Beyond the Active Site: Innovative Strategies to Enhance Rate-Limiting Enzyme Catalytic Efficiency

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies for enhancing the catalytic efficiency of rate-limiting enzymes, a critical focus for researchers and drug development professionals.

Beyond the Active Site: Innovative Strategies to Enhance Rate-Limiting Enzyme Catalytic Efficiency

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies for enhancing the catalytic efficiency of rate-limiting enzymes, a critical focus for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores foundational principles of enzyme dynamics, including the emerging role of distal mutations in facilitating substrate binding and product release. The scope extends to advanced methodologies such as directed evolution, combinatorial pathway optimization, and catalytic residue reprogramming, alongside troubleshooting for common challenges like pH stability and organic solvent tolerance. A comparative analysis of these techniques offers a practical framework for selecting and validating optimization strategies in biomedical research and industrial biocatalysis.

The Catalytic Blueprint: Unraveling the Principles of Enzyme Efficiency and Rate-Limiting Steps

Core Concept Definitions

Catalytic Efficiency describes the effectiveness of an enzyme in converting substrate to product. Optimizing this is crucial in research focused on overcoming metabolic bottlenecks caused by rate-limiting enzymes, a key objective in drug development and metabolic engineering [1] [2].

Turnover Number (

k_cat): The maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [3] [4] [5]. It defines the catalytic cycle's maximum speed.Michaelis Constant (

K_M): The substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half ofV_max[2]. It approximates the enzyme's affinity for its substrate, where a lowerK_Mindicates higher affinity.- Formula:

K_M = (k_(-1) + k_2) / k_1, wherek_1is the rate constant for enzyme-substrate association, andk_(-1)andk_2are the rate constants for dissociation and product formation, respectively [2].

- Formula:

Specificity Constant (

k_cat / K_M): Also referred to as catalytic efficiency, this ratio is a second-order rate constant that measures an enzyme's effectiveness at low substrate concentrations [1] [6] [7]. It sets the upper limit for how efficiently an enzyme can encounter and convert a substrate molecule into product.

Key Metric Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these core kinetic parameters and the ultimate goal of catalytic efficiency.

The table below summarizes the ranges and benchmarks for these key metrics, providing a reference for evaluating enzyme performance.

| Metric | Definition | Ideal Value / Benchmark | Significance in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

Turnover Number (k_cat) |

Max catalytic cycles per second per active site [5]. | Varies by enzyme (e.g., Carbonic anhydrase: 10⁴ - 10⁶ s⁻¹; Acetylcholinesterase: >10⁴ s⁻¹) [3]. | A high k_cat is desirable for rapid metabolite conversion or prodrug activation [5]. |

Michaelis Constant (K_M) |

Substrate concentration at half V_max [2]. |

Lower values indicate higher substrate affinity. | Informs on target engagement; low K_M can mean efficacy at low substrate concentrations. |

k_cat / K_M (Catalytic Efficiency) |

Bimolecular rate constant of catalytic prowess [6]. | Diffusion limit: ~10⁸ – 10⁹ M⁻¹s⁻¹ (e.g., Triose phosphate isomerase) [6]. | Identifies enzymes operating at peak efficiency. Key for evaluating competing substrate specificity [6] [7]. |

| Industrial Turnover Frequency (TOF) | Turnovers per unit time in non-enzymatic catalysis [3]. | Typical range: 10⁻² – 10² s⁻¹ [3]. | Critical for assessing the cost-effectiveness and lifetime of catalytic therapeutic agents. |

Experimental Protocol: Determiningk_catandK_M

This section provides a detailed methodology for determining kinetic parameters using steady-state kinetics, forming the basis for troubleshooting and optimization.

The diagram below outlines the key stages of a standard experimental workflow for measuring enzyme kinetics.

Detailed Methodology

Objective: To determine the Michaelis constant (K_M), maximum velocity (V_max), and turnover number (k_cat) of an enzyme.

1. Reaction Preparation

- Maintain a constant, known concentration of enzyme (

[E_total]) throughout the experiment. - Prepare a series of reactions with substrate concentration

[S]spanning a range typically from0.2 * K_Mto5 * K_M(a preliminary experiment may be needed to estimateK_M). Use a minimum of 6-8 different substrate concentrations. - Use appropriate buffer conditions (pH, ionic strength) and control temperature precisely using a water bath or thermocycler. Include necessary cofactors.

2. Initial Rate Measurement

- For each

[S], initiate the reaction and measure the initial velocity (v_0). This is the slope of the product formation (or substrate depletion) curve while less than 10% of the substrate has been converted [2]. - Use a sensitive detection method suitable for your reaction (e.g., spectrophotometry, fluorimetry, HPLC).

- Perform all measurements in triplicate to ensure data reliability.

3. Curve Fitting and Analysis

- Plot

v_0versus[S]. The resulting plot should be hyperbolic. - Fit the experimental data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot):

v_0 = (V_max * [S]) / (K_M + [S])[2] - From the fit, extract the values for

V_maxandK_M.

4. Parameter Calculation

- Calculate the turnover number using the determined

V_maxand the known total enzyme concentration:k_cat = V_max / [E_total][4] - Calculate the catalytic efficiency:

k_cat / K_M.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What does a high K_M value indicate about my enzyme, and how could this impact drug design?

A high K_M indicates low affinity between the enzyme and its substrate, meaning the enzyme requires a higher substrate concentration to reach half of its maximum velocity [2]. In drug design, if the target is a rate-limiting enzyme with a high K_M for its natural substrate, it may be more susceptible to competitive inhibition because a drug would not need to bind extremely tightly to effectively outcompete the substrate.

Q2: My k_cat / K_M value is far from the diffusion limit. Does this mean my enzyme is inefficient?

Not necessarily. While the diffusion limit (10⁸ – 10⁹ M⁻¹s⁻¹) represents a theoretical maximum, most natural enzymes operate well below this value [1]. An enzyme may be optimized for its specific cellular context (a local fitness peak), where factors like substrate flux, product inhibition, or regulatory networks are more important than raw catalytic speed. Inefficiency can even be a regulatory feature, as seen in G proteins [1].

Q3: When comparing two enzymes, is a higher k_cat / K_M always better?

The ratio k_cat / K_M is most appropriately used to compare an enzyme's activity on different, competing substrates—this is its original purpose as a "specificity constant" [6] [7]. Using it to compare two different enzymes acting on the same substrate can be misleading if not considered in the proper biological context, as other factors like in vivo concentration and regulation are critical [7].

Q4: What are common pitfalls that lead to inaccurate kinetic parameter determination?

- Incorrect

[E_total]: An inaccurate measurement of active enzyme concentration will directly lead to an erroneousk_cat[4]. - Not measuring initial rates: Allowing too much substrate to be consumed (>10%) violates the steady-state assumption of the Michaelis-Menten model [2].

- Poor substrate concentration range: If the highest

[S]does not saturate the enzyme, the fittedV_maxandK_Mwill be incorrect. - Ignoring environmental factors: pH, temperature, and ionic strength are critical for maintaining enzyme activity and stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Kinetic Experiments |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Enzyme | The catalyst under investigation. Must be purified, and its active concentration ([E_total]) must be accurately determined for k_cat calculation [4]. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) converted by the enzyme. Must be available in high purity. For k_cat / K_M studies, multiple competing substrates are used [6]. |

| Appropriate Buffer System | Maintains a stable pH to ensure consistent enzyme structure and function. The choice of buffer can affect enzyme activity. |

| Cofactors / Cations | Essential non-protein components required for the activity of many enzymes (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases, NADH for dehydrogenases). |

| Stopping Solution | Halts the enzymatic reaction at precise timepoints for accurate initial rate measurement (e.g., strong acid, denaturant). |

| Detection Reagents | Chemicals used to quantify reaction progress, such as chromogenic substrates, fluorescent probes, or coupled enzyme system components. |

In metabolic pathways, the rate-limiting step is the slowest step that determines the overall rate of the entire sequence of reactions, acting as a bottleneck. This step is often catalyzed by a specific enzyme whose activity controls the metabolic flux. Understanding and identifying these enzymes is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to modulate biochemical pathways, whether for enhancing the production of desired compounds, understanding disease mechanisms, or developing targeted therapies. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for experiments focused on these critical enzymes.

FAQ: Core Concepts and Identification

Q1: What defines an enzyme as the rate-limiting step in a pathway? A rate-limiting enzyme is defined by its catalysis of the slowest reaction in a pathway, which acts as a bottleneck and thus dictates the overall rate of the pathway's output. Its activity is often highly regulated and is typically the target for metabolic control [8].

Q2: What are the key kinetic parameters I need to measure? The two most critical parameters are the Michaelis constant (Km) and the maximum velocity (Vmax).

- Km (Michaelis Constant): Reflects the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate. A lower Km indicates higher affinity.

- Vmax (Maximum Velocity): The maximum rate of the reaction when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [9].

These parameters are determined experimentally and analyzed using plots like the Michaelis-Menten curve or the Lineweaver-Burk plot [9].

Q3: Can you give a classic example of a rate-limiting enzyme? In glycolysis, the enzyme phosphofructokinase (PFK) catalyzes the rate-limiting step. Its activity is allosterically regulated by factors such as ATP and fructose-2,6-bisphosphate, allowing the cell to match energy production with energy demand [8].

Q4: Why is improving the efficiency of a rate-limiting enzyme a key research goal? Enhancing the catalytic power of a rate-limiting enzyme can overcome the bottleneck of the entire enzymatic cycle, leading to significant gains in process output. For instance, improving the efficiency of rubisco, the rate-limiting enzyme in photosynthesis, could directly boost crop yields by enhancing carbon fixation [10].

Experimental Guide: Identifying and Characterizing a Rate-Limiting Enzyme

This section provides a detailed protocol for determining the kinetic parameters of an enzyme, a fundamental step in establishing its role as a pathway bottleneck.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key stages of a standard enzyme kinetics experiment.

Step-by-Step Protocol: Using Invertase as a Model Enzyme

This protocol is adapted from a practical biochemistry experiment designed for estimating Vmax and Km [9].

Objective: To determine the Vmax and Km of the invertase enzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of sucrose.

Materials and Reagents:

- Enzyme Source: Dry yeast (source of invertase) [9].

- Substrate: 0.4 M sucrose stock solution [9].

- Equipment: Test tubes, water bath (30°C), glucometer and strips, micropipettes, timer [9].

Procedure:

- Enzyme Solution Preparation: Suspend 0.25 g of dry yeast in 250 mL of warm distilled water (30°C). Let it sit in a 30°C water bath for 20 minutes with periodic stirring. This suspension is your invertase enzyme solution [9].

- Substrate Dilution Series: Prepare different concentrations of sucrose substrate by serially diluting the 0.4 M stock solution as shown in Table 1.

- Reaction Initiation: Pre-incubate the substrate tubes in a 30°C water bath for 10 minutes. Add 1 mL of the invertase enzyme solution to each substrate tube at one-minute intervals to stagger the start times [9].

- Reaction Termination and Measurement: After exactly 20 minutes from the time of enzyme addition for each tube, measure the concentration of glucose produced using a glucometer. Record the readings for each tube [9].

Data Analysis:

- Calculate Initial Velocity (V₀): Convert the glucose concentration from mg/dL to μmol/mL, then divide by the reaction time (20 minutes) to obtain the reaction velocity (V₀) in μmol/min/mL [9].

- Plot and Determine Kinetic Parameters:

- Michaelis-Menten Plot: Plot the sucrose concentration on the x-axis versus the initial velocity (V₀) on the y-axis. The curve will be hyperbolic. Vmax is estimated from the plateau of the curve, and Km is the substrate concentration at half of Vmax [9].

- Lineweaver-Burk Plot: Plot the inverse of sucrose concentration (1/[S]) on the x-axis versus the inverse of velocity (1/V₀) on the y-axis. This generates a straight line. Vmax is calculated from the y-intercept (1/Vmax), and Km is calculated from the x-intercept (-1/Km) [9].

Data Presentation: Kinetic Parameters

The table below summarizes example data and results from the invertase kinetics experiment.

Table 1: Example Data and Results from Invertase Kinetics Experiment

| Tube # | Sucrose Concentration (M) | Average [Glucose] (mg/dL) | Initial Velocity, V₀ (μmol/min/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.200 | 674 | 1.87 |

| 2 | 0.100 | 537 | 1.49 |

| 3 | 0.050 | 425 | 1.18 |

| 4 | 0.025 | 288 | 0.80 |

| 5 | 0.0125 | 198 | 0.55 |

| 6 | 0.00625 | 162 | 0.45 |

| Kinetic Parameter | Value (from Lineweaver-Burk plot) | Interpretation | |

| Vmax | ~2.1 μmol/min/mL | Maximum reaction rate | |

| Km | ~0.03 M | Michaelis constant |

Note: Data is adapted from the educational experiment. Values may vary in research settings [9].

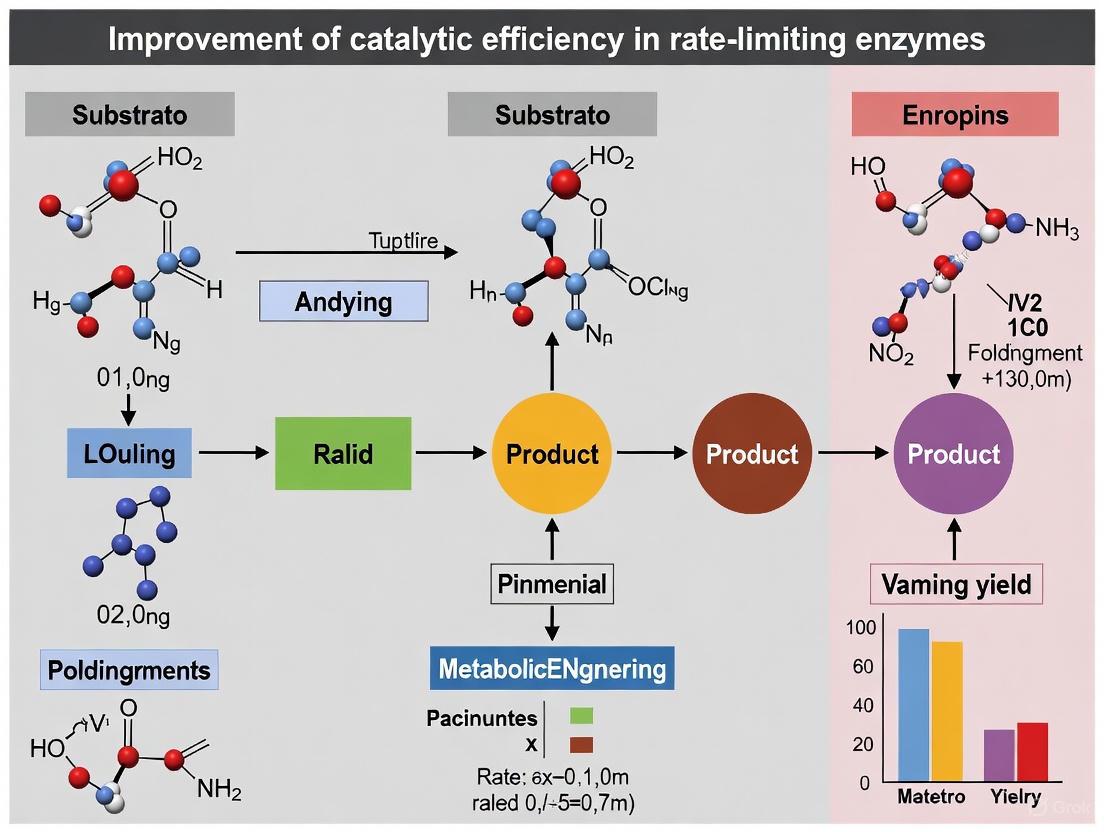

Advanced Strategies: Improving Catalytic Efficiency

Once a rate-limiting enzyme is identified, research often focuses on overcoming its limitations. The following diagram illustrates the strategic approach to enhancing enzyme efficiency.

Key Strategies:

- Directed Evolution: This powerful technique involves introducing random mutations into the enzyme's gene and then screening for variants with improved properties. MIT researchers successfully used a advanced method called MutaT7 to evolve a bacterial rubisco, enhancing its catalytic efficiency by up to 25% by making it less likely to react with oxygen [10].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Attaching enzymes to solid supports can enhance their stability and allow for reuse. Recent research developed a method for immobilizing enzymes on sponge-like silica particles, creating a highly efficient and reusable biocatalyst for industrial applications like flavor ester synthesis [11].

- Understanding Fundamental Mechanisms: Basic research can reveal new ways to improve enzymes. For example, studies on multi-substrate enzymes show they can use steric frustration to actively squeeze out a rate-limiting product, facilitating the enzymatic cycle [12].

- Computational and Data-Driven Approaches: The accumulation of experimental data now allows for data-driven enzyme engineering. These approaches help predict single-step reactions, optimize pathways, and design enzymes with specific catalytic functions, accelerating discovery [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Kinetics and Engineering

| Item | Function/Application | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Dry Yeast (S. cerevisiae) | Source of commercially available and inexpensive enzymes for educational and research experiments. | Serves as the source of the invertase enzyme for kinetic studies [9]. |

| Glucometer | A rapid and accessible tool for measuring the concentration of a specific product (glucose) in real-time. | Used to track the progress of the invertase-catalyzed hydrolysis of sucrose by measuring glucose production [9]. |

| MutaT7 Plasmid System | A continuous directed evolution technology that enables high-rate mutagenesis of a target gene within living cells. | Used by MIT chemists to rapidly generate and screen for improved variants of the rubisco enzyme with higher efficiency [10]. |

| Designed Silica Particles | A solid support for enzyme immobilization, enhancing stability and enabling catalyst reuse. | Used to create a highly efficient and reusable biocatalyst for the synthesis of flavor esters [11]. |

| Specialized Expression Vectors | For cloning and expressing target enzymes in model organisms like E. coli. | Essential for conducting directed evolution experiments and producing engineered enzyme variants for characterization [10]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q: My Michaelis-Menten plot does not show a clear plateau. How can I accurately determine Vmax? A: A poorly defined plateau often means the highest substrate concentrations tested were not sufficient to saturate the enzyme. To resolve this, increase the range of your substrate concentrations, ensuring you include higher values. For a more accurate determination of Vmax and Km, use the Lineweaver-Burk plot, which linearizes the data [9].

Q: I am getting high variability in my reaction velocity measurements between replicates. A: This is a common issue. Focus on:

- Precise Temperature Control: Use a calibrated water bath and pre-incubate all solutions.

- Accurate Timing: Use a precise timer and strictly adhere to reaction start/stop times.

- Consistent Enzyme Addition: Ensure the enzyme is well-mixed and added consistently across all tubes [9].

Q: My engineered enzyme is expressed in E. coli but shows low activity or solubility. A: This is a frequent challenge in enzyme engineering. Beyond targeting the active site, look for mutations that improve the enzyme's folding and stability. In the MIT rubisco study, past efforts showed that improvements in stability and solubility resulted in small but important gains in overall enzyme efficiency [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Studying Distal Mutations

Problem: Introduced distal mutation results in poor protein expression or stability.

- Potential Cause: The mutation may be destabilizing the protein core or causing aggregation, especially if it introduces a hydrophobic residue on the surface or disrupts key packing interactions.

- Solution:

- Check protein solubility and oligomeric state immediately after purification using size-exclusion chromatography [14].

- Perform circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to assess if the mutation has altered the secondary structure [14].

- Measure thermal stability (Tm) by using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) or CD to monitor unfolding [15] [16].

- Consider employing a conservative substitution (e.g., Trp to Phe instead of Trp to Ala) to maintain structural volume and hydrophobic/aromatic interactions [14].

Problem: A distal mutation shows no significant improvement in catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) when introduced alone.

- Potential Cause: The beneficial effect of a distal mutation is often contingent on the presence of active-site mutations. Distal mutations frequently optimize steps like substrate binding or product release, the benefits of which only become apparent after the chemical transformation step (kcat) has been improved [15].

- Solution:

- Introduce the distal mutation into a background that already contains beneficial active-site ("Core") mutations.

- Analyze individual kinetic parameters (kcat and KM) separately instead of just the overall kcat/KM. A distal mutation may significantly improve KM without a large effect on kcat, or vice versa [15].

- Use methods like hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) to detect changes in protein dynamics and flexibility that may not be reflected in initial activity screens [14].

Problem: Difficulty in predicting which distal residues to mutate.

- Potential Cause: Identifying functionally relevant distal sites from a static structure is challenging, as they often form part of dynamic allosteric networks [14] [17].

- Solution:

- Utilize co-evolution analysis from multiple sequence alignments to identify residues that mutate in a correlated manner, as these often form functional networks [17].

- Employ molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify residues that are part of correlated motion networks or that influence the flexibility of active-site loops [15] [14].

- Use computational tools like B-FIT analysis to identify flexible regions in the protein that can be targeted for stabilization through mutations [17].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is defined as a "distal" mutation in an enzyme? A distal mutation is one where the amino acid residue is not within van der Waals distance of the substrate, cofactor, or product molecule. These residues are typically located in the second coordination shell around the active site, or even further away on the protein surface [17]. In practice, they are often more than 10-15 Ångströms from the active site [14].

Q2: How can a mutation far from the active site possibly affect catalysis? Distal mutations primarily influence enzyme function by modulating protein dynamics and conformational landscapes [15] [17]. They can:

- Widen the active-site entrance to facilitate substrate binding and product release [15].

- Reorganize surface loops that control access to the active site [15] [16].

- Alter the energy landscape to shift the population of enzymes toward catalytically competent conformations [14].

- Change the rate-limiting step of the catalytic cycle, leading to epistatic interactions with other mutations [16].

Q3: In directed evolution, why do so many beneficial distal mutations appear? Directed evolution selects for any mutation that enhances overall catalytic efficiency, regardless of its location. While active-site mutations are crucial for optimizing the chemical transformation step, distal mutations are often selected because they complement this by enhancing other steps in the catalytic cycle, such as substrate binding or product release [15]. Furthermore, they can alleviate trade-offs between activity and stability introduced by active-site mutations [15].

Q4: Are distal mutations generally beneficial on their own? Not always. The effect of a distal mutation is often highly context-dependent, showing strong epistasis with other mutations in the protein [15] [16]. A distal mutation that is neutral or slightly detrimental in the wild-type background can become highly beneficial when combined with specific active-site mutations, as it may fine-tune a dynamic network that was altered by the primary mutation [16].

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Impact of Distal Mutations on Catalytic Efficiency

Table 1: Catalytic Efficiency of Kemp Eliminase Variants [15]

| Enzyme Variant | # of Distal Mutations | kcat/KM (M⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Fold Increase vs. Designed |

|---|---|---|---|

| HG3-Designed | - | 1,300 ± 90 | - |

| HG3-Shell | 9 | 4,900 ± 500 | 4 |

| HG3-Core | 0 | 120,000 ± 20,000 | 90 |

| HG3-Evolved | 9 | 150,000 ± 40,000 | 120 |

| 1A53-Designed | - | 4.6 ± 0.4 | - |

| 1A53-Shell | 8 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | ~1 |

| 1A53-Core | 0 | 7,000 ± 3,000 | 1,500 |

| 1A53-Evolved | 8 | 14,000 ± 3,000 | 3,000 |

Table 2: Effect of Distal Point Mutations in Human Monoacylglycerol Lipase (hMGL) [14]

| Mutant | Location from Active Site | Catalytic Efficiency Impact |

|---|---|---|

| W35A | Distal | Minimal effect |

| W289L | >18 Å | ~100,000-fold decrease |

| W289F | >18 Å | Almost no effect |

| L232G | >18 Å | Significant decrease |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing the Role of Distal Mutations

Objective: To systematically investigate the functional and structural effects of distal mutations identified through directed evolution.

Materials:

- Plasmids: Gene constructs for the "Designed" (original), "Core" (active-site mutations only), "Shell" (distal mutations only), and "Evolved" (all mutations) enzyme variants [15].

- Expression System: E. coli expression strains (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Purification: Affinity chromatography resin (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins).

- Assay Reagents: Substrate (e.g., 5-nitrobenzisoxazole for Kemp eliminases [15]), appropriate reaction buffer, and a spectrophotometer.

- Structural Biology: Crystallization screens, X-ray source, molecular dynamics simulation software (e.g., GROMACS).

Methodology:

- Protein Engineering: Generate "Shell" and "Core" variants by introducing the respective sets of mutations into the "Designed" gene using site-directed mutagenesis [15].

- Expression and Purification:

- Kinetic Characterization:

- Determine kinetic parameters (KM and kcat) by measuring initial reaction rates (v0) at varying substrate concentrations.

- Perform reactions in triplicate using at least two independent protein batches for statistical robustness [15].

- Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten model to obtain KM and kcat, and calculate catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM).

- Stability Assessment:

- Determine the melting temperature (Tm) using Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) or CD spectroscopy to monitor thermal denaturation [15].

- Structural Analysis (If Resources Allow):

- X-ray Crystallography: Solve crystal structures of key variants (e.g., Core and Shell) in apo form and bound to a transition-state analogue. This reveals static structural changes, such as active-site preorganization or widening of the active-site entrance [15].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Run MD simulations (e.g., 100 ns - 1 µs) to analyze conformational dynamics, root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of residues, and correlated motions. This can show how distal mutations alter dynamic allosteric networks [15] [14].

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): Use HDX-MS to probe changes in protein flexibility and dynamics upon introducing distal mutations, identifying regions with altered solvent accessibility [14].

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

How Distal Mutations Enhance Catalysis

Rate-Limiting Step Shift in β-Lactamase Evolution [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Distal Mutations

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Kemp Elimination Substrates (e.g., 5-nitrobenzisoxazole) | Model substrate for benchmarking designed enzymes and studying fundamental catalytic mechanisms [15]. | Used in kinetic assays for Kemp eliminases like HG3, KE70 [15]. |

| Transition-State Analogue (e.g., 6-nitrobenzotriazole - 6NBT) | Used in X-ray crystallography to capture and visualize the enzyme in its catalytically relevant conformation [15]. | Reveals if active site is preorganized and how mutations affect ligand binding [15]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Allows for precise introduction of specific point mutations (Core, Shell) into gene constructs. | Essential for creating isogenic series of variants (Designed, Core, Shell, Evolved) for controlled comparisons [15]. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Column | Assesses protein oligomeric state, purity, and potential aggregation following mutagenesis [14]. | Critical quality control step after purification; mutants like W289A in hMGL showed low expression [14]. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) Dyes (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | High-throughput method to determine protein thermal stability (Tm) and the impact of mutations on folding [15]. | Helps distinguish if functional changes are due to stability or direct dynamic effects [15] [16]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Computationally models protein dynamics and conformational sampling, revealing allosteric networks [15] [14]. | Can simulate the effect of distal mutations on active-site geometry and loop motions inaccessible to crystallography [15]. |

FAQs: Resolving Key Questions on Distal Residue Functions

FAQ 1: What are distal residues, and why are they important if they are not in the active site? Distal residues are amino acids located far from an enzyme's active site. While they do not directly participate in chemistry, they are critical for the full catalytic cycle. Recent research demonstrates that distal residues enhance catalysis by facilitating substrate binding and product release. They achieve this by tuning the protein's structural dynamics, such as widening the active-site entrance and reorganizing surface loops, which helps the enzyme progress efficiently through all steps of its catalytic cycle [15] [18].

FAQ 2: My engineered enzyme has high catalytic proficiency (kcat) but low overall efficiency (kcat/KM). Could distal residues be the issue? Yes, this is a classic symptom. A high kcat indicates a well-organized active site capable of fast chemical transformation. However, a low kcat/KM often points to inefficiencies in substrate binding or product release. Distal mutations have been shown to specifically address these bottlenecks. For example, in engineered Kemp eliminases, distal ("Shell") mutations enhanced catalytic efficiency by modulating these very steps, even when the core active site was already optimized [15] [19].

FAQ 3: How can I identify which distal residues to target for engineering in my enzyme of interest? A combined computational and experimental approach is recommended:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Run MD simulations to identify residues involved in dynamic networks that influence the active site's conformational flexibility and entrance geometry.

- Analysis of Directed Evolution Hits: If you have evolved a more efficient enzyme, analyze the mutations. Those distant from the active site that confer a benefit are prime candidates [15] [18].

- Conservation Analysis: Tools like ConSurf can identify evolutionarily conserved distal residues that may be important for function [20].

FAQ 4: I introduced a beneficial distal mutation, but my enzyme's stability decreased. What happened? The relationship between distal mutations and stability is complex and not always predictable. While some distal mutations stabilize, others can be destabilizing. For instance, in one study, the 1A53-Shell variant showed reduced solubility and stability despite being functionally beneficial [15]. This indicates that distal mutations are primarily selected to enhance catalytic efficiency, and their effects on stability can be variable. If a mutation is beneficial for catalysis but destabilizing, you may need to find compensatory mutations or use enzyme immobilization techniques to enhance robustness.

FAQ 5: We only have a cryo-cooled (cryo) crystal structure of our enzyme. Is this sufficient to understand the role of distal residues? Cryo-structures are invaluable snapshots, but they may not capture the full range of motion required for catalysis. A single static structure can be misleading. Ensemble-function analysis using room-temperature crystallography or multiple cryo-structures is often necessary to understand the conformational landscape that distal residues help shape [21]. Relying solely on a single static structure may cause you to overlook critical dynamic effects that facilitate substrate binding and product release.

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Experimental Challenges

Problem: Poor Substrate Access to Active Site

Symptoms: Low catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) even with a properly configured active site; substrate saturation is difficult to achieve. Potential Cause: The active site entrance may be too narrow or gated by flexible loops, hindering substrate diffusion. Solutions:

- Identify Bottlenecks: Use MD simulations to analyze the equilibrium between "open" and "closed" states of the active site entrance. Look for distal residues that control this equilibrium.

- Engineer Loops: Target distal residues on surface loops surrounding the active site entrance. As demonstrated in Kemp eliminases, mutations here can widen the entrance and facilitate substrate binding [15] [18].

- Check Rigidity: Introduce mutations that tune the flexibility of loops controlling access, finding a balance that allows both easy substrate entry and precise transition-state stabilization.

Problem: Slow Product Release Causing Product Inhibition

Symptoms: Reaction rate decreases significantly as product accumulates; adding more substrate does not restore the initial rate. Potential Cause: The product remains bound in the active site, preventing the next catalytic cycle. Solutions:

- Modulate Dynamics: Beneficial distal mutations often alter the energy landscape of the enzyme to lower the barrier for product dissociation. Analyze evolved variants to identify such mutations [15].

- Weaken Product Affinity: While maintaining strong transition-state binding, distal mutations can subtly rearrange the active site to weaken product binding, facilitating its release.

- Promote Conformational Change: Engineer distal sites that are part of alloster networks which, when mutated, induce a conformational change that "pushes" the product out.

Problem: Introduced Distal Mutation Has No Effect or is Detrimental

Symptoms: A rationally chosen or evolution-derived distal mutation does not improve activity or even decreases it. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Epistasis: The effect of a distal mutation can depend on the presence of other mutations (epistatic interactions). A mutation that works in an evolved background may not work in the wild-type scaffold. Always consider the genetic context [15].

- Over-stabilization: The mutation might have overly rigidified a necessary dynamic motion. Seek a different mutation that provides a more balanced flexibility.

- Disrupted Allosteric Network: The mutation may have disrupted a subtle but important communication network. Use computational methods to map allosteric pathways before mutating.

Quantitative Data: Catalytic Enhancements from Distal and Core Mutations

The table below summarizes kinetic data from a key study on de novo Kemp eliminases, comparing the effects of active-site ("Core") and distal ("Shell") mutations. The data clearly show their distinct and synergistic roles [15] [18].

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters of Kemp Eliminase Variants

| Enzyme Series | Variant | # Mutations | kcat (s⁻¹) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Fold Increase (kcat/KM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG3 | Designed | - | N.D. | N.D. | 1,300 ± 90 | - |

| Shell | 9 | N.D. | N.D. | 4,900 ± 500 | 4 | |

| Core | 7 | 230 ± 20 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 120,000 ± 20,000 | 90 | |

| Evolved | 16 | 320 ± 30 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 150,000 ± 40,000 | 120 | |

| 1A53 | Designed | - | N.D. | N.D. | 4.6 ± 0.4 | - |

| Shell | 8 | N.D. | N.D. | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 1 | |

| Core | 6 | 13 ± 2 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 7,000 ± 3,000 | 1,500 | |

| Evolved | 14 | 19 ± 2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 14,000 ± 3,000 | 3,000 | |

| KE70 | Designed | - | N.D. | N.D. | 150 ± 7 | - |

| Shell | 2 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 130 ± 30 | 1 | |

| Core | 6 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 22,000 ± 4,000 | 150 | |

| Evolved | 8 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 26,000 ± 2,000 | 170 |

N.D.: Not Determinable - Saturation was not achieved at maximum substrate solubility.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Workflow 1: Systematic Analysis of Distal Residue Effects

This workflow outlines the key steps for deconstructing the role of distal residues in an enzyme, as employed in recent groundbreaking studies [15] [18].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing distal residue effects.

Detailed Protocols:

- Generating Core & Shell Variants:

- Enzyme Kinetics Assay:

- Procedure: Perform initial rate measurements under steady-state conditions across a range of substrate concentrations. Use a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, with 100 mM NaCl). Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten model to extract kcat and KM.

- Troubleshooting: If saturation is not achieved due to low substrate solubility, calculate kcat/KM directly from the initial linear slope of the v0 vs. [S] plot [15] [18].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations:

- Setup: Solvate the enzyme in a water box with ions. Use a force field like AMBER or CHARMM.

- Analysis: Run simulations for hundreds of nanoseconds. Quantify root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of residues, distances between key residues, and the radius of gyration of the active site entrance. Compare simulations of Shell/Designed variants to identify changes in dynamics [15].

Workflow 2: Computational Pipeline for Rational Design

This workflow, derived from successful iGEM and other research projects, uses computational tools to prioritize distal residues for mutagenesis [20].

Diagram 2: Computational design pipeline for targeting distal residues.

Detailed Protocols:

- Conservation Analysis with ConSurf:

- Procedure: Submit your enzyme's sequence to the ConSurf server. It will identify evolutionarily conserved and variable positions.

- Interpretation: Highly conserved distal residues are strong candidates for being part of important dynamic or allosteric networks [20].

- Predicting Free-Energy Changes with FoldX/Rosetta:

- Procedure: Use the FoldX FoldX or Rosetta RosettaDDG applications. Input the protein structure and your proposed mutation (e.g., A150V).

- Output: The software calculates the change in folding free energy (ΔΔG). This helps flag mutations that might be highly destabilizing. Typically, |ΔΔG| < 2-3 kcal/mol is considered safe for experimental testing [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Distal Residue Research

| Category | Item | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering | Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces specific point mutations into plasmid DNA. | Kits from Agilent, NEB, or similar. |

| Heterologous Expression System | Produces the engineered enzyme. | E. coli BL21(DE3) is a common host. | |

| Structural Biology | Transition-State Analogue | Used in crystallography to trap the enzyme in a catalytically relevant state. | e.g., 6-nitrobenzotriazole for Kemp eliminases [15]. |

| Crystallization Screens | Empirically finds conditions for growing protein crystals. | Commercial screens from Hampton Research or similar. | |

| Biophysical Analysis | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Measures protein thermal stability (Tm) upon mutation. | Detects destabilizing mutations [15]. |

| Spectrophotometer & Cuvettes | Essential for running continuous enzyme kinetic assays. | Measures substrate depletion/product formation. | |

| Computational Tools | Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates protein motion to identify dynamic networks. | GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD. |

| ConSurf Web Server | Analyzes evolutionary conservation of residues. | Identifies functionally important distal sites [20]. | |

| FoldX / Rosetta | Quickly predicts the stability effect of mutations (ΔΔG). | Used for pre-screening mutation candidates [20]. | |

| PyMOL / ChimeraX | Visualizes protein structures, mutations, and dynamics. | Critical for analysis and figure generation. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Detecting and Characterizing Allosteric Communication Pathways

Problem: Difficulty in detecting allosteric communication pathways and quantifying their effect on active site preorganization.

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution | Key Performance Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| No observable allosteric signal in biochemical assays | The experimental conditions (e.g., temperature, buffer) may not allow the dynamic allosteric networks to be populated or detected [22]. | Utilize a combination of biophysical techniques. Employ NMR spectroscopy to probe picosecond-nanosecond local and microsecond-millisecond conformational exchange dynamics [23]. Complement this with Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) to identify protein regions that become more or less dynamic upon allosteric perturbation [24]. | Detection of residue-specific changes in dynamics; Identification of regions with altered solvent accessibility. |

| Weak or inconsistent effector binding data | The allosteric communication may be entropically driven, involving changes in the broadness of the free energy landscape rather than a large conformational shift [23]. | Perform temperature-dependent studies. Conduct experiments across a range of temperatures (e.g., 30°C to 50°C) as temperature increases can activate structural and dynamical patterns that mimic effector-induced allostery, helping to reveal the network [22]. | Observation of a temperature-dependent activation that resembles effector binding; Correlation between dynamics and function. |

| Inability to identify key residue networks | Traditional static structures (e.g., from cryo-crystallography) may miss low-population or transient conformational states that are critical for allostery [25]. | Employ multi-dimensional crystallography. Collect X-ray diffraction data at both cryogenic and ambient/physiological temperatures. Room-temperature crystallography can reveal previously hidden minor conformations and conformational substates that are frozen out at cryogenic temperatures [25]. | Visualization of alternative side-chain rotamers and backbone conformations in electron density; Identification of allosteric networks converging on the active site [25]. |

Resolving Challenges in Enzyme Kinetics and Mutant Analysis

Problem: Unexpected or uninterpretable changes in catalytic efficiency upon mutagenesis of allosteric or active site residues.

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution | Key Performance Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant shows no activity, complicating dynamics analysis | Nonconservative mutations of catalytic triad residues (e.g., Ser→Ala, His→Ala, Asp→Ala) can lead to a complete or near-complete loss of enzymatic activity [24]. | Monitor conformational states directly. Use solution NMR to detect and quantify the populations of active and inactive conformers, even in catalytically incompetent mutants. Specific downfield NMR resonances are sensitive to open-closed interconversions, allowing quantification of conformational gating [24]. | NMR spectral pattern distinct to open (active) and closed (inactive) forms; Quantification of population shifts despite lost activity. |

| Mutant has activity but altered kinetics, and the structural basis is unclear | The mutation may cause subtle population shifts in conformational ensembles or alter dynamic allosteric networks without major structural changes [26]. | Combine computational and experimental dynamics. Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in conjunction with NMR/HDX-MS. MD can provide atomistic details of the communication pathways and conformational sampling, while experimental data validates the simulations [23] [22]. | Agreement between simulated conformational ensembles and experimental dynamics data; Identification of correlated motions and communication pathways. |

| Discrepancy between predicted and observed effects of allosteric modulators | The allosteric modulator may be functioning as a positive (PAM) or negative (NAM) allosteric modulator, and its effect is highly dependent on the existing conformational equilibrium of the enzyme [27]. | Characterize the modulator's effect on the conformational ensemble. Determine if the compound stabilizes the active (e.g., increasing the population of the "open" state) or inactive conformation. This can be achieved via NMR or by using conformational biosensors [27] [24]. | A shift in the equilibrium toward the active or inactive state observed via NMR; Corresponding increase or decrease in substrate binding affinity. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a traditional orthosteric inhibitor and an allosteric modulator?

A: Orthosteric drugs bind directly to the active site of an enzyme, competing with the natural substrate and typically acting as "on/off" switches. In contrast, allosteric modulators bind at a distal site, inducing conformational changes that fine-tune the activity at the active site. Allosteric modulators can be Positive (PAMs) or Negative (NAMs) and often function like a "dimmer switch," offering greater potential for specificity and reduced side effects [27].

Q2: Our crystallographic structures show minimal structural changes upon allosteric effector binding. Does this mean the allostery is not conformational?

A: Not necessarily. Allostery can be "entropically driven," where the effector changes the conformational landscape without shifting the minimum position of the free energy basin. It alters the breadth of the basin and the dynamic properties of the protein (motion amplitudes, rates of transition), which preorganizes the active site without a major conformational rearrangement. This underscores the importance of measuring dynamics, not just static structures [23].

Q3: How can we experimentally identify which residues are part of an allosteric network?

A: Key techniques include:

- NMR Spectroscopy: Identifies residues involved in communication by monitoring effector-induced changes in chemical environment and dynamics across picosecond-to-millisecond timescales [23] [22].

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): Pinpoints protein regions that become more or less dynamic (protected or de-protected from exchange) upon allosteric perturbation, often revealing long-range communication channels [24].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Computationally models correlated motions and can predict pathways of communication between the allosteric and active sites [23] [22].

- Temperature-Dependent Crystallography: Collecting structures at room temperature and higher can reveal "hidden" conformations and allosteric networks that are not observable in cryo-cooled crystals [25].

Q4: Why should we consider temperature as a critical variable in our allostery experiments?

A: Research has shown that for some enzymes, a simple increase in temperature can activate the same structural and dynamical pattern as an allosteric effector. Temperature is a key condition that activates allostery on effector binding. Studying a protein across a temperature gradient can serve as a surrogate for effector binding and provide a powerful tool to map allosteric networks [22].

Experimental Protocols & Data

The table below summarizes data from a study on human Monoacylglycerol Lipase (hMGL), demonstrating how mutations in the catalytic triad affect both enzyme efficiency and the population of active conformations.

| hMGL Construct | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km, relative to sol-hMGL) | Population of Active Conformation at 310 K |

|---|---|---|

| sol-hMGL (template) | 1.0 | 85% |

| S122A | ~0 (Complete loss) | 40% |

| H269A | ~0 (Complete loss) | 45% |

| D239A | 1/137.2 | 55% |

| D239N | 1/87.4 | 60% |

| L241A | 1/1.8 | 75% |

| C242A | 1/5.5 | 70% |

Protocol for Probing Allostery via Integrated NMR and HDX-MS

Objective: To identify allosteric networks and quantify their impact on active site preorganization and dynamics.

Methodology:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare protein samples (wild-type and relevant mutants, e.g., catalytic triad mutants like D239A) in a suitable buffer for NMR and HDX-MS.

- Prepare separate samples for: Apo state, Effector-bound state, Substrate-bound state, Ternary complex (Effector + Substrate).

NMR Dynamics Measurements:

- Experiment: Perform

$^{15}$Nrelaxation dispersion experiments to probe microsecond-to-millisecond conformational exchange processes [23]. - Analysis: Identify residues that show changes in dynamics parameters (e.g., Rex) upon effector binding. These residues are potential components of the allosteric network.

- Experiment: Perform

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS):

- Experiment: Dilute the protein samples (from Step 1) into a D`$_2$O-based buffer for various time points (e.g., 10s, 1min, 10min, 1h). Quench the reaction and digest the protein.

- Analysis: Use mass spectrometry to measure the deuterium uptake for each peptide over time. Peptides from regions that become more dynamic upon mutation (e.g., in D239A) will show increased deuterium uptake, while stabilized regions will show decreased uptake [24].

Data Integration:

- Correlate the residues and regions identified by NMR and HDX-MS. A robust allosteric network will show changes in both conformational dynamics (NMR) and solvent accessibility/exchange (HDX-MS).

- Map these residues onto the protein structure to visualize the physical pathway connecting the allosteric and active sites.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

Allosteric Communication Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Allostery Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Allostery Research |

|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | For creating point mutations in catalytic triad (e.g., S122A, D239N) and putative allosteric network residues to probe their functional and dynamic roles [24]. |

Stable Isotope-Labeled Proteins ($^{15}$N, $^{13}$C) |

Essential for NMR spectroscopy studies, allowing residue-specific assignment and detailed characterization of protein backbone and side-chain dynamics [23] [24]. |

| Allosteric Modulators (PAMs/NAMs) | Chemical tools to selectively stabilize active or inactive conformations. Used to perturb the system and study the resulting structural, dynamic, and functional changes [27]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | For running atomic-level simulations to visualize conformational sampling, identify correlated motions, and predict communication pathways that are difficult to capture experimentally [23] [26] [22]. |

| Crystallography Software Suites (e.g., SBGrid) | Provides comprehensive software for structure determination, refinement, and analysis, including tools for handling multi-temperature and time-resolved crystallography data [25] [28]. |

The Enzyme Engineer's Toolkit: From Directed Evolution to Computational Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: After several rounds of evolution, my enzyme's activity is no longer improving. What could be the cause? You have likely reached an optimization plateau, a common challenge in directed evolution. This can be caused by several factors [29]:

- Marginal Protein Stability: Many beneficial mutations can slightly destabilize the enzyme's structure. After multiple rounds, the enzyme may be on the verge of unfolding, and further mutations that increase activity are impossible without first stabilizing the scaffold.

- Epistatic Interactions: The effect of a new mutation often depends on the existing mutations in the background (a phenomenon called epistasis). A mutation that would be beneficial may appear neutral or even detrimental if introduced in the wrong order, leading to a "local fitness peak" from which it is hard to escape.

- Activity-Stability Trade-offs: Mutations that significantly enhance catalytic activity can sometimes come at the cost of stability, especially under applicative conditions like elevated temperature or non-physiological pH.

Q2: My hybrid repressor, created by fusing DNA-binding and ligand-binding modules, shows poor performance. How can I fix it? Poor performance in hybrid repressors is often due to the loss of critical inter-module interactions that are essential for allosteric regulation [30]. A strategy to rescue these hybrids involves:

- Coevolutionary Analysis: Use computational models to analyze co-evolving residue pairs at the interface of the two modules from thousands of natural homologs.

- Identify Compensatory Mutations: The model will predict specific point mutations in the ligand-binding module that can reestablish native-like interactions with the DNA-binding module.

- Experimental Validation: Introducing the top-predicted triple mutations has been shown to significantly improve the dynamic range of gene expression induction in non-functional hybrid repressors [30].

Q3: How can I improve the catalytic efficiency of an enzyme under non-optimal pH conditions, such as neutral pH? Traditional directed evolution is often performed at the enzyme's optimal pH, which may not align with application needs. A modern approach is Machine Learning (ML)-guided engineering [31]:

- Data Generation: Systematically measure the activity of a library of enzyme variants under a series of different pH conditions.

- Model Training: Use this high-quality experimental data to train a machine learning model that can predict catalytic activity based on the variant sequence and the pH condition.

- Rational Design: The trained ML model can then guide you to design variants predicted to have high activity at your desired pH (e.g., pH 7.5), often achieving several-fold improvements.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Optimization Plateau in Catalytic Efficiency

Problem: Despite iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening, no further improvements in kcat/KM are observed.

Investigation and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Approach | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Protein Stability | Perform thermal shift assays or measure melting temperature (Tm). If stability is low, the enzyme may aggregate or inactivate easily. | Introduce stabilizing mutations (e.g., from consensus sequences or computational design) that do not directly affect the active site. This can open new evolutionary trajectories [29]. |

| Local Fitness Peak | Analyze historical data for sign epistasis. Test known beneficial mutations in different genetic backgrounds. | Use random mutagenesis or DNA shuffling to introduce larger genetic jumps, helping to escape the local peak. Neutral drift libraries can also explore sequence space without selection pressure [29]. |

| Conformational Inefficiency | Use techniques like NMR spectroscopy to see if the enzyme exists in an equilibrium between active and inactive states [32]. | Focus evolution on mutating residues involved in the global conformational network. Select for mutations that shift the equilibrium toward the active conformation, as was key in optimizing the HG3 Kemp eliminase [32]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Conformational States via NMR [32]

- Sample Preparation: Produce ^15^N-labeled protein for the wild-type and evolved enzyme variants.

- Data Acquisition: Record 2D ^1^H-^15^N HSQC NMR spectra at multiple temperatures (e.g., 10°C to 40°C) and pH values.

- Analysis:

- Look for peak duplication, which indicates slow exchange between two or more conformational states on the NMR timescale.

- Estimate the population of each state by measuring cross-peak volumes.

- Correlate the population of the "active" state with the enzyme's catalytic efficiency to confirm its functional importance.

Issue: Poor Performance in Hybrid Modular Repressors

Problem: A hybrid repressor, created by swapping DNA-binding and ligand-binding modules, shows a low dynamic range of induction.

Solution: Coevolutionary-Guided Rescue [30]

Step 1: Compute a Compatibility Score

- Use a computational model based on a multiple sequence alignment of your protein family (e.g., LacI) to calculate a compatibility score

C(S)for your hybrid repressor sequence. This score uses inter-modular coevolutionary coupling strength to infer functional compatibility.

Step 2: Predict Rescue Mutations

- Systematically compute how all possible single mutations in the Ligand-Binding Module (LBM) affect the

C(S)score. - Generate a heatmap to identify the most favorable mutations (e.g., K57V, F75G).

- Proceed to predict the top double and triple mutants with the best-improved scores.

Step 3: Construct and Test Mutants

- Synthesize and clone the genes for the top-predicted triple mutants.

- Experimentally characterize the mutants by measuring the dose-response curve to the inducer and calculating the new dynamic range (fold-induction). Successful rescues have shown improvements from less than 5-fold to over 50-fold induction [30].

Experimental Data and Protocols

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR | Uses PCR under mutagenic conditions to introduce random point mutations. | Easy to perform; does not require prior structural knowledge. | Biased mutagenesis spectrum; reduced sampling of sequence space. |

| DNA Shuffling | Fragments of homologous genes are reassembled randomly by PCR. | Recombines beneficial mutations from multiple parents. | Requires high sequence homology between parents. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | A specific residue is mutated to all other 19 amino acids. | In-depth exploration of a chosen position's function. | Libraries can become very large if many positions are targeted. |

| RAISE | Inserts random short insertions and deletions. | Can explore indels, a common source of variation in nature. | Often introduces frameshifts, disrupting the protein. |

| Enzyme Variant | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) Improvement | Population of Inactive State at 25°C | Key Structural Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HG3 (Initial Design) | Baseline | ~25% | Two distinct backbone conformations (active/inactive) observed in crystal structures. |

| HG3.7 (Intermediate) | Increased | ~25% | Similar conformational heterogeneity to HG3. |

| HG3.17 (Optimized) | ~200-fold over HG3; nearly billion-fold over uncatalyzed reaction | ~5% | A single, primed active conformation is observed; the inactive state is highly disfavored. |

Experimental Protocol: Directed Evolution Workflow for Improved Catalytic Efficiency [33] [34]

The core cycle of directed evolution involves three key steps, iterated until the desired activity is achieved. The workflow is highly generalizable and can be applied to improve various enzyme properties.

- Diversification: Create a library of gene variants. Error-prone PCR is a common method where the gene of interest is amplified using PCR under conditions that reduce the fidelity of the DNA polymerase (e.g., unbalanced dNTPs, addition of Mn2+), introducing random point mutations.

- Screening/Selection: Identify improved variants from the library.

- Screening: Assay individual clones for the desired activity (e.g., using 96-well plates with colorimetric or fluorimetric assays).

- Selection: Link the desired function to cell survival or fluorescence, enabling high-throughput enrichment using methods like FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting).

- Amplification: The gene from the best-performing variant is amplified using PCR. This gene then serves as the template for the next round of diversification, continuing the evolutionary cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Directed Evolution |

|---|---|

| Kapa Biosystems Polymerases | Engineered via directed evolution for enhanced performance in PCR, qPCR, and NGS applications, providing higher fidelity, processivity, and inhibitor resistance than wild-type enzymes [34]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | A high-throughput screening tool that can analyze and sort up to millions of individual cells based on fluorescence, which can be linked to enzymatic activity or binding events [33]. |

| Cell-Free Gene Expression (CFE) System | Allows for rapid in vitro synthesis and testing of protein variants without the need for cellular transformation, dramatically speeding up the "build-test" cycle in enzyme engineering [35]. |

| Transition-State Analog (TSA) | A stable molecule that mimics the transition state of an enzymatic reaction. It is used in binding studies (e.g., stopped-flow kinetics, NMR) to probe the efficiency of transition-state stabilization, which is directly related to catalytic rate enhancement [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is combinatorial pathway optimization and why is it necessary? Combinatorial pathway optimization is a multivariate approach in metabolic engineering where several pathway elements, such as coding sequences or expression levels of multiple genes, are diversified simultaneously rather than one at a time [36] [37]. This is necessary because classical sequential "de-bottlenecking" often fails to identify globally optimal solutions due to the intricate orchestration of cellular metabolism and holistic interactions between pathway components [36]. By testing combinations of variations, this method pragmatically addresses metabolic flux imbalances that can lead to toxic intermediate accumulation, side product formation, and low product yield, even with limited a priori knowledge of the pathway [36].

FAQ 2: What are the primary strategies for creating diversity in a pathway? There are three primary diversification strategies, which can be used individually or in combination [36]:

- Variation of Coding Sequences (CDS): Using different structural or functional gene homologues or metagenomic libraries to find enzymes with superior catalytic properties for a specific reaction in your host [36].

- Engineering of Expression Levels: Fine-tuning the relative and absolute expression levels of genes by manipulating gene dosage (e.g., plasmid copy number, genomic integration), transcription (e.g., promoter libraries), or translation (e.g., Ribosome Binding Site - RBS libraries) [36].

- Combined and Integrated Approaches: Simultaneously integrating different methods for diversity creation, for example, by refactoring an entire pathway with optimized CDS and expression elements concomitantly [36].

FAQ 3: How can I predict and improve the catalytic efficiency (kcat) of a rate-limiting enzyme? The catalytic turnover number (kcat) is a key parameter for enzyme efficiency. While high-throughput experimental assays for kcat are challenging, several computational methods have been developed [38] [39]:

- Deep Learning Models: Tools like ECEP (Enzyme Catalytic Efficiency Prediction), TurNuP, and DLKcat use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other machine learning algorithms to predict kcat values from enzyme sequences and reaction information [40] [38].

- Constraint-Based Modeling: Approaches like OKO (Overcoming Kinetic rate Obstacles) use enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecGEMs) to predict which enzyme turnover numbers need to be manipulated, and in what direction, to enhance the production of a target compound [39].

- Directed Evolution: This experimental method involves creating mutant enzyme libraries and screening them for improved activity. A high-throughput screening method, such as one using a lycopene indicator, can be employed to select superior variants [41].

FAQ 4: What are the biggest challenges in combinatorial optimization, and how can they be overcome? The main challenge is combinatorial explosion, where the number of permutations increases exponentially with the number of pathway components, making it impossible to test all combinations [36] [37]. Strategies to overcome this include:

- Heuristics and Statistical Methods: Using methods like the Randomized Circular Permutation (RCP) heuristic to sample a representative subset of the library, drastically reducing experimental effort [36].

- Machine Learning (ML): Integrating ML into Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles to model complex bioprocesses, explore the design space efficiently, and guide the optimization process based on accumulated data [40].

- Modular Pathway Engineering: Breaking down a pathway into modules (e.g., upstream and downstream) and optimizing them separately before integrating, simplifying the optimization task [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Troubleshooting Low Product Titer in a Combinatorial Library

Problem: Screening of a combinatorial library for a target metabolic pathway has failed to identify any clones with significantly improved product titer.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Imbalanced upstream module flux | Measure key intermediate metabolites via HPLC or LC-MS. Compare levels between high and low producers. | Apply modular pathway engineering. Use promoter engineering to fine-tune the inter-module balance between upstream and downstream pathways [41]. |

| Inefficient rate-limiting enzymes | Use computational tools (e.g., DLKcat, ECEP) to predict kcat values and identify potential kinetic bottlenecks [38] [39]. | Perform directed co-evolution on suspected rate-limiting enzymes (e.g., DXS, DXR, IDI in the MEP pathway) to create and screen variant libraries with improved activity [41]. |

| Insufficient library diversity | Sequence a random subset of clones to assess the actual genetic diversity (e.g., in promoters or CDS) achieved during library construction. | Employ more diverse genetic parts (e.g., promoter libraries of varying strengths, homologs from metagenomic libraries) during the library construction phase [36]. |

| Toxicity of pathway intermediates/products | Conduct growth curve analysis of library clones. Growth inhibition suggests toxicity. | Implement a biosensor for real-time, high-throughput screening to identify rare clones that maintain high production without toxicity [37]. Introduce export systems or degrade toxic byproducts. |

Guide: Troubleshooting a Combinatorial Library with High Clonal Variability and No Clear Hits

Problem: The screened combinatorial library shows extreme clonal variability in production levels, but no consistent, high-performing clones can be identified.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic burden from excessive resource allocation | Measure the growth rate and plasmid retention rate of high- and low-producing clones. Fast growers with low production may indicate burden. | Switch from plasmid-based to chromosomal integration of pathway genes. Use genome-editing tools (e.g., CRISPR/Cas) for stable, single-copy integration [37]. |

| Unregulated gene expression causing noise | Use single-cell methods (e.g., flow cytometry) to analyze the distribution of a reporter protein (e.g., GFP) across the population. | Replace constitutive promoters with orthogonal regulators or auto-inducible systems (e.g., quorum-sensing, optogenetic) to control expression timing and reduce noise [37]. |

| Poor assembly quality or genetic instability | Re-sequence the pathway in several low and high performers to check for assembly errors, mutations, or rearrangements. | Optimize the DNA assembly protocol. Use stable genomic loci for integration. Employ inducible systems to postpone expression until after biomass accumulation [37]. |

Key Experimental Data and Parameters

The table below summarizes key parameters and solutions used in combinatorial optimization, as evidenced by successful case studies.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Combinatorial Pathway Optimization

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Optimization | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter & RBS Libraries | Provides a range of transcriptional and translational strengths to balance expression levels of multiple genes [36]. | Fine-tuning the inter-module flux between an upstream MEP pathway and a downstream isoprene-forming module [41]. |

| Homologous Enzyme Library | A collection of different enzyme variants (homologs) performing the same function, offering diverse kinetic properties [36]. | Sourcing different homologs for xylose utilization to identify the most effective combination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [36]. |

| Directed Evolution & Co-evolution | A high-throughput method to improve the catalytic efficiency (kcat) and specificity of rate-limiting enzymes [41]. | Directed co-evolution of DXS, DXR, and IDI enzymes in the MEP pathway, leading to a 60% improvement in isoprene production [41]. |

| Whole-Cell Biosensors | Genetically encoded devices that transduce product concentration into a detectable signal (e.g., fluorescence), enabling high-throughput screening [37]. | Rapid screening of large combinatorial libraries for metabolite overproducers using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [37]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Models (e.g., ECEP, DLKcat) | Predicts enzyme kinetic parameters (like kcat) from sequence data, guiding intelligent library design and in silico optimization [40] [38]. | Predicting enzyme turnover numbers to parameterize enzyme-constrained genome-scale models (ecGEMs) for more accurate simulations [40] [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Combinatorial Optimization via Directed Co-evolution and Modular Engineering

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully increased isoprene production in E. coli [41].

1. Objective: To enhance the production of a target compound (e.g., isoprene) by simultaneously optimizing multiple rate-limiting enzymes within a pathway module and balancing the flux between pathway modules.

2. Materials:

- Plasmids: Vectors for gene expression and library construction.

- Host Strain: Engineered E. coli with a base pathway.

- Enzyme Libraries: Mutant libraries for rate-limiting enzymes (e.g., DXS, DXR, IDI for the MEP pathway) generated via error-prone PCR or other mutagenesis methods.

- Screening Indicator: A high-throughput screening method (e.g., a lycopene-based colorimetric assay for MEP pathway activity) [41].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Intra-Module Engineering.

- Clone the mutant libraries of the rate-limiting enzymes (DXS, DXR, IDI) into an expression vector.

- Transform the library into the production host and plate on agar. Use the lycopene indicator to visually screen for colonies with enhanced pathway flux (e.g., deeper red color).

- Isplicate the best-performing clones and quantify product titer (isoprene) in liquid culture to confirm improvement.

- Step 2: Inter-Module Engineering.

- Treat the optimized module from Step 1 as the "upstream module."

- Construct a "downstream module" containing the final converting enzymes (e.g., isoprene synthase).

- Use a library of promoters with different strengths to control the expression of the downstream module.

- Assemble combinations of the optimized upstream module with the variably expressed downstream module.

- Screen the resulting library to identify the optimal balance between upstream flux and downstream conversion capacity.

4. Workflow Diagram:

Protocol: In Silico Optimization of Enzyme Catalytic Rates Using the OKO Framework

This protocol is based on the OKO (Overcoming Kinetic rate Obstacles) constraint-based modeling approach [39].

1. Objective: To computationally predict which native enzyme turnover numbers (kcat) should be modified, and in what direction (increase or decrease), to maximize the production of a target chemical while maintaining cell growth.

2. Materials:

- Software: A constraint-based modeling environment (e.g., COBRApy in Python).

- Model: An Enzyme-Constrained Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (ecGEM) for your host organism (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae) [39].

- Data: Experimentally measured or deep learning-predicted kcat values for enzymes in the model.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Model Construction and Validation.

- Load the ecGEM, which integrates proteomic and kinetic constraints.

- Ensure the wild-type model can simulate known physiological behavior (e.g., growth rate).

- Step 2: Formulate the OKO Problem.

- Set the objective function to maximize the production flux of your target compound.

- Define a constraint to ensure a minimum level of biomass (growth) is maintained.

- Allow the model to manipulate the kcat values of enzymes within a predefined, biologically feasible range, without changing the enzyme abundances from the wild-type state.

- Step 3: Solve and Analyze.

- Run the OKO optimization. The output will be a list of enzymes with suggested new kcat values.

- Key Output: The strategy indicates whether to increase the kcat of a bottleneck enzyme or decrease the kcat of a competing reaction to re-route flux [39].

4. Workflow Diagram:

Advanced Tools & Machine Learning Integration

Modern combinatorial optimization heavily leverages machine learning to navigate complex design spaces. The DBTL cycle is central to this integration.

Table 2: Machine Learning Applications in Pathway Optimization

| ML Application | Role in Optimization | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| kcat Prediction (e.g., ECEP, TurNuP) | Uses ensemble convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and features from enzyme sequences to predict catalytic efficiency [38]. | Provides essential kinetic parameters for ecGEMs and identifies priority targets for enzyme engineering without costly experiments [38] [39]. |

| Active Learning & Bayesian Optimization | Guides the DBTL cycle by selecting the most informative experiments to perform next based on previous data [40]. | Dramatically reduces the number of experimental cycles needed to find an optimal pathway variant [40]. |

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) Refinement | ML algorithms like BoostGAPFILL are used to identify and fill gaps in metabolic networks, improving model quality [40]. | Creates more accurate in silico models for better prediction of metabolic engineering strategies [40]. |

Diagram: The ML-Augmented DBTL Cycle for Pathway Optimization

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our initial catalytic residue substitution (e.g., Glu166 to Tyr in β-lactamase) severely impaired enzyme activity. Is this expected and how should we proceed?

A: Yes, this is an expected intermediate outcome. The primary substitution aims to establish a new proton transfer mechanism but disrupts the optimized native catalytic geometry. You should proceed with directed evolution to restore and optimize function. In the TEM β-lactamase model, the E166Y substitution initially impaired activity, but subsequent directed evolution generated the optimized YR5-2 variant, which achieved a kcat of 870 s⁻¹ at pH 10.0, comparable to wild-type performance at its optimal pH [42] [43]. The key is to treat the initial substitution as a starting point for further optimization rather than a final product.

Q2: How can we experimentally validate that our engineered residue truly functions as the new catalytic general base?

A: A combination of kinetic, structural, and computational approaches is necessary:

- Revertant Analysis: Create revertant mutants (e.g., Y166E in the evolved background) and characterize them kinetically. A significant drop in activity supports the essential role of the new residue [43].

- pH-Rate Profiling: Characterize enzyme activity across a broad pH range. A successful mechanistic shift will manifest as a significant change in the enzyme's optimal pH profile. For example, the YR5-2 variant showed a >3-unit shift in optimal pH towards alkalinity [42].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Use MD simulations to analyze the geometry and dynamics of the active site. Simulations can provide evidence that the newly introduced residue (e.g., Tyr166) is positioned to participate directly in the catalytic proton transfer [42] [43].

Q3: What are the most critical factors to consider when selecting a candidate enzyme and target residue for this reprogramming strategy?

A: The strategy is most applicable to hydrolases and enzymes relying on a general base mechanism. Key selection criteria include:

- Conserved Catalytic Residue: Target a universally conserved catalytic residue (like Glu166 in β-lactamases) to ensure you are modifying a key component of the catalytic machinery [42].

- pKa Differential: Choose a substituting residue (e.g., Tyrosine) with a higher intrinsic pKa than the original residue (e.g., Glutamate) to facilitate the shift in optimal pH towards alkaline conditions [42].

- Structural Context: Ensure the active site has sufficient spatial flexibility to accommodate the structural changes resulting from the substitution and subsequent compensatory mutations identified during directed evolution [44].

Q4: Our engineered enzyme shows improved activity at alkaline pH but suffers from physical instability and aggregation. How can this be mitigated?

A: Protein instability is a common challenge in enzyme engineering.