ecFactory: A Computational Pipeline for Predicting Metabolic Engineering Gene Targets

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the ecFactory computational pipeline, a method designed for the systematic prediction of gene targets in metabolic engineering.

ecFactory: A Computational Pipeline for Predicting Metabolic Engineering Gene Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the ecFactory computational pipeline, a method designed for the systematic prediction of gene targets in metabolic engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles that underpin the pipeline, which integrates the FSEOF algorithm with enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecModels) to identify targets for overexpression, knock-down, or knock-out. The scope includes a detailed, step-by-step guide to its methodology and application in projects like enhancing 2-phenylethanol and heme production in yeast. Furthermore, the article addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies and conducts a critical validation and comparison of ecFactory's performance against other computational approaches, highlighting its role in accelerating the development of efficient microbial cell factories for valuable chemicals.

The Foundation of ecFactory: Principles and Core Concepts for Predictive Metabolic Engineering

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) is a powerful computational framework for analyzing metabolism at the genome scale. This approach uses genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), which are in silico representations of an organism's entire metabolic network, encompassing all known metabolic reactions and associated genes [1]. CBM operates on the principle of imposing physical and biochemical constraints—such as mass-balance, reaction reversibility, and enzyme capacity—to define a feasible solution space of possible metabolic behaviors, rather than seeking a single unique solution [1]. This makes it particularly valuable for studying complex systems where precise kinetic parameters are unavailable.

The primary methodology for simulating these models is Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). FBA identifies an optimal metabolic flux distribution within the solution space, typically by maximizing an objective function such as biomass production, which serves as a proxy for cellular growth [1]. The ability to predict metabolic phenotypes from genomic information has led to widespread applications of CBM in biotechnology for strain engineering and in biomedicine for understanding host-microbiome interactions and disease mechanisms [2] [3] [4].

From GEMs to Enzyme-Constrained Models (ecModels)

Standard GEMs have a key limitation: they typically do not explicitly account for the proteomic costs of metabolism, such as the cellular investment in enzyme synthesis and the catalytic capacity of enzymes. Enzyme-constrained models (ecModels) address this gap by incorporating enzyme kinetics and proteomic constraints into the modeling framework [5].

The GECKO (Enzyme-Constrained using Kinetic and Omics data) toolbox was developed to enhance existing GEMs with these enzymatic constraints. GECKO expands a conventional GEM by incorporating three key elements [5]:

- Enzyme Pseudoreactions: Reactions that represent the consumption of resources for enzyme production.

- kcat Constraints: The incorporation of enzyme turnover numbers (

kcat) to define the catalytic capacity of an enzyme, thereby setting a maximum flux for its associated reaction. - Total Enzyme Pool Constraint: A global constraint that reflects the limited total protein mass available for metabolic enzymes.

The latest version, GECKO 2.0, features an automated framework for building and updating ecModels, supports a wider range of organisms, and includes improved algorithms for matching and applying kinetic parameters from databases like BRENDA [5]. This toolbox has been used to generate ecModels for key model organisms, including S. cerevisiae, E. coli, and H. sapiens [5] [6].

Table 1: Key Components of the GECKO Toolbox for Constructing ecModels

| Component | Description | Function in Model Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Database | Kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat values) sourced from BRENDA. | Provides catalytic rates to constrain reaction fluxes. |

| GEM Importer | Integrates a standard genome-scale metabolic model. | Provides the stoichiometric core network. |

| Enzyme Addition Module | Adds enzyme usage pseudoreactions and links them to metabolic genes. | Introduces proteomic costs into the metabolic network. |

| kcat Matching Algorithm | Hierarchical procedure for assigning kcat values to reactions. | Fills gaps in kinetic data, even for less-studied organisms. |

| Proteomics Integrator | Module for incorporating absolute proteomics data. | Constrains enzyme levels based on experimental measurements. |

| Simulation Utilities | Functions for simulating growth and phenotypes with ecModels. | Enables prediction of metabolic behavior under constraints. |

The ecFactory Pipeline for Predicting Gene Targets

The ecFactory method is a computational pipeline that leverages ecModels for the systematic identification of metabolic engineering targets. It combines the principles of FSEOF (Flux Scanning with Enforced Objective Function) with the enhanced predictive power of enzyme-constrained models [7]. The primary goal of ecFactory is to pinpoint genes for overexpression, knock-down, or knock-out to enhance the production of a desired metabolite.

The method operates through a multi-step computational protocol [7]:

- Simulation with Production Objective: An ecModel is simulated under conditions that enforce a high production rate of the target metabolite.

- Flux Profile Analysis: The resulting flux distribution is analyzed to identify reactions whose fluxes increase alongside the enforced production.

- Enzyme Usage Analysis: The model calculates the required levels of enzymes to support the new flux distribution.

- Target Prioritization: Genes encoding enzymes that are predicted to be heavily utilized or flux-limiting are flagged as potential overexpression targets. Conversely, genes associated with competing pathways may be suggested for deletion.

This pipeline has been successfully applied to predict gene targets for increased production of compounds like 2-phenylethanol and heme in S. cerevisiae [7].

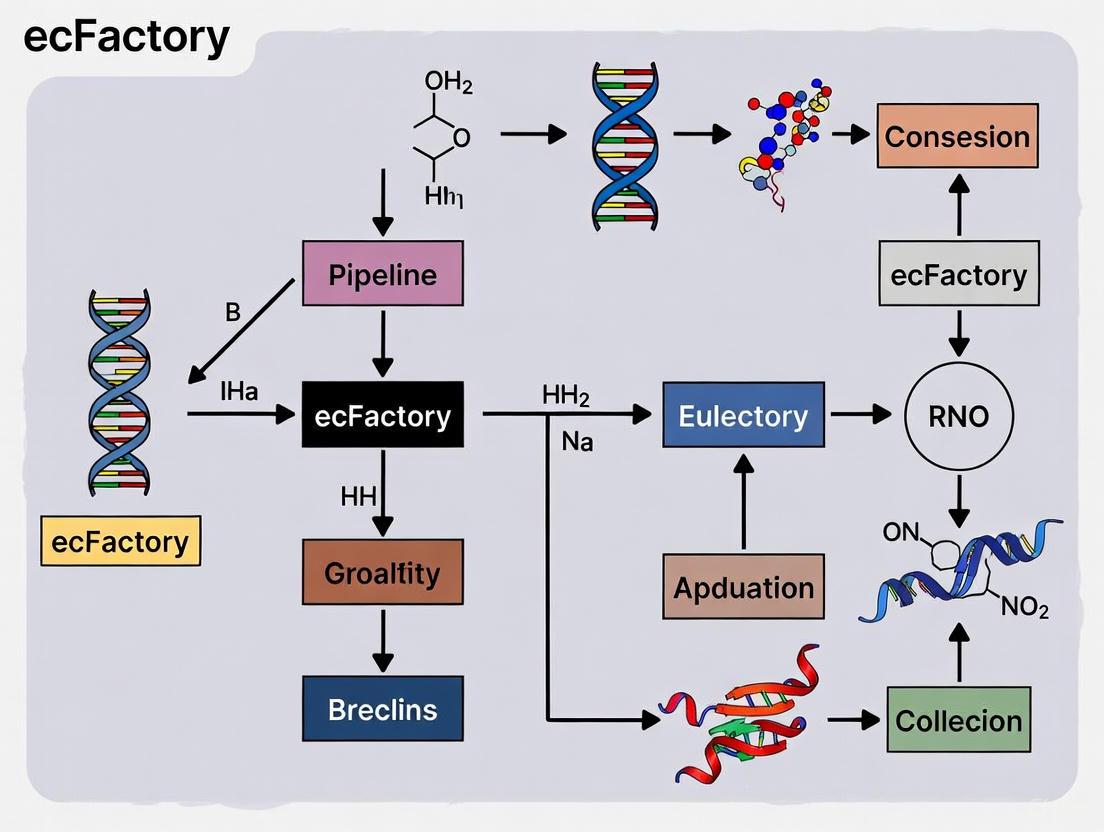

Figure 1: The ecFactory workflow for predicting gene targets. The pipeline starts with a metabolic model, enhances it with enzymatic constraints, and uses a scanning algorithm to identify genes that influence the production of a target metabolite.

Application Note: A Multi-Scale Case Study in Aging Research

Constraint-based modeling is particularly powerful for investigating complex, multi-scale biological systems. A notable application is the study of host-microbiome metabolic interactions during aging [3].

Experimental Background and Objective

Aging is associated with significant changes in the gut microbiome, but the molecular mechanisms and their impact on host health remain unclear. Researchers aimed to characterize the metabolic interplay between the host and its gut microbiome throughout the aging process and identify specific pathways that could influence aging phenotypes [3].

Integrated Experimental and Modeling Protocol

Step 1: Multi-omics Data Generation

- Input: Colon, liver, and brain tissues from mice across a lifespan (2 to 30 months).

- Methods:

- Metagenomics: Shotgun and long-read sequencing of fecal samples to profile the gut microbiome. This resulted in 181 Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs).

- Transcriptomics: RNA sequencing of host tissues.

- Metabolomics: Profiling of metabolic compounds.

- Output: Taxonomic and functional profiles of the microbiome; host gene expression data; metabolite measurements [3].

Step 2: Metabolic Network Reconstruction

- For each of the 181 bacterial MAGs, a genome-scale metabolic model was reconstructed using the

gapseqtool. - A separate metabolic model was used for the host (Recon 2.2), with instances for the colon, liver, and brain.

- These models were integrated into a single metaorganism metabolic model, connecting the host tissues via the bloodstream and linking them to the microbiome model via the gut lumen [3].

Step 3: Model Simulation and Analysis

- The integrated model was used to simulate metabolic states under different conditions.

- Correlation Analysis: Statistical associations were computed between microbial metabolic functions (reactions) and host transcript levels.

- Aging Trajectory Analysis: The models were contextualized with age-specific data to predict how metabolic interaction patterns shift with age [3].

Step 4: Validation

- Predictions of microbiome-dependent host functions were compared against transcriptomic data from germ-free (GF) mice and conventionalized (CONVD) mice to identify genes responsive to microbial colonization [3].

Key Findings and Output

The modeling effort revealed a pronounced age-related decline in metabolic activity within the gut microbiome. It predicted a specific reduction in beneficial metabolic interactions, including a downregulation of essential host pathways in nucleotide metabolism that rely on microbial support. These pathways are critical for maintaining intestinal barrier function and cellular homeostasis, providing a mechanistic link between microbiome changes and age-related host physiology decline [3].

Table 2: Key Metabolic Changes Predicted by the Aging Host-Microbiome Model

| Aspect Analyzed | Finding in Aged Mice | Predicted Impact on Host |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Microbiome Activity | Pronounced reduction | Lower contribution to host energy and metabolite pools. |

| Inter-bacterial Interactions | Reduced beneficial metabolite exchange | Less stable and less resilient microbial community. |

| Host Nucleotide Metabolism | Significantly downregulated | Compromised intestinal barrier function, impaired cellular replication. |

| Systemic State | Increased inflammation (Inflammaging) | Driven by microbial products crossing a weakened gut barrier. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key software, databases, and computational tools essential for conducting research in constraint-based metabolic modeling and applying the ecFactory pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Constraint-Based Modeling

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Brief Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| COBRApy [2] [8] | Software Package | A Python toolbox for simulating constraint-based metabolic models. Essential for implementing FBA and related algorithms. |

| GECKO Toolbox [5] | Software Pipeline | A MATLAB-based toolbox for enhancing GEMs with enzymatic constraints to generate ecModels. Core to the ecFactory method. |

| ecModels Container [6] [9] | Model Repository | A curated collection of pre-built enzyme-constrained models for various organisms, hosted on GitHub. |

| BRENDA Database [5] | Kinetic Database | The main repository for enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat), which are used by GECKO to parameterize ecModels. |

| AGORA2 [4] | Model Resource | A collection of curated, genome-scale metabolic models for 7,302 human gut microbes, enabling community and host-microbiome modeling. |

| gapseq [3] | Software Tool | A tool for the reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic networks from genomic data. Used for drafting models from MAGs. |

| MetaCyc [3] [1] | Pathway Database | A database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes, used for pathway annotation and gap-filling in reconstructions. |

Protocol: Implementing a Basic ecFactory Analysis

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for running the ecFactory method to identify gene targets for metabolic engineering, using a yeast model as an example.

Objective: To identify gene overexpression and knockout targets in S. cerevisiae for enhanced production of 2-phenylethanol.

Required Software and Data:

- MATLAB (version 7.3 or higher).

- The GECKO and ecFactory toolboxes (cloned from their respective GitHub repositories).

- An enzyme-constrained model of S. cerevisiae (e.g., ecYeastGEM) [7].

- The COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB.

Procedure:

Model Preparation

- Load the ecYeastGEM model into the MATLAB workspace.

- Ensure the model is functional by running a test simulation to verify growth under standard conditions.

- Define the target metabolite (e.g., 2-phenylethanol exchange reaction) and the biomass reaction as the primary objective.

Run the ecFactory Algorithm

- Execute the main

ecFactoryfunction, providing the following inputs:- The loaded ecModel.

- The identifier for the target product exchange reaction.

- The identifier for the biomass reaction.

- The algorithm will perform an FSEOF-style analysis on the enzyme-constrained model. It enforces a gradually increasing flux for the product reaction and scans for other reaction fluxes that correlate with this increase.

- Execute the main

Analysis of Output

- The method generates a list of candidate reactions whose fluxes increase with enforced product formation.

- For each candidate reaction, the corresponding gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rules are examined.

- Genes associated with these reactions are identified as potential overexpression targets.

- The model can also be used to simulate gene knockouts to identify competing pathways. Genes whose deletion increases the production yield are identified as potential knockout targets.

Output and Validation

- The final output is a ranked list of suggested genetic modifications.

- The results should be validated through experimental efforts, such as cultivating engineered yeast strains and measuring the titers of the target metabolite [7].

Figure 2: A simplified workflow for the ecFactory protocol, from model preparation to experimental validation of predicted gene targets.

The Role of Enzyme-Constrained Models (ecModels) in Enhancing Prediction Accuracy

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are computational representations of cellular metabolism that enable mathematical exploration of metabolic behaviors within environmental and stoichiometric constraints. While these models have seen wide usage in biotechnology and biomedicine, they often fail to correctly predict key phenotypes, particularly the suboptimal metabolism observed in microorganisms. A major limitation of traditional GEMs is that they assume a linear increase in growth and product yields as substrate uptake rates rise, which frequently diverges from experimental measurements. This discrepancy arises because GEMs consider only reaction stoichiometries while lacking other biological constraints that shape cellular behavior [10] [11].

The integration of enzymatic constraints into metabolic models addresses these limitations by incorporating fundamental biological principles of resource allocation and enzyme kinetics. Enzyme-constrained models (ecModels) enhance traditional GEMs by accounting for the limited amount of protein molecules within cells and the catalytic efficiency of enzymes. This approach has proven particularly valuable for explaining metabolic behaviors that defy optimality predictions, such as overflow metabolism in Escherichia coli and the Crabtree effect in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where microorganisms preferentially produce byproducts like acetate or ethanol even in the presence of oxygen [10] [12]. By embedding enzyme kinetic parameters and incorporating constraints on total cellular protein content, ecModels significantly narrow the solution space of feasible metabolic flux distributions, leading to more accurate phenotypic predictions [10] [13].

Theoretical Foundation and Key Methodological Approaches

Fundamental Principles of Enzyme Constraints

Enzyme-constrained models are founded on the principle that cellular metabolism is limited not only by stoichiometry but also by physicochemical constraints, with enzyme abundance and catalytic efficiency representing key determinants. The core mathematical formulation introduces an enzymatic constraint into the traditional flux balance analysis framework. This constraint, represented by Equation (1), limits the total enzyme usage by metabolic reactions based on enzyme kinetic parameters and the total protein budget available in the cell [10]:

Where vi represents the flux through reaction i, MWi is the molecular weight of the enzyme catalyzing the reaction, kcat,i is the enzyme's turnover number, σi is the enzyme saturation coefficient, ptot is the total protein fraction in the cell, and f is the mass fraction of enzymes in the total proteome [10].

This fundamental equation captures the trade-off between enzyme usage efficiency and metabolic output, providing a mechanistic basis for predicting cellular behaviors that emerge from resource allocation constraints. The incorporation of these enzyme constraints explains why microorganisms often exhibit suboptimal yields under high substrate uptake conditions, as producing and maintaining metabolic enzymes incurs significant resource costs that must be balanced against growth objectives [10] [13].

Several computational frameworks have been developed for constructing enzyme-constrained models, each with distinct approaches to incorporating enzymatic constraints:

Table 1: Major ecModel Construction Platforms and Their Key Features

| Method | Key Features | Representative Applications | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GECKO | Adds enzyme usage reactions to stoichiometric matrix; Incorporates proteomics data | ecYeast7, ecModels for various organisms [13] | MATLAB toolbox |

| ECMpy | Simplified workflow without modifying stoichiometric matrix; Automated parameter calibration | eciML1515 (E. coli), ecMTM (M. thermophila) [10] [14] | Python package |

| sMOMENT/AutoPACMEN | Reduced variable count; Direct constraint integration | Enhanced E. coli iJO1366 model [12] | Automated toolbox |

| ETFL | Integration of thermodynamic and enzyme constraints | E. coli model with dual constraints [15] | Python formulation |

The GECKO (Genome-scale model to account for Enzyme Constraints, using Kinetics and Omics) approach expands the original metabolic model by introducing pseudo-reactions and metabolites representing enzyme usage. This method allows direct incorporation of measured enzyme concentrations when available, setting upper limits for flux capacities through specific enzymatic reactions [16] [13].

In contrast, the ECMpy framework implements a simplified workflow that directly adds a total enzyme amount constraint to existing GEMs without modifying the stoichiometric matrix structure. This approach maintains compatibility with standard constraint-based modeling tools while incorporating enzyme constraints through additional linear equations [10] [11].

The sMOMENT (short MOMENT) method, implemented in the AutoPACMEN toolbox, represents a streamlined version of the earlier MOMENT approach. It achieves equivalent predictions with significantly fewer variables by directly integrating the relevant enzyme constraints into the standard representation of a constraint-based model [12].

Quantitative Assessment of Prediction Accuracy

The enhancement in prediction accuracy achieved by enzyme-constrained models is most evident in simulations of microbial growth on various carbon sources. Experimental validation studies demonstrate that ecModels provide substantially better agreement with measured growth rates compared to traditional GEMs.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Enzyme-Constrained vs. Traditional Models

| Model Type | Organism | Prediction Improvement | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| eciML1515 | Escherichia coli | Significant improvement on 24 single-carbon sources [10] | Estimation error reduced compared to iML1515 |

| ecYeast | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Accurate prediction of Crabtree effect [12] | Agreement with overflow metabolism data |

| ecMTM | Myceliophthora thermophila | Enhanced prediction of substrate hierarchy [14] | Accurate carbon source utilization patterns |

| sMOMENT-iJO1366 | Escherichia coli | Superior aerobic growth prediction without uptake limits [12] | 24 different carbon sources |

For example, the eciML1515 model for Escherichia coli demonstrated significantly improved growth rate predictions on 24 single-carbon sources when compared with the base iML1515 model. The enzyme-constrained model was able to recapitulate experimental growth rates without requiring artificial constraints on substrate uptake rates, a limitation common to traditional GEMs [10].

Similarly, the ecMTM model for Myceliophthora thermophila not only improved quantitative growth predictions but also accurately captured the hierarchical utilization of five carbon sources derived from plant biomass hydrolysis. This capability to predict substrate preference patterns based on enzyme efficiency considerations represents a significant advancement over traditional modeling approaches [14].

Explaining Metabolic Phenomena Through Enzyme Constraints

Enzyme-constrained models have successfully explained several metabolic phenomena that were previously puzzling from a stoichiometric perspective:

Overflow Metabolism: eciML1515 simulations revealed that redox balance, rather than purely kinetic constraints, was the key factor differentiating E. coli and S. cerevisiae overflow metabolism patterns [10].

Metabolic Trade-offs: Exploring metabolic behaviors under different substrate consumption rates revealed the tradeoff between enzyme usage efficiency and biomass yield, explaining why microorganisms often operate at suboptimal yields [10].

Enzyme Cost Analysis: ecModels enable calculation of reaction enzyme costs and energy synthesis enzyme costs, providing insights into the metabolic adjustment strategies employed by cells under different nutrient conditions [10] [14].

These capabilities demonstrate how ecModels move beyond descriptive modeling to provide mechanistic explanations for cellular metabolic strategies, making them valuable tools for both basic research and metabolic engineering applications.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Constructing ecModels Using GECKO 3.0

The GECKO (Genome-scale model to account for Enzyme Constraints, using Kinetics and Omics) toolbox provides a systematic approach for reconstructing enzyme-constrained models. The protocol consists of five main stages [13]:

Stage 1: ecModel Structure Expansion

- Start with a high-quality metabolic model in SBML format

- Expand the model structure to include enzyme usage reactions

- Add enzyme pseudometabolites and exchange reactions

- Define molecular weights for all enzymes in the model

Stage 2: Integration of Enzyme Turnover Numbers

- Collect kcat values from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases

- Incorporate deep learning-predicted enzyme kinetics for gaps

- Apply subcellular localization adjustments

- Handle isoenzymes and enzyme complexes appropriately

Stage 3: Model Tuning

- Identify reactions with high enzyme usage (>1% of total)

- Compare predicted fluxes with 13C experimental data

- Adjust kcat values to improve agreement with experimental data

- Calibrate total enzyme pool size

Stage 4: Integration of Proteomics Data

- Incorporate absolute proteomics measurements if available

- Set individual enzyme constraints based on measured concentrations

- Update total protein pool based on proteomics data

Stage 5: Simulation and Analysis

- Perform flux balance analysis with enzyme constraints

- Analyze flux variability and enzyme usage

- Predict metabolic engineering targets

The complete protocol takes approximately 5 hours for yeast models and can be adapted for other organisms [13].

Workflow for ECMpy-Based ecModel Construction

ECMpy provides a Python-based alternative for constructing enzyme-constrained models with a simplified workflow [10] [11]:

The ECMpy workflow begins with preprocessing of the base GEM, including splitting reversible reactions to account for potentially different kcat values in forward and backward directions. The tool then automates the collection of enzyme kinetic parameters from various databases, with the latest version ECMpy 2.0 employing machine learning to significantly enhance parameter coverage [11].

Key advantages of the ECMpy approach include:

- Direct integration with COBRApy toolbox for seamless analysis

- JSON-based storage of enzyme constraint information

- Automated calibration of enzyme kinetic parameters

- Compatibility with standard constraint-based modeling functions

The resulting enzyme-constrained model can be used to simulate various physiological conditions and identify enzyme limitations that constrain metabolic performance [10].

Successful construction and application of enzyme-constrained models requires several key resources and computational tools:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ecModel Construction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Databases | BRENDA [12], SABIO-RK [12] | Source of enzyme turnover numbers | Curated experimental kcat values |

| Machine Learning Predictors | DLKcat [14], TurNuP [14] | Prediction of missing kcat values | Expanded parameter coverage |

| Model Construction Toolboxes | GECKO [13], ECMpy [10], AutoPACMEN [12] | Automated ecModel reconstruction | Organism-specific template models |

| Simulation Environments | COBRApy [10], RAVEN Toolbox [17] | Flux balance analysis | Compatibility with SBML format |

| Omics Integration Tools | Proteomics data analysis pipelines | Parameterization with experimental data | Absolute protein quantification |

The integration of machine learning-predicted enzyme kinetics has particularly advanced the field by addressing the critical challenge of limited enzyme kinetic parameter coverage. Tools like DLKcat and TurNuP use deep learning approaches to predict kcat values for enzymes lacking experimental measurements, enabling construction of ecModels for less-characterized organisms [14].

For researchers working with non-model organisms, the RAVEN Toolbox and CarveFungi provide automated reconstruction of draft metabolic models from genomic and proteomic data, which can serve as starting points for ecModel development [17].

Applications in Metabolic Engineering and Cell Factory Design

Enzyme-constrained models have demonstrated significant value in metabolic engineering and the design of microbial cell factories for bioproduction. By explicitly accounting for enzyme allocation costs, ecModels enable identification of non-intuitive engineering targets that would be overlooked by traditional GEMs.

Predicting Metabolic Engineering Targets

Case studies across multiple organisms demonstrate the power of ecModels to predict effective metabolic engineering strategies:

In Escherichia coli, ecModel simulations have successfully predicted gene amplification targets for improving production of compounds like lysine, with experimental validation showing significant improvements in product titers [13].

For Saccharomyces cerevisiae, enzyme-constrained models have guided engineering strategies that resulted in a 70-fold improvement in intracellular heme production by identifying and addressing enzymatic bottlenecks [13].

The ecMTM model for Myceliophthora thermophila successfully predicted known targets for metabolic engineering and proposed new potential modifications for chemical production, demonstrating the value of enzyme cost considerations in strain design [14].

Integration with Artificial Intelligence

The emerging integration of ecModels with artificial intelligence approaches represents a powerful frontier in metabolic engineering:

Hybrid Modeling: Combining mechanistic ecModels with machine learning enables improved prediction of metabolic behaviors while maintaining biological interpretability [18].

Pathway Prediction: AI-powered tools like EZSpecificity enhance enzyme substrate specificity prediction, achieving 91.7% accuracy in identifying potential reactive substrates compared to 58.3% for previous state-of-the-art models [19].

Multi-omics Integration: Advanced ecModels can incorporate transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data to create context-specific models for different physiological conditions [17].

These developments support the creation of more realistic digital cell twins that can accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle in metabolic engineering, reducing the time and resources required to develop high-performance industrial strains.

Visualization of Enzyme-Constrained Model Construction Workflow

The process of constructing and utilizing enzyme-constrained models follows a systematic workflow that integrates various data sources and computational steps:

This workflow highlights the iterative nature of ecModel development, where initial predictions are refined through parameter calibration and validation against experimental data. The final output includes specific metabolic engineering targets that consider both stoichiometric and enzymatic limitations.

Enzyme-constrained metabolic models represent a significant advancement over traditional stoichiometric models by incorporating fundamental principles of enzyme kinetics and cellular resource allocation. The demonstrated improvements in predicting growth phenotypes, substrate utilization patterns, and metabolic engineering targets underscore the value of this modeling framework for both basic research and biotechnology applications.

Future developments in the field are likely to focus on several key areas:

- Enhanced integration of multi-omics data to create context-specific ecModels for different environmental conditions

- Improved machine learning approaches for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters across diverse organisms

- Development of multi-scale models that incorporate transcriptional regulation and metabolic signaling

- Expansion to multi-cellular systems and microbial communities for industrial and biomedical applications

As these tools become more accessible and accurate, they are poised to play an increasingly central role in rational metabolic engineering and the design of efficient microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction.

Integrating FSEOF (Flux Scanning with Enforced Objective Function) into the Pipeline

Flux Scanning based on Enforced Objective Flux (FSEOF) is a computational algorithm designed to systematically identify gene amplification targets in metabolic networks for enhanced production of desired bioproducts [20]. Unlike gene knockout strategies which are relatively straightforward to implement, identifying reliable gene amplification targets has been historically challenging because simply increasing gene expression does not necessarily result in increased metabolic fluxes due to complex regulatory constraints [20]. The FSEOF method addresses this gap by scanning all metabolic fluxes in a genome-scale metabolic model and selecting those fluxes that consistently increase when the flux toward product formation is artificially enforced as an additional constraint during flux analysis [20] [21].

Originally developed for metabolic engineering of microbial strains, FSEOF has proven particularly valuable for identifying targets for overproduction of various compounds including lycopene, shikimic acid, and putrescine in Escherichia coli [20] [21]. The method has since been adapted and extended for various applications, including co-production of multiple metabolites and integration with additional physiological constraints [22] [21]. Recent studies have demonstrated its utility in diverse organisms, including the first comprehensive metabolic model of Umbelopsis species for optimizing polyunsaturated fatty acid production [23].

Algorithmic Foundations and Recent Advancements

Core FSEOF Methodology

The fundamental principle behind FSEOF involves progressively enforcing the flux through the product reaction of interest and observing how other metabolic fluxes respond to this enforced change [20] [22]. The algorithm follows these key steps:

- Determine Maximum Flux Values: Calculate the maximum biomass formation rate (vmax,bio) and the maximum product formation rate (vmax,prdt) using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with respective objective functions.

- Enforce Product Flux: Systematically pin the product flux (v_prdt) to values ranging from its wild-type flux to x% of its theoretical maximum flux.

- Scan Flux Changes: At each enforced product flux level, compute metabolic fluxes and identify reactions whose fluxes increase proportionally with the enforced product flux.

- Select Amplification Targets: Reactions demonstrating consistent flux increases are selected as potential amplification targets for metabolic engineering [20] [22].

This approach successfully identified amplification targets for lycopene production in E. coli, including genes such as dxs, idi, fbaA, and tpiA [20]. When implemented experimentally, these targets led to significant synergistic enhancement of lycopene production, particularly when combined with gene knockout strategies [20].

Advanced FSEOF Variants

FVSEOF with Grouping Reaction (GR) Constraints

The original FSEOF method was enhanced through the incorporation of Grouping Reaction (GR) constraints to address the challenge of large flux solution spaces in metabolic models [21]. This advanced algorithm, termed FVSEOF with GR constraints, incorporates physiological data through:

- Genomic Context Analysis: Using the STRING database to identify functionally related reactions through conserved neighborhood, gene fusion, and co-occurrence analyses [21].

- Flux-Converging Pattern Analysis: Examining the number of carbon atoms in metabolites and flux-converging patterns from carbon sources to constrain flux scales [21].

- Simultaneous Constraints: Applying simultaneous on/off constraints (Con/off) and flux scale constraints (Cscale) to grouped reactions based on genomic context and flux-converging patterns [21].

This approach demonstrated improved performance in identifying reliable amplification targets for putrescine production in E. coli, with experimental validation confirming enhanced production yields [21].

co-FSEOF for Multi-Product Optimization

The co-FSEOF algorithm extends the original methodology to identify intervention strategies for co-optimizing production of multiple metabolites [22]. This framework enables:

- Identification of Co-Production Targets: Finding all pairs of products that can be co-optimized through single interventions.

- Higher-Order Intervention Strategies: Identifying amplification and knockout targets for given sets of metabolites.

- Organism-Specific Analysis: Application to genome-scale metabolic models of E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae under aerobic and anaerobic conditions [22].

This approach revealed that anaerobic conditions support co-production of a higher number of metabolites compared to aerobic conditions in both organisms [22].

ET-OptME: Integrating Enzyme and Thermodynamic Constraints

A recent protein-centered workflow layers enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic feasibility constraints onto genome-scale metabolic models [24]. This framework, ET-OptME, addresses limitations of classical stoichiometric algorithms like FSEOF by:

- Mitigating thermodynamic bottlenecks through stepwise constraint-layering.

- Optimizing enzyme usage costs for more physiologically realistic intervention strategies.

- Demonstrating significant improvement in prediction accuracy and precision compared to previous constraint-based methods [24].

Quantitative evaluation across five product targets in Corynebacterium glutamicum models showed at least 292% increase in minimal precision and 106% increase in accuracy compared to stoichiometric methods [24].

Table 1: Comparison of FSEOF Algorithm Variants

| Algorithm | Key Features | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSEOF [20] | Scans flux changes with enforced product flux | Lycopene production in E. coli | Simple implementation; Experimentally validated | Large flux solution space; No regulatory constraints |

| FVSEOF with GR [21] | Incorporates genomic context and flux-converging patterns | Shikimic acid and putrescine production in E. coli | Reduced solution space; More reliable predictions | Requires additional omics data |

| co-FSEOF [22] | Extends FSEOF for multiple products | Co-production analysis in E. coli and S. cerevisiae | Enables multi-product optimization; Identifies synergistic targets | Increased computational complexity |

| ET-OptME [24] | Adds enzyme and thermodynamic constraints | Multiple products in C. glutamicum | Improved physiological relevance; Higher accuracy | Complex implementation; Computational intensity |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard FSEOF Implementation Protocol

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., EcoMBEL979 for E. coli [21])

- Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis (COBRA) toolbox

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) capabilities

- Computational environment (MATLAB, Python, or R)

Procedure:

- Model Preparation: Load the genome-scale metabolic model and verify mass and charge balance of all reactions.

- Constraint Definition: Set appropriate physiological constraints including:

- Baseline Flux Calculation:

- Compute wild-type growth rate with biomass maximization as objective

- Calculate maximum product formation rate with product exchange reaction as objective

- Flux Enforcement and Scanning:

- For i = 1 to n (typically n=10-20 steps):

- Set product flux constraint: vprdt = vwt,prdt + (i/n)*(vmax,prdt - vwt,prdt)

- Maximize biomass subject to this constraint

- Record all metabolic fluxes at this enforced level

- For i = 1 to n (typically n=10-20 steps):

- Target Identification:

- Identify reactions with monotonically increasing fluxes across enforcement levels

- Filter targets based on slope threshold (typically > 0) [20]

- Rank targets by consistency and magnitude of flux increase

Validation:

- Compare predictions with known experimental results for validation compounds

- For novel targets, implement genetic modifications and measure product yields

- Use 13C metabolic flux analysis for experimental flux validation where possible [21]

FVSEOF with GR Constraints Protocol

Additional Requirements:

- Genomic context data (STRING database or equivalent)

- Carbon mapping information for flux-converging analysis

- Programming environment for implementing GR constraints

Procedure:

- Group Reaction Identification:

- Perform genomic context analysis to identify functionally related reactions

- Conduct flux-converging pattern analysis to determine CxJy indices

- Define reaction groups with identical CxJy indices and functional relationships [21]

- GR Constraint Implementation:

- Apply simultaneous on/off constraints (Con/off) to grouped reactions

- Implement flux scale constraints (Cscale) using the formula: [ \sqrt{(v1n - \frac{v1n + v2n}{2})^2 + (v2n - \frac{v1n + v2n}{2})^2} \leq \delta ] where vn represents normalized flux values [21]

- Constrained FVSEOF Execution:

- Perform flux variability scanning with enforced objective flux

- Apply GR constraints during FVA to reduce solution space

- Target Selection and Prioritization:

- Identify amplification targets from constrained flux variability results

- Prioritize targets based on functional importance and experimental feasibility

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Core FSEOF workflow for identifying gene amplification targets.

Integration with ecFactory Prediction Pipeline

Pipeline Architecture and Data Flow

The integration of FSEOF into the ecFactory computational pipeline enhances its capability for systematic identification of gene amplification targets alongside traditional knockout strategies. The integrated pipeline operates through the following stages:

Multi-Algorithm Target Identification:

- FSEOF and variants for amplification target identification

- FastKnock for comprehensive knockout strategy enumeration [25]

- MCSEnumerator for minimal cut set analysis

- OptForce for multi-target intervention strategies

Target Prioritization and Synergy Analysis:

- Rank targets by predicted impact on product yield

- Evaluate combinatorial effects of amplification and knockout strategies

- Assess implementation feasibility based on genetic manipulation complexity

Experimental Validation Cycle:

- Implement top-ranked targets in model organisms

- Measure product yields and growth characteristics

- Refine computational models based on experimental results

Diagram 2: FSEOF integration within the ecFactory prediction pipeline.

Case Study: Lipid Production in Oleaginous Fungi

A recent application demonstrating FSEOF integration in ecFactory involved lipid production optimization in Umbelopsis sp. WA50703, an oleaginous fungus [23]. The implementation:

- Utilized the first comprehensive metabolic model of Umbelopsis species (iUmbe1) containing 2,418 metabolites, 2,215 reactions, and 1,627 genes

- Applied FSEOF to identify 33 genes associated with 23 metabolic reactions relevant to lipid biosynthesis

- Revealed acetyl-CoA carboxylase and carbonic anhydrase as prime amplification candidates for enhancing polyunsaturated fatty acid production

- Achieved 81.05% predictive accuracy against experimental data, validating model reliability [23]

This case study highlights how FSEOF integration enables rapid identification of key metabolic bottlenecks and prioritization of engineering targets in non-model organisms with biotechnological potential.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FSEOF Implementation

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Models | EcoMBEL979, iJR904, iUmbe1 | Provide metabolic network representation for simulations | [20] [21] [23] |

| Software Toolboxes | COBRA Toolbox, RAVEN Toolbox | Implement FBA, FVA, and pathway analysis | [23] |

| Computational Environments | MATLAB, Python, R | Provide platform for algorithm implementation and execution | [25] [23] |

| Gene Expression Systems | pTrc99A vector system | Enable controlled gene overexpression in engineered strains | [20] |

| Flux Analysis Tools | 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis | Experimental validation of predicted flux distributions | [21] |

| Strain Engineering Tools | RED recombinase system, CRISPR-Cas9 | Enable precise genetic modifications in host organisms | [20] |

| Model Validation Databases | STRING database, MetaCyc | Provide genomic context and pathway information for constraint implementation | [21] |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Implementation Challenges

Limited Flux Response:

- Problem: Few reactions show consistent flux increases with enforced product flux

- Solution: Loosen physiological constraints; check for network gaps; verify product pathway completeness

Unrealistic Flux Predictions:

- Problem: Predicted amplification targets show minimal experimental impact

- Solution: Incorporate thermodynamic constraints (ET-OptME approach [24]); implement GR constraints to reduce solution space [21]

High Computational Demand:

- Problem: FSEOF execution time prohibitive for large models

- Solution: Implement reaction pruning [25]; use parallel computing; focus on subsystem analyses

Performance Optimization Strategies

Model Reduction:

- Remove blocked reactions prior to FSEOF analysis

- Focus on relevant metabolic subsystems connected to target product

- Implement FastKnock-inspired pruning algorithms to reduce search space [25]

Constraint Refinement:

Algorithmic Enhancements:

- Implement co-FSEOF for multi-product optimization [22]

- Combine with OptForce for comprehensive intervention strategies

- Integrate machine learning approaches for target prioritization

The integration of FSEOF into the ecFactory computational pipeline represents a significant advancement in systematic identification of gene amplification targets for metabolic engineering. The method's core strength lies in its ability to directly link enforced product formation with systematic scanning of metabolic flux changes, providing a rational approach to overcoming metabolic bottlenecks.

Recent advancements including GR constraints, multi-product optimization capabilities, and integration of enzyme thermodynamic constraints have substantially improved the predictive accuracy and practical utility of FSEOF-derived strategies [22] [24] [21]. The successful application to diverse biological systems from E. coli to oleaginous fungi demonstrates the generalizability of the approach [20] [23].

Future development directions should focus on enhanced integration of multi-omics data, improved prediction of regulatory constraints, and development of more efficient computational implementations to handle increasingly complex metabolic models. As the field progresses toward whole-cell model simulations, FSEOF and its variants will continue to play a crucial role in bridging computational predictions with experimental implementation in metabolic engineering pipelines.

Within the domain of modern metabolic engineering, the design of high-performance microbial cell factories is a cornerstone of industrial biotechnology. The core challenge lies in the precise identification of gene targets for genetic modulation—namely overexpression, knock-down, and knock-out—to redirect cellular metabolism toward the enhanced production of a desired compound. The ecFactory method addresses this challenge directly. It is a multi-step computational pipeline designed to systematically identify these metabolic engineering targets by integrating the principles of Flux Scanning with Enforced Objective Function (FSEOF) with the capabilities of enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models (ecModels) [7]. Defining the pipeline's objective is a critical first step, as it establishes a rational framework for in silico strain design, moving beyond random discovery and toward predictable, systematic engineering. This protocol outlines the definition of this objective within the ecFactory framework, detailing the necessary inputs, computational procedures, and validation steps required to generate a robust list of candidate gene targets.

Key Concepts and Definitions

The ecFactory Framework

The ecFactory method is a series of sequential steps for the identification of metabolic engineering gene targets. Its objective is to output specific gene targets indicating which genes should be overexpressed, knocked down, or knocked out to increase the production of a given target metabolite. This is achieved by combining the FSEOF algorithm with the enhanced predictive power of ecModels [7]. Unlike standard Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs), ecModels incorporate enzyme kinetics and abundance as additional constraints, narrowing the solution space and yielding more physiologically realistic predictions of metabolic flux [17].

Types of Genetic Interventions

- Overexpression: Increasing the expression level or activity of a gene product to amplify a desired metabolic flux.

- Knock-down: Partially reducing the expression or activity of a gene product to modulate a metabolic pathway without completely disrupting it.

- Knock-out: Completely eliminating the activity of a gene product to disrupt a competing or non-essential metabolic pathway.

Materials and Experimental Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for the ecFactory Pipeline

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | A computational reconstruction of an organism's metabolism, containing gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations. | Yeast8, Yeast9 [17] |

| Enzyme-constrained Model (ecModel) | A GEM enhanced with enzyme kinetic parameters and capacity constraints, providing more accurate flux predictions. | ecYeastGEM [7] |

| MATLAB | A high-level programming and numerical computing platform used to execute the ecFactory algorithm. | MATLAB 7.3 or higher [7] |

| ecFactory Scripts | The core computational scripts that implement the multi-step analysis, available via a public repository. | GitHub: SysBioChalmers/ecFactory [7] |

| Physiological Data | Experimentally determined parameters, such as substrate uptake rates and specific growth rates, to constrain the model. | |

| Omics Data (Optional) | Transcriptomic or proteomic data used to generate context-specific models for more personalized predictions. | [17] |

Protocol: Defining the Prediction Objective for Gene Targets

This protocol details the steps to define the objective for gene target prediction, which serves as the foundation for the ecFactory pipeline.

Input and Prerequisites

- Base Metabolic Model: Obtain a high-quality, curated GEM for your host organism (e.g., S. cerevisiae). The model must include GPR associations [17].

- Target Metabolite: Define the metabolite for which production is to be maximized. This is the enforced objective.

- Physiological Constraints: Gather data on the cultivation environment, including the carbon source and its uptake rate, and the organism's specific growth rate.

- Enzyme Kinetics Data: Collect data on enzyme turnover numbers ((k_{cat})) and, if available, measured enzyme abundances to generate the ecModel [17].

Procedure

Step 1: Develop the Enzyme-Constrained Model (ecModel)

- Action: Convert the base GEM into an ecModel by incorporating enzyme-related constraints. This involves defining the molecular weight of each enzyme and applying the associated (k_{cat}) values to their corresponding reactions.

- Rationale: This step introduces a proteomic limitation to the system, preventing the model from predicting unrealistically high fluxes that the cell's protein synthesis machinery cannot support [17].

- Output: An ecModel (e.g., ecYeastGEM) ready for simulation under enzyme capacity constraints.

Step 2: Apply the FSEOF Algorithm on the ecModel

- Action:

- Simulate the ecModel under baseline conditions to establish a reference state for growth and metabolite production.

- Systematically enforce a gradually increasing flux through the reaction(s) leading to the synthesis of the target metabolite.

- At each step of enforced production, scan the entire metabolic network and record the fluxes of all other reactions.

- Rationale: FSEOF identifies reactions whose flux changes concordantly with the enforced objective. Reactions whose fluxes increase are potential overexpression targets, while those that decrease or carry a negative flux are potential knock-down or knock-out targets [7].

- Output: A list of reactions and their associated genes, ranked by the correlation of their flux response to the enforced production objective.

Step 3: Classify and Prioritize Gene Targets

- Action: Interpret the FSEOF output to classify targets by intervention type.

- Overexpression Targets: Genes associated with reactions that show a significant, steady increase in flux as target production is enforced.

- Knock-down/Knock-out Targets: Genes associated with reactions that divert flux away from the target product (e.g., competing pathways) or that are non-essential under the production conditions.

- Rationale: This step translates raw flux data into a concrete genetic engineering strategy.

- Output: A final, prioritized list of gene targets for each type of genetic intervention.

Validation and Output

- Output: The primary output is a table of candidate gene targets, specifying the gene name, recommended intervention (overexpression, knock-down, knock-out), and a confidence metric (e.g., flux change magnitude).

- Validation: The predictions should be validated in vivo. A subset of the top-predicted targets (e.g., 3-5 genes) is selected for genetic modification in the host organism, followed by fermentation experiments to measure the resulting production titers, yields, and rates of the target metabolite [7].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points for defining the pipeline's objective within the ecFactory framework.

Diagram 1: Logical workflow for defining the gene target prediction objective in the ecFactory pipeline.

Application Notes and Case Studies

Case Study: Prediction of Gene Targets for 2-Phenylethanol Production inS. cerevisiae

A practical application of this protocol is demonstrated in a case study for increasing the production of 2-phenylethanol in S. cerevisiae.

- Objective: Defined as "predict gene targets for increased production of 2-phenylethanol."

- Implementation: The ecFactory method was executed using the ecYeastGEM model within MATLAB.

- Outcome: The pipeline successfully generated a list of gene targets for overexpression, knock-down, and knock-out. The detailed results of this case study, including the specific genes identified, are available in the ecFactory repository's tutorial, providing a template for applying the protocol to other target metabolites [7].

Integration with Advanced Modeling and AI

The core objective of the ecFactory pipeline can be further refined by integrating with advanced computational approaches. The field is moving toward the deep integration of mechanistic metabolic models with artificial intelligence (AI). Machine learning models can help refine the reconstruction of functional metabolic models and provide alternative data-driven solutions for strain design [18]. For instance, AI can be used to predict the outcomes of complex genetic interactions or to optimize the selection of targets from the candidate list generated by ecFactory, thereby enhancing the overall success rate of the engineering cycle.

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Table 2: Common Issues and Solutions in Defining the Pipeline Objective

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model fails to producethe target metabolite. | Gaps in the metabolic network; missing biochemical reactions. | Manually curate the model to add missing pathways or use tools like RAVEN or CarveFungi for automated draft reconstruction [17]. |

| FSEOF yields anunmanageably large list of targets. | The objective function or constraints are too permissive. | Apply stricter constraints on growth or substrate uptake. Prioritize targets based on the magnitude of their flux response. |

| Model predictions do notmatch experimental validation. | Inaccurate enzyme kinetic parameters ((k_{cat}) values). | Refine the ecModel with more organism-specific enzyme kinetic data from databases or literature. |

| Difficulty in classifyingknock-down vs. knock-out targets. | Ambiguous flux distributions in the model. | Analyze flux variability and essentiality. Genes whose knockout is predicted to be lethal should be considered for knock-down instead. |

The Critical Need for Computational Prediction in Streamlining Metabolic Engineering

Metabolic engineering aims to construct efficient microbial cell factories for the sustainable production of fuels, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals. However, the traditional design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycle remains time-consuming and costly, often relying on trial-and-error approaches. The integration of computational predictions has emerged as a critical strategy to streamline this process by rapidly identifying promising genetic modifications and prioritizing experimental efforts [24]. Computational pipelines, particularly those leveraging genome-scale metabolic models, have revolutionized our ability to predict gene targets for enhanced chemical production, dramatically accelerating the development of industrial biotechnology.

The ecFactory method represents a significant advancement in this field, providing a systematic framework for predicting metabolic engineering targets. This multi-step approach combines the principles of Flux Scanning with Enforced Objective Function (FSEOF) with enzyme-constrained metabolic models (ecModels) that incorporate proteomic limitations into metabolic networks [7]. By bridging the gap between genetic modifications and phenotypic outcomes, such computational approaches enable researchers to navigate the vast combinatorial space of possible engineering strategies with unprecedented efficiency.

Computational Framework and Methodology

The ecFactory Pipeline: Core Architecture

The ecFactory method operates through a sequential computational workflow designed to identify optimal gene manipulation targets—including overexpression, knockdown, and knockout candidates—for maximizing the production of target metabolites. Built upon constraint-based modeling principles, ecFactory integrates enzyme kinetics and thermodynamic constraints to generate biologically realistic predictions [7].

The foundational algorithm implements a series of constraints that mimic cellular resource allocation:

- Stoichiometric constraints: Govern mass-balance relationships in metabolic reactions

- Enzyme capacity constraints: Limit metabolic fluxes by enzyme abundance and catalytic capacity

- Thermodynamic constraints: Ensure the feasibility of metabolic pathways based on energy landscapes

This multi-layered constraint system enables more accurate prediction of metabolic behavior under genetic perturbations, significantly reducing false positives in target identification.

Advanced Algorithmic Extensions

Recent innovations have further enhanced the predictive capabilities of computational metabolic engineering. The ET-OptME framework systematically incorporates both enzyme efficiency and thermodynamic feasibility constraints into genome-scale metabolic models, addressing critical limitations of purely stoichiometric approaches [24]. This integrated method demonstrates substantial improvements in prediction accuracy, achieving at least a 70% increase in minimal precision and 47% increase in accuracy compared to enzyme-constrained algorithms alone [24].

Another innovative approach treats enzymes as microcompartments within metabolic network models, resolving conflicts between stoichiometric and other constraints by preventing unrealistic assumptions of free intermediate metabolites [26]. This compartmentalization strategy corrects pathway structures and reveals essential trade-offs between product yield and thermodynamic feasibility, providing more reliable engineering blueprints.

Figure 1: Computational Workflow Integrating Multiple Constraints. The pipeline begins with core metabolic models and progressively layers enzyme and thermodynamic constraints to identify high-confidence engineering targets.

Performance Metrics and Validation

Quantitative Assessment of Prediction Accuracy

Computational pipelines for metabolic engineering target prediction have demonstrated remarkable performance across diverse host organisms and target compounds. Quantitative evaluations reveal that advanced algorithms significantly outperform traditional stoichiometric methods in both precision and biological relevance.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Prediction Methods

| Method | Key Features | Prediction Accuracy Improvement | Validation Host | Chemical Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ecFactory | Integrates FSEOF with enzyme constraints | High-confidence targets for 103 chemicals | S. cerevisiae | 2-phenylethanol, heme [27] [7] |

| ET-OptME | Layers enzyme efficiency & thermodynamic constraints | 70-292% increase in precision vs. previous methods | C. glutamicum | 5 product targets [24] |

| Enzyme-as-Microcompartment | Resolves constraint conflicts via compartmentalization | Corrects pathway structures for thermodynamic feasibility | E. coli | l-serine, l-tryptophan [26] |

Large-Scale Target Identification

The ecFactory pipeline exemplifies the scale and efficiency of modern computational approaches, enabling simultaneous prediction of engineering targets for 103 different chemicals using Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a host organism [27]. This systematic mapping of metabolic engineering strategies across diverse chemical spaces demonstrates the powerful scalability of computational prediction platforms. Furthermore, the identification of gene target sets predicted for multiple chemical groups suggests the feasibility of rationally designing platform strains for diversified chemical production, potentially revolutionizing industrial bioprocess development [27].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of computational prediction pipelines requires specialized software tools and research reagents for experimental validation. The following resources represent core components of the metabolic engineering workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Purpose | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|

| MATLAB | Core computational environment for running ecFactory | Version 7.3 or higher required [7] |

| ecModel Database | Enzyme-constrained genome-scale metabolic models | ecYeastGEM for S. cerevisiae applications [7] |

| Cre-Lox System | Precise large-scale DNA manipulation | PCE/RePCE systems for kilobase to megabase edits [28] [29] |

| AiCErec | AI-guided recombinase engineering | Enhances recombination efficiency 3.5-fold [29] |

| Re-pegRNA | Scarless editing strategy | Removes residual recombination sites [29] |

Experimental Protocol: From Prediction to Validation

Gene Target Prediction Using ecFactory

Objective: Identify metabolic engineering targets for enhanced production of 2-phenylethanol in S. cerevisiae using the ecFactory computational pipeline.

Procedure:

- Software Setup: Install MATLAB (v7.3 or higher) and clone the ecFactory repository from GitHub into an accessible directory.

- Model Preparation: Load the ecYeastGEM model, an enzyme-constrained version of the yeast genome-scale metabolic model.

- Target Metabolite Specification: Define 2-phenylethanol as the target metabolite with appropriate exchange reaction identification.

- Constraint Application:

- Apply stoichiometric constraints to maintain mass balance

- Integrate enzyme capacity constraints based on catalytic rates

- Enforce thermodynamic constraints to eliminate infeasible flux directions

- FSEOF Implementation: Execute Flux Scanning with Enforced Objective Function to identify fluxes that increase with enforced production of 2-phenylethanol.

- Target Prioritization: Rank candidate genes based on flux response coefficients and enzyme usage costs.

- Output Generation: Save predicted gene targets for overexpression, knockdown, and knockout in the results directory [7].

Troubleshooting Tip: If the model fails to converge, verify that all enzyme constraints are properly defined and that the target metabolite can be produced by the network under baseline conditions.

Experimental Validation of Predicted Targets

Objective: Implement and validate genetic modifications predicted by ecFactory for enhanced 2-phenylethanol production.

Procedure:

- Strain Construction:

- For gene overexpression: Amplify target genes with strong promoters (e.g., TEF1, ADH1) using PCR and clone into yeast expression vectors.

- For gene knockouts: Design CRISPR-Cas9 guide RNAs targeting identified non-essential genes and transform into yeast with Cas9 expression cassette.

- Transformation: Introduce DNA constructs into S. cerevisiae using lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol (LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG) method.

- Fermentation: Inoculate engineered strains in selective medium and monitor growth and metabolite production under controlled bioreactor conditions.

- Product Quantification:

- Extract metabolites at mid-logarithmic growth phase

- Analyze 2-phenylethanol concentration using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

- Compare titers, yields, and productivities between engineered and control strains

- Data Integration: Compare experimental results with computational predictions to refine model parameters and identify additional optimization targets [27] [7].

Figure 2: DBTL Cycle with Computational Prediction. The integrated workflow begins with computational modeling, proceeds through genetic implementation and experimental validation, and concludes with model refinement based on experimental data.

The integration of computational prediction into metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift in biological design. Future advancements will likely focus on multi-omics integration, machine learning enhancement of model parameters, and automated strain construction technologies. The emerging ability to perform precise large-scale chromosomal manipulations using technologies like Programmable Chromosome Engineering (PCE) systems will further accelerate the implementation of complex metabolic engineering strategies [28] [29].

Computational prediction has transformed metabolic engineering from an artisanal practice to a systematic discipline capable of tackling global challenges in sustainable manufacturing. As these tools continue to evolve in sophistication and accessibility, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly critical role in streamlining the development of microbial cell factories for bio-based production of valuable chemicals, fuels, and pharmaceuticals.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing the ecFactory Pipeline

In the context of the ecFactory computational pipeline for gene target prediction, robust management of MATLAB and ecModel dependencies is critical for ensuring research reproducibility, computational efficiency, and accurate simulation outcomes. Dependencies encompass all user-created files, data, and external toolboxes that influence simulation results, including MATLAB scripts, functions, data files, and specialized toolboxes like SimBiology. Proper dependency management prevents invalid simulation results when rebuilding model reference targets and is essential when distributing research pipelines across teams or computational environments. The ecFactory framework for predicting gene targets relies heavily on precise mathematical modeling of metabolic systems, where unmanaged dependencies can introduce significant errors in target identification and validation.

Core MATLAB Dependency Analysis Tools and Methods

Types of Model Dependencies

MATLAB and Simulink models recognize two primary categories of dependencies relevant to ecModel workflows. Known target dependencies are files and data external to model files that the software automatically identifies and examines for changes when checking if a model reference target is up to date. These include referenced models, linked libraries, enumerated type definitions, user-written S-functions with their TLC files, and external files used by Stateflow, MATLAB Function blocks, or MATLAB System blocks [30]. User-created dependencies represent files that the software cannot automatically identify, regardless of their potential impact on simulation results. This category includes MATLAB scripts and functions (.m) containing code executed by callbacks, custom data files, and configuration scripts that parameterize ecModels [30]. For the ecFactory pipeline, this distinction is crucial as gene expression data, constraint parameters, and kinetic rate functions typically fall into the user-created dependency category.

Dependency Identification Techniques

Several methodological approaches exist for identifying program dependencies in MATLAB ecosystems. The inmem function provides a simple display of all program files referenced by a particular function after execution. For a more detailed analysis, the matlab.codetools.requiredFilesAndProducts function identifies both dependent program files and required MathWorks products [31]. The most comprehensive approach utilizes the Dependency Analyzer, which graphically examines models, subsystems, and libraries referenced directly or indirectly by a model, producing dependency graphs that identify all required files and products [32]. For ecModel workflows, a combination of these methods is recommended to capture the full spectrum of computational dependencies from high-level toolboxes to low-level data files.

Table 1: MATLAB Dependency Analysis Tools Comparison

| Tool/Method | Key Capabilities | Output Format | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

inmem |

Lists program files in memory after execution | Text list | Quick dependency check during active development |

matlab.codetools.requiredFilesAndProducts |

Identifies program files and required MathWorks products | Cell arrays of files and products | Validating platform requirements before distribution |

| Dependency Analyzer | Comprehensive graphical analysis of file relationships | Interactive dependency graph | Complete pipeline documentation and project creation |

Experimental Protocols for Dependency Management

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Dependency Analysis for ecModels

This protocol describes a standardized methodology for identifying and documenting dependencies within ecModel architectures for gene target prediction.

Materials and Software Requirements

- MATLAB R2020b or newer with SimBiology toolbox

- Simulink installation for model reference hierarchies

- Dependency Analyzer tool access

- ecModel source files and associated data

Procedure

- Initial Setup: Clear all functions from memory using

clear functionscommand. Unlock any persistently locked functions usingmunlockto ensure complete dependency detection [31]. - Execute Model Workflow: Run the complete ecModel simulation with representative input parameters that exercise all code pathways. Different function arguments may reveal different dependencies.

- Dependency Analysis: Open the Dependency Analyzer from the MATLAB Apps tab under the MATLAB section. Click the "Open Folder" button and select the primary ecModel directory [31].

- Graph Configuration: Select appropriate view options based on analysis needs. The "Model Hierarchy" view shows each referenced file once, while "Model Instances" shows every reference to a model in the hierarchy [32].

- Product Identification: Clear all selections in the dependency graph to view required MathWorks products and add-ons for the entire design in the Properties pane [32].

- Export Results: Export dependency analysis results using "Export to Workspace" for programmatic access, "Generate Dependency Report" for documentation, or "Create Project" to package the complete design [32].

Troubleshooting Notes

- If dependencies appear incomplete, execute

Analyze > Reanalyze Allin the Dependency Analyzer for a complete analysis. - Protected models (.slxp files) will appear as dark red boxes but cannot be inspected internally [32].

- Dependencies introduced through conditional code paths might require multiple executions with different parameters for complete detection.

Protocol 2: Specifying Model Dependencies for Reproducible Builds

This protocol ensures accurate rebuild detection when ecModel configuration parameters are set to rebuild based on dependency changes.

Configuration Steps

- Access the Configuration Parameters dialog for the referenced model by selecting the Model Settings arrow from the Modeling tab, then choosing "Model Settings" in the Referenced Model section [30].

- Enable the "Model dependencies" parameter by setting "Total number of instances allowed per top model" to "One" or "Multiple" [30].

- Specify dependencies as a character vector or cell array of character vectors, including file names, paths to dependent files, or folders. Use the

$MDLtoken to indicate paths relative to the model file location [30]. - Apply the configuration and verify by simulating the model after modifying dependent files to ensure proper rebuild detection.

Example Implementation

Table 2: ecModel Dependency Specification Patterns

| Dependency Type | Specification Format | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local data file | $MDL\filename.ext |

$MDL\kineticConstants.mat |

Path relative to model file |

| Absolute path file | Full path string | 'C:\Data\transcriptomics.csv' |

Platform-specific, reduces portability |

| Wildcard inclusion | *.ext |

'..\utils\*.m' |

Includes all matching files in folder |

| Folder dependency | Folder path | 'D:\Project\helperFunctions\' |

All files in folder are treated as dependencies |

Visualization of ecModel Dependency Workflows

ecModel Dependency Analysis Workflow

ecModel Dependency Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ecModel Development

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example | Dependency Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| SimBiology Toolbox | Modeling and simulation of biological systems | Creating ODE-based metabolic models for gene target validation | MathWorks Product |

| Dependency Analyzer | Visualization and analysis of file dependencies | Identifying all required files for ecModel simulation | MATLAB Built-in Tool |

| txtlsim Toolbox | Prototyping genetic circuits in TX-TL systems | Modeling transcription-translation mechanisms in metabolic networks [33] | Third-party Toolbox |

| Parameter Estimation Functions (lsqcurvefit) | Fitting model parameters to experimental data | Estimating kinetic constants from metabolic time-series data [34] | MATLAB Optimization Toolbox |

| Gene Expression Data Files | Input data for constraint-based modeling | Providing transcriptomic constraints for ecModel simulations | User-created Data |

| Model Configuration Scripts | Automated model setup and parameterization | Standardized initialization of ecModel simulation conditions | User-created Dependency |

| Metabolic Database Files | Repository of known metabolic reactions and compounds | Validating predicted metabolic pathways in target identification | External Database |

Within the broader thesis on computational pipeline ecFactory prediction gene targets research, this document serves as a detailed application note and protocol. The ecFactory method is a multi-step, sequential computational pipeline designed for the identification of metabolic engineering gene targets. These targets indicate which genes should be overexpressed, knocked down, or knocked out to increase the production of a desired metabolite [7]. This protocol details the entire workflow, from curating the initial model to generating a finalized list of high-priority gene targets, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a reproducible framework for target discovery.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Curation and Preparation

The ecFactory method is built upon the principles of the FSEOF (Flux Scanning with Enforced Objective Function) algorithm but incorporates them into the framework of GECKO (Enzyme-Constrained) genome-scale metabolic models (ecModels). ecModels extend traditional stoichiometric models by explicitly incorporating enzyme kinetics and capacity constraints, leading to more realistic predictions of metabolic fluxes [7].

Required Software and Reagents:

- Software: A functional MATLAB installation (version 7.3 or higher) is required. The ecFactory repository must be cloned from its GitHub source to a local directory [7].

- Model: A genome-scale metabolic model for the organism of interest (e.g., S. cerevisiae). The corresponding ecModel (e.g., ecYeastGEM) is required to implement enzyme constraints.

Procedure:

- Model Selection: Obtain a high-quality, community-vetted genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) for your target organism.

- Integration of Enzyme Constraints: Convert the standard GEM into an enzyme-constrained model (ecModel) using the GECKO methodology. This involves:

- Adding enzyme metabolites and reactions to the model.

- Defining enzyme usage constraints based on measured enzyme turnover numbers (( k_{cat} )) and protein abundance data.

- Model Validation: Simulate baseline growth and metabolite production under defined conditions to ensure the ecModel accurately recapitulates known physiology.

Target Identification via the ecFactory Pipeline

The core of the workflow involves executing the ecFactory script, which operates through a series of sequential steps [7].

Procedure:

- Define the Objective: Specify the target metabolite for overproduction in the ecFactory script.