Beyond E. coli: Engineering Host-Agnostic Genetic Devices to Revolutionize Biomedicine

Host-agnostic genetic device engineering represents a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, moving beyond traditional model organisms to create genetic systems that function predictably across diverse microbial and mammalian hosts.

Beyond E. coli: Engineering Host-Agnostic Genetic Devices to Revolutionize Biomedicine

Abstract

Host-agnostic genetic device engineering represents a paradigm shift in synthetic biology, moving beyond traditional model organisms to create genetic systems that function predictably across diverse microbial and mammalian hosts. This article explores the foundational principles of the 'chassis effect,' where identical genetic circuits exhibit different performances depending on their host organism. We examine methodological advances in creating broad-host-range tools, strategies for troubleshooting host-circuit interactions, and validation frameworks for comparing device performance. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis provides a comprehensive roadmap for developing predictable, robust genetic systems that leverage microbial diversity for applications in biomanufacturing, therapeutics, and diagnostic technologies.

The Chassis Effect: Why Host Context Matters in Genetic Engineering

Host-agnosticism represents a paradigm shift in genetic engineering, moving beyond the reliance on a narrow set of traditional model organisms like Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [1]. This approach reconceptualizes the host chassis not as a passive platform but as a tunable, integral design parameter that actively influences the behavior and performance of engineered genetic systems [1]. The core principle of host-agnosticism involves developing genetic tools, devices, and frameworks that maintain functionality and predictability across diverse microbial hosts, thereby expanding the biodesign space for biotechnology applications in biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutics [1].

The emergence of broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology addresses historical limitations in the field by treating host-context dependency as an opportunity rather than an obstacle [1]. This perspective enables researchers to leverage innate host capabilities—such as the photosynthetic machinery of cyanobacteria, the stress tolerance of extremophiles, or the specialized metabolic pathways of non-model organisms—as functional components within engineered biological systems [1].

Core Principles and Definitions

Host-agnosticism in genetic engineering is underpinned by several foundational principles that distinguish it from traditional single-host approaches. The framework emphasizes functional portability across diverse biological contexts while maintaining performance specifications and operational reliability.

Key Defining Characteristics:

- Separation of Genetic Logic and Host Context: Core genetic circuits are designed independently of host-specific cellular machinery, with standardized interfaces that buffer against host-specific variations [1] [2].

- Unified Modular Interfaces: Well-defined biological interfaces (promoters, RBS, terminators) enable genetic devices to connect predictably with different host environments [1].

- Standardized Performance Metrics: Quantitative measures of circuit behavior (expression levels, response times, stability) are maintained within acceptable tolerances across host platforms [1].

The conceptual foundation of host-agnosticism draws parallels from platform-agnostic frameworks in computer science, which employ adapter patterns and canonical intermediate representations to achieve functional equivalence across heterogeneous execution environments [2]. In biological terms, this translates to genetic designs that interact with host-specific resources (polymerases, ribosomes, metabolites) through standardized abstraction layers rather than direct, optimized connections that would tie functionality to a particular host.

Quantitative Framework for Host-Agnostic Design

Implementing host-agnostic approaches requires systematic quantification of how genetic devices perform across different hosts. The following parameters must be characterized to establish host-agnostic functionality:

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating Host-Agnostic Performance

| Performance Metric | Measurement Method | Target Tolerance Range | Impact of Host Variation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Strength | Fluorescence units/cell (e.g., GFP) | ≤20% coefficient of variation | High - depends on resource availability [1] |

| Response Time | Time to half-maximal output | ≤15% deviation from reference | Medium - influenced by metabolic state [1] |

| Growth Burden | Specific growth rate reduction | <10% impact on host growth | High - correlates with resource competition [1] |

| Signal Leakiness | Basal expression without induction | <5% of maximal expression | High - affected by transcriptional regulation [1] |

| Genetic Stability | Device function over generations | >95% retention after 50 generations | Medium - depends on host repair mechanisms |

Table 2: Host-Specific Factors Influencing Device Performance

| Host Factor | Impact on Genetic Devices | Compensation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Polymerase Abundance | Alters transcription rates; ±40% variation observed [1] | Promoter engineering; sigma factor selection |

| Ribosome Availability | Affects translation efficiency; ±35% variation [1] | RBS optimization; codon harmonization |

| Metabolic Burden Response | Triggers global regulation; highly variable [1] | Resource-aware design; dynamic regulation |

| Native Regulatory Networks | Causes crosstalk; host-specific [1] | Insulator sequences; orthogonal components |

Experimental Protocols for Host-Agnostic Implementation

Protocol 1: Cross-Host Characterization of Genetic Devices

Objective: Quantitatively evaluate the performance of a standardized genetic device across multiple microbial hosts to establish host-agnostic operating parameters.

Materials:

- Test Hosts: E. coli MG1655, Pseudomonas stutzeri, Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 [1]

- Genetic Device: SEVA-based expression vector with standardized origin of replication, antibiotic resistance, and GFP reporter [1]

- Growth Media: LB, M9 minimal media, host-specific optimal media

- Measurement Equipment: Plate reader with fluorescence capability, flow cytometer

Methodology:

- Vector Mobilization: Transform or conjugate the standardized genetic device into each test host using optimized protocols for each species.

- Growth Conditions: Culture all hosts in their respective optimal media at appropriate temperatures with biological triplicates.

- Time-Course Measurement:

- Measure OD600 and GFP fluorescence (ex485/em520) every 30 minutes for 24 hours

- Record growth parameters (lag time, doubling time, carrying capacity)

- Calculate device performance metrics (expression strength, response time, burden)

- Data Normalization: Normalize fluorescence values to cell count and compare absolute expression levels across hosts

- Statistical Analysis: Perform ANOVA with post-hoc testing to identify significant host-dependent variations in device performance

Troubleshooting:

- If transformation efficiency is low in non-model hosts, consider optimizing electroporation parameters or using broader-host-range conjugation systems

- If growth impairment exceeds 20%, consider reducing copy number or implementing inducible expression control

Protocol 2: Resource Allocation Profiling

Objective: Characterize host-specific resource reallocation patterns in response to genetic device expression to inform host-agnostic design principles.

Materials:

- Host Strains: E. coli BW25113, Halomonas bluephagenesis [1]

- Tools: RNA-seq kit, proteomics sample preparation materials, intracellular metabolite assay kits

- Equipment: Next-generation sequencer, LC-MS system, plate reader

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Culture hosts with and without genetic device expression under identical conditions

- Harvest samples at mid-exponential phase (OD600 = 0.6-0.8) in biological quadruplicates

- Multi-Omics Profiling:

- Transcriptomics: Extract total RNA, prepare sequencing libraries, sequence at minimum 20M reads/sample

- Proteomics: Perform whole-cell proteome extraction, tryptic digestion, LC-MS/MS analysis

- Metabolomics: Quench metabolism rapidly, extract intracellular metabolites, analyze via LC-MS

- Data Integration:

- Map sequencing reads to host genomes, quantify gene expression changes

- Identify differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05, fold-change > 2)

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis to identify resource bottlenecks

- Resource Competition Modeling:

- Apply constraint-based models (e.g., RBA, FBA) to predict resource limitations

- Correlate model predictions with experimental growth defects

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of host-agnostic genetic engineering requires specialized reagents and tools designed for cross-host compatibility:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Host-Agnostic Genetic Engineering

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Host Range | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEVA Vectors | Modular plasmid system [1] | >50 bacterial species | Standardized parts, interchangeable modules |

| Broad-Host-Range Promoters | Transcriptional initiation [1] | Diverse prokaryotes | Conserved recognition sequences, minimal host-specific factors |

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases | Reduce host interference [1] | Cross-species | Bacteriophage-derived, minimal crosstalk with host transcription |

| Universal RBS Libraries | Translation initiation control [1] | Multiple hosts | Sequence-decoupled from host-specific optimization |

| Host-Agnostic Reporters | Quantification of gene expression [1] | Broad compatibility | Fluorescent proteins with consistent folding across hosts |

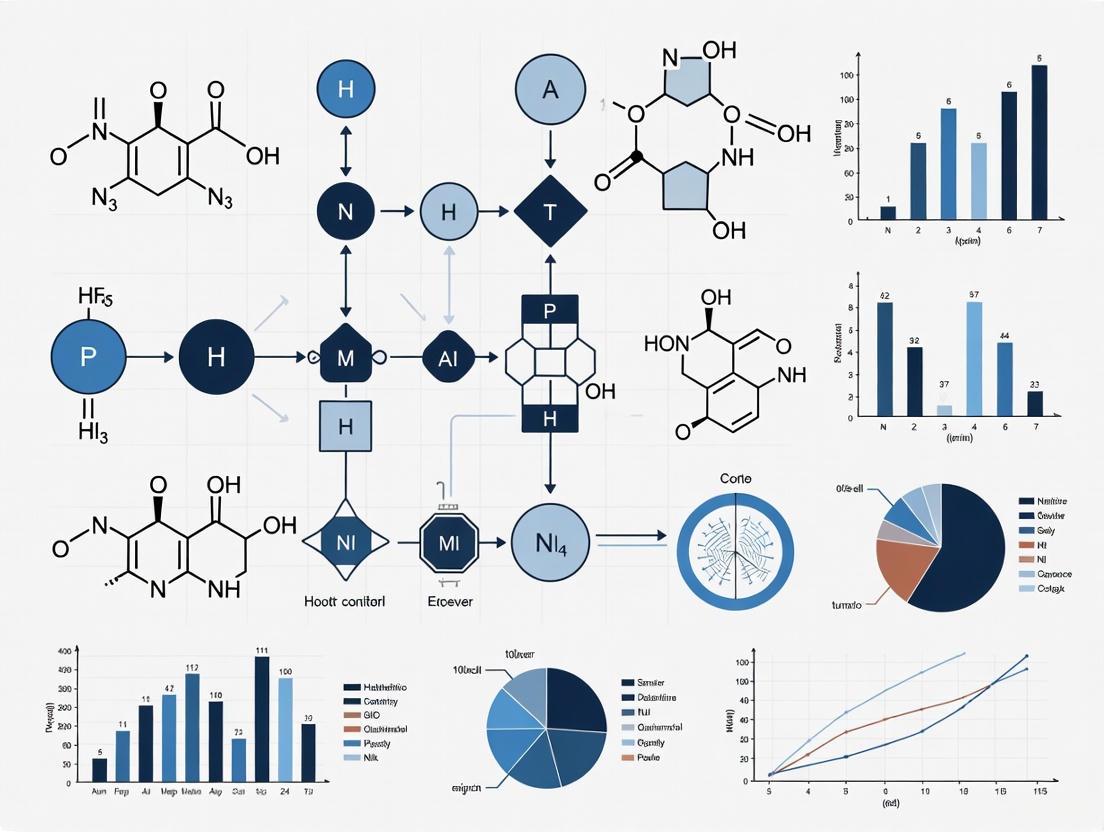

Visualization of Host-Agnostic Framework

The following diagrams illustrate key conceptual and operational aspects of host-agnostic genetic engineering using Graphviz DOT language:

Diagram 1: Traditional vs. Host-Agnostic Engineering Approaches

Diagram 2: Host-Agnostic Design and Validation Workflow

Application Notes for Drug Development

Host-agnostic approaches offer significant advantages for pharmaceutical applications, particularly in the production of complex therapeutic compounds that require specific folding, modification, or assembly that may be challenging in traditional hosts.

Case Study: GPCR Expression Platform

G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent a crucial class of drug targets, but their functional expression requires proper folding, post-translational modifications, and membrane trafficking that are often incompatible with bacterial systems [1]. A host-agnostic solution involves:

- Host Selection: Utilizing yeast species with native GPCR signaling pathways that can be modularized to accommodate human GPCRs [1]

- Standardized Characterization: Implementing uniform quantification methods for receptor localization, ligand binding, and signal transduction across host platforms

- Performance Benchmarking: Establishing minimum thresholds for receptor density, ligand affinity, and functional response to identify optimal host-device pairings

Implementation Protocol: Multi-Host Therapeutic Enzyme Production

Objective: Produce a human therapeutic enzyme with complex glycosylation patterns using a host-agnostic expression platform.

Methods:

- Host Screening: Test enzyme production in E. coli (non-glycosylating), S. cerevisiae (high-mannose glycosylation), and engineered P. pastoris (human-like glycosylation)

- Device Standardization: Implement identical expression cassettes with host-specific optimization limited to adapter modules (promoters, secretion signals)

- Quality Assessment: Measure enzyme activity, glycosylation pattern, stability, and immunogenicity for products from each host

- Host Selection: Choose optimal host based on integrated assessment of yield, quality, and production costs

Expected Outcomes: Identification of the most suitable host for specific therapeutic applications while maintaining the ability to rapidly transition production to alternative hosts if regulatory, safety, or scalability concerns arise with the primary host.

Host-agnosticism represents a maturing framework in genetic engineering that explicitly acknowledges and leverages host diversity as a design feature rather than treating it as experimental noise. The approaches outlined in this document provide researchers with standardized methodologies for developing genetic systems that function predictably across biological contexts, thereby accelerating the engineering of biological systems for pharmaceutical applications.

The future development of host-agnostic genetic engineering will likely focus on expanding the repertoire of standardized biological parts, improving computational models for predicting host-device interactions, and establishing more sophisticated adapter systems that can dynamically adjust device function based on host context. As these tools mature, host-agnostic approaches will become increasingly central to the efficient design and deployment of genetic technologies across diverse applications in drug development and therapeutic production.

The field of synthetic biology has traditionally relied on a narrow set of well-characterized model organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, primarily due to their genetic tractability and the availability of robust engineering toolkits [1]. However, this dependence on a limited number of hosts has constrained the design space available to synthetic biologists. Broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology has emerged as a modern subdiscipline that aims to expand this engineerable domain by incorporating non-traditional microbial hosts into the biodesign workflow [1]. A fundamental challenge in this expansion is the "chassis effect"—the phenomenon where identical genetic constructs exhibit different performances depending on the host organism in which they operate [1] [3].

The chassis effect demonstrates that the host organism is not merely a passive platform but an active component that significantly influences the function of engineered genetic systems [1]. This host-dependent behavior arises from complex interactions between introduced genetic circuitry and endogenous cellular processes, including resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [1]. Understanding and predicting these effects is crucial for advancing host-agnostic genetic device engineering, particularly for applications in biomanufacturing, therapeutic development, and environmental biotechnology where optimal host selection can dramatically impact system performance and productivity [1] [4].

Quantitative Analysis of Chassis-Dependent Circuit Performance

Documented Performance Variations Across Hosts

Recent empirical studies have systematically quantified how identical genetic circuits exhibit divergent behaviors across different microbial hosts. The following table summarizes key findings from comparative analyses of genetic circuit performance metrics:

Table 1: Performance Variations of Genetic Circuits Across Different Bacterial Hosts

| Host Organism | Circuit Type | Key Performance Metrics Affected | Observed Variation Range | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stutzerimonas spp. | Inducible Toggle Switch | Bistability, Leakiness, Response Time | Significant divergence correlated with gene expression patterns | Host-specific expression from shared core genome [1] |

| Gammaproteobacteria | Genetic Inverter | Output Signal Strength, Response Time, Growth Burden | Strong correlation with host physiological similarity | Specific bacterial physiology metrics [3] |

| Multiple Bacterial Species | Generic Circuits | Signal Strength, Response Time, Growth Burden, Expression Pathways | Spectrum of performance profiles | Resource allocation, metabolic interactions [1] |

Chassis Selection Criteria for Genetic Circuit Implementation

The selection of an appropriate chassis organism requires careful consideration of multiple biological and practical parameters. The following table outlines essential criteria for chassis evaluation in BHR synthetic biology applications:

Table 2: Chassis Selection Criteria for Broad-Host-Range Synthetic Biology Applications

| Selection Criterion | Importance Level | Evaluation Metrics | Ideal Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Compatibility | Critical | Precursor availability, Product-chassis compatibility | Native ability to produce similar compounds [4] |

| Genetic Tractability | High | Transformation efficiency, Genetic tool availability | Efficient DNA transfer, stable maintenance [1] |

| Growth Robustness | Medium-High | Doubling time, Burden tolerance | Robust growth across conditions [1] |

| Regulatory Element Compatibility | High | Sigma factor compatibility, Transcription machinery | Compatibility with regulatory elements [1] |

| Operational Context Suitability | Variable | Temperature, pH, salinity tolerance | Alignment with application environment [1] |

| Resource Allocation Patterns | High | RNA polymerase flux, Ribosome occupancy | Minimal resource competition with host processes [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing the Chassis Effect

Protocol 1: Cross-Species Circuit Performance Profiling

Objective: To quantitatively characterize the performance of an identical genetic circuit across multiple microbial hosts and identify host-specific factors influencing circuit behavior.

Materials:

- Plasmid System: Standardized genetic circuit (e.g., inverter or toggle switch) cloned into a BHR vector (e.g., SEVA system) [1]

- Host Strains: 6-8 diverse microbial hosts, preferably with sequenced genomes and varying phylogenetic relationships [3]

- Growth Media: Appropriate for all selected hosts, with identical composition for cross-comparison

- Analytical Equipment: Flow cytometer, plate reader, microfluidics system for single-cell analysis

Procedure:

- Strain Preparation: Transform the standardized genetic circuit into each host strain using optimal transformation protocols for each species. Confirm successful integration through PCR and sequencing.

- Culturing Conditions: Inoculate triplicate cultures of each strain in appropriate medium and incubate under optimal conditions for each host.

- Time-Course Monitoring: Measure circuit performance metrics (fluorescence output, growth rate) at 30-minute intervals over 12-24 hours using plate readers or automated sampling systems.

- Induction Experiments: For inducible circuits, apply standardized inducer concentrations at mid-exponential phase and monitor dynamic response.

- Single-Cell Analysis: Use flow cytometry to assess population heterogeneity and identify bimodal distributions in circuit output.

- Data Normalization: Normalize all fluorescence measurements against cell density and autofluorescence controls.

- Parameter Extraction: Calculate key performance parameters including response time, dynamic range, leakiness, and growth burden for each host.

Expected Outcomes: This protocol will generate a comprehensive dataset of circuit performance metrics across multiple hosts, enabling identification of host physiological traits that correlate with specific circuit behaviors [3].

Protocol 2: Host Physiology and Resource Allocation Analysis

Objective: To quantify host-specific physiological parameters and cellular resource availability that underpin observed chassis effects.

Materials:

- Cultivation System: Controlled bioreactors or multi-well plates with precise environmental control

- Analytical Tools: RNA sequencing capability, proteomics equipment, metabolite analyzers

- Reference Standards: Internal standards for absolute quantification of cellular components

Procedure:

- Growth Characterization: Cultivate each host strain containing the genetic circuit and measure growth kinetics (lag phase, exponential growth rate, carrying capacity) under standardized conditions.

- Transcriptome Analysis: Extract RNA from samples collected at mid-exponential phase and perform RNA sequencing to quantify transcriptional activity of native genes and circuit components.

- Proteome Profiling: Analyze proteome samples to determine absolute abundances of key cellular machinery (RNA polymerase, ribosomes, metabolic enzymes).

- Metabolite Quantification: Measure intracellular concentrations of central metabolites, nucleotide triphosphates, and amino acids.

- Resource Competition Assessment: Use dual-reporter systems to quantify competition for transcriptional and translational resources.

- Integration Analysis: Correlate physiological and molecular data with circuit performance metrics using multivariate statistical approaches.

Expected Outcomes: Identification of specific host factors (gene expression patterns, metabolic states, resource availability) that predict circuit performance and contribute to the chassis effect [1] [3].

Visualization of Chassis Effect Concepts and Experimental Workflows

Chassis Effect Mechanisms and Experimental Characterization

Diagram 1: Chassis Effect Mechanisms and Characterization

Host Selection and Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: Host Selection and Engineering Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Chassis Effect Studies

Essential Materials for Broad-Host-Range Genetic Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Chassis Effect Investigation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHR Vector Systems | SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture) Plasmids | Modular genetic constructs that function across multiple hosts | Standardized parts, origin of replication with broad host range [1] |

| Standardized Genetic Devices | Genetic Inverters, Toggle Switches | Benchmarking circuit performance across hosts | Well-characterized behavior, standardized measurement outputs [1] [3] |

| Host Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas Systems, ExoCET Technology | Genetic manipulation of non-model hosts | Enables gene knockouts, precise integrations in diverse bacteria [4] |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent Proteins (GFP, RFP), Enzymatic Reporters | Quantification of circuit performance | Standardized measurement, compatibility across hosts [1] |

| Analytical Tools | Flow Cytometry, RNA Sequencing, LC-MS | Multi-omics characterization of host-circuit interactions | Provides comprehensive view of host physiology and resource state [1] [3] |

Case Study: Streptomyces Chassis for Polyketide Production

Implementation of a Specialized Chassis for Natural Product Synthesis

The strategic selection and engineering of microbial chassis is exemplified by recent work developing Streptomyces aureofaciens as a versatile platform for type II polyketide (T2PK) production [4]. This case study demonstrates several key principles of chassis selection and engineering to minimize negative chassis effects while enhancing desired functionalities.

Initial Host Screening and Selection:

- Comparative Analysis: Multiple Streptomyces strains were evaluated as potential hosts for T2PK production, including model chassis (S. albus J1074, S. lividans TK24) and industrial producers (S. aureofaciens J1-022, S. rimosus) [4].

- Selection Criteria: Key considerations included genetic tractability, fermentation cycle duration, precursor availability, and native capacity for similar compound production [4].

- Performance Assessment: Heterologous expression of oxytetracycline (OTC) biosynthetic gene cluster revealed stark differences, with model chassis producing no detectable compounds while S. aureofaciens demonstrated efficient production [4].

Chassis Engineering Strategy:

- Precursor Competition Mitigation: In-frame deletion of two endogenous T2PK gene clusters created a pigmented-faded host (Chassis2.0) with reduced competition for native resources [4].

- Performance Validation: The engineered chassis showed 370% increase in OTC production compared to commercial strains and successfully produced diverse T2PK structures including tri-ring and penta-ring polyketides [4].

Key Findings and Implications:

- Product-Chassis Compatibility: Industrial high-yield strains demonstrate enhanced potential as chassis for heterologous production of structurally similar natural products [4].

- Engineering Efficiency: Strategic removal of competing pathways dramatically improved heterologous production without requiring multiple rounds of metabolic engineering [4].

- Platform Versatility: A single engineered chassis successfully produced diverse structural classes of target compounds, demonstrating the value of specialized chassis development [4].

This case study illustrates how systematic chassis selection and targeted engineering can overcome limitations posed by chassis effects, enabling efficient production of diverse valuable compounds while providing a framework for host selection in other biotechnological applications.

The contemporary landscape of synthetic biology has been predominantly shaped by work in a limited number of model organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. While these domesticated chassis are genetically tractable, their pervasive use constrains the field's potential by ignoring the vast metabolic and physiological diversity found in the microbial world [5]. Broad-host-range synthetic biology emerges as a strategic response to this limitation, aiming to expand the engineerable domain beyond traditional model systems. However, as genetic devices are transferred across diverse hosts, they exhibit significantly different performances—a phenomenon termed the "chassis effect" [5] [3]. This application note frames the pressing need for host-agnostic genetic device engineering within the context of this chassis effect, providing researchers with standardized protocols and analytical frameworks to systematically quantify and predict device performance across phylogenetically diverse microbial hosts.

The Chassis Effect: Quantifying Host-Dependent Device Performance

Experimental Demonstration of Host-Specific Circuit Behavior

A foundational study systematically characterized the performance dynamics of a genetic inverter circuit across six Gammaproteobacteria species, including both model and non-model hosts [5] [3]. The research employed a standardized genetic inverter circuit (plasmid pS4) responsive to l-arabinose (Ara) and anhydrotetracycline (aTc), enabling quantitative comparison of circuit performance across different host contexts.

Key Findings:

- Identically engineered genetic circuits exhibited significantly different input-output dynamics and performance metrics depending on the host organism [5].

- Hosts with more similar physiological profiles (growth metrics, molecular physiology) demonstrated more similar inverter performances, regardless of phylogenomic relatedness [5] [3].

- Specific bacterial physiological parameters, rather than evolutionary relationships, proved to be better predictors of genetic device functionality [5].

Comparative Host Physiology and Circuit Performance Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of host physiology and genetic inverter performance across six Gammaproteobacteria [5]

| Host Organism | Max Growth Rate (h⁻¹) | Stationary Phase OD₆₀₀ | Inverter Dynamic Range | Inverter Leakiness | Host Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 0.92 | 2.41 | 145-fold | 0.8% | Model |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | 0.58 | 1.89 | 98-fold | 2.3% | Non-model |

| Halopseudomonas oceani | 0.47 | 1.62 | 76-fold | 3.7% | Non-model |

| Halopseudomonas aestusnigri | 0.51 | 1.73 | 82-fold | 3.1% | Non-model |

| Pseudomonas putida | 0.61 | 1.95 | 105-fold | 1.9% | Model |

| Additional Gammaproteobacterium | 0.53 | 1.68 | 79-fold | 3.4% | Non-model |

Table 2: Correlation analysis between host physiology and circuit performance parameters [5]

| Physiological Parameter | Correlation with Dynamic Range | Correlation with Leakiness | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Growth Rate | R² = 0.89 | R² = -0.84 | p < 0.01 |

| Stationary Phase OD | R² = 0.82 | R² = -0.79 | p < 0.05 |

| Ribosomal Protein Abundance | R² = 0.76 | R² = -0.71 | p < 0.05 |

| Molecular Crowding Index | R² = 0.69 | R² = -0.65 | p < 0.05 |

Application Notes: Protocol for Cross-Host Genetic Circuit Characterization

Experimental Workflow for Multi-Host Circuit Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for analyzing genetic circuit performance across diverse microbial hosts:

Detailed Methodologies

Genetic Circuit Assembly via BASIC Method

Principle: Biopart Assembly Standard for Idempotent Cloning (BASIC) enables modular, one-pot assembly of genetic circuits from standardized DNA parts [5].

Protocol:

- DNA Part Preparation: Amplify or synthesize genetic parts (promoters, RBS, coding sequences, terminators) with standardized BASIC prefix and suffix sequences.

- Restriction-Ligation Reaction:

- Combine DNA parts with BsaI-HFv2 restriction enzyme and T4 DNA ligase

- Reaction conditions: 37°C for 1-2 hours, followed by 50°C for 5 minutes

- Use Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS beads for reaction purification

- Assembly Verification: Transform assembled circuit into E. coli DH5α, verify by colony PCR with LMP-F and LMS-R primers [5]

Critical Considerations:

- Ensure all genetic parts are in BASIC format with compatible linkers

- Include appropriate antibiotic resistance markers for selection

- Verify assembly by Sanger sequencing before cross-host transformation

Host Transformation via Electroporation

Principle: Efficient plasmid introduction into diverse bacterial hosts using optimized electrical field conditions [5].

Protocol:

- Competent Cell Preparation:

- Grow 5 ml overnight culture in LB medium at 30°C

- Dilute 1:1 with fresh LB, incubate 1 hour for recovery

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (4,000 rpm, room temperature)

- Wash twice with sucrose electroporation buffer (300 mM sucrose, 1 mM MgCl₂, pH 7.2)

- Resuspend in 80 μl electroporation buffer

- Electroporation:

- Incubate cells with 50-100 ng plasmid (15 minutes, room temperature)

- Transfer to 1-mm gap electroporation cuvette

- Electroporate at 1,250 V (150 resistance, 36 capacitance)

- Immediately add 750 μl LB, transfer to 5 ml LB for recovery

- Incubate with shaking for 2 hours at 30°C

- Plate on selective agar, verify transformants by colony PCR [5]

Host-Specific Modifications:

- For Halopseudomonas species: Use 5 ml culture per transformation

- Optimize recovery time based on host doubling time

- Adjust antibiotic concentrations based on host susceptibility

Standardized Cultivation and Induction Assay

Principle: Controlled environmental conditions enable direct comparison of circuit performance across physiologically diverse hosts [5].

Protocol:

- Cultivation Conditions:

- Use black, flat clear-bottom 96-well plates

- Inoculate 199 μl LB + antibiotic with 1 μl overnight culture

- Seal plates with breathable film (Breathe-Easy)

- Continuous measurement in plate reader (OD600, sfGFP: 485/515 nm, mKate: 585/615 nm)

- Maintain temperature at 30°C with continuous linear shaking

- Induction Protocol:

- Prepare stock solutions: 1 M l-arabinose (aqueous), 1 mg/ml aTc (in 70% ethanol)

- Titrate inducer concentrations across appropriate range

- Measure fluorescence and growth continuously for 42 hours

- Include technical and biological replicates for statistical power [5]

Data Analysis Framework

Multivariate Statistical Approaches:

- Calculate Euclidean distance matrices for physiology and performance parameters

- Generate phylogenomic distance matrix from genomic sequences

- Perform Mantel tests for correlation between distance matrices

- Use Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) for dimensionality reduction

- Apply Procrustes Superimposition to compare multivariate spaces [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for broad-host-range synthetic biology

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Host Range Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly Standard | BASIC, Golden Gate, SEVA | Modular genetic circuit assembly | Standardized parts enable cross-host testing |

| Reporter Systems | sfGFP, mKate, luxCDABE | Quantitative device performance | Codon-optimize for GC-rich hosts |

| Inducer Systems | l-Arabinose, aTc, AHL | Controlled gene expression | Test inducer uptake/processing in novel hosts |

| Selection Markers | KanR, AmpR, CmR | Plasmid maintenance | Determine minimal inhibitory concentrations |

| Vector Backbones | pSEVA231, pBBR1, RSF1010 | Broad-host-range replication | Match ori to host compatibility |

| Electroporation Buffer | Sucrose (300 mM), MgCl₂ (1 mM) | Cell competence preparation | Optimize ionic strength for marine bacteria |

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Predictive Framework for Circuit Performance

The integration of computational modeling with experimental validation provides a powerful approach for predicting chassis effects. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between host context and genetic circuit performance:

Computational Tools:

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): Predicts steady-state metabolic fluxes compatible with circuit function [6]

- Enzyme Cost Minimization (ECM): Estimates optimal enzyme allocation for synthetic pathways [6]

- Minimum-Maximum Driving Force (MDF): Identifies thermodynamically favorable pathway configurations [6]

Emerging Frontiers and Risk Assessment

AI-Driven Biodesign and Associated Hazards

The convergence of artificial intelligence with synthetic biology presents both opportunities and challenges for broad-host-range engineering [7]. AI-driven protein design enables creation of novel functional modules beyond evolutionary constraints, while introducing new dimensions of unpredictability in heterologous hosts [8].

Data Hazard Assessment:

- Reinforces Existing Bias: Over-reliance on model organisms creates datasets that poorly represent biological diversity [9]

- Difficult to Understand: Deep learning models for biological prediction lack interpretability [9]

- High Environmental Impact: Computationally intensive AI training has significant carbon footprint [9]

- Capable of Direct Harm: Democratization of design tools raises dual-use concerns [7]

Sustainable Bioprocess Considerations

Expanding the engineerable domain enables utilization of non-model hosts with specialized metabolic capabilities, particularly for C1 assimilation (methanol, formate, CO₂) [6]. Life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis at early research stages can guide host selection toward environmentally sustainable and economically viable bioprocesses [6].

The systematic expansion of synthetic biology's engineerable domain through broad-host-range approaches represents a paradigm shift from organism-specific to host-agnostic genetic design. By adopting standardized experimental frameworks, computational modeling, and comprehensive risk assessment, researchers can harness microbial diversity while mitigating the unpredictability introduced by chassis effects. The protocols and analytical approaches outlined herein provide a foundation for advancing host-agnostic genetic device engineering, ultimately enabling more robust and predictable biodesign across the microbial tree of life.

A primary challenge in broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology is the chassis effect, where an identically engineered genetic circuit exhibits different performance characteristics depending on the host organism it operates within [5] [1]. This effect complicates the predictable transfer of genetic devices from model organisms like Escherichia coli to novel, non-model hosts with advantageous phenotypic traits [1]. A critical question thus emerges: which host characteristic provides greater predictive power for genetic circuit performance—phylogenomic relatedness or host physiology? This Application Note addresses this question directly, presenting a structured framework for evaluating chassis effects and summarizing key findings from a systematic investigation across Gammaproteobacteria. The data demonstrate that specific bacterial physiology, rather than evolutionary lineage, is a more robust predictor of genetic inverter circuit performance, providing a strategic guideline for host selection in BHR synthetic biology applications [5].

Quantitative Comparison of Predictors

A comparative study using a genetic inverter circuit (responsive to l-arabinose and anhydrotetracycline) quantified its performance across six Gammaproteobacteria species. The interplay between phylogenomic distance, physiological similarity, and circuit performance similarity was analyzed using Euclidean distance matrices and Mantel tests [5].

Table 1: Correlation between Host Similarity and Genetic Circuit Performance Similarity

| Similarity Metric | Correlation with Circuit Performance Similarity | Statistical Significance (Mantel Test) |

|---|---|---|

| Host Physiology | Stronger, Positive Correlation | Significant |

| Phylogenomic Relatedness | Weaker Correlation | Not Significant |

The analysis revealed that hosts exhibiting more similar metrics of growth and molecular physiology also exhibited more similar performance of the genetic inverter. This correlation was statistically significant, indicating that specific bacterial physiology underpins measurable chassis effects [5]. In contrast, phylogenomic relatedness was a less reliable predictor of circuit behavior [5].

Key Physiological Metrics Underpinning the Chassis Effect

The host-dependent nature of circuit performance is linked to core physiological and molecular metrics. These factors collectively influence the cellular resources available for the operation of exogenous genetic circuits.

Table 2: Key Host Physiology Metrics Impacting Genetic Circuit Performance

| Physiological Metric | Impact on Circuit Function | Experimental Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Host Growth Rate | Couples with gene expression dynamics and burden [5] [10] | OD600 measurements during balanced growth in a plate reader [5] |

| Transcription/Translation Resource Availability | Determines polymerase/ribosome flux, affecting expression [1] [10] | Resource-aware kinetic models [10] |

| Gene Copy Number & Burden | Affects plasmid stability and expression load [5] [11] | qPCR; growth rate monitoring post-circuit induction [11] |

| Codon Usage Bias | Impacts translation efficiency of heterologous genes [5] | Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) analysis of circuit sequences |

| Metabolic State & Resource Allocation | Determines energy/precursor availability for circuit operation [10] [12] | Metabolite profiling; kinetic models of proteome partitioning [10] |

Experimental Protocol: Systematically Quantifying the Chassis Effect

This protocol details the methodology for comparing genetic circuit performance across multiple bacterial hosts, from chassis preparation to data analysis.

Chassis Preparation and Transformation

Objective: To introduce the standardized genetic circuit into diverse host backgrounds. Materials:

- Host Strains: Six Gammaproteobacteria (e.g., E. coli, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Halopseudomonas species) [5].

- Genetic Circuit: Plasmid pS4, an l-arabinose (Ara)- and anhydrotetracycline (aTc)-inducible inverter circuit assembled via BASIC assembly with a kanamycin resistance marker [5].

- Media: Lysogeny broth (LB).

- Equipment: Electroporator, 1-mm gap electroporation cuvettes, incubator.

Procedure:

- Culturing: Inoculate 5 mL of LB medium with a single colony of each wild-type host strain. Culture overnight at 30°C with shaking.

- Preparation of Electrocompetent Cells:

- Sub-culture 5 mL of overnight culture by diluting 1:2 with fresh LB medium. Incubate for 1 hour.

- Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation (e.g., 4,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature).

- Discard supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in sucrose electroporation buffer (300 mM sucrose, 1 mM MgCl₂, pH 7.2).

- Repeat the wash step a total of two times.

- Finally, resuspend the cell pellet in 80 μL of electroporation buffer.

- Electroporation:

- Incubate 80 μL of competent cells with 50-100 ng of plasmid pS4 at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Transfer the cell-DNA mixture to a pre-chilled 1-mm electroporation cuvette.

- Electroporate using an exponential decay wave electroporation system (e.g., 1,250 V, 150 resistance, 36 capacitance).

- Recovery and Selection:

- Immediately add 750 μL of LB medium to the electroporated cells and transfer the entire volume to 5 mL of fresh LB.

- Incubate with shaking for 2 hours at 30°C to allow for recovery and expression of the antibiotic resistance marker.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and streak onto LB agar plates containing 100 μg/mL kanamycin.

- Incubate plates for 24-48 hours at 30°C until colonies form.

- Verify successful transformation by colony PCR using primers LMP-F and LMS-R [5].

Circuit Performance Assay and Physiology Profiling

Objective: To simultaneously measure genetic circuit dynamics and host physiology under standardized conditions. Materials:

- Inducers: 1 M l-arabinose (aqueous, filter-sterilized), 1 mg/mL anhydrotetracycline hydrochloride (in 70% ethanol).

- Equipment: Black, flat-clear-bottom 96-well plates, plate reader capable of continuous measurement of OD600, GFP (485/515 nm), and mKate (585/615 nm) fluorescence, breathable sealing film.

Procedure:

- Experimental Setup:

- Prepare a range of induction conditions in the 96-well plate, including uninduced controls and gradients of Ara and aTc.

- In each well, mix 199 μL of LB with 100 μg/mL kanamycin with the appropriate inducers.

- Cultivation and Measurement:

- Inoculate each well with 1 μL of verified overnight culture of the circuit-carrying strains.

- Seal the plate with a breathable film.

- Load the plate into a pre-warmed (30°C) plate reader.

- Initiate a continuous measurement cycle for up to 42 hours with continuous linear shaking. Measure OD600, sfGFP, and mKate fluorescence at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-15 minutes) [5].

- Data Processing:

- Normalize fluorescence readings by subtracting the average blank value (media only) and dividing by the OD600 value to account for cell density.

- For the inverter circuit, plot the normalized GFP and mKate fluorescence over time for each induction condition and host to generate performance curves (transfer functions).

Data Analysis Framework

Objective: To quantitatively compare circuit performance and its relationship to host physiology and phylogeny. Procedure:

- Define Performance Metrics: Extract key parameters from the performance curves, including:

- Output Signal Strength: Maximum expression level.

- Response Time: Time to reach 50% of maximum output.

- Leakiness: Output level in the "OFF" state.

- Dynamic Range: Ratio between "ON" and "OFF" states.

- Construct Distance Matrices:

- Circuit Performance Distance: Calculate a Euclidean distance matrix based on the standardized performance metrics for all host pairs.

- Physiological Distance: Calculate a Euclidean distance matrix based on key physiological metrics (e.g., growth rate, molecular physiology) for all host pairs.

- Phylogenomic Analysis:

- Construct a phylogenomic tree based on whole-genome sequences of the host strains.

- Convert this phylogeny into a phylogenomic distance matrix.

- Statistical Correlation:

- Use the Mantel test to perform pairwise correlation testing between the circuit performance distance matrix and the physiological distance matrix, and between the circuit performance matrix and the phylogenomic distance matrix [5].

- A significant correlation between physiology and performance, but not phylogeny and performance, indicates physiology is the better predictor.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the core experimental and analytical process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| BHR Genetic Circuit Vectors | Standardized vehicle for genetic device across hosts. | Plasmid pS4 (Ara/aTc-inducible inverter); Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) vectors with BHR origins of replication [5] [1]. |

| Modular Genetic Parts | Functional components for circuit construction. | BASIC assembly standard parts; Synthetic promoters (e.g., pTet, pAra); Reporter proteins (sfGFP, mKate) [5] [13]. |

| Electroporation System | Physical method for plasmid DNA introduction into diverse bacteria. | Sucrose-based electroporation buffer; Exponential decay wave electroporator (e.g., 1,250 V, 1-mm cuvettes) [5]. |

| Multi-Mode Plate Reader | Parallel, continuous monitoring of circuit performance and host growth. | Measures OD600, fluorescence (e.g., 485/515 nm for GFP, 585/615 nm for mKate) in 96-well format over time [5] [11]. |

| Quantitative Modeling Software | Predict circuit performance and rationalize chassis effects. | "Resource-aware" kinetic models (e.g., ODE models in iBioSim) accounting for resource competition [10] [11]. |

Visualizing the Core Finding: Physiology Over Phylogeny

The central finding—that physiological similarity predicts circuit performance better than phylogeny—can be conceptualized as a realignment of the host selection paradigm, as illustrated below.

This Application Note provides compelling evidence that host physiology is a more reliable predictor of genetic circuit performance than phylogenomic relatedness. The experimental and analytical framework outlined here enables researchers to move beyond phylogenetic assumptions and instead select chassis based on quantifiable physiological metrics such as growth rate and resource availability. By adopting this physiology-first strategy, scientists can enhance the predictability, robustness, and functional success of engineered genetic systems across diverse microbial hosts, ultimately accelerating the application of synthetic biology in biomanufacturing, therapeutics, and environmental remediation [5] [1] [12].

The foundational vision of synthetic biology has been to engineer biological systems with the predictability and reliability of other engineering disciplines, treating genetic parts as modular, off-the-shelf components. However, the reality is that synthetic gene circuits do not operate in isolation; their functionality is inextricably linked to their host environment. This phenomenon, known as host dependence, has traditionally been viewed as a significant obstacle, leading to lengthy design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycles and poor predictability when circuits are deployed in new contexts [14]. Rather than treating this context dependence as a nuisance to be minimized, a paradigm shift is emerging: reframing host dependence as a critical design parameter that can be understood, modeled, and exploited to create more robust and predictable biological systems.

This reframing is occurring within the broader research context of host-agnostic genetic device engineering, which seeks to develop genetic systems that function predictably across diverse cellular chassis. The central challenge is that circuits interact with their hosts through complex feedback mechanisms, primarily growth feedback and resource competition [14]. When a synthetic circuit consumes host resources such as RNA polymerase (RNAP), ribosomes, nucleotides, and energy, it creates cellular burden, which slows host growth. This reduced growth rate, in turn, alters the dynamics of the circuit itself, creating an interconnected system where circuit and host behavior are mutually dependent [14]. By moving from a circuit-centric to a host-aware design perspective, researchers can transform these challenges into opportunities for creating more sophisticated and reliable synthetic biological systems.

Understanding Host-Circuit Interactions: Mechanisms and Impacts

Classification of Contextual Factors

Host-circuit interactions can be categorized into distinct types, each with different mechanisms and effects on circuit performance. Understanding these categories is essential for developing appropriate mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Types of Contextual Factors in Synthetic Gene Circuits

| Factor Type | Definition | Key Mechanisms | Impact on Circuit Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Contextual Factors | Factors that independently influence gene expression based on specific component choices. | Gene part selection, orientation (convergent, divergent, tandem), sequence syntax [14]. | Alters baseline expression levels; can be optimized through component selection. |

| Feedback Contextual Factors | Systemic properties emerging from complex circuit-host interplay. | Growth feedback, resource competition [14]. | Creates emergent dynamics (e.g., bistability, oscillations); not addressable through component-level optimization alone. |

| Growth Feedback | Reciprocal interaction between circuit activity and host growth rate. | Cellular burden from resource consumption reduces growth; slower growth decreases dilution of circuit components [14]. | Can create or eliminate steady states (e.g., emergence/loss of bistability) [14]. |

| Resource Competition | Conflict between multiple circuit modules or between circuit and host for limited cellular resources. | Competition for transcriptional/translational resources (RNAP, ribosomes), shared transcription factors, degradation machinery [14]. | Couples expression of unrelated genes; can lead to unintended correlations and performance degradation. |

Quantitative Impacts of Host Dependence

The effects of host-circuit interactions are not merely theoretical; they manifest in measurable, quantitative changes to system behavior that can significantly impact circuit functionality.

Table 2: Quantitative Impacts of Host-Circuit Interactions

| Interaction Type | Experimental System | Measurable Impact | Engineering Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Feedback | Self-activation switch with non-cooperative promoter | Emergent bistability due to cellular burden [14]. | A monostable circuit can become bistable; simple models fail to predict complex behavior. |

| Growth Feedback | Bistable self-activation switch | Loss of high-expression ("ON") state due to increased protein dilution [14]. | Designed circuit functions (e.g., memory) can be lost in certain host contexts. |

| Resource Competition | Multi-module genetic circuits in bacteria | Coupling of supposedly independent modules through competition for translational resources (ribosomes) [14]. | Violation of modularity assumption; circuit modules cannot be designed independently. |

| Resource Competition | Multi-module genetic circuits in mammalian cells | Competition primarily for transcriptional resources (RNAP) rather than translational resources [14]. | Different mitigation strategies needed for different host types (bacterial vs. mammalian). |

Application Note: Host-Aware Circuit Design Framework

Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Modeling

A host-aware design approach requires mathematical frameworks that explicitly incorporate circuit-host interactions rather than treating the host as a passive backdrop. The most comprehensive models consider three interconnected nodes: the circuit, the host's transcriptional/translational resources, and host growth [14]. This framework can be represented by a system of equations that capture the essential relationships:

- Circuit Operation consumes free resources, creating cellular burden

- Resource Pools stimulate circuit protein production and host growth

- Host Growth upregulates cellular resources while diluting circuit components

These interactions create feedback loops that can be modeled using ordinary differential equations or, for stochastic effects, using Markovian approaches [15]. The Mean Objective Cost of Uncertainty (MOCU) framework provides a particularly valuable approach for quantifying how uncertainty about host interactions degrades circuit performance, enabling objective-based experimental design to reduce the most performance-critical uncertainties [15].

Protocol 1: Characterizing Host-Dependent Effects

Objective: Systematically quantify context-dependent effects of host environment on synthetic gene circuit performance.

Background: Understanding the specific nature and magnitude of host-circuit interactions is the essential first step in reframing host dependence as a design parameter. This protocol provides a standardized methodology for characterizing these effects across different host strains and growth conditions.

Materials:

- Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Host-Circuit Characterization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP, YFP), enzymatic reporters (β-galactosidase, luciferase) | Quantitative measurement of circuit output and dynamics [14]. |

| Host Strains | Isogenic host variants, different bacterial species (E. coli, B. subtilis), engineered strains with resource perturbations | Testing circuit performance across diverse genetic and physiological contexts [14]. |

| Resource Monitoring Tools | RNAP tracking tags, ribosome profiling, ATP monitoring assays | Direct measurement of resource availability and utilization [14]. |

| Growth Monitoring Systems | OD600 spectrophotometry, flow cytometry for cell counting, microfluidic microscopy | Continuous monitoring of host growth dynamics and correlation with circuit performance [14]. |

| Genetic Perturbation Tools | CRISPRi, transposon mutagenesis, RNA interference | Targeted manipulation of host factors to test specific interaction hypotheses [14]. |

Experimental Workflow:

Procedure:

Host Panel Selection:

- Select 3-5 phylogenetically diverse host strains with differing growth characteristics and resource allocation patterns

- Include both natural isolates and engineered laboratory strains to capture a range of physiological states

- For mammalian systems, select different cell lines with varying metabolic and transcriptional profiles

Reporter Circuit Engineering:

- Construct identical genetic circuits with standardized fluorescent reporters in appropriate vectors for each host

- Include appropriate control circuits (constitutive promoters, null constructs) to establish baseline measurements

- Implement the circuit in at least two different copy number contexts (low-copy plasmid, high-copy plasmid, chromosomal integration) to test gene dosage effects

Multi-scale Parameter Measurement:

- Inoculate parallel cultures of each host-circuit combination in triplicate

- Measure circuit output (fluorescence), host growth (OD600 or cell counts), and resource levels at 30-minute intervals throughout growth

- For resource measurement, collect samples for RNA sequencing (transcriptional resources) and ribosome profiling (translational resources) at mid-log phase

- Extend measurements to stationary phase to capture phase-dependent effects

Resource Competition Assay:

- Introduce a second, orthogonal circuit with different resource demands to test resource coupling between circuits

- Measure how the presence of the competing circuit affects the performance of the primary reporter circuit

- Vary the induction level of the competing circuit to create a resource titration series

Data Integration and Model Fitting:

- Correlate circuit performance metrics with host physiological parameters across all conditions

- Fit parameters for mathematical models of resource competition and growth feedback

- Identify which host factors most strongly predict circuit performance variations

Troubleshooting:

- If circuit performance is inconsistent across replicates, verify culture conditions and measurement timing

- If resource measurements show high variability, increase sample size and implement more stringent normalization protocols

- If no host-dependent effects are observed, expand the host panel to include more physiologically diverse strains

Protocol 2: Implementing Host-Aware Control Strategies

Objective: Implement control-embedded circuit designs that actively manage host-circuit interactions to maintain robust performance.

Background: Once host-circuit interactions are characterized, control strategies can be implemented to mitigate undesirable effects or even exploit these interactions for enhanced functionality. These strategies range from passive insulation to active feedback control.

Materials:

- Orthogonal RNA polymerases and ribosome binding sites

- Feedback controller circuits (negative autoregulators, incoherent feedforward loops)

- Resource demand regulators (ppGpp controllers, translational resource sensors)

- Growth-coupled selection markers

Experimental Workflow:

Procedure:

Interaction Characterization:

- Use Protocol 1 to quantify the specific host-circuit interactions affecting your system

- Classify interactions as primarily resource competition, growth feedback, or a combination

- Identify which circuit components are most sensitive to host context

Control Strategy Selection:

- For resource competition: Implement orthogonal resource systems or resource buffering

- For growth feedback: Implement growth-rate compensation circuits or growth-coupled designs

- For combined effects: Implement multi-layer control strategies

Passive Insulation Implementation:

- Replace sensitive regulatory elements with orthogonal alternatives (T7 RNAP instead of host RNAP, orthogonal ribosome binding sites)

- Implement "load driver" devices that buffer upstream modules from downstream loading effects

- Optimize codon usage to match host resources without creating excessive burden

Active Control Implementation:

- Implement negative autoregulation to reduce sensitivity to resource fluctuations

- Design incoherent feedforward loops that anticipate and compensate for resource depletion

- Incorporate resource sensors that dynamically adjust circuit activity based on available resources

- For mammalian systems, implement transcriptional or post-transcriptional controllers responsive to metabolic state

Cross-Host Validation:

- Test controlled circuits across the same host panel used in Protocol 1

- Quantify performance robustness using metrics such as coefficient of variation across hosts

- Compare performance stability of controlled vs. uncontrolled circuits

- Validate that control strategies do not introduce undesirable new dynamics or instabilities

Troubleshooting:

- If orthogonal systems create excessive burden, tune expression levels of orthogonal components

- If feedback controllers introduce oscillations, adjust controller parameters or add filtering mechanisms

- If control circuits themselves become host-dependent, implement hierarchical control strategies

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The host-aware design framework opens up new possibilities for synthetic biology that embrace rather than avoid context dependence. These include:

Context-Programmable Circuits: Circuits designed to perform different functions in different host environments, enabling environment-specific drug production or diagnostics.

Host-Specific Security Features: Circuits that only function in specific host backgrounds, creating biological containment systems that prevent horizontal gene transfer.

Dynamic Resource Management: Multi-circuit systems that implement resource allocation policies, prioritizing essential functions during resource limitation.

Evolutionary Robustness: Circuits designed to maintain function despite host evolution, critical for long-term environmental applications.

Each of these applications treats host context not as a nuisance variable to be controlled, but as an informative input that can expand the functional capacity of synthetic genetic systems. As the field advances, the development of standardized host characterization panels and shared datasets of host-circuit interaction parameters will accelerate the adoption of these host-aware design principles across the synthetic biology community.

The vision of host-agnostic genetic device engineering remains aspirational, but by systematically reframing host dependence as a design parameter rather than an obstacle, researchers can develop genetic systems that function more predictably across diverse contexts, bringing us closer to the engineering reliability that has long been promised by synthetic biology.

Building Host-Independent Systems: Tools and Implementation Strategies

The expansion of synthetic biology beyond traditional model organisms like Escherichia coli requires genetic tools that function predictably across diverse microbial hosts. Modular vector systems have emerged as a critical solution, enabling researchers to assemble standardized genetic parts into functional constructs for engineering complex bacterial phenotypes. The Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA) platform represents a pioneering standard in this field, providing a structured framework for the physical assembly and functional organization of plasmid vectors [16]. These systems are fundamental to the emerging paradigm of broad-host-range (BHR) synthetic biology, which redefines microbial hosts as active, tunable components in genetic design rather than passive platforms [1]. By treating the microbial chassis itself as a modular part, researchers can leverage innate host capabilities—such as photosynthetic activity in cyanobacteria or stress tolerance in extremophiles—to optimize system performance for specific biotechnological applications in biomanufacturing, environmental remediation, and therapeutics [1].

The SEVA database (SEVA-DB) serves as both a web-based resource and material repository, assisting researchers in selecting optimal plasmid configurations for deconstructing and reconstructing complex prokaryotic phenotypes [16]. This standardized approach addresses the critical challenge of host-context dependency, where identical genetic constructs exhibit different behaviors across microbial hosts due to variations in resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [1]. As the field progresses toward more predictable engineering of non-model organisms, modular vector systems like SEVA provide the foundational infrastructure necessary for systematic host-agnostic genetic device engineering.

SEVA Standard: Architecture and Design Principles

Core Architectural Framework

The SEVA standard employs a minimalist, systematic approach to vector design based on engineering principles. Each SEVA vector is organized into three fundamental interchangeable modules: (1) the origin of replication (ORI), (2) the antibiotic selection marker (AB), and (3) the cargo or "business" segment [17]. These modules are physically assembled within a standardized scaffold featuring three core insulator sequences that prevent unintended transcriptional read-through and enhance plasmid stability [17].

The connector sequences include strong, rho-independent transcriptional terminators T0 (from phage lambda) and T1 (from the rrnB operon of E. coli), which flank the cargo segment to insulate it from the rest of the vector [17]. Additionally, all SEVA vectors contain a 246-bp origin of transfer (oriT) from the broad-host-range plasmid RP4, enabling conjugative mobilization into bacterial species that may be difficult to transform using conventional methods [17]. This strategic inclusion significantly expands the range of accessible microbial hosts for genetic engineering.

Standardization and Nomenclature

A key innovation of the SEVA platform is its standardized nomenclature, which provides an unambiguous alphanumeric code for designating vector constructs. This systematic naming convention allows researchers to quickly identify the functional components of any SEVA vector without consulting detailed sequence information [16]. The database is designed to simplify vector selection for specific applications, enabling users to identify optimal configurations of replication origins, antibiotic resistance markers, and functional cargo segments for their experimental needs [16] [17].

The SEVA design process involved minimizing naturally occurring sequences to their shortest functional segments, removing redundant restriction sites, and optimizing codons while retaining protein function [17]. This meticulous optimization reduces vector size and eliminates potentially problematic sequences that might interfere with vector function or assembly. The resulting collection of formatted vectors provides a foundational toolkit for engineering complex phenotypes across diverse Gram-negative bacteria.

SEVA Module Specifications and Quantitative Data

SEVA Vector Composition Data

Table 1: Standardized SEVA Module Specifications

| Module Type | Key Components | Size Range | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Resistance | Kanamycin, Ampicillin, Chloramphenicol, and other resistance genes with native promoters | 0.8 - 1.3 kb | Plasmid selection and maintenance in specific hosts [17] |

| Origin of Replication | Narrow and broad-host-range origins (e.g., pBBR1, RSF1010, ColE1) | Varies by type | Determines host range and plasmid copy number [16] [17] |

| Cargo Segment | Multiple Cloning Site (MCS), reporter genes, metabolic pathways | User-defined | Contains functional genetic circuit for phenotype engineering [16] |

| Connector Sequences | T0 and T1 transcriptional terminators, oriT | T0: 103 bp, T1: 105 bp, oriT: 246 bp | Prevents transcriptional read-through, enables conjugation [17] |

Broad-Host-Range Application Data

Table 2: SEVA-Compatible Bacterial Hosts and Applications

| Host Organism Type | Example Species | Relevant Native Phenotypes | Potential Biotech Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolically Versatile Bacteria | Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | Capable of all four metabolic modes (photoheterotrophy, photoautotrophy, chemoheterotrophy, chemoautotrophy) | Bioremediation, biofuel production [1] |

| Halotolerant Bacteria | Halomonas bluephagenesis | High-salinity tolerance, natural product accumulation | Industrial bioprocessing, biopolymer production [1] |

| Phototrophic Bacteria | Cyanobacteria species | Photosynthetic capability, CO₂ fixation | Carbon capture, solar-powered chemical production [1] |

| Methylotrophic Bacteria | Methylobacterium species | Methanol utilization | C1 compound bioconversion [17] |

Experimental Protocols for SEVA Implementation

Protocol 1: Modular Assembly of SEVA Vectors

Principle: SEVA vectors are designed for compatibility with both traditional cloning methods and modern DNA assembly techniques, including Golden Gate assembly [17]. The standardized architecture allows efficient swapping of functional modules using rare restriction enzymes that flank each module.

Procedure:

- Module Preparation: Isolate DNA modules (ORI, AB, cargo) from SEVA repository vectors or amplify using SEVA-standard primers (PS1-PS6) that hybridize to connector regions [17].

- Restriction Digestion: Digest recipient SEVA vector and donor modules with appropriate restriction enzymes (SwaI/PshAI for antibiotic markers, AscI/FseI for origins of replication) [17].

- Ligation and Transformation: Ligate modules into the SEVA backbone and transform into appropriate E. coli strain for assembly.

- Verification: Verify correct assembly by analytical restriction digest and sequencing using SEVA-standard verification primers.

- Conjugative Transfer: For challenging hosts, mobilize constructs via conjugation using the RP4 oriT system and appropriate helper strains [17].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Ensure complete digestion by using freshly prepared restriction enzymes and extended incubation times.

- Include control reactions without insert to assess background from undigested vector.

- For conjugation, optimize donor-to-recipient ratios and mating times for specific target hosts.

Protocol 2: Cross-Host Functional Assessment of Genetic Devices

Principle: Evaluating genetic device performance across multiple microbial hosts is essential for host-agnostic engineering. This protocol enables systematic comparison of identical genetic circuits in different bacterial chassis.

Procedure:

- Vector Mobilization: Introduce the SEVA construct containing the genetic device into multiple bacterial hosts via conjugation or transformation [1] [17].

- Growth Conditions: Culture all hosts under their respective optimal conditions while maintaining selection for the SEVA plasmid.

- Device Performance Metrics: Measure key performance parameters including:

- Expression dynamics: Fluorescence/output intensity over time

- Response characteristics: Activation kinetics, sensitivity, and dynamic range for inducible systems

- Burden effects: Growth rate impact, plasmid stability

- Resource allocation: Transcriptional and translational resource availability [1]

- Data Normalization: Normalize outputs to account for host-specific differences in growth rate and biomass.

- Host-Specific Optimization: Iteratively refine device components (promoters, RBS) based on performance data.

Applications: This protocol enables identification of optimal host-device pairings for specific applications and provides empirical data on how host context influences device function [1].

Complementary Modular Cloning Systems

While SEVA specializes in bacterial engineering, several complementary modular systems have been developed for other applications:

Golden Gate-based Systems: The Modular Cloning (MoClo) system uses Type IIS restriction enzymes (BsaI, BpiI/BbsI) to assemble DNA parts with 4-bp fusion sites, enabling efficient one-pot assembly of multiple fragments [18]. MoClo has been adapted for diverse applications including plant synthetic biology (MoClo Toolkit, GreenGate), yeast engineering (MoClo-YTK), and mammalian cell engineering (Fragmid toolkit) [19] [18].

Fragmid Toolkit: Specifically designed for CRISPR applications, Fragmid enables rapid assembly of CRISPR cassettes and delivery vectors for various technologies including knockout, activation, interference, base editing, and prime editing [19]. The system uses a modular approach with six fragment types (Guide cassettes, Pol II promoters, N' terminus domains, Cas proteins, C' terminus domains, and 2A-selection markers) that can be mixed and matched with different destination vectors for lentivirus, PiggyBac transposon, and AAV delivery [19].

These complementary systems share the core principles of standardization, modularity, and hierarchical assembly that characterize the SEVA platform, demonstrating the broad applicability of modular design in synthetic biology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Modular Vector Engineering

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| SEVA Plasmid Repository | Source of standardized SEVA vectors with various ORI and AB combinations | SEVA-DB (seva-plasmids.com) [16] |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | BsaI, BbsI, BsmBI for Golden Gate assembly of modular parts | Commercial suppliers (NEB, Thermo Fisher) [19] [18] |

| Conjugation Helper Strains | Provide conjugation machinery for mobilizing SEVA vectors via oriT | Strain repositories (e.g., E. coli with RP4 tra genes) [17] |

| Broad-Host-Range cDNA Libraries | Source of diverse genetic parts for cargo modules | Commercial and academic sources [1] |

| MoClo Toolkit Parts | Standardized genetic parts for eukaryotic systems | Addgene [18] |

Visualizing SEVA Architecture and Workflows

SEVA Modular Vector Architecture

Host-Agnostic Genetic Device Engineering Workflow

Broader Context: SEVA in Host-Agnostic Genetic Engineering

The SEVA platform represents a crucial enabling technology for the emerging field of broad-host-range synthetic biology, which seeks to move beyond traditional model organisms to leverage the vast functional diversity of microbial life [1]. This approach reconceptualizes host selection as an active design parameter rather than a default choice, acknowledging that different microbial chassis can significantly influence the behavior of engineered genetic devices through variations in resource allocation, metabolic interactions, and regulatory crosstalk [1].

The chassis effect—where identical genetic constructs exhibit different behaviors across host organisms—presents both a challenge and an opportunity for synthetic biologists [1]. SEVA vectors help researchers systematically characterize and exploit these host-dependent variations by providing a standardized platform for cross-host comparisons. This capability is particularly valuable for applications requiring specialized host attributes, such as environmental bioremediation (using pollutant-degrading bacteria), industrial biomanufacturing (using solvent-tolerant strains), or therapeutic applications (using human commensal bacteria) [1].

As synthetic biology continues to expand into non-model organisms, standardized modular systems like SEVA will play an increasingly important role in enabling predictable engineering of biological systems. The integration of SEVA with other modular standards and the development of next-generation vectors will further enhance our ability to harness microbial diversity for biotechnology applications.

A central challenge in synthetic biology is the context-dependent performance of engineered genetic circuits, where functionality is intricately linked to host cellular resources and physiology [14]. This application note details the principles and methodologies for genetic insulation, a design strategy focused on decoupling synthetic modules from host resource limitations to achieve predictable and robust circuit behavior. Framed within the broader research objective of host-agnostic genetic device engineering, these protocols provide actionable steps for researchers to characterize and mitigate the effects of resource competition and growth feedback, which are significant bottlenecks in the DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) cycle [14].

Background and Core Concepts

The Context-Dependence Problem

Synthetic gene circuits do not operate in isolation. Their behavior is influenced by complex circuit-host interactions, primarily mediated through two feedback mechanisms: growth feedback and resource competition [14].

- Growth Feedback: A multiscale feedback loop where circuit activity consumes cellular resources, imposing a metabolic burden that reduces host growth rate. This reduced growth rate, in turn, alters circuit dynamics by changing the dilution rate of circuit components and the physiological state of the cell [14].

- Resource Competition: Arises from the competition among circuit modules for a finite pool of shared, essential cellular resources, such as RNA polymerase (RNAP), ribosomes, nucleotides, and amino acids [14]. This competition can lead to unintended coupling between otherwise independent modules, causing emergent dynamics like bistability and stochastic switching [20].

Consequences of Resource Limitation

The interplay of these interactions can lead to several unintended outcomes:

- Altered Phenotypic States: Resource competition can create a "winner-takes-all" dynamic, where one gene module dominates resource usage while suppressing another, potentially leading to emergent bistability or tristability [14] [20].

- Amplified Gene Expression Noise: Competition for limited resources introduces a new source of noise and can amplify cell-to-cell variability, reducing the reliability and predictability of circuit function [20].

- Loss of Modularity: The core engineering principle of modularity is violated when the performance of one module depends on the activity and resource consumption of another, making complex circuit design challenging [14].

The following diagram illustrates the core feedback loops that create context-dependence.

Figure 1. Core circuit-host interactions. Circuit operation consumes resources, burdening the host and reducing growth. Growth rate dilutes circuit components and upregulates resources, which in turn stimulate circuit function.

Quantitative Characterization of Resource Effects