Bridging Prediction and Experiment: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Flux Balance Analysis with Experimental Flux Measurements

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone constraint-based method for predicting metabolic behavior in systems biology and metabolic engineering.

Bridging Prediction and Experiment: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Flux Balance Analysis with Experimental Flux Measurements

Abstract

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a cornerstone constraint-based method for predicting metabolic behavior in systems biology and metabolic engineering. However, its predictive power hinges on the accuracy of its flux distributions against experimental data. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists on the methods, challenges, and best practices for comparing FBA predictions with experimental flux measurements. We explore the foundational principles of FBA and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), detail advanced methodologies for model integration and improvement, address common pitfalls in model validation, and synthesize frameworks for robust comparative analysis. By consolidating current knowledge and emerging trends, this review aims to enhance the reliability of metabolic models in applications ranging from microbial strain engineering to drug target identification.

Core Principles: Understanding FBA Predictions and Experimental Flux Measurement Techniques

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) stands as a cornerstone computational method in systems biology for predicting metabolic behavior in various organisms. This constraint-based modeling approach leverages genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) to simulate metabolic flux distributions under specific conditions. FBA operates on two fundamental pillars: the steady-state assumption, which posits that metabolite concentrations remain constant over time with production and consumption rates balanced, and the optimality principle, which assumes that metabolic networks evolve to optimize specific cellular objectives, most commonly biomass maximization [1] [2]. The mass balance equation S·v = 0, where S is the stoichiometric matrix and v represents metabolic fluxes, mathematically encapsulates the steady-state condition, while linear programming identifies optimal flux distributions that maximize a defined objective function [2] [3].

Despite its widespread adoption in fields ranging from metabolic engineering to drug discovery, FBA's predictive accuracy fundamentally depends on how well these core assumptions align with biological reality. This publication guide objectively compares FBA's performance against experimental flux measurements and emerging computational alternatives, providing researchers with a structured framework for evaluating method selection in metabolic network analysis.

The Steady-State Assumption: Theoretical Basis and Experimental Validation

The steady-state assumption simplifies the complex dynamics of cellular metabolism by asserting that internal metabolite concentrations do not change over time, creating a mass balance where influx equals efflux for each metabolite. This foundation enables FBA to bypass the need for challenging kinetic parameter measurements and focus solely on reaction stoichiometry and network connectivity [1] [2].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Methodologies for testing the steady-state assumption typically involve comparing FBA predictions with experimental flux measurements under controlled conditions:

Isotopomer Analysis: Researchers utilize isotopic labeling (e.g., 13C-glucose) to trace metabolic fluxes in vivo. After introducing labeled substrates to microbial cultures, mass spectrometry analyzes isotope patterns in intracellular metabolites, providing direct measurements of metabolic reaction rates for comparison with FBA predictions [4].

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA): For systems where steady-state assumptions break down, dFBA couples FBA with extracellular kinetic models. This iterative approach updates environmental constraints at each time step, simulating metabolic shifts in dynamic environments. The implementation involves solving a series of FBA problems where exchange reaction bounds l(t) and u(t) are dynamically adjusted based on metabolite concentrations from previous iterations [2].

Multi-condition Screening: Experimentalists subject organisms to diverse nutrient environments (varying carbon sources, oxygen levels, or nutrient limitations) and measure growth phenotypes and metabolic secretion profiles. These are compared against FBA simulations under identical constraint sets to identify conditions where steady-state predictions hold or fail [3].

Performance Comparison: Steady-State Predictions vs. Experimental Data

Table 1: Accuracy of FBA Steady-State Predictions Across Biological Contexts

| Organism/System | Experimental Method | Conditions Tested | Prediction Accuracy | Key Limitations Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (iML1515 model) | 13C-flux analysis [3] | Glucose minimal medium, aerobic | 85-90% | Fails to predict fluxes through redundant pathways |

| Clostridium acetobutylicum [4] | Isotopomer analysis | Glucose fermentation, solventogenic phase | 72-78% | Poor capture of metabolic shifts between growth phases |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 & L. plantarum co-culture [2] | dFBA vs. static FBA | Simulated gut environment | dFBA: 88-92% Static FBA: 65-70% | Static FBA cannot model cross-feeding dynamics |

| Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells [3] | Gene essentiality screens | Various carbon sources | 75-80% | Lower accuracy in mammalian systems |

The Optimality Principle: Biomass Maximization and Alternatives

The optimality principle in FBA assumes that evolution has shaped metabolic networks to maximize efficiency toward specific biological objectives. While biomass production serves as the default objective function for microbial systems, this assumption may not hold across all biological contexts, particularly in engineered strains or diseased cells [4] [5].

Beyond Biomass: Alternative Objective Functions

Advanced FBA implementations have explored multiple objective functions beyond biomass maximization:

- ATP Maximization: Important in energy-stressed environments or for specific metabolic phases.

- Product Yield Maximization: Relevant for engineered strains in bioprocessing (e.g., L-DOPA production in modified E. coli) [2].

- Weighted Sum of Fluxes: Frameworks like TIObjFind determine Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives, creating weighted combinations of fluxes that better align with experimental data [4].

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Lexicographic approaches that first optimize for biomass, then constrain growth to a percentage of maximum while optimizing for secondary products like L-cysteine export [1].

Experimental Protocols for Objective Function Validation

Gene Essentiality Prediction: The standard protocol involves:

- Creating single-gene deletion mutants using CRISPR-Cas9 or other gene-editing technologies

- Measuring growth rates in controlled environments (e.g., minimal media)

- Comparing experimental essentiality calls with FBA predictions using biomass maximization as the objective

- Calculating accuracy metrics (precision, recall, F1-score) [3] [5]

Product Synthesis Validation: For engineered strains, researchers:

- Introduce heterologous pathways (e.g., HpaBC enzyme for L-DOPA production in E. coli)

- Measure product secretion rates under controlled bioreactor conditions

- Compare with FBA predictions using product synthesis as objective function [2]

Objective Function Identification: The TIObjFind framework employs:

- Collection of experimental flux data (vjexp) under specific conditions

- Optimization formulation that minimizes difference between predicted and experimental fluxes

- Calculation of pathway-specific Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) using minimum-cut algorithms on Mass Flow Graphs [4]

Quantitative Comparison of Objective Functions

Table 2: Performance of Different Objective Functions in FBA

| Objective Function | Biological Context | Experimental Validation Method | Accuracy vs. Experimental Data | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | E. coli core metabolism [5] | Gene essentiality screening | 0% F1-score (failed to identify essential genes) | Simple, widely applicable | Poor handling of biological redundancy |

| Weighted Sum (TIObjFind) [4] | C. acetobutylicum fermentation | Time-resolved metabolomics | 22% reduction in prediction error vs. standard FBA | Captures metabolic shifts | Requires extensive experimental data |

| Lexicographic Optimization [1] | L-cysteine overproduction in E. coli | Product secretion rates | 89% match with experimental yields | Balances growth and production | Requires careful tuning of constraints |

| ATP Maximization | E. coli under energy stress | ATP consumption measurements | 70-75% accuracy | Relevant for energy metabolism | Poor prediction of biomass yield |

Emerging Alternatives to Traditional FBA

Machine Learning-Enhanced Approaches

Recent advances integrate machine learning with constraint-based modeling to overcome FBA's limitations:

Flux Cone Learning (FCL): This framework combines Monte Carlo sampling of metabolic spaces with supervised learning. The protocol involves:

- Generating numerous random flux samples from the metabolic space of wild-type and mutant strains

- Training random forest classifiers on geometric features of these flux cones

- Predicting gene essentiality without optimality assumptions

- Achieving 95% accuracy in E. coli, outperforming FBA's 93.5% [3]

Topology-Based Machine Learning: This "structure-first" approach:

- Constructs reaction-reaction graphs from metabolic models

- Computes graph-theoretic features (betweenness centrality, PageRank)

- Trains classifiers exclusively on topological features

- Demonstrates F1-score of 0.400 vs. 0.000 for FBA on E. coli core metabolism [5]

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 3: FBA vs. Alternative Methods in Metabolic Phenotype Prediction

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Dependency on Optimality Assumption | Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard FBA [1] [2] | Constraint-based optimization, linear programming | Complete dependency | 93.5% (E. coli), declines in complex systems | Low |

| Dynamic FBA (dFBA) [2] | FBA coupled with ODEs for extracellular environment | Partial dependency | 88-92% in dynamic co-culture systems | Moderate to High |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [3] | Monte Carlo sampling + machine learning | No dependency | 95% (E. coli), maintains accuracy across organisms | High |

| Topology-Based ML [5] | Graph theory + machine learning | No dependency | F1-score: 0.400 (E. coli core) | Moderate |

| TIObjFind [4] | Pathway analysis + multi-objective optimization | Modified (weighted objectives) | 22% error reduction over FBA | Moderate |

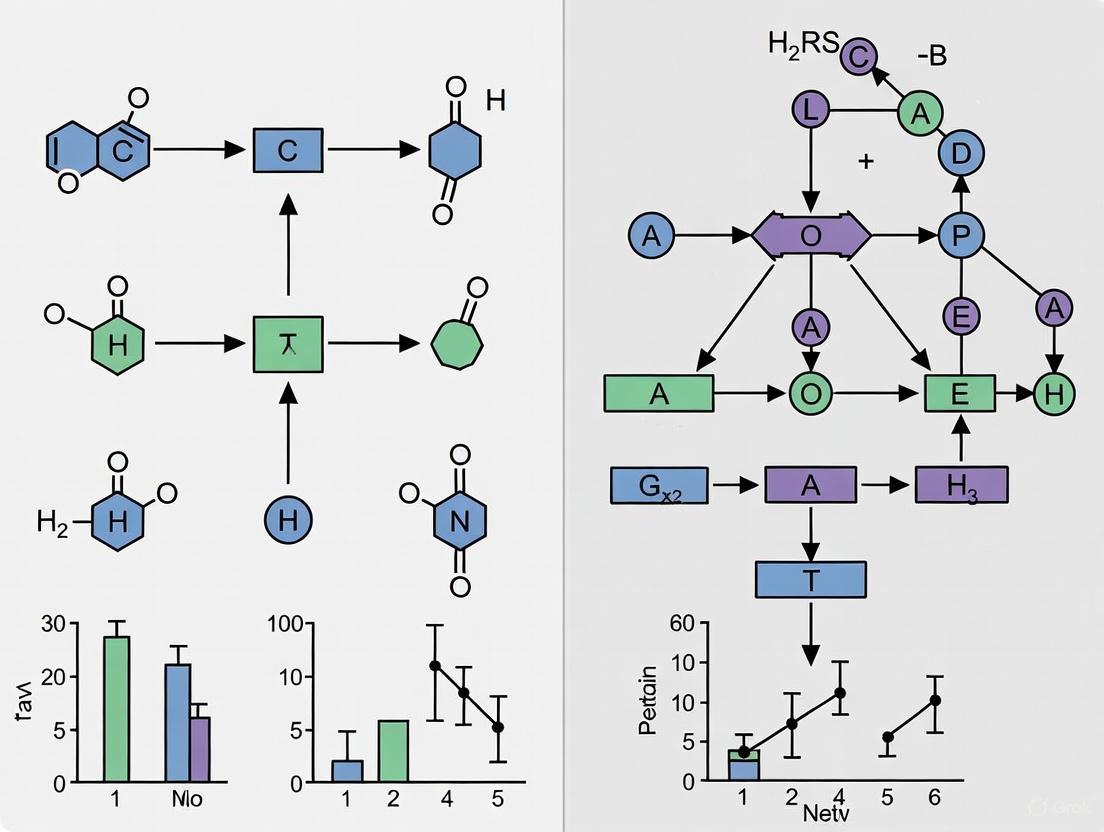

Visualizing Methodologies and Metabolic Pathways

FBA Workflow and Core Assumptions

FBA Core Methodology: This diagram illustrates the standard FBA workflow where genome-scale metabolic models combine with steady-state and optimality assumptions to generate flux predictions through linear programming, with subsequent experimental validation potentially informing objective function refinement.

TIObjFind Framework for Objective Function Identification

TIObjFind Framework: The TIObjFind methodology integrates experimental flux data with metabolic pathway analysis to determine pathway-specific Coefficients of Importance, which serve as weights in objective functions to improve alignment between predictions and experimental observations.

Flux Cone Learning Methodology

Flux Cone Learning Approach: Flux Cone Learning uses Monte Carlo sampling to characterize the geometry of metabolic spaces, which combined with experimental fitness data trains machine learning models to predict metabolic phenotypes without optimality assumptions.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Relevance to FBA Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | iML1515 (E. coli) [1] [3], iDK1463 (E. coli Nissle 1917) [2], L. plantarum model [2] | Provide stoichiometric representation of metabolic network | Foundation for all FBA simulations; model quality directly impacts prediction accuracy |

| Software Packages | COBRApy [1] [2], MATLAB with maxflow package [4], ECMpy [1] | Implement FBA, dFBA, and enzyme constraint algorithms | Enable simulation of metabolic networks with customizable constraints and objective functions |

| Experimental Validation Databases | BRENDA [1], PAXdb [1], PEC database [5] | Provide enzyme kinetics, protein abundance, and gene essentiality data | Offer ground-truth data for benchmarking FBA predictions |

| Isotopic Labeling Reagents | 13C-glucose, 15N-ammonia | Enable experimental flux measurement via isotopomer analysis | Generate experimental flux maps for comparison with FBA predictions |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 [3] | Create gene deletion mutants for essentiality testing | Enable experimental validation of gene essentiality predictions |

| Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn [5], NetworkX [5] | Implement classifiers and network analysis for advanced methods | Support development of ML-enhanced flux prediction approaches |

The foundational assumptions of Flux Balance Analysis—steady-state metabolism and cellular optimality—provide powerful simplifying constraints that enable metabolic modeling at genome scale. However, systematic comparison with experimental flux measurements reveals significant limitations in biological contexts where these assumptions break down, particularly when modeling metabolic shifts, complex organisms, or redundant networks. Emerging methodologies that integrate pathway analysis, machine learning, and topological features demonstrate quantifiable improvements in predictive accuracy while reducing dependency on strict optimality principles. The continued development of hybrid approaches that leverage both mechanistic modeling and data-driven inference represents the most promising path forward for accurate metabolic phenotype prediction in both basic research and applied biotechnology.

Quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes is essential for understanding cell physiology in metabolic engineering, systems biology, and biomedical research [6]. Metabolic fluxes represent the integrated functional phenotype of a cell, emerging from multiple layers of biological regulation including the genome, transcriptome, and proteome [7]. However, in vivo fluxes cannot be measured directly, necessitating computational approaches for estimation [7]. Two primary constraint-based modeling frameworks have emerged: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which predicts fluxes using optimization of biological objectives, and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), which determines fluxes by integrating experimental isotopic labeling data [7]. While FBA enables rapid analysis of genome-scale networks, 13C-MFA provides experimental validation and is considered the gold standard for quantifying accurate intracellular fluxes in central carbon metabolism [6] [8]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these methodologies, highlighting why 13C-MFA remains the benchmark for experimental flux measurement.

Methodological Comparison: 13C-MFA vs. Flux Balance Analysis

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Table 1: Core methodological differences between 13C-MFA and FBA.

| Feature | 13C-MFA | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Model-based interpretation of experimental isotopic labeling data [8] | Linear optimization based on stoichiometric constraints and assumed biological objectives [7] |

| Key Data Inputs | Isotopic labeling patterns (MS/NMR), extracellular fluxes, metabolic network model [6] [8] | Stoichiometric model, measured exchange fluxes, objective function (e.g., growth maximization) [7] |

| Flux Determination | Least-squares regression minimizing difference between measured and simulated labeling data [8] | Identification of flux distribution that optimizes a pre-defined objective function [7] [9] |

| Primary Output | Quantitative map of intracellular fluxes with confidence intervals [8] | Predicted flux distribution(s) representing optimal network states [7] |

| Typical Network Scope | Core metabolic networks (e.g., central carbon metabolism) [8] | Genome-scale metabolic models [7] |

| Key Strength | High accuracy and precision for quantified fluxes; model validation via goodness-of-fit [7] [6] | Computational tractability for large networks; no requirement for experimental labeling data [7] |

Quantitative Performance and Validation

Table 2: Comparative performance of 13C-MFA and FBA in flux determination.

| Aspect | 13C-MFA | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) |

|---|---|---|

| Flux Resolution | Can accurately determine fluxes of metabolic cycles, parallel pathways, and reversible reactions [6] | Limited resolution for parallel pathways and cycles without additional constraints [7] |

| Experimental Validation | Internal consistency validated via χ²-test of goodness-of-fit and flux confidence intervals [7] [6] | Validation requires comparison against external experimental data, often from 13C-MFA [7] |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Provides confidence intervals for all estimated fluxes [7] [6] | Solution space characterization possible (e.g., Flux Variability Analysis), but not standard [7] |

| Objective Function | No biological objective required; fit to experimental data drives solution [9] | Highly dependent on choice of objective function (e.g., growth yield, ATP maximization) [7] [9] |

| Tracer Experiment Requirement | Mandatory (adds cost and complexity) [8] | Not required [7] |

The 13C-MFA Experimental Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for a 13C-MFA study, from experimental design to flux validation.

Figure 1: The 13C-MFA workflow integrates precise experimentation with robust computational analysis to generate validated flux maps.

Experimental Protocol and Best Practices

Tracer Selection and Experiment Design: Choose 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glutamine) that generate distinct labeling patterns in the pathways of interest [8]. The design should include rationale for tracer selection and a complete description of culture conditions, including when tracers were added and samples collected [6].

Isotopic Steady-State Achievement: Culture cells until metabolic and isotopic steady-state is reached, where metabolite concentrations, fluxes, and isotopic labeling are constant [10]. For mammalian cells, this typically requires 24-72 hours of labeling, verified by consistent labeling patterns over time [8].

Extracellular Flux Measurement: Precisely quantify nutrient uptake and product secretion rates, along with growth rates, to provide boundary constraints for the model [8]. These external fluxes are calculated from changes in metabolite concentrations and cell numbers during the experiment [8].

Isotopic Labeling Analysis: Quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites. Analyze mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) using mass spectrometry (GC-MS, LC-MS) or NMR [6] [8]. Report uncorrected mass isotopomer distributions with standard deviations [6].

Computational Flux Analysis: Input the labeling data, external fluxes, and metabolic network model into 13C-MFA software (e.g., INCA, Metran) [8]. The software estimates fluxes by minimizing the difference between measured and simulated labeling patterns using least-squares regression [8].

Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and software tools for 13C-MFA.

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glutamine | Create distinct isotopic labeling patterns to elucidate pathway activities [8] [10] |

| Analytical Instruments | GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, NMR | Quantify mass isotopomer distributions or positional isotopomers in metabolites [6] [8] [10] |

| Cell Culture Materials | Defined culture media, Bioreactors, Metabolite assays | Maintain controlled culture conditions and measure extracellular metabolite concentrations [11] [8] |

| Software Platforms | INCA, Metran, Iso2Flux, p13CMFA | Perform flux estimation, confidence interval analysis, and statistical validation [8] [9] |

| Metabolic Models | Curated network reconstructions (e.g., core metabolism) | Provide stoichiometric and atom mapping framework for flux estimation [6] |

Advanced Methodological Developments

The field of 13C-MFA continues to evolve with several innovative approaches enhancing its capabilities:

Parsimonious 13C-MFA (p13CMFA): This approach applies flux minimization as a secondary optimization criterion after fitting isotopic labeling data, helping to identify optimal flux distributions when the solution space is large [9]. It can also integrate gene expression data by weighting the minimization of fluxes through lowly expressed enzymes [9].

Bayesian 13C-MFA: Bayesian methods provide a framework for unified treatment of data and model selection uncertainty, enabling multi-model flux inference that is more robust than single-model approaches [12]. Bayesian Model Averaging helps address model selection uncertainty by assigning probabilities to competing models [12].

Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA): This method analyzes isotopic labeling before it reaches steady state, significantly reducing the required experiment time and enabling flux analysis in systems where prolonged steady-state culture is challenging [10].

Global 13C Tracing: Recent approaches use highly 13C-enriched medium with multiple fully-labeled nutrients to simultaneously assess a wide range of metabolic pathways in a single experiment, enabling unbiased discovery of metabolic activities [13].

13C-MFA remains the experimental gold standard for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes due to its foundation in empirical isotopic labeling data, rigorous statistical validation, and ability to resolve complex metabolic network functions. While FBA provides valuable insights for genome-scale modeling and hypothesis generation, its predictions require experimental validation, often through comparison with 13C-MFA results [7]. The continued development of more sophisticated 13C-MFA methodologies ensures its ongoing critical role in metabolic engineering, biotechnology, and understanding the metabolic basis of disease.

Accurately evaluating the agreement between Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) predictions and experimental data is a critical step in metabolic model validation. This guide details the key quantitative metrics, statistical tests, and experimental methodologies used by researchers to benchmark and improve the predictive power of constraint-based models.

Quantitative Metrics for Statistical Agreement

The table below summarizes the core metrics and statistical tests used to quantify the agreement between FBA-predicted fluxes and experimental measurements.

| Metric / Test | Application | Interpretation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squared Deviations [4] | Minimizing difference between predicted ((vj^*)) and experimental ((vj^{exp})) fluxes. | Lower values indicate better fit. Central to optimization frameworks like ObjFind and TIObjFind. | Sensitive to outliers; requires experimental flux data (e.g., from isotopomer analysis) [4]. |

| χ2-test of Goodness-of-Fit [14] | Validating 13C-MFA flux maps against experimental Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) data. | A statistically non-significant result (p > 0.05) suggests the model is consistent with the data. | Most widely used quantitative validation in 13C-MFA; checks if residuals are within expected experimental error [14]. |

| Flux Uncertainty Estimation [14] | Quantifying confidence intervals for estimated fluxes in 13C-MFA. | Narrower confidence intervals indicate more precise and reliable flux estimates. | Advanced methods allow researchers to gather additional data to support conclusions [14]. |

| Growth/No-Growth Comparison [14] | Qualitative validation of FBA model functionality on different substrates. | Tests the presence or absence of metabolic routes essential for growth. | Only indicates viability; does not test accuracy of internal flux values or growth efficiency [14]. |

| Growth-Rate Comparison [14] | Quantitative validation of the efficiency of substrate-to-biomass conversion. | Compares predicted vs. observed growth rates across multiple conditions. | Informative for overall network efficiency but uninformative about internal flux accuracy [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Flux Validation

A variety of experimental protocols are employed to generate the data required for the metrics listed above. The methodologies for three key techniques are detailed below.

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

- Purpose: To estimate intracellular fluxes by tracing the path of labeled atoms through the metabolic network [14].

- Workflow:

- Tracer Application: Feed 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose) to the biological system [14].

- Labeling Measurement: After the system reaches isotopic steady state, harvest cells and use mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to measure the labeling patterns (Mass Isotopomer Distributions, MIDs) of intracellular metabolites [14].

- Computational Fitting: Use computational software to find the flux map that minimizes the residuals between the measured MIDs and the MIDs simulated by the model [14].

- Advanced Application: Parallel Labeling Experiments use multiple different tracers simultaneously to generate a single, more precise set of flux estimates, constraining the model more effectively than single-tracer experiments [14].

The TIObjFind Framework

- Purpose: A novel optimization framework that integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to identify context-specific metabolic objective functions and improve flux predictions [4] [15].

- Workflow:

- Optimization: Reformulates objective function selection as a problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [4] [15].

- Graph Construction: Maps FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), a directed, weighted graph representing metabolic flux distributions [4].

- Pathway Analysis: Applies a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). These coefficients quantify each reaction's contribution to the cellular objective [4] [15].

- Outcome: The CoIs serve as pathway-specific weights in the objective function, aligning FBA predictions with experimental data and revealing shifting metabolic priorities under different conditions [4].

ΔFBA (deltaFBA)

- Purpose: To directly predict metabolic flux differences between two conditions (e.g., perturbation vs. control) without requiring a pre-defined cellular objective function [16].

- Workflow:

- Input: A genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) and differential gene expression data between two conditions [16].

- Model Formulation: A constrained Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem is established. The core constraint is that the flux difference (( \Delta v = v^P - v^C )) must satisfy the steady-state assumption: ( S \Delta v = 0 ) [16].

- Optimization Goal: The model maximizes the consistency (and minimizes the inconsistency) between the predicted flux alterations (( \Delta v )) and the observed differential gene expression [16].

Diagram of the multi-faceted workflow for validating FBA models against various types of experimental data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful validation requires a combination of computational tools and experimental reagents. The following table lists essential components of the flux validation pipeline.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Use Case in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates [14] | Chemically synthesized nutrients with carbon atoms in the form of the 13C isotope. | Fed to cells to trace metabolic activity in 13C-MFA and INST-MFA experiments. |

| COBRA Toolbox [16] [14] | A MATLAB-based software suite for constraint-based modeling. | Widely used to perform FBA, test model quality, and implement algorithms like ΔFBA. |

| Mass Spectrometer (MS) [14] | An analytical instrument that measures the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. | Used to detect and quantify the labeling patterns of metabolites in 13C-MFA. |

| MEMOTE Suite [14] | A python-based tool for standardized quality assurance of genome-scale metabolic models. | Automates tests for model stoichiometry, mass/charge balance, and basic biological functions. |

| Stable Isotope Analysis Software (e.g., for 13C-MFA) | Computational platforms designed to fit flux maps to isotopic labeling data. | Essential for converting raw MS/NMR data into quantitative flux estimates for comparison with FBA. |

The Critical Role of Objective Functions in FBA Predictions

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a cornerstone computational method in systems biology for predicting metabolic fluxes within biological systems. As a constraint-based modeling approach, FBA relies on the stoichiometry of metabolic networks to predict flow distributions of metabolites through biochemical reactions. The fundamental principle involves solving for a flux distribution that satisfies mass-balance constraints while optimizing a predefined cellular objective [17]. However, the accuracy of FBA predictions critically depends on selecting an appropriate objective function, which mathematically represents the presumed metabolic goal of the cell under specific conditions [4] [18]. This selection presents a significant challenge, as inappropriate objective functions can lead to substantial discrepancies between predicted and experimentally observed fluxes, potentially limiting the predictive power and practical utility of FBA in metabolic engineering and drug development [19] [18].

The central hypothesis driving recent methodological innovations posits that no single universal objective function can accurately capture cellular behavior across all environmental and genetic contexts. Biological systems dynamically adjust their metabolic priorities in response to changing conditions, nutrient availability, and genetic perturbations [4]. This adaptive capability necessitates the development of more sophisticated, context-aware frameworks for objective function selection and refinement. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of emerging methodologies designed to address this fundamental challenge, evaluating their performance against experimental flux measurements and outlining standardized protocols for implementation.

Quantitative Comparison of FBA Prediction Accuracy Across Methods

The accuracy of FBA predictions is quantitatively assessed by comparing computed flux distributions against experimentally determined fluxes, typically obtained through 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) [19] [20]. 13C-MFA is considered the gold standard for experimental flux quantification, utilizing isotopic tracers and mass spectrometry to measure in vivo metabolic fluxes [21] [20]. The table below summarizes the performance of various FBA approaches against 13C-MFA validation data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of FBA Methodologies Against Experimental Flux Measurements

| Methodology | Key Innovation | Reported Error vs. 13C-MFA* | Computational Demand | Experimental Data Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard FBA | Single objective (e.g., biomass maximization) | Not quantified (Known to be high) | Low | Minimal |

| Parsimonious FBA (pFBA) | Minimizes total flux while achieving biomass production | 94%-180% [19] | Low | Minimal |

| Gene Expression-Weighted FBA | Incorporates relative gene expression as penalty weights | 9%-13% [19] | Medium | Transcriptomic/proteomic data |

| TIObjFind Framework | Infers objective from data using topology and Coefficients of Importance | Demonstrates improved alignment; specific error not quantified [4] | High | Experimental flux data for training |

| Neural-Mechanistic Hybrid | Machine learning layer predicts uptake fluxes from medium composition | Outperforms standard FBA; requires smaller training sets [18] | High (during training) | Medium-specific flux data |

*Error measured as Weighted Average Percent Error between predicted and MFA-measured fluxes.

The quantitative data reveals that methods integrating additional biological data, particularly gene expression information, achieve remarkable improvements in predictive accuracy. The gene expression-weighted approach reduced error from 94%-180% to 9%-13% in Arabidopsis thaliana models, demonstrating the critical value of incorporating molecular context into constraint-based models [19]. This performance enhancement comes with increased computational demands and requires additional experimental data, creating practical trade-offs for researchers when selecting methodologies.

TIObjFind: A Topology-Informed Approach

The TIObjFind framework addresses objective function selection by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with traditional FBA to systematically infer metabolic objectives from experimental data [4]. This method introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each metabolic reaction's contribution to the overall objective function. The framework operates through three key steps: (1) formulating objective selection as an optimization problem that minimizes differences between predicted and experimental fluxes; (2) mapping FBA solutions onto a Mass Flow Graph for pathway-based interpretation; and (3) applying minimum-cut algorithms to extract critical pathways and compute CoIs [4]. By focusing on specific pathways rather than the entire network, TIObjFind enhances interpretability and captures metabolic flexibility under changing environmental conditions.

Neural-Mechanistic Hybrid Models

A groundbreaking approach embeds FBA within artificial neural networks (ANNs) to create hybrid models that leverage both mechanistic understanding and machine learning capabilities [18]. These Artificial Metabolic Networks (AMNs) replace traditional simplex solvers with differentiable alternatives, enabling gradient backpropagation and direct training on experimental flux data [18]. The neural component learns to predict appropriate uptake flux bounds from medium composition, effectively capturing complex transporter kinetics and regulatory effects that are difficult to model mechanistically. This approach demonstrates superior predictive performance with training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than conventional machine learning methods, effectively bridging the gap between pure mechanistic modeling and data-driven approaches [18].

Gene Expression-Integrated FBA

This methodology enhances standard FBA by incorporating relative expression levels between tissues or conditions as penalty weights in the optimization objective [19]. The core assumption is that reactions catalyzed by highly expressed enzymes are more likely to carry higher flux. Mathematically, this is implemented by modifying the pFBA objective function to include expression-derived coefficients:

Reactions associated with highly expressed genes receive lower penalty coefficients (cj), making them more likely to carry flux in the optimal solution [19]. This approach has demonstrated dramatic improvements in prediction accuracy for multi-tissue systems, particularly in plant metabolic models.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

13C-MFA stands as the gold standard validation method for comparing and refining FBA predictions [21] [20]. The standard workflow involves:

- Tracer Preparation: Culturing cells on specifically 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [U-13C]glucose). The choice of tracer position (uniform vs. position-specific labeling) depends on the metabolic pathways of interest [21] [20].

- Isotopic Steady-State Achievement: Maintaining cells in exponential growth until isotopic enrichment reaches steady state in intracellular metabolites [21].

- Metabolite Extraction: Rapid quenching of metabolism (e.g., cold methanol) followed by metabolite extraction from cells [21] [22].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of intracellular metabolites using LC-MS or GC-MS [21] [20].

- Computational Flux Estimation: Using specialized software (e.g., 13CFLUX2, INCA) to estimate metabolic fluxes that best reproduce the experimental MIDs through iterative model fitting [21] [20].

Diagram: 13C-MFA Workflow for Experimental Flux Validation

Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA)

For systems where achieving isotopic steady state is impractical or where flux dynamics are of interest, INST-MFA provides an alternative approach [21]. This method measures isotopic labeling patterns at multiple time points during the transition to steady state and uses ordinary differential equations to model the temporal evolution of labeling patterns [21]. INST-MFA is particularly valuable for studying systems with slow labeling dynamics or transient metabolic states, though it requires more intensive computational resources and more sophisticated experimental design.

Visual Guide to Advanced FBA Frameworks

Diagram: Architecture of Advanced FBA Frameworks for Objective Function Selection

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA Validation

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1,2-13C]Glucose | Isotopic Tracer | Enables precise tracing of carbon fate through metabolic networks | 13C-MFA for central carbon metabolism validation [21] [20] |

| [U-13C]Glucose | Isotopic Tracer | Uniform labeling for comprehensive flux mapping | Broad-coverage 13C-MFA studies [21] |

| 13CFLUX2 | Software Package | Flux estimation from 13C labeling data | Isotopically stationary MFA [21] |

| INCA | Software Platform | Comprehensive flux analysis | INST-MFA and metabolic modeling [21] |

| Cobrapy | Python Package | Constraint-based modeling | FBA implementation and simulation [18] |

| MATLAB maxflow | Algorithm Package | Minimum cut/maximum flow computation | TIObjFind pathway analysis [4] |

| LC-MS/MS System | Analytical Instrument | Measures metabolite concentrations and labeling patterns | Experimental fluxomics [21] [23] |

| GC-MS System | Analytical Instrument | Determines mass isotopomer distributions | 13C-MFA with volatile compounds [21] [23] |

Successful implementation of advanced FBA methodologies requires both wet-lab reagents for experimental validation and computational tools for model development and simulation. Isotopic tracers form the foundation of experimental flux validation, with different labeling patterns (position-specific vs. uniform) offering distinct advantages for elucidating specific pathway activities [21] [20]. Computational resources range from specialized flux estimation software to general-purpose constraint-based modeling packages, each serving critical functions in the model development and validation pipeline.

The critical role of objective functions in FBA predictions necessitates a paradigm shift from static, assumption-driven approaches to dynamic, data-informed methodologies. Frameworks such as TIObjFind, neural-mechanistic hybrids, and expression-weighted FBA represent significant advances in aligning computational predictions with biological reality. Quantitative comparisons demonstrate that methods integrating additional biological data layers—including transcriptomics, proteomics, and experimental flux measurements—can achieve order-of-magnitude improvements in predictive accuracy [4] [19] [18].

Future developments will likely focus on multi-omic integration, combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data within unified modeling frameworks. Additionally, the growing availability of experimental flux data across diverse organisms and conditions will enable more robust benchmarking and validation of novel methodologies. As these approaches mature, they will increasingly empower researchers in metabolic engineering and drug development to make precise, predictive manipulations of biological systems, ultimately accelerating the design of optimized microbial strains and targeted therapeutic interventions.

Limitations and Inherent Uncertainties in Both Computational and Experimental Approaches

Metabolic flux analysis represents an essential perspective for understanding cellular physiology, offering quantitative information on the flow of metabolites through biochemical networks that is crucial for both basic research and applied biotechnology [24]. Researchers and drug development professionals primarily utilize two complementary approaches to quantify these metabolic fluxes: computational methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) that model metabolism mathematically, and experimental techniques that measure flux distributions directly in biological systems. While FBA employs optimization principles to predict flux distributions through metabolic networks at genome-scale, experimental methods like dynamic flux analysis utilize kinetic isotope labeling and mass spectrometry to empirically determine these flow rates [24] [1].

The central challenge in metabolic research lies in reconciling the predictions from computational models with measurements from experimental assays, as both approaches contain inherent limitations and uncertainties. Computational models often struggle to accurately capture the complex regulatory mechanisms of living cells, while experimental techniques face methodological constraints in precision and scope. This article provides a systematic comparison of these limitations, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies and interpreting contradictory results in metabolic flux studies, particularly in pharmaceutical development contexts where accurate metabolic models can accelerate drug discovery and toxicity assessment [4].

Computational Limitations in Flux Balance Analysis

Fundamental Methodological Constraints

Flux Balance Analysis operates on several simplifying assumptions that introduce uncertainty into its predictions. The core FBA approach uses stoichiometric matrices representing all known metabolic reactions in an organism and applies constraint-based modeling to predict flux distributions that optimize a specified cellular objective [1]. This methodology faces three primary limitations:

Steady-state assumption: FBA assumes metabolic concentrations remain constant over time, ignoring transient dynamics and metabolic regulation that occur in living systems [1]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when modeling engineered biological systems that inherently depend on time-dependent processes, such as gradually accumulating metabolites that trigger genetic circuits.

Objective function selection: The accuracy of FBA predictions heavily depends on selecting an appropriate metabolic objective function [4]. Common objectives like biomass maximization may not always align with observed experimental flux data, particularly under changing environmental conditions or in non-model organisms where cellular priorities are poorly understood [4] [3].

Network completeness and curation: Gaps in metabolic network knowledge directly impact prediction accuracy. For instance, the well-curated iML1515 model of E. coli was found to lack critical pathways for thiosulfate assimilation and conversion to L-cysteine, requiring manual gap-filling to improve biological relevance [1].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Computational Flux Prediction Methods

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Predictions |

|---|---|---|

| Model Structure | Incomplete GPR relationships and reaction directions | Incorrect flux distribution through pathways [1] |

| Parameterization | Unconstrained transport reactions due to missing Kcat values | Overestimation of metabolite export capabilities [1] |

| Condition Specificity | Failure to capture metabolic adaptive shifts | Poor alignment with experimental data across conditions [4] |

| Organism Complexity | Unknown objective functions in higher-order organisms | Reduced predictive power for gene essentiality [3] |

The reliance on stoichiometric coefficients without kinetic parameters presents another fundamental constraint. FBA often predicts unrealistically high fluxes because the solution space is constrained only by reaction stoichiometry and bounds, not by enzyme availability or catalytic efficiency [1]. Incorporating enzyme constraints based on abundance and turnover numbers (Kcat values) partially addresses this limitation but introduces new uncertainties regarding the accuracy of these biological parameters, particularly for transport reactions and non-native enzymatic activities [1].

For drug discovery applications, a significant limitation emerges in FBA's variable predictive accuracy across different organisms. While FBA predicts metabolic gene essentiality in E. coli with approximately 93.5% accuracy, its performance drops substantially for higher-order organisms where optimality objectives are unknown or non-existent [3]. This has direct implications for antimicrobial development where species-specific metabolic models are essential for identifying potential drug targets.

Experimental Uncertainties in Flux Measurement Techniques

Methodological Variability in Flux Quantification

Experimental flux quantification faces distinct challenges across its measurement methodologies. Research comparing different experimental approaches has revealed significant methodological uncertainties:

Dynamic Flux Analysis: This experimental approach estimates flow rates through metabolic pathways using kinetic isotope labeling experiments, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), and computational analysis relating kinetic isotope trajectories to pathway activity [24]. While powerful, this technique faces uncertainties in label incorporation rates, metabolite quenching efficiency, and mass spectrometry signal interpretation.

Gas Exchange Methods: Studies of mercury flux measurement techniques reveal analogous methodological challenges relevant to metabolic research. The Dynamic Flux Chamber (DFC) method, similar in principle to approaches used in metabolic studies, faces issues from chamber-induced environmental perturbations including temperature artifacts, humidity effects, gas diffusion limitations, and altered solar radiation/simulation conditions [25].

Model-Based Methods: Techniques relying on gas exchange models based on two-film theory suffer from parameterization biases including problematic transfer coefficients and simplified assumptions regarding complex interfacial processes [25]. Recent studies suggest that chemical disproportionation during analysis may artificially overestimate dissolved concentrations, leading to inaccurate flux assessments.

Comparative Methodological Uncertainties

Table 2: Experimental Flux Measurement Techniques and Their Uncertainties

| Methodology | Primary Uncertainty Sources | Measurement Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Flux Analysis | Labeling kinetics, quenching efficiency, MS signal interpretation | Quantitative accuracy of absolute flux rates [24] |

| Gas Exchange Models | Parameterization biases, simplified interfacial assumptions | Direction and magnitude of net flux [25] |

| Micrometeorological Methods | Atmospheric stability requirements, complex instrumentation | Applicability to different experimental systems [25] |

| Isotopomer Analysis | Required for experimental vjexp determination | Resource-intensive data requirements [4] |

Experimental techniques for multi-organ fluxomics reveal additional complexities when measuring metabolic adaptations across different tissues. Simultaneous in vivo measurements in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle during obesity demonstrate divergent metabolic adaptations that would be obscured by single-tissue analysis [26]. This highlights the uncertainty introduced by measurement scope limitations, where focusing on a single compartment or tissue type may yield incomplete flux pictures.

A critical methodological uncertainty stems from the potential disconnect between enzyme abundance and actual metabolic flux. While omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) provide valuable insights into metabolic potential, studies show that machine learning models using these data still produce prediction errors compared to actual flux measurements [27]. This indicates that post-translational regulation and allosteric control introduce uncertainties when inferring fluxes from static molecular abundance data.

Comparative Analysis: Computational Predictions versus Experimental Measurements

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

Direct comparisons between computational predictions and experimental measurements reveal substantial discrepancies. Machine learning approaches that integrate transcriptomics and/or proteomics data with FBA show promise for reducing prediction errors, yet still cannot fully reconcile the gap between modeling and measurement [27].

The novel Flux Cone Learning (FCL) framework demonstrates how machine learning can leverage both mechanistic models and experimental data to improve predictions. FCL utilizes Monte Carlo sampling of the metabolic flux space defined by genome-scale models, then applies supervised learning to correlate flux cone geometry with experimental fitness data [3]. This approach achieves 95% accuracy in predicting metabolic gene essentiality in E. coli, outperforming traditional FBA predictions by 1.5% overall, with a 6% improvement specifically for essential gene identification [3].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Flux Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy (E. coli) | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional FBA | 93.5% | Genome-scale coverage, biochemical basis | Requires predefined objective function [3] |

| Parsimonious FBA | Varies by condition | Reduces solution space | Still requires objective function [27] |

| Flux Cone Learning | 95% | No optimality assumption needed | Computationally intensive sampling [3] |

| Omics-based ML | Smaller errors than pFBA | Integrates multiple data types | Limited by omics data quality [27] |

Framework Integration Approaches

Hybrid frameworks that integrate computational and experimental approaches show promise for overcoming the limitations of either method alone. The TIObjFind framework imposes Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to analyze adaptive shifts in cellular responses across different biological system stages [4]. This methodology determines Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to an objective function, aligning optimization results with experimental flux data [4].

The ObjFind framework further addresses the objective function selection problem by introducing Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each flux's additive contribution to a chosen objective function, aiming to align model predictions with observed experimental flux data [4]. By maximizing a weighted sum of fluxes with coefficients while minimizing the sum of squared deviations from experimental data, this approach enables interpretation of experimental fluxes in terms of optimized metabolic objectives.

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Flux Analysis

Detailed methodology for kinetic flux profiling [24]:

System Preparation: Culture microbial cells under controlled conditions. For cyanobacterial examples, maintain precise light, temperature, and CO₂ levels.

Isotope Labeling: Introduce ¹³C-labeled substrates (typically glucose or bicarbonate) at time zero. Use rapid mixing to ensure uniform labeling initiation.

Time-course Sampling: Extract samples at precise intervals (seconds to minutes) using rapid quenching methods (e.g., cold methanol) to instantly halt metabolism.

Metabolite Extraction: Implement LC-MS compatible extraction using methanol/water or chloroform/methanol/water mixtures.

LC-MS Analysis: Separate metabolites via liquid chromatography followed by mass spectrometry detection. Use appropriate columns for polar metabolites (e.g., HILIC).

Data Processing: Extract ion chromatograms for metabolite fragments and correct for natural isotope abundance.

Flux Calculation: Fit kinetic labeling patterns to metabolic network models using computational analysis that relates isotope trajectories to pathway activity.

Computational Protocol: Enzyme-Constrained FBA

Workflow for incorporating enzyme constraints into FBA [1]:

Base Model Preparation: Start with a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iML1515 for E. coli). Update Gene-Protein-Reaction associations based on EcoCyc database.

Reaction Processing: Split reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions to assign distinct Kcat values. Separate isoenzyme reactions into independent reactions.

Parameter Assignment:

- Obtain molecular weights from protein subunit composition

- Set protein mass fraction (typically 0.56 for E. coli)

- Acquire enzyme abundance data from PAXdb

- Gather Kcat values from BRENDA database

Constraint Implementation: Incorporate enzyme constraints using the ECMpy workflow without altering the stoichiometric matrix.

Model Optimization: Perform lexicographic optimization, first for biomass then for target production (e.g., L-cysteine export).

Research Reagent Solutions for Flux Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Computational and Experimental Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ¹³C-labeled substrates | Isotope tracing for experimental flux determination | Dynamic flux analysis [24] |

| LC-MS systems | Quantitative detection of metabolite concentrations and labeling | Metabolomics and fluxomics [24] |

| Genome-scale models | Metabolic network representation for computational predictions | FBA and variant methodologies [1] [3] |

| BRENDA database | Enzyme kinetic parameters (Kcat values) | Enzyme-constrained modeling [1] |

| PAXdb | Protein abundance data | Proteome-informed flux constraints [1] |

| EcoCyc database | Curated metabolic pathway information | GEM reconciliation and validation [1] |

Visualizing Metabolic Flux Analysis Frameworks

The comparison between computational and experimental approaches to flux analysis reveals a landscape of complementary strengths and limitations. Computational methods like FBA provide genome-scale coverage and mechanistic insights but struggle with objective function selection and biological realism. Experimental techniques offer direct measurements but face methodological artifacts and resource intensiveness. The most promising developments, including TIObjFind, Flux Cone Learning, and enzyme-constrained modeling, demonstrate that hybrid approaches that acknowledge and address these inherent uncertainties provide the most accurate predictions of metabolic behavior [4] [3] [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative analysis suggests that robust metabolic flux studies should integrate multiple methodologies, with computational predictions guiding experimental design and experimental data informing model refinement. As both computational and experimental technologies advance, the continued acknowledgment and systematic addressing of these inherent uncertainties will remain essential for accurate metabolic flux determination in basic research and pharmaceutical applications.

Advanced Methods and Integrative Approaches for Improved Flux Predictions

Constraint-based modeling, and specifically Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), has become a cornerstone of systems biology for predicting metabolic behavior. However, a significant challenge with standard FBA is that genome-scale models are underdetermined, leading to uncertainty in flux predictions and limiting their predictive accuracy and interpretability [7] [28]. The integration of high-throughput transcriptomics and proteomics data offers a promising path to refine these models by incorporating data on cellular regulation and enzyme abundance. This guide objectively compares the performance of various methods that utilize omics data to constrain FBA models, evaluating them against a baseline of parsimonious FBA (pFBA) and experimental flux measurements.

Methodologies for Omics Integration in FBA

Several computational strategies have been developed to integrate gene and protein expression data into constraint-based models. These methods generally fall into two categories: those that use expression data to directly set flux bounds, and those that seek to maximize consistency between predicted fluxes and expression levels [29].

Direct Integration Methods

- E-Flux: This approach directly models the maximum allowable flux for a reaction as a function of its associated gene expression level [29].

- Linear Bound FBA (LBFBA): A novel method that uses expression data to place soft, linear constraints on individual fluxes. These constraints are reaction-specific and parameterized using training data containing both expression and experimentally measured flux values [29].

- Prom: Integrates expression data directly into flux bounds, though it does not require flux data for parameterization [29].

Consistency-Based Methods

- GIMME (Gene Inactivity Moderated by Metabolism and Expression): Minimizes the flux through reactions whose associated genes fall below an expression threshold, weighted by the difference from the threshold [29].

- iMAT: Maximizes the agreement between flux states (high or low) and gene expression states (high or low) by dividing reactions into categories based on expression levels [29].

- tFBA (Transcriptomically controlled FBA): Minimizes the violation of an assumption that significant changes in gene expression between conditions should correspond to flux changes [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Omics Integration Methods for FBA

| Method | Integration Approach | Requires Flux Training Data | Key Algorithmic Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| LBFBA | Direct (Soft bounds) | Yes | Reaction-specific linear bounds from training data |

| E-Flux | Direct (Hard bounds) | No | Flux bounds are direct functions of expression |

| GIMME | Consistency | No | Minimizes flux through lowly expressed reactions |

| iMAT | Consistency | No | Maximizes consistency between binary flux and expression states |

| tFBA | Consistency | No | Minimizes violation of expression-change to flux-change assumption |

| pFBA | None (Baseline) | No | Maximizes biomass yield, minimizes total flux |

Performance Comparison Against Experimental Flux Data

The true test for any FBA method is how well its predictions match experimentally measured intracellular fluxes, typically determined using 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) [7] [30]. A critical study by Machado and Herrgård previously found that pFBA predictions were as good as or better than those from various algorithms integrating transcriptomics or proteomics data [29].

Quantitative Performance of LBFBA

The development of LBFBA has challenged this narrative. When applied to E. coli and S. cerevisiae datasets, LBFBA demonstrated a significant improvement in flux prediction accuracy over pFBA.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of LBFBA vs. pFBA

| Organism | Training Conditions | Reactions Constrained (Rexp) | Normalized Error (LBFBA) | Normalized Error (pFBA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Mutant multi-omics dataset [29] | 37 | ~50% lower than pFBA | Baseline |

| S. cerevisiae | Aerobicity multi-omics dataset [29] | 33 | ~50% lower than pFBA | Baseline |

LBFBA's key innovation is using a training dataset with paired expression and flux measurements to learn reaction-specific parameters (a_j, b_j, c_j) for the linear bound functions [29]. The core LBFBA constraint is:

Where g_j is the expression level for reaction j, v_glucose is the glucose uptake rate, and α_j is a non-negative slack variable that allows bounds to be violated at a cost [29].

Carbon-Constrained FBA (ccFBA)

An alternative constraint-based approach, carbon-constrained FBA (ccFBA), refines flux predictions by imposing elemental balance of carbon on intracellular reactions. This method, which does not rely on omics data, has also been shown to substantially improve the accuracy of predicted flux values compared to standard FBA when validated against experimentally-measured intracellular fluxes in CHO cells [28].

Evolutionary Validation of FBA Predictions

The optimality assumptions underlying FBA can be tested by examining how metabolism evolves in long-term experimental evolution. Research has shown that the predictive power of FBA scales with the initial distance of the ancestor from the predicted optimum. Strains beginning further from optimum tend to evolve fluxes that move toward FBA predictions, while highly optimized ancestors may evolve in ways that slightly decrease yield while increasing substrate uptake rate [30].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Parameterizing and Validating LBFBA

The experimental workflow for developing and testing LBFBA involves a multi-step process that combines multi-omics data collection, model parameterization, and cross-condition validation [29].

1. Multi-omics Training Data Collection:

- Cultivate cells under a set of reference conditions.

- Measure extracellular flux rates (e.g., substrate uptake, product secretion).

- Quantify transcriptome or proteome using microarrays/RNA-seq or mass spectrometry.

- Determine intracellular metabolic fluxes using 13C-MFA with GC-MS analysis of proteinogenic amino acids [29] [7].

2. Model Parameterization:

- Calculate reaction-specific expression values (

g_j) from omics data using GPR rules. - For isoenzymes:

g_j= sum of isoenzyme expression. - For enzyme complexes:

g_j= minimum expression across subunits [29]. - Use linear regression on training data to estimate parameters

a_j,b_j,c_jfor each reaction inR_exp.

3. Flux Prediction in New Conditions:

- Measure only transcriptomics/proteomics data under the new condition of interest.

- Apply the learned parameters to set flux bounds in the LBFBA formulation.

- Solve the LBFBA optimization problem to predict the flux distribution [29].

4. Validation:

- Compare LBFBA predictions to experimentally determined 13C-MFA fluxes not used in training.

- Calculate normalized error and compare against pFBA and other methods [29].

Model Validation and Selection in Metabolic Flux Analysis

Robust validation is essential for assessing the reliability of constraint-based model predictions. For 13C-MFA, the χ²-test of goodness-of-fit is widely used to validate whether the difference between measured and estimated mass isotopomer distributions is statistically significant [7]. However, researchers are increasingly adopting complementary validation approaches, including:

- Flux uncertainty estimation to quantify confidence intervals around flux estimates.

- Parallel labeling experiments using multiple tracers to improve flux resolution.

- Incorporating metabolite pool size information for enhanced validation [7].

For FBA, one of the most robust validations is comparison against 13C-MFA estimated fluxes [7]. This cross-validation approach helps establish the fidelity of model-derived fluxes to real in vivo metabolism.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Multi-omics Constrained FBA

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Data Repositories | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [31], Answer ALS [31], jMorp [31] | Provide publicly available multi-omics datasets from patient samples for method development and testing. |

| Pathway Databases | KEGG, Reactome, MetaCyc [32] | Provide curated metabolic pathway information and stoichiometric matrices for constraint-based modeling. |

| Visualization Tools | PathVisio [33], Cytoscape [32] | Enable visualization of multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, fluxes) on biological pathways. |

| Stoichiometric Models | organism-specific GEMs (e.g., iCHO1766 [28]) | Genome-scale metabolic models used as the core framework for FBA simulations. |

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [U-13C] glucose) | Essential for 13C-MFA experiments to measure intracellular metabolic fluxes for model validation. |

Integration of transcriptomics and proteomics data into FBA models represents a powerful approach to enhance the accuracy and biological relevance of metabolic predictions. Among the various methods available, LBFBA demonstrates superior performance, reducing normalized flux prediction errors by approximately half compared to pFBA. However, this performance advantage comes with the requirement for training data with paired flux and expression measurements. Methods like ccFBA show that alternative constraint strategies without omics data can also significantly improve flux predictions. The choice of integration method should therefore be guided by available data, biological context, and the need for quantitative accuracy versus qualitative insights. As multi-omics technologies continue to advance, the integration of transcriptomic, proteomic, and fluxomic data will undoubtedly yield increasingly sophisticated and predictive models of cellular metabolism.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has emerged as a fundamental computational framework for predicting metabolic behavior in biological systems, enabling researchers to simulate flux distributions through metabolic networks at genome-scale. However, traditional FBA approaches frequently diverge from experimental flux measurements, primarily because they lack incorporation of critical biological constraints such as enzyme kinetics and proteomic limitations. This discrepancy has motivated the development of enzyme-constrained FBA (ecFBA), which integrates catalytic efficiency parameters and enzyme abundance data to generate more biologically accurate predictions [34].

The integration of enzyme constraints addresses a fundamental limitation of conventional FBA: its tendency to predict theoretically optimal flux states that may not be physiologically feasible due to limited cellular resources. By accounting for the biosynthetic costs of enzyme production and the kinetic limitations of catalytic proteins, ecFBA creates a more realistic modeling framework that better aligns with experimental observations across diverse biological systems, from microorganisms to complex multicellular organisms [35] [19].

Methodological Framework: How ecFBA Incorporates Enzyme Kinetics

Core Mathematical Formulation

The fundamental principle underlying ecFBA is the extension of traditional stoichiometric models through the incorporation of enzyme kinetics constraints. The core mathematical relationship can be expressed as:

[ vj \leq k{cat}^{j} \times [E_j] ]

Where ( vj ) represents the flux of metabolic reaction ( j ), ( k{cat}^{j} ) is the turnover number of the enzyme catalyzing the reaction, and ( [E_j] ) is the enzyme concentration [34]. This inequality constraint ensures that the flux through any metabolic reaction cannot exceed the maximum catalytic capacity determined by both the abundance and efficiency of its corresponding enzyme.

Implementation Approaches

Several computational frameworks have been developed to implement enzyme constraints in metabolic models:

GECKO (Genome-scale model with Enzymatic Constraints using Kinetic and Omics): This approach expands the stoichiometric matrix by incorporating enzymes as pseudo-metabolites and adding associated pseudo-reactions representing enzyme utilization. The GECKO framework has been successfully applied to models of S. cerevisiae, E. coli, and A. niger [34].

Constrained Allocation FBA (CAFBA): This method incorporates proteome allocation constraints based on bacterial growth laws, effectively modeling the trade-offs between metabolic sectors (ribosomal, biosynthetic, transport, and housekeeping) under different growth conditions [36].

Resource Balance Analysis (RBA): This approach implements hard constraints on enzyme capacities and predicts protein allocation by estimating apparent catalytic rates of enzymes [34].

Table 1: Key Implementation Methods for ecFBA

| Method | Key Features | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO | Expands stoichiometric matrix; incorporates kcat values and enzyme abundance data | S. cerevisiae, E. coli, A. niger | [34] |

| CAFBA | Incorporates proteome allocation constraints based on bacterial growth laws | E. coli carbon metabolism | [36] |

| RBA | Uses hard constraints on enzyme capacities; estimates apparent catalytic rates | B. subtilis | [34] |

Workflow for Constructing ecFBA Models

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for developing and implementing an enzyme-constrained metabolic model:

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Integration of Multi-Omics Data

The construction of ecFBA models requires the systematic integration of diverse datasets. The ECMpy workflow exemplifies this process, involving:

Model Preprocessing: Conversion of reversible reactions to irreversible representations and splitting of reactions catalyzed by multiple isoenzymes into independent reactions to assign appropriate kcat values [1].

Kinetic Parameter Curation: kcat values are obtained from databases such as BRENDA, with careful consideration of organism-specific variations. For reactions without experimental data, computational estimation or cross-species extrapolation is employed [1] [37].

Proteomic Data Integration: Protein abundance data from sources like PAXdb are incorporated as constraints, with homologous protein abundance used for enzymes lacking direct measurements [34].

Enzyme Capacity Constraints: The total protein pool is constrained based on experimental measurements of cellular protein content, typically implemented as:

[ \sum \frac{vj}{k{cat}^j} \leq P_{total} ]

Where ( P_{total} ) represents the total enzyme capacity available in the cell [1].

Validation Against Experimental Flux Measurements

The predictive accuracy of ecFBA models is typically validated through comparison with experimental flux measurements obtained via 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). This involves:

Quantitative Comparison: Calculating the agreement between predicted and measured fluxes using metrics such as weighted average percent error [19].

Condition-Specific Validation: Testing model predictions across diverse growth conditions, including nutrient limitations, genetic perturbations, and different growth rates [35].

Dynamic Validation: For dynamic FBA implementations, comparing predicted metabolite concentrations and growth dynamics with time-course experimental data [35].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Traditional FBA vs. ecFBA

| Prediction Metric | Traditional FBA | ecFBA | Experimental Reference | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Dilution Rate (h⁻¹) | Not predicted | 0.27 h⁻¹ | 0.21-0.38 h⁻¹ [35] | S. cerevisiae |

| Glucose Uptake Rate | Proportional to growth rate | Sharp increase after Dcrit matching data | Experimental curves [35] | S. cerevisiae |

| Acetate Excretion | Qualitative only | Quantitative accuracy | Empirical growth laws [36] | E. coli |

| Flux Prediction Error | 94-180% | 9-13% | 13C-MFA validation [19] | A. thaliana |

Case Studies: ecFBA Performance Across Biological Systems

Microbial Systems: E. coli and S. cerevisiae

In microbial systems, ecFBA has demonstrated remarkable improvements in predicting metabolic behaviors. For E. coli, CAFBA successfully reproduces the crossover from respiratory, yield-maximizing states at slow growth to fermentative states with carbon overflow at fast growth, quantitatively predicting acetate excretion rates based on only three parameters determined by empirical growth laws [36].

For S. cerevisiae, ecFBA implementations such as ecYeast8 accurately predict the onset of the Crabtree effect, a critical dilution rate (Dcrit) beyond which ethanol production begins. The model predicted a Dcrit of 0.27 h⁻¹, closely matching experimental values ranging from 0.21-0.38 h⁻¹ for different strains. Furthermore, ecYeast8 correctly predicts the sharp increase in glucose uptake and decrease in biomass yield after Dcrit, phenomena not captured by traditional FBA [35].

Multicellular Eukaryotic Systems

The application of ecFBA to plant systems represents a significant advancement for metabolic engineering in complex organisms. In Arabidopsis thaliana, incorporating tissue-specific gene expression data into ecFBA dramatically improved agreement with experimental flux maps, reducing the weighted average percent error from 94-180% (with traditional FBA) to 9-13% [19].

This integration of relative expression levels between tissues as weighting factors for flux minimization enables more accurate predictions in multi-tissue systems, addressing a fundamental challenge in plant metabolic engineering where functional diversity across tissues creates complex metabolic networks [19].

Industrial Applications: A. niger

The implementation of ecFBA for the industrially important fungus A. niger (eciJB1325 model) demonstrated significant improvements in predicting metabolic phenotypes. The enzyme-constrained model showed reduced flux variability, with over 40% of metabolic reactions exhibiting significantly decreased variability ranges compared to the traditional model [34].

Additionally, the ecFBA model enabled more accurate prediction of gene essentiality and differential enzyme expression requirements under different substrate conditions, providing valuable insights for strain engineering to optimize production of organic acids and enzymes [34].

Regulatory Networks and Metabolic Crosstalk

The integration of enzyme kinetics with metabolic models has revealed extensive regulatory crosstalk within metabolic networks. Mapping enzyme-metabolite activation interactions from the BRENDA database onto genome-scale metabolic models has shown that up to 54% of enzymatic reactions could be intracellularly activated, forming a complex network of metabolic regulation that spans multiple pathways [37].

The following diagram illustrates the network of enzyme-metabolite activation interactions identified through integration of kinetic data with metabolic models:

This regulatory network demonstrates that enzyme activators are distributed across all metabolic pathways, with highly activating metabolites more likely to be essential for growth, while highly activated enzymes are predominantly non-essential, suggesting that cells employ enzyme activators to finely regulate secondary metabolic pathways required under specific conditions [37].

Successful implementation of ecFBA requires carefully curated data resources and computational tools. The following table outlines key components of the ecFBA research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ecFBA Implementation

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | iML1515 (E. coli), Yeast8 (S. cerevisiae), iJB1325 (A. niger) | Provide stoichiometric representation of metabolic network | Model databases (e.g., BiGG, BioModels) |

| Enzyme Kinetic Parameters | kcat values, Michaelis constants (Km) | Define catalytic efficiency of enzymes | BRENDA database, literature curation [1] [37] |

| Proteomics Data | Protein abundance measurements | Constrain maximum enzyme capacities | PAXdb, experimental quantitation [34] |

| Software Tools | COBRApy, GECKO toolbox, ECMpy | Implement constraint-based modeling and optimization | Open-source computational frameworks [1] |

| Validation Data | 13C-MFA flux maps, gene essentiality data | Benchmark model predictions against experimental measurements | Literature curation, specialized databases [19] |

Enzyme-constrained FBA represents a significant advancement over traditional flux balance analysis, bridging the gap between theoretical predictions and experimental flux measurements across diverse biological systems. By incorporating fundamental biochemical constraints related to enzyme kinetics and proteomic allocation, ecFBA generates more physiologically realistic predictions that better align with empirical observations.