Engineering Robust Microbial Cell Factories: Strategies for Enhanced Performance and Stability in Industrial Bioprocesses

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary strategies to enhance the robustness of microbial cell factories, a critical determinant for successful industrial-scale bioproduction.

Engineering Robust Microbial Cell Factories: Strategies for Enhanced Performance and Stability in Industrial Bioprocesses

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary strategies to enhance the robustness of microbial cell factories, a critical determinant for successful industrial-scale bioproduction. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of microbial robustness and its distinction from mere tolerance. The review systematically covers advanced engineering methodologies—including transcription factor engineering, membrane engineering, and dynamic pathway control—and addresses central challenges such as the growth-production trade-off and genetic instability. Further, we examine rigorous quantification techniques for validating robustness and present comparative analyses of strain performance. By synthesizing knowledge-based, computational, and evolutionary approaches, this work serves as a strategic guide for developing next-generation, resilient microbial systems for efficient and predictable manufacturing of biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and fine chemicals.

Defining Microbial Robustness: The Cornerstone of Predictable Industrial Bioproduction

In the development of advanced microbial cell factories (MCFs), strain robustness and tolerance are critical performance characteristics, yet they are often incorrectly used interchangeably in industrial microbiology [1] [2]. This distinction is not merely semantic but fundamental to predicting how a strain will perform when scaled from controlled laboratory conditions to industrial bioprocesses. Robustness refers to the ability of a microbial strain to maintain stable production performance (titer, yield, and productivity) despite experiencing various genetic, metabolic, or environmental perturbations [1] [2]. In contrast, tolerance describes the capacity of cells to grow or survive when exposed to single or multiple stresses, typically measured through growth-related parameters like viability or specific growth rate [1]. Understanding this distinction is crucial for designing MCFs that deliver consistent, high-level production in industrial environments characterized by unpredictable fluctuations.

Theoretical Framework: Defining the Concepts

Core Definitions and Distinctions

The performance of microbial cell factories under stress conditions can be categorized into two complementary but distinct concepts:

- Robustness: A systems-level property reflecting the phenotypic stability of a strain. A robust strain maintains constant production metrics (titer, yield, productivity) when faced with diverse perturbations encountered in scale-up bioprocesses [1] [2]. Robustness encompasses performance stability beyond mere survival.

- Tolerance: A survival-focused characteristic indicating cellular ability to withstand stress conditions. It is primarily concerned with growth maintenance or survival under single or multiple perturbations and does not guarantee sustained production capacity [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics Differentiating Microbial Robustness and Tolerance

| Feature | Robustness | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Stability of production performance | Cellular survival and growth |

| Key Metrics | Titer, yield, productivity maintenance | Specific growth rate, viability |

| Scope | Systems-level property | Often stress-specific |

| Industrial Relevance | Predictable production in variable conditions | Survival under specific stress conditions |

| Genetic Basis | Often polygenic, involving global regulators | Can be specific to stress response pathways |

Conceptual Relationship

The relationship between robustness and tolerance can be visualized as a hierarchical framework where robustness represents a more comprehensive, systems-level property that incorporates but extends beyond tolerance. As noted in research on microbial cell factories, "strains with higher tolerance do not guarantee a higher yield, while the strain with higher robustness must have a higher tolerance" [1]. This establishes that robustness represents a more comprehensive characteristic that inherently requires a foundation of tolerance but adds the critical dimension of production stability.

Quantitative Evaluation Frameworks

Metrics and Assessment Protocols

Accurately distinguishing between robustness and tolerance requires specific quantitative frameworks and experimental approaches. The metrics used for each concept reflect their fundamentally different focuses in evaluating strain performance.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Robustness vs. Tolerance

| Assessment Type | Robustness Metrics | Tolerance Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Parameters | Production titer stability, Yield consistency, Productivity maintenance | Specific growth rate (μ), Cell viability, Lethal concentration (LC50) |

| Temporal Metrics | Coefficient of variation in production over time, Performance half-life under stress | Lag phase duration, Growth recovery rate |

| Population Metrics | Population heterogeneity in production capacity, Plasmid stability in fermenters | Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), Death rate kinetics |

| Process Metrics | Performance predictability across scales, Consistency between batches | Survival rate under shock conditions, Adaptation speed |

Experimental Workflow for Concurrent Assessment

A comprehensive strain evaluation strategy should simultaneously measure both tolerance and robustness parameters to fully characterize industrial potential. The integrated protocol below enables researchers to distinguish between these characteristics experimentally.

Protocol: Concurrent Assessment of Tolerance and Robustness

Materials:

- Test microbial strain(s)

- Appropriate growth medium

- Stress-inducing compounds (e.g., ethanol, organic acids, inhibitors)

- Bioreactor or controlled culture system

- OD600 spectrophotometer or cell counter

- HPLC, GC-MS, or other product analytics

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow test strain overnight under optimal conditions.

- Experimental Setup: Divide culture into two treatment groups:

- Control Group: Maintained at optimal conditions throughout

- Stress Group: Exposed to predetermined stress conditions (e.g., pH shift, inhibitor addition, temperature change)

- Monitoring Phase: Sample cultures regularly over 24-72 hours:

- For Tolerance Assessment: Measure OD600, cell viability (CFU/mL), and calculate specific growth rates

- For Robustness Assessment: Analyze product titer, yield, and productivity

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Tolerance Index = (Growth rate under stress / Growth rate under optimal conditions) × 100

- Calculate Robustness Coefficient = (Productivity under stress / Productivity under optimal conditions) × 100

Interpretation: Strains with high Tolerance Index but low Robustness Coefficient survive well but perform poorly under stress. Industrial applications require strains that maximize both parameters, with particular emphasis on Robustness Coefficient for production stability.

Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Robustness

Transcription Factor Engineering

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) represents a powerful approach for enhancing robustness by reprogramming cellular responses to multiple stresses simultaneously. This method involves introducing mutations in generic transcription factors that control broad regulons, enabling multi-point regulation that can enhance stability under industrial conditions [1].

Protocol: Global Transcription Machinery Engineering for Robustness

Materials:

- EpPCR kit for random mutagenesis

- Plasmid library of mutated transcription factor genes

- Selection markers (antibiotics)

- Stress conditions for screening (e.g., ethanol, low pH, inhibitors)

Procedure:

- Library Construction:

- Amplify global transcription factor genes (e.g., rpoD in E. coli, SPT15 in S. cerevisiae) using error-prone PCR

- Clone mutated genes into appropriate expression vectors

- Transformation and Selection:

- Introduce plasmid library into host strain

- Plate transformants on stress-containing media (e.g., 60 g/L ethanol for E. coli, 6% v/v ethanol for S. cerevisiae)

- Screening:

- Isolate colonies showing improved growth under stress conditions

- Evaluate production performance of selected mutants under fluctuating conditions

- Validation:

- Measure robustness coefficients of promising mutants

- Sequence mutated transcription factors to identify beneficial mutations

Application Example: Engineering the housekeeping sigma factor δ70 in E. coli improved tolerance to 60 g/L ethanol and high concentrations of SDS, while resulting in a high yield of lycopene, demonstrating enhanced robustness [1].

Membrane and Transporter Engineering

Cellular membranes serve as primary interfaces with the environment, and their engineering can significantly enhance robustness by maintaining functional integrity under stress conditions. Membrane engineering focuses on modifying lipid composition to improve integrity, regulate mobility, and control permeability [1].

Protocol: Membrane Lipid Engineering for Robustness

Materials:

- Genes for fatty acid desaturases (e.g., OLE1 from S. cerevisiae)

- Genes for elongases (e.g., rELO2)

- cis-trans isomerase genes (e.g., from Pseudomonas aeruginosa)

- Fatty acid analysis equipment (GC-MS)

Procedure:

- Genetic Modification:

- Overexpress desaturase genes to increase unsaturated fatty acid content

- Express heterologous elongases or isomerases to modify membrane fluidity

- Membrane Analysis:

- Extract and analyze membrane lipids from engineered strains

- Calculate ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids

- Robustness Testing:

- Challenge engineered strains with multiple stresses (ethanol, organic acids, temperature)

- Measure both growth parameters (tolerance) and production stability (robustness)

- Optimization:

- Fine-tune expression levels of membrane-modifying enzymes

- Combine multiple membrane engineering strategies for synergistic effects

Application Example: Overexpression of Δ9 desaturase Ole1 from S. cerevisiae increased the membrane oleic acid content and ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids, improving tolerance to acid, NaCl, and ethanol stresses [1].

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution (ALE) for Robustness

Adaptive Laboratory Evolution applies selective pressure over multiple generations to enrich for mutants with enhanced robustness characteristics. Unlike targeted engineering, ALE can uncover novel robustness mechanisms through natural selection under simulated industrial conditions [3].

Case Study: Robustness Engineering in Yeast Platforms

Comparative Analysis of Yeast Chassis

The selection of microbial chassis with inherent robustness characteristics provides a foundation for engineering superior production strains. Recent research has highlighted the exceptional innate robustness of nonconventional yeasts like Pichia kudriavzevii compared to traditional Saccharomyces cerevisiae [4].

Table 3: Innate Stress Tolerance and Robustness Potential of Yeast Chassis

| Stress Factor | S. cerevisiae Performance | P. kudriavzevii Performance | Industrial Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low pH | Limited tolerance (pH ~3) | Exceptional tolerance (pH as low as 1.5) | Organic acid production, acidic fermentation |

| High Temperature | Moderate (up to 35-37°C) | High (up to 50°C) | Reduced cooling costs, contamination control |

| Inhibitors | Sensitive to furanics, phenolics | High tolerance to lignocellulosic inhibitors | Lignocellulosic biorefining |

| Ethanol | High tolerance | High tolerance | Biofuel production |

| Osmotic Stress | Moderate tolerance | High tolerance | High-gravity fermentations |

Protocol: Leveraging Innate Robustness in Nonconventional Yeasts

Materials:

- P. kudriavzevii strain (e.g., CABBI flagship strain)

- CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system for nonconventional yeasts

- Lignocellulosic hydrolysate or synthetic inhibitor mix

- Low-pH fermentation media

Procedure:

- Strain Development:

- Engineer P. kudriavzevii with product pathways using adapted CRISPR-Cas9

- Integrate heterologous genes for target compound production

- Robustness Testing:

- Cultivate engineered strains in non-detoxified lignocellulosic hydrolysate

- Monitor production performance under progressively lower pH conditions

- Compare productivity stability with S. cerevisiae controls

- Process Optimization:

- Determine minimum need for pH adjustment during fermentation

- Evaluate reduction in byproduct formation (e.g., glycerol)

- Scale-Up Validation:

- Test robustness in bioreactors with variable feeding strategies

- Assess performance consistency across multiple batches

Application Insight: P. kudriavzevii has demonstrated the ability to produce succinic acid without neutralizer addition, leveraging its high innate acid tolerance to maintain stable production as pH drops during fermentation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Robustness and Tolerance Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Transcription Factors | rpoD (σ⁷⁰) in E. coli, SPT15 in S. cerevisiae | Reprogram cellular response to multiple stresses | gTME for multi-stress robustness |

| Membrane Modifiers | Ole1 desaturase, rELO2 elongase, cis-trans isomerase | Alter membrane fluidity and integrity | Enhancing tolerance to solvents, acids |

| Stress Reporting Systems | GFP-based biosensors, stress-responsive promoters | Quantify single-cell stress responses | Real-time monitoring of population heterogeneity |

| CRISPR Tools | Cas9, base editors, CRISPRi | Targeted genome engineering | Rapid integration of robustness features |

| Analytical Standards | Internal standards for metabolites, FAME standards | Quantify products and membrane composition | Robustness coefficient calculation |

| Evolutionary Selection | Automated ALE systems, chemostat arrays | Apply selective pressure for robustness | Uncovering novel robustness mechanisms |

The critical distinction between robustness and tolerance provides an essential framework for designing next-generation microbial cell factories. While tolerance focuses on survival under stress, robustness encompasses the preservation of production performance—a decisive factor for industrial viability. Engineering strategies that target global regulators, membrane properties, and employ adaptive evolution can significantly enhance robustness beyond basic tolerance. Moreover, selection of inherently robust chassis organisms like P. kudriavzevii provides a powerful foundation for constructing cell factories that maintain stable production under the variable and challenging conditions of industrial bioprocesses. As synthetic biology advances, explicitly designing for robustness rather than merely tolerance will be crucial for developing economically viable biomanufacturing platforms.

The pursuit of sustainable biomanufacturing using microbial cell factories is fundamentally challenged by the industrial perturbation space—a complex matrix of stressors ranging from internal metabolic toxicity to external large-scale environmental gradients. These perturbations, which include toxic intermediate metabolites, product toxicity, and variations in temperature, pH, and osmotic pressure, can significantly diminish production capacity and compromise process competitiveness [5]. Microbial robustness, defined as the ability of a microbial strain to maintain stable production performance (titers, yields, and productivity) despite various stochastic and predictable perturbations, has therefore emerged as a critical engineering target [6]. This Application Note establishes a structured framework to dissect this perturbation space, providing detailed protocols to quantify its impact and engineer superior robustness in industrial microorganisms, directly supporting advanced research within a thesis on microbial cell factory robustness.

Quantitative Profiling of the Perturbation Space

A critical first step is the systematic quantification of common industrial stressors and their synergistic effects on microbial physiology and production. The data in the table below summarizes key parameters for major perturbation categories.

Table 1: Characterization of Major Industrial Perturbations and Their Microbial Impacts

| Perturbation Category | Specific Stressors | Typical Experimental Range | Primary Microbial Impact | Common Measurement Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Toxicity | End-products (e.g., ethanol, butanol), intermediate metabolites | 10-100 g/L for solvents [6] | Membrane integrity, protein denaturation, metabolic burden | Intracellular ATP, membrane potential, ROS assays |

| Chemical Environment | Low pH, high osmolarity, solvent concentrations | pH 4.5-6.5; 0.9 mol/L NaCl [6] | Cytoplasmic acidification, osmotic imbalance, oxidative stress | Intracellular pH, compatible solute quantification, CFU counts |

| Environmental Gradients (Field-Derived) | Temperature, soil moisture, microbiome variation | Seasonal temperature simulations [7] | Shifts in community structure and metabolic function [7] | 16S rRNA sequencing, Metabolomics (LC-MS) |

| Process-Induced Stress | Shear force, substrate gradients, nutrient limitation | Varies with bioreactor scale and design | Phenotypic heterogeneity, reduced specific growth rate | Flow cytometry, RNA-seq for transcriptomic analysis |

Application Note: Mapping an Organism's Perturbation Profile

Objective: To comprehensively characterize the tolerance and robustness of a microbial strain to a matrix of industrially relevant stressors, generating a quantitative "perturbation profile."

Background: Engineered microbial cells in the laboratory often do not account for the multiple disturbances encountered in industrial conditions, leading to poor performance upon scale-up. A systematic profiling of the host's response to these stressors is a prerequisite for targeted engineering [6] [5].

Experimental Protocol 1: High-Throughput Phenotypic Microarray

Summary: This protocol uses a plate-reader-based assay to monitor growth and production kinetics under a factorial combination of stressors.

Materials:

- Strain: The microbial strain of interest (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae).

- Growth Media: Appropriate minimal or defined medium.

- Stress Stock Solutions: Prepare concentrated stocks of all stressors to be tested (e.g., ethanol, butanol, NaCl, organic acids, specific inhibitors).

- Equipment: Multimode plate reader with precise temperature control and shaking.

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow a seed culture overnight. Back-dilute into fresh medium and grow to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.5-0.8).

- Plate Setup: In a 96-well deep-well plate, prepare a factorial matrix of stressor combinations using the stock solutions. Include a no-stress control.

- Dilution and Dispensing: Dilute the mid-exponential phase culture to a target starting OD600 of 0.05 in each well of the stress matrix. Transfer 200 µL of each condition to a clear 96-well assay plate. Cover with a breathable seal.

- Kinetic Measurement: Load the assay plate into the plate reader. Run the kinetic program for 24-48 hours with continuous shaking, measuring OD600 (biomass) and fluorescence/absorbance (for fluorescent products or reporter genes) every 15-30 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Calculate key parameters for each well:

- Maximum Growth Rate (µmax): Derived from the slope of the ln(OD600) vs. time plot.

- Final Biomass Yield: Maximum OD600 reached.

- Product Titer: Concentration of the target molecule at the end of fermentation.

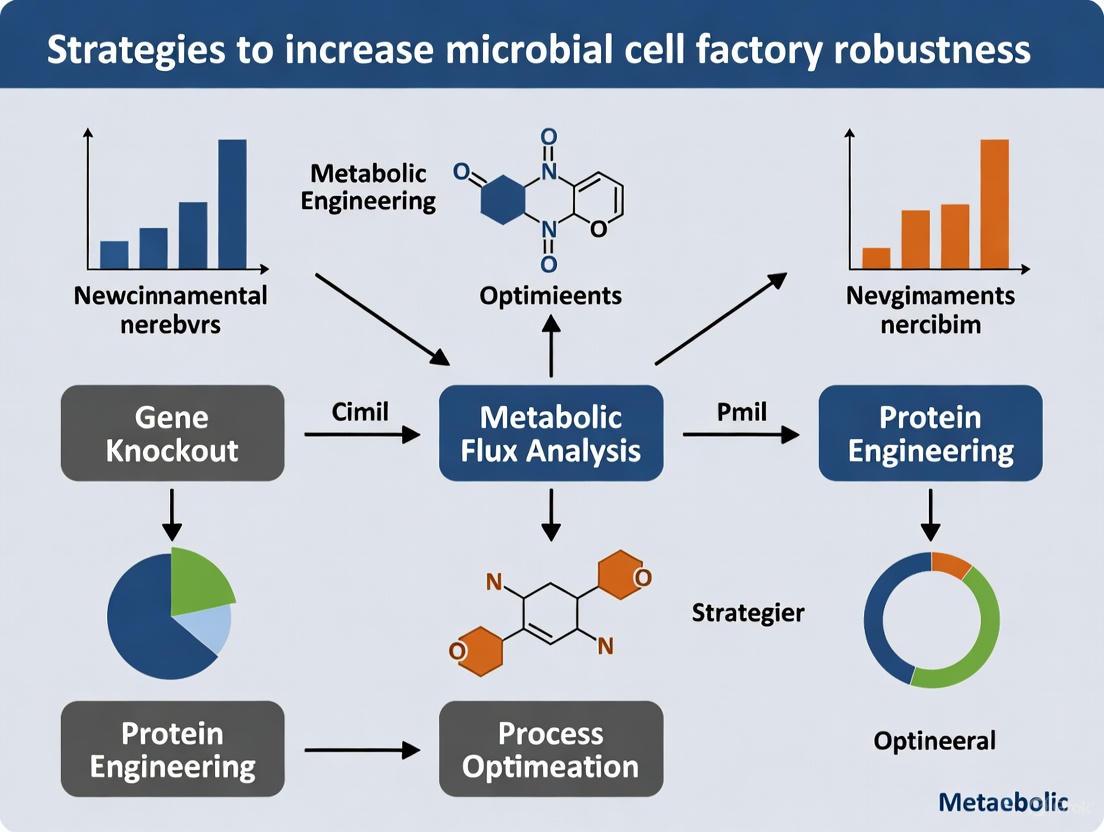

Visualization of the experimental workflow and the cellular response to perturbations is provided below.

Application Note: Engineering Robustness via Transcription Factor Engineering

Objective: To enhance microbial robustness by engineering global or specific transcription factors that reprogram cellular metabolism and stress responses.

Background: Transcription factors (TFs) are key proteins that control the fine-tuning expression of target genes. Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) is a powerful non-rational approach that involves introducing mutations into generic transcription-related proteins (e.g., sigma factors in bacteria) to trigger the reprogramming of gene networks and cellular metabolism, leading to improved tolerance phenotypes [6] [5].

Experimental Protocol 2: Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME)

Summary: This protocol involves creating mutant libraries of a global transcription factor and applying high-throughput selection to isolate variants conferring enhanced robustness.

Materials:

- Plasmid Vector: An expression plasmid harboring the gene for the target transcription factor (e.g., rpoD in E. coli).

- E. coli XL10-Gold or other high-efficiency cloning strains.

- Library Construction Reagents: Error-prone PCR kit, DpnI, T4 DNA Ligase.

- Selection Media: Agar plates containing the target stressor(s) at a predetermined inhibitory concentration.

Procedure:

- Library Generation:

- Perform error-prone PCR on the plasmid containing the TF gene to introduce random mutations.

- Digest the parent template with DpnI.

- Transform the mutated PCR product into a competent E. coli strain to generate a library of TF variants.

- Selection for Robustness:

- Plate the transformation output onto selection media containing the target stressor (e.g., 40 g/L ethanol, 0.9 mol/L NaCl). Also plate on non-selective media to determine library size and transformation efficiency.

- Incubate until colonies appear (typically 24-72 hours).

- Screening and Validation:

- Pick surviving colonies from the selective plates and inoculate into 96-deep well plates containing liquid media with and without the stressor.

- After 24-48 hours of growth, measure the final OD600 and the titer of the desired product.

- Identify clones that show superior growth and production under stress compared to the wild-type strain.

- Characterization:

- Sequence the TF gene in the best-performing clones to identify causative mutations.

- Re-transform the validated mutant TF plasmid into a fresh host strain to confirm the phenotype is linked to the TF variant.

Table 2: Key Transcription Factor Targets for Engineering Microbial Robustness

| Transcription Factor | Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Resulting Phenotype | Citation (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpoD (σ⁷⁰) | E. coli | gTME (mutant library) | Improved tolerance to 60 g/L ethanol and high SDS; increased lycopene yield | [6] |

| CRP | E. coli | Overexpression of mutant (K52I/K130E) | Enhanced osmotic tolerance (0.9 mol/L NaCl) | [6] |

| irrE | E. coli | Heterologous expression from D. radiodurans | 10-100x improved tolerance to ethanol or butanol stress | [6] |

| Rpb7 | S. cerevisiae | gTME | 40% increase in ethanol titers under 10% (v/v) ethanol stress | [6] |

| Haa1 | S. cerevisiae | Overexpression of mutant Haa1S135F | Significantly improved acetic acid tolerance | [6] |

Application Note: Integrating Environmental Gradient Data for Predictive Modeling

Objective: To leverage environmental monitoring data to predict chemical fate and its impact on microbial communities, informing the design of more robust bioremediation strains or processes.

Background: Field studies demonstrate that seasonal environmental variations (e.g., temperature, moisture) significantly shift the soil bacterial community structure and function, with direct implications for the degradation of environmental chemicals like the herbicide 2,4-D [7]. Understanding these community-level responses to gradients provides a blueprint for designing strains that can maintain functionality in fluctuating environments.

Experimental Protocol 3: Field-Relevant Gradient Simulation in Bioreactors

Summary: This protocol simulates dynamic environmental conditions, derived from field data, in controlled bioreactors to test microbial community or strain robustness.

Materials:

- Field Data: Historical or real-time data on environmental parameters (e.g., temperature, pH) from a target site [7].

- Bioreactor System: Bench-scale bioreactors with advanced control for temperature, pH, and feed.

- Analytical Equipment: LC-MS/MS for quantifying parent compounds and transformation products (e.g., 2,4-D and 2,4-DCP) [7].

Procedure:

- Gradient Profile Definition: Based on field data [7], program the bioreactor controllers to mimic a realistic environmental gradient over time (e.g., a 72-hour diurnal temperature cycle).

- Inoculation and Monitoring: Inoculate the bioreactor with the microbial community or engineered strain of interest. Initiate the dynamic environmental profile.

- Sampling: Take periodic samples for:

- Chemical Analysis: Quantify the degradation of the target substrate (e.g., 2,4-D) and the formation of any transformation products (e.g., 2,4-DCP) using LC-MS/MS [7].

- Microbial Analysis: Extract DNA for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to track community dynamics, or RNA for transcriptomic analysis of an engineered strain.

- Data Integration: Correlate the abiotic parameters (temperature, pH) with biotic outcomes (degradation rate, community structure, gene expression) to build a predictive model of performance under real-world fluctuating conditions.

The diagram below illustrates the strategy for engineering robust microbial cells by targeting key cellular components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Microbial Robustness Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Generates random mutations in a target DNA sequence for directed evolution. | Creating mutant libraries of transcription factors (e.g., rpoD) in gTME [6]. |

| Host-Aware Kinetic Models | Multi-scale computational models simulating cell- and population-level dynamics in a batch culture. | Identifying optimal "medium-growth, medium-synthesis" operating points to maximize productivity [8]. |

| Pluripotent Stem Cell (PSC) Models | Human cell-based models (hESCs, hiPSCs) for predictive toxicology of metabolites or environmental chemicals [9]. | Assessing potential human health impacts of novel microbial-derived compounds in lieu of animal models. |

| RNA-seq Reagents | For whole-transcriptome analysis of microbial gene expression under different perturbation states. | Identifying key stress response pathways activated in engineered strains during industrial fermentation. |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry for sensitive quantification of small molecules. | Measuring degradation of substrates (e.g., 2,4-D) and accumulation of toxic transformation products (e.g., 2,4-DCP) [7]. |

| Self-Selecting Vector Systems | Enables high-throughput, autonomous screening of optimal genetic constructs from massive libraries. | Rapidly testing thousands of expression-level combinations predicted by host-aware models [8]. |

In the field of industrial biotechnology, a fundamental challenge persists: the inherent conflict between engineering microbial cell factories for high-level production and maintaining their inherent cellular fitness. This trade-off arises because the very stresses that enable high product titers, yields, and productivity—such as metabolic burden, intermediate or end product toxicity, and harsh industrial conditions—often simultaneously compromise key cellular functions like growth, viability, and stability [1]. The concept of microbial robustness has thus emerged as a critical research focus. Robustness is defined as the ability of a strain to maintain stable production performance (titer, yield, productivity) despite various genetic, metabolic, or environmental perturbations encountered during scale-up bioprocesses [1]. It is crucial to distinguish robustness from mere tolerance; while tolerance describes the ability to grow or survive under stress, robustness specifically guarantees consistent production performance under those conditions [1]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on strategies to increase microbial cell factory robustness, analyzes this inevitable trade-off and provides detailed, actionable protocols to quantify, visualize, and mitigate it, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to design more resilient production systems.

Quantifying the Trade-off: Performance vs. Fitness Metrics

To systematically analyze the trade-off, it is essential to quantitatively monitor key performance indicators (KPIs) for both production and cellular fitness. The following metrics should be concurrently measured in engineered strains versus a baseline control (e.g., wild-type or non-producing strain) under standard and stress conditions.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Quantifying the Production-Fitness Trade-off

| Category | Metric | Description | Common Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production Performance | Maximum Theoretical Yield (Y_T) | The stoichiometric ceiling for converting a carbon source into a product [10]. | In silico calculation using Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) [10]. |

| Titer | The concentration of the target product achieved in the fermentation broth (e.g., g/L) [1]. | HPLC, GC-MS, spectrophotometric assays. | |

| Productivity | The rate of product formation (e.g., g/L/h) [1]. | Calculated from titer over time. | |

| Carbon Efficiency | The effectiveness of channeling carbon from substrate to product [10]. | Mass balance analysis, isotopic tracing. | |

| Cellular Fitness | Specific Growth Rate (μ) | The exponential growth rate (h⁻¹), a primary indicator of metabolic health [1]. | Optical density (OD) measurements over time. |

| Final Biomass Yield | The maximum cell density achieved (e.g., OD₆₀₀ or gDCW/L). | OD or dry cell weight (DCW) measurement. | |

| Cell Viability | The percentage of living cells in a population. | Flow cytometry with viability stains (e.g., propidium iodide). | |

| Metabolic Burden | The redirection of resources from growth to product synthesis and heterologous gene expression. | Comparative transcriptomics/proteomics, reduced growth rate [1]. |

The data collected in Table 1 can be visualized as a "Trade-off Profile," where a strong negative correlation between, for example, product titer and specific growth rate, provides clear evidence of the conflict. Strains with improved robustness will show a profile closer to the high-production, high-fitness quadrant.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Trade-off Analysis

Protocol 1: Cultivation and High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening

This protocol is designed to characterize the growth and production phenotypes of engineered strains under controlled conditions.

- Objective: To simultaneously measure microbial growth kinetics and product formation, identifying strains with superior robustness.

- Materials:

- Strains: Engineered production strain(s) and an appropriate control strain.

- Growth Media: Appropriate defined or complex medium (e.g., M9, LB) with required antibiotics.

- Equipment: Microplate reader capable of measuring OD and fluorescence (if applicable), deep-well plates, shaking incubator.

- Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Pick single colonies from fresh plates to inoculate 3-5 mL of pre-culture medium. Grow overnight at the required temperature (e.g., 30°C or 37°C) with shaking (e.g., 220 rpm).

- Main Culture Dilution: Dilute the pre-culture in fresh medium to a target initial OD₆₀₀ of ~0.05 in a deep-well plate. Use a minimum of 200 µL culture per well. Include blanks with sterile medium.

- Cultivation and Monitoring: Seal the plate with a breathable membrane and place it in the pre-heated microplate reader. Set the protocol for continuous shaking and measure the OD₆₀₀ every 15-30 minutes for 24-48 hours. Maintain constant temperature.

- Sampling: At the end of the exponential phase and upon entry into the stationary phase, extract samples from designated wells for:

- Product Titer Analysis: Centrifuge samples (e.g., 13,000 rpm for 5 min) and analyze the supernatant using HPLC, GC-MS, or other relevant assays.

- Cell Viability: Use samples for flow cytometry analysis with a live/dead stain (e.g., SYTO 9/propidium iodide).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the specific growth rate (μ) from the linear region of the ln(OD) vs. time plot.

- Determine the maximum OD (proxy for biomass).

- Calculate productivity based on titer and cultivation time.

Protocol 2: Assessing Membrane Integrity Under Product Stress

A robust cell factory must maintain membrane integrity under industrial stress. This protocol assesses membrane damage caused by toxic products or substrates.

- Objective: To evaluate the impact of production stress on cell membrane integrity and function.

- Materials:

- Strains: As in Protocol 1.

- Reagents: PBS buffer, propidium iodide (PI) solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL), fluorescent membrane dye (e.g., FM 4-64 or Nile Red), target product or stressor (e.g., ethanol, organic acid).

- Equipment: Flow cytometer or fluorescence microscope, microcentrifuge.

- Procedure:

- Stress Exposure: Grow cultures as in Protocol 1 to mid-exponential phase. Split the culture and add a sub-lethal concentration of the target stressor (e.g., 3% v/v ethanol for alcohol tolerance tests) to the test culture, while adding an equal volume of solvent/PBS to the control. Incubate for a further 1-2 hours.

- Staining:

- For viability/membrane integrity: Pellet 1 mL of culture (5,000 rpm, 5 min). Resuspend in 1 mL PBS. Add PI to a final concentration of 1-5 µg/mL. Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes [1].

- For membrane fluidity/order: Use a lipophilic dye like Nile Red or FM 4-64 according to manufacturer protocols.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze at least 10,000 events per sample. For PI staining, excite with a 488 nm laser and collect emission through a 610/20 nm bandpass filter. A shift in the PI-positive population indicates loss of membrane integrity.

- Microscopy: Visualize cells to confirm uniform staining and observe morphological changes.

- Data Interpretation: A robust strain will show a significantly lower percentage of PI-positive cells after stress exposure compared to a sensitive control, indicating superior membrane integrity preservation.

Visualization of Engineering Strategies and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core conflict and primary engineering strategies to enhance robustness.

The Core Conflict: Resource Competition

This diagram illustrates the fundamental trade-off where cellular resources are partitioned between native functions for fitness and engineered functions for production.

Multi-faceted Engineering for Robustness

This workflow outlines the key strategic pillars for engineering robust cell factories, moving beyond a single-gene approach.

Experimental Workflow for Robustness Engineering

This chart provides a practical roadmap for a research project aimed at identifying and developing more robust microbial cell factories.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Successful engineering of robust cell factories relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for the featured experiments and strategies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robustness Engineering

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application in Robustness Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Toolkits | CRISPR-Cas9 / CRISPRi systems [11] | Targeted gene knockout, knockdown (CRISPRi for essential genes like mreB or ftsZ in morphology engineering), and activation. |

| Plasmid vectors with inducible promoters | Controlled expression of heterologous pathways, transcription factors (e.g., IrrE, Haa1), or membrane desaturases (e.g., Ole1) [1]. | |

| Global Regulators & TFs | IrrE from Deinococcus radiodurans | A global transcription factor that, when expressed heterologously, can significantly enhance tolerance to solvents like ethanol and butanol in E. coli [1]. |

| Engineered sigma factor δ70 (rpoD) | Application in global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) to improve lycopene yield and tolerance to ethanol and SDS in E. coli [1]. | |

| Haa1 in S. cerevisiae | A specific transcription factor that activates acetic acid-responsive genes; engineering Haa1 improves acetic acid tolerance [1]. | |

| Membrane Engineering Enzymes | Δ9 desaturase (Ole1) from S. cerevisiae | Increases the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids (UFA/SFA) in the membrane, improving tolerance to ethanol, acid, and other stresses [1]. |

| cis–trans isomerase (Cti) | Incorporates trans-unsaturated fatty acids into the membrane, altering membrane fluidity and stress resistance [1]. | |

| Selection & Screening Markers | Fluorescent proteins (GFP, RFP) | Reporters for promoter activity, gene expression levels, and rapid screening of engineered libraries. |

| Viability stains (Propidium Iodide, SYTO 9) | Differentiate between live and dead cells for flow cytometry or microscopy, directly assessing cellular fitness under stress (Protocol 2). | |

| Computational Resources | Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | In silico prediction of metabolic capabilities, maximum theoretical yields, and identification of engineering targets for over 235 bio-based chemicals [10]. |

| AI/Machine Learning Platforms | Data-driven prediction of protein function, optimization of metabolic pathways, and design of non-natural synthesis routes to circumvent native toxic pathways [12]. |

In the development of microbial cell factories (MCFs), achieving high performance in controlled laboratory conditions is a significant first step, but ensuring consistent performance under industrial fermentation conditions is the ultimate challenge. Microbial robustness is defined as the ability of a strain to maintain constant production performance—defined as titer, yield, and productivity—despite various genetic, environmental, and process-related perturbations [1] [6] [2]. This concept goes beyond simple tolerance or resistance, which relates primarily to survival or growth under stress. Instead, robustness encompasses the stability of the production phenotype, making it a critical determinant of economic viability in scale-up bioprocesses [2].

This Application Note outlines the core Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) used to quantify robustness and provides detailed protocols for their experimental determination. By integrating these measurements with modern strain engineering strategies, researchers can systematically develop more reliable and efficient biomanufacturing platforms.

Defining the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

The performance of a microbial cell factory is quantitatively assessed using three primary metrics. Their behavior under fluctuating conditions provides a direct measure of robustness.

- Titer: The concentration of the target product in the fermentation broth, typically expressed in grams per liter (g/L). A high titer is crucial as it directly reduces downstream processing costs and energy consumption [13].

- Yield: The efficiency of substrate conversion into the desired product. It is calculated as the mass of product formed per mass of substrate consumed (g product/g substrate). High yield indicates minimal carbon loss to byproducts or biomass.

- Productivity: The rate of product formation, defined as the total product formed per unit volume per unit time (g/L/h). This metric determines the production capacity and directly influences bioreactor sizing and capital expenditure.

The stability of these three metrics—when a strain can maintain its target titer, yield, and productivity across different scales, in the presence of inhibitors, or under varying pH and temperature—is the definitive signature of a robust microbial cell factory [1] [6].

KPI Relationships and Impact on Bioprocess Economics

The table below summarizes the core KPIs, their calculation, and their specific impact on process economics.

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators for Microbial Cell Factories

| KPI | Definition | Unit | Significance for Process Economics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titer | Concentration of product in fermentation broth | g/L | High titer drastically reduces downstream separation and purification costs, water consumption, and environmental footprint [13]. |

| Yield | Mass of product formed per mass of substrate consumed | g product / g substrate | High yield maximizes raw material utilization, reduces feedstock costs, and minimizes waste generation. |

| Productivity | Amount of product formed per unit volume per unit time | g/L/h | High productivity increases bioreactor output, reducing capital expenditure (CAPEX) by requiring smaller reactors for the same annual production [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Determining KPIs and Robustness

Accurate and consistent measurement of titer, yield, and productivity is foundational to assessing robustness. The following protocols describe standardized methodologies for their determination.

Protocol: Quantifying Titer, Yield, and Productivity in Batch Fermentation

Objective: To determine the fundamental performance metrics of a microbial cell factory under standard batch fermentation conditions.

Materials:

- Strain: Engineered microbial strain (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae).

- Bioreactor: Bench-top fermenter with control for pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen.

- Analytical Instrumentation: HPLC system with appropriate detectors (UV, RID) or GC-MS for product quantification.

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Inoculate a single colony into a seed culture medium. Incubate until the culture reaches the mid-exponential growth phase.

- Fermentation: Transfer the seed culture to the bioreactor containing the production medium. Maintain optimal process parameters (e.g., pH, temperature, aeration) throughout the run.

- Sampling: Aseptically withdraw samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 2-4 hours) for analysis.

- Analysis:

- Cell Density: Measure optical density (OD600) to track growth.

- Substrate Concentration: Quantify substrate (e.g., glucose) depletion using HPLC or enzymatic assay kits.

- Product Titer: Quantify product concentration using a calibrated HPLC or GC-MS method.

- Calculations:

- Maximum Titer: The highest product concentration recorded, typically at the end of fermentation.

- Yield: (Maximum Titer (g/L)) / (Initial Substrate Concentration - Final Substrate Concentration (g/L)).

- Productivity: Maximum Titer (g/L) / Total Fermentation Time (h).

Protocol: Assessing KPI Stability for Robustness Evaluation

Objective: To evaluate the stability of titer, yield, and productivity under simulated industrial perturbation stresses.

Materials:

- Stress Conditions: Prepared stock solutions for pH adjustment, ethanol, butanol, or osmotic agents (e.g., NaCl).

- Multi-well Plates: 24-deep well plates for high-throughput screening.

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Prepare fermentation runs with controlled perturbations:

- Pulse Challenge: Introduce a single bolus of a stressor (e.g., 3% v/v ethanol) during the mid-exponential phase.

- Continuous Stress: Maintain a constant, sub-lethal level of stress throughout the fermentation (e.g., low pH or high osmolarity).

- Parallel Cultivation: Perform the controlled perturbation experiment in parallel with an unstressed control fermentation.

- Monitoring and Analysis: Sample and analyze all flasks/wells as described in Protocol 3.1 to determine titer, yield, and productivity under stress versus control conditions.

- Robustness Quantification:

- Calculate the % Performance Retention for each KPI:

% Retention = (KPI_stress / KPI_control) * 100 - A robust strain will exhibit high % retention across all three KPIs.

- Calculate the % Performance Retention for each KPI:

The logical workflow for designing and executing a robustness assessment is outlined below.

Strategies to Enhance Robustness and Stabilize KPIs

Several advanced metabolic engineering strategies directly target the stabilization of titer, yield, and productivity under industrial conditions.

Transcription Factor Engineering for Multi-Point Regulation

Engineering global transcription factors is a powerful method to reprogram cellular networks to be more resilient. Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) involves introducing mutations into generic transcription-related proteins (e.g., sigma factors in bacteria or TAFs in yeast) to alter the expression of numerous genes simultaneously [1] [6].

- Example: Engineering the housekeeping sigma factor δ70 (rpoD) in E. coli significantly improved tolerance to 60 g/L ethanol and high SDS concentrations, which was coupled with a high yield of lycopene [1] [6].

- Protocol: Create an error-prone PCR library of a global transcription factor gene (e.g., rpoD or spt15). Transform the library into the host strain and screen or select under the desired stress condition (e.g., high ethanol). Isolate mutants showing improved growth and validate for consistent KPI performance.

Membrane and Transporter Engineering

The cell membrane is the primary barrier against environmental stress. Engineering membrane composition enhances integrity and reduces permeability to inhibitory compounds [1].

- Example: Overexpression of Δ9 desaturase (OLE1) in S. cerevisiae increased the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids, improving tolerance to acid, NaCl, and ethanol [1].

- Protocol: Identify genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (e.g., fabA, fabB) or desaturation (e.g., OLE1). Overexpress or knock out these genes to modulate membrane fluidity. Assess robustness by measuring KPIs under solvent or acid stress.

Growth-Coupling Strategies

This strategy forces the cell to link product synthesis to growth, creating a strong selective pressure that stabilizes production and prevents loss-of-function mutations [14].

- Principle: By rewiring central metabolism, the synthesis of a precursor essential for growth is made dependent on the continued flux through the product synthesis pathway.

- Example: An E. coli strain was engineered for anthranilate production by disrupting native pyruvate-producing genes and expressing a feedback-resistant anthranilate synthase. This design coupled anthranilate production with pyruvate regeneration, essential for growth, leading to a 2-fold increase in product titers [14].

The diagram below illustrates the conceptual difference between a standard production pathway and a growth-coupled design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and materials required for implementing the protocols and strategies described in this note.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robustness Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Generation of mutant libraries for directed evolution. | Creating diversity in transcription factor genes for gTME [1]. |

| HPLC/GC-MS System | Quantitative analysis of substrate, product, and byproducts. | Precisely measuring titer and yield from fermentation samples [13]. |

| 24/48 Deep Well Plates | High-throughput cultivation under multiple conditions. | Parallel screening of strain libraries against various stress perturbations. |

| Stressors (e.g., Ethanol, Butanol, Organic Acids) | Simulating industrial fermentation stresses in lab-scale experiments. | Assessing KPI stability under product toxicity [1] [6]. |

| Plasmid Vectors for Overexpression | Delivering and expressing genes for membrane or pathway engineering. | Overexpressing OLE1 to alter membrane lipid composition [1]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing System | Performing precise gene knock-outs, knock-ins, and edits. | Disrupting competing pathways or implementing growth-coupling designs [14]. |

Synthetic Biology and Metabolic Engineering Tools for Building Robust Hosts

Global Transcription Machinery Engineering (gTME) is an advanced metabolic engineering strategy that enhances microbial cell factory robustness by reprogramming cellular regulation at the transcriptional level. This approach involves engineering components of the global transcription machinery to elicit multigenic, complex phenotypes that are not readily accessible through traditional single-gene modifications [15]. In industrial bioprocessing, microbial cells constantly face perturbations from metabolic burden, pathway toxicity, and harsh environmental conditions, leading to decreased productivity and titer [1]. Strain robustness—the ability to maintain stable production performance despite these disturbances—is essential for reliable and sustainable bioproduction efficiency [1] [16]. gTME provides a powerful route to enhance this robustness by simultaneously modulating multiple cellular networks, enabling improved tolerance to industrial stresses while maintaining or even enhancing production capabilities [17] [15].

The fundamental principle of gTME centers on creating mutant libraries of transcription-related proteins, then screening for dominant mutant alleles that confer desired phenotypes such as improved product tolerance, substrate utilization, or environmental resistance [15]. This strategy moves beyond traditional pathway engineering by targeting the regulatory architecture that controls diverse cellular processes, thereby enabling coordinated optimization of complex traits that involve multiple genes and pathways [17].

Theoretical Foundation and Key Mechanisms

Core Principles of gTME

gTME operates on the premise that global transcription factors serve as master regulators controlling numerous cellular processes through hierarchical regulatory networks. In typical microbial systems, a relatively small number of global regulatory factors control large proportions of the genome. For instance, in E. coli, seven well-characterized global regulatory factors (CRP, IHF, FNR, ArcA, FIS, Lrp, and NarL) control over 50% of all genes [1]. By engineering these central regulators, gTME enables comprehensive reprogramming of gene expression patterns that can simultaneously address multiple limitations in industrial strains.

The strategy leverages the phenomenon that dominant mutations in global transcription factors can trigger widespread but coordinated changes in transcriptional networks, resulting in unique cellular phenotypes that would be difficult to achieve through sequential modification of individual genes [15]. This "multi-point regulation" provides a unique advantage for engineering complex traits where multiple cellular processes must be optimized in concert, such as balancing growth and production or coordinating stress response with metabolic flux [1].

Molecular Targets for gTME

Different microorganisms offer distinct targets for gTME implementation:

- In prokaryotic systems (e.g., E. coli): Engineering of sigma factors (σ70) and global regulators like CRP and IrrE

- In eukaryotic systems (e.g., S. cerevisiae): Engineering of TATA-binding protein Spt15 and transcription factor Taf25

- In unconventional hosts: Application in Yarrowia lipolytica, Lactobacillus plantarum, Rhodococcus ruber, and Zymomonas mobilis [17] [1]

The selection of appropriate targets depends on the host organism, desired phenotype, and understanding of the transcriptional regulatory network architecture. Successful implementation requires identification of transcription factors with broad regulatory influence that can be engineered to produce beneficial phenotypic changes without catastrophic fitness costs.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General gTME Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core gTME implementation workflow:

Detailed Protocol: gTME Implementation inS. cerevisiaevia Spt15 Engineering

Objective: Enhance ethanol tolerance and production in S. cerevisiae through Spt15 mutagenesis.

Materials and Reagents:

- S. cerevisiae strain (e.g., YPH499)

- Plasmid vector (e.g., pYX212)

- Primers for SPT15 gene amplification

- Error-prone PCR kit

- Transformation reagents

- Selection media (appropriate auxotrophic selection)

- Screening media with stressor (e.g., ethanol)

- Analytical equipment (HPLC, GC-MS for product quantification)

Procedure:

Library Generation:

- Amplify the SPT15 gene using error-prone PCR conditions optimized to achieve 1-3 mutations per kilobase [18] [15].

- Clone the mutated SPT15 genes into an appropriate expression vector under control of a constitutive promoter.

- Transform the mutant library into S. cerevisiae and plate on selective media to obtain approximately 10⁴-10⁵ independent transformants.

Selection and Screening:

- For improved ethanol tolerance: Screen transformants on solid media containing 4-6% (v/v) ethanol [18].

- For enhanced production: Employ product-specific screening assays or selection systems.

- For complex phenotypes: Use actual industrial substrates (e.g., corn cob hydrolysate) as sole carbon source [19].

- Isulate promising clones showing improved growth or production under selective conditions.

Validation and Characterization:

- Sequence mutated genes from selected clones to identify beneficial mutations.

- Characterize phenotypic improvements in batch fermentations under industrial-relevant conditions.

- Analyze transcriptomic profiles to understand regulatory reprogramming.

- Implement iterative cycles of mutagenesis and screening for additional improvements.

Key Parameters for Success:

- Library diversity and size

- Selection pressure stringency

- Screening methodology throughput and relevance

- Analytical methods for phenotype validation

Protocol Variations for Different Hosts

For E. coli:

- Target sigma factor σ70 (rpoD gene) or cAMP receptor protein (CRP)

- Screen for tolerance to biofuels (ethanol, butanol) or organic acids [1]

- Use stress-inducing compounds (e.g., SDS) as additional selection pressure

For Yarrowia lipolytica:

- Identify and target global transcription factors specific to oleaginous yeast

- Screen for improved lipid production or utilization of alternative carbon sources [17]

- Leverage well-developed culturing and analytical protocols for phenotype characterization

Applications and Performance Data

Quantitative Outcomes of gTME Implementation

Table 1: Documented Performance Improvements Achieved through gTME

| Host Organism | Engineering Target | Selection Pressure | Key Mutations | Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | Spt15 | 6% (v/v) ethanol | F177S, Y195H, K218R | Improved ethanol tolerance and production; more efficient glucose conversion to ethanol | [18] |

| S. cerevisiae | Spt15 | Corn cob acid hydrolysate | Not specified | 65.7% xylose utilization, 87.0% glucose utilization, 11.9 g/L ethanol production | [19] |

| E. coli | σ70 (rpoD) | 60 g/L ethanol, SDS | Not specified | Improved tolerance to ethanol and SDS; increased lycopene yield | [1] |

| E. coli | IrrE (from D. radiodurans) | Ethanol/butanol stress | Not specified | 10-100× improved tolerance to ethanol or butanol stress | [1] |

Application Spectrum for Robustness Enhancement

Table 2: gTME Applications for Enhancing Microbial Cell Factory Robustness

| Application Domain | Targeted Robustness Aspect | Representative Hosts | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofuel production | Ethanol tolerance, inhibitor resistance | S. cerevisiae, Z. mobilis, E. coli | Improved growth and production under high ethanol conditions; enhanced utilization of lignocellulosic hydrolysates |

| Organic acid production | Low pH tolerance, end-product resistance | E. coli, Y. lipolytica, C. glutamicum | Enhanced acid tolerance enabling higher titers in non-neutralized conditions |

| Bioprocess optimization | Thermal stability, osmotic tolerance | Various industrial hosts | Improved performance under industrial-scale fermentation conditions |

| Metabolic pathway engineering | Metabolic burden tolerance, redox balancing | S. cerevisiae, E. coli | Enhanced cofactor balancing and reduced metabolic burden from heterologous pathways |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for gTME Implementation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in gTME | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis Methods | Error-prone PCR, Site-saturation mutagenesis | Introduce diversity into transcription factor genes | Optimize mutation rate to balance functional variants and protein integrity |

| Vector Systems | Plasmid-based expression, Genomic integration | Deliver mutant transcription factor genes | Consider copy number and expression level effects |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, Auxotrophic complementation | Maintain genetic constructs in population | Antibiotic-free systems preferred for industrial applications |

| Screening Assays | Growth-based selection, Biosensors, FACS | Identify clones with desired phenotypes | Throughput and relevance critical for success |

| Analytical Tools | RNA-seq, HPLC/GC-MS, Growth phenotyping | Characterize transcriptional and phenotypic changes | Multi-omics provides mechanistic insights |

| Host Strains | S. cerevisiae, E. coli, Y. lipolytica | Chassis for gTME implementation | Choose based on industrial application and genetic toolbox availability |

Integration with Broader Robustness Engineering Strategies

gTME functions most effectively when integrated with complementary robustness enhancement strategies. The relationship between gTME and other approaches can be visualized as follows:

Synergistic Approaches

- Membrane/Transporter Engineering: While gTME addresses transcriptional reprogramming, simultaneous engineering of membrane composition and transporter systems can enhance tolerance to hydrophobic inhibitors and organic solvents [1].

- Dynamic Pathway Regulation: gTME can be combined with biosensor-enabled dynamic control to autonomously manage metabolic fluxes, reducing burden and improving stability [16].

- Genetic Stability Enhancement: Integration with toxin-antitoxin systems or auxotrophy complementation strategies maintains gTME benefits over extended cultivation periods [16].

gTME represents a powerful paradigm for enhancing microbial cell factory robustness by reprogramming global cellular regulation. The methodology has demonstrated repeated success in improving complex, industrially relevant phenotypes across diverse microbial hosts. Its key advantage lies in enabling coordinated optimization of multiple cellular functions through minimal genetic interventions, making it particularly valuable for engineering traits that involve complex genetic determinants.

Future developments in gTME will likely focus on several key areas:

- Integration with computational and systems biology approaches for predictive design

- Expansion to non-conventional microbial hosts with industrial relevance

- Combination with CRISPR-based screening for more efficient library evaluation

- Application to emerging bioproduction challenges, including novel product toxicity and alternative substrate utilization

As the field advances, gTME is poised to remain a cornerstone strategy in the robustness engineering toolkit, enabling more resilient and efficient microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction.

In the pursuit of sustainable biomanufacturing, microbial cell factories (MCFs) have emerged as powerful platforms for producing fuels, natural products, and pharmaceuticals. However, their industrial potential is often hampered by various stresses encountered during fermentation, including metabolic burden, product toxicity, and harsh environmental conditions. These challenges can severely compromise production efficiency and strain stability. Microbial robustness—the ability of a strain to maintain stable production performance despite perturbations—has thus become a critical engineering target for viable bioprocesses [1] [2]. Unlike tolerance, which primarily relates to survival or growth under stress, robustness encompasses the stability of key production metrics (titer, yield, productivity) under variable industrial conditions [6].

Among the various strategies to enhance robustness, membrane and transporter engineering represents a frontline defense mechanism. The cell membrane serves as the primary interface between the cell and its environment, mediating material transport, energy exchange, and environmental sensing. By engineering membrane composition, structure, and transport systems, researchers can significantly improve cellular resilience and production capacity, thereby fortifying MCFs against industrial stresses [1] [20].

Application Notes: Strategic Implementation of Membrane and Transporter Engineering

Membrane Lipid Composition Engineering

Engineering membrane lipid composition directly influences membrane fluidity, integrity, and functionality under stress conditions. Strategic modifications can enhance tolerance to various inhibitors and products.

Table 1: Membrane Lipid Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Robustness

| Engineering Strategy | Host Organism | Key Modification | Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsaturated Fatty Acid (UFA) Regulation | E. coli | Overexpression of fabA and fabB via CpxRA system | Growth at pH 4.2; Increased UFA content | [1] |

| Fatty Acid Desaturation | S. cerevisiae | Overexpression of Δ9 desaturase OLE1 | Improved tolerance to acid, NaCl, and ethanol | [1] |

| Cyclopropane Fatty Acid (CFA) Enhancement | E. coli | Overexpression of cfa gene from E. faecalis | Increased CFA content; Improved butanol tolerance | [20] |

| cis-trans Isomerization | E. coli | Overexpression of cti from P. aeruginosa | Enhanced membrane rigidity; Increased octanoic acid production | [20] |

| Fatty Acid Elongation | S. cerevisiae | Overexpression of rat elongase 2 (rELO2) | Increased oleic acid; Tolerance to ethanol, n-propanol, n-butanol | [1] |

Transporter Engineering for Product Efflux and Sequestration

Transporters facilitate the movement of molecules across cellular membranes, playing a pivotal role in mitigating intracellular product accumulation and toxicity. Engineering specific transporters can significantly enhance production by enabling efficient product efflux or vacuolar sequestration.

Table 2: Transporter Engineering for Plant Natural Product (PNP) Biosynthesis

| Transporter Type/Name | Origin | Localization | Function/Substrate | Application in MCFs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC Transporters | |||||

| - AtPGP1 | A. thaliana | Plasma membrane | Auxin transport | Model for transporter discovery | [21] |

| - CrTPT2 | C. roseus | - | Catharanthine transport | Anticancer drug precursor production | [21] |

| - AaPDR3 | A. annua | - | β-Caryophyllene transport | Sesquiterpene production | [21] |

| MATE Transporters | |||||

| - NtMATE1 | N. tabacum | Vacuolar membrane (root-specific) | Alkaloid transport to vacuoles | Detoxification and storage | [21] |

| - NtJAT2 | N. tabacum | Vacuolar membrane (leaf-specific) | Nicotine transport | Tissue-specific transport models | [21] |

| - CjMATE1 | C. japonica | Vacuolar membrane | Berberine transport | Alkaloid accumulation | [21] |

Diagram 1: Integrated cellular engineering strategy for enhanced robustness. The diagram illustrates how microbial cells sense external stress and the subsequent engineering interventions targeting membrane properties and transporter functions to achieve enhanced robustness.

Intracellular Membrane Proliferation for Storage Capacity

Many hydrophobic natural products (e.g., terpenoids, carotenoids) accumulate in membrane structures, creating a bottleneck due to limited space. Engineering strategies that promote intracellular membrane proliferation can dramatically increase storage capacity and boost production titers.

- Key Example: Overexpression of the heterologous enzyme 1,2-diacylglycerol 3-glucosyltransferase from Acholeplasma laidlawii (AlMGS) in E. coli induces the formation of numerous intracellular membrane vesicles, effectively expanding the membrane area available for product storage [20]. This strategy has been successfully applied to increase the production of compounds like beta-carotene and lycopene.

- Synergistic Approach: Combining AlMGS overexpression with the reinforcement of the endogenous membrane synthesis pathway (e.g., by overexpressing plsB and plsC) creates a powerful synergy for membrane proliferation and has led to significant increases in lycopene production [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Engineering Membrane Fluidity via Fatty Acid Composition inE. coli

This protocol details the genetic modification of E. coli to alter its unsaturated to saturated fatty acid (UFA/SFA) ratio, a key determinant of membrane fluidity and stress tolerance [1] [20].

I. Materials

- E. coli target strain (e.g., MG1655)

- Plasmid vector with inducible promoter (e.g., pET, pBAD)

- Genomic DNA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (for cti gene)

- Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase

- DpnI restriction enzyme

- T4 DNA Ligase

- Chemically competent E. coli cells

- LB broth and agar plates with appropriate antibiotics

- Inducer (e.g., IPTG or L-Arabinose)

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) system for fatty acid analysis

II. Procedure

Day 1: Gene Cloning

- Amplify Target Gene: Use PCR to amplify the cis-trans isomerase gene (cti) from P. aeruginosa genomic DNA.

- Digest Vector and Insert: Digest the plasmid vector and the purified cti PCR product with the appropriate restriction enzymes.

- Ligate and Transform: Ligate the cti insert into the digested vector and transform into competent E. coli cells. Plate on selective LB agar and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Day 2: Colony Screening and Cultivation

- Screen Colonies: Pick several colonies, inoculate in small volumes of selective LB broth, and grow for 6-8 hours.

- Verify Clone: Isolate plasmid DNA from cultures and verify correct construction by restriction digest and/or sequencing.

- Start Overnight Culture: Inoculate a verified colony into fresh selective LB broth and incubate overnight with shaking.

Day 3: Induction and Analysis

- Sub-culture: Dilute the overnight culture into fresh, pre-warmed medium containing antibiotics.

- Induce Gene Expression: When the culture reaches mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.6), add the inducer.

- Harvest Cells: 4-6 hours post-induction, harvest cells by centrifugation.

- Analyze Membrane Lipids: a. Lipid Extraction: Perform a Bligh and Dyer lipid extraction on the cell pellet. b. Fatty Acid Methylation: Derivatize fatty acids to their methyl esters (FAMEs). c. GC-MS Analysis: Analyze FAMEs by GC-MS to determine the UFA/SFA ratio and the presence of trans-UFAs.

- Phenotypic Assay: Assess tolerance by comparing the growth of the engineered strain versus the control in media containing stress agents (e.g., ethanol, butanol, organic acids).

Protocol: Functional Screening of Plant ABC Transporters in Yeast

This protocol describes a heterologous system to screen for plant-derived ABC transporters that can export hydrophobic plant natural products (PNPs) from yeast, alleviating intracellular toxicity [21].

I. Materials

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain (e.g., BY4741)

- Yeast expression plasmid (e.g., pYES2/CT)

- cDNA library from a plant of interest (e.g., Catharanthus roseus)

- SC-Ura broth and agar plates

- Galactose and Raffinose

- Target PNP (e.g., catharanthine, β-caryophyllene)

- LC-MS/MS system for product quantification

II. Procedure

Day 1: Library Transformation

- Prepare Competent Yeast Cells: Use a lithium acetate method to make competent yeast cells.

- Co-transform: Co-transform the yeast with the plant cDNA library cloned into the expression vector and a plasmid containing the PNP biosynthetic pathway.

- Plate and Incubate: Plate the transformation mixture on SC-Ura dropout plates and incubate at 30°C for 2-3 days.

Day 2-4: Functional Screen

- Replica Plating: Replica plate the colonies onto fresh SC-Ura plates containing galactose (to induce transporter expression) and a growth-inhibiting concentration of the target PNP or its precursor.

- Identify Resistant Clones: Identify colonies that grow robustly under selective conditions but show slow growth on control plates without induction.

- Isolate Plasmids: Recover the plasmid from the candidate yeast clones and retransform into fresh yeast to confirm the phenotype.

Day 5: Validation

- Fed-Batch Fermentation: Grow validated strains in selective medium with galactose induction.

- Sample Analysis: Collect cells and media at various time points.

- Quantify Product: Use LC-MS/MS to quantify intracellular vs. extracellular concentrations of the target PNP. A successful transporter will show a higher proportion of the product in the extracellular medium compared to control strains.

Diagram 2: Generalized workflow for transporter and membrane engineering. The flowchart outlines the key experimental steps from gene cloning to phenotypic and chemical validation of engineered microbial strains.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Membrane and Transporter Engineering Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlMGS (A. laidlawii MGS) | Heterologous enzyme inducing intracellular membrane proliferation. | Expanding membrane storage capacity in E. coli for carotenoid production. | [20] |

| Cis-trans Isomerase (Cti) | Converts membrane UFAs from cis to trans, increasing rigidity. | Enhancing E. coli tolerance to octanoic acid and various physical/chemical stresses. | [20] |

| Δ9 Desaturase (OLE1) | Introduces double bonds in fatty acids, increasing UFA/SFA ratio. | Improving yeast tolerance to multiple stressors (ethanol, acid, NaCl). | [1] |

| Synthetic Lipids (e.g., alkynyl DPPC) | Building artificial membranes (protocells) with engineered sensing capabilities. | Creating model vesicle systems to study membrane behavior and redox sensing. | [22] |

| cfa Gene (CFA Synthase) | Synthesizes cyclopropane fatty acids for membrane lipid homeostasis. | Improving acid and solvent tolerance in engineered E. coli strains. | [20] |

| Plant ABC Transporter Genes (e.g., CrTPT2, AaPDR3) | Facilitates specific transport of plant natural products (PNPs). | Enabling efflux or sequestration of toxic PNPs in heterologous microbial hosts. | [21] |

The establishment of robust microbial cell factories is often hampered by the inherent conflict between host cell fitness and the metabolic burden imposed by heterologous pathways. Static metabolic engineering approaches frequently lead to suboptimal production performance due to unbalanced enzyme expression, metabolic congestion, and the accumulation of toxic intermediates [23]. Dynamic metabolic control has emerged as a transformative strategy to overcome these challenges by enabling autonomous regulation of metabolic pathways in response to changing intracellular conditions [23] [24].

This application note explores the integration of biosensors and quorum sensing (QS) systems as sophisticated tools for implementing dynamic control strategies. These systems enable microbial cell factories to self-regulate metabolic flux, automatically divert resources from growth to production phases, and maintain cellular homeostasis without external intervention. By framing these technologies within the context of enhancing microbial robustness, we provide detailed protocols and implementation frameworks that support the development of more reliable and productive biomanufacturing platforms.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Components

Molecular Principles of Autonomous Regulation

Autonomous dynamic regulation systems mimic the "just-in-time transcription" principles prevalent in natural metabolic networks [23]. These systems typically comprise three core components: a sensing mechanism that detects specific intracellular or extracellular signals, a processing module that interprets these signals, and an output module that executes appropriate metabolic responses.

Biosensors function as the critical sensing elements, converting biological signals into quantifiable genetic responses. The input module employs transcription factors, membrane receptors, aptamers, or nucleic acid switches to capture external stimuli such as metabolic intermediates, pH, or temperature changes [25]. Following target recognition, sensing elements activate signal transduction through conformational changes, induced dimerization, conditional stabilization, or enzymatic reactions [25].

Quorum sensing systems provide unique population-density-dependent control mechanisms. In these systems, autoinducer molecules accumulate proportionally with cell density, activating transcriptional regulators once a threshold concentration is reached. This enables coordinated population-wide responses, making QS particularly valuable for implementing two-stage fermentation processes where production is initiated only after sufficient biomass accumulation [26] [24].

Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Regulation Strategies

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Dynamic Control Modalities

| Control Strategy | Induction Mechanism | Key Advantages | Implementation Challenges | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inducers | External addition of small molecules (e.g., IPTG, aTc) | Precise temporal control; well-characterized systems | Cost at industrial scale; potential toxicity; requires fermentation intervention | Two-phase production of malate, isoprenol, and glucaric acid [23] |

| Quorum Sensing | Autoinducer accumulation at high cell density | Autonomous induction; pathway-independent; no external inducers needed | Circuit crosstalk; dependent on population dynamics; tuning required | MK-7 production in B. subtilis; iso-butylamine production in E. coli [26] [27] |

| Biosensor-Based | Detection of specific metabolites or intracellular conditions | Real-time feedback control; responsive to metabolic state | Limited metabolite detection range; potential background interference | Lycopene, N-acetylglucosamine, and shikimate production [23] |

| Environmental Triggers | Changes in temperature, pH, or light | Non-chemical induction; potentially low-cost | Indirect control; can affect multiple cellular processes simultaneously | Light-induced isobutanol production; pH-controlled lactic acid synthesis [23] |

Application Case Studies in Metabolic Engineering

Quorum Sensing for Enhanced Menaquinone Biosynthesis

The SinR quorum sensing regulator in Bacillus subtilis was engineered through site-directed mutagenesis to dynamically control menaquinone (MK-7) production. The mutant SinRquad strain achieved a remarkable yield of 102.56 ± 2.84 mg/L MK-7, representing one of the highest reported titers [26].

Mechanistic Analysis: RNA-seq transcriptome profiling revealed that SinRquad upregulated biofilm formation genes (tapA, tasA, epsE), resulting in structural modifications that enhanced glycerol uptake efficiency. Concurrently, increased expression of NADH dehydrogenases (sdhA, sdhB, sdhC, glpD) generated elevated membrane potential, stimulating electron transport chain components including menaquinone [26].

This QS-mediated approach demonstrated how autonomous regulation could simultaneously optimize physical cell properties and metabolic flux without compromising cell viability. The wrinkly, smooth biofilms formed interconnected channels with low resistance to liquid flow, facilitating nutrient distribution and product formation.

Biosensor-Driven Dynamic Control Applications

Biosensors have enabled diverse dynamic control applications across multiple microbial hosts and pathway types:

- Acetyl phosphate-responsive control in E. coli enhanced lycopene productivity 3-fold by implementing positive feedback regulation of the PPS and Idi enzymes [23].