Dynamic Metabolic Regulation: Advanced Biosensor Design for Pathway Optimization and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transcription factor-based and nucleic acid-based biosensors for dynamic control of metabolic pathways.

Dynamic Metabolic Regulation: Advanced Biosensor Design for Pathway Optimization and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of transcription factor-based and nucleic acid-based biosensors for dynamic control of metabolic pathways. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational principles, advanced methodologies including extended metabolic biosensors and bifunctional circuits, and optimization strategies to overcome stability and robustness challenges. The content further covers validation techniques through comparative analysis and high-throughput screening, synthesizing key insights to outline future directions for clinical translation and therapeutic development.

Core Principles and Natural Paradigms of Metabolic Biosensing

Fundamental Principles and Native Regulatory Roles

Transcription factor-based biosensors (TFBs) are genetically encoded devices that utilize allosteric transcription factors (aTFs) to detect specific small molecules and regulate gene expression in response [1] [2]. In their native biological contexts, aTFs function as fundamental molecular switches within cellular regulatory networks, allowing organisms to adapt to environmental changes by modulating gene expression [1].

These biosensors operate through a simple yet powerful mechanism: the sensing aTF undergoes a conformational change upon binding its target ligand (effector molecule). This allosteric change alters the TF's affinity for specific DNA operator sequences, thereby activating or repressing transcription of downstream genes [2]. The relationship between the effector molecule and the aTF defines its mode of action, which can include repression of activator aTF, activation of repressor aTF, repression of repressor aTF, or activation of activator aTF [1].

Native aTFs play crucial roles in various physiological processes. For instance, in bacteria, they regulate responses to metabolic intermediates, environmental stressors, and signaling molecules. The MerR family TFs, such as MerR and ArsR, respond to heavy metals like mercury and arsenic by modulating expression of detoxification genes [2]. LuxR, a quorum-sensing TF, recognizes acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) to coordinate population-level behaviors [2]. These natural regulatory systems provide the foundational components for engineering synthetic biosensing circuits.

Table 1: Native Biological Roles of Selected Bacterial Transcription Factors

| Transcription Factor | Native Ligand/Effector | Native Regulatory Role | Organism Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ArsR | Arsenic compounds | Activates arsenic detoxification and efflux pathways [2] | Various bacteria |

| MerR | Mercury ions | Regulates mercury resistance operon [2] | Various bacteria |

| LuxR | Acyl-Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) | Controls quorum-sensing and virulence genes [2] | Vibrio fischeri and others |

| TtgR | Flavonoids, antibiotics [3] | Represses multidrug efflux pump expression [3] | Pseudomonas putida |

| MntR | Manganese | Regulates manganese homeostasis [2] | Various bacteria |

Quantitative Characterization of Biosensor Performance

The performance of TF-based biosensors is quantitatively evaluated using several key parameters essential for their application in dynamic metabolic regulation. The dynamic range refers to the fold-change in reporter gene expression between the presence and absence of the inducing ligand, which directly impacts the biosensor's output signal strength [2]. Sensitivity is defined by the lowest ligand concentration that elicits a detectable response, often measured as the EC50 or half-maximal effective concentration [4]. Specificity describes the biosensor's ability to distinguish the target ligand from structurally similar molecules, a critical factor in complex cellular environments [4] [3].

Recent advances in biosensor engineering have significantly improved these parameters. For example, a study developing phenolic acid biosensors established response and sensitivity landscapes for eleven different inducers, with dynamic ranges varying significantly across different sensor-inducer pairs [4]. The Sensor-seq platform enabled the design of TtgR-based biosensors for non-native ligands including tamoxifen derivatives, quinine, and naltrexone, achieving high dynamic range and diverse specificity profiles [3].

Table 2: Key Performance Parameters for Biosensor Characterization

| Performance Parameter | Definition | Measurement Approach | Target Values for Effective Biosensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Range | Fold-change in output signal between induced and uninduced states [2] | Ratio of maximum output to basal leakage | >10-fold (highly desirable) |

| Sensitivity (EC50) | Ligand concentration producing half-maximal response [4] | Dose-response curve fitting | Low µM to nM range (context-dependent) |

| Specificity/Cross-Reactivity | Response to target ligand relative to similar compounds [4] | Screening against ligand panels | Minimal cross-talk with pathway intermediates |

| Orthogonality | Function without interference from host regulatory networks [1] | Testing in different host backgrounds | Minimal host-dependent performance variation |

| Response Time | Time required to reach significant output after induction | Kinetic monitoring | Minutes to hours (application-dependent) |

Experimental Protocol: Implementation of a Phenolic Acid Biosensor

This protocol details the implementation of a biosensor for protocatechuic acid (PCA), based on a identified transcription factor-inducible promoter pair, for high-throughput screening as described by [4].

Materials and Equipment

- Bacterial Strains: Escherichia coli DH10B or other appropriate host strains

- Plasmid Vector: Low-copy number plasmid with multiple cloning site

- Reporter Gene: GFP, RFP, or an antibiotic resistance gene

- Inducer Stock Solutions: 100 mM protocatechuic acid in DMSO or buffer

- Growth Media: LB or M9 minimal media with appropriate antibiotics

- Equipment: Microplate reader, flow cytometer, or spectrophotometer

Procedure

Day 1: Strain Preparation

- Transform the biosensor plasmid into the selected E. coli host strain using standard transformation protocols.

- Plate transformed cells on LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Day 2: Culture Inoculation

- Pick single colonies to inoculate 2 mL liquid cultures with antibiotics.

- Grow overnight at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm.

Day 3: Biosensor Assay

- Dilute overnight cultures 1:100 in fresh medium with antibiotics.

- Aliquot 200 µL of diluted culture into a 96-well microplate.

- Add protocatechuic acid to final concentrations ranging from 0 µM to 1000 µM (include DMSO-only vehicle controls).

- Incubate the microplate at 37°C with continuous shaking in a microplate reader.

- Measure optical density (OD600) and fluorescence (excitation/emission appropriate for reporter) every 30 minutes for 12-16 hours.

Day 4: Data Analysis

- Normalize fluorescence measurements to cell density (fluorescence/OD600).

- Calculate fold-induction by dividing normalized fluorescence in induced conditions by that in uninduced controls.

- Plot dose-response curves and calculate EC50 values using appropriate software.

Troubleshooting Notes

- High Background Signal: Optimize promoter strength or RBS sequences to reduce basal expression [2].

- Low Dynamic Range: Test different reporter genes or consider engineering the TF DNA-binding site [2].

- Variable Response: Ensure consistent growth conditions and cell density at induction.

Experimental Protocol: Sensor-seq for High-Throughput Biosensor Screening

This protocol outlines the Sensor-seq method for massively parallel screening of aTF variants, enabling identification of biosensors for non-native ligands [3].

Materials and Equipment

- Library Construction: Oligonucleotide pool encoding aTF variants, Golden Gate Assembly reagents

- Barcoding System: Randomized 16N barcode sequences

- Screening: RNA stabilization reagents, RNA extraction kit, cDNA synthesis kit

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing platform (Illumina)

- Ligands: Target ligands of interest and appropriate vehicle controls

Procedure

Stage 1: Library Construction and Barcoding

- Design a mutagenesis library targeting the ligand-binding domain of selected aTF scaffold (e.g., TtgR).

- Construct plasmid library where each aTF variant is paired with random barcodes in the reporter transcript.

- Transform library into host cells and ensure sufficient coverage (>1000x library diversity).

Stage 2: Pooled Screening with Ligands

- Divide the library culture into aliquots for each test ligand and vehicle control.

- Treat with target ligands (e.g., 1 mM naltrexone, quinine) or vehicle control during mid-log phase.

- Incubate for precisely 2 hours to allow transcriptional response.

- Harvest cells and stabilize RNA immediately.

Stage 3: RNA Sequencing and Analysis

- Extract total RNA and prepare cDNA libraries.

- Perform deep sequencing of barcode regions from both cDNA (reporter expression) and plasmid DNA (variant abundance).

- Calculate F-scores for each variant: Normalized ratio of reporter transcript levels (ligand+/ligand-).

- Identify functional biosensors based on F-score threshold (typically >2-3 fold induction).

Data Interpretation

- Variants with F-scores ~1 are constitutively ON or OFF and should be discarded.

- Variants with F-scores >1 in ligand-treated conditions are potential hits.

- Validate top hits using clonal assays (e.g., flow cytometry, qRT-PCR).

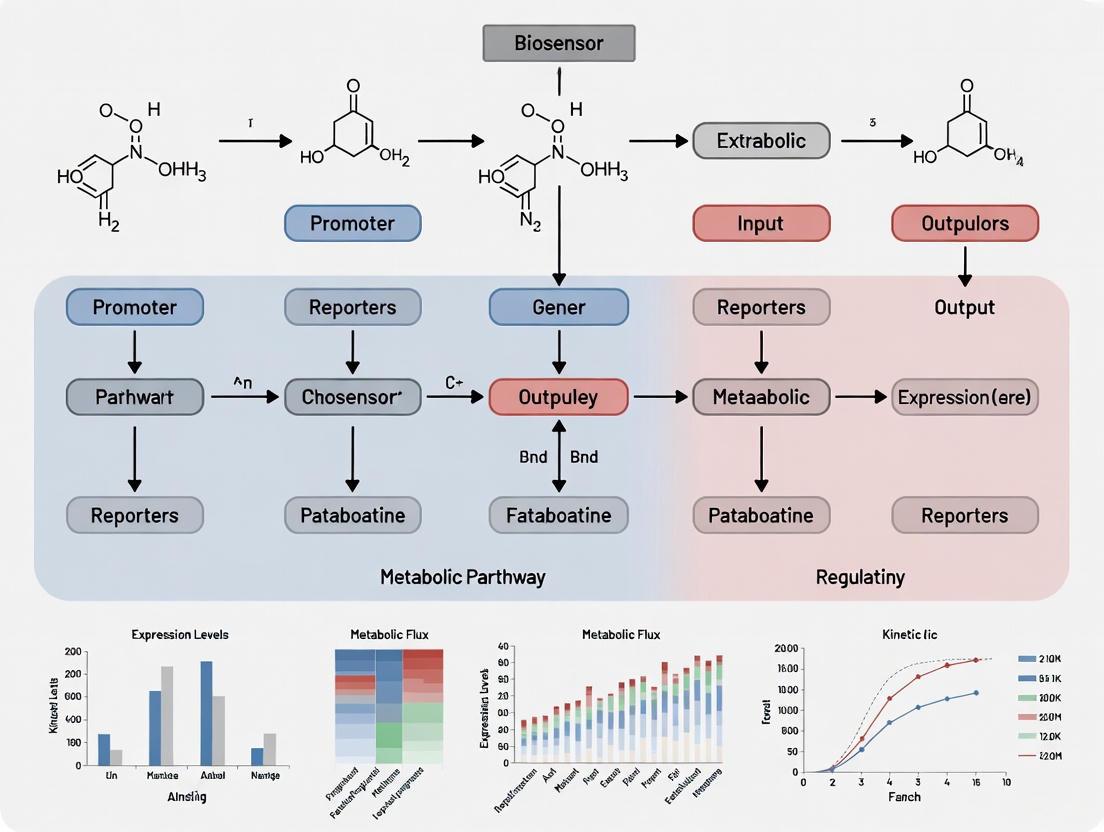

Visualizing Biosensor Mechanisms and Workflows

Biosensor Mechanism

Sensor-seq Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for TFB Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Scaffolds | TtgR, TetR, AraC, LuxR [1] [3] | Protein scaffolds for engineering ligand specificity |

| Reporter Genes | GFP, RFP, LacZ, Luciferase [2] | Quantifiable output for biosensor response |

| Host Strains | E. coli, P. putida, C. necator [4] | Chassis for biosensor implementation and testing |

| Database Resources | RegulonDB, PRODORIC, GroovDB [1] [3] | Curated information on natural TF-regulatory networks |

| Library Construction Tools | Golden Gate Assembly, Oligo pools [3] | High-throughput variant generation |

| Screening Methods | Sensor-seq, FACS, microplate readers [4] [3] | Identification and characterization of functional biosensors |

| (R)-Desmethylsibutramine hydrochloride | (R)-Desmethylsibutramine hydrochloride, CAS:259731-40-3, MF:C16H25Cl2N, MW:302.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6(5H)-Phenanthridinone, 2-bromo- | 6(5H)-Phenanthridinone, 2-bromo-, CAS:27353-48-6, MF:C13H8BrNO, MW:274.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Dynamic control of metabolic pathways is essential for developing efficient microbial cell factories, moving beyond traditional static regulation that often leads to metabolic imbalances and suboptimal productivity [5] [6]. Nucleic acid-based biosensors—specifically riboswitches, aptamers, and ribozymes—have emerged as powerful tools for real-time metabolic monitoring and regulation. These RNA elements provide a compact, protein-independent means of sensing intracellular metabolites and dynamically controlling gene expression, offering significant advantages in applications ranging from high-throughput strain screening to intelligent metabolic pathway control [7] [5]. Their modular nature, minimal metabolic burden, and ability to be integrated into complex genetic circuits make them particularly valuable for optimizing the production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and fine chemicals [8] [9].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Nucleic Acid-Based Biosensors

| Biosensor Type | Sensing Principle | Dynamic Range | Response Time | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riboswitches | Ligand-induced RNA conformational change affects translation | Tunable, up to ~14-fold gain [10] | Fast, reversible | Compact; integrates well into metabolic regulation [5] |

| Aptamers | Ligand binding to structured RNA/DNA elements | Varies by design (e.g., KD = 0.1 µM for theophylline aptamer) [10] | Rapid | High specificity; selectable via SELEX for diverse targets [10] |

| Ribozymes/Aptazymes | Self-cleaving catalytic RNA controlled by ligand binding | High (e.g., ~90% reduction in GFP expression) [10] | Very fast | Cis-acting; minimal off-target effects [7] |

| Toehold Switches | Base-pairing with trigger RNA activates translation | High specificity; programmable | Fast | Enables logic-based pathway control [5] |

Fundamental Mechanisms and Molecular Design

Riboswitch Architecture and Operating Principles

Riboswitches are structured non-coding RNA elements typically 34–200 nucleotides long, located in untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNA [8]. They consist of two primary domains: a sensing aptamer domain that binds specific ligands with high affinity and specificity, and an expression platform that regulates gene expression in response to ligand-induced conformational changes [7] [8]. This modular architecture allows riboswitches to control various post-transcriptional processes including translation initiation, mRNA stability, and transcription termination [7]. Natural riboswitches have been identified that respond to fundamental metabolites including nucleotides (guanine, adenine), amino acids (lysine, glycine, glutamine), enzyme cofactors (thiamine pyrophosphate, FMN, tetrahydrofolate), and ions (fluoride) [11]. The binding of these ligands induces structural rearrangements in the RNA that ultimately determine the regulatory outcome.

Aptamer Recognition and Ribozyme Catalysis

Aptamers are structured nucleic acid sequences (typically 30-80 nucleotides) that bind specific molecular targets with high affinity and selectivity, often rivaling antibodies [10] [12]. They are typically generated through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential Enrichment (SELEX), an iterative in vitro selection process that can yield binders for virtually any target molecule [7] [8]. The canonical theophylline aptamer, for instance, features a core of fifteen conserved residues organized into two internal loops that undergo conformational changes upon drug binding, with dissociation constants (K_D) in the micromolar range [10].

Ribozymes are catalytic RNA molecules that catalyze biochemical reactions, particularly the cleavage and ligation of phosphodiester bonds [10] [12]. When aptamers are fused to these self-cleaving RNA structures, they form aptazymes (allosteric ribozymes) whose catalytic activity becomes controlled by ligand binding [10]. Commonly used ribozyme scaffolds include hammerhead ribozymes (HHR), hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozymes, and glmS ribozymes [10] [12]. The modular nature of aptazymes enables the construction of sophisticated regulatory devices that respond to intracellular metabolite concentrations.

Figure 1: Aptazyme Architecture. Aptamers fused to ribozymes create ligand-responsive aptazymes for metabolic control.

Application Notes: Implementation in Metabolic Engineering

Dynamic Pathway Regulation

Nucleic acid biosensors enable autonomous control of metabolic fluxes by responding to intracellular metabolite levels. A key example includes the re-engineering of a natural lysine riboswitch from Escherichia coli from an OFF- to an ON-switch to control lysine transport in Corynebacterium glutamicum, resulting in significantly increased lysine yield [7]. This approach demonstrates how riboswitches can be leveraged to dynamically regulate metabolic pathways without requiring external intervention. Similarly, riboswitches have been integrated into central metabolic pathways to balance carbon flux between competing pathways, such as glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and shikimate pathway, preventing the accumulation of toxic intermediates and improving overall pathway efficiency [6].

High-Throughput Screening of Strain Libraries

Aptamer-based RNA sensors coupled with fluorescent outputs enable rapid screening of high-producing microbial strains. By linking metabolite concentrations to fluorescence intensity via riboswitch-controlled expression of reporter genes, researchers can employ fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate top-performing variants from large combinatorial libraries [10] [9]. This approach was successfully implemented using a theophylline-responsive ribozyme modified with an aptamer insertion to screen for enzyme variants with enhanced activity [10]. Specifically, a theophylline-responsive riboswitch was used to screen for caffeine demethylase activity in S. cerevisiae, leading to the identification of mutations that significantly increased both enzyme activity and selectivity [10].

Table 2: Experimental Implementation of Nucleic Acid Biosensors

| Application Area | Biosensor Design | Host Organism | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysine production | Re-engineered lysine riboswitch (OFF to ON) | Corynebacterium glutamicum | Significant increase in lysine yield [7] |

| Enzyme evolution | Theophylline-responsive HHR with aptamer | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Identified mutants with enhanced activity and selectivity [10] |

| Disease modeling | Tetracycline-controlled aptazyme in 3'UTR | Caenorhabditis elegans | Regulated expression of Huntington disease protein [7] |

| Artificial cellular communication | Histamine riboswitch controlling cargo release | Artificial cells | Imitated bacterial quorum sensing [7] |

| Central metabolism regulation | Pyruvate-responsive biosensor with PdhR transcription factor | Escherichia coli | Enhanced production of trehalose and 4-hydroxycoumarin [6] |

Integration with CRISPR-Cas Systems

Recent advances have combined nucleic acid biosensors with CRISPR-Cas technologies to create highly precise genetic regulation systems. In one approach, CRISPR-Cas was used to insert a synthetic exon controlled by a tetracycline-responsive riboswitch into the endogenous CD20 locus in B lymphocytes [7]. This design enabled investigation of B-cell behavior at different CD20 expression levels, revealing new insights into membrane protein organization [7]. The fusion of RNA-based sensing with DNA-targeting capabilities expands the toolbox for metabolic engineers seeking multidimensional control over cellular functions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementation of a Theophylline-Responsive Riboswitch in S. cerevisiae

Purpose: To regulate gene expression in response to theophylline using an aptamer-integrated hammerhead ribozyme (aptazyme) in the 3'UTR of a target gene.

Reagents and Materials:

- Yeast expression vector with target gene

- Theophylline aptamer sequence (e.g., mTCT8-4 [10])

- Hammerhead ribozyme scaffold

- Communication module (transmitter sequence)

- Theophylline (1-10 mM stock solution in DMSO)

- S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., BY4741)

Procedure:

- Aptazyme Construction: Clone the theophylline aptamer into stem II of the hammerhead ribozyme using a communication module [10].

- Vector Assembly: Integrate the constructed aptazyme into the 3'UTR of your gene of interest in a yeast expression vector.

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed vector into S. cerevisiae using standard lithium acetate transformation.

- Induction and Measurement:

- Grow transformed yeast in appropriate selective medium to mid-log phase.

- Add theophylline to final concentrations ranging from 0.1-10 mM.

- Incubate for 4-24 hours and measure output (e.g., fluorescence, enzyme activity).

- Characterization: Determine the dynamic range by comparing output levels in the presence and absence of theophylline.

Technical Notes: The communication module is critical for effective allosteric control. Optimal theophylline concentrations typically range from 1-10 mM in yeast [10]. Expected outcomes include up to 14-fold induction in fluorescence for properly functioning AND-gate ribozymes [10].

Protocol 2: Dynamic Metabolic Control Using a Lysine Riboswitch

Purpose: To dynamically regulate metabolic flux in bacterial systems using a natural lysine riboswitch re-engineered for ON-function.

Reagents and Materials:

- Natural lysine riboswitch from E. coli [7] [11]

- Bacterial expression vector

- Corynebacterium glutamicum strains

- Lysine standard solutions

- Analytical equipment for lysine quantification (HPLC)

Procedure:

- Riboswitch Engineering: Modify the natural lysine riboswitch through mutagenesis to convert from OFF- to ON-function [7].

- Pathway Integration: Place the engineered riboswitch upstream of lysine transport or biosynthetic genes.

- Strain Transformation: Introduce the construct into C. glutamicum.

- Fermentation and Analysis:

- Grow engineered strains in production medium.

- Monitor lysine accumulation over time.

- Compare performance with control strains lacking riboswitch regulation.

- Optimization: Fine-tune riboswitch response by adjusting ribosome binding sites or linker sequences.

Technical Notes: Structural studies reveal the lysine riboswitch features an intricate architecture involving three-helical and two-helical bundles connected by a five-helical junction [11]. Recognition is governed by shape complementarity with multiple direct and K+-mediated hydrogen bonds to lysine's charged ends [11].

Figure 2: Riboswitch Development Workflow. Iterative process for developing functional riboswitches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Biosensor Implementation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aptamer Sequences | Theophylline aptamer (mTCT8-4), Tetracycline aptamer | Sensory domain for ligand recognition | Core conserved residues essential for binding (e.g., C27 in theophylline aptamer) [10] |

| Ribozyme Scaffolds | Hammerhead (HHR), HDV, twister, glmS ribozymes | Catalytic domain for post-transcriptional control | HHR most commonly used; integrate into 3'UTR for mRNA stability control [10] |

| Communication Modules | Transmitter sequences | Link aptamer and ribozyme for allosteric control | Critical for effective coupling; position between aptamer and ribozyme domains [10] |

| Selection Technology | SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential Enrichment) | De novo aptamer generation | Enables development of aptamers against novel targets [7] [8] |

| Computational Tools | Structure prediction algorithms, Molecular modeling | Virtual screening and rational design | Reduces experimental screening burden; enables structure-based optimization [8] |

| Expression Platforms | 5'UTR, 3'UTR, intronic sequences, synthetic exons | Context for biosensor integration | 3'UTR positioning useful for aptazymes; synthetic exons enable splicing control [7] |

| N-(2-Bromoethoxy)phthalimide | N-(2-Bromoethoxy)phthalimide, CAS:5181-35-1, MF:C10H8BrNO3, MW:270.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (2S,3S)-2,3-Diaminobutane-1,4-diol | (2S,3S)-2,3-Diaminobutane-1,4-diol|CAS 151630-98-7 | Bench Chemicals |

Performance Evaluation and Optimization Strategies

Critical Performance Metrics

Evaluating nucleic acid biosensors requires assessment of multiple performance parameters. Dynamic range refers to the ratio between maximal and minimal output signals, with effective riboswitches typically achieving 5- to 20-fold regulation [10] [5]. The operating range defines the ligand concentration window over which the biosensor functions optimally, while response time indicates how quickly the system reacts to metabolite changes [5]. Signal-to-noise ratio must be sufficiently high to enable reliable distinction between states, particularly for screening applications [5]. Additionally, orthogonality—the biosensor's ability to function without cross-talk in complex cellular environments—is essential for implementation in metabolic engineering.

Optimization Methodologies

Biosensor performance can be enhanced through both experimental and computational approaches. Rational tailoring using structure-guided mutagenesis can improve affinity, specificity, and dynamic range [8]. For instance, modifying communication modules between aptamer and expression platforms can significantly alter regulatory behavior [10]. High-throughput screening of mutant libraries using FACS enables directed evolution of improved biosensor variants [10] [8]. Computational approaches including structure prediction and molecular dynamics simulations help identify optimization targets by modeling ligand binding and conformational changes [8]. Context-dependent performance issues can be addressed by engineering insulator sequences or testing multiple genomic integration sites to minimize positional effects.

Nucleic acid-based biosensors represent versatile and powerful tools for dynamic metabolic control, offering unique advantages including compact size, minimal metabolic burden, and modular architecture. As the field advances, integration of computational design with high-throughput experimental validation will enable development of biosensors with enhanced performance characteristics [8]. Emerging opportunities include the construction of multi-input biosensors responding to multiple metabolites, integration with machine learning for predictive metabolic control, and application in therapeutic contexts for smart drug delivery [5] [9]. By providing precise, real-time regulation of metabolic fluxes, these RNA-based devices will play an increasingly important role in next-generation metabolic engineering strategies for sustainable bioproduction.

Transcription factor (TF)-based biosensors are fundamental components in synthetic biology for dynamically regulating metabolic pathways. Extended metabolic biosensors represent an advanced class of genetic circuits that cascade a bio-conversion pathway with a transcription factor responsive to a downstream effector metabolite [13]. This architecture significantly expands the sensing capabilities of natural biosensors, enabling the detection of non-native effector molecules and facilitating context-aware dynamic control in microbial cell factories [13].

These systems are particularly valuable for addressing a central challenge in metabolic engineering: static control strategies that optimize pathway expression under fixed conditions often fail to maintain optimal performance when confronted with industrial bioreactor fluctuations, leading to suboptimal titers, yield, and productivity [13]. Extended biosensors overcome this limitation by providing a dynamic feedback mechanism that allows the production host to self-regulate metabolic fluxes in response to internal metabolite levels.

This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for implementing extended TF-based biosensors, using the flavonoid naringenin biosynthesis pathway in Escherichia coli as a primary case study. The content is framed within a broader research thesis on designing robust biosensor systems for dynamic metabolic pathway regulation.

Application Notes: Naringenin Production Case Study

Pathway and Biosensor Architecture

The naringenin biosynthesis pathway from the precursor L-tyrosine consists of four enzymatic steps [13]. In an extended biosensor configuration, the pathway is coupled with a transcription factor that senses a downstream metabolite, creating a closed-loop regulatory system.

Key Pathway Enzymes and Sensing Components:

| Component | Type | Function in Pathway/Biosensor |

|---|---|---|

| TAL | Enzyme | Converts L-tyrosine to p-coumaric acid |

| 4CL | Enzyme | Activates p-coumaric acid to p-coumaroyl-CoA |

| CHS | Enzyme | Condenses p-coumaroyl-CoA with malonyl-CoA to form naringenin chalcone |

| CHI | Enzyme | Isomerizes naringenin chalcone to naringenin |

| Transcription Factor (TF) | Sensing | Binds to a specific downstream effector metabolite (e.g., naringenin or derivative) |

| Inducible Promoter | Regulation | Controls expression of upstream pathway genes in response to TF-effector binding |

The selection of the TF is critical. The effector molecule for the TF must be a metabolite that is reachable from the target product (naringenin) via enzymatic transformations and must fall within the set of known effector metabolites that can induce a transcriptional response [13]. With approximately 750 known small-molecule chemical effectors for transcription factors, the design space for such circuits is substantial [13].

Quantitative Performance Data

Reported performance metrics for naringenin production and biosensor-controlled pathways provide benchmarks for expected outcomes.

Table 1: Reported Naringenin Production Metrics in E. coli

| Strain/Strategy | Maximum Titer (mg Lâ»Â¹) | Key Features | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized Static Production | ~200 - 474 | Host optimization, precursor feeding | [13] |

| Theoretical Maximum (Simulation) | ~800 (in 48 h) | Projected from L-tyrosine yield optimization (0.44 g/g glucose) | [13] |

Table 2: Biosensor Performance Characteristics for Key Metabolites

| Sensed Parameter | Example Sensor | EC₅₀ | Dynamic Range (ΔF/Fmin) | Positive Control Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADH/NAD+ Ratio | SoNar | 0.025 | 15 | Antimycin A, FCCP [14] |

| ATP/ADP Ratio | PercevalHR | 3.5 | 3 | Oligomycin, Glucose withdrawal [14] |

| ATP | iATPSnFR | 150 µM | 2.4 | Oligomycin, Glucose withdrawal [14] |

Integration with Robust Control Circuits

A key advancement is integrating extended biosensors with feedback controllers like the antithetic integral circuit to enhance robustness against environmental fluctuations [13]. This combination helps maintain pathway stability and consistent product output despite perturbations in industrial-scale bioreactors, such as nutrient gradients or pH shifts. The dynamic response of a regulated flavonoid pathway demonstrates this improved operational stability [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Designing an Extended Biosensor for a Target Product

Objective: To computationally design an extended metabolic biosensor circuit for a desired target product (e.g., naringenin).

Materials:

- Bioinformatics Databases: SensiPath [13] or similar tools for in silico screening of the extended metabolic space.

- Metabolic Network Model: A genome-scale model of the host organism (e.g., E. coli).

- TF Effector Database: A curated list of known transcription factors and their cognate effector molecules [13].

Procedure:

- Define the Target: Identify the chemical structure of the target product (e.g., naringenin).

- Identify Reachable Metabolites: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., SensiPath) to enumerate all metabolites that can be enzymatically produced from the target product. This forms the set of reachable metabolites [13].

- Intersect with TF Effectors: Compare the set of reachable metabolites against the database of known TF effector molecules. The intersection defines potential effector metabolites for the biosensor [13].

- Pathway Selection: For each candidate effector metabolite, identify the minimal enzymatic cascade (one or more enzymatic steps) required to convert the target product into the effector.

- Circuit Assembly: Design the genetic circuit such that:

- The enzymatic cascade for the effector conversion is expressed constitutively or under a separate promoter.

- The TF gene is expressed constitutively.

- The output of the TF (activated by the effector) regulates the promoter controlling key genes in the biosynthesis pathway of the target product.

Protocol: Implementing a Regulated Naringenin Pathway in E. coli

Objective: To clone and test an extended biosensor circuit for dynamic regulation of naringenin production in E. coli.

Materials:

- Strains: E. coli chassis strain with enhanced L-tyrosine production (e.g., engineered for precursor availability) [13].

- Plasmids: Cloning vectors compatible with inducible expression and pathway assembly (e.g., pET, pBAD derivatives).

- Genes: Codon-optimized genes for TAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI, and the selected TF.

- Media: M9 minimal media or LB media supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and carbon sources (e.g., glucose).

- Inducers/Inhibitors: Chemicals for positive controls based on the sensor used (e.g., Antimycin A for NADH/NAD+ sensors, Oligomycin for ATP/ADP sensors) [14].

Procedure:

- Strain Engineering:

- Assemble the naringenin pathway genes (TAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI) into one or more expression vectors. Strong, constitutive promoters can be used initially for proof-of-concept.

- Clone the extended biosensor module. This includes the gene for the conversion enzyme(s) that transform naringenin into the TF effector, and the TF itself under a constitutive promoter.

- Place a key rate-limiting gene of the naringenin pathway (e.g., TAL) under the control of the TF-responsive promoter.

- Co-transform or sequentially transform the pathway and biosensor constructs into the production E. coli host.

Cultivation and Induction:

- Inoculate primary cultures from single colonies and grow overnight.

- Dilute secondary cultures to a standard OD₆₀₀ (e.g., 0.05) in fresh media.

- Incubate cultures at suitable conditions (e.g., 37°C, 250 rpm). Induction might be necessary if inducible promoters are used for the initial pathway expression.

Monitoring and Sampling:

- Monitor cell growth (OD₆₀₀) periodically.

- Sample the culture broth at regular intervals (e.g., every 3-6 hours over 48-72 hours).

- Centrifuge samples to separate cells from supernatant for product analysis.

Analytical Methods:

- Product Quantification: Analyze the supernatant using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or LC-MS to quantify naringenin and key intermediate (e.g., p-coumaric acid) concentrations. Compare titers and yields against control strains lacking the biosensor.

- Sensor Response Validation: If the TF is fused to a reporter (e.g., GFP), measure fluorescence periodically using a plate reader or flow cytometry to correlate effector levels with regulatory output.

Robustness Assessment: Subject the regulated strain and a statically controlled strain to environmental perturbations (e.g., temperature shifts, substrate pulsing) and compare the stability of naringenin production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Extended Metabolic Biosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Domains | ||

| Transcription Factors (TFs) | Core sensing element; binds specific effector metabolite | Libraries available from natural sources; can be engineered via directed evolution [13] [15] |

| RNA Switches (Aptamers) | Nucleic acid-based sensing; regulates translation or transcription | Riboswitches, ribozymes; useful for metabolites without known TFs [15] |

| Genetic Parts | ||

| Inducible Promoters | Provides regulatory control point for pathway genes | TF-responsive promoters (e.g., PLux, PTet); strength tunable via RBS engineering [13] |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Quantitative readout of biosensor activity and dynamic range | GFP, RFP; enables high-throughput screening [14] [15] |

| Host Organisms | ||

| Escherichia coli | Common bacterial chassis for pathway prototyping | Well-characterized genetics; high transformation efficiency [13] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Eukaryotic yeast host; suited for complex plant pathways | Bacillus subtilis used for N-acetylglucosamine production [15] |

| Engineering & Screening Tools | ||

| Directed Evolution Platforms | Optimizes biosensor properties (sensitivity, dynamic range) | Used to develop sensors with novel ligand specificity or improved performance [13] [15] |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Enables rapid sorting of high-producing strains or enzyme variants | FACS-based screening when coupled with fluorescent reporters [15] |

| Analytical Equipment | ||

| HPLC / LC-MS | Quantifies target metabolite titers and pathway intermediates | Essential for validating production metrics and pathway flux [13] |

| Fluorescence Microscope/Plate Reader | Measures biosensor output (e.g., FRET, intensity changes) | Used for real-time, compartment-specific metabolite measurements [14] |

| Di-tert-butyl 3,3'-Iminodipropionate | Di-tert-butyl 3,3'-Iminodipropionate, CAS:128988-04-5, MF:C14H27NO4, MW:273.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (R)-1-(6-Methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)ethanamine | (R)-1-(6-Methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)ethanamine|CAS 132951-65-6 |

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Extended biosensor logical workflow for naringenin production.

Central Carbon Metabolism (CCM) serves as the fundamental conduit for carbon distribution in living cells, generating energy, reducing power, and critical precursor metabolites that fuel biosynthetic pathways. In metabolic engineering, optimizing the flux through CCM is paramount for achieving economically viable production of value-added compounds. The intermediates of CCM—such as acetyl-CoA, erythrose-4-phosphate, and pyruvate—act as key nodes from which flux can be diverted toward the synthesis of a diverse range of products, including pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and biopolymers. The emergence of sophisticated biosensor technology has revolutionized our ability to monitor and dynamically regulate the concentrations of these pivotal metabolites, enabling real-time pathway optimization and high-throughput strain screening. This document details the critical metabolite targets, their derivative pathways, and provides specific application protocols for their analysis and engineering within a research framework focused on biosensor design for dynamic metabolic pathway regulation.

Key Metabolite Targets and Their Value-Added Products

The following tables summarize the primary metabolite targets derived from central carbon metabolism, their roles in biosynthesis, and the value-added products they can generate.

Table 1: Key CCM Intermediates and Their Biosynthetic Roles

| Metabolite Target | Central Metabolic Pathway | Primary Biosynthetic Role | Representative Host Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | Glycolysis, TCA Cycle | Primary building block for lipids, polyketides, terpenoids, and fatty acid-derived compounds | S. cerevisiae, E. coli, Y. lipolytica |

| Erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) | Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | Essential precursor for the shikimate pathway and aromatic amino acids | S. cerevisiae, E. coli |

| Pyruvate | Glycolysis | Precursor for alcohols, organic acids, and branched-chain amino acids | E. coli, C. glutamicum, S. cerevisiae |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | Glycolysis | High-energy metabolite; precursor for the shikimate pathway and aromatic compounds | E. coli, C. glutamicum |

| Glucose-6-Phosphate (G6P) | Glycolysis, PPP | Node metabolite directing flux to glycolysis or PPP; precursor for nucleotides | S. cerevisiae, E. coli |

Table 2: Value-Added Products Derived from Key Metabolites

| Key Metabolite | Value-Added Product | Product Category/Application | Maximum Reported Titer (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | Fatty Acids / Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters (FAEE) | Biofuels | 5100 g/CDW [16] |

| Acetyl-CoA | Farnesene | Biofuel, Chemicals | 25% increase via CCM optimization [16] |

| Acetyl-CoA | Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) | Bioplastics | 56.4 mg/g (from ethanol) [16] |

| Acetyl-CoA | 3-Hydroxypropionic Acid (3-HP) | Platform Chemical | 864.5 mg/L in yeast [16] |

| Erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) | p-Hydroxycinnamic Acid | Aromatic Compound, Nutraceutical | 12.5 g/L in yeast [16] |

| Erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) | Naringenin | Flavonoid, Pharmaceutical | ~200 mg/L - 474 mg/L in E. coli [13] |

| Erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) | Tyrosol / Salidroside | Phenolic Antioxidants | >10 g/L (total) in yeast [16] |

| Pyruvate | L-Lysine | Amino Acid, Feed Additive | Global demand ~1.5 million tons/year [17] |

Workflow for Metabolite Engineering and Biosensor Application

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for engineering microbial cell factories, from identifying a key metabolite to implementing biosensor-driven dynamic regulation.

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Dynamic Regulation of Naringenin Biosynthesis Using an Extended Metabolic Biosensor

Background: Naringenin is a flavonoid with significant pharmacological properties and serves as a central scaffold for diverse flavonoids. Its production in E. coli from the precursor L-tyrosine involves a four-step enzymatic pathway. A major challenge is flux imbalance, leading to suboptimal titers. This protocol describes the implementation of an extended metabolic biosensor coupled with an antithetic integral feedback controller to dynamically regulate the pathway, ensuring robustness against environmental perturbations [13].

Key Metabolites & Pathway: L-tyrosine → p-Coumaric Acid → p-Coumaroyl-CoA → Naringenin

Experimental Objectives:

- To design an extended biosensor that converts naringenin (or a key intermediate) into an effector molecule recognized by a transcription factor (TF).

- To integrate the biosensor with an antithetic controller that adjusts the expression of pathway enzymes in response to metabolite levels.

- To evaluate the dynamic response and production titer of the engineered strain under industrial bioreactor conditions.

Materials:

- Strain: E. coli chassis engineered with the heterologous naringenin pathway.

- Plasmids:

- Sensor Plasmid: Harbors the genes for the extended metabolic pathway (converting target metabolite to TF effector) and the TF-regulated reporter/output gene.

- Controller Plasmid: Contains the antithetic integral circuit components (e.g., two antagonistic proteins that provide integral feedback).

- Actuator Plasmid: Expresses the key naringenin pathway enzymes under the control of the TF-regulated promoter.

- Media: M9 minimal media or similar, supplemented with glucose and appropriate antibiotics.

- Equipment: Bench-top bioreactor, spectrophotometer (for OD600), HPLC system for naringenin quantification.

Procedure:

- Biosensor Circuit Design:

- Select a TF whose natural effector is structurally related to a downstream derivative of naringenin. If no direct match exists, use databases like SensiPath [13] to computationally design a short, heterologous metabolic pathway that converts naringenin into a known TF effector.

- Clone the genes for this "extended" converter pathway and the TF under a constitutive promoter.

- Place a fluorescent reporter gene (e.g., GFP) or an actuator gene under a promoter specifically regulated by the chosen TF.

Integration with Antithetic Controller:

- Co-transform the biosensor plasmid with an antithetic controller plasmid. A common antithetic circuit involves two proteins, 'z1' and 'z2', that neutralize each other. The sensor output (e.g., TF activity) promotes the production of 'z1', while 'z2' is constitutively expressed. The difference in their concentrations provides an integral feedback signal [13].

- This feedback signal is used to drive the expression of a critical enzyme in the naringenin pathway (e.g., tyrosine ammonia-lyase), creating a closed-loop system.

Cultivation and Analysis:

- Inoculate the engineered strain in a bioreactor to allow precise control of environmental parameters like nutrient feed and pH.

- Induce pathway expression during the mid-exponential phase.

- Monitor: Track cell density (OD600), fluorescence from the biosensor (if applicable), and naringenin concentration via HPLC over 48-72 hours.

- Perturbation Test: Introduce a deliberate perturbation (e.g., a pulse of substrate or a temperature shift) to assess the system's robustness. A well-tuned controller will maintain stable production and quickly return to set-point after the perturbation.

Troubleshooting:

- Low Dynamic Range: Optimize the biosensor by engineering regulatory elements (e.g., RBS libraries, promoter strength) or using directed evolution on the TF [13] [17].

- Unstable Control: Re-tune the expression levels of the antithetic controller components (z1 and z2) to achieve a stable steady-state.

- Host Burden: Consider genome integration of the circuit components to reduce plasmid copy number variation and improve genetic stability.

Protocol 2: Rewiring Central Carbon Metabolism using a Heterologous Phosphoketolase (PHK) Pathway

Background: The native glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) in S. cerevisiae can lead to inefficient carbon flux toward certain precursors like acetyl-CoA and erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P). Introducing the heterologous phosphoketolase (PHK) pathway creates a shortcut that directly converts fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) and xylulose-5-phosphate (X5P) into acetyl-CoA, bypassing several steps in central metabolism. This rearrangement increases the supply of acetyl-CoA for lipid-based products and can indirectly boost E4P supply for aromatic compound synthesis [16].

Key Metabolites & Pathway: F6P/X5P → (Phosphoketolase) → Acetyl-P → (Phosphotransacetylase) → Acetyl-CoA

Experimental Objectives:

- To introduce the PHK pathway into a yeast production chassis.

- To measure the resulting rearrangement of carbon flux in CCM.

- To quantify the increase in yield of the target product (e.g., fatty acids, E4P-derived compounds).

Materials:

- Strain: S. cerevisiae production chassis (e.g., for fatty acids or p-hydroxycinnamic acid).

- Genes: Codon-optimized genes for phosphoketolase (PK) and phosphotransacetylase (PTA).

- Media: Synthetic Defined (SD) medium with glucose as carbon source.

- Equipment: Shaking incubator, GC-MS or LC-MS for metabolic flux analysis, HPLC for product quantification.

Procedure:

- Strain Construction:

- Assemble an expression cassette containing the PK and PTA genes under strong, constitutive promoters.

- Integrate this cassette into the genome of the host production strain or express it on a plasmid.

Flux Analysis (¹³C Tracing):

- Grow the engineered strain and a control strain (without PHK pathway) in SD medium with ¹³C-labeled glucose (e.g., [1-¹³C] glucose).

- Harvest cells during mid-exponential phase and quench metabolism rapidly.

- Extract intracellular metabolites and analyze using GC-MS or LC-MS to determine the labeling patterns in intermediates of glycolysis, PPP, and TCA cycle. This data will confirm the redirection of flux through the PHK pathway.

Product Yield Assessment:

- Perform fed-batch fermentations in bioreactors for both the engineered and control strains.

- Monitor glucose consumption and cell growth.

- Quantify the final titer of the target product (e.g., free fatty acids, p-hydroxycinnamic acid) and calculate the yield on glucose. Expect a significant increase in the engineered strain [16].

Troubleshooting:

- No Flux Increase: Verify the enzymatic activity of PK and PTA in vitro. Check for potential metabolic bottlenecks downstream of acetyl-CoA (e.g., acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity for fatty acid synthesis).

- Redox Imbalance: The PHK pathway can alter NADPH/NADP+ ratios. Overexpress NADPH-generating enzymes (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) or use an NADP+-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase to correct any imbalance [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Biosensor-Driven Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function & Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor (TF) Biosensors | Sensing | Converts metabolite concentration into transcriptional output for screening or regulation. | Used for dynamic control of naringenin pathway [13]. Tunable via RBS engineering [17]. |

| FRET-Based Biosensors | Sensing / Imaging | Enables real-time, quantitative monitoring of metabolite levels in living cells via conformational change. | Used for lysine, pyruvate, NADPH [17]. iNap sensors for NADPH quantification [17]. |

| Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) | Sensing / Imaging | Provides superior quantification for FRET biosensors, independent of sensor concentration or excitation power. | Ideal for precise quantification of biosensor response in complex cellular environments [18]. |

| Phosphoketolase (PK) Pathway | Metabolic Engineering | Heterologous pathway to enhance acetyl-CoA and E4P supply from CCM. | From Aspergillus nidulans or other microbes; key for lipid and aromatic compound production [16]. |

| Antithetic Integral Feedback Controller | Control Theory | Synthetic circuit providing robust regulation and perfect adaptation in dynamic pathway control. | Used to maintain pathway balance despite perturbations [13]. |

| Central Carbon Metabolism (CCM) | Chassis | The fundamental metabolic network providing precursors, energy, and reducing power. | Optimization of glycolysis, TCA, and PPP in E. coli or yeast is foundational [16]. |

| Methyl 2-(bromomethyl)-4-chlorobenzoate | Methyl 2-(bromomethyl)-4-chlorobenzoate, CAS:145908-29-8, MF:C9H8BrClO2, MW:263.51 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (E)-oct-5-en-2-ol | (E)-oct-5-en-2-ol|128.21 g/mol|CAS 89122-05-4 | High-purity (E)-oct-5-en-2-ol for research. A versatile unsaturated alcohol building block for synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Biosensor Integration and Signaling Logic

The diagram below illustrates the core logic of how a transcription factor-based biosensor integrates with a synthetic genetic circuit to enable high-throughput screening or dynamic pathway regulation.

The targeted engineering of central metabolic intermediates represents a powerful strategy for amplifying the production of value-added compounds in microbial cell factories. The integration of biosensors—particularly those designed for extended metabolite sensing and dynamic regulation—transforms the engineering cycle from a static, trial-and-error process into a responsive and adaptive system. The protocols outlined here, focusing on dynamic control of flavonoid production and rewiring of carbon core metabolism, provide a tangible roadmap for researchers to implement these advanced concepts. As the libraries of characterized transcription factors and synthetic biology tools continue to expand, the precision and scope of biosensor-mediated metabolic engineering will undoubtedly unlock new frontiers in green biomanufacturing.

Engineering Strategies and Implementation in Pathway Regulation

Computational Protein Design and Directed Evolution for Biosensor Engineering

The engineering of high-performance biosensors is a critical endeavor for advancing dynamic metabolic pathway regulation research. These biosensors allow researchers to monitor and control cellular metabolism in real-time, enabling the construction of sophisticated microbial cell factories. Two primary technological paradigms have emerged for creating and optimizing these molecular tools: computational protein design (CPD) and directed evolution (DE). CPD employs advanced algorithms and physics-based models to rationally design protein sequences with desired functions from first principles [19] [20]. In contrast, DE mimics natural selection in the laboratory through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening to improve protein functions [21] [22]. This Application Notes and Protocols document provides detailed methodologies for implementing both approaches, framed within the context of biosensor engineering for metabolic pathway regulation. The protocols are designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to advance biosensor capabilities for real-time metabolic monitoring and control.

Computational Protein Design of Biosensor Components

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Computational protein design relies on four key components: protein structure backbone, energy functions, sampling algorithms, and sequence optimization techniques [19]. The process involves designing protein sequences that fold into stable structures capable of performing specific functions, such as binding to target molecules. For biosensor engineering, this typically involves designing binding domains that undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding, which can then be linked to reporter domains.

The basic CPD workflow consists of:

- Backbone Selection: Identifying or generating a protein scaffold with the desired structural topology

- Sequence Design: Optimizing amino acid sequences to stabilize the fold and create functional sites

- Structure Prediction: Validating that designed sequences adopt target conformations

- Experimental Verification: Testing designed proteins for expression, stability, and function [19]

Table 1: Key Computational Tools for Protein Design

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Structure prediction & design | Physics-based energy functions, flexible backbone design [19] |

| AlphaFold2 | Deep Learning | Structure prediction | Highly accurate 3D structure predictions from sequence [23] |

| ProteinMPNN | Deep Learning | Sequence design | Neural network for sequence optimization based on backbone structure [23] |

| RFdiffusion | Deep Learning | Structure generation | Generates novel protein structures matching desired specifications [23] |

| RIFdock | Algorithm | Protein-DNA interface design | Samples docks maximizing specific side-chain interactions [23] |

Protocol: Computational Design of DNA-Binding Proteins

This protocol adapts recent advances in computational DBP design for creating biosensor DNA-binding domains that can regulate transcription in response to metabolite binding [23].

Materials:

- High-performance computing cluster with CPU/GPU capabilities

- Rosetta software suite (license required)

- AlphaFold2 installation

- Custom scripts for RIFdock analysis

- E. coli expression strains for experimental validation

Procedure:

Scaffold Library Preparation

- Identify helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domains from metagenome sequence databases

- Generate structure predictions using AlphaFold2 for ~26,000 HTH scaffolds

- Filter scaffolds based on prediction confidence (pLDDT > 80) and structural diversity

- Select scaffolds <65 amino acids for optimal biosensor integration [23]

Target-Specific Docking

- Define target DNA sequence and generate B-DNA structure

- Use RIFdock to sample scaffold docks against DNA target

- Maximize potential for specific side chain-base interactions

- Prioritize docks with main-chain phosphate hydrogen bonds

- Generate 200,000-300,000 designed complexes per target [23]

Sequence Optimization

- Perform initial side-chain repacking to remove clashes

- Conduct full sequence design using either:

- Option A (Rosetta): Iterative design with position-specific scoring matrix

- Option B (LigandMPNN): Deep learning-based sequence design

- Execute multiple design iterations with Rosetta backbone relaxation

- Select designs with favorable binding energy (ΔΔG < -15 REU) and >500 Ų interface surface area [23]

Specificity and Preorganization Assessment

- Analyze interface hydrogen bonds, prioritizing bidentate arrangements

- Calculate side-chain preorganization using Rosetta RotamerBoltzmann

- Select designs with native-like preorganization of key contacts

- Filter designs with specificity matching computational models at ≥6 base-pair positions [23]

Validation and Selection

- Predict monomer structures of selected designs using AlphaFold2

- Discard designs deviating from original models (RMSD > 2.0 Ã…)

- Superimpose predicted structures onto design complexes

- Perform final Rosetta relaxation in DNA context

- Select top 10-20 designs for experimental characterization

Directed Evolution of Biosensors

Advanced Directed Evolution Platforms

Directed evolution remains a powerful complementary approach to computational design, particularly for optimizing complex biosensor properties such as dynamic range, specificity, and sensitivity. Recent advances have automated and accelerated this process through integrated platforms.

Table 2: Directed Evolution Platforms for Biosensor Optimization

| Platform/System | Evolution Mechanism | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| iAutoEvoLab | Automated continuous evolution | ~1 month autonomous operation | Full biosensor development from inactive precursors [24] [25] |

| OrthoRep | In vivo continuous mutagenesis | 10^7-10^8 variant capacity | Growth-coupled evolution of biosensors [24] |

| FACS Screening | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting | 10^8 cells/hour | Biosensor sensitivity and dynamic range optimization [22] |

| Yeast Display | Surface display with sorting | 10^7 variants/round | Transcription factor-based biosensor engineering [23] |

Protocol: Directed Evolution of Transcription Factor-Based Biosensors

This protocol details the directed evolution of transcription factor-based biosensors for metabolite detection, using a lead-sensing PbrR-based biosensor as an exemplar [22].

Materials:

- Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (e.g., BD FACSAria)

- MOPS minimal medium

- Kanamycin antibiotic solution (20 μg/mL)

- pBRR plasmid library with mutant transcription factors

- GFP reporter plasmid

- Lead standard solutions for calibration

Procedure:

Mutant Library Construction

- Design mutagenic primers targeting the transcription factor DNA-binding domain

- Perform error-prone PCR with 0.1-0.5 mM Mn²⺠to achieve 1-3 amino acid substitutions per variant

- Clone mutated sequences into expression vector with inducible promoter

- Transform into E. coli JudeI host strain to create library >10â· CFU capacity

- Verify library diversity by Sanger sequencing of 20-30 random clones [22]

High-Throughput Screening with FACS

- Grow library in MOPS medium to OD₆₀₀ = 0.4-0.6

- Induce expression with 0.1 mM IPTG for 3 hours

- Add target metabolite (e.g., 50 μM Pb²⺠for PbrR evolution) for 2 hours

- Analyze 10⸠cells using FACS with 488 nm excitation/530 nm emission

- Collect top 0.1-1% of cells based on fluorescence intensity

- Plate sorted cells on LB-kanamycin for recovery and expansion [22]

Iterative Evolution and Characterization

- Use sorted population as template for subsequent evolution rounds

- Perform 3-4 rounds of evolution with increasing selection stringency

- After each round, isolate single clones for characterization

- Measure biosensor performance parameters:

- Dose-response curves with varying metabolite concentrations

- Specificity testing against structurally similar compounds

- Response time and dynamic range assessment

- Sequence improved variants to identify beneficial mutations [22]

Biosensor Validation in Metabolic Context

- Clone evolved biosensor into metabolic engineering host

- Test performance in real fermentation conditions

- Assess correlation between biosensor output and actual metabolite concentrations

- Validate using analytical methods (HPLC, GC-MS) as gold standard

Integrated Applications in Metabolic Pathway Regulation

Biosensor-Enabled Dynamic Control Systems

The integration of computationally designed or evolved biosensors into metabolic engineering platforms enables dynamic pathway regulation essential for optimizing production of valuable compounds. This approach is particularly valuable for lignocellulosic biomass conversion, where balancing metabolic fluxes is challenging [9].

Implementation Framework:

Biosensor Selection and Integration

- Identify target metabolites for monitoring (e.g., aromatic amino acids, lignin derivatives)

- Integrate biosensor circuits with pathway control elements

- Implement feedback activation and cascading dynamic control strategies [26]

System Optimization and Validation

- Fine-tune expression using promoter and RBS engineering

- Balance metabolic fluxes to prevent intermediate accumulation

- Validate using real-time metabolite monitoring and omics analysis

Table 3: Biosensor Applications in Metabolic Pathway Regulation

| Biosensor Type | Target Metabolite | Application | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription factor-based | L-Tryptophan | Dynamic regulation of shikimate pathway | 50% increase in lycopene yield [26] |

| HucR-V7/PhucR-based | Vanillin | Feedback control of aromatic aldehyde production | Increased titer and reduced toxicity [26] |

| PadR/PpadC-based | p-Coumaric acid | High-throughput screening of production strains | Increased dynamic range and superior sensitivity [26] |

| TtgR-based | (2S)-Naringenin | Flavonoid pathway optimization | Widest detection range for (2S)-naringenin [26] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biosensor Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host Strains | E. coli JudeI, S. cerevisiae | Biosensor expression & screening | JudeI optimal for transcription factor biosensors [22] |

| Selection Antibiotics | Kanamycin (20 μg/mL) | Maintain plasmid selection | Concentration optimized for biosensor circuits [22] |

| Reporter Proteins | GFP, RFP, mCherry, yeGFP | Biosensor output signal | GFP most common; RFP enables multiplexing [26] |

| Induction Systems | IPTG-inducible promoters | Controlled biosensor expression | 0.1 mM IPTG standard for induction [22] |

| Culture Media | MOPS minimal medium | Defined growth conditions | Essential for metal biosensor evolution [22] |

The synergistic application of computational protein design and directed evolution provides a powerful framework for advancing biosensor engineering for dynamic metabolic pathway regulation. Computational approaches enable precise design of biosensor components with atomic-level accuracy, while directed evolution optimizes complex biosensor properties that are difficult to model in silico. The integration of these engineered biosensors into metabolic engineering pipelines enables real-time monitoring and control of metabolic fluxes, significantly enhancing bioproduction efficiency. As both computational and experimental methodologies continue to advance, particularly with the integration of machine learning and laboratory automation, the development of increasingly sophisticated biosensors will accelerate, enabling more precise dynamic regulation of metabolic pathways for sustainable bioproduction.

Dynamic regulation circuits represent a paradigm shift in metabolic engineering, moving beyond static control to systems that autonomously sense and respond to cellular states. These circuits are primarily engineered to decouple cell growth from product synthesis, thereby maximizing the bioproduction titers, rates, and yields (TRY) that are often limited by metabolic burden and product toxicity [13] [27]. At the core of these systems are biosensors—biological devices that detect specific intracellular metabolites and translate this information into pre-programmed genetic outputs. By implementing feedback control, these circuits enable microbial cell factories to maintain metabolic homeostasis, avoid the accumulation of toxic intermediates, and re-direct flux toward desired products under industrial biomanufacturing conditions [13] [5]. This application note provides a detailed overview of the operating principles, quantitative performance, and experimental protocols for implementing dynamic regulation circuits, with a specific focus on balancing growth and production phases.

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Data

The performance of dynamic regulation circuits is quantified by several key parameters that characterize the biosensor and the overall system's efficacy. Critical biosensor metrics include dynamic range (the ratio between output signal in the induced vs. uninduced state), operating range (the concentration window of the analyte over which the biosensor responds), sensitivity (the minimal analyte concentration that elicits a response), and response time [5]. For the overall circuit, key performance indicators (KPIs) include final product titer (g/L), productivity (g/L/h), and yield (g product/g substrate). Furthermore, the success of growth-production balancing is often evident in the cell density (OD600) achieved and the timing of the metabolic switch.

The table below summarizes representative performance data from recent studies implementing dynamic regulation for bioproduction.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Dynamic Regulation Circuits in Bioproduction

| Target Product | Host Organism | Regulation Strategy | Key Metabolite / Signal | Max Titer (g/L) | Cell Density (OD600) | Productivity/Yield | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-Pantothenic Acid (DPA) | Bacillus subtilis | QS-controlled Type I CRISPRi (QICi) | Cell Density (Quorum Sensing) | 14.97 | N/R | Significant improvement in fed-batch | [28] |

| Cadaverine | Escherichia coli | LysP/CadC Lysine Biosensor | L-Lysine | 33.19 | Improved by 21.2% | 48.1% increase vs. constitutive | [27] |

| Riboflavin (RF) | Bacillus subtilis | QS-controlled Type I CRISPRi (QICi) | Cell Density (Quorum Sensing) | N/R | N/R | 2.49-fold increase | [28] |

| Naringenin | Escherichia coli | Extended Biosensor + Antithetic Integral Circuit | Flavonoid Pathway Intermediates | ~0.8 (theoretical) | N/R | Improved robustness | [13] |

| 4-Hydroxycoumarin | Escherichia coli | Engineered PdhR Biosensor | Pyruvate | N/R | N/R | Showcased broad applicability | [6] |

| Trehalose | Escherichia coli | Engineered PdhR Biosensor | Pyruvate | N/R | N/R | Showcased broad applicability | [6] |

N/R: Not explicitly reported in the provided search results.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a generalized workflow and two detailed protocols for implementing and validating dynamic regulation circuits.

Generalized Workflow for Circuit Implementation

The development and application of a dynamic regulation circuit typically follow a multi-stage process, as visualized below.

Protocol 1: Implementing a Lysine Biosensor for Dynamic Cadaverine Production

This protocol is adapted from a study that achieved 33.19 g/L of cadaverine in a fed-batch fermentation [27].

1. Biosensor Construction and Validation

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the lysine biosensor system into a suitable expression vector. The core components include the transcription factor cadC, the lysine transporter lysP, and a reporter gene (e.g., gfpuv) under the control of the Pcad promoter.

- Sensor Characterization: Transform the biosensor plasmid into a suitable E. coli host (e.g., MG1655). Grow cultures in shake flasks with MOPS medium at varying pH (7.6, 7.0, 5.8) and supplement with different concentrations of L-lysine hydrochloride (e.g., 0-10 g/L) during the mid-exponential phase.

- Measurement: After a defined induction period (e.g., 12 hours), measure fluorescence (excitation ~395 nm, emission ~509 nm) and optical density (OD600). Plot fluorescence/OD600 against lysine concentration to determine the dynamic range and sensitivity of the biosensor.

2. Producer Strain Engineering

- Precursor Enhancement: Genetically modify a production host (e.g., E. coli MG1655) to overproduce the precursor L-lysine. This involves chromosomal modifications to upregulate the lysine biosynthesis pathway (e.g., dapA, lysC).

- Pathway Expression: Integrate and express the cadA gene (encoding lysine decarboxylase) under the control of the biosensor-responsive Pcad promoter. This creates the feedback loop where lysine accumulation triggers its own conversion to cadaverine.

- Metabolic Clean-up: Knock out genes involved in competing pathways or cadaverine degradation (e.g., speE, puuA) to maximize carbon flux toward the desired product.

3. Fed-Batch Fermentation

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow seed cultures in LB medium for 12 hours. Use this to inoculate a seed medium, which is then transferred to a 5 L bioreactor containing a defined production medium [27].

- Fermentation Conditions: Maintain temperature at 37°C, pH at 6.8-7.0 using ammonia water, and dissolved oxygen (DO) at ~30% by adjusting the agitation speed (350-800 rpm).

- Feeding Strategy: Monitor glucose concentration. When it falls below 5 g/L, initiate feeding with a concentrated glucose solution (625 g/L) supplemented with MgSO₄·7H₂O (5 g/L) and (NH₄)₂SO₄ (100 g/L) to maintain a residual sugar concentration of ~10 g/L.

- Analytical Sampling: Periodically sample the broth to measure OD600, glucose, L-lysine, and cadaverine concentrations (e.g., via HPLC).

Protocol 2: Quorum Sensing-Controlled CRISPRi for Metabolic Rewiring

This protocol outlines the use of a Quorum Sensing-controlled Type I CRISPR interference (QICi) system for dynamic gene repression, as applied to D-pantothenic acid and riboflavin production in Bacillus subtilis [28].

1. QICi Toolkit Assembly and Optimization

- Circuit Construction: Assemble the genetic circuit where the quorum sensing (QS) system (e.g., involving phrQ and rapQ) controls the expression of a CRISPR-Cas system. The QS system should be designed to activate Cas protein expression at high cell density.

- crRNA Library Construction: Streamline the cloning of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) expression cassettes targeting key metabolic genes (e.g., citZ for citrate synthase in DPA production).

- System Optimization: Fine-tune the system by engineering key QS components (PhrQ, RapQ) to enhance the QICi efficacy, which has been shown to yield a two-fold improvement in performance [28].

2. Strain Reprogramming and Fed-Batch Fermentation

- Dynamic Regulation: Implement the optimized QICi system to repress target genes (citZ) in a growth-coupled manner. As the culture reaches high density, QS triggers CRISPRi, downregulating central metabolism nodes to redirect flux toward the product.

- Additional Engineering: Couple the dynamic regulation with other strategies such as pantoate pathway engineering, cofactor supply enhancement, and suppression of sporulation for synergistic effects.

- Scale-up Evaluation: Perform fed-batch fermentations in 5 L bioreactors without precursor supplementation. Monitor product titer, cell density, and substrate consumption over time to validate the performance of the dynamic control system.

Pathway Diagrams and Logical Workflows

The logical operation of dynamic regulation circuits for growth and production can be understood through the following control diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of dynamic regulation circuits relies on a suite of key reagents and genetic tools. The following table details essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Dynamic Regulation Circuits

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors (TFs) | Protein-based biosensors that bind a ligand (effector) and regulate transcription of a target gene. | LysP/CadC system for lysine [27]; PdhR for pyruvate [29]. Can be engineered for new effectors. |

| Two-Component Systems (TCSs) | Signal transduction systems involving a sensor kinase and a response regulator for detecting environmental signals. | Useful for sensing extracellular signals like ions, pH, or small molecules [5]. |

| Riboswitches & Toehold Switches | RNA-based biosensors that undergo conformational change upon ligand binding, affecting translation. | Offer compact, tunable, and reversible control of gene expression without protein components [5]. |

| CRISPRi/a Systems | Enables targeted repression (interference) or activation of gene expression via a programmable crRNA. | QICi system for dynamic repression of citZ in B. subtilis [28]. Highly modular and programmable. |

| Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems | Cell-density-dependent signaling systems that activate genetic programs at high biomass. | Used in the QICi toolkit to delay metabolic rewiring until a sufficient cell density is achieved [28]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins | Generate a measurable output (fluorescence) for biosensor characterization and high-throughput screening. | GFPuv used for characterizing the lysine biosensor's dose-response [27]. |

| Directed Evolution Tools | Methods for improving biosensor properties (sensitivity, dynamic range) through iterative mutagenesis and screening. | FACS sorting combined with mutagenesis libraries to enhance biosensor performance [5]. |

| (S)-1-Butylpyrrolidine-2-carboxamide | (S)-1-Butylpyrrolidine-2-carboxamide|High Purity | Research-grade (S)-1-Butylpyrrolidine-2-carboxamide for antimicrobial and cardiovascular studies. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 3-(Aminomethyl)-5-methyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole | 3-(Aminomethyl)-5-methyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole, CAS:131052-49-8, MF:C4H8N4, MW:112.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Bifunctional dynamic control represents an advanced paradigm in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, enabling simultaneous upregulation and downregulation of target cellular processes. Such systems are crucial for overcoming a fundamental challenge in metabolic engineering: balancing cell growth with the production of target compounds, which are often at odds [30]. By integrating metabolite-sensing capabilities with programmable regulation tools like CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and antisense RNA (asRNA), these systems autonomously redistribute metabolic flux, diverting resources from native pathways to engineered biosynthesis without compromising cellular viability [31] [32]. This application note details the underlying principles, provides validated protocols, and summarizes key performance data for implementing these sophisticated genetic circuits, framed within the broader context of biosensor design for dynamic metabolic pathway regulation.

System Components and Principles of Operation

The core architecture of a bifunctional control system merges a sensor module with an effector module to create a coherent regulatory response.

Metabolite Sensor Modules

The system is initiated by sensor proteins that detect specific intracellular metabolites. For instance, the transcription factor CatR from Pseudomonas putida senses muconic acid (MA), binding to the PMA promoter and activating transcription in the presence of MA [32]. Alternatively, quorum-sensing (QS) systems can be employed for pathway-independent sensing, using components like LuxR and EsaR to activate or derepress promoters in a cell-density-dependent manner [30].

Effector Modules: CRISPRi and Antisense RNA

The sensory signal is transduced to effector modules for precise genetic control:

- CRISPRi: A nuclease-deficient Cas protein (e.g., dCas9, dCas12a) is guided by a gRNA to bind DNA and block transcription. The system's programmability allows for simultaneous regulation of multiple genomic targets [31] [33].

- Antisense RNA (asRNA): Short, engineered RNA strands complementary to target mRNA sequences are expressed. Upon binding, they prevent translation or trigger mRNA degradation. When designed with Hfq-binding tags, asRNA efficiency is enhanced by facilitating RNA-RNA interactions [31].

In a bifunctional setup, a metabolite sensor can be engineered to simultaneously activate a biosynthetic gene and repress a competing native gene. For example, a CatR-activated promoter can drive the expression of both a heterologous enzyme and a gRNA targeting a host gene, thereby implementing simultaneous up- and down-regulation [32] [33].

Enhanced Regulation through Feedback and Sequestration

Basic CRISPRi circuits can suffer from leaky repression and retroactivity. Advanced circuits incorporate:

- gRNA Sequestration: constitutively expressed "sinker" asRNAs sequester leaked gRNAs, preventing unwanted repression by dCas proteins. This strategy has been shown to significantly improve the dynamic range of CRISPRi inverters, particularly during stationary phase [31].

- Feedback Control: Regulating the production of asRNAs or dCas proteins using CRISPRi itself creates a feedback loop that further stabilizes circuit performance and output [31] [34].

Table 1: Key Genetic Components for Bifunctional Control Systems

| Component Type | Example | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Protein | CatR | Binds muconic acid, activates PMA promoter | From P. putida; LysR family [32] |

| Sensor Protein | LuxR | Binds AHL, activates Plux promoter | Part of quorum-sensing system [30] |