Dynamic Control of Metabolic Pathways: Strategies to Reduce Toxic Intermediate Accumulation in Engineering and Therapeutics

This article explores the paradigm of dynamic control in metabolic pathways to mitigate the accumulation of toxic intermediates, a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and drug development.

Dynamic Control of Metabolic Pathways: Strategies to Reduce Toxic Intermediate Accumulation in Engineering and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm of dynamic control in metabolic pathways to mitigate the accumulation of toxic intermediates, a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and drug development. It covers foundational principles, demonstrating how intermediate toxicity shapes network regulation and evolutionary optimization. The content details cutting-edge methodological approaches, from biosensor-enabled feedback loops to live cell-based screening platforms. It further addresses troubleshooting for pathway optimization and provides validation through comparative analysis of real-world applications in bio-production and cancer therapy. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes interdisciplinary strategies to enhance product yields, improve cellular health, and develop novel therapeutics by mastering dynamic metabolic control.

The Problem of Toxic Intermediates: Foundational Concepts and Cellular Consequences

FAQs: Mechanisms and Identification

What are chemically reactive metabolites and how are they formed? Chemically reactive metabolites are electrophilic or radical intermediates produced during the metabolic breakdown of xenobiotics. They are formed primarily via Phase I metabolism, often catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes, which can convert relatively inert parent compounds into highly reactive species through processes like oxidation. This biotransformation, known as bioactivation, can produce electron-deficient molecules such as epoxides, quinones, quinone-imines, and iminium ions [1] [2]. While the goal of metabolism is typically to make lipophilic compounds more hydrophilic for excretion, bioactivation is an unintended consequence that can lead to cellular damage [1] [3].

What are the primary mechanisms by which reactive metabolites cause cellular damage? Reactive metabolites cause damage through three primary mechanisms:

- Covalent Binding: Electrophilic metabolites can form covalent adducts with nucleophilic sites on cellular macromolecules, including proteins, DNA, and lipids. This can alter protein structure and function, disrupt enzyme activity, and cause DNA damage leading to mutagenicity or carcinogenicity [1] [2].

- Oxidative Stress: Many reactive metabolites, including Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS), can trigger oxidative stress. This occurs when the production of these reactive molecules overwhelms the cell's antioxidant defenses (e.g., glutathione), leading to oxidation of lipids, proteins, and DNA [1] [4].

- Immune Activation: Metabolites that covalently modify proteins can create haptens—modified proteins that the immune system recognizes as "foreign." This can initiate an immune response, which is a proposed mechanism for many idiosyncratic adverse drug reactions [1].

Which subcellular organelles are most vulnerable? The mitochondrion is a key target. Reactive metabolites can induce mitochondrial dysfunction by impairing the electron transport chain, reducing ATP synthesis, and promoting the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. The nucleus is also highly vulnerable due to the risk of DNA adduct formation and genotoxicity. Furthermore, reactive metabolites can disrupt the endoplasmic reticulum and cell membrane, leading to impaired protein folding and loss of cellular integrity, respectively [4].

Why is the liver a common target for metabolite-mediated toxicity? The liver is the primary organ for drug metabolism and is exposed to high concentrations of orally administered drugs and their metabolites before they enter systemic circulation. Its high metabolic activity, particularly within hepatocytes, makes it a major site for the bioactivation of protoxins [1] [2].

FAQs: Experimental Troubleshooting

How can I experimentally detect and identify reactive metabolites in my assays? Direct detection is challenging due to their short half-lives. The standard approach involves trapping experiments using nucleophilic agents to form stable adducts that can be characterized with Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [2] [5].

- Glutathione (GSH): Used to trap soft electrophiles (e.g., quinones, quinone-imines).

- Potassium Cyanide (KCN): Used to trap hard electrophiles (e.g., iminium ions). After incubation with liver microsomes and NADPH, the trapped adducts are analyzed by LC-MS/MS to identify the structure of the original reactive metabolite [5].

My in vitro cytotoxicity assay shows promise, but how do I determine if toxicity is linked to reactive metabolite formation? Incorporate the following controls into your experimental design:

- Co-incubation with trapping agents: Add GSH or other nucleophiles to the incubation. A reduction in observed cytotoxicity suggests that the toxicity is mediated by reactive metabolites.

- Inhibition of metabolic enzymes: Use chemical inhibitors (e.g., 1-aminobenzotriazole for broad P450 inhibition) or perform assays in the absence of NADPH. A decrease in toxicity indicates that bioactivation is required.

- Use of metabolic systems: Compare toxicity in systems with high metabolic capacity (e.g., primary hepatocytes) versus low metabolic capacity (e.g., some engineered cell lines). Greater toxicity in metabolically competent systems is a strong indicator [6].

What are the best practices for designing safer drug candidates to avoid reactive metabolite formation? Medicinal chemistry strategies focus on structural refinement to block or divert bioactivation pathways:

- Remove or substitute structural alerts: Replace functional groups prone to bioactivation, such as anilines, furans, and thiophenes.

- Introduce metabolically stable groups: Incorporate fluorine atoms or deuterium to block metabolic hot spots.

- Promote alternative, safe metabolic pathways: Redirect metabolism towards Phase II conjugation (e.g., glucuronidation) which typically produces stable, excretable metabolites [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Metabolite Generation and Trapping in Human Liver Microsomes (HLMs)

This protocol is used to generate and identify both stable and reactive metabolites of a drug candidate [5].

Reagents:

- Test compound (e.g., Dubermatinib)

- Human or Rat Liver Microsomes (HLMs/RLMs)

- NADPH Regenerating System

- Phosphate Buffer (0.08 M, pH 7.4)

- Trapping Agents: Glutathione (GSH, 1.0 mM) or Potassium Cyanide (KCN, 1.0 mM)

- Termination Solvent: Ice-cold Acetonitrile

Procedure:

- Preparation: Prepare a primary incubation mixture containing HLMs (1 mg/mL protein) and the test compound (e.g., 30 µM) in phosphate buffer.

- Trapping: Add the chosen trapping agent (GSH or KCN) to the mixture.

- Pre-incubation: Equilibrate the mixture in a water bath at 37°C for 5 minutes.

- Initiation: Start the metabolic reaction by adding the NADPH regenerating system (1 mM final concentration). For negative controls, replace NADPH with buffer.

- Incubation: Allow the reaction to proceed for 60-90 minutes at 37°C.

- Termination: Stop the reaction by adding a two-fold volume of ice-cold acetonitrile.

- Analysis: Centrifuge the samples (13,000 × g, 10 min) to precipitate proteins. Analyze the supernatant using LC-MS/MS to identify stable phase I metabolites and trapped conjugates.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput GreenScreen (GS) Assay for Genotoxicity

This eukaryotic cell-based assay detects genotoxicity by monitoring the DNA damage response [6].

Reagents:

- Genetically engineered eukaryotic cell line (e.g., human TK6 cells) expressing a Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) reporter under the control of the GADD45a promoter.

- Test compound(s)

- ​​96-well microtiter plates

- Appropriate cell culture medium with and without metabolic activation (S9 fraction)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed the reporter cells into 96-well plates.

- Dosing: Treat the cells with a range of concentrations of the test compound. Include wells with and without exogenous metabolic activation (S9 fraction).

- Incubation: Incubate the plates for the recommended duration (typically 24-48 hours).

- Detection: Measure GFP fluorescence intensity using a plate reader. An increase in fluorescence indicates activation of the DNA damage response pathway (GADD45a).

- Analysis: Compare the fluorescence of treated cells to vehicle controls. A positive result suggests the compound or its metabolite(s) cause genotoxicity.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Types of Reactive Metabolites and Their Cellular Targets

| Reactive Metabolite Type | Example Structure | Primary Reactivity | Key Cellular Targets | Potential Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quinone-imine | NAPQI (Acetaminophen) | Electrophilic | Cellular proteins (Cysteine residues), Glutathione (GSH) [2] | Hepatotoxicity, Nephrotoxicity, GSH depletion [1] |

| Iminium ion | Metabolites from N-methyl piperazine (e.g., Dubermatinib) [5] | Electrophilic (hard) | DNA, GSH (trapped by KCN) [5] | Genotoxicity, Protein adduct formation |

| Epoxide | Arene oxides | Electrophilic | DNA, Proteins, GSH [1] | Genotoxicity, Carcinogenicity |

| Free Radicals / ROS | Trovafloxacin radical, Hydroxy radicals [1] [7] | Radical-based H-abstraction, Electron transfer | Lipids, Proteins, DNA, Mitochondria [1] [4] | Oxidative stress, Lipid peroxidation, Mitochondrial dysfunction |

| α,β-Unsaturated carbonyl | Acrolein (Cyclophosphamide) [2] | Michael acceptor (soft electrophile) | Proteins (Cysteine), GSH [2] | Bladder toxicity, GSH depletion |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolite and Toxicity Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Application in the Field |

|---|---|---|

| Human/Rat Liver Microsomes (HLMs/RLMs) | Source of cytochrome P450s and other drug-metabolizing enzymes for in vitro metabolism studies [6] [5]. | Fundamental for generating both stable and reactive metabolites to predict human and rodent metabolism [6]. |

| NADPH Regenerating System | Provides reducing equivalents (electrons) essential for cytochrome P450-mediated oxidative reactions [5]. | Required to initiate and sustain oxidative bioactivation in microsomal and cellular incubations. |

| Glutathione (GSH) | Endogenous tripeptide and nucleophile; used as a trapping agent for soft electrophilic metabolites [1] [5]. | Trapping experiments to screen for and identify soft electrophiles; also used to assess cellular antioxidant capacity. |

| Potassium Cyanide (KCN) | Trapping agent for hard electrophilic metabolites, such as iminium ions [5]. | Used in conjunction with GSH to provide a broader screen for different types of reactive metabolites. |

| S9 Liver Fraction | Post-mitochondrial supernatant containing cytosol and microsomal enzymes; used for metabolic activation in genotoxicity assays [6]. | Incorporated into assays like Ames and GreenScreen to provide a broader spectrum of metabolic enzymes. |

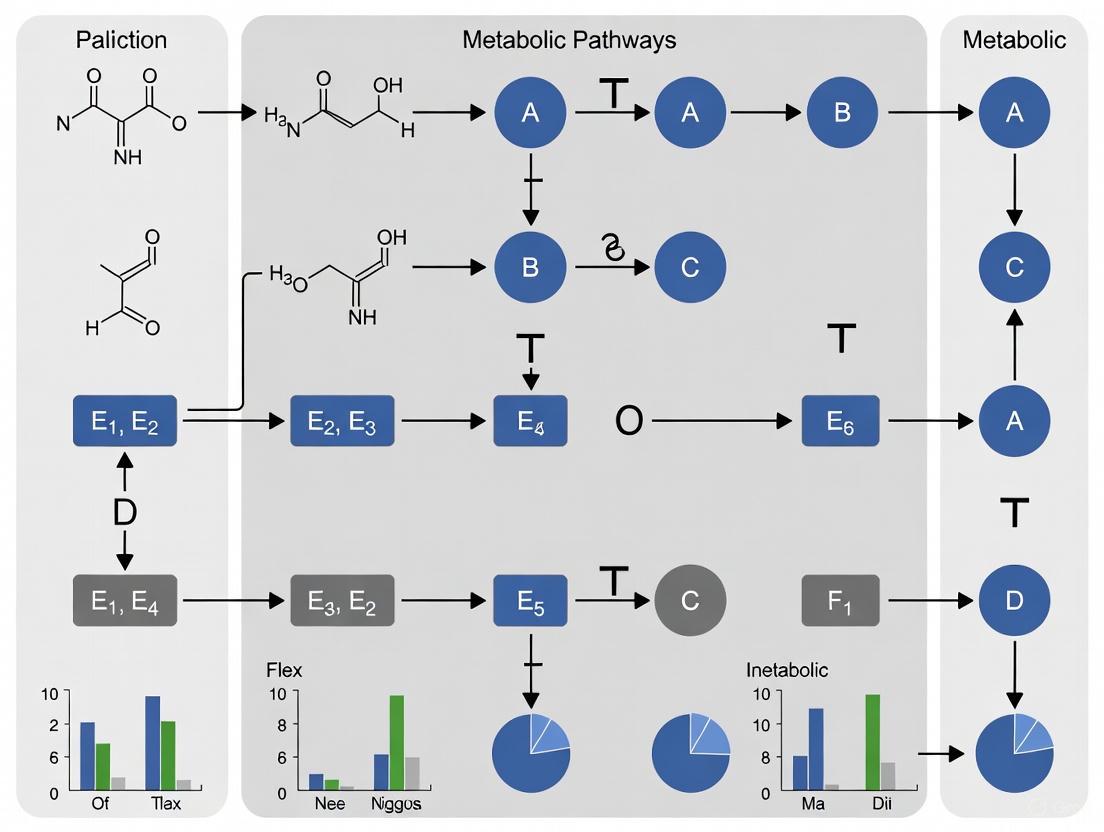

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Bioactivation Pathways

Toxicity Mechanisms

Experimental Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My engineered production strain shows excellent yield in simulations but grows extremely slowly in the bioreactor, hurting productivity. What is the cause and how can I fix it?

A: This is a classic symptom of the conflict between metabolic flux and cellular health. When you engineer a pathway for maximum yield, you often drain essential metabolites (like ATP or precursor metabolites) away from biomass synthesis and growth [8]. This creates a metabolic burden that impairs cellular health and slows growth rates.

Solution: Implement a dynamic two-stage fermentation strategy [8].

- Stage 1 (Growth Phase): Design a genetic circuit that keeps your product pathway inactive. This allows the cells to achieve a wild-type flux distribution and grow rapidly to a high cell density.

- Stage 2 (Production Phase): Introduce a trigger (e.g., a chemical inducer, temperature shift, or nutrient depletion) to activate the product pathway. This switches the metabolic flux toward high-yield production after robust biomass has been established.

Q2: During high-flux conditions, my cells accumulate toxic intermediates that inhibit growth and reduce product titers. What dynamic control strategies can prevent this?

A: Toxic intermediate accumulation often occurs when a downstream enzyme in your pathway becomes rate-limiting, causing a metabolic bottleneck.

Solution: Employ continuous dynamic control circuits that respond to the toxic intermediate itself [8].

- Mechanism: Engineer a biosensor that detects the concentration of the toxic intermediate. This biosensor can then regulate the expression of the downstream enzyme that consumes the intermediate.

- Outcome: When the intermediate level rises, the biosensor triggers increased expression of the downstream enzyme, clearing the bottleneck and preventing toxicity. This creates a self-regulating feedback loop that maintains flux while protecting cellular health.

Q3: How can I experimentally track and visualize the flow of metabolites through pathways to identify where conflicts between production and health are occurring?

A: The standard methodology is 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) [9].

- Protocol:

- Feed Labeled Substrate: Grow your cells on a culture medium where the carbon source (e.g., glucose) contains the 13C isotope.

- Harvest Samples: Take samples of the culture during steady-state growth.

- Analyte Extraction: Quench cellular metabolism rapidly and extract intracellular metabolites.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS) Analysis: Analyze the metabolites using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) to determine the patterns of 13C labeling.

- Computational Modeling: Use computational software to calculate the intracellular metabolic flux distribution that best fits the experimental 13C labeling data. This reveals the actual flow rates through the network's pathways [9].

For visualization, tools like Fluxer can directly use constraint-based models to compute and visualize flux distributions as interactive graphs, spanning trees, or dendrograms, making it easier to identify key routing points [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Probable Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low cell density in production phase | Excessive resource diversion to product pathway; nutrient depletion [8]. | Measure ATP/ADP ratio and check for accumulation of pathway intermediates. | Implement a two-stage dynamic control strategy to separate growth and production [8]. |

| Toxic intermediate accumulation | Imbalanced enzyme expression; kinetic bottleneck [8]. | Use LC-MS to quantify intermediate pools; test enzyme activities in vitro. | Engineer a biosensor for the intermediate to dynamically regulate downstream enzyme expression [8]. |

| Unpredicted low product yield despite high flux | Activation of bypass pathways or product degradation. | Perform 13C-tracer analysis to confirm carbon flow into the intended product [9]. | Knock out competing bypass reactions; use dynamic knockdown of key enzymes in rival pathways. |

| Genetic instability of production strain | Chronic metabolic burden from constitutive high-flux expression. | Serial passage experiments without selection; check for plasmid loss or suppressor mutations. | Use inducible promoters to avoid burden during non-production phases; integrate pathway into genome. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Two-Stage Fermentation for Dynamic Control

Objective: To decouple cell growth from product synthesis to achieve high biomass before inducing a high-flux production phase, thereby maximizing volumetric productivity [8].

Materials:

- Engineered microbial strain with inducible promoter controlling product pathway.

- Bioreactor with controlled temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen.

- Induction agent (e.g., Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), anhydrotetracycline, or a switch in carbon source).

Methodology:

- Growth Phase:

- Inoculate the production strain into the bioreactor with a complete growth medium.

- Maintain optimal conditions for growth (e.g., 37°C, adequate dissolved oxygen) while the inducible promoter for the product pathway is repressed.

- Monitor cell density (OD600) until it reaches the mid-to-late exponential phase.

- Induction / Production Phase:

- Introduce the induction agent to the bioreactor to activate the product pathway.

- Alternatively, trigger production by depleting a specific nutrient or shifting the temperature.

- Continue fermentation, monitoring substrate consumption and product formation.

- Analysis:

- Compare the final product titer, yield, and volumetric productivity (g/(L·h)) against a control strain with constitutive production. The two-stage process should yield a higher volumetric productivity despite a similar final product titer [8].

Protocol 2: 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

Objective: To quantitatively measure the in vivo flux distribution in a central metabolic network under specific experimental conditions [9].

Materials:

- 13C-labeled carbon source (e.g., [U-13C]glucose).

- Quenching solution (e.g., cold methanol).

- Extraction buffer.

- Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) system.

- 13C-MFA software (e.g., INCA, OpenFlux).

Methodology:

- Cultivation: Grow the cells in a bioreactor or controlled culture system with the 13C-labeled substrate as the sole or primary carbon source. Ensure metabolic and isotopic steady-state is reached.

- Sampling and Quenching: Rapidly withdraw culture samples and quench metabolism immediately (e.g., in cold aqueous methanol) to "freeze" the metabolic state.

- Metabolite Extraction: Disrupt the cells and extract polar metabolites (e.g., amino acids, organic acids) and non-polar metabolites.

- Derivatization and MS Analysis: Derivatize the metabolite extracts to make them volatile and analyze them via GC–MS.

- Flux Calculation:

- Input the MS data (mass isotopomer distributions), the biochemical network model, and extracellular flux measurements (e.g., substrate uptake, product secretion rates) into the 13C-MFA software.

- The software uses computational optimization to find the flux map that best fits the experimental labeling data. This provides a quantitative picture of carbon flow through the network [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key reagents and computational tools for analyzing and engineering metabolic flux.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Substrates | Tracer for 13C-MFA to quantify intracellular metabolic fluxes [9]. | Enables tracking of carbon fate through metabolic networks. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Provides external control over gene expression for dynamic pathway regulation [8]. | Allows temporal separation of growth and production phases. |

| Metabolite Biosensors | Detects intracellular metabolite levels to enable autonomous feedback regulation [8]. | Can be linked to promoter activity to dynamically control enzyme expression. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Constraint-based modeling to predict metabolic flux distributions and growth phenotypes [10]. | Useful for in silico design and testing of genetic interventions. |

| Fluxer Web Application | Computes and visualizes genome-scale metabolic flux networks from SBML models [10]. | Generates interactive spanning trees and flux graphs for intuitive analysis. |

| Escher | Web-based tool for building, viewing, and sharing visualizations of metabolic pathways [11]. | Allows visualization of omics data (e.g., fluxomics) overlaid on pathway maps. |

Metabolic Pathway Visualizations

Evolutionary Principles and Optimality in Pathway Regulation to Minimize Toxicity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does transcriptional regulation often target highly efficient enzymes in a pathway? Evolutionary optimality principles suggest that regulating highly efficient enzymes (those with high kcat and low Km) provides the most effective control over metabolic flux with minimal protein investment. Targeting these enzymes allows the cell to rapidly reduce the accumulation of toxic downstream intermediates by leveraging enzymes that have a high capacity to process substrates, thereby preventing bottlenecks that lead to toxicity. [12]

FAQ 2: What is a key evolutionary trade-off in pathway regulation? A fundamental trade-off exists between protein synthesis costs and regulatory effort. Pathways with low protein costs may only require sparse regulation (controlling a few key enzymes), whereas pathways with high protein costs benefit from pervasive, coordinated regulation of all enzymes to minimize the accumulation of toxic intermediates effectively. [12]

FAQ 3: How can "optimality principles" help identify novel drug targets? By applying dynamic optimization models, one can predict which enzyme inhibitions are most likely to cause the accumulation of endogenous toxic metabolites, leading to self-poisoning of a pathogen. This approach can reveal genetic minimal cut sets (gMCSs)—genes whose simultaneous inactivation is lethal—providing candidate targets for antimicrobial drugs. [12] [13]

FAQ 4: What is the difference between static and dynamic control in metabolic engineering?

- Static Control: Involves constitutive expression of pathway enzymes, tuned by selecting promoters and ribosome binding sites. It is a "set-and-forget" strategy.

- Dynamic Control: Uses genetically encoded circuits that allow cells to autonomously adjust metabolic flux in response to internal or external signals (e.g., metabolite levels). This is better suited for avoiding toxicity and managing metabolic burden in changing environments. [14]

FAQ 5: How can I experimentally measure if my intervention is reducing toxic intermediate accumulation? Metabolic tracing using stable isotopes (e.g., 13C-labeled substrates) is a powerful technique. By tracking the labeled atoms through the pathway over time, you can obtain a dynamic picture of flux and identify where intermediates are accumulating, which static metabolomics (a single snapshot) cannot achieve. [15]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Cell Growth or Viability Despite Successful Pathway Engineering

Potential Cause: Accumulation of toxic intermediates from the engineered pathway.

Solutions:

- Implement Dynamic Feedback Control: Introduce a biosensor that detects the level of the toxic (or precursor) intermediate. This biosensor should regulate the expression of the upstream enzymes, creating a feedback loop that reduces flux into the pathway when intermediate levels become too high. [14] [16]

- Apply a Two-Stage Fermentation Strategy: Decouple cell growth from product synthesis.

- Stage 1 (Growth): Under a permissive condition (e.g., with a repressor present), allow the cells to grow to a high density without producing the toxic compound.

- Stage 2 (Production): Induce a metabolic switch (e.g., by adding an inducer or changing temperature) to halt growth and activate the production pathway. [14]

- Re-engineer Enzyme Kinetics: If a particular step is a bottleneck, consider protein engineering to improve the catalytic efficiency (kcat) or substrate affinity (Km) of the enzyme that converts the toxic intermediate, thereby speeding up its clearance. [12]

Issue 2: Unpredictable or Highly Variable Product Yields

Potential Cause: Metabolic burden and resource competition, leading to instability and selection for non-producing mutants.

Solutions:

- Use Dynamic Population Control: Engineer a circuit where production of the desired compound is linked to the expression of an essential gene or an antibiotic resistance gene. This ensures that only high-producing cells survive under selective conditions, making the population more robust. [14]

- Inspect Regulatory Effort: Check if your regulatory strategy matches the pathway's protein cost. High-cost pathways may require more pervasive regulation. Consult optimization models to identify the key enzymes that should be regulated to minimize variance in flux. [12]

Issue 3: Difficulty in Identifying Which Enzymes to Target for Regulation

Potential Cause: Lack of knowledge about which steps most significantly impact toxicity and flux.

Solutions:

- Perform Genome-Scale Modeling: Use a Genome-scale Metabolic Model (GEM) of your host organism to compute Genetic Minimal Cut Sets (gMCSs). These are minimal sets of genes whose inactivation prevents growth (or another "unwanted state"). gMCSs can reveal single gene essentialities and synthetic lethalities that, when targeted, can force toxic accumulation. [13]

- Incorporate Metabolic Tasks: When using GEMs, do not only target biomass production. Include a set of essential metabolic tasks (e.g., ATP production, nucleotide synthesis) that any viable cell must perform. This expands the set of unwanted states and can reveal critical toxicity-related targets that would be missed by looking at biomass alone. [13]

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

This table summarizes parameters used in dynamic optimization studies to uncover optimal regulatory strategies for minimizing intermediate toxicity. [12]

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value / Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Concentration | e(_j)(t) | [0, ∞] | Time-dependent control variable for each enzyme j. |

| Enzyme Cost Weight | σ | 13 or 130 | Weighting factor balancing protein abundance cost against regulatory effort. |

| Toxicity Threshold | β(_i) | [0, 4]* | Maximum allowed concentration for intermediate metabolite i (e.g., analogous to IC50). |

| Turnover Number | k(_{cat,j}) | [0, 2]* | Catalytic efficiency of enzyme j. |

| Michaelis Constant | K(_{m,j}) | [0, 2]* | Inverse substrate affinity of enzyme j. |

| Optimization Time Span | T(_{max}) | 30 | Total duration of the simulated dynamic optimization. |

Parameters marked with an asterisk () are often sampled from the indicated range during large-scale computational analyses. [12]

Protocol 1: Dynamic Optimization of a Linear Metabolic Pathway

Objective: To identify the optimal time-course of enzyme concentrations that minimizes protein cost and regulatory effort while preventing the accumulation of toxic intermediates beyond a defined threshold.

Model Formulation:

- Define a linear metabolic pathway with 5 steps (a representative length) converting substrate S to product P.

- Formulate Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) for each metabolite, with fluxes described by Michaelis-Menten kinetics (parameters kcat and Km for each enzyme).

- Set a time-varying demand for the product P (e.g., a dilution rate v(_g)(t) that changes at t=10 and t=20) to simulate environmental changes. [12]

Define Constraints and Objective:

- Toxicity Constraints: For each intermediate metabolite i, impose an upper bound constraint: 0 ≤ x(i)(t) ≤ β(i). [12]

- Objective Function: Minimize the combined cost of protein abundance and regulatory effort over the entire time span T(_{max}):

F(e) = min ∑ [ σ · e_j(0) + (e_j(t) - e_j(0))^2 ] dt[12]

Solving the Optimization:

- Use dynamic optimization techniques (e.g., a quasi-sequential approach with moving finite elements).

- To avoid local optima, repeat the optimization ~100 times with random initializations for each parameter set.

- Analyze the relationship between the resulting optimal regulatory efforts and the parameters for enzyme efficiency (kcat, Km) and toxicity (β). [12]

Protocol 2: Identifying Gene Targets Using Genetic Minimal Cut Sets (gMCSs)

Objective: To find minimal sets of genes whose inactivation will disrupt a metabolic network, leading to growth arrest or toxic intermediate accumulation.

Model Contextualization:

Define Unwanted States:

- Traditional Approach: Define the target set as all network modes where biomass production is possible.

- Enhanced Approach (Recommended): Expand the target set to also include the failure of essential metabolic tasks. These are ~57 tasks critical for any human cell, such as ATP production, nucleotide synthesis, and lipid synthesis. [13]

Compute gMCSs:

- Use computational algorithms to calculate the genetic minimal cut sets. These are minimal sets of genes whose simultaneous inactivation hits all modes in the target set (i.e., prevents both biomass production and the essential tasks).

- gMCSs of length 1 represent essential genes; longer gMCSs reveal synthetic lethalities. [13]

Validation:

- The identified gMCSs are potential drug targets for killing unhealthy cells (e.g., cancer) or sources of gene toxicities to avoid in healthy tissues. [13]

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Resource | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., 13C-Glucose) | Used in metabolic tracing experiments to dynamically track the fate of atoms through pathways and identify flux bottlenecks leading to toxic accumulation. [15] |

| Biosensors & Genetic Circuits | Genetically encoded components (e.g., transcription factor-based biosensors) that detect metabolite levels and dynamically regulate enzyme expression to prevent toxicity. [14] [16] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) | A mathematical representation of cellular metabolism (e.g., Human1 model). Used to simulate metabolic behavior and compute gMCSs for target identification. [13] |

| Dynamic Optimization Software | Computational tools (e.g., in MATLAB or Python) to solve dynamic optimization problems and predict optimal enzyme expression profiles under toxicity constraints. [12] |

| Essential Metabolic Tasks List | A defined set of ~57 metabolic functions (e.g., ATP production, nucleotide synthesis) that any viable human cell must perform. Used to refine gMCS calculations. [13] |

| Two-Stage Inducible Systems | Genetic switches (e.g., inducible promoters) that allow decoupling of cell growth from product formation in a bioreactor, minimizing exposure to toxic intermediates. [14] |

| Didestriazole Anastrozole Dimer Impurity | Didestriazole Anastrozole Dimer Impurity, CAS:918312-71-7, MF:C26H29N3, MW:383.5 g/mol |

| 2-Methylindolin-1-amine hydrochloride | 2-Methylindolin-1-amine hydrochloride, CAS:31529-47-2, MF:C9H13ClN2, MW:184.66 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the common causes of toxicity in engineered metabolic pathways? Toxicity in engineered pathways primarily arises from two sources: (1) the accumulation of the final product or pathway intermediates to levels that disrupt cellular function, and (2) metabolite damage caused by enzymatic or chemical side-reactions. For instance, lycopene, a valuable carotenoid, is known to be toxic to E. coli due to its accumulation in the cellular membrane, leading to impaired growth and frequent genetic mutations in the production pathway [17]. Similarly, intermediates or non-native products can be wasteful and often toxic, disrupting the function of both native and engineered pathways [18].

Q2: How does toxicity contribute to the high failure rate in clinical drug development? Analysis of clinical trial data shows that approximately 30% of drug development failures are due to unmanageable toxicity [19]. This toxicity can result from either off-target effects (inhibition of unintended molecular targets) or on-target effects (inhibition of the disease-related target in vital tissues). A major factor is the accumulation of drug candidates in vital organs, for which traditional optimization strategies often overlook the systematic reduction of tissue-specific accumulation [19].

Q3: What is dynamic metabolic control and how can it mitigate toxicity? Dynamic metabolic control is a strategy that uses genetically encoded circuits to allow cells to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to their internal state. This is a powerful solution for mitigating toxicity. Instead of expressing pathway enzymes at constant, high levels, dynamic control can delay the expression of genes involved in producing toxic intermediates until the cell has reached sufficient biomass. It can also automatically downregulate pathways that compete for essential precursors, thereby balancing metabolic load and preventing the accumulation of harmful compounds [20] [21] [22].

Q4: Can you provide a real-world example where dynamic control successfully increased production? A prominent example is the biosynthesis of 4-hydroxycoumarin (4-HC), a precursor to anticoagulants, in E. coli. This pathway requires two precursors, salicylate and malonyl-CoA, which compete for carbon flux from central metabolism. Researchers engineered a self-regulated network where a salicylate-responsive biosensor dynamically controlled the supply of both precursors and the expression of key pathway genes. This ensured that carbon flux was allocated efficiently, preventing imbalance and toxicity, and ultimately led to improved 4-HC production [21].

Q5: What are metabolite damage and repair systems? Metabolic pathways are not perfectly specific. Metabolites can undergo damage via spontaneous chemical reactions or enzyme errors (promiscuity). Cells possess dedicated damage repair enzymes that either reconvert damaged molecules back to their normal state or safely dispose of harmful damage products. In metabolic engineering, neglecting these systems can lead to failure. Incorporating appropriate repair enzymes, such as phosphatases for removing erroneous phosphorylated metabolites, is often essential for the efficient operation of engineered pathways [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Debugging Poor Cell Growth or Genetic Instability in Production Strains

Problem: Your production strain exhibits uncharacteristically slow growth, fails to form colonies, or shows a high frequency of genetic mutations (e.g., deletions in the operon) after transformation.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Step | Problem & Symptoms | Diagnosis Method | Solution & Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Metabolic Burden: Slow growth across most constructs; general resource depletion. | Measure growth rate and plasmid stability of empty vector control vs. production constructs. | Use weaker promoters or inducible systems to decouple growth and production phases. Reduce gene dosage if possible [17] [22]. |

| 2. | Product/Intermediate Toxicity: Growth is construct-specific; mutations found in the pathway genes; toxic product accumulation (e.g., lycopene) [17]. | HPLC/MS to identify and quantify intermediate accumulation. Sequence colonies that fail to produce. | Implement dynamic regulation. Employ a biosensor that triggers the production pathway only after a certain cell density is reached, or in response to a specific metabolite [21] [22]. |

| 3. | Metabolite Damage: Accumulation of off-pathway, damaged metabolites that inhibit growth or disrupt function [18]. | Metabolomic profiling to identify non-canonical compounds. | Engineer repair systems. Identify potential damage-prone metabolites in your pathway and heterologously express corresponding repair enzymes (e.g., phosphatases, dehydrogenases) [18]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Low Titer and Yield Due to Precutor Imbalance

Problem: Your strain grows well, but the titer of the target product is low. Analysis shows an accumulation of one pathway intermediate and a depletion of another precursor.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Step | Problem & Symptoms | Diagnosis Method | Solution & Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Competition for Central Metabolites: The heterologous pathway competes with essential metabolism for precursors (e.g., PEP, acetyl-CoA). | Measure intracellular pools of central metabolites (e.g., via LC-MS). | Rewire central metabolism. Knock out competing, non-essential pathways. Use dynamic control to downregulate competing pathways only during the production phase [21] [22]. |

| 2. | Imbalance in a Multi-Precursor Pathway: One precursor (e.g., salicylate) accumulates while the other (e.g., malonyl-CoA) is depleted, creating a bottleneck [21]. | Quantify the concentrations of all required precursors simultaneously. | Implement a self-regulated network. Use a biosensor for the accumulating precursor to dynamically control the flux towards the other, limiting precursor, creating a feedback loop that balances their supply [21]. |

| 3. | Enzyme Promiscuity & Side-Reactions: Enzymes in the heterologous pathway act on non-physiological substrates, generating off-pathway, inhibitory products [18]. | Test enzyme specificity in vitro. Use computational tools (e.g., BNICE, Retropath) to predict potential side reactions. | Use enzyme engineering. Evolve enzymes for higher specificity. Alternatively, express repair enzymes to detoxify the side products [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: PASIV Workflow for Mapping the Viable Design Space

The Pooled Approach, Screening, Identification, and Visualization (PASIV) workflow is designed to overcome toxicity and burden issues that hamper the initial scoping phase of Design of Experiments (DoE) [17].

Application: Identifying viable genetic constructs (promoter/RBS/gene order combinations) for a toxic pathway, such as the lycopene pathway.

Materials:

- Library: A pooled library of all genetic variants (e.g., 810 constructs for a lycopene pathway with variations in promoter strength, RBS, and gene order).

- Chassis: Competent cells of your production host (e.g., E. coli).

- Media: Selective growth medium.

- Assay Reagents: Viability assay kit (e.g., based on ATP content or membrane integrity).

- Equipment: Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform.

- Software: Bioinformatics tools for construct matching and data visualization.

Procedure:

- Pooled Construction: Assemble the entire combinatorial library in a single "one-pot" multiplex reaction, rather than building individual constructs. This creates a highly diverse plasmid pool [17].

- Transformation & Culture: Transform the pooled plasmid library into the host chassis and plate on selective media. Allow colonies to develop, even if growth is slow (may take up to 72 hours) [17].

- Viability Screening: Instead of screening for product titer, perform a viability assay on the grown colonies. This identifies which constructs allow the cell to survive and grow, defining the "viable region of interest" [17].

- Identification (Construct Matching): Isemble plasmid DNA from the viable colonies and subject them to NGS. Use a novel bioinformatics construct matching tool to deconvolute the sequencing data and identify the specific genetic parts (promoter, RBS, gene order) associated with viable phenotypes [17].

- Visualization & Analysis: Visualize the results to see which regions of your combinatorial design space are viable. This viable region can then be used as the starting point for more focused screening and optimization DoE cycles [17].

Protocol: Implementing a Self-Regulated Network for Pathway Balancing

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a dynamic feedback system to balance precursors, as demonstrated in the 4-hydroxycoumarin (4-HC) case study [21].

Application: Balancing metabolic flux in pathways that require multiple precursors from the same central metabolic node.

Materials:

- Biosensor: A transcription factor/promoter system that responds to a key pathway intermediate (e.g., a salicylate-responsive biosensor).

- Actuators: CRISPRi system for gene repression and/or strong promoters for gene activation.

- Genetic Tools: Vectors for chromosomal integration or stable plasmid expression.

Procedure:

- Rewire Central Metabolism: Engineer the host's metabolic background to enhance the production of a key precursor. For example, to boost salicylate yield, delete the native pyruvate kinase genes (pykA and pykF) and glycerol dehydrogenase (gldA), making the salicylate pathway obligatory for generating pyruvate for cell growth [21].

- Integrate the Biosensor: Incorporate the salicylate-responsive biosensor into the host genome.

- Connect Biosensor to Actuators: Link the output of the biosensor to the expression of genes controlling the competing precursor.

- For malonyl-CoA supply: Use the biosensor to drive the expression of genes (accABCD) for acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which produces malonyl-CoA.

- For pathway gene expression: Simultaneously, use the biosensor to control the expression of key synthetic pathway enzymes (e.g., SdgA) via the CRISPRi system [21].

- Test and Validate: Ferment the engineered strain and measure both precursors and the final product over time. Validate the dynamic response by performing transcriptomic analysis to confirm that the transcription levels of target genes (e.g., pykF, sdgA) change according to the intermediate concentration [21].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Toxicity and Mitigation Strategies in Metabolic Engineering

| Case Study | Toxic Agent / Problem | Observed Impact (Without Mitigation) | Mitigation Strategy | Result (With Mitigation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopene Pathway [17] | Lycopene & Intermediates | Extremely slow growth (>72 hrs); high mutation/deletion rate; unreliable scoping. | PASIV Workflow (Pooled library + viability screening) | Identification of viable construct space enabling further screening. |

| 4-Hydroxycoumarin Pathway [21] | Imbalance of salicylate & malonyl-CoA | Suboptimal production due to competition for carbon flux. | Self-regulated network (Salicylate biosensor + dynamic control of malonyl-CoA supply) | Improved 4-HC production titer. |

| General Metabolite Damage [18] | Damaged metabolites (e.g., phosphorylated sugars, damaged cofactors) | Pathway inhibition; general cellular toxicity; reduced yield. | Expression of metabolite repair enzymes (e.g., phosphatases, DJ-1 deglycases) | Restored pathway flux and improved product yield in several engineered pathways. |

| Clinical Drug Development [19] | Drug accumulation in vital organs | 30% failure due to unmanageable toxicity in clinical trials. | Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) | Proposed framework to select candidates with better tissue selectivity, improving predicted therapeutic window. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

PASIV Workflow for Toxic Pathways

Self-Regulated Network for Precursor Balancing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Addressing Toxicity | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Biosensors | Detect intracellular concentrations of specific metabolites (e.g., intermediates, cofactors). Serves as the "sensor" in a dynamic control circuit. | A salicylate biosensor used to trigger malonyl-CoA synthesis in the 4-HC pathway [21]. |

| CRISPRi/a Systems | Acts as the "actuator" for precise gene repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) in response to a biosensor signal. | Dynamically controlling the expression levels of genes in a synthetic pathway to balance flux [21]. |

| Metabolite Repair Enzymes | Detoxify or remove aberrant, damaged metabolites that are not part of the canonical pathway but are formed by promiscuous enzyme activity or chemical decay. | Phosphatases to remove erroneous phosphorylations; glyoxalases to detoxify methylglyoxal [18]. |

| Optogenetic Systems (e.g., EL222) | Use light as an external, non-invasive inducer to dynamically control gene expression with high temporal precision. | A light-induced circuit used to decouple growth (light) and production (dark) phases for isobutanol synthesis [22]. |

| PASIV Bioinformatics Pipeline | A suite of computational tools for analyzing pooled library data, including "construct matching" to link viable phenotypes to specific genetic designs. | Identifying which promoter-RBS-gene order combinations for a lycopene pathway are non-toxic and support cell growth [17]. |

| Cyclopentane-1,2,3,4-tetracarboxylic acid | Cyclopentane-1,2,3,4-tetracarboxylic acid, CAS:3786-91-2, MF:C9H10O8, MW:246.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-(4-methoxyanilino)-2H-chromen-2-one | 4-(4-methoxyanilino)-2H-chromen-2-one, MF:C16H13NO3, MW:267.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Biosensors and Dynamic Control Modalities: From Theory to Application

Harnessing Native Stress-Response Promoters for Autonomous Metabolite Sensing

Core Principles and Quantitative Data

Native Promoter Characteristics and Performance

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Native Promoters in Microbial Systems

| Promoter Name | Organism | Type | Inducing Signal/Condition | Relative Strength | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RpoS (σS/σ38) | Escherichia coli | Inducible/General Stress | Stationary phase, nutrient depletion, cellular damage | N/A | General stress response, oxidative stress resistance [23] |

| pADH2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Inducible | Glucose depletion | N/A | Lycopene biosynthesis (3.3 mg/g DCW yield) [24] |

| pTDH3 | S. cerevisiae | Constitutive | N/A | Strong | General metabolic engineering [24] |

| pPGK1 | S. cerevisiae | Constitutive | N/A | Strong | General metabolic engineering [24] |

| pTEF1 | S. cerevisiae | Constitutive | N/A | Strong | General metabolic engineering [24] |

Table 2: Metabolite Sensor Performance Metrics Across Biofluids

| Biofluid | Key Detectable Metabolites | Approximate Concentration Ranges | Correlation with Blood Levels | Technical Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweat | Lactate, glucose, urea, cortisol, electrolytes | Varies by metabolite (e.g., cortisol: diagnostic range) | Limited correlation for some analytes | Individual variability, surface contamination [25] [26] |

| Saliva | Glucose, urea, cortisol, melatonin | Varies by metabolite | Good correlation for some hormones | Intra- and inter-individual variability [26] |

| Interstitial Fluid (ISF) | Metabolites, proteins, drugs, cytokines | >92% of RNA species found in blood | High correlation for many analytes | Dynamic dilution effects, cellular uptake [26] |

| Tears | Glucose, proteomic markers, inflammatory markers | Low concentrations for many analytes | Good correlation for glucose | Low analyte concentrations [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Promoter-Sensor Integration

Protocol 1: Engineering Autonomous Metabolite Sensing Systems

Objective: Implement a Tandem Metabolic Reaction (TMR) sensor system using native stress-response promoters for continuous metabolite monitoring.

Materials:

- Microbial chassis (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae)

- Native stress-response promoter sequences (see Table 1)

- Reporter genes (e.g., fluorescent proteins, enzymatic reporters)

- Electrodes with single-wall carbon nanotubes [25]

- Appropriate enzymes and cofactors for tandem metabolic reactions [25]

Procedure:

- Promoter Selection: Identify native promoters that respond to metabolic stress or target metabolites. For general stress response in E. coli, utilize the RpoS regulon [23].

- Genetic Construction: Clone selected promoter upstream of reporter genes in appropriate expression vectors.

- Sensor Assembly: Immobilize enzymes and cofactors on carbon nanotube electrodes to create TMR sensors capable of detecting over 800 metabolites [25].

- System Validation: Expose engineered systems to target metabolites and measure response kinetics.

- Performance Optimization: Fine-tune system components to achieve desired sensitivity and dynamic range.

Troubleshooting Tip: If signal-to-noise ratio is suboptimal, ensure reactions occur at low voltage to reduce undesired side reactions while maximizing enzyme activity utility [25].

Protocol 2: Assessing Metabolic Pathway Alterations in Response to Stress

Objective: Evaluate drug-induced metabolic changes using constraint-based modeling and transcriptomic profiling.

Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., AGS gastric cancer cells)

- Kinase inhibitors (TAKi, MEKi, PI3Ki)

- RNA sequencing tools

- MTEApy Python package for TIDE analysis [27]

Procedure:

- Treatment: Expose cells to individual inhibitors and synergistic combinations.

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Extract RNA and perform sequencing at multiple time points.

- Data Processing: Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using DESeq2 package [27].

- Pathway Analysis: Apply TIDE algorithm to infer metabolic pathway activity changes.

- Synergy Scoring: Quantify metabolic synergy by comparing combination treatments with individual drug effects.

Troubleshooting Tip: When observing unexpected transcriptional responses, consider that kinase inhibitors typically show larger numbers of up-regulated than down-regulated genes, potentially indicating stress response activation [27].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What are the advantages of using native stress-response promoters over synthetic systems for metabolite sensing?

A: Native promoters offer several advantages: (1) They have been refined through evolution for high sensitivity, specificity, and stability [25]; (2) They integrate naturally with the host's regulatory networks, allowing for autonomous operation; (3) They can respond to a wider range of metabolic stresses without requiring engineering of synthetic sensing components; (4) They often show graded responses that can be tuned for different applications [24].

Q: Why might my metabolite sensing system show poor correlation with actual metabolic states?

A: Common issues include: (1) Inadequate characterization of promoter response kinetics under your specific conditions; (2) Interference from parallel regulatory pathways; (3) Metabolic cross-talk where multiple metabolites affect your promoter; (4) Insufficient sensitivity of your reporter system. Ensure you fully map the regulatory components of your chosen promoter, including upstream activating sequences (UAS) and upstream repressing sequences (URS), which are typically located 100-1400 bp upstream of the core promoter and contain transcription factor binding sites that critically influence expression levels [24].

Q: How can I differentiate between specific metabolic responses and general stress responses in my sensing system?

A: Implement control systems using promoters that respond only to general stress (like RpoS in E. coli) alongside your specific metabolite-responsive promoters. The RpoS-mediated general stress response in E. coli provides resistance to diverse stresses including carbon starvation, oxidative stress, and osmotic stress, making it an excellent indicator of non-specific cellular stress [23]. By comparing activation patterns, you can distinguish specific metabolite responses from general stress artifacts.

Q: What computational approaches can help predict promoter-metabolite interactions before experimental validation?

A: Constraint-based modeling methods like TIDE can infer pathway activity from gene expression data without requiring full metabolic model reconstruction [27]. Additionally, deep learning approaches have been applied to promoter sequence identification, extracting features from organisms with extensive promoter data to predict function in target systems [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low signal output from metabolite sensing system

- Potential Causes: Weak promoter strength, inefficient reporter gene, suboptimal growth conditions

- Solutions:

Problem: High background noise in sensing measurements

- Potential Causes: Non-specific promoter activation, reporter instability, environmental interference

- Solutions:

- Engineer promoter regions to minimize non-specific transcription factor binding

- Incorporate noise-reduction elements in genetic circuits

- Use low-voltage detection systems to minimize undesired side reactions [25]

Problem: Inconsistent response across biological replicates

- Potential Causes: Population heterogeneity, slight environmental variations, genetic instability

- Solutions:

- Implement single-cell analysis to characterize response distributions

- Tighten control of cultivation conditions, particularly nutrient levels that affect stress responses

- Include internal calibration standards in experimental design

Problem: Sensor performance degrades over time

- Potential Causes: Resource depletion in continuous systems, genetic mutations, cellular stress

- Solutions:

- Implement nutrient replenishment strategies in continuous systems

- Use more stable genetic elements and regularly passage cultures

- Monitor general stress markers like RpoS to assess cellular health [23]

Pathway Diagrams and System Workflows

Native Stress-Response Pathway for Metabolite Sensing

Tandem Metabolic Reaction Sensor Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Native Promoter Metabolite Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotube Electrodes | Provide large active area for enzyme immobilization | TMR sensors for metabolite detection | Enable efficient reactions at low voltage with high signal-to-noise ratio [25] |

| Enzyme Cofactors | Essential for catalytic activity in metabolic reactions | Enabling detection of >800 metabolites | Required for replicating natural metabolic pathways in sensors [25] |

| DESeq2 Package | Statistical analysis of differential gene expression | Identifying transcriptomic changes in stress responses | Standard for RNA-seq data analysis in metabolic studies [27] |

| MTEApy Python Package | Implementing TIDE analysis for metabolic pathway inference | Analyzing drug-induced metabolic alterations | Open-source tool for constraint-based modeling [27] |

| Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes | Electrode material with large surface area | Biosensor platforms for continuous monitoring | Maximize enzyme loading capacity and reaction efficiency [25] |

| Kinase Inhibitors (TAKi, MEKi, PI3Ki) | Perturb signaling pathways to study metabolic responses | Investigating metabolic rewiring in cancer cells | Useful for studying stress response connections to metabolism [27] |

| 1-Methyl-4-(1-naphthylvinyl)piperidine | 1-Methyl-4-(1-naphthylvinyl)piperidine, CAS:117613-42-0, MF:C19H27N3O, MW:287.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| omega-Truxilline | omega-Truxilline|RUO | Bench Chemicals |

Engineering Synthetic Biosensors for Key Toxic Intermediates

A primary challenge in metabolic engineering is the accumulation of toxic intermediates, which can inhibit cell growth, reduce production yields, and lead to the selection of non-productive mutant strains [14]. Dynamic control strategies have emerged as a powerful solution to this problem. These strategies involve engineering microbial cells to autonomously regulate their metabolic fluxes in response to intracellular metabolite levels [16] [14]. Genetically encoded biosensors form the core of these intelligent systems, providing the critical link between sensing metabolic states and implementing appropriate regulatory responses [28].

Synthetic biosensors are engineered biological components that detect specific small molecules and convert this detection into a measurable output, typically a fluorescent signal or a change in gene expression [28]. When applied to toxic intermediates, these biosensors enable real-time monitoring and feedback control of metabolic pathways, allowing cells to dynamically balance growth and production phases [14]. This technical support document provides comprehensive guidance for researchers developing and implementing these sophisticated tools, with practical solutions for common experimental challenges.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Biosensor Design and Selection

Q: How do I select the appropriate biorecognition element for my target toxic intermediate?

A: The choice depends on the chemical nature of your intermediate and the available discovery tools. The table below summarizes the primary options:

Table: Biorecognition Elements for Toxic Intermediate Biosensors

| Element Type | Examples | Mechanism | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors (TFs) | TtgR, LysR-type, TetR-family [28] | Allosteric regulation of DNA binding | Known targets with characterized natural sensors | Often require engineering to modify specificity/dynamic range |

| Riboswitches/Aptazymes | glmS ribozyme [28] | Conformational change affecting translation or transcription | Targets without known protein sensors | Smaller genetic footprint; may have limited application scope |

| Protein Degradation Tags | Degrons [28] | Induced protein stability/degredation | Eukaryotic systems & slower-growing prokaryotes [28] | Faster response times; less commonly exploited [28] |

Q: What should I do if no natural biosensor exists for my target intermediate?

A: Consider these approaches:

- Explore promiscuous sensors: Test existing biosensors for structurally similar compounds, as many have broad specificity ranges [28].

- Employ directed evolution: Use random mutagenesis and high-throughput screening to alter the specificity of existing biosensors toward your target [28].

- Utilize aptamer selection: Implement Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) to develop novel nucleic acid-based aptamers [29].

Implementation and Integration Issues

Q: Why is my biosensor exhibiting high background noise in the absence of the target intermediate?

A: High background signal typically stems from insufficient specificity or leaky expression:

- Solution 1: Optimize your expression system by testing different promoters with lower basal activity.

- Solution 2: Implement a dual selection system where the biosensor controls both a positive (e.g., antibiotic resistance) and negative (e.g., toxin) selector to enrich for specific variants [28].

- Solution 3: For TF-based sensors, modify the operator sequence or apply directed evolution to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Q: How can I adapt my biosensor for in-line dynamic control rather than just monitoring?

A: To transition from a monitoring tool to a controller, reconfigure the output to regulate metabolic valves rather than reporters:

- Identify metabolic valves: Use computational tools like OptKnock to identify reactions that, when controlled, can switch metabolism from growth to production mode [14].

- Connect sensing to actuation: Replace the reporter gene (e.g., GFP) with genes encoding enzymes that control identified metabolic valves [14].

- Implement appropriate control logic: For toxic intermediates, use a repression system where the biosensor turns off competing pathways when intermediate levels become detrimental.

Performance Optimization

Q: My biosensor's dynamic range is insufficient for detecting physiologically relevant concentrations. How can I improve it?

A: Several strategies can enhance dynamic range:

- Tune expression levels: Systematically vary biosensor component expression using promoter libraries or ribosomal binding site (RBS) engineering.

- Employ signal amplification: Implement a transcriptional cascade where the primary biosensor controls a secondary amplifier circuit.

- Utilize protein design: For protein-based sensors, introduce mutations that stabilize "off" and "on" states to minimize leakiness and maximize response [28].

Q: How can I make my biosensor respond faster to fluctuating intermediate levels?

A: Response time depends on the sensing mechanism:

- For rapid response: Consider post-translational mechanisms like protein degradation tags or allosteric regulation, which operate faster than transcriptional cascades [28].

- Reduce metabolic burden: Ensure your biosensor circuit is genomically integrated rather than plasmid-based to improve stability and response characteristics.

- Consider host factors: Protein turnover rates significantly impact response time; this can be particularly advantageous in eukaryotic systems [28].

Experimental Protocols for Biosensor Development

Protocol: Developing a Transcription Factor-Based Biosensor

Objective: Engineer a TF-based biosensor for a toxic intermediate using a native or engineered transcription factor.

Materials:

- Host strain: Chassis organism (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) with deleted native pathways for the target intermediate

- Plasmids: Reporter plasmid with GFP/mCherry; expression vector for TF

- Chemicals: Pure standard of target intermediate; culture media components

Procedure:

- Identify candidate TF: Screen literature for TFs known to respond to your target or structurally similar compounds [28].

- Clone regulatory system: Amplify the TF gene and its cognate promoter, clone upstream of a fluorescent reporter gene.

- Characterize response: Transform into host strain, expose to varying concentrations of the target intermediate, and measure fluorescence output.

- Determine specifications: Calculate dynamic range, sensitivity, and specificity from dose-response curves.

- Engineering if needed: If performance is inadequate, employ directed evolution by:

- Creating mutant libraries of the TF via error-prone PCR

- Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to select variants with improved characteristics

- Iterating through multiple rounds of selection [28]

Protocol: Implementing Dynamic Control of a Metabolic Pathway

Objective: Integrate a validated biosensor into a metabolic pathway to dynamically regulate flux and prevent toxic intermediate accumulation.

Materials:

- Validated biosensor: From previous development work

- Metabolic pathway plasmids: Containing production pathway genes

- Analytical equipment: HPLC/GC-MS for metabolite quantification

Procedure:

- Identify control points: Determine which pathway enzymes contribute most to toxic intermediate accumulation (typically competing branch points) [14].

- Design control circuit: Configure the biosensor to repress/activate genes controlling the identified metabolic valves.

- Integrate system: Assemble the production pathway with the dynamic control circuit in your chassis organism.

- Test performance: Compare strains with static vs. dynamic control by measuring:

- Final titer of desired product

- Accumulation of toxic intermediate

- Cell growth and productivity

- Iterate optimization: Fine-tune system by adjusting promoter strengths, RBS sequences, or gene copy numbers to balance expression levels.

Data Presentation: Biosensor Performance Metrics

Table: Performance Characteristics of Representative Small Molecule Biosensors [28]

| Target Molecule | Sensing Element | Host/Chassis | Output Signal | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naringenin | FdeR transcription factor | S. cerevisiae | GFP | Screening and selection for optimal chassis |

| Malonyl-CoA | Type III polyketide synthase RppA | E. coli, P. putida, C. glutamicum | Flaviolin pigment | Screening and selection for optimal chassis |

| Lignin | EmrR transcriptional regulator | E. coli | GFP | Screening and selection for optimal chassis |

| Anthranilic acid | NahR regulatory protein | E. coli | tetA gene | Screening and selection for optimal system and chassis |

| Vanillate | Caulobacter crescentus VanR-VanO | E. coli | YFP | Screening and selection for optimal chassis |

| L-DOPA | DOPA dioxygenase (DOD) | S. cerevisiae | RFP | Monitoring and optimizing production |

Pathway Visualization and Workflows

Biosensor Architecture for Dynamic Pathway Control

Two-Stage Fermentation Strategy Using Biosensors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Proteins | GFP, mCherry, RFP, YFP [28] | Quantitative output signal for biosensor characterization | Choose based on host autofluorescence and detection equipment availability |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance genes, tetA [28] | Enrichment for productive sensor variants or pathway integration | Use different markers for sequential genetic modifications |

| Expression Systems | Inducible promoters (e.g., pTet, pBAD), constitutive promoters | Controlled expression of biosensor components | Match promoter strength to application needs; inducible systems useful for characterization |

| Host Chassis | E. coli, S. cerevisiae, P. putida, B. subtilis [28] | Cellular context for biosensor implementation | Choose based on pathway compatibility, growth characteristics, and genetic tractability |

| Molecular Tools | CRISPR-Cas systems, site-specific recombinases | Genome editing and pathway integration | Enable precise genetic modifications for stable strain construction |

| (4-Acetyl-2-methylphenoxy)acetonitrile | (4-Acetyl-2-methylphenoxy)acetonitrile | (4-Acetyl-2-methylphenoxy)acetonitrile is a nitrile building block for organic synthesis. This product is for research use only and not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| o-Chlorophenyl diphenyl phosphate | o-Chlorophenyl diphenyl phosphate, CAS:115-85-5, MF:C18H14ClO4P, MW:360.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the fundamental difference between an open-loop and a closed-loop control system?

An open-loop control system is a non-feedback system where the control action is independent of the system's output. It executes pre-programmed instructions without verifying whether the desired result has been achieved [30] [31].

A closed-loop control system, also known as a feedback control system, continuously monitors the system's output (e.g., metabolite concentration) and uses this information to adjust the control action. This feedback loop enables the system to correct deviations from the desired setpoint automatically [32] [33].

How do these control strategies apply to the dynamic control of metabolic pathways?

In metabolic engineering, controlling pathway dynamics is crucial for reducing the accumulation of toxic intermediates. An open-loop strategy might involve pre-programming the expression of a detoxification enzyme based on a timed schedule. A closed-loop strategy, conversely, would use a sensor to dynamically monitor the concentration of the toxic intermediate in real-time and regulate the expression of the detoxification enzyme in response [34] [35].

Comparative Analysis: A Framework for Selection

The choice between open-loop and closed-loop control depends on the specific requirements and constraints of your metabolic engineering project. The table below summarizes the key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Framework of Open-Loop and Closed-Loop Control Systems

| Basis of Difference | Open-Loop Control System | Closed-Loop Control System |

|---|---|---|

| Feedback Path | Not present [31] | Present [31] |

| Control Action | Independent of output [31] | Dependent on output [31] |

| Accuracy | Lower; relies on system calibration [30] [31] | Higher; feedback corrects errors [30] [31] |

| Disturbance Rejection | Poor; cannot compensate for unexpected changes [30] [33] | Excellent; can adapt to disturbances like nutrient shifts [32] [33] |

| Design & Complexity | Simple design and construction [30] [31] | More complex design [30] [31] |

| Cost & Maintenance | Less expensive and easier to maintain [30] [36] | Higher cost and maintenance requirements [30] [36] |

| Stability | Inherently stable as output does not affect control [30] | Can be less stable; requires careful tuning to avoid oscillations [32] [31] |

| Response Speed | Fast (no delay from feedback processing) [30] [31] | Slower (due to time required for sensing and processing) [31] |

| Example in Metabolism | Constitutive expression of a pathway enzyme [34] | Sensor-regulated expression of a transporter to export a toxic end-product [35] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: When should I prefer an open-loop control strategy in my metabolic experiments?

Open-loop control is suitable in the following scenarios:

- Highly Repetitive & Predictable Conditions: When your fermentation process is well-understood and operates under consistent, unchanging conditions with minimal external disturbances [36].

- Low-Cost & Simplicity is Key: During initial proof-of-concept experiments where simplicity, low cost, and ease of implementation are prioritized over high precision [30] [36].

- No Suitable Sensor Exists: When a real-time sensor for the key metabolite (e.g., a toxic intermediate) is not available or is prohibitively expensive.

FAQ: My closed-loop controlled bioreactor is oscillating. What could be the cause?

Oscillations or instability in a closed-loop system are often a tuning issue. The system may be over-correcting for small errors.

- Tuning Problem: The controller's response to an error (its gain) may be too aggressive. This is a common issue where the system's "gain" is improperly set for the dynamics of the biological process [32].

- Solution - System Tuning: Implement proper tuning of the control parameters. For a proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controller, this involves adjusting the proportional (KP), integral (KI), and derivative (K_D) terms to achieve a stable and responsive system. A poorly tuned controller can rapidly switch actuators (e.g., promoter activity) on and off, damaging the system [32] [33].

FAQ: My open-loop system fails to reduce toxic intermediate accumulation when cell density increases. Why?

This is a classic limitation of open-loop control.

- Lack of Feedback: Your open-loop system operates on a fixed program and cannot sense that the increased cell density has altered the metabolic network's dynamics, leading to higher levels of the toxic intermediate [30] [34].

- Solution - Implement Feedback: Transition to a closed-loop strategy. Introduce a biosensor that is specific to the toxic intermediate. The sensor's output can then be linked to a genetic circuit that dynamically upregulates a consuming enzyme or a transporter to export the toxin [35].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Closed-Loop Control for Toxin Reduction

Objective: To dynamically control the expression of a detoxification gene (e.g., a transporter protein) in response to the real-time concentration of a toxic metabolic intermediate.

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Methodology:

System Construction:

- Sensor Module: Clone a promoter that is naturally activated by the target toxic intermediate upstream of a reporter gene (e.g., GFP). Calibrate the fluorescence intensity against toxin concentration measured via LC-MS [37].

- Actuator Module: Place your detoxification gene (e.g., a transporter like ASTR for fatty alcohols [35]) under the control of a tunable, chemically inducible promoter (e.g., an L-rhamnose-inducible promoter).

- Strain Engineering: Integrate both modules into the production host (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae).

Controller Setup:

- Use a bioreactor equipped with an online fluorometer to measure GFP fluorescence (proxy for toxin level) in real-time.

- Connect the fluorometer output to a software-based controller (e.g., a custom Python script running a PID algorithm).

- The controller compares the measured toxin level to the desired setpoint and calculates an error signal.

- Based on the error, the controller sends a command to a pump to add a precise amount of the chemical inducer to the bioreactor, thereby regulating the detoxification gene [32] [33].

Operation and Data Collection:

- Initiate the production phase in the bioreactor.

- Activate the closed-loop control system.

- The system will continuously measure, compute, and actuate to maintain the toxic intermediate at the desired low concentration.

- Monitor and record the inducer concentration (control effort), toxin level, and final product titer over time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Dynamic Metabolic Control Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Promoters | Allows precise, external control of gene expression levels. | L-rhamnose-inducible promoter (for fine control); Tetracycline-inducible promoter [35]. |

| Metabolite Biosensors | Provides the feedback signal by detecting intracellular metabolite concentrations. | Transcription factor-based biosensors for intermediates like aldehydes or organic acids [35] [37]. |

| Reporter Proteins | Enables quantification of promoter activity or biosensor response. | GFP (for fluorescence); Luciferase (for luminescence) [37]. |

| Analytical Standards | Essential for calibrating biosensors and validating measurements. | Pure chemical standards of the target toxic intermediate and final product for LC-MS/MS [37]. |

| Specialized Growth Media | Provides defined conditions for consistent fermentation. | Minimal media with controlled carbon sources to minimize external disturbances [34]. |

| Benzo[f]naphtho[2,1-c]cinnoline | Benzo[f]naphtho[2,1-c]cinnoline | High-purity Benzo[f]naphtho[2,1-c]cinnoline for research applications. A polycyclic cinnoline for material science and pharmaceutical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 2,2,2-Trichloroethylene platinum(II) | 2,2,2-Trichloroethylene Platinum(II)|CAS 16405-35-9 | 2,2,2-Trichloroethylene Platinum(II) (Zeise's salt derivative) is for research, such as an electron-opaque microscopy marker. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Core Concepts and Methodology

Pathway-oriented screening is a live cell-based high-throughput screening (HTS) strategy designed to identify compounds that control specific metabolic pathways by monitoring the conversion of input to output metabolites. This approach is particularly valuable for dynamic control of metabolic pathways to reduce toxic intermediate accumulation, as it allows researchers to discover compounds that can modulate pathway flux in its native cellular environment [38].

This methodology addresses a critical challenge in metabolic engineering: the accumulation of toxic intermediates that can inhibit cellular fitness and limit production yields. By controlling metabolic flux, researchers can prevent the buildup of these harmful compounds while optimizing the production of valuable target molecules [39] [20].

Key Experimental Workflow

The fundamental workflow for pathway-oriented screening involves several carefully designed steps:

Define Input and Output Metabolites: Select a specific input metabolite that enters your target pathway and a corresponding output metabolite that serves as a reliable indicator of pathway activity [38].

Develop Extracellular Detection System: Implement a fluorogenic probe system that responds exclusively to extracellular metabolites, avoiding interference from intracellular components. The Q-dsAMC probe, which utilizes DT-diaphorase to detect NAD(P)H generated from output metabolites, represents an effective solution due to its high hydrophilicity that prevents cellular entry [38].

Establish Coupled Assay System: Incorporate microbial enzymes like d-lactate dehydrogenase to convert output metabolites (e.g., d-lactate) into detectable signals (NADH), ensuring orthogonality to similar cellular metabolites (e.g., l-lactate) with at least 100-fold selectivity [38].

Optimize Screening Conditions: Configure 384-well plate-based fluorometric assays with robust statistical parameters (Z' factor ≥ 0.69 indicates excellent assay quality) to enable high-throughput screening of compound libraries [38] [40].

Implement Triage Protocol: Apply sequential screening to eliminate false positives, including compounds that inhibit the detection system itself rather than the target pathway [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Signal Detection

Problem: Low fluorescence signal or poor signal-to-noise ratio in the screening assay.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient metabolic flux: Optimize input metabolite concentration to ensure sufficient output generation without causing cellular toxicity. Test a range of concentrations in pilot experiments [38].

- Probe sensitivity issues: Verify that the fluorogenic probe can detect ≥100 nM NADH. For the Q-dsAMC probe, confirm rapid reaction completion within 10 minutes [38].

- Detection enzyme selectivity: Validate that enzymes like d-lactate dehydrogenase show complete orthogonality toward your target output metabolite (e.g., >100x selectivity for d-lactate over l-lactate) [38].