Comparative Analysis of Objective Functions for Flux Prediction: From FBA to Machine Learning

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of objective functions used in metabolic flux prediction, a critical task for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Objective Functions for Flux Prediction: From FBA to Machine Learning

Abstract

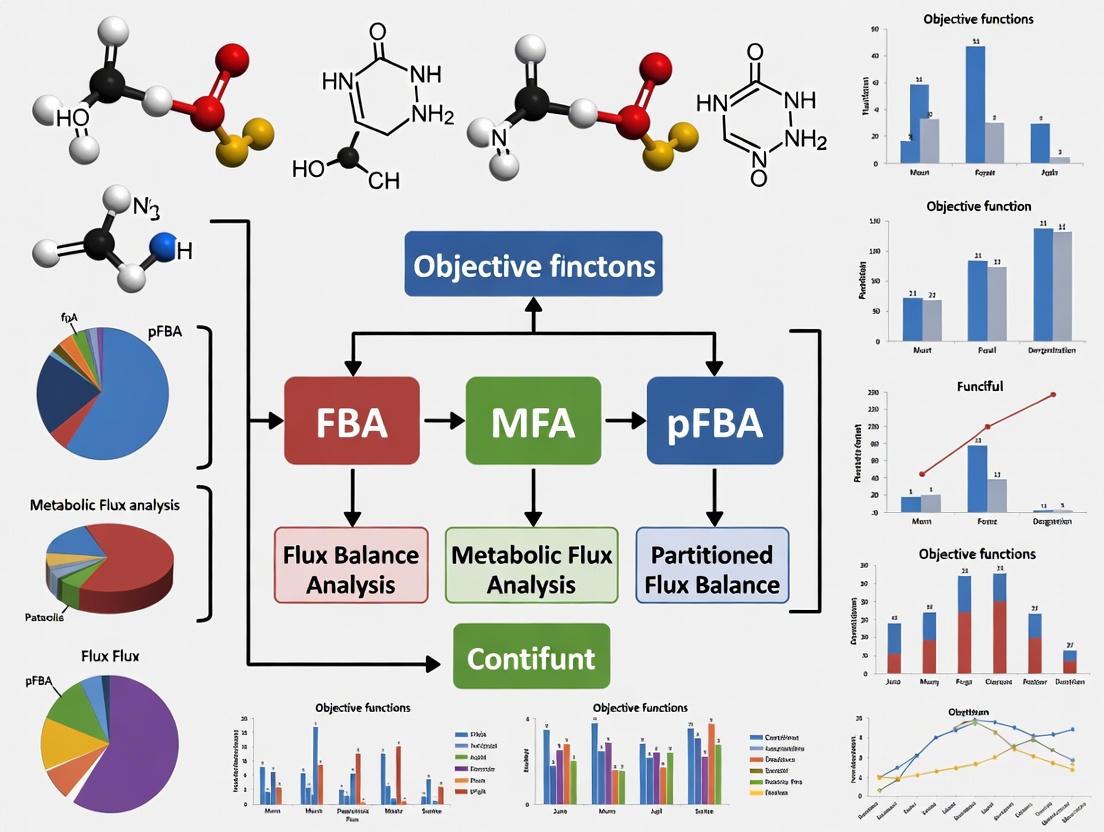

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of objective functions used in metabolic flux prediction, a critical task for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles of constraint-based modeling, including Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), and the pivotal role that the choice of objective function plays in determining accurate flux distributions. The scope extends to traditional methods like parsimonious FBA and the emerging paradigm of machine learning-based approaches, such as artificial neural networks, which offer rapid and accurate flux computations. We systematically address troubleshooting and optimization strategies for selecting and refining objective functions and conclude with robust validation and model selection frameworks to guide reliable flux analysis in biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Role of Objective Functions in Constraint-Based Metabolic Modeling

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a powerful mathematical approach for analyzing the flow of metabolites through metabolic networks. This method uses optimization to predict how a biological system, from single cells to complex communities, distributes metabolic fluxes to achieve a specific biological objective, such as maximizing growth or the production of a target metabolite [1] [2]. By relying on the stoichiometry of the network and constraints, FBA can make quantitative predictions without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, making it particularly valuable for studying genome-scale models [2].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core principles of FBA, with a special focus on the critical role and selection of the objective function.

Core Mathematical Principles of FBA

FBA is built upon a constraint-based modeling framework. The core idea is that an organism's metabolism must operate within physical and chemical constraints, which define a set of possible metabolic behaviors.

The Stoichiometric Matrix and Mass Balance

The metabolic network is mathematically represented by the stoichiometric matrix (S). In this matrix, each row represents a unique metabolite and each column represents a biochemical reaction. The entries in each column are the stoichiometric coefficients of the metabolites involved in that reaction (negative for consumed metabolites, positive for produced metabolites) [2].

A fundamental constraint in FBA is the steady-state assumption, which posits that the concentration of internal metabolites does not change over time. This is represented by the mass balance equation: Sv = 0 where v is the vector of all reaction fluxes in the network [1] [2]. This equation ensures that for each metabolite, the total rate of production equals the total rate of consumption.

Linear Programming and Constraints

FBA formulates metabolism as a Linear Programming (LP) problem. The steady-state equation, along with additional capacity constraints on reaction fluxes (vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax), defines the "solution space" of all possible metabolic flux distributions that the network can achieve [1] [2].

The LP problem is solved to find a single flux distribution that optimizes a defined biological goal. The general formulation is:

- Objective: Maximize/Minimize Z = cTv

- Subject to: Sv = 0 and vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax

Here, c is a vector of weights that defines the objective function, specifying which reaction(s) are to be optimized [2].

Comparative Analysis of Objective Functions

The choice of objective function is paramount, as it steers the optimization toward a particular flux distribution within the solution space. Different biological assumptions and research questions call for different objective functions. The table below summarizes commonly used objective functions and their applications.

Table: Comparison of Key Objective Functions in Flux Balance Analysis

| Objective Function | Mathematical Form (cTv) | Biological Rationale | Typical Application Context | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximize Biomass Production | Maximize flux through the biomass reaction | Simulates natural selection for maximal growth rate | Standard for predicting microbial growth in nutrient-rich conditions | Often produces realistic growth rates; may not predict all internal fluxes accurately [3] |

| Maximize ATP Production | Maximize total flux of ATP-generating reactions | Assumes cells evolve to maximize energy yield | Studying energy metabolism; conditions where energy is limiting | Can improve predictions in energy-limited environments or for lifespan analysis in yeast models [3] |

| Minimize Total Flux (Parsimony) | Minimize the sum of absolute values of all fluxes | Assumes cells have evolved to be metabolically efficient (use minimal protein/enzyme cost) | Finding the most efficient pathway usage; often used as a secondary objective | Can refine predictions by eliminating unrealistic flux loops; improves lifespan predictions in yeast models [3] |

| Minimize Nutrient Uptake | Minimize flux of a substrate uptake reaction (e.g., glucose) | Assumes efficiency in substrate utilization | Modeling nutrient-scarce environments | Directly optimizes for substrate use efficiency rather than a growth or energy output |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | e.g., Maximize growth, then minimize total flux (lexicographic method) | Combines multiple selective pressures | Generating more realistic, context-specific flux distributions | Can provide a more balanced and biologically realistic solution than single objectives [3] |

Experimental Protocols for FBA

The following is a generalized protocol for setting up and solving an FBA problem, which can be implemented using computational tools like the COBRA Toolbox in MATLAB or similar packages in Python [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a typical FBA simulation.

Detailed Methodology

- Define the Metabolic Network Reconstruction: The foundation of any FBA study is a high-quality genome-scale metabolic reconstruction. This model is represented as a stoichiometric matrix S [2].

- Apply Physiochemical Constraints:

- Define the Biological Objective: Select an appropriate objective function based on the biological question. For example, to simulate maximal growth, the vector c is set to zero for all reactions except the biomass reaction, which is set to 1 [2].

- Solve the Linear Programming Problem: Use an LP solver to find the flux distribution v that satisfies all constraints and optimizes the objective function Z [1] [2].

- Output and Validation: The primary output is the flux vector v. The predictions, such as growth rate or metabolite secretion, should be compared with experimental data (e.g., from chemostat cultures) for validation [4] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key resources required for conducting FBA studies.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | A computational representation of all known metabolic reactions in an organism. | Models for E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and H. sapiens are publicly available [2]. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | The core mathematical structure of the model, defining metabolite-reaction relationships. | Typically stored in a data file (e.g., SBML format) and loaded into the analysis tool [2]. |

| Linear Programming Solver | Software that performs the numerical optimization to find the optimal flux distribution. | Solvers are integrated into toolboxes like the COBRA Toolbox (for MATLAB) or Cobrapy (for Python) [1] [2]. |

| Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) Toolbox | A suite of functions for performing FBA and other constraint-based methods. | A standard toolkit in the field; requires a MATLAB environment [2]. |

| Experimental Flux Data | Data used for validating model predictions, such as growth rates or uptake/secretion rates. | Crucial for assessing the predictive power of different objective functions [4]. |

| Python Programming Environment | An open-source platform for implementing custom FBA protocols and analyses. | Libraries like NumPy and SciPy are used for matrix operations and linear programming [1]. |

In the field of systems biology and metabolic engineering, constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) methods have become indispensable for predicting cellular behavior. At the heart of these computational approaches lies the metabolic objective function, a mathematical representation that defines the biological goals a cell is optimizing under specific conditions. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), the most widely used constraint-based method, relies on these objective functions to predict steady-state metabolic flux distributions through genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) [5] [6]. The selection of an appropriate objective function is paramount, as it directly influences the accuracy of phenotypic predictions, from microbial strain improvement to drug discovery [7] [8].

While rapidly proliferating cells like microbes or cancer cells are often assumed to prioritize biomass maximization, this review demonstrates that cellular objectives are far more nuanced. Different cell types, including quiescent human cells, stem cells, and cancer cells, exhibit distinct metabolic priorities that support their specialized functions [7]. This comparative analysis examines three fundamental categories of metabolic objectives—biomass production, energy generation, and product synthesis—evaluating their formulations, applications, and performance across various biological contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Objective Function Types

Biomass Objective Function

The biomass objective function (BOF) represents the biosynthetic requirements for cellular reproduction, mathematically describing the rate at which all biomass precursors are synthesized in the correct proportions to support growth [5]. Formulating a BOF requires detailed knowledge of cellular composition, including macromolecular weights of proteins, RNA, DNA, lipids, and carbohydrates, along with associated energetic costs for polymerization [5].

Formulation Levels:

- Basic Level: Defines macromolecular content (weight fractions of protein, RNA, lipid, etc.) and their metabolic building blocks.

- Intermediate Level: Incorporates biosynthetic energy requirements (e.g., 2 ATP + 2 GTP per amino acid incorporated into protein).

- Advanced Level: Includes vitamins, cofactors, and minimal "core" cellular components essential for viability [5].

The BOF is particularly effective for predicting growth rates and essential genes in rapidly proliferating cells. However, its limitations become apparent when modeling specialized mammalian cell types or non-growth associated metabolic states [7].

Energy-Based Objectives

Energy-centric objectives prioritize ATP maximization or redox balance over biomass production, reflecting situations where cellular survival rather than proliferation is paramount. Multiple studies have demonstrated that minimizing redox potential or maximizing ATP yield per flux unit can better predict metabolic phenotypes under certain conditions [5].

Hausser et al. noted that environmental constraints create selection pressures that force phenotypic switching. For instance, late-stage cancers under hypoxic conditions tend to optimize survival, contrasting with early-stage cancers that are proliferation-optimized due to ample oxygen availability [7]. In continuous cultures with nutrient scarcity, linear maximization of ATP yield achieved higher predictive accuracy than growth maximization [5].

Product Synthesis Objectives

Biotechnological applications often employ product synthesis objectives to maximize the yield of specific metabolites. This approach is valuable in industrial microbiology for optimizing production of compounds like isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) in Clostridium species [8]. Unlike biomass objectives that represent a "selfish" cellular goal, product synthesis objectives typically represent engineering interventions where cellular metabolism is redirected toward a non-native goal.

The TIObjFind framework addresses the challenge of predicting such metabolic shifts by identifying pathway-specific weighting factors that indicate how cells prioritize reactions under different environmental conditions [8].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Objective Functions Across Biological Systems

| Objective Function | Best Application Context | Predictive Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Maximization | Rapidly proliferating cells (microbes, cancer cells) | Growth rate prediction, gene essentiality in optimal conditions | Poor performance for quiescent cells, neglects metabolic trade-offs |

| ATP Maximization | Energy-limited conditions, hypoxic environments | Survival phenotype prediction, stationary phase metabolism | May overpredict ATP-generating futile cycles |

| Redox Minimization | Aerobic respiration, oxidative stress conditions | E. coli central carbon metabolism under aerobic batch growth [5] | Limited to specific metabolic states |

| Product Synthesis | Industrial bioprocessing, metabolic engineering | High-yield strain design, pathway flux optimization | Requires genetic/regulatory interventions for implementation |

Methodologies for Objective Function Inference

Computational Frameworks

Advanced computational frameworks have been developed to infer context-specific objective functions from experimental data:

ObjFind Framework: This approach introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to an objective function. By maximizing a weighted sum of fluxes while minimizing deviations from experimental data, ObjFind interprets flux distributions in terms of optimized metabolic objectives [8].

TIObjFind Framework: Building on ObjFind, this topology-informed method integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA. It constructs flux-dependent weighted reaction graphs to analyze metabolic behavior across different system states, enhancing interpretability of complex networks [8].

REMI Method: The Relative Expression and Metabolomic Integration approach incorporates multi-omics data into thermodynamically curated GEMs. REMI translates differential gene expression and metabolite abundance data into differential flux constraints, significantly reducing the solution space of feasible fluxes [6].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Validating predicted objective functions requires integration of computational and experimental approaches:

13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): This established experimental technique uses 13C-labeled substrates to track metabolite fluxes through central carbon metabolism, providing ground-truth data for validating computational predictions [6].

Isotopomer Analysis: Advanced mass spectrometry approaches measure isotopic labeling patterns in intracellular metabolites, enabling experimental determination of flux distributions for comparison with model predictions [5].

Multi-omics Integration: REMI and similar methods leverage transcriptomic and metabolomic data to constrain flux predictions. Performance is quantified by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients between predicted and experimentally measured fluxes, with REMI achieving r = 0.79 in E. coli models [6].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Objective Function Validation

| Methodology | Data Output | Resolution | Integration with Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-MFA | Intracellular flux maps for central metabolism | Pathway-level | Gold standard for validation of predicted fluxes |

| Gene Expression Profiling | Transcript abundance for metabolic genes | Genome-wide | Constrains reaction capacity in REMI, iMAT |

| Quantitative Metabolomics | Absolute metabolite concentrations | System-wide | Enables thermodynamic constraints (TFA) |

| Flux Variability Analysis | Range of possible fluxes for each reaction | Network-wide | Identifies invariant reactions and trade-offs |

Research Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Multi-Omics Integration Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the workflow for integrating multi-omics data to infer cellular objective functions, as implemented in methods like REMI and TIObjFind.

Cellular Trade-offs and Pareto Optimality

Biological systems face fundamental trade-offs in optimizing multiple objectives simultaneously. The concept of Pareto optimality describes how cells allocate limited resources between competing goals such as growth and survival.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Objective Function Studies

| Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioCyc Database | Bioinformatics Platform | Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs) with curated metabolic networks | Metabolic reconstruction, pathway analysis [9] |

| EcoCyc | Tier 1 PGDB | Manually curated E. coli database with 44,000+ literature citations | Gold standard for bacterial metabolic studies [9] |

| MetaCyc | Metabolic Pathway DB | Curated metabolic pathways from all domains of life (76,000+ publications) | Reference database for pathway prediction [9] |

| Pathway Tools Software | Metabolic Reconstruction | Creates organism-specific PGDBs from genome data | Generation of new metabolic models [9] |

| MetaFlux | FBA Module | Creates quantitative metabolic models from PGDBs using FBA | Constraint-based modeling and flux prediction [9] |

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Isotopic Tracers | Enables experimental flux measurement via 13C-MFA | Validation of computational flux predictions [6] |

| Gibbs Free Energy Data | Thermodynamic Constraints | Incorporates reaction thermodynamics into FBA | Reduction of solution space in TFA [6] |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that no single objective function universally predicts metabolic behavior across all biological contexts. The performance of biomass, energy, and product synthesis objectives depends critically on cellular specialization, environmental conditions, and biological priorities. While biomass maximization effectively models proliferating microbes, energy-centric objectives better predict survival states, and product synthesis objectives drive biotechnological applications.

Advanced methods that integrate multi-omics data and identify context-specific Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) represent the future of objective function determination. Frameworks like TIObjFind and REMI significantly enhance flux prediction accuracy by incorporating regulatory constraints and thermodynamic principles [6] [8]. As systems biology continues to advance, the development of condition-specific, dynamic objective functions will be crucial for applications ranging from drug discovery to personalized medicine and sustainable bioproduction.

Why the Objective Function is Crucial for Predicting Phenotypes

In the field of computational biology, accurately predicting phenotypes from genotypes and environmental factors is a fundamental challenge with significant implications for medicine, biotechnology, and basic research. The choice of objective function—the mathematical expression that a computational model aims to optimize—is a critical determinant of the accuracy and biological relevance of these predictions. This guide compares the performance of different modeling paradigms, from traditional constraint-based methods to modern machine learning approaches, highlighting how their underlying objective functions influence predictive power.

The Fundamental Role of an Objective Function

In computational models, the objective function formally defines the presumed cellular goal. In metabolic models, for instance, this often involves maximizing biomass production or ATP yield. The core hypothesis is that cellular behavior can be predicted by assuming the organism optimizes this function. An accurate objective function leads to predictions that match experimental data; an inaccurate one can render a model biologically implausible.

The challenge is that a single, static objective function may not capture the dynamic and adaptive nature of living systems. Cells shift their metabolic priorities in response to environmental changes, and a function that works well in one condition may fail in another. This limitation has driven the development of more sophisticated frameworks for identifying and testing objective functions. [8] [10]

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Frameworks

The table below summarizes the core methodologies, key features, and primary challenges associated with different approaches to phenotype prediction.

| Modeling Approach | Core Methodology | Key Feature | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional FBA [8] | Linear Programming | Maximizes a single, pre-defined reaction (e.g., biomass). | Struggles to capture flux variations under different conditions. |

| TIObjFind Framework [8] [10] | Optimization + Topology Analysis | Infers objective functions from data using Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). | Requires experimental flux data for training. |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) [11] | Machine Learning (Supervised) | Learns the relationship between flux cone geometry and phenotypes. | Requires substantial computational resources for sampling. |

| Genomic Prediction (ML) [12] [13] | Machine Learning (e.g., SVR, GBM) | Models complex, non-linear genotype-phenotype relationships. | Performance can be affected by population structure in the data. |

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Comparisons

Prediction Accuracy for Metabolic Gene Essentiality

A critical test for metabolic models is accurately predicting which genes are essential for survival. The following table compares the performance of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and the machine learning method Flux Cone Learning (FCL) in predicting gene essentiality in E. coli. [11]

| Prediction Method | Organism | Reported Accuracy | Key Objective/Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | E. coli | 93.5% | Biomass maximization |

| Flux Cone Learning (FCL) | E. coli | 95.0% | Geometry of the metabolic "flux cone" |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Higher-order organisms | Lower performance | Relies on an unknown optimality objective |

Prediction Accuracy for Complex Livestock Traits

Beyond microbes, the choice of statistical objective (or model) is crucial for predicting complex polygenic traits. The table below shows the performance of various methods in predicting feed efficiency in Nellore cattle. [13]

| Prediction Method | Category | Relative Prediction Accuracy vs. ST-GBLUP |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Trait GBLUP (MTGBLUP) | Parametric | +13.7% |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Machine Learning | +14.6% |

| Multi-Layer Neural Network (MLNN) | Machine Learning | +8.9% |

| Bayesian Regression Methods | Parametric | Benchmark (lower accuracy) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of how these methods are implemented, we outline the key experimental workflows.

Protocol for the TIObjFind Framework

The TIObjFind framework integrates metabolic pathway analysis with FBA to identify context-specific objective functions. [8] [10]

a. Single-Stage Optimization:

- Step 1: The framework solves an optimization problem that minimizes the squared difference between predicted metabolic fluxes ((v)) and experimental flux data ((v^{exp})), while simultaneously maximizing a hypothesized objective function ((c^{obj} \cdot v)).

- Step 2: This step identifies a candidate set of "Coefficients of Importance" (CoIs) that define the contribution of each reaction to the cellular objective.

b. Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Generation:

- The optimized flux distribution is mapped onto a directed, weighted graph called a Mass Flow Graph. In this graph, nodes represent metabolic reactions, and edges represent the flow of metabolites between them.

c. Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) via Minimum Cut:

- A graph theory algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) is applied to the MFG to find the "minimum cut" between a source node (e.g., glucose uptake) and a target node (e.g., product secretion).

- This minimum cut identifies the set of reactions that are most critical for the desired metabolic output, refining the Coefficients of Importance and providing a topology-informed objective function.

Protocol for Flux Cone Learning (FCL)

Flux Cone Learning uses a data-driven approach to predict deletion phenotypes without a pre-defined objective function. [11]

a. Define the Metabolic Space:

- A Genome-Scale Model (GEM) defines the system of linear equations ((S v = 0)) and flux bounds that constitute the "flux cone" of possible metabolic states.

b. Monte Carlo Sampling:

- For each gene deletion, the corresponding reactions are constrained to zero. A Monte Carlo sampler then generates a large number (e.g., 100-5000) of random, feasible flux distributions within the resulting deformed flux cone.

- Each set of samples characterizes the geometry of the metabolic space for that specific deletion.

c. Supervised Model Training:

- The flux samples from all deletions are compiled into a feature matrix. Each sample is labeled with the corresponding experimental fitness score from a deletion screen.

- A supervised machine learning model (e.g., a Random Forest classifier) is trained on this dataset to learn the correlation between the shape of the flux cone and the phenotypic outcome.

d. Prediction and Aggregation:

- To predict the phenotype of a new deletion, the model is applied to multiple flux samples from its flux cone. The final prediction is determined by aggregating these sample-level predictions (e.g., via majority voting).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful implementation of the methods described requires a combination of computational tools and biological data resources.

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Relevant Method |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | A mathematical representation of an organism's metabolism; the core scaffold for constraint-based methods. | FBA, TIObjFind, FCL [8] [11] |

| Experimental Flux Data ((v^{exp})) | Quantified metabolic reaction rates from experiments; used to train and validate inferred objective functions. | TIObjFind [10] |

| Gene Deletion Fitness Screen | High-throughput experimental data measuring the growth effect of gene knockouts; provides labels for supervised learning. | FCL [11] |

| Monte Carlo Sampler | Software that randomly samples the high-dimensional space of possible flux distributions in a metabolic network. | FCL [11] |

| MATLAB / Python (with pySankey) | Programming environments for implementing optimization frameworks, graph analysis, and result visualization. | TIObjFind [10] |

| Random Forest Classifier | A versatile machine learning algorithm for classification and regression tasks, known for good performance and interpretability. | FCL, Genomic Prediction [11] [13] |

The evidence demonstrates that the choice and formulation of the objective function are pivotal for accurate phenotypic prediction. While traditional FBA with a fixed objective like biomass maximization provides a strong baseline, its performance is limited when cellular priorities shift. Emerging frameworks like TIObjFind address this by inferring context-specific objective functions directly from experimental data, thereby enhancing model fidelity. Furthermore, machine learning methods like Flux Cone Learning and Support Vector Regression show that bypassing a single pre-defined objective in favor of learning the relationship between system states and outcomes can yield superior, state-of-the-art accuracy. The selection of the right objective function, therefore, remains a cornerstone of successful phenotypic prediction in computational biology.

Evolutionary Arguments and Biological Rationales for Common Objectives

Selecting appropriate objective functions remains a fundamental challenge in constraint-based metabolic modeling, particularly Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). The core premise of FBA relies on mathematical optimization to predict metabolic fluxes, requiring assumptions about cellular goals shaped by evolutionary pressures [3]. This comparative guide examines the evolutionary arguments and experimental validations supporting common objective functions, providing researchers with a structured framework for selecting biologically relevant objectives across different applications.

The evolutionary rationale for objective function selection stems from the concept that natural selection favors metabolic strategies that enhance survival and reproduction. However, this optimization process operates within complex constraints and trade-offs. As noted in critiques of evolutionary biology, "Evolutionarily, metabolism is most likely optimized for overall robustness across many conditions, rather than a single condition-specific objective" [14]. This perspective challenges simplistic assumptions about cellular optimization and underscores the need for condition-specific objective function selection.

Comparative Analysis of Common Objective Functions

Theoretical Evolutionary Rationales

Table 1: Evolutionary Arguments for Common Objective Functions in Metabolic Modeling

| Objective Function | Evolutionary Rationale | Supported Organisms/Conditions | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal Biomass Production | Optimizes reproductive capacity by maximizing growth rate; assumes selection favors rapid proliferation | E. coli, S. cerevisiae in optimal growth conditions [3] [14] | Poor predictor under stress, nutrient limitation, or stationary phase |

| Maximal ATP Production | Maximizes energy currency for cellular maintenance and biosynthesis; reflects fundamental energy optimization | Budding yeast in early life phases [3] | May overlook biosynthetic requirements and redox balance |

| Parsimonious Enzyme Usage | Reflects protein synthesis cost optimization; conserves resources for other cellular processes | Improves lifespan predictions in yeast [3] | Requires additional constraints for accurate flux distribution |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | Mirrors evolutionary trade-offs between competing cellular goals | Condition-dependent responses in multiple organisms [3] [8] | Increased computational complexity and parameterization |

| Yield Optimization | Maximizes resource use efficiency in nutrient-limited environments | Microbes in constant nutrient environments [3] | May not predict metabolic behavior in fluctuating environments |

Experimental Validation Across Organisms

Table 2: Experimental Support for Objective Functions Across Biological Systems

| Organism/System | Optimal Objective Function | Experimental Validation Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Aging Model) | Parsimonious maximal growth with energy cost minimization | Replicative lifespan measurements and division timing [3] | Combined objectives improved lifespan predictions by increasing respiratory activity and antioxidative capacity |

| E. coli | Condition-dependent: Maximal energy or biomass production | C-based flux data fitting across conditions [3] | Most accurate objectives varied with environmental conditions |

| C. acetobutylicum (Fermentation) | Pathway-specific weighted objectives | Fluxomic data comparison using TIObjFind framework [8] | Stage-specific metabolic priorities required different objective weightings |

| A. thaliana (Cold Acclimation) | Flux sampling without predefined objective | Metabolite measurements, CO₂ uptake, carbon allocation tracking [14] | Eliminated observer bias; revealed fumarate and GABA importance in cold response |

| Multi-species IBE system | Hybrid objective with importance coefficients | Experimental product secretion rates [8] | Weighted combination of fluxes better captured community metabolic interactions |

Methodological Approaches for Objective Function Identification

Computational Frameworks and Algorithms

Several advanced computational frameworks have been developed to identify appropriate objective functions, moving beyond simple assumptions:

The TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) framework integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer metabolic objectives from experimental data [8]. This method determines Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to cellular objectives, using network topology and pathway structure to analyze metabolic behavior across different system states.

The REMI (Relative Expression and Metabolomic Integrations) method represents another approach, integrating relative gene expression, metabolite abundance, and thermodynamic constraints into genome-scale models [6]. This multi-omic integration significantly reduces the solution space of feasible fluxes and improves prediction accuracy.

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows for Traditional FBA versus Flux Sampling Approaches

Flux Sampling as an Objective-Free Alternative

Flux sampling has emerged as a powerful alternative to objective-dependent methods, particularly for studying metabolism under changing environmental conditions [14]. This approach generates probability distributions of steady-state reaction fluxes without assuming a specific cellular objective, thereby eliminating observer bias.

The Coordinate Hit-and-Run with Rounding (CHRR) algorithm has demonstrated superior efficiency for flux sampling, being 2.5-8 times faster than alternative algorithms depending on model complexity [14]. This method enables comprehensive exploration of metabolic solution spaces, providing insights into network robustness and flexibility without predefined objectives.

Experimental Protocols for Objective Function Validation

Multi-Scale Model Validation for Aging Studies

For replicative aging studies in yeast, researchers have employed a multi-scale mathematical model integrating cellular metabolism, nutrient sensing, and damage accumulation [3]. The protocol involves:

- Model Construction: Develop enzyme-constrained FBA models of central carbon metabolism including ROS creation

- Regulatory Network Integration: Implement Boolean representations of key signaling pathways (Snf1, PKA, TOR, Yap1, Sln1)

- Dynamic Simulation: Connect optimal fluxes to ODE models of damage accumulation and growth

- Validation Metrics: Compare predicted number of cell divisions and generation time against experimental measurements

- Objective Function Testing: Systematically test individual and combined objective functions against lifespan data

This approach confirmed that maximal growth is essential for realistic lifespans, while parsimonious solutions or additional energy cost optimization further improved predictions [3].

Flux Sampling Protocol for Environmental Responses

For studying metabolic responses to environmental changes such as temperature acclimation in plants, the following flux sampling protocol is recommended [14]:

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., A. thaliana models)

- Experimental Constraints: Incorporate measured CO₂ uptake and organic carbon accumulation data

- Sampling Implementation: Apply CHRR algorithm with appropriate thinning constants

- Convergence Diagnostics: Verify using Raftery & Lewis and IPSRF diagnostics

- Solution Space Analysis: Compare flux distributions between conditions

- Biological Interpretation: Identify key metabolic changes supporting acclimation

This protocol revealed how regulated interplay between diurnal starch and organic acid accumulation defines plant acclimation to cold, confirming fumarate accumulation and predicting GABA's role in metabolic signaling [14].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Objective Function Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constraint-Based Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox, FlexFlux | Implement FBA, FVA, and regulatory constraints | Metabolic network simulation and analysis [8] |

| Flux Sampling Algorithms | CHRR, ACHR, OPTGP | Explore solution spaces without objective functions | Analysis of metabolic robustness and plasticity [14] |

| Multi-Omics Integration Methods | REMI, GIM3E, iReMet-Flux | Incorporate transcriptomic, metabolomic data | Context-specific model construction [6] |

| Objective Function Identification | TIObjFind, ObjFind | Infer cellular objectives from experimental data | Data-driven objective function discovery [8] |

| Validation Techniques | 13C-MFA, Isotopomer Analysis | Experimental flux measurement | Objective function validation [6] |

| Convergence Diagnostics | Raftery & Lewis, IPSRF | Assess flux sampling convergence | Quality control for sampling studies [14] |

The evolutionary arguments supporting objective function selection continue to evolve with advancing computational methods and experimental techniques. While traditional objectives like maximal biomass production remain valid for optimal growth conditions, more sophisticated approaches including multi-objective optimization, condition-specific weighting, and objective-free flux sampling provide more biological realism for complex environments.

The fundamental insight from evolutionary biology—that natural selection optimizes for robustness across multiple conditions rather than maximal performance in any single condition—should guide objective function selection [14]. By aligning computational models with these evolutionary principles, researchers can enhance predictive accuracy and biological relevance in metabolic modeling for basic research and applied biotechnology.

Challenges in Predicting Individual Fluxes and Enzyme Activities

Predicting individual metabolic fluxes and enzyme activities remains a significant hurdle in systems biology, despite comprehensive knowledge of metabolic network structures. The core challenge stems from the complex interplay of multiple regulatory layers that control metabolic flux, which is the rate at which metabolites are converted in a biochemical network. While the stoichiometry of metabolic networks is well-established for many organisms, the dynamic behavior of metabolism cannot yet be adequately described, predicted, or engineered [15].

This prediction challenge is primarily rooted in several key factors: the influence of kinetic interactions and allosteric control mechanisms that are difficult to comprehensively characterize in vivo; the disconnect between in vitro enzyme properties and their actual behavior within the cellular environment; and the fundamental difficulty in determining whether changes in metabolic flux are driven by alterations in enzyme levels or by other regulatory mechanisms [16] [15]. Unknowns in metabolic flux behavior particularly arise from these kinetic interactions, making it infeasible to exhaustively test every possible enzyme-metabolite interaction in vitro [15].

Comparative Analysis of Flux Prediction Methodologies

Various computational approaches have been developed to address the challenge of flux prediction, each with distinct methodological foundations and limitations. The table below provides a structured comparison of the primary methodologies discussed in the literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Metabolic Flux Prediction Methodologies

| Method | Core Principle | Level of Expression Data Integration | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [4] [17] [3] | Constraint-based optimization of an objective function (e.g., biomass) under steady-state assumptions. | Not inherently integrated; can be used as a constraint. | Choice of objective function significantly impacts results; does not directly incorporate enzyme kinetics or regulation [17] [3]. |

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA [17] [3] | Extends FBA by incorporating constraints based on measured or estimated enzyme usage and capacity. | Proteomic data can constrain enzyme usage (e_i) [3]. | Requires comprehensive enzyme abundance and kinetic (k_cat) data, which is often incomplete [3]. |

| Flux Potential Analysis (FPA) [16] | Integrates relative enzyme levels from the reaction of interest and its network neighbors, weighted by proximity. | Individual reaction & network neighborhood. | Correlates weakly with flux changes; suboptimal predictive power [16]. |

| Enhanced FPA (eFPA) [16] | Improved FPA that integrates expression data at the pathway level rather than for single reactions or the entire network. | Pathway-level. | Outperforms FPA and alternatives; optimal balance between reaction-specific and network-wide analysis [16]. |

The choice of the objective function in FBA-based methods is particularly crucial, as it determines how fluxes are distributed across the network. Studies have systematically tested various objectives, including maximal growth (biomass production), minimal substrate uptake, and maximal ATP production, confirming that this choice is critical for generating realistic predictions of physiological states, such as the replicative lifespan in yeast [17] [3]. No single consensus objective function exists, and the best choice may be condition-dependent [3].

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarking

The development of enhanced Flux Potential Analysis (eFPA) was guided by benchmarking against experimental data. A key dataset fulfilling the requirements for a statistically meaningful analysis came from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast), providing flux estimates for 232 metabolic reactions and associated enzyme levels across 25 different nutrient limitation conditions [16].

A central finding from this systematic evaluation was that flux changes correlate more strongly with pathway-level changes in enzyme levels than with changes in the expression of individual enzymes or network-wide expression profiles [16]. This discovery informed the eFPA algorithm, which integrates enzyme expression data at this optimal pathway level.

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings from Flux-Enzyme Correlation Studies

| Study System | Key Measured Variables | Central Finding | Impact on Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) [16] | - Fluxomic data (232 reactions)- Proteomic data (156 enzymes)- 25 growth conditions | Flux changes are best predicted from changes in enzyme levels of pathways, not individual reactions or the whole network. | Led to the development of eFPA, which uses pathway-level integration for superior predictions [16]. |

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) [17] [3] | - Replicative lifespan (cell divisions)- Generation time- Metabolic flux distributions | The choice of FBA objective function (e.g., maximal growth) is crucial for predicting realistic replicative lifespans. | Connects flux prediction objectives to long-term cellular outcomes like ageing; suggests combining objectives (e.g., parsimonious maximal growth) [17] [3]. |

| Human Tissues [16] | - Proteomic and Transcriptomic data- Predicted tissue metabolic function | eFPA consistently predicts tissue metabolic function using either proteomic or transcriptomic data. | Demonstrates method's robustness and applicability to human data, even handling data sparsity and noisiness in single-cell RNA-seq data [16]. |

The performance of eFPA demonstrates its advantage over other methods. It consistently generates robust predictions of tissue metabolic function in human data using either proteomic or transcriptomic datasets and efficiently handles the sparsity and noisiness inherent in single-cell gene expression data [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol for Yeast Flux-Enzyme Correlation Analysis

This protocol is derived from the study that developed and validated eFPA [16].

- Data Acquisition: Obtain a curated dataset with simultaneous measurements of metabolic fluxes and enzyme levels from the same samples. The benchmark yeast dataset included flux estimates for 232 reactions and 156 enzyme levels across 25 chemostat conditions with different nutrient limitations (e.g., glucose, leucine, nitrogen, phosphate) and growth rates [16].

- Data Preprocessing: Adjust raw flux values for growth rate variations by dividing each flux by the corresponding specific growth rate. This yields relative flux values that are comparable across conditions. Enzyme abundance is typically already normalized as a proportion of total protein [16].

- Correlation Analysis:

- Calculate correlation coefficients between flux and the level of its cognate enzyme for individual reactions.

- Calculate correlation coefficients between flux and a composite expression score for the pathway in which the reaction resides.

- Statistically compare the correlation strengths to determine which level (individual vs. pathway) is more predictive of flux changes [16].

- Algorithm Optimization: Use the findings to optimize the parameters of a predictive algorithm (e.g., FPA). The key is to define the optimal "distance factor" or network neighborhood size (pathway level) over which enzyme expression data should be integrated for the most accurate flux prediction [16].

Protocol for Testing Objective Functions in a Multi-Scale Model

This protocol is based on the work that connected FBA objective functions to yeast replicative ageing [17] [3].

- Model Setup: Employ a multi-scale mathematical model (e.g., yMSA for yeast) that integrates:

- An enzyme-constrained FBA model of central carbon metabolism.

- A regulatory network (e.g., using Boolean logic for nutrient sensing and stress pathways).

- A dynamic model of damage accumulation and cell growth [3].

- Define Optimization Strategy: Implement a two-stage lexicographic optimization:

- First Optimization: Solve the FBA problem for a primary objective function (e.g., maximize biomass reaction).

- Second Optimization: Constrain the solution to the optimal value from the first step (allowing a small flexibility factor, ε) and then optimize a second objective (e.g., minimize total flux, representing enzyme usage parsimony) [3].

- Simulate Ageing: Run the integrated model with different objective function combinations (e.g., maximal growth, maximal ATP, minimal NADH, and their parsimonious versions) to simulate the entire replicative lifespan of a yeast cell [17] [3].

- Output Analysis: For each simulation, record key observables:

- Replicative Lifespan (RLS): The total number of cell divisions.

- Generation Time: The time between divisions.

- Metabolic Flux Distributions: Particularly in different metabolic phases (e.g., early vs. late life) [3].

- Validation: Compare the simulated RLS and generation times against established experimental data for wild-type yeast cells to determine which objective function produces the most realistic physiological predictions [17].

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing and validating flux prediction methods.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Flux Prediction Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance in Flux Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Chemostat Cultures [16] | A bioreactor that maintains microbial cells in steady-state growth at a fixed dilution rate. | Essential for acquiring consistent and reproducible omics data (fluxomic, proteomic) across multiple controlled growth conditions. |

| Stoichiometric Genome-Scale Model (GEM) [17] [3] | A computational reconstruction of an organism's metabolism, detailing reaction stoichiometry and network connectivity. | Serves as the core structural framework for constraint-based methods like FBA and eFPA. |

| Enzyme-Abundance Datasets [16] | Quantitative measurements of protein levels, typically via mass spectrometry. | Used as constraints in ecFBA or as input data for correlation analysis and predictive algorithms like eFPA. |

| Fluxomic Data [16] | Experimental measurements of intracellular metabolic reaction rates. | Serves as the "ground truth" gold standard for validating and benchmarking the accuracy of flux prediction methods. |

| Curated Yeast Benchmark Dataset [16] | A publicly available dataset containing paired flux and enzyme abundance measurements across 25 conditions. | A critical resource for the initial development, parameterization, and validation of new predictive algorithms. |

| Multi-Scale Modelling Framework (e.g., yMSA) [3] | An integrated computational model combining metabolism, regulation, and physiology. | Allows for testing the physiological consequences of different flux distributions and objective functions on outcomes like ageing. |

Diagram 2: Interrelationship between core methodological challenges and broader research directions.

From Traditional FBA to Cutting-Edge Machine Learning Flux Predictors

In the field of systems biology, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a fundamental constraint-based modeling approach for analyzing metabolic networks at the genome scale. FBA calculates flow of metabolites through a metabolic network, enabling prediction of organism's growth, metabolic production, and physiological properties. The core principle of FBA involves solving for a flux distribution that satisfies mass-balance and steady-state constraints while optimizing a specified cellular objective. The selection of an objective function is therefore crucial as it represents the biological goal driving the metabolic behavior and ultimately determines the predicted flux distribution.

While numerous objective functions have been proposed, three have emerged as particularly influential: maximal growth (biomass production), ATP production, and parsimonious solutions (minimization of total flux or enzyme usage). These functions are motivated by different evolutionary hypotheses about cellular optimization principles. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these common objective functions, examining their underlying assumptions, performance characteristics, and applicability across different biological contexts and organism types.

Comparative Analysis of Common Objective Functions

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, applications, and limitations of the three primary objective functions discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Objective Functions in Flux Balance Analysis

| Objective Function | Underlying Principle | Typical Applications | Performance Highlights | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal Growth (Biomass) | Maximizes biomass production, reflecting evolutionary pressure for rapid reproduction | - Microbial growth prediction- Nutrient-rich conditions- Standard FBA benchmarks | - Essential for realistic yeast replicative lifespans [3]- Accurate for E. coli and yeast in standard conditions [3] | - Often unrealistic under substrate excess [18]- Overestimates growth in mammalian cells [19] |

| ATP Production | Maximizes or minimizes ATP yield, representing energy efficiency goals | - Energy metabolism studies- Conditions with energy constraints- Multi-objective optimization | - Improves lifespan predictions in yeast when combined with growth [3]- Condition-dependent accuracy [3] | - Rarely optimal as sole objective [3] |

| Parsimonious Solution | Minimizes total flux or enzyme usage, representing resource efficiency | - Enzyme-limited conditions- Substrate excess scenarios- Multi-stage optimizations | - Increases respiratory activity in yeast [3]- Enhances antioxidative activity in early life [3]- Better fits C. butyricum glycerol culture [18] | - Requires precise flexibility constraints to maintain feasibility [3] |

Experimental Validation and Performance Data

Quantitative Performance Across Organisms

Experimental validations across multiple organisms demonstrate how the performance of objective functions varies significantly with biological context and environmental conditions.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Objective Functions Across Organisms

| Organism | Condition | Objective Function | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) | Replicative ageing | Maximal growth | Replicative lifespan | Essential for realistic lifespans | [3] |

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) | Replicative ageing | Parsimonious + maximal growth | Number of cell divisions | ~23 divisions (reference cell) | [3] |

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) | Replicative ageing | Parsimonious + maximal growth | Average generation time | ~1.5 hours | [3] |

| C. butyricum | Glycerol culture | Maximal growth | Biomass yield error | 300% overestimation | [18] |

| C. butyricum | Glycerol culture | Maximal growth | PDO yield error | 100% error | [18] |

| C. butyricum | Glycerol limitation | Biomass per enzyme usage | Growth prediction | Accurate phenotype state | [18] |

| C. butyricum | Glycerol excess | Growth + minimized enzyme/ATP usage | Growth prediction | Accurate phenotype state | [18] |

| CHO cells | Standard culture | Maximal growth | Growth prediction | Significant overestimation | [19] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Multi-Scale Modeling of Yeast Replicative Ageing

The enzyme-constrained FBA approach integrated within a multi-scale model of yeast replicative ageing provides a robust framework for evaluating objective functions [3].

Methodology:

- Metabolic Modeling: Implement an enzyme-constrained FBA model of central carbon metabolism with constraints on total enzyme pool

- Regulatory Network Integration: Connect metabolic outputs to a vector-based Boolean model of nutrient sensing pathways (Snf1, PKA, TOR, Yap1, Sln1)

- Dynamic Simulation: Feed optimal fluxes into an ODE model of damage accumulation and cell growth, solved iteratively over time

- Division Tracking: Monitor biomass production until FBA becomes infeasible (cell death), recording division count and generation time

Key Constraints and Parameters:

- Total enzyme pool limited by σfPtot (average saturation σ × fraction of enzymes covered f × total protein content Ptot)

- Non-metabolic damage formation rate (f0) = 0.0001

- Damage repair rate (r0) = 0.0005

- Regulation factor = 0.04

Lexicographic Optimization Strategy: The approach utilizes successive optimizations with controlled flexibility [3]:

- Optimize primary objective (e.g., maximal growth)

- Constrain primary objective to optimal value with flexibility factor ε₁ ≤ 1

- Optimize secondary objective (e.g., flux minimization) within this constrained solution space

- Allow flexibility ε₂ ≤ 1 for subsequent regulation steps to maintain feasibility

Protocol: Genome-Scale Model Reconstruction and Validation for Clostridium butyricum

The iCbu641 model reconstruction and validation demonstrates condition-dependent performance of objective functions [18].

Model Reconstruction:

- Draft Construction: Build initial model from RAST annotation (641 genes, 365 enzymes, 671 reactions, 606 metabolites)

- Gap Analysis: Identify 303 blocked metabolites using GapFind

- Curation: Add 59 reactions based on experimental fermentation evidence and curated GSM models

- Biomass Reaction Formulation: Adapt from C. beijerinckii with inclusion of proton formation for charge balance

Final Model Specifications:

- 641 genes, 891 reactions, 701 metabolites

- Elemental composition per C atom: CH₁.₆₂₄O₀.₄₅₆N₀.₂₁₆P₀.₀₃₃S₀.₀₀₄₇

- Includes PDO dehydrogenase (EC.1.1.1.202) and glycerol dehydratase (EC.4.2.1.30)

Validation Approach:

- Compare flux distribution predictions with experimental proteomic data (84% agreement achieved)

- Evaluate phenotype states under different culture conditions

- Test robustness through enzyme deletions and biomass composition variations

Visualization of Methodologies and Metabolic Relationships

Flux Balance Analysis with Multi-Stage Optimization

FBA Multi-Stage Optimization Workflow: This diagram illustrates the lexicographic optimization approach where a primary objective is optimized first, followed by a secondary objective within a constrained solution space with defined flexibility factors [3].

Multi-Scale Integration of Metabolism and Ageing

Multi-Scale Model Integration: This workflow shows how metabolic models are integrated with regulatory networks and dynamic damage accumulation to simulate cellular ageing processes, enabling evaluation of how objective functions impact lifespan [3].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Objective Function Validation

| Item | Type | Function/Application | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Constrained FBA | Computational Framework | Incorporates enzyme kinetics and capacity limitations into FBA | Total enzyme pool constraint: σfPtot [3] |

| Lexicographic Optimization | Computational Method | Solves multi-objective optimization with priority ranking | Two-stage approach with flexibility factors ε₁, ε₂ [3] |

| Genome-Scale Model iCbu641 | Metabolic Model | Clostridium butyricum-specific network for PDO production | 641 genes, 891 reactions, 701 metabolites [18] |

| Boolean Regulatory Network | Computational Model | Simulates nutrient sensing and stress response pathways | Snf1, PKA, TOR, Yap1, Sln1 pathways [3] |

| Dynamic ODE Model | Computational Model | Simulates damage accumulation and cellular growth over time | Parameters: f0=0.0001, r0=0.0005 [3] |

| TIObjFind Framework | Computational Tool | Identifies context-specific objective functions from data | Uses Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) [10] |

| Uptake-rate Objective Functions (UOFs) | Computational Approach | Minimizes non-essential nutrient uptake for mammalian cells | Resolves essential amino acid limitations in CHO cells [19] |

| ThermOptCOBRA | Computational Tool | Ensures thermodynamic feasibility in flux predictions | Eliminates thermodynamically infeasible cycles [20] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that the performance of objective functions in FBA is highly context-dependent, varying with organism type, environmental conditions, and biological process being studied. Maximal growth serves as a reliable objective for microbial systems under standard conditions but frequently fails in mammalian cells or under substrate excess. ATP production objectives rarely stand alone but can significantly enhance predictions when combined with other objectives. Parsimonious solutions consistently improve predictions across diverse contexts by incorporating constraints on cellular resources.

For researchers designing FBA studies, the following evidence-based recommendations emerge:

- For microbial growth prediction in standard conditions, maximal growth with parsimonious enzyme usage provides the most accurate results

- For mammalian cells or conditions with multiple essential nutrients, uptake-rate objective functions (UOFs) overcome limitations of traditional biomass maximization

- For substrate excess conditions or enzyme-limited scenarios, parsimonious solutions that minimize total flux or enzyme usage better capture cellular physiology

- For dynamic processes like ageing, multi-objective approaches combining growth with energy production or flux minimization yield the most biologically realistic simulations

The ongoing development of data-driven frameworks like TIObjFind that automatically infer objective functions from experimental data represents a promising direction for the field, potentially moving beyond predefined objective functions to context-specific optimization principles [10].

Multi-Objective Optimization and Hybrid Approaches

The accurate prediction of cellular behavior, particularly metabolic fluxes, is a cornerstone of modern systems biology and drug development. This process is inherently a multi-objective optimization problem (MOOP), where researchers must balance conflicting goals such as maximizing biomass production, minimizing energy expenditure, and optimizing product yield simultaneously [8]. Traditional single-objective approaches often fail to capture the complex trade-offs that cells make in response to environmental changes, leading to inaccurate predictions. The emergence of hybrid approaches that combine mechanistic models with machine learning represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, offering enhanced predictive power while maintaining biological plausibility [21].

This comparative analysis examines the landscape of multi-objective optimization methodologies for flux prediction, with particular emphasis on their application in drug discovery and metabolic engineering. We objectively evaluate the performance of three prominent frameworks—neural-mechanistic hybrids, topology-informed optimization, and evolutionary algorithms—providing researchers with a comprehensive guide to selecting appropriate methodologies for specific research scenarios. The performance of these approaches is assessed through standardized benchmarking tasks and quantitative metrics, enabling direct comparison of their respective strengths and limitations in addressing the complex challenges of biological system optimization.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Objective Optimization Frameworks

Performance Benchmarking of Optimization Approaches

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Multi-Objective Optimization Frameworks

| Optimization Framework | Prediction Accuracy (%) | Computational Efficiency | Key Performance Metrics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural-Mechanistic Hybrid (AMN) | N/A | Training time: 25.7s [22] | CPU usage: 10.55% [22]; Outperforms FBA in quantitative phenotype predictions [21] | Microbial growth prediction; Gene knockout phenotype prediction [21] |

| DBI-LSTM-2AM-PSO | 95.53 [22] | Fitness value: 0.47 [22] | F1 score: 91.41%; MSE: 0.049 [22] | Renewable energy prediction; Distributed power generation systems [22] |

| Evolutionary Algorithm (MoGA-TA) | Success rate significantly improved over NSGA-II [23] | Maintains population diversity; Prevents premature convergence [23] | Dominating hypervolume; Geometric mean; Internal similarity [23] | Drug molecule optimization; Multi-property molecular design [23] |

| Topology-Informed (TIObjFind) | Good match with experimental data [8] | Identifies pathway-specific weighting factors [8] | Reduces prediction errors; Captures stage-specific metabolic objectives [8] | Metabolic network analysis; Cellular response prediction under changing conditions [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Neural-Mechanistic Hybrid Approach (AMN)

The Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN) framework embeds Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) within artificial neural networks to overcome the gradient backpropagation limitation of traditional simplex solvers [21]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Network Architecture: A trainable neural layer followed by a mechanistic layer (Wt-solver, LP-solver, or QP-solver) [21]

- Training Process: The neural layer computes initial flux values (V0) from medium uptake flux bounds (Vin) or medium compositions (Cmed)

- Constraint Integration: Custom loss functions surrogate FBA constraints while enabling gradient computation

- Validation: Comparison of predicted fluxes (Vout) with reference fluxes from FBA simulations or experimental data

This approach demonstrates systematic outperformance over constraint-based models, requiring training set sizes orders of magnitude smaller than classical machine learning methods [21]. The hybrid architecture successfully captures metabolic enzyme regulation and predicts gene knockout effects on phenotype.

DBI-LSTM-2AM-PSO for Renewable Energy Systems

The DBI-LSTM-2AM-PSO model combines deep learning with improved particle swarm optimization for distributed power generation systems [22]:

- Prediction Component: Dense Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory with Attention Mechanism (DBI-LSTM-AM) performs time-series forecasting of energy demand

- Optimization Component: Adaptive Linear Decreasing Inertia Weight Particle Swarm Optimization with Mutation Strategy (ALD-MPSO) simultaneously optimizes economic efficiency, environmental benefits, and system reliability

- Integration: The fused model achieves 95.53% prediction accuracy with 25.7s training time and low computational resource consumption (10.55% CPU usage) [22]

Experimental validation demonstrates superior performance over benchmark algorithms across multiple metrics including mean squared error (0.049) and F1 score (91.41%) [22].

MoGA-TA for Molecular Optimization

The Multi-objective Genetic Algorithm with Tanimoto similarity and Adaptive acceptance probability (MoGA-TA) addresses drug molecule optimization through:

- Similarity Calculation: Tanimoto similarity-based crowding distance captures molecular structural differences [23]

- Population Update: Dynamic acceptance probability strategy balances exploration and exploitation during evolution [23]

- Optimization Process: Decoupled crossover and mutation strategy in chemical space continues until predefined stopping conditions

- Evaluation Metrics: Success rate, dominating hypervolume, geometric mean, and internal similarity assess algorithm performance [23]

Benchmark evaluation across six molecular optimization tasks demonstrates significant improvements in efficiency and success rate compared to NSGA-II and GB-EPI [23].

Visualization of Methodological Relationships and Workflows

Figure 1: Methodology Taxonomy for Multi-Objective Optimization. This diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between broad optimization categories and their specific implementations discussed in this review, highlighting the diverse methodological approaches available for flux prediction and biological system optimization.

Figure 2: TIObjFind Framework Workflow. This workflow diagram outlines the three key steps in the Topology-Informed Objective Find methodology, demonstrating how experimental data and network topology are integrated to identify critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance for metabolic objective functions [8] [10].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Objective Optimization Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function and Application | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constraint-Based Modeling | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [8] [21] | Predicts metabolic flux distributions at steady state | Requires stoichiometric matrix, flux bounds, objective function |

| Metabolic Pathway Analysis | TIObjFind [8] | Identifies objective functions aligning with experimental data | MATLAB implementation with maxflow package [10] |

| Deep Learning Architectures | DBI-LSTM-AM [22] | Time-series forecasting of energy demand | Combines Bi-LSTM, Dense layers, and Attention Mechanism |

| Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic | Artificial Metabolic Networks (AMN) [21] | Enhances constraint-based model predictions | Embeds FBA within neural networks; enables gradient backpropagation |

| Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms | NSGA-II [23], MoGA-TA [23] | Optimizes multiple molecular properties simultaneously | Uses non-dominated sorting and crowding distance |

| Molecular Similarity Metrics | Tanimoto Coefficient [23] | Quantifies structural similarity between molecules | Based on fingerprint comparisons; range 0-1 |

| Optimization Algorithms | ALD-MPSO [22] | Adaptive particle swarm optimization for multiple objectives | Mutation strategy prevents premature convergence |

| Data Sources | KEGG [8], EcoCyc [8], ChEMBL [23] | Provides metabolic pathways and molecular data | Foundation for stoichiometric models and benchmarking |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that the selection of appropriate multi-objective optimization strategies must be guided by specific research contexts and constraints. Neural-mechanistic hybrid models offer superior performance for quantitative phenotype predictions when sufficient training data is available, effectively bridging the gap between mechanistic understanding and predictive power [21]. Topology-informed approaches like TIObjFind provide critical insights into pathway contributions and adaptive cellular responses, making them particularly valuable for metabolic engineering applications where elucidation of biological mechanisms is prioritized [8] [10]. Evolutionary algorithms excel in molecular optimization tasks where multiple physicochemical properties must be balanced simultaneously, with enhanced techniques like MoGA-TA addressing the critical challenge of maintaining diversity in chemical space exploration [23] [24].

The continuing evolution of multi-objective optimization methodologies points toward increased integration of mechanistic constraints with machine learning approaches, offering researchers an expanding toolkit for addressing the complex challenges in flux prediction and drug development. As these hybrid frameworks mature, they promise to significantly accelerate the discovery and optimization cycle while providing deeper insights into the fundamental principles governing biological systems.

Flux analysis is a critical computational technique for quantifying the flow of molecules, energy, or information through biological, chemical, and engineering systems. In metabolic engineering, it describes the rates at which nutrients are converted into biomass and products through biochemical reactions. In engineering systems, it can represent heat or particle flow. Accurately predicting these fluxes is fundamental to optimizing bioprocesses, understanding cellular physiology, and designing efficient industrial systems. Traditional methods, particularly in metabolic engineering, have relied heavily on constraint-based modeling approaches like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which predict steady-state flux distributions by assuming the cell optimizes an objective, such as biomass maximization [8] [25] [21].

However, these mechanistic models face challenges, including an inherent inability to fully capture the complex regulatory mechanisms of cells and a frequent reliance on difficult-to-measure input parameters, such as nutrient uptake rates [21]. The emergence of machine learning (ML) offers powerful new tools to overcome these limitations. ML models can learn complex, non-linear relationships directly from experimental data, leading to more accurate and generalizable predictions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two prominent ML frameworks in flux analysis: the versatile Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and the specialized ML-Flux, detailing their performance, experimental protocols, and applications to help researchers select the appropriate tool for their specific objectives.

Performance Comparison of ANN and ML-Flux Frameworks

The performance of ANN and ML-Flux varies significantly depending on the application domain, data availability, and specific prediction task. The following tables summarize their key characteristics and quantitative performance metrics based on recent studies.

Table 1: Overall Framework Characteristics and Application Scope

| Feature | ANN Framework | ML-Flux Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application Domain | Diverse: Membrane desalination, nuclear reactor safety, metabolic modeling [26] [27] [28] | Specialized: Central Carbon Metabolism in biological systems [29] |

| Core Methodology | Neural networks learning input-output relationships from data; often used in hybrid mechanistic-ML models [26] [21] | Pre-trained neural networks mapping isotope labeling patterns directly to metabolic fluxes [29] |

| Key Input Features | System-specific parameters (e.g., temperatures, flow rates, control rod positions, medium composition) [26] [28] [21] | Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) from 13C-tracer experiments [29] |

| Typical Output | System-specific fluxes (e.g., permeate flux, critical heat flux), growth rates, or operational parameters [26] [30] [21] | Net and exchange fluxes in metabolic networks [29] |

| Major Advantage | Flexibility; can be integrated with mechanistic models for improved generalization with small datasets [21] | High speed and accuracy for 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA); can impute missing labeling data [29] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Experimental Studies

| Framework & Model | Application / Task | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANN (ANFIS-C4 Hybrid) | Flux prediction in water desalination (DCMD) | Training: 100% accuracy, RMSE=0.0522Testing: 99.73% accuracy, RMSE=0.7121 | [26] |

| ANN (Classification Model) | Critical Heat Flux (CHF) prediction in a CANDU reactor | RMSE: ~2.5%; Reduced overfitting compared to regression ANN | [27] |

| ANN (Hybrid Lookup Table) | CHF prediction in vertical tubes | rRMSE: 9.3%, outperforming standalone ML models and lookup tables | [30] |

| Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic (AMN) | Growth rate prediction for E. coli and P. putida | Outperformed standard FBA; required orders of magnitude less training data than pure ML | [21] |

| ML-Flux | Flux prediction in Central Carbon Metabolism | >90% of predictions more accurate than conventional MFA software; computation is consistently faster | [29] |

Framework Architecture and Workflow

The ANN Framework: Versatility through Hybrid Modeling

Artificial Neural Networks are a class of ML algorithms that learn complex relationships through interconnected layers of nodes. In flux analysis, ANNs are often not used in isolation but as part of a hybrid mechanistic-ML architecture. This combines the data-driven learning power of ML with the established scientific principles of mechanistic models, improving predictive power even with small training datasets [21].

A prominent example is the Artificial Metabolic Network (AMN), which embeds a mechanistic FBA model within a neural network. The neural network layer learns to predict optimal uptake flux constraints from environmental conditions, which are then fed into the mechanistic layer to compute the steady-state metabolic phenotype [21]. This hybrid approach overcomes a key FBA limitation—the inaccurate estimation of uptake fluxes from extracellular concentrations.

Diagram: Workflow of a Hybrid Neural-Mechanistic Model for Metabolic Flux Prediction

The ML-Flux Framework: Specialized Speed for 13C-MFA

ML-Flux is a specialized framework designed to accelerate and improve the accuracy of 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), a gold-standard method for determining intracellular metabolic fluxes. Unlike traditional 13C-MFA, which uses iterative, computationally expensive optimization to fit fluxes to experimental isotope labeling data, ML-Flux uses pre-trained neural networks to directly map Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) to metabolic fluxes [29].

The framework employs two key neural network models: a Partial Convolutional Neural Network (PCNN) that imputes missing isotope labeling patterns in experimental data, and an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) that takes the complete set of MIDs as input and outputs the predicted metabolic fluxes. This creates a streamlined, highly efficient pipeline that bypasses the need for repeated model simulations and optimizations.

Diagram: ML-Flux Workflow for Metabolic Flux Quantitation

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Developing an ANN for Flux Prediction

The development of a robust ANN model for flux prediction involves a standardized sequence of steps, from data collection to model deployment.

- Data Collection and Curation: Assemble a comprehensive dataset encompassing a wide range of input conditions and corresponding output fluxes. For a desalination membrane flux prediction model, inputs may include feed temperature, coolant flow rate, and salinity [26]. For a metabolic model, inputs could be environmental conditions like medium composition [21]. The dataset must be cleaned and normalized.

- Dataset Partitioning: Randomly split the dataset into three subsets:

- Training Set (~70%): Used to adjust the weights of the neural network.

- Validation Set (~15%): Used to tune hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of layers) and prevent overfitting during training.

- Test Set (~15%): Used only once for the final evaluation of the model's generalization performance.

- Model Architecture Selection and Training: Choose an appropriate network architecture (e.g., feedforward, convolutional). Train the model using an optimization algorithm (e.g., Adam, SGD) to minimize a loss function, such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) between predictions and actual flux values. For hybrid models, the loss function also incorporates mechanistic constraints [21].

- Model Validation and Benchmarking: Rigorously evaluate the trained model on the test set using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and prediction accuracy. Compare its performance against existing empirical correlations, mechanistic models, or other ML algorithms to establish its superiority [26] [30].