Building a Better Factory: Engineering Genome-Reduced Microbial Chassis for Heterologous Natural Product Production

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic deletion of native biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) to create optimized heterologous production chassis.

Building a Better Factory: Engineering Genome-Reduced Microbial Chassis for Heterologous Natural Product Production

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the strategic deletion of native biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) to create optimized heterologous production chassis. It covers the foundational rationale for removing competing metabolic pathways, detailed methodologies for chassis construction across diverse bacterial hosts like Streptomyces and Burkholderiales, advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques to enhance product titers, and rigorous validation frameworks for comparative chassis performance. By synthesizing recent advances, this guide aims to facilitate the efficient discovery and scalable production of novel microbial natural products, directly addressing critical bottlenecks in modern drug discovery pipelines.

The 'Why': Foundational Principles of Native BGC Deletion in Chassis Development

Microbial natural products (NPs) have historically been a cornerstone of modern medicine, providing the foundation for countless therapeutic agents. These compounds are typically biosynthesized by enzymes encoded by biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Genomic sequencing reveals that a typical microbial genome possesses 20-40 BGCs; however, the products of most identifiable BGCs remain undetected under standard laboratory conditions, creating a significant discrepancy between biosynthetic potential and measurable NP output [1]. These inactive clusters are termed silent or cryptic BGCs [1]. Unlocking this "silent majority" represents one of the most promising frontiers for novel drug discovery, particularly as drug resistance becomes an increasingly serious global problem [2].

A critical strategy for accessing these cryptic metabolites is heterologous expression, which involves cloning and expressing BGCs from their native producer into a specialized, tractable host strain [2] [1]. This approach provides a shortcut to pathway modification, metabolic optimization, and yield improvement [2]. A foundational step in developing a potent heterologous production chassis is the deletion of native, non-essential BGCs. This serves to streamline host metabolism, minimize precursor competition, and eliminate the production of native metabolites that can interfere with the detection and isolation of the target compound [3] [4]. This application note details protocols and strategies for creating such chassis and activating silent BGCs, framed within the context of a broader thesis on chassis engineering.

Experimental Protocols: Constructing a Specialized Chassis

Protocol 1: Development of a VersatileStreptomycesChassis

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, outlines the creation of Streptomyces aureofaciens Chassis2.0, designed for the efficient production of diverse type II polyketides (T2PKs) [3].

- Objective: To develop a high-yielding Streptomyces chassis by removing competing native BGCs to enhance precursor availability and compatibility for heterologous T2PK production.

- Materials:

- Methodology:

- Chassis Selection: Select a high-yielding industrial strain as a starting host based on its demonstrated capacity for producing the class of molecules of interest. In this case, S. aureofaciens J1-022 was chosen for its high T2PK production [3].

- BGC Identification: Use genome mining tools (e.g., antiSMASH) to identify the native T2PK BGCs within the J1-022 genome [3].

- In-Frame Deletion: Execute precise, in-frame deletions of two endogenous T2PK gene clusters. This step is crucial to mitigate competition for intracellular precursors such as malonyl-CoA [3].

- Phenotypic Validation: Confirm the successful deletion by observing a "pigmented-faded" phenotype in the resulting host, designated Chassis2.0, indicating the cessation of native pigment production [3].

- Heterologous Expression: Clone the target BGC (e.g., the oxytetracycline cluster from S. rimosus) into an E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle plasmid using ExoCET and introduce it into Chassis2.0 for production [3].

- Key Outcomes: The resulting Chassis2.0 demonstrated a 370% increase in oxytetracycline production compared to conventional commercial strains and successfully produced tri-ring T2PKs (e.g., actinorhodin) and activated a previously silent pentangular T2PK BGC, leading to the discovery of a novel compound, TLN-1 [3].

Protocol 2: Activation of Silent BGCs via Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS)

RGMS is a powerful endogenous strategy for activating silent BGCs in their native host, combining classical genetics with modern detection methods [1].

- Objective: To generate and screen mutant libraries for strains that express a targeted silent BGC.

- Materials:

- Reporter Construct: A plasmid containing a promoterless fluorescent protein gene (e.g., GFP) or a selectable marker gene (e.g., antibiotic resistance).

- Mutagenesis Tool: UV light or a transposon (Tn) system for random mutagenesis.

- Analytical Tools: HPLC-MS and/or imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) for metabolite detection.

- Methodology:

- Reporter Integration: Fuse the promoter of the target silent BGC to a reporter gene (e.g., gfp or neo for kanamycin resistance) and integrate this construct into the native host's genome [1].

- Mutant Library Generation: Create a library of random mutants using either:

- UV Mutagenesis: Exposing the cell population to UV radiation.

- Transposon Mutagenesis: Using a Tn vector to create random insertions in the genome [1].

- Mutant Selection: Screen the mutant library for activation of the silent BGC using one of two methods:

- Reporter-Based Selection: Isolate mutants that exhibit strong fluorescence or increased antibiotic resistance, indicating upregulation of the BGC promoter [1].

- Metabolomics-Based Selection: Subject the mutant library to HPLC-MS analysis. Use data analytics (e.g., self-organizing maps) to identify mutants with unique metabolite profiles indicative of BGC activation [1].

- Hit Validation: Ferment the selected mutant strains and use advanced analytical chemistry (e.g., IMS, NMR) to isolate and characterize the newly produced cryptic metabolite.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points in the RGMS process.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of Host Performance

Heterologous Host Comparison for BGC Expression

Table 1: Comparative analysis of bacterial strains developed as heterologous hosts for natural product BGC expression.

| Heterologous Host | Genome Modifications | DNA Transfer Method | Biosynthetic Range Tested | Best Titer Achieved | Virulence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces aureofaciens Chassis2.0 [3] | Deletion of two endogenous T2PK clusters | Conjugation | Type II PKS (Tetracyclines, Angucyclines) | 370% increase in oxytetracycline vs. commercial strain | Laboratory strain |

| Burkholderia thailandensis E264 [2] | Δthailandepsin, Δefflux pumps | Conjugation, Electroporation | Polyketides (PKs), Non-Ribosomal Peptides (NRPs) | 985 mg/L (FK228 derivative) | Low virulence to humans/animals |

| Burkholderia gladioli ATCC 10248 [2] | Δgladiolin BGC | Conjugation, Electroporation | NRPs, PK-NRPs (hybrid compounds) | Not Reported | Plant pathogen |

| Escherichia coli MDS-205 [4] | Reduced genome (14.3% deleted), thrA*BC operon, Δtdh, ΔtdcC, ΔsstT, rhtA23 |

Electroporation | Primary metabolites (L-Threonine) | ~83% increase vs. engineered wild-type | Laboratory strain |

Strategies for Activating Silent Biosynthetic Gene Clusters

Table 2: Summary of primary methodologies for accessing the products of silent or cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters. [1]

| Method Category | Description | Key Techniques | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous: Classical Genetics | Manipulating the native host's genome to activate silent BGCs. | Reporter-Guided Mutant Selection (RGMS), Targeted gene knockouts. | Physiologically relevant; reveals native regulation. | Limited to culturable hosts; can be labor-intensive. |

| Endogenous: Chemical Genetics | Using small molecules to perturb cellular regulation. | Co-culture, Enzyme inhibitors, Elicitors. | Non-genetic; can induce multiple BGCs simultaneously. | Effects can be pleiotropic and difficult to deconvolute. |

| Endogenous: Culture Modalities | Altering physical and chemical growth conditions. | OSMAC (One Strain Many Compounds), variation in media, aeration, temperature. | Simple and low-cost; high-throughput potential. | Often unpredictable and inefficient for specific BGCs. |

| Exogenous: Heterologous Expression | Expressing the BGC in a foreign host. | BGC cloning in Streptomyces, Burkholderia, or E. coli. | Bypasses native regulation; simplifies engineering. | Technically challenging for large BGCs; host compatibility issues. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents, tools, and strains used in heterologous expression and silent BGC activation.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ExoCET Technology [3] | Facilitates the cloning and assembly of very large DNA fragments, such as entire BGCs, into shuttle vectors. | Used to clone the complete oxytetracycline BGC for heterologous expression. |

| ϕC31 Integrative Vectors [2] | A system for stable genomic integration of BGCs into the chromosome of actinobacterial hosts like Streptomyces or Burkholderia. | Enables stable maintenance and expression of large BGCs without plasmid loss. |

| antiSMASH Software [2] [1] | A bioinformatics platform for the genome-wide identification, annotation, and analysis of BGCs in microbial genomes. | Critical for the initial in-silico discovery of silent BGCs and for guiding chassis engineering. |

| Transposon Mutagenesis System [1] | A genetic tool for creating random insertional mutations in a genome, used for forward genetics screens like RGMS. | Used in Burkholderia spp. to identify regulatory genes that repress silent BGCs. |

| Constitutive & Inducible Promoters [2] | Genetic parts to drive the expression of BGC genes in heterologous hosts, independent of native regulation. | Examples: Constitutive Pgenta; Inducible araC/PBAD (L-arabinose) and rhaRS/PrhaB (L-rhamnose). |

| Reduced-Genome Chassis [4] | Host strains with non-essential genes removed to reduce metabolic burden and improve precursor flux for production. | E. coli MDS42; Streptomyces Chassis2.0. |

Integrated Strategy: From Genome Mining to Compound Discovery

Successfully addressing the problem of silent BGCs requires an integrated, multi-faceted approach. The initial step involves comprehensive genome mining using tools like antiSMASH to identify all potential BGCs within a strain of interest [1]. Following identification, researchers must choose between endogenous and exogenous activation strategies, a critical decision that depends on the tractability of the native host and the characteristics of the BGC itself [1].

For exogenous expression, the selection and optimization of a heterologous host is paramount. As demonstrated with Streptomyces Chassis2.0, this involves selecting a host with high native production capacity and then refining it by deleting competing native BGCs to create a clean, metabolically efficient background [3]. The choice of host should also consider phylogenetic proximity to the BGC's source organism to improve the likelihood of successful expression, as seen with the development of various Burkholderia hosts for expressing BGCs from the Burkholderiales order [2].

The logical flow from target selection to final compound discovery is summarized in the following diagram.

In the construction of microbial cell factories for heterologous production, metabolic burden is a critical challenge that arises from the rewiring of native metabolism. Defined as the impact of genetic manipulation and environmental perturbations on cellular resource distribution, this burden manifests as impaired cell growth, reduced fitness, and suboptimal product yields [5]. This is particularly relevant in the context of a research thesis focused on deleting native biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) to develop specialized heterologous production chassis. When a host organism is engineered to produce non-native compounds, competition for essential precursors, energy (ATP), and redox cofactors (NAD(P)H) between native and heterologous pathways creates substantial physiological stress [6] [7]. Effectively managing this burden is therefore paramount for developing robust and economically viable bioproduction platforms.

Key Concepts and Strategic Approaches

Fundamental Principles of Burden Mitigation

Metabolic burden originates from multiple sources during heterologous pathway expression. The core issue revolves around resource competition, where the introduced genetic elements and metabolic processes consume cellular resources that would otherwise support host growth and maintenance [5]. This includes the energetic cost of maintaining and replicating recombinant DNA, the metabolic drain of expressing heterologous enzymes, and the physical burden of pathway intermediates and final products [6].

Strategic approaches to alleviate this burden focus on rebalancing cellular metabolism through several key mechanisms:

- Precursor and Cofactor Balancing: Ensuring adequate supply of critical precursors like erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), while balancing redox cofactor regeneration [8].

- Dynamic Metabolic Control: Implementing regulatory systems that decouple growth and production phases to minimize fitness costs [5].

- Pathway Modularization: Optimizing different pathway modules independently before reintegrating them for balanced flux [9].

- Genome Reduction: Deleting non-essential native BGCs and competing pathways to free up cellular resources and precursors [10].

Quantitative Impact of Metabolic Burden

Table 1: Documented Effects of Metabolic Burden and Intervention Outcomes

| Host Organism | Engineering Intervention | Impact on Metabolic Burden/Fitness | Production Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus RN4220 | Acquisition of heterologous MP1 bacteriocin BGC | Immediate production but reduced growth rates (fitness cost) | 3-fold lower MP1 production compared to native producer | [6] |

| Staphylococcus aureus RN4220 (Adapted) | Prolonged cultivation; TCA cycle mutations | Enhanced metabolic fitness; relieved growth defect | Increased MP1 production levels | [6] |

| Streptomyces explomaris | Deletion of transcriptional repressors nybW and nybX | Relief of cluster repression | Increased nybomycin production | [8] |

| Streptomyces explomaris NYB-3B | Overexpression of precursor genes (zwf2, nybF) | Improved precursor and cofactor supply | 5-fold increase in nybomycin titer (57 mg L⁻¹) | [8] |

| Various Streptomyces sp. | CRISPR-Cas9-BD mediated multiplexed editing | Reduced cytotoxicity from off-target cleavage | Improved secondary metabolite production | [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Burden Assessment and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Transcriptomic Analysis for Identifying Bottlenecks

This protocol identifies transcriptional bottlenecks in a heterologous host using Streptomyces explomaris with a heterologous nybomycin BGC as a model [8].

Materials:

- RNA stabilization reagent (e.g., RNAlater)

- Cell disruption system (e.g., bead beater)

- RNA extraction and purification kit

- DNase I, RNase-free

- cDNA synthesis kit

- RNA-seq library preparation kit

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Cultivation and Sampling: Inoculate the production strain in an appropriate medium. Collect cell pellets from multiple time points covering growth (e.g., 17h) and production phases (e.g., 36h, 75h, 175h). Immediately stabilize RNA using RNAlater [8].

- RNA Extraction: Disrupt cells mechanically. Purify total RNA, ensuring removal of genomic DNA with DNase I treatment. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0 recommended).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Deplete ribosomal RNA. Synthesize cDNA and prepare sequencing libraries. Sequence on an Illumina platform to generate a minimum of 20 million paired-end reads per sample.

- Data Analysis: Map reads to the host genome and heterologous BGC. Identify differentially expressed genes (adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05, fold change ≥ 2) comparing production time points to the growth phase reference.

- Bottleneck Identification: Focus analysis on:

- Downregulation of key genes in precursor-supplying pathways (e.g., Pentose Phosphate Pathway, Shikimate pathway).

- Repression of heterologous BGC genes.

- Upregulation of stress response genes.

Expected Outcome: Identification of repressed metabolic steps and precursor limitations, such as the observed downregulation of zwf2 (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) limiting E4P and NADPH supply [8].

Protocol 2: CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated BGC Deletion in Streptomyces

This protocol details the use of an engineered, low-cytotoxicity Cas9-BD system for efficient deletion of native BGCs in high-GC Streptomyces to free resources [10].

Materials:

- pCRISPomyces-2BD plasmid (or similar with Cas9-BD)

- E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 as a donor strain for conjugation

- Target Streptomyces strain

- sgRNA design software

- Oligonucleotides for sgRNA template construction

- Apramycin antibiotic

- TES buffer (for protoplast transformation, if needed)

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design and Cloning: Design two sgRNAs targeting the flanking regions of the native BGC to be deleted. Clone these sgRNA expression cassettes into the pCRISPomyces-2BD plasmid [10].

- Donor Strain Preparation: Transform the constructed plasmid into the E. coli donor strain.

- Conjugation: Mix the E. coli donor with Streptomyces spores or mycelia. Plate on conjugation medium and incubate at 30°C for ~16 hours. Overlay with apramycin to select for exconjugants.

- Mutant Screening: Incubate plates until exconjugant colonies appear (typically 3-5 days). Screen for successful deletion via PCR across the deletion junction.

- Curing the Plasmid: Passage positive clones without antibiotic selection to lose the CRISPR plasmid.

Expected Outcome: Efficient deletion of target native BGC with significantly reduced off-target effects and cytotoxicity compared to wild-type Cas9, leading to a cleaner chassis background [10].

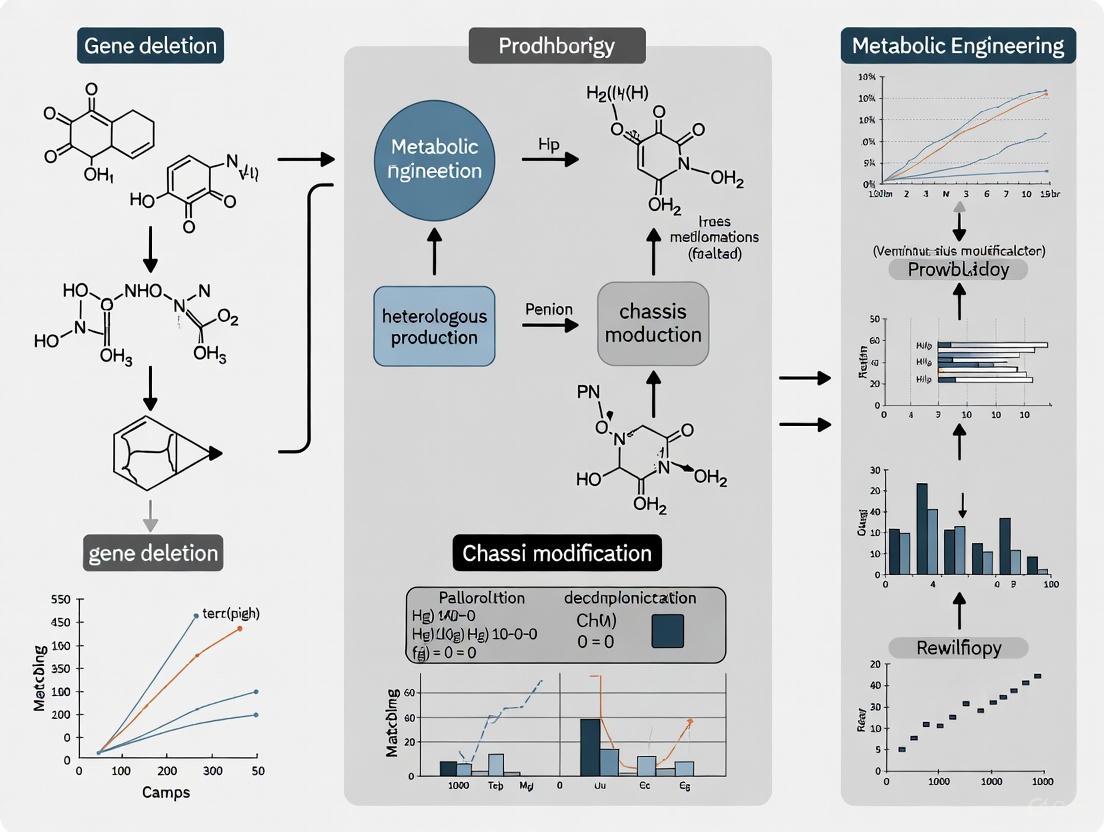

Visualizing Metabolic Engineering Workflows and Pathways

Logical Workflow for Building a Minimal-Chassis

This diagram visualizes the core strategy of using native BGC deletion to create a minimal-chassis for heterologous production.

Central Metabolism and Precursor Channeling

This diagram illustrates key metabolic pathways and precursors that become bottlenecks during heterologous production, and targets for engineering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Burden Research

| Reagent/Tool Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9-BD System | Genome editing with reduced off-target cleavage and cytotoxicity in high-GC hosts. | Efficient deletion of native BGCs in Streptomyces without detrimental fitness effects. | [10] |

| RNA-seq | Genome-wide transcriptional profiling to identify repression and bottleneck genes. | Identifying downregulated PPP and Shikimate pathway genes in S. explomaris. | [8] |

| Plasmid pD4-19 (MP1 BGC) | Model mobile genetic element carrying a bacteriocin gene cluster. | Studying fitness costs and metabolic adaptation post-BGC acquisition in S. aureus. | [6] |

| ESM-2 (Protein LLM) | Unsupervised machine learning model to predict functional protein variants. | Designing high-quality, diverse mutant libraries for enzyme engineering in autonomous workflows. | [11] |

| iBioFAB | Fully automated biofoundry for integrated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles. | Enabling high-throughput, autonomous strain engineering to optimize complex traits. | [11] |

In the field of heterologous production chassis research, a primary obstacle to the efficient discovery and high-yield production of novel natural products (NPs) is the complex native metabolome of host organisms. This inherent metabolic background creates significant analytical interference, complicating the detection, purification, and characterization of target compounds encoded by introduced biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [12]. Metabolic background interference arises from the host's endogenous secondary metabolites, which can mask the production of desired compounds, co-elute during chromatography, and consume essential biosynthetic precursors, thereby reducing pathway flux and final titers [13] [3].

The strategic deletion of native BGCs is therefore a cornerstone of chassis engineering. This process creates a cleaner metabolic background, which minimizes host-derived metabolites, streamlines downstream analytical processes, and redirects cellular resources toward the heterologous pathways of interest [13] [12]. This application note details the principles and protocols for creating such optimized microbial chassis, framed within the broader thesis that engineered minimal-background hosts are indispensable for unlocking the vast potential of cryptic BGCs discovered through modern genome mining.

The Rationale for a Clean Metabolic Background

Overcoming Analytical Challenges

The presence of native metabolites can severely hinder the detection of new compounds, especially those produced at low titers from silent or cryptic BGCs. A simplified metabolite profile facilitates the use of mass spectrometry and NMR for structural elucidation, increasing the sensitivity and reliability of detection methods [12].

Enhancing Metabolic Efficiency

Native BGCs compete with introduced pathways for essential intracellular precursors, such as acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, and amino acids. By removing these competing pathways, the cellular metabolism can be rewired to prioritize the production of the target heterologous product, often leading to substantial yield improvements [9] [3]. Furthermore, eliminating native pigments or compounds with antimicrobial activity can improve host fitness and fermentation performance [3].

Established and Emerging Microbial Chassis

The selection of an appropriate host is the first critical step. Ideal chassis are genetically tractable, have a rapid growth cycle, and are capable of supplying the necessary precursors for the target class of compound. The table below summarizes several engineered chassis strains with deleted native BGCs, highlighting their cleaned metabolic backgrounds.

Table 1: Engineered Microbial Chassis with Minimal Metabolic Background

| Chassis Strain | Parent Strain | Genetic Modifications | Key Advantages | Reported Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 [13] | S. coelicolor A3(2) | Deletion of four endogenous BGCs; introduction of multiple RMCE sites. | Defined metabolic background; high conjugation efficiency; supports multi-copy BGC integration. | Heterologous expression of xiamenmycin and griseorhodin BGCs [13]. |

| S. coelicolor M1152 [14] | S. coelicolor M145 | Deletion of four endogenous BGCs (act, red, ced, CDA). | Well-characterized; optimized for expression of secondary metabolites; visual pigment background removed. | Refactoring and expression of the actinorhodin BGC and its mutants [14]. |

| S. aureofaciens Chassis2.0 [3] | S. aureofaciens J1-022 | In-frame deletion of two endogenous T2PKs gene clusters. | High-yield T2PKs producer; superior precursor supply; efficient for tri-, tetra-, and penta-ring T2PKs. | Overproduction of oxytetracycline; synthesis of actinorhodin and discovery of TLN-1 [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: BGC Deletion and Chassis Validation

This protocol outlines the creation of a cleaned-background Streptomyces chassis using homologous recombination, a widely applicable method for precise genetic manipulation.

Stage 1: Target Identification and Vector Construction

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify native BGCs for deletion using genome mining tools (e.g., antiSMASH [13] [12]). Prioritize clusters that produce known pigments, antibiotics, or those that compete for key precursors.

- Design Deletion Construct: Amplify approximately 1.5 - 2 kb DNA fragments corresponding to the upstream (UP) and downstream (DOWN) flanking regions of the target BGC from the host genome.

- Cloning: Assemble the UP and DOWN fragments into a suicide vector (e.g., pKC1139 [3]) that contains a temperature-sensitive origin of replication and an antibiotic resistance marker (e.g., apramycin) via restriction enzyme digestion and ligation or using advanced assembly techniques like Golden Gate Assembly [14].

Stage 2: Conjugation and Mutant Selection

- Conjugation: Introduce the constructed suicide vector into the target Streptomyces strain via intergeneric conjugation with E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) [13]. Plate the conjugation mixture on appropriate media and incubate at 30°C for 24-48 hours to allow for spore formation.

- Selection of Single-Crossover Integrants: Overlay the plates with apramycin and nalidixic acid (to counter-select against the E. coli donor). Incubate until exconjugants appear. These colonies represent strains where the plasmid has integrated into the chromosome via homologous recombination (single-crossover event).

- Selection of Double-Crossover Mutants: Streak single-crossover integrants onto fresh plates without antibiotics and incubate at a non-permissive temperature (e.g., 37-39°C) to force the loss of the temperature-sensitive plasmid. Screen resulting colonies for apramycin sensitivity, indicating a second crossover event and the excision of the plasmid.

- Genotype Verification: Confirm the intended deletion in apramycin-sensitive colonies using PCR with verification primers that bind outside the engineered homology arms. Sequence the PCR product to ensure precise deletion.

Stage 3: Phenotypic and Metabolomic Validation

- Metabolomic Profiling: Analyze the metabolome of the engineered chassis strain and the wild-type parent using LC-MS/MS. Compare the chromatograms to confirm the absence of metabolites previously associated with the deleted BGCs.

- Fermentation and Analysis: Ferment the validated chassis strain in a suitable production medium (e.g., GYM or M1 medium [13]). Extract the culture broth and mycelia with organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate). Analyze the extracts to establish a new, simplified metabolic baseline.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from chassis design to validation:

Diagram 1: Workflow for creating a clean metabolic background chassis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful chassis development relies on a suite of specialized genetic tools and reagents. The following table details essential components for these experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Chassis Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Principle | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Suicide Vectors | Plasmid that cannot replicate in the host; forces integration into chromosome for gene replacement. | pKC1139 (temperature-sensitive, apramycinᵁ) [3]. |

| Conjugative E. coli Strain | Donor strain capable of mobilizing plasmid DNA into actinomycetes via conjugation. | E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) [13]; improved strains in Micro-HEP platform [13]. |

| Recombineering Systems | Enables precise, PCR-based genetic modifications using short homology arms in E. coli. | Rhamnose-inducible Redα/Redβ/Redγ system [13]. |

| RMCE Systems | Allows precise, marker-less exchange of large DNA cassettes at specific chromosomal sites. | Cre-loxP, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, φBT1-attP [13]. |

| Assembly Techniques | High-efficiency, scarless assembly of multiple DNA fragments for vector or pathway construction. | Golden Gate Assembly (BsaI, PaqCI) [14]; ExoCET [3]. |

| Genome Mining Software | In silico identification of BGCs in microbial genomes to prioritize deletion targets. | antiSMASH [13] [12]. |

Concluding Remarks

The creation of microbial chassis with minimized metabolic backgrounds is a transformative strategy in metabolic engineering and natural product discovery. By systematically removing native BGCs, researchers can construct specialized cell factories that not only reduce analytical noise but also enhance the titers of valuable heterologous products. The protocols and tools outlined here provide a roadmap for developing such chassis, directly contributing to the acceleration of genome-driven drug discovery. As synthetic biology tools continue to advance, the precision and efficiency of chassis engineering will only increase, further solidifying its role as a foundational element of modern biotechnology.

The declining pace of novel natural product (NP) discovery, coupled with the rising crisis of antimicrobial resistance, has necessitated a paradigm shift in biodiscovery strategies. A vast majority of microbial biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) remain silent under standard laboratory conditions or are housed in uncultivable or genetically intractable organisms [15] [16] [17]. Heterologous expression—the process of transferring and expressing BGCs in a surrogate host—has emerged as a powerful solution to this impasse. This approach bypasses the need to cultivate the native producer and allows for the refactoring of BGCs for optimal expression [18] [17]. A critical and foundational decision in this process is the selection and engineering of an appropriate chassis strain. The core principle underpinning modern chassis development is genome reduction, wherein native BGCs are deleted to minimize metabolic competition, eliminate background interference, and channel precursors toward the heterologously expressed pathway of interest [3] [19] [20]. This application note details the construction and utilization of such engineered chassis for the efficient production of NPs from inaccessible species.

Chassis Development and Performance Metrics

The strategic deletion of native biosynthetic gene clusters is a cornerstone of chassis engineering. This process serves to streamline the host's metabolism, reduce the complexity of the metabolite background for easier detection of target compounds, and prevent the diversion of essential precursors like acyl-CoAs and amino acids. The following case studies exemplify the successful application of this strategy across different bacterial taxa.

Table 1: Engineered Chassis Strains for Heterologous Expression

| Chassis Strain | Parental Strain | Key Genetic Modifications | Primary Advantages | Validated Compounds Produced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureofaciens Chassis2.0 [3] | S. aureofaciens J1-022 | In-frame deletion of two endogenous type II PKS clusters | 370% increase in oxytetracycline yield; efficient production of tri-, tetra-, and penta-ring type II polyketides | Oxytetracycline, Actinorhodin, Flavokermesic acid, TLN-1 |

| Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH [20] | Streptomyces sp. A4420 | Deletion of 9 endogenous polyketide BGCs | Superior sporulation and growth; outperformed standard hosts in polyketide production | Glycosylated macrolide, Glycosylated polyene macrolactam, Heterodimeric aromatic polyketide |

| S. brevitalea DT/DC Series [19] | S. brevitalea DSM 7029 | Deletion of endogenous NRPS/PKS BGCs & nonessential regions (prophages, transposases) | Alleviated cell autolysis; improved growth; high-yield production of proteobacterial NPs | Epothilone, Vioprolide, Rhizomide, Chitinimides |

Workflow for Chassis Engineering and BGC Expression

The following diagram illustrates the generalized pipeline for developing an engineered chassis and using it for heterologous natural product discovery.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Construction of a Genome-Reduced Streptomyces Chassis

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a metabolically simplified Streptomyces chassis, based on methodologies successfully employed for Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH and S. aureofaciens Chassis2.0 [3] [20].

Genome Sequencing and In silico Analysis:

- Ispute high-quality genomic DNA from the selected parental strain.

- Perform whole-genome sequencing using a hybrid approach (e.g., Illumina for accuracy, Oxford Nanopore for scaffolding).

- Assemble the genome and annotate it using standard tools.

- Analyze the assembled genome using the antiSMASH software [20] [21] to identify all native biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Note: The antiSMASH web application is freely accessible.

Selection of BGCs for Deletion:

- Prioritize large BGCs, particularly those encoding polyketide synthases (PKS) and nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), which are major consumers of biosynthetic precursors.

- BGCs known to be expressed under laboratory conditions should be high-priority targets to clean the metabolic background.

Design of Deletion Constructs:

- For each target BGC, design a deletion construct that will remove the core biosynthetic genes (e.g., PKS/NRPS genes) while potentially leaving precursor biosynthesis genes intact.

- The construct should consist of an antibiotic resistance marker (e.g., apramycin) flanked by ~2 kb homology arms upstream and downstream of the target deletion region.

- Flank the resistance marker with

loxPorlox71/66sites to enable subsequent marker excision.

Genetic Transformation and Mutant Selection:

- Introduce the deletion construct into the parent strain via protoplast transformation or intergeneric conjugation from E. coli [16].

- Select for single-crossover integrants on apramycin-containing media.

- Under non-selective conditions, screen for double-crossover mutants that have lost the vector backbone, resulting in the replacement of the target BGC with the resistance marker.

Marker Excision and Iteration:

- Introduce a Cre recombinase plasmid into the mutant strain to catalyze recombination between the

loxPsites, excising the antibiotic marker. - The resulting strain is marker-free and ready for the next round of BGC deletion.

- Repeat steps 3-5 iteratively until all desired BGCs are removed.

- Introduce a Cre recombinase plasmid into the mutant strain to catalyze recombination between the

Validation of the Engineered Chassis:

- Verify all deletions by PCR amplification across the new genomic junctions.

- Optionally, use metabolomic analysis (e.g., LC-MS) to confirm the disappearance of native compounds and a cleaner metabolic profile.

- Assess growth characteristics to ensure the engineering process has not impaired fitness.

Protocol 2: Heterologous Expression of a BGC in an Engineered Chassis

This protocol describes the process of cloning and expressing a target BGC in the engineered chassis, leveraging modern assembly techniques [14] [17].

BGC Cloning:

- Isolation of Target BGC: Obtain the target BGC from the donor organism's genomic DNA. For large and complex BGCs, use direct cloning methods like Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) in yeast or Cas9-Assisted Targeting of CHromosome segments (CATCH) [19] [16].

- De novo Assembly: For refactoring or clusters from unculturable sources, use synthetic, bottom-up assembly. The Golden Gate Assembly (GGA) strategy is highly efficient [14].

- Domesticate the BGC sequence by removing internal restriction sites (e.g., for BsaI and PaqCI) via silent mutations.

- Assemble the cluster hierarchically from ~2 kb fragments into a shuttle vector (e.g., pPAP-series) in a two-step GGA process, achieving near 100% efficiency for complex assemblies [14].

BGC Refactoring (Optional but Recommended for Silent BGCs):

- Replace native promoters of the BGC operons with strong, constitutive synthetic promoters.

- Libraries of orthogonal promoters and ribosomal binding sites (RBS) can be used to tune the expression of individual genes for optimal flux [17].

Introduction into the Chassis:

- Transfer the assembled BGC construct into the engineered chassis strain via intergeneric conjugation from an E. coli donor strain (e.g., ET12567/pUZ8002) [16] [20].

- Select for exconjugants on agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., apramycin) and antibiotics to counter-select against the E. coli donor.

Fermentation and Metabolite Analysis:

- Inoculate the positive exconjugants into liquid media suitable for secondary metabolite production.

- Ferment at the optimal temperature and duration for the chassis strain (e.g., 2-7 days for most Streptomyces).

- Extract the culture broth and mycelia with a suitable organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate, butanol).

- Analyze the extracts using LC-HRMS and compare the chromatograms to those of the empty chassis control to identify new peaks corresponding to the heterologously produced compound(s).

- Use analytical techniques like NMR for structural elucidation of the novel compound.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Chassis Development and BGC Expression

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [21] | In silico identification and analysis of BGCs in a genome sequence. | First-step analysis to select native BGCs for deletion in a potential chassis strain. |

| Golden Gate Assembly (GGA) [14] | A modular, one-pot DNA assembly method using Type IIS restriction enzymes. | High-efficiency, hierarchical assembly of large, refactored BGCs with 100% success rate reported for a 23 kb cluster. |

| pCAP03 Vector [15] | Capture vector for cloning large DNA fragments from genomic DNA. | Capturing and integrating putative BGCs (e.g., the siderochelin cluster) into a model host like S. coelicolor. |

| Cre-loxP System [19] | Site-specific recombination system for marker excision. | Recycling antibiotic resistance markers after each round of BGC deletion in chassis construction. |

| Redαβ Recombineering [19] | A system for efficient markerless genetic engineering in proteobacteria. | Construction of genome-reduced mutants of S. brevitalea by deleting large genomic regions. |

| S. coelicolor M1152/M1154 [14] [15] | Model engineered Streptomyces hosts with four native BGCs deleted and ribosomal mutations. | Benchmark strains for testing heterologous BGC expression and activity. |

| Orthogonal Promoter Libraries [17] | Synthetic promoter sets with randomized sequences for minimized cross-talk. | Refactoring silent BGCs by replacing native promoters to ensure strong, coordinated expression in the heterologous host. |

Concluding Remarks

The strategic engineering of specialized chassis strains through targeted genome reduction represents a transformative approach for unlocking the vast chemical potential encoded in unculturable and challenging microbes. The case studies of S. aureofaciens Chassis2.0, Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH, and the S. brevitalea DT/DC series demonstrate that deleting native BGCs is a highly effective method to create streamlined hosts with enhanced capabilities for heterologous production [3] [19] [20]. As cloning and DNA synthesis technologies continue to advance, the development of a diverse and well-characterized panel of chassis strains will be crucial for accelerating the discovery of the next generation of medically relevant natural products.

The 'How': A Step-by-Step Guide to Constructing Your Genome-Reduced Chassis

The heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) has become a cornerstone strategy for discovering new natural products (NPs) and elucidating their biosynthetic pathways. This approach is particularly valuable for accessing the metabolic potential of unculturable organisms, poorly expressed silent clusters, or genetically intractable strains. A critical determinant of success in these endeavors is the selection of an appropriate heterologous host. The ideal host provides a compatible physiological and genetic background that supports the expression, folding, and post-translational modification of heterologous enzymes, as well as the metabolic precursors required for biosynthesis. This application note details the criteria for selecting heterologous hosts, ranging from the well-established Streptomyces models to specialized Gram-negative systems, providing a structured framework for researchers to engineer optimal production chassis. The content is framed within the context of a broader thesis on creating specialized heterologous production chassis, often involving the deletion of native BGCs to minimize background interference and redirect metabolic flux.

Quantitative Comparison of Heterologous Host Systems

The selection of a heterologous host is often a balance between phylogenetic proximity to the native producer and the practical tools available for genetic manipulation. The table below summarizes key hosts, their optimal BGC sources, and quantitative performance metrics based on recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics and Characteristics of Common Heterologous Hosts

| Host Organism | Optimal BGC Source | Reported Cloning Success Rate | Reported Expression Success Rate | Key Advantages | Notable Production Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces albus J1074 | Actinobacteria [22] | 68% (17/25 BGCs cloned) [22] | 11% (4/36 clones expressed) [22] | Strong genetic toolbox, minimized secondary metabolism [23] | Discovery of 63 new NP families (across multiple hosts) [22] |

| Streptomyces coelicolor M1152/M1146 | Actinobacteria [24] | Information Missing | Information Missing | Deleted endogenous BGCs, well-characterized physiology [24] [10] | Oviedomycin at 670 mg/L (after engineering) [24] |

| Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) | RiPPs from multiple phyla [22] | 86% (83/96 BGCs cloned) [22] | 32% (27/83 BGCs expressed) [22] | Rapid growth, extensive molecular tools, simple metabolism | High success rate for small (<18 kb) RiPP BGCs [22] |

| Bacillus subtilis | Firmicutes [22] [25] | 100% (43/43 BGCs cloned in one study) [22] | 16% (7/43 BGCs expressed in one study) [22] | Efficient protein secretion, genetic tractability | Compatible with TAR cloning system (pCAPB02 vector) [25] |

| Streptococcus mutans UA159 | Anaerobic Firmicutes (Oral microbiome) [26] | Successful cloning of 73.7-kb BGC via NabLC [26] | Functional expression of pyrazinone and tetramic acid BGCs [26] | Facultative anaerobe, natural competence, mimics anaerobic environment | Discovery of mutanocyclin [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Host Engineering and BGC Expression

Protocol 1: Construction of a Deletion-MinimizedStreptomyces coelicolorChassis

This protocol outlines the creation of a specialized S. coelicolor chassis, strain A3(2)-2023, engineered for high-yield heterologous expression [23].

Materials:

- S. coelicolor A3(2) wild-type strain

- pCRISPomyces-2BD plasmid (or similar CRISPR-Cas9 system for Streptomyces) [10]

- Donor E. coli strain (e.g., ET12567/pUZ8002 or GB2005 for Micro-HEP) [23]

- Appropriate antibiotics for selection

Method:

- Bioinformatic Identification: Use antiSMASH to identify all native BGCs in the S. coelicolor A3(2) genome.

- sgRNA Design: Design multiple sgRNAs targeting conserved regions of the four largest endogenous BGCs (actinorhodin, prodiginine, CPK, and CDA) for simultaneous deletion.

- CRISPR Plasmid Construction: Clone the sgRNA cassettes into the pCRISPomyces-2BD plasmid. The Cas9-BD variant is recommended for reduced off-target cleavage in high-GC content genomes [10].

- Conjugative Transfer: Introduce the constructed plasmid from the donor E. coli strain into S. coelicolor via biparental conjugation.

- Screening and Validation: Screen for exconjugants and verify the deletion of target BGCs via PCR and loss of characteristic pigment production.

- Introduction of RMCE Sites: Integrate multiple orthogonal recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites (e.g., loxP, vox, rox, attP) into the genome of the deletion strain to create S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023. This enables stable, multi-copy integration of heterologous BGCs [23].

Protocol 2: Heterologous Expression of a BGC in an Optimized Host

This protocol describes the capture, refactoring, and expression of a target BGC in the engineered S. coelicolor M1152 chassis, based on the overproduction of oviedomycin [24].

Materials:

- pCBA (pCAP-BAC-Apr) or similar low-copy BGC capture vector [24]

- Gibson assembly reagents

- E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) for conjugation

- S. coelicolor M1152 heterologous host

Method:

- BGC Capture: Isolate the target BGC (e.g., ovm cluster) from genomic DNA via PCR or direct cloning. Ligate the fragment into the linearized pCBA vector using Gibson assembly to create pCBAO [24].

- Promoter Refactoring (Optional): To enhance expression, refactor native promoters in the BGC. Using an in vitro CRISPR/Cas9 system, replace weak native promoters (e.g., the promoter for the least-transcribed gene, identified by RT-qPCR) with strong, constitutive promoters like ermE* or kasO*p. This generates a refactored plasmid (e.g., pCBAO1) [24].

- Conjugative Transfer: Transform the final plasmid (pCBAO or pCBAO1) into E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) and conjugate into S. coelicolor M1152 to generate the final production strain (e.g., SCMO or SCMO1).

- Fermentation and Metabolite Analysis: Cultivate the exconjugant in a suitable production medium (e.g., R5 or SFM). After 5-7 days, extract the culture and analyze metabolites using HPLC and LC-MS/MS to detect the target compound [24].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process and technical workflow for selecting and utilizing a heterologous host, from initial bioinformatic analysis to final compound isolation.

Diagram 1: Host Selection and Heterologous Expression Workflow. This chart outlines the decision pathway for selecting an appropriate heterologous host based on the origin and characteristics of the target BGC, leading to the steps for chassis engineering and compound production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key reagents and tools that form the foundation of heterologous expression studies, as featured in the protocols and literature.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Heterologous Expression Workflows

| Reagent / Tool Name | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| pCAP Series Vectors (e.g., pCAP01, pCAPB02) | TAR cloning and shuttle vectors for BGC capture in yeast and expression in various bacterial hosts. [25] | Direct cloning of large BGCs (>80 kb) from genomic DNA for integration into Streptomyces or B. subtilis. [25] |

| CRISPR-Cas9-BD System | Genome editing tool with reduced off-target cleavage for high-GC content organisms like Streptomyces. [10] | Simultaneous deletion of multiple native BGCs or refactoring promoters within a heterologous BGC. [24] [10] |

| E. coli ET12567 (pUZ8002) | Donor strain for conjugative transfer of DNA from E. coli to actinomycetes and other bacteria. [24] | Mobilizing BGC-containing plasmids from the cloning host (E. coli) into the final Streptomyces expression host. |

| S. coelicolor M1152 | Model Streptomyces chassis with four deleted endogenous BGCs (act, red, cpk, cda) and a relaxed restriction system. [24] | A clean background host for heterologous expression of actinobacterial BGCs to minimize native interference. |

| Micro-HEP Platform | A comprehensive system using engineered E. coli and S. coelicolor strains for BGC modification, transfer, and multi-copy integration via RMCE. [23] | High-throughput engineering and expression of BGCs to boost production yields, as demonstrated for xiamenmycin. [23] |

Within synthetic biology, the construction of specialized microbial chassis for heterologous natural product (NP) production is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery pipelines [17]. These chassis are engineered to optimally express biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) sourced from diverse organisms, thereby facilitating the discovery and yield optimization of valuable compounds [18]. A critical step in chassis development is the elimination of native BGCs to minimize metabolic burden, avoid background interference, and redirect cellular resources toward the target pathway [23]. This application note provides a detailed protocol for systematically identifying native BGCs suitable for deletion, while ensuring host viability through the integration of essential gene data. We outline a synergistic methodology leveraging the genome mining tool antiSMASH and the Database of Essential Genes (DEG) to inform strategic, non-detrimental genetic refactoring.

The Scientific and Methodological Foundation

The rationale for this protocol is rooted in two key principles: the dispensability of most secondary metabolite pathways under standard laboratory conditions, and the indispensable nature of essential genes for core cellular function.

- BGC Dispensability: Secondary metabolites are not required for organism survival in axenic culture. Consequently, the BGCs encoding them are prime targets for deletion to create a clean genetic background [23]. This simplifies the metabolic landscape of the chassis and prevents the production of competing or interfering compounds.

- Gene Essentiality: Essential genes are those indispensable for organism survival under specific environmental conditions [27]. Their products are often involved in fundamental processes like DNA replication, transcription, translation, and core metabolism. DEG serves as a curated repository of genes experimentally determined to be essential across a wide range of organisms, providing a critical reference to avoid disrupting vital functions during chassis engineering [27].

The integration of BGC mapping with essential gene data allows researchers to distinguish between dispensable genomic regions (BGCs) and non-targetable regions (essential genes), thereby de-risking the deletion strategy.

Computational Identification of Native BGCs Using antiSMASH

antiSMASH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis SHell) is the leading tool for the automated detection and annotation of BGCs in microbial genomes [28] [29]. The following protocol describes its use for identifying deletion targets.

Experimental Protocol: antiSMASH Analysis

- Input Preparation: Obtain the genome sequence of the potential chassis organism in FASTA format (either nucleotide or protein sequence). Ensure the annotation is of high quality, as this improves gene prediction and, consequently, BGC detection accuracy.

- Job Submission and Execution:

- Access the public antiSMASH web server (https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/) or install a local copy for large-scale analyses [29].

- Upload your genome FASTA file.

- Select the appropriate organism type (e.g., "bacteria" or "fungi") and, if known, the specific genus (e.g., Streptomyces) to enable lineage-specific analysis refinements.

- Initiate the analysis. For large genomes, processing may take several hours.

- Output Interpretation and Data Extraction:

- The primary output is an interactive HTML page detailing the location and type of each detected BGC [28].

- Identify all genomic regions flagged as BGCs. antiSMASH version 8.0 can detect over 100 different cluster types, including nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), polyketide synthase (PKS), ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide (RiPP), and terpenoid clusters [28].

- For each BGC, record the genomic coordinates (start and end positions), the predicted BGC type, and the core biosynthetic genes.

- Optional: Use the integrated "KnownClusterBlast" or "ClusterCompare" features to assess similarity to BGCs with characterized metabolites in the MIBiG (Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster) repository, which can help prioritize deletions of clusters producing known, unwanted metabolites [28].

Table 1: Key BGC Detection Tools and Databases

| Tool/Database Name | Primary Function | Relevance to Deletion Target Identification |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH [28] [29] | Detects & annotates BGCs in genomic data | Core tool for mapping all native biosynthetic pathways in a chassis genome. |

| MIBiG [17] [28] | Repository of experimentally characterized BGCs | Provides context on the known products of BGCs homologous to those in your chassis. |

| BAGEL [30] | Dedicated mining tool for RiPPs (e.g., bacteriocins) | Complementary tool for identifying a specific class of BGCs. |

| ARTS [30] [28] | Detects BGCs and identifies unique, essential resistance genes | Helps identify essential genes within BGCs that should not be deleted. |

Mapping Essential Genes Using the Database of Essential Genes (DEG)

Concurrently with BGC identification, it is crucial to map the essential genes within the chassis genome to prevent their accidental deletion.

Experimental Protocol: Interrogating Essential Gene Data

- Data Source Access: Navigate to the Database of Essential Genes (DEG), which compiles essential genes identified through large-scale experimental studies [27].

- Cross-Referencing and Analysis:

- Query the DEG using the name or identifier of your chassis organism to retrieve a list of its experimentally determined essential genes.

- If a dedicated entry for your specific chassis strain is unavailable, use data from the most closely related species or strain.

- Map the genomic coordinates of the essential genes onto the chassis genome. This can be done by using the essential gene identifiers to extract location data from a matching genome annotation file.

- Create a consolidated list or a visual genomic map that clearly displays the locations of both BGCs (from antiSMASH) and essential genes (from DEG).

An Integrated Workflow for Prioritizing Deletion Targets

The core of this application note is the integration of the two data streams generated above. The following workflow and decision logic ensure a systematic and safe approach to target selection.

Workflow Decision Logic:

- Data Integration: Superimpose the mapped BGCs and essential genes onto a single genomic view.

- Target Filtering: Immediately exclude any BGC from the deletion candidate list if its genomic locus shows any overlap with a known essential gene. The essential function takes precedence.

- Target Prioritization: For the remaining, non-overlapping BGCs, establish a prioritization for deletion. Considerations include:

- Cluster Similarity: Use antiSMASH's ClusterCompare results to prioritize BGCs that are identical or highly similar to known clusters producing interfering compounds [28].

- Metabolic Burden: Larger BGCs may impose a greater metabolic load, making their deletion beneficial for host fitness [23].

- Genetic Stability: BGCs with repetitive sequences (common in PKS/NRPS clusters) can be prone to recombination and may be prioritized for deletion to enhance genomic stability [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Resources for Chassis Engineering

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Application in This Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH Software [28] [29] | Rule-based and machine-learning-powered BGC detection platform. | Identifying and annotating native BGCs in the chassis genome. |

| Database of Essential Genes (DEG) [27] | Curated database of genes essential for survival under specific conditions. | Defining genomic regions that must be preserved during deletion efforts. |

| MIBiG Database [17] [28] | Reference repository of experimentally characterized BGCs. | Inferring the potential chemical output of homologous native BGCs. |

| Red/ET Recombineering [17] [23] | High-efficiency genetic engineering system using phage-derived recombinases (Redα/Redβ). | Performing precise, markerless deletions of targeted BGCs in the chassis. |

| Conditional Promoters (e.g., pNiiA) [31] | Regulatable promoters used to control gene expression (e.g., nitrogen-regulated). | Validating essential gene function by creating conditional mutants, if needed. |

| RMCE Systems (Cre-lox, Vika-vox) [23] | Recombinase-Mediated Cassette Exchange systems for precise genomic integration. | Useful for advanced chassis engineering, such as inserting heterologous BGCs after clearing native ones. |

Visualization and Experimental Validation of Targets

Before committing to lengthy deletion campaigns, it is prudent to conduct preliminary checks on the expression of targeted BGCs.

Experimental Protocol: Transcriptomic Validation

- Objective: To confirm that a BGC targeted for deletion is transcriptionally active under your laboratory fermentation conditions, thereby justifying the engineering effort.

- Methodology:

- Culture the wild-type chassis strain under standard production conditions.

- Harvest cells at appropriate time points and extract total RNA.

- Perform reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) targeting the core biosynthetic genes (e.g., PKS KS or NRPS A domains) of the BGCs identified for deletion.

- Use primers for a constitutively expressed essential gene (e.g., a ribosomal protein gene) as an internal control.

- Data Analysis: Significant expression of the BGC core genes confirms the cluster is not silent and that its deletion may beneficially reduce metabolic competition.

The strategic development of a heterologous production chassis requires careful genomic planning. The integrated use of antiSMASH for BGC discovery and the Database of Essential Genes for conservation mapping provides a robust, data-driven framework for identifying safe and effective deletion targets. This protocol minimizes the risk of impairing host viability while guiding the engineering of a clean, high-yielding microbial factory for natural product discovery and production.

The discovery and production of microbial natural products (NPs), indispensable resources in medicine and agriculture, are often hindered because the native biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in original hosts are silent, poorly expressed, or difficult to manipulate genetically [13] [32]. A pivotal strategy to overcome these challenges is the development of optimized heterologous production chassis—engineered host organisms that provide a defined metabolic background for the expression of foreign BGCs [13] [17]. A core step in creating these chassis is the deletion of native, competing BGCs to redirect cellular resources toward the production of the target heterologous compound [13] [10].

This application note details three foundational genetic technologies—Red recombineering, CRE-loxP, and CRISPR-Cas systems—that enable the precise deletion of native BGCs and the refinement of heterologous hosts. We provide structured comparisons, detailed protocols, and visual workflows to facilitate their application in strain engineering for NP discovery and yield optimization.

The table below summarizes the core functions, primary applications, and key characteristics of the three genetic toolkits discussed in this note.

Table 1: Key Genetic Toolkits for Heterologous Chassis Development

| Technology | Core Function | Primary Application in Chassis Development | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red Recombineering | Homologous recombination using short (∼50 bp) homology arms, mediated by λ phage Redα/Redβ/Redγ proteins in E. coli [13]. | High-efficiency modification and engineering of BGCs cloned into E. coli vectors prior to transfer to the final heterologous host [13]. | - Efficiency: High in E. coli with short homology arms [13].- Throughput: Ideal for sequential or iterative modifications [13].- Key Feature: Enables markerless manipulation via counterselectable cassettes (e.g., rpsL) [13]. |

| CRE-loxP | Site-specific recombination catalyzed by Cre recombinase between 34 bp loxP sites [33]. | - Excision: Deletion of large genomic regions, including multiple native BGCs [34].- Integration: Precise, marker-less integration of DNA cassettes [13]. | - Versatility: Can be used for deletion, inversion, or integration [33].- Precision: Allows recycling of selection markers [13].- Application: Used in recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) with other systems (Vika/vox, Dre/rox) [13]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | RNA-programmed nucleases (e.g., Cas9) creating double-strand breaks at specific genomic loci [10]. | - Targeted Deletion: Knockout of single or multiple native BGCs in the host genome [10].- Gene Activation/Repression: Using catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) for multiplexed gene expression modulation [10]. | - Multiplexing: Enables simultaneous targeting of multiple loci [10].- Efficiency: Can induce high cytotoxicity if off-target cleavage is not controlled [10].- Innovation: Engineered Cas9-BD variant reduces off-target effects in high GC-content Streptomyces [10]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table presents key performance metrics for these technologies, particularly in the context of engineering actinomycetes like Streptomyces, which are common heterologous hosts.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Genetic Toolkits

| Technology / Specifics | Reported Efficiency / Outcome | Experimental Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9-BD (This refers to a modified Cas9 with polyaspartate tags at both N- and C-termini to reduce off-target binding [10] [35]) | ||

| Editing Efficiency | 98.1% ± 1.40% [10] | Deletion of matAB genes in S. coelicolor M1146 [10]. |

| Exconjugant Yield | 77-fold increase vs. wild-type Cas9 [10] | Same experiment as above; indicates significantly reduced cytotoxicity [10]. |

| Off-Target Cleavage | Dramatically decreased [10] [35] | In vitro assays with non-PAM sequences (e.g., -NGA, -NGT) [10]. |

| Micro-HEP Platform (Utilizes RMCE with orthogonal recombinase systems like Cre-loxP, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, and phiBT1-attP [13]) | ||

| BGC Copy Number & Yield | Increasing xiamenmycin yield with 2 to 4 copies of the xim BGC [13] | Demonstrates the utility of RMCE for gene dosage studies and yield optimization [13]. |

Application Notes & Detailed Protocols

Protocol 1: Two-Step Red Recombineering for Markerless DNA Manipulation inE. coli

This protocol is used for the initial cloning and modification of BGCs in E. coli before their conjugation into a Streptomyces chassis [13].

1. Principle: A rhamnose-inducible Redα/Redβ/Redγ system and an arabinose-inducible CcdA protein are used for a two-step, markerless modification. The Red system facilitates homologous recombination with short homology arms, while CcdA counter-selection allows for the removal of selection markers [13].

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Key Reagents for Red Recombineering

| Reagent | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered E. coli Strain | Host for recombineering. | Contains the temperature-sensitive plasmid pSC101-PRha-αβγA-PBAD-ccdA [13]. |

| pSC101-PRha-αβγA-PBAD-ccdA Plasmid | Expresses λ phage Redα/Redβ/Redγ recombinases and the CcdA counter-selection protein [13]. | - Recombinase Induction: 10% L-rhamnose [13].- CcdA Induction: 10% L-arabinose [13]. |

| Selection Cassette | Selects for successful recombination events. | amp-ccdB or kan-rpsL cassette [13]. The rpsL gene can be used for streptomycin-based counter-selection [13]. |

| Homology Arms | Guides the precise integration of the cassette and the subsequent insertion of the desired sequence. | 50 bp arms flanking the target site are sufficient [13]. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Electroporation: Introduce the recombinase expression plasmid pSC101-PRha-αβγA-PBAD-ccdA into the recipient E. coli strain [13].

- First Recombination (Cassette Integration):

- Design a linear DNA cassette containing a selectable marker (e.g., kan-rpsL) flanked by 50 bp homology arms matching the target region [13].

- Induce the expression of both the recombinase and CcdA with 10% L-rhamnose and 10% L-arabinose [13].

- Electroporate the linear cassette into the induced cells. CcdA expression promotes the survival of cells that have successfully integrated the cassette by neutralizing the toxic CcdB protein that would otherwise be expressed from the plasmid in the absence of a successful recombination event [13].

- Select for clones with the correctly integrated cassette on appropriate antibiotic plates [13].

- Second Recombination (Marker Removal & Final Modification):

- Design a single-stranded oligonucleotide or a double-stranded DNA fragment containing the desired final modification (e.g., a promoter swap, point mutation, or simply the removal of the marker) flanked by the appropriate homology [13].

- Induce recombinase expression with L-rhamnose and electroporate the DNA fragment [13].

- In this step, CcdA is not induced. Cells that have excised the kan-rpsL cassette (and thus lost the CcdA-expressing part of the plasmid) will be susceptible to counter-selection (e.g., on streptomycin plates if the rpsL cassette was used) or simply screened for antibiotic sensitivity [13].

- Screen for colonies that have lost the marker and verify the final, markerless modification by PCR and sequencing [13].

Protocol 2: CRE-loxP for Deletion of Native BGCs in a Chassis Strain

This protocol describes the use of CRE-loxP recombination to remove native biosynthetic gene clusters from a potential heterologous host genome, streamlining its metabolic background [13] [34].

1. Principle: Cre recombinase recognizes specific 34 bp loxP sites. When two loxP sites are placed in the same orientation on a chromosome, the DNA segment between them ("floxed") is excised and degraded upon Cre expression, leaving a single loxP site behind [33].

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 4: Key Reagents for CRE-loxP-Mediated Deletion

| Reagent | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Vector | A plasmid containing a selection marker (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene) itself flanked by loxP sites, and homology arms for the target genomic locus. | Used to introduce the first loxP site and marker [34]. |

| Cre Recombinase | The enzyme that catalyzes the site-specific recombination between loxP sites. | Can be delivered on a transient plasmid, via conjugation, or expressed from a chromosomally integrated gene [13] [33]. |

| "Floxed" Selection Marker | A selectable marker placed between two loxP sites. | Allows for selection of integration events and is later removed by Cre, enabling marker recycling [13]. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Vector Construction & Integration:

- Clone homology arms (∼1-2 kb) corresponding to the regions flanking the BGC to be deleted into a vector containing a "floxed" selection marker (e.g., aac(3)IV-loxP) [13] [34].

- Introduce this targeting vector into the chassis strain (e.g., Streptomyces coelicolor) via conjugation or protoplast transformation [13].

- Select for single-crossover integrants on antibiotic plates. These strains now have the entire vector, including the loxP-flanked marker, integrated into the genome [13].

- Second Crossover & Marker Excision:

- Propagate the integrants without selection to allow for a second homologous recombination event. This can excise the vector backbone and leave behind the "floxed" marker cassette in the genome, replacing the native BGC [13] [34].

- Screen for colonies that are sensitive to the antibiotic used for the marker, indicating the second crossover has occurred.

- Verify the correct genotype by PCR.

- Cre-Mediated Marker Recycling:

- Introduce a plasmid expressing Cre recombinase into the strain containing the "floxed" marker [13].

- Cre will excise the marker, leaving a single loxP "scar" sequence in the place of the deleted BGC [13] [33].

- The Cre-expression plasmid can often be lost from the strain by cultivating it at a higher temperature (if the plasmid is temperature-sensitive) [13].

- The resulting strain has a clean deletion of the native BGC and can be used for another round of deletion or for BGC integration.

Protocol 3: CRISPR-Cas9-BD for Multiplexed BGC Deletion inStreptomyces

This protocol uses a modified Cas9 protein (Cas9-BD) to simultaneously delete multiple native BGCs in Streptomyces, which have high GC-content genomes where traditional Cas9 shows high cytotoxicity [10].

1. Principle: The Cas9-BD protein, engineered with polyaspartate tags at its N- and C-termini, retains high on-target cleavage efficiency while dramatically reducing off-target binding and cleavage in high GC-content genomes [10]. When co-expressed with guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting regions flanking a BGC, it creates double-strand breaks that can be repaired by the cell's endogenous machinery, leading to the deletion of the intervening DNA [10].

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 5: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9-BD Editing in Streptomyces

| Reagent | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| pCRISPomyces-2BD Plasmid | Expression vector for the modified Cas9-BD protein and sgRNA[s] [10]. | A derivative of pCRISPomyces-2 where the wild-type cas9 is replaced with cas9-BD [10]. |

| Repair Template (Optional) | A DNA template for homology-directed repair (HDR) to introduce specific sequences or to enhance deletion efficiency. | For large deletions, a double-stranded DNA fragment with long homology arms can be used [10]. |

| sgRNA Expression Cassette | Encodes the RNA that guides Cas9-BD to the specific target genomic loci. | Targets are designed for the 5' and 3' ends of the BGC to be deleted [10]. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Design and Construction:

- Design two sgRNAs that bind to genomic sites immediately upstream and downstream of the BGC targeted for deletion.

- Clone the expression cassettes for these sgRNAs into the pCRISPomyces-2BD plasmid [10].

- If using a repair template, synthesize a linear DNA fragment containing the desired sequence (which could simply be a direct junction of the flanking regions to facilitate deletion) with homology arms (≥500 bp) [10].

- Delivery and Conjugation:

- Introduce the assembled pCRISPomyces-2BD plasmid (with or without the repair template) into the Streptomyces chassis strain via intergeneric conjugation from an E. coli donor strain [10].

- Selection and Screening:

- Select for exconjugants on apramycin plates (or the appropriate antibiotic for the plasmid).

- Due to the reduced cytotoxicity of Cas9-BD, a significantly higher number of exconjugants (e.g., 77-fold more) is expected compared to using wild-type Cas9 [10].

- Screen the resulting colonies by PCR to identify those with the successful BGC deletion.

- Plasmid Curing:

- Propagate the positive mutants without antibiotic selection to allow for the loss of the pCRISPomyces-2BD plasmid.

- Verify plasmid loss by patching colonies onto plates with and without apramycin. The final engineered chassis strain is antibiotic-sensitive and free of the native BGC.

The heterologous production of specialized microbial natural products is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and development. A critical strategy in this field involves the engineering of microbial "chassis" strains by deleting native biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). This process serves to minimize metabolic competition, eliminate background interference, and redirect cellular resources toward the production of target compounds. This Application Note details the construction, validation, and implementation of three distinct bacterial chassis engineered through this paradigm: the Gram-positive Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain, the Gram-negative Schlegelella brevitalea DT mutants, and the versatile S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 platform. The protocols and data presented herein provide a framework for researchers to select and apply these chassis systems for the efficient production of diverse natural products.

Application Notes: Engineered Chassis Strains and Their Performance

1Streptomycessp. A4420: A Polyketide-Focused Chassis

Background and Rationale: Streptomyces sp. A4420 was identified from a natural organism library due to its rapid growth and high inherent metabolic capacity, particularly for producing the alkaloid streptazolin [36]. To repurpose it as a general heterologous host, a chassis (CH) strain was developed with a specific focus on expressing polyketide-derived natural products.

Engineering Strategy: The engineering involved the deletion of nine native polyketide BGCs from the wild-type genome. This created a metabolically simplified host with consistent sporulation and growth patterns [36].

Performance Validation: The chassis was tested by expressing four distinct polyketide BGCs and comparing production against common heterologous hosts like S. coelicolor M1152 and S. lividans TK24. The Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain was the only host capable of producing all four target metabolites under every tested condition, demonstrating its superior versatility and efficiency [36].

Table 1: Engineering and Performance Summary of Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH Strain

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Parental Strain | Streptomyces sp. A4420 |

| Engineering Goal | Polyketide-specialized heterologous expression |

| Key Genetic Modification | Deletion of 9 native polyketide BGCs |

| Growth Characteristics | Rapid initial growth, consistent sporulation |

| Validation Metabolites | Four distinct polyketides (Type I and II) |

| Comparative Performance | Outperformed parental strain and conventional hosts (S. coelicolor M1152, S. lividans TK24) |

2Schlegelella brevitaleaDT Mutants: Genome-Reduced Gram-Negative Chassis

Background and Rationale: Schlegelella brevitalea DSM 7029 is a Gram-negative β-proteobacterium with potential for heterologously expressing proteobacterial natural products. However, its utility was limited by early autolysis, which severely restricted fermentation biomass [37].

Engineering Strategy: A rational genome reduction approach was pursued via two parallel routes: 1) Deletion of large, endogenous nonribosomal peptide synthetase/polyketide synthase (NRPS/PKS) BGCs (DC series mutants); and 2) Deletion of nonessential genomic regions, including prophages, transposases, and genomic islands (DT series mutants). The DT series mutants were designed to alleviate autolysis and improve robustness [37].

Performance Validation: The DT mutants showed improved growth characteristics with alleviated cell autolysis. When tested for the production of six different proteobacterial natural products, the DT chassis achieved higher yields than the wild-type DSM 7029 strain and other common Gram-negative hosts like Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas putida [37]. Furthermore, these chassis enabled the identification of "chitinimides," new detoxin-like compounds, by expressing a cryptic BGC from Chitinimonas koreensis [37].

Table 2: Engineering and Performance Summary of Schlegelella brevitalea DT Chassis

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Parental Strain | Schlegelella brevitalea DSM 7029 |

| Engineering Goal | Robust host for Gram-negative bacterial BGCs |

| Key Genetic Modification | Deletion of nonessential regions (prophages, transposons, islands) |

| Growth Characteristics | Improved growth, alleviated early autolysis |

| Key Advantage | Native production of methylmalonyl-CoA (key PK extender unit) |

| Application Proof | High-yield production of 6 tested natural products; discovery of chitinimides |

3S. coelicolorA3(2)-2023: A High-Efficiency Expression Platform

Background and Rationale: S. coelicolor is a genetically well-characterized model organism frequently used as a heterologous host. The A3(2)-2023 strain was developed as part of the Micro-HEP (microbial heterologous expression platform) to streamline the entire process from BGC modification to expression [23].

Engineering Strategy: The chassis was engineered by deleting four endogenous BGCs to create a cleaner metabolic background. Furthermore, multiple orthogonal recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) sites (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox, and phiBT1-attP) were introduced into the chromosome to facilitate stable, multi-copy integration of heterologous BGCs without plasmid backbone incorporation [23].

Performance Validation: The platform's efficiency was demonstrated using the xiamenmycin (anti-fibrotic) and griseorhodin BGCs. A direct correlation between BGC copy number and product yield was observed for xiamenmycin. The system also successfully enabled the production of a new compound, griseorhodin H, showcasing its power in natural product discovery [23].

Protocols: Key Methodologies for Chassis Utilization

Protocol: Heterologous Expression inStreptomycessp. A4420 CH

Principle: This protocol describes the process of introducing and expressing a heterologous BGC in the Streptomyces sp. A4420 CH strain, from vector construction to fermentation and metabolite analysis [36].

Procedure: