Dynamic Metabolic Engineering: Revolutionizing Bioproduction with Smart Cellular Control

Dynamic metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift from static genetic modification to the design of autonomous, self-regulating microbial cell factories.

Dynamic Metabolic Engineering: Revolutionizing Bioproduction with Smart Cellular Control

Abstract

Dynamic metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift from static genetic modification to the design of autonomous, self-regulating microbial cell factories. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational theories of dynamic control and its critical role in overcoming metabolic imbalances that limit bio-production. We delve into the core methodological toolkit—including biosensors, genetic circuits, and AI-driven regulation—and their application in optimizing the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and platform chemicals. The content further addresses troubleshooting central metabolism flux imbalances and showcases validation through comparative case studies that demonstrate significant enhancements in titer, yield, and productivity. By synthesizing advances from theoretical frameworks to industrial implementation, this review highlights the transformative potential of dynamic control strategies for sustainable and economically viable biomanufacturing.

From Static to Smart: The Foundations of Dynamic Metabolic Control

Dynamic metabolic engineering is a rapidly developing field that addresses biological challenges in bio-production by designing genetically encoded control systems. These systems enable microbial cells to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to their external and internal metabolic state, leading to significant improvements in production titers, rates, and yields (TRY) metrics [1]. Unlike traditional static engineering, which involves fixed genetic modifications, dynamic control allows for real-time flux redistribution, balancing the often-competing demands of cell growth and product synthesis. This approach is particularly valuable for optimizing pathways where intermediate metabolites are toxic or when high product yields require complex, temporally regulated expression of pathway enzymes [1] [2].

The theoretical foundation for dynamic metabolic engineering is built upon various control strategies, including two-stage, continuous, and population-behavior control [1]. These strategies are implemented using a toolkit of biological parts and modules that function as sensors, actuators, and controllers. The advancement of this field has been enabled by synthetic biology, which provides the tools to construct sophisticated genetic circuits that can process intracellular information and execute pre-programmed logical operations to rewire metabolism efficiently [2].

Core Principles and Molecular Tools

Theoretical Control Strategies

Dynamic metabolic control systems can be categorized based on their operational logic and the signals they process:

- Two-Stage Control: This strategy separates the fermentation process into distinct growth and production phases. While conceptually simple and widely used, it lacks the flexibility to respond to real-time metabolic needs [1].

- Continuous Control: This approach allows for continuous, autonomous adjustment of metabolic fluxes throughout the fermentation process. It can be further subdivided into:

- Pathway-Dependent Control: Utilizes biosensors (e.g., transcription factors, riboswitches) that respond specifically to a pathway metabolite, linking its concentration directly to the regulation of relevant genes [2].

- Pathway-Independent Control: Employs sensors that respond to generic physiological signals, such as cell density via quorum sensing (QS), rather than specific pathway metabolites. This makes them broadly applicable across different metabolic contexts [2].

- Population Behavior Control: Leverages quorum sensing circuits to coordinate behavior across a microbial population, ensuring a unified metabolic response that is tied to the density of the culture [1] [2].

The Molecular Toolkit: Sensors and Actuators

Implementing these strategies requires a suite of molecular components that function as sensors and actuators.

Sensors: These components detect specific internal or external signals.

- Metabolite Biosensors: These include transcription factors or riboswitches that change conformation upon binding a target metabolite (e.g., glucosamine-6-phosphate), thereby regulating the expression of downstream genes [2].

- Quorum Sensing Systems: These detect population density. For example, in Bacillus subtilis, the PhrQ-RapQ-ComA system involves the PhrQ signaling peptide that accumulates extracellularly as cell density increases. It is sensed by the membrane receptor RapQ, ultimately leading to the phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor ComA, which can then drive the expression of target genes [2].

Actuators: These components execute the control action by modulating gene expression.

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): A powerful and programmable platform for gene repression. The type I CRISPRi system, which is often less toxic than the common Cas9-based type II system, uses a Cascade complex guided by CRISPR RNA (crRNA) to bind specific DNA sequences and block transcription [2].

- Transcriptional Repressors/Activators: Classical transcription factors that can be deployed to control promoter activity.

The integration of sensors and actuators creates closed-loop control circuits. For instance, a quorum-sensing module can be wired to control the expression of a CRISPRi system, enabling density-dependent repression of target metabolic genes [2].

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents and materials for implementing dynamic metabolic control.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| QS System Components (e.g., PhrQ, RapQ, ComA) | Genetic parts that sense cell density and transduce the signal to activate a transcriptional response [2]. |

| Type I CRISPRi System | A programmable actuator for gene repression; typically consists of genes for the Cascade complex and vectors for expressing crRNA [2]. |

| crRNA Expression Vectors | Plasmids designed for easy cloning and expression of guide RNAs that target specific metabolic genes [2]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters (e.g., GFP) | Proteins used to quantify the activity and performance of genetic circuits in vivo [2]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Computational models used to predict metabolic fluxes and identify key gene targets for intervention. Tools like Fluxer can analyze and visualize these models [3]. |

Experimental Implementation and Workflow

Implementing dynamic metabolic control is an iterative process involving design, construction, and testing. The following workflow and diagram outline the key steps for developing a QS-controlled CRISPRi (QICi) system, as demonstrated in Bacillus subtilis [2].

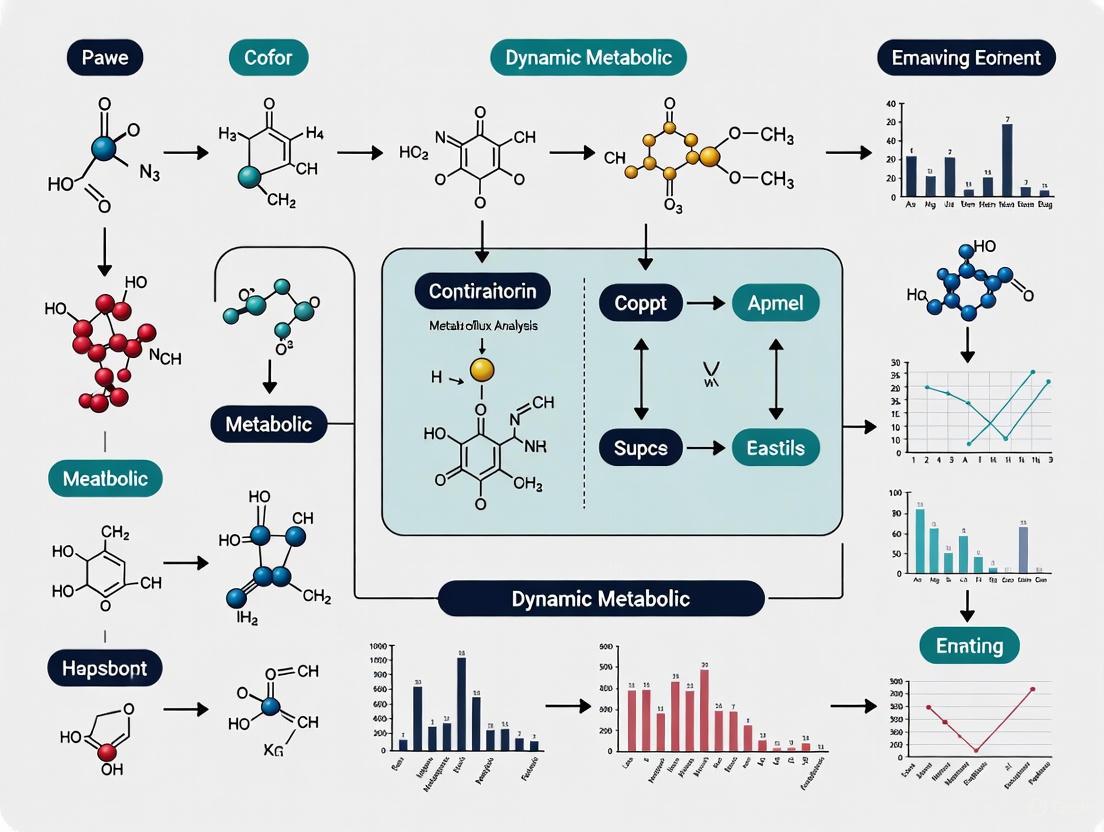

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing a QS-controlled CRISPRi (QICi) system.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol details the key steps for constructing and validating a dynamic metabolic control system, based on the development of the QICi toolkit in B. subtilis [2].

In Silico Target Identification:

- Objective: Identify a key metabolic gene whose repression is predicted to enhance product yield.

- Methodology: Use a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) of the production host. Upload the model in SBML format to a flux analysis tool like Fluxer [3].

- Procedure: Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to simulate metabolic fluxes under growth and production conditions. Analyze the resulting flux tree or dendrogram to pinpoint enzymatic reactions that act as critical control nodes (e.g., citrate synthase, citZ, in the TCA cycle for DPA production, or phosphofructokinase, pfkA, in glycolysis for riboflavin production) [3] [2].

Genetic Circuit Construction:

- Circuit Design: Design a genetic circuit where a quorum-sensing (QS)-responsive promoter (e.g., activated by ComA in B. subtilis) drives the expression of the type I CRISPRi Cascade genes. The system also includes a constitutively expressed crRNA targeting the gene identified in Step 1 [2].

- Strain and Plasmid Construction:

- Host Strains: Use an appropriate industrial chassis like B. subtilis MU8 for DPA production or B. subtilis 168 for riboflavin production [2].

- Molecular Cloning: Clone the designed crRNA sequence into a crRNA expression vector. Assemble the final plasmid(s) containing the QS-controlled CRISPRi system using TA cloning or one-step cloning methods.

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into the host strain using standard transformation protocols. Select transformants using appropriate antibiotics (e.g., bleomycin, chloramphenicol) [2].

Fermentation and Dynamic Regulation:

- Cultivation Conditions: Grow the engineered strain in a defined medium (e.g., M9 medium with glucose) in a bioreactor. Maintain optimal temperature (37°C) and agitation (200 rpm) [2].

- Autonomous Activation: During the early exponential phase, cell density and the QS signal (PhrQ) are low. The CRISPRi system remains off, allowing expression of the target gene and supporting robust cell growth.

- Onset of Repression: As the culture reaches high cell density in the mid-to-late exponential phase, the accumulated QS signal triggers the expression of the CRISPRi system. This leads to repression of the target gene (e.g., citZ), dynamically redirecting metabolic flux away from growth-associated pathways and toward the desired product.

Validation and Analytics:

- Circuit Performance: Monitor circuit activity using a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP) linked to the QS-responsive promoter. Measure optical density (OD600) and relative fluorescence units (RFU) every 2 hours to correlate cell density with circuit activation [2].

- Product Quantification: Quantify the final product titer using analytical methods such as HPLC. Compare the performance of the dynamically controlled strain against control strains (e.g., wild-type, static overexpression, or knockout mutants).

- Data Analysis: Calculate key metrics including Titer (g/L), Rate (g/L/h), and Yield (g product/g substrate). Statistical analysis should be performed to confirm the significance of improvements.

Application Case Studies and Quantitative Outcomes

The efficacy of dynamic metabolic engineering is demonstrated by its application in enhancing the production of valuable compounds. The table below summarizes key experimental data from two case studies implementing the QICi system in B. subtilis [2].

Table 2: Performance metrics of dynamic metabolic engineering in B. subtilis for DPA and Riboflavin production.

| Target Product | Gene Targeted for Dynamic Regulation | Metabolic Pathway Objective | Key Engineering Interventions | Reported Titer (Fed-Batch) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-pantothenic acid (DPA) | citZ (citrate synthase) | Reduce TCA cycle flux to balance growth with DPA precursor supply [2]. | Dynamic downregulation of citZ via QICi; pantoate pathway engineering; enhanced cofactor supply; suppression of sporulation [2]. | 14.97 g/L [2] |

| Riboflavin (RF) | pfkA (phosphofructokinase) | Redirect carbon flux from glycolysis (EMP) to the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [2]. | Dynamic downregulation of pfkA via QICi to enhance PPP precursor supply for riboflavin biosynthesis [2]. | 2.49-fold increase vs. control [2] |

The logical flow of the QICi system in redirecting central carbon metabolism for these products is visualized in the following pathway diagram.

Diagram 2: Metabolic flux redistribution using the QICi system.

Dynamic metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift from static genetic modification to intelligent, self-regulating cellular systems. By leveraging synthetic biology tools like biosensors, quorum sensing, and programmable CRISPRi systems, it is possible to create strains that autonomously optimize their metabolic performance in real-time. The documented success in significantly boosting the production of compounds like d-pantothenic acid and riboflavin in B. subtilis underscores the transformative potential of this approach [2].

The future of this field lies in the development of more precise and robust genetic components, the integration of multiple orthogonal control systems, and the application of machine learning to design optimal control circuits. As the molecular toolkit expands and our understanding of cellular regulation deepens, dynamic metabolic engineering is poised to become a standard methodology for developing high-performance microbial cell factories for sustainable biomanufacturing of pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and materials.

Metabolic engineering, defined as the science of rewiring cellular metabolism to enhance the production of chemicals and fuels from renewable resources, has undergone a remarkable transformation since its formal inception in the early 1990s [4]. This field has progressed through three distinct waves of technological innovation, each building upon the previous to address increasingly complex challenges in bio-production. The first wave established rational approaches to pathway manipulation, the second incorporated systems-level understanding through genome-scale models, and the current third wave leverages synthetic biology tools to implement sophisticated dynamic control systems [4]. This progression has been largely driven by the need to overcome the inherent robustness of cellular metabolic networks, which resist diversion from their natural, growth-oriented functions [4]. The evolution has moved metabolic engineering from simple, static genetic modifications toward dynamic, autonomous control systems that can sense and respond to metabolic states, thereby optimizing the trade-offs between cell growth and product formation that have long challenged the field [5] [6].

The First Wave: Rational Metabolic Engineering

The first wave of metabolic engineering began in the 1990s and was characterized by rational, hypothesis-driven approaches to pathway modification. During this period, scientists recognized that natural metabolic pathways could be enumerated and assessed for converting specific substrates to target products [4]. Seminal papers by Bailey and by Stephanopoulos and Vallino essentially initiated the field by establishing the fundamental principles of metabolic flux manipulation [4].

Core Principles and Methodologies

First-wave metabolic engineering relied on the identification of potential "rate-limiting steps" in metabolic pathways through techniques such as metabolic flux analysis. The primary strategy involved the targeted overexpression or deletion of genes encoding key metabolic enzymes to redirect flux toward desired products [4]. This approach required a detailed understanding of pathway stoichiometry and regulation, but operated without the comprehensive, genome-wide perspective that would later emerge.

A classic example demonstrating the success of this approach is the overproduction of lysine in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Through metabolic flux analysis with labeled glucose, pyruvate carboxylase and aspartokinase were identified as potential bottlenecks in the lysine biosynthesis pathway. When both enzymes were simultaneously expressed, this engineered strain achieved a 150% increase in lysine productivity while maintaining the same growth rate as the control strain [4]. This case exemplified the rational approach of identifying and modifying specific control points in metabolism.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Identification and Engineering of Rate-Limiting Steps

- Pathway Analysis: Use tracer compounds (e.g., 14C-labeled glucose) to determine in vivo metabolic flux distributions in the native strain [4].

- Bottleneck Identification: Identify enzymes with significant metabolite accumulation upstream and limited flux downstream as potential rate-limiting steps.

- Genetic Modification: Clone genes encoding target enzymes into appropriate expression vectors under strong promoters.

- Strain Evaluation: Measure product titers, yields, and productivity in engineered versus control strains under controlled fermentation conditions.

The Second Wave: Systems Biology Integration

The second wave of metabolic engineering emerged in the 2000s, propelled by advances in systems biology and the development of genome-scale modeling approaches. This wave expanded the view of metabolic pathways from isolated sequences of reactions to interconnected networks functioning at a systemic level [4]. The pioneering work of Bernhard Ø Palsson was particularly influential in establishing genotype-phenotype relationships that enabled exploration of the full metabolic potential of cell factories [4].

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs)

The cornerstone of second-wave metabolic engineering was the development and application of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). These computational reconstructions encompass the entire metabolic network of an organism, including all known biochemical reactions, gene-protein-reaction associations, and thermodynamic constraints [4] [7]. GEMs enabled in silico prediction of metabolic behaviors under different genetic and environmental conditions.

Key computational tools that emerged during this period included:

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A constraint-based modeling approach that predicts flux distributions in metabolic networks by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass formation) [7].

- OptKnock: An algorithm that identifies gene knockout strategies for coupling growth with product formation [6].

- Model SEED: An automated pipeline for high-throughput generation of genome-scale metabolic models from annotated genomic sequences [7].

These tools successfully predicted strategies for bioengineering applications such as bioethanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and adipic acid production in Escherichia coli [4].

Computational and Experimental Workflow

The integration of computational modeling with experimental validation became the standard approach during this wave. The typical workflow involved:

- Network Reconstruction: Building a genome-scale metabolic model using annotated genomic data and biochemical databases [7].

- In Silico Prediction: Using computational algorithms to identify genetic modifications that would enhance product formation.

- Strain Construction: Implementing predicted modifications using genetic engineering tools.

- Systems Validation: Using omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to verify model predictions and refine the network reconstruction.

Figure 1: Systems Biology Workflow for Metabolic Engineering. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of model building, prediction, and experimental validation characteristic of second-wave metabolic engineering.

The Third Wave: Synthetic Biology and Dynamic Control

The current third wave of metabolic engineering began in the 2010s, marked by the integration of sophisticated synthetic biology tools that enable precise control over metabolic pathways. This wave started with foundational work by Jay D. Keasling, who demonstrated that complete metabolic pathways could be designed, constructed, and optimized using synthetic nucleic acid elements for production of noninherent chemicals such as artemisinin [4]. The third wave has expanded the array of attainable products and significantly improved titers, rates, and yields through dynamic control strategies [4] [5].

Dynamic Metabolic Engineering Principles

Dynamic metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift from static genetic modifications toward genetically encoded control systems that allow microbes to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to changing internal and external conditions [5]. This approach addresses critical challenges in metabolic engineering, including metabolic burden, cofactor imbalance, and accumulation of toxic intermediates [5] [6].

Key theoretical frameworks for dynamic control include:

- Two-Stage Metabolic Switches: Decouple biomass accumulation from product formation by implementing genetic circuits that switch between growth and production phases [5].

- Continuous Metabolic Control: Utilize biosensors and feedback loops to maintain optimal flux distributions throughout the fermentation process [5].

- Population Behavior Control: Implement quorum-sensing systems to coordinate metabolic behaviors across microbial populations [5].

The theoretical benefit of dynamic control was demonstrated in early modeling studies, which predicted that dynamically switching enzyme expression could improve glycerol production by over 30% compared to static approaches [5] [6].

Molecular Tools for Dynamic Control

The implementation of dynamic control systems relies on two fundamental components: sensors that detect metabolic states and actuators that modulate gene expression accordingly [5].

Biosensors for Metabolic Intermediates:

- Transcription Factor-Based Sensors: Native or engineered transcription factors that bind specific metabolites and regulate output promoter activity.

- RNA-Based Sensors: Riboswitches and other RNA devices that undergo conformational changes upon metabolite binding.

- Protein-Based Sensors: Allosteric enzymes or two-component systems that transduce metabolic signals into genetic responses.

Actuators for Metabolic Modulation:

- Promoter Systems: Tunable promoters that respond to biosensor outputs.

- CRISPRi Systems: CRISPR-based interference for targeted gene repression.

- Protein Degradation Tags: SsrA and other tags for controlled protein degradation [6].

Figure 2: Dynamic Metabolic Control System Architecture. This diagram shows the core components of a dynamic metabolic engineering system, including biosensors, genetic circuits, and actuators that create autonomous feedback control.

Representative Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Two-Stage Dynamic Control System

- Valve Identification: Use computational algorithms (e.g., OptSwitch) to identify metabolic reactions that can serve as effective switches between growth and production states [5].

- Biosensor Selection: Choose or engineer a biosensor that responds to a key metabolic indicator (e.g., acetyl-phosphate for glycolytic flux) [6].

- Circuit Construction: Assemble genetic elements connecting the biosensor to the metabolic valve using standard synthetic biology techniques (Golden Gate assembly, Gibson assembly).

- System Characterization: Measure the transfer function of the biosensor-circuit system and the dynamic range of the metabolic valve in laboratory strains.

- Performance Validation: Test the engineered strain in controlled bioreactors, comparing productivity metrics against static control strains.

Protocol: Biosensor-Mediated Pathway Balancing

- Pathway Analysis: Identify potential metabolic bottlenecks or toxic intermediate accumulation points in heterologous pathways.

- Biosensor Development: Engineer metabolite-responsive promoters using transcription factors that bind the target intermediate.

- Controller Design: Construct genetic circuits that downregulate upstream pathway enzymes when intermediate concentrations exceed optimal levels.

- Library Screening: Generate variant libraries with different expression levels of biosensor and actuator components.

- High-Throughput Selection: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate strains with desired dynamic control characteristics.

Quantitative Comparison of Metabolic Engineering Approaches

Table 1: Performance Metrics Across the Three Waves of Metabolic Engineering

| Product | Host Organism | Wave | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Key Engineering Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysine | Corynebacterium glutamicum | First | N/A | N/A | +150% | Overexpression of pyruvate carboxylase and aspartokinase [4] |

| 1,4-Butanediol | E. coli | Second | Commercial | Commercial | Commercial | Genome-scale model prediction [8] |

| Artemisinin | S. cerevisiae | Third | Commercial | Commercial | Commercial | Heterologous pathway engineering [4] [8] |

| Lycopene | E. coli | Third | 18-fold improvement | N/A | N/A | Dynamic control of pps and idi [6] |

| 3-Hydroxypropionic acid | C. glutamicum | Third | 62.6 | 0.51 | N/A | Substrate and genome editing engineering [4] |

| Lactic Acid | C. glutamicum | Third | 264 | 0.95 | N/A | Modular pathway engineering [4] |

| Succinic Acid | E. coli | Third | 153.36 | N/A | 2.13 | Modular pathway engineering, high-throughput genome engineering [4] |

Table 2: Computational Tools for Metabolic Engineering Across Development Waves

| Tool Name | Wave | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | First | Quantifies in vivo metabolic fluxes | Identification of rate-limiting steps in lysine production [4] |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Second | Predicts steady-state flux distributions | Bioethanol production optimization [4] [7] |

| OptKnock | Second | Identifies gene knockout strategies | Succinic acid production in E. coli [6] |

| ecFactory | Third | Predicts enzyme-constrained metabolic engineering targets | Production of 103 chemicals in S. cerevisiae [9] |

| GECKO Toolbox | Third | Incorporates enzyme kinetics into genome-scale models | Identification of protein-constrained products [9] |

| KEGG Pathway | Second/Third | Metabolic pathway database and analysis | Pathway prospecting and comparative analysis [7] |

| MetaCyc/BioCyc | Second/Third | Metabolic pathway database | Network reconstruction and enzyme information [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Models | Computational Tool | Predicts metabolic fluxes and identifies engineering targets | OptKnock for gene knockout strategies [6] |

| Biosensor Transcription Factors | Molecular Tool | Detects metabolite levels and transduces signals | Ntr regulon for acetyl-phosphate sensing [6] |

| Synthetic Promoter Libraries | Genetic Part | Provides tunable expression levels | Fine-tuning pathway enzyme expression [6] |

| CRISPRi Systems | Editing Tool | Enables targeted gene repression | Dynamic control of essential genes [5] |

| SsrA Degradation Tags | Protein Engineering | Enables controlled protein degradation | Targeted degradation of FabB for octanoate production [6] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Screening Tool | Enables high-throughput selection | FACS screening of dynamic control systems [5] |

| Microfluidic Devices | Screening Platform | Enables single-cell analysis | Characterization of population heterogeneity [5] |

| Enzyme-Constrained Models (ecModels) | Computational Tool | Incorporates protein allocation constraints | Identification of protein-limited reactions [9] |

The evolution of metabolic engineering through three distinct waves has transformed our ability to reprogram cellular metabolism for industrial bio-production. The field has progressed from simple rational approaches to sophisticated dynamic control strategies that autonomously manage the fundamental trade-offs between cell growth and product formation. Current research continues to advance the third wave through several emerging frontiers:

Machine Learning Integration: The combination of mechanistic models with machine learning approaches promises to accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle, enabling more predictive strain design and reducing development timelines [4] [9].

Advanced Biosensor Engineering: Expanding the repertoire of metabolite-responsive elements through protein engineering and computational design will enable more precise dynamic control over a wider range of metabolic pathways [5].

Multi-Strain Coordination: Developing communication systems between different engineered strains to distribute metabolic burden and enable division of labor in complex biosynthetic pathways [5].

Enzyme-Constrained Modeling: The integration of enzymatic capacity constraints into genome-scale models, as exemplified by the ecFactory pipeline, provides more realistic predictions of metabolic capabilities and limitations [9].

The progression from static to dynamic metabolic control represents a fundamental shift in how we approach cellular engineering. By creating systems that can autonom sense, compute, and respond to changing metabolic conditions, dynamic metabolic engineering offers a powerful framework for overcoming the inherent trade-offs that have long limited bio-production. As these tools and strategies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly enable the production of an ever-expanding range of valuable chemicals, materials, and pharmaceuticals from renewable resources, further establishing microbial cell factories as pillars of sustainable industrial processes.

Dynamic metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift in the design of microbial cell factories, moving from static, constitutive genetic expression to engineered systems that can autonomously sense and respond to changing metabolic conditions [1] [10]. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering: the inherent trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis. Introducing heterologous pathways often disrupts native metabolism, creating burden, cofactor imbalances, or toxic intermediate accumulation that impairs host fitness and overall production metrics [11] [12]. Dynamic control strategies solve this problem by enabling real-time flux adjustment, allowing engineers to design strains that initially prioritize biomass accumulation before switching to high-yield production states, or that continuously balance these competing objectives [1]. These strategies are broadly categorized into three core frameworks—two-stage, continuous, and population-based control—each with distinct mechanisms, implementation requirements, and performance characteristics [10]. The theoretical foundation for these approaches draws from control theory, synthetic biology, and systems biology, providing a mechanistic basis for designing controllers that improve titers, rates, and yields beyond what is achievable with static optimization alone [1].

Theoretical Foundation and Design Principles

The theoretical underpinning of dynamic metabolic control rests on the formal application of control logic to biological circuits [10]. At its simplest, this involves designing genetic circuits that implement feedback control, where an intracellular metabolite or extracellular signal is sensed and used to regulate pathway enzyme expression or activity. The core design principles address the fundamental growth-synthesis trade-off, where competition for limited cellular resources between native metabolism and heterologous pathways inherently limits production performance in static strains [11]. Computational models using "host-aware" frameworks that capture competition for both metabolic and gene expression resources have revealed that maximum volumetric productivity and yield in batch cultures require an optimal sacrifice in growth rate to achieve sufficient synthesis, a balance that dynamic control strategies are uniquely positioned to deliver [11].

Table 1: Core Control Logics in Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

| Control Logic | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open-Loop (Two-Stage) | Manual, pre-programmed switching between growth and production phases based on time or external inducer [10]. | Simple design and implementation; effectively decouples growth and production. | Requires external intervention; not responsive to internal metabolic state. |

| Closed-Loop (Feedback) | Autonomous regulation based on sensing of intracellular metabolites or extracellular signals [10]. | Self-optimizing; maintains homeostasis; responds to real-time process variability. | Biosensor development can be complex; potential instability or oscillation. |

| Population Control | Coordination of behaviors across a microbial population to ensure culture-level performance [1]. | Prevents sub-population formation; ensures synchronized production phase. | Requires cell-cell communication circuits; more complex genetic design. |

Two-Stage Control Strategies

Core Theory and Implementation

The two-stage control framework, also known as two-phase dynamic regulation, deliberately decouples the fermentation process into distinct temporal phases: a growth phase dedicated to rapid biomass accumulation, followed by a production phase where metabolic flux is redirected toward the target compound [10] [12]. This decoupling buffers the inherent conflict between endogenous metabolism and heterologous pathways, as production enzymes or pathway repressions are only activated after a substantial cell population has been established [10]. The theoretical motivation is to overcome the growth-synthesis trade-off by first maximizing the catalyst (cell) concentration before activating the production machinery, thereby maximizing volumetric productivity [11].

Experimental Protocols and Induction Mechanisms

Implementing a two-stage system requires a genetic switch to transition from growth to production. This is typically achieved using inducible promoters controlled by chemical or physical signals [10].

Chemical Inducers: Common systems include aTc and IPTG in E. coli, and the glucose-repressed, galactose-activated GAL promoters in S. cerevisiae [10]. The standard protocol involves growing the culture in a non-inducing medium until the mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.5-0.8), followed by the addition of a predetermined concentration of the chemical inducer (e.g., 0.1-1 mM IPTG) to initiate the production phase.

Physical Inducers: Temperature and light are widely used physical triggers. The classic λ phage PR/PL promoter system, repressed by CI at 30°C and activated at 37-42°C, is a well-established tool [10]. A standard workflow involves growing cultures at 30°C until the desired density is reached, then rapidly shifting the temperature to 42°C to activate the production genes. Optogenetic systems, such as the EL222 blue-light-sensitive protein, offer high temporal precision [10]. In a reported isobutanol production system in yeast, blue light represses a competing gene (pdc), while darkness activates the biosynthetic gene (ILV2), creating a light-defined growth phase and a dark-defined production phase [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Two-Stage Induction Systems

| Inducer Type | Example System | Typical Host | Induction Protocol | Performance Gain (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical (aTc/IPTG) | TetR/TetO; LacI/LacO | E. coli | Add 0.1-1 mM inducer at mid-exponential phase | Used for anthocyanin, isopropanol, 1,4-butanediol [10] |

| Chemical (Galactose) | GAL1, GAL10 promoters | S. cerevisiae | Shift from glucose to galactose media | Increased artemisinin productivity [10] |

| Temperature | PR/PL promoter system | E. coli | Temperature shift from 30°C to 42°C | 3.8-fold increase in ethanol productivity [10] |

| Light (Blue) | EL222/Pc120 system | S. cerevisiae | Shift from blue light to darkness | 1.6-fold increase in isobutanol titer [10] |

| pH | PYGP1, PGCW14 promoters | S. cerevisiae | Allow culture to acidify or buffer at low pH | 10-fold increase in lactic acid titer |

Figure 1: Generalized experimental workflow for a two-stage dynamic control process, showing the decoupled growth and production phases.

Continuous Control Strategies

Core Theory and Implementation

Continuous control strategies, often implemented as closed-loop feedback systems, enable autonomous, real-time adjustment of metabolic flux in response to the cell's instantaneous metabolic state [1] [10]. Unlike the pre-programmed switching in two-stage systems, continuous control uses biosensors to detect specific intracellular metabolites, which then modulate the expression of pathway enzymes to maintain an optimal flux balance without external intervention [10]. This approach mimics the "just-in-time transcription" found in natural metabolic networks and is particularly valuable for managing toxic intermediate accumulation or for fine-tuning flux distribution at key metabolic branch points [10].

Key Control Logics and Circuit Designs

The functionality of continuous control systems is defined by their underlying regulatory logic, which is hardwired into the genetic circuit design [10].

Positive Feedback Control: This logic amplifies a desired metabolic state. For example, a biosensor for a pathway intermediate can be designed to activate the expression of the pathway enzymes, creating a self-reinforcing production loop that locks the cell into a high-synthesis state once a metabolite threshold is crossed [10].

Negative Feedback Control: This logic maintains homeostasis by downregulating pathway enzyme expression when intermediate concentrations become too high, preventing the accumulation of toxic metabolites and stabilizing flux [10].

Oscillation-Based Control: Some advanced circuits are designed to generate periodic pulses of gene expression. This can be useful to avoid the negative physiological impacts of sustained, high-level expression of heterologous proteins, potentially improving long-term culture stability and productivity [10].

Population-Based Control Strategies

Core Theory and Implementation

Population-based control strategies focus on coordinating behavior across the entire cellular population within a bioreactor, rather than optimizing individual cell performance [1]. The core theoretical challenge is the emergence of sub-populations, where non-producing "cheater" cells that avoid the metabolic burden of synthesis can outgrow the high-producing cells, leading to a progressive decline in overall culture productivity [1]. Population control circuits address this by ensuring all cells transition synchronously from growth to production, often by using quorum-sensing systems that link the activation of the production pathway to cell density [1].

Circuit Design and Molecular Mechanisms

The implementation of population control typically relies on cell-cell communication systems. A common design utilizes elements from natural quorum-sensing pathways, where a signaling molecule (e.g., AHL) accumulates in the medium proportionally to cell density [1]. At a critical threshold concentration, the signal is detected by a transcriptional regulator, which then activates the expression of the heterologous production genes across the entire population simultaneously. This ensures that no individual cell gains a fitness advantage by delaying production, thereby stabilizing the culture's phenotype and protecting productivity over extended fermentation times [1].

Figure 2: Logic of a population-based control strategy using quorum sensing to synchronize the metabolic state of all cells in a culture.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical-Inducible Promoters | Enable external, manual control of gene expression. | aTc/IPTG systems (E. coli); GAL system (yeast); cost can be prohibitive at scale [10]. |

| Physical-Inducible Promoters | Enable external control without chemical cost; offer high temporal precision. | PR/PL (temperature); EL222/Pc120 (blue light); suboptimal temperatures can affect native metabolism [10]. |

| Transcription Factor (TF)-Based Biosensors | Core component for continuous control; senses metabolite and regulates transcription. | Naturally-derived (e.g., FapR for malonyl-CoA) or engineered TFs; specificity and dynamic range are key parameters [13]. |

| Quorum-Sensing Modules | Enables population-level synchronization of behavior. | LuxI/LuxR (AHL systems) from V. fischeri; used to tie production onset to cell density [1]. |

| Host-Aware Model Frameworks | Computational design to predict strain performance & resource competition. | Models capturing metabolism & gene expression; used for in silico optimization of enzyme expression levels [11]. |

| Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) Libraries | Fine-tune translation initiation rates for balanced enzyme expression. | Used to optimize the expression levels of multiple enzymes in a pathway without changing promoters [11]. |

The theoretical frameworks of two-stage, continuous, and population-based control represent a sophisticated toolkit for addressing the fundamental challenges of metabolic engineering. Two-stage control provides a straightforward method to decouple growth and production, continuous control enables intelligent, real-time self-optimization, and population control ensures robust, synchronized performance at the culture level. The choice of framework depends on the specific metabolic challenge, host organism, and process requirements. Future advancements will likely involve integrating these strategies into more complex, multi-layered control systems and expanding the library of robust, well-characterized biosensors and genetic parts to reliably implement these theoretical designs in industrial production strains [1] [10].

Metabolic engineering research is increasingly dynamic, moving beyond static genetic modifications to embrace approaches that sense and respond to cellular physiology in real-time. This paradigm shift is crucial for addressing the core biological challenges that hinder the industrial production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and specialty chemicals. These challenges—metabolic imbalances, product toxicity, and inherently low yields—are interconnected barriers that often undermine the economic viability of biologically engineered processes [14]. Metabolic imbalances occur when engineered pathways disrupt the host's native metabolism, leading to cofactor depletion, accumulation of intermediate metabolites, and suboptimal flux toward the desired product [15]. Product toxicity, particularly relevant in biofuel production where compounds like butanol can disrupt cellular membranes, limits the final achievable titer [14] [15]. Meanwhile, low yields stemming from inefficient substrate conversion and carbon loss through competing pathways remain a fundamental constraint across applications [16] [17].

Dynamic metabolic engineering represents the vanguard of this field, employing synthetic biology tools to create intelligent systems that automatically regulate metabolic flux in response to changing intracellular conditions [18]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of the strategies, tools, and methodologies being deployed to overcome these persistent challenges, with a particular focus on their implementation within the context of biofuel and bioproduct synthesis. Through advanced computational models, innovative genetic circuits, and protein engineering, researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated solutions that maintain cellular homeostasis while maximizing production efficiency.

Computational Design and Modeling for Pathway Balancing

Genome-Scale Modeling and Quality Control

The foundation of modern metabolic engineering lies in computational design, which enables the prediction of metabolic behaviors before laboratory implementation. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) mathematically represent an organism's entire metabolic network, integrating genomic annotation with biochemical knowledge [17] [19]. These models allow researchers to simulate cellular metabolism under different genetic and environmental conditions using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which calculates flow of metabolites through biochemical networks by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass or product formation) within physicochemical constraints [17] [19].

A significant advancement in this area is the development of the Cross-Species Metabolic Network (CSMN) model and the Quantitative Heterologous Pathway Design algorithm (QHEPath). This integrated system addresses a critical challenge: the inherent errors in universal models that can lead to biologically impossible predictions, such as infinite metabolite generation. The quality-control workflow for CSMN employs parsimonious enzyme usage FBA (pFBA) to iteratively identify and remove reactions causing network inconsistencies, ensuring calculated maximum yields align with biochemical feasibility [17]. In a comprehensive evaluation of 12,000 biosynthetic scenarios across 300 products, this approach revealed that over 70% of product pathway yields could be improved by introducing appropriate heterologous reactions, identifying 13 distinct engineering strategies categorized as carbon-conserving and energy-conserving [17].

Pathway Prospecting and Algorithmic Design

Computational tools have evolved from descriptive models to prescriptive design platforms. The QHEPath algorithm specifically addresses the challenge of identifying heterologous reactions that break the stoichiometric yield limits of native host metabolism [17]. Unlike earlier tools like OptStrain, QHEPath distinguishes between reactions necessary for pathway functionality and those specifically responsible for enhancing yield beyond native constraints, enabling more targeted engineering strategies [17].

Table 1: Computational Tools for Metabolic Network Reconstruction and Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application in Metabolic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| QHEPath | Quantitative heterologous pathway design | Identifies yield-enhancing reactions; web server interface | Breaking stoichiometric yield limits in host organisms [17] |

| Model SEED | High-throughput model reconstruction | Integrates genome annotations, gap analysis, thermodynamics | Automated generation of genome-scale metabolic models [7] |

| BiGG Database | Curated metabolic reconstructions | Mass and charge balanced reactions; gene-protein-reaction associations | Reference database for high-quality network models [17] [7] |

| KEGG Pathway | Metabolic pathway reference | Manually drawn reference pathways; KGML export format | Comparative analysis and pathway visualization [7] |

| MetaCyc | Metabolic pathway database | Organism-specific pathway diagrams; literature references | Enzyme and reaction information for pathway design [7] |

Standardized representation formats are crucial for tool interoperability. The Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) has emerged as the common format for representing metabolic pathway models, with 222 supporting tools as of recent counts [7]. Complementary standards like the Systems Biology Ontology (SBO) and Biological Pathway Exchange (BioPAX) language enable precise semantic annotation of pathway components, facilitating accurate knowledge exchange between databases and analytical tools [7].

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for Metabolic Engineering. The process begins with objective definition and proceeds through data gathering, model reconstruction, quality control, computational analysis, and experimental validation in an iterative cycle.

Dynamic Regulation Strategies for Metabolic Balance

Quorum Sensing-Controlled CRISPRi Systems

Dynamic regulation represents a paradigm shift from static metabolic engineering toward responsive systems that automatically adjust metabolic flux based on cellular physiology. A recent groundbreaking approach integrates quorum sensing (QS) with CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to create a QS-controlled Type I CRISPRi (QICi) toolkit that modulates gene expression in response to cell density [18]. This system utilizes the native bacterial communication mechanism where cells produce and detect signaling molecules called autoinducers. As cell density increases, autoinducer concentration rises, triggering population-wide changes in gene expression [18].

In the optimized QICi system, key components PhrQ and RapQ were engineered to achieve a twofold enhancement in regulation efficacy [18]. When applied to Bacillus subtilis for d-pantothenic acid (DPA) biosynthesis, dynamic regulation of the citrate synthase gene citZ enabled automatic redirection of metabolic flux toward product formation during high-cell-density fermentation. Combined with pantoate pathway engineering, cofactor supply enhancement, and sporulation suppression, this approach achieved remarkable titers of 14.97 g/L in 5-L fed-batch fermentations without precursor supplementation [18]. Similarly, QICi-mediated metabolic rewiring of key nodes boosted riboflavin production by 2.49-fold, demonstrating the broad applicability of this dynamic control strategy [18].

Cofactor Engineering and Redox Balancing

Cofactor imbalance represents a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering, particularly when engineered pathways impose unnatural demands on the host's redox state. The redox cofactors NADH and NADPH serve as essential electron carriers in cellular metabolism, and imbalances can severely limit pathway efficiency [15]. Several innovative strategies have emerged to address this challenge:

Noncanonical cofactor utilization represents a promising approach for bypassing native regulatory constraints. By engineering pathways to use alternative cofactors like NADH instead of NADPH, or vice versa, engineers can circumvent competition with native metabolism and drive flux toward desired products [15]. For n-butanol production, this strategy has shown particular promise, with protein engineering of enzymes like aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase (ADHE2) enabling improved coupling with preferred cofactor pools [15].

Cofactor regeneration systems create synthetic cycles that maintain optimal cofactor ratios. For example, the expression of transhydrogenase genes (pntAB) enables interconversion between NADH and NADPH, preventing depletion of either cofactor pool [14]. In E. coli engineered for biofuel production, this approach helped alleviate NADPH depletion caused by furfural toxicity, restoring sulfate assimilation and growth under inhibitory conditions [14].

Table 2: Dynamic Regulation Tools and Their Applications

| Regulation System | Key Components | Induction Mechanism | Documented Applications | Performance Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QICi Toolkit | PhrQ, RapQ, CRISPRi | Cell density (Quorum Sensing) | d-pantothenic acid, riboflavin production | 14.97 g/L DPA; 2.49x riboflavin increase [18] |

| NAD(P)H Regeneration | Transhydrogenase (pntAB) | Cofactor imbalance | Furfural tolerance in E. coli | Restored growth under inhibitor conditions [14] |

| Noncanonical Cofactor Systems | Engineered dehydrogenases | Pathway demand | n-butanol production | Improved yield and titer [15] |

Overcoming Product Toxicity and Inhibitor Effects

Membrane Stress and Solvent Tolerance

Product toxicity presents a fundamental limitation in biofuel production, where compounds like n-butanol disrupt cellular membranes and inhibit growth at concentrations as low as 2% [15]. Clostridium acetobutylicum, a native butanol producer, has been extensively engineered to enhance tolerance through both evolutionary and targeted approaches. Adaptive laboratory evolution of strain JB200 generated mutants capable of producing 20.3 g/L butanol with a yield of 0.23 g/g glucose [15]. Targeted knockout of the cac3319 gene further enhanced tolerance, enabling production of 18.2 g/L [15].

The toxicity challenge extends beyond final products to inhibitors present in lignocellulosic hydrolysates, the primary feedstocks for advanced biofuels. Pretreatment of lignocellulose generates compounds like furfural, hydroxymethyl furfural (HMF), and phenolic compounds that inhibit microbial growth and fermentation [14]. Furfural is particularly problematic as it induces reactive oxygen species and depletes NADPH through the activity of NADPH-dependent oxidoreductases like YqhD [14]. Strategic engineering of E. coli involving deletion of yqhD coupled with cysteine supplementation significantly enhanced furfural tolerance [14]. Similarly, overexpression of alternative oxidoreductases like FucO provided reduction capacity without NADPH depletion, offering another effective tolerance mechanism [14].

Efflux Systems and In Situ Product Removal

Engineering active efflux systems represents a promising strategy for mitigating intracellular toxin accumulation. While not explicitly detailed in the search results, the principle involves overexpression of transporter proteins that actively export toxic compounds from cells. When combined with in situ product removal (ISPR) technologies, this approach can significantly enhance overall production. For example, in vacuum-assisted fermentation of C. acetobutylicum strain CAB1060, continuous butanol removal enabled unprecedented titers of 550 g/L with a yield of 0.35 g/g glucose and productivity of 14 g/L/h [15]. This demonstrates how integrated bioprocessing strategies can overcome toxicity limitations that are insurmountable through genetic engineering alone.

Figure 2: Product Toxicity Challenges and Engineering Solutions. Toxicity mechanisms (red) include membrane disruption, oxidative stress, cofactor depletion, and enzyme inhibition. Engineering solutions (green) provide targeted mitigation strategies.

Yield Enhancement Through Pathway Optimization

Non-Oxidative Glycolysis and Carbon Conservation

Yield enhancement represents the ultimate goal of metabolic engineering, with carbon efficiency directly impacting economic viability. A powerful strategy involves implementing non-oxidative glycolysis (NOG) pathways that break native stoichiometric yield limits [17]. Unlike conventional glycolysis that loses carbon as CO₂, NOG enables complete carbon conservation, theoretically allowing 100% of substrate carbon to be converted to products. Implementation of NOG in E. coli significantly enhanced poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) yield beyond native network constraints [17]. Similarly, the yield of farnesene was dramatically improved through NOG incorporation [17].

The CSMN model and QHEPath algorithm have systematically categorized thirteen engineering strategies for yield enhancement, with five strategies effective for over 100 different products [17]. These approaches can be broadly classified as carbon-conserving and energy-conserving strategies. Carbon-conserving approaches focus on minimizing CO₂ loss and maximizing atom economy, while energy-conserving strategies optimize ATP and reducing equivalent utilization throughout the metabolic network [17].

Systems-Level Pathway Engineering

Comprehensive pathway engineering at the systems level has produced remarkable yield improvements in industrial microorganisms. A landmark achievement in C. acetobutylicum involved extensive genome rewriting combining multiple gene deletions and heterologous gene substitutions [15]. Key modifications included:

- Knockout of ptb (phosphotransbutyrylase) and buk (butyrate kinase) to eliminate competitive butyrate biosynthesis

- Deletion of ldhA to prevent lactate formation

- Knockout of ctfAB to eliminate acetone production

- Deletion of rexA, a redox-sensing transcriptional regulator that represses C4 pathway genes

- Gene substitutions including ΔthlA::atoB (incorporating acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase from E. coli) and Δhbd::hbd1 (NADPH-dependent 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase from C. kluveri) [15]

This systems-level engineering resulted in a strain capable of producing 550 g/L n-butanol in fed-batch fermentation with in-situ product recovery, achieving a yield of 0.35 g/g glucose and remarkable productivity of 14 g/L/h [15].

Table 3: Representative Yield Enhancements in Biofuel Production

| Product | Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Yield Achieved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Butanol | C. acetobutylicum CAB1060 | Multiple gene knockouts, heterologous gene expression, in-situ separation | 0.35 g/g glucose | [15] |

| Biodiesel | Engineered microbes | Lipid pathway optimization, transesterification | 91% conversion efficiency | [16] |

| Ethanol | S. cerevisiae | Xylose utilization pathway engineering | ~85% xylose conversion | [16] |

| n-Butanol | Engineered C. tyrobutyricum | adhE2 overexpression in Ack strain | 0.27 g/g glucose | [15] |

| n-Butanol | Engineered E. coli | Balanced pathway expression, cofactor engineering | 0.34 g/g glucose | [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Implementation of QS-Controlled CRISPRi

The QS-controlled Type I CRISPRi (QICi) system provides a robust methodology for dynamic metabolic regulation. The following protocol outlines key implementation steps:

Vector Construction and Optimization:

- crRNA Array Design: Clone CRISPR RNA (crRNA) sequences targeting genes of interest into expression vectors under constitutive promoters. Streamline construction using Golden Gate assembly or similar modular cloning techniques [18].

- QS Component Engineering: Optimize expression levels of key quorum sensing components PhrQ and RapQ. In the published system, this optimization yielded a twofold enhancement in QICi efficacy [18].

- Integration Cassette Assembly: Combine optimized QS components with CRISPRi machinery in a single regulatory circuit.

Strain Engineering and Validation:

- Chromosomal Integration: Introduce the QICi cassette into the host chromosome at a neutral site or via replacement of target metabolic genes.

- Circuit Characterization: Validate system responsiveness by measuring gene expression dynamics across growth phases using qRT-PCR or reporter genes.

- Fermentation Optimization: Implement controlled fed-batch processes with careful monitoring of cell density and product formation. For DPA production, this approach achieved 14.97 g/L in 5-L fermenters [18].

Protocol: Metabolic Flux Analysis Using Isotopic Tracers

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) provides critical insights for identifying pathway bottlenecks and quantifying metabolic fluxes:

Tracer Experiment Design:

- Substrate Selection: Prepare labeled substrates (e.g., U-¹³C glucose or 1-¹³C glucose) with purity >99% atom percent ¹³C.

- Cultivation Conditions: Grow engineered strains in controlled bioreactors with defined medium, switching to labeled substrate during mid-exponential phase.

- Sampling Protocol: Collect samples at multiple timepoints for extracellular metabolites, biomass, and isotope labeling measurements.

Analytical Procedures:

- GC-MS Analysis: Derivatize intracellular metabolites and analyze by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to determine mass isotopomer distributions.

- NMR Spectroscopy: Complement GC-MS data with ¹³C-NMR for positional labeling information.

- Flux Calculation: Use computational software such as INCA or OpenFlux to simulate labeling patterns and calculate metabolic flux distributions [19].

Model Validation:

- Statistical Analysis: Apply χ²-test and Monte Carlo analysis to evaluate goodness-of-fit between simulated and measured labeling patterns.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify reactions with high flux confidence intervals to pinpoint targets for further engineering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TALEN, ZFN | Precise genome modifications | CRISPR-Cas9 uses 20-nt guide RNA for targeting [16] [14] |

| Quorum Sensing Components | PhrQ, RapQ | Cell-density responsive regulation | Optimization enhanced QICi efficacy 2-fold [18] |

| Computational Algorithms | QHEPath, OptStrain | Pathway design and yield prediction | QHEPath identifies yield-enhancing reactions [17] |

| Metabolic Databases | BiGG, KEGG, MetaCyc | Metabolic network information | BiGG provides curated, balanced models [17] [7] |

| Cofactor Engineering Enzymes | Transhydrogenase (pntAB) | NADH/NADPH balancing | Addresses cofactor imbalance issues [14] |

| Tolerance Engineering Tools | FucO, YqhD oxidoreductases | Detoxification of inhibitors | FucO overexpression enhances furfural tolerance [14] |

The field of dynamic metabolic engineering has evolved sophisticated strategies to address the fundamental challenges of metabolic imbalances, product toxicity, and low yields. Through integrated computational and experimental approaches, researchers can now design self-regulating systems that maintain cellular homeostasis while maximizing production. The convergence of responsive genetic circuits, advanced modeling algorithms, and systems-level pathway optimization represents a new paradigm in metabolic engineering—one that moves beyond static designs toward dynamically controlled networks capable of adapting to changing metabolic demands. As these tools become more sophisticated and accessible, they promise to accelerate the development of efficient microbial cell factories for sustainable chemical production, ultimately bridging the gap between laboratory promise and industrial implementation.

The Dynamic Engineering Toolkit: Biosensors, Circuits, and Real-World Applications

Dynamic metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift in the development of microbial cell factories. Unlike traditional approaches that involve static genetic modifications, dynamic metabolic engineering employs synthetic genetic circuits to enable real-time control of metabolic fluxes, allowing microbial systems to autonomously respond to metabolic states and environmental changes. This sophisticated approach is essential because the synthesis efficiency of most microbial cell factories remains low despite advances in metabolic engineering tools, with one major limiting factor being the inability to dynamically control metabolic fluxes in response to pathophysiological conditions [20]. Genetic circuits address this limitation by providing a versatile toolbox for automated control of metabolic networks and high-throughput screening of overproducers, ultimately balancing the critical trade-off between cell growth and product synthesis [20] [21].

The core architecture of these synthetic biological systems consists of molecular sensors that detect intracellular metabolites or external signals, actuators that execute regulatory functions, and circuit logic that processes information to determine appropriate cellular responses. This framework allows engineers to program living cells for advanced applications ranging from living therapeutics to the atomic manufacturing of functional materials [21]. As the field matures, increasing emphasis is being placed on creating robust and predictable systems through careful characterization of parts, adherence to engineering principles, and computational approaches for automated design [22].

Molecular Sensors: Detection and Signal Transduction

Molecular sensors serve as the critical interface between the cellular state and the synthetic genetic circuit, providing the essential input data upon which regulatory decisions are made. These sophisticated biological components detect a wide array of signals, including metabolic intermediates, external inducers, and physical environmental parameters.

Transcriptional Biosensors

Transcriptional biosensors represent one of the most well-established sensor classes in synthetic biology. These systems typically employ transcription factors that undergo conformational changes upon binding specific ligands, leading to activation or repression of downstream promoter elements. Natural metabolite-responsive regulators such as FapR (for fatty acid synthesis) and TyrP (for aromatic amino acids) have been successfully exploited for dynamic metabolic control [20]. The key advantage of transcriptional biosensors lies in their direct connection to gene expression, enabling immediate regulatory responses to metabolic changes. Recent advances have focused on expanding the biosensor repertoire through mining of microbial genomes and engineering of transcription factors with altered ligand specificity [20].

RNA-Based Sensors

RNA-based sensors, including riboswitches and toehold switches, provide an alternative sensing mechanism that operates at the transcriptional and translational levels without protein intermediaries. These systems typically undergo structural rearrangements upon ligand binding, modulating accessibility to ribosome binding sites or ribonuclease cleavage sites. The recently developed RAVEN (RNA-based Vienna Ensemble) platform exemplifies how computational models can predict RNA conformational changes for biosensor design [20]. RNA sensors offer advantages in response speed and reduced metabolic burden, as they function without requiring protein synthesis. Furthermore, their computational designability makes them particularly amenable to creating orthogonal sensor families for multiple intracellular metabolites [20] [22].

Optogenetic and Mechanosensitive Systems

Beyond chemical sensing, genetic circuits can incorporate physical signal sensors that respond to light, temperature, or mechanical stimuli. Optogenetic systems, utilizing light-sensitive domains from plants or microbial opsins, provide exceptional spatiotemporal control of metabolic processes [20] [22]. These systems are particularly valuable in bioprocessing contexts where precise induction timing is critical but chemical inducers would be impractical or costly. Similarly, temperature-sensitive variants of natural proteins can be engineered to create thermal biosensors that trigger metabolic reprogramming at specific cultivation temperatures [20].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Molecular Sensor Classes

| Sensor Class | Detection Mechanism | Response Time | Key Applications | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Biosensors | Transcription factor-ligand binding | Minutes to hours | Metabolite sensing, metabolic pathway regulation | Specificity, dynamic range, host compatibility |

| RNA-Based Sensors | RNA conformational changes | Seconds to minutes | High-throughput screening, real-time metabolite monitoring | Orthogonality, prediction accuracy, sequence constraints |

| Optogenetic Systems | Light-sensitive protein domains | Seconds to minutes | Spatiotemporal control, fermenter-scale applications | Light penetration, hardware requirements, background sensitivity |

| CRISPR-Based Sensors | gRNA-dCas protein complexes | Minutes to hours | Multiplexed detection, logic operations | gRNA design, off-target effects, PAM sequence requirements |

Molecular Actuators: Genetic Circuit Outputs and Control Mechanisms

Molecular actuators constitute the functional output components of genetic circuits, executing the regulatory decisions determined by the circuit logic. These diverse protein systems enable precise control over metabolic pathway activity through targeted interventions at multiple levels of cellular information flow.

DNA-Binding Protein Actuators

DNA-binding proteins represent the most extensively characterized class of genetic circuit actuators. These include repressors that block RNA polymerase binding or progression, and activators that recruit RNA polymerase to specific promoters. Early genetic circuits relied on a limited set of well-characterized repressors such as CI, TetR, and LacI [21]. Recent efforts have significantly expanded this repertoire through discovery and engineering of zinc finger proteins (ZFPs), transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs), and novel TetR/LacI homologs [21] [22]. The primary advantage of DNA-binding protein actuators lies in their well-characterized quantitative relationship between input signal and transcriptional output, enabling predictive circuit design. Additionally, their modular nature facilitates the construction of chimeric proteins with novel DNA-binding specificities and regulatory functions [21].

RNA-Targeting Actuators

RNA-targeting actuators, particularly CRISPR-based systems, have revolutionized genetic circuit design through their unparalleled programmability and orthogonality. Catalytically inactive Cas proteins (dCas9, dCas12) can be directed to specific DNA sequences by guide RNAs, where they function as repressors (CRISPRi) by sterically blocking RNA polymerase [20] [21]. When fused to transcriptional activation domains, these same systems can function as potent activators (CRISPRa) [21]. The key advantage of RNA-targeting actuators is the ease of retargeting to new genomic loci simply by modifying the guide RNA sequence, eliminating the need for protein engineering. This programmability enables the construction of highly complex genetic circuits with dozens of orthogonal regulatory connections [21] [22].

Site-Specific Recombinases

Site-specific recombinases, including tyrosine recombinases (Cre, Flp) and serine integrases (Bxb1, PhiC31), provide a unique class of actuators that mediate permanent, heritable changes to DNA sequence [21] [22]. These systems function by catalyzing inversion, excision, or integration of specific DNA segments in response to regulatory signals. Recombinase-based actuators are particularly valuable for implementing biological memory, enabling circuits to "remember" past exposure to specific metabolites or environmental conditions [22]. This memory function can be leveraged to autonomously lock metabolic pathways into high-production states after appropriate cultivation conditions have been established. Furthermore, recombinases enable the construction of complex logic gates and state machines that can perform sophisticated computation and decision-making within living cells [21] [22].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Molecular Actuators

| Actuator Type | Regulatory Action | Response Dynamics | Orthogonality Potential | Metabolic Burden |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Repressors | Block transcription initiation | Rapid (minutes) | Moderate (10-20 variants) | Low to moderate |

| Transcriptional Activators | Enhance transcription initiation | Rapid (minutes) | Moderate (10-20 variants) | Low to moderate |

| CRISPRi/a Systems | Modulate transcription | Moderate (hours) | High (100+ variants) | Moderate to high |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | DNA rearrangement | Slow to permanent | High (10+ variants) | Transient during action |

| RNA Interference | Target mRNA degradation | Moderate (hours) | High (100+ variants) | Low |

Genetic Circuit Design Principles and Architecture

The design of effective genetic circuits for metabolic engineering requires systematic approaches that consider both the individual component characteristics and their integrated system behavior. Several key principles guide the construction of robust, predictable genetic circuits capable of implementing complex control functions.

Circuit Topologies for Metabolic Control

Different metabolic engineering challenges require distinct circuit architectures to achieve optimal control strategies. Negative feedback loops maintain metabolic homeostasis by reducing pathway expression when metabolite concentrations exceed a threshold, preventing toxic accumulation while maintaining flux [20]. Conversely, positive feedback loops can create bistable switches that lock metabolism into high-production states after an initial induction signal [21]. Feed-forward loops enable predictive control, activating stress response pathways before metabolic imbalances become critical [20]. For complex multi-pathway optimization, Boolean logic gates (AND, OR, NOT) allow integration of multiple metabolic signals to implement sophisticated expression control strategies [21] [22].

The design process for these circuits increasingly leverages computational tools including COPARI, OptRAM, and GDA (Genetic Design Automation) to predict circuit behavior and identify optimal component combinations [20]. These tools integrate kinetic parameters of biological parts with metabolic network models to simulate system performance before experimental implementation.

Figure 1: Genetic Circuit Topologies for Metabolic Control showing negative feedback, positive feedback, and feed-forward control architectures.

Experimental Protocol for Genetic Circuit Implementation

The implementation of functional genetic circuits requires meticulous experimental workflows spanning design, construction, and validation phases. The following protocol outlines key methodological steps for reliable circuit development:

Circuit Specification and Design: Define quantitative input-output relationships and dynamic performance requirements based on metabolic modeling. Select appropriate sensors, actuators, and circuit architecture using computational tools such as iBioSim 3 or GDA platforms [20].

DNA Assembly and Parts Characterization: Assemble genetic circuits using standardized modular cloning systems (Golden Gate, MoClo). Individually characterize each component's transfer function—measuring response dynamics, leakiness, dynamic range, and cell-to-cell variability [21].

Host Strain Engineering: Select appropriate microbial chassis (E. coli, B. subtilis, P. putida) based on metabolic capabilities and genetic tool availability. Modify host genome to remove interfering regulatory systems or to incorporate necessary helper functions [20].

Circuit Integration and Validation: Integrate assembled circuits into host strains and validate functionality using reporter systems (fluorescence, enzymatic assays). Measure circuit performance under controlled cultivation conditions, assessing both metabolic output and growth impacts [20] [21].

System Optimization: Iteratively refine circuit components to achieve desired performance. Implement "tuning knobs" such as RBS libraries, promoter variants, or protein degradation tags to adjust expression levels without redesigning circuit architecture [21].

Scale-up Evaluation: Test circuit performance across scales from microtiter plates to bioreactors, assessing robustness to heterogeneous environmental conditions and population effects [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Circuit Construction and Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Genetic Parts | Anderson promoter collection, Registry of Standard Biological Parts | Modular DNA elements for circuit construction | Characterization data, standardization, interoperability |

| DNA Assembly Systems | Golden Gate, MoClo, Gibson Assembly | Efficient combinatorial assembly of circuit variants | Standardized overhangs, scalability, reduced assembly scars |

| Reporter Systems | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP), luciferases, chromogenic enzymes | Quantitative measurement of circuit activity and dynamics | Different spectral properties, stability, detection sensitivity |

| Inducer Compounds | AHL, aTc, IPTG, arabinose | Controlled induction of circuit components | Specificity, cell permeability, cost, reversibility |

| Host Strain Libraries | E. coli MG1655, B. subtilis 168, P. putida KT2440 | Chassis organisms with varying metabolic and genetic backgrounds | Genetic stability, transformation efficiency, growth characteristics |

| CRISPR Tools | dCas9 variants, guide RNA libraries, base editors | Programmable transcriptional regulation and genome editing | Orthogonality, multiplexing capability, minimal off-target effects |

| Recombinase Systems | Cre, Flp, Bxb1, PhiC31 | DNA rearrangement for memory and state changes | Directionality, efficiency, orthogonality |

Integration with Dynamic Metabolic Engineering Frameworks

The true potential of genetic circuits is realized through their integration with dynamic metabolic engineering frameworks, where they serve as the central control systems governing microbial biocatalysts. This integration enables unprecedented capabilities for real-time metabolic optimization and robust bioprocess performance.

Dynamic Flux Control Strategies

Advanced genetic circuits implement dynamic flux control strategies that automatically redistribute metabolic resources between growth and production phases. For example, a circuit can maintain low pathway expression during rapid growth, then activate production pathways once biomass accumulation nears completion [20]. This approach was successfully demonstrated in E. coli for fatty-acid synthesis through dynamic control of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and for lactate synthesis via adenosine triphosphatase regulation [23]. The implementation typically involves metabolite biosensors that trigger expression of key pathway enzymes when specific metabolic intermediates reach threshold concentrations, creating self-regulating production systems [20] [23].

Machine Learning for Circuit Optimization

The optimization of genetic circuits for metabolic engineering is increasingly leveraging machine learning approaches, particularly reinforcement learning. These methods can identify optimal dynamic control policies by interacting with surrogate dynamic models of the metabolic system [23]. The reinforcement learning framework allows controllers to generalize across uncertainties through domain randomization, enhancing robustness when transferred to experimental systems [23]. This approach provides a powerful alternative to conventional model-based control strategies like model predictive control, as it requires only forward integration of the model rather than differentiation with respect to decision variables—a particular advantage for complex stochastic, nonlinear, and stiff systems typical of cellular metabolism [23].