Advanced Enzyme Manipulation Strategies for Optimizing Metabolic Pathways in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary enzyme manipulation strategies for optimizing metabolic pathways, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Advanced Enzyme Manipulation Strategies for Optimizing Metabolic Pathways in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary enzyme manipulation strategies for optimizing metabolic pathways, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of constructing heterologous pathways and selecting suitable host organisms. The piece delves into cutting-edge methodological advances, including directed evolution, enzyme immobilization, and automated in vivo engineering platforms. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects to overcome instability, immunogenicity, and regulatory hurdles. Finally, it covers validation frameworks employing machine learning for enzyme function prediction and comparative analyses to ensure clinical translatability. The synthesis of these areas offers a strategic guide for harnessing enzyme engineering to accelerate and refine the drug development pipeline.

Building the Base: Principles of Heterologous Pathways and Host Selection

Defining Heterologous Metabolic Pathways and Their Role in Bioproduction

The field of metabolic engineering is central to the development of microbial cell factories for the sustainable production of valuable chemicals. A cornerstone of this discipline is the design and implementation of heterologous metabolic pathways, defined as linked series of biochemical reactions occurring in a host organism after the introduction of foreign genes [1]. This methodology enables researchers to equip industrially-relevant microorganisms with the capability to produce compounds they do not naturally synthesize, thereby expanding the repertoire of attainable products from renewable resources. These products span a diverse range, including biofuels, pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and platform chemicals [2] [3]. The strategic insertion of these non-native pathways, framed within broader enzyme manipulation strategies, allows for the rewiring of cellular metabolism to optimize flux toward desired compounds, enhancing titers, yields, and productivity [2].

Key Concepts and Definitions

A heterologous metabolic pathway is fundamentally characterized by the introduction of genetic material from a donor organism into a heterologous host. The successful incorporation of these pathways is a multi-step process that moves beyond simple gene transfer and requires extensive optimization to achieve high production titers [1].

Essential Terminology:

- Metabolic Engineering: The science of improving product formation or cellular properties through the modification of specific biochemical reactions or the introduction of new genes using recombinant DNA technology [2].

- Host Organism: The selected microorganism (e.g., bacteria, yeast, filamentous fungi) that serves as the chassis for the heterologous pathway. The choice of host is critical and depends on factors such as its native metabolism, growth characteristics, and genetic tractability [1].

- Pathway Yield (YP): A crucial metric defined as the amount of a product formed from a substrate, computed based on the stoichiometry of the host's metabolic network [4].

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM): A computational model that comprehensively represents an organism's metabolism by integrating all metabolic reactions annotated from its genome. GEMs are used with techniques like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict metabolic behavior and identify engineering targets [4] [5].

Strategic Implementation of Heterologous Pathways

The process of establishing a functional heterologous pathway involves a series of methodical steps, from gene selection to host optimization.

A Generalized Workflow for Pathway Implementation

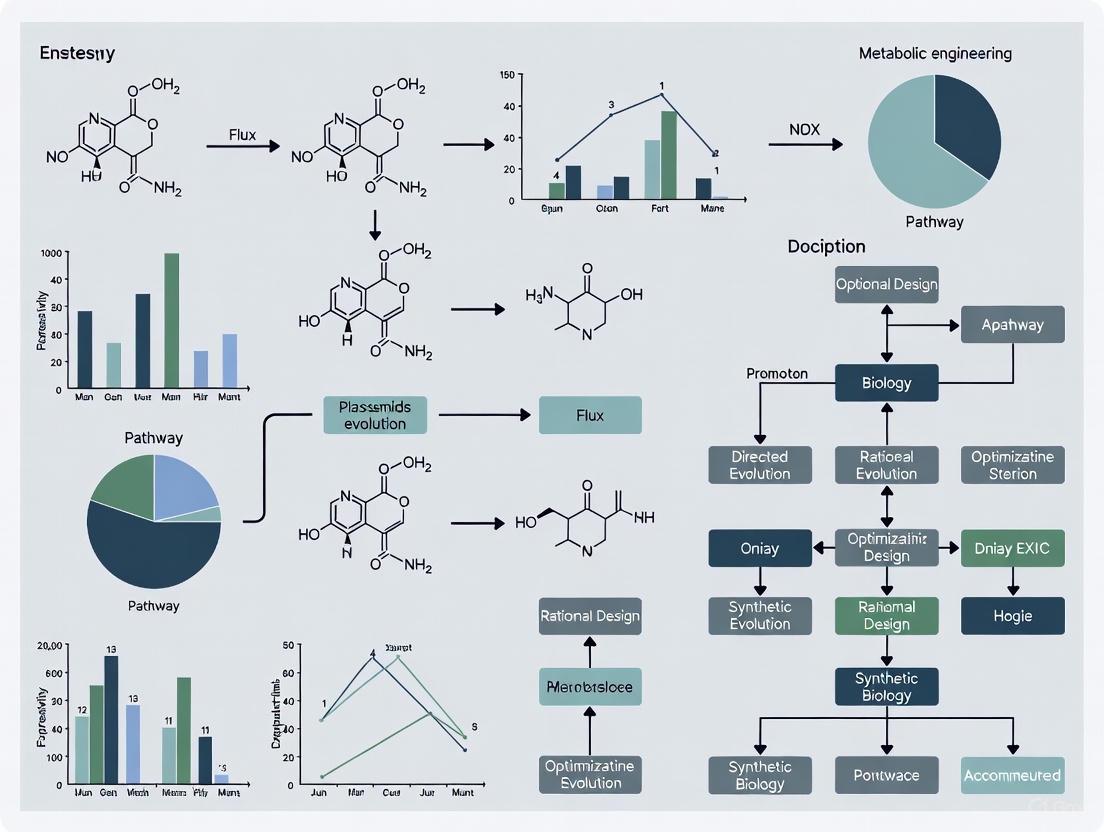

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for introducing a heterologous metabolic pathway into a host organism, from initial design to a functional optimized strain.

Critical Implementation Steps

- Isolation of Pathway Genes and Pathway Design: The initial step involves identifying and isolating the genes responsible for the biosynthesis of the target compound. For complex natural products, this may entail transferring an entire gene cluster. Computational tools and retrosynthetic algorithms are increasingly used to predict optimal pathways, including non-natural routes [1] [4].

- Selection of a Suitable Host Organism: The choice of host is a critical determinant of success. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic hosts offer distinct advantages and drawbacks [1].

- Incorporation of Genes into a Stable Vector: The isolated genes are cloned into expression vectors (e.g., plasmids) suitable for the chosen host. This involves selecting appropriate promoters, terminators, and selection markers to ensure stable maintenance and high-level expression [1].

- Optimization of the Metabolic Pathway in the Heterologous Host: Simple gene transfer is rarely sufficient. Extensive optimization is required, which can include [1] [2]:

- Enzyme Engineering: Improving enzyme kinetics, stability, or specificity.

- Cofactor Engineering: Balancing intracellular cofactor levels to support heterologous enzyme activity.

- Promoter Engineering: Fine-tuning the expression levels of each pathway gene to minimize metabolic burden and avoid the accumulation of toxic intermediates.

- Modular Pathway Engineering: Refining and balancing different modules of a pathway (e.g., precursor supply, core synthesis, redox balance) to maximize flux.

Host Organism Selection

The selection of an appropriate host organism is paramount. The table below compares the commonly used hosts in metabolic engineering projects.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Heterologous Expression Hosts [1]

| Host Organism | Key Benefits | Key Handicaps | Common Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria (E. coli) | High growth rate, well-developed genetic tools, high protein expression. | Lack of post-translational modifications for eukaryotic proteins, potential inclusion body formation. | Escherichia coli |

| Yeast | Eukaryotic protein processing, generally recognized as safe (GRAS), robust genetic tools, can express membrane enzymes (e.g., P450s). | Potential hyperglycosylation, lower diversity of native secondary metabolites. | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris |

| Filamentous Fungi | High secretion capacity, native ability to produce diverse secondary metabolites. | Complex genetics, abundant native metabolic pathways that compete for precursors. | Aspergillus spp. |

| Plants/Plant Cell Cultures | Suitable for complex plant natural products, self-sufficient, compartmentalization. | Slow growth, complex transformation protocols, low product yields. | Nicotiana benthamiana |

Quantitative Analysis of Bioproduction

The effectiveness of metabolic engineering is measured quantitatively. The table below summarizes reported production metrics for various chemicals in different engineered hosts, demonstrating the success of these strategies.

Table 2: Production Metrics for Selected Chemicals in Engineered Hosts [2]

| Chemical | Host | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Key Metabolic Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactic Acid | C. glutamicum | 264 | 0.95 | - | Modular pathway engineering |

| Lysine | C. glutamicum | 223.4 | 0.68 | - | Cofactor engineering, Transporter engineering, Promoter engineering |

| 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid | C. glutamicum | 62.6 | 0.51 | - | Substrate engineering, Genome editing |

| Muconic Acid | C. glutamicum | 54 | 0.197 | 0.34 | Modular pathway engineering, Chassis engineering |

| Succinic Acid | E. coli | 153.36 | - | 2.13 | Modular pathway engineering, High-throughput genome engineering |

| Butanol | Clostridium spp. | - | ~3-fold increase* | - | Modular pathway engineering, Genome editing |

*Yield reported as a fold-increase.

Experimental Protocol: Pathway Assembly and Optimization in Yeast

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for the construction and initial optimization of a heterologous pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a commonly used eukaryotic host.

Materials and Equipment

- Strains and Vectors: E. coli DH5α for plasmid propagation; S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., CEN.PK2) as the host; yeast shuttle vector (e.g., a centromeric plasmid with a selectable marker like URA3).

- Enzymes and Kits: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, restriction enzymes, DNA ligase, Gibson Assembly master mix, yeast transformation kit, plasmid miniprep kit, gel extraction kit.

- Culture Media: LB broth with appropriate antibiotics; Yeast synthetic complete (SC) dropout media for selection and cultivation.

- Equipment: Thermocycler, incubator shakers, spectrophotometer, centrifuge, electrophoresis apparatus, HPLC system for product analysis.

Procedure

Part 1: In Vitro Vector Construction

- Gene Codon Optimization and Synthesis: Optimize the coding sequences of the heterologous genes for expression in S. cerevisiae and obtain them via gene synthesis.

- Plasmid Linearization: Digest the yeast expression vector with restriction enzymes at the chosen cloning site(s). Purify the linearized vector via gel electrophoresis and extraction.

- Pathway Assembly: Assemble the heterologous genes into the linearized vector. For pathways with multiple genes, use methods such as:

- Restriction/Ligation: Clone genes sequentially using compatible restriction sites.

- Gibson Assembly: Assemble multiple DNA fragments with overlapping ends in a single, isothermal reaction.

- Transformation into E. coli: Transform the assembled plasmid into competent E. coli cells and plate on selective LB agar. Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Plasmid Verification: Pick several colonies, culture them, and isolate plasmid DNA. Verify the correct assembly of the pathway via analytical restriction digest and Sanger sequencing.

Part 2: In Vivo Implementation and Analysis in Yeast

- Yeast Transformation: Transform the verified plasmid into competent S. cerevisiae cells using a standard protocol (e.g., lithium acetate method). Plate the transformed cells on SC dropout agar plates to select for transformants. Incubate for 2-3 days at 30°C.

- Initial Screening of Transformants: Pick 10-20 individual colonies and inoculate them into 5 mL of SC dropout liquid medium. Grow the cultures for 48-72 hours at 30°C with shaking.

- Analytical Sampling:

- Harvest 1 mL of culture and centrifuge to separate cells from supernatant.

- Analyze the supernatant for the presence of the target product using HPLC or GC-MS. Compare against standards.

- Measure optical density (OD600) to correlate production with cell growth.

- Fed-Batch Fermentation (Bench-Scale): Inoculate the best-performing transformant into a bioreactor containing a defined production medium. Control parameters such as pH, dissolved oxygen, and temperature. Employ a fed-batch strategy by feeding a carbon source (e.g., glucose) to maintain it at a low level, preventing overflow metabolism and maximizing product formation.

- Quantitative Analysis: Periodically sample the fermentation broth. Measure substrate consumption, cell density, and product titer. Calculate the final yield (YP, g product/g substrate) and productivity (g/L/h).

Troubleshooting

- No Product Detected: Verify gene expression via RT-qPCR or western blot. Check enzyme activity in vitro. Ensure the host provides necessary precursors and cofactors.

- Low Titer: Investigate potential metabolic bottlenecks. Consider re-engineering the pathway by swapping enzyme homologs, modulating gene expression levels with different promoters, or engineering the host's central metabolism to enhance precursor supply [1] [5].

- Strain Instability: Ensure continuous selective pressure. If using multi-copy plasmids, consider integrating the pathway into the host genome for long-term stability.

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Computational tools are indispensable for the rational design of heterologous pathways. The integration of models and algorithms helps transition metabolic engineering from a trial-and-error approach to a predictive science [4] [5]. The following diagram illustrates a modern, iterative cycle for computational pathway design and optimization.

Key computational strategies include:

- Pathway Prediction: Algorithms like retrosynthetic biosynthesis generate all possible pathways linking a host metabolite to a desired target product [1].

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): This constraint-based modeling technique uses GEMs to predict metabolic flux distributions, enabling the identification of gene knockout or overexpression targets to maximize product yield [4] [5].

- Quantitative Heterologous Pathway Design (QHEPath): Advanced algorithms can evaluate thousands of biosynthetic scenarios to identify heterologous reactions that break the stoichiometric yield limit of the native host network. These methods have revealed over a dozen common engineering strategies effective for enhancing yield for hundreds of products [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents, materials, and tools essential for research in heterologous pathway engineering.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids for gene expression in various hosts (e.g., pET series for E. coli, pRS series for S. cerevisiae). Contain promoters, selectable markers, and origins of replication. |

| Codon-Optimized Genes | Synthetic genes where the codon usage is optimized for the heterologous host to maximize translation efficiency and protein expression levels. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | An enzyme mix for seamless, single-reaction assembly of multiple overlapping DNA fragments, crucial for pathway construction. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | For precise genome editing in the host organism, enabling gene knockouts, knock-ins, and transcriptional regulation [2] [3]. |

| HPLC/GC-MS Systems | High-performance liquid chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for accurate quantification and identification of metabolic products and intermediates. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models (e.g., for E. coli, S. cerevisiae) used to simulate metabolism, predict fluxes, and identify metabolic engineering targets in silico [4] [5]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., GFP) | Used to monitor gene expression dynamics and promoter strength in real-time within living cells. |

| 4-(4-Bromophenyl)-2-methyl-1-butene | 4-(4-Bromophenyl)-2-methyl-1-butene, CAS:138624-01-8, MF:C11H13Br, MW:225.12 g/mol |

| 2-(4-Pentynyloxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran | 2-(4-Pentynyloxy)tetrahydro-2H-pyran, CAS:62992-46-5, MF:C10H16O2, MW:168.23 g/mol |

The incorporation of heterologous metabolic pathways into host organisms is a cornerstone of modern metabolic engineering, enabling the production of valuable secondary metabolites. This process involves introducing a series of foreign genes into a host organism to create new biochemical capabilities or enhance existing ones. Successful pathway incorporation requires a meticulous, multi-stage approach that begins with the isolation of relevant genes and culminates in the optimization of the host organism for maximum metabolite production. The fundamental goal is to reconstruct functional biosynthetic pathways from donor organisms into production-friendly host systems that lack these native capabilities.

This protocol outlines a comprehensive framework for researchers embarking on metabolic pathway engineering projects. The strategies presented are particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to engineer microbial factories for pharmaceutical compounds, including antibiotics, anti-cancer agents, and other therapeutic molecules. The process demands careful planning at each stage, as simple introduction of pathway genes into a heterologous host often fails to yield successful expression without extensive optimization at multiple levels. The following sections provide detailed methodologies for navigating this complex process from inception to optimized production [1].

Key Experimental Workflow: From Genes to Functional Pathways

The journey from gene identification to a functioning heterologous pathway follows a logical sequence of interdependent steps. Each stage builds upon the previous one, with optimization being iterative throughout the process. The overall workflow can be visualized as follows:

Gene Isolation Strategies

The initial stage involves identifying and isolating genes encoding the enzymes required for your target metabolic pathway. Several molecular biology approaches can be employed depending on the source organism and available genomic information.

Protocol: Functional Screening for Gene Isolation

Purpose: To identify target genes through functional expression screening when sequence information is limited.

Materials:

- Genomic DNA from source organism

- Suitable expression vector (e.g., plasmid with strong promoter)

- Competent cells of screening host (typically E. coli)

- Selective growth media

- Substrates for enzymatic activity detection

- Standard molecular biology reagents (restriction enzymes, ligase, PCR reagents)

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Partially digest genomic DNA from the source organism with a restriction enzyme (e.g., Sau3AI) that generates compatible ends for your chosen vector. Ligate fragments into an expression vector and transform into competent E. coli cells to create a genomic library [6].

- Plating and Screening: Plate transformed cells on selective media and incubate until colonies form. Replica plate colonies to fresh media containing specific substrates that enable detection of desired enzymatic activity.

- Activity Detection: Employ appropriate detection methods based on expected enzyme function:

- For hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., cellulases), use substrate-containing agar plates with subsequent staining methods to identify clearing zones around active colonies [7].

- For oxidoreductases, incorporate colorimetric substrates that generate visible products upon enzymatic conversion.

- For metabolic pathway enzymes, use auxotrophic complementation or chemical detection methods.

- Sequence Analysis: Isolate plasmids from positive clones and sequence inserted DNA fragments. Compare resulting sequences to public databases to identify gene function.

Protocol: PCR-Based Gene Isolation

Purpose: To amplify specific target genes when sequence information is available.

Materials:

- Source genomic DNA or cDNA

- Sequence-specific primers

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase

- Gel electrophoresis equipment

- DNA purification kits

Methodology:

- Primer Design: Design primers based on known sequences of target genes. Include appropriate restriction sites at the 5' ends to facilitate subsequent cloning.

- Amplification: Set up PCR reactions with high-fidelity polymerase to minimize mutation introduction. Use touchdown or gradient PCR if melting temperature is uncertain.

- Product Verification: Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. Excise bands of expected size and purify using gel extraction kits.

- Sequence Verification: Clone purified PCR products into sequencing vectors or sequence directly after purification. Verify sequence fidelity compared to reference sequences.

Vector Design and Assembly

Once individual genes are isolated, they must be assembled into appropriate expression vectors for introduction into the host organism.

Research Reagent Solutions for Vector Assembly

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | Enable Golden Gate assembly by creating unique overhangs | Allows seamless assembly of multiple genetic parts; examples: BsaI, BsmBI |

| DNA Assembly Master Mixes | All-in-one reagents for recombination-based cloning | Simplify assembly of multiple fragments; examples: Gibson Assembly, In-Fusion |

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors | Replicate in multiple microbial species | Essential for testing pathways in different hosts; examples: pBBR1, RSF1010 origins |

| Inducible Promoters | Regulate timing and level of gene expression | Critical for expressing toxic genes; examples: PAOX1 (methanol-inducible), PTET (tetracycline-inducible) [1] |

| Modular Vector Systems | Standardized genetic parts for rapid testing | Facilitate combinatorial testing of pathway variants; examples: MoClo, GoldenBraid |

Protocol: Modular Vector Assembly for Pathway Construction

Purpose: To assemble multiple genes into coordinated expression systems using standardized parts.

Materials:

- Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI)

- T4 DNA ligase

- Purified individual gene modules

- Modular acceptor vectors

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- DNA purification kits

Methodology:

- Module Preparation: Clone each pathway gene into appropriate modular position vectors with standardized prefix and suffix sequences.

- Single-Pot Assembly Reaction: Set up a Golden Gate assembly reaction containing:

- 50-100 ng of each gene module

- 1× T4 DNA ligase buffer

- 0.5-1 μL BsaI-HFv2 restriction enzyme

- 200-400 units T4 DNA ligase

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL total volume

- Thermocycling: Run the following program:

- 37°C for 5 minutes (restriction)

- 16°C for 5 minutes (ligation)

- Repeat steps 1-2 for 25-50 cycles

- 50°C for 5 minutes (final digestion)

- 80°C for 10 minutes (enzyme inactivation)

- Transformation and Verification: Transform 2-5 μL of assembly reaction into competent E. coli cells. Screen colonies by colony PCR and restriction digest to verify correct assembly.

- Pathway Validation: Sequence final constructs to confirm integrity of the assembled pathway.

Host Selection and Transformation

Choosing an appropriate host organism is critical for successful pathway incorporation, as different hosts offer distinct advantages and limitations.

Comparative Analysis of Host Organisms

| Host Organism | Advantages | Limitations | Common Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Fast growth, low-cost media, high protein yields, extensive genetic tools | Limited post-translational modifications, often unsuitable for complex eukaryotic pathways | E. coli, B. subtilis |

| Yeast | Eukaryotic protein processing, generally recognized as safe (GRAS), moderate growth, good genetic tools | Hyperglycosylation potential, limited native secondary metabolites | S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris [1] |

| Filamentous Fungi | Robust secondary metabolism, efficient protein secretion, diverse native metabolites | Complex genetics, slower growth, potential allergenicity | Aspergillus spp., N. crassa [1] |

| Plants | Appropriate for plant-derived pathways, compartmentalization, whole-organism or cell culture options | Slow growth, complex transformation, low protein yields | N. benthamiana, A. thaliana [1] |

Protocol: Host Transformation and Screening

Purpose: To introduce assembled pathway constructs into selected host organisms and identify successful transformants.

Materials:

- Competent cells of chosen host organism

- Assembled pathway vector DNA

- Selective media appropriate for host

- Electroporator or transformation equipment

- Incubation equipment suitable for host organism

Methodology: For Bacterial Transformation (E. coli):

- Preparation: Thaw competent cells on ice. Aliquot 50 μL cells per transformation.

- DNA Addition: Add 1-100 ng plasmid DNA to cells. Mix gently by tapping.

- Incubation: Incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

- Heat Shock: Heat at 42°C for exactly 30 seconds, then return to ice for 2 minutes.

- Recovery: Add 950 μL recovery media and incubate at 37°C with shaking for 1 hour.

- Selection: Plate appropriate dilutions on selective media and incubate overnight.

For Yeast Transformation (S. cerevisiae):

- Culture Preparation: Grow yeast to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.5-1.0).

- Harvesting: Pellet cells and wash with sterile water, then with 1× TE/LiAc buffer.

- Incubation: Resuspend cells in 1× TE/LiAc. Add carrier DNA (denatured salmon sperm DNA) and plasmid DNA. Mix and incubate at 30°C for 30 minutes.

- PEG Treatment: Add PEG/LiAc solution, mix, and incubate at 30°C for 45 minutes.

- Heat Shock: Heat at 42°C for 15-25 minutes.

- Selection: Plate on selective media and incubate at 30°C for 2-3 days.

Screening and Validation:

- Colony PCR: Pick individual colonies and use colony PCR to verify presence of pathway genes.

- Analytical Confirmation: For verified transformants, conduct:

- Restriction analysis of isolated plasmids

- RT-PCR to confirm gene expression

- Metabolite profiling (HPLC, LC-MS) to detect pathway products

Pathway Validation and Optimization

After successful transformation, thorough validation and optimization are essential to achieve high-level metabolite production.

Analytical Framework for Pathway Validation

The validation process requires multiple analytical approaches to confirm proper integration, expression, and functionality of the incorporated pathway:

Protocol: Computational Pathway Analysis and Topology Assessment

Purpose: To evaluate the functional incorporation of heterologous pathways using topology-based analysis methods.

Materials:

- Gene expression data from transformed host

- Pathway topology databases (KEGG, Reactome, WikiPathways)

- Statistical analysis software (R, Python with specialized packages)

- Pathway analysis tools (SPIA, PRS, CePa, TopologyGSA) [8]

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Extract RNA and perform RNA-seq or microarray analysis on your transformed host under production conditions. Process raw data to obtain normalized gene expression values.

- Database Selection: Select appropriate pathway databases for your analysis. Consider using integrative resources like MPath that combine information from multiple databases to reduce bias and improve biological relevance [9].

- Topology-Based Analysis: Apply topology-based pathway analysis methods that consider both expression values and pathway structure, as these outperform simple enrichment methods:

- SPIA: Identifies pathways with significant expression changes considering their topology

- CePa: Incorporates pathway topology with central node emphasis

- TopologyGSA: Uses linear models to assess pathway significance

- Result Interpretation: Identify pathways showing significant alterations in your transformed host. Focus on:

- Expected pathway activation based on introduced genes

- Unintended impacts on native host metabolism

- Compensatory mechanisms or stress responses

- Experimental Validation: Use the computational results to guide targeted metabolic engineering interventions, such as:

- Downregulating competing pathways

- Enhancing precursor supply

- Alleviating bottlenecks identified through flux analysis

Host Optimization Strategies

After initial pathway validation, systematic optimization is required to maximize product yields and host fitness.

Key Optimization Parameters and Methods

| Optimization Dimension | Strategies | Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression | Promoter engineering, RBS optimization, codon optimization, transcriptional tuning | qRT-PCR, ribosome profiling, proteomics, reporter assays |

| Metabolic Burden | Pathway segmentation, genomic integration, copy number control | Growth rate analysis, ATP/NAD(P)H monitoring, transcriptomics |

| Cofactor Balance | Cofactor engineering, transhydrogenase expression, NAD(P)H regeneration systems | Cofactor ratio measurements, metabolic flux analysis |

| Precursor Supply | Upregulation of precursor pathways, knockdown of competing pathways | Metabolite profiling, isotopic tracer studies, flux balance analysis |

| Product Transport | Export engineering, membrane modification, sequestration strategies | Extracellular vs. intracellular product measurements |

Protocol: Iterative Model-Guided Optimization

Purpose: To systematically improve pathway performance using computational modeling and targeted interventions.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model of host organism

- Flux balance analysis software (e.g., COBRA Toolbox)

- CRISPR-based genome editing tools

- Analytical equipment for metabolite quantification (HPLC, GC-MS, LC-MS)

Methodology:

- Model Construction: Obtain or reconstruct a genome-scale metabolic model for your host organism. Integrate the heterologous pathway into this model.

- Flux Balance Analysis: Perform constraint-based modeling to:

- Identify rate-limiting steps in the pathway

- Predict gene knockout/overexpression targets

- Simulate cofactor balancing strategies

- Implementation Cycle: a. Design: Based on modeling results, design genetic modifications to overcome predicted limitations. b. Build: Implement modifications using appropriate genetic tools (CRISPR, multiplex automated genome engineering). c. Test: Cultivate engineered strains in controlled bioreactors and measure key performance indicators (titer, rate, yield). d. Learn: Analyze resulting data to refine model parameters and generate new hypotheses.

- Multi-omic Integration: Incorporate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to create condition-specific models that more accurately predict metabolic behavior.

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution: Subject optimized strains to prolonged cultivation under selective pressure to identify beneficial mutations that further enhance performance.

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Even with careful execution, pathway incorporation projects often encounter challenges that require systematic troubleshooting.

Common Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No Product Detection | Gene silencing, incorrect folding, lack of cofactors | Verify transcription, test different promoters, add chaperones, supplement cofactors |

| Low Yields | Metabolic burden, toxicity, precursor limitation | Titrate expression, implement inducible systems, enhance precursor supply |

| Host Growth Impairment | Resource competition, product toxicity, metabolic imbalance | Separate growth and production phases, engineer export systems, implement dynamic regulation |

| Unstable Production | Genetic instability, plasmid loss, mutation | Use genomic integration, implement selection pressure, reduce repetitive elements |

| Byproduct Accumulation | Pathway bottlenecks, enzyme promiscuity, side reactions | Balance expression levels, engineer enzyme specificity, knockout competing reactions |

Protocol: Comprehensive Pathway Activity Assessment

Purpose: To systematically identify limitations in incorporated pathways through multi-level analysis.

Materials:

- RNA extraction kit

- Protein extraction reagents

- Enzyme activity assay components

- Metabolite extraction solvents

- Analytical standards for target metabolites and intermediates

Methodology:

- Transcript Level Analysis:

- Extract RNA from production cultures at multiple time points

- Perform qRT-PCR for all pathway genes using reference gene for normalization

- Calculate relative expression levels to identify poorly expressed genes

Protein Level Analysis:

- Prepare protein extracts from the same cultures

- Perform Western blotting for tagged pathway enzymes or use targeted proteomics

- Compare protein levels to identify potential translation or stability issues

Enzyme Activity Assays:

- Measure in vitro enzyme activities for each pathway step

- Use saturating substrate conditions to determine Vmax values

- Compare activities to identify potential kinetic bottlenecks

Metabolite Profiling:

- Extract intracellular metabolites at multiple time points

- Quantify pathway intermediates and end products using LC-MS or GC-MS

- Identify accumulating intermediates that indicate pathway bottlenecks

Data Integration:

- Correlate transcript, protein, activity, and metabolite data

- Identify the most significant limitations to target for further optimization

- Prioritize engineering interventions based on integrated data

By following these comprehensive protocols and utilizing the provided troubleshooting guide, researchers can systematically advance from gene isolation to optimized pathway incorporation, creating robust microbial factories for valuable biochemical production. The iterative nature of this process requires patience and careful analytical work, but can yield significant rewards in terms of production efficiency and metabolic capabilities.

The selection of an appropriate host organism is a critical determinant of success in metabolic engineering and biotechnology. This application note provides a structured comparison of four major host systems—bacteria, yeast, fungi, and mammalian cells—specifically framed within enzyme manipulation strategies for pathway optimization research. We present quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols for key analyses, and essential workflow visualizations to guide researchers in selecting and engineering optimal host platforms for biocatalyst development and metabolic flux optimization. The systematic comparison of these hosts enables more informed decisions in constructing efficient cellular factories for producing therapeutics, enzymes, and other valuable biochemicals.

Host Organism Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each host organism relevant to enzyme manipulation and pathway engineering applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Host Organisms for Enzyme Manipulation and Pathway Optimization

| Characteristic | Bacteria (E. coli) | Yeast (S. cerevisiae) | Fungi (Filamentous) | Mammalian Cells (CHO, HEK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred Applications | Non-glycosylated proteins, peptides, antibiotics, organic acids [10] | Ethanol, pharmaceuticals, recombinant proteins, glycol-engineered products [11] [10] | Industrial enzymes (hydrolytic), secondary metabolites, organic acids [10] | Complex glycosylated proteins, monoclonal antibodies, viral vaccines [10] |

| Typical Yields | High (∼g/L) for simple proteins [10] | High for ethanol, variable for proteins [11] | Very high for secreted enzymes [10] | Lower (∼mg/L to g/L) but increasing with process optimization [10] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Limited, no glycosylation [10] | Core eukaryotic glycosylation (high-mannose) [10] | Eukaryotic glycosylation [10] | Complex human-like glycosylation [10] |

| Growth Rate | Very fast (doubling time: 20-60 min) [10] | Fast (doubling time: 1.5-2 hours) [10] | Moderate to fast [10] | Slow (doubling time: 24-48 hours) [10] |

| Cost & Complexity | Low cost, simple media [10] | Moderate cost [10] | Moderate to low cost [10] | High cost, complex media [10] |

| Enzyme Engineering Compatibility | Excellent for in vivo directed evolution [12] | Excellent for eukaryotic enzyme evolution [13] | Good for secretory pathway engineering | Limited for in vivo evolution, requires specialized systems [12] |

| Pathway Optimization Tools | Extensive (CRISPR, MAGE, FACS) [12] | Well-developed (CRISPR, homologous recombination) [11] | Developing genetic tools [10] | Limited but improving (CRISPR, transposons) [12] |

| Key Advantages | Rapid growth, well-characterized genetics, high transformation efficiency [10] [12] | GRAS status, eukaryotic processing, stress tolerance [10] | High secretion capacity, diverse metabolism [10] | Human-like processing, complex assembly, clinical relevance [10] |

| Key Limitations | Lack of eukaryotic PTMs, endotoxin concerns [10] | Hyperglycosylation, smaller toolkit than E. coli [10] | Complex genetics, slower engineering cycles [10] | High cost, slow growth, complex media requirements [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: GC-MS Based Metabolic Flux Analysis for Pathway Optimization

Application: Quantifying in vivo carbon fluxes in engineered pathways across all host organisms [14].

Principle: Utilizing 13C-labeled substrates and GC-MS to measure labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites, enabling calculation of metabolic flux distributions [14].

Procedure:

- Tracer Experiment: Cultivate engineered host organism in defined medium with specifically 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1-13C]glucose). Maintain exponential growth until mid-log phase [14].

- Metabolite Extraction: Rapidly harvest cells (quenching in -40°C methanol). Extract intracellular metabolites using cold methanol/water/chloroform system. Derivatize polar metabolites (e.g., amino acids, organic acids) for GC-MS analysis using N-methyl-N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA) or similar reagents [14].

- GC-MS Analysis:

- Column: DB-35ms or equivalent (30m length, 0.25mm diameter)

- Carrier Gas: Helium, constant flow (1.0 mL/min)

- Temperature Program: 80°C to 320°C with controlled ramping

- Ionization: Electron impact (70 eV)

- Data Acquisition: Selected ion monitoring (SIM) for target mass isotopomers [14]

- Data Processing: Calculate mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) from corrected ion cluster intensities. Determine summed fractional labeling (SFL) using formula: SFL = Σ(i·x{m+i}) where i is number of labeled carbons and x{m+i} is fractional abundance of mass isotopomer M+i [14].

- Flux Calculation: Implement computational flux model combining isotopomer balancing with extracellular flux measurements. Use iterative optimization algorithm to minimize difference between simulated and experimental labeling data [14].

Notes: For mammalian cells, adapt quenching protocol to maintain membrane integrity. For fungi, may require extended derivatization times due to cell wall complexity.

Protocol: Flow Cytometry-Based Adhesion Assay for Microbial Interactions

Application: Quantitative measurement of microbial adhesion relevant to consortium-based pathway optimization [15].

Principle: Detecting fluorescently labeled bacteria adhering to yeast or fungal cells at single-cell level using flow cytometry, enabling quantification of interaction dynamics [15].

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation:

- Engineer bacteria to express fluorescent protein (e.g., Dendra2, GFP)

- Cultivate fluorescent bacteria and target yeast/fungal cells to mid-log phase

- Wash and resuspend in PBS buffer to appropriate densities (∼10^8 cells/mL yeast, ∼10^9 cells/mL bacteria) [15]

- Adhesion Assay:

- Mix bacterial and yeast suspensions in 1:10 ratio (yeast:bacteria)

- Incubate at 37°C for 90 minutes with gentle rotation

- Wash twice with PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria [15]

- Flow Cytometry Analysis:

- Instrument: Standard flow cytometer with 488nm laser and 530/30nm filter

- Gating Strategy: Identify yeast singlets using FSC-A vs FSC-H, then detect fluorescent population

- Acquisition: Record ≥10,000 events in yeast gate

- Analysis: Calculate Adhesion Index (Ai) = (Fluorescent yeast count / Total yeast count) × 100 [15]

- Imaging Flow Cytometry (Optional): Use imaging flow cytometry to quantify number of bacteria attached per yeast cell and verify single-cell interactions [15].

Notes: Critical to include controls for autofluorescence and non-specific aggregation. Sonication may be necessary for fungal strains prone to clumping.

Protocol: FuncLib-Based Active Site Engineering for Enzyme Optimization

Application: Computational design of multipoint mutations at enzyme active sites to enhance catalytic properties across all host systems [13].

Principle: Using phylogenetic analysis and Rosetta design calculations to create stable, diverse active site variants that can be expressed in suitable hosts [13].

Procedure:

- Active Site Selection:

- Identify 5-10 first-shell active site residues based on crystal structure or AlphaFold2 model

- Exclude residues directly involved in catalytic mechanism or metal coordination [13]

- Sequence Space Definition:

- Generate multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of homologous enzymes

- Filter mutations to those with reasonable phylogenetic frequency (>1% in MSA)

- Exclude mutations predicted to significantly destabilize structure (ΔΔG > 3 kcal/mol) [13]

- Multipoint Mutant Design:

- Use Rosetta to model all combinations of 3-5 mutations from filtered set

- Perform backbone and sidechain minimization for each design

- Rank designs by predicted stability [13]

- Diversity Selection:

- Cluster top-ranking designs by structural similarity

- Select representatives from each cluster differing by ≥2 mutations

- Prioritize 20-50 designs for experimental testing [13]

- Experimental Validation:

Notes: Protocol benefits from starting with stability-enhanced enzyme variant (e.g., PROSS-designed). Web server available: http://FuncLib.weizmann.ac.il.

Workflow Visualizations

Metabolic Flux Analysis Workflow

Figure 1: GC-MS Metabolic Flux Analysis Workflow

Automated Enzyme Engineering Pipeline

Figure 2: Automated Enzyme Engineering Pipeline

Host Selection Decision Pathway

Figure 3: Host Selection Decision Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Manipulation and Pathway Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Host Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates ([1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine) | Metabolic flux analysis using GC-MS; enables quantification of intracellular reaction rates [14] | All hosts (Bacteria, Yeast, Fungi, Mammalian) |

| MTBSTFA Derivatization Reagent | Silanizing agent for GC-MS analysis of polar metabolites; enables detection of amino acids, organic acids [14] | All hosts (extraction method varies) |

| Fluorescent Proteins (Dendra2, GFP) | Tagging for expression analysis, protein localization, and interaction studies (e.g., adhesion assays) [15] | All hosts (codon optimization required) |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Protein design and structural modeling; enables active site engineering and stability enhancements [13] [12] | All hosts (in silico design) |

| Hypermutation Systems (e.g., MutaT7) | In vivo continuous evolution; increases mutation rates in target genes for directed evolution [12] | Primarily Bacteria and Yeast |

| Specialized Media Formulations | Defined media for isotopic labeling; optimized media for specific host requirements and selection [10] [14] | All hosts (composition varies) |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Genome editing for gene knockouts, knockins, and regulatory element engineering [12] | All hosts (delivery method varies) |

| Single-Use Bioreactors | Scale-up and process optimization; enables controlled parameter maintenance during cultivation [10] | All hosts (configuration varies) |

The Critical Role of Metabolic Balances and Cofactor Availability in the Host

In the field of metabolic engineering, achieving optimal production of target compounds requires more than just introducing heterologous pathways; it demands a fundamental understanding and precise manipulation of the host's internal metabolic balances. Cofactors such as NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+, ATP/ADP, and acetyl-CoA serve as the central currency of cellular metabolism, regulating redox equilibrium, energy transfer, and carbon flux [16]. The availability and balance of these cofactors directly influence the efficiency of biocatalysts, ultimately determining the success of microbial cell factories in producing valuable chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and biofuels [17] [16]. This application note details the critical importance of cofactor management and provides established methodologies for quantifying and engineering cofactor balances to optimize metabolic pathways.

Quantitative Impact of Cofactor Availability

Key Cofactors and Their Metabolic Functions

Table 1: Primary Cofactors in Microbial Metabolism and Their Physiological Roles

| Cofactor | Primary Functions | Key Metabolic Pathways | Impact of Imbalance |

|---|---|---|---|

| NADH/NAD+ | Electron carrier, redox balance [16] | Glycolysis, TCA cycle, aerobic respiration [18] | Shift to fermentative metabolism, reduced growth [18] |

| NADPH/NADP+ | Reductive biosynthesis, oxidative stress response [16] | Fatty acid synthesis, oxidative PPP [19] | Limited production of reduced compounds [20] |

| ATP/ADP | Energy transfer, metabolic regulation [16] | Substrate-level/oxidative phosphorylation [16] | Inhibited TCA cycle, altered glycolytic rate [16] |

| Acetyl-CoA | Central carbon metabolite, precursor [16] | TCA cycle, fatty acid & isoprenoid synthesis [16] | Accumulation of acetic acid, reduced growth [16] |

Quantitative Evidence of Cofactor Manipulation

Engineering cofactor supply has demonstrated significant, quantifiable improvements in metabolic outcomes. A seminal study overexpressing an NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase (FDH) from Candida boidinii in Escherichia coli doubled the maximum yield of NADH from 2 to 4 mol per mol of glucose consumed [18]. This genetic intervention provoked a major metabolic shift:

- Under Anaerobic Conditions: A dramatic increase in the ethanol-to-acetate ratio was observed, favoring the production of more reduced metabolites [18].

- Under Aerobic Conditions: The increased NADH availability induced a shift to fermentative metabolism, stimulating pathways that are normally inactive in the presence of oxygen [18].

Table 2: Cofactor Engineering Strategies and Documented Outcomes

| Engineering Strategy | Host Organism | Key Intervention | Quantitative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| NADH Regeneration | E. coli | Overexpression of NAD+-dependent FDH [18] | NADH yield from glucose: 2 → 4 mol/mol [18] |

| Acetyl-CoA Boost | E. coli | Overexpression of acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS) [16] | Reduced acetate accumulation, enhanced product flux [16] |

| In silico Pathway Balancing | E. coli (in silico) | Cofactor Balance Assessment (CBA) algorithm [20] | Identification of high-yield, balanced n-butanol pathways [20] |

| Metabolic Node Remodeling | Pseudomonas putida | Native TCA cycle flux remodeling on phenolic acids [19] | 50-60% NADPH yield; up to 6x greater ATP surplus vs. succinate [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Cofactor Balance Assessment (CBA) Using Constraint-Based Modeling

This protocol uses computational modeling to predict cofactor demands and imbalances when designing synthetic pathways, helping researchers select optimal strains and pathways before laboratory implementation [20].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Software Tools: OptFlux, COBRA Toolbox, or similar constraint-based modeling platform [20] [21].

- Stoichiometric Model: A genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) of the host organism (e.g., E. coli Core Model) [20] [17].

- Pathway Stoichiometry: A defined list of mass- and charge-balanced reactions for the synthetic pathway of interest, including cofactors [20].

II. Procedure

- Model Construction and Modification:

- Load the host organism's GEM into the modeling software.

- Add the heterologous production pathway as a set of new metabolic reactions to the model. Ensure all cofactors (e.g., NADH, NADPH, ATP) are correctly specified in the reaction equations [20].

- Simulation Setup:

- Set constraints to reflect experimental conditions (e.g., carbon source uptake rate, oxygen availability).

- Define the objective function, typically the maximization of the target product exchange flux [20].

- Flux Analysis:

- Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to obtain a flux distribution that maximizes the objective.

- Execute Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to determine the feasible range of each reaction flux under the optimal growth or production state [20].

- Cofactor Balance Calculation:

- Extract the flux values for reactions producing and consuming key cofactors (ATP, NADH, NADPH).

- Calculate the net balance for each cofactor (total production - total consumption) within the engineered pathway and the entire network. A non-zero net balance indicates an imbalance [20].

- Identification of Futile Cycles:

- Inspect the flux solution for high-flux cycles that simultaneously produce and consume a cofactor (e.g., simultaneous ATP synthesis and hydrolysis) without net metabolic benefit. These can dissipate energy and reduce yield [20].

III. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Pathways with a net zero cofactor balance (or a slight negative ATP balance) often present the highest theoretical yield, as they are thermodynamically more feasible and minimize carbon diversion to byproducts [20].

- Use the CBA output to compare different pathway variants for the same product and select the one with the most favorable cofactor demand profile [20].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this protocol:

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Cofactor-Driven Metabolic Shifts

This protocol outlines how to genetically manipulate cofactor availability and measure the subsequent changes in extracellular metabolites and growth, validating computational predictions [18].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Strains: Wild-type host (e.g., E. coli) and an engineered strain with a cofactor-regeneration enzyme (e.g., plasmid containing NAD+-dependent FDH gene from C. boidinii) [18].

- Growth Media: Defined minimal media with a controlled carbon source (e.g., glucose).

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC or GC-MS system for quantifying metabolites (e.g., organic acids, alcohols); spectrophotometer or bioreactor for measuring cell density (OD600).

II. Procedure

- Strain Cultivation:

- Inoculate wild-type and engineered strains in triplicate in defined medium.

- Grow cultures under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C for E. coli) [18].

- Sampling:

- Take periodic samples throughout the fermentation (exponential and stationary phases).

- For each sample, measure the optical density (OD600) and then centrifuge to separate cells from supernatant.

- Metabolite Analysis:

- Analyze the cell-free supernatant using HPLC or GC-MS to quantify the concentrations of key metabolites: glucose, acetate, ethanol, formate, lactate, and others relevant to the host's metabolism [18].

- Data Calculation:

- Calculate consumption (glucose) and production (all other metabolites) rates.

- Determine molar yields of products relative to the substrate consumed.

III. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Compare the metabolite profile and product ratios (e.g., ethanol/acetate) between the wild-type and engineered strain.

- A successful increase in NADH availability, for instance, should lead to a higher proportion of reduced products (e.g., ethanol) over oxidized ones (e.g., acetate), especially under anaerobic conditions [18].

- Under aerobic conditions, observe if there is a metabolic shift towards fermentation, indicated by the production of mixed-acid fermentation products despite the presence of oxygen [18].

The experimental workflow for validating cofactor-driven metabolic shifts is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Cofactor Metabolism Studies

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Specific Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Computational Tool | In silico representation of metabolic network [17] | Predicting flux distributions and cofactor demands [20] [17] |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Computational Algorithm | Calculates flow of metabolites through a metabolic network [20] | Maximizing target product synthesis in silico [20] |

| NAD+-dependent Formate Dehydrogenase | Enzyme / Genetic Part | Regenerates NADH from NAD+ and formate [18] | Increasing intracellular NADH availability in E. coli [18] |

| Acetyl-CoA Synthase (ACS) | Enzyme / Genetic Part | Converts acetate to acetyl-CoA [16] | Reducing acetate excretion, boosting acetyl-CoA supply [16] |

| HPLC / GC-MS | Analytical Equipment | Separation and quantification of metabolites [22] [21] | Validating computational models by measuring extracellular fluxes [21] |

| Cofactor Balance Assessment (CBA) | Computational Protocol | Algorithm to track ATP and NAD(P)H pool changes [20] | Identifying source of cofactor imbalance in engineered pathways [20] |

| Tripentaerythritol | Tripentaerythritol, CAS:78-24-0, MF:C15H32O10, MW:372.41 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-Heptyl-1,2-oxazole | 3-Heptyl-1,2-oxazole|Research Chemical|RUO | Bench Chemicals |

Computational and Modeling Approaches for Pathway Elucidation and Host-Pathway Matching

The strategic manipulation of enzymes for pathway optimization is a cornerstone of modern bioengineering and pharmaceutical research. Success in this endeavor hinges on the ability to accurately elucidate complex biological pathways and identify optimal interactions between host systems and enzymatic processes. This article details advanced computational and modeling methodologies that address these challenges, providing application notes and structured protocols to guide researchers in leveraging these tools effectively. The integration of these approaches enables a shift from traditional, labor-intensive experimental methods to sophisticated, data-driven strategies that can predict pathway behavior, optimize enzyme expression, and identify host-targeted therapeutic strategies with greater speed and precision.

Computational Methods for Pathway Analysis

Pathway analysis provides a systems-level understanding of biological processes by moving beyond single-molecule studies to investigate interactions within networks of genes, proteins, and metabolites [23]. Several computational methodologies have been established for this purpose, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pathway Analysis Methods

| Method Type | Core Principle | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Analysis [23] | Identifies statistically overrepresented gene sets in omics data. | Simple to implement, widely applicable, fast execution. | Assumes gene independence, ignores pathway topology. | Initial screening for pathway involvement in disease or treatment response. |

| Functional Class Scoring [23] | Assigns scores based on functional relevance and aggregates to pathway-level. | Accounts for gene/protein function, detects subtle pathway perturbations. | Sensitive to scoring function parameters, requires careful tuning. | Analyzing pathways where coordinated subtle changes are significant. |

| Pathway Topology-Based [23] | Incorporates structural organization and interaction dynamics within pathways. | Models pathway regulation more realistically, identifies key regulatory nodes. | Computationally intensive, requires high-quality interaction data. | Understanding complex regulatory mechanisms and identifying critical intervention points. |

The selection of an appropriate method depends on the research question, data quality, and desired depth of analysis. Enrichment analysis offers a quick, high-level overview, while topology-based methods provide a more nuanced, mechanistic understanding of pathway dynamics [23]. These computational methods are foundational for applications ranging from disease mechanism elucidation to drug target identification and personalized medicine strategies [23].

Protocol: Conducting a Standard Overrepresentation Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps for performing a basic enrichment analysis using a hypergeometric test, one of the most common statistical methods for this purpose [23].

- Input Data Preparation: Compile a list of target genes (e.g., differentially expressed genes from an RNA-seq experiment) and a background list (e.g., all genes detected in the experiment).

- Gene Set Selection: Choose a curated pathway database (e.g., Reactome [24], KEGG) from which to extract predefined gene sets.

- Statistical Testing: For each pathway gene set, perform a hypergeometric test. This test calculates the probability that the overlap between the target gene list and the pathway gene set is due to random chance.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a correction method (e.g., Bonferroni, Benjamini-Hochberg) to the obtained p-values to control the false discovery rate (FDR).

- Results Interpretation: Pathways with a corrected p-value below a significance threshold (e.g., FDR < 0.05) are considered significantly enriched. The results can be visualized in dot plots or bar charts to show the most impacted pathways.

Modeling Approaches for Host-Pathway Matching

Matching therapeutic interventions to host-specific pathway configurations is a critical goal of precision medicine. This requires modeling frameworks that can dynamically reconstruct biological pathways and predict the effects of perturbations.

Ontology-Driven Hypothetical Assertion (OHA) Framework

The OHA framework dynamically reconstructs context-specific drug-metabolic pathways and detects potential drug interactions [25]. Its power lies in treating pathways not as static entities but as dynamic networks assembled from primitive molecular events based on the specific biological context, such as administered drugs or patient genetics [25].

The workflow begins with a Drug Interaction Ontology (DIO), a knowledge base that formally defines molecular events (e.g., enzymatic reactions, transport) and their causal relationships using a triplet view of <trigger, situator, resultant> [25]. A Pathway Object Constructor (POC) then uses this ontology to dynamically assemble relevant pathways. Subsequently, a Drug Interaction Detector (DID) identifies interactions by finding intersections between pathways generated for different drugs [25]. Finally, the framework can generate quantitative simulation models from these pathways to estimate the magnitude of interaction effects, such as changes in the pharmacokinetic parameters AUC and Cmax [25].

Protocol: Implementing an OHA-based Drug Interaction Prediction

This protocol applies the OHA framework to predict and evaluate drug-drug interactions, as demonstrated for irinotecan and ketoconazole [25].

- Knowledge Base Query: Input the drugs of interest into the system. The DIO is queried to retrieve all known molecular events associated with these drugs and their metabolites.

- Dynamic Pathway Generation: The POC assembles the retrieved molecular events into coherent, context-dependent metabolic pathways for each drug individually and for their combination.

- Interaction Detection: The DID analyzes the combined pathway to identify potential interaction points. This includes detecting shared proteins (like cytochrome CYP3A4) that may be competitively inhibited or whose expression may be altered [25].

- Numerical Simulation Setup:

- Convert the generated pathway into a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Each molecular species (e.g., drug, metabolite) becomes a variable, and each reaction is represented by a rate law.

- Parameterize the model with kinetic (e.g., Km, Vmax) and physiological (e.g., organ volumes) parameters from literature or databases.

- Simulation and Analysis: Run the simulation to predict pharmacokinetic profiles. Compare the AUC and Cmax of key metabolites (e.g., SN-38 for irinotecan) between the single-drug and multi-drug scenarios to quantify the interaction effect [25].

Pathway-Guided Molecular Design

Optimizing molecules for desired pathway-level outcomes represents a frontier in computational design. Generative molecular design models, particularly Junction Tree Variational Autoencoders (JTVAEs), have shown great promise for generating novel, valid molecular structures [26]. Their optimization is significantly enhanced by pathway-guided Latent Space Optimization (LSO).

In this approach, a JTVAE is first trained to encode molecular structures into a continuous latent space. An objective function, which can be a simple property like inhibitory constant (IC50) or a complex mechanistic pathway model, is then used to score generated molecules. Bayesian optimization navigates the latent space, searching for vectors that, when decoded, yield molecules with high scores. This process is often combined with periodic retraining, where high-scoring molecules are added to the training set, steering the model towards more optimal regions of the chemical space [26].

Protocol: Pathway-Guided Latent Space Optimization

This protocol describes how to optimize a generative model using a pathway-based objective function, such as a pharmacodynamic model for cancer therapy [26].

- Model Initialization: Train a JTVAE on a large dataset of drug-like small molecules to learn a continuous latent representation.

- Objective Function Definition: Implement a rule-based mechanistic model that can predict a therapeutic score based on a molecule's structure or its predicted protein binding. For example, a model simulating the DNA damage response pathway to assess a molecule's efficacy as a PARP1 inhibitor [26].

- Latent Space Navigation:

- Sample a population of latent vectors.

- Decode them into molecular structures.

- Score each molecule using the pathway model.

- Use a Bayesian optimizer to suggest new latent vectors likely to yield higher scores based on the collected data.

- Model Retraining (Optional): After a set number of iterations, augment the original training dataset with the high-scoring generated molecules and retrain the JTVAE. This "periodic weighted retraining" helps the model learn the features of desirable molecules and improves subsequent optimization cycles [26].

- Validation: Select top-ranked generated molecules for in vitro or in vivo testing to validate the predicted enhancement in therapeutic efficacy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the described protocols relies on a suite of computational tools, databases, and software resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Computational Pathway Analysis

| Reagent / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReactomeFIViz [24] | Software Tool (Cytoscape App) | Visualizes drug-target interactions in the context of pathways and networks. | Overlaying a drug's primary and off-targets onto a signaling pathway to hypothesize mechanisms of action or resistance. |

| STRING Database [27] | Database / Web Resource | Provides protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks with confidence scores. | Constructing a PPI network around virus-associated host targets to identify key intervention points [27]. |

| DSigDB [27] | Database | Links drugs and small molecules to their target gene sets. | Identifying potential repurposing candidates for a disease based on shared gene expression signatures. |

| PyRx [27] | Software Tool | Platform for molecular docking and virtual screening. | Evaluating binding affinities of predicted small-molecule inhibitors to prioritized host protein targets [27]. |

| JTVAE Framework [26] | Deep Learning Model | Generates novel, syntactically valid molecular structures from a continuous latent space. | De novo design of drug-like small molecules optimized for a specific pathway-level objective. |

| Drug Interaction Ontology (DIO) [25] | Computational Ontology | Formally defines molecular events and causal relationships for dynamic pathway generation. | Enabling the OHA framework to automatically reconstruct context-specific drug metabolic pathways [25]. |

| Benzyl N-ethoxycarbonyliminocarbamate | Benzyl N-ethoxycarbonyliminocarbamate, CAS:111508-33-9, MF:C11H12N2O4, MW:236.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-(Octadecylthiocarbamoylamino)fluorescein | 5-(Octadecylthiocarbamoylamino)fluorescein, CAS:65603-18-1, MF:C39H50N2O5S, MW:658.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Cutting-Edge Engineering: From Directed Evolution to Automated Platforms

Directed evolution stands as a powerful protein engineering strategy that mimics the principles of natural selection in a laboratory setting to optimize enzyme performance. This method involves iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening to accumulate beneficial mutations for a defined functional objective, such as catalytic activity, stability, or selectivity under specific conditions [28]. For researchers focused on pathway optimization, directed evolution provides a practical tool to enhance the performance of rate-limiting enzymes, thereby improving flux and yield in engineered metabolic pathways. By artificially imposing selective pressure for desired traits, scientists can rapidly evolve enzyme variants with performance characteristics that often surpass what natural evolution has produced, unlocking new possibilities in biocatalysis, therapeutic development, and sustainable biomanufacturing.

Core Methodology and Workflow

The foundational directed evolution workflow follows a cyclical Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) paradigm. In its simplest form, this involves creating genetic diversity in a parent gene, expressing the resulting variant library, screening for improved performance, and using the best variant as the template for the next cycle [28]. This process resembles a greedy hill-climbing optimization across the protein fitness landscape.

However, traditional directed evolution faces limitations when mutations exhibit non-additive, or epistatic, behavior, potentially causing experiments to become trapped at local fitness optima [29]. Advanced methodologies now integrate machine learning (ML) and active learning to navigate these complex landscapes more efficiently. These approaches leverage uncertainty quantification to balance the exploration of new sequence regions with the exploitation of variants predicted to have high fitness [29].

The following diagram illustrates the core directed evolution workflow, highlighting its iterative nature.

Advanced Application Note: Machine Learning-Guided Directed Evolution

Active Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE)

Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) represents a state-of-the-art extension of the traditional workflow. ALDE is an iterative machine learning-assisted process that uses uncertainty quantification to explore protein sequence space more efficiently than conventional methods [29]. The workflow begins with defining a combinatorial design space around k residues, resulting in 20^k possible variants. An initial library is synthesized and screened, and the collected sequence-fitness data are used to train a supervised ML model. This model then applies an acquisition function to rank all sequences in the design space, balancing the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of predicted high-fitness variants. The top-ranked variants are subsequently tested in the next wet-lab cycle [29].

Case Study: In a recent application, ALDE was used to optimize five epistatic residues in the active site of a protoglobin from Pyrobaculum arsenaticum (ParPgb) for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction. After only three rounds of experimentation, exploring a mere ~0.01% of the design space, the engineered variant achieved a product yield of 99% with high diastereoselectivity (14:1). This successful outcome would have been challenging to attain with standard directed evolution due to the strong epistatic interactions among the mutated residues [29].

AI-Powered Autonomous Platforms

Fully autonomous enzyme engineering platforms integrate machine learning, large language models (LLMs), and biofoundry automation to execute DBTL cycles with minimal human intervention. Such a platform requires only an input protein sequence and a quantifiable fitness assay [30].

A demonstration of this platform engineered two distinct enzymes:

- Arabidopsis thaliana halide methyltransferase (AtHMT): Engineered for a 90-fold improvement in substrate preference and a 16-fold improvement in ethyltransferase activity.

- Yersinia mollaretii phytase (YmPhytase): A variant was developed with a 26-fold improvement in activity at neutral pH.

These outcomes were achieved in just four weeks and four rounds of experimentation, requiring the construction and characterization of fewer than 500 variants for each enzyme [30]. This highlights the remarkable speed and efficiency of autonomous platforms. The integration of protein LLMs like ESM-2 for initial library design was crucial to maximizing diversity and quality, with over 55% of initial variants performing above the wild-type baseline [30].

The diagram below contrasts the standard directed evolution workflow with the advanced ALDE process.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Random Mutagenesis in E. coli Using a Mutator Strain

This protocol describes a simple method for generating random mutant libraries in E. coli using a low-fidelity DNA polymerase I, coupled with a functional selection [31].

1. Preparation of Electrocompetent Cells:

- Use a mutator strain like JS 200, which expresses a low-fidelity variant of DNA polymerase I (Pol I). This strain should contain a temperature-sensitive allele of Pol I, ensuring the low-fidelity activity predominates at 37°C.

- Prepare electrocompetent cells of this strain using standard procedures.

2. Electroporation and Library Generation:

- Combine 40 µL of electrocompetent cells with 30-250 ng of a target plasmid. This plasmid must contain a ColE1 origin of replication, with the target sequence cloned adjacent to the origin.

- Electroporate the mixture in a 2 mm gap cuvette at 1800 V. A time constant of 5-6 ms indicates optimal conditions.

- Immediately recover the cell-DNA mixture in 1 mL of LB broth for 40 minutes at 37°C with shaking at 250 RPM.

- Plate the recovered cells on pre-warmed LB agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotics. Plate at a dilution that yields a "near-lawn" concentration of colonies (distinct but uncountable).

- Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Harvest the bacterial colonies from the plates using LB broth and isolate the plasmid DNA. This plasmid pool constitutes the random mutant library.

3. Functional Selection Using a Gradient Plate:

- Gradient Plate Preparation: Mark 10 evenly spaced lanes on the bottom of a square Petri dish. Incline the dish so one end is elevated 7 mm. Pour 25 mL of warm LB agar containing the selecting agent (e.g., an antibiotic) as the bottom layer, creating a thin-to-thick gradient of the agent. Allow it to set. Place the dish on a flat surface and pour 25 mL of warm LB agar without the agent as the top layer.

- Stamp Transfer: Grow cultures of the readout strain transformed with the mutant library, normalizing to an OD600 of <1.0. Mix 40 µL of bacterial culture with 2 mL of soft agar (42°C) in a round dish. Coat the edge of a glass slide with this soft agar mixture and gently touch it to the surface of the gradient plate, aligning with the first mark.

- Analysis: Incubate the gradient plate overnight at 37°C. Image and analyze the growth. The distance grown toward the higher concentration of the selecting agent indicates the level of resistance or improved function conferred by the mutant variants.

Protocol 2: Implementing an ALDE Cycle for Epistatic Residues

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution, ideal for optimizing 3-6 residues with suspected epistasis [29].

1. Define the Design Space and Objective:

- Select k structurally or functionally relevant residues for optimization.

- Define a quantifiable fitness objective (e.g., product yield, enantioselectivity, activity under stress).

2. Initial Library Construction:

- Synthesize an initial library of variants mutated simultaneously at all k positions. For example, use sequential rounds of PCR-based mutagenesis with NNK degenerate codons to cover the sequence space.

- Screen this initial library (e.g., hundreds of variants) using a relevant wet-lab assay to collect the first set of sequence-fitness data.

3. Computational Model Training and Variant Proposal:

- Encoding: Encode the protein sequences from the collected data numerically (e.g., one-hot encoding, embeddings from protein language models).

- Training: Train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., a model capable of uncertainty quantification like Gaussian process regression or ensemble networks) to learn the mapping from sequence to fitness.

- Acquisition: Apply an acquisition function (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound, Expected Improvement) to the trained model. This function will rank all 20^k possible sequences in the design space, balancing the selection of variants predicted to have high fitness (exploitation) with those having high predictive uncertainty (exploration).

4. Iterative Rounds of Experimental Validation:

- The top N (e.g., 50-200) variants from the computational ranking are synthesized and assayed in the wet lab.

- This new sequence-fitness data is pooled with the existing data.

- The model is retrained on the expanded dataset, and the cycle repeats until the fitness objective is met (typically 3-5 rounds).

Quantitative Data and Performance

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Directed Evolution Methodologies

| Method | Key Feature | Typical Rounds | Variants Screened | Reported Improvement | Target System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional DE [28] | Iterative mutagenesis & screening | Often >5 | 10^3 - 10^4 | Varies; can get trapped by epistasis | Broad range of enzymes |

| ALDE [29] | Active learning with uncertainty sampling | ~3 | ~0.01% of search space | Yield: 12% → 99%; High diastereoselectivity | ParPgb cyclopropanation |

| AI-Powered Autonomous Platform [30] | Fully automated DBTL with LLMs | 4 | <500 per enzyme | 16- to 90-fold activity improvement; 26-fold activity at neutral pH | AtHMT, YmPhytase |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mutator Strain | In vivo random mutagenesis by low-fidelity DNA replication. | E. coli JS200 with a low-fidelity, temperature-sensitive Pol I [31]. |

| ColE1 Origin Plasmid | Essential for mutagenesis by low-fidelity Pol I, which initiates replication at this origin. | Standard cloning vectors (e.g., pET, pBAD series) often contain ColE1/pMB1 origins [31]. |

| NNK Degenerate Codon | For site-saturation mutagenesis; allows for all 20 amino acids with only one stop codon. | Used in primer design for constructing focused libraries at defined positions [29]. |

| Protein Language Model (LLM) | Zero-shot prediction of variant fitness for intelligent initial library design. | ESM-2 [30]; used to score variants and prioritize screening. |

| Epistasis Model | Models interactions between mutations to better predict combinatorial effects. | EVmutation [30]; used in conjunction with LLMs for library design. |

| Gradient Plate | Semi-quantitative functional selection based on resistance to inhibitors or other growth-based pressures. | Allows high-throughput discrimination of variant performance without individual assays [31]. |

Directed evolution has matured from a purely experimental practice to a sophisticated discipline integrating computational intelligence and laboratory automation. The emergence of machine learning-guided methods like ALDE and fully autonomous platforms addresses the historical challenge of epistasis, enabling efficient navigation of complex protein fitness landscapes. For scientists engaged in pathway optimization, these advanced directed evolution strategies offer a robust and scalable framework for creating enzyme variants with tailor-made properties. By systematically evolving enhanced biocatalysts, researchers can overcome metabolic bottlenecks and accelerate the development of efficient microbial cell factories for chemical, pharmaceutical, and sustainable bio-based production.

Establishing High-Quality Genetic Libraries and High-Throughput Screening Methodologies

The engineering of robust microbial cell factories necessitates the design and implementation of systems-level metabolic engineering strategies that streamline, modify, and expand biosynthetic capabilities [32]. Central to this endeavor is the construction of high-quality genetic libraries and the implementation of high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies. These tools enable researchers to systematically explore vast genetic landscapes to identify optimal enzyme variants and pathway configurations for enhanced production of valuable biochemicals.