Engineering Yeast Cell Factories: A Comprehensive Guide to Heterologous Pathway Expression for Drug Development

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for harnessing yeast cell factories for heterologous pathway expression.

Engineering Yeast Cell Factories: A Comprehensive Guide to Heterologous Pathway Expression for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for harnessing yeast cell factories for heterologous pathway expression. It explores the foundational principles of yeast host systems, details advanced methodological tools for pathway engineering, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers validation strategies for comparative analysis. By integrating the latest research on promoter engineering, cellular lifespan extension, and multi-omics validation, this guide serves as a critical resource for advancing the production of therapeutic compounds, including complex plant-derived natural products and membrane proteins, in yeast-based platforms.

Yeast Host Systems and Expression Fundamentals: Building Your Genetic Toolbox

Comparative Advantages of Yeast Systems for Eukaryotic Protein Production

The development of efficient and robust systems for eukaryotic protein production is a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, supporting the manufacture of biologics, industrial enzymes, and research reagents. Among available platforms, yeast-based expression systems offer a powerful combination of eukaryotic processing capabilities, rapid growth, and scalability. This application note delineates the comparative advantages of major yeast expression systems within the context of heterologous pathway expression in yeast cell factories. We provide a structured quantitative comparison, detailed experimental methodologies for core protocols, and visualization of critical pathways to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal yeast platform for their specific protein production needs.

Comparative Analysis of Major Yeast Expression Systems

The selection of an appropriate yeast host is critical for the successful production of a recombinant eukaryotic protein. The most commonly utilized systems each possess distinct profiles of advantages and limitations, making them suited to different applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Yeast Production Systems

| Feature | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Komagataella phaffii | Ogataea polymorpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Application | Traditional cell factory; well-studied model organism [1] | High-yield production of biopharmaceuticals and industrial enzymes [2] | Production of therapeutics and antivirals; thermotolerant processes [2] |

| Key Strength | Extensive genetic tools; GRAS status; rapid growth [3] [1] | Very high cell-density fermentation; strong, regulated promoters; superior secretion [2] | Thermotolerance (30-50°C); low hyper-mannosylation; multi-carbon source use [2] |

| Promoter Example | GAL1, GAL10 [3] | Methanol-inducible AOX1 [3] [2] | Methanol-inducible promoters [2] |

| Post-Translational Modification | Hyper-mannosylation of N-glycans can occur | Capable of human-like glycosylation patterns [4] | Human-like glycoproteins; relatively low hyper-mannosylation [2] |

| Genetic Engineering | Highly advanced (CRISPR, synthetic biology) [1] [5] | Advanced (CRISPR/Cas9 available) [2] | Well-developed genetic tools [2] |

| Regulatory Status | GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) [3] | GRAS status for specific products [2] | GRAS status [2] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Yeast Systems

| Metric | S. cerevisiae | K. phaffii | O. polymorpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Temperature Range | 28-30°C (typical) | 28-30°C | 30-50°C [2] |

| Fermentation Cell Density | High | Very High [2] | High [2] |

| Representative Protein Yield | Moderate | High (e.g., >g/L scale reported) [2] | High [2] |

| Market Impact (Cell Wall Extract Market 2021) | ~$2.09 Billion (as part of global market) [6] | Significant (as a key contributor) | Growing |

The data above demonstrate that while S. cerevisiae remains a versatile and genetically tractable workhorse, methylotrophic yeasts like K. phaffii and O. polymorpha offer distinct advantages for demanding industrial applications, particularly where high cell density, strict promoter regulation, or thermotolerance are required.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Basic Protocol 1: Target Optimization and Construct Design

The initial bioinformatic analysis of the target protein is crucial for maximizing the likelihood of high expression and solubility [7]. This protocol outlines a computational workflow for target optimization prior to gene synthesis.

Materials & Reagents

- Hardware: Computer with internet access.

- Software: NCBI BLAST, ColabFold (AlphaFold2 server), XtalPred.

- Files: Target protein sequence(s) in FASTA format.

Procedure

- pBLAST against PDB Database: Navigate to the NCBI BLAST website. Select "Protein BLAST" and input your target protein sequence in FASTA format. Set the database to "Protein Data Bank proteins (pdb)" and select the "PSI-BLAST" algorithm. Run the search using default parameters. Identify homologous structures with ≥40% sequence identity and 75-80% query coverage. Use these alignments to inform the design of your expression construct, prioritizing domains from homologs with high query coverage [7].

- Modeling with AlphaFold: For targets lacking close PDB homologs, use the ColabFold: AlphaFold2 server. Input the target sequence and run the analysis with default parameters. The tool will generate five models, with each residue colored by its predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) score. A high pLDDT score indicates confidence in the local structure prediction. Use this model to identify and potentially exclude poorly structured, disordered regions from your final construct to enhance the probability of soluble expression [7].

- Codon Optimization: Upon finalizing the target protein sequence, utilize commercial gene synthesis services that offer host-specific codon optimization (e.g., for K. phaffii or S. cerevisiae). This step is critical for maximizing translational efficiency and protein yield [7].

Basic Protocol 2: High-Throughput Transformation and Screening

This protocol describes a high-throughput (HTP) method for transforming and screening multiple expression constructs in a 96-well format, adapted from established pipelines [7].

Materials & Reagents

- Expression Vectors: Codon-optimized, synthetically derived genes cloned into an appropriate yeast expression vector (e.g., pMCSG53 for E. coli, or a methanol-inducible vector for K. phaffii).

- Yeast Strains: Chemically competent cells of your chosen yeast system (e.g., S. cerevisiae, K. phaffii).

- Media: Appropriate selective medium (e.g., SD -Ura for S. cerevisiae).

- Equipment: 96-well deep-well plates, microplate shaker incubator, liquid handling robot (optional, for automation).

Procedure

- Transformation: In a 96-well plate, transform the expression constructs into your competent yeast strain using a high-efficiency protocol (e.g., lithium acetate method for S. cerevisiae). Plate the transformation mixtures onto solid selective medium and incubate until colonies form [7].

- Inoculation and Growth: Pick individual colonies into a 96-deep-well plate containing liquid selective medium. Seal the plate with a breathable seal and incubate with shaking (e.g., 220 rpm) at the standard growth temperature (e.g., 30°C) until the cultures reach mid-log phase.

- Protein Expression Induction: For inducible systems like AOX1 in K. phaffii, add the inducer (e.g., methanol to a final concentration of 0.5-1%) to the culture. For S. cerevisiae GAL promoters, induce by adding galactose. Continue incubation with shaking for a defined period (e.g., 24-48 hours) [7].

- Solubility Screening: Harvest cells by centrifugation. Lyse the cell pellets using chemical lysis or enzymatic digestion (e.g., lyticase). Centrifuge the lysates to separate soluble and insoluble fractions. Analyze the soluble fraction for the presence of the target protein, typically via SDS-PAGE or western blot [7].

Basic Protocol 3: Engineering Robust Yeast Cell Factories

Enhancing the cellular robustness of yeast can significantly extend its operational lifespan and improve recombinant protein yield under industrial fermentation conditions [5]. This protocol outlines a genetic strategy to improve chronological lifespan.

Materials & Reagents

- Strains & Plasmids: S. cerevisiae background strain, CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid system, donor DNA for gene editing.

- Media: YPD medium, synthetic dropout media as needed.

- Molecular Biology Reagents: DNA polymerases, restriction enzymes, cloning kits, primers.

Procedure

- Genetic Modifications: To enhance robustness, engineer the yeast chassis by:

- Downregulating TOR1: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to replace the native promoter of the TOR1 gene with a weaker promoter to downregulate its expression.

- Deleting HDA1: Design a gRNA and a donor DNA template to completely knock out the histone deacetylase gene HDA1 [5].

- Strain Validation: Transform the genetic constructs into the host yeast strain. Select positive clones and verify the genetic modifications via PCR and DNA sequencing.

- Phenotypic Analysis:

- Chronological Lifespan (CLS) Assay: Measure the viability of the engineered strains over time in stationary phase culture compared to the wild-type control. The robust strains should show a significantly extended CLS [5].

- Production Assay: Cultivate the validated strains in shake-flask batch fermentations and measure the titer of the target product (e.g., fatty alcohols, a recombinant protein). Successful engineering should result in a substantial increase in yield (e.g., up to 56% for fatty alcohols) [5].

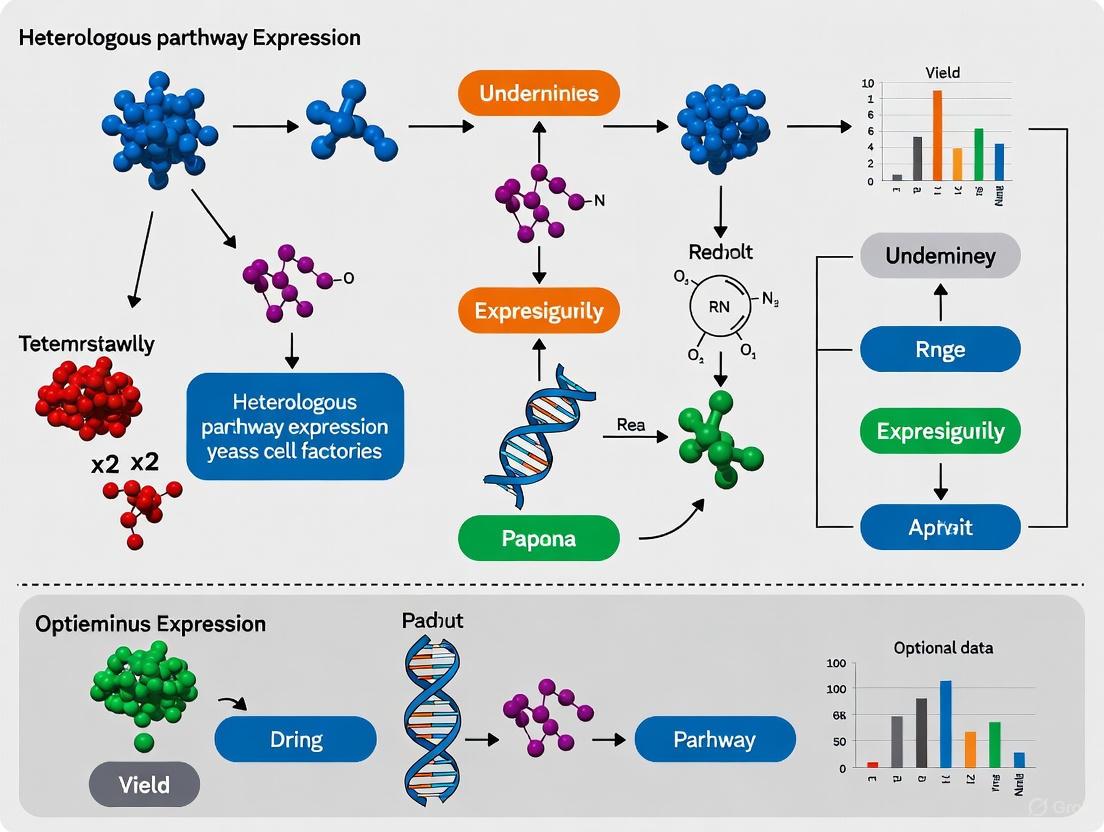

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Methanol Induction Pathway in Methylotrophic Yeast

The high productivity of methylotrophic yeast systems is driven by the tightly regulated methanol utilization pathway. The following diagram illustrates the core logic of gene induction, centered on the AOX1 promoter, which is a key tool for recombinant protein production.

High-Throughput Protein Screening Pipeline

The integration of bioinformatic design with high-throughput experimental screening creates an efficient pipeline for identifying successful expression constructs, as summarized in the workflow below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Yeast Protein Production

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol-Inducible Promoters (e.g., AOX1) | Strong, tightly regulated promoter for high-level expression in methylotrophic yeasts [2]. | Inducing recombinant protein expression in Komagataella phaffii by adding methanol to the culture medium [2]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precision genome editing for strain engineering (e.g., gene knock-outs, promoter swaps) [2] [5]. | Knocking out the HDA1 gene in S. cerevisiae to enhance cellular robustness and extend chronological lifespan [5]. |

| Bioinformatics Software (BLAST, ColabFold) | Computational analysis of target proteins to predict structure, identify domains, and optimize construct design [7]. | Identifying and truncating intrinsically disordered regions of a target protein to improve its solubility during recombinant expression [7]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Systems | Automated liquid handling and analysis for parallel testing of many constructs or conditions in microplates [7]. | Rapidly screening hundreds of different protein constructs for solubility and expression level in a 96-well format [7]. |

| Synthetic DNA & Cloning Services | Provides codon-optimized, sequence-verified genes cloned into expression vectors, accelerating the construct generation process [7]. | Sourcing a library of codon-optimized genes for a structural genomics project, delivered pre-cloned in an expression vector [7]. |

| 1-(3-Nitrophenyl)-2-nitropropene | 1-(3-Nitrophenyl)-2-nitropropene|CAS 134538-50-4 | High-purity 1-(3-Nitrophenyl)-2-nitropropene, a versatile nitroalkene building block for organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-Methylbenzo[d]thiazole-7-carbaldehyde | 2-Methylbenzo[d]thiazole-7-carbaldehyde |

The selection of an appropriate microbial host is a foundational step in the construction of efficient yeast cell factories for heterologous pathway expression. This decision critically influences the yield, functionality, and scalability of target recombinant proteins and metabolites. While prokaryotic systems like E. coli offer simplicity and high growth rates, they often lack the eukaryotic machinery necessary for proper protein folding, complex post-translational modifications, and secretion of sophisticated biologics [8]. Among eukaryotic hosts, yeast systems strike a balance between the cellular complexity of mammalian cells and the ease of use of prokaryotes. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice frequently narrows to two principal workhorses: the conventional, well-characterized Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the robust, high-yield Komagataella phaffii (formerly Pichia pastoris) [9] [10]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these systems and outlines detailed protocols to guide host selection and engineering within the context of advanced heterologous pathway research.

Host System Comparison:S. cerevisiaevs.K. phaffii

The optimal host varies significantly with the specific application. The following tables summarize the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each system to inform the selection process.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Yeast Expression Systems

| Characteristic | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Komagataella phaffii |

|---|---|---|

| Doubling Time | ~90 minutes [8] | 60–120 minutes [8] |

| Genetic Tools | Extensive, well-developed [1] [11] | Advanced, rapidly expanding [12] [13] |

| Secretory Capacity | High [10] | Very High; limited endogenous secretion simplifies purification [8] [9] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | N- & O-hyperglycosylation [8] | Human-like glycosylation (shorter high-mannose chains) [8] [10] |

| Typical Glycosylation Pattern | Hypermannosylation (50-150 mannose residues) [8] | Shorter high-mannose chains (~20 mannose residues) [10] |

| Inducible Promoter Example | Galactose-inducible (GAL1, GAL10) | Methanol-inducible (PAOX1) [8] [12] |

| Constitutive Promoter Example | Phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK1) | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (PGAP) [12] |

| Carbon Source | Glucose, Sucrose, Galactose [14] | Glycerol, Methanol, Glucose [8] [12] |

Table 2: Applied Considerations for Host Selection

| Parameter | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Komagataella phaffii |

|---|---|---|

| Key Advantages | • GRAS status• Extensive synthetic biology toolkit [1] [11]• Fast growth• Known physiology | • Extremely high cell densities in bioreactors• Strong, tightly regulated promoters [8] [12]• Low secretion of endogenous proteins [8]• Suitable for membrane protein production [8] |

| Common Challenges | • Hyperglycosylation which can be immunogenic [8]• Metabolic burden at scale | • Methanol metabolism requires specific safety protocols• Codon bias may require optimization [9]• Process optimization is often protein-specific [8] |

| Ideal Applications | • Production of ethanol, flavors, and metabolites [14] [5]• Expression of intracellular proteins• Pathway prototyping and screening | • Production of subunit vaccines and therapeutic proteins [8] [9]• High-level secretory production of enzymes [12] [9]• Expression of complex proteins requiring minimal glycosylation |

Experimental Protocols for Host Engineering and Analysis

Protocol: Engineering aK. phaffiiMutS Strain for Enhanced Protein Secretion

Background: The K. phaffii MutS (Methanol utilization slow) phenotype, resulting from the disruption of the AOX1 gene, slows methanol metabolism. This can be beneficial for certain proteins by reducing metabolic burden and heat generation during induction, potentially leading to higher yields of functional protein [8] [12]. This protocol leverages CRISPR-Cas9 for precise genome editing.

Materials:

- K. phaffii host strain (e.g., GS115, X-33)

- CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid system for K. phaffii

- Donor DNA fragment for gene knockout (designed below)

- Solutions for yeast transformation (e.g., lithium acetate/PEG)

- YPD media, Minimal Dextrose (MD) plates, Minimal Methanol (MM) plates

- Synthetic oligonucleotides for PCR and sequencing

Procedure:

- gRNA Design and Plasmid Construction: Design a gRNA with a 20-nucleotide sequence targeting the AOX1 gene coding region. Clone this gRNA expression cassette into a K. phaffii-specific CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid [12].

- Donor DNA Preparation: Design a linear donor DNA fragment containing a selectable marker (e.g., ARG4) flanked by ~500 bp homology arms upstream and downstream of the AOX1 start and stop codons, respectively. Amplify this fragment via PCR.

- Transformation: Co-transform the K. phaffii host strain with the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid and the linear donor DNA fragment using a standard lithium acetate method.

- Selection and Screening: Plate transformed cells onto MD plates without the appropriate amino acid to select for transformants that have integrated the marker. Isolate individual colonies.

- Phenotype Confirmation (MutS): Streak potential mutants on MM plates. A MutS strain will show significantly slower growth compared to a wild-type (Mut+) control strain over 2-3 days.

- Genotypic Verification: Verify the AOX1 gene replacement by colony PCR using primers flanking the integration site and subsequent DNA sequencing.

Protocol: Analyzing Secretion Efficiency in Yeast Using a β-Glucosidase Reporter

Background: Quantifying secretion efficiency is vital for host screening and engineering. This protocol uses a secreted β-glucosidase (BGL) as a reporter, adaptable for both S. cerevisiae and K. phaffii [15].

Materials:

- Yeast strain with integrated gene for secreted BGL (e.g., with S. cerevisiae α-mating factor signal peptide)

- Deep-well plates or shake flasks

- Appropriate induction media

- Substrate: p-Nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) in buffer

- Stop solution: 1 M Na2CO3

- Microplate reader

Procedure:

- Culture and Induction: Inoculate strains in deep-well plates containing selective media. Grow to mid-log phase, then induce expression (e.g., with methanol for K. phaffii PAOX1, or galactose for S. cerevisiae GAL promoters).

- Sample Collection: At regular intervals post-induction (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours), centrifuge culture aliquots to separate cells from supernatant.

- Secreted Enzyme Assay: Incubate the cell-free supernatant with pNPG substrate. The enzymatic reaction releases yellow p-nitrophenol.

- Reaction Termination and Quantification: After a fixed time, add stop solution (Na2CO3) and measure the absorbance at 405 nm using a microplate reader.

- Data Analysis: Calculate BGL activity from a p-nitrophenol standard curve. Normalize activity to cell density (OD600) or total cell protein to determine specific secretion efficiency.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and engineering a yeast host for a heterologous protein production project, integrating the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Success in yeast metabolic engineering relies on a suite of specialized reagents and genetic tools. The following table details essential components for constructing and analyzing yeast cell factories.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Yeast Cell Factory Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise gene knockouts, integrations, and edits [5]. | Disrupting HOC1 in K. phaffii to increase cell wall permeability and protein secretion [15]. |

| AOX1 Promoter (PAOX1) | Strong, methanol-inducible promoter in K. phaffii for tight regulation and high expression levels [8] [12]. | Controlling the expression of a therapeutic antibody fragment, inducing with methanol in a bioreactor. |

| S. cerevisiae GAL Promoters | Strong, tightly glucose-repressed and galactose-induced promoters for controlled expression [11]. | Regulating a heterologous metabolic pathway to prevent burden during the growth phase. |

| α-Mating Factor (MFα) Signal Peptide | Directs the secretion of recombinant proteins into the culture medium in both S. cerevisiae and K. phaffii [10] [15]. | Secretion of β-glucosidase (BGL) reporter enzyme for quantifying secretion efficiency. |

| 2µ Plasmid Origin | High-copy-number origin for episomal plasmid maintenance in S. cerevisiae [14]. | Rapid pathway prototyping and screening of enzyme variant libraries. |

| Zeocin / Antibiotic Markers | Selective agents for maintaining plasmids and selecting for transformants in various yeast strains [12]. | Maintaining expression vectors in K. phaffii strains like X-33 and SMD1168H. |

| Trimethylol Propane Tribenzoate | Trimethylol Propane Tribenzoate, CAS:54547-34-1, MF:C27H26O6, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (2R)-1,1,1-trifluoropropan-2-ol | (2R)-1,1,1-trifluoropropan-2-ol, CAS:17628-73-8, MF:C3H5F3O, MW:114.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic choice between S. cerevisiae and K. phaffii is not a matter of overall superiority, but of aligning host biology with project objectives. S. cerevisiae remains an unparalleled platform for fundamental research, pathway prototyping, and the production of a wide range of metabolites and intracellular proteins, thanks to its extensive genetic toolbox and well-understood physiology [1] [11]. In contrast, K. phaffii excels in high-density fermentations and the secretory production of complex proteins where its strong, regulated promoters, high secretion capacity, and more human-like glycosylation are decisive advantages [8] [12] [9]. The ongoing development of synthetic biology tools is progressively blurring the historical limitations of each system, enabling researchers to custom-engineer both conventional and non-conventional yeasts into highly efficient, task-specific cell factories for the next generation of biologics and bio-based chemicals [13].

The engineering of yeast cell factories for heterologous pathway expression represents a cornerstone of modern industrial biotechnology, enabling the production of high-value therapeutics, enzymes, and biofuels. The efficiency of these cell factories is fundamentally governed by the precise regulation of key genetic elements: promoters, terminators, and selection markers. These components collectively control transcriptional initiation, transcriptional termination, and the selective pressure necessary for strain construction [16]. Recent advances in synthetic biology, CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, and artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted design have dramatically accelerated the optimization of these elements, leading to substantial improvements in protein folding, pathway flux, andæœ€ç»ˆäº§é‡ [17] [18] [16]. This Application Note details the properties, quantitative performance, and practical protocols for implementing these genetic elements within heterologous expression systems in yeast, providing a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Genetic Elements

Promoter Performance in Yeast Systems

Table 1: Characteristics and performance of common and engineered promoters in yeast.

| Host Organism | Promoter | Type | Strength/Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | TDH3P | Constitutive | One of the highest-performing native promoters [19] | Enhanced heterologous xylanase activity; cultivation on glucose and xylose [19] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | SED1P | Constitutive | Moderate to high expression under stress [19] | Effective for heterologous cellulase and xylanase expression [19] |

| Komagataella phaffii | AOX1 | Inducible (Methanol) | Very strong induction | Common in classical integrative systems [16] |

| Komagataella phaffii | GAP | Constitutive | Strong | High-level expression without methanol induction [16] |

| Aspergillus niger | AAmy | Constitutive | High | Used in a modular platform for expressing diverse proteins [17] |

| Engineered (AI-Designed) | DOSDiff | Constitutive | Up to 1.70-fold expression gain [18] | Demonstrated cross-species functionality in P. pastoris [18] |

Terminator and Selection Marker Efficiency

Table 2: Functional characteristics of terminators and selection markers.

| Element Type | Specific Name | Host | Key Feature/Function | Experimental Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terminator | DIT1T | S. cerevisiae | Outperformed benchmark ENO1P/T terminator [19] | Used effectively in combination with SED1P and TDH3P [19] |

| Terminator | AnGlaA | A. niger | Native terminator used in a heterologous expression platform [17] | Part of a cassette with the AAmy promoter for high-yield production [17] |

| Selection Marker | Geneticin (G418) | K. phaffii | Antibiotic resistance marker | Used for selection in CRISPR/Cas9 systems with episomal Cas9/sgRNA plasmids [20] |

| Selection Marker | Kl.URA3 | K. phaffii | Auxotrophic marker | Enables selection in chaperone library and mating protocols [21] |

| Selection Marker | kanMX (GAL10) | S. cerevisiae | Antibiotic resistance with inducible promoter | Allows selection on G418; induced by galactose in query strains [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Markerless Integration inKomagataella phaffii

This protocol facilitates the seamless integration of expression cassettes into specific genomic loci of K. phaffii without the need for antibiotic resistance markers, ideal for food-grade protein production [20].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cas9/sgRNA plasmid (e.g., CRISPi04576, CRISPiPFK1, CRISPi_ROX1)

- Donor helper plasmid (e.g., crBB3_14 for one transcription unit)

- K. phaffii host strain

- Restriction enzymes (BsaI, BpiI)

- T4 DNA Ligase

- PEG/LiAc transformation mix

- Solid and liquid media (YPG, SC)

Methodology:

- sgRNA and Donor Construction: Clone the sgRNA sequence targeting a specific neutral locus (e.g., 04576, PFK1, ROX1) into a Cas9/sgRNA plasmid. Assemble the heterologous gene expression cassette (promoter-gene-terminator) into the corresponding donor helper plasmid via Golden Gate assembly using BsaI or BpiI [20].

- Co-transformation: Co-transform approximately 1 µg of the linearized donor DNA fragment and the Cas9/sgRNA plasmid into competent K. phaffii cells using a standard PEG/LiAc method [20].

- Screening and Validation: Plate cells on non-selective medium. After 2-3 days, screen individual colonies for correct integration using colony PCR. Verify protein expression via fluorescence (for eGFP) or enzymatic assays [20].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Promoter Strength inSaccharomyces cerevisiae

This protocol outlines a procedure for comparing the performance of different promoters under specific cultivation conditions, as their activity can be unpredictable and context-dependent [19].

Materials and Reagents:

- S. cerevisiae strains with reporter genes (e.g., xylanase, xylosidase) under test promoters (e.g., TDH3P, SED1P)

- Cultivation media: Glucose (aerobic/micro-aerobic), Xylose, Beechwood xylan

- Lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysate

Methodology:

- Strain Cultivation: Inoculate strains in triplicate into media containing different carbon sources (e.g., glucose, xylose, beechwood xylan). Cultivate under both aerobic and micro-aerobic conditions as required [19].

- Sample Harvesting: Harvest cells at the mid-exponential phase. Collect supernatant for secreted enzyme assays and cell pellet for intracellular analysis.

- Activity Assay: Perform enzymatic assays (e.g., on xylanase or xylosidase) tailored to the reporter gene. Measure product formation spectrophotometrically. Normalize activity to cell density or total protein content [19].

- Data Analysis: Compare specific enzyme activities across different promoter constructs and growth conditions to identify the best-performing promoter for the intended application.

Protocol 3: Chaperone Co-expression Screening for Enhanced Production

This protocol uses a mating-based strategy to identify cytosolic chaperones that improve the folding and production of heterologous small molecules or proteins in S. cerevisiae [21].

Materials and Reagents:

- Haploid chaperone overexpression library (MATa, 68 strains) [21]

- Haploid query strain (MATα) expressing the heterologous pathway (e.g., aspulvinone E)

- Solid YPG media with galactose

- Selective plates (SC-Ura + Gal + G418)

Methodology:

- Mating: Replica-pin the arrayed chaperone library strains and the query strain together onto solid YPG media with galactose as the carbon source. Incubate to allow mating [21].

- Diploid Selection: Transfer the mated colonies to a solid medium that selects for diploid cells (e.g., SC-Ura + Gal + G418).

- Production Screening: Transfer the array of diploid strains to a production medium. Assess the production of the target compound (e.g., measure aspulvinone E fluorescence or via UHPLC-DAD-TOFMS) [21].

- Validation: The best-performing chaperone hits (e.g., combined overexpression of YDJ1 and SSA1) should be validated in liquid batch fermentations to quantify the percentage yield improvement [21].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Chaperone Screening Workflow

CRISPR/Cas9 Workflow in K. phaffii

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and their applications in yeast genetic engineering.

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| GoldenPiCS Toolkit [20] | A modular cloning system based on Golden Gate assembly for building expression cassettes. | Assembling promoter, gene, and terminator modules for integration in K. phaffii. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System [17] [20] | Enables precise double-strand breaks and markerless genomic integration via HDR. | Deleting native glucoamylase genes in A. niger; integrating expression cassettes in K. phaffii. |

| AI-Based Design Tool (DOSDiff) [18] | A deep learning framework (D3PM) for de novo design and optimization of promoter sequences. | Generating highly efficient synthetic promoters for S. cerevisiae and P. pastoris. |

| Chaperone Overexpression Library [21] | An arrayed library of S. cerevisiae strains overexpressing one or two cytosolic chaperones. | Identifying chaperones (e.g., Ydj1, Ssa1) that improve folding and yield of heterologous pathways. |

| Neutral Genomic Integration Sites [20] | Specific loci (e.g., 04576, PFK1, ROX1) that allow robust expression without affecting cell fitness. | Targeted, stable integration of heterologous genes in K. phaffii for consistent expression. |

| Methyl 7-methoxy-1H-indole-4-carboxylate | Methyl 7-Methoxy-1H-indole-4-carboxylate|RUO | Methyl 7-methoxy-1H-indole-4-carboxylate is for research use only. Explore its role as a key synthetic intermediate for bioactive molecule development. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 1-(3-Nitrophenyl)-3-phenylprop-2-en-1-one | 1-(3-Nitrophenyl)-3-phenylprop-2-en-1-one, CAS:16619-21-9, MF:C15H11NO3, MW:253.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The engineering of microbial cell factories, particularly using the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is a cornerstone of industrial biotechnology for the sustainable production of biofuels, bioplastics, pharmaceuticals, and high-value compounds [22] [23]. A critical enabling technology for this endeavor is the controlled heterologous expression of metabolic pathways, which is primarily facilitated by specialized plasmid vectors [24]. These vectors allow researchers to introduce, modify, and optimize genes from other organisms into the yeast host. The four main types of S. cerevisiae shuttle vectors—YIp (Yeast Integrating), YEp (Yeast Episomal), YCp (Yeast Centromeric), and YRp (Yeast Replicating)—each possess distinct replication and maintenance strategies, leading to characteristic stability, copy number, and gene expression levels [25] [24] [26]. The rational selection and application of these vectors are fundamental to achieving predictable control of gene expression, which is necessary for balancing metabolic flux, maximizing product titers, minimizing metabolic burden, and ultimately designing efficient yeast cell factories [27] [28] [22]. These vectors are shuttle plasmids, containing components that allow for propagation and selection in both E. coli (for convenient cloning) and S. cerevisiae (for functional expression) [24].

Plasmid Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

The functional differences between YIp, YEp, YCp, and YRp plasmids stem from their unique origins of replication and associated DNA elements, which directly influence their copy number, stability, and suitability for different applications in metabolic engineering [25] [26].

YEp (Yeast Episomal Plasmids) contain a fragment from the native yeast 2µ plasmid circle. This origin allows them to replicate independently of the chromosome as episomes and be maintained at high copy numbers, typically 50+ copies per cell [25]. This high copy number makes them ideal for applications requiring high-level protein expression. However, without selective pressure, they can be somewhat unstable due to uneven segregation during cell division [25].

YCp (Yeast Centromeric Plasmids) incorporate an Autonomously Replicating Sequence (ARS) along with a centromere (CEN) sequence. The centromere ensures proper segregation during mitosis, much like a natural chromosome. Consequently, YCp plasmids are very stable but are maintained at a low copy number, typically 1-2 copies per cell [25]. They are excellent for expressing genes where moderate, stable expression is required, or when the gene product is toxic at high levels.

YRp (Yeast Replicating Plasmids) contain an ARS but lack a centromere. While they can replicate independently and achieve a moderate to high copy number, they are highly unstable and tend to be lost rapidly during mitotic growth in non-selective conditions because they do not segregate efficiently to daughter cells [25] [26].

YIp (Yeast Integrating Plasmids) lack a yeast origin of replication entirely. To be maintained, they must be integrated directly into the host chromosome via homologous recombination [25] [24]. This results in very high stability, as the DNA is passed on like a native gene, but the copy number is typically low (1-2), unless targeted to multi-copy genomic loci. They are used when permanent, stable genetic modification is desired.

Table 1: Characteristics of Primary Yeast Plasmid Vector Systems

| Plasmid Type | Key Components | Copy Number | Stability | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEp (Episomal) | 2µ plasmid origin | High (50+) [25] | Moderate [25] | High-level protein expression; transient overexpression |

| YCp (Centromeric) | ARS, CEN | Low (1-2) [25] | High [25] | Stable, moderate expression; expressing toxic proteins; genomic library construction |

| YRp (Replicating) | ARS | Moderate to High [26] | Low [25] | Rapid, transient gene expression; library screening where high copy number is initially beneficial |

| YIp (Integrating) | Homology arm(s) for recombination | Low (1-2), can be higher if targeted to rDNA [24] | Very High [24] | Stable, permanent gene integration; pathway assembly in chassis strains |

The following diagram illustrates the core replication and inheritance mechanisms of these four plasmid types, which underpin their characteristics described in Table 1.

Quantitative Data for Plasmid Selection

Beyond the basic characteristics, selecting a plasmid system for metabolic engineering requires consideration of quantitative data on plasmid burden and its impact on cell growth. The burden, manifested as reduced growth rates, arises from both the metabolic load of maintaining and replicating plasmid DNA and the expression of the selection marker itself [28].

Table 2: Impact of Plasmid Features on Cellular Burden and Performance

| Feature | Impact on Plasmid Burden/Copy Number | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Selection Marker | Auxotrophic markers (e.g., LEU2, URA3) can impose a significant metabolic burden, reducing growth rate more than the physical load of plasmid replication [28]. Dominant markers (e.g., KanMX) can alleviate this in non-auxotrophic strains. | Marker choice is critical. Auxotrophic selection requires specific host strains but is cost-effective. Antibiotic resistance allows for use in any strain but adds cost [25] [28]. |

| Plasmid Load | The physical DNA load has a minor impact on growth in haploid strains but a more significant effect in diploid strains [28]. | For high-copy YEp plasmids in diploids, the burden is more pronounced. Consider lower-copy vectors or genomic integration for complex pathway expression in diploids. |

| Promoter Strength | Strong promoters (e.g., PTDH3, PGK1) can enhance product formation but may increase burden if protein overexpression is toxic or drains cellular resources [27] [28]. | Weaker or inducible promoters (e.g., GAL1, CUP1) can be used to control expression timing and reduce burden during growth phases [27]. |

| Strain Ploidy | Plasmid burden is generally more pronounced in diploid strains compared to haploid strains [28]. | Haploid strains are often preferred for initial engineering to minimize unintended burden effects. |

Application Protocols for Heterologous Pathway Expression

This section provides detailed methodologies for employing yeast plasmid vectors in the context of optimizing heterologous biosynthetic pathways, a common task in developing yeast cell factories.

Protocol: Modular Pathway Optimization Using Plasmid Libraries

Objective: To generate and screen a combinatorial library of a heterologous biosynthetic pathway by varying the expression levels of individual genes using different plasmid systems. This is a powerful approach to balance metabolic flux [22].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 3 for a complete list.

- Host Strain: S. cerevisiae haploid strain with relevant auxotrophies (e.g., BY4741: his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15Δ0, ura3Δ0) [28].

- Plasmids: A set of YEp and YCp vectors with compatible selection markers (e.g., pRS42X series [HIS3] and pRS41X series [LEU2]) and a range of promoters (e.g., strong: PTDH3, intermediate: TEF1, weak: CYC1) [27] [28].

- Gene of Interest (GOI): Codon-optimized genes for your target pathway.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Plasmid-Based Pathway Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Shuttle Vectors (pRS series) | E. coli/S. cerevisiae plasmids with standardized selection (e.g., HIS3, LEU2) and origins (2μ, CEN/ARS) for flexible cloning and expression [28]. | pRS425 (2μ, LEU2), pRS414 (CEN/ARS, TRP1) |

| Promoter & Terminator Libraries | Modular DNA parts to tune transcription initiation and termination, creating a range of expression strengths for each pathway gene [27] [22]. | Promoters: PTDH3 (strong), TEF1 (medium), PSSA1 (induced post-diauxic) [27]. |

| Auxotrophic Drop-out Media | Selective media lacking specific amino acids or nucleotides to maintain plasmid pressure and ensure plasmid retention in transformed cells [25] [28]. | Synthetic Complete (SC) media lacking leucine (-Leu), uracil (-Ura), etc. |

| Enzymatic Assembly Mix | For seamless and efficient Golden Gate or Gibson assembly of multiple DNA fragments (promoter, GOI, terminator) into a plasmid backbone in a single reaction. | Commercial Gibson Assembly Master Mix or similar. |

| Yeast Transformation Kit | Chemical (LiAc) or electroporation-based reagents for high-efficiency introduction of plasmid DNA into competent yeast cells. | Lithium Acetate (LiAc)/Single-Stranded Carrier DNA/Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) method. |

Procedure:

- Modular Plasmid Construction: For each gene in the pathway, clone the coding sequence into multiple plasmid backbones. This creates a set of vectors where the gene is under the control of different promoters (strong, medium, weak) and maintained at different copy numbers (YEp for high, YCp for low). Use different selection markers for each plasmid to allow for co-transformation.

- Combinatorial Co-transformation: Co-transform the host yeast strain with different combinations of the pathway gene plasmids. For a 3-gene pathway with 3 expression levels each, this will generate a theoretical library size of 3^3 = 27 different strain combinations.

- Library Screening: Plate the transformed yeast cells on appropriate selective media (e.g., SC -Leu -Trp -Ura) to ensure all plasmids are maintained. Pick individual colonies into deep-well plates containing liquid selective media for micro-cultivation.

- Product Titer Analysis: After a suitable fermentation period (e.g., 72-96 hours, capturing both exponential and stationary phases), quantify the titer of the desired metabolic product using HPLC or LC-MS.

- Hit Validation: Re-culture the top-performing strains from the primary screen and re-evaluate their performance in small-scale flask fermentations to validate the increase in product titer and yield.

The workflow for this combinatorial approach, from plasmid construction to screening, is outlined below.

Protocol: Stable Pathway Integration Using YIp Vectors

Objective: To stably integrate a heterologous biosynthetic pathway into the yeast genome for long-term, selection-free expression, which is critical for industrial-scale fermentation.

Materials:

- Host Strain: S. cerevisiae strain with a defined auxotrophy (e.g., ura3Δ0).

- YIp Vector: Contains a selection marker (e.g., URA3) and the GOI, flanked by homology arms targeting a specific genomic locus (e.g., the rDNA cluster for multi-copy integration) [24].

- Restriction Enzymes: For linearizing the plasmid within the homology arm to stimulate homologous recombination.

Procedure:

- Vector Linearization: Digest the YIp plasmid with a restriction enzyme that cuts within the genomic homology arm sequence. This creates a linear DNA fragment with the GOI and marker flanked by homologous ends, dramatically increasing the efficiency of genomic integration.

- Yeast Transformation: Transform the linearized DNA fragment into the host yeast strain using a standard LiAc protocol.

- Selection and PCR Verification: Plate transformed cells on selective media (e.g., SC -Ura) to select for successful integrants. Screen resulting colonies by colony PCR using primers that span the integration junction to verify correct chromosomal integration.

- Curing (Optional): For markers like URA3 that allow for counterselection, the marker can be excised in a subsequent step by plating on 5-Fluoroorotic Acid (5-FOA) to select for cells that have lost the URA3 gene, allowing for iterative engineering [25].

Advanced and Emerging Methodologies

As the field of metabolic engineering advances, so do the tools for gene expression control. Beyond the classic plasmid systems, new technologies enable more dynamic and high-throughput optimization.

Advanced In Vivo Shuffling (GEMbLeR): GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination) is an advanced method that allows for the generation of vast diversity in promoter and terminator combinations directly in the yeast genome [22]. It involves replacing a gene's native regulatory elements with pre-assembled arrays of different promoters and terminators, all flanked by orthogonal LoxPsym sites. Induction of Cre recombinase then shuffles these modules in vivo, creating a massive library of expression variants for a pathway without the need for re-cloning, enabling rapid strain optimization [22].

Considerations for Carbon Source and Fermentation Phase: The choice of promoter and plasmid must account for the fermentation conditions. So-called "constitutive" promoters (e.g., PTEF1, PTDH3) often show sharply decreased activity after glucose depletion (diauxic shift) [27]. For sustained production in industrial batch fermentations, promoters that are induced at low glucose levels (e.g., PADH2, PHXT7) or in the post-diauxic phase (e.g., PSSA1) can be more effective, ensuring pathway expression throughout the fermentation process [27].

Application Notes

Within the context of engineering yeast cell factories for heterologous pathway expression, the precise control of cellular processes is paramount. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) and accurate protein targeting are not merely fundamental biological phenomena; they are critical engineering parameters that directly influence the yield, stability, and functionality of recombinant proteins and metabolites [29] [30] [31]. Mastering these processes is essential for constructing efficient and robust microbial production platforms.

The Role of PTMs in Regulating Protein Stability and Function

PTMs are covalent processing events that rapidly and reversibly alter the properties of a protein, enabling cells to respond dynamically to environmental and metabolic cues. In metabolic engineering, understanding and harnessing these modifications allows for the fine-tuning of pathway enzyme activity and stability.

Ubiquitination and the Control of Metabolic Flux: Ubiquitination primarily serves as a signal for proteasomal degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasomal system (UPS) [30]. This modification is a key mechanism for controlling the concentration of regulatory proteins, such as cell cycle regulators and signaling molecules [29]. For a metabolic engineer, the UPS represents a tool for degrading rate-limiting or undesired enzymes. PTMs like phosphorylation often act as upstream signals that trigger ubiquitination, providing a layer of rapid, reversible regulation before the irreversible commitment to degradation [30]. This cross-talk creates a "PTM-activated degron," where a phosphorylation event can mark a protein for destruction, a mechanism that could be engineered to dynamically control metabolic pathway fluxes.

Methylation as a Regulatory Signal: Beyond its well-known role in histones, protein methylation is a crucial regulator of protein stability. For instance, the methyltransferase SETD7 methylates the NF-κB subunit RELA and hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIF-1α), creating a "methyl-activated degron" that targets these proteins for ubiquitination and degradation [30]. This demonstrates how a single PTM can directly influence the half-life of central regulatory proteins. Engineering the recognition of such degrons could be a strategy to stabilize key enzymes in a heterologous pathway.

Glycosylation for Robustness and Secretion: Glycosylation is vital for the structural integrity of fungal cell walls and the proper folding and secretion of proteins [29] [31].

N-Glycosylation andO-mannosylation are essential for virulence in pathogenic fungi, and their disruption leads to severe cell wall defects [29]. In yeast cell factories, hyperglycosylation of recombinant proteins is a common issue that can impair function [31]. Therefore, engineering the glycosylation pathway towards humanized patterns is a major focus for producing therapeutic proteins like antibodies [31].

Table 1: Key Post-Translational Modifications and Their Impact on Yeast Cell Factories

| PTM | Key Function | Impact on Heterologous Expression | Example in Yeast |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation [29] | Signal transduction, enzyme regulation | Modulates activity of pathway enzymes; can trigger degradation | MAPK cascades regulating stress response and morphogenesis [29] |

| Ubiquitination [29] [30] | Targets proteins for degradation (K48-linkage); non-proteolytic signaling | Controls turnover of metabolic and regulatory proteins | Regulation of cyclins during cell cycle [29] |

| Sumoylation [29] | Transcriptional regulation, stress response, cell cycle | Can stabilize proteins or alter localization | Modification of transcription factors and heat shock proteins [29] |

| Glycosylation [29] [31] | Protein folding, stability, secretion, cell wall integrity | Affects secretion efficiency, activity, and immunogenicity of therapeutics | N- and O-glycosylation of cell wall mannoproteins and secreted enzymes [29] |

| Methylation [30] [32] | Gene regulation, protein stability | Can create degrons to destabilize specific proteins | Methylation of histones by Set1p, Set2p, Set5p, Dot1p [32] |

| Palmitoylation / Farnesylation [29] | Membrane anchoring, protein-protein interactions | Critical for localization of signaling proteins (e.g., Ras) | Ras1 localization to plasma membrane in C. albicans [29] |

Protein Targeting and Secretion for Efficient Production

For a yeast cell factory, the ultimate goal is often the high-yield production and secretion of a target compound. Protein targeting to organelles or the secretory pathway is therefore a critical engineering lever.

The Secretory Pathway as an Engineering Bottleneck: S. cerevisiae possesses a sophisticated eukaryotic secretory pathway, which is advantageous for producing correctly folded proteins with disulfide bonds [31]. However, the secretory transport process can be inefficient, creating a major bottleneck. Engineering strategies focus on overexpressing key components of this pathway, such as chaperones that aid folding and proteins involved in vesicle trafficking, to enhance the overall flux of heterologous proteins through the secretory system [31].

GPI Anchors and Cell Surface Display: Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors are PTMs that tether proteins to the cell surface [29]. In yeast, these anchors can be exploited to display enzymes or binding proteins on the cell wall, a strategy useful for whole-cell biocatalysis or biosensor development [29] [31].

Subcellular Compartmentalization of Pathways: Rerouting heterologous metabolic pathways to specific subcellular compartments, such as the mitochondria or peroxisomes, can concentrate substrates, isolate toxic intermediates, and leverage unique cofactor pools [33]. This spatial reconfiguration is a powerful strategy to enhance pathway efficiency and yield.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analyzing PTMs via Quantitative Mass Spectrometry

This protocol outlines a method for comparative analysis of protein localization and PTMs using quantitative mass spectrometry (MS) of subcellular fractions, adapted from studies in rat liver [34].

1. Principle: Subcellular fractionation is combined with quantitative MS to assign proteins and their modifications to specific organelles. This allows for the creation of a global cellular map and the study of how PTMs influence protein localization and stability.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Lysis/Buffering: Amicon Ultra 0.5 ml 30KDa cellulose filters, 100 mM Tris pH 7.6, 1% lithium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate.

- Reduction/Alkylation: 100 mM DTT, 22.5 mM iodoacetamide in urea buffer (100 mM Tris-HCL, pH 8.5, 8M urea).

- Digestion: Sequencing-grade trypsin, endoproteinase Lys-C.

- Quantification: TMT10 isobaric labeling kit.

- Special Equipment: Ultracentrifuge, SW55Ti rotor, LC-MS/MS system.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

A. Subcellular Fractionation: i. Prepare a post-nuclear supernatant (fraction E) from a homogenized cell culture. ii. Subject fraction E to differential centrifugation to isolate nuclear (N), heavy mitochondrial (M), light mitochondrial (L), microsomal (P), and cytosolic (S) fractions [34]. iii. Further resolve specific organellar fractions (e.g., L1) by density gradient centrifugation using a Nycodenz or sucrose step gradient.

B. Protein Digestion and TMT Labeling: i. For each fraction, reduce 20 μg of protein with DTT and alkylate with iodoacetamide. ii. Digest proteins using a sequential trypsin/Lys-C digestion protocol (16 hours trypsin, followed by 4 hours Lys-C) [34]. iii. Label the resulting peptides from each fraction with a different TMT reporter ion tag according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pool the labeled samples.

C. Mass Spectrometric Analysis: i. Analyze the pooled TMT-labeled peptide sample by LC-MS/MS. ii. For quantification, compare two primary methods: - TMT-MS2: Provides greatest proteome coverage but suffers from ratio compression, narrowing the accurate dynamic range [34]. - TMT-MS3: Uses synchronous precursor selection to diminish ratio compression, resulting in more accurate quantification but potentially lower coverage [34]. iii. Acquire data in a manner that allows for both protein identification and quantification of the TMT reporter ions.

D. Data Analysis: i. Identify proteins and map PTM sites using database search engines. ii. Quantify protein abundance across fractions based on TMT reporter ion intensities. iii. Use clustering algorithms to assign proteins to subcellular compartments based on their abundance profiles across the fractionation series, using a set of well-known marker proteins for validation [34].

Protocol 2: Engineering Yeast for Enhanced Heterologous Protein Secretion

This protocol details strategies to construct S. cerevisiae strains optimized for the high-level secretion of heterologous proteins, a critical goal for efficient downstream processing [31].

1. Principle: Enhance protein secretion by engineering multiple levels of the process: hyperexpression of the gene of interest, optimization of the secretory pathway, and humanization of glycosylation patterns.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Genetic Tools: Codon-optimized synthetic genes, integration plasmids (YIp), episomal plasmids (YEp), CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing.

- Promoters/Terminators: Constitutive (e.g., PGK1, ADH1) and inducible (e.g., GAL1) promoters of varying strengths; optimized terminators.

- Culture Media: Selective media (e.g., SC dropout), induction media (e.g., containing galactose).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

A. Construct a Hyperexpression System: i. Codon Optimization: Synthesize the heterologous gene with codons optimized for S. cerevisiae to improve translational efficiency. Avoid rare codons, adjust GC content, and remove cryptic regulatory sequences [31]. ii. Select an Expression Vector: Choose a high-copy-number episomal plasmid (YEp) for high gene dosage or an integration plasmid (YIp) for stable, single-copy chromosomal insertion [31]. iii. Engineer Transcriptional Control: Clone the codon-optimized gene under the control of a strong, tunable promoter (e.g., inducible GAL1 or constitutive TEF1). Pair with a strong terminator to ensure efficient transcription termination [31].

B. Engineer the Secretory Pathway: i. Overexpress Chaperones: Co-express endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperones like BiP/Kar2p and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) to facilitate proper folding and prevent ER stress [31]. ii. Modulate Vesicle Trafficking: Overexpression of proteins involved in vesicle formation (e.g., the small GTPase Sar1p) and fusion (e.g., the v-SNARE Sec22p) can enhance the flux of proteins from the ER to the Golgi and onward to the plasma membrane [31].

C. Perform Glycosylation Pathway Engineering:

i. Disable Hypermannosylation: Knock out genes responsible for adding elongated mannose chains (e.g., och1Δ) to reduce immunogenic hyperglycosylation [29] [31].

ii. Create Humanized Glycosylation Strains: Introduce pathways for the synthesis of complex human-type N-glycans. This typically involves the knock-in of multiple enzymes, such as mannosidases I and II, N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases I and II, and others, into an och1Δ background [31].

D. Analysis of Success: i. Measure protein yield in the culture supernatant using assays like SDS-PAGE, Western blot, or enzyme activity assays. ii. Analyze glycosylation patterns of the secreted protein using techniques such as lectin blotting or MS.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Yeast Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System [31] | Precise genome editing | Knocking out glycosylation genes (e.g., OCH1); integrating heterologous pathways. |

| Codon-Optimized Genes [31] | Enhances translational efficiency and protein yield | Optimizing heterologous enzyme genes for expression in S. cerevisiae. |

| Inducible Promoters (e.g., GAL1) [31] | Provides temporal control over gene expression | Decoupling cell growth from product formation to avoid metabolic burden. |

| TMT Isobaric Labeling Kits [34] | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics | Simultaneously comparing protein abundance and PTMs across 10+ subcellular fractions. |

| Episomal Plasmids (YEp) [31] | High-copy-number gene expression | Rapid testing and high-level expression of heterologous pathway enzymes. |

Advanced Tools and Workflows for Pathway Design and Implementation

The construction of recombinant DNA molecules is a foundational technology in molecular biology and synthetic biology, enabling the study of gene function and the engineering of microbial cell factories. For researchers focusing on heterologous pathway expression in yeast, the choice of DNA assembly method is critical for efficiently building complex genetic constructs such as multi-gene pathways, CRISPR-Cas9 systems, and protein expression vectors [35]. The evolution from traditional restriction/ligation cloning to modern, seamless techniques has significantly accelerated the pace of metabolic engineering in yeast systems like Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris [36] [37]. These advanced methods facilitate the precise assembly of multiple DNA fragments without leaving unwanted "scar" sequences, enabling the creation of optimized pathways for producing valuable compounds such as terpenoids, biofuels, and therapeutic proteins [36] [38]. This article provides a comprehensive overview of key DNA assembly strategies, with detailed protocols and applications specifically framed within the context of yeast cell factory engineering.

Molecular cloning has undergone a remarkable transformation since the pioneering work of Cohen and Boyer in the 1970s [35]. The early methods relied on restriction enzymes and DNA ligase to cut and paste DNA fragments into plasmid vectors. While these techniques revolutionized biological research, their limitations—including dependence on specific restriction sites and the potential for unwanted scar sequences—spurred the development of more sophisticated, seamless assembly methods [35]. The timeline below visualizes the evolution of these key cloning technologies, highlighting their development and relationships.

The contemporary molecular biology laboratory now has access to multiple advanced cloning techniques, each with distinct mechanisms and optimal use cases. The following table provides a quantitative comparison of the most widely used DNA assembly methods, highlighting key performance characteristics relevant to yeast metabolic engineering.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of DNA Assembly Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Typical Fragment Limit | Seamless? | Key Enzymes | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzyme Ligation | Restriction digestion and ligation | 1-2 fragments | No | Type II RE, DNA Ligase | Simple inserts with compatible sites [39] |

| Gateway Cloning | Site-specific recombination | 1 fragment | No | Integrase, Excisionase | High-throughput transfer to multiple vectors [39] [35] |

| Gibson Assembly | Homologous recombination | 5-15 fragments | Yes | Exonuclease, Polymerase, Ligase | Modular pathway assembly [39] [40] |

| Golden Gate Assembly | Type IIS restriction-ligation | 30+ fragments | Yes | Type IIS RE, DNA Ligase | Combinatorial library construction [39] [40] |

| TOPO-TA Cloning | Topoisomerase-mediated | 1 fragment | No | Topoisomerase I | Rapid cloning of PCR products [39] |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Restriction Enzyme Ligation Cloning

The traditional restriction enzyme ligation method remains a fundamental technique for simple cloning applications. The step-by-step workflow for this method is illustrated below.

Protocol: Restriction Enzyme Ligation Cloning

Step 1: Vector and Insert Preparation

- Digest 1-2 µg of vector and insert DNA with selected restriction enzymes in appropriate buffer. Incubate for 1-2 hours at enzyme-specific temperatures [39].

- Use a 3:1 molar ratio of insert to vector to enhance ligation efficiency.

Step 2: Gel Purification

- Run digested products on an agarose gel and excise bands of interest.

- Purify DNA using gel extraction kits to remove enzymes and buffers.

Step 3: Ligation

- Set up ligation reaction with T4 DNA ligase, using purified vector and insert fragments.

- Incubate at room temperature for 1 hour or 16°C overnight [35].

Step 4: Transformation and Screening

- Transform ligation reaction into competent E. coli cells.

- Screen colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest to identify correct clones.

Application Note for Yeast Engineering: While largely superseded by newer methods, restriction enzyme cloning remains useful for constructing basic expression cassettes with yeast-specific promoters such as TDH3P (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) and SED1P, which have been shown to drive high-level expression of heterologous enzymes in S. cerevisiae [38].

Gibson Assembly

Gibson Assembly, developed by Daniel Gibson in 2009, allows for seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single isothermal reaction [40]. The mechanism employs a three-enzyme cocktail that simultaneously executes exonuclease activity, polymerase extension, and DNA ligation.

Protocol: Gibson Assembly

Step 1: Fragment Preparation with Homology Arms

- Amplify DNA fragments by PCR with 20-40 bp overlapping homologous sequences at their ends [40].

- Gel-purify PCR products to remove primers and non-specific amplification.

Step 2: Assembly Reaction

- Combine DNA fragments with Gibson Assembly master mix containing:

- T5 exonuclease: chews back 5' ends to create single-stranded overhangs

- Phusion DNA polymerase: fills in gaps in the annealed fragments

- Taq DNA ligase: seals nicks in the assembled DNA [40]

- Use approximately 100 ng of total DNA with equimolar ratios of each fragment.

- Combine DNA fragments with Gibson Assembly master mix containing:

Step 3: Incubation and Transformation

- Incubate reaction at 50°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Transform 2-5 µL of reaction into competent E. coli cells [40].

Step 4: Screening

- Screen colonies by analytical PCR or restriction digest.

Application Note for Yeast Engineering: Gibson Assembly is particularly valuable for assembling entire biosynthetic pathways—such as the mevalonate (MVA) pathway for terpenoid production—into yeast expression vectors in a single reaction [36]. Its ability to join up to 15 fragments makes it ideal for constructing multi-gene pathways without introducing scar sequences between genes.

Golden Gate Assembly

Golden Gate Assembly utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes that cut outside their recognition sequences, enabling seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments with unique overhangs in a single reaction [39] [40].

Protocol: Golden Gate Assembly

Step 1: Fragment Design with Type IIS Sites

- Design DNA fragments flanked by Type IIS recognition sites (e.g., BsaI) and unique 4-bp overhangs.

- Ensure overhangs direct correct fragment orientation and order.

Step 2: One-Pot Restriction-Ligation

- Combine DNA fragments with destination vector, Type IIS enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HF), and T4 DNA ligase in appropriate buffer.

- Set up thermal cycling as follows:

- 25-30 cycles of:

- 37°C for 2-5 minutes (digestion)

- 16°C for 2-5 minutes (ligation)

- Final digestion: 37°C for 5-10 minutes

- Heat inactivation: 80°C for 5-10 minutes [40]

- 25-30 cycles of:

Step 3: Transformation and Screening

- Transform entire reaction into competent E. coli.

- Screen colonies for correct assemblies.

Application Note for Yeast Engineering: Golden Gate is exceptionally suited for constructing combinatorial libraries of promoter-gene combinations to optimize flux through heterologous pathways in yeast [39] [40]. Its high efficiency with 30+ fragments enables sophisticated metabolic engineering projects, such as creating diversified enzyme variant libraries for screening improved terpenoid production strains [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of DNA assembly methods for yeast metabolic engineering requires carefully selected molecular biology reagents. The following table details essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Assembly in Yeast Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in DNA Assembly | Yeast Engineering Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | BsaI, BsmBI, BbsI | Create unique 4-bp overhangs outside recognition site | Golden Gate assembly of transcriptional units [40] |

| DNA Ligases | T4 DNA Ligase, Taq DNA Ligase | Catalyze phosphodiester bond formation between DNA fragments | Joining vector-insert junctions in multiple methods [40] [35] |

| Assembly Master Mixes | Gibson Assembly Master Mix, In-Fusion HD Kit | Provide optimized enzyme cocktails for seamless assembly | Accelerating pathway construction in yeast vectors [39] [40] |

| Yeast Expression Vectors | pYES2, pPICZ, episomal/integrative plasmids | Serve as final destination for assembled DNA | Heterologous gene expression under yeast promoters [38] [37] |

| Competent Cells | E. coli (DH5α, TOP10), S. cerevisiae | Propagate assembled plasmids and enable genetic manipulation | Intermediate and final host for pathway assembly [35] |

| Yeast Promoters | TDH3P, SED1P, GAL1P, AOX1 | Drive heterologous gene expression with varying strengths | Fine-tuning metabolic pathway flux [38] [37] |

| 3-Chloro-tetrahydro-pyran-4-one | 3-Chloro-tetrahydro-pyran-4-one, CAS:160427-98-5, MF:C5H7ClO2, MW:134.56 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-Isobutyl-2-mercapto-3H-quinazolin-4-one | 3-Isobutyl-2-mercapto-3H-quinazolin-4-one | 3-Isobutyl-2-mercapto-3H-quinazolin-4-one is a quinazolinone-based compound for research use only (RUO). Explore its potential in medicinal chemistry and agrochemical discovery. Not for human or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The evolution of DNA assembly methods from traditional restriction/ligation to modern techniques like Gibson Assembly and Golden Gate has fundamentally transformed the field of yeast metabolic engineering. These advanced methods offer researchers unprecedented ability to efficiently construct complex multi-gene pathways for heterologous expression in yeast cell factories. The choice between methods depends on specific project requirements: Gibson Assembly excels for modular pathway construction with moderate numbers of fragments, while Golden Gate provides superior capability for high-throughput, combinatorial assembly of large DNA constructs. As the demand for microbial production of valuable compounds continues to grow, these DNA assembly technologies will play an increasingly vital role in accelerating the design-build-test cycles of yeast strain engineering, enabling more efficient and sustainable bioproduction of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and specialty chemicals.

In the construction of yeast cell factories for heterologous pathway expression, precise transcriptional control is a critical determinant of success. The engineering of native and synthetic promoters provides a powerful means to dynamically regulate metabolic flux, separate growth from production phases, and mitigate metabolic burden [41] [42]. This Application Note delineates the functional characteristics, performance parameters, and implementation protocols for both constitutive and inducible promoter systems in yeast, with a specific focus on achieving precise temporal control in heterologous pathway expression for drug development and biochemical production.

Performance Analysis of Yeast Promoter Systems

Quantitative Comparison of Constitutive Promoters

Table 1: Characterized Constitutive Promoters in S. cerevisiae

| Promoter | Source Gene/Type | Relative Strength (Mid-log, Glucose) | Regulatory Pattern | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTDH3 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Very High (Benchmark) | Decreases post-diauxic shift | High-level protein production [43] [19] |

| PADH1 | Alcohol dehydrogenase I | Very High | Decreases post-diauxic shift | General heterologous expression [43] |

| PTEF1 | Translational elongation factor | High | Relatively stable through fermentation | Balanced metabolic engineering [43] |

| PENO2 | Enolase 2 | Very High | Decreases post-diauxic shift | High-level enzyme production [43] |

| PGAP | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (K. phaffii) | High (2-fold lower than strong iSynPs) | Constitutive across carbon sources | Methanol-free expression systems [42] [44] |

| PSED1 | Stress-induced cell wall protein | Moderate-High | Maintains expression on non-native substrates | Lignocellulosic bioprocessing [19] |

Quantitative Comparison of Inducible Promoter Systems

Table 2: Characterized Inducible Promoters and Synthetic Systems

| Promoter/System | Inducer | Basal Expression | Induced Expression | Fold Induction | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGAL1 | Galactose | Low | Very High | ~1000-fold [45] | High induction, carbon source-dependent [43] |

| PAOX1 | Methanol | Low | High | Variable | K. phaffii system, strong methanol induction [46] [44] |

| PCUP1 | Copper | Low | High | High (concentration-dependent) | Chemical inducer, highest post-diauxic expression [43] |

| PADH2 | Low glucose | Repressed on glucose | Moderate | Significant | Autoinduction in batch fermentation [43] |

| DAPG-iSynP | DAPG | Very Low (with insulation) | Very High | >1000-fold [42] | Minimal leakiness, orthogonal system [42] |

| Tet-iSynP | Doxycycline | Very Low | High | >200-fold [42] | Chemical control, tunable with operator repeats [42] |

Experimental Protocols for Promoter Characterization and Implementation

Protocol 1: Quantitative Characterization of Promoter Activity Across Cultivation Conditions

Purpose: To systematically evaluate promoter performance under different carbon sources and throughout batch fermentation, particularly across the diauxic shift [43].

Materials:

- Yeast Strains: S. cerevisiae BY4741 or equivalent with integrated promoter-reporter constructs

- Reporter Plasmids: yEGFP (stable) or yEGFP-CLN2 PEST (destabilized) reporter vectors [43]

- Media: YNB without amino acids supplemented with appropriate carbon sources (20 g/L glucose, sucrose, galactose, or ethanol) [43]

- Equipment: Microtiter plate reader with fluorescence capability, controlled bioreactors for batch cultivation

Procedure:

- Strain Construction: Clone target promoters upstream of yEGFP in yeast integration vectors. Transform into host strain using standard lithium acetate protocol.

- Carbon Source Comparison:

- Inoculate single colonies in 200 μL YNB with different carbon sources in 96-well plates

- Cultivate at 30°C with continuous shaking

- Measure OD600 and GFP fluorescence (excitation 485 nm, emission 520 nm) when cultures reach mid-log phase (OD600 = 1.0-2.5)

- Calculate promoter strength as GFP/OD600 normalized to internal control

- Batch Fermentation Time-Course:

- Inoculate 50 mL YNB with 20 g/L glucose in baffled flasks

- Sample at 3-hour intervals for OD600, GFP fluorescence, and metabolite analysis (glucose, ethanol)

- Continue sampling for at least 72 hours to capture post-diauxic phase

- Data Analysis: Plot promoter activity against cultivation time and metabolic phases. Identify expression patterns in relation to glucose depletion and ethanol production/consumption.

Technical Notes: The destabilized yEGFP-CLN2 PEST (half-life ~12 min) reports real-time transcriptional activity, while stable yEGFP (half-life ~7 h) reflects protein accumulation [43]. For low-expression promoters, stable yEGFP provides better signal-to-noise ratio.

Protocol 2: Implementation of Synthetic Inducible Promoters with Minimal Leakiness

Purpose: To construct and optimize tightly regulated synthetic inducible promoters in yeast using insulation strategies and operator engineering [42].

Materials:

- DNA Parts: Core promoters (KpAOX1, ScGAL1), operator sequences (phlO, tetO, luxO), insulator sequences (1.6 kb KpARG4)

- Expression Vectors: Yeast integration plasmids with selection markers

- sTA Constructs: Regulatable synthetic transcription activators (rPhlTA, rTetTA, LuxTA)

- Host Strains: Komagataella phaffii or S. cerevisiae with appropriate genetic background

Procedure:

- Insulator Integration:

- Amplify ~1.6 kb insulator sequence (e.g., KpARG4 from K. phaffii)

- Clone immediately upstream of core promoter using Gibson Assembly or Golden Gate cloning

- Verify insertion by colony PCR and sequencing

- Operator-Promoter Fusion:

- Design primers to fuse operator repeats directly upstream of TATA-box sequence

- Test 1-4 operator repeats with 0-40 bp spacing to TATA-box

- Assemble constructs using in vivo or in vitro DNA assembly methods

- Leakiness Screening:

- Co-transform promoter-reporter (EGFP) and sTA plasmids into host strain

- Plate transformants on selective media without inducer

- Screen for colonies with minimal fluorescence using flow cytometry or plate reader

- Isulate variants with >100-fold induction capability

- Induction Characterization:

- Inoculate positive clones in selective media and grow to mid-log phase

- Add inducer (DAPG, doxycycline, or HSL) at optimal concentration

- Monitor EGFP expression over 24 hours to determine induction kinetics

- Calculate fold induction as (fluorescence with inducer)/(fluorescence without inducer)

Technical Notes: The 1.6 kb insulator sequence reduces leakiness by up to 376-fold while maintaining >95% of induced activity [42]. Direct fusion of operators to TATA-box with minimal spacing (≤40 bp) maximizes fold induction. For S. cerevisiae, a 110-bp iSynP containing 68-bp ScGAL1 core promoter fused to phlO achieved >100-fold induction [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Promoter Engineering Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter Genes | yEGFP, yEGFP-CLN2 PEST, mCherry, lacZ | Quantitative promoter activity assessment | Destabilized reporters for real-time transcription monitoring [43] |

| Core Promoters | KpAOX1 (94 bp), ScGAL1 (68 bp), KpDAS1 (83 bp) | Minimal functional promoter elements | Enable compact iSynP design with high performance [42] |

| Operator Systems | phlO (DAPG), tetO (doxycycline), luxO (HSL) | Inducer-responsive DNA binding sites | Operator repeats (2-4x) enhance induction magnitude [42] |

| Insulator Sequences | KpARG4 (1.6 kb), random 30-bp sequences | Block cryptic transcriptional activation | Essential for minimizing iSynP leakiness [42] |

| Synthetic TFs | rPhlTA, rTetTA, LuxTA, BM3R1-NLS-VP16 (SES) | Orthogonal transcription activation | Enable custom regulatory circuits without crosstalk [42] [44] |

| Assembly Systems | Golden Gate (GoldenPiCS), Gibson Assembly, PGASO | Modular DNA construction | Facilitate rapid promoter variant generation and testing [46] [47] |

| 3-Hydroxy-5-(methoxycarbonyl)benzoic acid | 3-Hydroxy-5-(methoxycarbonyl)benzoic acid, CAS:167630-15-1, MF:C9H8O5, MW:196.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 1-Benzyl-6-hydroxy-7-cyano-5-azaindolin | 1-Benzyl-6-hydroxy-7-cyano-5-azaindolin, CAS:66751-31-3, MF:C15H13N3O, MW:251.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Conceptual Framework and Experimental Workflows

Decision Framework for Promoter Selection

Synthetic Promoter Engineering Workflow

The strategic implementation of promoter engineering approaches enables unprecedented temporal control of heterologous pathway expression in yeast cell factories. While constitutive systems provide simplicity and generally high expression levels, their activity profiles during fermentation and across different carbon sources must be carefully considered [43] [19]. Inducible systems, particularly synthetic promoters with insulation and optimized operator architecture, offer tight regulation with minimal basal expression and high induction ratios exceeding 1000-fold [42]. The continued development of orthogonal regulatory systems and cross-species promoter elements [44] will further expand the toolbox available for metabolic engineering and biopharmaceutical production in yeast platforms.

CRISPR-Cas9 and Genome Editing for Stable Pathway Integration