Bridging the Gaps: A Comprehensive Guide to Network Gaps in Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions (GENREs) are powerful computational tools that map an organism's metabolism from its genome.

Bridging the Gaps: A Comprehensive Guide to Network Gaps in Genome-Scale Metabolic Reconstructions

Abstract

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions (GENREs) are powerful computational tools that map an organism's metabolism from its genome. However, their predictive power is often limited by network gaps—missing reactions or pathways resulting from incomplete genomic annotations or biochemical knowledge. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on the nature of metabolic network gaps, their impact on phenotype predictions, and the evolving methodologies to identify, resolve, and validate these gaps. We explore foundational concepts, advanced gap-filling algorithms from machine learning and topology-based approaches, troubleshooting strategies for optimization, and rigorous validation frameworks using experimental data. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build more accurate metabolic models for applications in systems biology, metabolic engineering, and drug target discovery.

What Are Metabolic Network Gaps? The Foundations and Impact on Model Predictions

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are mathematical representations of the metabolic network of an organism, integrating genes, proteins, reactions, and metabolites to simulate metabolic flux distributions under specific conditions [1]. The reconstruction of high-quality GEMs is fundamental to systems biology, enabling predictions of cellular behavior, identification of drug targets, and understanding of host-microbiome interactions [1] [2] [3]. However, even the most carefully constructed models contain knowledge gaps—missing metabolic capabilities due to incomplete genomic annotations, fragmented genomes, or limited biochemical knowledge [4] [5]. These network gaps manifest primarily as dead-end metabolites that cannot be produced or consumed, and incomplete pathways that prevent the synthesis of essential biomass components [5].

The problem of metabolic gaps is particularly acute for non-model organisms and microbial community members, where experimental data is often scarce [4] [5]. Microorganisms that cannot be easily cultivated individually present significant challenges for metabolic reconstruction due to their complex metabolic interdependencies with other community members [4]. Gap-filling has thus become an indispensable part of the metabolic reconstruction process, with both traditional optimization-based methods and emerging machine learning approaches being deployed to resolve these inconsistencies [4] [5].

Classifying and Identifying Network Gaps

Types of Metabolic Gaps

Network gaps in GEMs can be systematically categorized based on their metabolic manifestations and computational identification methods. The table below summarizes the primary gap types and their characteristics.

Table 1: Classification of Network Gaps in Metabolic Reconstructions

| Gap Type | Definition | Identification Method | Impact on Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dead-end Metabolites | Metabolites that can be produced but not consumed, or vice versa, creating metabolic dead ends | GapFind/GapFill algorithms [5] | Prevents flux through connected pathways; limits metabolic functionality |

| Incomplete Pathways | Missing reactions in otherwise complete biochemical pathways, creating functional gaps | Pathway topology analysis [6] | Inability to synthesize essential biomass components or utilize substrates |

| Mass/Charge Imbalances | Reactions that violate conservation of mass or charge principles | checkMassChargeBalance programs [1] | Thermodynamic infeasibilities; incorrect flux predictions |

| Blocked Reactions | Reactions that cannot carry flux under any condition due to network connectivity issues | Flux variability analysis [5] | Reduces model predictive capability; indicates missing connectivity |

Detection Methodologies

The identification of network gaps employs both topological analyses and flux-based methods. Topological approaches examine the connectivity of the metabolic network without considering reaction stoichiometry or constraints. Tools such as GapFind identify dead-end metabolites by analyzing which metabolites serve only as reactants or products within the network [3]. Flux-based methods like GapFill utilize constraint-based modeling to detect gaps by testing whether reactions can carry flux when the production of biomass or other key metabolites is required [1].

More recently, machine learning approaches such as CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) have been developed to predict missing reactions purely from metabolic network topology, without requiring experimental data [5]. These methods frame the prediction of missing reactions as a hyperlink prediction task on a hypergraph, where each reaction is represented as a hyperlink connecting all participating metabolites [5].

Computational Approaches for Gap Resolution

Traditional Gap-Filling Algorithms

Traditional gap-filling methods typically formulate the problem as an optimization task that identifies a set of reactions from a biochemical database that, when added to the model, restore metabolic functionality. The GapFill algorithm was among the first to be formalized as a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem that identifies dead-end metabolites and adds reactions from databases like MetaCyc to restore network connectivity [4]. Subsequent approaches such as FastGapFill improved computational efficiency while maintaining the same fundamental principle of minimizing the number of added reactions necessary to enable growth or metabolite production [1].

These methods generally require phenotypic data as input to identify inconsistencies between model predictions and experimental observations [5]. For example, if a model cannot produce a biomass component that the organism is known to synthesize, gap-filling algorithms will identify the minimal set of reactions needed to resolve this inconsistency. The performance of these algorithms depends heavily on the quality and completeness of the reference database used, with common sources including ModelSEED, MetaCyc, KEGG, and BiGG [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Gap-Filling Methods

| Method | Approach | Data Requirements | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GapFill | MILP optimization | Phenotypic data | Comprehensive; ensures network connectivity | Computationally intensive; requires experimental data |

| FastGapFill | Linear Programming | Phenotypic data | Faster computation; efficient for large models | May add non-biological reactions |

| CHESHIRE | Deep learning on hypergraphs | Network topology only | No experimental data needed; high accuracy | Limited validation on non-model organisms |

| Community Gap-Filling | Multi-species optimization | Metagenomic data | Resolves gaps using community interactions | Complex implementation; community data required |

Machine Learning and Topology-Based Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning have enabled the development of gap-filling methods that operate purely from network topology, without requiring experimental phenotypic data. The CHESHIRE method uses a deep learning architecture that represents metabolic networks as hypergraphs, where each reaction is a hyperlink connecting its substrate and product metabolites [5]. The approach employs Chebyshev spectral graph convolutional networks (CSGCN) to refine metabolite feature vectors by incorporating information from connected metabolites, then pools these features to generate reaction-level representations for predicting missing reactions [5].

In internal validations using 108 high-quality BiGG models, CHESHIRE demonstrated superior performance in recovering artificially removed reactions compared to other topology-based methods like Neural Hyperlink Predictor (NHP) and Clique Closure-based Coordinated Matrix Minimization (C3MM) [5]. This suggests that topology-based machine learning methods can effectively complement traditional gap-filling approaches, particularly for non-model organisms where experimental data is limited.

Community-Aware Gap-Filling

For microorganisms that naturally exist in complex communities, community-level gap-filling represents a powerful alternative to single-organism approaches. This method resolves metabolic gaps by considering the metabolic interactions between coexisting species [4]. The algorithm combines incomplete metabolic reconstructions of microorganisms known to coexist and allows them to interact metabolically during the gap-filling process, adding the minimum number of biochemical reactions necessary to restore community growth [4].

This approach has been successfully applied to communities such as Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the human gut microbiome, where it identified cooperative metabolic interactions that single-species gap-filling would have missed [4]. Community gap-filling is particularly valuable for analyzing metagenomic data from environmental samples or enrichments, where individual metabolic models may be highly incomplete [4].

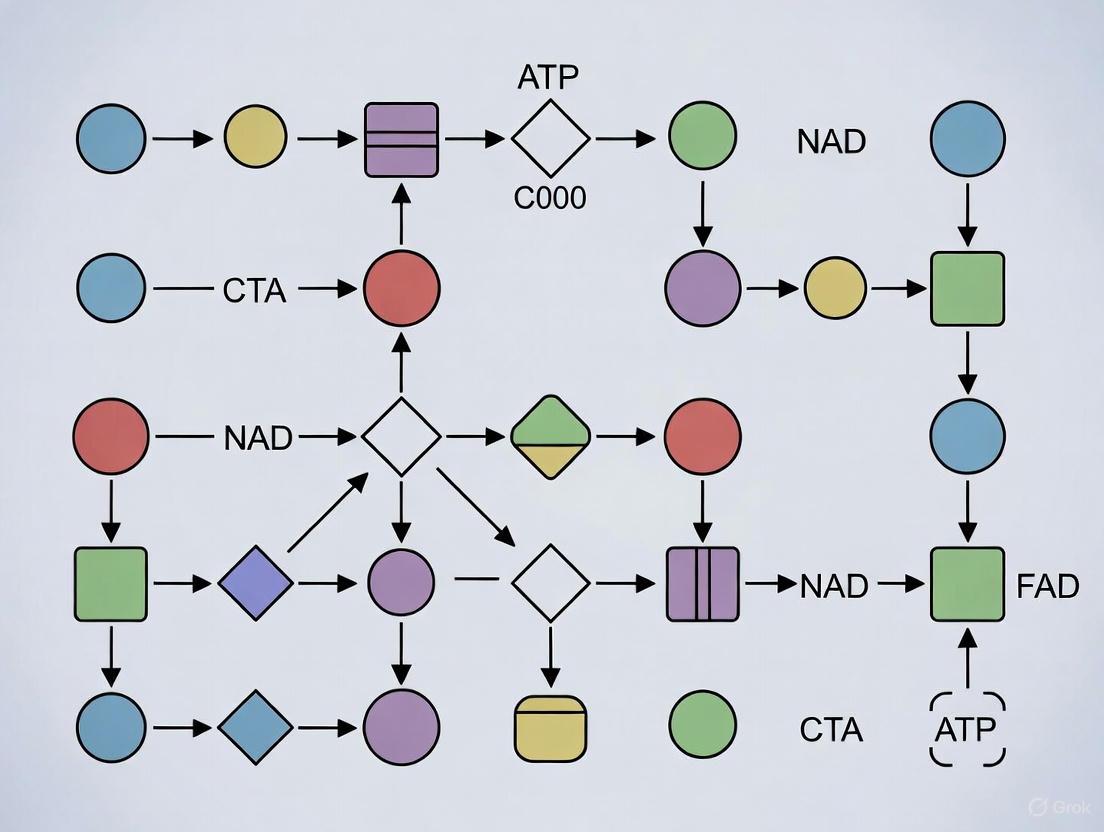

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Gap-Filling Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the decision process for selecting and implementing appropriate gap-filling methodologies based on available data and biological context.

Experimental Validation and Model Refinement

Protocol for Experimental Validation of Gap-Filling Predictions

Objective: To experimentally validate predicted metabolic capabilities restored through computational gap-filling.

Materials:

- Bacterial strain of interest

- Chemically defined medium (CDM)

- Nutrient supplements (amino acids, nucleotides, vitamins)

- Anaerobic chamber (for anaerobic organisms)

- Spectrophotometer for growth measurement

Methodology:

- Prepare minimal and complete media: Based on the CDM formulation used in Streptococcus suis validation [1], which contained 55.5 mM glucose, 1.1225 mM L-alanine, and other essential nutrients.

Design leave-one-out experiments: Systematically omit specific nutrients from the complete CDM to test the model's predictions about metabolic capabilities [1].

Inoculate and monitor growth:

- Harvest bacterial cells in logarithmic growth phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 1.0)

- Wash cells three times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline

- Resuspend to OD₆₀₀ of 0.8

- Inoculate test media at 1% (v/v)

- Measure optical density at 600 nm at regular intervals

Compare growth phenotypes: Normalize growth rates to the growth rate in complete CDM and compare with model predictions [1].

Interpretation: Growth in minimal media indicates the model correctly predicted metabolic capabilities, while lack of growth suggests remaining gaps or incorrect pathway predictions.

Biomass Composition Determination

A critical component of metabolic model validation is accurate representation of biomass composition. For organisms where direct experimental data is unavailable, biomass composition can be adopted from phylogenetically related organisms. In the S. suis model iNX525, the macromolecular composition was adopted from Lactococcus lactis (iAO358 model), containing:

- Proteins (46%)

- DNA (2.3%)

- RNA (10.7%)

- Lipids (3.4%)

- Lipoteichoic acids (8%)

- Peptidoglycan (11.8%)

- Capsular polysaccharides (12%)

- Cofactors (5.8%) [1]

The DNA, mRNA, and amino acid compositions should be calculated from the specific organism's genome and protein sequences [1].

Case Studies in Gap-Filling Applications

Resolving Metabolic Gaps in Streptococcus suis

The reconstruction of the Streptococcus suis model iNX525 demonstrates a comprehensive approach to gap-filling. The draft model was constructed using both the automated ModelSEED pipeline and homology comparison with template models from Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pyogenes [1]. Metabolic gaps in the draft model were automatically analyzed using the gapAnalysis program in the COBRA Toolbox and manually filled by adding relevant reactions based on biochemical databases and literature [1].

The manual curation process included:

- Reannotation of enzymes by comparing S. suis genome with proteins of known function

- Addition of transporters annotated from the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB)

- Assignment of new gene functions via BLASTp using UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot

- Balancing reactions by adding H₂O or H⁺ as needed [1]

The resulting model contained 525 genes, 708 metabolites, and 818 reactions, with flux balance analysis showing good agreement with experimental growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions [1].

Community-Level Gap-Filling in Bacterial Vaginosis

A study of bacterial vaginosis (BV) associated species demonstrated the application of community-aware metabolic modeling to understand polymicrobial interactions [2]. Researchers analyzed metagenomic data from human vaginal swabs to generate GENREs (Genome-scale Metabolic Network Reconstructions) for BV-associated bacteria including Gardnerella species, Prevotella species, and Lactobacillus iners [2].

Community-level gap-filling revealed complex mutualistic and competitive relationships between BV-associated bacteria that were not apparent from single-species models [2]. For example, L. iners and A. christensenii showed significant mutualistic benefits in pairwise simulations, while certain Gardnerella strains were repeatedly outcompeted in community contexts [2]. These findings underscore the importance of community-aware gap-filling for understanding complex microbial ecosystems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Gap Analysis

| Category | Item/Resource | Function/Application | Example Tools/Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling; includes gapAnalysis program | COBRApy (Python implementation) [1] |

| ModelSEED | Automated metabolic reconstruction pipeline from genome annotations | KBase platform [1] [7] | |

| MetaDAG | Web tool for metabolic network reconstruction and analysis from KEGG data | MetaDAG [6] | |

| Reference Databases | Biochemical Databases | Source of reactions for gap-filling | ModelSEED, MetaCyc, KEGG, BiGG [4] |

| Protein Databases | Functional annotation of genes | UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot [1] | |

| Transporters | Annotation of transport reactions | Transporter Classification Database (TCDB) [1] | |

| Experimental Materials | Chemically Defined Medium | Controlled growth conditions for phenotype validation | Custom formulations with specific nutrients [1] |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Cultivation of oxygen-sensitive microorganisms | Essential for strict anaerobes like F. prausnitzii [4] |

Diagram 2: Methodological Approaches for Resolving Network Gaps. This diagram illustrates the four primary computational strategies for identifying and resolving metabolic gaps in genome-scale models.

The identification and resolution of network gaps—from dead-end metabolites to incomplete pathways—remains a critical challenge in metabolic reconstruction. While significant advances have been made in both traditional optimization-based methods and emerging machine learning approaches, the field continues to evolve toward community-aware modeling and integration of multi-omics data.

Future directions include the development of hybrid methods that combine the mechanistic understanding of traditional constraint-based approaches with the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning. Resources such as the APOLLO database of 247,092 microbial metabolic reconstructions [3] will enable more comprehensive gap-filling by providing extensive reference networks across diverse taxonomic groups. Additionally, tools like MetaDAG that facilitate automated reconstruction and comparison of metabolic networks across multiple organisms will accelerate the resolution of metabolic gaps in complex microbial communities [6].

As the field progresses, the integration of kinetic parameters, regulation data, and spatial organization into metabolic models will likely reveal new categories of network gaps beyond the current focus on reaction connectivity, further refining our ability to model cellular metabolism with high fidelity.

Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions (GENREs) are computational representations of the metabolic network of an organism, connecting genes to proteins to biochemical reactions [8]. These models are crucial for simulating metabolic fluxes, predicting phenotypic behaviors, and guiding metabolic engineering [9]. However, network gaps—missing metabolic functions in these reconstructions—represent significant obstacles to model accuracy and utility. These gaps manifest as blocked reactions, dead-end metabolites, and an inability to simulate observed growth phenotypes, ultimately limiting predictions for biotechnological and biomedical applications [10] [11].

The primary causes of these network gaps are intrinsically linked to fundamental limitations in our biological knowledge: imperfect genome annotation and an incomplete atlas of known biochemistry. Even in well-studied model organisms like Escherichia coli, approximately 35% of genes lack functional annotation [10]. This review provides an in-depth technical analysis of these root causes, presents quantitative assessments of their impact, and outlines advanced computational methodologies for gap identification and resolution, providing researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for enhancing metabolic network reconstructions.

The Impact of Imperfect Genome Annotation

Quantitative Assessment of Annotation Inconsistencies

Imperfect genome annotation refers to the inability to assign accurate biochemical functions to all genes within a genome. Automated annotation tools, which rely on sequence homology and conserved domain identification, often produce conflicting results. A comprehensive reannotation of 27 bacterial reference genomes revealed startling discrepancies between major annotation tools [12]. As shown in Table 1, the overlap between different annotation platforms is remarkably small, with each tool contributing substantial unique annotations.

Table 1: Annotation Inconsistencies Across Functional Annotation Tools

| Annotation Tool | Average Unique Gene-EC Annotations | Percentage of Total Annotations | Agreement with Other Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAST | Not Reported | Not Reported | 50-86% |

| KEGG | Not Reported | Not Reported | 50-86% |

| EFICAz | 23.4% | 23.4% | 69.7-86.4% |

| BRENDA | 47.5% | 47.5% | 56.0-69.7% |

The consequences of these inconsistencies are profound for metabolic reconstruction. When comparing RAST, KEGG, EFICAz, and BRENDA, fewer than a quarter of all gene-EC annotations were agreed upon by at least three tools [12]. This lack of consensus means that the metabolic network derived from any single annotation source is inherently incomplete. Combining multiple annotation tools can increase metabolic network size by an average of 40% for EC numbers and 37% for metabolic genes, with even greater improvements for non-model organisms [12].

Impact on Model Quality and Coverage

The Streptococcus suis metabolic reconstruction iNX525 exemplifies the practical challenges of annotation limitations. The draft model constructed from RAST annotations and ModelSEED contained only 392 genes, but homology-based comparisons with template models from related organisms significantly expanded this coverage to 525 genes in the final curated model [1]. This 34% increase in gene coverage through multi-source annotation highlights the critical importance of leveraging diverse annotation resources.

The ramifications extend to essentiality predictions. In E. coli iML1515, imperfect annotation resulted in 148 false-negative gene essentiality predictions corresponding to 152 false-negative essential reactions [10]. These represent metabolic functions that the model cannot simulate but that experimental evidence confirms must exist in the living organism.

The Challenge of Limited Biochemical Knowledge

The Unknown Metabolic Space

Beyond annotation issues, an incomplete biochemical knowledge base constitutes the second major cause of network gaps. Even with perfect gene annotation, our understanding of possible biochemical transformations remains limited. The ATLAS of Biochemistry, which includes over 150,000 putative reactions between known metabolites, represents attempts to define the upper limits of possible biochemical space [10]. These putative reactions—biochemically plausible but not yet experimentally observed—highlight the vastness of unknown metabolism.

Quantitatively, this knowledge gap manifests in metabolic models as blocked reactions and dead-end metabolites. An analysis of 130 genome-scale metabolic models in the ModelSEED database revealed that approximately one-third of reactions in each model were blocked even after standard gap-filling procedures [12]. This persistent blockage occurs because current gap-filling algorithms are limited to known biochemistry, unable to propose truly novel metabolic functions.

Consequences for Multi-Species Modeling

The limitations of biochemical knowledge become particularly problematic when modeling microbial communities and host-microbe interactions. In studies of bacterial vaginosis (BV), metabolic network reconstructions have revealed complex mutualistic and competitive relationships between BV-associated bacteria that cannot be fully explained by existing biochemical databases [2]. Similarly, host-microbe interaction studies struggle to account for the full spectrum of metabolic exchanges due to incomplete knowledge of possible biochemical transformations [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Knowledge Gaps on Metabolic Models

| Gap Category | Quantitative Impact | Example Organism |

|---|---|---|

| Unannotated Metabolic Genes | ~35% of genes lack annotation | Escherichia coli [10] |

| Blocked Reactions | ~33% of reactions blocked after standard gap-filling | 130 models in ModelSEED [12] |

| False Essentiality Predictions | 148 false-negative genes (152 reactions) | Escherichia coli iML1515 [10] |

| Additional Gap-Filled Reactions | Average of 56 reactions per model | 130 models in ModelSEED [12] |

Methodologies for Identifying and Resolving Network Gaps

Workflow for Systematic Gap Identification

The NICEgame (Network Integrated Computational Explorer for Gap Annotation of Metabolism) workflow provides a systematic approach for identifying and curating metabolic gaps [10]. This seven-step methodology integrates computational tools to propose both known and hypothetical biochemical reactions to resolve network gaps, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The NICEgame workflow for identifying and resolving metabolic gaps

The process begins with harmonization of metabolite annotations between the metabolic model and reaction databases, followed by identification of metabolic gaps through comparison of in silico predictions with experimental data [10]. The model is then merged with the ATLAS of Biochemistry, creating an expanded network that enables identification of "rescued" reactions—those that are essential in the original model but become non-essential in the expanded network. Alternative biochemical routes are systematically identified, evaluated based on multiple criteria including thermodynamic feasibility and network impact, and ranked. Finally, candidate genes for catalyzing the proposed reactions are identified using the BridgIT tool, which maps biochemical reactions to potential enzyme sequences [10].

Multi-Tool Annotation Integration Strategy

Combining multiple functional annotation tools significantly increases coverage of metabolic annotations. The recommended methodology involves:

- Running multiple annotation tools (RAST, KEGG, EFICAz, BRENDA) on the target genome

- Extracting EC number annotations from each tool to enable cross-platform comparison

- Resolving conflicts through manual curation or consensus approaches

- Integrating transporter annotations from specialized tools like TransportDB

- Validating annotations against gold-standard databases like EcoCyc for model organisms [12]

This integrated approach is particularly valuable for non-model organisms, where phylogenetic distance from well-studied model organisms exacerbates annotation inaccuracies. For example, in Clostridium beijerinckii, combining annotations from SEED, KEGG, and RefSeq databases nearly doubled the number of genes and reactions in the final curated model compared to using any single source [12].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Gap Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Gap Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATLAS of Biochemistry | Database | 150,000+ putative biochemical reactions | Expands possible biochemical space for gap-filling [10] |

| BridgIT | Computational Tool | Maps biochemical reactions to enzyme sequences | Identifies candidate genes for orphan reactions [10] |

| NICEgame | Workflow | Systematic identification and curation of metabolic gaps | Resolves false essentiality predictions [10] |

| ModelSEED | Platform | Automated metabolic model reconstruction | Provides draft models for manual curation [1] |

| TransportDB | Database | Annotates membrane transport proteins | Improves coverage of metabolite uptake and secretion [12] |

| COBRA Toolbox | Software Suite | Constraint-based modeling and analysis | Performs flux balance analysis and gap-filling [1] |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Computational predictions of gap-filling solutions require experimental validation. The following protocol outlines a methodology for validating predicted metabolic interactions:

Growth Assays in Defined Media: As demonstrated in Streptococcus suis validation, prepare chemically defined media (CDM) with specific nutrient exclusions to test model predictions of auxotrophies [1]. Measure optical density at 600 nm over time and compare growth rates between complete and nutrient-limited conditions.

Spent Media Experiments: To validate predicted metabolic interactions between species, grow donor strains in appropriate media, filter-sterilize the spent media (0.22 μm filter), and use as the growth medium for recipient strains [2]. Compare growth in spent media versus fresh media controls to identify cross-feeding relationships.

Metabolomic Analysis: Use liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to identify metabolites in spent media that potentially underlie metabolic interactions [2]. Track the production and consumption of specific metabolites predicted by the model.

Gene Essentiality Validation: Compare computationally predicted essential genes with experimental gene knockout libraries. For E. coli, the iML1515 model validation used data from the Keio collection to identify discrepancies between predictions and experimental results [10].

Advanced Approaches: From Single Organisms to Microbial Communities

As metabolic modeling advances from single organisms to complex communities, gap identification and resolution become increasingly challenging. Community metabolic models require integration of multiple individual GENREs, each with their own annotation gaps and knowledge limitations [14]. The resource allocation models (RAMs) and ME-models represent next-generation approaches that incorporate proteomic constraints, providing more accurate predictions but also introducing new dimensions where gaps can manifest [8].

In microbial community modeling, such as in the study of bacterial vaginosis, gap resolution must account for cross-species metabolic interactions. As shown in Figure 2, these interactions can be complex, with species exhibiting both mutualistic and competitive relationships that are difficult to predict from individual metabolic models alone [2].

Figure 2: Microbial community metabolic modeling workflow with gap identification

These community models reveal that functional metabolic relatedness can differ significantly from genetic relatedness, emphasizing the need for gap-filling approaches that consider ecological context and interspecies dynamics [2]. Resolving gaps in such models requires understanding not only what metabolic functions are missing, but how those gaps affect community-level behaviors and stability.

Imperfect genome annotation and limited biochemical knowledge remain the primary causes of network gaps in genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. Quantitative analyses reveal the extent of these challenges, with different annotation tools agreeing on fewer than 25% of metabolic annotations and approximately one-third of reactions remaining blocked even after standard gap-filling procedures [12]. The development of integrated workflows like NICEgame, combined with multi-tool annotation strategies and expanding biochemical databases, provides promising pathways toward more complete metabolic networks.

Future progress will require enhanced computational methods, including machine learning approaches for gene function prediction, expanded databases of biochemical reactions, and standardized frameworks for model reconstruction and gap identification. As metabolic modeling continues to expand into complex microbial communities and host-microbe interactions, resolving network gaps will remain essential for accurate prediction of metabolic behaviors and effective application in biotechnology and medicine.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) provide a mathematical representation of cellular metabolism, enabling the prediction of physiological states and metabolic phenotypes through computational simulations. However, incomplete knowledge of metabolic processes often results in network gaps—missing reactions or pathways—that fundamentally compromise model accuracy. These gaps systematically bias predictive outcomes, frequently leading to overly optimistic phenotype predictions that do not align with experimental observations. This technical analysis examines the mechanistic relationship between network incompleteness and prediction errors, surveys quantitative evidence of their impact, and evaluates computational strategies for gap resolution. Understanding these limitations is essential for researchers relying on GEMs in metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and systems biology applications.

Genome-scale metabolic models are structured knowledgebases that mathematically represent the metabolic network of an organism, connecting genomic information with biochemical capabilities [9]. The reconstruction process involves compiling all known metabolic reactions, their associated genes (through gene-protein-reaction rules), and metabolites into a stoichiometric matrix that enables constraint-based simulation methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [9] [15]. However, even well-curated GEMs contain knowledge gaps—missing elements in the metabolic network—due to imperfect genome annotation, incomplete biochemical knowledge, and limitations in reconstruction algorithms [5] [15].

These network gaps manifest primarily as missing metabolic reactions that should be present based on genomic evidence or physiological observations, but which are absent from the model reconstruction [5]. The consequences are profound: gaps create erroneous connectivity patterns within the metabolic network, disrupting the accurate representation of substrate utilization, product formation, and energy conservation. When these incomplete networks are used for phenotypic prediction through simulation methods, the results frequently display systematic overestimation of metabolic capabilities, including growth rates, product yields, and substrate range [15]. This optimistic bias occurs because missing regulatory constraints and incomplete pathway representations allow metabolic fluxes to proceed through biologically impossible routes, generating predictions that exceed actual cellular capacities.

Mechanistic Links Between Gaps and Prediction Optimism

Disrupted Metabolic Connectivity and Network Topology

The topological structure of metabolic networks fundamentally determines their functional capabilities. Gaps disrupt this structure by creating dead-end metabolites—intermediates that can be produced but not consumed, or vice versa—which fragment the network and block natural metabolic routes [5] [15]. During simulation, algorithms may circumvent these blockages through thermodynamically infeasible paths or by activating improper isozyme functions, leading to predictions of growth or product formation where none should occur.

Figure 1: How Network Gaps Force Infeasible Bypass Routes. A missing reaction (red) creates a dead-end metabolite, forcing flux balance analysis to utilize thermodynamically infeasible alternative paths (yellow) to achieve biomass production, resulting in overly optimistic growth predictions.

Incorrect Gene-Protein-Reaction Associations

Boolean rules defining relationships between genes, enzymes, and metabolic reactions (GPR associations) represent another critical source of prediction errors when incomplete [15]. Missing or incorrect GPR rules lead to flawed essentiality predictions during in silico gene knockout studies. For example, if a GEM lacks an isozyme that can compensate for a deleted gene, the model will incorrectly predict no growth, while in reality the missing isozyme would maintain functionality. Conversely, overly permissive GPR rules may predict growth when none occurs experimentally.

Incomplete Biomass Objective Functions

The biomass objective function quantitatively defines the metabolic requirements for cellular growth, including essential biomass precursors like amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, and cofactors [15]. When gaps prevent the synthesis of these essential components, but the biomass function fails to properly account for their requirement, models may predict growth under conditions where it is actually impossible. This represents a fundamental stoichiometric imbalance that creates overly optimistic growth predictions.

Quantitative Evidence: Systematic Assessments of Prediction Errors

Multiple studies have systematically evaluated how gaps in metabolic networks impact phenotype prediction accuracy. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent large-scale assessments:

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of Gap Impacts on Phenotype Predictions

| Study Focus | Methodology | Key Findings on Prediction Errors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHESHIRE Validation | Artificial reaction removal from 926 GEMs | Topology-based gap-filling improved phenotype predictions for 49 draft GEMs; corrected false positive amino acid secretion and fermentation product predictions | [5] |

| Reconstruction Tool Comparison | Comparison of automated tools against manually curated models | Draft reconstructions consistently contained gaps leading to incorrect growth predictions; tool selection significantly impacted error rates | [16] |

| Uncertainty Assessment | Analysis of reconstruction decisions on model output | Different gap-filling approaches generated models with varying reaction sets (15-30% variability) that all passed validation tests but made divergent predictions | [15] |

| Multi-Strain Analysis | Pan-genome modeling of 55 E. coli strains | Strain-specific gaps explained differential growth capabilities; missing transport reactions caused false positive growth predictions on specific substrates | [9] |

The evidence consistently demonstrates that network incompleteness systematically biases phenotype predictions toward over-optimism. The CHESHIRE method specifically demonstrated that pure topological analysis of metabolic networks could identify missing reactions that, when added, improved phenotypic accuracy for fermentation products and amino acid secretion in 49 draft GEMs [5]. This suggests that network structure alone contains sufficient information to correct many overly optimistic predictions, without requiring extensive experimental data.

Methodologies for Identifying and Correcting Gap-Related Errors

Computational Gap-Filling Protocols

Gap-filling algorithms represent the primary computational approach for addressing network incompleteness. These methods typically follow a two-step process: (1) identification of metabolic gaps or dead-end metabolites, and (2) addition of reactions from universal biochemical databases to resolve these inconsistencies [5] [15]. The following experimental protocol outlines a standardized approach for gap identification and resolution:

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Systematic Gap Identification and Resolution

| Step | Procedure | Tools/Methods | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gap Detection | Identify dead-end metabolites and network bottlenecks | Metabolite connectivity analysis; Flux Variability Analysis | List of metabolites without production/consumption routes |

| 2. Phenotypic Inconsistency Mapping | Compare model predictions with experimental growth data | Growth phenotyping on defined media; False positive/negative growth prediction identification | Set of conditions where model and experiment disagree |

| 3. Reaction Candidate Generation | Extract possible missing reactions from biochemical databases | Database mining (BiGG, ModelSEED, KEGG); Phylogenetic profiling | Pool of candidate reactions to resolve gaps |

| 4. Network Integration | Select and integrate minimal reaction sets to resolve inconsistencies | Optimization-based gap-filling (e.g., CarveMe); Machine learning approaches (CHESHIRE) | Extended metabolic network with improved connectivity |

| 5. Validation | Test updated model against independent experimental data | Cross-validation with unused phenotypic data; Comparison of predictive accuracy | Quantified improvement in phenotype prediction accuracy |

Machine Learning Approaches for Gap Resolution

Recent advances in deep learning architectures have enabled new approaches for identifying missing reactions based solely on network topology, without requiring phenotypic data. The CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) method exemplifies this approach, using hypergraph learning to predict missing reactions by analyzing patterns in metabolic network structure [5]. The algorithm employs:

- Feature initialization through encoder-based neural networks

- Feature refinement using Chebyshev spectral graph convolutional networks

- Pooling operations to integrate metabolite-level features

- Scoring networks to predict reaction existence probabilities

This method demonstrated superior performance in recovering artificially removed reactions across 926 GEMs compared to previous topology-based approaches, achieving higher AUROC scores and improving phenotypic predictions for draft reconstructions [5].

Figure 2: CHESHIRE Workflow for Topology-Based Gap Prediction. The method uses deep learning on metabolic hypergraphs to identify missing reactions without experimental data, addressing over-optimism in draft models.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Gap Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Gap Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHESHIRE | Deep learning algorithm | Predicts missing reactions from network topology | Identifies knowledge gaps without experimental data; resolves overly optimistic predictions | [5] |

| CarveMe | Reconstruction pipeline | Top-down model creation from universal template | Automates draft reconstruction with built-in gap-filling; prioritizes reactions with genetic evidence | [16] |

| ModelSEED | Web resource | Automated model reconstruction and analysis | Provides probabilistic gap-filling using likelihood-based reaction annotations | [16] |

| RAVEN Toolbox | MATLAB-based framework | Metabolic reconstruction and curation | Integrates multiple databases for gap resolution; supports template-based gap-filling | [16] |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase | Curated metabolic reconstruction database | Reference for reaction addition during gap-filling; provides standardized biochemical data | [5] |

| AGORA | Model resource | Standardized microbial GEMs | Reference for comparative gap identification in related organisms | [5] |

Network gaps in genome-scale metabolic reconstructions systematically produce overly optimistic phenotype predictions that can misdirect research efforts and resource allocation in metabolic engineering and drug development. The mechanistic basis for this optimism stems from disrupted network topology that forces computational simulations to utilize biologically impossible pathways, incorrect gene essentiality predictions due to missing isozymes, and incomplete biomass definitions that fail to account for essential metabolic requirements.

Addressing this challenge requires both methodological awareness and practical strategies. Researchers should recognize that all draft GEMs contain gaps that bias predictions, implement systematic gap identification protocols as standard practice, apply multiple complementary gap-filling approaches (both optimization-based and machine learning), and maintain healthy skepticism of model predictions that lack experimental validation. As machine learning methods like CHESHIRE advance, the ability to identify and correct gaps prior to experimental data collection will significantly improve model reliability, ultimately strengthening the utility of GEMs across biological research and biotechnology applications.

Stoichiometric genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) have become indispensable tools for predicting cellular physiology and metabolic engineering. However, these models possess fundamental limitations due to their inherent static nature and inability to represent proteome allocation constraints and kinetic regulations. This whitepaper examines these limitations through the lens of network gaps—missing knowledge in metabolic reconstructions—and explores how integrating proteomic and kinetic constraints can address these critical shortcomings. We present quantitative comparisons of constraint-based methods, detailed experimental protocols for gap identification, and visual frameworks for understanding the hierarchical relationship between different modeling approaches in systems biology.

Network gaps represent critical knowledge deficiencies in genome-scale metabolic reconstructions that impair their predictive accuracy and biological relevance. These gaps manifest as missing reactions, incomplete pathway annotations, and incorrect gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations that collectively compromise model functionality [5] [17]. The reconstruction of high-quality GEMs is typically labor-intensive, spanning from six months for well-studied bacteria to two years for complex organisms like humans [17]. Despite rigorous curation efforts, even highly curated GEMs contain knowledge gaps that must be addressed through computational gap-filling methods [5].

The presence of network gaps creates functional interruptions in metabolic pathways that prevent models from simulating known physiological functions. These gaps often result from incomplete genomic annotations, limited organism-specific biochemical data, and insufficient understanding of transport reactions [1] [17]. The manual reconstruction process involves multiple stages including draft reconstruction, network refinement, data integration, and model validation, with each stage presenting opportunities for gaps to be introduced or perpetuated [17]. Understanding the nature and impact of these gaps is essential for advancing metabolic modeling capabilities.

Fundamental Limitations of Stoichiometric Models

Static Network Representation

Traditional stoichiometric models employ a static biochemical network representation that fails to capture the dynamic reorganization of metabolic pathways in response to environmental perturbations. These models utilize a stoichiometric matrix (S) where reactions are represented as columns and metabolites as rows, enabling constraint-based analysis methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [17]. While this approach successfully predicts steady-state flux distributions, it cannot represent metabolic transients, regulatory rewiring, or cellular differentiation processes that characterize real biological systems.

The static nature of these models presents particular limitations when simulating disease progression or developmental processes where metabolic networks undergo programmed reorganization. For metabolic engineers, this limitation manifests as an inability to predict how engineered pathways will behave across different growth phases or under varying bioreactor conditions. The fundamental assumption of pseudo-steady state for metabolic concentrations becomes invalid in rapidly changing environments where metabolic channeling and substrate-level regulation dominate cellular responses.

Absence of Proteome Allocation Constraints

Stoichiometric models traditionally lack proteome allocation constraints, creating a critical disconnect between metabolic predictions and cellular reality. As demonstrated in recent studies of bacterial translation machinery, optimal cellular function requires precise allocation of proteomic resources among enzymes, ribosomes, and supporting factors [18]. The failure to incorporate these constraints leads to unrealistic predictions of metabolic capabilities, including:

- Overestimation of pathway fluxes that would require enzymatically impossible protein concentrations

- Inability to predict trade-offs between different metabolic functions competing for ribosomal resources

- Violation of measured growth laws governing relationships between protein synthesis and growth rate [18]

The integration of proteome allocation constraints introduces fundamental trade-offs between enzyme production and metabolic output. For example, in the bacterial translation system, the optimal abundance of translation factors relative to ribosomes emerges from maximizing ribosomal usage while accounting for the proteomic cost of factor production [18]. This optimization problem yields analytical solutions where optimal enzyme concentrations depend on simple biophysical parameters like diffusion constants and protein sizes, rather than detailed kinetic parameters [18].

Lack of Kinetic and Thermodynamic Constraints

The omission of enzyme kinetic parameters and thermodynamic constraints represents another critical limitation of traditional stoichiometric models. Without Michaelis-Menten constants, inhibition coefficients, and enzyme capacity limits, FBA predicts physiologically impossible flux distributions that exceed the catalytic capacity of available enzymes. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when modeling:

- Metabolic congestion in overexpressed pathways

- Substrate channeling and metabolite compartmentalization

- Allosteric regulation that modulates pathway activity

- Thermodynamically infeasible flux directions under physiological conditions

Recent approaches have begun incorporating kinetic and thermodynamic constraints through flux sampling methods and differential flux analysis, but these extensions remain computationally challenging for genome-scale models. The absence of kinetic parameters for most enzymes in most organisms continues to limit practical implementation of these advanced modeling frameworks.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Constraint-Based Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Constraints Incorporated | Network Gap Impact | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static FBA | Stoichiometry, Exchange bounds | High | Low |

| FBA with ME-model | Stoichiometry, Proteome allocation | Medium | Medium-High |

| Dynamic FBA | Stoichiometry, Dynamic inputs | Medium | Medium |

| Kinetic Models | Stoichiometry, Enzyme kinetics | Low | High |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol for Identifying Network Gaps

Identifying network gaps requires systematic analysis of metabolic network content and connectivity. The following protocol, adapted from established reconstruction methodologies [17], provides a comprehensive approach for gap identification:

Dead-End Metabolite Analysis: Identify metabolites that cannot be produced or consumed due to missing reactions using computational tools like the COBRA Toolbox gapAnalysis program [1] [17]. These dead-end metabolites indicate gaps in pathway connectivity.

Growth Capability Assessment: Test model predictions against experimentally observed growth phenotypes on different nutrient sources. Inability to grow on known carbon sources indicates possible gaps in transport or pathway reactions [1].

Gene Essentiality Comparison: Compare computational gene essentiality predictions with experimental mutant screens. Discrepancies where knockouts grow in experiments but not in simulations suggest missing isozymes or alternative pathways [1].

Mass and Charge Balance Verification: Check all reactions for elemental and charge balance using checkMassChargeBalance programs. Unbalanced reactions indicate incomplete biochemical knowledge [17].

Pathway Completion Analysis: Verify production of all biomass components through metabolic pathways. Gaps preventing biomass production must be filled to create functional models [1].

For automated gap-filling, machine learning approaches like CHESHIRE can predict missing reactions using hypergraph learning based solely on metabolic network topology, requiring no experimental data input [5]. This method has demonstrated superior performance in recovering artificially removed reactions across 926 GEMs compared to existing topology-based methods [5].

Protocol for Incorporating Proteome Constraints

Integrating proteome allocation constraints extends traditional FBA to create more realistic models. The following protocol implements proteome-constrained models:

Define Proteome Sectors: Partition the proteome into metabolic enzymes (M), ribosomes (R), and other proteins (Q) following established growth law formulations [18]. The total proteome allocation follows the constraint: φM + φR + φQ = 1.

Formulate Catalytic Constraints: For each enzyme-catalyzed reaction, add a constraint linking flux (v) to enzyme concentration (E): v ≤ kcatE, where kcat is the turnover number.

Implement Ribosome Capacity Constraints: Relate protein synthesis rate to ribosome concentration following: λ = φriboact / (τtl⟨ℓ⟩ℓribo), where τtl is the translation cycle time, ⟨ℓ⟩ is the average protein length, and ℓribo is ribosomal protein length [18].

Solve Optimization Problem: Maximize growth rate (λ) subject to stoichiometric, capacity, and proteome allocation constraints using linear or quadratic programming.

This formulation successfully predicts conserved stoichiometry among translation factors in bacteria, demonstrating that optimal enzyme abundances emerge from proteomic trade-offs [18].

Figure 1: Hierarchical relationship between modeling frameworks showing how advanced models integrate multiple constraint types to overcome limitations of traditional stoichiometric approaches.

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Metabolic Reconstruction and Gap Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotation | RAST [1], NCBI Entrez Gene [17] | Automated genome annotation and gene identification |

| Biochemical Databases | KEGG [17], BRENDA [17], ModelSEED [1] | Reaction kinetics, metabolic pathways, enzyme information |

| Transport Databases | Transport DB [17], TCDB [1] | Transporter classification and annotation |

| Reconstruction Software | COBRA Toolbox [17], CarveMe [5] | Metabolic network reconstruction and simulation |

| Gap-Filling Tools | CHESHIRE [5], FastGapFill [5] | Computational prediction of missing reactions |

| Organism-Specific Databases | Ecocyc [17], PubChem [17] | Species-specific metabolic information |

Case Studies and Applications

Streptococcus suis Metabolic Reconstruction

The reconstruction of a genome-scale metabolic model for Streptococcus suis (iNX525) demonstrates practical approaches to addressing network gaps in pathogen metabolism [1]. This manually curated model included 525 genes, 708 metabolites, and 818 reactions, achieving a 74% MEMOTE quality score [1]. Key gap-filling strategies included:

- Homology-Based Gap Filling: Using Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pyogenes as template strains for identifying missing reactions through sequence similarity (BLAST identity ≥40%, match lengths ≥70%) [1].

- Biomass Composition Integration: Adopting and adapting macromolecular composition from phylogenetically related organisms (Lactococcus lactis) when species-specific data was unavailable [1].

- Physiological Validation: Testing model predictions against experimental growth phenotypes under different nutrient conditions, achieving 71.6-79.6% agreement with gene essentiality predictions from mutant screens [1].

This reconstruction identified 131 virulence-linked genes, with 79 genes participating in 167 metabolic reactions, enabling systematic analysis of relationships between growth and virulence pathways [1].

Machine Learning for Gap-Filling

The CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) method represents a recent advancement in computational gap-filling using deep learning to predict missing reactions based solely on metabolic network topology [5]. This approach:

- Utilizes Hypergraph Learning: Represents metabolic networks as hypergraphs where reactions connect multiple metabolites, preserving higher-order information lost in graph approximations [5].

- Outperforms Existing Methods: Demonstrates superior performance in recovering artificially removed reactions across 926 GEMs compared to NHP and C3MM methods [5].

- Improves Phenotypic Predictions: Enhances accuracy of fermentation product and amino acid secretion predictions in 49 draft GEMs from CarveMe and ModelSEED pipelines [5].

This topology-based approach is particularly valuable for non-model organisms where experimental data is scarce, enabling rapid curation of draft models before phenotypic data becomes available [5].

Figure 2: Network gap identification methodologies and their impact on model predictive capability, showing the relationship between different identification approaches and their consequences.

The limitations of stoichiometric models present significant challenges for metabolic engineering and systems biology research. Network gaps—manifesting as missing reactions, incorrect annotations, and incomplete pathway knowledge—fundamentally constrain predictive accuracy. The integration of proteome allocation constraints and kinetic parameters represents a promising path toward more biologically realistic models.

Machine learning approaches like CHESHIRE offer powerful tools for addressing knowledge gaps, particularly for non-model organisms where experimental data is limited [5]. Similarly, proteome-constrained models successfully predict optimal enzyme abundances from basic biophysical principles, providing insights into evolutionary optimization of metabolic systems [18]. Future advances will require tighter integration of experimental data with computational frameworks, development of automated curation tools, and creation of standardized validation protocols across diverse organisms.

As metabolic reconstruction methodologies mature, the systematic addressing of network gaps through integrated computational and experimental approaches will enhance drug target identification, metabolic engineering strategies, and fundamental understanding of cellular physiology across diverse biological systems.

Advanced Techniques and Tools for Identifying and Filling Metabolic Gaps

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational tools that collect all known metabolic information of a biological system, including genes, enzymes, reactions, associated gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules, and metabolites [9]. These networks provide a mathematical framework for simulating metabolism and predicting cellular phenotypes. The reconstruction of a high-quality GEM is a meticulous process that involves integrating genomic, biochemical, and physiological data [19]. However, a common challenge during reconstruction is the occurrence of network gaps—metabolic functions that are known to exist in the organism but are missing from the model due to incomplete genetic annotation or biochemical knowledge [20]. These gaps disrupt metabolic connectivity, preventing the model from producing essential biomass precursors or explaining observed physiological behavior, thereby limiting its predictive accuracy and utility in research and drug development.

The presence of gaps indicates inconsistencies between experimental observations and in silico predictions. For instance, a model might fail to simulate growth on a particular carbon source that the organism is known to utilize, or it might be unable to synthesize an essential biomass component under defined conditions [19]. Identifying and resolving these gaps is therefore a critical step in model curation, transforming an initial draft reconstruction into a high-quality, predictive tool. Traditional optimization-based gap-filling provides a systematic, computational approach to address this issue by proposing biologically plausible solutions that restore metabolic functionality.

Principles of Optimization-Based Gap-Filling

Core Conceptual Framework

Optimization-based gap-filling operates on the principle of parsimony, seeking the minimal set of biochemical reactions that must be added to a draft metabolic network to enable a defined metabolic function, such as growth or production of a target metabolite [19]. The process fundamentally relies on constraint-based modeling, which uses the stoichiometric matrix S of the metabolic network to define mass-balance constraints on the system [19]. The core mass-balance equation is: [ \sumj S{ij} vj = 0 ] where ( S{ij} ) is the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j, and ( v_j ) is the flux of reaction j.

When a model contains gaps, this system of equations has no solution for a biologically desired objective (e.g., biomass production). Gap-filling resolves this by expanding the model's reaction set, introducing candidate reactions from a biochemical database until the desired metabolic function becomes feasible. The solution is found by solving a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem that minimizes the number of added reactions while satisfying all constraints.

Key Mathematical Formulations

The primary gap-filling optimization problem can be formulated as follows:

Objective: [ \min \sum{j \in R{cand}} y_j ]

Subject to: [ \sumj S{ij} vj = 0 \quad \forall i \in M ] [ vj^{min} \leq vj \leq vj^{max} \quad \forall j \in R{model} \cup R{cand} ] [ v{biomass} \geq v{biomass}^{target} ] [ vj - yj \cdot vj^{min} \geq 0 \quad \forall j \in R{cand} ] [ vj - yj \cdot vj^{max} \leq 0 \quad \forall j \in R{cand} ] [ yj \in {0,1} \quad \forall j \in R{cand} ]

Where:

- ( R_{cand} ) is the set of candidate reactions for addition

- ( R_{model} ) is the set of reactions in the current model

- ( M ) is the set of metabolites

- ( y_j ) is a binary variable indicating whether candidate reaction j is added

- ( v_{biomass} ) is the flux of the biomass reaction

- ( v_{biomass}^{target} ) is the minimum required biomass flux

Table 1: Key Components of the Gap-Filling Optimization Framework

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | ( S_{ij} ) | Matrix of stoichiometric coefficients | Defines mass-balance constraints for the system |

| Reaction Flux | ( v_j ) | Continuous variable representing metabolic flux through reaction j | Must satisfy bounds and mass balance |

| Binary Selection Variable | ( y_j ) | Binary variable (0 or 1) for each candidate reaction | Determines whether reaction j is added to the model |

| Candidate Reaction Set | ( R_{cand} ) | Database of possible reactions to add | Source of potential solutions to fill metabolic gaps |

| Biomass Flux Constraint | ( v_{biomass} ) | Flux through biomass reaction | Sets minimum required level of metabolic functionality |

Workflow for Traditional Optimization-Based Gap-Filling

Comprehensive Gap-Filling Procedure

The following workflow outlines the standard methodology for performing optimization-based gap-filling in genome-scale metabolic models:

Step 1: Model Validation and Gap Identification

- Test the model's ability to produce all essential biomass precursors under appropriate growth conditions

- Verify production of known metabolic by-products (e.g., organic acids) [19]

- Check substrate utilization capabilities against experimental data [21]

- Identify specific blocked metabolites and pathways through pathway analysis

Step 2: Compilation of Candidate Reaction Database

- Create a comprehensive database of biochemical reactions from sources like KEGG and Biocyc [19]

- Include reactions from related organisms with similar metabolic capabilities

- Annotate reactions with gene-protein-reaction associations where possible

Step 3: Formulate Gap-Filling Optimization Problem

- Define the biological objective (e.g., biomass production > 0)

- Set environmental constraints (available nutrients, oxygen conditions)

- Specify candidate reaction bounds (reversibility, flux constraints)

- Configure the optimization solver (e.g., COBRA Toolbox) [19]

Step 4: Solve and Evaluate Proposed Solutions

- Execute the MILP optimization to find minimal reaction additions

- Generate multiple alternative solutions when applicable

- Rank solutions by biological plausibility and genomic evidence

- Evaluate flux variability of added reactions

Step 5: Experimental Validation and Model Refinement

- Test gap-filled model predictions against experimental growth data [21]

- Use gene essentiality analysis to verify added reactions [19]

- Perform manual curation of added pathways

- Iterate process until model achieves desired predictive accuracy

Figure 1: Optimization-based gap-filling workflow for genome-scale metabolic models

Specialized Gap-Filling Scenarios

Different types of metabolic gaps require specialized gap-filling approaches:

Type 1: Growth-Supporting Gap-Filling

- Objective: Enable biomass production under specific nutrient conditions

- Application: Essential for creating models that accurately simulate cell growth

- Validation: Compare predicted growth rates with experimental measurements [21]

Type 2: Metabolic Capability Gap-Filling

- Objective: Restore ability to utilize specific carbon sources or produce known metabolites

- Application: Improves model accuracy for specific environmental conditions

- Example: Adding transport reactions for carbon sources like maltose, glucose, and lactate [19]

Type 3: Biosynthetic Pathway Gap-Filling

- Objective: Enable synthesis of complex metabolites (e.g., amino acids, cofactors)

- Application: Critical for modeling autonomous growth without rich medium supplementation

- Method: Often requires adding multiple consecutive reactions to complete pathways

Table 2: Gap-Filling Algorithms and Their Applications

| Algorithm/Approach | Primary Optimization Method | Typical Application Context | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GapFill | Linear Programming (LP) | General gap-filling for growth and metabolic function | Fast computation; finds minimal reaction sets | May propose thermodynamically infeasible solutions |

| GrowMatch | MILP with phenotypic data | Integrating mutant growth phenotype data | Incorporates multiple experimental conditions | Requires extensive experimental data |

| MetaGapFill | Context-specific LP | Microbial community modeling | Conserves community metabolic interactions | Complex formulation for multi-species systems |

| SMILEY | MILP with isotopic labeling | Gap-filling validated by ¹³C tracing data | High confidence in proposed solutions | Experimentally intensive validation |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Model Validation Using Substrate Utilization Assays

A critical validation step for gap-filled models involves testing predictions against experimental substrate utilization data:

Protocol: BIOLOG Phenotype MicroArray Assay

- Culture Preparation: Grow P. stutzeri A1501 cultures to mid-exponential phase in defined minimal medium [21]

- Sample Inoculation: Transfer bacterial suspension to BIOLOG plates containing 71 different carbon sources

- Incubation: Incubate plates at 30°C for 24-48 hours under appropriate atmospheric conditions

- Data Collection: Measure colorimetric changes indicating substrate utilization every 24 hours

- Model Validation: Compare experimental results with model predictions for each carbon source

Quantitative Analysis:

- Calculate prediction accuracy as (True Positives + True Negatives) / Total Substrates

- A high-quality model should achieve ≥90% accuracy in predicting substrate utilization [21]

Gene Essentiality Analysis for Gap-Filling Validation

Gene essentiality analysis provides orthogonal validation of gap-filled models:

Computational Protocol:

- Simulation Setup: Constrain model to specific growth conditions (e.g., glucose minimal medium)

- Gene Knockout: For each gene g in the model, constrain all associated reaction fluxes to zero

- Growth Simulation: Calculate maximal biomass production rate for the mutant

- Classification: Classify gene g as essential if in silico growth rate is zero

- Validation: Compare predictions with experimental gene essentiality data when available

Interpretation:

- Correct prediction of essential genes validates completeness of metabolic pathways

- False predictions may indicate remaining gaps or incorrect pathway annotations

- This analysis can be performed using the COBRA Toolbox [19]

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Model Gap-Filling

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Database | Primary Function in Gap-Filling | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | KEGG, BioCyc | Source of candidate reactions and pathway information | Draft reconstruction and gap-filling candidate identification [19] |

| Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox | Primary platform for constraint-based analysis and gap-filling | Performing optimization-based gap-filling simulations [19] |

| Metabolic Databases | ModelSEED, BiGG Models | Curated biochemical reaction databases | Standardizing reaction notation and retrieving thermodynamic data |

| Experimental Validation | BIOLOG Phenotype MicroArrays | High-throughput substrate utilization profiling | Validating model predictions against experimental growth data [21] |

| Sequence Analysis | BLASTp, HMMER | Identifying putative enzymes for candidate reactions | Providing genomic evidence for proposed gap-filling solutions [19] |

| Pathway Analysis | Pathway Tools, MetaCyc | Visualizing metabolic pathways and identifying gaps | Manual curation and hypothesis generation for missing pathways |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Multi-Omics Data

Multi-Strain and Community Modeling Applications

Optimization-based gap-filling extends beyond single organisms to support advanced modeling paradigms:

Pan-Genome Metabolic Modeling:

- Concept: Create metabolic models that represent multiple strains of a species

- Method: Develop a "core" model (shared reactions) and "pan" model (union of all reactions) [9]

- Application: Understanding metabolic diversity across bacterial isolates

- Example: 55 individual E. coli GEMs integrated into a multi-strain model [9]

Microbial Community Metabolic Modeling:

- Challenge: Resolving gaps becomes more complex with multiple interacting organisms

- Approach: Community-level gap-filling that considers metabolic interactions

- Significance: Essential for modeling host-associated microbiomes and environmental communities [20]

Integration with Omics Data for Context-Specific Gap-Filling

High-throughput omics data provides additional constraints for gap-filling:

Transcriptomics Integration:

- Use RNA-seq data to identify expressed metabolic genes

- Constrain model reactions based on expression levels

- Perform context-specific gap-filling for particular environmental conditions

Metabolomics Integration:

- Validate gap-filled pathways by detecting predicted metabolites

- Use mass spectrometry data to identify blocked metabolic steps

- Constrain model using measured extracellular exchange fluxes

Fluxomics Integration:

- Incorporate ¹³C metabolic flux analysis data

- Validate predictions of internal flux distributions in gap-filled models

- Refine gap-filling solutions based on experimental flux measurements [9]

Figure 2: Integration of multi-omics data for context-specific metabolic model gap-filling

Traditional optimization-based gap-filling remains an essential methodology in the development of high-quality genome-scale metabolic models. By systematically identifying and resolving network gaps through mathematical optimization, this approach enables the creation of computational models that accurately represent an organism's metabolic capabilities. The integration of experimental validation with computational predictions creates an iterative refinement process that enhances model quality and biological relevance. As metabolic modeling expands to include multi-strain systems and complex microbial communities, optimization-based gap-filling will continue to play a crucial role in ensuring these models faithfully represent metabolic networks, thereby supporting their application in basic research, biotechnology, and drug development.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are mathematical representations of the metabolic network of an organism, encapsulating the relationships between genes, proteins, and biochemical reactions [22] [15]. These models serve as powerful platforms for predicting cellular phenotypes, guiding metabolic engineering, and identifying potential drug targets [22] [23]. However, a fundamental limitation plaguing even the most sophisticated GEMs is the presence of network gaps—missing reactions that disrupt metabolic pathways and lead to inaccurate phenotypic predictions [5] [15].

These gaps arise from imperfect genome annotation, incomplete biochemical knowledge, and sequence-to-function mapping uncertainties [24] [15]. The process of "gap-filling" has traditionally relied on optimization-based methods that require experimental phenotypic data to identify and resolve inconsistencies between model predictions and observed growth profiles [5]. For non-model organisms or newly sequenced species, such data is often unavailable, creating a significant bottleneck in the construction of high-quality metabolic models [5]. This context sets the stage for the emergence of a new paradigm: topology-based machine learning methods that can predict missing reactions directly from the structure of the metabolic network itself, without dependency on experimental data.

Understanding Network Gaps and Their Impact on GEM Quality

Origins and Consequences of Gaps

Network gaps in GEMs originate from several sources. Incomplete genome annotation is a primary cause, where genes are incorrectly assigned or remain unidentified, leading to missing enzyme functions in the network [15]. Furthermore, databases contain misannotations, and many enzyme functions are "orphan" activities that cannot yet be mapped to a specific gene sequence [15]. The presence of gaps creates dead-end metabolites—compounds that the model can produce but not consume, or vice versa—which disrupt the flow of metabolites through the network and impair the model's predictive capability [5].

Traditional Gap-Filling Approaches and Their Limitations

Traditional gap-filling methods, such as those implemented in tools like gapseq, typically use Linear Programming (LP)-based algorithms that identify a minimal set of reactions to add from a universal database to enable specific metabolic functions, such as biomass production on a given medium [24]. While effective, these approaches have significant limitations:

- Medium dependency: The reactions added are heavily biased toward the specific growth medium used for gap-filling [24].

- Lack of generalizability: Models gap-filled for one condition may not perform well under different environmental contexts [24].

- Experimental data requirement: Most optimization-based methods need phenotypic data as input to identify model-data inconsistencies [5].

These limitations are particularly problematic for non-model organisms, where experimental data is scarce, creating a pressing need for more versatile gap-filling approaches.

CHESHIRE: A Paradigm Shift in Topology-Based Gap-Filling

Conceptual Foundation and Hypergraph Representation

CHESHIRE (CHEbyshev Spectral HyperlInk pREdictor) represents a groundbreaking approach that frames the problem of identifying missing reactions as a hyperlink prediction task on a hypergraph [5]. Unlike traditional graphs where edges connect pairs of nodes, hypergraphs allow hyperlinks (reactions) to connect multiple nodes (metabolites) simultaneously, providing a more natural representation of metabolic networks where reactions typically involve multiple substrates and products [5].

The core innovation of CHESHIRE lies in its ability to learn the topological signatures of known metabolic reactions and use these patterns to predict missing links in the network. By leveraging the inherent structure of the metabolic network, CHESHIRE can propose biologically plausible candidate reactions without requiring experimental phenotype data as input [5].

Architectural Framework and Workflow

CHESHIRE's deep learning architecture consists of four major computational steps [5]:

- Feature Initialization: An encoder-based neural network generates initial feature vectors for each metabolite from the incidence matrix of the hypergraph, encoding crude topological relationships between metabolites and reactions.

- Feature Refinement: A Chebyshev Spectral Graph Convolutional Network (CSGCN) refines the feature vectors by incorporating information from neighboring metabolites within the same reaction, capturing metabolite-metabolite interactions.

- Pooling: Graph coarsening methods integrate metabolite-level features into reaction-level representations using both maximum minimum-based and Frobenius norm-based pooling functions.

- Scoring: A final neural network layer produces probabilistic scores indicating the confidence of each candidate reaction's existence in the target organism's metabolic network.

The diagram below illustrates CHESHIRE's workflow for predicting missing reactions in a metabolic network:

Experimental Validation and Performance Benchmarking

CHESHIRE has undergone rigorous validation through both internal tests with artificially introduced gaps and external assessments using real-world phenotypic predictions [5].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Topology-Based Gap-Filling Methods on BiGG Models

| Method | AUROC | Precision | Recall | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHESHIRE | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.80 | Chebyshev Spectral GCN + Dual Pooling |

| NHP (Neural Hyperlink Predictor) | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.75 | Graph Approximation of Hypergraphs |

| C3MM (Clique Closure) | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.72 | Integrated Training-Prediction |

| Node2Vec-Mean (Baseline) | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.68 | Random Walk Embeddings |

In internal validation tests conducted on 108 high-quality BiGG models, CHESHIRE significantly outperformed existing state-of-the-art methods across all classification metrics [5]. The internal validation involved systematically removing known reactions from GEMs and evaluating each method's ability to correctly identify them as missing from a pool of candidate reactions [5].

For external validation, CHESHIRE was tested on 49 draft GEMs reconstructed using automated pipelines (CarveMe and ModelSEED). The method demonstrated a remarkable capability to improve theoretical predictions of fermentation product secretion and amino acid production, confirming that the topology-based predictions translate to enhanced phenotypic forecasting [5].

Comparative Analysis: CHESHIRE in the Context of Other Machine Learning Approaches

Topology-Based Gene Essentiality Prediction

The success of topology-based approaches extends beyond gap-filling to other critical applications like gene essentiality prediction. A recent study demonstrated that a machine learning model using graph-theoretic features (betweenness centrality, PageRank) significantly outperformed traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) in predicting essential metabolic genes in E. coli [25]. The topology-based model achieved an F1-score of 0.400, while FBA failed to identify any known essential genes correctly [25].

Integrative Machine Learning Frameworks