Advanced Biosensor Strategies for High-Yield L-Threonine Production: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cutting-edge biosensor technologies for enhancing L-threonine production in microbial systems.

Advanced Biosensor Strategies for High-Yield L-Threonine Production: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of cutting-edge biosensor technologies for enhancing L-threonine production in microbial systems. It explores the foundational principles of L-threonine biosensor design, including transcriptional regulators and riboswitches, and details methodological applications for high-throughput screening of overproducing strains and key enzymes. The content addresses common troubleshooting challenges and optimization strategies for biosensor sensitivity and specificity, while validating approaches through multi-omics integration, fermentation performance metrics, and comparative analysis with traditional methods. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and biotechnology professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances in biosensor-assisted strain development and metabolic engineering for industrial L-threonine biomanufacturing.

Understanding L-Threonine Biosensor Fundamentals: Components, Mechanisms, and Design Principles

The Critical Need for L-Threonine Biosensors in Modern Biomanufacturing

L-Threonine, an essential amino acid that cannot be synthesized by humans and animals, holds significant economic importance in the global bio-based products market. With the worldwide amino acid market reaching 10.3 million tons and gross sales of $28 billion in 2021, and projected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 6.76% over the next decade, efficient production methods have become increasingly critical [1] [2]. L-Threonine represents the third largest market size as a feed additive, creating substantial pressure to develop more efficient biomanufacturing approaches [3] [1].

Microbial fermentation is considered an economical, efficient, and environmentally friendly method for amino acid production, contributing to approximately 80% of the global amino acids yield [1] [2]. However, the development of efficient high-throughput screening technologies utilizing biosensors has been hampered by the pressing need for biosensors that specifically target critical amino acids like L-threonine [3] [1]. This whitepaper examines recent breakthroughs in L-threonine biosensor technology and their transformative potential for modern biomanufacturing.

The Screening Bottleneck in Strain Development

Historical Limitations in High-Throughput Screening

Traditional screening methods for amino acid producers have relied on chromatographic or mass spectrometry techniques, which present inherent throughput limitations, time-consuming processes, and high costs that restrict strain development efficiency [4]. Without genetically encoded biosensors, the rapid identification of high-performance microbial producers from vast mutant libraries has represented a significant bottleneck in metabolic engineering pipelines [5].

The development of microbial cell factories for L-threonine production has advanced through random mutation, metabolic engineering, and high-throughput screening approaches [1] [2]. However, until recently, biosensors for several amino acids with important applications and large market demands—including L-threonine, L-proline, L-glutamate, and L-aspartate—remained unavailable [1] [2], creating a critical technological gap in biomanufacturing optimization.

Biosensor Landscape for Amino Acids

Table 1: Available Biosensors for Amino Acid Detection

| Amino Acid Type | Biosensor Availability | Transcriptional Regulator/Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaline amino acids (L-lysine, L-arginine, L-histidine) | Available | LysG regulating LysE [1] |

| Branch-chain amino acids (L-valine, L-leucine, L-isoleucine) and L-methionine | Available | Lrp regulating BrnFE [1] |

| Aromatic amino acids (L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine, L-phenylalanine) | Available | Transcriptional regulator-based [1] |

| L-Serine | Available | SerR regulating SerE [1] |

| L-Threonine and L-Proline | Recently developed | Engineered SerR mutant (SerRF104I) [3] |

| L-Glutamate and L-Aspartate | Still unavailable | Not identified [1] |

Recent Breakthroughs in L-Threonine Biosensor Technology

Transcriptional Regulator Engineering Approach

A groundbreaking study published in 2025 successfully developed a novel transcriptional regulator-based biosensor for L-threonine through directed evolution of the transcriptional regulator SerR [3] [1] [2]. This research was inspired by the novel finding that the exporter SerE can transport L-proline in addition to its previously known substrates L-threonine and L-serine [1] [2].

The research hypothesis stemmed from the observation that most reported amino acid biosensors were constructed based on the regulatory machinery of amino acid transport. The findings suggested that if certain compounds are accepted by a transporter, they are very probably also accepted by the corresponding transcriptional regulator [1] [2]. Since SerE shares an overlapping substrate spectrum with ThrE, researchers speculated that SerR might have the potential to recognize L-threonine and L-proline besides L-serine as its effectors [1].

Through directed evolution of SerR, the mutant SerRF104I was identified, which can recognize both L-threonine and L-proline as effectors and effectively distinguish strains with varying production levels [3]. The researchers then employed this SerRF104I-based biosensor for high-throughput screening of superior enzyme mutants of L-homoserine dehydrogenase (Hom), a critical enzyme in the biosynthesis of L-threonine [3] [1].

Dual-Responding Genetic Circuit Strategy

Another innovative approach published in 2024 designed a dual-responding genetic circuit that capitalizes on the L-threonine inducer-like effect, the L-threonine riboswitch, and a signal amplification system for screening L-threonine overproducers [5]. This research marked the first demonstration of the inducer-like effect of L-threonine [5].

The biosensor was designed to respond to varying concentrations of L-threonine by incorporating the L-threonine riboswitch and a signal amplification system, extending the dose-response spectrum of signals by incorporating the lacI-Ptrc amplification system [5]. This platform effectively enhanced the performance of the enzyme and facilitated the identification of high L-threonine-producing strains from a random mutant library, resulting in 7-fold increased L-threonine production through directed evolution of the key enzyme [5].

CysB-Based Biosensor with Directed Evolution

A 2025 study developed a biosensor using the PcysK promoter and CysB protein to construct a primary L-threonine biosensor [6]. Through directed evolution of CysB, the researchers obtained the CysBT102A mutant, resulting in a 5.6-fold increase in the fluorescence responsiveness of the biosensor over the 0-4 g/L L-threonine concentration range [6].

This biosensor was utilized for iterative strain development, ultimately producing the THRM13 strain that achieved 163.2 g/L L-threonine production, with a yield of 0.603 g/g glucose in a 5 L bioreactor [6]. This represents one of the highest titers reported for L-threonine production and demonstrates the power of biosensor-assisted screening for developing industrial production strains.

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Implementation

Directed Evolution of SerR for L-Threonine Recognition

Objective: To evolve SerR to respond to L-threonine instead of its native effector L-serine [1] [2].

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Generate mutant libraries of SerR using random mutagenesis or site-saturation mutagenesis techniques

- Screening System: Clone mutant SerR libraries into a reporter system with the ser promoter controlling expression of a fluorescent protein (eYFP)

- High-Throughput Screening: Use flow cytometry to screen for mutants that produce fluorescence in response to L-threonine but not L-serine

- Characterization: Isolate positive clones and characterize dose-response relationships to L-threonine and L-proline

- Validation: Apply the evolved biosensor to screen mutant libraries of L-homoserine dehydrogenase (Hom) for enhanced L-threonine production [3] [1]

Key Results: The identified SerRF104I mutant was able to recognize both L-threonine and L-proline as effectors, enabling the identification of 25 novel Hom mutants that increased L-threonine titers by over 10% [3].

Dual-Responding Genetic Circuit Implementation

Objective: Develop a genetic circuit that responds to intracellular L-threonine concentrations for high-throughput screening [5].

Methodology:

- Circuit Design: Construct a genetic circuit containing:

- L-threonine riboswitch for primary detection

- Signal amplification system using lacI-Ptrc

- Reporter gene (eGFP) for quantification

- Validation: Test circuit responsiveness to exogenous L-threonine supplementation

- Library Screening: Apply the biosensor to screen RBS libraries and random mutant libraries

- Fermentation Validation: Verify enhanced production in selected strains using bioreactor fermentation [5]

Key Results: The platform enabled pathway optimization and directed evolution of the key enzyme thrA, enhancing L-threonine production by 4 and 7-fold, respectively [5].

CysB-Based Biosensor Refinement

Objective: Develop a sensitive L-threonine biosensor by engineering the CysB transcriptional regulator [6].

Methodology:

- Promoter Screening: Use transcriptomic analysis to identify promoters responsive to L-threonine addition

- Biosensor Construction: Combine the PcysK promoter with CysB regulator and eGFP reporter

- Directed Evolution: Create CysB mutant libraries and screen for enhanced responsiveness

- Biosensor-Assisted Screening: Use evolved biosensor for high-throughput screening of mutant libraries

- Strain Validation: Combine with multi-omics analysis and metabolic engineering to maximize production [6]

Key Results: Identification of CysBT102A mutant with significantly enhanced responsiveness, leading to development of strains producing 163.2 g/L L-threonine [6].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Comparison of L-Threonine Biosensors

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Recent L-Threonine Biosensors

| Biosensor Type | Key Mutant/Component | Responsiveness Range | Production Improvement | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Regulator-Based [3] [1] | SerRF104I | Responds to both L-threonine and L-proline | >10% titer increase for 25 Hom mutants | High-throughput screening of L-homoserine dehydrogenase mutants |

| Dual-Responding Genetic Circuit [5] | L-threonine riboswitch + lacI-Ptrc amplification | Not specified | 7-fold increase through thrA evolution | Pathway optimization and directed evolution of key enzymes |

| CysB-Based Biosensor [6] | CysBT102A | 0-4 g/L (5.6-fold increase in fluorescence response) | 163.2 g/L titer (0.603 g/g glucose yield) | Multi-omics guided metabolic network optimization |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for L-Threonine Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Component | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Regulators | Sensory components for biosensors | SerR, CysB, LysG [3] [1] [6] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Quantitative output signal | eYFP, eGFP [3] [5] [6] |

| Riboswitches | RNA-based sensing elements | L-threonine riboswitch [5] |

| Directed Evolution Systems | Generating mutant libraries | Random mutagenesis, site-saturation mutagenesis [3] [6] |

| Flow Cytometry | High-throughput screening | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [4] |

| Multi-Enzyme Complexes | Metabolic pathway optimization | Cellulosome-based assemblies [4] |

Visualizing Biosensor Engineering Workflows

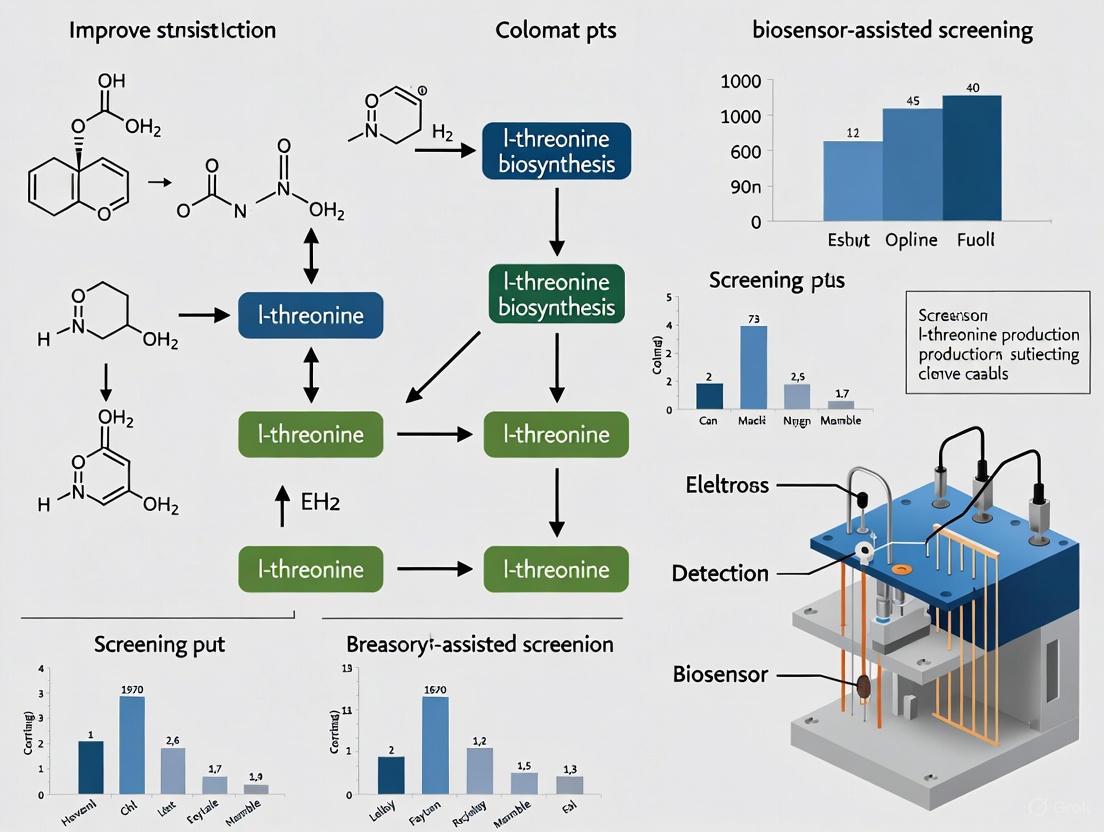

Diagram 1: L-Threonine Biosensor Development Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive approach from target identification to industrial application, highlighting three primary engineering strategies and their implementation pathways.

Molecular Mechanisms of Transcriptional Regulator-Based Biosensors

Diagram 2: Molecular Mechanism of Engineered L-Threonine Biosensor. This diagram compares the native SerR system specific to L-serine with the engineered SerRF104I mutant that responds to L-threonine, enabling high-throughput screening applications.

Future Perspectives and Industrial Applications

The development of robust L-threonine biosensors represents a transformative advancement for industrial biomanufacturing. These tools enable rapid identification of high-performance producers from extensive mutant libraries, significantly accelerating the strain development pipeline [3] [5] [6]. The integration of biosensors with multi-omics analysis and metabolic network optimization creates a powerful systems biology approach to maximizing L-threonine production [6].

Future directions will likely focus on expanding biosensor applications beyond screening to include dynamic regulation of metabolic pathways, enabling real-time optimization of L-threonine biosynthesis during fermentation [1]. Additionally, the combination of different biosensor architectures—transcriptional regulator-based, riboswitch-based, and translation-based systems—may create orthogonal sensing systems with enhanced specificity and dynamic range [5] [6].

As the global biosensors market continues to expand, projected to grow significantly between 2025 and 2030 [7], the integration of these technologies with artificial intelligence and machine learning will further enhance their predictive capabilities and industrial utility. The convergence of biosensor technology, multi-enzyme complex engineering, and advanced fermentation optimization promises to redefine the economic landscape of L-threonine manufacturing, creating more sustainable and cost-effective production platforms to meet growing global demand [4] [6].

Transcription factor-based biosensors are powerful tools in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, serving as critical components for dynamic control of metabolic pathways, real-time monitoring of intracellular metabolites, and high-throughput screening (HTS) of industrial microbial strains [8] [9]. These biosensors function by utilizing transcription factors (TFs) to detect specific analytes and regulate gene expression, thereby linking biological signals to measurable outputs such as fluorescence, luminescence, or colorimetric changes [9]. Their mechanism involves three main steps: analyte recognition, signal transduction, and output generation [9].

Within the context of improving L-threonine production, the development of efficient biosensors has become particularly valuable. L-threonine, an essential amino acid with significant applications in animal feed, food products, and pharmaceuticals, represents a multi-billion-dollar market [10] [1]. Despite its economic importance, the development of high-performance microbial producers has been hampered by the lack of specific, sensitive biosensors for this amino acid [1] [5]. This technical guide focuses on two central transcriptional regulators—CysB and SerR—that have been successfully engineered to address this limitation, detailing their native recognition mechanisms, engineering strategies, and applications in biosensor-assisted screening for L-threonine overproduction.

The CysB Transcriptional Regulator

Native Structure and Function

CysB is a member of the large bacterial LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family, which represents one of the most prevalent TF families in prokaryotes [11] [12]. Like most LTTRs, CysB functions as a homotetramer where each subunit contains an N-terminal winged-helix-turn-helix (wHTH) DNA-binding domain connected to a C-terminal effector-binding domain by a helical hinge region [11]. CysB is best known as the master regulator of sulfate metabolism and cysteine biosynthesis in Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica [13] [11].

The activation of CysB target genes generally requires the effector molecule N-acetyl-L-serine (NAS), which derives from an intermediate in the cysteine biosynthetic pathway [11]. Structural studies have revealed that CysB possesses two distinct allosteric ligand binding sites: a sulfate and NAS-specific site-1, and a second NAS and O-acetylserine (OAS)-specific site-2 [13]. These ligands bind through an induced-fit mechanism, with OAS binding to site-2 remarkably remodeling site-1, indicating allosteric coupling between the two sites [13]. This allosteric coupling between the two ligand binding sites and the DNA-binding domain underlies the key feature of CysB activation [13].

Engineering CysB for L-Threonine Biosensing

Despite its natural specificity for sulfur metabolism intermediates, CysB has been successfully engineered to respond to L-threonine through directed evolution. In one groundbreaking study, researchers developed a biosensor for L-threonine by utilizing the PcysK promoter and CysB protein to construct a primary detection system [10]. Through directed evolution of CysB, they obtained a mutant (CysB-T102A) with significantly enhanced responsiveness to L-threonine [10].

The engineering process involved constructing an initial fluorescent reporter system using the PcysK promoter linked to eGFP. The biosensor was further refined by tandemly linking the CysB protein to create a pSensor construct. Critical enhancement came from directed evolution, where the CysB-T102A mutant was identified, exhibiting a 5.6-fold increase in fluorescence responsiveness across the 0–4 g/L L-threonine concentration range compared to the original biosensor [10]. This engineered biosensor was then deployed for high-throughput screening of mutant libraries, ultimately contributing to the development of a production strain (THRM13) that achieved 163.2 g/L L-threonine with a yield of 0.603 g/g glucose in a 5 L bioreactor [10].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Native and Engineered CysB Biosensors

| Parameter | Native CysB Function | Engineered CysB (T102A) for L-Threonine |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Effectors | O-acetylserine (OAS), N-acetylserine (NAS) | L-threonine |

| Response Range | Sulfur metabolites | 0–4 g/L L-threonine |

| Fluorescence Responsiveness | Not applicable to threonine | 5.6-fold improvement |

| Application | Sulfur assimilation regulation | High-throughput screening of L-threonine producers |

| Production Outcome | Cysteine biosynthesis | 163.2 g/L L-threonine in bioreactor |

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic differences between native CysB and the engineered CysB-T102A variant in their response to respective effectors:

The SerR Transcriptional Regulator

Native Structure and Function

SerR is another LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) found in Corynebacterium glutamicum, where it naturally controls the expression of the SerE exporter gene [1]. SerE was originally characterized as an exporter for L-serine and L-threonine, with SerR acting as its transcriptional activator in response to intracellular L-serine concentrations [1]. Like CysB, SerR contains the characteristic N-terminal DNA-binding domain and C-terminal effector-binding domain typical of LTTR family proteins.

The natural function of SerR involves sensing intracellular L-serine levels and activating the expression of SerE for serine excretion, representing a classic feedback regulation mechanism for amino acid homeostasis [1]. This regulatory system shares overlapping substrate specificity with ThrE, another exporter capable of transporting L-serine, L-threonine, and L-proline, suggesting potential evolutionary relationships between these transport systems and their regulatory components [1].

Engineering SerR for Dual L-Threonine and L-Proline Biosensing

The engineering of SerR for L-threonine biosensing followed a different approach than CysB, capitalizing on the observed overlap between the substrate spectra of SerE and ThrE exporters. Researchers hypothesized that SerR might have the inherent potential to recognize L-threonine and L-proline in addition to its native effector, L-serine [1]. However, while wild-type SerR responded specifically to L-serine, it showed no significant response to L-threonine or L-proline [1].

Through directed evolution of SerR, researchers identified a key mutant (SerR-F104I) that gained the ability to recognize both L-threonine and L-proline as effectors while effectively distinguishing strains with varying production levels [1]. This single amino acid substitution fundamentally altered the effector specificity of the transcription factor, enabling its application in biosensor development.

The resulting SerR-F104I-based biosensor was successfully employed for high-throughput screening of superior enzyme mutants in L-threonine and L-proline biosynthesis pathways [1]. Specifically, the biosensor identified 25 novel mutants of L-homoserine dehydrogenase (Hom) that increased L-threonine titers by over 10%, with six mutants showing performance similar to the most effective variants reported in the literature [1].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of SerR-Based Biosensor System

| Parameter | Wild-type SerR | SerR-F104I Mutant |

|---|---|---|

| Native Effector | L-serine | L-serine |

| Engineered Effectors | None | L-threonine, L-proline |

| Screening Output | Not applicable to threonine | 25 beneficial Hom mutants identified |

| Production Improvement | Not applicable | >10% increase in L-threonine titer |

| Key Mutation | N/A | F104I substitution |

The engineering workflow and application of the SerR-F104I biosensor are visualized in the following diagram:

Comparative Analysis of Recognition Mechanisms

Structural Basis for Effector Specificity

The structural characterization of these transcriptional regulators provides insights into their recognition mechanisms. CysB employs a sophisticated dual-site allosteric control system where site-1 is specific for sulfate and NAS, while site-2 accommodates both NAS and OAS [13]. The induced-fit binding mechanism and allosteric coupling between these sites enable precise metabolic sensing. The CysB-T102A mutation likely alters this allosteric network, modifying the effector binding pocket to accommodate L-threonine while maintaining the ability to activate transcription.

For SerR, the F104I mutation represents a more subtle modification that nonetheless significantly expands effector specificity. The phenylalanine to isoleucine substitution likely reduces steric hindrance in the binding pocket, allowing the bulkier L-threonine and L-proline molecules to be accommodated while maintaining recognition of the native L-serine effector. This demonstrates how single amino acid changes can dramatically alter effector specificity in LTTR family proteins.

Performance Characteristics for L-Threonine Detection

When deployed in biosensing applications, both engineered systems show distinct performance characteristics. The CysB-based biosensor demonstrated a linear response across the 0–4 g/L L-threonine concentration range, with the T102A mutation providing a 5.6-fold enhancement in fluorescence responsiveness [10]. This sensitivity range is particularly suitable for industrial strain development, where high metabolite concentrations are typically encountered.

The SerR-F104I-based biosensor enabled identification of enzyme variants that improved L-threonine production by over 10%, demonstrating its practical utility in metabolic engineering pipelines [1]. The dual specificity for L-threonine and L-proline may be advantageous in certain screening contexts but could require additional controls when absolute specificity is required.

Table 3: Comparison of Engineered Biosensor Systems for L-Threonine

| Characteristic | CysB-T102A System | SerR-F104I System |

|---|---|---|

| Base Transcription Factor | CysB (E. coli) | SerR (C. glutamicum) |

| Engineering Approach | Directed evolution of binding domain | Single point mutation (F104I) |

| Key Mutation | T102A | F104I |

| Dynamic Range | 0–4 g/L L-threonine | Not specified |

| Responsiveness Improvement | 5.6-fold increase | Enabled threonine response |

| Additional Specificities | Sulfur metabolites | L-proline, L-serine |

| Screening Outcome | 163.2 g/L production | >10% titer improvement |

| Best Application | Industrial high-throughput screening | Enzyme evolution studies |

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Implementation

Protocol for CysB-Based Biosensor Construction and Screening

The development of CysB-based L-threonine biosensors follows a multi-stage process involving initial biosensor construction, directed evolution, and validation [10]:

Primary Biosensor Construction:

- Amplify the complete non-coding regions of candidate genes (e.g., PcysK) from E. coli genome using PCR

- Ligate the non-coding region sequences, linearized pTrc99A vector, and eGFP reporter using a seamless cloning kit

- Transform reaction products into E. coli DH5α and culture on LB agar plates for 12 hours at 37°C

- Include appropriate controls (e.g., promoterless eGFP and constitutive promoter J23119-driven eGFP)

Biosensor Validation:

- Select positive transformants and inoculate into 24-well plates containing LB medium with varying L-threonine concentrations (0, 10, 20, 30 g/L)

- Incubate cultures for 8 hours at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm

- Measure eGFP fluorescence of transformants across different L-threonine concentrations

- Screen for plasmids with linear positive response to L-threonine

Directed Evolution of CysB:

- Use error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis to create CysB mutant libraries

- Screen for enhanced fluorescence responsiveness across the 0–4 g/L L-threonine range

- Identify and characterize beneficial mutations (e.g., T102A)

High-Throughput Screening Application:

- Employ the optimized biosensor in combination with random mutagenesis or targeted library creation

- Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or microtiter plate screening to identify high producers

- Validate selected strains in controlled bioreactor conditions

Protocol for SerR-Based Biosensor Implementation

The implementation of SerR-based biosensors for L-threonine screening involves the following key steps [1]:

Biosensor Assembly:

- Clone the SerR-F104I mutant gene under a constitutive promoter

- Clone the serE promoter (or other SerR-regulated promoter) upstream of a fluorescent reporter (eYFP)

- Assemble both components in a suitable plasmid vector

Biosensor Characterization:

- Transform the biosensor into the screening host strain

- Cultivate transformants in media with varying L-threonine concentrations

- Measure fluorescence output and determine dose-response characteristics

- Establish the dynamic range and detection limit for L-threonine

Library Screening:

- Introduce the target library (e.g., homoserine dehydrogenase variants) into the biosensor-equipped strain

- Culture the library under appropriate induction conditions

- Use fluorescence-based sorting or screening to isolate high-performing variants

- Validate hits in production assays

Strain Development:

- Combine beneficial mutations from screening with other metabolic engineering strategies

- Employ iterative cycles of mutagenesis and screening for continuous improvement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Transcriptional Regulator Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Biosensor assembly and reporter expression | pTrc99A, pET-30a-trc [10] [5] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Quantitative output measurement | eGFP, eYFP [10] [1] |

| Seamless Cloning Kits | Assembly of genetic circuits | MultiF Seamless Assembly Mix [10] |

| DNA Polymerases | PCR amplification for cloning and mutagenesis | Phanta Flash Master DNA Polymerase, Green Taq Mix [5] |

| Restriction Enzymes | DNA digestion for cloning | DpnI for library construction [10] |

| Strain Backgrounds | Host for biosensor implementation | E. coli DH5α (cloning), production strains [10] |

| Culture Media | Cell growth and induction | LB medium, high-salt LB, fermentation medium [10] |

| Microtiter Plates | High-throughput cultivation and screening | 24-well plates for initial validation [10] |

| Directed Evolution Tools | Creating genetic diversity | Error-prone PCR, site-saturation mutagenesis [10] [1] |

The engineering of transcriptional regulators CysB and SerR for L-threonine biosensing represents a significant advancement in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology. By modifying native regulatory proteins through directed evolution and rational design, researchers have developed powerful tools that enable high-throughput screening of L-threonine overproducers. The CysB-T102A variant offers high sensitivity within industrially relevant concentration ranges, while the SerR-F104I mutant provides dual specificity that may be advantageous in certain screening contexts.

The recognition mechanisms of these engineered transcription factors demonstrate how relatively minor modifications to native allosteric control systems can redirect effector specificity toward industrially relevant metabolites. The continued development of such biosensors, coupled with advanced screening technologies and computational design tools, promises to accelerate the creation of microbial cell factories for L-threonine and other valuable biochemicals. As our understanding of transcription factor structure and function deepens, the precision and efficiency of these engineering efforts will undoubtedly improve, further enhancing their impact on industrial biotechnology.

Within the framework of a broader thesis focused on enhancing L-threonine production in microbial cell factories, the development of high-throughput screening tools is paramount. While classical riboswitches—structured mRNA elements that regulate gene expression in response to ligand binding—have been engineered for amino acids like lysine, a natural, well-characterized L-threonine riboswitch has not been explicitly identified in the literature [14]. Consequently, recent research has pivoted towards engineering synthetic biology components that functionally mimic riboswitches, creating highly sensitive biosensors for detecting L-threonine and enabling the rapid selection of hyper-producing strains [10] [2]. This technical guide details the design, engineering, and application of these modern L-threonine detection systems, which are critical for advancing biosensor-assisted screening research.

Currently Developed L-Threonine Biosensing Systems

Although natural riboswitches for L-threonine are not available, significant progress has been made in developing alternative biosensor architectures. The table below summarizes the key engineered systems for L-threonine detection and their performance characteristics.

Table 1: Engineered Biosensors for L-Threonine Detection and Application

| Sensor Type / Name | Sensory Component | Reporting System | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Application Documented |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolved Transcriptional Regulator [1] [2] | SerRF104I mutant (from C. glutamicum) | Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (eYFP) | Effectively distinguished strains with varying L-threonine production levels. | High-throughput screening of superior l-homoserine dehydrogenase (Hom) mutants. |

| Engineered Transcriptional Machinery [10] | CysB-T102A mutant + PcysK promoter | Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP) | 5.6-fold increase in fluorescence responsiveness over 0–4 g/L L-threonine range. | Screening L-threonine overproducing E. coli strains; achieved 163.2 g/L titer in a bioreactor. |

| Rare Codon-Based Fluorescent Reporter [4] | GFP mRNA with L-threonine rare codons (ATC) | Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Enabled high-throughput screening via flow cytometry (FACS). | Rapid screening of mutant libraries for L-threonine high-producers. |

Experimental Protocols for Key L-Threonine Biosensors

Protocol: Employing the Evolved SerRF104I-Based Biosensor for Enzyme Screening

This protocol describes the use of the engineered transcriptional regulator SerRF104I for high-throughput screening of key enzymes in the L-threonine biosynthesis pathway [1] [2].

Biosensor Construction:

- Clone the gene encoding the evolved SerRF104I mutant regulator into an appropriate plasmid vector under a constitutive promoter.

- Place the enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (eYFP) gene under the control of the native promoter sequence that is recognized and activated by the SerR protein.

- This construct forms the core whole-cell biosensor, pSerRF104I.

Library Creation and Transformation:

- Introduce targeted mutations into the gene of the enzyme to be engineered (e.g., l-homoserine dehydrogenase, Hom, for L-threonine production) using error-prone PCR or other mutagenesis techniques.

- Co-transform the mutant enzyme library and the pSerRF104I biosensor plasmid into the host microbial strain (e.g., Corynebacterium glutamicum).

Cultivation and Screening:

- Plate the transformed cells and incubate to form individual colonies.

- Pick colonies into 96-well or 384-well deep-well plates containing liquid culture medium.

- Incubate the plates with shaking to allow for cell growth and L-threonine production.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS):

- Measure the fluorescence intensity of eYFP in each well, which correlates with intracellular L-threonine concentration.

- Set a fluorescence threshold to identify and sort the top-performing clones (e.g., those with fluorescence intensity >10% above the control strain).

Validation:

- Ferment the sorted clones in shake flasks or bioreactors.

- Quantify the final L-threonine titer using analytical methods like HPLC to confirm the increased production.

Protocol: Constructing and Using a CysB-Based Fluorescent Biosensor

This methodology outlines the development and application of a highly responsive biosensor based on the CysB transcriptional regulator and its subsequent use in strain evolution [10].

Initial Promoter Screening via Transcriptomics:

- Culture wild-type E. coli (e.g., MG1655) in the presence of varying concentrations of exogenous L-threonine (e.g., 0 g/L, 30 g/L, 60 g/L).

- Harvest cells and perform RNA-seq transcriptomic analysis.

- Identify promoters that are naturally upregulated in response to L-threonine (e.g., PcysK, PcysJ, PcysD).

Biosensor Assembly and Optimization:

- Clone the selected promoter (e.g., PcysK) upstream of a reporter gene (eGFP) to create a primary reporter system.

- Co-express the native transcriptional regulator CysB in the same system to create a functional biosensor.

- Perform directed evolution on the cysB gene to enhance sensor performance. Screen for mutants (e.g., CysB-T102A) that yield a higher dynamic range in fluorescence response to L-threonine.

Strain Screening and Multi-omics Analysis:

- Apply the optimized biosensor (e.g., pSensorThr with CysB-T102A) to screen a library of randomly mutated E. coli strains via FACS.

- Isolate high-fluorescence populations and validate L-threonine production in microtiter plates or shake flasks.

- Perform genomic sequencing and transcriptomic analysis on the best-performing mutants (e.g., THRM1, THR36-L19) to identify beneficial mutations and understand altered metabolic fluxes.

Systems Metabolic Engineering:

- Use the multi-omics data to inform in silico simulations of the genome-scale metabolic network (GSMN).

- Identify and test new genetic targets (e.g., gene knock-outs or knock-ins) to further optimize the metabolic network for L-threonine production.

- Iteratively combine the biosensor-assisted screening of random mutations with rational metabolic engineering to achieve industrial-level titers.

Workflow for Biosensor-Assisted Strain Improvement

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative cycle of developing a biosensor and using it to drive strain improvement, ultimately leading to high-level L-threonine production.

Core Regulatory Mechanism of an Engineered Transcriptional Biosensor

The diagram below details the operational mechanism of a transcriptional regulator-based biosensor, such as the engineered SerR or CysB system, at the molecular level.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents, components, and tools essential for constructing and implementing L-threonine biosensors as described in the experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for L-Threonine Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sensory Components | Core detection element; binds L-threonine or senses its presence. | Evolved transcriptional regulators (SerRF104I [2], CysB-T102A [10]), threonine-activating promoters (PcysK, PcysJ, PcysD [10] [15]). |

| Reporter Proteins | Generates quantifiable signal correlated with L-threonine concentration. | Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP [10]), Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (eYFP [1] [2]). |

| Host Strains | Chassis for biosensor operation and L-threonine production. | Escherichia coli (e.g., MG1655, production derivate TWF001 [15]), Corynebacterium glutamicum (e.g., ATCC 13032 [1] [2]). |

| Molecular Biology Kits | Essential for DNA manipulation and construct assembly. | Plasmid isolation kits, DNA polymerases for PCR (e.g., PrimerSTAR HS), seamless assembly mixes [10] [15]. |

| Screening Equipment | Enables high-throughput measurement and sorting of cells. | Flow Cytometer / Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS [4]), microplate reader for fluorescence detection. |

| Analytical Equipment | Validates L-threonine titers from screened strains. | HPLC for precise quantification of amino acids in fermentation broth [10]. |

| Fermentation Systems | Provides controlled environment for production validation. | Shake flasks, 5 L bioreactors for fed-batch fermentation with controlled dissolved oxygen and pH [10] [15]. |

Directed evolution has emerged as a powerful methodology for optimizing biosensor performance, enabling rapid screening of microbial cell factories for industrial biotechnology. This technical guide examines the directed evolution of the CysBT102A mutant biosensor, which demonstrated a 5.6-fold increase in fluorescence responsiveness across the 0-4 g/L L-threonine concentration range. The engineered biosensor enabled the development of the THRM13 strain capable of producing 163.2 g/L L-threonine with a yield of 0.603 g/g glucose in a 5L bioreactor. This case study provides researchers with comprehensive experimental protocols, quantitative performance data, and implementation frameworks for applying directed evolution to transcriptional regulator-based biosensors, with particular relevance to amino acid production optimization.

Genetically encoded biosensors constitute essential tools in metabolic engineering, serving as critical components for high-throughput screening and dynamic regulation of metabolic pathways. These biosensors typically consist of a sensing element (such as a transcription factor) that binds specific metabolites and an output module (such as fluorescent proteins) that generates a detectable signal. In industrial biotechnology, biosensors enable the rapid identification of high-performance microbial strains from vast mutant libraries, significantly accelerating the development of microbial cell factories.

Directed evolution mimics natural selection in laboratory settings, employing iterative cycles of genetic diversification and screening to enhance biomolecule functions without requiring comprehensive structural knowledge. This approach has proven particularly valuable for optimizing biosensors, where rational design is often limited by incomplete understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships. The general directed evolution workflow encompasses two fundamental phases: (1) library generation through random mutagenesis or semi-rational design to create genetic diversity, and (2) variant screening to identify individuals with improved properties, such as enhanced dynamic range, sensitivity, or specificity.

Case Study: Directed Evolution of the CysB Biosensor for L-Threonine Detection

Background and Strategic Approach

The development of L-threonine biosensors presents significant economic implications, as L-threonine represents an essential amino acid with extensive applications in animal feed, food fortification, and pharmaceutical industries. Despite previous engineering efforts, L-threonine production levels have historically lagged behind other amino acids like L-lysine and L-glutamate, creating a compelling need for improved screening technologies.

Researchers addressed this challenge by developing a transcription factor-based biosensor using the CysB protein and PcysK promoter from E. coli. The initial biosensor exhibited limited performance, necessitating optimization through directed evolution. The strategic approach encompassed multiple engineering stages: (1) initial biosensor construction using native regulatory elements, (2) directed evolution of the CysB transcriptional regulator, (3) biosensor validation and characterization, and (4) implementation in high-throughput screening for strain development [6] [10].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of CysB Biosensor Evolution

| Biosensor Variant | Fluorescence Responsiveness | Dynamic Range | L-Threonine Detection Range | Application Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary CysB Biosensor | Baseline | Not reported | 0–4 g/L | Initial screening capability |

| CysBT102A Mutant | 5.6-fold increase vs. baseline | Significantly improved | 0–4 g/L | High-yield strain selection |

| Optimized System | Maximum response | Further optimized | Not specified | THRM13 strain: 163.2 g/L L-threonine |

Molecular Mechanisms and Engineering Rationale

The CysB protein functions as a transcriptional regulator in cysteine metabolism, but exhibits cross-reactivity with L-threonine. Structural analysis revealed that the Thr102 residue plays a crucial role in effector binding and allosteric regulation. Through directed evolution, the T102A mutation was identified as a key substitution that enhanced L-threonine binding affinity and improved signal transduction efficiency. This single amino acid alteration substantially modified the protein's conformational dynamics upon ligand binding, resulting in enhanced transcriptional activation of the downstream reporter gene (eGFP) under the control of the PcysK promoter [6].

The molecular mechanism involves L-threonine binding to the CysBT102A mutant, which induces conformational changes that facilitate increased binding to the PcysK promoter region, ultimately driving enhanced eGFP expression. The improved fluorescence response directly correlates with intracellular L-threonine concentrations, enabling quantitative screening of producer strains.

Figure 1: Biosensor Mechanism: CysBT102A mutant activates eGFP expression via PcysK promoter in response to L-threonine

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Library Generation Through Directed Evolution

The directed evolution process for CysB optimization employed systematic mutagenesis and screening protocols:

Primary Library Construction:

- Template Preparation: Amplified the native cysB gene from E. coli MG1655 genomic DNA using high-fidelity PCR

- Mutagenesis Method: Employed error-prone PCR conditions with adjusted MgCl₂ and MnCl₂ concentrations to achieve mutation rates of 1-5 amino acid substitutions per gene

- Library Assembly: Cloned mutated cysB variants into plasmid vectors containing the PcysK promoter upstream of the eGFP reporter gene

- Transformation: Transformed library into E. coli DH5α host strain, achieving library sizes >10⁵ individual clones to ensure sufficient diversity coverage [6]

Screening Methodology:

- Primary Screening: Cultured transformants in 24-well plates containing LB medium supplemented with varying L-threonine concentrations (0, 2, 4 g/L)

- Incubation Conditions: 8 hours at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm

- Fluorescence Measurement: Quantified eGFP fluorescence using plate readers with excitation/emission at 488/509 nm

- Response Calculation: Normalized fluorescence values to cell density and calculated fold-change relative to non-induced controls

- Hit Identification: Selected variants showing significantly enhanced fluorescence responsiveness across the L-threonine concentration gradient [6] [10]

Biosensor Characterization and Validation

Comprehensive characterization of the CysBT102A mutant established its performance metrics:

Dose-Response Profiling:

- Cultured biosensor strains with L-threonine concentrations ranging from 0-10 g/L

- Measured fluorescence intensity at 2-hour intervals over 12-hour period

- Calculated response factors, dynamic range, and EC₅₀ values

- Determined specificity against other amino acids (L-serine, L-cysteine, L-methionine)

Specificity Assessment:

- Exposed biosensor to structurally similar amino acids at 4 g/L concentration

- Verified minimal cross-reactivity with non-target metabolites

- Confirmed maintained functionality in high-throughput screening conditions [6]

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Directed Evolution Techniques for Biosensor Engineering

| Methodology | Key Advantages | Limitations | Success Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-prone PCR | • Easy to perform• No prior structural knowledge needed• Broad mutagenesis coverage | • Mutational bias• Limited sequence space sampling• Potential for neutral mutations | • 5.6-fold improvement in fluorescence response• Identification of key T102A mutation |

| Site-saturation Mutagenesis | • Focused exploration of specific residues• Comprehensive coverage of targeted positions• Enables exploration of structure-function relationships | • Limited to predefined positions• Library size expands rapidly with multiple targets | • Targeted optimization of effector binding pocket• Reduced screening burden compared to random approaches |

| Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | • Ultra-high throughput (>10⁸ cells/hour)• Single-cell resolution• Quantitative multiparameter analysis | • Requires precise gating strategies• Equipment intensive• Signal-to-noise optimization critical | • Enabled screening of comprehensive mutant libraries• Efficient enrichment of high-performing variants |

Implementation in Metabolic Engineering and High-Throughput Screening

Integration with Strain Development Pipeline

The optimized CysBT102A biosensor was implemented in a comprehensive metabolic engineering workflow for L-threonine overproduction:

Mutant Library Generation:

- Applied random mutagenesis to L-threonine producer strains using UV mutagenesis and chemical mutagens

- Generated diverse mutant libraries with comprehensive genomic diversity

High-Throughput Screening:

- Employed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for rapid screening of mutant libraries

- Established gating parameters based on fluorescence intensity corresponding to high L-threonine production

- Sorted top 0.1-1% of population for further characterization and fermentation validation

Strain Validation:

- Validated sorted clones in shake-flask fermentation with controlled conditions

- Quantified L-threonine production using HPLC and biosensor correlation analysis

- Identified THRM13 as lead strain with superior production characteristics [6]

Systems Metabolic Engineering Integration

The biosensor-driven screening was complemented with multi-omics analysis and computational modeling:

Multi-omics Analysis:

- Conducted transcriptomic profiling of producer strains to identify differential gene expression

- Performed metabolic flux analysis to quantify pathway activities

- Integrated multi-omics data to identify non-intuitive metabolic bottlenecks

In Silico Modeling:

- Utilized genome-scale metabolic models (GSMN) to simulate metabolic fluxes

- Predicted gene knockout and overexpression targets for enhanced production

- Optimized carbon allocation toward L-threonine biosynthesis

Combined Engineering Approach:

- The integrated strategy coupling biosensor-driven high-throughput screening with systems metabolic engineering enabled the development of the THRM13 strain, achieving unprecedented L-threonine titers of 163.2 g/L with a yield of 0.603 g/g glucose [6] [16].

Figure 2: High-Throughput Screening Workflow: Integrating biosensor screening with systems metabolic engineering

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Directed Evolution

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Implementation in CysB Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Strains | E. coli DH5α, MG1655, CGMCC 1.366-Thr | Biosensor host, production host, mutagenesis platform | DH5α for biosensor characterization; MG1655 for genomic template [6] [4] |

| Vector Systems | pTrc99A, pET22b(+) | Expression vector with inducible promoters | pTrc99A for biosensor construction with PcysK promoter [6] |

| Polymerases & Cloning | Phanta HS Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, Seamless Assembly Mix | Error-prone PCR, library construction, pathway assembly | High-fidelity PCR for gene amplification; seamless cloning for vector construction [6] [17] |

| Reporter Proteins | eGFP, eYFP, StayGold variants | Fluorescent output for biosensor signal quantification | eGFP as primary reporter for CysB biosensor [6] [18] |

| Selection Markers | Chloramphenicol, Spectinomycin resistance | Plasmid maintenance, mutant selection | Antibiotic selection for library maintenance [17] |

| Analytical Instruments | Flow cytometers, HPLC systems, Plate readers | High-throughput screening, metabolite quantification | FACS for library screening; HPLC for L-threonine validation [6] [4] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The successful directed evolution of the CysBT102A biosensor demonstrates the power of combining molecular engineering with systems metabolic approaches. Several key insights emerge from this case study:

Critical Success Factors:

- Library Quality: The balance between mutation rate and functional protein yield was essential for identifying productive mutations

- Screening Throughput: Implementation of FACS enabled comprehensive library coverage with quantitative selection parameters

- Multi-level Optimization: Integration of promoter engineering, RBS optimization, and protein evolution created synergistic performance improvements

Technical Limitations and Considerations:

- Dynamic Range Constraints: Even optimized biosensors may have limited linear ranges requiring careful calibration

- Host Dependency: Biosensor performance can vary across genetic backgrounds necessitating host-specific validation

- Metabolic Burden: High-copy biosensor plasmids can impact host metabolism, potentially confounding screening results

Emerging Methodologies: Future biosensor engineering will likely incorporate computational design approaches utilizing molecular dynamics simulations to predict functional insertion sites and conformational changes. Recent advances in machine learning algorithms for predicting mutation effects promise to reduce library sizes and increase success rates. Additionally, CRISPR-enabled genome editing facilitates rapid implementation of metabolic engineering strategies identified through biosensor-based screening [19] [20].

The CysBT102A case study provides a robust framework for biosensor engineering applicable to diverse metabolite targets. The continued refinement of directed evolution methodologies will further accelerate the development of microbial cell factories for sustainable biochemical production.

In the pursuit of superior microbial cell factories for L-threonine production, biosensor-assisted high-throughput screening (HTS) has emerged as a transformative technology. Central to these biosensors are native promoter systems that sense intracellular L-threonine concentrations and transduce this information into detectable fluorescence signals. This technical guide examines the principles and applications of key native Escherichia coli promoters, with particular focus on the PcysK promoter and related cysteine biosynthesis promoters, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for their implementation in strain improvement programs.

Core Promoter Systems for L-Threonine Biosensing

The Cysteine Regulon Promoter Family

Multiple promoters from the cysteine biosynthesis pathway have been harnessed for L-threonine biosensing due to their natural responsiveness to threonine-mediated regulatory effects. These promoters offer varying strengths and dynamic ranges suitable for different screening applications.

Table 1: Native Promoter Systems for L-Threonine Biosensing

| Promoter | Regulatory Components | Response Mechanism | Dynamic Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PcysK | CysB binding site | CysB-threonine complex activates transcription | 5.6-fold improvement after CysB evolution [10] | High-throughput screening of mutant libraries |

| PcysJ | CysB binding site | Activated by CysB-effector complex | Linear response over 0-50 g/L [21] | FACS-based screening, dynamic regulation |

| PcysH | CysB binding site | Activated by CysB-effector complex | Linear response over 0-50 g/L [21] | FACS-based screening, dynamic regulation |

| Fusion cysJHp | Combined cysJ and cysH elements | Enhanced sensitivity to threonine | ~2x higher in producers vs non-producers [21] | Industrial strain screening |

| PcysD | CysB binding site | Activated by CysB-effector complex | Gradual response curve [22] | Transporter expression regulation |

Engineering PcysK for Enhanced Performance

The PcysK promoter represents one of the most advanced platforms for L-threonine biosensing. Native PcysK regulation involves the transcriptional activator CysB, which binds L-threonine as an effector molecule, leading to transcription activation of downstream genes. Engineering efforts have significantly enhanced this system through two primary approaches:

Directed Evolution of CysB: Through systematic mutagenesis of the CysB transcriptional regulator, researchers obtained a CysB(T102A) mutant that exhibited a 5.6-fold increase in fluorescence responsiveness across the 0-4 g/L L-threonine concentration range compared to the wild-type system [10]. This dramatic improvement enables more sensitive discrimination between high- and low-producing strains during screening.

Promoter Truncation and Optimization: Strategic removal of non-essential regulatory elements from native PcysK has yielded minimal promoters with reduced background noise and improved signal-to-noise ratios. These truncated versions maintain strong threonine responsiveness while eliminating potential interference from native regulatory networks [10].

Experimental Methodology for Promoter Characterization

Protocol: Promoter Response Profiling

Materials:

- E. coli DH5α or MG1655 strains

- High-salt LB medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl)

- L-threonine standards (0-50 g/L)

- Reporter plasmid with promoter-eGFP construct

- 24-well deep well plates

- Fluorescence microplate reader or flow cytometer

Procedure:

- Clone candidate promoter sequences upstream of eGFP reporter gene in a suitable vector backbone

- Transform constructs into appropriate E. coli host strains

- Inoculate single colonies into 24-well plates containing LB medium with varying L-threonine concentrations (0, 10, 20, 30 g/L)

- Incubate for 8-12 hours at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm

- Measure culture OD600 and eGFP fluorescence (excitation: 488 nm, emission: 509 nm)

- Calculate normalized fluorescence units (fluorescence/OD600)

- Plot dose-response curves to determine linear range and sensitivity [10] [21]

Validation Controls:

- Include promoterless eGFP construct as negative control

- Use constitutive promoter (e.g., J23119) as positive control

- Test osmotic pressure control (e.g., 30 g/L NaCl) to exclude non-specific effects [21]

Protocol: Biosensor-Assisted High-Throughput Screening

Materials:

- Mutant library (≥10^7 variants)

- FACS-compatible biosensor strain

- FACS instrument with 488 nm laser

- 96-well or 384-well microtiter plates

- Fermentation medium

Procedure:

- Transform biosensor construct into mutant library or express in biosensor strain

- Grow library to mid-log phase in appropriate medium

- Dilute and analyze using FACS, gating for highest 0.1-1% fluorescent population

- Sort positive clones into recovery medium in microtiter plates

- Incubate sorted clones for outgrowth (24-48 hours at 37°C)

- Transfer to fermentation medium for small-scale production validation

- Analyze L-threonine production using HPLC or LC-MS

- Select top performers for scale-up studies [21] [4]

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Promoter-Based Screening Systems

| System | Library Size | Screening Throughput | Validation Hit Rate | Maximum Titer Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PcysJH-eGFP | 20 million mutants | 400+ strains/week | 34/400 (8.5%) superior producers | 17.95% improvement over parent [21] |

| PcysK-CysB(T102A) | Not specified | High-throughput FACS | Significant enrichment of high-producers | 163.2 g/L in 5L bioreactor [10] |

| SerRF104I-based | Hom and ProB mutants | 25 and 13 novel mutants identified | >10% titer improvement | Multiple enzyme variants improved [3] [2] |

Advanced Engineering Strategies

Hybrid Systems for Dynamic Metabolic Regulation

Beyond conventional screening applications, L-threonine-responsive promoters enable dynamic metabolic regulation through feedback-controlled expression systems:

Transporter Expression Tuning: By replacing constitutive promoters with PcysJ, PcysD, or PcysJH upstream of L-threonine exporters (rhtA, rhtB, rhtC), researchers achieved autonomous regulation of transporter expression in response to intracellular threonine levels. This dynamic approach increased L-threonine production to 26.78 g/L (a 161% improvement) compared to constitutive expression systems, while reducing the metabolic burden associated with transporter overexpression [22].

Multi-Enzyme Complex Assembly: Recent work has demonstrated the integration of biosensor systems with synthetic enzyme complexes. By co-localizing ThrC-DocA and ThrB-CohA enzymes using cellulosome-inspired assembly systems, researchers achieved a 31.7% increase in L-threonine production through enhanced substrate channeling. This approach addresses metabolic imbalance issues common in conventional overexpression strategies [4].

Novel Biosensor Development through Transcription Factor Engineering

An alternative approach to cysteine regulon promoters involves engineering non-native transcription factors for L-threonine responsiveness:

SerR Engineering: Through directed evolution of the transcriptional regulator SerR from Corynebacterium glutamicum, researchers developed a SerR(F104I) mutant capable of responding to both L-threonine and L-proline. This novel biosensor successfully identified 25 and 13 novel mutants of homoserine dehydrogenase (Hom) and γ-glutamyl kinase (ProB), respectively, that increased target amino acid titers by over 10% [3] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Promoter Engineering Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Host Strains | E. coli MG1655, DH5α, CGMCC 1.366-Thr | Host for biosensor construction and validation |

| Vector Backbones | pCL1920 (low copy), pTrc99A, pET22b(+) | Reporter plasmid construction |

| Reporter Genes | eGFP, eYFP, lacZ, RFP | Fluorescent and colorimetric output signals |

| Selection Markers | Spectinomycin, Ampicillin | Plasmid maintenance and selection |

| Assembly Systems | Gibson Assembly, Seamless Cloning Kit | Modular promoter-reporter construction |

| Mutagenesis Tools | Error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling | Directed evolution of regulatory components |

| Analytical Instruments | FACS, HPLC, LC-MS | High-throughput screening and validation |

Visualizing Biosensor Construction and Workflows

Biosensor Development and Implementation Workflow

L-Threonine Biosensing Mechanism with CysB/PcysK System

The strategic selection and engineering of native promoter systems, particularly PcysK and related cysteine regulon promoters, provides a powerful foundation for biosensor-assisted improvement of L-threonine production strains. Through directed evolution of regulatory components, promoter optimization, and integration with advanced screening technologies, these systems enable rapid identification of high-performing variants from complex mutant libraries. The continued refinement of these biosensing platforms promises to accelerate the development of next-generation microbial cell factories for L-threonine and other valuable bioproducts.

The development of high-performance biosensors is a cornerstone of advanced metabolic engineering, enabling the dynamic monitoring of metabolic fluxes and high-throughput screening of industrial microbial strains. Within the specific context of microbial production of L-threonine, an essential amino acid with extensive applications in animal feed, food, and pharmaceuticals, the critical performance parameters of biosensors—dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity—directly determine the efficiency of strain optimization cycles [10] [22] [23]. These parameters dictate a biosensor's ability to accurately distinguish between high- and low-producing cells within massive mutant libraries, a capability essential for breaking through production bottlenecks in modern biomanufacturing. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core performance characteristics, framed within the applied research of improving L-threonine production, and is supplemented with structured experimental data, detailed protocols, and visualization tools to equip researchers with practical methodologies for biosensor characterization and implementation.

Core Performance Parameters of Biosensors

Quantitative Analysis of Biosensor Performance

The performance of biosensors used in L-threonine research can be quantitatively assessed and compared through several key metrics. The table below summarizes performance data from selected studies to illustrate the typical ranges and achievements in the field.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative L-Threonine Biosensors

| Sensory Element | Dynamic Range (Fold-Change) | Sensitivity / Detection Range | Key Engineering Strategy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CysB(T102A) TF | 5.6-fold increase | 0 - 4 g/L | Directed evolution of transcription factor | [10] |

| Fusion Promoter cysJHp | Near-linear response | 0 - 50 g/L | Proteomics-driven promoter discovery | [23] |

| Dual-Responding Circuit | Not specified | Effective HTS from large libraries | Combines riboswitch & inducer-like effect | [5] |

| SerR(F104I) TF | Effectively distinguished high/low producers | Applied to HTS of Hom and ProB enzymes | Directed evolution to shift effector specificity | [1] |

Defining Key Performance Parameters

Dynamic Range: This parameter defines the ratio of the biosensor's maximum output signal (e.g., fluorescence at saturating target concentration) to its minimum output signal (e.g., basal fluorescence without the target). A broader dynamic range allows for clearer distinction between microbial variants with varying production capacities. For example, directed evolution of the CysB transcription factor created a mutant (CysB(T102A)) with a 5.6-fold increase in fluorescence responsiveness over a critical L-threonine concentration range, a significant enhancement over the wild-type sensor [10]. Engineering strategies to extend the dynamic range beyond the theoretical 81-fold span of single-site binding include combining multiple receptor variants with differing affinities, which has been demonstrated to achieve a log-linear dynamic range spanning up to 900,000-fold for other biomolecules [24].

Sensitivity: Sensitivity refers to the lowest concentration of a target molecule that a biosensor can reliably detect and the steepness of its response curve within a given concentration range. It determines the biosensor's ability to identify subtle yet meaningful differences in intracellular metabolite levels among cell variants. In practice, a biosensor with a near-linear response over the expected physiological range, such as the fusion promoter cysJHp characterized between 0 and 50 g/L of extracellular L-threonine, is highly valuable for quantifying production capacity [23].

Specificity: Specificity is the biosensor's ability to respond exclusively to the target metabolite (L-threonine) without significant cross-reaction with structurally or metabolically similar molecules. This ensures that the screening process selectively enriches for mutants with enhanced L-threonine synthesis and not other amino acids. Specificity is often engineered at the ligand-binding pocket of the sensory element, as demonstrated by the development of the SerR(F104I) transcription factor, which was evolved to respond to L-threonine and L-proline while gaining this new functionality [1].

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol 1: Characterizing Dose-Response and Dynamic Range

This protocol outlines the steps for establishing a biosensor's dose-response curve, which is fundamental for determining its dynamic range and sensitivity.

- Strain Transformation and Culture: Transform the biosensor plasmid (e.g., pSensor containing PcysK-egfp and CysB(T102A)) into an appropriate host strain (e.g., E. coli DH5α) [10]. Plate on selective medium and incubate overnight.

- Preparation of Test Conditions: Inoculate single colonies into deep-well plates or culture tubes containing liquid LB medium supplemented with a gradient of L-threonine concentrations (e.g., 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 g/L). Ensure inclusion of a negative control (no promoter) and a positive control (a strong constitutive promoter like J23119) [10].

- Cultivation and Harvest: Incubate the cultures with shaking (e.g., 200-220 rpm) at 37°C until the mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8).

- Signal Measurement: Harvest 150-200 µL of culture into a 96-well microplate. Measure the fluorescence intensity (e.g., Ex/Em: 488/509 nm for eGFP) and optical density (OD600) of each sample using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Normalize the fluorescence of each sample to its OD600 to calculate the specific fluorescence. Plot the normalized fluorescence against the L-threonine concentration. Fit a curve (e.g., sigmoidal dose-response) to the data. The dynamic range is calculated as the ratio of the maximum normalized fluorescence to the minimum normalized fluorescence.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening Validation

This protocol validates biosensor performance by screening a mutant library and confirming the correlation between biosensor signal and production titer.

- Library Generation: Create a diverse mutant library of your L-threonine production strain using methods like UV mutagenesis, atmospheric and room temperature plasma (ARTP), or error-prone PCR of key genes (e.g., thrA) [5] [23].

- Biosensor Integration: Introduce the biosensor construct (e.g., pTZL2 with PcysJHp-egfp) into the mutant library via transformation or chromosomal integration [23].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Dilute the transformed library to an appropriate concentration. Use a flow cytometer or FACS sorter to analyze and sort the cell population based on fluorescence intensity. Gate and collect the top 0.1-1% of highly fluorescent cells [4].

- Validation of Sorted Clones: Plate the sorted cells to obtain single colonies. Inoculate these clones into deep-well plates containing fermentation medium. After fermentation, measure the actual L-threonine titer in the culture supernatants of individual clones using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Correlation Analysis: Plot the biosensor's fluorescence intensity (measured during growth or via flow cytometry) against the HPLC-measured L-threonine titer for each validated clone. A strong positive correlation confirms the biosensor's efficacy for HTS.

Visualizing Biosensor Engineering and Application Workflows

Biosensor-Assisted HTS for L-Threonine

Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Biosensor Development and HTS

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory Elements | CysB(T102A) transcription factor; PcysJ, PcysD, PcysJH promoters; L-threonine riboswitch | Core sensing component that binds L-threonine and initiates signal transduction | [10] [22] [5] |

| Reporter Proteins | Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP); Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein (eYFP); LacZ | Generates quantifiable output (fluorescence, color) for detection and sorting | [10] [1] [23] |

| Directed Evolution Kits | Seamless assembly kits (e.g., from ABclonal, Vazyme); Mutagenic strains | For engineering sensory elements (e.g., SerR, CysB) to improve properties like dynamic range and specificity | [10] [1] |

| HTS & Sorting Platform | Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS); Flow Cytometer | Enables high-throughput screening of mutant libraries at single-cell resolution based on biosensor signal | [4] [23] |

| Validation Analytics | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Gold-standard method for validating L-threonine titers in culture supernatants from screened clones | [22] [25] |

The precise characterization of dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity is not merely an academic exercise but a critical prerequisite for deploying biosensors in demanding metabolic engineering campaigns. The frameworks, protocols, and tools detailed in this guide provide a roadmap for researchers to rigorously evaluate and iteratively improve biosensor performance. As demonstrated in the context of L-threonine production, well-characterized biosensors are powerful engines for discovery, enabling the rapid isolation of superior microbial strains and the dynamic optimization of metabolic pathways. The continued refinement of these biological tools, guided by a deep understanding of their performance parameters, will undoubtedly accelerate the development of efficient microbial cell factories for L-threonine and a wide array of other valuable biochemicals.

Implementation Strategies: Biosensor-Assisted High-Throughput Screening and Strain Development

Constructing Fluorescent Reporter Systems for High-Throughput Screening

Fluorescent reporter systems have become indispensable tools in metabolic engineering, enabling the rapid identification of high-performance microbial strains. Within the context of improving L-threonine production, these biosensors convert intracellular metabolite concentrations into quantifiable fluorescence signals, allowing researchers to screen vast mutant libraries with single-cell resolution. The development of robust high-throughput screening (HTS) platforms has emerged as a transformative approach to overcome traditional bottlenecks in strain development, which often rely on time-consuming chromatographic analyses [10]. This technical guide examines the design principles, molecular components, and implementation strategies for constructing fluorescent reporter systems specifically applied to L-threonine overproduction in Escherichia coli, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for biosensor-assisted strain improvement.

Fundamental Biosensor Architectures for L-Threonine Detection

Rare Codon-Based Fluorescent Systems

A novel approach for monitoring intracellular L-threonine levels utilizes the principle of codon usage bias. This system employs fluorescent proteins containing a high proportion of L-threonine rare codons (ATC) in their sequences. In high-yield L-threonine strains, the abundant amino acid pool enables efficient translation of these rare codons, leading to strong fluorescence signals. Conversely, in low-producing strains, rare codon translation is inefficient, resulting in diminished fluorescence [4].

Implementation Protocol:

- Gene Selection: Identify genes with high threonine content in their amino acid sequence from microbial genomes (e.g., E. coli or Corynebacterium glutamicum)

- Codon Replacement: Replace all threonine codons in selected protein sequences with L-threonine rare codons (ATC)

- Fluorescent Protein Fusion: Link these codon-optimized sequences to fluorescent proteins (e.g., staygold variants) with identical codon replacements

- Vector Construction: Clone the constructed rare codon-fluorescent protein fusions into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pET-22b+)

- Validation: Measure fluorescence intensity across strains with known L-threonine production levels to establish correlation [4]

This system enables high-throughput screening of mutant libraries through fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), with studies demonstrating the selection of metabolically active enhanced strains by setting fluorescence intensity thresholds at 0.01% for phenotypic enrichment [4].

Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

Transcriptional regulators native to microbial systems provide the foundation for highly specific biosensor designs. For L-threonine sensing, researchers have successfully engineered the SerR transcriptional regulator from Corynebacterium glutamicum through directed evolution. Although wild-type SerR responds specifically to L-serine, a single amino acid substitution (F104I) generated a mutant (SerRF104I) capable of recognizing both L-threonine and L-proline as effectors [2].

Implementation Protocol:

- Regulator Selection: Identify transcriptional regulators associated with amino acid metabolism (e.g., LysR-type regulators)

- Directed Evolution: Create mutant libraries of the transcriptional regulator through error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis

- Reporter Construction: Fuse regulator binding sites (promoters) to fluorescent reporter genes (e.g., eYFP, eGFP)

- Screening: Screen mutant libraries for fluorescence response to target metabolite (L-threonine) using flow cytometry or microplate readers

- Characterization: Determine dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity of responsive clones [2]

This approach yielded the SerRF104I mutant, which effectively distinguishes strains with varying L-threonine production levels and has been successfully deployed for high-throughput screening of Hom (L-homoserine dehydrogenase) enzyme variants, identifying 25 novel mutants that increased L-threonine titers by over 10% [2].

Genetic Circuit Biosensors

Advanced biosensor designs incorporate synthetic genetic circuits that amplify native biological responses to L-threonine. One innovative design leverages two distinct L-threonine responsiveness mechanisms: the natural L-threonine riboswitch and the inducer-like effect of L-threonine, combined with a LacI-Ptrc signal amplification system [5].

Table 1: Comparison of L-Threonine Biosensor Architectures

| Biosensor Type | Molecular Components | Detection Mechanism | Dynamic Range | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare Codon-Based | Fluorescent proteins with threonine rare codons | Translation efficiency | Not specified | Links directly to cellular translation machinery |

| Transcription Factor-Based | Evolved SerRF104I regulator + eYFP | Transcriptional activation | Not specified | High specificity after directed evolution |

| Genetic Circuit | Thr riboswitch + LacI-Ptrc amplification | Transcriptional/Translational | 7-fold increase | Signal amplification enhances sensitivity |

| CysB-Based | PcysK promoter + CysBT102A mutant + eGFP | Transcriptional activation | 5.6-fold increase over 0-4 g/L | High sensitivity in low concentration range |

Implementation Protocol:

- Component Identification: Select native biological elements responsive to L-threonine (e.g., riboswitches, promoter elements)

- Circuit Design: Design genetic circuits that combine multiple response elements with signal amplification systems

- Response Validation: Test inducer-like effects by co-expressing with competitive pathways (e.g., lycopene biosynthesis)

- Specificity Engineering: Incorporate riboswitch elements to enhance specificity

- Amplification Integration: Implement amplification systems (e.g., LacI-Ptrc) to expand dynamic range [5]