Eliminating Thermodynamically Infeasible Loops: A Guide to Accurate Metabolic Flux Prediction for Biomedical Research

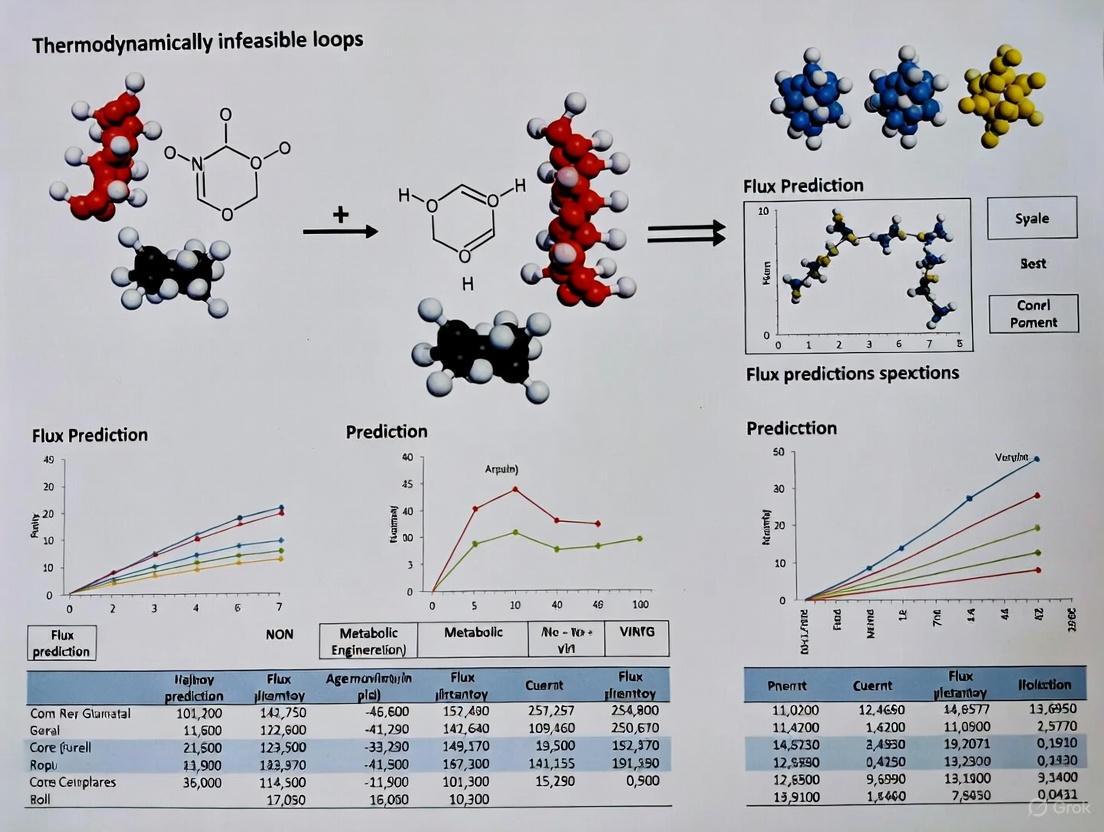

Thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) in metabolic models create significant challenges, limiting the predictive accuracy of flux distributions essential for understanding cellular behavior and optimizing bioprocesses like pharmaceutical production.

Eliminating Thermodynamically Infeasible Loops: A Guide to Accurate Metabolic Flux Prediction for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) in metabolic models create significant challenges, limiting the predictive accuracy of flux distributions essential for understanding cellular behavior and optimizing bioprocesses like pharmaceutical production. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the origins, detection, and resolution of TICs. It explores foundational concepts of thermodynamic constraints on metabolic fluxes, reviews advanced computational tools like ThermOptCOBRA and FLUXestimator for model refinement, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By integrating validation frameworks and comparative analyses, the content aims to equip scientists with the methodologies needed to construct thermodynamically consistent models, thereby enhancing the reliability of flux predictions in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles: The Hidden Challenge in Metabolic Models

Defining Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles (TICs) and Their Impact on Predictive Biology

Fundamental Concepts: TICs Explained

What is a Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycle (TIC)? A Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycle (TIC), also known as a loop, is a set of metabolic reactions within a network that can carry a net flux without any net input or output of nutrients [1]. Analogous to a perpetual motion machine, these cycles violate the second law of thermodynamics by cycling metabolites indefinitely without any real change, leading to the prediction of thermodynamically impossible phenotypes [1].

What is the core thermodynamic principle that TICs violate? TICs violate the second law of thermodynamics. Thermodynamic feasibility requires that reactions proceed in a direction that releases energy, characterized by a negative Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) [1]. In a TIC, this energy gradient is absent.

Why are TICs a critical problem in predictive biology? The presence of TICs significantly undermines the predictive capabilities of metabolic models by causing several critical issues [1]:

- Distorted Flux Distributions: Flux predictions, such as those from Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), may show unrealistically high fluxes through reactions involved in TICs.

- Erroneous Growth and Energy Predictions: Models can predict energy production or cellular growth that is not biologically possible.

- Unreliable Gene Essentiality Predictions: The identification of essential genes can be incorrect due to the presence of alternative, infeasible metabolic routes.

- Compromised Multi-omics Integration: Integrating transcriptomic or other omics data with flawed models leads to unreliable, context-specific predictions.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Problem 1: Identifying TICs in a Metabolic Network

Q: How can I efficiently detect Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles in my genome-scale metabolic model (GEM)?

A: You can use specialized algorithms designed for TIC enumeration. Traditional methods like loopless-FVA can be computationally expensive. A modern solution is ThermOptEnumerator, part of the ThermOptCOBRA toolbox, which leverages network topology to identify TICs efficiently without requiring external experimental data like Gibbs free energy [1].

- Protocol: TIC Detection with ThermOptEnumerator

- Input Preparation: Prepare your model in a standard format (e.g., SBML) compatible with the COBRA Toolbox. The primary input is the model's stoichiometric matrix (S), along with reaction directionality and flux bounds [1].

- Algorithm Execution: Run the ThermOptEnumerator algorithm. It operates on the stoichiometric matrix to identify sets of cyclic reactions [1].

- Output Analysis: The output is a list of all reaction sets that form TICs within your model. This list is a valuable resource for subsequent model curation and refinement [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of TIC Detection Methods

| Method | Key Approach | Required Inputs | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| ThermOptEnumerator | Topological analysis of network [1] | Stoichiometric matrix, reaction directionality [1] | 121x faster on average than OptFill-mTFP [1] |

| OptFill-mTFP | Exhaustive MILP optimization [1] | Stoichiometric matrix, reaction directionality [1] | High computational complexity [1] |

| Loopless-FVA | Variability analysis with thermodynamic constraints [1] | Stoichiometric matrix, reaction directionality [1] | Slower for blocked reaction identification in 89% of tested models [1] |

Problem 2: Resolving TICs to Refine Metabolic Models

Q: After identifying TICs, what are the strategies to remove them and create a thermodynamically consistent model?

A: The main strategies involve constraining reaction directionality and removing problematic reactions. A key step is identifying reactions that are blocked due to thermodynamic infeasibility.

- Protocol: Finding Blocked Reactions with ThermOptCC

- Run Consistency Check: Use the ThermOptCC algorithm to identify reactions that cannot carry any flux due to either dead-end metabolites or thermodynamic infeasibility [1].

- Analyze Results: ThermOptCC provides a list of stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions. These are prime candidates for removal or revision [1].

- Curate the Model: Remove the identified blocked reactions or correct their directionality constraints (e.g., change from reversible to irreversible based on thermodynamic data) to break the TICs [1].

Table 2: Classification and Solutions for Common TIC-Related Issues

| Problem Type | Description | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometrically Blocked Reaction | A reaction is part of a dead-end in the network, unable to carry flux due to missing connecting reactions [1]. | Use gap-filling algorithms to add missing reactions or remove the blocked reaction [1]. |

| Thermodynamically Blocked Reaction | A reaction is part of a TIC and can only carry flux if the infeasible cycle is active [1]. | Apply thermodynamic constraints to enforce feasible flux directions or remove the reaction [1]. |

| Loop-Contaminated Flux Sample | Flux distributions from sampling methods contain loops, reducing biological accuracy [1]. | Use loopless flux sampling methods (e.g., ll-ACHRB) or post-process samples with tools like ThermOptFlux to project them to the nearest loop-free distribution [1]. |

Problem 3: Building Context-Specific Models Free from TICs

Q: I am building a context-specific model (CSM) using transcriptomic data. How can I ensure the resulting model is thermodynamically consistent?

A: Standard CSM algorithms often neglect thermodynamic feasibility. To address this, use the ThermOptiCS algorithm, which integrates TIC removal constraints directly into the model construction process [1].

- Protocol: Thermodynamically Consistent CSM with ThermOptiCS

- Input Core Set: Define your set of core reactions with high transcriptomic evidence, as you would with algorithms like Fastcore [1].

- Incorporate Thermodynamics: Run the ThermOptiCS algorithm. Unlike traditional methods, it adds the minimal set of reactions required to allow flux through the core set while simultaneously ensuring no thermodynamically blocked reactions are included [1].

- Validate Output: The resulting CSM will be compact and thermodynamically consistent, free from reactions that require TICs to be active [1].

Problem 4: Ensuring Loopless Flux Sampling

Q: My flux sampling results contain thermodynamically infeasible loops. How can I generate loopless flux samples?

A: Standard sampling algorithms can produce samples with loops. To ensure thermodynamic feasibility, use samplers that incorporate loopless constraints or post-process your samples.

- Protocol: Loopless Flux Sampling and Analysis

- Use a Loopless Sampler: Employ specialized samplers like ll-ACHRB or ADSB that are designed to generate samples within a loopless solution space [1].

- Post-Process Existing Samples: If you already have flux distributions, use the ThermOptFlux method. It uses a TICmatrix derived from ThermOptEnumerator to efficiently detect and remove loops from any flux distribution, projecting it to the nearest thermodynamically feasible point [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for TIC Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application in TIC Research |

|---|---|---|

| ThermOptCOBRA Toolbox [1] | A suite of algorithms for thermodynamically optimal model construction and analysis. | Integrates multiple tools (ThermOptEnumerator, ThermOptCC, ThermOptiCS, ThermOptFlux) for an end-to-end solution to the TIC problem [1]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB-based environment for constraint-based modeling. | Provides the foundational framework for running FBA, FVA, and for integrating tools like ThermOptCOBRA [1]. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | A mathematical representation of the metabolic network. | The core input for all TIC detection and resolution algorithms, defining the structure of the network [1]. |

| TICmatrix | A matrix derived from enumerated TICs. | Used by ThermOptFlux for efficient loop checking and removal from flux distributions [1]. |

| Context-Specific Expression Data | Transcriptomic data (e.g., from scRNA-seq). | Used as input for building condition-specific models with tools like ThermOptiCS and FLUXestimator [1] [2]. |

| FLUXestimator / scFEA [2] | A web server and computational method for predicting metabolic flux from transcriptomic data. | Enables the estimation of cell-wise fluxomes, which can be analyzed and corrected for TICs using the above tools [2]. |

The Critical Role of Thermodynamic Laws in Constraining Metabolic Fluxes and Enzyme Activity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my flux balance analysis (FBA) predictions include thermodynamically infeasible loops, and how can I eliminate them? Thermodynamically infeasible loops, such as cyclic flux through a reaction loop like A→B→C→A, are mathematically possible in standard FBA but violate the first law of thermodynamics, as the overall thermodynamic driving force must be zero, allowing no net flux. The solution is to apply Thermodynamics-based Metabolic Flux Analysis (TMFA), which incorporates linear thermodynamic constraints alongside mass balance constraints to ensure all predicted flux distributions are thermodynamically feasible [3] [4].

FAQ 2: Which reactions in a metabolic network are most likely to be thermodynamic bottlenecks? Reactions with a Gibbs free energy change (ΔrG′) constrained close to zero are potential thermodynamic bottlenecks, as they operate near equilibrium. For example, in a genome-scale model of E. coli, the reaction dihydroorotase was identified as such a bottleneck. In contrast, reactions that are always highly negative in ΔrG′ are thermodynamically favored and may be candidates for metabolic regulation [3] [4].

FAQ 3: How do thermodynamic constraints affect the control of flux in a metabolic pathway? The regulation of metabolic fluxes by enzymes is shaped by the distribution of free energy across all reaction steps in a pathway. For pathways very far from equilibrium, flux control is typically dominated by upstream enzymes. However, the control pattern is adaptable and relies more on the overall free energy distribution than on the thermodynamic properties of any single enzyme [5] [6].

FAQ 4: Can I perform thermodynamic flux analysis without complete standard Gibbs energy data for all reactions? Yes. While thermodynamic data is essential, TMFA can be applied to analyze models lacking some thermodynamic data. For reactions where the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔrG′°) cannot be estimated, they can be handled through methods like lumping or by being assigned specific thermodynamic constraints within the TMFA framework [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue & Symptoms | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infeasible Flux Loops: FBA predicts energy-generating cycles without a net substrate. | Lack of thermodynamic constraints in the model [3]. | 1. Check for closed reaction loops (e.g., A→B→C→A).2. Analyze the ΔrG′ of reactions in the loop. | Implement Thermodynamics-based MFA (TMFA) to add linear thermodynamic constraints [3] [4]. |

| Thermodynamic Bottlenecks: A critical reaction operates near equilibrium (ΔrG′ ≈ 0), limiting pathway flux. | Metabolite concentrations forcing a reaction close to its equilibrium [3]. | 1. Calculate the feasible range of ΔrG′ for the reaction using TMFA.2. Identify reactions with ΔrG′ constrained near zero. | Engineer substrate or product levels to shift the reaction away from equilibrium; target concentration ratios (e.g., ATP/ADP) [3] [4]. |

| Inaccurate Flux Predictions: FBA predictions conflict with 13C-MFA measured fluxes [7] [8]. | Model assumes optimal growth; ignores thermodynamic and kinetic constraints [7]. | Perform 13C-MFA with labeled tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose) to measure in vivo fluxes [9] [8]. | Use 13C-MFA data for validation; constrain FBA/TMFA models with experimental flux data [7] [8]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing TMFA

Objective: To generate thermodynamically feasible flux and metabolite activity profiles for a genome-scale metabolic model.

Materials:

- A genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iJR904 for E. coli).

- Standard Gibbs free energy of formation (ΔfG′°) for metabolites.

- Software capable of linear programming (e.g., COBRA Toolbox).

Methodology:

Estimate Standard Gibbs Free Energy of Reactions (ΔrG′°):

Formulate the Thermodynamic Constraints:

- The core of TMFA is adding linear constraints to the classic mass-balance equation (S ∙ v = 0).

- The fundamental relationship linking flux, thermodynamics, and metabolite concentrations is:

ΔrG' = ΔrG'° + RT ∙ ln(Q)

Where

Qis the reaction quotient,Ris the gas constant, andTis the temperature. - To ensure thermodynamic feasibility, a reaction can only carry a positive flux if its ΔrG' is negative, and vice-versa. This is implemented as a linear constraint within the optimization problem [3] [4].

Solve the TMFA Problem:

- The problem is solved as a linear optimization. The objective function (e.g., maximize biomass growth) is optimized subject to both mass balance and thermodynamic constraints.

- The output includes:

Analyze Results:

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of Thermodynamics-based Metabolic Flux Analysis (TMFA) for addressing thermodynamically infeasible loops.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

| Category | Item | Function in Flux Analysis | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Tools | INCA [10] | Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis software for 13C-MFA. | Flux estimation in stationary and non-stationary isotope labeling experiments. |

| PIRAMID [10] | Quantifies metabolite mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) from MS data. | Automated data processing prior to flux analysis with INCA. | |

| VistaFlux [11] | Qualitative flux analysis software with pathway visualization for LC/MS data. | Interpreting and presenting results from stable isotope labeling experiments. | |

| COBRA Toolbox [7] | MATLAB suite for constraint-based modeling, including FBA. | Implementing TMFA and related algorithms in a genome-scale model. | |

| Isotopic Tracers | [1,2-13C] Glucose [9] [8] | A 13C-labeled carbon source for tracing carbon fate in metabolism. | Elucidating fluxes in central carbon metabolism (glycolysis, PPP) via 13C-MFA. |

| 13C-Glutamine [8] | A 13C-labeled tracer for analyzing nitrogen and carbon metabolism. | Studying flux in the TCA cycle and amino acid metabolism. | |

| Assay Kits | ATP/ADP/AMP Assay Kits [7] | Measure cellular energy charge and nucleotide ratios. | Constraining energy-generating/consuming reactions in TMFA. |

| NAD/NADH Assay Kits [7] | Quantify redox cofactor ratios. | Providing thermodynamic constraints for redox reactions in the network. |

How TICs Compromise Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM) Predictions in Drug Development

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are Thermally Infeasible Cycles (TICs) and why are they a problem in GEMs? Answer: Thermodyamically Infeasible Cycles (TICs), also known as infeasible loops or closed loops, are network cycles that can carry a non-zero steady-state flux without the consumption of any nutrients or the production of any by-products. They are analogous to electrical short circuits and violate the second law of thermodynamics because they effectively perform work without a source of free energy [12] [13]. In drug development, their presence compromises GEM predictions by leading to inflated and unrealistic estimates of biomass or target metabolite production, which can misdirect the identification and validation of potential drug targets [12] [14].

FAQ 2: How can I tell if my metabolic model contains TICs?

Answer: A common symptom is a flux solution where energy-generating reactions (like ATP hydrolysis) appear to be active without a corresponding energy source. Direct detection can be performed computationally. One method is to check for the existence of a vector of chemical potentials (G) for which the condition vT × G = 0 holds for your flux vector (v). If no such vector exists, the flux distribution contains a loop [12]. Advanced tools like ThermOptCOBRA can systematically identify TICs across large models [14].

FAQ 3: Do TICs only affect models used for Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)? Answer: No. While often discussed in the context of FBA, TICs can compromise any constraint-based method that computes steady-state flux solutions, including Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) and Monte Carlo sampling of the flux space [12] [13]. The elimination of TICs is therefore a critical step to ensure the thermodynamic feasibility of predictions from various computational techniques.

FAQ 4: What are the main strategies for correcting TICs in a model? Answer: There are two primary strategies:

- Looplaw Constraints (ll-COBRA): This method uses mixed integer programming to explicitly add thermodynamic constraints that prevent loops from appearing in flux solutions. It does not require prior knowledge of metabolite concentrations [12] [15].

- Post-processing Flux Solutions: This involves detecting loops in an existing flux solution (e.g., from FBA) and subsequently removing them by adjusting the flux values, often by minimizing the overall change to the original solution [13].

FAQ 5: Why is addressing TICs particularly important for drug development research? Answer: TICs can cause models to over-predict metabolic capabilities and misrepresent network flexibility. For example, a study on Klebsiella pneumoniae used context-specific models devoid of TICs to identify value catabolism as a critical pathway in clinical isolates—a finding that could point to a novel drug target [16]. Eliminating TICs leads to more accurate predictions of gene essentiality and pathway activity, ensuring that proposed therapeutic targets are grounded in physiologically realistic models [12] [14] [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Flux Balance Analysis predicts growth without a carbon source. Symptoms: Your model simulates biomass production (or ATP generation) even when all carbon uptake reactions are set to zero. Diagnosis: This is a classic sign of an active Thermodyamically Infeasible Cycle. The model is generating energy internally through a stoichiometrically balanced loop. Solutions:

- Run a loop detection algorithm. Apply a method like ll-COBRA or ThermOptCOBRA to your flux solution to confirm the presence of a TIC [12] [14].

- Impose looplaw constraints. Re-run your FBA simulation using loopless FBA (ll-FBA). This will constrain the solution space to only thermodynamically feasible fluxes [12].

- Check reaction directionality. Manually inspect and correct the reversibility of energy-related reactions (e.g., ATP synthase/hydrolysis) based on literature, as incorrect assignments often create these loops.

Problem: Gene essentiality predictions seem unrealistic or contradict experimental data. Symptoms: In silico gene knockout leads to no growth defect, whereas laboratory experiments show that the gene is essential. Diagnosis: TICs can provide alternative, thermodynamically impossible pathways that bypass the blocked reaction, making a gene appear non-essential in simulations. Solutions:

- Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) with loopless constraints. This will determine the feasible range of each reaction in the absence of loops. A reaction with a feasible flux range of zero is truly blocked [12].

- Use a loopless sampling method. Generate a set of thermodynamically feasible flux distributions to assess the true impact of a gene knockout on the network's capabilities [14].

- Validate with a refined model. Utilize tools like ThermOptCC to rapidly detect and remove stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions, creating a more accurate model for essentiality screening [14].

Problem: My Monte Carlo sampling of the flux space produces thermodynamically infeasible results. Symptoms: The sampled flux distributions include cycles of reactions that would violate energy conservation laws. Diagnosis: Standard sampling algorithms explore the entire stoichiometrically defined flux space, which includes thermodynamically infeasible regions containing TICs. Solutions:

- Implement loopless sampling. Use algorithms like ThermOptFlux, which enable the generation of loopless samples, ensuring every sampled flux distribution is thermodynamically feasible [14].

- Apply a post-processing correction. For an existing set of flux samples, you can apply a correction algorithm that identifies and removes the loops from each individual sample [13].

Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Loopless Flux Balance Analysis (ll-FBA)

This protocol converts a standard FBA problem into a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem to eliminate TICs [12].

Objective: Maximize a biological objective (e.g., biomass) while respecting mass balance and thermodynamic constraints. Constraints:

- Mass Balance: ( S \cdot v = 0 ) (Standard steady-state assumption)

- Flux Bounds: ( lbj \leq vj \leq ub_j ) (Reaction capacity constraints)

- Looplaw Constraints (MILP formulation):

- For each internal reaction

i, introduce a binary variable ( ai ) and a continuous variable ( Gi ). - The constraints are:

- ( -1000(1-ai) \leq vi \leq 1000ai )

- ( -1000ai + 1(1-ai) \leq Gi \leq -1ai + 1000(1-ai) )

- ( N{int} \cdot G = 0 )

- Where ( N{int} ) is the null space of the internal stoichiometric matrix.

- For each internal reaction

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing and solving the ll-FBA problem.

Protocol 2: A General Method for Detecting and Correcting Loops in Flux Distributions

This protocol is applicable for post-processing flux solutions from methods like FBA or sampling [13].

Objective: Determine if a given flux vector v contains TICs and remove them.

Procedure:

- Feasibility Check: For the flux vector

v'(excluding uptake and non-thermodynamic reactions), construct the matrix ( \Omega = { \Omega{mr} } ) with elements ( \Omega{mr} = -sign(v'r) S{mr} ). - Solve for Chemical Potentials: Check if a vector of chemical potentials ( \mu ) exists such that ( \mu \Omega > 0 ). This can be done efficiently using a relaxation algorithm.

- Loop Identification: If no solution exists, then by Gordan's theorem, a non-zero solution

kexists for ( \Omega k = 0 ) with ( k_r \geq 0 ). This vectorkrepresents a closed loop. - Loop Removal: Once a loop is found, it can be removed by adjusting the flux values. This can be done using:

- A local rule that exploits the fact that fluxes in a cycle are defined up to a constant.

- A global rule that minimizes an overall function of the fluxes (e.g., the total squared change from the original flux distribution) while imposing constraints that break the cycle.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and resources essential for research into TICs and GEMs.

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to TIC Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| ll-COBRA [12] [15] | Algorithm / Method | A mixed integer programming framework. | Eliminates TICs from FBA, FVA, and sampling; enforces the looplaw. |

| ThermOptCOBRA [14] | Software Suite | A comprehensive set of four algorithms. | Detects TICs, finds feasible flux directions, builds consistent models, and enables loopless sampling. |

| Monte Carlo Sampling [13] | Algorithm | Randomly samples the feasible flux space of a GEM. | Can be combined with loop-removal methods to generate thermodynamically feasible flux distributions. |

| BiGG Models Database [12] [17] | Knowledgebase | A repository of curated, genome-scale metabolic models. | Provides high-quality models using standardized nomenclature, which is a prerequisite for accurate TIC analysis. |

| Group Contribution Theory [12] | Estimation Method | Computes the standard free-energy change (ΔG°)- of reactions. | Used in thermodynamic methods to assign reaction directionality and identify infeasible loops. |

Advanced Detection and Correction Workflow

For a comprehensive approach to handling TICs, the following workflow integrates detection and correction steps using modern tools.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Thermodynamically Infeasible Loops in Steady-State Models

Problem: My constraint-based metabolic model produces flux distributions that violate the laws of thermodynamics. The predictions include net flux around closed cycles, which is physically impossible.

Explanation: Thermodynamically infeasible loops, also known as "type III pathways," are cyclic internal fluxes that do not perform a net transformation of metabolites yet carry a non-zero net flux. At steady state, the loop law—analogous to Kirchhoff's second law for electrical circuits—dictates that no net flux can occur around such cycles. Their presence indicates a violation of thermodynamic constraints [18].

Solution: Apply the loopless COBRA (ll-COBRA) method.

- Procedure: Utilize a mixed integer programming (MIP) approach that incorporates the loop law as an additional constraint into your model [18].

- Expected Outcome: This will eliminate all steady-state flux solutions that are thermodynamically infeasible, leading to more realistic predictions for methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), Flux Variability Analysis (FVA), and Monte Carlo sampling [18].

Guide 2: Ensuring Thermodynamic Feasibility in Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) Analysis

Problem: My Elementary Flux Mode analysis includes pathways that are not biologically relevant because they are thermodynamically infeasible.

Explanation: Traditional EFM analysis relies on a binary (reversible/irreversible) classification of reactions, which is an oversimplification. While useful, this approach can generate EFMs that are not consistent with quantitative thermodynamics, as every reaction is, in principle, reversible [19].

Solution: Compute thermodynamically feasible EFMs (tEFMs) using equilibrium constants.

- Procedure:

- Gather Data: Obtain the equilibrium constants ((K_{eq})) for the reactions in your network from databases like eQuilibrator [19].

- Apply Constraints: Use these constants to impose thermodynamic constraints during the EFM enumeration process, for instance, by integrating linear programming into computation tools [19].

- Note: This method typically does not require internal metabolite concentrations, though concentrations of external metabolites can further refine directionality [19].

- Expected Outcome: A significant reduction in the number of computed EFMs by ruling out those that are thermodynamically infeasible, thereby focusing the analysis on biologically relevant pathways [19].

Guide 3: Diagnosing Unexpected Flux Control Patterns

Problem: The flux control in my metabolic pathway model does not align with my biochemical intuition. For example, a downstream enzyme appears to exert strong control.

Explanation: The control of flux in a pathway is shaped by thermodynamic constraints. A reaction's ability to control flux is not determined solely by its own properties but by the distribution of free energy across all steps in the pathway. When a pathway operates very far from equilibrium, control is typically dominated by upstream enzymes. In other scenarios, the pattern is more adaptable [5].

Solution: Analyze the relationship between thermodynamics and flux control using Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA).

- Procedure:

- For a linear pathway, use the derived analytical expressions that relate Flux Control Coefficients (FCCs) to the free energy changes (( \Delta G )) of each reaction [5].

- Compute the FCCs using the formula that includes the rate constants and equilibrium constants of all reactions in the pathway [5].

- Expected Outcome: You will identify which enzymes truly control the flux under your model's specific thermodynamic conditions, revealing whether an unexpected pattern is, in fact, feasible [5].

Frequently Asked Questions

General Principles

Q1: Why can't my model have flux through a closed loop at a steady state? The loop law, a consequence of thermodynamics, states that at steady state, the net flux around any closed cycle must be zero. A non-zero flux would represent a perpetual motion machine, which is impossible because it would continuously generate energy without a source [18].

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between a stoichiometrically feasible flux and a thermodynamically feasible one? A stoichiometrically feasible flux only satisfies mass-balance constraints (what can happen based on the network structure). A thermodynamically feasible flux additionally satisfies energy-balance constraints, ensuring that every reaction in the distribution proceeds in a direction consistent with its Gibbs free energy change (( \Delta G )) [4]. All thermodynamically feasible fluxes are stoichiometrically feasible, but not vice versa.

Q3: How do thermodynamics affect the identification of a "rate-limiting step"? The concept of a single "rate-limiting step" is often an oversimplification. Metabolic Control Analysis shows that flux control ((C^J_v)) is distributed among multiple steps. The degree of control exerted by an enzyme is shaped by the thermodynamic driving force (( \Delta G )) of the entire pathway, not just its own catalytic efficiency. Generally, pathways far from equilibrium are controlled by upstream enzymes [5].

Methods and Implementation

Q4: My model is large. Is there a genome-scale method to enforce thermodynamic constraints? Yes, Thermodynamics-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis (TMFA) is designed for this purpose. TMFA adds linear thermodynamic constraints to the standard mass-balance constraints of MFA. This allows you to generate thermodynamically feasible flux profiles and also provides information on metabolite activity ranges and reaction ( \Delta G' ) on a genome-scale [4].

Q5: I don't have internal metabolite concentration data. Can I still apply thermodynamic constraints? Yes. Methods exist that use equilibrium constants ((K_{eq})) to compute thermodynamically feasible Elementary Flux Modes (tEFMs) without needing internal metabolite concentrations. However, including data on external metabolite concentrations will improve the accuracy of directionality assignments [19].

Q6: What software tools can I use to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible loops? The ll-COBRA (loopless COBRA) method is a widely recognized approach, implemented within the COBRA Toolbox framework, that uses mixed integer programming to eliminate these loops [18]. For EFM analysis, tools like efmTOOL can be integrated with linear programming to compute only the thermodynamically feasible EFMs during the enumeration process [19].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Implementing Loopless COBRA (ll-COBRA)

Objective: To acquire steady-state flux solutions that strictly obey the loop law.

Methodology:

- Model Formulation: Start with a standard constraint-based metabolic model defined by ( S \cdot v = 0 ) and ( \alphai \leq vi \leq \beta_i ), where (S) is the stoichiometric matrix and (v) is the flux vector [18].

- MIP Setup: Formulate a Mixed Integer Programming problem by introducing:

- Binary integer variables to represent the directionality of fluxes.

- Additional constraints that force the net flux around any cycle to be zero [18].

- Solution: Solve the MIP problem using a suitable solver. The resulting flux distribution, (v), will be free of thermodynamically infeasible loops [18].

Validation: Compare flux variability analysis (FVA) results before and after applying ll-COBRA. The loopless formulation should yield a smaller and more physiologically realistic flux range [18].

Protocol 2: Conducting Thermodynamics-Based Metabolic Flux Analysis (TMFA)

Objective: To perform flux analysis that generates thermodynamically feasible flux and metabolite activity profiles on a genome scale.

Methodology:

- Constraints: Apply two sets of linear constraints:

- Mass Balance: ( S \cdot v = 0 ).

- Energy Balance: ( \Deltar G' = \Deltar G'^{\circ} + RT \ln(Q) ), where (Q) is the reaction quotient. This is implemented as a linear constraint on metabolite chemical potentials [4].

- Data Integration: Incorporate standard Gibbs free energy of reactions (( \Delta_r G'^{\circ} )), which can be estimated from group contribution methods [4].

- Optimization: Solve the linear programming problem to find an optimal flux distribution (e.g., maximizing biomass yield) that satisfies all constraints [4].

Output: The solution provides:

- A thermodynamically feasible flux map.

- Ranges of possible metabolite activities (concentrations).

- The Gibbs free energy change (( \Delta_r G' )) for each reaction [4].

Comparative Table of Thermodynamic Feasibility Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Key Inputs | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ll-COBRA [18] | Mixed Integer Programming (MIP) | Stoichiometric model, reaction directionality | General steady-state flux methods (FBA, FVA) | Directly eliminates loops violating the loop law; improves prediction consistency. |

| tEFM Analysis [19] | Integration of equilibrium constants | Network stoichiometry, equilibrium constants ((K_{eq})) | Elementary Flux Mode (EFM) analysis | Reduces the number of EFMs by removing thermodynamically infeasible pathways without needing internal concentrations. |

| TMFA [4] | Linear thermodynamic constraints | Stoichiometric model, standard Gibbs energies (( \Delta_r G'^{\circ} )) | Genome-scale metabolic flux analysis | Provides feasible flux profiles, metabolite activities, and reaction energies on a large scale. |

| TKM Formalism [20] | Thermodynamic-Kinetic Modeling with potentials & forces | Reaction network, capacity parameters (compound-specific) | Building dynamic kinetic models | Structurally observes detailed balance, ensuring all model parameters are thermodynamically feasible. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Constraint-Based Model | A genome-scale stoichiometric model (e.g., for E. coli) that forms the base for all flux and thermodynamic simulations [4]. |

| Equilibrium Constants ((K_{eq})) | Quantitative thermodynamic parameters obtained from databases like eQuilibrator. Used to determine reaction directionality and compute tEFMs [19]. |

| Standard Gibbs Free Energy (( \Delta_r G'^{\circ} )) | The Gibbs free energy change under standard conditions. Estimated via group contribution methods and used as input for TMFA [4]. |

| Mixed Integer Programming (MIP) Solver | A computational tool (e.g., within the COBRA Toolbox) required to implement the ll-COBRA method and solve the resulting optimization problem [18]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Diagnosing Thermodynamic Feasibility in Flux Analysis

Diagram 2: Thermodynamic Constraints in a Linear Metabolic Pathway

Computational Tools and Techniques for Detecting and Correcting Infeasible Fluxes

Leveraging the ThermOptCOBRA Suite for Comprehensive TIC Identification and Resolution

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) and why are they problematic? Thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs), also known as "loop law" violations, are closed cycles of reactions in a metabolic network that can carry flux at steady state without a net consumption of nutrients or production of biomass [12]. Analogous to violating Kirchhoff's second law in electrical circuits [12], TICs are physically impossible as they would perform work without using free energy, contradicting the laws of thermodynamics [13]. Their presence in genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) limits the predictive ability of models and can severely bias inferences drawn from flux analysis methods like flux sampling [14] [21].

Q2: How does ThermOptCOBRA improve upon previous loopless methods? ThermOptCOBRA provides a comprehensive suite of four integrated algorithms for optimal model construction and analysis, whereas previous approaches like loopless COBRA (ll-COBRA) typically required formulating a mixed integer programming (MIP) problem to impose loop-law constraints [12]. ThermOptCOBRA efficiently identifies TICs in large-scale models, determines thermodynamically feasible flux directions, detects blocked reactions, constructs compact context-specific models, and enables loopless flux sampling [14]. This represents a significant advancement in handling TICs comprehensively compared to earlier methods.

Q3: What are the core components of the ThermOptCOBRA suite? The suite consists of four main algorithms [14]:

- ThermOptCC: Rapidly detects stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions.

- ThermOptiCS: Builds compact and thermodynamically consistent context-specific models.

- ThermOptFlux: Enables loopless flux sampling for accurate metabolic predictions.

- TIC Identification: Efficiently identifies thermodynamically infeasible cycles by leveraging network topology.

Q4: In what scenarios does ThermOptCOBRA particularly outperform alternatives? ThermOptCOBRA constructs thermodynamically consistent context-specific models that are more compact than those generated by Fastcore in 80% of cases [14]. It also enhances sampling algorithms by enabling loopless sample generation, which prevents artifacts introduced by thermodynamically infeasible cycles that can severely bias flux sampling results [14] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Prolonged Computation Time During TIC Identification

Problem: The TIC identification process is taking excessively long to complete, particularly for large genome-scale models.

Explanation: Identifying all loops in a directed network is computationally challenging. The problem belongs to the NP-hard class, meaning deterministic algorithms may struggle with large networks [13].

Solution:

- Step 1: Implement the topological analysis approach used by ThermOptCOBRA which leverages network topology for efficient TIC identification [14].

- Step 2: For extremely large models, consider the Monte Carlo method described in the literature which can identify loops stochastically with reduced computational burden [13].

- Step 3: Verify that you are using the latest version of ThermOptCOBRA, which has been optimized to identify TICs in 7,401 published models [14].

Verification: Successful identification should report the number and composition of TICs found without exceeding memory limits or timing out.

Issue 2: Thermodynamically Infeasible Flux Solutions Persist After Processing

Problem: After running ThermOptCOBRA, your flux solutions still contain thermodynamically infeasible cycles.

Explanation: This may occur if the implementation doesn't properly integrate the loop-law constraints or if there are issues with reaction directionality assignments.

Solution:

- Step 1: Ensure all exchange and transport reactions are properly defined with correct directionality.

- Step 2: Apply the loopless COBRA (ll-COBRA) constraints using mixed integer programming to eliminate all steady-state flux solutions incompatible with the loop law [12].

- Step 3: For flux sampling applications, use ThermOptFlux which specifically enables loopless sample generation [14].

- Step 4: Verify the nullspace condition: ensure that Nint × G = 0, where Nint is the null basis of the internal stoichiometric matrix and G is the vector of reaction energies [12].

Verification: Validate that the resulting flux distribution satisfies the loopless condition by checking if a solution exists for Nint × G = 0 with sign(G) = -sign(v) [12].

Issue 3: Incorrectly Blocked Reactions After Applying Thermodynamic Constraints

Problem: After applying thermodynamic constraints, metabolically important reactions are incorrectly identified as blocked.

Explanation: Overly stringent thermodynamic constraints can sometimes incorrectly block feasible reactions, particularly in complex network regions with multiple alternative pathways.

Solution:

- Step 1: Use ThermOptCC which is specifically designed to identify both stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions while preserving feasible pathways [14].

- Step 2: Compare the blocked reactions identified by ThermOptCOBRA with those from functional analysis.

- Step 3: For context-specific model building, use ThermOptiCS which constructs compact yet thermodynamically consistent models [14].

- Step 4: Check standard free energy change (ΔG°) values if available, as inaccurate estimates can lead to incorrect directionality assignments [12].

Verification: Essential metabolic functions should remain operational after applying constraints, and biomass production should not be compromised unless thermodynamically justified.

Performance Comparison Data

Table 1: Comparison of Thermodynamic Constraint Methods for Metabolic Models

| Method | Algorithm Type | Required Inputs | Key Advantages | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThermOptCOBRA | Comprehensive suite with multiple algorithms | Stoichiometric matrix, reaction bounds | Integrates TIC identification, directionality, and context-specific modeling; enables loopless sampling [14] | Optimized for genome-scale models |

| ll-COBRA | Mixed Integer Programming (MIP) | Stoichiometric matrix, flux bounds | Does not require thermodynamic data; ensures loopless solutions [12] | High (MIP problem) |

| Relaxation + Monte Carlo | Hybrid stochastic-deterministic | Stoichiometric matrix, flux distribution | Identifies and corrects infeasibilities in large networks; reveals model inconsistencies [13] | Moderate to High |

| MaxEnt | Maximum entropy principle | Experimentally measured fluxes | Less sensitive to TIC artifacts than sampling; less susceptible to overfitting than economy-based methods [21] | Moderate |

Table 2: ThermOptCOBRA Performance Metrics on Published Models

| Function | Performance Outcome | Comparison Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| TIC Identification | Efficiently identifies TICs in 7,401 published models [14] | Comprehensive coverage |

| Context-Specific Modeling | More compact models than Fastcore in 80% of cases [14] | 80% improvement |

| Blocked Reaction Detection | Identifies stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions [14] | More refined models with fewer TICs |

| Loopless Sampling | Enables loopless flux sample generation [14] | Improves predictive accuracy |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Loopless Constraints for FBA

This protocol adapts the ll-COBRA approach for eliminating thermodynamically infeasible loops in flux balance analysis [12].

Materials:

- Metabolic model (Stoichiometric matrix S, reaction bounds lb and ub)

- Linear programming solver with MIP capability

- COBRA toolbox or similar framework

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation:

- Begin with standard FBA: max cᵀv subject to S·v = 0, lb ≤ v ≤ ub [12]

- Identify internal reactions (excluding exchange and biomass reactions)

Add Loopless Constraints:

Solution:

- Solve the resulting MIP problem

- Extract the loopless flux distribution

Validation: Verify that vᵀG = 0 for all internal reactions and that no closed cycles exist in the solution [12].

Protocol 2: ThermOptCOBRA Workflow for Comprehensive TIC Resolution

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model in SBML format

- ThermOptCOBRA software suite

- Context-specific data (if building contextualized models)

Procedure:

- Initial TIC Identification:

- Run ThermOptCOBRA's TIC identification module leveraging network topology [14]

- Generate report of detected TICs

Reaction Directionality Analysis:

- Execute ThermOptCC to identify stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions [14]

- Refine model by removing truly blocked reactions

Context-Specific Model Construction (Optional):

- Apply ThermOptiCS with omics data to build compact, thermodynamically consistent models [14]

Loopless Flux Analysis:

- Use ThermOptFlux for loopless flux sampling or other flux analysis methods [14]

- Generate thermodynamically feasible flux distributions

ThermOptCOBRA Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Thermodynamic Metabolic Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ThermOptCOBRA Suite | Comprehensive TIC identification and resolution | Genome-scale metabolic model refinement [14] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB environment for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis | Implementing ll-COBRA and related methods [12] |

| COBRApy | Python package for constraint-based modeling | Flux analysis, loopless FBA implementation [22] |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase of genome-scale metabolic models | Model validation and comparison [12] |

| Group Contribution Method | Estimation of standard free energy of reactions (ΔG°°) | Thermodynamic constraint parameterization when experimental data is unavailable [12] |

Loop Detection Logic

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are fundamental for predicting cellular behavior in various research and drug development contexts. A significant limitation affecting their predictive accuracy is the presence of Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles (TICs), also known as loops or futile cycles [12] [13]. These are closed loops of reactions that can, in theory, sustain flux indefinitely without consuming any net substrates or producing any net products, thereby violating the second law of thermodynamics by creating a perpetual motion machine [13]. The presence of TICs can lead to unrealistic flux predictions and compromise the reliability of simulation results, including those from Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and flux sampling methods [12] [21]. The ThermOptCobra tool suite was developed as a comprehensive solution to this problem, integrating thermodynamic constraints directly into model construction and analysis to eliminate these infeasible cycles and yield more refined, reliable models [14].

Understanding ThermOptCobra's Core Architecture

ThermOptCobra is not a single tool but a suite of four integrated algorithms designed to work together to address TICs from different angles [14].

- ThermOptCC: Rapidly identifies reactions that are both stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked.

- ThermOptiCS: Constructs compact, thermodynamically consistent context-specific models.

- ThermOptFlux: Enables loopless flux sampling for more accurate metabolic predictions.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and relationships between these components within a typical model refinement process.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a stoichiometrically blocked reaction and a thermodynamically blocked one?

- Stoichiometrically Blocked Reaction: A reaction that cannot carry any flux under steady-state conditions due to the network's connectivity and mass balance constraints alone [23] [22]. For example, if a reaction's essential substrate cannot be produced by any other part of the network, that reaction is stoichiometrically blocked. Tools like

find_blocked_reactionsin cobrapy or FASTCC can identify these [23] [22]. - Thermodynamically Blocked Reaction: A reaction that, while potentially stoichiometrically feasible, is prevented from carrying flux because its direction would violate thermodynamic laws. This often occurs when a reaction is part of a Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycle (TIC). Preventing flux through this reaction is necessary to break the loop and restore thermodynamic feasibility [14] [12].

Q2: During Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), my solution contains loops. How can ThermOptCobra help?

Classic FBA solutions often contain TICs because the optimization does not inherently account for the loop law [12] [13]. ThermOptCobra addresses this by allowing you to perform Loopless FBA (ll-FBA). This method adds a set of constraints to the original FBA problem, ensuring that the optimized flux distribution does not contain any thermodynamically infeasible cycles, leading to more realistic predictions [12] [24].

Q3: I am using flux sampling to explore the solution space, but my samples are contaminated with loops. What can I do?

Flux sampling is highly susceptible to artifacts from TICs, as these cycles can create unbounded dimensions in the flux space, biasing the probability distributions of fluxes [21]. ThermOptFlux, a component of ThermOptCobra, is specifically designed to enable loopless flux sampling [14]. By integrating thermodynamic constraints directly into the sampling algorithm, it ensures that every generated sample is free from loops, providing a more accurate representation of the thermodynamically feasible flux space.

Q4: What should I do if ThermOptCobra identifies a key metabolic reaction as blocked?

First, verify the finding. Check the reaction's directionality (reversibility) in the model against current biochemical literature, as incorrect assignment is a common cause of thermodynamic infeasibility [13]. If the reaction is indeed irreversible, updating the model's constraints can resolve the issue. Use the visualization tools in ThermOptCobra to trace the loop in which the reaction is involved. This can help identify if the blockage is due to a network-level inconsistency that might require a curation step, such as adding a missing transport reaction or correcting a gene-protein-reaction (GPR) rule [25].

Experimental Protocol: Detecting Blocked Reactions with ThermOptCobra

This protocol outlines the key steps for using ThermOptCobra to identify and remove blocked reactions from a genome-scale metabolic model.

Objective: To refine a metabolic model by detecting and removing stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions, thereby eliminating thermodynamically infeasible cycles.

Materials and Software:

- Metabolic Model: A genome-scale metabolic model in SBML format.

- ThermOptCobra Toolbox: Installed and configured on a MATLAB or Python environment.

- Linear Programming (LP) & Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) Solver: Such as Gurobi or CPLEX, configured for use with ThermOptCobra.

Procedure:

Model Import and Pre-processing:

- Load your metabolic model into the ThermOptCobra environment.

- Ensure all exchange reactions (boundary reactions) are correctly defined to reflect the experimental conditions of interest.

Stoichiometric Consistency Check:

- Run an initial consistency check, such as FASTCC, to identify reactions that are stoichiometrically blocked in the context of the defined medium [23]. This step identifies reactions incapable of carrying flux under any thermodynamically feasible condition.

Thermodynamic Analysis with ThermOptCC:

- Execute the ThermOptCC algorithm. This module leverages network topology to rapidly detect not only stoichiometrically blocked reactions but also those that are thermodynamically blocked [14].

- The algorithm outputs a refined list of all blocked reactions.

Loop Removal and Model Refinement:

- Use the output from ThermOptCC to create a consistent model. This may involve removing the blocked reactions or applying loop-law constraints for further analysis.

- Alternatively, to generate a context-specific model that is inherently thermodynamically consistent, use the ThermOptiCS algorithm. It has been shown to build more compact models than Fastcore in 80% of cases [14].

Validation and Downstream Analysis:

- Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) or flux sampling on the refined model using ThermOptFlux to ensure predictions are thermodynamically feasible [14].

- Compare the flux distributions and growth predictions before and after refinement to assess the impact of removing TICs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential computational tools and concepts for addressing thermodynamic infeasibility.

| Tool / Concept | Function in Analysis | Relevance to ThermOptCobra |

|---|---|---|

| Loopless FBA (ll-FBA) | A variant of FBA that incorporates constraints to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible loops from the flux solution [12]. | ThermOptFlux enables ll-FBA, improving the accuracy of optimal flux predictions [14]. |

| Flux Sampling | A technique to randomly sample the steady-state flux space to understand the range of possible metabolic behaviors [21]. | ThermOptFlux provides loopless flux sampling, preventing bias from TICs in the sampled distributions [14]. |

| Nullspace of S | The basis for the nullspace of the stoichiometric matrix defines all steady-state flux solutions, including loops [12]. | ThermOptCobra algorithms use the nullspace to identify and eliminate loops by applying thermodynamic constraints [24]. |

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | An optimization framework used when problems require discrete decisions (e.g., a reaction is either on or off). | ll-FBA is reformulated as a MILP problem, which can be computationally challenging for large models [12] [26]. |

| Context-Specific Model | A model extracted from a global GEM to represent metabolism in a specific cell type or condition. | ThermOptiCS is used to build thermodynamically consistent context-specific models [14]. |

Building Compact, Thermodynamically Consistent Models with ThermOptiCS

FAQs: Addressing Common Questions on ThermOptiCS

Q1: What is the primary function of ThermOptiCS, and how does it differ from other CSM-building algorithms?

A1: ThermOptiCS is an algorithm designed to construct context-specific models (CSMs) that are both compact and thermodynamically consistent [1]. It belongs to the core reaction-required (CRR) group of algorithms. Unlike other algorithms in this group (such as Fastcore), which only consider stoichiometric and expression-data constraints, ThermOptiCS incorporates additional constraints to remove thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) during the model construction process itself [1]. This results in models free of blocked reactions arising from thermodynamic infeasibility.

Q2: Why are thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) a problem in metabolic models?

A2: TICs, sometimes called "futile cycles" or "internal loops," are network cycles that can carry a non-zero flux without any net input or output of nutrients [12] [1]. They are analogous to perpetual motion machines and violate the second law of thermodynamics because the metabolic driving forces around the cycle cannot add up to zero [12]. Their presence can lead to:

- Distorted flux distributions [1].

- Erroneous predictions of cellular growth and energy production [1].

- Unreliable gene essentiality predictions [1].

- Compromised integration with multi-omics data [1].

Q3: What are the input requirements for running ThermOptiCS?

A3: ThermOptiCS primarily operates on the following inputs [1]:

- Stoichiometric Matrix (S): Defines the metabolic network structure.

- Reaction Directionality and Flux Bounds: Specify the lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux.

- Transcriptomic (Omics) Data: Used to identify the set of core or active reactions that have high expression evidence in the specific biological context. Notably, the algorithm does not require external experimental data like Gibbs free energy values to resolve TICs during model construction [1].

Q4: What does "compact" mean in the context of models built by ThermOptiCS?

A4: In direct comparisons, models built using ThermOptiCS were found to be more compact than those built with Fastcore in 80% of cases [1]. A compact model contains a minimized set of reactions necessary to support the core, active reactions while ensuring thermodynamic feasibility, thereby eliminating unnecessary metabolic steps that could host TICs.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Fails to Build or is Infeasible Potential Cause and Solution:

- Overly Restrictive Core Reaction Set: The set of reactions identified as "active" via transcriptomic data may be inconsistent with the network topology and thermodynamic constraints. Re-check the consistency of your core set. Ensure that the core reactions can form a connected network without violating mass balance or thermodynamic laws, even after adding minimal supporting reactions.

Problem: Final CSM Still Contains Blocked Reactions Potential Cause and Solution:

- Stoichiometric vs. Thermodynamic Blockage: ThermOptiCS eliminates reactions blocked due to thermodynamic infeasibility. If blocked reactions persist, they are likely stoichiometrically blocked (e.g., due to dead-end metabolites). Use the companion algorithm ThermOptCC to rapidly identify all stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions for further model curation [1].

Problem: High Computational Time During Model Construction Potential Cause and Solution:

- Large, Dense Metabolic Network: The presence of a very large number of potential TICs can slow down the optimization. Prior to running ThermOptiCS, use ThermOptEnumerator to efficiently identify all TICs in your generic model. Manually curating the model to remove redundant reactions or applying directionality constraints based on this list can simplify the network and speed up CSM construction [1].

Problem: Integration with Downstream Flux Analysis Yields Loopy Flux Distributions Potential Cause and Solution:

- Loops in Flux Sampling: While the model structure is loopless, certain flux analysis methods (like some samplers) can still generate solutions with loops. Use the ThermOptFlux method to check for and remove loops from any flux distribution, projecting it to the nearest thermodynamically feasible state [1].

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a CSM with ThermOptiCS

The following workflow details the steps for building a context-specific model using ThermOptiCS.

1. Input Preparation

- Generic Genome-Scale Metabolic Model (GEM): Obtain a stoichiometric matrix (S) along with lower and upper bounds (lb, ub) for all reactions. Ensure the model is carbon and energy balanced [12] [1].

- Context-Specific Transcriptomic Data: Acquire gene or protein expression data (e.g., RNA-Seq, Microarray) for the specific biological condition of interest.

2. Define the Core Reaction Set

- Process the transcriptomic data to map gene expression levels to metabolic reactions in the GEM.

- Apply a predefined threshold (e.g., top percentile, absolute expression cutoff) to select a set of reactions with high expression evidence. This set is defined as the "core" active reactions.

3. Execute ThermOptiCS Optimization

- The ThermOptiCS algorithm formulates a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem. The objective is to find the minimal set of reactions to add to the core set such that: a) All core reactions can carry a non-zero flux (stoichiometric feasibility). b) The resulting network contains no thermodynamically infeasible cycles (thermodynamic consistency) [1].

- Solve the MILP problem using a compatible solver (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX).

4. Output and Validation

- The output is a thermodynamically consistent CSM.

- Validate the model by ensuring it can perform known metabolic functions and by comparing its predictions against experimental data.

Performance Data of ThermOptiCS

The following table summarizes key quantitative performance metrics for the ThermOptCOBRA suite, which includes ThermOptiCS, as reported in validation studies [1].

| Metric | Algorithm | Performance Result | Context / Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSM Compactness | ThermOptiCS | More compact models in 80% of cases | Compared to Fastcore algorithm |

| TIC Enumeration Runtime | ThermOptEnumerator | Average 121-fold reduction in computational runtime | Compared to OptFill-mTFP across tested models |

| Blocked Reaction Identification Speed | ThermOptCC | Faster than loopless-FVA methods in 89% of models tested | Used for identifying stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions |

| TIC Analysis Scale | ThermOptEnumerator | Efficiently identified TICs in 7,401 published metabolic models | Demonstrates scalability and provides a resource for the community |

| Item / Resource | Function in Model Construction & Analysis |

|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB-based software suite that provides the computational environment for running ThermOptCOBRA algorithms [1]. |

| MILP Solver (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX) | Solves the optimization problems posed by ThermOptiCS and other algorithms in the suite to find feasible solutions [1]. |

| Stoichiometric Matrix (S) | The core mathematical representation of the metabolic network, defining metabolite relationships in reactions [12] [1]. |

| Gibbs Free Energy Data (ΔG°) | While not required for ThermOptiCS, estimated values can be used for additional model curation and validation [12]. |

| Transcriptomic Data Set | Provides the context-specific evidence (e.g., RNA-seq counts) used to define the core set of active reactions for ThermOptiCS [1]. |

| ThermOptEnumerator TIC List | A pre-computed list of TICs for a model, which can be used for manual curation to improve baseline model quality [1]. |

Applying FLUXestimator for Cell-Specific Fluxome Prediction from Transcriptomics Data

Understanding Thermodynamic Loops and the Need for Loopless Flux Analysis

What are thermodynamically infeasible loops, and why are they a problem in flux prediction? Thermodynamically infeasible loops, or "type III pathways," are internal cyclic flux modes within a metabolic network that involve no net conversion of substrates to products [27]. They violate the "loop law," which is analogous to Kirchhoff's second law for electrical circuits. This law states that at steady state, there can be no net flux around a closed network cycle because the thermodynamic driving forces around such a cycle must sum to zero [12] [28]. When flux predictions contain these loops, they represent biologically impossible scenarios, obscuring meaningful statistical inference and leading to unrealistic simulation results [12] [27].

How does FLUXestimator address this challenge? FLUXestimator itself is designed to predict flux from transcriptomic data. The broader field of Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) has developed specific methods to eliminate these loops. A key approach is Loopless COBRA (ll-COBRA), a mixed integer programming (MIP) method that adds constraints to ensure any predicted steady-state flux solution is compatible with the loop law [12]. Furthermore, advanced sampling algorithms like LooplessFluxSampler have been developed to efficiently and uniformly sample the non-convex, loopless flux solution space, providing more reliable estimates of metabolic capabilities [27]. While FLUXestimator uses neural networks and flux balance regularization [2], being aware of this thermodynamic principle is crucial for interpreting results and understanding the limitations of different flux estimation methods.

FLUXestimator FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q: What is FLUXestimator, and what is its primary function? A: FLUXestimator is a web server that predicts cell-specific metabolic flux and variations using single-cell or bulk transcriptomics data. It implements the single-cell Flux Estimation Analysis (scFEA) method, which uses a novel neural network architecture to estimate reaction rates from gene expression data [29] [2]. Its primary function is to infer the fluxome—the distribution of fluxes through a metabolic network—at the resolution of individual cells or samples, enabling the study of metabolic heterogeneity in complex tissues.

Q: What are the key inputs and outputs of FLUXestimator? A:

- Inputs: The main input is a transcriptomics profile matrix (e.g., from scRNA-seq), where rows are genes and columns are cells or samples. FLUXestimator accepts various input formats and gene IDs for multiple species [2]. The user must also select a pre-curated metabolic network.

- Outputs: The analysis generates two key results [30] [2]:

- Predicted Flux Distribution: A matrix of estimated reaction rates for each metabolic module in every cell/sample.

- Metabolite Variation (Balance): A matrix indicating the predicted accumulation or depletion of intermediate metabolites in each cell/sample, reflecting metabolic stress or imbalance.

Q: The tool reports "metabolite stress" or "imbalance." What does this mean? A: Unlike traditional Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which imposes a strict steady-state constraint where all fluxes must balance perfectly, scFEA (the model behind FLUXestimator) uses a quadratic loss function to regularize flux balance. This allows for small deviations from perfect balance at the individual cell level, which are reported as "metabolite stress" or "imbalance" [2]. This can be biologically informative, reflecting dynamic changes in metabolite pools or cellular stress states that a strict steady-state assumption would mask.

Q: Which organisms and metabolic pathways does FLUXestimator support? A: FLUXestimator provides access to manually curated metabolic networks for human, mouse, and 15 other common experimental organisms [29] [2]. The table below summarizes the key curated networks available for human and mouse.

Table 1: Curated Metabolic Networks in FLUXestimator (Human & Mouse)

| Network Name | Description | # Modules | # Intermediate Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|

| M171 | Central Metabolic Network | 171 | 70 |

| M171_NAD | M171 + Redox balance of NAD+/NADH | 172 | 71 |

| GlucoseGlutamine (GGSL) | Glycolysis, TCA cycle, glutamine, and glutathione metabolism with subcellular localization. | 41 | 37 |

| GlucoseTCAcycle | Glycolysis and TCA cycle | 15 | 12 |

| Branched Chain Amino Acids | Metabolism of valine, leucine, and isoleucine. | 9 | 7 |

| MHC class I antigen | Metabolic pathway for MHC class I antigen presentation. | 8 | 6 |

Source: Adapted from FLUXestimator documentation [2].

Q: What are the common computational requirements or issues when running FLUXestimator? A: The standalone version of scFEA (the engine behind FLUXestimator) is implemented in Python and can require significant computational resources.

- GPU Acceleration: For large datasets (over 10,000 cells), the general pipeline can be time-consuming without a GPU. The developers provide a sampling and fitting function for large datasets to mitigate this [30].

- Input Data: The tool can work with both raw and normalized counts. It also includes an option for single-cell data imputation (recommended for sparse data like from 10x Genomics) [30].

- Pre-processing: The metabolic networks used by FLUXestimator have been simplified into modules to enhance computational feasibility. Common molecules like H₂O and H⁺ are often excluded from the flux balance constraints as their concentrations are assumed to be large and relatively constant [2].

Experimental Workflow and Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for using FLUXestimator, from data input to biological interpretation, while considering thermodynamic constraints.

Diagram Title: FLUXestimator Analysis Workflow

Detailed Protocol for a Typical FLUXestimator Analysis:

- Data Preparation: Prepare your input data as a matrix file (e.g., CSV) where rows are genes and columns are cells or samples. Ensure gene identifiers match those expected by FLUXestimator (e.g., official gene symbols) [30] [2].

- Network Selection: On the FLUXestimator webserver, select the species and the most appropriate pre-curated metabolic network for your biological question (refer to Table 1). For a broad overview, the M171 central metabolic network is a common starting point [2].

- Parameter Configuration: Adjust algorithm parameters as needed. A key parameter is the tolerance for flux balance imbalance. The default settings are a good starting point for most users.

- Job Submission and Execution: Submit the job via the webserver. For large datasets, be prepared for potentially long computation times. The standalone

scFEApackage allows for more control, including the use of a GPU to accelerate processing [30]. - Result Analysis and Validation:

- Use the provided output files to analyze metabolic heterogeneity across cell types or conditions.

- Correlate predicted metabolite "stress" with external metabolomics data, if available, for validation [30].

- Perform downstream analyses such as clustering cells based on their predicted flux profiles to identify metabolically distinct subpopulations.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Loop-Aware Metabolic Flux Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | URL / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLUXestimator / scFEA | Webserver & Python Package | Predicts cell-wise metabolic flux from transcriptomics data. | http://scFLUX.org/ [29] [2] |

| LooplessFluxSampler | MATLAB Toolbox | Uniformly samples the loopless mass-balanced flux solution space of metabolic models. | Integrated with COBRA Toolbox [27] |

| ll-COBRA (loopless COBRA) | Computational Method | A Mixed Integer Programming framework to eliminate thermodynamically infeasible loops from steady-state flux solutions. | [12] |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB Package | A central software platform for constraint-based metabolic modeling and analysis. | [12] [27] |

| BiGG Models | Knowledgebase | A repository of high-quality, curated genome-scale metabolic models. | [12] |

Enabling Loopless Flux Sampling for Accurate Predictions with ThermOptFlux

Thermodynamically infeasible cycles (TICs) in genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent a significant challenge in computational biology, leading to flux predictions that violate the second law of thermodynamics. These cycles, analogous to perpetual motion machines, allow non-zero flux to persist without any input or output of nutrients, ultimately compromising the biological relevance of simulation results [1]. ThermOptFlux emerges as a sophisticated solution within the ThermOptCOBRA suite, specifically designed to enable loopless flux sampling and ensure thermodynamically consistent flux distributions [1] [14].

Traditional flux sampling methods like ll-ACHRB (loopless Artificial Centering Hit-and-Run on a Box) and ADSB (Adaptive Direction Sampling on a Box) have attempted to address this challenge but face limitations. These samplers primarily consider only linearly independent TICs as sources of loops, which can result in samples that still contain thermodynamically infeasible fluxes [1]. ThermOptFlux introduces a more robust approach by utilizing a TICmatrix derived from ThermOptEnumerator, enabling comprehensive loop detection and removal across the entire metabolic network [1]. This methodological advancement represents a significant step forward in achieving reliable, biologically plausible flux predictions for applications ranging from metabolic engineering to drug development.

Technical Foundations

Understanding Thermodynamically Infeasible Cycles

Thermodynamically infeasible cycles violate the "loop law," which is analogous to Kirchhoff's second law for electrical circuits. This law states that at steady state, there can be no net flux around a closed network cycle [12]. In metabolic terms, flux solutions with active closed loops are not only unrealistic but obscure meaningful statistical inference of metabolic capabilities [27].

Key Characteristics of TICs:

- They operate without net substrate consumption or product formation

- They generate ATP or other energy molecules without input

- They produce unrealistically high fluxes that distort metabolic predictions

- They violate the second law of thermodynamics by functioning as perpetual motion machines [1]

The presence of TICs can significantly distort flux balance analysis (FBA), flux variability analysis (FVA), and sampling results, leading to erroneous biological interpretations. For instance, in one documented case, a user observed unrealistically high fluxes (-992.2 and 992.1) through succinyl-CoA synthetase and acyl-CoA thioesterase reactions, which formed a loop that affected ATP/ADP balance despite minimal carbon input [31].

The ThermOptFlux Methodology

ThermOptFlux addresses the limitations of previous approaches through a multi-stage process:

TICmatrix Construction: Using ThermOptEnumerator, the algorithm efficiently identifies all TICs within a metabolic network based on topological characteristics of the stoichiometric matrix. This represents a significant improvement over earlier methods, with an average 121-fold reduction in computational runtime across tested models [1].

Loop Detection and Validation: The derived TICmatrix enables comprehensive checking for loops in flux samples. This approach is computationally more efficient than existing loop-checking methods and can be applied to both sampling outputs and individual flux distributions [1].

Flux Projection: ThermOptFlux can project a loop-containing flux distribution to the nearest thermodynamically feasible distribution in the flux space, effectively removing biologically unreasonable cycles while maintaining stoichiometric constraints [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Persistent High Fluxes After Loopless Constraints

Problem: Despite applying loopless constraints, unrealistically high fluxes persist in sampling results, often affecting energy metabolism reactions.

Solution Checklist:

- Verify that the TICmatrix comprehensively covers all network reactions

- Check for stoichiometric inconsistencies in the model, particularly in ATP-producing cycles

- Validate reaction directionality constraints against thermodynamic databases

- Ensure the sampling algorithm has sufficiently converged using diagnostic tools

Case Example: A user reported persistent high fluxes through succinyl-CoA synthetase and acyl-CoA thioesterase reactions even after applying loopless FVA. The solution involved identifying and correcting an internal ATP-generating cycle that bypassed normal thermodynamic constraints [31].

Sampling Convergence and Performance Issues

Problem: Flux sampling algorithms exhibit slow convergence or fail to adequately explore the thermodynamically constrained solution space.

Recommended Approach:

- Implement the Coordinate Hit-and-Run with Rounding (CHRR) algorithm, which has demonstrated 2.5-8 times faster performance compared to alternatives like ACHR and OPTGP, depending on model complexity [32]

- Utilize Markov Chain diagnostics to assess sampling quality and convergence

- Ensure proper pre-processing and rounding of the solution space to improve conditioning

Table: Performance Comparison of Sampling Algorithms

| Algorithm | Relative Speed | Convergence Quality | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHRR | 2.5-8x faster than alternatives | Highest convergence rate | Large-scale models |

| ADSB | Moderate speed | Theoretical guarantees | Loopless sampling |

| ll-ACHRB | Slower performance | Approximate, non-uniform | Quick approximations |

| OPTGP | 2.5-3.3x slower than CHRR | Moderate convergence | Parallel environments |

Model-Specific Thermodynamic Validation

Problem: Uncertainties in model reconstruction, particularly regarding reaction directionality and cofactor usage, introduce TICs that persist despite sampling constraints.

Validation Protocol:

- Identify Blocked Reactions: Use ThermOptCC to detect stoichiometrically and thermodynamically blocked reactions [1]