E. coli vs. S. cerevisiae: A Strategic Comparison for Metabolic Engineering Hosts

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae as chassis organisms for metabolic engineering, tailored for researchers and scientists in pharmaceutical and industrial biotechnology.

E. coli vs. S. cerevisiae: A Strategic Comparison for Metabolic Engineering Hosts

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae as chassis organisms for metabolic engineering, tailored for researchers and scientists in pharmaceutical and industrial biotechnology. It explores the foundational biology and inherent advantages of each host, delves into advanced engineering methodologies and successful applications in producing high-value compounds like terpenoids and biofuels, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a direct, evidence-based comparison of their performance. The synthesis aims to equip professionals with the insights needed to select and engineer the most suitable microbial factory for their specific metabolic engineering goals.

Inherent Strengths and Metabolic Foundations of E. coli and S. cerevisiae

The selection of a microbial host is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering and industrial biotechnology. Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae stand as the two most predominant and well-characterized platforms for recombinant protein and chemical production [1]. While both are pillars of industrial bioprocesses, their core physiological and metabolic characteristics differ profoundly, making each uniquely suited to specific applications. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two microbial workhorses, focusing on their intrinsic metabolic networks, physiological constraints, and performance outcomes to inform strategic host selection for research and drug development.

The table below summarizes the fundamental physiological and metabolic differences between E. coli and S. cerevisiae that dictate their performance as engineering hosts.

Table 1: Core Physiological and Metabolic Characteristics at a Glance

| Characteristic | Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type | Prokaryote (Gram-negative bacterium) | Eukaryote (Unicellular fungus) |

| Central Metabolism | Primarily cytosolic; non-compartmentalized | Compartmentalized between cytosol and mitochondria |

| Crabtree Effect | Not applicable | Positive; ferments glucose to ethanol even under aerobic conditions [1] [2] |

| Preferred Metabolism on Glucose | Respiratory (Crabtree-negative) [1] | Fermentative (Crabtree-positive) [1] [2] |

| Native Terpenoid Pathway | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) pathway [3] | Mevalonate (MVA) pathway [3] |

| Cytosolic Acetyl-CoA Synthesis | Direct from pyruvate via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) [4] | Requires multi-step "pyruvate dehydrogenase bypass" [4] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Limited; lacks eukaryotic glycosylation machinery | Capable of complex modifications, including glycosylation [1] |

| Typical Cultivation Time | Hours (fast growth) [3] | Days (slower growth) [3] |

| Robustness in Bioreactors | High, but susceptible to phage contamination [3] | High, with tolerance to low pH and osmotic stress; resistant to phage [3] [5] |

Decoding the Metabolic Networks: A Quantitative Comparison

The structural differences in the central metabolism of these hosts directly impact their theoretical yield and metabolic flexibility for bio-production. In silico metabolic simulations provide a powerful tool for quantifying this potential.

Theoretical Yields and Metabolic Flexibility

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) simulations using backbone metabolic models have been employed to compare the potential of E. coli and S. cerevisiae for producing higher alcohols (e.g., butanols, propanols). These models reveal that the distinct structure of S. cerevisiae's central metabolism limits its flexibility and potential yield for these compounds compared to E. coli [4]. Gene deletion strategies, effective in E. coli to force flux towards products, often severely hamper growth in yeast due to its more rigid network structure [4].

Table 2: In Silico Comparison of Higher Alcohol Production Potential from Glucose [4]

| Product | Pathway | Maximum Theoretical Yield (C-mol/C-mol Glucose) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | ||

| 1-Butanol | Acetyl-CoA | 0.14 | Limited |

| Isobutanol | Pyruvate | 0.19 | Limited |

| Cell Growth | - | Maintained after engineering | Severely reduced by gene deletions |

Terpenoid Pathway Stoichiometry and Energetics

Terpenoids are a prime example where host metabolism dictates precursor supply. The native pathways in each host have distinct stoichiometries, leading to different carbon and energy efficiencies.

Table 3: Stoichiometry of Native Terpenoid Precursor Pathways [3]

| Parameter | E. coli DXP Pathway | S. cerevisiae MVA Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Precursors | Pyruvate + Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate | 3 Acetyl-CoA |

| Overall Stoichiometry (per IPP) | GAP + PYR + 3 NADPH + 2 ATP → IPP + CO₂ + 3 NADP⁺ + 2 ADP | 3 AcCoA + 2 NADPH + 3 ATP → IPP + CO₂ + 2 NADP⁺ + 3 ADP |

| Carbon Efficiency (Pathway Only) | 5/6 (83.3%) | 5/6 (83.3%) |

| Carbon Efficiency (from Glucose) | Higher | Lower (due to carbon loss in acetyl-CoA formation) |

| ATP Cost per IPP | 2 | 3 |

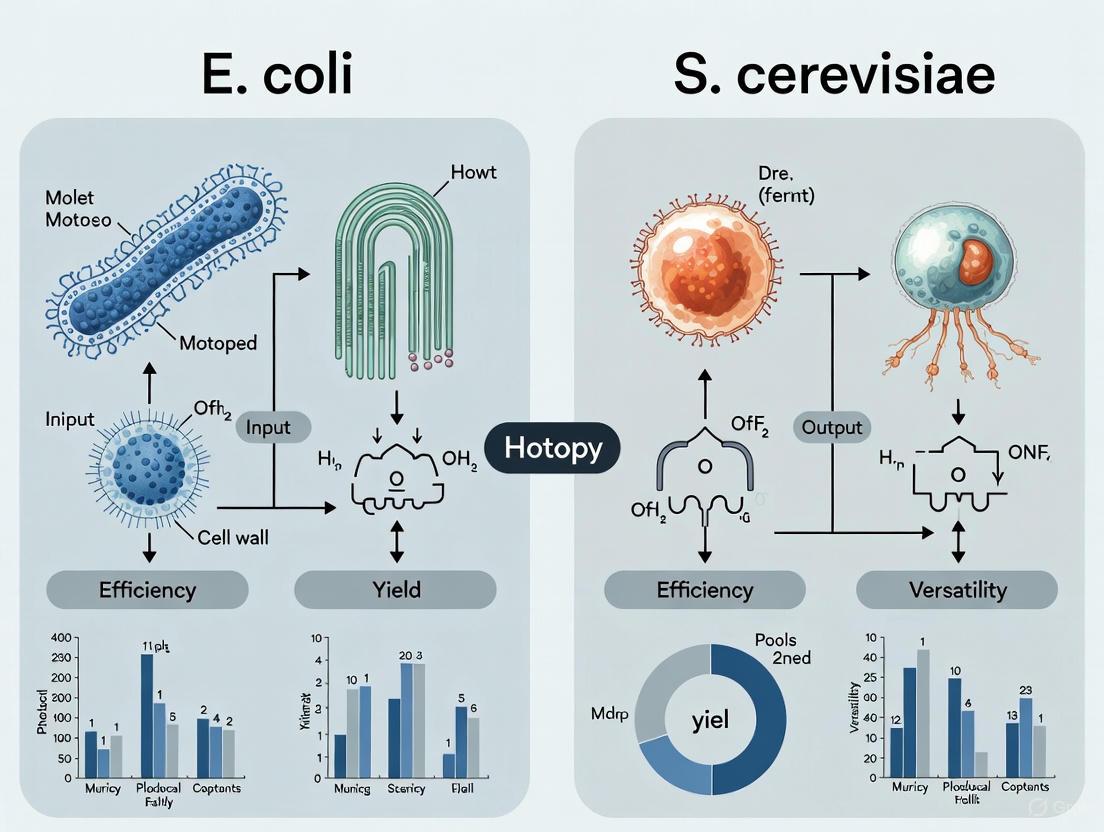

The relationship between the central carbon metabolism and the terpenoid pathways in the two hosts can be visualized as follows:

Experimental Protocols for Host Evaluation

To empirically determine the performance of an engineered pathway in both hosts, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodology outlines a comparative approach.

Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Terpenoid Production

This protocol is adapted from in silico and experimental studies comparing terpenoid production [3].

1. Strain Construction

- E. coli Engineering: Clone the heterologous terpenoid synthase gene(s) (e.g., for amorphadiene or lycopene) into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pET or pBAD). Co-express the entire heterologous MVA pathway (often from S. cerevisiae or Streptomyces sp.) to augment or bypass the native DXP pathway [3].

- S. cerevisiae Engineering: Integrate the terpenoid synthase gene(s) into the yeast genome using methods like CRISPR-Cas9 or classical homologous recombination. Overexpress a truncated, feedback-insensitive version of HMG1 (HMG-CoA reductase) and downregulate ERG9 (squalene synthase) to enhance flux toward the target terpenoid [3].

2. Cultivation and Induction

- Cultivation Conditions: Grow triplicate cultures of each engineered strain in defined minimal medium with glucose as the sole carbon source.

- Fermentation: Use controlled bioreactors to maintain aerobic conditions. For E. coli, typical temperature is 37°C; for S. cerevisiae, 30°C.

- Induction: Induce gene expression at mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8) using an appropriate inducer (e.g., IPTG for E. coli, galactose for S. cerevisiae).

3. Analytical Sampling

- Biomass: Monitor growth by measuring OD600.

- Substrate and Products: Quantify glucose concentration using HPLC-RI. Extract terpenoids from culture broth (e.g., using ethyl acetate) and quantify via GC-MS or HPLC.

- Precursors (Optional): Quantify intracellular acetyl-CoA and NADPH/NADP+ ratios using enzymatic assays or LC-MS.

4. Data Analysis

- Calculate key performance indicators: maximum titer (g/L), yield (Yp/s, g product/g glucose), and productivity (g/L/h).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful metabolic engineering in these hosts relies on a suite of standard and specialized reagents.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Host Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Precision genome editing. | Widely used in S. cerevisiae for gene knock-ins/knock-outs; tools for E. coli are also advanced [6]. |

| Golden Gate Assembly | Modular, hierarchical DNA assembly. | Implemented in K. phaffii and Y. lipolytica; increasingly used for complex pathway construction in yeasts [1]. |

| AOX1 Promoter System | Strong, inducible promoter. | Found in Komagataella phaffii; induced by methanol for high-level recombinant protein production [1]. |

| Enzyme-Constrained Models (ecModels) | GEMs enhanced with kcat and enzyme mass constraints. | Improve prediction accuracy of metabolic fluxes; ecYeast8 demonstrated a 41.9% reduction in growth prediction error [7]. |

| Wallerstein Laboratory (WL) Nutrient Medium | Differential medium for yeast. | Used to distinguish S. cerevisiae from other yeasts based on colony morphology during strain screening [5]. |

| Tetrazolium Chloride (TTC) Assay | Colorimetric assessment of metabolic activity. | Used in yeast screening; darker red coloration indicates higher mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity [5]. |

Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae represent two divergent evolutionary solutions to microbial life, resulting in complementary strengths for metabolic engineering. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with project goals.

- Choose Escherichia coli when your priority is maximum growth rate, high metabolic flexibility for native pathway engineering, and cost-effective production of proteins or chemicals that do not require eukaryotic post-translational modifications.

- Choose Saccharomyces cerevisiae when the product requires complex eukaryotic glycosylation, the pathway benefits from compartmentalization, or the industrial process demands high tolerance to organic acids, low pH, or phage contamination.

Future advancements will continue to blur the lines between these hosts through extensive engineering, such as the introduction of complete heterologous pathways to overcome native metabolic limitations. The ongoing development of sophisticated computational models and genomic tools will further empower researchers to tailor these industrial workhorses for increasingly complex biomanufacturing tasks.

Terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, represent one of the largest and most structurally diverse classes of natural products, with over 75,000 identified members possessing wide applications in pharmaceuticals, flavors, fragrances, and biofuels [8] [9]. All terpenoids are biosynthetically derived from two universal C5 building blocks: isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [10] [11]. In nature, these fundamental precursors are synthesized via two distinct metabolic routes: the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway (also known as the DXP pathway) and the mevalonate (MVA) pathway [10] [12].

The choice between these pathways represents a critical strategic decision in metabolic engineering for terpenoid production. Escherichia coli natively employs the MEP pathway, while Saccharomyces cerevisiae utilizes the MVA pathway [10] [11]. This fundamental difference significantly influences host selection, engineering strategies, and ultimate production yields for target terpenoids. Understanding the distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each pathway is essential for constructing efficient microbial cell factories [8]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these native biosynthetic pathways within the context of host selection for metabolic engineering, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols.

Pathway Architecture and Metabolic Logistics

The MEP and MVA pathways represent evolutionarily distinct routes to the same terpenoid precursors, with profound implications for host engineering [12].

The MEP Pathway (Native to E. coli)

The MEP pathway initiates from two glycolytic intermediates: pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate [10] [11]. This pathway proceeds through seven enzymatic steps to produce IPP and DMAPP, with 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) as a key intermediate [12].

Figure 1: The MEP Pathway in E. coli. Key intermediates include DXP (1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate), MEP (2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate), and HMBPP ((E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate).

The MVA Pathway (Native to S. cerevisiae)

The MVA pathway begins with the condensation of two molecules of acetyl-CoA [10] [13]. This pathway involves six enzymatic steps, with mevalonate as a namesake intermediate, culminating in the production of IPP [13]. DMAPP is subsequently formed via isomerization of IPP [10].

Figure 2: The MVA Pathway in S. cerevisiae. Key intermediates include HMG-CoA (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA) and mevalonate.

Theoretical and Practical Pathway Comparison

Stoichiometric and Energetic Efficiency

From a theoretical perspective, the MEP pathway demonstrates superior carbon efficiency compared to the MVA pathway [10] [9]. Stoichiometric analysis reveals:

- MEP Pathway: Consumes 1 molecule of glucose per IPP produced, with a carbon molar yield of 0.83 C-mol/C-mol [10]. This pathway requires 2 ATP and 2 NAD(P)H per IPP molecule synthesized [10].

- MVA Pathway: Requires 1.5 molecules of glucose per IPP produced, resulting in a lower carbon yield of 0.56 C-mol/C-mol [10]. Notably, this pathway generates 3 NAD(P)H molecules per IPP [10].

Experimental Performance Data

Engineering both native and heterologous pathways in microbial hosts has yielded significant production improvements for various terpenoids. The table below summarizes representative high-titer terpenoid production achieved in E. coli through engineering of both pathways [8].

Table 1: Selected High-Titer Terpenoid Production in Engineered E. coli [8]

| Terpenoid Class | Example Compound | Highest Reported Titer (g/L) | Engineered Precursor Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiterpenoids (C5) | Isoprene | 60.0 | MVA |

| Monoterpenoids (C10) | Geraniol | 2.124 | MVA |

| Limonene | 3.65 | MVA | |

| 1,8-Cineole | 0.653 | MVA | |

| Sesquiterpenoids (C15) | Amorphadiene | 30.0 | MVA |

| β-Farnesene | 10.0 | MVA | |

| Farnesol | 1.419 | MVA | |

| Diterpenoids (C20) | Sclareol | 1.46 | MVA |

Host-Specific Advantages and Limitations

E. coli with the MEP Pathway

- Carbon Efficiency: The native MEP pathway offers higher theoretical carbon yield from glucose [10] [9].

- Precursor Supply: Native MEP pathway typically provides limited IPP/DMAPP flux sufficient only for native quinone synthesis, requiring augmentation for high-level terpenoid production [10] [11].

- Engineering Challenges: The MEP pathway is regulated by complex feedback mechanisms and possesses potential bottleneck enzymes [8].

- P450 Compatibility: Lacks native cytochrome P450 systems for terpenoid functionalization [10] [11].

S. cerevisiae with the MVA Pathway

- Native Flux: Naturally supports high flux toward sterols (e.g., ergosterol), demonstrating substantial precursor supply capacity [10].

- Compartmentalization: Metabolic engineering must navigate competition with essential sterol biosynthesis [13].

- P450 Compatibility: Possesses robust endogenous cytochrome P450 and redox systems for complex terpenoid modification [10] [11].

- Industrial Robustness: Recognized as a GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) organism with established industrial fermentation processes [9].

Experimental Approaches and Engineering Strategies

Representative Engineering Workflow

The generalized workflow for engineering terpenoid production in microbial hosts involves multiple stages of design, construction, and optimization [8].

Figure 3: Generalized Workflow for Engineering Terpenoid Production in Microbial Hosts.

Detailed Protocol: Chromosomal Integration of the MVA Pathway in E. coli

The following protocol summarizes the rational optimization and chromosomal integration strategy for high-level lycopene production in E. coli, as detailed by [14].

- Objective: To achieve stable, high-level terpenoid production through chromosomal integration of heterologous pathways, avoiding plasmid instability.

- Host Strain: E. coli DH411 (or similar K-12 derived strain) [14].

- Key Steps:

- Module Optimization: Divide the complete MVA pathway and lycopene biosynthesis pathway into three modular units. Rationally optimize the copy number and genomic integration site for each module [14].

- Strain Construction: Use λ-Red recombinering or similar method to sequentially integrate optimized modules into the chromosome, resulting in the final production strain (e.g., DH416) [14].

- Fermentation: Cultivate the integrated strain in a controlled bioreactor (e.g., 5 L fermenter) with defined medium. The exemplified process achieved a mean productivity of 61.0 mg/L/h [14].

- Stability Testing: Perform serial passage experiments (e.g., 21 passages) to confirm genetic stability compared to plasmid-based systems [14].

- Outcome: The integrated E. coli system produced lycopene at 1.22 g/L (49.9 mg/g DCW) with significantly improved genetic stability [14].

Detailed Protocol: Establishing the Isopentenol Utilization (IU) Pathway in S. cerevisiae

This protocol outlines the incorporation of a non-native, orthogonal pathway in yeast to augment precursor supply, based on the work of [13] and [15].

- Objective: To bypass native regulatory mechanisms and enhance IPP/DMAPP pool by introducing a synthetic isopentenol utilization (IU) pathway in S. cerevisiae.

- Host Strain: S. cerevisiae with Gal80p disruption (e.g., SCMA00) for inducible expression [13].

- Key Steps:

- Genetic Construction: Introduce genes encoding choline kinase (ScCK) from S. cerevisiae and isopentenyl phosphate kinase (AtIPK) from Arabidopsis thaliana under the control of diauxie-inducible Gal promoters [13].

- Substrate Feeding: After glucose depletion at the diauxic phase, supplement the culture with isoprenol or prenol (optimal concentration ~30 mM) to activate the IU pathway while avoiding substrate toxicity during growth phase [13].

- Metabolite Analysis: Quantify intracellular IP/DMAP and IPP/DMAPP levels using LC-MS/MS to validate pathway functionality [13].

- Advanced Engineering: For further enhancement, create an IU pathway-dependent (IUPD) strain by knocking out the native MVA pathway gene ERG13 and introducing evolved kinase variants to increase flux [15].

- Outcome: Activation of the IU pathway elevated the IPP/DMAPP pool by 147-fold relative to the native MVA pathway, providing ample precursors for downstream terpenoid synthesis [13].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogizes key reagents and genetic elements frequently employed in the construction and optimization of terpenoid production pathways.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Terpenoid Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Genetic Element | Category | Function and Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| pET Expression Vectors | Plasmid System | High-copy number plasmids for strong, inducible expression of pathway genes in E. coli. | pET-28a, pET-21a [16] |

| Gal1/Gal10 Promoters | Regulatory Element | Diauxie-inducible promoters for decoupling growth and production phases in S. cerevisiae. | Used in Gal80p disruption strains [13] |

| CodH/Erg12/Erg8 | MVA Pathway Enzymes | Heterologous enzymes for constructing the mevalonate pathway in non-native hosts like E. coli. | From S. cerevisiae or Enterococcus faecalis [8] [13] |

| ScCK/AtIPK | IU Pathway Enzymes | Kinases for the two-step phosphorylation of isopentenol to IPP/DMAPP in the synthetic IU pathway. | Choline kinase (ScCK), Isopentenyl phosphate kinase (AtIPK) [13] [15] |

| GPPS/LS/FS | Terpene Synthases | Enzymes that convert prenyl diphosphates (GPP, FPP) to specific terpene skeletons. | Geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), Limonene synthase (LS) [16] |

The comparative analysis of native DXP (MEP) and MVA pathways reveals a complex trade-off between theoretical carbon efficiency and practical engineering success. While the MEP pathway native to E. coli offers superior stoichiometry, the MVA pathway—whether native in yeast or heterologously implemented in bacteria—has consistently delivered higher production titers for a wide range of terpenoids [10] [8]. This apparent paradox underscores the critical influence of host physiology, regulatory constraints, and the availability of compatible engineering tools.

Future directions in the field are moving beyond the simple augmentation of native pathways toward more sophisticated strategies. These include the implementation of orthogonal systems like the Isopentenol Utilization Pathway to bypass native regulation [13] [15], the use of genome-scale models to predict and resolve metabolic bottlenecks [15], and the mining of bacterial genomes for novel terpenoid synthases and modifying enzymes that outperform their eukaryotic counterparts in bacterial hosts [8]. The optimal choice between E. coli and S. cerevisiae, and by extension their native pathways, remains product-dependent, guided by target terpenoid structure, required post-synthetic modifications, and the overall design of the microbial cell factory.

Carbon Utilization and Metabolic Network Analysis

The selection of a microbial host for metabolic engineering is a foundational decision that significantly impacts the yield and efficiency of bioproduction processes. Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae represent the two most prominent platforms in industrial biotechnology. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of their carbon utilization efficiencies and metabolic network structures, with a specific focus on the production of terpenoids, a valuable class of natural products. While both organisms are well-characterized and possess advanced genetic toolkits, their intrinsic metabolic architectures lead to distinct advantages and limitations. E. coli, with its 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) pathway, demonstrates a superior theoretical carbon yield from glucose for terpenoid precursor synthesis. In contrast, S. cerevisiae, utilizing the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, offers physiological advantages as a eukaryotic host and shows a remarkable capacity to utilize non-fermentable carbon sources effectively [3] [17]. The following sections dissect these differences through quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visual network analysis to inform rational host selection.

Pathway Stoichiometry and Carbon Conversion Efficiency

The core metabolic pathways for isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) synthesis differ fundamentally between these two hosts, directly influencing carbon conversion efficiency.

Table 1: Stoichiometric Comparison of IPP Biosynthetic Pathways

| Feature | E. coli (DXP Pathway) | S. cerevisiae (MVA Pathway) |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Metabolites | Pyruvate + Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate [3] | 3 Acetyl-CoA [3] |

| Overall Stoichiometry | GAP + PYR + 3 NADPH + 2 ATP → IPP + CO₂ + 3 NADP⁺ + 2 ADP [3] | 3 AcCoA + 2 NADPH + 3 ATP → IPP + CO₂ + 2 NADP⁺ + 3 ADP [3] |

| Carbon Loss per IPP | 1 CO₂ [3] | 1 CO₂ [3] |

| Theoretical Max Yield (Glucose) | Higher [3] [17] | Lower [3] [17] |

| Primary Limitation | Energy & redox equivalent supply [3] | Carbon loss in Acetyl-CoA formation; Energy & redox equivalent supply [3] |

A critical insight from in silico analysis is that while the core DXP and MVA pathways themselves are identical in carbon yield when starting from their direct precursors, the story changes when considering the entire metabolic network from a common carbon source like glucose. The MVA pathway's reliance on acetyl-CoA introduces a significant carbon loss at the pyruvate dehydrogenase step, inherently reducing its maximum theoretical yield compared to the DXP pathway in this context [3] [17]. For both hosts, the theoretical maximum yield is further constrained by the network's ability to meet the pathways' substantial demands for ATP and NADPH [3].

Metabolic Network Analysis: Methodologies and Insights

Understanding the performance of these hosts requires computational techniques that analyze the entire metabolic network. The following experimental and in silico protocols are standard for such comparative analyses.

Key Experimental and In Silico Protocols

Elementary Mode Analysis (EMA):

- Function: A constraint-based method that identifies all unique, non-decomposable metabolic pathways (elementary modes) in a network under steady-state conditions. It does not require kinetic data or an objective function [3].

- Application in Host Comparison: EMA was used to calculate the theoretical maximum yield of IPP on different carbon sources for both E. coli and S. cerevisiae. It allows for a direct comparison of the metabolic capabilities of the two networks, independent of specific genetic regulations. This method also serves as a basis for computing intervention strategies, such as gene knockouts, to force the network toward high-yield production [3].

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA):

- Function: A widely used computational approach that predicts steady-state metabolic flux distributions in a genome-scale metabolic model (GSMM). It uses linear programming to optimize a cellular objective (e.g., biomass maximization or product synthesis) given stoichiometric and capacity constraints [18] [19].

- Application in Host Comparison: FBA can simulate growth and terpenoid production in GSMMs of E. coli and S. cerevisiae. By comparing the predicted flux distributions, researchers can identify host-specific bottlenecks, such as imbalanced cofactor usage or competing pathways. For example, FBA-based models have been used to study carbon partitioning in plants and can be analogously applied to microbes [19].

Carbon Flux Mapping (e.g., NetFlow):

- Function: An algorithm that leverages genome-scale carbon atom mapping to trace the path of carbon from a substrate to a product within a predicted flux distribution. It helps isolate and visualize the dominant production pathways [20].

- Application in Host Comparison: NetFlow can quantitatively distinguish the primary routes of carbon flow through the DXP versus MVA pathways in the context of the hosts' full metabolism. This is crucial for understanding the mechanistic basis for yield differences in engineered strains, such as identifying which knockouts successfully rerouted carbon toward the desired product [20].

Visualizing Carbon Utilization Pathways

The diagram below illustrates the integration of the DXP and MVA pathways into the central carbon metabolism of E. coli and S. cerevisiae, highlighting key carbon inputs and energy demands.

Diagram 1: Comparative Carbon Flow to IPP. The diagram highlights the key metabolic divergence: the DXP pathway in E. coli draws from glycolytic intermediates (pyruvate and GAP) directly, while the MVA pathway in S. cerevisiae requires acetyl-CoA, a node involving carbon loss as CO₂ [3].

Performance Across Different Carbon Substrates

The choice of carbon feedstock can significantly influence the performance of each host, as their metabolic networks interact with substrates in unique ways.

Table 2: Carbon Source Utilization Profile

| Carbon Source | E. coli Performance Rationale | S. cerevisiae Performance Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Superior theoretical yield for terpenoids via the DXP pathway [3] [17]. | Lower theoretical yield due to carbon loss in acetyl-CoA formation [3] [17]. |

| Xylose | Can be utilized; performance depends on strain background and pathway engineering. | Can be utilized; performance depends on strain background and pathway engineering. |

| Glycerol | Non-fermentable source; can be favorable for yield as it feeds into central metabolism upstream of key precursors [3]. | Non-fermentable source; can be favorable for yield [3]. |

| Ethanol | Not a standard carbon source for most lab strains. | Non-fermentable source; can be favorable for yield [3]. |

In silico studies suggest that for both organisms, non-fermentable carbon sources like glycerol and ethanol can be more promising for achieving high terpenoid yields than traditional fermentable sugars like glucose [3]. This is often related to more efficient generation of energy and redox equivalents or a more direct routing of carbon into the biosynthetic pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Metabolic Network Analysis

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Research | Example Application in Host Comparison |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | In silico representations of an organism's metabolism for simulation (e.g., via FBA) [18]. | Used to predict IPP flux and identify engineering targets in both E. coli and S. cerevisiae [3] [18]. |

| Constrained Minimal Cut Sets (cMCSs) | A computational algorithm to identify gene knockout strategies that force coupling of growth to product formation [3]. | Identified knockout strategies enforcing terpenoid yields higher than any published experimental value in both hosts [3]. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) | Enable experimental determination of intracellular metabolic fluxes (13C-MFA) [21] [22]. | Used to validate model predictions and measure carbon flow through the DXP vs. MVA pathways in engineered strains. |

| Pathway Reconstruction Tools (e.g., RetroPath 2.0) | Software for automated assembly of biosynthetic pathways into GSMMs, crucial for non-native products [18]. | Helps integrate heterologous terpenoid pathways or even the entire MVA pathway into E. coli for comparative studies [3] [18]. |

The decision between E. coli and S. cerevisiae is not a simple matter of declaring one superior to the other. Instead, it hinges on the specific priorities of the bioproduction process. For maximum theoretical carbon yield from glucose in terpenoid production, E. coli and its native DXP pathway present a clear stoichiometric advantage [3] [17]. However, S. cerevisiae is a robust eukaryotic host with a compartmentalized metabolism that can be advantageous for expressing complex plant-derived enzymes like P450s [3]. Furthermore, the potential of both hosts to utilize alternative, non-fermentable carbon sources opens avenues for more sustainable and efficient bioprocesses [3]. Future engineering efforts in both chassis will focus on overcoming the universal limitations of energy and redox cofactor supply, leveraging powerful in silico tools like cMCSs to design strains where high-yield production becomes a prerequisite for growth [3].

Established Genetic Tools and Model Organism Status

The selection of a microbial host is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering, with Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae emerging as the predominant chassis organisms. These two workhorses collectively account for nearly half of all metabolic engineering efforts over the past three decades [23]. Their prominence stems from decades of research establishing comprehensive genetic toolkits, well-annotated genomes, and extensive characterized phenotypes. E. coli, a Gram-negative bacterium, offers rapid growth, high transformation efficiency, and well-understood molecular genetics. S. cerevisiae, a eukaryotic yeast, provides the advantages of subcellular compartmentalization, post-translational modification capabilities, and generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status. This guide provides an objective comparison of their established genetic tools and model organism status, equipping researchers with the data necessary for informed host selection in metabolic engineering projects.

Comparative Analysis of Foundational Characteristics

The core attributes of E. coli and S. cerevisiae as metabolic engineering platforms are summarized in the table below, highlighting key distinctions that influence their application scope.

Table 1: Foundational Characteristics of E. coli and S. cerevisiae

| Characteristic | E. coli | S. cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| Classification | Prokaryote (Gram-negative bacterium) | Eukaryote (Unicellular yeast) |

| Generation Time | ~20 minutes [24] | ~90-120 minutes |

| Genetic Background | Exceptionally well-defined [25] | Well-defined, first sequenced eukaryotic genome |

| Cellular Organization | Simple, lacking organelles | Complex, with nucleus, ER, mitochondria, Golgi |

| Post-translational Modifications | Limited | Eukaryotic PTMs (e.g., glycosylation) |

| Preferred Cultivation | Simple, inexpensive media [25] | Defined media; more complex nutritional requirements |

| Tolerance to Toxic Metabolites | Can be engineered for high tolerance [24] | Naturally high tolerance to many inhibitors and products |

| Industrial Safety Profile | Requires containment (non-GRAS) | Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) |

| Native Product Spectrum | Organic acids, alcohols, recombinant proteins | Ethanol, organic acids, secondary metabolites, recombinant proteins |

The Genetic Toolkits: A Detailed Comparison

Both organisms boast a sophisticated arsenal of genetic tools, though with different strengths and specializations developed around their unique biology.

Genome Editing and Synthetic Biology Tools

Precision in genetic manipulation is paramount for metabolic engineering. The tools available for both hosts have evolved significantly, with CRISPR-based systems now representing the gold standard.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Genetic Engineering Tools

| Tool Category | E. coli | S. cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas Systems | Highly advanced; used for knockout, knockdown, and activation [26] [27] | Robust implementation for efficient genome editing [26] [6] |

| Recombineering | Highly efficient, based on λ Red/RecET systems [27] | Less common, typically relies on endogenous homologous recombination |

| Multiplexed Editing | MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) [26] [27] | eMAGE (eukaryotic MAGE) [26] |

| Classical Methods | Transposons, suicide plasmids [27] | High-efficiency transformation, plasmid-based expression |

| Cloning & Assembly | Extensive compatibility with standardized parts (BioBricks, etc.) | Advanced yeast assembly systems (e.g., Gibson Assembly, Yeast Toolkit) |

The application of CRISPR/Cas9 is particularly notable for its precision, using a 20-nucleotide RNA guide to direct the Cas9 nuclease to a specific genomic site, thereby reducing off-target effects and making the gene engineering process more efficient and reliable compared to earlier techniques [26]. Editing precision in E. coli using CRISPR/Cas can reach 80-90%, a significant improvement over the 10-40% efficiency of earlier techniques [27].

Tool Versatility and Applications

- Pathway Construction: Both hosts are routinely engineered with heterologous pathways. For example, the entire biosynthetic pathway for the nutraceutical ergothioneine (ERG) from bacteria and fungi has been successfully reconstituted in E. coli, demonstrating its capacity for complex pathway assembly [25].

- Multiplexed Engineering: Tools like MAGE allow for the simultaneous modification of multiple genomic locations in E. coli, dramatically accelerating strain optimization cycles [26] [27].

- Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE): E. coli's rapid division cycle (~20 minutes) makes it exceptionally suited for ALE experiments. Beneficial mutants with significantly improved phenotypes, such as ethanol tolerance, can be isolated in as few as 80 generations [24].

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Metabolic Capacity and Theoretical Yields

A systems-level analysis of metabolic networks provides a theoretical basis for host selection. Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) can calculate key metrics like the maximum theoretical yield (YT) and maximum achievable yield (YA) for a target chemical.

Table 3: Metabolic Capacity Comparison for Selected Chemicals (Glucose, Aerobic)

| Target Chemical | Host | Maximum Theoretical Yield (mol/mol Glucose) | Key Experimental Titer Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Lysine | S. cerevisiae | 0.8571 [28] | - |

| B. subtilis | 0.8214 [28] | - | |

| C. glutamicum | 0.8098 [28] | 223.4 g/L [29] | |

| E. coli | 0.7985 [28] | - | |

| L-Valine | E. coli | - | 59 g/L [29] |

| Succinic Acid | E. coli | - | 153.36 g/L [29] |

| Ergothioneine | E. coli BL21(DE3) | - | 5.4 g/L [25] |

| S. cerevisiae | - | 1.14 g/L [25] |

This data illustrates that while S. cerevisiae may show a higher theoretical yield for some compounds like L-lysine, E. coli has been engineered to achieve exceptionally high titers for a diverse range of products in industrial-scale fermentation.

Experimental Protocols for Host Engineering

Protocol 1: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout in E. coli [26] [27]

- gRNA Design: Design a 20-nucleotide guide RNA (gRNA) sequence complementary to the target genomic locus.

- Plasmid Construction: Clone the gRNA expression cassette and the Cas9 gene into a suitable E. coli expression vector. A homologous repair template for desired edits (if needed) can be included.

- Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into the E. coli strain via electroporation or chemical transformation.

- Selection and Screening: Plate cells on selective media and incubate. Screen individual colonies via colony PCR and DNA sequencing to confirm the precise genetic modification.

- Curing Plasmid: Propagate positive clones under non-selective conditions to lose the CRISPR plasmid, preparing the strain for subsequent engineering rounds.

Protocol 2: Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) for Enhanced Phenotype [24]

- Initial Strain & Conditions: Start with a genetically engineered base strain (e.g., E. coli or S. cerevisiae) and define the selective pressure (e.g., toxin tolerance, substrate utilization).

- Serial Transfer: Culture microbes in serial batch cultures, consistently transferring a small inoculum (e.g., 1-5% of culture volume) to fresh media before the stationary phase. This maintains continuous selection pressure.

- Monitoring: Track population growth (OD600) and, if applicable, product formation over hundreds of generations.

- Isolation and Genotyping: Isolate evolved clones from the endpoint population. Sequence their genomes to identify accumulated beneficial mutations responsible for the improved phenotype.

- Reverse Engineering: Introduce identified mutations into the parental strain to validate their functional impact.

Visualization of Metabolic Engineering Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for developing microbial cell factories and a specific pathway engineering example.

Diagram 1: The Systems Metabolic Engineering Cycle. This iterative process begins with project design and moves through host selection, pathway construction, flux optimization, and experimental validation, with feedback loops informing earlier stages [29] [28].

Diagram 2: Heterologous Ergothioneine Biosynthesis Pathways. Engineered E. coli can utilize genes from both bacterial (red) and fungal (blue) pathways. The fungal pathway is often preferred for its efficiency, as it bypasses the γ-GC intermediate, reducing metabolic competition with glutathione synthesis [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful metabolic engineering relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for genetic manipulation and strain development in these chassis organisms.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | Precise genome editing via RNA-guided DNA cleavage. | Gene knockouts, knock-ins, and transcriptional regulation in both E. coli and S. cerevisiae [26] [27] [6]. |

| OptimumGene/Codon Optimization | Algorithmic optimization of gene sequences for enhanced heterologous expression. | Critical for maximizing protein expression levels when transferring genes across species [30]. |

| GenBrick Long DNA Synthesis | De novo synthesis of large DNA constructs (8-15 kb). | Enables assembly of entire metabolic pathways or large enzyme clusters for heterologous expression [30]. |

| MAGE/eMAGE Platforms | Automated, multiplexed genome engineering. | Allows simultaneous introduction of multiple genomic changes across a population of E. coli (MAGE) or S. cerevisiae (eMAGE) cells [26]. |

| Inducible Promoter Systems | Tightly regulated control of gene expression (e.g., T7, pLac, GAL1). | Essential for expressing toxic genes or dynamically controlling metabolic flux [27]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico models of metabolic networks. | Used to predict metabolic capacity, identify gene knockout targets, and simulate flux for optimal chemical production [29] [28]. |

E. coli and S. cerevisiae remain the preeminent chassis organisms in metabolic engineering, each supported by a deep repository of genetic tools and biological knowledge. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with project goals.

- Choose E. coli when the priority is maximizing speed and yield. Its rapid growth, high transformation efficiency, advanced tools for multiplexed genome editing (CRISPR, MAGE), and proficiency in producing a wide array of organic acids, alcohols, and recombinant proteins make it ideal for high-throughput engineering and scalable fermentation processes [24] [27] [25].

- Choose S. cerevisiae when project requirements include eukaryotic complexity and safety. Its GRAS status, native tolerance to many inhibitors, ability to perform complex post-translational modifications, and robust performance in industrial ethanol production make it the host of choice for food-grade products, complex natural plant pathways, and processes utilizing lignocellulosic hydrolysates [26] [23] [6].

Ultimately, the "established" status of both organisms continues to be reinforced by relentless tool development, making them more malleable and powerful than ever for the sustainable production of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and materials.

Advanced Engineering Strategies and Production Case Studies

Metabolic engineering has emerged as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, enabling the rewiring of cellular metabolism to produce valuable chemicals, biofuels, and pharmaceuticals from renewable resources. The field has evolved through distinct waves of innovation, from initial rational pathway engineering to systems biology approaches, and into the current era dominated by synthetic biology [29]. Central to this progress are three fundamental genetic interventions: overexpression, knockout, and knockdown. These strategies are pivotal for optimizing microbial cell factories, with Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae serving as the predominant model organisms [26]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these core interventions, framed within the broader context of evaluating E. coli versus S. cerevisiae as metabolic engineering hosts, and is supported by experimental data and protocols relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

The primary goal of metabolic engineering is to redesign cellular metabolism to achieve enhanced production of target compounds. This is accomplished by manipulating the genetic blueprint of an organism to control the flow of metabolites through its biochemical network. Overexpression, knockout, and knockdown represent the three primary levers for this manipulation. Overexpression involves increasing the expression level of a gene, typically to amplify the flux through a rate-limiting enzymatic step. Knockout is the complete and permanent inactivation of a gene, often used to eliminate competing pathways or regulatory bottlenecks. Knockdown, a more subtle approach, refers to the partial reduction of gene expression, which can be useful for fine-tuning metabolic flux without completely disrupting essential pathways [29] [26]. The application and success of these strategies are highly dependent on the host organism. E. coli, a prokaryotic workhorse, offers rapid growth, well-characterized genetics, and extensive molecular toolkits. In contrast, the eukaryotic S. cerevisiae provides a robust, generally recognized as safe (GRAS) organism with a natural capacity for compartmentalization and post-translational modifications, making it suitable for producing complex natural products [26] [31]. The choice between them often hinges on the specific pathway requirements and the desired product.

Comparative Analysis of Intervention Strategies

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and experimental methodologies for overexpression, knockout, and knockdown.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key metabolic engineering interventions.

| Intervention | Definition & Impact | Primary Applications | Common Experimental Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overexpression | Increasing the copy number or transcription/translation efficiency of a gene to enhance enzyme concentration and reaction flux [26]. | - Amplifying flux through rate-limiting steps in a biosynthetic pathway.- Expressing heterologous enzymes in a new host.- Balancing expression of multiple genes in an operon or synthetic pathway [31] [32]. | - Plasmid-based expression with strong promoters (e.g., T7, pLac in E. coli; PGK1, ADH1 in S. cerevisiae).- Chromosomal integration via homologous recombination.- Promoter engineering to tune expression levels. |

| Knockout | Complete, permanent inactivation of a target gene to eliminate a metabolic reaction [33]. | - Blocking competitive pathways to redirect carbon flux toward the desired product.- Removing regulatory proteins that repress a target pathway.- Simplifying metabolic networks to minimize by-product formation [29] [34]. | - CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption.- Lambda Red recombinase system (in E. coli).- Replacement of the gene with a selectable marker via homologous recombination. |

| Knockdown | Partial reduction of gene expression at the mRNA or protein level, allowing for fine-tuning of metabolic flux [35]. | - Attenuating, but not eliminating, essential metabolic reactions.- Fine-tuning branch-point fluxes in central metabolism.- Reducing metabolic burden without causing lethality. | - CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) with a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9).- Antisense RNA (asRNA) technology.- Use of weak promoters or ribosomal binding site (RBS) engineering. |

Host-Specific Application: E. coli vs. S. cerevisiae

The implementation and effectiveness of genetic interventions vary significantly between E. coli and S. cerevisiae due to their fundamental biological differences. The following table compares how these strategies are applied in each host to achieve metabolic engineering goals, citing specific examples and achieved outcomes.

Table 2: Host-specific application and performance of metabolic engineering interventions.

| Host & Strategy | Engineering Objective | Specific Intervention | Experimental Outcome | Notable Advantage/Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Overexpression | Enhance squalene production, a triterpene [32]. | Overexpression of a hybrid HMGR (3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase) system for balanced cofactor utilization. | Production reached 852.06 mg/L; further engineering boosted it to 1267.01 mg/L in a bioreactor. | Advantage: Well-established tools for high-level protein expression and cofactor engineering. |

| S. cerevisiae Overexpression | Produce succinic acid under low-pH conditions [34]. | Overexpression of key reductive TCA cycle enzymes like phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK) and pyruvate carboxylase (PYC). | Engineered strains achieved SA titers of >110 g/L from glycerol, simplifying downstream processing. | Advantage: Natural acid tolerance allows production of the acid form, reducing purification costs. |

| E. coli Knockout | Enable growth-coupled production of L-methionine [33]. | Computational prediction and implementation of multiple gene knockouts to force coupling between growth and product synthesis. | Strategy enforced product yield; specific yield data was a key ranking metric in the study. | Advantage: Fast growth enables rapid screening of multiple knockout strains. |

| S. cerevisiae Knockout | Increase flux towards succinic acid [34]. | Deletion of SDH2 and SDH5 genes encoding subunits of succinate dehydrogenase. | Knockout strains achieved SA titers of 45.5 g/L to 160.2 g/L, depending on the strain and conditions. | Disadvantage: Longer generation time can slow the construction and testing cycle. |

| E. coli Knockdown | Rewire central metabolism for chemical overproduction [35]. | Using regulatory elements (e.g., RBS engineering, CRISPRi) to fine-tune the expression of branch-point enzymes. | Improved product yield and selectivity by avoiding accumulation of inhibitory intermediates. | Advantage: Precise tunability is valuable for balancing complex, essential pathways. |

| S. cerevisiae Knockdown | Dynamically control metabolic flux [35]. | CRISPRi with dCas9 to repress, but not eliminate, genes in competitive pathways. | Allows for dynamic redirection of flux during fermentation, optimizing growth and production phases. | Advantage: Eukaryotic gene regulation tools can offer more sophisticated control. |

Experimental Workflow for Strain Design and Validation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for designing and validating a metabolically engineered strain, integrating computational and experimental biology approaches commonly used for both E. coli and S. cerevisiae.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout in E. coli

This protocol is adapted from methods used in recent metabolic engineering studies [26] [32].

- Design and Synthesis: Design a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence (20 nucleotides) specific to the target gene. Synthesize the sgRNA and a donor DNA template if a specific edit or repair is needed.

- Plasmid Transformation: Co-transform the E. coli host strain with a plasmid expressing the Cas9 protein and the sgRNA. A second plasmid or linear DNA fragment containing homologous regions for repair can be co-transformed for precise edits.

- Selection and Screening: Plate transformed cells on selective media containing the appropriate antibiotic(s). Incubate to allow for colony formation.

- Verification: Screen individual colonies for the desired knockout via colony PCR to check for the absence of the target gene or the presence of an insertion/deletion. Sequence the target locus to confirm the genetic modification.

- Curing the Plasmid: To remove the CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid, streak positive colonies onto non-selective media and screen for antibiotic-sensitive clones.

Protocol for Metabolic Flux Analysis Using FBA

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a key computational method for predicting intervention targets [35] [36].

- Model Selection/Upload: Select a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for your host organism (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli, iMM904 for S. cerevisiae) or upload a custom model in Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) format to a tool like Fluxer [36].

- Define Constraints: Set constraints based on experimental conditions, including the carbon source uptake rate (e.g., glucose), oxygen uptake rate, and any known secretion rates.

- Set Objective Function: Define the objective function for the linear programming problem. This is typically the biomass reaction for simulating growth or the exchange reaction for a target product.

- Run Simulation: Perform FBA to obtain a flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes the objective function. Tools like Fluxer automate this calculation [36].

- Analyze Results: Interpret the flux distribution to identify key pathways, potential bottlenecks, and candidate reactions for genetic interventions (overexpression, knockout, or knockdown).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists key reagents, software, and resources essential for conducting metabolic engineering research in E. coli and S. cerevisiae.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and solutions for metabolic engineering.

| Category | Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Biology Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 System [26] | Enables precise gene knockouts, knock downs (via CRISPRi), and edits in both hosts. |

| Plasmid Vectors with Strong Promoters (e.g., pET, pRS series) [31] | For stable or transient gene overexpression and heterologous pathway expression. | |

| Homologous Recombination Systems (e.g., Lambda Red) [35] | Facilitates precise chromosomal integration of genes or regulatory elements. | |

| Computational Resources | Genome-Scale Models (GEMs) [33] [35] | In silico representations of metabolism for predicting flux and identifying intervention targets. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) Software (e.g., Fluxer, COBRA Toolbox) [36] | Computes steady-state metabolic fluxes to simulate and optimize strain designs. | |

| Analytical Techniques | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) / GC-MS | Quantifies titers of target products, substrates, and key metabolites in fermentation broth. |

| Spectrophotometer / Plate Reader | Measures cell density (OD600) to monitor microbial growth kinetics. |

The strategic application of overexpression, knockout, and knockdown forms the foundation of modern metabolic engineering. The choice between these interventions is deeply intertwined with the selection of the host organism. E. coli often allows for faster implementation of designs and higher growth rates, while S. cerevisiae offers advantages in process robustness, acid tolerance, and production of complex eukaryotic molecules. The future of the field lies in the intelligent integration of computational design, advanced gene-editing tools like CRISPR, and high-throughput screening to create next-generation cell factories. As the tools and databases for both hosts continue to mature, the decision framework will increasingly rely on sophisticated in silico models to predict the optimal host and the most effective combination of genetic interventions for a given product [29] [35].

The choice of a microbial host is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering, critically influencing the success of any pathway optimization effort. Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have emerged as the two most predominant platforms for the production of valuable chemicals and pharmaceuticals. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, focusing on the critical challenge of balancing precursor and co-factor supply—a key determinant of pathway efficiency and product yield. We evaluate both systems through experimental case studies, presenting quantitative data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their host selection process.

Core Engineering Objectives: Effective pathway engineering requires simultaneous optimization of several interconnected systems:

- Precursor Supply: Ensuring the metabolic chassis can generate sufficient starting materials for the target pathway.

- Cofactor Regeneration: Balancing redox cofactors (NADPH, NADH, FADH2) and energy carriers (ATP) to drive biosynthetic reactions.

- Flux Control: Modulating competing pathways to direct carbon toward the desired product.

- Toxic Intermediate Management: Preventing accumulation of harmful pathway intermediates.

Comparative Performance Analysis: E. coli vs. S. cerevisiae

The table below summarizes quantitative production data from recent metabolic engineering achievements in both hosts, specifically highlighting strategies that enhanced precursor and co-factor supply.

Table 1: Comparative Production Data from Pathway Engineering Case Studies

| Host Organism | Target Compound | Engineering Strategy for Precursor/Cofactor Balance | Maximum Titer Achieved | Key Limiting Factor Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli [37] | Dopamine | FADH2-NADH supply module; Two-stage pH fermentation; Fe²⁺/ascorbic acid feeding | 22.58 g/L (5 L bioreactor) | Cofactor (FADH2) supply; Dopamine oxidation |

| E. coli [38] | D-pantothenic acid (D-PA) | Cofactor (CH2-THF) regeneration via serine-glycine pathway; β-alanine dosing | 19.52 g/L (Fed-batch, with β-alanine) | Cofactor (CH2-THF) & precursor (β-alanine) supply |

| S. cerevisiae [39] | Salidroside | Enhanced UDP-glucose supply via truncated sucrose synthase (tGuSUS1) | 18.9 g/L (Fed-batch) | Glycosylation precursor (UDP-glucose) supply |

| S. cerevisiae [39] | Hydroxytyrosol | Integration of PaHpaB and EcHpaC for hydroxylation | 677.6 mg/L (15 L bioreactor) | Precursor (tyrosol) hydroxylation efficiency |

| S. cerevisiae [40] | Taxadiene | Combinatorial upstream MVA pathway enhancement; Fusion proteins (GGPPS-ERG20) | 528 mg/L (Shake flask) | Precursor (FPP/GGPP) flux and toxic intermediate balance |

| S. cerevisiae [41] | α-Santalene | NADPH boost via GDH1 deletion/GDH2 overexpression; ERG9 down-regulation | 0.036 Cmmol/gDCW/h (Productivity) | Cofactor (NADPH) supply & precursor (FPP) competition |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Pathway Balancing

Protocol: Enhancing Cofactor Supply in E. coli for Aromatic Compound Production

This protocol is adapted from the high-yield dopamine production study in E. coli W3110 [37].

Objective: To construct a plasmid-free, high-yield dopamine strain by engineering the cofactor supply and optimizing fermentation conditions to minimize degradation.

Materials:

- Chassis Strain: E. coli W3110.

- Key Enzymes: Hydroxylase (HpaB), Flavin reductase (HpaC) from E. coli BL21(DE3), and Dopamine decarboxylase (DmDdc) from Drosophila melanogaster.

- Fermentation Medium: Defined minimal medium with appropriate carbon source (e.g., glucose).

- Analytical Equipment: HPLC for dopamine quantification.

Methodology:

- Strain Construction:

- Knockout Degradation Pathway: Delete the gene encoding tyramine oxidase (

tynA) to prevent dopamine oxidation. - Integrate Biosynthetic Module: Constitutively integrate the

hpaBCgenes for L-DOPA synthesis and theDmDdcgene for decarboxylation into the genome. - Promoter Optimization: Use promoters of varying strengths (e.g., T7, trc, M1-93) to balance the expression of

hpaBCandDmDdc, preventing intermediate accumulation. - Cofactor Module: Engineer an FADH2-NADH supply module to support the HpaBC hydroxylation reaction.

- Knockout Degradation Pathway: Delete the gene encoding tyramine oxidase (

- Fermentation Strategy:

- Two-Stage pH Control:

- Stage 1 (Biomass Growth): Maintain pH at 6.8-7.0 for optimal cell growth.

- Stage 2 (Production Phase): Lower pH to 5.5 to reduce chemical degradation of dopamine.

- Cofactor Stabilization Feeding: Implement a combined feeding strategy of Fe²⁺ and ascorbic acid to stabilize dopamine and support enzyme activity.

- Two-Stage pH Control:

Protocol: Balancing the Mevalonate Pathway in S. cerevisiae for Terpene Production

This protocol synthesizes strategies from taxadiene and α-santalene production studies [41] [40].

Objective: To increase the flux through the mevalonate (MVA) pathway toward FPP/GGPP-derived terpenes while managing redox balance and toxicity.

Materials:

- Chassis Strain: S. cerevisiae CEN.PK113-5D or an engineered derivative (e.g., SCIGS22a).

- Key Enzymes: tHMG1 (truncated HMG-CoA reductase), ERG20 (FPP synthase), heterologous GGPPS (for diterpenes), and terpene synthase (e.g., Taxadiene Synthase).

- Vectors: Episomal (YEp) and integrative (YIp) plasmids for combinatorial expression.

- Culture Medium: Defined minimal medium for shake-flask and bioreactor cultivations.

Methodology:

- Upstream Pathway Engineering:

- Boost MVA Flux: Overexpress a truncated, deregulated version of

HMG1(tHMG1) to overcome feedback inhibition. For greater enhancement, overexpress all six MVA pathway genes (ERG10,ERG13,ERG12,ERG8,ERG19,IDI). - Optimize FPP Branch Point: Overexpress

ERG20(FPP synthase). To favor diterpene precursors, create a fusion protein between ERG20 and a heterologous GGPPS. - Downregulate Competition: Replace the native promoter of

ERG9(squalene synthase) with a weaker or regulated promoter (e.g.,P_HXT1) to reduce carbon loss to sterols. - Delete Phosphatases: Knock out

LPP1andDPP1to prevent dephosphorylation of FPP to farnesol.

- Boost MVA Flux: Overexpress a truncated, deregulated version of

Cofactor Balancing:

- Increase NADPH Supply: Delete the

GDH1gene (encoding NADPH-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase) and overexpress theGDH2gene (encoding NADH-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase). This shifts ammonium assimilation to an NADH-consuming process, increasing the NADPH/NADH ratio.

- Increase NADPH Supply: Delete the

Combinatorial Screening:

- Construct a library of strains with varying copy numbers and combinations of key pathway genes (e.g.,

tHMG1,ERG20,GGPPS, synthase) using different plasmid systems. - Screen the library in shake flasks to identify strains with a balanced pathway that minimizes the toxicity of intermediates like taxadiene.

- Construct a library of strains with varying copy numbers and combinations of key pathway genes (e.g.,

Visualizing the Engineering Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key engineering modules for optimizing precursor and co-factor supply in a microbial host, integrating the strategies described in the protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful pathway engineering relies on a suite of molecular biology and fermentation tools. The table below lists key reagents and their specific functions in optimizing precursor and co-factor supply.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Type | Specific Example | Function in Pathway Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Chassis Strains | E. coli W3110 [37] | Defined genetic background, suitable for plasmid-free, stable production strain construction. |

| S. cerevisiae CEN.PK113-5D [40] | Robust, genetically tractable laboratory strain with well-characterized physiology. | |

| Key Enzymes/Genes | HpaBC (Hydroxylase/Reductase) [37] [39] | Catalyzes aromatic ring hydroxylation, requires FADH2 cofactor supply. |

| tHMG1 (Truncated HMG-CoA reductase) [41] [40] | Bypasses regulatory feedback in the mevalonate pathway, increasing precursor flux. | |

| GGPPS-TS Fusion Protein [40] | Channels precursor (GGPP) directly to the product (taxadiene), improving yield and reducing toxicity. | |

| Fermentation Additives | Fe²⁺ and Ascorbic Acid [37] | Reduces oxidation of sensitive products (e.g., dopamine) during fermentation. |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 System [39] | Enables precise gene knockouts, integrations, and multiplexed genome editing. |

| Promoter Libraries (T7, trc, M1-93) [37] | Allows fine-tuning of gene expression to balance metabolic flux and prevent bottlenecks. | |

| Episomal (YEp) & Integrative (YIp) Plasmids [42] [40] | Provides flexibility for testing gene copy number effects and ensuring genetic stability. |

The experimental data and protocols presented demonstrate that both E. coli and S. cerevisiae are capable of achieving high titers when pathway engineering effectively addresses precursor and co-factor supply constraints.

- E. coli often excels in rapid cycle times and can achieve very high titers for compounds whose pathways align well with its native metabolism and cofactor pools, as evidenced by the >20 g/L production of dopamine [37]. Its prokaryotic nature can be a limitation for expressing complex eukaryotic enzymes or managing the production of toxic intermediates.

- S. cerevisiae, as a eukaryotic host, is inherently better suited for expressing plant-derived enzymes and producing complex terpenoids and glycosylated compounds [39] [40]. Its compartmentalized metabolism provides natural modules for engineering, though balancing redox cofactors within organelles presents additional challenges.

The overarching trend in the field is a move toward combinatorial and modular engineering strategies [40] [43] rather than single-gene edits. The most successful projects, regardless of host, involve iterative cycles of design, construction, testing, and learning (DBTL), leveraging tools like CRISPR-Cas9 [39] and multi-omics analysis to identify the next limiting factor. The choice between E. coli and S. cerevisiae should therefore be guided by the specific pathway requirements, the need for post-translational modifications, and the toxicity profile of the target molecule and its intermediates.

The selection of an appropriate host organism is a foundational decision in metabolic engineering, with Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae emerging as the predominant workhorses for industrial biotechnology. These organisms represent a fundamental divide in biology: E. coli as a well-characterized prokaryotic system with rapid growth and high transformation efficiency, and S. cerevisiae as a robust eukaryotic host with complex cellular organization and generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status. The engineering of these organisms has been revolutionized by three transformative technologies: Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) for rapid, scalable genome editing; CRISPR/Cas9 for precise, targeted DNA manipulation; and genome-scale models for in silico prediction of metabolic behavior. When integrated, these technologies create a powerful framework for systematic strain optimization. This review provides a comparative analysis of these tools applied to E. coli and S. cerevisiae, examining their performance, experimental requirements, and suitability for specific metabolic engineering applications, thereby offering guidance for researchers selecting an appropriate chassis for their specific production goals.

Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE)

Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering is a high-throughput technology that enables rapid, iterative genome editing using single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotides. The process leverages the λ Red recombinase system (comprising Exo, Beta, and Gam proteins) to incorporate synthetic oligonucleotides into the chromosome during DNA replication [44] [45]. In E. coli, this system has been highly optimized, with efficiencies significantly boosted by transiently suppressing the mismatch repair (MMR) system [44]. The technology is particularly powerful for programming and evolving cells by submitting them to multiple cycles of recombineering with oligonucleotide cocktails carrying diverse mutations [45]. This allows metabolic engineers to explore vast combinatorial genetic spaces for strain improvement.

While MAGE was pioneered in E. coli, its application in S. cerevisiae and other non-model organisms has been more challenging due to lower recombination efficiencies and differences in cellular physiology [45]. In yeast, homologous recombination is more efficient than in bacteria, but the automation and scalability aspects of MAGE have been difficult to implement with comparable efficiency. Recent efforts have focused on adapting MAGE-like approaches for eukaryotic systems, though often with modified protocols and terminology, such as "High-efficiency multi-site genomic editing" (HEMSE) developed for Pseudomonas putida [45].

CRISPR/Cas9 and CRMAGE

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering by providing programmable, RNA-guided nucleases that create double-strand breaks at specific genomic locations. When coupled with MAGE, it creates a powerful editing platform known as CRISPR-optimized MAGE (CRMAGE) [44]. This hybrid approach uses CRISPR/Cas9 counterselection against wild-type sequences to dramatically enrich for successfully engineered cells, increasing recombineering efficiency from traditional MAGE rates of 0.68%-6% to impressive 70%-99.7% for various types of modifications in E. coli [44].

The CRMAGE system typically employs two plasmids: one expressing the λ Red β-protein and CRISPR/Cas9, and a second "recycling plasmid" containing an inducible sgRNA for negative selection and a "self-destruction" gRNA cassette that targets the vector's own backbone to enable plasmid curing and sequential engineering rounds [44]. This sophisticated system allows multiple engineering cycles per day, significantly accelerating metabolic engineering workflows.

Table 1: CRMAGE Editing Efficiencies in E. coli

| Modification Type | Traditional Recombineering Efficiency | CRMAGE Efficiency | Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene recoding | 0.68% - 5.4% | 96.5% - 99.7% | 18x - 142x |

| RBS substitution/small insertion | ~6% | ~70% | ~12x |

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs)

Genome-scale metabolic models are in silico reconstructions of an organism's metabolic network that enable computational prediction of physiological states and metabolic capabilities under different genetic and environmental conditions [46] [47]. These models are built using annotated genome sequences, biochemical literature, and experimental data, representing all known metabolic reactions, genes, and enzymes in a structured format.

For E. coli, extensive GEMs have been developed and refined over decades, with the most recent iterations incorporating regulatory information and expression constraints [46]. For S. cerevisiae, the first comprehensive genome-scale metabolic network reconstruction accounted for 708 structural open reading frames (ORFs) corresponding to 1,035 metabolic reactions, with an additional 140 reactions included based on biochemical evidence [47]. More recent advances include yETFL, a model that integrates expression constraints and reaction thermodynamics for S. cerevisiae, accounting for the compartmentalized nature of eukaryotic cells [48].

Table 2: Comparison of Genome-Scale Modeling Approaches

| Feature | E. coli Models | S. cerevisiae Models |

|---|---|---|

| Compartments | Typically 1-2 (cytosol, periplasm) | Multiple (cytosol, mitochondria, nucleus, etc.) |

| Expression Machinery | Single RNA polymerase and ribosome | Multiple RNA polymerases and ribosomes (nuclear, mitochondrial) |

| Thermodynamic Constraints | Yes (in advanced models) | Yes (e.g., yETFL) |

| Representative Models | iJO1366, ETFL | Yeast8, yETFL |

| Reactions | ~2,500-3,000 | ~1,200-4,000 |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

CRMAGE Protocol for E. coli

The CRMAGE workflow involves carefully orchestrated steps to achieve highly efficient multiplex genome editing [44]:

Strain Preparation: The target E. coli strain is transformed with two plasmids: pMA7CR_2.0 (expressing λ Red β-protein and CRISPR/Cas9) and pMAZ-SK (containing inducible sgRNA and self-targeting gRNA).

Recombinase Induction: λ Red recombinase expression is induced using L-arabinose to prepare cells for recombineering.

Oligo Electroporation: Synthetic ssDNA oligonucleotides (70-90 bases) containing desired mutations are electroporated into induced cells. For multiplex editing, multiple oligonucleotides can be combined in a single reaction.

CRISPR Counterselection: Cas9 expression is induced with anhydrotetracycline to eliminate unmodified cells that retain the original DNA sequence.

Plasmid Curing: The "self-destruction" gRNA cassette is induced with L-rhamnose and aTetracycline to eliminate both plasmids, allowing for subsequent engineering cycles.

Screening and Verification: Successful edits are verified by colony PCR and sequencing.

This protocol enables introduction of at least two mutations in a single recombineering round with efficiencies exceeding 96% for some applications [44].

Genome-Scale Modeling Workflow

The development and application of genome-scale models follows a systematic process [46] [47]:

Network Reconstruction:

- Compile organism-specific metabolic reactions from genomic annotations (KEGG, EcoCyc, MetaCyc) and biochemical literature

- Determine reaction stoichiometry, compartmentalization, and gene-protein-reaction associations

- Define biomass composition based on experimental measurements

Model Validation:

- Test predictive accuracy against experimental growth data

- Verify essential gene predictions against knockout studies

- Validate metabolic capabilities under different nutrient conditions

Constraint-Based Analysis:

- Apply flux balance analysis (FBA) to predict metabolic fluxes

- Incorporate additional constraints (enzyme kinetics, thermodynamics)

- Simulate gene knockouts, heterologous pathway insertion, or nutrient perturbations

Strain Design:

- Identify gene knockout targets to optimize product yield

- Predict optimal flux distributions for target metabolite production

- Design non-native pathways for chemical production

For eukaryotic organisms like S. cerevisiae, special considerations include compartmentalization of reactions, multiple RNA polymerases and ribosomes, and transport between cellular compartments [48] [47].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Editing Efficiency and Multiplexing Capacity

When comparing genome editing capabilities between E. coli and S. cerevisiae, distinct patterns emerge. E. coli consistently demonstrates higher efficiency in recombineering-based approaches like MAGE and CRMAGE, with reported efficiencies reaching 96.5%-99.7% for single nucleotide changes and approximately 70% for RBS substitutions or small insertions using CRMAGE [44]. The ability to perform highly efficient multiplexed editing in E. coli enables rapid prototyping of metabolic pathways and combinatorial strain optimization.

In contrast, S. cerevisiae generally shows higher efficiency in homologous recombination-based methods, a characteristic that has been leveraged for traditional genetic engineering but presents challenges for MAGE implementation. The more complex eukaryotic architecture of yeast, including chromatin organization and DNA repair mechanisms, influences editing efficiency and requires adaptation of protocols developed for prokaryotic systems [45].

Metabolic Modeling Sophistication

Genome-scale models for both organisms have undergone extensive refinement, but address different biological challenges. E. coli models benefit from the organism's relative simplicity and extensive experimental characterization, resulting in highly accurate predictions of metabolic behavior. The latest models incorporate thermodynamic constraints and expression limitations, enhancing their predictive capabilities [46].

S. cerevisiae models must account for eukaryotic complexity, particularly compartmentalization of metabolism between organelles. The yETFL model represents a significant advancement by integrating RNA and protein synthesis with traditional metabolic models, while considering the compartmentalized expression system and energetic costs of biological processes [48]. This enables more realistic simulation of eukaryotic metabolism but increases model complexity and computational requirements.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Engineering Technologies in E. coli vs S. cerevisiae

| Parameter | E. coli | S. cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|

| MAGE Efficiency | High (with CRMAGE: >96% for recoding) | Lower, requires protocol adaptation |

| Homologous Recombination | Lower efficiency | Naturally high efficiency |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery | Straightforward | More challenging due to cell wall |

| Multiplex Editing Capacity | High (CRMAGE) | Moderate |

| Model Predictive Accuracy | High for central metabolism | Good, improved with compartmentalization |

| Pathway Engineering | Excellent for prokaryotic pathways | Preferred for eukaryotic pathways |

Case Study: L-Tryptophan Biosynthesis

The contrasting strengths of E. coli and S. cerevisiae as metabolic engineering hosts are well-illustrated by comparing their use in L-tryptophan production. Both organisms share the same fundamental biosynthetic pathway comprising central metabolism, the shikimic acid pathway, and the chorismate pathway [49]. However, regulatory mechanisms and engineering strategies differ significantly.

In E. coli, key engineering strategies for enhancing L-tryptophan production include:

- Modification of the phosphotransferase system (PTS) to increase intracellular phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) levels, a key precursor

- Overexpression of pps (phosphoenolpyruvate synthase) and tktA (transketolase) to boost precursor supply

- Downregulation of feedback inhibition in the shikimic acid and chorismate pathways

In S. cerevisiae, different challenges and opportunities emerge:

- The endogenous regulation of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis involves complex feedback mechanisms

- Compartmentalization of pathway enzymes between cytosol and mitochondria must be considered

- The eukaryotic protein folding machinery may better express complex eukaryotic enzymes for trp-derived compound synthesis

Notably, engineering S. cerevisiae for L-tryptophan production has implications beyond yield, as tryptophan metabolism is linked to stress tolerance, potentially enabling development of more robust production strains [49].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Advanced Genome Engineering

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|