom DNA sequences into automated workflows [9]. Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) platforms like TeselaGen's software orchestrate the entire build process, managing protocols and tracking samples across different lab equipment while maintaining robust inventory management systems [9]. The Build phase also encompasses genome editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas and multiplex automated genome engineering (MAGE), enabling precise chromosomal integration of designed pathways [8]. These automated construction processes significantly reduce human error while increasing throughput—essential factors for exploring complex design spaces in systems metabolic engineering.

Test Phase

The Test phase involves high-throughput characterization of constructed strains to evaluate performance and gather quantitative data. Automated 96-deepwell plate growth and induction protocols enable parallel cultivation of numerous strains under controlled conditions [10]. Analytical chemistry platforms, particularly ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) with high mass resolution, provide sensitive, quantitative detection of target products and key intermediates [10]. Advanced omics technologies further enhance testing capabilities: next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms like Illumina's NovaSeq enable genotypic verification, while automated mass spectrometry setups such as Thermo Fisher's Orbitrap support proteomic and metabolomic analyses [8] [9].

The Test phase generates extensive datasets requiring sophisticated bioinformatics processing. Custom R scripts and AI-assisted data analysis tools help transform raw analytical data into actionable information [10] [9]. Centralized data management systems act as hubs for collecting information from various analytical and monitoring equipment, integrating test results with design and build data to facilitate comprehensive analysis [9]. This integration is crucial for identifying correlations between genetic designs and phenotypic outcomes, enabling data-driven decisions in subsequent learning phases.

Table 2: Analytical Methods for the DBTL Test Phase

| Method Category | Specific Technologies | Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivation & Screening | Automated microtiter plate systems, High-throughput bioreactors | Biomass formation, Substrate consumption, General productivity |

| Separations & Mass Spectrometry | UPLC-MS/MS, FIA-HRMS, Orbitrap systems | Target compound titer, Byproduct formation, Intermediate accumulation |

| Sequencing & Genotyping | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), Colony PCR | Plasmid sequence verification, Genomic integration validation |

| Multi-omics | RNA-seq, Proteomics, Fluxomics | Pathway activity, Metabolic fluxes, Regulation |

Learn Phase

The Learn phase represents the knowledge-generating component of the cycle, where experimental data is transformed into actionable insights for subsequent design iterations. This phase has traditionally presented the greatest challenges in the DBTL cycle due to biological complexity, but advances in machine learning (ML) and data science are revolutionizing this critical step [7]. Statistical analysis of results identifies the main factors influencing production—for example, in one pinocembrin production study, analysis revealed that vector copy number had the strongest significant effect on production levels, followed by promoter strength for specific pathway enzymes [10].

Machine learning algorithms process vast datasets to uncover complex patterns beyond human detection capacity, enabling accurate genotype-to-phenotype predictions [7] [9]. In one notable application, ML models trained on experimental data guided the optimization of tryptophan metabolism in yeast, demonstrating how computational approaches can accelerate pathway optimization [9]. Explainable ML advances further enhance the learning process by providing both predictions and the underlying reasons for proposed designs, deepening fundamental understanding of biological systems [7]. The learning phase increasingly incorporates mechanistic modeling alongside statistical approaches, particularly through constraint-based metabolic models like flux balance analysis (FBA) and its variants (e.g., pFBA, tFBA) [8]. This combination of data-driven and first-principles approaches creates a powerful framework for extracting maximum knowledge from each DBTL iteration.

Case Studies in Microbial Systems Metabolic Engineering

C5 Platform Chemicals from L-Lysine in Corynebacterium glutamicum

Recent applications of the DBTL cycle to Corynebacterium glutamicum demonstrate its effectiveness in developing microbial cell factories for industrial chemicals. C. glutamicum, traditionally used for amino acid production, has been engineered to produce C5 platform chemicals derived from L-lysine through systematic DBTL iterations [6]. The engineering process began with traditional metabolic engineering to enhance precursor availability, then progressed to advanced systems metabolic engineering integrating synthetic biology tools, enzyme engineering, and omics technologies within the DBTL framework [6].

Researchers applied the DBTL cycle to optimize multiple pathway parameters simultaneously, including enzyme variants, expression levels, and genetic regulatory elements. Through iterative cycling, significant improvements in C5 chemical production were achieved, although specific quantitative metrics were not provided in the available literature [6]. This case exemplifies how the DBTL cycle enables the transformation of traditional industrial microorganisms into sophisticated chemical production platforms through systematic, data-driven engineering.

Flavonoid Production in Escherichia coli

A landmark study published in Communications Biology demonstrated an integrated automated DBTL pipeline for flavonoid production in E. coli, specifically targeting (2S)-pinocembrin [10]. The pathway comprised four enzymes: phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL), chalcone synthase (CHS), and chalcone isomerase (CHI) converting L-phenylalanine to (2S)-pinocembrin with requirement for malonyl-CoA [10].

Table 3: Progression of Pinocembrin Production Through DBTL Iterations

| DBTL Cycle | Key Design Changes | Resulting Titer (mg/L) | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Library | 16 representative constructs from 2592 possible combinations | 0.002 - 0.14 | Baseline |

| Second Round | High-copy origin, optimized promoter strengths, fixed gene order | Up to 88 mg/L | 500-fold |

The dramatic improvement resulted from statistical analysis of initial results, which identified vector copy number as the strongest positive factor, followed by CHI promoter strength [10]. Accumulation of the intermediate cinnamic acid indicated PAL enzyme activity was not limiting, allowing strategic focus on other pathway bottlenecks in the second design iteration [10]. This case study exemplifies how the DBTL cycle, particularly when automated, can rapidly converge on optimal designs through data-driven iteration.

Dopamine Production in Escherichia coli

A 2025 study published in Microbial Cell Factories demonstrated a "knowledge-driven DBTL" approach for optimizing dopamine production in E. coli [3]. This innovative methodology incorporated upstream in vitro investigation using cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems to inform initial in vivo strain design, accelerating the overall engineering process. The dopamine biosynthetic pathway comprised two key enzymes: native E. coli 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase (HpaBC) converting L-tyrosine to L-DOPA, and L-DOPA decarboxylase (Ddc) from Pseudomonas putida catalyzing the formation of dopamine [3].

The knowledge-driven DBTL approach proceeded through clearly defined experimental stages:

The implementation of this knowledge-driven DBTL cycle resulted in a dopamine production strain achieving 69.03 ± 1.2 mg/L (34.34 ± 0.59 mg/gbiomass), representing a 2.6-fold improvement in titer and 6.6-fold improvement in yield compared to previous state-of-the-art in vivo production systems [3]. Importantly, the approach provided mechanistic insights into the role of GC content in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence on translation efficiency, demonstrating how DBTL cycles can simultaneously achieve both applied and fundamental advances [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools for DBTL Implementation

Successful implementation of the DBTL cycle in systems metabolic engineering requires coordinated use of specialized reagents, software, and hardware platforms. The following toolkit details essential resources for establishing DBTL capabilities.

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit for DBTL Implementation

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Assembly & Synthesis | Twist Bioscience, IDT, GenScript oligos | Provides high-quality synthetic DNA fragments for pathway construction |

| Cloning Vectors | pET system, pJNTN, Custom combinatorial vectors | Serves as backbone for pathway expression with tunable copy numbers |

| Automated Liquid Handling | Tecan Freedom EVO, Beckman Coulter Biomek | Enables high-throughput, reproducible PCR setup and DNA assembly |

| Analytical Instruments | UPLC-MS/MS, Illumina NovaSeq, Orbitrap MS | Provides quantitative data on metabolites, proteins, and DNA sequences |

| Strain Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, MAGE, RBS libraries | Enables precise genomic modifications and expression tuning |

| Software Platforms | TeselaGen, CLC Genomics, RetroPath, Selenzyme | Supports in silico design, data management, and machine learning analysis |

Experimental Protocol: Automated DBTL for Pathway Optimization

This section provides a detailed methodological framework for implementing an automated DBTL cycle, based on established protocols from recent literature [10] [3].

Pathway Design and Library Construction

Pathway Identification: Use RetroPath to identify potential biosynthetic routes to your target compound. Input the target SMILES structure and retrieve possible pathways from biochemical databases [10].

Enzyme Selection: Apply Selenzyme to select optimal enzyme sequences for each pathway step based on sequence similarity, phylogenetic analysis, and known biochemical properties [10].

DNA Part Design: Utilize PartsGenie to design ribosome binding sites with varying strengths and codon-optimized coding sequences suitable for your microbial chassis [10].

Combinatorial Library Design:

- Define design parameters: promoter strengths (strong/weak/none), RBS variants, gene order permutations, and vector backbones with different copy numbers

- Apply Design of Experiments (DoE) with orthogonal arrays to reduce library size while maintaining representative coverage

- For the pinocembrin case, 2592 combinations were reduced to 16 constructs (compression ratio 162:1) [10]

Automated Assembly Protocol Generation: Use software like TeselaGen's platform to generate detailed DNA assembly protocols, specifying cloning method (Gibson, Golden Gate, LCR), fragment preparation, and reaction conditions [9].

High-Throughput Strain Construction

DNA Preparation:

- Order synthetic DNA fragments from commercial providers (Twist Bioscience, IDT)

- Amplify parts via PCR using automated liquid handlers

- Normalize DNA concentrations robotically [10]

Automated Assembly:

- Set up ligase cycling reactions (LCR) or Gibson assemblies using robotic platforms

- Follow automated worklists generated by design software

- Transform into appropriate cloning strain (E. coli DH5α commonly used) [10]

Quality Control:

Screening and Analytics

Cultivation:

- Inoculate verified constructs into 96-deepwell plates containing appropriate medium

- Implement automated growth and induction protocols

- Maintain controlled conditions (temperature, shaking) throughout cultivation [10]

Metabolite Extraction:

- Implement automated quenching and extraction protocols

- Use standardized solvent systems for metabolite recovery

- Include quality control samples and internal standards [10]

Quantitative Analysis:

Data Processing:

- Utilize custom R scripts for data extraction and processing

- Normalize measurements to biomass and internal standards

- Perform quality assessment and remove outliers [10]

Data Analysis and Learning

Statistical Analysis:

- Apply ANOVA to identify significant factors influencing production

- Calculate main effects and interaction effects between design parameters

- For the pinocembrin case, vector copy number showed P value = 2.00 × 10^-8, CHI promoter P value = 1.07 × 10^-7 [10]

Machine Learning Application:

Mechanistic Insight Generation:

- Analyze accumulation of intermediates to identify pathway bottlenecks

- Correlative expression levels with flux measurements

- Formulate testable hypotheses for next DBTL cycle [3]

Emerging Trends in DBTL Implementation

The DBTL cycle continues to evolve with several transformative trends shaping its application in systems metabolic engineering. Machine learning integration is becoming increasingly sophisticated, with explainable AI providing both predictions and underlying reasons for proposed designs [7]. Graph neural networks (GNNs) and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) represent particularly promising approaches for capturing complex biological relationships [8]. Automation and biofoundries are expanding capabilities, with the Global Biofoundry Alliance establishing standards for high-throughput engineering [7]. The emergence of cloud-based platforms for biological design enables enhanced collaboration and data sharing while providing access to advanced computational resources [9].

The knowledge-driven DBTL approach, exemplified by the dopamine production case, represents a significant advancement over purely statistical design [3]. By incorporating upstream in vitro investigation and mechanistic understanding, this strategy accelerates the learning process and reduces the number of cycles required to achieve optimization targets. Similarly, the integration of cell-free systems for rapid pathway prototyping provides a complementary approach to whole-cell engineering, enabling faster design iteration [3].

The DBTL cycle has established itself as the foundational framework for systems metabolic engineering, enabling systematic optimization of microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical production. Through iterative design, construction, testing, and learning, researchers can progressively refine complex biological systems despite their inherent complexity. The cases reviewed herein—from C5 chemical production in C. glutamicum to flavonoid and dopamine production in E. coli—demonstrate the remarkable effectiveness of this approach across diverse hosts and target compounds.

As DBTL methodologies continue to advance through increased automation, improved computational tools, and enhanced machine learning capabilities, the precision and efficiency of metabolic engineering will further accelerate. These developments promise to unlock new possibilities in sustainable manufacturing, therapeutic development, and fundamental biological understanding, firmly establishing the DBTL cycle as an indispensable paradigm for 21st-century biotechnology.

From Sequential Debottlenecking to Combinatorial Pathway Optimization

The establishment of efficient microbial cell factories for the production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and high-value chemicals represents a central goal of industrial biotechnology. Achieving this requires the precise optimization of metabolic pathways to maximize flux toward desired products while maintaining cellular viability. For decades, the predominant framework for this optimization was sequential debottlenecking—a methodical approach where rate-limiting steps in a pathway are identified and alleviated one at a time [11]. This classical approach follows a linear problem-solving logic: identify the greatest constraint, remove it, then identify the next constraint in an iterative manner. While this strategy has yielded successes, it operates under the simplification that pathway bottlenecks act independently, an assumption that often fails in the interconnected complexity of cellular metabolism [12] [13].

The emergence of combinatorial pathway optimization marks a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, enabled by advances in synthetic biology, DNA synthesis, and high-throughput screening technologies. Rather than addressing constraints sequentially, combinatorial approaches simultaneously vary multiple pathway elements to systematically explore the multidimensional design space of pathway expression and function [12] [13]. This strategy aligns with the modern design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycle framework, which provides an iterative workflow for strain development. Within this context, combinatorial optimization allows researchers to navigate complex fitness landscapes where interactions between pathway components (epistasis) mean that the optimal combination cannot be found by optimizing individual elements in isolation [14] [1]. The transition from sequential to combinatorial approaches fundamentally transforms how metabolic engineers conceptualize and address pathway optimization, moving from a reductionist to a systems-level perspective.

Sequential Debottlenecking: Principles and Limitations

Core Methodology and Applications

Sequential debottlenecking operates on the principle that any production system contains rate-limiting steps that constrain overall throughput. The methodology follows a two-stage process: first, bottleneck identification, where the specific constraints in a process are pinpointed; and second, bottleneck alleviation, where targeted interventions are made to relieve these constraints [11]. In biomanufacturing, this typically involves analyzing process times and resource utilization across unit operations to identify which steps dictate the overall process velocity. The gold standard for identification involves perturbing cycle times in a discrete event simulation model and observing the impact on key performance indicators such as throughput or cycle time [11].

In practice, sequential optimization of metabolic pathways often involves modulating the expression level of individual enzymes, replacing rate-limiting enzymes with improved variants, or removing competing metabolic reactions. For example, in a simple two-stage production process where an upstream bioreactor step takes 300 hours and a downstream purification takes 72 hours, the bioreactor represents the clear bottleneck. No improvement to the downstream processing can increase overall throughput until the bioreactor cycle time is addressed [11]. This illustrates the fundamental logic of sequential optimization: focus engineering efforts only on the most impactful constraints.

Inherent Limitations in Biological Systems

Despite its logical appeal, sequential debottlenecking faces significant limitations when applied to complex biological systems. A primary challenge is shifting bottlenecks, where alleviating one constraint simply causes another part of the system to become limiting [14]. Metabolic control theory explains this phenomenon: minor improvements in one enzyme often render another enzyme the bottleneck of the pathway [14]. This necessitates multiple iterative cycles of identification and alleviation, making the process time-consuming and potentially costly.

The approach also struggles with epistatic interactions between pathway components, where the effect of modifying one element depends on the state of other elements [14]. In naringenin biosynthesis, for instance, beneficial TAL enzyme mutations identified in a low-copy plasmid context actually decreased production when transferred to a high-copy plasmid [14]. This context-dependence means that improvements identified in isolation may not translate to benefits in the full pathway context. Additionally, sequential methods typically miss global optimum solutions that require coordinated adjustment of multiple parameters simultaneously [1] [13]. Since biological systems exhibit nonlinear behaviors, the sequential approach of holding most variables constant while adjusting one parameter at a time is fundamentally unable to discover synergistic interactions between multiple pathway components.

Table 1: Comparison of Sequential and Combinatorial Optimization Approaches

| Feature | Sequential Debottlenecking | Combinatorial Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Reductionist, linear | Systems-level, parallel |

| Experimental Throughput | Tests <10 constructs at a time [15] | Tests hundreds to thousands of constructs in parallel [15] |

| Bottleneck Handling | Addresses one bottleneck at a time | Addresses multiple potential bottlenecks simultaneously |

| Optimum Solution | Likely finds local optimum | Capable of finding global optimum [15] |

| Epistasis Accommodation | Poorly accounts for genetic interactions | Explicitly accounts for interactions between components |

| Resource Requirements | Lower per cycle, but more cycles needed | Higher initial investment, potentially fewer cycles |

| Data Efficiency | Generates limited data for modeling | Generates rich datasets for machine learning |

Combinatorial Pathway Optimization: Concepts and Implementation

Theoretical Foundation and Key Advantages

Combinatorial pathway optimization is grounded in the recognition that metabolic pathways constitute complex systems where components interact in non-additive ways. The approach involves the simultaneous variation of multiple pathway parameters to explore a broad design space and identify optimal combinations that would be inaccessible through sequential methods [12] [13]. This strategy explicitly acknowledges that the performance of any individual pathway component depends on its metabolic context, and that the global optimum for pathway function may require specific, coordinated expression levels across multiple enzymes rather than simply maximizing each enzymatic step [1].

The key advantage of combinatorial optimization lies in its ability to overcome epistatic constraints that limit sequential approaches. As demonstrated in the naringenin biosynthesis pathway, beneficial mutations in individual enzymes can exhibit contradictory effects in different genetic contexts, creating a "rugged evolutionary landscape" that traps sequential optimization at local maxima [14]. Combinatorial methods address this challenge by allowing the parallel exploration of multiple enzyme variants and expression levels, effectively smoothing the evolutionary landscape and providing a predictable trajectory for improvement [14]. This capacity makes combinatorial approaches particularly valuable for optimizing nascent pathways where limited a priori knowledge exists about rate-limiting steps or optimal expression balancing.

Implementation Frameworks and Methodologies

Implementing combinatorial optimization requires methodologies for generating genetic diversity and screening resulting variants. The primary strategies for creating combinatorial diversity include: (1) variation of coding sequences through testing homologous enzymes from different organisms or directed evolution; (2) engineering expression levels through promoter engineering, ribosome binding site (RBS) tuning, and gene copy number modulation; and (3) combined approaches that simultaneously address both enzyme identity and expression level [16] [13].

A powerful implementation framework is the biofoundry-assisted strategy for pathway bottlenecking and debottlenecking, which enables parallel evolution of all pathway enzymes along a predictable evolutionary trajectory [14]. This approach uses a "bottlenecking" phase where rate-limiting steps are identified by creating intentional constraints, followed by a "debottlenecking" phase where libraries of enzyme variants are screened under these constrained conditions. This cycle creates selective pressure for improvements that address the specific limitations of the pathway. When combined with machine learning models like ProEnsemble to balance pathway expression, this approach has demonstrated remarkable success, enabling the construction of an E. coli chassis producing 3.65 g/L of naringenin—a significant improvement over previous benchmarks [14].

Diagram 1: Combinatorial Optimization Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the iterative process of intentional bottlenecking, library generation, and machine learning-guided debottlenecking.

The DBTL Cycle: An Integrative Framework for Metabolic Engineering

Components of the DBTL Cycle

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle provides a systematic framework for metabolic engineering that integrates both sequential and combinatorial approaches while emphasizing continuous improvement through data-driven learning [1] [3]. In the design phase, researchers specify genetic constructs based on prior knowledge and hypotheses, selecting enzyme variants, regulatory elements, and assembly strategies. The build phase involves physical construction of genetic designs using DNA assembly methods such as Golden Gate assembly, Gibson assembly, or other modular cloning systems [16]. The test phase evaluates constructed strains for performance metrics such as titer, yield, productivity, and growth characteristics. Finally, the learn phase analyzes generated data to extract insights and inform the next design cycle [1] [3].

The power of the DBTL framework lies in its iterative nature and capacity for knowledge accumulation. Each cycle generates data that improves understanding of pathway behavior and constraints, allowing progressively more sophisticated interventions in subsequent cycles. This iterative refinement is particularly powerful when combined with automation and machine learning, enabling the semi-autonomous optimization of complex pathways [1]. The DBTL cycle also provides a structure for integrating different optimization strategies—using combinatorial approaches for broad exploration of the design space initially, then applying more targeted sequential interventions once key constraints are identified.

Knowledge-Driven DBTL and Machine Learning Integration

Recent advances in DBTL implementation emphasize knowledge-driven approaches that maximize learning from each cycle. For example, incorporating upstream in vitro investigations using cell-free protein synthesis systems can provide mechanistic insights before committing to full cellular engineering [3]. This approach was successfully applied in optimizing dopamine production in E. coli, where in vitro testing informed RBS engineering strategies that resulted in a 2.6 to 6.6-fold improvement over previous benchmarks [3].

Machine learning integration represents another major advancement in DBTL implementation. ML algorithms such as gradient boosting and random forest models can analyze complex datasets from combinatorial screens to predict optimal pathway configurations [1]. These models are particularly valuable in the "learn" phase of the DBTL cycle, where they can identify non-intuitive relationships between pathway components and performance. When combined with automated recommendation tools, machine learning enables the semi-autonomous prioritization of designs for subsequent DBTL cycles, dramatically accelerating the optimization process [1]. The simulated DBTL framework allows researchers to test different machine learning methods and experimental strategies in silico before wet-lab implementation, optimizing the allocation of experimental resources [1].

Table 2: Key Experimental Methodologies in Combinatorial Pathway Optimization

| Methodology | Key Features | Applications | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Gate Assembly | Type IIS restriction enzyme-based; efficient multi-fragment assembly [15] | Pathway construction with standardized parts | Moderate to high |

| RBS Engineering | Modulation of translation initiation rates; precise fine-tuning [3] | Balancing polycistronic operons; metabolic tuning | High |

| CRISPR Screening | Pooled or arrayed screening; genome-scale functional genomics [17] | Identification of fitness-modifying genes; tolerance engineering | Very high |

| Promoter Engineering | Variation of transcriptional initiation rates; library generation [13] | Balancing multi-gene pathways; dynamic regulation | High |

| MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) | In vivo mutagenesis; continuous culturing [14] | Directed evolution of pathway enzymes; genome refinement | High |

| Biosensor-Based Screening | Genetically encoded metabolite sensors; fluorescence-activated sorting [17] [12] | High-throughput screening of production strains | Very high |

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

The implementation of combinatorial pathway optimization relies on a suite of specialized reagents, tools, and technologies that enable high-throughput genetic manipulation and screening.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Combinatorial Optimization

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Cloning Toolkits | Standardized genetic parts for combinatorial assembly [16] | Golden Gate-based systems (MoClo, GoldenBraid) |

| CRISPRi/a Screening Libraries | Pooled guide RNA libraries for functional genomics [17] | Identification of gene targets affecting production or tolerance |

| Whole-Cell Biosensors | Transcription factor-based metabolite detection [17] [12] | High-throughput screening of strain libraries via FACS |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | In vitro transcription-translation for rapid prototyping [3] | Pre-testing enzyme combinations before in vivo implementation |

| Orthogonal Regulator Systems | TALEs, zinc fingers, or dCas9-based transcription control [12] | Independent regulation of multiple pathway genes |

| Barcoded Assembly Systems | Tracking library variants via DNA barcodes [12] | Multiplexed analysis of strain library performance |

| 1,2,4-Trimethoxy-5-nitrobenzene | 1,2,4-Trimethoxy-5-nitrobenzene, CAS:14227-14-6, MF:C9H11NO5, MW:213.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Nitrodiazoaminobenzene | 4-Nitrodiazoaminobenzene | High-Purity Research Chemical | High-purity 4-Nitrodiazoaminobenzene for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Comparative Analysis: Strategic Implementation Considerations

Choosing between sequential and combinatorial optimization approaches requires careful consideration of project constraints and goals. Sequential debottlenecking may be preferable when resources are limited and high-throughput capabilities are unavailable, when working with well-characterized pathways where major bottlenecks are already known, or when regulatory constraints necessitate minimal genetic modification [11] [15]. The methodical nature of sequential approaches also makes them suitable for educational settings or when establishing foundational protocols.

Combinatorial optimization is particularly advantageous when addressing complex pathways with suspected epistatic interactions, when high-throughput capabilities are available, when optimizing entirely novel pathways with limited prior knowledge, and when pursuing aggressive performance targets that require global optima rather than incremental improvements [12] [13] [15]. The higher initial investment in combinatorial approaches can be offset by reduced overall development time and superior final outcomes.

In practice, many successful metabolic engineering projects employ hybrid strategies that combine elements of both approaches. An initial combinatorial screen might identify promising regions of the design space, followed by more targeted sequential optimization to refine specific pathway components. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both methodologies while mitigating their respective limitations.

Diagram 2: Strategy Selection Workflow. This diagram illustrates decision pathways for implementing sequential, combinatorial, or hybrid optimization approaches.

The evolution from sequential debottlenecking to combinatorial pathway optimization represents significant progress in metabolic engineering methodology. While sequential approaches provide a methodical framework for addressing clear rate-limiting steps, combinatorial strategies offer a more powerful means of navigating the complex, interactive nature of metabolic networks. The DBTL cycle serves as an integrative framework that unites these approaches, emphasizing iterative improvement and data-driven learning.

Future advancements in combinatorial optimization will likely focus on enhancing automation, refining machine learning algorithms, and developing more sophisticated high-throughput screening methodologies. As these technologies mature, the distinction between sequential and combinatorial approaches may blur further, giving rise to adaptive optimization strategies that dynamically adjust their approach based on emerging data. Regardless of specific methodology, the fundamental goal remains the efficient development of microbial cell factories that can sustainably produce the chemicals, materials, and therapeutics society needs.

DBTL as a Driver for Sustainable Biomanufacturing

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a systematic, iterative framework central to advancing synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. This engineering-based approach has become fundamental for developing microbial cell factories that convert renewable substrates into valuable chemicals, thereby supporting the transition toward a circular bioeconomy. The global market for biomanufacturing is projected to reach $30.3 billion by 2027, underscoring the economic significance of these technologies [18]. Within the context of sustainable biomanufacturing, the DBTL cycle enables researchers to rapidly engineer microorganisms that can replace fossil-based production processes, mitigate anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and utilize waste streams as feedstocks [19] [20]. However, conventional strain development often faces a "valley-of-death" where promising innovations stall due to the overwhelming complexity of potential genetic manipulations and the time-consuming, trial-and-error nature of screening [19]. This challenge has catalyzed the development of next-generation DBTL frameworks that integrate automation, bio-intelligence, and machine learning to dramatically increase the speed and success rate of creating efficient biocatalysts for industrial applications.

The Core DBTL Cycle and Its Evolution

The Fundamental Workflow

The traditional DBTL cycle comprises four distinct but interconnected phases:

- Design: Researchers define objectives for the desired biological function and design genetic parts or systems using computational tools, domain knowledge, and modeling [5]. This phase includes protein design, genetic design (translating amino acid sequences into coding sequences, designing ribosome binding sites, and planning operon architecture), and assay design [9].

- Build: DNA constructs are synthesized and assembled into plasmids or other vectors, then introduced into a characterization system such as bacterial, eukaryotic, or cell-free systems [5]. This phase relies on high-precision laboratory automation including liquid handlers, PCR setup, DNA normalization, and plasmid preparation [9].

- Test: Engineered biological constructs are experimentally measured for performance through quantitative screening, often involving ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry, next-generation sequencing, or automated plate readers [9] [10].

- Learn: Data collected during testing is analyzed and compared to initial objectives to inform the next design round, increasingly using statistical methods and machine learning to identify relationships between design factors and production levels [10] [5].

This workflow closely resembles approaches used in established engineering disciplines such as mechanical engineering, where iteration involves gathering information, processing it, identifying design revisions, and implementing those changes [5].

The Bio-Intelligent DBTL (biDBTL) Framework

Recent advances have evolved the conventional DBTL cycle into a bio-intelligent DBTL (biDBTL) approach that bridges microbiology, molecular biology, biochemical engineering with informatics, automation engineering, and mechanical engineering [19]. This interdisciplinary framework incorporates:

- Novel metrics, biosensors, and bioactuators for bi-directional communication at biological-technical interfaces [20]

- Digital twins mimicking cellular and process levels [20]

- Integration of artificial intelligence to improve prediction quality and enable hybrid learning [20]

- Cellular twining through enzyme-constraint genome-scale metabolic models [19]

The bio-intelligent approach rigorously applied in projects like BIOS aims to accelerate and improve conventional strain and bioprocess engineering, opening the door to decentralized, networked collaboration for strain and process engineering [20].

The Emergence of LDBT: A Paradigm Shift

A more radical transformation proposes reordering the cycle to LDBT (Learn-Design-Build-Test), where machine learning precedes design [5]. This paradigm shift leverages:

- Zero-shot predictions from protein language models (e.g., ESM and ProGen) trained on evolutionary relationships between protein sequences [5]

- Structure-based deep learning tools (e.g., ProteinMPNN) that take entire protein structures as input and predict new sequences that fold into that backbone [5]

- Physics-informed machine learning combining predictive power of statistical models with explanatory strength of physical principles [5]

This approach potentially enables a single cycle to generate functional parts and circuits, moving synthetic biology closer to a Design-Build-Work model that relies on first principles, similar to disciplines like civil engineering [5].

Advanced DBTL Methodologies and Technologies

Machine Learning Integration in DBTL Cycles

Machine learning (ML) has become a transformative force in synthetic biology, addressing critical limitations of traditional DBTL cycles that often lead to involution states - iterative trial-and-error that increases complexity without corresponding gains in productivity [18]. ML techniques effectively capture complex patterns and multi-cellular level relations from data that are difficult to explicitly model analytically [18].

Key ML applications in DBTL include:

- Protein language models (ESM, ProGen) that capture long-range evolutionary dependencies within amino acid sequences [5]

- Structure-based design tools (MutCompute, ProteinMPNN) that associate amino acids with their chemical environment or predict sequences for specific backbones [5]

- Functional prediction models for thermostability (Prethermut, Stability Oracle) and solubility (DeepSol) [5]

- Hybrid approaches integrating evolutionary and biophysical information to enhance predictive power [5]

These data-driven techniques can incorporate features from micro-aspects (enzymes and cells) to scaled process variables (reactor conditions) for titer predictions, overcoming limitations of mechanistic models that struggle with highly nonlinear cellular processes under multilevel regulations [18].

Automation and Digital Infrastructure

Automation plays a crucial role in enhancing precision and efficiency across all DBTL phases, transforming biotech R&D workflows through:

- Advanced software platforms (e.g., TeselaGen) that generate detailed DNA assembly protocols, manage high-throughput workflows, and orchestrate laboratory automation [9]

- Automated liquid handlers (Labcyte, Tecan, Beckman Coulter, Hamilton Robotics) enabling high-precision pipetting for PCR setup, DNA normalization, and plasmid preparation [9]

- High-throughput screening systems including plate readers (EnVision Multilabel Plate Reader, BioTek Synergy HTX) and next-generation sequencing platforms (Illumina NovaSeq, Ion Torrent) [9]

- Integration with DNA synthesis providers (Twist Bioscience, IDT, GenScript) streamlining custom DNA sequence integration into lab workflows [9]

The digital infrastructure supporting automated DBTL cycles requires strategic deployment choices between cloud vs. on-premises solutions, each offering distinct advantages for scalability, collaboration, security, and compliance with regulatory requirements [9].

Cell-Free Systems for Accelerated Building and Testing

Cell-free gene expression platforms have emerged as powerful tools for accelerating the Build and Test phases of DBTL cycles. These systems leverage protein biosynthesis machinery from crude cell lysates or purified components to activate in vitro transcription and translation [5]. Key advantages include:

- Rapid protein production (>1 g/L protein in <4 hours) without time-intensive cloning steps [5]

- Scalability from picoliter to kiloliter scales, enabling high-throughput screening [5]

- Production of toxic products that would be incompatible with live cells [5]

- Facile customization of reaction environments and incorporation of non-canonical amino acids [5]

When combined with liquid handling robots and microfluidics, cell-free systems can screen upwards of 100,000 picoliter-scale reactions, generating the massive datasets required for training robust machine learning models [5].

Case Study: Automated DBTL Pipeline for Flavonoid Production

A comprehensive study demonstrated the power of an integrated, automated DBTL pipeline for optimizing microbial production of fine chemicals, specifically targeting the flavonoid (2S)-pinocembrin in Escherichia coli [10]. This case study exemplifies the quantitative improvements achievable through systematic DBTL implementation.

Experimental Design and Workflow

First DBTL Cycle Design Parameters:

- Pathway enzymes: Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), and 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL) [10]

- Expression regulation: Four vector backbones with varying copy numbers (p15a medium copy, pSC101 low copy) and promoters (Ptrc strong, PlacUV5 weak) [10]

- Combinatorial factors: Strong, weak, or no promoter for each intergenic region; 24 permutations of gene order [10]

- Library compression: 2592 possible configurations reduced to 16 representative constructs using design of experiments (DoE) with orthogonal arrays and Latin square for positional arrangement [10]

Build Phase:

- Automated ligase cycling reaction for pathway assembly on robotics platforms [10]

- Commercial DNA synthesis followed by part preparation via PCR [10]

- High-throughput automated plasmid purification, restriction digest, and capillary electrophoresis for quality control [10]

Test Phase:

- HTP 96-deepwell plate-based growth pipeline [10]

- Automated extraction and quantitative screening via fast UPLC coupled to tandem mass spectrometry with high mass resolution [10]

- Custom R scripts for data extraction and processing [10]

Learn Phase:

- Statistical analysis identifying relationships between design factors and production levels [10]

- Vector copy number showed strongest significant effect on pinocembrin levels (P value = 2.00 × 10â»â¸) [10]

- CHI promoter strength had positive effect (P value = 1.07 × 10â»â·) [10]

- Weaker effects observed for CHS, 4CL, and PAL promoter strengths [10]

- High accumulation of intermediate cinnamic acid suggested PAL activity wasn't limiting [10]

Second DBTL Cycle Optimizations:

- High copy number origin (ColE1) selected for all constructs [10]

- CHI position fixed at pathway beginning to ensure direct promoter placement [10]

- 4CL and CHS allowed to exchange positions with no, low, or high strength promoters [10]

- PAL location fixed at the 3' end of the assembly [10]

Quantitative Results and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance Improvement Through Iterative DBTL Cycling for Pinocembrin Production in E. coli

| DBTL Cycle | Library Size | Maximum Titer (mg/L) | Key Identified Factors | Statistical Significance (P-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Cycle | 16 constructs | 0.14 mg/L | Vector copy number | 2.00 × 10â»â¸ |

| CHI promoter strength | 1.07 × 10â»â· | |||

| CHS promoter strength | 1.01 × 10â»â´ | |||

| Second Cycle | Optimized design | 88 mg/L | High copy number backbone | Not reported |

| Strategic CHI placement | Not reported | |||

| Overall Improvement | — | 500-fold increase | — | — |

The application of two iterative DBTL cycles successfully established a production pathway improved by 500-fold, with competitive titers reaching 88 mg Lâ»Â¹, demonstrating the powerful efficiency gains achievable through automated DBTL methodologies [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Workflows

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Advanced DBTL Implementation

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in DBTL Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Design Software | RetroPath [10], Selenzyme [10], PartsGenie [10] | Automated pathway and enzyme selection, parts design with optimized RBS and coding regions |

| DNA Assembly & Cloning | Ligase Cycling Reaction (LCR) [10], Gibson Assembly [9], Golden Gate Cloning [9] | High-efficiency assembly of DNA constructs with minimal errors |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Labcyte, Tecan, Beckman Coulter, Hamilton Robotics [9] | High-precision pipetting for PCR setup, DNA normalization, and plasmid preparation |

| DNA Synthesis Providers | Twist Bioscience, IDT, GenScript [9] | Custom DNA sequence synthesis for integration into automated workflows |

| Analytical Screening | UPLC-MS/MS [10], Illumina NovaSeq [9], Thermo Fisher Orbitrap [9] | Quantitative measurement of target products, genotypic analysis, proteomic profiling |

| Cell-Free Systems | In vitro transcription/translation systems [5] | Rapid protein expression without cloning, high-throughput sequence-to-function mapping |

| Machine Learning Tools | ESM [5], ProGen [5], ProteinMPNN [5] | Zero-shot prediction of protein structure-function relationships, library design |

Industrial Applications and Sustainability Impact

Showcase Applications in Sustainable Manufacturing

The BIOS project demonstrates the industrial relevance of advanced DBTL frameworks by focusing on creating Pseudomonas putida producer strains for high-value chemicals from waste streams [19] [20]. Key showcase applications include:

- Production of (hydroxy) fatty acids and PHA from one-carbon (methanol/formate) and lignin waste streams for polyester synthesis [19]

- Terpene production for pharmaceuticals, fragrances, and biofuel precursors [20]

- Methylacrylate production for biodegradable polymers and materials [20]

- Polyolefines production from renewable resources [20]

These applications target highly attractive products with significant potential for reducing anthropogenic greenhouse footprint, supporting the transition from fossil-based production processes to a circular bioeconomy [20].

Environmental and Economic Benefits

Advanced DBTL approaches contribute substantially to sustainability goals through:

- Waste stream valorization: Converting one-carbon compounds (methanol, formate) and lignin derivatives into valuable chemicals [19]

- Fossil resource displacement: Replacing petroleum-based production with biological manufacturing routes [19] [20]

- Reduced greenhouse gas emissions: Mitigating atmospheric COâ‚‚ levels through circular bioeconomy approaches [20]

- Economic viability acceleration: Overcoming the "valley-of-death" in strain engineering through rapid, predictive design cycles [19]

The implementation of bio-intelligent DBTL cycles ultimately paves the way for decentralized bio-manufacturing through autonomous, self-controlled bioprocesses that can operate efficiently at various scales [20].

The DBTL cycle has evolved from a conceptual framework to a powerful, integrated pipeline driving sustainable biomanufacturing forward. The integration of automation, machine learning, and bio-intelligent systems has transformed metabolic engineering from a trial-and-error discipline to a predictive science capable of addressing urgent sustainability challenges. The demonstrated 500-fold improvement in production titers through iterative DBTL cycling underscores the transformative potential of these approaches [10].

Future advancements will likely focus on fully autonomous DBTL systems where artificial intelligence agents manage the entire cycle from design to learning [5]. The emergence of LDBT paradigms suggests a fundamental shift toward first-principles biological engineering, potentially reducing multiple iterative cycles to single, highly efficient design iterations [5]. As these technologies mature, DBTL-driven biomanufacturing will play an increasingly critical role in establishing a circular bioeconomy, reducing dependence on fossil resources, and mitigating the environmental impact of chemical production across diverse industrial sectors.

From Theory to Bioproduction: Implementing DBTL for Pathway and Strain Optimization

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle represents a systematic framework for accelerating biological engineering, enabling the rapid optimization of microbial strains for chemical production. This whitepaper explores the implementation of an automated DBTL pipeline for the prototyping of microbial production platforms, using the enhanced biosynthesis of the flavonoid (2S)-pinocembrin in Escherichia coli as a detailed case study. We delineate how the integration of computational design, automated genetic assembly, high-throughput analytics, and machine learning facilitates the efficient optimization of complex metabolic pathways. The application of this pipeline to pinocembrin production resulted in a 500-fold improvement in titers, achieving levels up to 88 mg Lâ»Â¹ through two iterative cycles, demonstrating a compound-agnostic and automated approach applicable to a wide range of fine chemicals [10] [21]. The methodologies, datasets, and engineered strains presented herein provide a blueprint for the application of automated DBTL cycles in metabolic engineering research and industrial biomanufacturing.

The DBTL cycle is an engineering paradigm that has been successfully adapted from traditional engineering disciplines to synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. Its iterative application is central to the rational development of microbial cell factories. In the context of metabolic engineering for natural product synthesis:

- The Design phase involves the in silico selection of biosynthetic pathways and enzymes, followed by the detailed design of genetic constructs using standardized biological parts.

- The Build phase encompasses the physical, and often automated, assembly of these designed genetic constructs into a microbial chassis.

- The Test phase focuses on cultivating the engineered strains and quantitatively evaluating their performance, typically through high-throughput analytical methods.

- The Learn phase uses statistical analysis and machine learning on the generated data to extract insights, identify bottlenecks, and inform the design of the next cycle [10] [8].

Fully automated biofoundries are now operational, leveraging laboratory robotics and sophisticated software to execute these cycles with unprecedented speed and scale. This automation is crucial for exploring the vast combinatorial space of genetic designs, a task that is intractable with manual methods [10]. This whitepaper examines a specific implementation of such a pipeline, detailing its components and efficacy through the lens of optimizing pinocembrin, a key flavonoid precursor, production in E. coli.

The Pinocembrin Production Pathway

(2S)-Pinocembrin is a flavanone that serves as a key branch-point intermediate for a wide range of pharmacologically active flavonoids, such as chrysin, pinostrobin, and galangin [22]. Its microbial biosynthesis from central carbon metabolites requires the construction of a heterologous pathway in E. coli.

- Pathway Overview: The biosynthetic route from L-phenylalanine to (2S)-pinocembrin involves four enzymatic steps:

- Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL): Deaminates L-phenylalanine to form cinnamic acid.

- 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL): Activates cinnamic acid to cinnamoyl-CoA using ATP.

- Chalcone synthase (CHS): Condenses one molecule of cinnamoyl-CoA with three molecules of malonyl-CoA to form pinocembrin chalcone.

- Chalcone isomerase (CHI): Isomerizes the chalcone to (2S)-pinocembrin [23] [24] [25].

- Host Metabolism Integration: For a sustainable bioprocess, the pathway must be supported by host metabolism. This involves enhancing the supply of the precursors L-phenylalanine, derived from the shikimate pathway, and malonyl-CoA, a central metabolite typically limiting for flavonoid production [22] [24]. Early strategies required the supplementation of expensive phenylpropanoic precursors, but recent advances have enabled production directly from simple carbon sources like glucose or glycerol [23] [22].

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic pathway for pinocembrin production in the engineered E. coli cell, highlighting the key heterologous enzymes and the supporting host metabolism.

Implementing the Automated DBTL Pipeline

The development of a high-titer pinocembrin-producing strain was achieved through an automated, integrated DBTL pipeline. This section details the specific protocols and methodologies employed at each stage.

Design Phase: In Silico Pathway and Library Design

The Design phase leverages a suite of bioinformatics tools to select and design genetic constructs for pathway expression.

- Software Tools: The pipeline uses RetroPath for automated pathway selection from a target compound and Selenzyme for selecting candidate enzymes based on desired biochemical properties [10]. The PartsGenie software is then used to design reusable DNA parts, optimizing ribosome-binding sites (RBS) and codon-usage for the coding sequences [10].

- Combinatorial Library Design: A combinatorial library of 2,592 possible pathway configurations was designed in silico by varying several genetic parameters:

- Vector Backbone: Four options with different copy numbers (e.g., ColE1 - high, p15a - medium, pSC101 - low) and promoters (Ptrc - strong, PlacUV5 - weak).

- Intergenic Regions: Three options for the region preceding each gene: a strong promoter, a weak promoter, or no promoter.

- Gene Order: All 24 permutations of the four genes (PAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI) were considered [10].

- Design of Experiments (DoE): To make the library experimentally tractable, a statistical reduction using orthogonal arrays and a Latin square for gene positioning was applied. This reduced the library from 2,592 to 16 representative constructs, a compression ratio of 162:1, enabling efficient exploration of the design space without the need for ultra-high-throughput construction and screening [10].

Build Phase: Automated DNA Assembly and Construction

The Build phase translates digital designs into physical DNA constructs using automated laboratory workflows.

- DNA Synthesis and Preparation: Protein-coding sequences are commercially synthesized. DNA parts are then prepared via PCR amplification [10].

- Automated Pathway Assembly: Assembly recipes and robotics worklists are generated by the pipeline's software (PlasmidGenie). Pathway assembly is performed using the ligase cycling reaction (LCR) on robotic platforms. This method is highly efficient for assembling multiple DNA fragments [10].

- Quality Control (QC): After transformation into E. coli, candidate plasmid clones are subjected to high-throughput QC. This involves automated plasmid purification, restriction digest analysis via capillary electrophoresis, and finally, sequence verification to confirm assembly accuracy [10]. All designed parts and plasmid assemblies are deposited in a centralized repository (JBEI-ICE) with unique identifiers for sample tracking [10].

Test Phase: High-Throughput Cultivation and Analytics

The Test phase involves cultivating the library of strains and quantifying pathway performance.

- Cultivation Protocol: Constructs are introduced into the production chassis (e.g., E. coli DH5α or engineered derivatives). Automated protocols for 96-deepwell plate cultivation are used, controlling for growth, induction of gene expression, and feeding [10].

- Analytical Chemistry: The detection and quantification of the target product (pinocembrin) and key intermediates (e.g., cinnamic acid) are critical.

- Sample Preparation: Automated extraction of metabolites from culture samples.

- Quantitative Analysis: Analysis is performed using fast ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) with high mass resolution. This provides high sensitivity and specificity [10].

- Data Processing: Custom, open-source R scripts are employed for automated data extraction and processing, converting raw instrument data into quantified metabolite titers [10].

Learn Phase: Data Analysis and Machine Learning

The Learn phase closes the loop by extracting actionable knowledge from the experimental data.

- Statistical Analysis: The measured pinocembrin titers from the 16 constructs are analyzed to identify the main factors influencing production. Techniques like Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) are used to determine the statistical significance of factors like vector copy number, promoter strength for each gene, and gene order [10].

- Insight Generation: In the initial cycle, analysis revealed that vector copy number had the strongest positive effect on pinocembrin titer, followed by the promoter strength for the CHI gene. Interestingly, high levels of the intermediate cinnamic acid accumulated across all constructs, suggesting that PAL activity was not a bottleneck, but that downstream steps might be constrained [10]. These insights directly informed the constraints and focus of the second DBTL cycle.

Case Study Data: Pinocembrin DBTL Cycle Outcomes

The iterative application of the DBTL pipeline led to significant improvements in pinocembrin production. The table below summarizes the quantitative outcomes and key design changes across two reported DBTL cycles.

Table 1: Progression of Pinocembrin Production Through DBTL Iterations

| DBTL Cycle | Key Design Changes & Rationale | Maximum Pinocembrin Titer (mg/L) | Fold Improvement | Key Learning Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | Initial combinatorial library of 16 constructs (from 2,592 designs) exploring copy number, promoter strength, and gene order. | 0.14 [10] | Baseline | Copy number and CHI promoter strength are most significant. Cinnamic acid accumulates, suggesting downstream bottlenecks. Gene order effect is negligible. |

| Cycle 2 | Library focused on high-copy backbone, fixed CHI position, and varied promoters for 4CL and CHS based on Cycle 1 learnings. | 88 [10] | ~500x | Confirmed the critical importance of high gene dosage and strong expression of CHI and other downstream enzymes. |

Subsequent research, leveraging insights from such DBTL cycles, has further advanced production capabilities by integrating host strain engineering. The following table compares production levels from different metabolic engineering strategies, highlighting the role of the optimized chassis.

Table 2: Advanced Pinocembrin Production through Host Strain Engineering

| Engineering Strategy | Key Host Modifications | Precursor Supplementation? | Maximum Pinocembrin Titer (mg/L) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Pathway Balancing | Overexpression of feedback-insensitive DAHP synthase, PAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI on multiple plasmids. | No (from glucose) | 40.02 [23] [24] | |

| Cinnamic Acid Flux Control | Screening PAL/4CL enzyme combinations; CHS mutagenesis (S165M); malonyl-CoA engineering. | Yes (L-phenylalanine) | 67.81 [25] | |

| Enhanced Chassis Development | Deletion of pta-ackA, adhE; overexpression of CgACC; deletion of fabF; integration of feedback-insensitive ppsA, aroF, pheA. | No (from glycerol) | 353 [22] |

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental workflows described rely on a suite of specialized reagents, biological parts, and software tools. The following table catalogues key resources essential for replicating or building upon this automated pipeline prototyping effort.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DBTL Pipeline Implementation

| Category | Item | Specific Example / Part Number | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes / Genes | Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase (PAL) | Arabidopsis thaliana [10], Rhodotorula mucilaginosa [25] | Converts L-phenylalanine to cinnamic acid. |

| 4-Coumarate:CoA Ligase (4CL) | Streptomyces coelicolor [10], Petroselinum crispum [25] | Activates cinnamic acid to cinnamoyl-CoA. | |

| Chalcone Synthase (CHS) | Arabidopsis thaliana [10], Camellia sinensis [22] | Condenses cinnamoyl-CoA with malonyl-CoA. | |

| Chalcone Isomerase (CHI) | Arabidopsis thaliana [10], Medicago sativa [25] | Isomerizes chalcone to (2S)-pinocembrin. | |

| Software Tools | Pathway Design | RetroPath [10] | In silico design of biosynthetic pathways. |