CRISPR vs. TALEN vs. ZFN: A Comprehensive Guide to Choosing Your Genome Editing Tool

This article provides a detailed comparison of the three major genome-editing platforms—Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR-Cas system.

CRISPR vs. TALEN vs. ZFN: A Comprehensive Guide to Choosing Your Genome Editing Tool

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of the three major genome-editing platforms—Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR-Cas system. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational mechanisms, methodological applications, and key challenges of each technology. Drawing on the latest research and direct comparative studies, the content delivers actionable insights for troubleshooting, optimizing editing efficiency, and validating outcomes. The review also covers emerging trends, such as base and prime editing, and discusses the clinical implications and safety considerations vital for therapeutic development.

The Evolution of Programmable Nucleases: From ZFNs to CRISPR-Cas

Programmable nucleases have revolutionized genetic engineering by acting as precise molecular scissors. Their core function is to create DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) at predetermined genomic locations, harnessing the cell's own repair machinery to achieve targeted genetic modifications. [1] [2] This guide provides a detailed comparison of the three primary nuclease technologies—Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the CRISPR/Cas9 system—focusing on their mechanisms, efficiencies, and practical applications in research and therapy.

The Universal Trigger: Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

The power of all programmable nucleases lies not just in the cut they make, but in the cellular repair processes they activate. Once a double-strand break (DSB) is introduced, the cell attempts to repair this potentially genotoxic lesion primarily through two pathways: the error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and the high-fidelity Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). [1] [2] [3]

- NHEJ directly ligates the broken DNA ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). When these indels occur within a gene's coding sequence, they can disrupt the reading frame, leading to gene knockout. [4] [2] [3]

- HDR requires a homologous DNA template to accurately repair the break. By providing an engineered donor DNA template, researchers can exploit this pathway to introduce specific sequence changes, such as point mutations or gene insertions. [4] [5]

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision point a cell faces after a nuclease-induced DSB and the potential outcomes for genome engineering.

Molecular Architectures of Programmable Nucleases

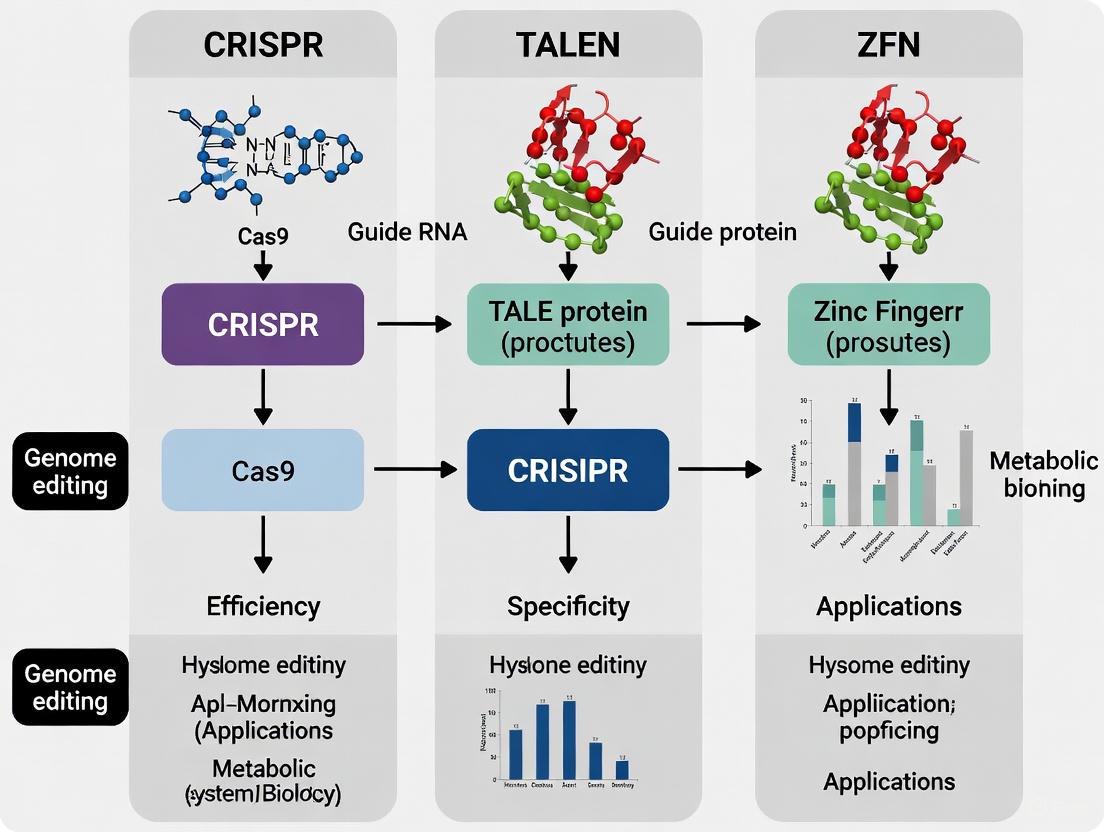

While ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9 all achieve DSBs, their molecular compositions and DNA recognition mechanisms are fundamentally different. The table below summarizes the core architectural components of each system.

Table 1: Architectural Comparison of Programmable Nuclease Systems

| Feature | Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | TALENs | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Domain | Engineered zinc-finger proteins (Cys2-His2 motif) [2] [6] | Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) [4] [2] | CRISPR RNA (crRNA) guide sequence [1] [3] |

| Recognition Code | 1 zinc finger domain ≈ 3 base pairs [2] [6] | 1 TALE repeat ≈ 1 base pair (e.g., NI=A, HD=C, NG=T, NN=G) [4] [2] | RNA-DNA base pairing (Watson-Crick) [1] [3] |

| Cleavage Domain | FokI nuclease domain [5] [6] | FokI nuclease domain [4] [7] | Cas9 protein (HNH & RuvC domains) [1] |

| Cleavage Mechanism | Dimeric: Requires a pair of ZFNs binding opposite strands for FokI dimerization. [5] [6] | Dimeric: Requires a pair of TALENs binding opposite strands for FokI dimerization. [4] [3] | Monomeric: A single Cas9 protein complexed with a guide RNA creates the DSB. [1] [3] |

| Target Site Structure | Two "half-sites" separated by a 5-7 bp spacer. [5] [6] | Two "half-sites" separated by a spacer. [4] [3] | Target sequence adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM, e.g., NGG for SpCas9). [1] |

The following diagram visualizes how these architectural differences translate into the process of finding and cutting a DNA target.

Performance and Practical Comparison

Beyond molecular architecture, practical considerations such as efficiency, specificity, ease of use, and application suitability are critical for selecting the right tool.

Table 2: Performance and Practical Application Comparison

| Aspect | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Range | Limited by G-rich sequence preference; context-dependent effects complicate design. [2] [6] | Virtually unlimited; simple code links protein repeats to DNA bases. [4] [2] | Limited only by the presence of a PAM sequence (e.g., NGG). [1] |

| Editing Efficiency | Variable; highly dependent on the success of zinc-finger array design. [2] [6] | High; studies show success rates comparable to ZFNs and CRISPR. [4] | Very high; often the most efficient system in direct comparisons. [3] [8] |

| Off-Target Effects | Moderate to high; dependent on ZF array specificity. One study reported 287 off-target sites for an HPV-targeted ZFN. [8] | Low to moderate; the dimeric requirement acts as a natural "fail-safe". [3] [8] | Can be higher due to single-guide RNA dependency; tolerates mismatches, especially in PAM-distal region. [1] [8] |

| Ease of Design & Use | Technically challenging; requires expertise to account for context-dependence between fingers. [2] [6] | Cloning is laborious due to highly repetitive sequences, but design is straightforward. [4] [2] | Very simple; requires only the synthesis of a ~20nt guide RNA sequence. [3] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Low; difficult to express and deploy multiple ZFN pairs simultaneously. | Low; similar challenges to ZFNs due to large, repetitive constructs. | High; multiple guide RNAs can be expressed to target several sites at once. [3] |

| Delivery Consideration | cDNA size ~1 kb, easier for viral delivery. [3] | cDNA size ~3 kb, pushing the limits of standard viral vectors (e.g., AAV). [3] | Cas9 cDNA ~4.2 kb, large for viral delivery; often requires split systems or alternative Cas proteins. |

Supporting Experimental Data: A Direct Comparison

A rigorous 2021 study using the GUIDE-seq method to profile off-target activity in a human papillomavirus (HPV) gene therapy context provides a direct, quantitative comparison. [8]

- Efficiency and Specificity: When targeting the HPV E6 gene, SpCas9 was not only highly efficient but also exhibited zero detectable off-target events. In contrast, TALENs targeting the same region produced 7 off-target sites. [8]

- ZFN Performance: The same study found that ZFNs could generate a strikingly high number of off-targets (ranging from 287 to 1,856), with specificity potentially inversely correlated with the count of middle "G" bases in the target sequence. [8]

These findings underscore that while all tools are effective, CRISPR/Cas9 can offer a superior combination of efficiency and specificity in head-to-head tests.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and deepen the understanding of the data presented, this section outlines key methodologies used to generate the comparative findings.

GUIDE-seq for Genome-Wide Off-Target Detection

The GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by sequencing) method is a powerful technique for profiling off-target cleavage by nucleases. [8]

- Oligonucleotide Tag Transfection: Cells co-transfected with the nuclease (ZFN, TALEN, or CRISPR/Cas9) and a blunt-ended, double-stranded oligonucleotide "tag".

- Tag Integration: During the repair of nuclease-induced DSBs via NHEJ, the tag is integrated into the break sites.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Genomic DNA is sheared and adaptor-ligated. PCR amplification, using one primer specific to the integrated tag and another to the genomic adaptor, enriches for tag-integrated fragments, which are then sequenced.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequencing reads are mapped to the reference genome to identify all tag integration sites, which correspond to both on-target and off-target nuclease cleavage events.

UMI-DSBseq for Kinetic Analysis of DSB Repair

A 2024 study developed UMI-DSBseq to precisely quantify DSB intermediates and repair products over time. [9]

- Protoplast Transfection & Sampling: Tomato protoplasts are transfected with preassembled Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for synchronized DSB induction. Samples are collected along a time-course (e.g., 0-72 hours).

- End-Repair and Adaptor Ligation: Genomic DNA is extracted. A restriction enzyme creates a reference DSB at a site flanking the target. DNA ends, including both the reference breaks and nuclease-induced DSBs, are repaired and ligated to adaptors containing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs).

- Library Sequencing and Analysis: Target sites are amplified and sequenced. UMIs allow for accurate counting of original molecules, distinguishing between intact, precisely repaired molecules, unrepaired DSBs, and error-prone repair products (indels). This enables modeling of DSB induction and repair kinetics.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions, as derived from the experimental protocols and technologies discussed.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Nuclease-Based Genome Editing

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Preassembled RNP | Complex of purified Cas9 protein and synthetic guide RNA. Allows for transient, rapid nuclease activity without genomic integration. [9] | Direct delivery into protoplasts or cells for synchronized DSB induction in kinetic studies. [9] |

| Obligate Heterodimer FokI Variants | Engineered FokI nuclease domains with mutations that force pairing only between two different monomers, reducing homodimer off-target cleavage. [6] | Used in ZFN and TALEN architectures to improve specificity. [5] [6] |

| Chemically Modified gRNA | Synthetic guide RNAs with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl analogs) to improve stability and reduce immune responses in cells. [1] | Enhances editing efficiency and reduces toxicity in therapeutic applications. |

| GUIDE-seq Oligo Tag | A short, double-stranded DNA oligonucleotide that is integrated into DSB sites during repair to mark them for genome-wide identification. [8] | Unbiased detection of off-target cleavage sites for ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9. [8] |

| UMI-DSBseq Adaptors | Sequencing adaptors containing Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) for ligation to DSB ends, enabling single-molecule tracking of repair outcomes. [9] | Precise quantification of DSB intermediates and repair dynamics over time. [9] |

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) represent the pioneering technology that first enabled true precision in genome engineering. As the initial member of the programmable nuclease triad that also includes TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9, ZFNs demonstrated for the first time that researchers could make targeted, specific modifications to complex genomes [10]. This groundbreaking technology is built upon a protein-driven design framework, where engineered zinc finger proteins provide sequence specificity fused to a nuclease domain that executes DNA cleavage [11]. The development of ZFNs opened new frontiers in biological research and therapeutic development by moving beyond random mutagenesis to targeted gene editing. Despite the subsequent emergence of newer technologies, ZFNs remain relevant due to their high specificity and continued refinement, including applications in clinical trials and advanced therapeutic development [11] [12]. This article explores the protein-driven architecture of ZFNs and provides a objective comparison with TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9 based on experimental data and performance metrics.

Molecular Architecture and Mechanism

The ZFN system operates through an elegant protein-DNA recognition mechanism. Each ZFN is a chimeric protein composed of two functional domains: a DNA-binding domain derived from Cys2-His2 (C2H2) zinc finger proteins and a cleavage domain from the FokI restriction enzyme [11] [2]. The C2H2 zinc finger domain is one of the most common DNA-binding motifs in eukaryotes, folding into a compact ββα structure stabilized by zinc ion coordination [11]. Each individual zinc finger domain recognizes a 3-4 base pair DNA sequence, with multiple fingers assembled in tandem to create extended specificity for typically 9-18 base pairs [2] [10].

The FokI cleavage domain must dimerize to become active, necessitating the design of ZFN pairs that bind to opposite DNA strands with correct orientation and spacing [11]. This dimerization requirement provides a natural check on specificity, as off-target cleavage is less likely to occur without simultaneous binding of both ZFNs at adjacent sites. When successfully bound and dimerized, the FokI domains create a double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA with 5' overhangs [10]. The cellular repair of these breaks through either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) enables the desired genetic modifications, from gene knockouts to precise knockins [2].

Figure 1: ZFN Mechanism of Action. ZFNs function as pairs with DNA-binding domains and FokI cleavage domains that must dimerize to create double-strand breaks, repaired by cellular mechanisms.

Engineering and Design Methodologies

The engineering of functional ZFNs has evolved through several methodological approaches, each with distinct advantages:

Modular Assembly: This approach utilizes pre-characterized zinc finger modules that recognize specific 3-base pair triplets [11]. Researchers can assemble these predefined modules in tandem to target desired DNA sequences. The Barbas and ToolGen domains represent the two most commonly used sets of modular assembly fingers, covering GNN, most ANN, many CNN, and some TNN triplets (where N represents any nucleotide) [11]. The primary advantage of modular assembly is the ability to rapidly construct ZFNs without additional selection steps, though context-dependent effects between neighboring fingers can influence specificity [11].

Oligomerized Pool Engineering (OPEN): Developed to address context-dependency limitations, OPEN employs a combinatorial selection-based strategy using pre-selected zinc finger pools from an archive [11]. Appropriate finger pools are recombined to create libraries of multi-finger arrays, which are then screened using bacterial two-hybrid (B2H) systems to identify functional binders [11]. OPEN achieves approximately 70-80% success rate for obtaining functional ZF arrays and is publicly available through the Zinc Finger Consortium Database [11].

Context-Dependent Assembly: This hybrid approach utilizes zinc finger modules pre-selected for context dependency, combining advantages of both modular assembly and selection-based methods [2]. These methods acknowledge that zinc finger specificity can be influenced by positional effects and neighboring finger sequences, leading to more reliable DNA-binding proteins.

Comparative Analysis: ZFNs vs. TALENs vs. CRISPR-Cas9

Mechanism and Design Comparison

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Genome Editing Technologies

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Molecule | Engineered zinc finger proteins [13] | Transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) [13] | Guide RNA (gRNA) [13] |

| Recognition Mechanism | Protein-DNA interaction [13] | Protein-DNA interaction [13] | RNA-DNA complementarity [13] |

| Recognition Length | 9-18 bp per ZFN (18-36 bp for pair) [13] | 30-40 bp per TALEN pair [13] | 20 bp gRNA + PAM sequence [13] |

| Cleavage Domain | FokI nuclease (requires dimerization) [11] [2] | FokI nuclease (requires dimerization) [2] | Cas9 nuclease (single protein) [13] |

| Target Constraints | Prefers G-rich sequences; limited target sites [10] | Requires T at 5' position; more flexible than ZFNs [2] | Requires PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9) [13] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Difficult | Moderate | Easy [13] |

Experimental Performance Metrics

Recent comparative studies have provided quantitative assessments of nuclease performance, particularly regarding specificity and efficiency:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison in HPV-Targeted Gene Therapy [8]

| Parameter | ZFNs | TALENs | SpCas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-target Count (URR target) | 287 | 1 | 0 |

| Off-target Count (E6 target) | Not tested | 7 | 0 |

| Off-target Count (E7 target) | Not tested | 36 | 4 |

| Specificity Trend | Massive off-target variation; correlates with "G" count | Design trade-offs: higher efficiency increases off-targets | Highest specificity overall |

| Efficiency | Variable | High with optimized designs | Highest |

A comprehensive 2021 study using GUIDE-seq analysis for human papillomavirus (HPV) targeted therapy revealed that ZFNs with similar targets could generate distinct massive off-targets (287-1,856), with specificity reversely correlated with counts of middle "G" in zinc finger proteins [8]. This same study found SpCas9 demonstrated superior efficiency and specificity compared to both ZFNs and TALENs across multiple genomic targets [8].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Table 3: Practical Application Considerations for Researchers

| Aspect | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Complexity | High [14] [10] | Moderate [14] | Low [14] |

| Construction Time | Months for optimized designs [10] | Weeks [14] | Days [14] |

| Cost Efficiency | Low (protein engineering intensive) [14] | Moderate | High [14] |

| Technical Accessibility | Requires specialized expertise [10] | Standard molecular biology | Accessible to most labs |

| Delivery Considerations | Compatible with viral vectors [12] | Large size challenges delivery | Cas9 size may challenge delivery |

| Therapeutic Development | Clinical trials ongoing (e.g., HIV) [11] | Preclinical development | Extensive clinical development |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ZFN Validation Workflow

The development of functional ZFNs requires rigorous validation through a structured experimental pipeline:

Figure 2: ZFN Validation Workflow. Key steps in developing and validating functional ZFNs, from target identification to specificity assessment.

Step 1: Target Site Identification

- Identify target sequences of the form (NNC)₃...(GNN)₃ separated by 4-6 bp within the gene of interest [15]

- Screen for sequences with minimal off-target potential across the genome

- Prioritize targets with G-rich sequences for optimal zinc finger binding [10]

Step 2: Zinc Finger Protein Design

- Select appropriate zinc finger modules using modular assembly, OPEN, or context-dependent methods [11]

- For modular assembly, utilize pre-defined zinc finger archives (Barbas or ToolGen sets) [11]

- Design ZFN pairs with appropriate spacing (4-6 bp) for FokI dimerization [11] [15]

Step 3: ZFN Construction

- Clone zinc finger arrays into expression vectors containing FokI cleavage domain

- Utilize systems such as CompoZr for commercial ZFN sources [2]

- Verify protein expression through Western blot or in vitro transcription/translation [15]

Step 4: In Vitro Cleavage Assay (IVTT)

- Express ZFNs using rabbit reticulocyte lysate TnT Quick-Coupled Transcription-Translation system [15]

- Incubate with plasmid substrate containing target site

- Analyze cleavage products via gel electrophoresis for sequence-specific cleavage activity [15]

- Modify IVTT assay for rapid screening of multiple ZFN constructs [15]

Step 5: Cell-Based Validation

- Deliver ZFNs to target cells via transfection or viral transduction

- Assess mutation rates using SURVEYOR or T7E1 mismatch assays

- Quantify indel formation through sequencing analysis

- Evaluate HDR efficiency using donor templates

Step 6: Off-Target Assessment

- Identify potential off-target sites through in silico prediction based on sequence similarity [10]

- Utilize GUIDE-seq or similar genome-wide methods for unbiased off-target detection [8]

- Assess cytotoxicity and cellular responses to ZFN treatment

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ZFN Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| ZFN Engineering Systems | Barbas modular assembly, OPEN system, CompoZr | Design and construction of zinc finger arrays [11] [2] |

| Expression Systems | TnT Quick-Coupled Transcription/Translation | In vitro ZFN synthesis and testing [15] |

| Cleavage Assay Reagents | Custom target plasmids, gel electrophoresis reagents | Validation of sequence-specific cleavage activity [15] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Adenoviral, lentiviral vectors, transfection reagents | Introduction of ZFNs into target cells [10] |

| Analysis Tools | SURVEYOR assay, T7E1 mismatch detection, sequencing | Detection and quantification of editing events |

| Off-Target Assessment | GUIDE-seq, BLISS, Digenome-seq | Genome-wide identification of off-target effects [8] |

Applications and Therapeutic Developments

ZFN technology has demonstrated significant utility across diverse research and therapeutic areas:

Biomedical Research Applications

Disease Modeling: ZFNs have been used to correct disease-causing mutations associated with sickle cell disease, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, hemophilia B, and Parkinson's disease in patient-derived cells [11]. The combination of ZFNs with induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology enables the genetic correction of point mutations in patient-specific cell lines [11].

Gene Function Studies: ZFNs facilitate targeted gene knockout studies in various cell types and model organisms, providing conclusive information about gene function through complete and permanent gene disruption [2].

Biotechnology Applications: Beyond nucleases, zinc finger proteins have been fused to various effector domains including transcriptional activators, repressors, recombinases, and transposases for diverse genome engineering applications [2].

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Development

ZFN technology has progressed to clinical trials, demonstrating its therapeutic potential:

HIV Treatment: Clinical trials (NCT00842634 and NCT01044654) have investigated ZFN-mediated disruption of the CCR5 gene in T-cells to create HIV-resistant immune cells [11].

Sickle Cell Disease: ZFN-mediated genome editing of the BCL11A erythroid-specific enhancer in hematopoietic stem progenitor cells represents a potential therapeutic approach [12].

Allogeneic Cell Therapies: ZFNs are being utilized to disrupt genes in allogeneic cell therapies for autoimmune diseases and cancer [12].

Neurological Disorders: Zinc finger transcriptional regulators (ZF-TRs), including repressors and activators, are being evaluated as potential treatments for chronic neuropathic pain, prion disease, and Huntington's disease [12].

The development of ZFN technology established the foundation for programmable genome editing and continues to evolve through ongoing innovations. While CRISPR-Cas9 currently dominates the research landscape due to its ease of use and accessibility, ZFNs maintain distinct advantages in specific applications, particularly where their compact size benefits delivery constraints or where high specificity is paramount [12]. Recent advances include the development of zinc finger base editors that enable precise nucleotide changes without creating double-strand breaks, potentially reducing off-target effects [12].

The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that each genome editing platform offers distinct advantages and limitations. ZFNs provide high specificity and the benefit of being based on human-derived proteins, potentially offering safety advantages for therapeutic applications [12]. However, their technical complexity and design challenges have limited widespread adoption compared to CRISPR-based systems. TALENs strike a balance between specificity and design feasibility, while CRISPR-Cas9 offers unparalleled ease of use and multiplexing capabilities, though with ongoing concerns about off-target effects that continue to be addressed through engineering improvements [8] [13].

For researchers selecting genome editing technologies, the decision should be guided by specific application requirements rather than assuming the superiority of any single platform. ZFNs remain a valuable option particularly for therapeutic applications where their clinical experience, compact size, and human protein origin may provide distinct advantages. As the field of genome editing continues to advance, the pioneering ZFN technology continues to inform and inspire new developments in precision genetic medicine.

The advent of programmable nucleases has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling precise modifications across diverse organisms. Among these technologies, Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) have emerged as a powerful platform distinguished by their exceptional specificity and unique molecular architecture. While CRISPR-Cas9 systems have gained widespread popularity due to design simplicity, TALENs offer distinct advantages in applications where targeting precision is paramount, particularly in therapeutic development [16]. This guide objectively compares TALEN performance against alternative genome editing tools, with focused examination of the experimental approaches used to quantify and enhance their specificity.

TALENs represent a fusion between bacterial transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) from Xanthomonas bacteria and the FokI nuclease domain [7]. Their DNA recognition mechanism employs a simple, predictable code that translates specific amino acid sequences to nucleotide binding preferences. This review comprehensively analyzes how this "simpler code" translates to practical advantages in research and clinical applications, supported by direct experimental comparisons and methodological details.

Molecular Architecture and Comparative Mechanisms

TALEN Structure and DNA Recognition Code

The TALEN system functions as a dimer, with each monomer consisting of a central DNA-binding domain derived from TALEs coupled to a FokI nuclease domain [16]. The DNA-binding domain comprises 12-28 highly conserved 33-35 amino acid repeats, each recognizing a single DNA nucleotide through two critical residues at positions 12 and 13, known as Repeat Variable Diresidues (RVDs) [7]. The established RVD-DNA recognition code primarily utilizes four RVD modules: NI for adenine (A), HD for cytosine (C), NN for guanine (G), and NG for thymine (T) [17]. This modular one-repeat-to-one-base-pair recognition system provides TALENs with unparalleled targeting flexibility, enabling theoretical targeting of any DNA sequence [16].

The FokI nuclease domain requires dimerization to become active, meaning two TALEN monomers must bind opposite DNA strands at precisely spaced intervals (typically 14-20 base pairs between binding sites) to enable DNA cleavage [18]. This dimerization requirement significantly enhances targeting specificity by effectively doubling the recognition length to approximately 30-36 base pairs, a sequence statistically unlikely to appear randomly in genomes [16].

Comparative Mechanisms of Major Genome Editing Platforms

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Genome Editing Platforms

| Feature | TALEN | CRISPR/Cas9 | ZFN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition Type | DNA-protein interaction [16] | RNA-DNA complementarity [16] | DNA-protein interaction [17] |

| DNA Binding Domain | TALE repeats (1 repeat/1 bp) [7] | Guide RNA (∼20 nt) [16] | Zinc fingers (3-6 fingers/9-18 bp) [17] |

| Nuclease | FokI (requires dimerization) [16] | Cas9 (functions as monomer) [16] | FokI (requires dimerization) [17] |

| Target Length | 30-36 bp (combined dimer recognition) [16] | 20 bp guide + PAM [16] | 18-36 bp (combined dimer recognition) [17] |

| Specific Constraint | 5' T requirement [19] | PAM sequence requirement (e.g., NGG for SpCas9) [16] | Context-dependent binding effects [17] |

The molecular mechanism differences create distinct practical implications. CRISPR-Cas9 systems rely on RNA-DNA hybridization for targeting, with Cas9 nuclease activity triggered by successful matching between guide RNA and target DNA adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence [16]. This mechanism allows easier retargeting but increases mismatch tolerance potential. In contrast, TALENs and ZFNs employ protein-DNA interactions, with ZFNs utilizing C2H2 zinc finger arrays where each finger typically recognizes 3-base pair sequences [17]. The TALEN approach represents an intermediate in design simplicity between the highly modular CRISPR system and the more complex ZFN platform.

Diagram 1: Molecular recognition mechanisms of major genome editing platforms. TALENs and ZFNs utilize protein-DNA interactions with FokI dimerization requirements, while CRISPR employs RNA-DNA hybridization with PAM sequence constraints. The extended recognition length of TALENs contributes to their high specificity profile.

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Performance

Specificity and Off-Target Profiles

Comprehensive studies directly comparing genome editing technologies have revealed distinct performance characteristics. TALENs consistently demonstrate superior specificity metrics with minimal off-target activity, a critical consideration for therapeutic applications [16].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Genome Editing Tools

| Performance Metric | TALEN | CRISPR/Cas9 | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Off-Target Rate | Low [16] | High (≥50% in some studies) [16] | Human cell lines [16] |

| Typical Indel Formation | ∼33% [18] | Up to >70% [18] | Chromosomal targets [18] |

| Mismatch Tolerance | Few mismatches tolerated [16] | Moderate, up to 5 mismatches reported [18] | In vitro specificity profiling [19] |

| Genomic Off-Target Sites Identified | 16 sites across 76 predicted in human cells [19] | Numerous off-target sites with high mutation rates [16] | Genome-wide studies [16] [19] |

| Mitochondrial Genome Editing | Possible (mito-TALEN) [16] | Complicated due to gRNA import issues [16] | Mitochondrial DNA manipulation [16] |

Experimental evidence from specificity profiling studies demonstrates that TALENs maintain high on-target activity while minimizing off-target effects. In one comprehensive analysis, 30 unique TALENs were profiled against 10¹² potential off-target sequences, revealing that TALENs cleave specifically at intended sites with minimal activity against mismatched sequences [19]. The same study identified only 16 bona fide off-target sites in the human genome across all tested TALENs, with most showing significantly reduced cleavage efficiency compared to on-target sites.

Targeting Range and Practical Efficiency

While TALENs demonstrate superior specificity, each platform exhibits distinct advantages in practical applications. CRISPR systems offer unparalleled ease of design and multiplexing capabilities, enabling simultaneous targeting of multiple genomic loci [20]. TALENs provide broader targeting freedom without PAM sequence constraints but require more complex protein engineering for each new target [16].

DNA methylation sensitivity represents an important practical consideration. TALEN activity can be inhibited by cytosine methylation, particularly at CpG dinucleotides, which requires careful target selection or use of specialized RVDs [18]. CRISPR systems do not share this limitation, providing more consistent activity across differentially methylated genomic regions.

Experimental Approaches for Enhancing TALEN Specificity

Non-Conventional RVDs for Specificity Optimization

Research efforts have focused on expanding the TALEN recognition code beyond the four conventional RVDs to enhance specificity. High-throughput screening of non-conventional RVDs (ncRVDs) has identified novel combinations with improved discriminatory power [21].

Table 3: Experimental Reagents for TALEN Specificity Enhancement

| Research Reagent | Composition/Function | Specificity Application |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Conventional RVDs | Alternative amino acids at positions 12/13 | Enhance nucleotide discrimination, particularly at mismatch positions [21] |

| TALEN-Q3 Variant | Modified TALEN architecture with reduced non-specific DNA binding | 10-fold lower off-target activity in human cells [19] |

| Obligate Heterodimeric FokI | EL/KK FokI variants requiring heterodimerization | Prevents homodimer activity, reduces off-target cleavage [19] |

| Specificity Profiling Library | 10¹² potential off-target DNA sequences | Comprehensive specificity assessment [19] |

The experimental approach for identifying ncRVDs involved creating randomized RVD libraries using NNK codon degeneracy, incorporating these alternative RVDs at defined positions within TALE arrays, and screening against targets containing all four nucleotides at corresponding positions [21]. This high-throughput methodology evaluated approximately 18,000 TALEN/target combinations, identifying ncRVDs with novel exclusion properties - the ability to discriminate against specific nucleotides while maintaining robust activity on the intended nucleotide [21].

Experimental Workflow for Specificity Optimization

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for enhancing TALEN specificity using non-conventional RVDs. The process begins with library construction, proceeds through high-throughput screening, identifies optimal ncRVDs with exclusion properties, and validates specificity enhancement in human cell systems.

Application Case Study: Discrimination of Highly Homologous Sequences

A compelling demonstration of TALEN specificity optimization comes from targeting the human HBB gene (associated with sickle cell anemia) while avoiding cleavage of the highly homologous HBD gene (94% identity) [21]. Researchers implemented an "exclusion strategy" by incorporating ncRVDs at mismatch positions between HBB and HBD sequences. These specialized ncRVDs maintained robust activity against the intended HBB target while discriminating against the HBD off-target, demonstrating the practical application of specificity-enhanced TALENs for therapeutic development [21].

The experimental protocol for this application involved:

- Identifying optimal target sites with minimal off-target sequences genome-wide

- Selecting ncRVDs with appropriate exclusion properties for mismatch positions

- Constructing TALEN arrays incorporating these ncRVDs

- Transfecting human cells and measuring cleavage efficiency at both on-target and off-target sites

- Validating specificity using sequencing-based methods to detect indels

This approach successfully generated TALENs capable of discriminating between sequences with 94% identity, highlighting the power of engineered specificity for targeting disease-associated genes with high homology to other genomic regions [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for TALEN Engineering

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for TALEN Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| TALEN Scaffolds | Golden Gate assembly systems [20], Solid-phase assembly [21] | Modular TALEN construction with varying repeat lengths |

| RVD Modules | Conventional RVDs (NI, HD, NN, NG) [17], Non-conventional RVD libraries [21] | Target sequence recognition with tunable specificity |

| FokI Nuclease Variants | Wild-type FokI, Obligate heterodimers (EL/KK, ELD/KKR) [19] | DNA cleavage with controlled dimerization requirements |

| Specificity Assessment Tools | In vitro selection libraries [19], High-throughput sequencing assays | Comprehensive off-target profiling |

| Delivery Systems | mRNA, Plasmid DNA, Viral vectors (lentiviral, AAV) [17] | Efficient intracellular TALEN delivery |

The development of modular TALEN assembly systems, particularly Golden Gate assembly, has significantly streamlined TALEN construction despite the inherent complexity of protein engineering [20]. These systems utilize standardized parts and type IIS restriction enzymes to efficiently assemble repeat arrays, making TALEN technology more accessible to research laboratories [20]. For specificity assessment, in vitro selection methods using highly diverse DNA libraries (10¹² sequences) provide comprehensive profiling of TALEN cleavage preferences beyond what is achievable through cellular methods alone [19].

TALEN technology represents a powerful genome editing platform with distinct advantages in targeting specificity, a critical parameter for therapeutic applications. The simple, predictable DNA recognition code of TALENs provides a foundation for ongoing optimization efforts, including the development of non-conventional RVDs with enhanced discriminatory capabilities [21]. While CRISPR systems offer advantages in design simplicity and multiplexing capacity, TALENs maintain an important position in the genome editing toolbox, particularly for applications requiring maximal precision and minimal off-target effects [16].

Future directions in TALEN development include continued expansion of the RVD repertoire, optimization of domain architectures for improved DNA binding specificity, and integration with emerging delivery technologies. As the field advances toward clinical applications, the refined specificity of TALENs positions them as valuable tools for precision genetic engineering, complementing rather than competing with other genome editing platforms [7]. The choice between TALEN, CRISPR, and ZFN technologies ultimately depends on specific research requirements, with TALENs offering an optimal balance of targeting flexibility and precision for many applications.

The advent of programmable gene-editing technologies has revolutionized molecular biology, providing researchers with unprecedented tools for investigating gene function and developing therapeutic interventions. Among these technologies, Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas system represent three generations of engineered nucleases that have successively transformed the field. While ZFNs and TALENs demonstrated the feasibility of targeted genome engineering, the discovery and adaptation of CRISPR-Cas systems have truly democratized gene editing due to their exceptional simplicity and versatility [22] [23].

This comparison guide objectively examines these three gene-editing platforms, focusing specifically on how CRISPR's unique RNA-guided mechanism has addressed many limitations of its protein-based predecessors. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical resources to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals select the most appropriate technology for their specific applications.

Molecular Mechanisms: A Tale of DNA Recognition Strategies

The fundamental difference between these technologies lies in their mechanisms for DNA recognition: ZFNs and TALENs rely on custom-engineered proteins, while CRISPR-Cas systems utilize a programmable RNA molecule for target recognition.

Protein-Based Recognition: ZFNs and TALENs

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) are fusion proteins comprising a DNA-binding domain and a FokI nuclease domain. Each zinc finger motif recognizes approximately 3 base pairs of DNA, and multiple fingers are assembled to create a domain that recognizes a specific 9-18 bp sequence. Since FokI requires dimerization to become active, two ZFN monomers must bind opposite strands of DNA with correct orientation and spacing to create a double-strand break [22] [23].

TALENs similarly utilize the FokI nuclease domain but employ Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) proteins for DNA recognition. Each TALE repeat recognizes a single base pair through highly variable repeat di-residues, making the engineering process more straightforward and predictable than zinc finger assembly. Like ZFNs, TALENs function as pairs binding to opposing DNA strands and require FokI dimerization for DNA cleavage [22] [23].

RNA-Guided Recognition: The CRISPR-Cas System

The CRISPR-Cas system functions as an adaptive immune system in bacteria and archaea. The most widely used CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two key components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA is a synthetic fusion of two natural RNAs - CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) - creating a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [24] [25]. The ~20 nucleotide sequence at the 5' end of the gRNA directs Cas9 to complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), typically 5'-NGG-3' for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9. Upon binding, Cas9 induces a double-strand break in the target DNA [24].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in DNA recognition between these systems:

Comparative Analysis: Key Features for Research Applications

The different DNA recognition mechanisms of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR translate into distinct practical advantages and limitations for research and therapeutic applications. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of their key characteristics:

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs | ZFNs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Molecule | Guide RNA (gRNA) | Engineered TALE protein | Engineered zinc finger protein |

| Target Recognition | RNA-DNA hybridization | Protein-DNA interaction | Protein-DNA interaction |

| Ease of Design | Simple (change 20-nt gRNA sequence) | Moderate (protein engineering required) | Complex (protein engineering required) |

| Development Time | Days | Weeks to months | Months |

| Cost | Low | High | High |

| Specificity | Moderate (subject to off-target effects) | High | High |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs simultaneously) | Limited | Very limited |

| Efficiency | High | Moderate to high | Moderate |

| Optimal Applications | High-throughput screens, multiplexed editing, rapid prototyping | Applications requiring high specificity, clinical applications | Validated therapeutic applications |

| PAM Requirement | Yes (varies by Cas variant) | No | No |

Table 1: Comparative analysis of major gene-editing platforms. Data synthesized from multiple sources [22] [23].

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Editing Efficiency and Specificity

Recent studies directly comparing these technologies provide quantitative insights into their performance. In a landmark study targeting the CCR5 gene (a co-receptor for HIV), CRISPR demonstrated significantly higher editing efficiency (approximately 60-80% modification rates in human cells) compared to TALENs (typically 30-50% efficiency) [22]. However, TALENs showed fewer off-target effects in deep-sequencing analyses, with CRISPR exhibiting detectable off-target activity at sites with 3-5 nucleotide mismatches to the gRNA [22] [23].

Advanced CRISPR systems have been developed to address specificity concerns. High-fidelity Cas9 variants (such as SpCas9-HF1 and eSpCas9) incorporate mutations that reduce off-target effects by strengthening Cas9's binding specificity to the target DNA [22]. Additionally, CRISPR-Cas systems derived from different bacterial species (such as Cas12a) often exhibit different PAM requirements and editing signatures, providing researchers with options to optimize specificity for particular genomic contexts [26] [25].

Practical Implementation: Time and Resource Requirements

The simplicity of CRISPR system design translates into dramatic reductions in both time and cost. While developing a new ZFN or TALEN pair typically requires 4-8 weeks of protein engineering and validation at a cost of $5,000-25,000+, a new CRISPR target can be designed in days for approximately $50-200 (including gRNA synthesis) [22] [23]. This efficiency advantage makes CRISPR particularly suitable for high-throughput screens and iterative experimental approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Technology Evaluation

Protocol: Comparative Assessment of Editing Efficiency

Objective: To quantitatively compare the editing efficiency and specificity of CRISPR, TALEN, and ZFN platforms at the same genomic locus.

Materials:

- HEK293T cells or other relevant cell line

- Plasmid constructs encoding: (1) SpCas9 + target-specific gRNA, (2) TALEN pair for same target, (3) ZFN pair for same target

- Transfection reagent

- Genomic DNA extraction kit

- PCR primers flanking target site

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Methodology:

- Design and clone editing constructs for all three platforms to target the same 20-30 bp genomic region.

- Transfect cells with each construct individually, including untransfected controls.

- Harvest cells 72 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

- Amplify target region by PCR and subject amplicons to next-generation sequencing.

- Analyze sequencing data using computational tools (such as CRISPResso2 for CRISPR, TALEN-specific, and ZFN-specific analysis pipelines) to quantify:

- Indel frequencies at on-target site

- Mutation spectra (distribution of insertions vs. deletions)

- Off-target editing at predicted secondary sites

Expected Outcomes: CRISPR typically shows highest on-target efficiency, while TALENs often demonstrate superior specificity with minimal off-target activity [22] [23].

Protocol: Multiplexed Editing Capability Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the capacity of each platform for simultaneous editing of multiple genomic loci.

Materials: As above, with multiple gRNA/TALEN/ZFN constructs.

Methodology:

- For CRISPR: Clone 3-5 different gRNA expression cassettes into a single vector with Cas9.

- For TALENs/ZFNs: Attempt co-transfection of 3-5 different TALEN or ZFN pairs.

- Transfert cells and analyze editing efficiency at each target locus as described in Protocol 5.1.

- Compare the efficiency of multiplexed editing versus single editing for each platform.

Expected Outcomes: CRISPR systems maintain high efficiency when targeting multiple loci simultaneously (typically 40-70% efficiency per locus), while TALEN and ZFN efficiency dramatically decreases with increasing target number due to delivery challenges and potential cellular toxicity [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Editing Studies

Successful implementation of gene-editing technologies requires access to specialized reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential materials and their functions:

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Platform Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Expression Plasmids | px459 (CRISPR), Golden Gate TALEN kits, CompoZr ZFN vectors | Delivery of editing machinery to cells | Platform-specific |

| Delivery Tools | Lentiviral particles, Lipofectamine 3000, Electroporation systems | Introduction of editing constructs into cells | All platforms |

| Validation Tools | T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, next-generation sequencing | Detection and quantification of editing events | All platforms |

| Bioinformatics Resources | CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP, E-CRISP, TALEN-NT, ZFiT | Target site selection and off-target prediction | Platform-specific |

| Cell Culture reagents | HEK293T, HCT116, iPSCs; appropriate media and supplements | Provide cellular context for editing experiments | All platforms |

Table 2: Essential research reagents for gene-editing studies. Bioinformatics tools are particularly important for optimizing experimental design [25].

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

The therapeutic potential of gene-editing technologies is increasingly being realized in clinical trials. CRISPR-based therapies have shown remarkable success in treating sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia (with Casgevy receiving first regulatory approvals), hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (with Intellia's LNP-delivered CRISPR system reducing TTR protein by ~90%), and hereditary angioedema [27] [28].

Notably, both ZFNs and TALENs continue to have important therapeutic roles where their high specificity is advantageous. For example, TALEN-based allogeneic CAR-T cells (lasme-cel) have shown promising Phase 1 results in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with 42% of patients achieving complete remission [27].

The following diagram illustrates the clinical development pathway for gene-editing therapies, highlighting key considerations at each stage:

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

The gene-editing landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies building upon the CRISPR foundation:

Advanced CRISPR Systems

Base editing enables direct, irreversible conversion of one DNA base pair to another without double-strand breaks, significantly reducing indel formation [29] [22]. Prime editing offers even greater versatility, capable of making all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring donor DNA templates [27] [29].

AI-designed editors represent the cutting edge of CRISPR innovation. Recently, researchers used large language models trained on 1 million CRISPR operons to generate OpenCRISPR-1, a Cas9-like effector that is 400 mutations away from any natural protein yet shows comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 [26].

CRISPR Activation and Interference

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technologies use catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional regulators to precisely control gene expression without altering DNA sequences [24] [30]. These approaches are particularly valuable for functional genomics screens and disease modeling where reversible gene modulation is preferred.

The CRISPR-Cas system has undoubtedly revolutionized gene editing through its simple, RNA-guided programming mechanism, making sophisticated genome engineering accessible to virtually any molecular biology laboratory. Its advantages in ease of design, cost-effectiveness, multiplexing capability, and rapid implementation make it the default choice for most research applications [22] [23].

However, ZFNs and TALENs maintain important niches where their proven precision, reduced off-target effects, and established regulatory pathways provide distinct advantages, particularly in therapeutic contexts where maximal specificity is paramount [27] [23].

Researchers should base their platform selection on specific project requirements: CRISPR for most applications requiring flexibility and efficiency; TALENs for projects demanding maximal specificity with manageable target numbers; and ZFNs for specialized applications building on established systems. As all technologies continue to advance, particularly with AI-enabled design approaches [26], the future of gene editing promises even greater precision, efficiency, and therapeutic potential.

The advent of programmable genome editing has revolutionized biomedical research and therapeutic development, enabling scientists to modify DNA with unprecedented precision. Three technologies have been pivotal in this revolution: Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) systems. These technologies function as molecular scissors, creating targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA that harness cellular repair mechanisms to achieve desired genetic modifications. This guide provides a historical and technical comparison of these three foundational genome-editing platforms, offering researchers a objective framework for selecting appropriate tools for specific applications. Understanding their developmental trajectories, relative strengths, and limitations is crucial for advancing basic research and developing next-generation genetic therapies [31] [32] [33].

Historical Timeline of Development

The development of programmable nucleases unfolded over two decades, with each technology building upon lessons learned from its predecessor. The following timeline visualizes these key milestones, from the initial protein engineering efforts to the widespread adoption of RNA-programmable systems.

Table: Key Technology Platforms and Their Origins

| Technology | Initial Discovery/Concept | First Human Cell Application | First Clinical Trial | Regulatory Approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | 1996 (ZFN concept) [33] | 2005 [31] | 2014 (HIV via CCR5 modification) [31] [34] | - |

| TALENs | 2011 [31] [32] | 2011 [31] | - | - |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | 2012 (Adapted for eukaryotes) [31] | 2013 | 2016 (Non-small cell lung cancer) [31] | 2023 (Casgevy for sickle cell disease) [31] |

Technical Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

All three editing platforms function by creating targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, but achieve this through distinct molecular mechanisms:

ZFNs utilize a DNA-binding domain composed of zinc finger motifs (each recognizing a 3-base pair DNA triplet) fused to the FokI nuclease domain. FokI must dimerize to become active, requiring two ZFN monomers to bind opposite DNA strands in a tail-to-tail orientation with a specific spacer sequence between them [34] [33].

TALENs similarly employ the FokI nuclease domain but use Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) repeats for DNA recognition. Each TALE repeat recognizes a single nucleotide, following a simple code that makes design more straightforward than ZFNs. Like ZFNs, TALENs require dimerization of FokI domains for activity [35] [22].

CRISPR-Cas9 employs a fundamentally different mechanism based on RNA-DNA hybridization. The Cas9 nuclease is directed to its target by a guide RNA (gRNA) that is complementary to the DNA sequence of interest. Target recognition requires both gRNA complementarity and the presence of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site [35] [22].

After DSB creation, all platforms rely on endogenous cellular repair pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels), typically leading to gene knockout.

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): Uses a donor DNA template to enable precise gene insertion or correction [34] [33].

Core Experimental Protocol

A generalized workflow for genome editing experiments encompasses several key stages, from target selection to validation. The following diagram illustrates this process, highlighting how different nuclease platforms integrate into a shared experimental structure.

Key Methodological Considerations:

Target Selection: For CRISPR, targets must be adjacent to appropriate PAM sequences (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9). For ZFNs and TALENs, targets must allow for appropriate spacer distances between binding sites for FokI dimerization [35] [33].

Reagent Design and Assembly:

- CRISPR: Synthesize ~20 nt gRNA sequence complementary to target; clone into appropriate expression vector with Cas9.

- TALENs: Assemble TALE repeat arrays using modular cloning systems (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) to match target sequence.

- ZFNs: Engineer zinc finger arrays to recognize target triplets; more complex due to context-dependent effects [35] [22].

Delivery Methods: Common approaches include:

Validation Techniques:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Technologies

Table: Comprehensive Performance Metrics of Genome Editing Technologies

| Parameter | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Size Limitation | ~18 bp [35] | Variable length (typically 30-40 bp) [35] | 20 nt + PAM (NGG for SpCas9) [35] |

| Design & Assembly Time | Several months [35] [22] | Several days to weeks [35] | 1-3 days [22] |

| Relative Cost | High [22] | Moderate to High [22] | Low [22] |

| Editing Efficiency | Moderate (Varies by target) [35] | High (>90% in some studies) [35] | Moderate to High (typically 60-80%) [36] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited [22] | Limited [22] | High (multiple gRNAs simultaneously) [22] |

| Primary Applications | Gene knockout, gene correction [34] | Gene knockout, gene correction [35] | Gene knockout, screening, activation/repression [36] |

Table: Experimental Success Metrics in Different Biological Contexts

| Experimental Context | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immortalized Cell Lines | Moderate efficiency [36] | High efficiency [36] [35] | High efficiency (>80% in optimal conditions) [36] |

| Primary Cells (T cells) | Challenging, lower efficiency [36] | Moderate efficiency [36] | Moderate efficiency, protocol-dependent [36] |

| Heterochromatin Regions | Not well characterized | 5x more efficient than CRISPR in heterochromatin [37] | Lower efficiency in densely packed DNA [37] |

| Time to Generate Knockouts | 3-6 months [36] | 3-6 months [36] | ~3 months [36] |

| Time to Generate Knock-ins | 6+ months [36] | 6+ months [36] | ~6 months [36] |

Key Experimental Findings

Recent comparative studies have revealed context-specific advantages for each technology:

Heterochromatin Performance: A 2020 study using single-molecule imaging demonstrated that TALENs are up to five times more efficient than CRISPR-Cas9 at editing genes within heterochromatin, the densely packed regions of DNA that contain many disease-relevant genes. This suggests TALENs may be preferable for targets in these challenging genomic regions [37].

Editing Specificity: Research comparing off-target effects has shown that TALENs generally exhibit fewer off-target mutations than first-generation CRISPR-Cas9 systems, though high-fidelity Cas9 variants have substantially closed this gap [35] [22].

Workflow Efficiency: Surveys of research laboratories indicate that CRISPR workflows typically require 3 months to generate knockouts and 6 months for knock-ins, with researchers reporting repeating clonal isolation steps a median of 3 times before achieving desired edits, regardless of the technology used [36].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents for Genome Editing workflows

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Technology Applicability |

|---|---|---|

| FokI Nuclease Domain | DNA cleavage component | ZFNs, TALENs |

| Zinc Finger Arrays | Sequence-specific DNA binding | ZFNs only |

| TALE Repeat Arrays | Sequence-specific DNA binding | TALENs only |

| Cas9 Nuclease | RNA-guided DNA cleavage | CRISPR-Cas9 |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Target recognition molecule | CRISPR-Cas9 |

| Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) | Cas9 recognition sequence | CRISPR-Cas9 |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery of editing components | All platforms |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Viral vector for in vivo delivery | All platforms (size-limited) |

| Electroporation Systems | Physical delivery method ex vivo | All platforms |

| Repair Template Donor DNA | Homology-directed repair template | All platforms (for knock-in) |

The historical development of genome editing technologies reveals a clear trajectory toward increased accessibility, efficiency, and application breadth. ZFNs established the fundamental principle that programmable nucleases could stimulate targeted genome modification, while TALENs simplified the design process and demonstrated particular efficacy in heterochromatin regions. CRISPR-Cas9 has dramatically democratized genome editing through its simplicity and versatility, leading to its rapid dominance in research and clinical applications.

Each platform retains distinct advantages: CRISPR for multiplexed applications and straightforward design, TALENs for challenging targets in heterochromatin, and ZFNs for well-established clinical applications where their profile is favorable. The optimal choice depends on the specific experimental requirements, including target genomic context, desired modification type, delivery constraints, and regulatory considerations. As all three technologies continue to evolve through protein engineering and delivery optimization, their complementary strengths will likely expand the therapeutic landscape for genetic disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases.

From Bench to Bedside: Practical Applications and Workflow Design

The advent of programmable nucleases has revolutionized genetic engineering, enabling precise modifications across diverse biological systems. Among these tools, Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system represent three generations of genome editing technology [38]. Each platform operates on the fundamental principle of creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA at predetermined genomic locations, harnessing cellular repair mechanisms—either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or high-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR)—to achieve desired genetic outcomes [38] [39]. Selecting the optimal tool requires careful consideration of project-specific requirements for precision, scale, and available resources. This guide provides a structured comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9, supported by experimental data and methodologies, to inform decision-making for researchers and drug development professionals.

Technology Comparison: Mechanisms, Applications, and Performance

Fundamental Mechanisms and Design

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) are chimeric proteins comprising a DNA-binding domain—composed of engineered zinc finger motifs—fused to the FokI nuclease domain [38] [35]. Each zinc finger motif recognizes a specific DNA triplet, and multiple fingers are assembled to target a longer sequence (typically 9-18 bp) [38]. A functional nuclease requires a pair of ZFNs binding to opposite DNA strands with a specific spacer sequence (5-6 bp) between them, enabling FokI dimerization and subsequent DNA cleavage [38]. ZFNs were foundational in demonstrating the feasibility of targeted DSB-induced genome editing [35].

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) also utilize the FokI nuclease domain but employ DNA-binding domains derived from TALE proteins of Xanthomonas bacteria [38]. Their key advantage is a simpler, modular recognition code: each TALE repeat (33-35 amino acids) binds a single nucleotide, with specificity determined by two key amino acids (Repeat-Variable Diresidues, RVDs) [40] [38]. Like ZFNs, TALENs function as pairs binding opposite DNA strands, requiring a spacer sequence (12-19 bp) for FokI dimerization [38].

CRISPR-Cas Systems represent a paradigm shift from protein-based to RNA-guided DNA recognition [39]. The most common system, CRISPR-Cas9, uses a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that combines CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a complementary DNA target sequence [35] [39]. Critical for target recognition is a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which is 'NGG' for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) [39] [35]. Cas9 induces a DSB upon successful sgRNA binding and PAM recognition [38].

Diagram 1: Genome Editing Tool Mechanisms. The diagram illustrates the distinct DNA recognition and cleavage mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9, TALEN, and ZFN systems, converging on the creation of double-strand breaks repaired by cellular pathways.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table synthesizes experimental data on the efficiency, specificity, and practical application parameters of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9.

Table 1: Performance and Practical Comparison of Major Genome Editing Tools

| Parameter | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency (Editing Rate) | 0%–12% (Low) [39] | 0%–76% (Moderate) [39] | 0%–81% (High) [39] |

| Target Site Size | 18–36 bp per ZFN pair [39] | 30–40 bp per TALEN pair [39] | ~22 bp (gRNA specific) [39] |

| Design Complexity | Difficult; requires expert knowledge of zinc finger assembly [35] [22] | Complex; simpler code than ZFNs but laborious protein engineering [35] [22] | Very simple; requires only gRNA sequence design [38] [22] |

| Development Timeline | Months [35] [22] | ~1 Month [38] [35] | Within a week [38] [22] |

| Relative Cost | High [38] [35] | Medium/High [38] [35] | Low [38] [35] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Less feasible [39] | Less feasible [39] | Highly feasible [39] [22] |

| Off-Target Risk | Less predictable [39] | Lower than CRISPR; highly specific [40] [23] | Highly predictable; potential for higher off-target effects [39] [23] |

| Primary Advantage | Proven precision in clinical applications [22] | High specificity with flexible targeting [40] [23] | Unmatched ease of use, scalability, and cost-effectiveness [22] [35] |

Key Factor Analysis for Tool Selection

Precision and Specificity

- TALENs often exhibit the highest specificity, attributed to their longer, protein-based target recognition and the requirement for FokI dimerization, which minimizes off-target cleavage [40] [23]. A study targeting the CCR5 gene found TALENs produced significantly fewer off-target mutations than ZFNs [35].

- ZFNs also demonstrate high precision due to their protein-DNA interaction mechanism, making them suitable for therapeutic applications where validated edits are critical [22].

- CRISPR-Cas9, while highly efficient, has a greater potential for off-target effects because the gRNA may tolerate mismatches, particularly outside the seed sequence [39] [23]. However, its off-target sites are highly predictable computationally, and engineered high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) have been developed to mitigate this issue [22].

Experimental Scale and Multiplexing

- CRISPR-Cas9 is the undisputed leader for large-scale and multiplexed experiments. Its RNA-based design allows for the simultaneous expression of numerous gRNAs from a single construct, enabling genome-wide library screens and the modification of multiple genetic loci in one experiment [39] [22]. This is a key advantage for functional genomics and identifying gene dependencies in drug discovery [22].

- TALENs and ZFNs are poorly suited for multiplexing. Designing and delivering multiple large, protein-based nucleases is labor-intensive, costly, and faces technical challenges in delivery [22].

Resource and Practical Considerations

- CRISPR-Cas9 requires minimal specialized expertise and financial investment compared to older technologies. Designing a new gRNA is fast and inexpensive, making CRISPR the most accessible and user-friendly tool [35] [22].

- TALENs, while easier to design than ZFNs due to their one-to-one nucleotide recognition code, still require complex protein engineering and are time-consuming to develop [35].

- ZFNs are the most resource-intensive, demanding extensive expertise in zinc finger assembly and a lengthy development process, which limits their widespread adoption [35] [22].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Standard Workflow for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

The following protocol outlines a typical CRISPR-Cas9 experiment for gene knockout, a common application across basic research and therapeutic development.

Diagram 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in a standard CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing experiment, from design to validation.

Step 1: Target Selection and gRNA Design

- Procedure: Identify the genomic locus to be edited. Design a 20-nucleotide gRNA sequence that is complementary to the target DNA and immediately precedes a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence [39] [35].

- Critical Parameters: Utilize computational tools like CRISPOR or CHOPCHOP to select gRNAs with high predicted on-target efficiency and minimal off-target activity across the genome [25] [41].

- Controls: Design multiple gRNAs for the same target to account for potential variability in efficiency.

Step 2: Preparation of Editing Components

- For CRISPR-Cas9: Clone the designed gRNA sequence into a plasmid vector that also expresses the Cas9 nuclease (all-in-one vector) or prepare Cas9 protein/gRNA complexes as ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) for direct delivery [22].

- For TALENs/ZFNs: Clone the genes encoding the engineered TALEN or ZFN pairs into appropriate expression plasmids. This step is significantly more time-consuming than CRISPR gRNA cloning [35].

Step 3: Delivery into Target Cells

- Methods: Choose a delivery method suitable for the cell type.

- Transfection: Chemical-based (e.g., lipofection) for easily transfectable cell lines.

- Electroporation: For primary cells or hard-to-transfect lines.

- Viral Vectors: Lentivirus or Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) for high efficiency and stable delivery, particularly in vivo [39] [22]. AAV has a limited cargo capacity, which can be a constraint for larger nucleases.

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): Increasingly used for in vivo therapeutic delivery, as demonstrated in recent clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) [28].

Step 4: Induction of Double-Strand Breaks and Repair

- Mechanism: After successful delivery and expression, the nuclease (Cas9, FokI dimer) creates a DSB at the target site.

- Pathway Selection:

- For Gene Knockout: Rely on the error-prone NHEJ pathway, which often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the gene's coding sequence [38] [35].

- For Precise Gene Editing: Co-deliver a donor DNA template with homologous arms to guide the HDR pathway for precise nucleotide changes or gene insertions [38].

Step 5: Validation and Analysis

- Genotypic Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from edited cells. Screen for modifications using methods like:

- T7 Endonuclease I or SURVEYOR Assay: Detects mismatches in heteroduplex DNA caused by indels.

- Sanger Sequencing or Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Provides the exact sequence of the edited locus. NGS is the gold standard for quantifying editing efficiency and profiling off-target effects [22].

- Phenotypic Analysis: Confirm functional consequences of the edit via Western blot (protein loss), flow cytometry (surface marker expression), or functional assays relevant to the target gene.

Case Study: CCR5 Gene Knockout

A comparative study aimed at knocking out the CCR5 gene (an HIV co-receptor) provides illustrative data [22]:

- Technology: Both TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9 were deployed.

- Outcome: TALENs achieved high specificity with minimal off-target effects. However, CRISPR-Cas9's superior efficiency and scalability made it the preferred choice for subsequent clinical trial development due to its ability to generate a sufficient population of edited cells more readily.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting genome editing experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Genome Editing Workflows

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Expression Vector | Delivers the gene for the editing nuclease (e.g., Cas9, FokI-fused TALE/ZF). | pSpCas9(BB) plasmid for CRISPR; custom TALEN/ZFN expression plasmids. |

| gRNA Cloning Vector / Oligos | For CRISPR; provides the target-specific guide RNA sequence. | Vectors with U6 promoter for gRNA expression; synthetic sgRNA for RNP formation. |

| Donor DNA Template | Serves as a repair template for HDR-mediated precise editing. | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) for point mutations; double-stranded DNA with homology arms for larger insertions. |

| Delivery Reagents | Facilitates the introduction of editing components into cells. | Lipofectamine, polyethyleneimine (PEI); Lonza, Neon systems for electroporation; viral packaging systems (lenti/AAV). |

| Cell Culture Media & Supplements | Supports the growth and viability of target cells during and after editing. | Standard media, serum, antibiotics, and cytokines specific to the cell type (e.g., IL-2 for T-cells). |

| Selection Agents | Enriches for successfully transfected/transduced cells. | Puromycin, blasticidin, G418 if the vector contains a resistance marker. |

| Genomic DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality DNA for downstream genotypic analysis. | Kits from QIAGEN, Thermo Fisher, etc. |

| Validation Assay Kits | Detects and quantifies the presence of genetic edits. | T7 Endonuclease I kit; commercial NGS library prep kits for amplicon sequencing. |

The selection of a genome editing tool is a strategic decision that balances precision, scale, and resources. ZFNs offer high precision but are resource-intensive, confining them to niche applications, particularly in validated therapeutic contexts. TALENs provide an excellent balance of high specificity and flexible targeting, making them ideal for projects where minimizing off-target effects is the paramount concern, and protein engineering resources are available. CRISPR-Cas9 stands out for its unparalleled ease of use, cost-effectiveness, and scalability, solidifying its role as the default choice for most applications, especially high-throughput screening and multiplexed editing.

Future directions point toward increased convergence and specialization. While CRISPR continues to dominate the landscape, its ongoing refinement—through high-fidelity Cas variants, base editing, and prime editing—will further enhance its precision [29] [22]. The choice is no longer static but should be re-evaluated based on the specific experimental question and the continuous evolution of these powerful technologies.

The ability to precisely modify the genome has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development. The landscape of gene editing has been shaped by several programmable nuclease technologies, chief among them being Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the more recent Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-associated system, CRISPR-Cas9 [42] [22]. ZFNs, among the first "genome editing" nucleases, use engineered zinc-finger proteins that typically recognize DNA triplets. These proteins are fused to the FokI nuclease, which requires dimerization to become active; consequently, a pair of ZFNs must be designed to bind upstream and downstream of the target site for effective cleavage [42] [43]. TALENs operate on a similar principle but utilize TALE (Transcription Activator-Like Effector) proteins, where each single TALE repeat recognizes one specific nucleotide. This makes their design more straightforward than ZFNs [42] [43].

The discovery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system marked a paradigm shift. Originally identified as part of the adaptive immune system in bacteria, it was harnessed for programmable genome editing in eukaryotic cells in 2012 and 2013 [44] [45]. Unlike ZFNs and TALENs, which rely on custom-designed protein-DNA interactions for specificity, CRISPR-Cas9 uses a guide RNA (gRNA) molecule to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a complementary DNA sequence. This RNA-based targeting mechanism dramatically simplifies the design process, reduces costs, and accelerates the pace of genetic research [22]. The following table provides a comparative overview of these key editing platforms.

Table: Key Feature Comparison of Major Genome Editing Nucleases

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Target Recognition | Protein-DNA interaction | Protein-DNA interaction | RNA-DNA interaction (Watson-Crick base pairing) [42] |

| Targeting Specificity | 9-18 bp (requires two binding sites) [42] | 30-40 bp (requires two binding sites) [42] | 20 bp gRNA sequence + PAM (e.g., 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) [42] |

| Molecular Scissors | FokI nuclease (must dimerize) [42] | FokI nuclease (must dimerize) [42] | Cas9 nuclease (single enzyme) [42] |

| Ease of Design & Cloning | Challenging; zinc finger motifs can affect neighbors [42] | Easy; well-defined TALE motifs [42] | Very easy; sgRNA design based on DNA complementarity [42] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Limited | Limited | High; multiple gRNAs can be used simultaneously [43] |

| Typical Development Time | Weeks to months [22] | Weeks [22] | Days [22] |

| Relative Cost | High [22] | High [22] | Low [22] |

The CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow: From Design to Analysis

Guide RNA (gRNA) Design and Optimization

The first and most critical step in any CRISPR experiment is the design of the guide RNA. The gRNA is a synthetic RNA composed of a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) sequence, which is ~20 nucleotides long and confers target specificity by base-pairing with the genomic DNA, and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) scaffold that binds to the Cas9 protein [46]. The target site in the genome must be immediately followed by a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which for the most common Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) is 5'-NGG-3' [42].

Design priorities include:

- On-target efficiency: Selecting a gRNA sequence that promotes highly efficient cleavage. This is influenced by factors such as genomic sequence context and chromatin accessibility.