Beyond FBA: Next-Generation Approaches for Accurate Quantitative Phenotype Prediction

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has long been a cornerstone for predicting metabolic phenotypes, yet its quantitative accuracy is limited by assumptions like static objective functions and the omission of proteomic...

Beyond FBA: Next-Generation Approaches for Accurate Quantitative Phenotype Prediction

Abstract

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has long been a cornerstone for predicting metabolic phenotypes, yet its quantitative accuracy is limited by assumptions like static objective functions and the omission of proteomic constraints. This article explores the cutting-edge computational strategies being developed to overcome these hurdles. We cover foundational limitations of traditional FBA, delve into innovative methodologies from hybrid neural-mechanistic models to machine learning frameworks like Flux Cone Learning, and discuss optimization techniques that integrate network topology and resource allocation. Through comparative analysis and validation protocols, we highlight how these advanced methods enhance predictive power for applications in drug discovery and metabolic engineering, offering researchers a roadmap to more reliable, quantitative phenotype predictions.

Why FBA Falls Short: The Core Challenges in Quantitative Phenotype Prediction

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Phenotype Prediction Errors from Flux Inaccuracies

Problem Identification and Diagnosis

Q: Why do my FBA predictions show significant errors in growth rates or metabolic phenotypes even with a well-annotated genome-scale model?

A: Inaccurate conversion of medium composition to uptake fluxes represents a fundamental limitation in constraint-based modeling. Even with a perfectly structured metabolic model, errors in estimating the cellular uptake rates of medium components can lead to incorrect phenotypic predictions. The problem often originates from two primary sources:

Essential Nutrient Over-Restriction: The constraints for essential amino acids or other nutrients can be overly restrictive, with even slight underestimations dictating the entire FBA solution and leading to significant under-prediction of growth rates [1]. In mammalian cell models, a single underestimated essential amino acid uptake rate can become the sole rate-limiting factor for growth prediction [1].

Model-Data Mismatch: Discrepancies between the model's required biomass composition and the experimentally measured uptake fluxes create mass balance violations that the linear programming solver cannot reconcile, often resulting in non-optimal solutions or failed simulations [1].

Diagnostic Procedure:

Researchers should systematically examine their FBA solutions using the following diagnostic workflow to identify the root cause of prediction errors:

Q: How can I identify which specific uptake fluxes are causing prediction errors in my model?

A: The most effective method involves analyzing the dual prices (shadow prices) of the metabolic constraints:

- Run FBA with standard biomass maximization using your current uptake flux constraints

- Extract dual prices for each exchange flux constraint in the solution

- Identify components with positive dual prices - these indicate metabolites whose increased availability would improve the objective function (growth rate) [1]

- Prioritize essential nutrients with high positive dual prices, as these represent the primary rate-limiting factors in your simulation

In cases with CHO cells, researchers found that only the dual prices of lysine and histidine were positive among 23 flux inputs, clearly identifying them as the primary constraints limiting growth predictions [1].

Solution Implementation: Protocols and Methodologies

Q: What protocols can I use to correct for inaccurate essential nutrient uptake constraints?

A: Implement the Essential Nutrient Minimization (ENM) approach, which calculates the minimal uptake requirements to sustain observed growth:

Experimental Protocol: Essential Nutrient Minimization

- Measure experimental growth rate (μ_exp) under defined conditions

- For each essential nutrient, modify the FBA formulation to minimize its uptake rate (vuptakei) while constraining growth to the experimental value:

- Objective: Minimize vuptakei

- Constraints:

- Growth = μ_exp

- All other model constraints

- Record the minimal required uptake rate for each essential nutrient

- Replace original uptake constraints with these ENM-derived values for subsequent FBA analyses [1]

This protocol effectively reverses the standard FBA approach by using the measured growth rate as a constraint to solve for physiologically realistic uptake rates.

Q: What alternative FBA formulations can circumvent issues with uptake flux inaccuracies?

A: The Uptake-rate Objective Functions (UOFs) approach provides a robust alternative to traditional biomass maximization:

Implementation Protocol: UOFs Method

- Apply ENM-derived constraints for all essential nutrients

- Set growth rate constraint to the experimentally observed value

- Independently minimize uptake rate for each non-essential nutrient:

- For each non-essential nutrient i:

- Objective: Minimize vuptakei

- Constraints: Growth = μ_exp, Essential nutrients = ENM values

- This generates a series of FBA solutions revealing metabolic flexibility [1]

- For each non-essential nutrient i:

- Analyze solution spectrum to understand metabolic trade-offs and network capabilities

This approach has been successfully demonstrated with CHO cell models, where it revealed metabolic differences between cell line variants (CHO-K1, -DG44, and -S) that were not observable using conventional biomass maximization [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

Q: Why is the conversion of medium composition to uptake fluxes particularly problematic for mammalian cells compared to microorganisms?

A: Mammalian cells present unique challenges due to their complex nutrient requirements, including multiple essential amino acids and growth factors. The biomass objective function for mammalian cells incorporates numerous essential components, making the solution highly sensitive to inaccuracies in any single uptake constraint. Even a slight underestimation of one essential amino acid can dictate the entire FBA solution, whereas microbial models with fewer essential nutrients demonstrate more robust performance [1].

Q: How do network complexity and model size affect the impact of uptake flux inaccuracies?

A: Larger, more complex models are generally more susceptible to uptake flux errors due to increased network connectivity and interdependencies. Systematic studies with E. coli models of varying complexity (271-327 reactions) demonstrated that metabolic sensitivity coefficients and flux distributions are significantly affected by network size [2]. However, the essential nutrient constraint problem remains critical across all model scales, from core metabolic models to genome-scale reconstructions.

Technical Implementation

Q: What quantitative impact can uptake flux inaccuracies have on phenotype predictions?

A: The effects can be substantial, as demonstrated in this case study with CHO-K1 cells:

Table 1: Impact of Essential Amino Acid Flux Correction on Growth Predictions in CHO Cells

| Condition | Mean Relative Deviation in Growth Predictions | Primary Limiting Factors Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Raw flux inputs | 50.2% | Lysine (3 replicates), Histidine (3 replicates) |

| Averaged lysine constraints | 25.8% | Reduced lysine limitation |

| Averaged histidine constraints | 18.3% | Reduced histidine limitation |

| Averaged lysine & histidine | 10.2% | Multiple minor factors |

Data adapted from [1]

Q: How can I validate that my uptake flux constraints are physiologically realistic?

A: Implement a multi-step validation protocol:

- Compare ENM-predicted minimal uptake rates with experimentally measured consumption rates

- Test prediction sensitivity to small variations (±5-10%) in key uptake constraints

- Verify intracellular flux distributions against 13C-MFA data when available

- Check consistency across technical replicates - high variability in predictions suggests constraint sensitivity [1]

- Validate with unused experimental data - ensure the model can predict outcomes not used in parameterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Metabolic Flux Analysis and Model Construction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Functions | Application in Flux Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | CHO (1766 genes, 6663 reactions) [1], E. coli iJO1366 [2] | Reference networks for constraint-based modeling and simulation |

| Model Reconstruction Software | COBRA Toolbox [3], CellNetAnalyzer [4], ModelBricker [5] | Platform for building, curating, and analyzing metabolic models |

| Model Reduction Algorithms | redGEM, lumpGEM [2] | Systematic creation of thermodynamically feasible reduced models |

| Experimental Data Integration | 13C-MFA, Fluxomics, Metabolomics [2] | Parameterization and validation of model predictions |

| Diagnostic and Validation Tools | Dual price analysis, χ2-test, t-test validation [4] [1] | Identification of limiting constraints and model fit assessment |

Advanced Workflow: Integrated Solution Pathway

For comprehensive resolution of uptake flux inaccuracies, implement this integrated workflow combining computational and experimental approaches:

This workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of model refinement, where solutions are continuously validated against experimental data and constraints are adjusted accordingly. The UOFs approach is particularly valuable for mammalian cells and other complex organisms with multiple distinct essential nutrient inputs, offering enhanced applicability for characterizing cell metabolism and physiology [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Single-Objective FBA Issues

Problem 1: Inaccurate Flux Predictions in Complex Media

- Symptoms: Model predictions deviate significantly from experimental flux data ( [6]) or ¹³C fluxomic measurements ( [7]), especially in nutrient-rich environments.

- Root Cause: The model uses a single objective (e.g., biomass maximization), but cellular metabolism is simultaneously subject to multiple constraints (e.g., on uptake rates of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus), leading to a solution that is a compromise between competing yield efficiencies ( [8]).

- Solution:

- Perform a phenotype phase plane analysis to visualize how the optimal solution changes with varying nutrient availability ( [8]).

- Transition to a multi-objective optimization framework or use methods like Elementary Conversion Modes (ECMs) to rationalize the selected flux distribution based on a weighted combination of yields ( [8]).

- Implement the TIObjFind framework, which integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to infer a weighted objective function that better aligns with experimental data ( [6] [9]).

Problem 2: Failure to Capture Metabolic Shifts or Overflow Metabolism

- Symptoms: The model does not predict well-known phenomena like aerobic fermentation (the "Crabtree effect") or other diauxic shifts, instead sticking to a theoretically high-yield pathway ( [8]).

- Root Cause: Single-objective FBA with one constraint inherently selects the metabolic pathway with the highest biomass yield per unit of limiting substrate. It does not account for kinetic or thermodynamic constraints that may favor higher-flux, lower-yield pathways under certain conditions ( [8]).

- Solution:

- Introduce additional constraints informed by experimental data, such as a lower bound on ATP maintenance or constraints on enzyme capacities ( [8]).

- Use Dynamic FBA (dFBA) to model time-varying environments and resource depletion, which can naturally lead to metabolic shifts ( [6]).

- Employ NEXT-FBA, a hybrid approach that uses neural networks trained on exometabolomic data to derive biologically relevant constraints for intracellular fluxes, improving prediction of metabolic shifts ( [7]).

Problem 3: Model Predictions Are Sensitive to Small Changes in Constraints

- Symptoms: A minor adjustment in a single uptake rate constraint leads to a drastic and discontinuous change in the predicted flux distribution ( [8]).

- Root Cause: The solution space defined by the single objective has sharp corners. The optimal solution may jump between different Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs) with similar yields but different pathway usages ( [8]).

- Solution: Conduct a robustness analysis by systematically varying the constraint in question and plotting the objective value and key fluxes. This helps identify the range of constraint values for which the solution is stable and reveals critical tipping points ( [8]).

Problem 4: Poor Generalization of Parameters Across Conditions

- Symptoms: Model parameters (e.g., metabolite release or consumption rates) measured in one condition (e.g., batch culture with excess nutrients) fail to accurately predict community or culture behavior in a different, metabolite-limited environment ( [10]).

- Root Cause: Phenotype parameters are not constant; they can vary significantly with the metabolite environment and can be affected by rapid evolution ( [10]).

- Solution: Re-measure critical phenotype parameters in environments that mimic the intended application of the model, such as in chemostats that simulate metabolite-limited growth, to obtain more accurate and generalizable parameters ( [10]).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: If single-objective optimization is limited, why is maximizing biomass yield so widely used in FBA? A1: Biomass maximization is a simple and effective proxy for evolutionary pressure to grow faster. It has proven successful in predicting the metabolic behavior of single microbes in simple, nutrient-limited environments. Its widespread use is due to its simplicity and historical success, but it is recognized as an oversimplification for complex conditions ( [8] [6]).

Q2: What is the fundamental conceptual difference between single- and multi-objective optimization? A2: A Single-Objective Optimization Problem finds the single best solution for one specific criterion or a weighted sum of several criteria. In contrast, multi-objective optimization treats multiple, often conflicting, objectives separately. It identifies a set of Pareto-optimal solutions, where no objective can be improved without worsening another, leaving the final choice to the researcher ( [11] [12]).

Q3: My model has many constraints. Does that mean I am already doing multi-objective optimization? A3: No, there is a key distinction. Constraints define the feasible space of possible solutions. The objective function defines the goal used to select the "best" single solution from that space. A model can have many constraints but still aim to optimize a single objective. Multi-objective optimization involves explicitly defining and balancing multiple goals ( [8] [11]).

Q4: Are there simple algorithms to move beyond single-objective optimization? A4: Yes, one common approach is scalarization, which reformulates a multi-objective problem into a parametric single-objective problem, for example, by creating a weighted sum of the individual objectives. The weights then become the parameters that can be varied to explore the trade-offs ( [11] [12]).

Key Comparative Data

Table 1: Common Objective Functions in Metabolic Modeling and Their Limitations

| Objective Function | Typical Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | Predicting growth rates and phenotypes in nutrient-limited conditions ( [8]) | Fails to predict overflow metabolism; inaccurate in nutrient-rich environments ( [8]) |

| ATP Maximization | Studying energy metabolism | Often predicts unrealistic flux distributions without a biosynthetic goal |

| Product Yield Maximization | Metabolic engineering for chemical production | May predict unachievable yields without considering growth or other cellular demands |

| Weighted Sum of Fluxes | Aligning model with data using frameworks like ObjFind/TIObjFind ( [6] [9]) | Risk of overfitting to specific conditions; requires experimental flux data ( [6]) |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Tool Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Computational Framework | A stoichiometric matrix representing all known metabolic reactions in an organism; the core structure for FBA ( [8] [7]) |

| ecmtool | Software | Enumerates Elementary Conversion Modes (ECMs), allowing large-scale analysis of metabolic network capabilities ( [8]) |

| TIObjFind | Computational Framework | Integrates FBA and Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) to infer context-specific objective functions from data ( [6] [9]) |

| NEXT-FBA | Computational Methodology | Uses neural networks trained on exometabolomic data to derive improved constraints for intracellular flux predictions ( [7]) |

| Chemostat | Bioreactor | Provides a constant, nutrient-limited environment for measuring phenotype parameters under conditions relevant to community models ( [10]) |

Experimental Protocol: Inferring a Context-Specific Objective Function with TIObjFind

Purpose: To replace a generic single objective function with a weighted combination of fluxes that better explains experimental data. Background: The TIObjFind framework posits that cells optimize a weighted sum of fluxes rather than a single flux. The "Coefficients of Importance" (CoIs) are weights that quantify each reaction's contribution to the cellular objective ( [6] [9]).

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Gather the following:

- A genome-scale metabolic model (stoichiometric matrix, reaction bounds).

- Experimentally measured extracellular uptake/secretion rates (

v_exp) for the condition of interest. - (Optional) Intracellular flux data from ¹³C labeling experiments for validation.

Single-Stage Optimization:

- Formulate and solve an optimization problem that, for a candidate set of Coefficients of Importance (

c), minimizes the squared difference between the FBA-predicted fluxes (v) and the experimental data (v_exp), subject to the model's stoichiometric constraints ( [9]). - This step finds the best-fit flux distribution for a hypothesized objective.

- Formulate and solve an optimization problem that, for a candidate set of Coefficients of Importance (

Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Construction:

Pathway Analysis and Coefficient Calculation:

- Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) on the MFG to identify the critical pathways connecting a source (e.g., glucose uptake) to a target (e.g., product formation). The algorithm identifies the bottleneck reactions that are most important for the flux to the target ( [9]).

- The results of this analysis are used to compute the final Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which serve as pathway-specific weights in the objective function ( [6] [9]).

Validation: Compare the intracellular fluxes predicted using the new, weighted objective function against independent ¹³C fluxomic data to assess improvement over the single-objective model ( [6] [7]).

Conceptual Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: TIObjFind Framework Workflow

Diagram 2: Single vs. Multi-Objective Outcome Logic

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone computational method for predicting metabolic phenotypes in biotechnology and drug development. This constraint-based approach uses stoichiometric models and optimization principles to predict metabolic flux distributions that maximize cellular objectives, typically growth rate [13]. However, traditional FBA implementations often overlook a critical biological reality: proteomic costs. Every enzymatic reaction requires protein synthesis, and cells have limited resources for protein production. The omission of enzyme kinetics and proteome allocation constraints represents a significant limitation, leading to predictions that may not reflect actual cellular behavior.

The fundamental challenge arises because microorganisms operate under finite proteomic resources. When models ignore the metabolic costs of producing and maintaining enzymes, they often overpredict growth rates and misrepresent metabolic fluxes [14] [15]. This is particularly problematic for quantitative phenotype predictions in academic research and industrial applications, where accurate forecasting of microbial behavior is essential. This technical support guide addresses these limitations through troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and experimental protocols to enhance model predictive accuracy.

Key Concepts and Terminology

Proteome Efficiency and Metabolic Pathways

Proteome efficiency refers to the ratio between minimally required and observed protein concentrations to support a given metabolic flux. Research reveals systematic variations in efficiency across different metabolic pathway types:

- High-efficiency pathways: Amino acid biosynthesis and cofactor biosynthesis pathways typically operate near optimal efficiency, with protein abundance close to the minimal level required to support observed growth rates [14].

- Low-efficiency pathways: Nutrient uptake systems and central carbon metabolism often show significant over-abundance, with protein levels substantially exceeding theoretically minimal requirements [14].

This efficiency gradient follows the carbon flow through the metabolic network, with efficiency increasing from peripheral nutrient uptake systems to core biosynthetic pathways [14].

Proteome Allocation Modeling Approaches

Table 1: Proteome Allocation Modeling Frameworks

| Model Type | Key Features | Data Requirements | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ME (Metabolism and macromolecular Expression) Models | Explicitly links metabolic reactions with macromolecular synthesis costs; incorporates proteome allocation constraints [15] | Proteomics data, enzyme turnover numbers, metabolic fluxes | Computing growth rate-dependent proteome allocation; predicting metabolic phenotypes |

| ecGEM (enzyme-constrained GEM) | Incorporates enzyme kinetics into genome-scale metabolic models; adds constraints on enzyme capacity [16] | Enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat), enzyme molecular weights, proteomics data | Predicting proteome-limited growth; identifying flux bottlenecks |

| MOMENT (Metabolic Modeling with Enzyme Kinetics) | Uses effective turnover numbers to estimate enzyme amount required for a given flux; constrains total proteome fraction [14] | Effective enzyme turnover numbers (kapp,max, kcat, kapp,ml), proteomics data | Predicting optimal proteome allocation across pathways; pathway efficiency analysis |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Problem: Overprediction of Growth Rates

Issue: FBA models predict significantly higher growth rates than experimentally observed values.

Root Cause: Traditional FBA fails to account for the substantial proteomic resources required for enzyme synthesis and the physical limits of enzyme saturation.

Solutions:

- Implement enzyme capacity constraints: Integrate turnover numbers (kcat values) to calculate the maximum flux supported by a reasonable enzyme concentration [14].

- Add proteome allocation constraints: Limit the total protein mass available for metabolic functions based on experimental measurements [15].

- Use resource balance analysis: Incorporate constraints on the total proteome fraction allocated to enzymes and transporters [14].

Experimental Validation Protocol:

- Step 1: Cultivate E. coli or target organism in chemostat under defined conditions.

- Step 2: Measure growth rate and substrate uptake/secretion rates.

- Step 3: Collect samples for absolute proteomics quantification.

- Step 4: Compare measured growth rates with FBA predictions using proteomic constraints.

- Step 5: Iteratively refine enzyme constraints until predictions align with experimental data.

Problem: Inaccurate Metabolic Flux Predictions

Issue: FBA-predicted intracellular flux distributions contradict 13C-fluxomics validation data.

Root Cause: Models without proteomic constraints can utilize metabolically inefficient pathways that would be proteomically expensive for the cell.

Solutions:

- Adopt hybrid approaches: Implement NEXT-FBA methodology that uses neural networks trained on exometabolomic data to derive biologically relevant constraints for intracellular fluxes [7].

- Integrate multi-omics data: Incorporate proteomic and transcriptomic data to define condition-specific enzyme abundance constraints [16].

- Apply thermodynamic constraints: Incorporate enzyme directionality constraints based on thermodynamic feasibility.

Problem: Model Infeasibility with Experimental Flux Data

Issue: Incorporating measured flux values renders FBA problems infeasible due to violations of steady-state or capacity constraints.

Root Cause: Experimental measurements may contain inconsistencies or conflict with thermodynamic and enzyme capacity constraints.

Solutions:

- Apply flux correction methods: Use linear programming (LP) or quadratic programming (QP) approaches to find minimal corrections to measured fluxes that restore feasibility [17].

- Check network consistency: Verify that the metabolic network can support measured fluxes under enzyme capacity constraints.

- Validate measurement accuracy: Cross-validate flux measurements using multiple techniques (13C-MFA, extracellular flux measurements).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the practical consequences of ignoring proteomic costs in FBA?

Ignoring proteomic costs leads to systematically overoptimistic predictions, including inflated growth rates, incorrect essentiality predictions, and inaccurate flux distributions. This can misguide metabolic engineering efforts and drug target identification. Models that incorporate proteomic constraints show 69% lower error in growth rate predictions and 49% lower error in proteome allocation predictions across diverse conditions [15].

Q2: How can I determine appropriate enzyme turnover numbers for my model?

Effective turnover numbers can be obtained through multiple approaches, with a recommended hierarchy:

- Experimentally measured in vivo turnover numbers (kapp,max): Most reliable, when available from studies using proteomics and fluxomics data [14].

- In vitro kcat values: Useful alternatives when in vivo data is unavailable, though they may not reflect cellular conditions [14].

- Machine learning predictions (kapp,ml): Emerging approach using enzyme structures and biochemical mechanisms as input features when experimental data is lacking [14].

Q3: What is the typical proportion of proteome allocated to metabolic functions?

In E. coli, metabolic enzymes account for more than half of the proteome by mass during exponential growth on minimal media [14]. The exact proportion varies with growth conditions, with slower growth rates generally associated with higher relative investment in metabolic proteins.

Q4: How do I handle inconsistent FBA results when integrating experimental flux data?

When integrating known fluxes causes infeasibility, apply minimal correction approaches using LP or QP formulations [17]. First, identify the conflicting constraints by systematically testing subsets of the measured fluxes. Then, use optimization to find the smallest adjustments to measured values that restore feasibility while maintaining biological relevance.

Q5: Can machine learning approaches help address limitations in proteome-aware FBA?

Yes, hybrid approaches like NEXT-FBA demonstrate that neural networks can effectively relate exometabolomic data to intracellular flux constraints, improving prediction accuracy when comprehensive proteomic data is limited [7]. These methods are particularly valuable for complex eukaryotic systems like CHO cells used in biopharmaceutical production.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Integrating Proteomic Data into Genome-Scale Models

Purpose: To create a proteome-constrained metabolic model for improved phenotype prediction.

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction

- Absolute proteomics data (mg protein/gCDW)

- Enzyme turnover numbers (kcat values)

- Constraint-based modeling software (COBRApy, RAVEN Toolbox)

Procedure:

- Compile enzyme data: For each reaction in the model, identify the corresponding gene and enzyme.

- Convert proteomics to capacity constraints: Calculate maximum flux capacity for each reaction using:

v_max = [E] × k_cat, where [E] is enzyme concentration. - Add enzyme mass balance: Include a constraint limiting the total enzyme mass:

Σ([E_i]/k_cat_i) ≤ P_met, where P_met is the total proteome allocated to metabolism. - Validate with experimental fluxes: Compare model predictions with 13C-fluxomics data and adjust uncertain kcat values within physiological ranges.

- Perform simulations: Use the constrained model for FBA and flux variability analysis.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If the model becomes infeasible, gradually relax the tightest enzyme constraints.

- For reactions without enzyme data, use the median kcat value from the same enzyme class.

- Verify that the total proteome constraint aligns with experimental measurements (typically 50-70% of cell dry weight).

Protocol: Quantitative Proteomics for Model Validation

Purpose: To generate absolute protein quantification data for validating proteome-constrained models.

Materials:

- Cell culture samples at mid-exponential phase

- Protein extraction and digestion reagents

- LC-MS/MS system with label-free quantification capability

- Stable isotope-labeled protein standards

Procedure:

- Sample preparation: Harvest cells, extract proteins, and digest with trypsin.

- Mass spectrometry analysis: Perform LC-MS/MS with data-independent acquisition (DIA).

- Absolute quantification: Use spiked-in heavy isotope-labeled peptide standards for absolute quantification.

- Data processing: Convert peptide intensities to protein concentrations (mmol/gCDW).

- Model integration: Map quantified proteins to metabolic model reactions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Proteome-Aware Metabolic Modeling

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Proteomics Standards | Enable quantification of enzyme concentrations | Stable isotope-labeled peptide standards (SILAC, AQUA) |

| Enzyme Kinetic Parameters | Provide kcat values for flux capacity constraints | BRENDA database, published in vivo kapp,max datasets [14] |

| Genome-Scale Models | Provide metabolic network structure for constraint-based modeling | BiGG Models, ModelSEED, AGORA [18] |

| Proteomics Databases | Source of experimental protein abundance data | ProteomicsDB, PaxDb, species-specific resources |

| Stoichiometric Modeling Software | Implement FBA with additional constraints | COBRA Toolbox, RAVEN Toolbox, CellNetAnalyzer |

Conceptual Diagrams and Workflows

Proteome-Aware FBA Workflow

Proteome-Aware FBA Workflow Integration

Metabolic Pathway Efficiency Gradient

Metabolic Pathway Efficiency Gradient

Advanced Methodologies

NEXT-FBA: A Hybrid Approach

The Neural-net EXtracellular Trained Flux Balance Analysis (NEXT-FBA) methodology addresses proteomic constraint limitations by using artificial neural networks trained on exometabolomic data to predict intracellular flux constraints [7]. This approach:

- Relates extracellular metabolite measurements to intracellular flux states

- Outperforms existing methods in predicting intracellular flux distributions validated by 13C-fluxomics

- Requires minimal input data for pre-trained models

- Is particularly valuable for systems where comprehensive proteomic data is unavailable

Sector-Constrained ME Modeling

For modeling generalist (wild-type) strains that hedge against environmental changes, sector-constrained ME models provide a framework for incorporating proteomic allocation patterns:

- Identify over-allocated sectors: Determine proteome sectors consistently expressed above growth-optimal levels across conditions [15].

- Add sector constraints: Implement coarse-grained constraints on proteome allocation to key functional categories.

- Validate predictions: Test the constrained model against experimental growth rates and metabolic fluxes.

This approach has demonstrated 69% lower error in growth rate predictions and 49% lower error in proteome allocation predictions across 15 growth conditions [15].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My model has high predictive accuracy but fails when the experimental environment changes. What should I do?

- Problem: This is a classic sign of a model that has learned statistical associations from the training data rather than underlying causal mechanisms. It may not generalize to new settings or populations [19].

- Solution:

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Formalize existing biological knowledge using a causal diagram. This helps identify key variables and their relationships, guiding which covariates are necessary for robust predictions [19].

- Use Causal Visualization Tools: Employ tools like Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) to visualize the relationship between predictors and the outcome. The PDP has a mathematical formulation identical to Pearl's back-door adjustment formula, suggesting its potential for causal interpretation when used with a correct causal diagram [19].

- Expand Experimental Conditions: As demonstrated in cross-cell type prediction, performing experiments under varied conditions (e.g., altering extracellular ion concentrations) provides critical information that improves the model's ability to generalize and make accurate predictions in different contexts [20].

FAQ 2: How can I extract meaningful, interpretable insights from a complex "black-box" machine learning model?

- Problem: Complex models like random forests or neural networks are often difficult to interpret, making it hard to understand which variables are important and how they influence the phenotype [19].

- Solution:

- Leverage Interpretability Tools: Move beyond simple coefficient inspection. Utilize visualization tools designed for black-box models [19]:

- Clarify the "Why": Distinguish between different goals. Are you asking about the variable's impact on the prediction, its contribution to predictive accuracy, or its causal effect? These are distinct questions requiring different analytical approaches [19].

FAQ 3: My predictions are quantitatively inaccurate when translating from a model system (e.g., iPSC-CMs) to a target system (e.g., adult human cardiomyocytes). How can I correct for this?

- Problem: Experimental models often exhibit quantitative differences from the human physiology they represent, leading to inaccurate drug response predictions [20].

- Solution: Implement a Cross-Cell Type Regression Model.

- Methodology: This approach combines population-based mechanistic modeling with multivariate statistics [20].

- Generate Heterogeneous Populations: Create large in silico populations of both the experimental model (e.g., iPSC-CM) and the target system (e.g., adult myocyte) by randomizing key model parameters (e.g., maximal ion channel conductances) within physiological ranges [20].

- Simulate Under Multiple Protocols: Simulate physiological metrics (e.g., Action Potential Duration, Calcium Transient Amplitude) for both populations under a range of experimental conditions, including baseline and perturbed states (e.g., different pacing frequencies, altered ion concentrations) [20].

- Build a Regression Model: Use a method like Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) to build a model that predicts the physiological outputs of the target system based on the outputs from the experimental model [20].

- Key Insight: The most informative experimental conditions for building this model are often those that cause significant shifts in the population distributions of the physiological metrics, such as altering extracellular Ca²⁺ or Na⁺ concentrations [20].

- Methodology: This approach combines population-based mechanistic modeling with multivariate statistics [20].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Building a Cross-Cell Type Prediction Model [20]

| Step | Description | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Model Selection | Select mathematical models for the source (e.g., iPSC-CM) and target (e.g., adult myocyte) cell types. | Models should be mechanistic (e.g., based on ordinary differential equations) and describe the same core physiology. |

| 2. Generate Populations | Create populations of models reflecting natural variability. | Randomize maximal conductance values for 13 ion transport pathways to generate 600 in silico cells of each type. |

| 3. Define Protocols | Simulate each model under multiple experimental conditions. | Conditions include spontaneous beating, 2 Hz pacing, and alterations to extracellular [Ca²⁺] and [Na⁺]. |

| 4. Feature Extraction | Calculate quantitative features from simulation outputs. | Extract Action Potential Duration at 90% repolarization (APD90), Calcium Transient Amplitude (CaTA), diastolic voltage, etc. |

| 5. Regression Analysis | Build a predictive model using PLSR. | Use features from the source cell population to predict features in the target cell population. Validate with 5-fold cross-validation. |

Protocol 2: Predicting Phenotypes from a Curated Genetic Network using Boolean Modeling [21]

| Step | Description | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Network Curation | Construct a network from literature evidence. | The yeast sporulation network included 29 nodes representing genes/proteins and two marker nodes (EMG, MMG). |

| 2. Boolean Formulation | Define the state (ON=1, OFF=0) and update logic for each node. | Use a Markov chain for state updates. For AND nodes, output is 1 only if all inputs are 1. |

| 3. Simulate Perturbations | Clamp a gene node to 0 to simulate a gene deletion. | Enumerate all possible initializations of the network with and without the perturbation. |

| 4. Calculate Phenotype | Define a product function to quantify the phenotype. | Sporulation is complete only if both EMG and MMG marker nodes are in state "1". Sporulation percentage is the fraction of initializations leading to this outcome. |

| 5. Compute Efficiency Change | Compare sporulation before and after perturbation. | The ratio of sporulation percentages (unperturbed/perturbed) is the predicted quantitative phenotype change (α). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key resources for conducting research in quantitative phenotype prediction.

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| UMMI (Ubiquitous Model selector for Motif Interactions) | A computational method to reconstruct transcriptional regulatory networks from genomic data, which can be hybridized with curated networks [21]. |

| Design Space Toolbox (DST3) | A software toolbox that automates the analysis of biochemical systems, enabling the mapping of kinetic parameters to biochemical phenotypes within the Phenotype Design Space framework [22]. |

| Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) | A multivariate statistical technique used to build predictive models when predictor variables are highly collinear, as in the cross-cell type prediction model [20]. |

| Boolean Network Model | A discrete dynamic modeling framework used to simulate the steady-state behavior of genetic networks and predict the phenotypic impact of perturbations, such as gene deletions [21]. |

| Causal Diagram (DAG) | A graphical representation of assumed causal relationships between variables, providing a formal framework for causal inference and guiding model adjustment [19]. |

| Partial Dependence Plot (PDP) | A model-agnostic visualization tool for interpreting black-box models by showing the marginal effect of a feature on the predicted outcome [19]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

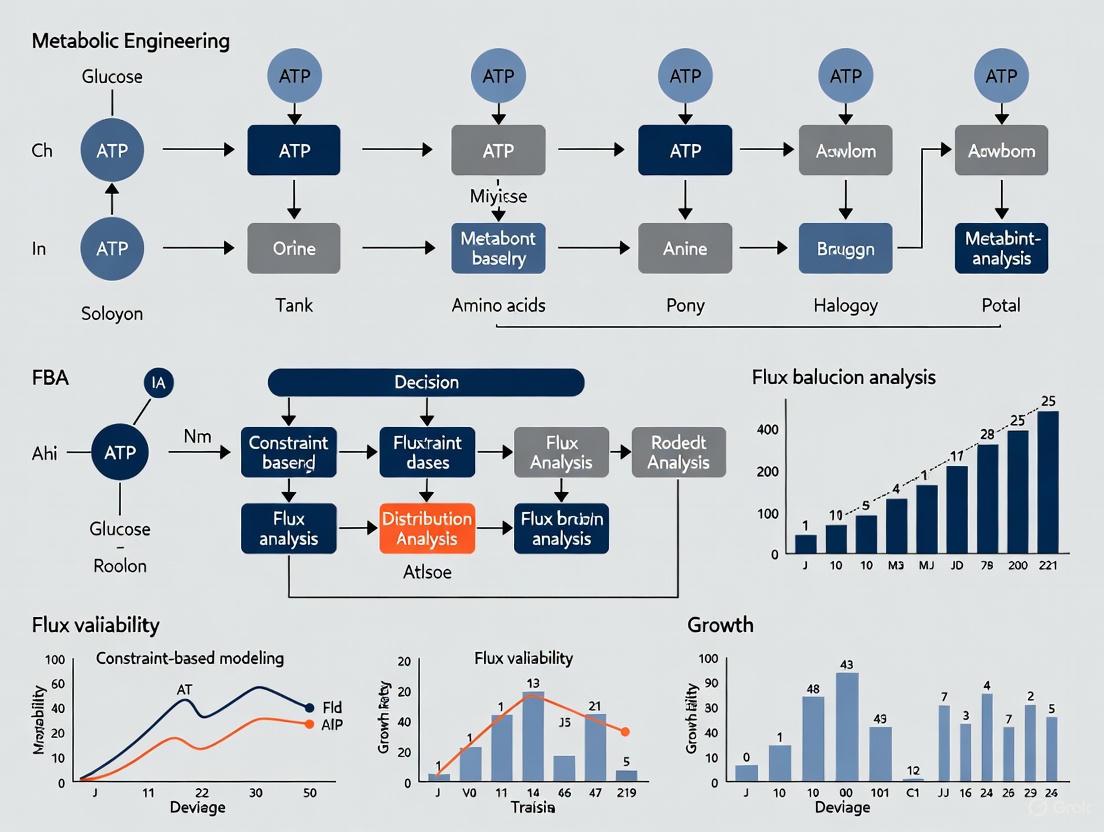

Next-Generation Frameworks: From Hybrid Models to Machine Learning

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of embedding FBA within a neural network architecture compared to using FBA alone? The primary advantage is a significant improvement in quantitative predictive power for phenotypes like growth rate. Classical FBA requires labor-intensive measurements of uptake fluxes for accurate predictions. A neural-mechanistic hybrid model uses a trainable neural layer to predict these inputs, learning the relationship between environmental conditions (e.g., medium composition) and the resulting metabolic phenotype. This approach fulfills mechanistic constraints while leveraging machine learning, saving time and resources [23].

Q2: My hybrid model fails to converge during training. What could be the issue? Non-convergence often stems from the choice of the surrogate solver and its interaction with gradient-based learning. The Simplex solver used in classic FBA is not amenable to backpropagation. Ensure you are using a differentiable alternative, such as the QP-solver described in the literature, which solves a quadratic program to find a feasible, optimal flux distribution and allows for gradient computation [23].

Q3: How can I model dynamic metabolic switches, like a microbe switching between carbon sources, with a hybrid FBA-ML approach? A highly effective method is to create a surrogate FBA model using Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). You can train ANNs on a large set of pre-computed FBA solutions for various environmental conditions. This ANN, represented as algebraic equations, can then be integrated into dynamic models (e.g., reactive transport models) to simulate metabolic switching. This approach reduces computational time by orders of magnitude and improves numerical stability compared to repeatedly solving LP problems within dynamic simulations [24].

Q4: What data do I need to train a hybrid model for predicting the effect of gene knock-outs?

The training data should consist of reference flux distributions for different gene knock-out conditions. The hybrid model, particularly its neural preprocessing layer, learns to predict the initial flux state (V0) from the input condition (e.g., the knocked-out gene). This allows the model to generalize and predict the metabolic phenotype for knock-outs not in the training set, capturing the effect of metabolic enzyme regulation [23].

Q5: Can I integrate transcriptomic data with a hybrid FBA-ML model? Yes. Protocols exist for integrating multi-omic data like transcriptomics into regularized FBA. Machine learning algorithms such as PCA and LASSO regression can then be used on the combined transcriptomic and fluxomic (FBA output) datasets to reduce dimensionality and identify key cross-omic features that explain metabolic activity across different conditions [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Prediction of Metabolic Byproducts

- Symptoms: The model predicts zero or abnormally low secretion of byproducts (e.g., acetate, pyruvate) that are experimentally observed.

- Possible Causes:

- The standard FBA assumption of a single biomass-maximizing objective is insufficient.

- The mechanistic constraints in the hybrid model do not capture the organism's regulatory mechanisms.

- Solutions:

- Implement a multi-step Linear Programming (LP) formulation. First, optimize for biomass. Then, fix biomass production at a fraction of its maximum and introduce a secondary objective to minimize the sum of fluxes (for parsimony) or maximize the production of the specific byproduct [24].

- Incorporate enzyme constraints into the underlying Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM). Tools like ECMpy can add constraints based on enzyme kinetics (Kcat values) and abundance, which more realistically cap flux through pathways and can force the model to secrete byproducts [26].

Problem: Poor Generalization to New Environmental Conditions

- Symptoms: The model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen medium conditions or nutrient concentrations.

- Possible Causes:

- The training set is too small or lacks diversity.

- The neural network architecture is overfitting.

- Solutions:

- Generate a large and diverse set of training data. Use the base FBA model to simulate a wide range of possible environmental conditions by randomly sampling upper and lower bounds for uptake reactions. This ensures the ANN surrogate model learns a comprehensive map of the metabolic solution space [24].

- Perform a grid search for optimal hyperparameters (number of layers, nodes) and use regularization techniques during ANN training. Literature shows that both Multi-Input Single-Output (MISO) and Multi-Input Multi-Output (MIMO) architectures can achieve high correlation (>0.9999) with FBA solutions when properly tuned [24].

Problem: Numerical Instability in Dynamic Simulations

- Symptoms: Simulations coupling metabolism with dynamics (e.g., in a batch reactor) crash or produce non-physical results like negative concentrations.

- Possible Causes:

- Directly and repeatedly calling an LP solver within a dynamic simulation can lead to instability.

- The FBA solution jumps discontinuously between time points.

- Solutions:

- Replace the LP solver with an ANN-based surrogate model. Since ANNs are algebraic equations, they can be seamlessly incorporated into differential equation solvers used in dynamic models, eliminating the need for iterative LP calls and ensuring smooth, stable solutions [24].

- Use a cybernetic modeling approach alongside the surrogate FBA model. This approach dynamically allocates resources based on the perceived "profitability" of different metabolic pathways, enabling smooth switching between substrates like lactate, pyruvate, and acetate [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Basic Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic Model

This protocol outlines the steps to create a hybrid model that improves quantitative growth prediction from medium composition.

- Objective: Train a hybrid model to predict E. coli growth rates in different media.

- Materials:

- Methodology:

- Generate Training Data:

- Use Cobrapy to run FBA simulations across a wide range of uptake flux bounds (

Vin) that represent different environmental conditions. - For each condition, record the input

Vinand the output growth rate (biomass flux) and other relevant fluxes (Vout). This forms your reference dataset [23].

- Use Cobrapy to run FBA simulations across a wide range of uptake flux bounds (

- Design Model Architecture:

- Neural Layer: A feedforward network that takes medium composition (

Cmed) or flux bounds (Vin) as input and outputs an initial flux vectorV0. - Mechanistic Layer: A differentiable solver (e.g., QP-solver) that takes

V0and computes a steady-state flux distributionVoutthat satisfies the GEM's stoichiometric and bound constraints [23].

- Neural Layer: A feedforward network that takes medium composition (

- Train the Model:

- Use a loss function that combines the error between predicted (

Vout) and reference fluxes, and a term that penalizes violations of the mechanistic constraints. - Use backpropagation through the differentiable solver to train the neural layer.

- Use a loss function that combines the error between predicted (

- Generate Training Data:

Protocol 2: Creating an ANN Surrogate for Dynamic FBA

This protocol describes how to replace an FBA model with an ANN for rapid, stable dynamic simulation.

- Objective: Simulate the metabolic switching of Shewanella oneidensis in a batch reactor.

- Materials:

- A GEM for S. oneidensis (e.g., iMR799 with modifications [24]).

- Software for FBA and ANN training.

- Methodology:

- Characterize the FBA Solution Space:

- For each carbon source (lactate, pyruvate, acetate), run multi-step FBA across a 2D grid of possible carbon and oxygen uptake rates.

- Record the exchange fluxes for substrate uptake, biomass production, and byproduct secretion [24].

- Train the Surrogate ANN:

- Assemble the dataset with inputs (uptake bounds for carbon and oxygen) and outputs (all key exchange fluxes).

- Train a Multi-Input Multi-Output (MIMO) ANN to predict all output fluxes simultaneously. Perform a grid search to find the optimal number of layers and nodes [24].

- Integrate into Dynamic Model:

- Incorporate the trained ANN as algebraic equations into the mass balance Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) of the batch reactor model.

- The ANN now acts as the source/sink terms for metabolites, replacing the need to call FBA at every time step [24].

- Characterize the FBA Solution Space:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Key computational tools and resources for developing hybrid FBA-ML models.

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | Provides the mechanistic core; defines stoichiometric constraints, reaction network, and gene-protein-reaction relationships. | iML1515 for E. coli [23] [26], iMR799 for S. oneidensis [24]. |

| FBA Software Package | Solves the linear programming problem to generate training data and validate model predictions. | Cobrapy [23] [26], COBRA Toolbox. |

| Enzyme Constraint Data (Kcat, Abundance) | Adds a layer of realism to FBA, capping flux by enzyme capacity, which can improve byproduct prediction. | BRENDA (Kcat values) [26], PAXdb (protein abundance) [26]. |

| Machine Learning Framework | Provides the environment to build, train, and validate the neural network component of the hybrid model. | Python with PyTorch, TensorFlow, or SciML.ai ecosystem [23]. |

| Differentiable Solver (QP-solver) | A critical component that replaces the non-differentiable Simplex solver, enabling gradient backpropagation for training. | Custom implementation as described in [23]. |

Workflow and Architecture Diagrams

Diagram 1: High-level architecture of a neural-mechanistic hybrid model showing the flow of information and the training loop via backpropagation.

Diagram 2: Workflow for creating and deploying an ANN surrogate model to replace FBA in dynamic simulations like Reactive Transport Modeling (RTM).

Core FCL Concepts & FAQs

FAQ 1: What is Flux Cone Learning and how does it differ from Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)?

Flux Cone Learning (FCL) is a general computational framework that uses Monte Carlo sampling and supervised learning to predict the effects of metabolic gene deletions on cellular phenotypes. Unlike FBA, which relies on an optimality principle (like maximizing biomass) to predict metabolic fluxes, FCL identifies correlations between the geometry of the metabolic space and experimental fitness scores from deletion screens. This approach does not require an assumption of cellular optimality, which makes it more versatile, especially for higher-order organisms where the optimality objective is unknown. FCL has demonstrated best-in-class accuracy for predicting metabolic gene essentiality, outperforming the gold standard FBA predictions in organisms like Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Chinese Hamster Ovary cells [27].

FAQ 2: On what principle does the Monte Carlo sampling in FCL operate?

The Monte Carlo method in FCL relies on repeated random sampling to explore the metabolic flux space defined by a Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM). The core principle involves [27] [28]:

- Defining the Domain: The domain is the metabolic flux cone, defined by the stoichiometric matrix S of the GEM and the flux constraints ( Sv = 0, Vi^min ≤ vi ≤ V_i^max ).

- Generating Random Inputs: A Monte Carlo sampler generates numerous random, thermodynamically feasible flux distributions (samples) within this high-dimensional polytope.

- Deterministic Computation: For each gene deletion, the associated reaction fluxes are constrained (often set to zero via the GPR rules), which alters the shape of the flux cone. The sampler then generates a specific set of flux samples for this perturbed cone.

- Aggregating Results: These flux samples form a large corpus of training data that captures the geometric changes in the metabolic space resulting from each gene deletion [27].

FAQ 3: My FCL model performance is poor. What are the primary factors that influence its accuracy?

The predictive accuracy of FCL is dependent on several key factors [27]:

- Quality of the GEM: A well-curated and complete Genome-scale Metabolic Model is crucial. Performance can drop significantly with less complete models.

- Number of Monte Carlo Samples: Using too few samples per deletion cone can reduce accuracy. However, models trained with as few as 10 samples per cone have been shown to match state-of-the-art FBA accuracy.

- Quantity of Training Data: The number of gene deletions with associated experimental fitness data for training directly impacts the model's performance. A smaller training set can lead to lower accuracy.

- Dimensionality of Features: Reducing the feature space (e.g., using Principal Component Analysis) has been shown to lower accuracy. The correlations between essentiality and subtle changes in the flux cone's shape are best captured in the high-dimensional reaction space.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Counterintuitive Gene Essentiality Predictions

- Potential Cause: Errors or omissions in the Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM), such as incorrect Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules or missing alternative pathways, can lead to flawed sampling and incorrect predictions [27].

- Solution:

- Action: Manually curate and verify the GPR rules for the genes giving unexpected results. Check for known gaps in the metabolic network for your organism.

- Action: Ensure that the biomass objective function is removed from the training data to prevent the model from simply learning the FBA-based correlation between biomass and essentiality [27].

- Action: Consult the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values or feature importance scores from your trained model. In E. coli, top predictor reactions are often enriched for transport and exchange reactions; inspecting these can provide biological insight into the model's decision-making [27].

Issue 2: Computational Cost and Handling Large Datasets is Prohibitive

- Potential Cause: The FCL framework can generate extremely large datasets. For example, sampling 1,502 gene deletions in E. coli with 100 samples per cone and 2,712 reactions results in a dataset over 3GB in size, making computations slow and resource-intensive [27] [28].

- Solution:

- Action: Start with a lower number of samples per cone (e.g., 10-50). Empirical data shows this can still achieve high accuracy while drastically reducing computational load [27].

- Action: Leverage parallel computing strategies. The Monte Carlo sampling process is "embarrassingly parallel," meaning you can distribute the sampling of different deletion cones across multiple local processors, clusters, or cloud computing instances [28].

- Action: Consider using a simpler supervised learning model, such as a Random Forest, which provides an excellent compromise between performance and interpretability without the extreme computational demands of overparameterized deep learning models [27].

Issue 3: Model Fails to Generalize to New Environmental Conditions

- Potential Cause: The model was trained on fitness data from a specific environment (e.g., a single carbon source) and has learned condition-specific patterns that do not transfer.

- Solution:

- Action: Incorporate training data from a diverse set of environmental conditions. This helps the model learn a more robust relationship between flux cone geometry and fitness.

- Action: When building the sampling input, ensure the flux bounds (Eq. 2) accurately reflect the new environmental condition to be tested (e.g., different carbon source uptake rates) [27].

Standard Experimental Protocol for Gene Essentiality Prediction

This protocol outlines the key steps for building an FCL-based predictor for metabolic gene essentiality.

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Input: A high-quality Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM) for your target organism in a standard format (e.g., SBML).

- Input: A dataset of experimental fitness scores (e.g., from CRISPR screens) for a set of gene deletions, classified as essential or non-essential under a defined condition.

- Action: Split the gene deletion data into training and test sets (a typical split is 80/20).

Step 2: Monte Carlo Sampling of Flux Cones

- Action: For the wild-type and each gene deletion in the training set, use a Monte Carlo sampler (e.g., the

samplemethod in the COBRApy toolbox) to generate flux distributions.- Parameter: Set the number of samples per cone (

q). A value of 100 is a robust starting point [27]. - Parameter: For a deletion, use the GPR rules to constrain the fluxes of associated reactions to zero.

- Parameter: Set the number of samples per cone (

- Output: A feature matrix of size (k × q, n), where k is the number of deletions, q is samples per cone, and n is the number of reactions in the GEM.

Step 3: Model Training with Supervised Learning

- Action: Assign the experimental fitness label (e.g., essential=1, non-essential=0) to all flux samples originating from the same gene deletion.

- Action: Train a supervised learning model. A Random Forest classifier is highly recommended.

- Justification: It offers a good balance of performance and interpretability and has been shown to work effectively with FCL data without requiring excessive hyperparameter tuning [27].

- Output: A trained classification model.

Step 4: Prediction and Aggregation

- Action: For a new gene deletion (from the test set), generate

qflux samples for its perturbed cone. - Action: Use the trained model to get a prediction (essential or non-essential) for each of the

qindividual flux samples. - Action: Aggregate the sample-wise predictions using a majority voting scheme to produce a single, final prediction for the gene deletion [27].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Performance Data & Benchmarking

Table 1: FCL vs. FBA Performance in E. coli (Glucose, Aerobic) [27]

| Metric | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Flux Cone Learning (FCL) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 93.5% | 95.0% |

| Precision | Not Reported | Higher than FBA |

| Recall | Not Reported | Higher than FBA |

| Non-Essential Gene Prediction | Baseline | +1% Improvement |

| Essential Gene Prediction | Baseline | +6% Improvement |

Table 2: Impact of Key Parameters on FCL Model Accuracy [27]

| Parameter | Tested Condition | Impact on Predictive Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Samples per Cone (q) | q = 10 | Matches FBA accuracy |

| q = 100 | Achieves peak performance (95%) | |

| GEM Quality | Latest GEM (iML1515) | Best performance (95%) |

| Earlier, smaller GEM (iJR904) | Statistically significant drop | |

| Feature Space | Full Reaction Space (n=2712) | Best performance |

| Reduced Space (PCA) | Lower accuracy in all tests |

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for FCL Implementation

| Item | Function in FCL | Notes & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | Defines the stoichiometric constraints and gene-reaction relationships that form the flux cone for sampling. | Must be organism-specific. Examples: iML1515 for E. coli. Quality is critical [27]. |

| Monte Carlo Sampler | Generates random, thermodynamically feasible flux distributions from the wild-type and mutant flux cones. | Implementations available in COBRApy (Python) or the COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB). |

| Experimental Fitness Data | Provides the phenotypic labels (e.g., essential/non-essential) for training the supervised learning model. | Data from CRISPR-Cas9 or RNAi deletion screens. Used for supervised training [27]. |

| Supervised Learning Algorithm | Learns the correlation between the geometric features of the sampled flux cones and the phenotypic outcome. | Random Forest is recommended. Deep learning models did not show improved performance in initial tests [27]. |

The logical relationships and decision points for troubleshooting within the FCL framework are illustrated below:

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a fundamental constraint-based method for predicting metabolic behavior in silico by optimizing an objective function, typically biomass maximization [29]. However, a significant limitation arises because cells dynamically adjust their metabolic priorities in response to environmental changes, and traditional FBA with a single, static objective function often fails to capture these adaptive flux variations [6] [9]. This limitation obstructs accurate quantitative phenotype predictions, particularly in complex or changing environments.

The TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) framework addresses this core challenge by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer context-specific metabolic objectives from experimental data [6] [9]. The framework introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which quantify each metabolic reaction's contribution to a weighted objective function, thereby aligning model predictions with experimental flux observations [30]. By focusing on the network topology and pathway structure, TIObjFind enhances the interpretability of complex metabolic networks and provides insights into adaptive cellular responses.

Technical Deep Dive: How TIObjFind Works

The TIObjFind framework operates through a structured, three-step computational pipeline.

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the TIObjFind framework, from problem formulation to result interpretation:

Core Computational Components

Step 1: Optimization Problem Formulation TIObjFind reformulates the objective function selection as an optimization problem. It seeks to minimize the difference between predicted fluxes ((v)) and experimental flux data ((v^{exp})) while simultaneously maximizing an inferred metabolic goal represented as a weighted sum of fluxes ((c^{obj} \cdot v)) [6] [9]. This can be viewed as a scalarization of a multi-objective problem.

Step 2: Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Construction The optimized flux distribution is mapped onto a Mass Flow Graph, a directed, weighted graph where nodes represent metabolic reactions and edges represent metabolite flow between them [6]. This graphical representation provides a topology-informed context for analyzing flux distributions.

Step 3: Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) and Minimum Cut The framework applies a path-finding algorithm to the MFG to analyze the Coefficients of Importance between designated start reactions (e.g., glucose uptake) and target reactions (e.g., product secretion) [6] [9]. The Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm is used to solve the minimum-cut problem, efficiently identifying the most critical pathways and connections for the desired metabolic conversion [9]. The "minimum cut" in this graph theoretically identifies the set of reactions with the smallest total capacity that, if removed, would disrupt the flow from start to target, thereby highlighting the most critical pathways.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of the TIObjFind framework requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table summarizes the key components.

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples & Functions | Role in TIObjFind Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | MATLAB (primary implementation), Python (visualization) [9] | Core algorithm development, optimization solving, and data analysis. |

| Key Algorithms & Packages | MATLAB's maxflow package, Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm [9] |

Solving the minimum-cut problem in the Mass Flow Graph. |

| Visualization Tools | Python pySankey package [9] |

Creating interpretable diagrams of flux distributions and pathways. |

| Biochemical Databases | KEGG, EcoCyc, ModelSEED Biochemistry [6] [18] | Providing curated metabolic networks, reactions, and compounds for model reconstruction. |

| Metabolic Modeling Platforms | KBase, ModelSEED [18] | Reconstructing and gap-filling draft genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My TIObjFind model fails to align with experimental data, even after optimization. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause 1: Incomplete Metabolic Network. Draft metabolic models often lack essential reactions, especially transporters.

- Solution: Use a gap-filling algorithm, like the one in KBase, which uses linear programming (LP) to find a minimal set of reactions to add, enabling your model to produce biomass on a specified medium [18].

- Potential Cause 2: Inaccurate Experimental Flux Data. The framework relies on high-quality (v^{exp}).

Q2: Why does TIObjFind use a minimum-cut algorithm instead of just enumerating all pathways?

- Answer: Full enumeration of all Elementary Flux Modes (EFMs) becomes computationally infeasible as network size increases [29]. The minimum-cut algorithm, applied to the Mass Flow Graph, efficiently identifies the most critical pathways connecting a source (e.g., nutrient uptake) to a sink (e.g., product formation) without enumerating all possibilities, significantly improving scalability and interpretability [6] [9].

Q3: How do I choose the start and target reactions for the pathway analysis in TIObjFind?

- Guidance: The selection should be biologically driven.

- Start Reaction: Typically represents a key metabolic input, such as glucose uptake (e.g., reaction

r1in a toy model) [9]. - Target Reaction: Represents the metabolic output of interest, such as the secretion of a target metabolite (e.g., reaction

r6orr7) or biomass formation [9]. The framework allows you to assess different metabolic objectives by varying these targets.

- Start Reaction: Typically represents a key metabolic input, such as glucose uptake (e.g., reaction

Q4: What is the difference between TIObjFind and its predecessor, ObjFind?

- Key Advancement: The ObjFind framework assigned Coefficients of Importance across all reactions, which could lead to overfitting for specific conditions and offered limited interpretability [6]. TIObjFind incorporates network topology by using MPA and the Mass Flow Graph. This focuses the analysis on specific, critical pathways, which enhances biological interpretability and reduces the risk of overfitting [6] [9].

Experimental Protocol: Application to a Clostridium acetobutylicum Case Study

The following diagram outlines the specific experimental and computational workflow as applied in one of the key case studies validating TIObjFind:

Detailed Methodology:

Biological System and Cultivation: The case study focuses on Clostridium acetobutylicum undergoing fermentation of glucose [6]. Cultivate the organism under controlled bioreactor conditions to obtain data across different metabolic phases (e.g., acidogenic and solventogenic stages).

Data Collection - Experimental Fluxes ((v^{exp})): Collect time-series data on extracellular metabolite concentrations. Calculate uptake (e.g., glucose) and secretion (e.g., acetate, butyrate, acetone, butanol) rates to establish a set of experimental fluxes for key exchange reactions [6].

Model Preparation: Utilize a pre-existing, well-curated genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for Clostridium acetobutylicum, such as the iCAC802 model referenced in the study [6]. Ensure the model's stoichiometric matrix (

N) and flux bounds are correctly defined.TIObjFind Execution: Implement the three-step TIObjFind workflow using MATLAB.

- Run the optimization to find the Coefficients of Importance (

c) that best align FBA predictions with the measured (v^{exp}). - Construct the Mass Flow Graph using the optimized flux distribution,

v*. - Apply the minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., via

maxflowin MATLAB) between glucose uptake and secretion reactions for products like butanol to identify the critical pathway [9].

- Run the optimization to find the Coefficients of Importance (

Analysis and Validation: Analyze the resulting Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) to interpret the organism's stage-specific metabolic objectives. A successful application will demonstrate a significant reduction in prediction error and a strong alignment between the model's flux distribution and the independent experimental data [6].

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are comprehensive representations of metabolic genes and reactions widely used to evaluate genetic engineering of biological systems. However, these models often fail to accurately predict the behavior of genetically engineered cells, primarily due to incomplete annotations of gene interactions [31] [32]. This limitation presents significant challenges for researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development who rely on accurate phenotype predictions.

Boolean Matrix Logic Programming (BMLP) represents a novel approach that addresses these limitations by leveraging logic-based machine learning to guide biological discovery through cost-effective experimentation [31] [33]. The BMLP_active system implements this approach, using interpretable logic programs to encode state-of-the-art GEMs and actively select informative experiments, dramatically reducing the experimental burden required to elucidate gene functions [34].

This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers implementing BMLP approaches to overcome persistent challenges in quantitative phenotype predictions, particularly those generated through Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) frameworks [35].

## Core Concepts: Boolean Matrix Logic Programming

### What is Boolean Matrix Logic Programming (BMLP)?

Boolean Matrix Logic Programming (BMLP) is a novel framework that uses Boolean matrices to efficiently evaluate large logic programs, enabling reasoning about hypotheses and updating knowledge through empirical observations [31] [34]. By leveraging Boolean matrices to encode relationships between genes and metabolic reactions, BMLP accelerates logical inference for complex biological systems.

Key Technical Components:

- Datalog Representation: Encodes metabolic networks as Datalog programs, a declarative logic programming language ideal for expressing relationships in biological networks [36]

- Boolean Matrix Operations: Represents biochemical relationships in matrix form where entries denote interaction states (1 for presence, 0 for absence)

- Transitive Closure Computation: Determines reachability of metabolic states through efficient Boolean matrix multiplication [36]

- Active Learning Integration: Strategically selects experiments to minimize resource consumption while maximizing information gain [34]

### How does BMLP_active improve upon traditional gene function prediction methods?

Traditional computational gene function prediction methods often rely on statistical associations between genetic and phenotypic variation, creating a "black box" that doesn't reveal the actual processes causing phenotypes [35]. These approaches typically depend heavily on sequence similarity transfer and struggle with the biases in Gene Ontology annotations [37] [38].

BMLP_active addresses these limitations through:

- Interpretable Logic Programs: Represents biological knowledge in human-readable form rather than "black box" statistical models [31]

- Active Experiment Selection: Guides cost-effective experimentation by selecting maximally informative experiments [33]

- Handling of Genetic Interactions: Specifically designed to learn digenic interactions and complex genetic relationships [33]

- Computational Efficiency: Achieves 170-fold speedup in runtime for predicting phenotypic effects compared to standard SWI-Prolog without BMLP [34]

Table 1: Performance Comparison of BMLP_active vs. Traditional Methods

| Metric | BMLP_active | Traditional Methods | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental cost for learning gene functions | Substantially reduced | High | 90% reduction in optional nutrient substance cost [34] |

| Training examples needed for gene interactions | Minimal | Extensive | Fewer than random experimentation [31] |

| Runtime efficiency | High | Variable | 170x faster than SWI-Prolog without BMLP [34] |

| Interpretability of results | High (logic programs) | Low (black box) | Explainable hypotheses [31] |

## Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

### How do I resolve inconsistencies between BMLP predictions and experimental growth measurements?

Inconsistencies between predictions and experimental observations often stem from incorrect gene-reaction rules in your metabolic model. Follow this systematic troubleshooting protocol:

Step 1: Verify Gene-Reaction Rule Encoding

- Check Boolean logic rules for enzyme complexes and isozymes in your model

- Confirm that gene-protein-reaction associations properly represent isozymic relationships [35]

- Validate that Boolean matrix operations correctly capture transitive relationships in metabolic pathways

Step 2: Examine Environmental Constraints

- Verify nutrient availability settings in your growth medium configuration

- Check for missing transport reactions in your model

- Confirm thermodynamic constraints align with experimental conditions

Step 3: Investigate Genetic Interactions

- Test for unaccounted digenic interactions using BMLP_active's active learning capabilities

- Examine potential epistatic effects in double knockout simulations

- Use the hypothesis pruning feature to identify conflicting genetic relationships [36]

Debugging Workflow:

### What should I do when BMLP_active fails to converge on gene-isoenzyme mappings?

Failure to converge on correct gene-isoenzyme mappings typically indicates issues with experimental design or hypothesis space formulation.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Insufficient Experimental Diversity

- Symptom: Active learning cycles repeatedly select similar experiments

- Solution: Expand the pool of candidate experiments to include more genetic variants and environmental conditions

- Implementation: Modify cost function to encourage exploration of under-sampled areas of hypothesis space [34]

Overly Restricted Hypothesis Space

- Symptom: Consistent elimination of all hypotheses during pruning phases

- Solution: Review background knowledge constraints and expand allowable gene-function relationships

- Implementation: Check for overly strict logical constraints in your Datalog program [36]

Noisy Experimental Data

- Symptom: Inconsistent experimental outcomes leading to contradictory hypothesis elimination

- Solution: Implement replicate experiments and statistical validation of growth phenotypes

- Implementation: Use BMLP_active's cost function to weight experiments by reliability [34]

Table 2: Troubleshooting BMLP_active Convergence Issues

| Symptoms | Likely Causes | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Repeated selection of similar experiments | Limited candidate experiment diversity | Expand genetic variants and environmental conditions in candidate pool |

| All hypotheses eliminated during pruning | Overly restricted hypothesis space | Review and relax logical constraints in background knowledge |

| Inconsistent hypothesis scoring | Noisy experimental data | Increase experimental replicates; implement statistical validation |

| Slow convergence on digenic interactions | Insufficient training examples | Use active learning to select maximally informative gene pairs [33] |

### How can I optimize computational performance for large-scale GEMs like iML1515?

Working with genome-scale models such as iML1515 (containing 1515 genes and 2719 metabolic reactions) requires careful attention to computational efficiency [34].

Performance Optimization Strategies:

Boolean Matrix Implementation

- Utilize sparse matrix representations for memory efficiency

- Implement optimized Boolean matrix multiplication algorithms

- Leverite parallel processing for transitive closure computations [34]

Active Learning Scaling

- Use hierarchical hypothesis generation to reduce search space

- Implement approximate reasoning for preliminary hypothesis scoring

- Employ strategic sampling of hypothesis space before full evaluation

Memory Management

- Segment large GEMs into functional modules where possible

- Implement disk-based caching for intermediate results

- Use incremental reasoning to avoid recomputing unchanged portions of the model

## Experimental Protocols & Methodologies