Beyond E. coli: Strategies for Predictable Genetic Circuit Design Across Diverse Microbial Chassis

This article addresses the central challenge in synthetic biology: the unpredictable performance of genetic circuits when transplanted between different microbial hosts.

Beyond E. coli: Strategies for Predictable Genetic Circuit Design Across Diverse Microbial Chassis

Abstract

This article addresses the central challenge in synthetic biology: the unpredictable performance of genetic circuits when transplanted between different microbial hosts. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental 'chassis effect' where identical genetic constructs behave differently due to host-specific cellular environments. The content systematically covers foundational principles explaining context-dependency, methodological advances in universal circuit design, optimization strategies to minimize host-circuit interference, and validation frameworks for cross-species prediction. By synthesizing recent breakthroughs in wetware engineering, computational tools, and standardization approaches, this resource provides a comprehensive roadmap for achieving robust, predictable genetic circuit function in non-model organisms critical for biomedical and industrial applications.

Understanding the Chassis Effect: Why Genetic Circuits Fail in New Hosts

A central challenge in synthetic biology is the persistent gap between the qualitative design of genetic circuits and their quantitative performance in living systems. While design tools allow researchers to create sophisticated logical operations in silico, the resulting circuits often behave unpredictably when implemented in biological chassis [1]. This gap represents a significant bottleneck in transitioning synthetic biology from proof-of-concept demonstrations to reliable, real-world applications in therapeutic development, bioproduction, and biosensing [2] [3].

The core issue stems from biological context-dependence: genetic parts and devices characterized in isolation often behave differently when assembled into complex circuits and placed within a cellular environment that competes for resources, contains native regulatory networks, and operates under variable physical conditions [4] [1]. This article establishes a technical support framework to help researchers diagnose, troubleshoot, and overcome these predictability challenges, with particular emphasis on improving cross-chassis compatibility.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my genetic circuit work perfectly in E. coli but fail in my desired production chassis?

A: Chassis-specific differences in cellular machinery cause this common issue. Variations in RNA polymerase concentrations, codon usage biases, availability of tRNA pools, metabolic burden responses, and innate immune responses can all dramatically alter circuit performance between organisms [5] [6]. Implementing orthogonal systems (e.g., bacterial transcription factors in plants) that minimize crosstalk with host processes can improve cross-chassis functionality [4].

Q2: My circuit shows correct logic in plate readers but behaves erratically in actual application conditions. What causes this?

A: Laboratory conditions are optimized and controlled, while real-world environments are dynamic. Factors like temperature fluctuations, varying nutrient availability, cell growth phase, and inducer concentration gradients significantly impact circuit performance [2] [1]. For example, research has demonstrated that a simple delay-signal circuit can have its output detection time changed from the optimal 180 minutes to over 300 minutes simply by altering temperature or growth medium [1].

Q3: How can I make my genetic circuit more robust to environmental and context-dependent variations?

A: Several strategies enhance robustness:

- Implement insulation devices: Incorporate genetic insulators between circuit modules to reduce unwanted interactions [3].

- Use orthogonal parts: Select parts from distant biological systems that don't interact with host machinery [4].

- Characterize broadly: Test circuits under a wide range of conditions expected in the final application [1].

- Employ model-guided redesign: Use computational models informed by characterization data to predict and improve performance [7].

Q4: What is the most common mistake in genetic circuit design that leads to unpredictable performance?

A: The most prevalent mistake is characterizing genetic parts only under optimal laboratory conditions rather than the diverse conditions the circuit will encounter in its intended application [1]. This creates a fundamental mismatch between design parameters and operational reality. Additionally, failing to account for metabolic burden and resource competition between circuit modules often leads to progressive performance degradation over time [4] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Circuit Performance Drift Over Time

Symptoms: Initial circuit function matches predictions, but performance degrades over multiple generations or during extended culture.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Measure growth rate and check for metabolic burden

- Sequence key circuit elements to check for mutations

- Test for plasmid loss in non-selectively maintained systems

- Monitor cell viability and resource depletion indicators

Solutions:

- Reduce metabolic burden: Simplify circuit design, use weaker promoters where possible, or implement resource allocator systems [6].

- Enforce genetic stability: Incorporate toxin-antitoxin systems for plasmid maintenance or integrate circuits into the genome [2].

- Implement load balancing: Distribute expression demands across the circuit to prevent bottlenecking [4].

Problem: Context-Dependent Part Performance

Symptoms: Individual parts meet specifications when tested alone but behave differently when assembled into the full circuit.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Test each part in isolation versus assembled context

- Check for transcriptional read-through between modules

- Measure unintended interactions between regulatory elements

- Verify ribosome binding site accessibility in new contexts

Solutions:

- Add insulation: Incorporate transcriptional terminators and insulators between circuit modules [3].

- Use orthogonal regulators: Implement CRISPR-based regulation or bacterial transcription factors in eukaryotic systems to minimize crosstalk [4].

- Employ modular design: Create functional modules with standardized interfaces that maintain consistent behavior when connected [8].

Problem: Variable Performance Across Different Chassis

Symptoms: Circuit functions as designed in one chassis but shows altered dynamics, leaky expression, or complete failure in another.

Diagnosis Checklist:

- Compare growth rates and metabolic states between chassis

- Verify compatibility of genetic parts with chassis machinery

- Test for host-specific nucleases or proteases that degrade circuit components

- Check for differences in membrane permeability affecting inducer uptake

Solutions:

- Adapt parts to chassis: Perform codon optimization, use chassis-specific promoters, or select RBS sequences matched to the chassis [5].

- Employ chassis-agnostic systems: Use orthogonal systems like viral polymerases or synthetic transcription factors that function across diverse organisms [4].

- Characterize early in target chassis: Test fundamental circuit operations in the actual application chassis during design phase [1].

Quantitative Data Reference Tables

Table 1: Environmental Factors Affecting Circuit Performance

| Environmental Factor | Tested Range | Impact on Output Detection Time | Impact on Signal Intensity | Recommended Characterization Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 23°C - 45°C | +125% to -50% vs. optimal [1] | +80% to -70% vs. optimal [1] | 25°C-42°C for mesophilic organisms |

| Inducer Concentration | 0.01X - 10X | +300% to -60% vs. optimal [1] | +250% to -95% vs. optimal [1] | 0.1X-5X of standard concentration |

| Growth Phase at Induction | Early log to stationary | +67% to -33% vs. mid-log [1] | +45% to -60% vs. mid-log [1] | Early log, mid-log, late log phases |

| Nutrient Availability | Limited to rich | +200% to -25% vs. optimal [1] | +150% to -80% vs. optimal [1] | Mimic application conditions |

Table 2: Circuit Performance Metrics Across Different Chassis Types

| Chassis Type | Typical Transformation Efficiency | Genetic Stability | Resource Competition Impact | Recommended Circuit Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (laboratory strains) | High (10^8-10^9 CFU/μg) | Moderate (plasmid loss 1-5%/gen) | Low to moderate [6] | High (multiple logic gates) |

| B. subtilis | Moderate (10^6-10^7 CFU/μg) | High (genomic integration) | Moderate [2] | Moderate (2-3 logic gates) |

| P. pastoris | Low to moderate (10^4-10^5 CFU/μg) | High (genomic integration) | Low [2] | Low to moderate (1-2 logic gates) |

| Plant systems | Very low (tissue-dependent) | High (stable transformation) | High [4] | Low (single operations) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Comprehensive Circuit Characterization Under Non-Optimal Conditions

Purpose: To identify environmental factors most likely to cause circuit failure in application conditions [1].

Materials:

- Characterized genetic circuit in target chassis

- Inducer molecules at various concentrations

- Temperature-controlled shakers or incubators

- Different growth media (minimal, rich, application-specific)

- Plate reader or flow cytometer for output measurement

Procedure:

- Prepare experimental conditions:

- Set up temperature gradients (4°C, 23°C, 30°C, 37°C, 42°C)

- Prepare inducer concentration series (0.1X, 0.5X, 1X, 2X, 5X standard)

- Prepare different growth media mimicking application environment

Inoculate cultures:

- Start with overnight cultures grown in standard conditions

- Dilute to standard OD600 in each test condition

- Include triplicate biological replicates for each condition

Induce circuit and monitor:

- Add inducers at appropriate growth phase (early log, mid-log, stationary)

- Measure output (fluorescence, luminescence) and growth every 30-60 minutes

- Continue measurements for at least two full growth cycles

Analyze data:

- Calculate output detection time for each condition

- Determine maximum output intensity and growth rate

- Compare performance metrics across conditions

Interpretation: Conditions causing >50% change in detection time or >70% change in output intensity represent high-risk factors for application failure [1].

Protocol: Cross-Chassis Circuit Compatibility Testing

Purpose: To evaluate how circuit performance transfers between laboratory and application chassis [4] [6].

Materials:

- Circuit constructed with standardized genetic parts (BioBricks or similar)

- Laboratory chassis (e.g., E. coli DH10B) and application chassis

- Transformation equipment for both chassis

- Standardized measurement tools

Procedure:

- Adapt genetic parts:

- Perform codon optimization for target chassis if necessary [5]

- Select appropriate selection markers for each chassis

- Verify replication origins compatibility

Transform and validate:

- Transform circuit into both laboratory and application chassis

- Verify circuit integrity through sequencing after transformation

- Confirm basic functionality in both chassis

Comparative characterization:

- Measure transfer function (input-output relationship) in both chassis

- Determine dynamic range and response time

- Assess leakiness in OFF state

- Evaluate long-term stability over multiple generations

Identify mismatch points:

- Compare performance metrics between chassis

- Identify specific circuit operations with largest performance gaps

- Test individual parts causing performance bottlenecks

Interpretation: >80% performance conservation across chassis indicates good portability; <50% suggests need for chassis-specific optimization [4].

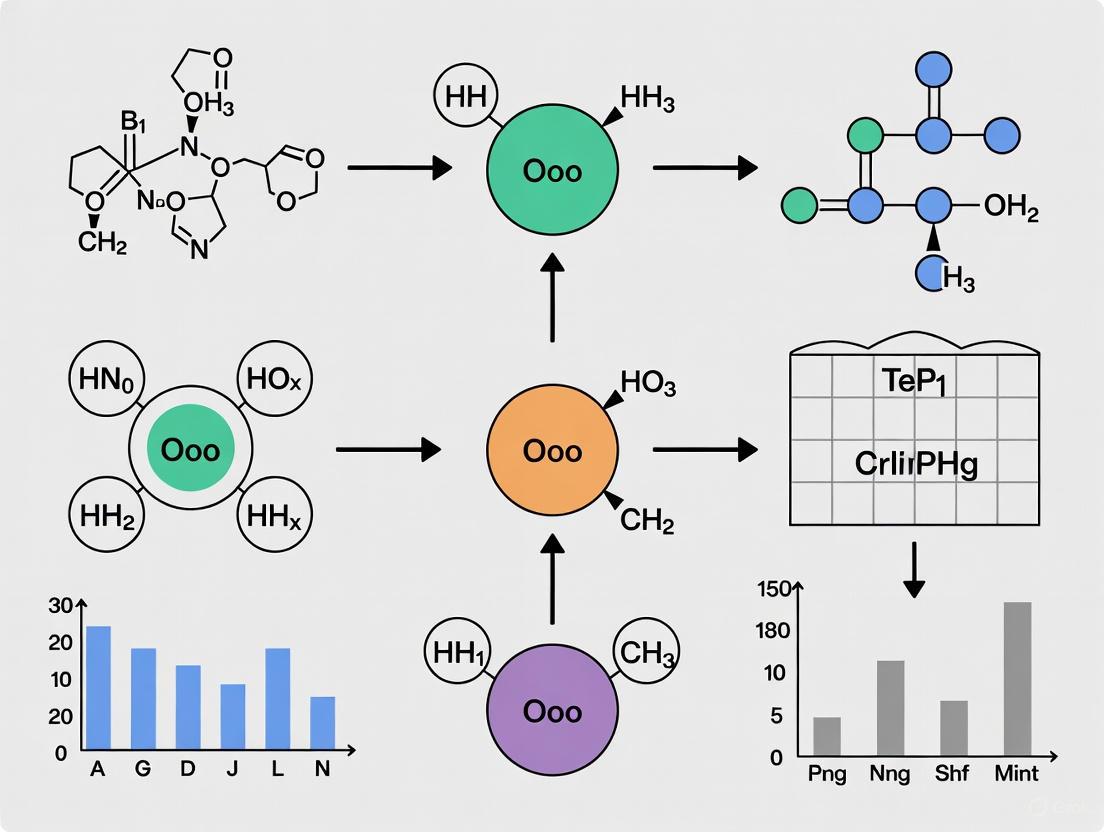

Visualization of Key Concepts

Genetic Circuit Design and Testing Workflow

Environmental Factors Affecting Circuit Performance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Genetic Circuit Characterization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations for Cross-Chassis Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors | Bacterial TFs (TetR, LacI), CRISPR/dCas9 systems [4] [3] | Minimize crosstalk with host regulatory networks | Verify compatibility with host RNA polymerase and cofactors |

| Standardized Genetic Parts | BioBricks, MoClo parts [5] [8] | Ensure reproducible assembly and characterization | Test part function in each chassis; adapt as needed |

| Inducer Molecules | AHL, Arabinose, Tetracycline, β-Estradiol [4] [1] | Trigger circuit operation in controlled manner | Verify membrane permeability and absence of degradation in each chassis |

| Reporter Proteins | GFP, YFP, RFP, Luciferase [1] [8] | Quantify circuit output and dynamics | Consider maturation time, stability, and detection sensitivity |

| Characterization Tools | Plate readers, Flow cytometers, qPCR systems [1] | Measure circuit performance quantitatively | Standardize measurement protocols across chassis for fair comparison |

| Computational Modeling Tools | iBioSim, Cello, ODE solvers [7] [1] | Predict circuit behavior before construction | Incorporate chassis-specific parameters for accurate predictions |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is "metabolic burden" and how does it affect my genetic circuits? Metabolic burden is the stress imposed on a host cell (chassis) by the introduction and operation of synthetic genetic circuits. This burden arises because cellular resources—such as amino acids, energy molecules (ATP), nucleotides, and transcription/translation machinery (RNA polymerase, ribosomes)—are finite. When a genetic circuit consumes these resources, it diverts them from the host's native processes essential for growth and maintenance. This competition can lead to several observable issues: a decreased growth rate, impaired protein synthesis, genetic instability, and an aberrant cell size [9]. In industrial applications, this manifests as low production titers and a loss of newly acquired characteristics over long fermentation runs, ultimately threatening process viability [9] [10].

Why does the same genetic circuit behave differently in another host organism? This phenomenon, known as the "chassis effect," occurs because different host organisms have unique cellular environments. Key factors that vary between hosts and affect circuit performance include:

- Resource Allocation: The inherent distribution of resources like RNA polymerase and ribosomes differs [11].

- Transcription/Translation Machinery: Variations in sigma factors, transcription factors, and codon usage can alter gene expression [9] [11].

- Metabolic Network Structure: The baseline metabolic state and regulatory networks are host-specific [9] [10].

- Regulatory Crosstalk: Introduced circuits may inadvertently interact with the host's native regulatory pathways [11]. Even identical genetic circuits can exhibit divergent performance metrics—such as output signal strength, response time, and leakiness—when moved between different bacterial species [11].

What are the molecular triggers of metabolic burden in engineered cells? The primary triggers when (over)expressing proteins, including those in genetic circuits, are:

- Depletion of Metabolites: Draining the cellular pools of amino acids and energy molecules [9].

- Charged tRNA Imbalance: Overuse of rare codons in heterologous genes can lead to a shortage of correctly charged tRNAs, stalling ribosomes [9].

- Misfolded Proteins: Translation errors or incorrect folding due to rapid synthesis can generate non-functional proteins that overwhelm the cell's quality control systems [9]. These triggers activate stress response mechanisms like the stringent response (via alarmones like ppGpp) and the heat shock response, which collectively contribute to the observed negative physiological symptoms [9].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Failure Modes and Solutions

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced cell growth rate | High resource competition from the circuit, leading to energy and precursor depletion [9] [10]. | - Decrease strength of circuit promoters [12].- Implement dynamic control to delay circuit activation until after peak growth [10]. |

| Low or unexpected output signal | Resource overload (e.g., RNA polymerase sequestration), improper part function in new chassis, or high intrinsic noise [11] [12]. | - Use circuit compression techniques to minimize genetic footprint [13].- Re-tune RBS strengths or promoters for the specific host [11].- Ensure proper codon optimization for the host [9]. |

| Loss of circuit function over time (genetic instability) | High burden selects for mutant cells that have inactivated the costly circuit [9] [10]. | - Use genomic integration instead of high-copy plasmids [10].- Include a selection mechanism for circuit retention, but avoid antibiotics in production [10]. |

| High cell-to-cell variability (noise) | Stochastic expression in a resource-limited environment, leading to "extrinsic noise" [14] [12]. | - Engineer circuits for positive feedback to reinforce decision-making [12].- Use insulators to decouple the circuit from host noise [12]. |

Quantifying Metabolic Burden

Before and after implementing a genetic circuit, it is crucial to measure key physiological parameters to quantify the burden. The table below summarizes critical metrics and how to assess them.

| Metric | How to Measure | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Optical density (OD600) measurements over time during batch culture [9]. | A significant drop in growth rate indicates a high metabolic burden. |

| Maximum Biomass | Final OD600 or dry cell weight at the end of a batch culture [9]. | Lower maximum biomass suggests resources are diverted from biomass production. |

| Product Yield | Titer of the circuit's output (e.g., protein, metabolite) measured via assays or HPLC [10]. | A lower-than-expected yield can indicate burden or inefficiency. |

| Plasmid Retention | Plate cells on selective and non-selective media to count colonies, or use flow cytometry if a reporter is present [10]. | Low retention rates indicate strong selection for cells that lose the plasmid. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Circuit-Induced Growth Defects

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the impact of a genetic circuit on the host's growth physiology.

Materials:

- Sterile LB or defined minimal media

- Appropriate antibiotic(s) if using plasmids

- Shaking incubator for cell culture

- Spectrophotometer or plate reader capable of measuring OD600

- Culture tubes or a multi-well plate

Method:

- Strain Preparation: Transform your genetic circuit into the chassis organism. Include a control strain containing an empty vector or a non-functional version of the circuit.

- Inoculation: Pick single colonies of both the test and control strains and inoculate them in 3-5 mL of media with appropriate antibiotics. Grow overnight at the required temperature with shaking.

- Dilution: The next day, dilute the overnight cultures in fresh media to a standardized low OD600 (e.g., 0.05). Use at least three biological replicates for each strain.

- Growth Measurement:

- Culture Tube Method: Incubate the diluted cultures with shaking. Measure the OD600 of each culture every 30-60 minutes. Gently vortex tubes before reading to ensure an even cell suspension.

- Microplate Reader Method: Dispense 200 µL of diluted cultures into a 96-well plate. Seal the plate with a breathable membrane to prevent evaporation. Place the plate in the reader, set to the correct temperature with continuous shaking between measurements. Take OD600 readings every 10-15 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural log of OD600 versus time. Calculate the growth rate (µ) for each replicate from the linear portion of the plot (the exponential phase). Compare the average growth rates and maximum OD600 of the test strain versus the control using a t-test to determine statistical significance.

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Mitigating Burden via Circuit Compression

Purpose: To systematically redesign a genetic circuit to minimize its genetic footprint and resource consumption, thereby improving host health and circuit predictability [13].

Diagram 1: A workflow for circuit compression and testing.

Materials:

- Software for algorithmic circuit enumeration (e.g., custom scripts as in [13])

- Standard molecular biology cloning reagents

- Parts library of synthetic transcription factors and promoters [13]

Method:

- Define Logic: Clearly define the desired computational function of your circuit (e.g., its Boolean truth table) [13].

- Enumerate Designs: Use an algorithmic enumeration method to search the combinatorial space of possible circuit designs that fulfill the logic. The algorithm should model the circuit as a directed acyclic graph and systematically list designs in order of increasing complexity (number of parts) [13].

- Select Compressed Design: From the enumerated list, select the most compressed (smallest) circuit that correctly implements your logic. This design will use the fewest genetic parts (promoters, genes, RBS), minimizing the DNA footprint and potential resource demand [13].

- Build and Test: Synthesize and assemble the compressed genetic circuit. Introduce it into your chassis organism.

- Validate Performance: Measure the circuit's functional output (e.g., fluorescence) and the host's physiological parameters (growth rate, as in Protocol 1). Compare these metrics to those from the original, larger circuit. The compressed circuit should maintain the desired function while showing improved host health and robustness [13].

Visualizing the Problem: Key Pathways and Workflows

The Metabolic Burden Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the cascade of cellular events, from genetic circuit induction to the emergence of stress symptoms and system failure.

Diagram 2: The cascade from circuit activation to system failure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key tools and strategies mentioned in research for diagnosing and alleviating metabolic burden.

| Tool / Strategy | Function / Purpose | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Metabolic Control | Delays circuit expression until after peak biomass growth, decoupling production from growth [10]. | Uses promoters induced by a quorum signal or a metabolite peak (e.g., lactate). |

| T-Pro (Transcriptional Programming) | A circuit design method that uses synthetic transcription factors and promoters to achieve complex logic with fewer parts (compression) [13]. | Reduces the number of genetic parts by ~4x compared to canonical inverter-based circuits, lowering burden [13]. |

| Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Vectors | Plasmid systems designed to function across diverse microbial species, facilitating chassis screening [11]. | e.g., Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA). Allows testing in hosts with higher native burden tolerance. |

| Cellular Resources | Amino Acids, ATP, RNA Polymerase, Ribosomes, Charged tRNAs | The fundamental, finite pools that are competed for. The core of resource competition [9]. |

| Physiological Engineering | Directly modifies the host's physiology to be more resilient to burden [10]. | Can involve engineering central metabolism, ribosome levels, or stress response systems. |

| Microbial Consortia | Divides a complex metabolic pathway or circuit across different, specialized strains [10]. | Distributes the burden, avoiding overloading a single cell. Can improve overall pathway yield and stability. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unpredictable Genetic Circuit Performance Across Different Chassis

Q: My genetic circuit functions as expected in E. coli but shows erratic behavior in a non-model chassis. What could be causing this?

A: This is a classic symptom of the "chassis effect," where host-specific cellular machinery interferes with your design [11]. The primary cause is often competition for finite resources or unexpected crosstalk with the host's native transcription factors (TFs) and regulatory networks [15] [11].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check Resource Allocation: Measure the growth rate and burden. Severe growth defects indicate your circuit is overconsuming resources like RNA polymerase, ribosomes, and nucleotides, diverting them from essential host functions [11].

- Profile Host-Transcription Factor Interactome: Use RNA sequencing to analyze changes in the host's native gene expression upon circuit introduction. Look for upregulation or downregulation of stress responses and native TF pathways [15].

- Verify Part Orthogonality: Test your synthetic promoters and TF coding sequences for unintended interactions with the host's regulatory machinery. A part that is orthogonal in E. coli may be recognized by TFs in another species [13].

Solutions:

- Refactor the Circuit: Simplify the design to use fewer parts or re-engineer components to be more orthogonal to the new host's systems [13] [11].

- Tune Expression Levels: Lower the expression demands of your circuit by using weaker promoters or ribosome binding sites (RBS) to reduce metabolic burden [11].

- Select a Compatible Chassis: Choose a host whose innate biological functions align with your circuit's purpose, such as using a phototroph for light-driven applications [11].

Problem 2: Inflammatory Signaling and Cytokine Storm Simulation

Q: My model of host-transcription factor crosstalk in a mammalian system shows uncontrolled positive feedback in NF-κB and STAT3 signaling, leading to a simulated "cytokine storm." How can I regain control?

A: This dysregulation occurs when pro-inflammatory signaling lacks sufficient negative feedback. Your model needs to incorporate key regulatory interactions and post-translational modifications (PTMs) that dampen these pathways [15].

Diagnostic Steps:

- Audit Negative Regulators: Ensure your model includes the roles of key negative regulators such as ATF3, which represses pro-inflammatory genes like TNF-α, and PPARγ, which can suppress NF-κB-driven inflammation [15].

- Check PTM Dynamics: Verify that SUMOylation and ubiquitination events are accurately modeled. For instance, SUMOylation of PPARγ is a key anti-inflammatory signal, and its impairment can amplify cytokine release [15].

- Validate Crosstalk Mechanisms: Confirm that the cooperative interaction between HIF-1α and NF-κB, which enhances transcription of TNF-α and IL-1β under hypoxic conditions, is counterbalanced by NRF2, which represses NF-κB signaling [15].

Solutions:

- Enhance Feedback Loops: Explicitly model the induction of stress-responsive TFs like ATF3 and NRF2 that provide negative feedback on inflammatory pathways [15].

- Incorporate Metabolic Constraints: Link transcriptional activity to metabolic status, as immunometabolic adaptation is a crucial layer of regulation in hyperinflammatory pathologies [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the most common types of regulatory interference in host-construct interactions? A: The most prevalent types are resource competition (e.g., for RNA polymerase, nucleotides) and direct molecular crosstalk, where host transcription factors or sigma factors inadvertently bind to synthetic genetic parts, altering their function [11]. Viral infections, like SARS-CoV-2, also highlight how pathogens can manipulate host TFs like NF-κB, IRFs, and NRF2 through ubiquitination and other PTMs, leading to widespread immune dysregulation [15].

Q: How can I improve the predictability of my genetic circuit when moving to a broad-host-range context? A: To enhance predictability [11]:

- Use BHR Parts: Leverage genetic parts (promoters, RBS, origins of replication) from databases like the Standard European Vector Architecture (SEVA), which are designed to function across multiple hosts.

- Characterize Context: Pre-characterize circuit components in the new host individually before assembling the full system.

- Treat Chassis as a Module: Strategically select your chassis based on its innate traits (e.g., metabolic capabilities, stress tolerance) that complement your circuit's function, rather than using a default model organism [11].

Q: In the context of IRF family transcription factors, what does "functional duality" mean? A: "Functional duality" refers to the phenomenon where a single Interferon Regulatory Factor (IRF), such as IRF1, IRF5, or IRF8, can act as either a tumor suppressor or a tumor promoter, depending on the cellular environment, disease stage, and interactions with other proteins [16]. This underscores the importance of modeling TF networks within a specific pathophysiological context.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative Analysis of Host-Circuit Crosstalk Using RNA-seq

Objective: To identify host genes and pathways significantly altered by the introduction of a synthetic genetic circuit.

- Sample Preparation:

- Transform your genetic circuit into the target chassis and include an empty vector control.

- Culture biological triplicates of both strains under identical conditions to the mid-exponential growth phase.

- RNA Extraction and Sequencing:

- Harvest cells and extract total RNA using a commercial kit, ensuring high RNA Integrity Number (RIN > 8.0).

- Prepare sequencing libraries and perform paired-end sequencing on an Illumina platform to a depth of at least 20 million reads per sample.

- Data Analysis:

- Align sequence reads to the host organism's reference genome using STAR aligner.

- Perform differential gene expression analysis using DESeq2. Genes with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 1 are considered significant.

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., KEGG, GO) on the significantly differentially expressed genes to identify perturbed host processes.

Protocol 2: Validating Transcription Factor Interference with a Two-Hybrid System

Objective: To test for direct physical interaction between a synthetic transcription factor from your circuit and host native transcription factors.

- Clone Construction:

- Clone the coding sequence of your synthetic TF into the DNA-BD (DNA-binding domain) vector (e.g., pGBKT7).

- Clone the coding sequences of key host TFs (e.g., IRFs, NF-κB subunits) into the AD (activation domain) vector (e.g., pGADT7).

- Yeast Transformation and Selection:

- Co-transform the DNA-BD and AD plasmid pairs into a yeast reporter strain (e.g., Y2HGold).

- Plate the transformed yeast on synthetic dropout (SD) media lacking leucine and tryptophan (-LW) to select for the presence of both plasmids.

- Interaction Assay:

- After 3-5 days of growth, pick colonies and restreak them onto higher-stringency SD media lacking leucine, tryptophan, and histidine (-LWH), possibly supplemented with Aureobasidin A, to test for protein-protein interaction that activates reporter genes.

- A positive growth signal on the high-stringency media indicates a direct interaction between your synthetic TF and the host TF.

Table 1: Contrast Ratios for WCAG 2.0/2.1 Compliance in Graphical Objects and User Interface Components (Level AA). Data is derived from established web accessibility guidelines and provides a standard for ensuring sufficient contrast in diagrams and visualizations [17] [18].

| Element Type | Minimum Contrast Ratio | Notes and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Text | 4.5:1 | Applies to text and images of text below ~18pt [18]. |

| Large Text | 3:1 | Text that is ≥18pt or ≥14pt and bold [18]. |

| Graphical Objects | 3:1 | Parts of graphics (e.g., chart wedges, icons, arrows) required to understand content [17]. |

| User Interface Components | 3:1 | Visual information required to identify UI components (buttons, form fields) and their states (focus, hover) [17]. |

Table 2: Chassis-Dependent Performance Variation of an Identical Genetic Circuit. This table synthesizes hypothetical data based on the principles of Broad-Host-Range synthetic biology, illustrating how the same circuit can behave differently across hosts [11].

| Host Chassis | Circuit Output (AU) | Response Time (min) | Observed Growth Burden |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (MG1655) | 1000 | 45 | Low |

| P. putida | 650 | 30 | Negligible |

| S. meliloti | 150 | 120 | High |

| B. subtilis | 850 | 90 | Moderate |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Host TF Crosstalk and Feedback

Circuit Testing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Host-Construct Interactions.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Vectors | Plasmid backbones with origins of replication and selection markers that function in diverse bacterial species. | Deploying genetic circuits across multiple non-model chassis to test for host-effects [11]. |

| SEVA (Standard European Vector Architecture) Plasmids | A standardized, modular collection of BHR vectors that facilitate the swapping of genetic parts. | Ensuring reproducible and predictable engineering in diverse hosts [11]. |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (sTFs) | Engineered repressor/anti-repressor proteins with alternate DNA recognition domains for orthogonal control. | Implementing compressed genetic circuits with minimal parts to reduce context-dependency and burden [13]. |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) System | A platform to detect protein-protein interactions by reconstituting a functional transcription factor. | Validating suspected physical interactions between synthetic circuit components and host transcription factors. |

| Antibodies for Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) | Phospho-specific, Ubiquitin-specific, or SUMO-specific antibodies. | Detecting and quantifying PTMs (e.g., phosphorylation, ubiquitination) on host TFs like IRFs and NF-κB that are manipulated during infection or circuit interaction [15] [16]. |

What is Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Synthetic Biology? BHR synthetic biology is a modern subdiscipline that moves beyond traditional model organisms like E. coli and S. cerevisiae to use a diverse range of microbial hosts as engineering platforms. It treats host selection as a crucial design parameter rather than defaulting to a limited set of well-characterized chassis [11].

Why is the "Chassis Effect" a major concern for genetic circuit predictability? The "chassis effect" refers to the phenomenon where the same genetic construct exhibits different behaviors depending on the host organism. This occurs due to host-construct interactions including resource competition for ribosomes and RNA polymerase, metabolic burden, regulatory crosstalk, and differences in transcription factor abundance or promoter recognition [11].

What are the primary safety considerations for engineered therapeutic bacteria? Key safety measures include implementing suicide genetic circuits to prevent uncontrolled bacterial spread, creating auxotrophic strains that require specific supplements not found in the environment, and using surface modifications to temporarily evade immune detection while maintaining therapeutic persistence [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Genetic Circuit Failure Across Different Chassis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Expression | Host-specific transcription/translation machinery incompatibility | Use BHR genetic parts (e.g., SEVA vectors, BHR promoters) [11] |

| Incorrect ribosomal binding site (RBS) strength for chassis | Test different RBS sequences (e.g., E. coli consensus, chassis-native, computationally designed) [20] | |

| Unstable Circuit Performance | High metabolic burden leading to mutations | Reduce genetic footprint using circuit compression techniques; optimize induction levels [13] |

| Plasmid incompatibility or instability | Evaluate different broad-host-range origins of replication (e.g., IncP, IncQ, pBBR1) [20] | |

| Variable Output Signal | Resource competition affecting circuit dynamics | Characterize circuit performance in the specific host background; use host-aware modeling [11] |

| Failed Transformation | Restriction-modification systems | Use a strain deficient in restriction systems (e.g., McrA, McrBC, Mrr) [21] |

| Incompatible conjugation/electroporation method | Optimize transformation protocol for the specific non-model host [20] |

Troubleshooting Chassis-Specific Metabolic Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Microbial Growth Post-Engineering | Metabolic burden from heterologous expression | Use inducible systems to separate growth and production phases; optimize media [20] |

| Toxicity of Expressed Product | Product interference with host metabolism | Use lower expression strains, compartmentalization, or product export systems [13] |

| Lack of Inducer Response | Absence of specific transporter (e.g., LacY for IPTG) | Express missing transporter genes codon-optimized for the host [20] |

| Low Yield of Target Metabolite | Suboptimal flux through metabolic pathway | Apply multiplexed engineering to balance pathway expression; use genomic integration [20] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Developing a Broad-Host-Range Expression System

Purpose: To establish functional inducible expression in a non-model bacterium (exemplified with Ralstonia eutropha).

Materials:

- Broad-host-range vectors (e.g., pBBR1, pCM62, pKT230 derivatives)

- Conjugation system or optimized electroporation protocol

- Antibiotics for selection

- Inducers (e.g., L-arabinose, m-toluic acid)

Procedure:

- Vector Selection: Clone your gene of interest into multiple broad-host-range vectors with different origins of replication (e.g., IncP, IncQ, pBBR1) [20].

- Promoter Evaluation: Test inducible promoter systems (e.g., PBAD, PxylS/PM) in your target chassis. Include appropriate regulator genes.

- Transformation: Introduce constructs via conjugation or electroporation. Note that some plasmids may not be successfully electroporated and may require conjugation [20].

- Characterization: Measure expression levels with and without induction using fluorescence (e.g., RFP) or enzyme activity assays.

- Optimization: If expression is low, incorporate 5' mRNA stem-loop structures (e.g., T7 stem-loop) to enhance stability and test different RBS sequences [20].

- Cross-Testing: Verify that inducers for one system do not interfere with others if using multiple regulated circuits [20].

Expected Results: Different vectors and promoters will yield varying expression levels. For example, in R. eutropha, PBAD and PxylS/PM systems showed the highest induced expression, while PlacUV5 required heterologous LacY permease for IPTG uptake [20].

Protocol: Implementing a Kill-Switch Safety System

Purpose: To incorporate a genetically encoded safety circuit that prevents environmental persistence of engineered microbes.

Materials:

- Inducible promoter system (e.g., temperature-sensitive, chemical-inducible)

- Toxic gene product (e.g., ribonuclease, pore-forming protein)

- Appropriate chassis strain

Procedure:

- Circuit Design: Design a circuit where a essential survival gene is placed under control of a repressor that requires an external supplement, OR where a toxic gene is expressed upon escape conditions [19].

- Assembly: Clone the kill-switch circuit into a stable genetic element (plasmid or genome).

- Validation: Test the functionality by culturing engineered microbes with and without the required supplement or induce the escape condition.

- Long-Term Stability: Passage engineered strains for multiple generations to assess potential mutational escape.

- Efficacy Testing: Measure cell viability after kill-switch activation over time.

Expected Results: Effectively engineered strains should show >99% cell death within 24-48 hours of kill-switch activation. Strains should maintain genetic stability for at least 50-100 generations without accidental activation [19].

Essential Pathways and Workflows

BHR Engineering Workflow

Compressed Genetic Circuit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in BHR Synthetic Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Broad-Host-Range Vectors | SEVA vectors, pBBR1, IncP/IncQ plasmids [11] [20] | Enable genetic material maintenance across diverse bacterial species |

| Modular Genetic Parts | BHR promoters, RBS libraries, terminators | Provide standardized, interoperable components that function across multiple hosts |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors | Engineered repressors/anti-repressors (e.g., CelR variants) [13] | Enable orthogonal genetic control circuits responsive to specific inducters |

| Circuit Compression Systems | T-Pro (Transcriptional Programming) components [13] | Reduce genetic footprint and metabolic burden through minimized part count |

| Chassis-Specific Tools | Codon-optimized transporter genes (e.g., LacY) [20] | Address specific functional gaps in non-model organisms |

| Safety Modules | Kill-switches, auxotrophic mutations [19] | Containment systems to prevent environmental spread of engineered microbes |

Building Universal Genetic Circuits: Modular Design and Orthogonal Parts

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the core modules of a universal genetic circuit and why is this architecture needed?

Answer: A universal genetic circuit is designed to function predictably across diverse microbial hosts, moving beyond traditional model organisms like E. coli. This architecture is necessary because transferring circuits from the lab to the field often requires using non-model chassis with unique metabolisms or environmental adaptations. However, host-specific machinery, metabolism, and genetic context can hinder predictable circuit transplantation [22]. The three core modules are:

- Power Supply Module: Encodes heterologous gene expression machinery that is orthogonal to the host's native machinery, providing a standardized and predictable source of cellular resources [22].

- Processor Module: Programs the input-output relationship of the circuit, enabling precise control of target gene expression. This is where the core logic of the circuit is executed [22].

- Controller Module: Acts to decouple the synthetic circuit from variations in host contexts, ensuring robust performance regardless of the specific cellular environment [22].

FAQ 2: My genetic circuit works inE. colibut fails in a production chassis. What is the most likely cause?

Answer: The most likely cause is the "chassis effect," where the same genetic construct exhibits different behaviors in different host organisms [11]. This occurs due to several context-dependent factors:

- Resource Competition: The host's native systems and your synthetic circuit compete for finite cellular resources, such as RNA polymerase, ribosomes, and metabolites [12] [11].

- Metabolic Burden: Expression and replication of foreign genes impose a metabolic load on the host, which can slow growth and select for non-functional mutants that have a growth advantage [23].

- Regulatory Crosstalk: Host transcription factors or other regulatory elements may interact unpredictably with your circuit's parts [24] [11].

- Differences in Genetic Machinery: Variations in transcription/translation machinery or promoter recognition between hosts can lead to unexpected circuit behavior [25] [11].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Characterize Host-Specific Parameters: First, measure key parameters like promoter strength and part performance in your target chassis to establish a baseline [25].

- Reframe the Chassis as a Design Parameter: Do not treat the host as a passive platform. Instead, proactively select a chassis based on its innate traits (e.g., photosynthesis, stress tolerance) that align with your application [11].

- Implement a Controller: Use insulation devices or feedback control systems, as detailed in the Controller Module section, to make your circuit's function robust to host-specific fluctuations [24] [22].

- Minimize Homologous Sequences: Re-engineer your circuit to remove repeated sequences (e.g., identical terminators or promoters), as these are hotspots for recombination that lead to evolutionary failure [23].

FAQ 3: How can I make my genetic circuit more stable over many generations?

Answer: Evolutionary stability is a common challenge, as circuits can lose function in less than 50 generations without selective pressure [23]. To enhance robustness:

- Reduce Metabolic Burden: High expression levels exponentially decrease evolutionary half-life. Use the lowest effective expression level for your circuit components [23].

- Eliminate Sequence Repeats: Avoid repeated sequences in biological parts (e.g., terminators, operators) to prevent recombination-based deletions [23].

- Use Inducible Promoters: Circuits with inducible promoters generally show greater stability than those with constitutive promoters [23].

- Design with Orthogonal Parts: Utilize synthetic transcription factors and promoters that do not cross-talk with the host's native regulatory networks [13].

Experimental Protocols for Core Module Implementation

Protocol 1: Engineering a Synthetic Anti-Repressor for Processor Module Expansion

Objective: To create a set of ligand-responsive anti-repressors, which are key components for building compressed logic circuits in the Processor Module [13].

Materials:

- Template DNA for the repressor protein scaffold (e.g., CelR for cellobiose responsiveness).

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit.

- Error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) kit.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) equipment.

- Synthetic promoter library with tandem operator designs.

Methodology:

- Select a High-Performing Repressor Scaffold: Identify a synthetic repressor from a library that shows high dynamic range and a strong ON-state in the presence of its cognate ligand [13].

- Generate a Super-Repressor Variant: Perform site-saturation mutagenesis on the wild-type repressor to create a variant that retains DNA binding but is insensitive to the input ligand. Screen for mutants that repress target promoters even in the presence of the ligand [13].

- Perform Error-Prone PCR: Use the super-repressor as a template for EP-PCR at a low mutation rate to generate a diverse library of variants (~10^8 clones) [13].

- Screen for Anti-Repressor Phenotype: Use FACS to screen the mutant library for cells that exhibit the desired anti-repressor function—i.e., activation of gene expression in the presence of the ligand. Isolate unique anti-repressor clones (e.g., EA1TAN, EA2TAN) [13].

- Validate Orthogonality: Equip the validated anti-repressors with different Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) domains and test them against a library of synthetic promoters to confirm orthogonal function and expand the programmability of your Processor Module [13].

Protocol 2: Algorithmic Enumeration for Compressed Circuit Design (Processor Module)

Objective: To computationally identify the smallest possible genetic circuit (compression) that implements a desired truth table or logic operation [13].

Materials:

- Computer with a computational biology software environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python).

- Library of characterized biological parts (promoters, genes, RBS, terminators).

Methodology:

- Generalize Part Descriptions: Model synthetic transcription factors and their cognate promoters in a way that allows for a large number of orthogonal protein-DNA interactions [13].

- Model as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG): Represent the genetic circuit as a DAG, where nodes are parts and edges are regulatory interactions [13].

- Systematic Enumeration: Use an algorithm to enumerate all possible circuits in sequential order of increasing complexity, where complexity corresponds to the number of parts used. This guarantees that the first viable solution found is the most compressed design for a given truth table [13].

- Solution Mapping: The algorithm will output the most compressed genetic circuit design that matches your specified logical operation, significantly reducing the number of parts and metabolic burden compared to canonical designs [13].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Circuit Design Strategies

| Design Strategy | Key Metric | Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) | Circuit Size Reduction | ~4x smaller than canonical inverter-type circuits | [13] |

| T-Pro with Model-Guided Design | Quantitative Prediction Error | Average error below 1.4-fold for >50 test cases | [13] |

| Evolutionary Robust Design | Evolutionary Half-Life Improvement | >17-fold increase by reducing homology and lowering expression | [23] |

Table 2: Comparison of Regulatory Modalities for Processor Modules

| Regulator Class | Example Components | Key Features | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Proteins | TetR, LacI, TALEs, ZFPs [12] | Well-established, used for dynamic circuits (oscillators, switches) [12] | Basic logic gates, analog computing, dynamic circuits [12] |

| CRISPRi/a | dCas9, guide RNAs [12] | Highly designable RNA-DNA targeting; can be used for repression (i) or activation (a) [12] | Large-scale circuits, multiplexed regulation [12] |

| Invertases | Serine integrases (e.g., Bxb1) [12] | Permanent, stable memory storage; slow reaction times [12] | Memory circuits, sequential logic [12] |

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (T-Pro) | Anti-repressors (e.g., EA1TAN), Synthetic Promoters [13] | Enables circuit compression, high orthogonality, reduced part count [13] | Complex Boolean logic, higher-state decision-making with minimal footprint [13] |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Universal Genetic Circuit Architecture

Title: Core Modules for Universal Circuit Function

Diagram 2: Chassis Selection and Engineering Workflow

Title: BHR Synthetic Biology Design Workflow

Diagram 3: Anti-Repressor Engineering Protocol

Title: Engineering Anti-Repressor Transcription Factors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Universal Circuit Design

| Item | Function/Description | Application in Core Modules |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (TFs) | Engineered repressors and anti-repressors with Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) domains [13]. | Processor Module: Core components for building compressed Boolean logic gates. |

| Orthogonal Polymerases/RNAPs | Heterologous gene expression machinery (e.g., T7 RNAP) that does not interact with host machinery [25] [22]. | Power Supply Module: Provides a standardized, host-agnostic source for transcription. |

| Synthetic Promoter Library | A collection of promoters with engineered operator sequences for orthogonal TFs [13]. | Processor Module: Defines the input-output relationship and logic of the circuit. |

| Broad-Host-Range (BHR) Vectors | Plasmid vectors with origins of replication and genetic parts that function across diverse microbes (e.g., SEVA plasmids) [11]. | All Modules: Enables the physical transplantation and maintenance of circuits in non-model chassis. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 System | Catalytically dead Cas9 fused to activator/repressor domains, programmed with guide RNAs [12]. | Processor Module: Offers a highly designable method for transcriptional regulation in large circuits. |

| Serine Integrases | Unidirectional site-specific recombinases (e.g., Bxb1) that flip DNA segments [12]. | Processor Module: Used to construct permanent memory circuits and sequential logic. |

Technical Support Center

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists essential reagents for engineering orthogonal transcription systems, drawing from recent advances in the field.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example & Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factors (TFs) | Programmable proteins that bind specific DNA sequences to activate or repress gene expression. | dCas9-VPR: CRISPR-based activator; stronger than VP16/VP64 [26].T-Pro Anti-Repressors: Enable circuit "compression" by performing NOT logic without inverter cascades [13]. |

| Engineered Promoters | Synthetic DNA sequences that are recognized by synthetic TFs to initiate transcription. | T-Pro Synthetic Promoters: Contain tandem operators for coordinated TF binding [13].Cross-Species (Psh) Promoters: Function in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic chassis [27]. |

| Orthogonal Inducer Molecules | Small molecules that trigger synthetic TF activity without interfering with native cellular processes. | Cellobiose, IPTG, D-ribose: Three orthogonal signals for 3-input Boolean logic circuits [13]. |

| Reporters for Characterization | Genes with easily measurable outputs used to quantify promoter strength and circuit function. | Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP, mKate, RFP): Enable quantitative measurement via flow cytometry or microscopy [26] [28].Gaussia Luciferase (gLuc): A sensitive reporter for detecting low levels of leaky expression [29]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ Category 1: Designing Systems for Predictable Performance

Q: My synthetic circuit behaves unpredictably in a new host chassis. What could be wrong? A: A lack of orthogonality and context-dependent performance are likely culprits.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Part Orthogonality: Ensure your synthetic transcription factors and promoters do not cross-react with the host's native regulatory networks. Use tools like BLAST to check for unintended sequence homology.

- Characterize Parts in Context: Always characterize your specific promoter-TF pairs within your target chassis. Performance in E. coli does not guarantee similar function in S. cerevisiae or a mammalian cell.

- Consider Cross-Species Parts: If working across diverse microbes, investigate the use of recently engineered broad-spectrum promoters (e.g., Psh series) designed for functionality in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells [27].

Q: How can I reduce the high metabolic burden of my complex genetic circuit? A: Metabolic burden is a common issue that limits scalability.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Circuit Compression: Adopt methodologies like Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro), which uses synthetic anti-repressors to implement logical operations with fewer genetic parts. This can create circuits that are approximately 4-times smaller than canonical designs [13].

- Optimize Copy Number and Promoter Strength: Use low-copy-number plasmids and avoid excessively strong constitutive promoters for regulator expression, which can drain cellular resources.

FAQ Category 2: Optimizing Expression and Noise

Q: My inducible system has high background expression (leakiness) even without the inducer. How can I fix this? A: Leakiness is a fundamental challenge in inducible systems and can be mitigated with advanced circuit design.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement a Feed-Forward Circuit: Integrate a post-transcriptional control layer. The CASwitch system, which combines the Tet-On3G inducible system with the CasRx endoribonuclease, can reduce leakiness by over 1-log (more than 10-fold) compared to the standard system [29].

- Engineer the Promoter: If not using a complex circuit, perform directed evolution or rational design on your promoter's operator sequences to tighten repression. Deep learning models can now assist in predicting the effect of sequence changes on promoter strength and specificity [30].

Q: I need precise, tunable control over gene expression levels. What is the best strategy? A: Fine control can be achieved by designing a comprehensive system with multiple tuning knobs.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Vary Guide RNA and Binding Sites: In CRISPR-based transcription systems, you can tune output over a wide dynamic range (e.g., ~74-fold) by using different gRNA sequences and varying the number of corresponding binding sites (e.g., from 2x to 16x) in the synthetic operator [26].

- Leverage Promoter Libraries: For non-CRISPR systems, use or create libraries of synthetic promoters with varying strengths, for instance, by changing the number or sequence of transcription factor binding sites upstream of a core promoter [31].

FAQ Category 3: Characterization and Validation

Q: What is the best way to quantitatively characterize a new synthetic promoter? A: Accurate characterization is key to predictability.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Clone Promoter: Fuse the candidate promoter to a reporter gene (e.g., GFP, mKate, luciferase).

- Transfert/Transform: Introduce the construct into your target host cells. For mammalian cells, use a consistent transfection method and include a normalization plasmid (e.g., constitutively expressing a different fluorescent protein) to control for variability.

- Measure Output: Use flow cytometry for single-cell resolution of fluorescent reporters or a plate reader for bulk measurements of fluorescence/luminescence.

- Calculate Metrics: Determine key performance metrics:

- Strength: Mean fluorescence of the population.

- Leakiness: Output in the "OFF" state (e.g., without inducer or TF).

- Dynamic Range: Ratio of "ON" state (with inducer) to "OFF" state output.

- Compare to Benchmarks: Always include a well-characterized reference promoter (e.g., EF1α, CMV) in your experiments for comparison [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantitative Characterization of a Synthetic Promoter

Objective: To measure the strength and leakiness of a newly designed synthetic promoter in a mammalian cell line (e.g., HEK293T).

Materials:

- Plasmid DNA: Test plasmid (synthetic promoter driving GFP/mKate), Reference plasmid (constitutive promoter driving a different fluorophore, e.g., EF1α-mCherry).

- Cells: HEK293T cells.

- Reagents: Transfection reagent, cell culture media, PBS, trypsin.

- Equipment: Flow cytometer, cell culture incubator, biosafety cabinet.

Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed HEK293T cells in a 24-well plate at a density of 1 x 10^5 cells per well and incubate for 24 hours to reach ~70-80% confluency.

- Transfection: Co-transfect each well with a fixed total amount of DNA, maintaining a consistent molar ratio between the test plasmid and the reference plasmid (e.g., 1:1). Include replicates and a mock transfection control.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for 48 hours post-transfection to allow for gene expression.

- Harvesting and Analysis:

- Harvest the cells using trypsin, resuspend in PBS containing a viability dye, and filter through a cell strainer.

- Analyze using a flow cytometer. Gate for single, live cells.

- For each cell in the gated population, measure the fluorescence from both the test reporter (e.g., GFP) and the reference reporter (mCherry).

- Data Processing:

- The ratio of test fluorescence to reference fluorescence for each cell corrects for transfection efficiency and cell-to-cell variation.

- Report the population's median fluorescence ratio. Compare this normalized value across different promoters to assess relative strength [26].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Low-Leakiness Inducible System (CASwitch)

Objective: To set up the CASwitch system for inducible expression of a gene of interest with minimal background.

Materials:

- Plasmids: pCMV-rtTA3G (expresses the Tet-On 3G transactivator), pCMV-CasRx (expresses the CasRx endoribonuclease), pTRE3G-GOI-DR (your gene of interest with a direct repeat (DR) motif in its 3'UTR, under the control of the TRE3G promoter).

- Inducer: Doxycycline.

- Cells: HEK293T cells.

- Equipment: Luminescence plate reader (if using a luciferase reporter).

Methodology:

- Circuit Assembly: The system consists of three core components expressed from separate plasmids.

- Transfection: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the three plasmids at an optimized molar ratio (e.g., 1:5:1 for pCMV-rtTA3G : pTRE3G-gLuc-DR : pCMV-CasRx) [29].

- Induction: At 24 hours post-transfection, treat cells with a range of doxycycline concentrations (e.g., 0 ng/mL to 1000 ng/mL).

- Output Measurement: At 48 hours post-transfection, measure the output (e.g., luciferase activity).

- Validation: Compare the leakiness (no doxycycline) and maximum expression (saturating doxycycline) of the CASwitch to a standard Tet-On3G system (which uses a pTRE3G-GOI construct without the DR motif).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Inducible Expression Systems

| System | Key Mechanism | Typical Fold Reduction in Leakiness | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Tet-On3G | Single-layer transcriptional control | (Baseline) | Well-characterized, simple | [29] |

| CASwitch v.1 | Combines Tet-On3G with CasRx-mediated mRNA degradation | >10-fold | Drastically reduced leakiness while maintaining high output | [29] |

| T-Pro Compression | Uses anti-repressors for logic, reducing part count | N/A | ~4x smaller circuit size; reduced metabolic burden | [13] |

Table 2: Tuning Knobs for CRISPR-Based Synthetic Promoters

| Parameter to Tune | Effect on Expression | Experimental Range | Observed Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gRNA Seed GC Content | Alters binding efficiency/strength | ~50-60% optimal | Up to 25x stronger than EF1α promoter | [26] |

| Number of gRNA Binding Sites | Increases activator recruitment | 2x to 16x sites | ~74-fold dynamic range in output | [26] |

| CRISPR-activator Type | Changes transcriptional activation potency | dCas9-VP16, -VP64, -VPR | dCas9-VPR showed markedly higher expression | [26] |

System Architecture and Troubleshooting Diagrams

Diagram: CASwitch System for Low-Leakiness Expression

Diagram Title: CASwitch System Mechanism for Low-Leakiness Expression

Diagram: T-Pro Circuit Compression Logic

Diagram Title: T-Pro Circuit Compression Reduces Component Count

What is the fundamental challenge that T-Pro and circuit compression aim to solve? As synthetic genetic circuits increase in size and complexity, they impose a significant metabolic burden on the host chassis cell. This burden manifests as stress symptoms such as decreased growth rate, impaired protein synthesis, and genetic instability, which ultimately limit circuit performance and scalability [9]. Transcriptional Programming (T-Pro) addresses this by developing compressed genetic circuits that achieve higher-state decision-making (complex logic operations) using fewer genetic parts compared to conventional designs [32] [33]. This compression reduces the load on cellular resources, thereby improving circuit predictability and host viability.

How does reducing metabolic burden align with the broader thesis of improving genetic circuit predictability? Circuit predictability is confounded by the complex interplay between a synthetic circuit and its host. High metabolic burden creates selective pressure for mutant cells that evade this burden, leading to circuit failure over time [34]. Furthermore, burden-induced stress responses can alter host physiology in unpredictable ways, changing the effective parameters of circuit components [9] [34]. By minimizing the genetic footprint and resource demand of circuits, T-Pro's compression technology reduces these context-dependent interactions, leading to more robust and predictable circuit behaviors across different chassis and experimental conditions [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on T-Pro Fundamentals

FAQ 1: What is the core technological innovation that enables circuit compression in T-Pro? The core innovation is the use of synthetic transcription factors (TFs) and cognate synthetic promoters that facilitate coordinated binding. Unlike conventional designs that often rely on inversion to achieve NOT/NOR Boolean operations, T-Pro utilizes engineered repressor and anti-repressor TFs. These TFs bind to synthetic promoters in a way that directly implements logical operations, thereby reducing the number of promoters and regulators required [33]. This parts reduction is the essence of circuit compression.

FAQ 2: How does T-Pro scale from 2-input to 3-input Boolean logic? Scaling logic requires developing orthogonal sets of synthetic TFs responsive to different signals. A complete 2-input system requires two orthogonal repressor/anti-repressor sets (e.g., responsive to IPTG and D-ribose) to achieve 16 Boolean operations [33]. Expanding to 3-input logic (256 operations) necessitates a third, orthogonal set. Recent work has engineered such a set using the CelR scaffold, which is responsive to the ligand cellobiose and has been shown to be orthogonal to the IPTG and D-ribose systems [33].

FAQ 3: What is a "quantitative setpoint" and why is it important for predictability? A quantitative setpoint is a prescriptive, pre-determined level of gene expression or circuit output (e.g., a specific fluorescence value or enzyme activity level). A major challenge in synthetic biology is the discrepancy between qualitative circuit design (e.g., ON/OFF states) and quantitative performance prediction [33]. Advanced T-Pro workflows now incorporate modeling that accounts for genetic context, enabling the design of circuits that not only perform the correct logic but also hit desired quantitative expression targets. This is crucial for applications like metabolic engineering, where precise flux control is needed [33].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Problem: High Basal Expression (Leakiness) in Compressed Circuits

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Repressor Dynamic Range | Measure the input/output transfer function of the repressor in isolation. A low ON/OFF ratio indicates a weak repressor. | • Screen for or engineer super-repressor variants with lower OFF-state activity [33]. • Incorporate transcriptional terminator filters upstream of the gene to reduce leaky transcription [35]. |

| Promoter-Operator Mismatch | Test the synthetic promoter with a panel of orthogonal TFs to check for non-specific interaction. | • Re-engineer the synthetic promoter's operator sequence for stricter orthogonality [33]. • Use algorithmic enumeration software to identify an alternative, more orthogonal circuit architecture for the same truth table [33]. |

| Resource Competition & Context Effects | Co-express a resource-insensitive reporter (e.g., from a constitutive promoter) to monitor global translational capacity [9]. | • Implement a CRISPRi-aided genetic switch to tighten regulation. The FnCas12a system, for instance, can process crRNAs from sensor transcripts for precise, signal-dependent repression with reduced leakiness [35]. |

Problem: Unpredictable Circuit Performance or Output Drift

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Burden-Induced Stress | Monitor host cell physiology: track growth rate, cell size, and culture viability over time [9]. | • Further compress the circuit design using algorithmic enumeration to minimize its genetic footprint [33]. • Adopt a division-of-labor strategy by splitting the circuit across multiple cell populations to distribute the burden [34]. |

| Uncharged tRNA & Amino Acid Starvation | Measure the activation of the stringent response by detecting alarmone (ppGpp) levels [9]. | • Perform codon harmonization instead of wholesale codon optimization. This preserves rare, translation-slowing codons that may be critical for proper protein folding, reducing misfolded proteins that trigger stress [9]. |

| Genetic Instability & Mutant Selection | Sequence the circuit plasmid from populations after long-term cultivation to identify common loss-of-function mutations. | • Use additive strains or media supplements that provide essential nutrients depleted by heterologous protein production. • Implement toxin-antitoxin systems or other post-segregational killing mechanisms on the circuit plasmid to penalize plasmid loss [34]. |

Problem: Failure to Scale to 3-Input Logic Gates

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Component Crosstalk | Characterize all new synthetic TF-promoter pairs in a pairwise fashion to build a full orthogonality matrix. | • Utilize the expanded T-Pro wetware toolkit, which includes synthetic TFs with Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) domains engineered for high orthogonality [33]. • Decouple parts by importing TFs from distantly related species or by using completely synthetic, reprogrammed DNA-binding domains [34]. |

| Combinatorial Design Complexity | Manually attempt to design a simple 3-input gate and note where the logic breaks down. | • Employ the algorithmic enumeration-optimization software developed for T-Pro. This software systematically searches the vast combinatorial space to guarantee the identification of the smallest (most compressed) circuit for any given 3-input truth table [33]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key T-Pro Workflows

Protocol: Engineering a Synthetic Anti-Repressor

This protocol outlines the creation of a signal-responsive anti-repressor, a core component of T-Pro compression [33].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Parent Repressor Scaffold (e.g., E+TAN CelR) | Serves as the starting protein for engineering. It must have a well-characterized DNA-binding function and ligand response. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Kit | Used to generate a super-repressor variant (ligand-insensitive but still DNA-binding) by targeting specific amino acid positions. |

| Error-Prone PCR (EP-PCR) Kit | Used to introduce random mutations into the super-repressor template to generate a library of potential anti-repressors. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Essential for high-throughput screening of the mutant library based on the desired anti-repressor phenotype (e.g., OFF in the absence of ligand, ON in its presence). |

Methodology:

- Generate a Super-Repressor Variant: Perform site-saturation mutagenesis on the parent repressor (e.g., CelR) at key amino acid positions known to affect ligand binding (e.g., position 75). Screen for variants that constitutively repress their target promoter, regardless of the ligand's presence. The variant L75H (designated ESTAN) is an example [33].

- Create an Anti-Repressor Library: Use error-prone PCR on the super-repressor gene (e.g., ESTAN) at a low mutational rate to generate a library of ~10^8 variants.

- FACS Screening: Clone the mutant library into an appropriate vector and transform into the host chassis. Use FACS to screen and isolate cells that exhibit the anti-repressor phenotype. For a CelR-based anti-repressor, this would be low fluorescence without cellobiose (OFF state) and high fluorescence with cellobiose (ON state) [33].

- Characterization and ADR Expansion: Sequence unique anti-repressor hits (e.g., EA1TAN, EA2TAN). To enable their use with multiple synthetic promoters, equip the best-performing anti-repressor core with four to five additional Alternate DNA Recognition (ADR) domains (e.g., EAYQR, EANAR) and verify that the anti-repressor phenotype is retained with each [33].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the anti-repressor engineering process:

Protocol: Predictive Design of a Compression Circuit

This protocol describes the use of software to design a compressed genetic circuit with a predictable quantitative output [33].

Methodology:

- Define the Truth Table: Precisely specify the desired logic operation by defining the output state (e.g., "1" for ON, "0" for OFF) for every possible combination of inputs.

- Algorithmic Enumeration: Input the truth table into the T-Pro circuit enumeration software. The algorithm models circuits as directed acyclic graphs and systematically explores designs in order of increasing complexity, guaranteeing the identification of the most compressed (smallest) circuit that satisfies the logic [33].

- Incorporate Quantitative Context: Use complementary software workflows that account for genetic context (e.g., promoter strength, RBS efficiency, gene order) to predict the quantitative expression level of the circuit output.

- DNA Assembly and Transformation: Assemble the designed circuit using standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., Gibson Assembly) and transform it into the chassis cell.

- Validation and Iteration: Measure the circuit's quantitative output (e.g., fluorescence) and compare it to the software prediction. If necessary, fine-tune the circuit by selecting parts with different strengths from a characterized library to hit the desired setpoint.

The diagram below illustrates the predictive design cycle for T-Pro circuits:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents and their functions in T-Pro circuit construction and analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in T-Pro Research |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Transcription Factor Kits | • IPTG-responsive repressor/anti-repressor set• D-ribose-responsive set• Cellobiose-responsive (CelR) set [33] | Core wetware for constructing orthogonal, signal-responsive circuits. Enable the direct implementation of logic without cascading inverters. |

| Synthetic Promoter Library | Promoters with tandem operator sites for coordinated TF binding (e.g., for E+TAN, EA1YQR TFs) [33] | Cognate DNA targets for synthetic TFs. The library provides a range of expression strengths and specificities for different circuit nodes. |

| Algorithmic Circuit Design Software | T-Pro circuit enumeration-optimization software [33] | Critical for navigating the combinatorial complexity of 3-input circuits. Guarantees the discovery of the most compressed design for any truth table. |

| CRISPRi-Aided Switch Components | Vectors for FndCas12a (nuclease-deficient), terminator filters, crRNA scaffolds [35] | Tool for reducing leakiness and improving dynamic range. The RNase activity of FndCas12a allows processing of crRNAs from sensor transcripts. |

| Characterized Part Libraries | Registry of Standard Biological Parts, Marionette strains with optimized sensors [34] [36] | Libraries of well-characterized biological parts (promoters, RBS, terminators) that facilitate decoupling, standardization, and predictable tuning. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is Genetic Design Automation (GDA), and how does it relate to tools like Cello? GDA refers to software tools that automate the design of genetic circuits, much like electronic design automation (EDA) for computer chips. Cello is a pioneering GDA tool that allows users to specify a desired logic function in Verilog, a hardware description language. The software then automatically synthesizes a DNA sequence that implements this function in a living cell, such as E. coli, by assembling characterized genetic parts like promoters and repressors [37] [38].

FAQ 2: A significant portion of my circuits fail to function as predicted in vivo. What are the primary causes? Circuit failure often stems from biological uncertainties and context dependence. Key issues include:

- Metabolic Burden: The synthetic circuit competes with the host cell for limited resources like ribosomes and polymerases. This can inhibit cell growth and alter circuit performance, creating an unpredictable feedback loop [39].

- Part Context-Dependence: The function of a well-characterized genetic part can change unpredictably when placed in a new genetic context or a different host chassis due to unintended interactions [39].

- Stochastic Noise: Biochemical reactions involve small numbers of molecules, leading to significant cell-to-cell variability (noise) in gene expression. This can disrupt circuits designed with deterministic models [39].

- Component Crosstalk: A lack of perfect orthogonality means that regulatory components (e.g., transcription factors) may unintentionally interact with each other or with the host's native systems [40].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the robustness and predictability of my genetic circuits?

- Utilize Robust Scoring: Newer GDA approaches incorporate scores that account for cell-to-cell variability. When selecting a circuit design from options, choose the one with a higher robustness score, which ensures the circuit's "ON" and "OFF" output states are distinct even with parameter fluctuations [40].