Balancing Act: Strategic Management of NADPH and ATP Cofactors in Engineered Metabolic Pathways for Biomedical Applications

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of maintaining NADPH and ATP cofactor balance in engineered metabolic pathways, a fundamental requirement for efficient bioproduction in microbial cell factories and therapeutic...

Balancing Act: Strategic Management of NADPH and ATP Cofactors in Engineered Metabolic Pathways for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the critical challenge of maintaining NADPH and ATP cofactor balance in engineered metabolic pathways, a fundamental requirement for efficient bioproduction in microbial cell factories and therapeutic development. We explore the foundational principles of cofactor physiology, examine cutting-edge engineering strategies including computational modeling, protein engineering, and synthetic biochemistry modules. The article provides systematic troubleshooting approaches for resolving cofactor imbalance and presents advanced validation techniques using genetically encoded biosensors and flux analysis. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes recent advances to guide the rational design of optimized metabolic systems for pharmaceutical production and biomedical innovation.

The Essential Roles of NADPH and ATP: Understanding Cofactor Physiology in Cellular Metabolism

Fundamental Cofactor Functions & Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: What are the primary cellular roles of NADPH and ATP?

NADPH and ATP are essential cofactors with distinct but interconnected roles in cellular metabolism. NADPH serves primarily as a reducing agent, providing the reducing power (electrons) for anabolic biosynthesis and combating oxidative stress. Its key functions include de novo synthesis of fatty acids, cholesterol, amino acids, and nucleotides, as well as maintaining the cellular antioxidant defense system by regenerating reduced glutathione [1] [2]. In contrast, ATP functions as the universal energy currency, coupling metabolic pathways that release energy with those that require it. It provides the necessary chemical energy for biosynthesis, active transport, and cell motility by donating its high-energy phosphate group [3] [4].

FAQ: What are the most common symptoms of cofactor imbalance in an engineered pathway?

Researchers may observe several tell-tale signs when NADPH and ATP are not adequately balanced:

- Suboptimal Product Titers: The final yield of the target compound is lower than predicted by pathway flux analysis, even when precursor supply seems sufficient [3].

- Accumulation of Metabolic Intermediates: Pathway intermediates may build up due to bottlenecks at cofactor-dependent enzymatic steps.

- Reduced Cellular Growth: Cofactor imbalances can starve primary metabolism, leading to poor biomass accumulation, as seen when glucose-6-phosphate isomerase was inactivated to increase NADPH, which instead reduced cell growth [3].

- Metabolic Rearrangements: Cells may activate compensatory pathways, such as inducing a "futile cycle" of fatty acid synthesis and degradation to convert NADPH into respirable FADH2 when NADH is limited [5].

Troubleshooting Cofactor Imbalances: A Practical Guide

Troubleshooting Guide: My pathway requires significant NADPH, and its absence is a bottleneck. How can I increase NADPH availability?

Enhancing NADPH supply is a common strategy in metabolic engineering. The following table summarizes the key approaches.

Table 1: Strategies for Engineering NADPH Supply in Microbial Hosts

| Strategy | Method | Example Host | Key Enzyme(s) Targeted | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhance Oxidative PPP | Overexpress key enzymes in the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway. | Pichia pastoris | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (ZWF1), 6-phosphogluconolactonase (SOL3) [3] | Combined overexpression increased α-farnesene production by ~12.9% [3]. |

| Introduce Heterologous Enzymes | Express a NADH kinase to convert NADH to NADPH. | Pichia pastoris | POS5 from S. cerevisiae (cPOS5) [3] | Low-intensity expression of cPOS5 aided α-farnesene production [3]. |

| Modulate Cofactor-Consuming Reactions | Downregulate or knock out non-essential NADPH-consuming reactions. | E. coli | NADPH-dependent aldehyde reductase (YahK) [4] | Repression of yahK increased 4HPAA production by 67.1% [4]. |

| Activate Alternative NADPH Sources | Leverage cytosolic or mitochondrial pathways. | Mammalian Cells / Yeast | Cytosolic/mitochondrial Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH1/IDH2), Malic Enzyme (ME1/ME3) [1] [2] | Provides NADPH in compartments outside the cytosol; important for lipid synthesis and redox defense [1]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: My biosynthetic pathway is highly ATP-intensive. What are effective ways to alleviate ATP limitation?

ATP demand must be met to prevent stalling energy-intensive pathways.

- Overexpress Enzymes in ATP Regeneration Pathways: In P. pastoris, overexpressing adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (APRT), a key enzyme in the salvage pathway for AMP synthesis, helped increase ATP availability and boosted α-farnesene production [3].

- Downregulate Competitive ATP-Consuming Processes: A CRISPRi screen in E. coli identified 19 ATP-consuming enzyme genes whose repression improved product yield. For example, repressing the ATP-dependent transport gene fecE was beneficial [4]. This strategy redirects ATP from non-essential functions toward the desired pathway.

- Reduce Metabolic Shunts that Waste NADH: In P. pastoris, inactivating glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD1) blocks the conversion of dihydroxyacetone phosphate to glycerol. This prevents NADH consumption in this shunt pathway, making more NADH available for oxidative phosphorylation and subsequent ATP synthesis [3].

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing and Correcting Imbalance

Protocol 1: Rapid Assessment of Cofactor Competition Using CRISPRi Screening

This protocol is adapted from a study that developed a "Cofactor Engineering based on CRISPRi Screening (CECRiS)" strategy in E. coli [4].

- Strain Construction: Start with a base strain producing your target compound. Introduce a dCas9 protein and a library of sgRNAs targeting all known NADPH-consuming or ATP-consuming enzyme-encoding genes in the host genome.

- Cultivation and Screening: Cultivate the pooled library in a high-throughput format (e.g., 96-well deep plates) under production conditions.

- Product Analysis: Quantify the titer of your desired product in each culture.

- Hit Identification: Identify strains with improved product yields. The sgRNAs in these strains target cofactor-consuming genes whose repression liberates NADPH or ATP for your pathway.

- Validation: Construct dedicated knockout or knockdown strains for the top hit genes to confirm the phenotype.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cofactor Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors (e.g., iNAP, SoNar) | Real-time, live-cell monitoring of NADPH/NADP+ or NADH/NAD+ ratios [2]. | Visualizing dynamic changes in cofactor balance in response to genetic modifications or stress. |

| CRISPRi/dCas9 System | Targeted repression of specific genes without knockout [4]. | Systematically identifying and downregulating competitive NADPH or ATP consumers, as in the CECRiS strategy. |

| Heterologous Enzymes (e.g., POS5, Transhydrogenases) | Provide alternative routes for cofactor regeneration or interconversion [3]. | Expressing NADH kinase (POS5) to convert NADH into NADPH. |

| Enzymatic Cycling Assays & LC-MS | Accurate, absolute quantification of NADPH, NADH, ATP, ADP, etc., from cell lysates [2]. | Precisely measuring intracellular cofactor pools and their ratios in different engineered strains. |

Protocol 2: Rational Engineering of NADPH and ATP Regeneration Pathways

This protocol is based on the successful multi-step engineering of Pichia pastoris for α-farnesene production [3].

- Baseline Characterization: Measure the NADPH/NADP+ and ATP/ADP ratios in your baseline production strain during the fermentation process.

- Engineer NADPH Supply:

- Modify the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP): Overexpress key oxidative PPP genes like ZWF1 and SOL3. Note: Avoid complete disruption of glycolysis, as seen when PGI was inactivated, which reduced cell growth [3].

- Introduce a NADH Kinase: Integrate a gene like cPOS5 from S. cerevisiae under a tunable promoter. Fine-tune expression to avoid excessive NADH drainage.

- Engineer ATP Supply:

- Amplify the AMP Pool: Overexpress enzymes in the adenosine salvage pathway, such as APRT, to enhance the precursor pool for ATP synthesis.

- Conserve Reducing Equivalents: Inactivate shunts like the glycerol pathway by deleting GPD1 to make more NADH available for respiratory ATP generation.

- Fermentation and Validation: Ferment the final engineered strain and quantify both the target product titer and the intracellular cofactor levels to validate the improvement.

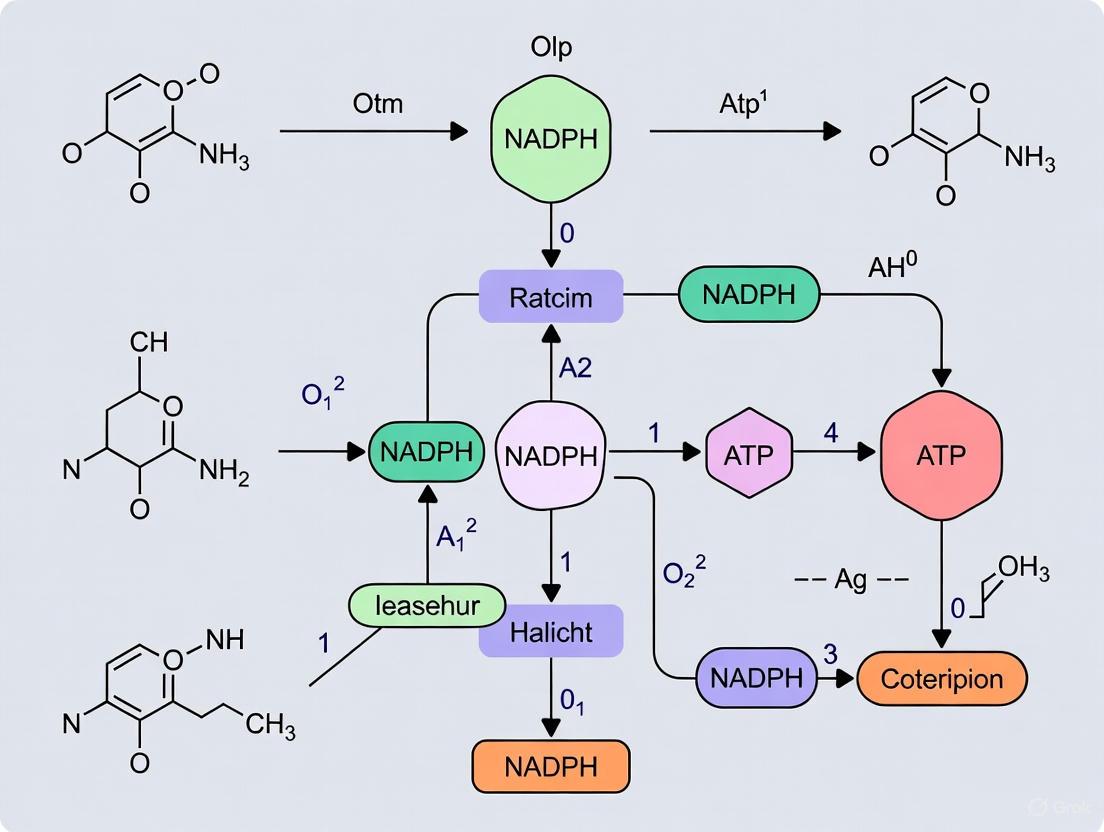

Visualizing Cofactor Balance and Engineering Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of cofactor balancing between energy generation, redox power, and biosynthesis, and how engineering interventions can optimize this balance.

Diagram: Strategies for Balancing Cofactor Metabolism. The diagram shows how engineering interventions (red for enhancement, green for repression) can be applied to key nodes in NADPH and ATP metabolism to redirect flux toward desired biosynthetic pathways. The diagram is conceptual and does not represent a complete metabolic network.

NADPH/NADP+ as Central Redox Couples in Anabolic Processes and Cellular Defense

Troubleshooting Guide: Common NADPH Homeostasis Issues in Engineered Systems

Problem 1: Insufficient NADPH Supply Limiting Product Yields

- Symptoms: Low titers of target compounds (e.g., 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate, fatty acids, terpenoids); accumulation of oxidized glutathione (GSSG); increased cellular oxidative stress.

- Underlying Cause: The demand for NADPH in your engineered pathway exceeds the cell's native regeneration capacity. The anabolic demand for NADPH is coupled to the rate of biomass formation and the requirements of introduced pathways [6].

- Solutions:

- Amplify Native NADPH Pathways: Overexpress key enzymes from the oxidative Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP), such as Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD) [7] [8].

- Engineer Cofactor Specificity: Switch the cofactor preference of native enzymes from NAD(H) to NADP(H). A global candidate is glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; this can be achieved by replacing conserved glutamate or aspartate with serine in the loop region [9].

- Introduce Transhydrogenases: Overexpress membrane-bound (pntAB) or soluble (sthA) transhydrogenases to convert NADH to NADPH, balancing the cofactor pool [8] [6].

- Utilize Formate Dehydrogenase: Express formate dehydrogenases (e.g., from Candida boidinii) to regenerate NAD(P)H from the oxidation of inexpensive sodium formate [8].

Problem 2: NADPH/NADP+ Imbalance Disrupting Redox State

- Symptoms: Reduced cell growth, metabolic hysteresis, failure to maintain reduced glutathione (GSH) levels, high ROS-induced cytotoxicity.

- Underlying Cause: The high NADPH/NADP+ ratio is not maintained, compromising the cell's antioxidant defense system. The NADPH system is essential for regenerating reduced glutathione and thioredoxin [7] [1].

- Solutions:

- Modulate Carbon Flux: Reroute carbon flux into the PPP. This can be done by knocking out glycolytic genes like 6-phosphofructokinase 1 (pfkA) to increase the pool of glucose-6-phosphate available for the PPP [8].

- Enhance NADPH Generation from TCA Cycle: Overexpress cytosolic or mitochondrial isoforms of NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1/IDH2) or malic enzyme (ME1/ME3) to generate NADPH from mitochondrial TCA-cycle intermediates [7] [1].

- Overexpress NAD Kinase (NADK): Increase the total pool of NADP+ available for reduction to NADPH by amplifying the activity of NADK, which phosphorylates NAD+ to NADP+ [7].

Problem 3: Inefficient Coupling of NADPH Regeneration to Biosynthesis under Non-Growing Conditions

- Symptoms: Product synthesis halts when growth ceases (e.g., under nitrogen limitation); carbon flux is not efficiently redirected from central metabolism to production pathways.

- Underlying Cause: The metabolic network lacks a mandatory link between product formation and redox balance during stationary or production phases.

- Solutions:

- Design Coupled Pathways: Implement pathways where product formation is essential for recycling NADP+ back to NADPH. For example, in an acetol-producing E. coli strain, the NADPH-dependent acetol biosynthesis pathway becomes crucial for maintaining the NADPH/NADP+ balance during nitrogen-limited, non-growing conditions [10].

- Use Nutrient-Limited Conditions: Strategically use nutrient limitation (e.g., nitrogen) to uncouple growth from production and force flux re-routing towards the NADPH-consuming product pathway [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary metabolic pathways for NADPH generation, and how do I choose which one to engineer?

The primary pathways and their key enzymes are summarized in the table below [7] [1].

Table 1: Major NADPH-Generating Pathways and Their Features

| Pathway | Key Enzyme(s) | Compartment | Notes and Engineering Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | G6PD, PGD | Cytosol | The largest contributor to cytosolic NADPH [11]. Ideal for boosting reducing power for cytosolic anabolism. Flux is feedback-inhibited by NADPH [11]. |

| Isocitrate Dehydrogenase | IDH1 (cytosol), IDH2 (mitochondria) | Both | Links TCA cycle to NADPH production. Requires citrate export from mitochondria for cytosolic IDH1 [1]. |

| Malic Enzyme | ME1 (cytosol), ME3 (mitochondria) | Both | Converts malate to pyruvate, generating NADPH. Part of a cycle that also produces cytosolic acetyl-CoA for lipogenesis [1]. |

| Folate Metabolism | MTHFD1, MTHFD2 | Both | Generates NADPH in both the cytosol and mitochondria, integrated with one-carbon unit metabolism for nucleotide synthesis [7] [1]. |

| Transhydrogenation | PntAB (NADH->NADPH), UdhA (NADPH->NADH) | Cytosol/Membrane | Does not generate de novo NADPH but balances the NADH/NADPH ratio. PntAB is proton-motive force driven [6]. |

The choice depends on the host organism, the subcellular location of your pathway, and the carbon source. For glucose-based growth, engineering the PPP is often most effective. For glutamine-based metabolism, IDH and malic enzyme may be more significant.

Q2: How can I quantitatively measure the NADPH/NADP+ ratio in my engineered cells?

A standard protocol involves rapid sampling and extraction to preserve the in vivo redox state, followed by HPLC-UV analysis [10].

- Sampling & Quenching: Quickly sample cell broth (e.g., 4 mL) directly into a tube containing cold perchloric acid, thoroughly mixing to immediately halt metabolism and stabilize cofactors. At acidic pH, the oxidized forms (NADP+) are stable [10].

- Neutralization: Centrifuge the sample and neutralize the supernatant with appropriate amounts of K~2~HPO~4~ and KOH.

- HPLC Analysis: Analyze the extract using HPLC-UV with a reversed-phase column (e.g., LiChrospher RP-18). A gradient elution with a phosphate-TBAHS buffer system is typically used to separate and quantify the different cofactors [10].

Q3: My product requires NADPH, but I observe redox stress and poor growth. What strategies can help?

This indicates a strong imbalance. Consider:

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement regulatory systems that decouple pathway expression from growth, expressing your NADPH-consuming pathway heavily only after biomass accumulation.

- Synthetic Transhydrogenase Cycles: Design synthetic cycles that use excess ATP or another energy source to drive NADPH formation without being directly coupled to carbon catabolism [9].

- Cofactor Specificity Engineering (CSE): Re-engine your pathway enzymes to accept NADH instead of NADPH, thereby shifting the redox burden to the more abundant NAD(H) pool [9].

Q4: Are there computational tools to predict NADPH flux and guide engineering strategies?

Yes, in silico model-driven approaches are central to modern cofactor engineering.

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Use genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to predict intracellular fluxes and identify enzyme targets whose cofactor specificity switching (CSE) will improve overall NADP(H) turnover [9].

- Flux-Sum Analysis: A metabolite-centric approach to understand the metabolic network and identify key nodes for engineering [9].

- Cofactor Modification Analysis (CMA): A computational framework to systematically identify cofactor specificity engineering targets for strain improvement [9].

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing NADPH Supply via the Pentose Phosphate Pathway

Aim: To engineer an E. coli host for increased NADPH supply to support the production of NADPH-demanding compounds (e.g., 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate [8]).

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli BL21(DE3) or other relevant production strain.

- Plasmids: Overexpression vectors for zwf (G6PD) and gnd (PGD).

- Knockout Kit: For deleting pfkA (6-phosphofructokinase 1).

Method:

- Strain Construction:

- Knockout: Delete the pfkA gene from the chromosome to reduce glycolytic flux and increase the pool of glucose-6-phosphate [8].

- Overexpression: Co-transform the strain with plasmids overexpressing zwf and gnd under strong, inducible promoters (e.g., P~Trc~ or P~T7~).

- Cultivation:

- Grow the engineered strain in a defined minimal medium (e.g., M9) with glucose as the sole carbon source.

- Induce gene expression at mid-log phase.

- Validation & Analysis:

- Measure NADPH/NADP+: Use the HPLC protocol described in FAQ A2 to confirm an increased NADPH/NADP+ ratio.

- Quantify Product: Measure the titer of your target product (e.g., via HPLC or LC-MS) to assess the impact of increased NADPH supply.

- Flux Analysis (Optional): Perform ^13^C-metabolic flux analysis (^13^C-MFA) using labeled glucose (e.g., 1-^13^C-glucose) to quantitatively confirm the increased flux through the PPP oxidative phase [10].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this protocol:

Visualization of NADPH Metabolism and Engineering Nodes

The diagram below maps the central roles of NADPH and key engineering targets for balancing its homeostasis in a cellular context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for NADPH Research

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Strains for NADPH Engineering Experiments

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) | Catalyzes the first, rate-limiting step of the PPP, producing NADPH [11]. | Overexpression to boost cytosolic NADPH supply [8]. |

| NAD Kinase (NADK) | Phosphorylates NAD+ to generate NADP+, the precursor for NADPH [7]. | Overexpression to increase the total cellular pool of NADP(H) [7]. |

| Membrane-bound Transhydrogenase (PntAB) | Converts NADH and NADP+ to NAD+ and NADPH, coupling to proton translocation [6]. | Balancing cofactor pools when NADH is abundant but NADPH is limiting [8] [6]. |

| Formate Dehydrogenase (FDH) | Oxidizes formate to COâ‚‚, reducing NAD(P)+ to NAD(P)H [8]. | External regeneration of NAD(P)H using inexpensive sodium formate as an electron donor [8]. |

| ^13^C-Labeled Glucose (e.g., 1-^13^C) | Tracer for metabolic flux analysis (^13^C-MFA). | Quantifying in vivo flux through the PPP versus glycolysis [10]. |

| Engineered E. coli Strains | Hosts with modified central metabolism (e.g., ΔpfkA, ΔldhA, etc.) [8] [10]. | Providing a chassis with optimized carbon flux toward NADPH-generating pathways [8] [10]. |

| Quinuclidin-3-yldi(thiophen-2-yl)methanol | Quinuclidin-3-yldi(thiophen-2-yl)methanol CAS 57734-75-5 | Quinuclidin-3-yldi(thiophen-2-yl)methanol is an α7 nAChR ligand for neurological research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2,2-Dimethyl-2,3-dihydroperimidine | 2,2-Dimethyl-2,3-dihydroperimidine, CAS:6364-17-6, MF:C13H14N2, MW:198.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

ATP/ADP as Universal Energy Currency Driving Biosynthetic Reactions

Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) serves as the universal energy currency in all living cells, providing the fundamental driving force for biosynthetic reactions. In metabolic engineering, managing the balance between ATP and its counterpart ADP, along with redox cofactors like NADPH, is critical for optimizing pathway efficiency in engineered biological systems. This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers and scientists troubleshooting cofactor balance issues in engineered pathways, offering proven methodologies to diagnose and resolve common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What makes ATP the "universal energy currency" rather than other nucleotides like GTP or UTP? ATP is uniquely suited as the primary energy currency due to its molecular structure and thermodynamic properties. The hydrolysis of ATP to ADP releases significant energy (-30.5 kJ/mol or -7.3 kcal/mol) that drives cellular processes [12] [13]. This intermediate energy value positions ATP perfectly to phosphorylate lower-energy compounds while itself being regenerated by higher-energy compounds [14] [13]. Though other nucleotides (GTP, UTP, CTP) participate in specialized metabolic reactions, ATP's ability to readily donate single phosphates, two phosphates, or its adenosine moiety makes it uniquely versatile for energy transfer [15].

2. Why is cofactor balance particularly crucial in engineered metabolic pathways? Engineered pathways disrupt native cellular homeostasis, creating cofactor imbalances that compromise efficiency. Introducing synthetic pathways alters the careful balance of ATP/ADP and NAD(P)/NAD(P)H pools that cells maintain through evolution [16]. Even small changes in these cofactor pools can have wide effects, potentially leading to partial or complete disruption of cellular physiology [16]. Proper cofactor balance ensures that synthetic pathways don't create metabolic bottlenecks that divert resources toward wasteful cycles or biomass formation instead of target compound production [16].

3. How can I troubleshoot inconsistent ATP measurement results in my experiments? Inconsistent ATP measurements often stem from methodological errors rather than biological factors:

- Technique Issues: Apply consistent pressure and use overlapping "Z" pattern when swabbing surfaces [17]

- Timing: Wait 10-15 minutes after cleaning before swabbing, as residual sanitizers interfere with ATP detection [17]

- Sample Integrity: Avoid touching swab tips and ensure proper storage conditions (typically 36–46°F/2–8°C) [17]

- Equipment Maintenance: Regularly clean sensors and calibrate luminometers according to manufacturer specifications [17]

4. What strategies exist for reversing NAD/NADP cofactor specificity in enzymes? A structure-guided, semi-rational strategy called CSR-SALAD (Cofactor Specificity Reversal - Structural Analysis and LibrAry Design) has proven effective for reversing enzymatic nicotinamide cofactor utilization [18]. This approach involves:

- Enzyme structural analysis to identify specificity-determining residues

- Design and screening of focused mutant libraries

- Recovery of catalytic efficiency through compensatory mutations [18] The method successfully inverted cofactor specificity in four structurally diverse NADP-dependent enzymes: glyoxylate reductase, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase, xylose reductase, and iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Yield in Engineered Pathways

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Cofactor Balance Indicators and Interventions

| Observation | Potential Imbalance | Intervention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced product yield with increased biomass | ATP surplus | Engineer ATP-requiring (negative ATP yield) pathways [16] |

| Accumulation of metabolic waste products | Redox imbalance (NAD(P)H) | Modulate PPP flux via gndA or gsdA overexpression [19] |

| Inconsistent performance across conditions | Cofactor specificity mismatch | Implement CSR-SALAD for specificity reversal [18] |

| Stunted growth with pathway activity | ATP/redox deficit | Introduce NADP-dependent GAPDH to generate NADPH instead of NADH [19] |

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Quantify Cofactor Pools: Measure intracellular ATP/ADP and NADPH/NADP+ ratios using standard enzymatic assays

- Flux Analysis: Employ 13C metabolic flux analysis to determine PPP versus EMP pathway utilization [19]

- Computational Modeling: Use Constraint-Based Modelling and co-factor balance assessment (CBA) to predict network-wide effects of pathway engineering [16]

Problem: Enzyme Cofactor Specificity Mismatch

Engineering Workflow:

Implementation Steps:

- Structural Analysis: Input enzyme structure into CSR-SALAD web tool to identify residues contacting the 2' moiety of NAD/NADP [18]

- Library Design: Generate focused mutant libraries using degenerate codons at specificity-determining positions [18]

- Specificity Screening: Screen for activity with non-preferred cofactor using high-throughput methods

- Activity Recovery: Introduce compensatory mutations around adenine ring binding pocket to restore catalytic efficiency [18]

- Pathway Integration: Test engineered enzyme in full pathway context to verify performance

Problem: Inadequate NADPH Supply for Biosynthesis

Enhancement Strategies:

Table: NADPH Generation Enzymes for Cofactor Engineering

| Enzyme | Gene | Pathway | Effect on NADPH | Impact on Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | gsdA | Pentose Phosphate | Moderate increase | Variable (can be negative) [19] |

| 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | gndA | Pentose Phosphate | 45% pool increase | 65% yield increase [19] |

| NADP-dependent malic enzyme | maeA | Reverse TCA cycle | 66% pool increase | 30% yield increase [19] |

| NADP-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GapN | Glycolysis | Significant (theoretical) | 70-120% yield improvement in C. glutamicum [19] |

Experimental Protocol for NADPH Enhancement:

- Gene Selection: Choose appropriate NADPH-generating enzyme based on host organism and pathway constraints

- Expression Optimization: Use tunable systems (e.g., Tet-on) to control expression levels [19]

- Flux Analysis: Employ chemostat cultures with metabolome analysis to verify NADPH pool increases [19]

- Production Correlation: Measure target compound yield to validate engineering success

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Cofactor Balance Research

| Reagent/Kit | Application | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hygiena UltraSnap ATP swabs | ATP monitoring | Room temperature storage | Check expiration dates; proper storage critical [17] |

| EnSURE Touch luminometer | RLU measurement | Built-in diagnostics | Regular sensor cleaning required [17] |

| CSR-SALAD web tool | Cofactor specificity reversal | Automated structural analysis | Free online resource [18] |

| Genome-scale metabolic models | Cofactor balance prediction | Systems-level analysis | Requires computational expertise [16] |

Advanced Methodologies

Computational Cofactor Balance Assessment

Protocol:

- Model Construction: Use established stoichiometric models (e.g., E. coli core model) [16]

- Pathway Implementation: Introduce heterologous reactions with correct stoichiometry

- Balance Analysis: Apply FBA-based co-factor balance assessment (CBA) algorithm [16]

- Flux Validation: Compare predictions with 13C-MFA data where available

- Futile Cycle Identification: Manually constrain models to eliminate unrealistic cycling [16]

Metabolic Engineering for Cofactor Balancing

Integrated Workflow:

Implementation Notes:

- Strategy Selection: Choose between NADPH generation enhancement (PPP enzymes), cofactor specificity reversal, or ATP balancing based on diagnostic results

- Genetic Implementation: Use CRISPR/Cas9 for precise genome editing and tunable promoters for fine-tuned expression [19]

- Analytical Validation: Combine metabolomics (cofactor pools), fluxomics (pathway utilization), and product quantification for comprehensive assessment

- Iterative Refinement: Apply DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) cycles to progressively improve cofactor balance and pathway performance [19]

Cofactor balance, particularly of ATP and NADPH, is a fundamental requirement for the maintenance of metabolism, energy generation, and growth in engineered biological systems [20]. Metabolic compartmentalization—the spatial and temporal separation of pathways and components—is a key organizational principle that cells use to manage this balance [21]. For metabolic engineers, understanding and engineering this compartmentalization is essential for designing efficient microbial cell factories, as it fulfills three primary functions or "pillars": establishing unique chemical environments for reactions, protecting the cell from reactive intermediates, and providing precise regulatory control over metabolic pathways [21]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and key resources to help researchers navigate the challenges of managing cofactor pools in engineered pathways.

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. My pathway has the necessary enzymes expressed, but product titers are low and growth is impaired. Could cofactor imbalance be the issue?

- Answer: Yes, this is a classic symptom of cofactor imbalance. Your pathway may be consuming NADPH or ATP faster than native metabolism can regenerate it, or vice-versa.

- Solutions:

- Quantify the Demand: First, calculate the theoretical ATP:NADPH demand of your engineered pathway. A recent meta-analysis revealed that pathways like starch and sucrose synthesis make a notable contribution to the overall energy demand, which can counterbalance the demand from other routes like photorespiration [22].

- Engineer Cofactor Regeneration: Implement synthetic cofactor regeneration cycles. For NADPH supply, consider overexpressing genes from the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (e.g., G6PDH, 6PGDH) or introducing a transhydrogenase [23].

- Modify Cofactor Preference: Use protein engineering to alter the cofactor specificity of a key enzyme in your pathway from NADPH to NADH, as the latter is often more abundant under anaerobic conditions [23] [20].

2. How can I determine if subcellular localization is causing a bottleneck in my cofactor-dependent pathway?

- Answer: A compartmentalization bottleneck is likely if an enzyme shows high activity in vitro but not in vivo, or if metabolic flux models predict higher yields than are experimentally achieved.

- Solutions:

- Re-target Enzymes: Re-locate your pathway enzymes to a cellular compartment with a more favorable cofactor pool. For instance, engineering the functional expression of prokaryotic P450 enzymes in yeast mitochondria, rather than the cytosol, significantly improved the production of 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid by leveraging the mitochondrial environment and NADPH supply [24].

- Create Synthetic Compartments: Use synthetic biology tools to create engineered metabolic organelles or protein scaffolds to concentrate pathway enzymes and cofactors, thus enhancing flux and preventing cross-talk with native metabolism [21].

3. I have engineered a cofactor regeneration system, but it has caused unexpected reductions in the synthesis of my target product. Why?

- Answer: Cofactor perturbations can have widespread, systemic effects because redox cofactors are among the most highly connected metabolites in the network [20]. Altering one pool can divert key precursors away from your target pathway.

- Solutions:

- Analyze Precursor Availability: Check the levels of key pathway precursors like acetyl-CoA and α-keto acids. A study in Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed that redox imbalance modified the formation of all volatile compounds from the same biochemical pathway due to its impact on central carbon metabolism intermediates [20].

- Perturbation Analysis: Use a dedicated biological tool, like the overexpression of a native NADH-dependent or engineered NADPH-dependent 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase in the presence of acetoin, to specifically perturb cofactor balance and analyze the resulting metabolic changes without permanently altering central metabolism [20].

4. My microbial host shows poor energy efficiency after pathway introduction. Which reactions are the most energy-expensive?

- Answer: Energy failure may not be a general deficiency in producing ATP, but a failure to recoup the ATP cost of certain processes. A genome-wide CRISPR screen identified hexokinase 2 (HK2), the first enzyme in glycolysis, as one of the greatest ATP consumers in a human cell line [25].

- Solutions:

- Identify Key Consumers: Use computational models or literature mining to identify the most energy-expensive steps in your host's metabolic network.

- Modulate Consumers: Consider down-regulating high-consumption reactions that are non-essential for your production objective. The screen revealed that suppressing HK2 or its binding partner VDAC1 increased ATP levels under respiratory conditions [25].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying In Vivo Cofactor Pools and Ratios

This protocol describes a method for measuring the absolute concentrations of NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH in microbial cultures, adapted from a study on redox cofactor perturbations [20].

1. Principle: Rapid quenching of metabolism to preserve in vivo state, followed by metabolite extraction and enzymatic assay or LC-MS/MS quantification.

2. Reagents:

- Quenching Solution: Cold methanol buffer (60% methanol, 70 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) at -40 °C.

- Extraction Buffer: 100% methanol or acetonitrile-based buffer.

- Analytical Standards: Stable isotope-labeled internal standards for NAD+, NADH, NADP+, NADPH.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Culture Sampling. Rapidly withdraw a known volume of culture (e.g., 5-10 mL) and immediately mix it with a larger volume of pre-chilled Quenching Solution (-40 °C) to instantaneously halt metabolic activity.

- Step 2: Metabolite Extraction.

- Centrifuge the quenched cells at high speed (e.g., 10,000 x g, 5 min, -20 °C).

- Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in cold Extraction Buffer.

- Vortex or sonicate the suspension to lyse cells and release intracellular metabolites.

- Centrifuge again to remove cell debris. The supernatant containing the metabolites is used for analysis.

- Step 3: Analysis.

- Option A (Enzymatic): Use specific cycling assays for each cofactor. For example, quantify NADPH using glutathione reductase and 5,5'-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB).

- Option B (LC-MS/MS): This is the preferred method for simultaneous and specific quantification. Separate the extracted cofactors using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and detect them via tandem mass spectrometry. Use the internal standards for precise quantification.

4. Data Analysis: Calculate the concentration of each cofactor (in nmol/gDCW) and determine the ratios NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH. These ratios are key indicators of the cellular redox state.

Protocol 2: Engineering Compartmentalization for Cofactor-Dependent Pathways

This protocol outlines the strategy used to successfully produce 10-HDA in S. cerevisiae by harnessing mitochondrial compartmentalization [24].

1. Principle: Re-locate a cofactor-intensive pathway to an organelle with a favorable environment to enhance flux, stability, and cofactor availability.

2. Reagents:

- Expression Vectors: Plasmids with promoters for strong, constitutive expression (e.g., TEF1, PGK1).

- Targeting Sequences: DNA sequences encoding mitochondrial targeting signals (MTS) for N-terminal fusion to enzymes.

- Chaperone Plasmids: Vectors for co-expressing chaperone proteins (e.g., mitochondrial Hsp60) to assist in the folding of recombinant enzymes [24].

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Pathway Design and Gene Synthesis. Design the heterologous pathway (e.g., the β-oxidation pathway for 10-HDA). Codon-optimize genes for your host.

- Step 2: Addition of Targeting Sequences. Fuse mitochondrial targeting signals to the N-terminus of the enzymes you wish to localize to the mitochondria. For the P450 enzyme in the 10-HDA study, this was critical for functional expression [24].

- Step 3: Chassis Engineering.

- Transform the host with the engineered gene constructs.

- To enhance the mitochondrial NADPH supply, consider overexpressing enzymes that generate NADPH in the mitochondria, such as a mitochondrial-targeted NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase.

- Step 4: Fed-Batch Fermentation.

- To mitigate substrate toxicity, use a fed-batch strategy with a less toxic substrate precursor. In the 10-HDA example, using ethyl decanoate instead of decanoic acid increased production 7.5-fold [24].

- Monitor product titer and cell density throughout the fermentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents and tools for engineering cofactor systems and compartmentalization.

| Reagent/Tool | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi/a System [25] | Genome-wide screening to identify genes that regulate ATP levels (the "ATPome") or other cofactors. | Enables discovery of both ATP consumers (CRISPRi) and genes that boost ATP when overexpressed (CRISPRa). |

| Isotopically Non-Stationary Metabolic Flux Analysis (INST-MFA) [22] | Quantitative mapping of in vivo metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) in central carbon metabolism. | Essential for experimentally measuring the energy (ATP:NADPH) demand of different pathways under various conditions. |

| 2,3-Butanediol Dehydrogenase (Bdh) [20] | A dedicated biological tool for targeted perturbation of NADH or NADPH balance. An engineered NADPH-dependent version allows for specific cofactor manipulation. | Used with acetoin to create a controlled sink for reduced cofactors, allowing study of the metabolic response. |

| Mitochondrial Targeting Signal (MTS) [24] | Peptide sequence fused to enzymes to re-target them from the cytosol to the mitochondrial matrix. | Used to leverage unique chemical environments and potentially higher cofactor concentrations in organelles. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) [26] | Computational stoichiometric models of metabolism used for in silico prediction of metabolic fluxes. | Use with algorithms like OptORF to predict gene knockouts that optimize cofactor balance and product yield. |

| N-(6-nitro-1,3-benzothiazol-2-yl)acetamide | N-(6-nitro-1,3-benzothiazol-2-yl)acetamide, CAS:80395-50-2, MF:C9H7N3O3S, MW:237.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-cyano-N-(3-phenylpropyl)acetamide | 2-cyano-N-(3-phenylpropyl)acetamide, CAS:133550-33-1, MF:C12H14N2O, MW:202.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

Pillars of Compartmentalization

Mitochondrial Engineering Workflow

Cofactor Engineering Strategies and Data

Table 2: Summary of cofactor engineering approaches and their outcomes.

| Engineering Strategy | Specific Action | Organism | Key Outcome / Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Balance [23] | Modifying overflow metabolism (e.g., glycerol production) | S. cerevisiae | Automatically maintains redox balance by rerouting central carbon metabolism. |

| Substrate Balance [23] | Providing electron acceptors or altering culture conditions (e.g., oxygen) | Microbes | Achieves optimal NADH/NAD+ ratio by modifying NADH reoxidation. |

| Synthetic Balance [23] | Protein engineering to switch cofactor preference (NADPHNADH) | Various | Rebalances oxidoreduction potential in imbalanced pathways, improving product yield. |

| Compartmentalization [24] | Rewiring β-oxidation + P450 expression in mitochondria | S. cerevisiae | Achieved 298.6 mg/L of 10-HDA, the highest titer in yeast, by leveraging compartmentalization. |

| CRISPR-based Screening [25] | Inhibition (CRISPRi) of hexokinase 2 (HK2) | Human K562 cells | Increased ATP levels under respiratory conditions by suppressing a major ATP consumer. |

The Critical Link Between Cofactor Imbalance and Reduced Bioproduction Yields

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving NADPH Limitation

Problem: Low product yield in pathways dependent on NADPH, such as fatty acid or amino acid biosynthesis.

Question: How can I determine if my production strain is experiencing NADPH limitation, and what are the primary strategies to overcome it?

Answer: NADPH limitation is a common bottleneck in reductive biosynthetic pathways. Diagnosis can involve checking for an accumulation of pathway intermediates or using genetically encoded biosensors to monitor the intracellular NADPH/NADP+ ratio [27]. The solutions below are ranked from the most common and straightforward to the more advanced.

1. Reinforce the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP): This is the primary source of cytosolic NADPH. * Action: Overexpress the genes zwf (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) and gnd (6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase) [27]. * Example: In E. coli, enhancing the PPP flux has been used to improve the production of products like poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) [27].

2. Employ a Cofactor Boosting System: A versatile approach to generally enhance the pool of cofactor precursors. * Action: Implement a system like xylose reductase with lactose (XR/lactose). This system increases sugar phosphate pools, which are connected to the biosynthesis of NADPH, FAD, FMN, and ATP [28]. * Example: The XR/lactose system increased productivities in fatty alcohol biosynthesis, bioluminescence generation, and alkane biosynthesis by 2-4 fold in E. coli [28].

3. Engineer Cofactor Specificity: * Action: Replace a native NADH-dependent enzyme in your pathway with a non-native NADPH-dependent version. * Example: Replacing the native E. coli glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPD, gapA) with the NADPH-dependent GAPD from Clostridium acetobutylicum (gapC) can increase NADPH availability for product synthesis [29].

4. Implement Dynamic Regulation: * Action: Use genetically encoded biosensors to dynamically regulate the NADPH/NADP+ balance in real-time, moving beyond static overexpression [27]. * Example: The SoxR biosensor in E. coli or the NERNST biosensor can be used to monitor and respond to the intracellular NADPH/NADP+ status [27].

Guide 2: Addressing NADH/NAD+ Imbalance

Problem: Reduced cell growth, metabolic arrest, or byproduct accumulation due to an overload of NADH, often a problem in cyanobacteria or pathways producing excess reducing equivalents.

Question: My pathway generates excess NADH, leading to reductive stress and poor performance. How can I rebalance the NADH/NAD+ pool?

Answer: An excess of NADH can inhibit critical metabolic enzymes and waste energy. The goal is to increase NADH oxidation or reduce its net production.

1. Introduce NADH Oxidase (Nox): * Action: Express a heterologous NADH oxidase to convert NADH to NAD+. * Example: Expression of SpNox from Streptococcus pyogenes in E. coli created an NAD+ regeneration system that helped achieve a high pyridoxine titer of 676 mg/L by alleviating NADH surplus [30] [31].

2. Swap Cofactor Specificity in Glycolysis: * Action: Modify central metabolism to reduce NADH generation. Substitute the native NADH-producing glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase with a NADPH-producing version. * Example: In E. coli, this swap reduces glycolytic NADH production, helping to balance cofactors for targets like pyridoxine [30].

3. Leverage Native Pathways in Specialized Organisms: * Action: In cyanobacteria, which have an inherently NADPH-rich pool, express NADPH-dependent versions of enzymes that are normally NADH-dependent. * Example: Changing the cofactor specificity of enzymes in cyanobacteria from NADH to NADPH can overcome the innate cofactor imbalance and enhance production of chemicals like ethanol or lactic acid [32].

Guide 3: Overcoming ATP and Energy Cofactor Deficits

Problem: Stalled biosynthesis in ATP-intensive pathways, such as luciferase-based systems or the production of certain polymers.

Question: How can I enhance the ATP supply to drive energy-intensive bioproduction?

Answer: 1. Utilize a Generic Cofactor Booster: * Action: Systems that enhance sugar phosphate pools, like the XR/lactose system, also propagate benefits to ATP biosynthesis [28]. * Example: The XR/lactose system enhanced bioluminescence light generation in E. coli, a process with high demand for ATP [28].

2. Engineer ATP Regeneration Pathways: * Action: Overexpress enzymes like polyphosphate kinase to regenerate ATP from ADP and polyphosphate [28].

Table 1: Summary of Common Cofactor Imbalances and Solutions

| Cofactor Issue | Key Symptoms | Recommended Engineering Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| NADPH Limitation | Low yield of reduced products (e.g., alcohols, fatty acids); Accumulation of oxidized precursors. | • Reinforce Pentose Phosphate Pathway (zwf, gnd overexpression) [27]• Use XR/lactose boosting system [28]• Implement Cofactor Swapping (e.g., gapC) [29] |

| NADH/NAD+ Imbalance | Reductive stress; Impaired cell growth; Byproduct formation (e.g., lactate, ethanol). | • Express NADH Oxidase (Nox) [30] [31]• Reduce NADH production via glycolytic enzyme swaps [30]• Use NADPH-dependent enzymes in cyanobacteria [32] |

| ATP Deficit | Stalled anabolic processes; Low yields in energy-intensive pathways (e.g., luminescence). | • Deploy XR/lactose system [28]• Engineer ATP regeneration (e.g., polyphosphate kinase) [28] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between NADH and NADPH in cellular metabolism, and why does it matter for metabolic engineering?

While both are reducing equivalents, they are functionally segregated. NADH is primarily involved in catabolic reactions to generate ATP, whereas NADPH is primarily used for anabolic (biosynthetic) reactions and antioxidant defense [1]. This division allows the cell to independently manage energy production and biomass synthesis. Imbalances occur when engineered pathways disrupt this natural partition, for example, by consuming too much NADPH and starving native biosynthesis, or by generating excess NADH that cannot be re-oxidized [23] [29].

FAQ 2: Beyond the PPP, what are other major sources of NADPH in the cell that I can engineer?

Two other crucial sources are:

- Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH): Both the cytosolic (IDH1) and mitochondrial (IDH2) enzymes generate NADPH from isocitrate in the TCA cycle [1] [27].

- Malic Enzyme (ME): The cytosolic (ME1) and mitochondrial (ME3) enzymes generate NADPH by converting malate to pyruvate [1]. Engineering these pathways, such as by overexpressing IDH genes from other species, has been shown to enhance NADPH supply [27].

FAQ 3: What are the pros and cons of static vs. dynamic regulation for cofactor balancing?

- Static Regulation (e.g., gene knockout, constitutive overexpression): This is simpler to implement but cannot respond to changing cellular conditions. It often leads to metabolic burdens or new imbalances because the regulation is fixed [27].

- Dynamic Regulation: This uses biosensors to monitor cofactor levels (like the NADPH/NADP+ ratio) and adjust gene expression in real-time. It is more sophisticated and maintains metabolic flexibility, preventing imbalance by responding to the cell's actual needs [27]. This is considered a more advanced and robust strategy.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the XR/Lactose Cofactor Boosting System

Objective: To enhance the intracellular pool of multiple cofactors (NADPH, FAD, FMN, ATP) in E. coli to support engineered pathways.

Background: This system uses xylose reductase (XR) to reduce the hydrolyzed products of lactose (glucose and galactose) into sugar alcohols. Their metabolism leads to the accumulation of sugar phosphates, which are precursors for cofactor biosynthesis [28].

Materials:

- Strain: Engineered E. coli BL21(DE3) with your production pathway.

- Plasmid: Vector containing the XR gene from Hypocrea jecorina.

- Inducer: Lactose.

- Culture Media: Standard LB or defined minimal media.

Method:

- Strain Construction: Transform your production host with the plasmid carrying the XR gene.

- Culture Induction:

- Inoculate main culture and grow to mid-log phase.

- Induce protein expression by adding lactose (typical range 2–20 g/L) [28].

- Continue cultivation for a set period (e.g., 6 hours).

- Bioconversion Assay:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in a reaction buffer containing a high concentration of lactose (or other sugar carbon source) to serve as the substrate for the cofactor boosting system.

- Incubate to allow for product formation.

- Analysis: Measure product titer (e.g., fatty alcohols, alkane) using GC-MS or other appropriate methods and compare with a control strain without XR.

Expected Outcome: The XR/lactose system has been shown to increase productivities by 2-4 fold in various systems [28].

Protocol 2: Enhancing NADPH Supply via Pentose Phosphate Pathway Overexpression

Objective: To increase NADPH availability by overexpressing key enzymes in the oxidative PPP.

Background: The enzymes glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Gnd) are the primary generators of NADPH in the PPP.

Materials:

- Strain: Your production E. coli strain.

- Plasmids: Vectors for expressing zwf and gnd under an inducible promoter.

Method:

- Strain Engineering: Construct a strain overexpressing zwf and gnd. This can be done via chromosomal integration or using plasmids.

- Cultivation: Grow the engineered strain and control in parallel under production conditions.

- Validation and Production:

- Metabolomic Analysis: Use LC-MS to measure levels of PPP intermediates (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate, 6-phosphogluconate) to confirm increased flux.

- Product Measurement: Quantify the target product to assess yield improvement.

Expected Outcome: This strategy has successfully enhanced production of compounds like mevalonate and terpenes by ensuring an ample NADPH supply [27].

Data Presentation

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Cofactor Engineering on Bioproduction Yields

| Target Product | Host Organism | Cofactor Challenge | Engineering Strategy | Resulting Yield Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Alcohols | E. coli | NADPH, Acetyl-CoA demand | XR/Lactose Cofactor Boosting System | ~3-fold increase (from 58.1 to 165.3 μmol/L/h) | [28] |

| Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) | E. coli | NADH/NAD+ imbalance | Multiple strategies: NADH oxidase (SpNox), glycolytic enzyme swaps, protein engineering | Titer reached 676 mg/L in shake flask | [30] [31] |

| Theoretical Yields (Various) | E. coli & S. cerevisiae | NADPH limitation | Computational identification of optimal cofactor swaps (e.g., GAPD) | Increased theoretical maximum yield for many native and non-native products | [29] |

| Alkanes / Bioluminescence | E. coli | FAD, FMN, ATP demand | XR/Lactose Cofactor Boosting System | 2-4 fold increase in productivity | [28] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

XR Lactose Cofactor Boosting System

Bioproduction Yield Troubleshooting Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Cofactor Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Xylose Reductase (XR) | Reduces various sugars (glucose, galactose) to sugar alcohols, feeding into pathways that boost sugar phosphate and cofactor pools. | Core component of the versatile XR/lactose cofactor boosting system [28]. |

| NADH Oxidase (Nox) | Oxidizes NADH to NAD+, regenerating the oxidized cofactor and resolving reductive stress. | SpNox from S. pyogenes used to improve pyridoxine production in E. coli [30] [31]. |

| Cofactor Biosensors | Genetically encoded tools for real-time monitoring of intracellular cofactor ratios (e.g., NADPH/NADP+). | SoxR biosensor in E. coli or the NERNST ratiometric biosensor for dynamic regulation [27]. |

| Non-native GAPD Enzymes | Swaps cofactor specificity in glycolysis. gapC provides NADPH; gapN can reduce NADH production. | gapC from C. acetobutylicum expressed in E. coli to increase NADPH supply [29] [30]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise genome editing for gene knockouts, knock-ins, and promoter replacements. | Used for traceless genome editing in E. coli to delete competing genes or integrate pathway genes [31]. |

| 4-Tert-butyl-1-methyl-2-nitrobenzene | 4-Tert-butyl-1-methyl-2-nitrobenzene, CAS:62559-08-4, MF:C11H15NO2, MW:193.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-(azepane-1-carbonyl)benzoic acid | 2-(azepane-1-carbonyl)benzoic acid, CAS:20320-45-0, MF:C14H17NO3, MW:247.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Engineering Solutions: Strategic Approaches for NADPH and ATP Balance Control

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My FBA predictions show high product yields, but my experimental results reveal significant metabolite waste (e.g., acetate). What is the cause and how can I resolve it?

Answer: This discrepancy often arises from cofactor imbalance, where an excess of ATP or NAD(P)H generated by your engineered pathway is dissipated via native metabolic reactions, leading to by-product formation and reduced product yield [33].

- Root Cause: The FBA solution space is underdetermined, allowing for futile cofactor cycles with high flux. These are thermodynamically inefficient cycles where, for example, ATP is hydrolyzed without productive work, or cofactors are cycled to balance redox without contributing to growth or production [33].

- Solution:

- Implement a Co-factor Balance Assessment (CBA) Protocol: Systematically categorize all reactions producing or consuming ATP and NAD(P)H in your model. This helps identify if surplus cofactors are being diverted to by-product formation or maintenance instead of your target product [33] [34].

- Apply Manual Constraints: Based on experimental data (e.g., from 13C-MFA), manually constrain the fluxes of reactions identified as major contributors to futile cycling [33].

- Re-formulate the Objective Function: If biomass formation is the objective, the model may over-prioritize growth by using futile cycles to dump excess energy. Try setting the biosynthetic production as the primary objective to find solutions that minimize futile cycling [33].

FAQ 2: How can I account for uncertainty in biomass composition in my FBA model to improve cofactor balance predictions?

Answer: Uncertainty in the stoichiometric coefficients of the biomass reaction can propagate and affect the accuracy of flux predictions, including those related to cofactor balance [35].

- Root Cause: The biomass reaction is a major sink for ATP and reducing power. Incorrect coefficients can lead to misrepresentation of the energy and redox demands of growth, causing erroneous predictions of product yield and by-product formation [35].

- Solution:

- Apply Conditional Parameter Sampling: When assessing parameter uncertainty, always sample biomass coefficients in a way that maintains the total molecular weight of the biomass composition at 1 g mmolâ»Â¹. This ensures thermodynamic consistency [35].

- Enforce Elemental and Metabolite Pool Conservation: Impose constraints that conserve elements and metabolite pools, especially when modeling conditions that deviate from steady-state, to prevent unrealistic flux distributions [35].

FAQ 3: What strategies can I use to re-balance NADPH/NADP+ and ATP/ADP pools in an engineered pathway identified as imbalanced by CBA?

Answer: Computational identification of imbalance should be followed by biological re-engineering.

- Root Cause: A synthetic pathway may consume or produce cofactors in a ratio that is incompatible with the host's native metabolism, creating a redox or energy bottleneck [33] [23].

- Solution:

- Promoter Engineering: Fine-tune the expression of cofactor-dependent genes in your pathway to optimize flux and reduce imbalance [23].

- Protein Engineering: Modify enzyme specificity to switch cofactor preference (e.g., from NADH to NADPH) [23].

- Heterologous Enzyme Expression: Introduce alternative, better-balanced pathway variants or enzymes such as transhydrogenases or NADH kinases to regenerate the required cofactors [33] [23].

- Use Genetically Encoded Biosensors: Implement biosensors for ATP/ADP and NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ to monitor intracellular cofactor levels in real-time and guide your engineering efforts [36].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Co-factor Balance Assessment (CBA) Algorithm

This protocol details the steps to perform a CBA using a core E. coli stoichiometric model, as described in the primary literature [33].

1. Model Modification

- Objective: Introduce the reactions for your synthetic pathway into the host's metabolic model.

- Methodology:

- Use a well-curated model (e.g., the E. coli Core Model).

- Add necessary metabolites and reactions to enable the production of your target compound (e.g., butanol). Define an appropriate objective function, such as maximizing the flux through a target product sink reaction [33].

2. Flux Calculation

- Objective: Obtain a flux distribution for the network.

- Methodology:

- Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) or parsimonious FBA (pFBA) to simulate growth or production under defined conditions.

- Record the flux value (

v) for every reaction in the network [33].

3. CBA Flux Categorization

- Objective: Quantify the contribution of different metabolic processes to the cofactor pools.

- Methodology:

- For each cofactor (e.g., ATP, NADH, NADPH), identify all reactions that involve it.

- Categorize the fluxes of these reactions into five core categories based on their function [33] [34]:

- Cofactor Production: Reactions that generate the cofactor (e.g., ATP in glycolysis).

- Biomass Production: Cofactor consumed for growth.

- Target Production: Net cofactor flux from the introduced synthetic pathway.

- Waste Release: Cofactor flux associated with by-product secretion (e.g., acetate, lactate) or known "futile" cycles.

- Cellular Maintenance: Residual cofactor consumption not accounted for by the above.

The workflow for this protocol is standardized as follows:

Protocol 2: Minimizing Futile Cycles in FBA Predictions

This protocol outlines methods to reduce unrealistic futile cycling identified by the CBA [33].

1. Problem Identification

- Run the CBA protocol. A high flux in the "Waste Release" category, particularly through non-essential ATP-hydrolyzing or NAD(P)H-consuming reactions, indicates probable futile cycling [33] [34].

2. Applying Flux Constraints

- Objective: Manually constrain the model to eliminate unrealistic cycles.

- Methodology:

- Use experimental data from 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) to define physiologically plausible lower and upper bounds for specific reaction fluxes.

- Apply these constraints to your model and re-run the FBA and CBA [33].

3. Alternative Computational Approaches

- Objective: Use built-in algorithms to suppress loop formation.

- Methodology:

- Employ "loopless FBA" or related techniques that explicitly prohibit thermodynamically infeasible cyclic fluxes [33].

- Compare the results with the manually constrained model to identify a robust solution.

The logical process for troubleshooting futile cycles is as follows:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Cofactor Demand and Theoretical Yield of Butanol Production Pathways in E. coli

This table, adapted from a case study, summarizes how different pathway designs affect cofactor balance and theoretical yield [33].

| Model Name | Key Pathway Enzymes | Target Product | ATP Balance (Net) | NAD(P)H Balance (Net) | Relative Yield Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BuOH-0 | AtoB + CP + AdhE2 | Butanol | 0 | -4 | Medium |

| BuOH-1 | NphT7 + CP + AdhE2 | Butanol | -1 | -2 | Higher |

| tpcBuOH | Pathway from M. extorquens | Butanol | 0 | -2 | High |

| BuOH-2 | NphT7 + Ter + AdhE2 | Butanol | -1 | -4 | Lower |

| CROT | Crotonase | Crotonyl-CoA | -1 | 1 | Varies |

| BUTAL | Butyraldehyde dehydrogenase | Butyraldehyde | 0 | -2 | Varies |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cofactor Balance Studies

This table lists key reagents and computational tools essential for research in this field.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded ATP/ADP Biosensor | Real-time monitoring of intracellular ATP/ADP ratios in live cells [36]. | Enables dynamic tracking of energy status during production. |

| Genetically Encoded NAD(P)H Biosensor | Real-time monitoring of intracellular NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratios [36]. | Reveals redox challenges in engineered pathways. |

| E. coli Core Model | A simplified stoichiometric model of E. coli metabolism [33]. | Standard platform for implementing FBA and CBA algorithms. |

| Loopless FBA Algorithm | A variant of FBA that eliminates thermodynamically infeasible cyclic fluxes [33]. | Reduces prediction of unrealistic futile cycles. |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Experimental technique to measure intracellular metabolic fluxes [33]. | Provides data for constraining and validating FBA models. |

Protein Engineering for Cofactor Specificity Switching and Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is switching an enzyme's cofactor specificity from NADPH to NADH often desirable in metabolic engineering?

The primary motivation is cost and stability. NADH is generally less expensive and more stable than NADPH, making processes that rely on it more economical for large-scale applications like chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturing [37]. Furthermore, natural metabolic pathways in production hosts like E. coli or yeast often generate different ratios of these cofactors. Switching specificity allows you to balance cofactor pools within the cell, preventing a build-up of one cofactor and a shortage of another, which can enhance the flux through your engineered pathway and increase product yield [38] [39].

FAQ 2: When I successfully change my enzyme's cofactor preference, why does the catalytic efficiency often decrease, and how can I mitigate this?

A loss in catalytic efficiency is a common challenge because mutations in the cofactor-binding pocket can disrupt optimal geometry and interactions. You can mitigate this by using advanced protein engineering strategies:

- Loop Exchange: Replace entire loops in the cofactor-binding site rather than making single point mutations. This approach has generated some of the best results in terms of both specificity reversal and retained efficiency [38].

- Computational Design: Use algorithms to predict mutations that introduce favorable interactions with the new cofactor (e.g., introducing basic residues to bind NADPH's phosphate group) while minimizing structural disruption [38].

- Directed Evolution: After making initial rational mutations to switch specificity, perform iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening to select for variants that have regained high catalytic activity [37].

FAQ 3: What are the major sources of NADPH in a typical microbial cell that I can engineer to improve supply?

You can target several key pathways to enhance NADPH regeneration [1]:

- Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP): The oxidative phase is a major source. Overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) is a common strategy.

- TCA Cycle-related Enzymes: Cytosolic or mitochondrial isoforms of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1/IDH2) and malic enzyme (ME1/ME3) can be engineered for higher flux.

- Transhydrogenation: The membrane-bound transhydrogenase (PntAB) can be manipulated to shift the balance between NADH and NADPH.

- One-Carbon Metabolism: This pathway also contributes to NADPH generation in both the cytosol and mitochondria.

FAQ 4: Beyond switching cofactors, what other cofactor engineering strategies can I use?

A powerful alternative is "Cofactor Engineering of a Network's Cofactor Preference." Instead of re-engineering a single enzyme, you identify and replace multiple enzymes within your heterologous pathway with isofunctional enzymes that naturally possess the desired cofactor specificity. For example, to change a pathway from NADH- to NADPH-dependency, you can replace NADH-dependent enzymes with homologs that use NADPH, thereby creating a pathway that aligns with the host's native cofactor supply [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Cofactor Specificity Reversal

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No activity with new cofactor | Mutations completely disrupted cofactor binding pocket. | Verify binding pocket structure; try a different mutagenesis strategy like loop exchange [38]. |

| Severe loss of catalytic efficiency | Mutations suboptimally positioned, affecting transition state. | Employ directed evolution or computational design to improve efficiency after initial switch [38]. |

| Incomplete specificity switch | Mutations insufficient to overcome wild-type preference. | Introduce additional targeted mutations; analyze successful case studies for your enzyme class [38]. |

| Poor protein expression or stability | Mutations caused misfolding or aggregation. | Include protein stability predictions in design; use lower expression temperatures or chaperones. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Managing Cofactor Balance in Engineered Pathways

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low product titer despite high pathway enzyme expression | Cofactor imbalance (e.g., NADPH depletion). | Use genomic tools like CRISPRi to downregulate native NADPH-consuming genes [4]. |

| Accumulation of metabolic intermediates | Cofactor imbalance halting pathway flux. | Overexpress key enzymes from PPP (e.g., G6PDH) to boost NADPH supply [1]. |

| Reduced cell growth or viability | Engineering caused ATP/ADP or NADPH/NADP+ imbalance. | Use dynamic regulation systems (e.g., quorum-sensing) to downregulate ATP-consuming processes only at high cell density [4]. |

| Inability to monitor cofactor levels in vivo | Lack of real-time, non-destructive monitoring. | Employ genetically encoded biosensors for ATP/ADP or NADPH/NADP+ to track cofactor dynamics in live cells [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Rational Design Workflow for Switching Cofactor Specificity from NADPH to NADH

Methodology: This protocol outlines a standard rational design approach for cofactor engineering, based on a review of over 100 enzyme engineering studies [38].

Materials:

- Template: Wild-type enzyme structure (X-ray crystal structure preferred)

- Software: Molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL), computational protein design software (e.g., Rosetta)

- Strains: E. coli BL21(DE3) or similar for protein expression

- Reagents: Cofactors (NADPH, NADH), substrates, site-directed mutagenesis kit, chromatography media for protein purification

Procedure:

- Structural Analysis: Identify the cofactor-binding pocket in your enzyme structure, typically a Rossman fold. Note key residues that interact with the 2'-phosphate group of NADPH [38].

- Target Identification: pinpoint acidic (negatively charged) residues that form hydrogen bonds with the 2'- and 3'-hydroxyl groups of NADPH's adenine ribose. Also, look for residues that create a positively charged pocket to accommodate the phosphate [38].

- Mutagenesis Design:

- The general strategy is to remove acidic residues and incorporate basic residues.

- Common mutations involve substituting Asp or Glu for Ala, Ser, or Gly to eliminate repulsion against NADH.

- In some cases, introducing Arg or Lys can help form a hydrogen bond with the 2'-phosphate of NADPH if switching to NADPH preference [38].

- Generate Variants: Use site-directed mutagenesis to create the designed mutants.

- Expression & Purification: Express the mutant proteins in your host and purify them using affinity chromatography.

- Kinetic Characterization: Determine the kinetic parameters (

kcatandKm) for both the wild-type and mutant enzymes with both NADPH and NADH. Calculate the Coenzyme Specificity Ratio and Relative Catalytic Efficiency to quantify your success [38].

Protocol 2: CRISPRi Screening for Identifying Cofactor-Consuming Gene Targets (CECRiS)

Methodology: This protocol describes the Cofactor Engineering based on CRISPRi Screening (CECRiS) strategy used to identify native NADPH- and ATP-consuming genes whose repression improves product formation [4].

Materials:

- Strain: Production host (e.g., E. coli 4HPAA-2 from the study) containing your biosynthetic pathway.

- Plasmids: dCas9* plasmid and sgRNA-expression plasmids targeting NADPH-consuming or ATP-consuming genes.

- Media: Selective LB broth or defined production medium.

- Equipment: Shake flasks, bioreactor, HPLC or GC for product quantification.

Procedure:

- sgRNA Library Design: Design sgRNAs to bind the non-template strand ~100 bp downstream of the start codon of all target genes (e.g., 80 NADPH-consuming genes in E. coli) [4].

- Transformation: Co-transform the production strain with the dCas9* plasmid and individual sgRNA plasmids.

- Screening: Inoculate transformants into production medium in shake flasks. Monitor cell growth and product titer.

- Hit Identification: Identify strains where sgRNA repression leads to increased product yield without severely inhibiting growth. In the 4HPAA study, repression of

yahK(NADPH-consuming) andfecE(ATP-consuming) were identified as hits [4]. - Validation & Optimization: Delete or further repress the identified gene targets. For fine-tuning, implement dynamic regulation systems (e.g., quorum-sensing repressor system) to downregulate targets only at the optimal fermentation stage [4].

Performance Metrics for Cofactor Engineering

Quantitative Data from Protein Engineering Studies This table summarizes key performance indicators from a review of 103 enzyme engineering studies, providing benchmarks for your projects [38].

| Engineering Strategy | Success Rate (Specificity Reversed) | Avg. Coenzyme Specificity | Avg. Relative Catalytic Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loop Exchange | High | >1 | Highest among strategies |

| Rational Design (Single/Double Mutations) | Moderate | >1 | Often < 0.5 |

| Directed Evolution | Variable | Variable | Can be high after optimization |

| Computational Design | Emerging | >1 | Promising, often higher than rational design |

- Key Metrics Definitions [38]:

- Coenzyme Specificity Ratio:

(kcat/Km)NADP / (kcat/Km)NADwhen switching to NADP, or vice versa. A value >1 indicates success. - Relative Catalytic Efficiency:

(kcat/Km)mutant, desired cofactor / (kcat/Km)WT, natural cofactor. This measures how much efficiency was retained.

- Coenzyme Specificity Ratio:

Visualizations

Cofactor Engineering Workflow

Cofactor Specificity Switch Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | Enable real-time, non-destructive monitoring of intracellular ATP/ADP and NADPH/NADP+ ratios in live cells [36]. | e.g., iATPSnFR for ATP; Allows tracking of cofactor dynamics during fermentation. |

| CRISPRi/dCas9 System | Enables targeted repression (knock-down) of specific genes without complete knockout, ideal for studying essential ATP/NADPH-consuming genes [4]. | Used in CECRiS strategy to screen 80 NADPH- and 400 ATP-consuming genes in E. coli. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Standard kit for introducing specific point mutations into plasmid DNA for rational protein engineering. | Commercial kits available from suppliers like NEB or Agilent. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A mathematical modeling approach used to simulate and analyze metabolic fluxes, predicting the effect of genetic manipulations on cofactor balances and growth [39]. | Used to elucidate condition-dependent roles of enzymes like FBPase in cofactor metabolism. |

| 2-(4-Bromo-3-methoxyphenyl)acetonitrile | 2-(4-Bromo-3-methoxyphenyl)acetonitrile, CAS:113081-50-8, MF:C9H8BrNO, MW:226.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Pyridin-2-ylmethylideneamino)thiourea | (Pyridin-2-ylmethylideneamino)thiourea, CAS:3608-75-1, MF:C7H8N4S, MW:180.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How does a molecular purge valve function to maintain NADPH balance in a cell-free system?

A molecular purge valve is a synthetic biochemistry module designed to automatically maintain redox balance (NADPH/NADPâº) in engineered pathways where cofactor generation and utilization are unbalanced. It functions by creating a metabolic node that dissipates excess reducing equivalents while maintaining carbon flux.

Core Mechanism: The system typically employs a combination of enzymes with different cofactor specificities. For example, a purge valve may use both NADâº-utilizing (PDHNADH) and NADPâº-utilizing (PDHNADPH) pyruvate dehydrogenase enzymes, alongside a water-forming NADH oxidase (NoxE).

- Under Low NADPH Conditions: The NADPâº-utilizing enzyme is more active, generating NADPH to restore balance.

- Under High NADPH Conditions: The NADPâº-utilizing enzyme activity is choked off. The NADâº-utilizing enzyme takes over, producing NADH instead. The accompanying NADH oxidase (NoxE) then oxidizes this excess NADH to NADâº, effectively "purging" the excess reducing power and preventing a bottleneck. This allows carbon flux to continue unimpeded toward product synthesis [40] [41].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and logical relationships within a molecular purge valve system:

FAQ 2: What are the common issues when implementing a purge valve and how can they be resolved?

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Product Yield | Inefficient purge valve operation causing cofactor imbalance and metabolic bottleneck. | Optimize the ratio of PDHNADH, PDHNADPH, and NoxE enzymes. Titrate enzyme concentrations to find the optimal balance for your specific pathway [40]. |

| Enzyme Instability | Use of enzymes lacking sufficient stability for long-duration reactions. | Utilize thermostable enzymes (e.g., from Geobacillus stearothermophilus) or engineer enzymes for improved stability [40]. |

| Incomplete Cofactor Recycling | Spontaneous oxidation of NAD(P)H or suboptimal activity of the purge valve module. | Ensure the NADH oxidase (NoxE) is highly active and specific to prevent NADH buildup. The system should generate a slight excess of cofactors to account for gradual losses [40]. |

| Poor Pathway Flux | Thermodynamically unfavorable conditions or insufficient transport of substrates into synthetic compartments. | Select electron donors with favorable reduction potentials (e.g., formate, Hâ‚‚). For vesicle systems, incorporate specific membrane transporters for impermeable substrates [42]. |

FAQ 3: What quantitative performance data can be expected from a functional purge valve system?

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from foundational research on molecular purge valves.

| Application | Key Enzymes in Purge Valve | Cofactor Managed | Key Outcome / Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Bioplastic | PDHNADH, PDHNADPH, NoxE [40] | NADPH/NADP⺠| Enabled robust operation of the PHB synthesis pathway from pyruvate despite inherent cofactor imbalance [40]. |

| Isoprene Production | PDHNADH, PDHNADPH, NoxE [40] | NADPH/NADP⺠| Allowed for high-yield production (>95%) of isoprene from pyruvate via the mevalonate pathway by maintaining redox balance [40]. |

| General Synthetic Biochemistry | Engineered PDH variants, specific oxidases [40] [43] | NADPH/NADP⺠| System provides a >90% yield for target chemicals like biodegradable plastics by effectively decoupling cofactor production from carbon flux [44]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Purge Valve for PHB Production from Pyruvate

Objective: To construct a cell-free system that converts pyruvate to polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) using a molecular purge valve to maintain NADPH balance [40].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See the "Research Reagent Solutions" table below for essential materials.

- Buffer: Appropriate assay buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl or phosphate buffer, pH 7.0-8.0).

- Substrate: Pyruvate solution.

- Cofactors: NADâº, NADPâº.