Dynamic Control of Metabolism: Engineering Genetic Circuits for Precision Microbial Factories and Therapeutics

This article explores the implementation of genetic circuits for dynamic metabolic control, a cutting-edge approach in synthetic biology that moves beyond static engineering.

Dynamic Control of Metabolism: Engineering Genetic Circuits for Precision Microbial Factories and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article explores the implementation of genetic circuits for dynamic metabolic control, a cutting-edge approach in synthetic biology that moves beyond static engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive framework from foundational principles to advanced applications. We cover the expanding toolbox of regulatory devices, from biosensors to CRISPR-based systems, and detail methodologies for constructing circuits that autonomously balance cell growth and product synthesis. The article addresses critical challenges like circuit stability and predictability, highlighting innovative solutions such as phase-separated condensates. Finally, we present validation strategies and comparative analyses of real-world successes in bioproduction and gene therapy, offering a roadmap for the next generation of metabolic engineering and therapeutic interventions.

The Building Blocks of Control: Core Principles and Devices for Genetic Circuits

Genetic circuits are synthetic biological systems constructed from engineered networks of regulatory elements that program cells to perform predefined logical functions. Drawing inspiration from electronic circuit design, these circuits process molecular information through controlled gene expression, enabling cells to sense, compute, and respond to internal and external signals [1]. The implementation of these circuits is fundamental to advancing metabolic control research, providing the tools to dynamically rewire cellular metabolism for enhanced production of valuable chemicals, biofuels, and pharmaceuticals [2]. By moving beyond static metabolic engineering approaches, genetic circuits introduce temporal regulation, decision-making capabilities, and adaptive behaviors into microbial cell factories, thereby overcoming limitations posed by metabolic burden and evolutionary instability [3] [2].

Core Components and Regulatory Devices

Genetic circuits are built from modular regulatory devices that operate at different levels of the central dogma. These devices function as the fundamental building blocks for constructing complex circuitry [1].

- Devices Acting on DNA Sequence: Recombinase-based systems (e.g., Cre, Flp, FimB/FimE, serine integrases like Bxb1) implement permanent, inheritable changes by inverting or excising DNA segments. These are ideal for creating stable memory devices and bistable switches. CRISPR-Cas-derived devices, including base editors and prime editors, enable programmable DNA sequence modifications guided by RNA [1].

- Transcriptional Control Devices: These utilize transcription factors (both native and synthetic) and programmable DNA-binding domains (e.g., dCas9 fused to activator/repressor domains) to regulate transcription initiation. Orthogonal RNA polymerases and sigma factors can also be employed to create independent transcription channels [1].

- Post-Transcriptional and Translational Control Devices: This class includes riboswitches, toehold switches, and RNA interference (RNAi) mechanisms that control mRNA stability and accessibility to the ribosome. Small RNAs (sRNAs) can be used for efficient and low-burden post-transcriptional silencing, which has been shown to enhance the evolutionary longevity of circuits [3] [1].

- Post-Translational Control Devices: These regulate protein function through conditional degradation (e.g., degrons), controlled protein localization, or allosteric regulation of protein activity [1].

Table 1: Hierarchy of Regulatory Devices in Synthetic Biology

| Control Level | Regulatory Device Examples | Key Features and Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequence | Site-specific recombinases (Cre, Flp), Serine integrases (Bxb1), CRISPR-Cas base/prime editors | Permanent, inheritable changes; DNA inversion/excision; targeted nucleotide editing [1]. |

| Transcriptional | Synthetic transcription factors, dCas9-activators/repressors, Orthogonal RNA polymerases | Programmable DNA-binding; activation/repression of transcription; orthogonal gene expression [1]. |

| Post-Transcriptional | Riboswitches, Toehold switches, Small RNAs (sRNAs) | Ligand-dependent RNA structural changes; sequence-specific RNA-RNA interaction; low metabolic burden [3] [1]. |

| Post-Translational | Conditional protein degradation, Protein localization signals, Allosteric protein switches | Controlled protein stability; spatial control of protein activity; ligand-induced conformational changes [1]. |

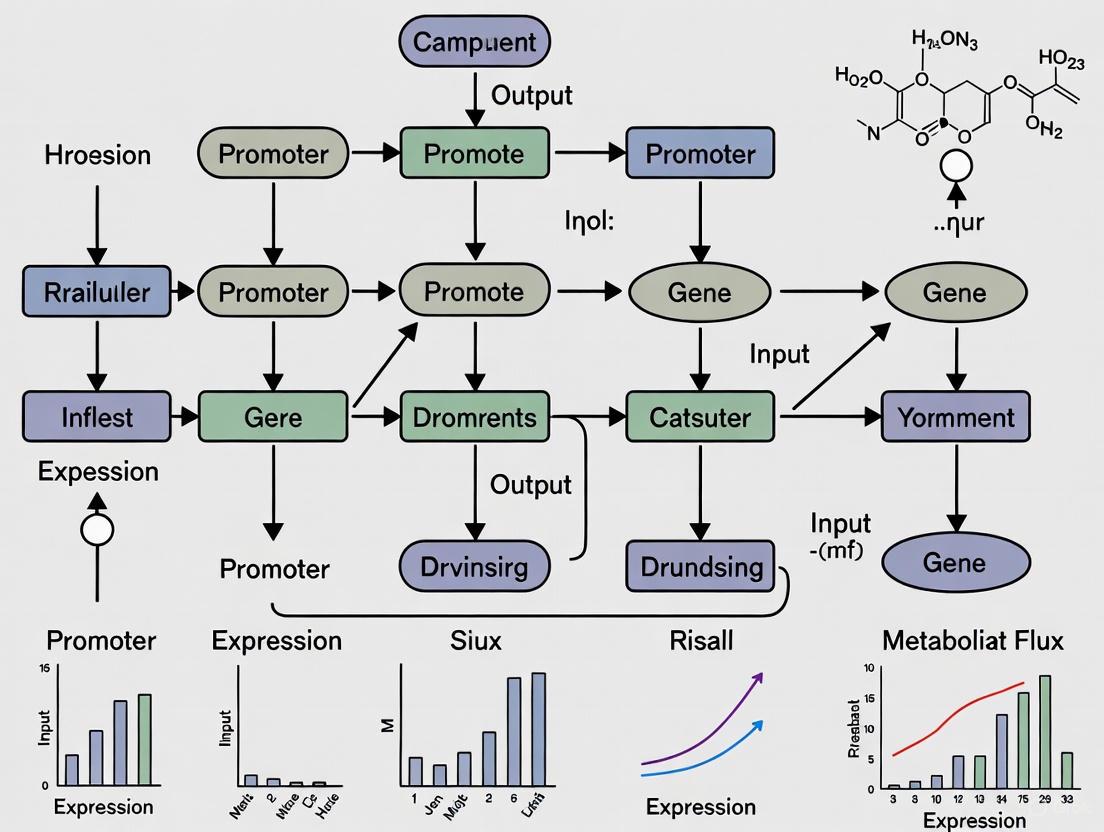

Figure 1: Information flow through different levels of regulatory control in a genetic circuit.

Quantitative Framework for Circuit Performance and Evolutionary Longevity

A critical challenge in genetic circuit implementation is maintaining function over time due to mutational burden and natural selection. Circuit-induced metabolic burden reduces host cell growth rates, creating a selective advantage for non-functional mutants, which eventually dominate the population [3]. A multi-scale "host-aware" computational framework that models host-circuit interactions, mutation, and population dynamics is essential for evaluating evolutionary stability [3].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Quantifying Evolutionary Longevity

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in Metabolic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Output (P0) | The total protein/output from the ancestral population before mutation. | Represents the maximum theoretical yield or metabolic flux at the start of a bioproduction process [3]. |

| Functional Stability (τ±10) | The time for the population-level output to fall outside the P0 ± 10% range. | Indicates the short-term reliability of a metabolic pathway for maintaining production within a narrow, optimal window [3]. |

| Functional Half-Life (Ï„50) | The time for the population-level output to fall below 50% of P0. | Measures the long-term "persistence" of a metabolic function, which may be sufficient for extended fermentation or biosensing applications [3]. |

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Genetic Controller Architectures

| Controller Architecture | Input Sensed | Actuation Method | Impact on Short-Term Stability (τ±10) | Impact on Long-Term Half-Life (τ50) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop | N/A | N/A | Baseline | Baseline | High initial output (P0) but rapid functional decline due to burden [3]. |

| Intra-Circuit Feedback | Circuit output per cell | Transcriptional | Prolongs performance | Moderate improvement | Negative autoregulation reduces burden but often lowers initial output [3]. |

| Growth-Based Feedback | Cellular growth rate | Post-transcriptional (sRNA) | Moderate improvement | Significantly extends half-life | Aligns circuit function with host fitness, outperforming intra-circuit feedback in the long term [3]. |

| Multi-Input Controllers | Combined inputs (e.g., output + growth rate) | Mixed (e.g., transcriptional + sRNA) | High improvement | High improvement (over 3x increase) | Biologically feasible designs that optimize both short- and long-term goals without coupling to essential genes [3]. |

Figure 2: The evolutionary degradation loop of synthetic gene circuits. Mutations that reduce circuit function and metabolic burden are selected for, leading to a loss of production over time.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Basic Genetic Circuit

This protocol outlines the key steps for constructing and testing a simple genetic circuit in E. coli, such as a toggle switch or an inducible expression system, within the context of metabolic engineering.

Circuit Design and In Silico Simulation

- Objective Definition: Clearly define the circuit's input-output relationship (e.g., "In the presence of inducer A, express gene B to divert metabolic flux").

- Part Selection: Choose well-characterized biological parts (promoters, RBS, coding sequences, terminators) from registries (e.g., iGEM parts registry). For metabolic control, consider promoters inducible by metabolic intermediates or stress responses.

- Host-Aware Modeling: Before synthesis, use a host-aware computational model [3] to simulate circuit behavior, predict metabolic burden, and estimate evolutionary longevity (P0, τ±10, τ50). This model should account for resource competition (ribosomes, nucleotides) between the host and the synthetic circuit.

DNA Construction and Assembly

- Vector Assembly: Assemble the genetic circuit into a suitable plasmid vector using standardized methods (e.g., Golden Gate Assembly, Gibson Assembly). Ensure the origin of replication and antibiotic resistance marker are compatible with the host strain.

- Component Integration: For metabolic pathway control, integrate the genetic circuit with the target metabolic genes on the plasmid or the host chromosome.

- Sequence Verification: Verify the final construct by Sanger sequencing or whole-plasmid sequencing to ensure the absence of mutations.

Cell Transformation and Culturing

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into an appropriate E. coli strain (e.g., DH10B for cloning, MG1655 for production) via chemical transformation or electroporation.

- Selection and Colony PCR: Plate transformed cells on LB agar with the appropriate antibiotic. Incubate overnight at 37°C. Pick several colonies and use colony PCR to confirm the presence of the correct insert.

- Liquid Culture Inoculation: Inoculate liquid LB medium with a positive colony and grow overnight.

Circuit Functionality Assay

- Induction and Sampling: Dilute the overnight culture in fresh, defined minimal medium (e.g., M9 with glucose). At the target optical density (OD600), add the inducer molecule. Take samples at regular intervals post-induction.

- Output Measurement:

- For Fluorescent Reporters: Measure fluorescence (e.g., GFP) and OD600 using a plate reader. Normalize fluorescence to OD600 to account for cell density.

- For Metabolic Outputs: Use HPLC or GC-MS to quantify the concentration of the target metabolite or product in the culture supernatant.

- Growth Kinetics: Continuously monitor OD600 to calculate growth rates and assess the metabolic burden imposed by the circuit.

Evolutionary Longevity Assay

- Serial Passaging: This assay directly measures the metrics in Table 2 [3].

- Day 1: Inoculate the engineered strain in fresh medium and grow for 24 hours under selective pressure (antibiotic) and, if applicable, inducing conditions.

- Daily Transfer: Every 24 hours, dilute the culture into fresh medium. Maintain this for tens of generations.

- Sampling and Storage: Sample and freeze cell stocks daily for later analysis.

- Population Output Tracking: At designated time points, use flow cytometry to measure the distribution of circuit output (e.g., fluorescence) across the population. For metabolic outputs, assay product titer from thawed samples.

- Data Analysis: Plot the population-level output over time to determine the functional stability (τ±10) and functional half-life (τ50) of the circuit [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Circuit Implementation

| Reagent / Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Engineered enzymes (e.g., Cre, Flp, Bxb1) that catalyze precise DNA recombination events. | Creating irreversible genetic switches or memory elements by inverting/excising DNA segments [1]. |

| Programmable CRISPR-effectors | dCas9 fused to transcriptional activator/repressor domains or base-editing enzymes. | Implementing complex logic or dynamic regulation of multiple metabolic genes simultaneously [1]. |

| Orthogonal RNA Polymerases | Bacteriophage-derived RNAPs (e.g., T7 RNAP) that transcribe only specific promoter sequences. | Creating independent transcription channels to minimize interference with host regulation [1]. |

| Small RNAs (sRNAs) | Engineered non-coding RNAs that silence target mRNAs through antisense binding. | Post-transcriptional regulation for low-burden, high-performance control to enhance evolutionary longevity [3]. |

| Inducer Molecules | Small molecules (e.g., IPTG, AHL, Anhydrotetracycline) that control inducible promoters. | Providing external, tunable control over the timing and level of circuit activation [1]. |

| Host-Aware Model Framework | A multi-scale computational model integrating host physiology, circuit function, and evolution. | In silico prediction of circuit burden, performance, and evolutionary longevity before experimental implementation [3]. |

| 3-(Benzimidazol-1-yl)propanal | 3-(Benzimidazol-1-yl)propanal, CAS:153893-09-5, MF:C10H10N2O, MW:174.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Aminopropanediamide | 2-Aminopropanediamide, CAS:62009-47-6, MF:C3H7N3O2, MW:117.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The precise control of cellular metabolism is a fundamental goal in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. Engineered genetic circuits function as the central processing units of the cell, enabling dynamic regulation of biosynthetic pathways for optimized production of valuable compounds. The efficacy of these circuits hinges on a sophisticated regulatory toolkit that operates across three hierarchical levels: transcriptional, translational, and post-translational control. Each level offers distinct advantages in response time, dynamic range, and regulatory precision, making them suitable for different metabolic engineering applications. This article provides application notes and detailed protocols for implementing these control devices, with particular emphasis on their integration into genetic circuits for advanced metabolic control research. The frameworks discussed here empower researchers to construct sophisticated genetic systems that can dynamically sense metabolic states and autonomously adjust flux distributions, thereby addressing fundamental challenges in metabolic engineering including metabolic imbalances, intermediate toxicity, and suboptimal yields.

Regulatory Device Classifications and Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Genetic Regulation Devices

| Control Level | Key Components | Response Time | Dynamic Range | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional | Transcription factors, promoters, synthetic transcription factors [4] [1] | Slow (hours) | Wide [4] | Pathway regulation, logic gates [5] [1] | High signal amplification, well-characterized parts [4] | Slow response, potential for host interference |

| Translational | Riboswitches, toehold switches, sRNAs [6] [1] | Moderate (minutes-hours) | Moderate to wide [6] | Fine-tuning expression, dynamic control [6] | Faster than transcriptional, avoid genomic integration [4] | Can require specialized RNA design |

| Post-Translational | PTM enzymes, proteolytic systems, allosteric regulators [7] [1] | Fast (seconds-minutes) | Variable | Protein activity modulation, metabolic engineering [7] | Rapid response, direct activity control [4] | Complex engineering, host machinery dependence |

Transcriptional Control Devices

Principles and Applications

Transcriptional control devices represent the most extensively utilized regulatory mechanism in synthetic biology, operating through the modulation of RNA polymerase recruitment to specific promoter sequences. These systems typically employ transcription factors (TFs) that bind small molecules, leading to conformational changes that either promote or inhibit transcription initiation. Natural transmembrane protein sensors can orchestrate transcription regulation by triggering intracellular signaling cascades that ultimately activate synthetic promoters. For instance, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) have been engineered to sense histamine levels or elevated bile acid levels, coupling detection to transcriptional responses through second messenger systems [4]. Similarly, light-sensitive GPCRs like human melanopsin have been rewired to activate nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT)-responsive promoters, enabling precise spatiotemporal control over transgene expression [4].

Designer transmembrane receptors offer enhanced orthogonality and programmability. The Tango system represents an advanced platform that combines natural or evolved sensing modules with synthetic protease-based signal transduction [4]. This system features a membrane receptor linked to a transcription factor through a tobacco etch virus protease (TEVp) cleavage site. Upon ligand binding, TEVp is recruited to the receptor, cleaving and releasing the transcription factor to migrate to the nucleus and activate target gene expression. The Modular Extracellular Sensor Architecture (MESA) platform further extends this concept through ligand-induced receptor dimerization, with one chain containing the transcription factor and the other the protease, enabling high fold-induction with minimal background [4].

Protocol: Implementing a Pyruvate-Responsive Transcriptional Biosensor

Background: This protocol describes the implementation of a pyruvate-responsive biosensor for dynamic control of central metabolism in E. coli, based on the PdhR transcription factor [5]. Pyruvate serves as a critical metabolic node connecting glycolysis to the TCA cycle, making it an ideal sentinel metabolite for regulating carbon distribution.

Materials:

- E. coli strain BW25113 containing F' from XL1-Blue [5]

- PdhR transcription factor from E. coli [5]

- EcPdhR-responsive promoter (EcPpdhR) [5]

- Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with appropriate antibiotics [5]

- Pyruvate standards for calibration

Procedure:

Circuit Assembly:

- Clone the pdhR gene under a constitutive promoter suitable for your application.

- Place your target metabolic genes downstream of the EcPdhR-responsive promoter (EcPpdhR).

- Transform the constructed plasmid into your production E. coli strain.

Biosensor Characterization:

- Inoculate transformed strains in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics and grow overnight.

- Dilute cultures to OD600 = 0.1 in fresh medium containing varying pyruvate concentrations (0-10 mM).

- Measure fluorescence output (if using reporter genes) or sample for transcript/protein analysis at regular intervals over 8-12 hours.

- Generate a calibration curve relating pyruvate concentration to output signal.

Metabolic Control Application:

- Cultivate engineered strains in production medium under appropriate conditions.

- Monitor pyruvate accumulation throughout the fermentation process.

- The biosensor will autonomously activate downstream metabolic pathways when pyruvate exceeds the threshold level, rebalancing carbon flux.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If background leakage is high, consider engineering PdhR for enhanced repression through directed evolution [5].

- If dynamic range is insufficient, optimize ribosomal binding sites or promoter variants.

- For in vivo applications, validate sensor performance under actual production conditions.

Translational Control Devices

Principles and Applications

Translational control devices regulate gene expression at the level of protein synthesis, offering faster response times than transcriptional control and the advantage of implementation without genomic integration [4]. These systems primarily operate by modulating the accessibility of ribosome binding sites (RBS) or through the action of regulatory RNAs. A key advantage of translational control is the ability to fine-tune gene expression levels without altering transcription rates, enabling precise optimization of metabolic fluxes.

Toehold switches represent particularly powerful translational control devices that operate through RNA-RNA interactions [6]. These synthetic RNA elements contain a ribosome binding site sequestered in a hairpin secondary structure, preventing translation initiation. Upon binding to a trigger RNA strand through complementary base pairing, the hairpin unfolds, exposing the RBS and enabling translation initiation. Toehold switches can achieve remarkable dynamic ranges of up to 400-fold and have been integrated into tunable expression systems that simultaneously control transcription and translation [6]. In such systems, the main transcriptional input controls toehold switch expression while a tuner sRNA input regulates its translational activity, enabling post-assembly fine-tuning of genetic devices [6].

Global translational control mechanisms also play crucial roles in metabolic engineering, particularly through the regulation of initiation factor availability and activity. Eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) represents a key control point, whose activity is modulated by 4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs) [8]. Under nutrient-rich conditions, signaling pathways such as mTOR phosphorylate 4E-BPs, preventing their interaction with eIF4E and promoting cap-dependent translation initiation. During nutrient stress, dephosphorylated 4E-BPs bind eIF4E and inhibit translation initiation, thereby conserving cellular energy and resources [8].

Protocol: Implementing a Tunable Expression System Using Toehold Switches

Background: This protocol describes the implementation of a tunable expression system (TES) that simultaneously controls transcription and translation using toehold switch technology [6]. This system enables dynamic adjustment of gene expression after circuit assembly, allowing researchers to correct for unexpected behavior or optimize performance without physical reconstruction.

Materials:

- Toehold switch (THS) variant 20 (or other selected variant) [6]

- Tuner sRNA complementary to the selected THS

- Ptet and Ptac promoters for input and tuner control, respectively [6]

- Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) or your gene of interest

- Anhydrotetracycline (aTc) and isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for induction

- Flow cytometry equipment for characterization

Procedure:

Circuit Construction:

- Clone your gene of interest downstream of the toehold switch sequence.

- Express the toehold switch from your selected input promoter (e.g., Ptet).

- Express the tuner sRNA from a separate tuner promoter (e.g., Ptac).

- Transform the constructed system into your host strain.

System Characterization:

- Grow transformed strains in medium with varying concentrations of aTc (0-100 ng/mL) and IPTG (0-1 mM).

- After 6-8 hours of induction, measure output using flow cytometry or other appropriate assays.

- For each tuner condition (IPTG concentration), plot the output against input promoter activity.

Performance Optimization:

- Identify the tuner setting that provides your desired dynamic range and absolute expression level.

- Evaluate the fold-change and distribution overlap between "on" and "off" states.

- If necessary, iterate on toehold switch design or RBS optimization to improve performance.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If background expression is too high, consider THS designs with more stable secondary structures.

- If induction fold-change is low, verify sRNA-THS complementarity and optimize sRNA expression levels.

- Be aware that high expression of both THS and sRNA may cause significant cellular burden.

Post-Translational Control Devices

Principles and Applications

Post-translational control devices directly modulate protein activity, stability, or localization, providing the fastest response times among regulatory mechanisms [4]. These systems are particularly valuable for implementing rapid feedback control in metabolic pathways, where immediate adjustment of enzyme activity is required to maintain metabolic homeostasis or prevent intermediate accumulation.

Protein degradation tags represent powerful post-translational control devices that enable precise regulation of protein half-life. These systems typically involve fusion of degradation tags (such as ssrA or other degrons) to target proteins, rendering them substrates for native or engineered cellular proteases like ClpXP or the proteasome [4]. The activity of these degradation systems can be further controlled using small molecule inducers that either stabilize the target protein or activate the protease machinery. For example, the SspB adaptor protein can be used to enhance ClpXP-mediated degradation of ssrA-tagged proteins, and its expression can be placed under inducible control for dynamic regulation [4].

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) including phosphorylation, acetylation, and glycosylation provide another rich landscape for engineering control devices. Recent advances in high-throughput screening methods have accelerated the engineering of PTM-installing enzymes. A notable example is the development of a cell-free gene expression (CFE) system coupled with AlphaLISA detection for characterizing and engineering oligosaccharyltransferases (OSTs) involved in protein glycan coupling [7]. This platform enables rapid screening of hundreds of enzyme variants and substrate combinations, identifying mutants with significantly improved glycosylation efficiency for therapeutic protein production [7].

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Post-Translational Modifications Using Cell-Free Expression and AlphaLISA

Background: This protocol describes a generalizable workflow for high-throughput characterization and engineering of post-translational modifications using cell-free gene expression (CFE) coupled with AlphaLISA detection [7]. This method is particularly useful for studying enzyme-substrate interactions in RiPPs (ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides) and glycoprotein engineering.

Materials:

- PUREfrex cell-free expression system [7]

- AlphaLISA detection beads (anti-FLAG donor beads and affinity-matched acceptor beads) [7]

- DNA templates encoding PTM enzymes and substrates

- FluoroTect GreenLys for labeling expressed proteins [7]

- 384- or 1,536-well microplates

- Acoustic liquid handling robot (optional but recommended)

Procedure:

Cell-Free Expression:

- Set up individual PUREfrex reactions expressing your PTM enzyme and substrate separately.

- For initial validation, include fluorescently labeled lysine to confirm protein expression.

- Incubate reactions at 32°C for 2-4 hours to allow protein synthesis.

AlphaLISA Detection:

- Combine enzyme- and substrate-expressing CFE reactions in detection plates.

- Add Anti-FLAG donor beads and anti-tag acceptor beads (e.g., anti-MBP if enzymes are MBP-tagged).

- Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Measure AlphaLISA signal using an appropriate plate reader.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize signals to appropriate controls (e.g., beads only, non-interacting protein pairs).

- Calculate binding affinities or enzymatic efficiencies from dose-response curves.

- For enzyme engineering, rank variants based on normalized activity signals.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If background signal is high, optimize bead concentrations and washing steps.

- If expression yields are low, supplement CFE reactions with additional energy sources or optimize DNA template concentrations.

- For quantitative measurements, include standard curves with purified components when possible.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Control Devices

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | PUREfrex [7] | High-throughput protein expression | Reconstituted translation machinery, low background |

| Detection Reagents | AlphaLISA beads [7] | Sensitive detection of molecular interactions | Bead-based proximity assay, 384- and 1,536-well format compatibility |

| Transcriptional Regulators | PdhR [5], TetR [6] | Metabolic sensing, inducible systems | Pyruvate-responsive, well-characterized dynamics |

| Translational Controllers | Toehold switches [6] | RNA-based regulation, tunable expression | High dynamic range (up to 400-fold), programmability |

| Post-Translational Tools | Oligosaccharyltransferases (OSTs) [7] | Protein glycosylation studies | Glycan diversity, therapeutic protein engineering |

| Genetic Circuit Hosts | E. coli BW25113 [5] | Metabolic engineering chassis | Well-characterized metabolism, extensive toolkit available |

| Inducing Molecules | aTc, IPTG [6] | Chemical induction of genetic circuits | Non-metabolizable, high membrane permeability |

Regulatory Pathway Integration and Circuit Design

The true power of genetic control devices emerges from their integration into coordinated regulatory circuits. Multi-level control strategies that combine transcriptional, translational, and post-translational regulation can achieve sophisticated dynamic behaviors that are impossible with single-level control. For instance, a circuit might employ transcriptional control for coarse pathway regulation, translational control for fine-tuning enzyme expression levels, and post-translational control for rapid metabolic feedback.

Multi-Level Regulatory Circuit for Metabolic Control

Advanced circuit architectures incorporate feedback controllers to enhance evolutionary longevity and functional stability. Recent computational studies have identified design principles for genetic controllers that maintain synthetic gene expression despite mutational pressure and selection [3]. Post-transcriptional controllers using small RNAs generally outperform transcriptional controllers, and growth-based feedback extends functional half-life more effectively than output-based feedback alone [3]. The most robust designs incorporate multiple input signals and actuation mechanisms to create circuits that maintain function over extended periods.

High-Throughput Device Characterization Workflow

The synthetic biology toolkit for transcriptional, translational, and post-translational control has matured significantly, providing researchers with an extensive arsenal of regulatory devices for metabolic engineering. The protocols and application notes presented here offer practical guidance for implementing these systems, with emphasis on quantitative characterization and integration into functional genetic circuits. As the field advances, the development of increasingly sophisticated multi-level control systems and high-throughput engineering methodologies will further expand our ability to reprogram cellular metabolism for biomedical and industrial applications. Researchers are encouraged to consider the unique advantages and limitations of each regulatory level when designing genetic circuits for specific metabolic control objectives, and to leverage the growing repository of standardized genetic parts and design principles to accelerate their engineering cycles.

Metabolic regulation is a dynamic process integral to cellular function, and its dysregulation is a hallmark of numerous diseases, including neurodegenerative conditions and cancer [9] [10]. Traditional metabolic analysis techniques, such as mass spectrometry or immunostaining, often provide only static, endpoint data and fail to capture the rapid, subcellular fluctuations of metabolites that drive cellular decisions [9]. The implementation of genetically encoded biosensors addresses this critical gap, offering researchers the ability to monitor metabolic fluxes in living cells with high spatial and temporal resolution [9] [11]. This Application Note details the use of these biosensors as foundational tools within genetic circuits for metabolic control research, providing standardized protocols for studying key metabolites like pyruvate, ATP/ADP, and NAD(H), and visualizing their dynamics in real-time.

Quantitative Landscape of Genetically Encoded Metabolic Biosensors

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of widely used biosensors for central metabolites, enabling informed selection for experimental design.

Table 1: Key Genetically Encoded Biosensors for Metabolic Monitoring

| Target Analyte | Biosensor Name | Sensing Mechanism | Dynamic Range / Kd / ECâ‚…â‚€ | Key Applications & Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP | ATeam (e.g., 1.03YEMK) | FRET | Kd ~7.4 µM to 3.3 mM; ~150% dynamic range [9] | Measures resting ATP levels; used in Drosophila neurodegeneration models and diabetic neuropathy studies [9]. |

| iATPSnFR | Single-wavelength intensity | EC₅₀ ~50-120 µM; ~2-fold dynamic range [9] | Detects ATP at cell surfaces; reveals metabolic heterogeneity at single-synapse resolution [9]. | |

| MaLion (G/R/B) | Single-wavelength intensity (multicolor) | Kd: MaLionR 0.34 mM, MaLionG 1.1 mM, MaLionB 0.46 mM [9] | Simultaneous multi-compartment imaging; used to study postsynaptic ATP levels regulated by mitochondrial CREB signaling [9]. | |

| ATP/ADP Ratio | PercevalHR | Single-wavelength intensity | KR ~3.5; 5-fold greater dynamic range than Perceval [9] | Matches physiological ratios; applied in axon regeneration and neuroinflammatory disease models (e.g., multiple sclerosis) [9]. |

| Pyruvate | PyronicSF | Single-wavelength (cpGFP) | N/A | Real-time subcellular quantitation of pyruvate in neurons and developing embryos (e.g., sea urchin) [10]. |

| PdhR-based Biosensor | Transcriptional / FRET | N/A | Engineered for dynamic regulation in E. coli; used in genetic circuits for central metabolism control [5] [12]. | |

| NAD(H) | iNAP | Single-wavelength intensity | Various affinities available [12] | Measures NADPH in cytosol/mitochondria; revealed NADPH metabolism regulation by glucose in cancer cells [12]. |

| Redox Potential | Grx1-roGFP2 | Ratiometric (Excitation) | N/A | Reflects glutathione redox potential, reporting on TCA cycle and OxPhos activity [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Metabolic Biosensor Implementation

Protocol 1: Monitoring Pyruvate Dynamics with PyronicSF in a Developing Embryo Model

This protocol outlines the procedure for visualizing spatiotemporal pyruvate dynamics during sea urchin embryogenesis, a model for studying metabolic regulation in development [10].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Animals: Adult sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus).

- Constructs: pCS2+ vector containing the PyronicSF ORF.

- Key Reagents: Filtered seawater (0.22 µm), 3-amino triazole, FLAG-tag mRNA for lineage tracing.

- Equipment: Microinjection system, fluorescence microscope with time-lapse capability, temperature-controlled stage (16°C).

Methodology:

- Gamete Collection & Fertilization: Induce spawning in adult sea urchins via intracoelomic injection of 0.5 M KCl. Collect eggs and sperm. Fertilize eggs in seawater containing 1 mM 3-amino triazole to prevent hardening of the fertilization envelope [10].

- Microinjection: Dechorionate fertilized eggs and microinject with an injection mixture containing:

- ~500 ng/µL of the PyronicSF-pCS2+ plasmid.

- Tracer mRNA (e.g., FLAG-tag) at 50-100 ng/µL to identify successfully injected cells [10].

- Embryo Culture & Imaging: Culture injected embryos at 16°C in filtered seawater. Mount embryos at the desired developmental stage for live imaging. Perform time-lapse fluorescence imaging using standard GFP filter sets.

- Data Analysis: Quantify fluorescence intensity over time and across different cell lineages. Normalize signals to baseline levels. The asymmetric signal enrichment at the 16-cell stage and in the apical plate during gastrulation indicates spatially dynamic pyruvate metabolism [10].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Pyruvate-Responsive Genetic Circuit in E. coli

This protocol describes the application of an engineered PdhR-based biosensor for dynamic control of central metabolism in E. coli, a cornerstone strategy for metabolic engineering [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli BW25113.

- Genetic Circuit: Plasmid(s) containing the engineered PdhR transcription factor and its cognate promoter (EcPpdhR) controlling a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) and/or a pathway enzyme [5].

- Growth Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or defined M9 minimal medium with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin at 100 µg/mL).

- Inducer: Pyruvate (sodium salt), prepared as a sterile stock solution.

Methodology:

- Circuit Characterization: Transform the PdhR-biosensor plasmid into E. coli. Grow cultures in the presence of varying pyruvate concentrations (e.g., 0 - 10 mM).

- Flow Cytometry & Analytics: Measure the fluorescence output (GFP) via flow cytometry to assess the biosensor's dynamic range and sensitivity. Quantify metabolic intermediates and products using HPLC or GC-MS to correlate sensor output with pathway flux [5].

- Application in Dynamic Regulation: For production strains (e.g., for trehalose or 4-hydroxycoumarin), the PdhR-responsive promoter can be used to dynamically control the expression of key pathway enzymes. In this "closed-loop" control, accumulating pyruvate automatically upregulates or downregulates pathway expression to optimize flux and minimize metabolic burden [5].

- Validation: Compare product titers, yields, and overall culture stability between strains with static (constitutive) and dynamic (biosensor-controlled) regulation.

Visualizing Biosensor Workflows and Metabolic Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows for implementing metabolic biosensors.

Biosensor-Enabled Metabolic Engineering Workflow

Diagram Title: Biosensor-Driven DBTL Cycle in Metabolic Engineering

Pyruvate Metabolic Node and Biosensor Sensing

Diagram Title: Pyruvate as a Central Node for Biosensor Interrogation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Biosensor Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ATeam1.03YEMK | FRET-based biosensor for quantifying intracellular ATP levels. | Monitoring ATP deficits in retinal ganglion cells in glaucoma models [9]. |

| PercevalHR | Ratiometric biosensor for monitoring ATP/ADP ratio. | Assessing energy status in dystrophic axons in neuroinflammatory disease [9]. |

| PyronicSF | cpGFP-based biosensor for real-time pyruvate imaging. | Visualizing glycolytic activity gradients during sea urchin embryogenesis [10]. |

| Engineered PdhR System | Transcription factor-based biosensor for pyruvate. | Dynamic control of central carbon metabolism in bacterial cell factories [5]. |

| Grx1-roGFP2 | Ratiometric biosensor for glutathione redox potential. | Reporting on OxPhos activity in developing embryos and other models [10]. |

| MaLion Series (R/G/B) | Spectrally diverse, single-wavelength ATP biosensors. | Simultaneous monitoring of ATP in different cellular compartments [9]. |

| Lithium pyrrolidinoborohydride 1M solu | Lithium pyrrolidinoborohydride 1M solu, CAS:144188-76-1, MF:C4H8BLiN, MW:87.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tris-(4-chlorophenyl)-sulfonium bromide | Tris-(4-chlorophenyl)-sulfonium bromide, CAS:125428-43-5, MF:C18H12BrCl3S, MW:446.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The implementation of sophisticated genetic circuits for metabolic control hinges on three fundamental functional classes: logic gates, bistable switches, and feedback loops. These components enable engineered cells to perform complex computations, maintain stable phenotypic states, and dynamically regulate metabolic flux in response to changing intracellular and extracellular conditions. Logic gates provide the foundational Boolean operations (AND, OR, NOT, etc.) that allow circuits to process multiple input signals and make discrete decisions. Bistable switches introduce memory and hysteresis, enabling cells to latch into persistent metabolic states—such as growth versus production phases—based on transient stimuli. Feedback loops, both negative and positive, provide essential dynamic control capabilities that enhance circuit robustness, maintain homeostasis, and improve evolutionary longevity by automatically adjusting gene expression in response to metabolic burden or pathway intermediates. Together, these circuit functions form the core framework for building programmable metabolic control systems that can optimize titer, rate, and yield (TRY) metrics in industrial biotechnology and therapeutic applications.

Table 1: Core Circuit Functions and Their Roles in Metabolic Control

| Circuit Function | Key Operational Principle | Primary Role in Metabolic Control | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logic Gates | Perform Boolean operations on input signals | Enable conditional, multi-input regulation of metabolic pathways | Resource-triggered production; pathogen-specific drug activation |

| Bistable Switches | Maintain two stable steady states with hysteresis | Decouple growth and production phases; implement metabolic memory | Two-stage fermentations; bet-hedging population strategies |

| Feedback Loops | Adjust output based on measured system state | Maintain homeostasis; reduce metabolic burden; extend functional longevity | Burden compensation; product toxicity mitigation; flux balancing |

Logic Gates: Programmable Decision-Making

Genetic logic gates are molecular devices that process one or more input signals to produce a specific output according to Boolean logic principles. These gates form the computational foundation of genetic circuits, allowing engineers to program precise conditionality into metabolic control systems. In practice, logic gates can be constructed using various molecular mechanisms, including transcriptional regulators, site-specific recombinases, and CRISPR-based systems.

Design and Implementation Platforms

The implementation of logic gates has been demonstrated across multiple technological platforms. Recombinase-based systems utilize enzymes such as Flp, Bxb1, and PhiC31 integrases to perform permanent DNA rearrangements that implement logic functions. For example, the BLADE (Boolean Logic and Arithmetic through DNA Excision) platform has successfully implemented 16 different Boolean logic gates in human cells by strategically positioning recombinase sites and their recognition sequences [13]. DNA-binding protein systems employ synthetic transcription factors based on designable DNA-binding domains (e.g., TALEs, zinc fingers) fused to transcriptional activation or repression domains. These systems can be configured to create logic gates by placing appropriate binding sites in promoter regions. CRISPR-based systems offer particularly versatile logic gate implementation by using guide RNAs (sgRNAs) as programmable inputs that direct catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to effector domains to target promoters. A simple NOR gate, for instance, can be constructed using two distinct sgRNAs as inputs that repress output gene expression when either or both are present [1] [13].

Application in Metabolic Control

Logic gates enable sophisticated metabolic control strategies that respond to multiple intracellular conditions. An AND gate might require both low nutrient availability and high cell density before activating a biosynthetic pathway, preventing premature production that could hinder growth. An A NIMPLY B gate could trigger stress response pathways only when nutrient limitation is present without concomitant oxygen saturation. These multi-input decision-making capabilities allow metabolic engineers to create circuits that activate production pathways only under optimal conditions, significantly improving production metrics and reducing metabolic burden during growth phases.

Figure 1: Fundamental Boolean Logic Gates. Genetic circuits implement Boolean operations where biological inputs (e.g., metabolites, transcription factors) are processed to produce specific outputs according to logical rules.

Bistable Switches: Metabolic Memory and State Control

Bistable switches are genetic circuits that can exist in two alternative stable states, enabling long-term cellular memory and abrupt transitions between distinct metabolic phenotypes. This bistability arises from positive feedback loops within genetic regulatory networks that create a hysteresis effect, where the system maintains its current state even after the initial inducing signal is removed. The ability to lock cells into specific metabolic states makes bistable switches particularly valuable for implementing two-stage bioprocesses where growth and production phases are temporally separated.

Architectural Requirements for Bistability

Successful engineering of bistable switches requires specific network architectures that generate sufficient nonlinearity to create two distinct steady states. Natural bistable systems often employ mutual repression (toggle switch) or auto-activation architectures. The classic genetic toggle switch consists of two repressors that mutually inhibit each other's expression. However, when using monomeric DNA-binding domains like TALEs or CRISPR-based systems, additional design elements must be incorporated to introduce the necessary nonlinearity. One effective approach combines positive feedback loops with competition between activators and repressors for the same DNA binding sites. This architecture was successfully implemented using TALE-based transcription factors, where competition between TALE activators and TALE repressors for the same operator sites created the required nonlinear response for robust bistability [14].

Uptake Switches for Metabolic Control

A particularly valuable application of bistable switches in metabolic engineering is the control of metabolite uptake. Bistable uptake switches enable cells to toggle between slow and fast uptake states in response to extracellular metabolite concentrations. Through mathematical modeling, the activation-repression (AR) circuit architecture has been identified as particularly robust for this function. In this design, an intracellular metabolite activates expression of a transport enzyme while repressing expression of a utilization enzyme, or vice versa. This architecture generates bistability across a large range of promoter dynamic ranges and requires minimal parameter fine-tuning [15]. Such uptake switches can coordinate metabolic tasks in microbial consortia, allocate metabolic functions between different strains, and implement bet-hedging strategies where subpopulations specialize in different nutritional niches.

Table 2: Bistable Switch Architectures and Their Properties

| Architecture | Network Topology | Nonlinearity Source | Implementation Challenges | Metabolic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toggle Switch | Mutual repression between two transcription factors | Cooperative DNA binding (dimers/oligomers) | Requires cooperative binding; limited orthogonal parts | Two-stage fermentations; phenotype differentiation |

| Positive Feedback Loop | Self-activation of transcription factor | Concentration-dependent autoactivation | Potential leakiness; difficult to reset | Metabolic state locking; bet-hedging strategies |

| Activator-Repressor Competition | Competing activator and repressor share binding sites | Competition for operator site occupancy | Balancing expression levels of competing elements | Uptake control; nutrient specialization |

| Natural System-inspired | Coupled genetic-metabolic feedback | Ultrasensitive enzyme kinetics | Interface between genetic and metabolic networks | Carbon source switching; pathway activation |

Figure 2: Bistable Switch Operation. Bistable switches maintain one of two stable states through mutual repression and positive feedback, enabling persistent metabolic states even after the initial signal disappears.

Feedback Loops: Dynamic Regulation and Robustness

Feedback loops are fundamental control elements that enable genetic circuits to dynamically regulate their behavior in response to changes in the intracellular environment. In metabolic engineering, feedback control is particularly valuable for maintaining homeostasis, reducing metabolic burden, and extending the functional longevity of engineered circuits. Feedback systems operate by monitoring specific cellular parameters (e.g., metabolite concentrations, growth rate, resource availability) and adjusting metabolic pathway expression accordingly.

Negative Feedback for Burden Control and Longevity

Negative feedback loops improve circuit robustness and longevity by counteracting deviations from desired operating points. In metabolic engineering, negative feedback can be employed to reduce the fitness burden imposed by heterologous pathway expression, thereby slowing the emergence of non-productive mutant strains that outcompete engineered cells. Implementation strategies include:

- Growth rate-coupled feedback: Controller circuits that downregulate metabolic pathway expression when growth rate decreases due to metabolic burden.

- Resource-based feedback: Systems that monitor the availability of key cellular resources (e.g., ribosomes, ATP, amino acids) and adjust heterologous gene expression to maintain resource homeostasis.

- Product-sensing feedback: Circuits that use biosensors to detect metabolite accumulation and regulate pathway flux to prevent toxic buildup.

Computational models comparing controller architectures have demonstrated that post-transcriptional control using small RNAs (sRNAs) generally outperforms transcriptional control for burden mitigation. The amplification inherent in sRNA-mediated regulation enables strong control with reduced controller burden. Furthermore, growth-based feedback significantly extends long-term circuit performance, while intra-circuit feedback improves short-term stability [3].

Positive Feedback for Signal Amplification and Commitment

Positive feedback loops amplify signals and drive commitment to cellular decisions by reinforcing specific metabolic states. In naturally occurring systems, positive feedback often works in conjunction with negative feedback to create sophisticated control systems. For example, in the Xenopus oocyte maturation pathway, a positive-feedback-based bistable module consisting of p42 MAPK and Cdc2 enables the system to maintain irreversibility of maturation following transient inductive stimulus [16]. In synthetic metabolic engineering, positive feedback can be employed to lock pathways into high-expression states once specific metabolite thresholds are reached, creating digital-like responses to analog metabolic signals.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementation and Characterization of a Bistable Uptake Switch

This protocol describes the implementation of an activation-repression (AR) circuit architecture for controlling metabolite uptake rates in Escherichia coli, based on mathematical design principles that maximize robustness to parameter variation [15].

Materials and Reagents

- E. coli strain with deleted native uptake systems for target metabolite

- Plasmid system with inducible promoters responsive to intracellular metabolite

- Fluorescent reporters for monitoring expression dynamics (e.g., GFP, mCherry)

- Metabolite analogs for controlled induction (e.g., TMG for lac operon studies)

- Microfluidic cultivation device for single-cell microscopy

- Flow cytometer for population-level analysis

Procedure

Circuit Construction

- Clone transport enzyme (e.g., lactose permease) under control of metabolite-activated promoter

- Clone utilization enzyme (e.g., β-galactosidase) under control of metabolite-repressed promoter

- Incorporate fluorescent protein genes fused to each enzyme via cleavable peptide linkers (e.g., t2A) for expression monitoring

- Transform construct into appropriate E. coli host strain

Characterization in Batch Culture

- Grow engineered cells in minimal medium with alternating carbon sources (glucose vs. target metabolite)

- Measure population-level metabolite uptake rates using extracellular metabolite sensors

- Sample at regular intervals for flow cytometry to assess population heterogeneity

- Determine steady-state enzyme expression levels via Western blotting

Single-Cell Dynamics Analysis

- Load cells into microfluidic cultivation device with controlled metabolite switching

- Image cells every 10-15 minutes for 12-24 hours using time-lapse microscopy

- Quantify fluorescence intensities for each reporter over time

- Analyze correlation between metabolite pulses and expression switching

Hysteresis Quantification

- Expose cells to gradually increasing metabolite concentrations (0 → 10 mM)

- After saturation, gradually decrease metabolite concentrations (10 → 0 mM)

- Measure uptake rates and reporter expression at each concentration

- Plot dose-response curves for both increasing and decreasing directions

- Calculate hysteresis area as the difference between switching thresholds

Model Fitting and Validation

- Parameterize mathematical model using single-cell expression data

- Validate model predictions by testing under novel input conditions

- Iteratively refine promoter strengths to optimize switching characteristics

Data Analysis

- Bistability confirmation: Hysteresis in dose-response curves and bimodal expression distributions

- Switching kinetics: Time delay between metabolite pulse and complete state transition

- Stability assessment: Duration of state maintenance after signal removal

Protocol: Implementing CRISPRi-Based NOR Gate Logic in Plant Systems

This protocol adapts CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) technology for implementing Boolean NOR logic in plant systems, enabling sophisticated transcriptional control with minimal metabolic burden [13].

Materials and Reagents

- Plant expression vectors with cell type-specific and inducible promoters

- dCas9-KRAB repression domain fusion construct

- sgRNA expression cassettes with Pol III promoters

- Reporter construct with target sgRNA binding sites in promoter region

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains for plant transformation

- Chemical inducers for input signal control (e.g., dexamethasone, estradiol)

Procedure

Circuit Design and Assembly

- Design two sgRNA target sequences complementary to promoter regions of output gene

- Clone dCas9-KRAB repressor under constitutive promoter

- Assemble sgRNA expression cassettes under control of input-responsive promoters

- Construct output reporter (e.g., YFP) with promoter containing both sgRNA target sites

- Verify component orthogonality and absence of cross-talk

Plant Transformation and Selection

- Introduce constructs into Arabidopsis thaliana via floral dip transformation

- Select transformants on antibiotic-containing media

- Verify transgene integration via PCR and Southern blotting

- Isolate homozygous T3 lines for characterization

Logic Function Validation

- Apply input inducer chemicals in all four possible combinations (+/+, +/-, -/+, -/-)

- Measure output reporter expression after 24-48 hours using fluorescence microscopy

- Quantify expression levels via qRT-PCR for transcript quantification

- Confirm NOR function (expression only in absence of both inputs)

Performance Characterization

- Measure response time by monitoring output after input application/removal

- Determine dynamic range by comparing ON and OFF state expression levels

- Assess leakiness in all input conditions

- Test logic function in different cell types and developmental stages

Application to Metabolic Pathway Control

- Replace reporter gene with metabolic enzyme or transcription factor

- Measure metabolic flux changes under different input conditions

- Assess impact on target metabolite production

Data Analysis

- Logic fidelity: Quantitative assessment of truth table compliance

- Dynamic range: Ratio of ON-state to OFF-state expression

- Temporal response: Kinetics of state transitions after input changes

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Circuit Construction

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Circuit Implementation | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programmable DNA-Binding Domains | TALE proteins, dCas9, Zinc Fingers | Provide target specificity for transcriptional regulators | Modular design; orthogonal target sequences; tunable affinity |

| Transcriptional Effector Domains | VP16 (activation), KRAB (repression), SRDX (plant repression) | Determine regulatory function at target promoters | Strong activation/repression; minimal collateral effects |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | Cre, Flp, Bxb1, PhiC31 | Enable permanent DNA rearrangements for memory circuits | High efficiency; unidirectional or bidirectional; orthogonal recognition sites |

| Small Molecule Sensors | TetR, LuxR, AraC, steroid receptors | Provide input detection for chemical signals | High sensitivity; low basal activity; tunable dynamic range |

| Fluorescent Reporters | GFP, YFP, RFP, BFP, luciferase | Enable quantitative circuit characterization | Brightness; photostability; spectral orthogonality; minimal metabolic burden |

| Ribosome Binding Site Libraries | Varying strength RBS sequences | Fine-tune translation efficiency for expression balancing | Predictable translation initiation rates; minimal secondary structure |

| Promoter Libraries | Constitutive, inducible, tissue-specific | Provide transcriptional control elements with varying strengths | Defined dynamic range; low noise; minimal cross-talk |

Integrated Circuit Design for Metabolic Control

The most effective metabolic control systems integrate multiple circuit functions to achieve sophisticated regulatory capabilities. For example, a two-stage bioprocess for high-value metabolite production might combine:

- Logic gates to sense multiple environmental conditions (nutrient status, cell density, dissolved oxygen)

- A bistable switch to irreversibly transition from growth phase to production phase

- Negative feedback loops to maintain optimal precursor metabolite pools during production

- Positive feedback to lock in the production state once initiated

Such integrated designs leverage the strengths of each circuit type while mitigating their individual limitations. The hysteresis of bistable switches prevents unwanted toggling between states due to minor environmental fluctuations, while feedback loops ensure homeostatic maintenance of metabolic intermediates at optimal levels. Logic gates provide the conditional decision-making that ensures state transitions occur only under appropriate environmental conditions.

Future advances in genetic circuit design for metabolic control will focus on improving orthogonality to reduce context-dependence, developing more precise mathematical models to predict circuit behavior, and creating adaptive circuits that can adjust their parameters based on long-term performance metrics. As these technologies mature, they will enable increasingly sophisticated metabolic engineering strategies that dynamically optimize pathway flux in response to real-time metabolic demands.

A fundamental challenge in constructing efficient microbial cell factories is the inherent trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis. Conventional static metabolic engineering methods, such as gene knockouts and constitutive overexpression, often lead to metabolic imbalances, accumulation of toxic intermediates, and reduced cellular viability [5]. These limitations arise because essential cellular processes and the engineered biosynthetic pathways compete for the same carbon and energy resources, creating a tension that limits overall production efficiency.

Dynamic regulation strategies offer a sophisticated solution to this problem by utilizing biosensor-based genetic circuits that respond to intracellular metabolite levels, enabling autonomous and real-time adjustment of metabolic pathways [5]. Unlike static methods, these systems can sense metabolic states and dynamically re-route fluxes, thereby minimizing burdens on host cells while maximizing product yield. This approach is particularly valuable in central metabolism, where multiple competing pathways—such as glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway, and shikimate pathway—divert key intermediates away from target compound production [5].

Genetic Circuit Architectures for Dynamic Control

Circuit Design Principles and Regulatory Mechanisms

Genetic circuits for dynamic metabolic control function as feedback systems that monitor intracellular conditions and adjust gene expression accordingly. These systems typically incorporate sensing elements, signal processing modules, and output components to create closed-loop control networks. The most effective controllers utilize negative feedback to maintain system performance despite perturbations and evolutionary pressures [3].

Controllers can be categorized by their input sensing strategies and actuation mechanisms:

- Intra-circuit feedback monitors the output of the synthetic pathway itself

- Growth-based feedback responds to changes in cellular growth rates

- Population-based feedback utilizes quorum-sensing mechanisms

In terms of actuation, post-transcriptional control using small RNAs (sRNAs) generally outperforms transcriptional control via transcription factors, as sRNA mechanisms provide signal amplification with reduced cellular burden [3].

Table 1: Genetic Circuit Architectures for Dynamic Regulation

| Controller Type | Sensing Input | Actuation Mechanism | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor-Based | Specific metabolites | Transcriptional regulation | High specificity, modular design | Limited dynamic range, resource intensive |

| sRNA-Based | Intracellular metabolites | Post-transcriptional silencing | Fast response, low burden | Requires careful tuning |

| Quorum Sensing-Based | Cell density | Cell-to-cell communication | Population-level control | Not metabolite-specific |

| Growth-Based | Cellular growth rate | Regulation of essential processes | Extends functional half-life | Indirect coupling to production |

Enhancing Evolutionary Longevity

A critical limitation of engineered gene circuits is their tendency to degrade due to mutation and selection pressure. Circuits that impose significant * metabolic burden* create selective advantages for mutant cells with impaired function, leading to population-wide loss of production capability over time [3]. The evolutionary longevity of a circuit can be quantified by measuring the time taken for population-level output to fall by 50% (τ50) or outside a 10% performance window (τ±10) [3].

Advanced controller designs address this challenge through several strategies:

- Negative autoregulation prolongs short-term performance by reducing expression noise and burden

- Growth-based feedback extends functional half-life by linking circuit function to fitness

- Multi-input controllers combine sensing strategies to improve robustness

Computational modeling reveals that post-transcriptional controllers generally outperform transcriptional ones, and systems with separate circuit and controller genes show enhanced performance due to evolutionary trajectories where controller loss temporarily increases production [3].

Application Note: A Pyruvate-Responsive Biosensor for Central Metabolism

System Development and Characterization

The transcription factor PdhR from Escherichia coli (EcPdhR) provides an effective foundation for constructing dynamic controllers for central metabolism. EcPdhR naturally functions as a * transcriptional repressor* that binds to the -10 region of the EcPpdhR promoter, preventing RNA polymerase recruitment in the absence of its ligand, pyruvate [5]. When pyruvate accumulates, it binds to PdhR, causing a conformational change that releases the repressor from the promoter and enables transcription initiation.

Through protein sequence BLAST analysis and enzyme engineering, researchers significantly improved the dynamic properties of the native PdhR system, enhancing its sensitivity, leakage control, and dynamic range [5]. The engineered system creates a bifunctional genetic circuit capable of dynamic and autonomous control of central metabolism by responding to pyruvate fluctuations, a key metabolic node connecting glycolysis to the TCA cycle [5].

Figure 1: Pyruvate-Responsive Genetic Circuit Mechanism. The transcription factor PdhR regulates gene expression in response to pyruvate levels, creating a feedback loop for metabolic control.

Implementation for Metabolic Pathway Optimization

The engineered PdhR biosensor system has been successfully applied to optimize biosynthesis of compounds derived from central metabolism, including:

- UDP-sugar-derived compounds such as trehalose

- Shikimate pathway-derived compounds such as 4-hydroxycoumarin [5]

In both applications, the dynamic regulation system demonstrated its broad applicability by fine-tuning metabolic fluxes to minimize toxic intermediate accumulation, enhance metabolic balance, and improve overall product yield. This approach showcases the potential for extending similar strategies to other central metabolism-derived compounds.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Dynamic Regulation Systems

| Application | Host Organism | Regulated Metabolite | Product Titer Improvement | Key Circuit Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trehalose production | E. coli | Pyruvate | Not specified | PdhR-based biosensor |

| 4-Hydroxycoumarin production | E. coli | Pyruvate | Not specified | PdhR-based biosensor |

| Biofuel production | E. coli | Various intermediates | Significant yield enhancement | CRISPRi-enabled dynamic control |

| n-Butanol production | E. coli | NADPH/Redox balance | Enhanced yield | Redox-sensitive biosensors |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Dynamic Metabolic Controller

Strain Construction and Plasmid Design

Materials:

- Bacterial Strains: E. coli XL1-Blue for cloning; BW25113 containing F' from XL1-Blue for metabolic engineering [5]

- Growth Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin 100 μg/mL, kanamycin 50 μg/mL, chloramphenicol 30 μg/mL) [5]

- Genetic Parts: PdhR transcription factor gene, PpdhR promoter, target metabolic genes

Procedure:

- Circuit Assembly:

- Amplify the engineered PdhR gene and PpdhR promoter sequence using PCR

- Clone the PdhR expression cassette into a medium-copy plasmid under a constitutive promoter

- Clone the PpdhR promoter upstream of your target metabolic genes in a compatible plasmid

- Include appropriate antibiotic resistance markers for plasmid maintenance

- Strain Transformation:

- Introduce the assembled plasmids into your production host via electroporation or chemical transformation

- Plate transformed cells on selective media and incubate overnight at 37°C

- Verify correct assembly by colony PCR and sequencing

Figure 2: Genetic Circuit Implementation Workflow. Step-by-step procedure for constructing and validating a dynamic metabolic controller.

Bioreactor Cultivation and Dynamic Performance Assessment

Materials:

- Bioreactor System: 1L benchtop bioreactor with temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen control

- Analytical Instruments: HPLC for metabolite analysis, spectrophotometer for optical density measurements

- Culture Media: Defined minimal media with carbon source appropriate for your pathway

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation:

- Inoculate a single colony into 5 mL LB with antibiotics, incubate overnight at 37°C with shaking

- Dilute 1:100 into fresh medium and grow to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6)

Bioreactor Operation:

- Transfer inoculum to bioreactor containing production medium

- Maintain optimal growth conditions (37°C, pH 7.0, adequate aeration)

- Monitor culture density, carbon source consumption, and potential byproducts

Performance Analysis:

- Sample culture periodically for OD600 measurement and metabolite analysis

- Quantify intracellular pyruvate levels using enzymatic assays or LC-MS

- Measure target product concentration using appropriate analytical methods

- Compare growth characteristics and product titers between controlled and non-controlled strains

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| PdhR/PpdhR System | Pyruvate-responsive genetic controller | Dynamic regulation of central metabolism |

| Transcription Factor Biosensors | Metabolite sensing and response | Nutrient-responsive pathway regulation |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing | Gene knockouts, regulatory element insertion |

| sRNA Libraries | Post-transcriptional regulation | Fine-tuning gene expression with low burden |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Circuit characterization | Quantifying promoter activity and dynamics |

| Metabolite Assay Kits | Metabolic flux analysis | Quantifying key intermediates (e.g., pyruvate, NADH) |

| (+-)-5,6-Epoxy-5,6-dihydroquinoline | (+-)-5,6-Epoxy-5,6-dihydroquinoline, CAS:130536-37-7, MF:C9H7NO, MW:145.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyrazino[2,3-f][4,7]phenanthroline | Pyrazino[2,3-f][4,7]phenanthroline|CAS 217-82-3 | Pyrazino[2,3-f][4,7]phenanthroline (CAS 217-82-3) is a specialist ligand for coordination chemistry and materials science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The implementation of dynamic regulation represents a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, moving from static optimization to responsive systems that maintain cellular fitness while maximizing production. The pyruvate-responsive system exemplifies how central metabolite sensing can create robust controllers for diverse applications [5]. However, several challenges remain in the widespread adoption of these approaches.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on:

- Multi-input controllers that respond to multiple metabolic signals simultaneously

- Orthogonal circuit components that minimize interference with host physiology

- Machine learning approaches for predictive circuit design and optimization

- Expanded biosensor libraries for a broader range of metabolic intermediates

As the field advances, integrating dynamic regulation with emerging technologies in computational modeling and high-throughput screening will enable more sophisticated control strategies that further enhance the balance between growth and production in engineered microbial systems.

From Blueprint to Bioreactor: Designing and Applying Metabolic Control Circuits

The engineering of genetic circuits for precise metabolic control represents a cornerstone of modern synthetic biology, with transformative potential for biotechnology and therapeutic development. However, the transition from a conceptual design to a functional biological system in a living cell is fraught with uncertainty. Circuit behavior is influenced by a complex interplay of factors including context-dependent gene expression, cellular resource allocation, and evolutionary pressures that can lead to performance degradation over time [17] [3]. Computational-assisted design addresses these challenges by providing a framework to predict circuit dynamics before experimental implementation, enabling researchers to explore design space efficiently and avoid costly iterative cycles of trial and error.

Mathematical models serve as logical machines that articulate the expectations of specific biological hypotheses and allow researchers to derive their non-obvious implications [18]. In the context of genetic circuit implementation for metabolic control, this approach enables the systematic evaluation of how circuit components interact with host physiology. By simulating circuit behavior under various conditions and potential mutations, computational models provide invaluable insights that guide the design of more robust and predictable systems, ultimately accelerating the development of reliable genetic tools for metabolic engineering.

Foundational Modeling Concepts for Genetic Circuits

Conceptual Framework for Model Development

Building an effective model of a genetic circuit requires careful consideration of the system's essential components and their interactions. The process begins with defining the circuit boundaries, identifying which elements belong to "the system" and which constitute the external environment [18]. This abstraction step is crucial for creating a manageable representation of the biological reality. Subsequently, each node in the circuit should represent a distinct biological entity (e.g., transcription factor, metabolite), while edges represent their interactions (e.g., transcriptional activation, metabolic conversion) [18].

A critical principle in model development is aligning the model complexity with the specific research question. For instance, a model investigating general circuit logic may employ simple differential equations, while a model predicting quantitative metabolic flux dynamics might require detailed enzymatic parameters [18]. Importantly, all model assumptions must be explicitly stated, as they form the foundation for interpreting simulation results and understanding the model's limitations. These assumptions might include neglecting certain metabolic cross-talk or assuming constant host resource availability, both of which can significantly impact model predictions [18].

Mathematical Representations of Circuit Dynamics

The dynamic behavior of genetic circuits is most commonly captured through ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the rates of change for each molecular species in the system. For a simple protein expression circuit, the core equations typically include:

- Transcription Rate: ( \frac{d[mRNA]}{dt} = \alpha \cdot f(regulators) - \delta_{mRNA} \cdot [mRNA] )

- Translation Rate: ( \frac{d[Protein]}{dt} = \beta \cdot [mRNA] - \delta_{protein} \cdot [Protein] )

Where ( \alpha ) represents the maximal transcription rate, ( \beta ) the translation rate, and ( \delta ) the degradation rates for mRNA and protein, respectively [3]. The function ( f(regulators) ) captures the regulatory logic governing transcription, which might include activation, repression, or more complex combinatorial control.

For metabolic applications where circuits interface with central metabolism, these equations must expand to incorporate metabolite pools and enzymatic conversions. The "host-aware" modeling framework explicitly accounts for the coupling between circuit expression and host physiology by modeling resource competition for ribosomes, RNA polymerases, and metabolic precursors [3]. This approach captures the phenomenon of "burden," where circuit expression reduces host growth rate, creating selective pressures that can lead to mutant accumulation and performance degradation over time [3].

Protocols for Model Construction and Experimental Validation

Computational Implementation Workflow

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Genetic Circuit Design and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TinkerCell | Visual construction and analysis of biological networks | Component-based modeling, flexible equation assignment, extensible via plugins | Synthetic biology circuit design with biological parts [19] |

| iBioSim | Dynamic simulation of genetic circuits | ODE model generation and analysis, Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg method implementation | Circuit behavior prediction under optimal lab conditions [17] |

| Model SEED | Genome-scale metabolic network reconstruction | Integrates genome annotations, gene-protein-reaction associations, thermodynamic analysis | Metabolic engineering context for circuit implementation [20] |

| optStoic/novoStoic | De novo metabolic pathway design | Balances stoichiometry of co-metabolites and cofactors, incorporates novel transformations | Designing pathways for metabolic control strategies [21] |

The protocol for constructing a predictive model begins with circuit definition using biological parts with known characteristics. In TinkerCell, users select components from a catalog containing proteins, small molecules, promoters, and coding regions, then connect them to form a complete network [19]. The software automatically assigns default rate equations based on the biological context of the connections, though these can be modified by the user. For example, connecting a promoter, ribosomal binding site, and protein coding region triggers automatic assignment of transcription and translation reactions [19].