FBA vs 13C-MFA: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Metabolic Flux in E. coli

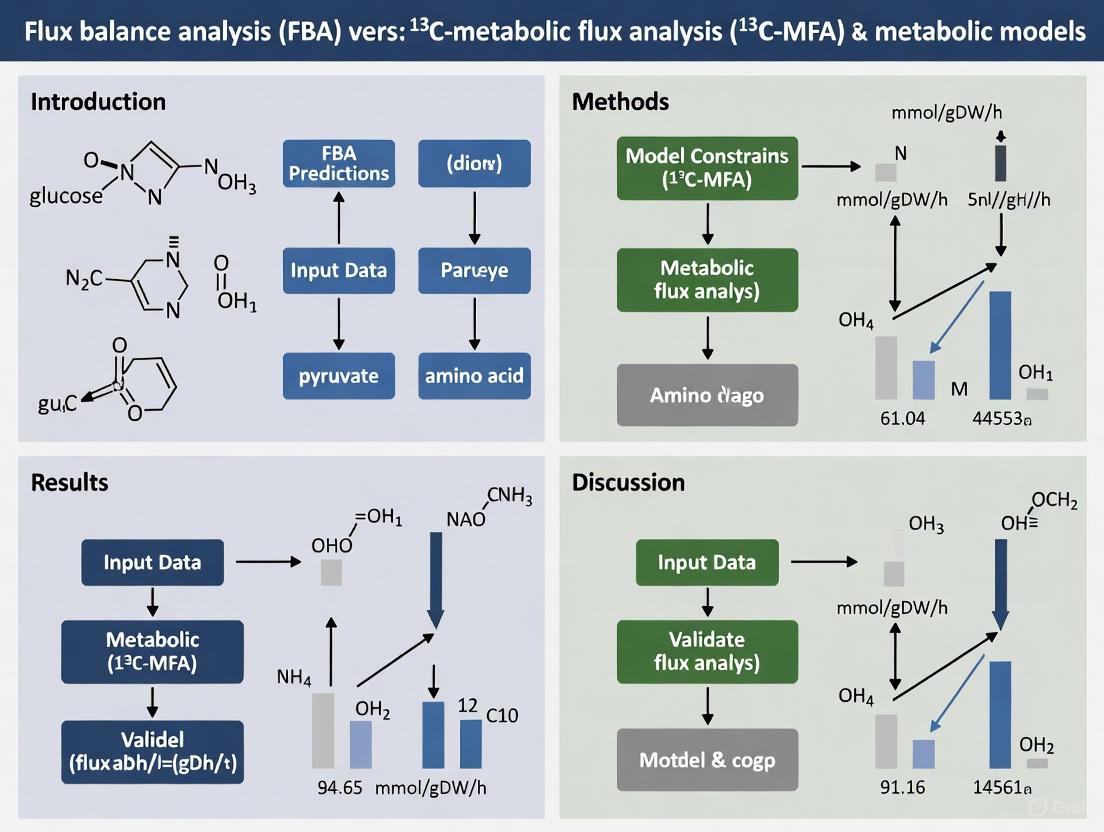

This article provides a systematic comparison between Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) for determining intracellular metabolic fluxes in Escherichia coli.

FBA vs 13C-MFA: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Metabolic Flux in E. coli

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison between Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) for determining intracellular metabolic fluxes in Escherichia coli. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and complementary applications of these two cornerstone techniques. We detail how 13C-MFA serves as an empirical benchmark for validating and refining constraint-based FBA predictions, covering advanced topics such as software tools for flux calculation, strategies for analyzing knockout mutants, and methods for integrating transcriptomic data. The synthesis offers a practical framework for selecting and applying these tools to elucidate metabolic network operations, with direct implications for metabolic engineering, antibiotic resistance research, and understanding bacterial physiology.

Core Principles: From Stoichiometric Modeling to Experimental Flux Measurement

Defining Metabolic Flux Analysis and its Role in Systems Biology

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) is an experimental fluxomics technique that quantitatively examines the production and consumption rates of metabolites in a biological system [1]. It enables the quantification of metabolic fluxes at an intracellular level, thereby elucidating the central metabolism of the cell and providing one of the most direct descriptions of metabolic network operation [1] [2]. Metabolic fluxes represent the integrated functional phenotype that emerges from multiple layers of biological organization and regulation, including the genome, transcriptome, and proteome [3]. As such, the study of metabolic fluxes is critically important for systems biology, rational metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology [3].

The flow of mass and energy through a metabolic network is driven by metabolic fluxes, which determine the proportion of various pathways in all cellular functions and metabolic processes [4]. Accordingly, accurate quantification of metabolic fluxes is essential for metabolic engineering, especially metabolite development, where the main objective is to convert the maximum amount of substrate into useful products [4]. MFA provides quantitative insights into the flow of carbon, energy, and electrons within a living organism that cannot be obtained from other omics measurements [5].

Methodological Approaches in Metabolic Flux Analysis

Core Techniques and Principles

Several flux analysis techniques have been developed and implemented with powerful software tools for data collection and analysis. The selection of specific techniques largely depends on the type of analysis required. The main methodological approaches include:

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A constraint-based modeling approach that uses a stoichiometric model to study the fluxome of metabolic networks. FBA identifies metabolic flux distributions that optimize certain objectives, usually maximizing growth, through linear optimization [3] [2]. It requires minimal experimental data and can analyze genome-scale stoichiometric models (GSSMs) that incorporate all known reactions based on genome annotation and manual curation [3].

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA): This constraint-based approach quantifies fluxes from experimentally measured extracellular rates (substrate uptake, oxygen uptake, growth rate, product secretion) subject to stoichiometric constraints, without assuming optimal cell performance [5].

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA): Considered the gold standard for accurate flux quantification in metabolic engineering, this method uses one or more 13C-labeled substrates fed to growing cells until the 13C-labeled carbons are fully incorporated into intracellular metabolites [5]. It operates under both metabolic steady state (constant metabolic fluxes) and isotopic steady state (static isotope incorporation) [6].

Isotopically Non-Stationary MFA (INST-MFA): This approach uses transient 13C-labeling data at metabolic steady state, monitoring tracer accumulation in intracellular metabolites over time before the system reaches isotopic steady state [1] [6]. Although experimentally faster than 13C-MFA, it is computationally more complex as it requires solving differential equations for each time point [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Flux Analysis Methodologies

| Method | Abbreviation | Labeled Tracers | Metabolic Steady State | Isotopic Steady State | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis | FBA | No | Yes | Not Applicable | Genome-scale; optimization-based; predictive |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | MFA | No | Yes | Not Applicable | Uses measured extracellular rates |

| 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis | 13C-MFA | Yes | Yes | Yes | High precision; gold standard |

| Isotopic Non-Stationary MFA | 13C-INST-MFA | Yes | Yes | No | Faster experimentally; computationally intensive |

| Dynamic MFA | DMFA | Optional | No | Not Applicable | Captures flux transients |

Experimental Workflow for 13C-MFA

The standard experimental procedure for 13C-MFA involves multiple carefully controlled stages as illustrated below:

Experimental 13C-MFA Workflow

The workflow begins with cell culture on labeled substrates, where a substrate such as glucose is labeled with isotopes (most often 13C) and introduced into the culture medium [1]. The medium typically contains vitamins and essential amino acids to facilitate cell growth [1]. The labeled substrate is then metabolized by the cells, leading to the incorporation of the 13C tracer into other intracellular metabolites [1].

After the cells reach steady-state physiology (constant metabolite concentrations in culture), cells are lysed to extract metabolites [1]. For mammalian cells, extraction involves quenching cells using methanol to stop cellular metabolism, followed by subsequent extraction of metabolites using methanol and water [1]. The concentrations of metabolites and labeled isotopes in metabolite extracts are measured by instruments like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry or NMR, which also provide information on the position and number of labeled atoms on the metabolites [1]. This data is essential for gaining insight into the dynamics of intracellular metabolism and metabolite turnover rates to infer metabolic flux [1].

The final stages involve computational modeling and flux calculation using specialized software tools. Metabolic fluxes are estimated by optimizing the fit between experimentally measured and simulated labeling patterns [7]. The resulting flux map undergoes statistical validation to evaluate the reliability of flux estimates, often using methods like the χ2-test of goodness-of-fit [3].

FBA vs. 13C-MFA: A Comparative Analysis in E. coli Research

Fundamental Differences and Complementary Strengths

Flux Balance Analysis and 13C-MFA offer complementary approaches to understanding metabolic networks in Escherichia coli, each with distinct methodological foundations and applications. FBA is a constraint-based modeling framework that predicts metabolic capabilities using stoichiometric models and optimization principles, typically maximizing biomass production [2]. In contrast, 13C-MFA is an experimental approach that measures actual in vivo fluxes by combining stoichiometric models with isotopic tracer data [2].

The synergy between these approaches was demonstrated in a landmark study investigating metabolic adaptation to anaerobiosis in E. coli K-12 MG1655 [2]. Researchers performed both genome-scale FBA and 13C-MFA analyses under identical aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions in defined minimal medium with glucose as the sole carbon source [2]. This direct comparison revealed that while FBA successfully predicted product secretion rates in aerobic culture when constrained with measured glucose and oxygen uptake rates, the most frequently predicted values of internal fluxes obtained by sampling the feasible space differed substantially from MFA-derived fluxes [2].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of FBA and 13C-MFA for E. coli Metabolic Studies

| Parameter | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Optimization principle (e.g., growth maximization) | Experimental isotopic labeling data |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (hundreds to thousands of reactions) | Core metabolism (typically <100 reactions) |

| Data Requirements | Minimal (primarily extracellular fluxes) | Extensive (extracellular fluxes + isotopic labeling) |

| Key Assumptions | Metabolic steady-state; optimal cell performance | Metabolic and isotopic steady-state |

| Flux Resolution | Predicts flux ranges; multiple optimal solutions possible | Precise flux quantification; unique solution |

| TCA Cycle Analysis | Predicted complete TCA cycle | Revealed incomplete TCA cycle in aerobic E. coli |

| ATP Metabolism | Identified ATP synthase activity for proton secretion | Quantified maintenance ATP consumption (37.2% aerobic, 51.1% anaerobic) |

| Exchange Fluxes | Cannot quantify reversible reaction rates | Can estimate forward and reverse fluxes (exchange fluxes) |

Experimental Protocol for Comparative Flux Analysis in E. coli

Bacterial Strain and Growth Conditions:

- E. coli K-12 MG1655 (ATCC 47076) cultured in defined M9 minimal medium with 2 g/L glucose as sole carbon source [2]

- Both aerobic and anaerobic cultures incubated at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm [2]

- Cells harvested at mid-log phase by centrifugation at 2000× g for 10 minutes at 4°C [2]

13C-Labeling Experiment:

- Use of specifically labeled [1,2-13C]glucose or uniformly labeled [U-13C]glucose as tracer substrate [5] [7]

- Culture duration sufficient to reach metabolic and isotopic steady-state (typically 4+ hours for E. coli) [6]

Analytical Measurements:

- Extracellular fluxes: Glucose uptake rate, secretion rates of fermentation products (acetate, lactate, succinate, formate, ethanol), oxygen uptake rate (aerobic), CO2 evolution rate [2]

- Labeling measurements: GC-MS or LC-MS analysis of proteinogenic amino acids and intracellular metabolites [2]

- Growth parameters: Specific growth rate, biomass composition [2]

Computational Flux Analysis:

- 13C-MFA: Flux estimation using computational tools (e.g., INCA, 13CFLUX2) that minimize differences between measured and simulated labeling patterns [3] [7]

- FBA: Constraint-based modeling using genome-scale model (e.g., iJR904) with measured extracellular fluxes as constraints [2]

- Statistical validation: χ2-test of goodness-of-fit for 13C-MFA models; comparison of predicted vs. measured fluxes for FBA [3]

Key Insights from E. coli Flux Validation Studies

The comparative analysis of FBA and 13C-MFA in E. coli research has yielded several fundamental insights into bacterial metabolism and the capabilities of these analytical approaches:

Metabolic Network Operation and Energy Metabolism

The synergy of MFA and FBA revealed that the TCA cycle operates in a non-cyclic manner in aerobically growing E. coli cells, contrary to the complete cycle typically assumed in metabolic models [2]. 13C-MFA quantification showed that the fraction of maintenance ATP consumption in total ATP production is approximately 14% higher under anaerobic (51.1%) than aerobic conditions (37.2%) [2]. Complementary FBA analysis indicated that this increased ATP utilization is consumed by ATP synthase to secrete protons during fermentation [2].

Furthermore, the integrated analysis demonstrated that submaximal growth in E. coli is due to limited oxidative phosphorylation rather than insufficient carbon conversion [2]. These findings illustrate how the combination of experimental flux measurement (13C-MFA) and theoretical network capability analysis (FBA) provides a more complete understanding of metabolic function than either approach alone.

Validation of Predictive Capabilities

The comparative studies have helped evaluate the accuracy and limitations of FBA predictions. When FBA was constrained with both glucose and oxygen uptake measurements, it successfully predicted product secretion rates in aerobic E. coli cultures [2]. However, the internal flux distributions obtained through sampling the feasible solution space often differed substantially from 13C-MFA derived fluxes [2]. This highlights a critical limitation of FBA: while it may correctly predict input-output relationships, the internal flux distributions are not necessarily uniquely determined or biologically accurate.

The relationship between these methodologies can be conceptualized as follows:

Interrelationship Between Metabolic Modeling Approaches

This synergistic relationship enables the development of more accurate kinetic models parameterized using 13C-MFA data, as demonstrated in studies where flux ranges from 13C-MFA of E. coli mutant strains were used to parameterize core kinetic models (k-ecoli74) [7]. The resulting kinetic model successfully predicted 86% of flux values for strains used during fitting within a single standard deviation of 13C-MFA estimated values [7].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Scaling 13C-MFA to Genome-Scale

Recent methodological advances have enabled the application of 13C-MFA principles at a genome-scale, addressing the traditional limitation of being restricted to core metabolism. One study constructed a genome-scale metabolic mapping (GSMM) model for E. coli with 697 reactions and 595 metabolites, compared to a core model of 75 reactions and 65 metabolites [8]. This scaling-up revealed several important insights:

- Both topology and estimated values of metabolic fluxes remained largely consistent between core and genome-scale models [8]

- The genome-scale model identified wider flux inference ranges for key reactions in the core model, with glycolysis flux range doubling due to possible active gluconeogenesis [8]

- The transhydrogenase reaction flux became essentially unresolved due to the presence of five alternative routes for NADPH-NADH interconversion in the genome-scale model [8]

- A non-zero flux for the arginine degradation pathway was identified to meet biomass precursor demands [8]

Expanding to Complex Biological Systems

Methodological innovations continue to expand the applicability of MFA to more complex biological scenarios:

- Microbial communities: Novel peptide-based 13C-MFA methods enable flux analysis in microbial communities by using peptide labeling patterns instead of amino acid labeling, allowing species-specific flux determination through proteomic techniques [9]

- Non-standard systems: Advanced 13C-MFA methodologies now support flux analysis in systems where isotopic steady state cannot be reached, where metabolic fluxes are not constant, or where multiple organisms grow in heterogeneous culture [5]

- Integration with kinetic modeling: Large-scale 13C-MFA datasets enable the construction of predictive kinetic models of metabolism, moving beyond constraint-based approaches to dynamic simulations [5] [7]

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Flux Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Carbon source for labeling experiments; enables tracking of metabolic pathways | [1,2-13C]glucose; [1,6-13C]glucose; [U-13C]glucose; 13C-CO2; 13C-NaHCO3 [6] |

| Analytical Instruments | Measurement of metabolite labeling patterns and concentrations | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS); Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS); Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) [1] [6] |

| Computational Software | Flux calculation, data analysis, and metabolic network modeling | 13CFLUX2; OpenFLUX; INCA; METRAN [1] [6] |

| Stoichiometric Models | Framework for constraint-based flux analysis | Core metabolic models; Genome-scale models (e.g., iAF1260 for E. coli) [8] |

| Cell Culture Components | Support defined growth conditions for labeling experiments | M9 minimal medium; vitamins; essential amino acids [1] [2] |

| Metabolite Extraction Kits | Quenching of metabolism and extraction of intracellular metabolites | Methanol-water extraction; quenching protocols [1] |

Metabolic Flux Analysis, particularly 13C-MFA, provides an indispensable toolset for quantifying metabolic phenotypes in systems biology and metabolic engineering. The comparative analysis with Flux Balance Analysis reveals a powerful synergistic relationship: FBA offers genome-scale predictive capabilities based on optimization principles, while 13C-MFA delivers precise, experimental validation of internal flux distributions. In E. coli research, this synergy has uncovered fundamental physiological insights, including the non-cyclic operation of the TCA cycle, differential ATP maintenance requirements under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, and limitations in oxidative phosphorylation. As methodological advances continue to expand the scope of MFA to genome-scale models, microbial communities, and kinetic model parameterization, these flux analysis approaches will remain cornerstone methodologies for unraveling metabolic complexity and guiding metabolic engineering strategies.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a computational method that predicts the flow of metabolites through a biological network, enabling researchers to study microbial physiology at a systems level. As a constraint-based approach, FBA does not require detailed kinetic parameters but instead relies on the stoichiometry of the metabolic network and physicochemical constraints to predict optimal flux distributions. By leveraging genome-scale metabolic models (GSMs), FBA calculates metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) that maximize or minimize specific biological objectives, most commonly biomass production for microbial growth [10]. The fundamental principle of FBA involves defining all possible metabolic flux distributions that satisfy mass-balance constraints and then identifying the particular flux map that optimizes a cellular objective, providing a powerful framework for predicting metabolic behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions [3] [11].

The foundation of FBA lies in representing metabolism through a stoichiometric matrix S where m rows represent metabolites and n columns represent metabolic reactions. The mass balance constraint is represented mathematically as S · v = 0, where v is the flux vector containing all reaction rates in the network. Additional constraints are imposed based on reaction reversibility (αi ≤ vi ≤ β_i) and measured uptake/secretion rates [10]. Since these constraints typically define multiple possible flux distributions, FBA uses linear programming to identify a particular solution that optimizes an objective function, commonly formulated as Z = c · v, where c is a vector of weights selecting a linear combination of fluxes to optimize [10]. For simulation of growth, c is typically defined as the unit vector in the direction of the biomass production flux.

Methodological Framework of FBA

Core Computational Workflow

The standard FBA workflow involves several key steps, beginning with the reconstruction of a genome-scale metabolic network from genomic, biochemical, and physiological data. This network reconstruction forms the basis for the stoichiometric model that encapsulates all known metabolic reactions in the organism. The next critical step involves applying mass balance constraints, which ensure that the production and consumption of each metabolite are balanced at metabolic steady state. Further constraints are then applied based on reaction directionality (irreversible reactions cannot carry negative fluxes) and measured substrate uptake rates [10].

Once the constrained solution space is defined, FBA identifies an optimal flux distribution by solving a linear programming problem that maximizes or minimizes a specific cellular objective. The most commonly used objective function is the maximization of biomass production, which simulates the evolutionary pressure for rapid growth, though other objectives such as ATP production or metabolite synthesis can also be implemented [12] [10]. The output is a predicted flux map that represents the theoretical capabilities of the metabolic network under the specified conditions. For studies involving gene deletions, the corresponding reactions are constrained to zero flux, and the revised network capabilities are computed [10].

Conceptual Workflow of FBA

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps involved in conducting Flux Balance Analysis:

Experimental Design and Protocols

Implementation of FBA for E. coli Gene Deletion Studies

The application of FBA to analyze Escherichia coli metabolism typically begins with the formulation of a comprehensive genome-scale metabolic model. The iJR904 model for E. coli K-12, which contains 904 genes and 931 metabolic reactions, provides a well-established framework for such studies [2]. To simulate gene deletions, all metabolic reactions catalyzed by the targeted gene products are computationally constrained to carry zero flux. For reactions catalyzed by multiple enzymes, all isozyme-encoding genes must be simultaneously removed, while for enzyme complexes, all subunit-encoding genes are deleted concurrently [10].

The computational protocol involves several sequential steps. First, the specific uptake fluxes for carbon sources (typically glucose at 2 g/L in M9 minimal medium) are defined, with aerobic conditions simulated by allowing oxygen uptake and anaerobic conditions by restricting oxygen uptake to zero [2]. The linear programming problem is then solved with biomass maximization as the objective function using optimization tools such as the COBRA Toolbox or cobrapy [11]. The output includes predictions of growth rates, substrate uptake rates, and byproduct secretion, which can be validated against experimental measurements. For more comprehensive analyses, Phenotype Phase Planes (PhPPs) can be generated to explore optimal metabolic behaviors across varying environmental conditions, such as different substrate and oxygen uptake rates [10].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for FBA Studies

| Category | Specific Resource | Function in FBA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Models | iJR904 E. coli model [2] | Genome-scale stoichiometric model containing 904 genes and 931 reactions for flux predictions |

| Software Tools | COBRA Toolbox [11] | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis |

| Software Tools | cobrapy [11] | Python package for constraint-based modeling of biological networks |

| Software Tools | LINDO [10] | Commercial linear programming package for solving optimization problems |

| Cultivation Media | M9 minimal medium with glucose [2] | Defined medium for controlled bacterial growth and uptake/secretion measurements |

| Analytical Techniques | Gas chromatography-Mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [13] | Measurement of extracellular metabolite concentrations for model constraints |

FBA vs. 13C-MFA: A Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Methodological Differences

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) represent complementary approaches for investigating metabolic fluxes, with distinct theoretical foundations and data requirements. FBA is a constraint-based, predictive approach that uses genome-scale metabolic models and optimization principles to predict flux distributions, typically maximizing biomass production or other cellular objectives [2] [10]. In contrast, 13C-MFA is an experimentally driven, inferential method that utilizes isotopic labeling patterns from 13C-tracer experiments to determine intracellular fluxes through computational fitting of labeling data to a metabolic network model [2] [3].

The fundamental distinction lies in their approach to flux determination: FBA predicts fluxes based on hypothesized optimality principles, while 13C-MFA infers fluxes from experimental measurements of isotopic enrichment [2]. This difference translates to divergent capabilities and limitations. FBA can analyze genome-scale networks but relies heavily on the chosen objective function and requires extracellular flux measurements as constraints [2] [3]. Conversely, 13C-MFA provides more accurate estimates of intracellular fluxes, including reversible reactions and metabolic cycles, but is typically limited to central carbon metabolism due to analytical and computational constraints [2] [13].

Comparative Performance in E. coli Studies

Table: Experimental Comparison of FBA and 13C-MFA in E. coli Metabolism

| Parameter | FBA Approach | 13C-MFA Approach | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCA Cycle Prediction | Predicts complete TCA cycle | Revealed incomplete TCA operation (16.1% flux entry) [2] | Aerobic growth on glucose |

| ATP Maintenance | Not directly quantified | Showed 14% higher maintenance ATP in anaerobiosis (51.1% vs 37.2%) [2] | Aerobic vs. anaerobic growth |

| External Flux Prediction | Accurate for secretion rates when constrained with uptake measurements [2] | Directly measures secretion and uptake fluxes | Product formation rates |

| Internal Flux Accuracy | Sampled fluxes differed substantially from MFA values [2] | Considered reference for intracellular fluxes | Central metabolic pathways |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (iJR904: 931 reactions) [2] | Typically core metabolism (reactions with carbon transitions) [2] | E. coli K-12 MG1655 |

| Data Requirements | Extracellular fluxes, growth rates | Extracellular fluxes + isotopic labeling patterns | Glucose minimal medium |

Direct comparative studies on E. coli metabolism have revealed both complementary insights and significant discrepancies between FBA predictions and 13C-MFA measurements. When both glucose and oxygen uptake measurements were used as constraints, FBA successfully predicted product secretion rates in aerobic cultures [2]. However, internal flux distributions obtained through sampling the feasible solution space showed substantial differences from 13C-MFA-derived fluxes [2]. The synergy between both approaches has proven particularly valuable – for instance, combined FBA and 13C-MFA analysis revealed that the TCA cycle operates in a non-cyclic manner during aerobic growth on glucose, with FBA helping to explain that submaximal growth results from limitations in oxidative phosphorylation [2].

Validation and Best Practices

Model Validation Frameworks

Robust validation is essential for ensuring the reliability of FBA predictions, particularly given the methodological limitations and assumptions inherent to the approach. The COnstraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis (COBRA) framework includes fundamental quality control checks, such as verifying that models cannot generate ATP without an external energy source or synthesize biomass without essential substrates [11]. The MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) pipeline provides additional validation through standardized tests assessing stoichiometric consistency, mass and charge balance, and biomass synthesis capability across different growth media [11].

For validating FBA predictions against experimental data, several approaches have been established. Qualitative validation may involve comparing predicted growth versus non-growth phenotypes on specific carbon sources with experimental observations [11]. More rigorous quantitative validation compares predicted growth rates with measured values, providing information about the overall efficiency of substrate conversion to biomass, though this offers limited insight into the accuracy of internal flux predictions [11]. The most comprehensive validation involves comparing FBA predictions with intracellular fluxes determined experimentally via 13C-MFA, particularly for central carbon metabolism where 13C-MFA is considered most reliable [2] [3].

Pathway Utilization in E. coli Metabolism

The following diagram illustrates the key metabolic pathways in E. coli and how FBA and 13C-MFA provide complementary insights into their operation:

Flux Balance Analysis represents a powerful constraint-based framework for predicting metabolic behavior at genome scale, with particular utility in microbial systems such as Escherichia coli. Its key strengths include the ability to analyze system-wide network capabilities without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, predict outcomes of genetic modifications, and integrate diverse physiological constraints. However, comparative studies with 13C-MFA have revealed significant limitations in FBA's ability to accurately predict intracellular flux distributions, particularly for complex metabolic processes such as TCA cycle operation and energy metabolism [2]. The synergy between both approaches – leveraging FBA's genome-scale predictive capabilities with 13C-MFA's experimental validation of intracellular fluxes – provides a robust framework for advancing metabolic engineering and systems biology research. Future developments in model validation, incorporation of regulatory constraints, and integration of multi-omics data will further enhance FBA's utility as a predictive tool in biological research and biotechnology applications.

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) has emerged as the gold standard technique for quantifying intracellular metabolic reaction rates (fluxes) in living organisms. As a powerful tool for deciphering the operational phenotype of metabolic networks, 13C-MFA integrates stable isotope tracer experiments with computational modeling to resolve fluxes with high precision. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of 13C-MFA against constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), with a specific focus on flux validation studies in Escherichia coli. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and pathway visualizations to illustrate how 13C-MFA serves as an empirical benchmark for validating and refining metabolic models, thereby enhancing their predictive power in metabolic engineering and drug development.

Quantifying the intracellular fluxome—the complete set of metabolic reaction rates—is crucial for understanding cellular physiology in systems biology and for guiding metabolic engineering strategies. The two primary computational frameworks for flux analysis are 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA). While both methods employ stoichiometric models of metabolism assuming a metabolic steady-state, their underlying principles and outputs are distinct [3]. FBA is a constraint-based modeling approach that predicts flux distributions by postulating an objective function, typically the maximization of biomass production or growth rate [2]. It defines a solution space containing all flux maps consistent with stoichiometric and thermodynamic constraints but does not require experimental isotopic labeling data. Consequently, FBA is particularly useful for predicting metabolic capabilities and external secretion rates [2].

In contrast, 13C-MFA is an analytical methodology that infers in vivo fluxes by fitting experimental data from isotope labeling experiments (ILEs) [14]. When cells are fed with 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose), the label is distributed through metabolic pathways, generating unique isotopic patterns in intracellular metabolites that depend on the active fluxes [15] [16]. By measuring these labeling patterns and using computational models to interpret them, 13C-MFA determines a single, statistically justified flux map that best fits the experimental data [3]. This makes 13C-MFA a powerful tool for measuring the actual metabolic phenotype of an organism under specific conditions, thereby providing a reliable benchmark for validating FBA predictions [2].

Core Principles and Workflow of 13C-MFA

The power of 13C-MFA stems from its rigorous integration of experimental analytics and mathematical modeling. The core principle is that the distribution of 13C atoms in metabolic intermediates is a direct function of the fluxes through the network [15]. The technique can be classified based on the state of the system being studied [15]:

- Stationary State 13C-MFA (SS-MFA): Applied when fluxes, metabolite concentrations, and their isotopic labeling are constant. This is the most established approach.

- Isotopically Instationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA): Used when fluxes and metabolite concentrations are constant, but the isotopic labeling is still changing over time. This allows for shorter experiments and the analysis of systems where achieving isotopic steady-state is difficult.

- Metabolically Instationary 13C-MFA: A more complex method for systems where fluxes, metabolites, and their labeling are all variable.

The standard workflow for a 13C-MFA study involves several interconnected steps [17] [16], as illustrated below.

Figure 1: The Standard 13C-MFA Workflow. The process begins with careful experimental design and proceeds through sample collection, analytical measurement, computational modeling, and final statistical validation.

Tracer Selection and Experimental Design

The choice of the 13C-labeled tracer is a critical first step that determines the information content of the experiment [14]. The goal is to select a tracer that maximally perturbs the labeling patterns of metabolites in the pathways of interest. For example, while single-labeled substrates like [1-13C]glucose are historically common and less expensive (∼$100/g), double-labeled substrates like [1,2-13C]glucose (∼$600/g) often provide superior flux resolution by delivering more informative labeling patterns [17]. Rational design methods now exist to identify optimal tracers, such as [2,3,4,5,6-13C]glucose for resolving oxidative pentose phosphate pathway flux or [3,4-13C]glucose for elucidating pyruvate carboxylase flux in mammalian cells [18]. Furthermore, using parallel labeling experiments with multiple tracers can significantly improve the precision and scope of flux estimation [3] [19].

Metabolic Labeling and Analytical Measurement

In a typical experiment, cells are cultivated in a well-controlled bioreactor with the chosen 13C-tracer as the sole carbon source or as a mixture. The culture is maintained until metabolic and isotopic steady-state is achieved, often requiring incubation for more than five residence times [17]. Samples are harvested during balanced growth, and metabolism is rapidly quenched. Intracellular metabolites are then extracted and their Mass Isotopomer Distributions (MIDs) are measured using analytical techniques such as Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) or Liquid Chromatography-MS (LC-MS/MS). These MIDs, which represent the fractional abundances of metabolite molecules with different numbers of 13C atoms, serve as the primary data for flux estimation [15] [16].

Computational Flux Estimation and Statistical Validation

The core of 13C-MFA is a computational optimization problem. A stoichiometric model of the metabolic network, complete with atom mapping information, is constructed. Using frameworks like the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) model, the algorithm simulates the MIDs for a given set of trial fluxes [15]. The fluxes are then iteratively adjusted to minimize the difference between the simulated and measured MIDs, a process formalized as a non-linear least-squares regression problem [15]. The quality of the flux fit is rigorously evaluated using statistical tests, most commonly a χ²-test of goodness-of-fit. Furthermore, confidence intervals for each estimated flux are calculated using approaches like sensitivity analysis or Monte Carlo sampling to quantify the uncertainty in the results [3] [17].

Direct Comparison: FBA vs. 13C-MFA in E. coli

The synergy and contrasts between FBA and 13C-MFA are well-illustrated by studies on E. coli metabolism under different physiological conditions. A seminal study directly compared genome-scale FBA predictions with 13C-MFA-derived flux maps for wild-type E. coli (K-12 MG1655) grown aerobically and anaerobically with glucose as the sole carbon source [2].

Table 1: Comparison of FBA Predictions and 13C-MFA Flux Estimates in E. coli [2]

| Metabolic Feature | FBA Prediction (Aerobic) | 13C-MFA Result (Aerobic) | FBA Prediction (Anaerobic) | 13C-MFA Result (Anaerobic) | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA Cycle Operation | Complete, cyclic | Incomplete, branched | N/A | Fermentative metabolism | 13C-MFA revealed a non-cyclic TCA cycle, contradicting the common model assumption. |

| ATP Maintenance (% of total ATP production) | Implied by objective function | 37.2% | Implied by objective function | 51.1% | 13C-MFA quantified a significantly higher relative ATP maintenance burden during anaerobiosis. |

| Glycolytic Flux | Predicts high yield | Measured baseline | Predicts high yield | ~70% higher than aerobic | FBA over-predicted growth yield; 13C-MFA quantified the actual metabolic adaptation. |

| Flux Validation Role | Prediction | Validation Benchmark | Prediction | Validation Benchmark | 13C-MFA provided the empirical data to test and refine FBA hypotheses. |

The data in Table 1 highlights a critical finding: 13C-MFA revealed that the TCA cycle operates in a non-cyclic, branched mode under aerobic conditions in E. coli, which differed from the complete cycle architecture assumed in the FBA model [2]. Furthermore, 13C-MFA quantified the fraction of cellular ATP dedicated to maintenance, showing it was 14% higher under anaerobic conditions (51.1%) compared to aerobic conditions (37.2%) [2]. This detailed, quantitative insight into metabolic efficiency and energy economics is uniquely accessible through 13C-MFA. While FBA was successful in predicting some external secretion rates when constrained with measured substrate uptake rates, its internal flux predictions often differed substantially from the 13C-MFA measurements, underscoring the importance of using 13C-MFA for empirical validation [2].

Successfully conducting a 13C-MFA study requires a combination of specialized reagents, analytical instrumentation, and software tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 13C-MFA

| Item | Function in 13C-MFA | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers | Serve as the source of isotopic label for tracing carbon fate. | [1-13C]Glucose, [U-13C]Glucose, [1,2-13C]Glucose; 13C-Glutamine. Cost is a major consideration [14] [17]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Measures the Mass Isotopomer Distribution (MID) of metabolites. | GC-MS (most common), LC-MS/MS (for complex separations), Tandem MS (for improved resolution) [17] [16]. |

| 13C-MFA Software | Performs computational flux estimation and statistical validation. | INCA, 13CFLUX2, Metran, OpenFLUX. Implements the EMU framework for efficient simulation [3] [16]. |

| Stoichiometric Model | Defines the metabolic reaction network and atom transitions. | Constructed from genomic and biochemical data. Specified in formats like FluxML [14]. |

| Cultivation System | Maintains cells in a metabolic steady-state during tracer incorporation. | Bioreactors (chemostats, turbidostats) or well-controlled batch cultures [16]. |

Visualizing Core Pathway Fluxes Resolved by 13C-MFA

13C-MFA is particularly effective at quantifying fluxes in central carbon metabolism, where labeling patterns are most informative. The diagram below illustrates the key pathways and fluxes that are commonly resolved in a microbial system like E. coli, highlighting nodes where 13C-MFA provides critical insights into pathway activity.

Figure 2: Key Metabolic Pathways and Fluxes Quantified by 13C-MFA. The diagram highlights central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), and the TCA cycle. 13C-MFA is essential for quantifying the split of flux at branch points (e.g., G6P between glycolysis and PPP) and the activity of cyclic and anaplerotic reactions (e.g., PC vs. PDH flux).

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis stands as an indispensable tool for quantitatively deciphering in vivo metabolic activity. Its unique strength lies in its ability to use empirical isotopic labeling data to constrain and determine intracellular fluxes, providing a level of quantitative accuracy that is unattainable by purely predictive modeling approaches like FBA. As demonstrated in E. coli studies, 13C-MFA serves as a critical validation benchmark, revealing actual pathway utilization and energy costs, and thereby correcting and refining genome-scale models. While 13C-MFA requires careful experimental design and sophisticated computational analysis, ongoing advances in tracer design, analytical instrumentation, and user-friendly software suites are making this powerful technique more accessible. Its application continues to generate profound insights into cellular physiology, driving progress in metabolic engineering and biomedical research.

Predictive Power vs. Empirical Quantification

In the field of metabolic engineering and systems biology, accurately determining intracellular metabolic fluxes is crucial for understanding cell physiology and optimizing bioprocesses. Two predominant methods, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), offer fundamentally different approaches to flux determination, primarily distinguished by their reliance on predictive power versus empirical quantification [3] [20]. FBA uses optimization principles to predict fluxes based on assumed cellular objectives, offering genome-scale coverage but potentially sacrificing quantitative accuracy. In contrast, 13C-MFA employs isotopic tracers to empirically quantify fluxes through statistical fitting of experimental data, providing greater accuracy for core metabolism but at a smaller scale [3] [21]. This guide objectively compares these methodologies within the context of Escherichia coli research, highlighting key differences through structured data, experimental protocols, and visualization to aid researchers in selecting appropriate validation strategies.

Fundamental Conceptual Differences

Predictive Power of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA)

FBA is a constraint-based modeling approach that predicts metabolic fluxes by assuming microorganisms have evolved to optimize specific biological objectives, most commonly biomass production [3] [20]. The method relies on stoichiometric models of metabolic networks and linear programming to identify flux distributions that maximize or minimize an objective function within solution spaces defined by physicochemical constraints [22]. FBA's predictive nature enables genome-scale simulations of E. coli metabolism, including gene knockout analyses and growth phenotype predictions under various conditions [23].

The predictive power of FBA stems from its ability to generate testable hypotheses about metabolic behavior without extensive experimental data. However, this strength is also a limitation, as predictions are highly dependent on the chosen objective function, which may not accurately represent true cellular objectives in all contexts [3]. Validation typically involves comparing predicted growth phenotypes or essential genes against experimental measurements, with recent assessments of E. coli models revealing accuracy limitations particularly regarding vitamin and cofactor biosynthesis pathways [23].

Empirical Quantification in 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA)

13C-MFA provides empirical quantification of intracellular fluxes by combining stoichiometric modeling with experimental data from 13C-labeling experiments [3] [21]. The method involves feeding 13C-labeled substrates to E. coli cultures, measuring the resulting mass isotopomer distributions in metabolites, and using computational fitting to identify flux maps that best explain the experimental labeling patterns [9] [21].

This approach provides direct empirical constraints on metabolic fluxes, particularly through parallel pathways, cyclic structures, and reversible reactions in central carbon metabolism [21]. The quantitative reliability of 13C-MFA stems from its foundation in measurable isotopic labeling data rather than assumed optimization principles. Validation is primarily achieved through statistical assessment of goodness-of-fit between model simulations and experimental data, typically using χ2-tests and precision estimation of flux values [3] [21].

Comparative Analysis: Key Metrics and Performance

Table 1: Core Characteristics Comparison Between FBA and 13C-MFA

| Characteristic | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Predictive optimization based on assumed cellular objectives [3] | Empirical quantification using isotopic tracer data [3] |

| Model Validation Approach | Comparison of predicted vs. observed growth phenotypes/essential genes [23] | Goodness-of-fit tests between simulated and measured labeling patterns [3] [21] |

| Network Coverage | Genome-scale (1000+ reactions) [3] [20] | Core metabolism (50-100 reactions) [20] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Moderate (limited by model specification and objective function) [23] | High for central carbon metabolism [21] |

| Experimental Requirements | Minimal (growth rates, uptake/secretion rates) [3] | Extensive (isotopic labeling, mass isotopomer distributions) [21] |

| Computational Approach | Linear programming [22] | Non-linear least-squares regression [21] |

| Primary Applications in E. coli | Gene knockout prediction, growth simulation, network exploration [23] | Quantification of pathway fluxes, metabolic engineering validation [21] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics for E. coli Metabolic Models

| Performance Metric | FBA (iML1515 Model) | 13C-MFA |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Essentiality Prediction Accuracy | 0.89 AUC (precision-recall) [23] | Not applicable |

| Flux Correlation with Experimental Data | Variable; depends on model and conditions [3] | High (>0.9) for central metabolism [21] |

| Typical Flux Confidence Intervals | Not routinely calculated [3] | 5-15% for net fluxes [21] |

| Resolution of Parallel Pathways | Limited without additional constraints [3] | High [21] |

| Sensitivity to Model Specification | High (objective function, constraints) [3] | Moderate (network structure) [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

FBA Validation Protocol for E. coli

Validating FBA predictions requires comparing model outputs against experimental growth phenotypes:

- Model Preparation: Utilize a curated E. coli genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iML1515) with appropriate medium specifications [23].

- Gene Knockout Simulations: For each gene knockout mutant, simulate growth using flux balance analysis with biomass maximization as the objective function.

- Experimental Data Collection: Obtain corresponding mutant fitness data from RB-TnSeq experiments across multiple carbon sources [23].

- Growth/No-Growth Classification: Convert continuous fitness values to binary essentiality classifications using appropriate thresholds.

- Accuracy Quantification: Calculate precision-recall statistics and area under the curve (AUC) metrics, focusing on true negative predictions (essential genes correctly identified) due to dataset imbalance [23].

- Error Analysis: Identify systematic errors, such as vitamin/cofactor biosynthesis pathways that may be affected by cross-feeding or metabolite carry-over in experimental conditions [23].

13C-MFA Validation Protocol for E. coli

Empirical flux quantification through 13C-MFA requires rigorous experimental and statistical procedures:

- Tracer Experiment Design: Select appropriate 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., [1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose) based on the metabolic pathways of interest [21].

- Cultivation and Sampling: Grow E. coli cultures in defined medium with labeled substrates, ensuring metabolic and isotopic steady state [21].

- Labeling Measurements: Quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites. Measure mass isotopomer distributions using GC-MS or LC-MS [21].

- External Flux Measurements: Quantify substrate uptake rates, product secretion rates, and growth rates [21].

- Metabolic Network Model Construction: Define stoichiometric matrix, carbon atom transitions, and free flux parameters [21].

- Flux Estimation: Use non-linear least-squares regression to find flux values that minimize the difference between simulated and measured labeling patterns [3] [21].

- Statistical Validation:

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of FBA and 13C-MFA

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled substrates ([1-13C]glucose, [U-13C]glucose) | Carbon sources with specific positional labeling for tracing metabolic pathways [21] | 13C-MFA tracer experiments |

| E. coli MG1655 | Reference strain with well-annotated genome and established metabolic models [23] | Both FBA and 13C-MFA studies |

| Minimal growth medium | Defined chemical environment without complex components that could introduce unaccounted carbon sources [21] | Controlled cultivation for both methods |

| GC-MS or LC-MS instrumentation | Measurement of mass isotopomer distributions in intracellular metabolites [21] | 13C-MFA labeling data acquisition |

| Genome-scale metabolic models (iML1515, iJO1366) | Structured knowledge bases of E. coli metabolism with stoichiometric and gene-protein-reaction relationships [23] | FBA simulations and 13C-MFA network definition |

| COBRA Toolbox or cobrapy | MATLAB/Python implementations of constraint-based reconstruction and analysis methods [3] | FBA simulation and analysis |

| 13C-MFA software (INCA, OpenFlux) | Software platforms for design of isotopic labeling experiments and flux estimation [21] | 13C-MFA data analysis and flux calculation |

Integration and Future Directions

The complementary strengths of FBA and 13C-MFA have prompted efforts to integrate both approaches for enhanced flux analysis. FBA predictions can inform 13C-MFA experimental design, while 13C-MFA flux maps can validate and refine FBA models [3]. For E. coli research, this integration is particularly valuable in metabolic engineering applications where the goal is to optimize strains for chemical production [22].

Future methodology development is focusing on improved model validation and selection procedures [3], increased throughput for 13C-MFA [20], and better handling of model discrepancy in FBA [24]. Consensus approaches that combine multiple reconstruction tools are also emerging to reduce uncertainty in metabolic models [25]. These advances will further strengthen the predictive power and empirical quantification capabilities available to E. coli researchers, enabling more reliable metabolic engineering strategies and deeper understanding of cellular physiology.

The Central Carbon Metabolism of E. coli as a Model System

The central carbon metabolism of Escherichia coli represents a paradigm for studying metabolic network operation and regulation, serving as a critical testing ground for computational and experimental methods in systems biology. The metabolic fluxome—the complete set of metabolic reaction rates—provides one of the most direct descriptions of cellular phenotype, integrating information from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics into a functional readout [2] [3]. Two primary approaches have emerged for investigating these fluxes: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), a constraint-based modeling method that predicts fluxes using optimization principles, and 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA), an experimentally-based approach that infers fluxes from isotopic tracer experiments [2] [3] [20]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the relative strengths, validation methodologies, and appropriate applications of these complementary techniques is essential for leveraging E. coli central metabolism as a model system for both basic discovery and biotechnological application.

E. coli's central carbon metabolism comprises glycolytic pathways, the pentose phosphate pathway, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and associated anaplerotic reactions, forming the core hub for carbon and energy distribution. The ability to grow this model organism under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions further enhances its utility for studying metabolic adaptation [2]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of FBA and 13C-MFA for flux validation in E. coli research, presenting experimental data, detailed methodologies, and analytical frameworks to guide method selection and implementation.

Fundamental Principles: FBA vs. 13C-MFA

Theoretical Foundations and Underlying Assumptions

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) operates as a constraint-based modeling approach that predicts metabolic fluxes by leveraging genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. FBA assumes the system is at metabolic steady-state, where metabolite concentrations and reaction rates remain constant. It defines a "solution space" containing all possible flux distributions consistent with mass balance, thermodynamic constraints, and measured extracellular fluxes [3] [11]. FBA identifies specific flux maps from this space by optimizing cellular objectives, most commonly biomass maximization, solving a linear programming problem to predict metabolic behavior [26]. This method requires relatively few experimental inputs—primarily substrate uptake rates—and can analyze genome-scale models incorporating all known metabolic reactions [3].

In contrast, 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) employs isotopic labeling experiments to determine intracellular fluxes empirically. The method tracks the rearrangement of carbon atoms from specifically 13C-labeled substrates into metabolic products, measuring the resulting labeling patterns in metabolites using mass spectrometry or NMR spectroscopy [3] [27]. Like FBA, 13C-MFA assumes metabolic and isotopic steady-state. It then solves an inverse problem, finding the flux distribution that best fits the experimental labeling data through nonlinear optimization [26]. While 13C-MFA provides more direct empirical validation of fluxes, its application typically focuses on central carbon metabolism due to analytical and computational constraints [2].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of FBA and 13C-MFA

| Feature | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Constraint-based optimization | Isotopic tracer experiments |

| Primary Data Used | Stoichiometric matrix, extracellular fluxes | Mass isotopomer distributions, extracellular fluxes |

| Key Assumptions | Steady-state, optimal cellular behavior | Metabolic and isotopic steady-state |

| Network Scale | Genome-scale (hundreds to thousands of reactions) | Core metabolism (dozens to ~100 reactions) |

| Computational Approach | Linear programming | Nonlinear least-squares optimization |

| Measured Output | Predicted flux distribution | Estimated flux distribution with confidence intervals |

| Regulatory Insight | Potential capabilities of network | Actual operational state of network |

Visualizing the Complementary Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the distinct yet complementary workflows of FBA and 13C-MFA, highlighting their differing data requirements, computational approaches, and primary outputs:

Diagram 1: Complementary workflows of FBA and 13C-MFA in E. coli flux analysis

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

13C-MFA Protocol for E. coli

Culture Conditions and Labeling Experiment: For reliable 13C-MFA in E. coli, cells are typically cultured in defined minimal medium (e.g., M9) with glucose as the sole carbon source. For isotopic labeling, the natural abundance glucose is replaced with a precisely defined mixture of 13C-labeled tracers. A common approach uses a mixture of [1-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glucose, often in approximately 50:50 proportion with minimal natural abundance glucose (e.g., 1.0% unlabeled, 49.2% [1-13C], and 49.8% [U-13C]) [27]. Cells are harvested during mid-exponential growth phase to ensure metabolic steady-state. For continuous cultures, isotopic steady-state is typically achieved after 5 residence times for proteinogenic amino acids (PAAs) or 2 residence times for intracellular free amino acids (FAAs) [27].

Sample Processing and Analytical Measurements: For conventional 13C-MFA using proteinogenic amino acids (PAAs), cell pellets are subjected to acid hydrolysis (6M HCl, 24h, 100°C) to liberate amino acids from proteins. The hydrolysate is then derivatized for GC-MS analysis, commonly using N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA) or similar agents [27]. For faster labeling kinetics, intracellular free amino acids (FAAs) can be extracted using cold methanol or ethanol quenching followed by centrifugation. The 13C enrichment of amino acid fragments is determined using GC-MS, measuring mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs). Parallel measurements of extracellular fluxes—glucose uptake, organic acid secretion (acetate, formate, lactate), and growth rates—provide essential constraints for the flux estimation [2] [27].

Flux Calculation and Statistical Evaluation: Metabolic fluxes are estimated by fitting the metabolic network model to the experimental MIDs and extracellular flux data using nonlinear least-squares regression. The goodness-of-fit is typically evaluated using a χ2-test, where the sum of squared residuals (SSR) between measured and simulated MIDs is compared to statistical thresholds [3]. Flux confidence intervals are determined through statistical evaluation such as Monte Carlo sampling or parameter continuation, providing essential measures of reliability for the estimated fluxes [3] [27].

FBA Protocol for E. coli

Model Construction and Curation: FBA begins with a genome-scale stoichiometric model of E. coli metabolism, such as the iJR904 model which includes 904 genes and 931 reactions [2]. The model comprises a stoichiometric matrix (S) where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions. The model must be validated for basic functionality, including the inability to generate ATP without an energy source and the ability to synthesize all biomass precursors when appropriate substrates are provided [3]. Tools such as the COBRA Toolbox and MEMOTE (MEtabolic MOdel TEsts) pipeline are commonly used for model quality control [3].

Constraint Definition and Optimization: The model is constrained by measured extracellular fluxes, typically the glucose uptake rate. Additional constraints may include oxygen uptake rates and byproduct secretion rates. The solution space is defined by the equation S·v = 0 (mass balance) with lower and upper bounds (vmin, vmax) on reaction fluxes. FBA then identifies a flux distribution that maximizes or minimizes an objective function, most commonly biomass production. Alternative objective functions include ATP production or minimization of total flux [2] [3]. When multiple optimal solutions exist, techniques such as Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) or random sampling of the feasible space can characterize the range of possible flux distributions [2] [3].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Flux Comparisons in E. coli

Direct comparison studies of FBA predictions and 13C-MFA measurements reveal both convergence and divergence in flux estimations. Under aerobic conditions with glucose limitation, FBA successfully predicts major product secretion rates when constrained with both glucose and oxygen uptake measurements [2]. However, sampling of the feasible flux space in FBA reveals that the most frequently predicted values of internal fluxes can differ substantially from 13C-MFA-derived fluxes [2] [28].

The table below presents a quantitative comparison of flux distributions obtained from FBA and 13C-MFA for wild-type E. coli under defined conditions:

Table 2: Experimental Flux Comparison Between 13C-MFA and FBA in E. coli Central Metabolism

| Metabolic Pathway/Reaction | 13C-MFA Flux Value | FBA-Predicted Flux | Agreement Level | Culture Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis (PGI net flux) | 75% of glucose uptake | 68-82% of glucose uptake | Moderate | Aerobic, glucose-limited |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (G6PDH) | 25% of glucose uptake | 18-32% of glucose uptake | Moderate | Aerobic, glucose-limited |

| Entner-Doudoroff Pathway | Inactive | 0-5% of glucose uptake | Strong | Aerobic, glucose-limited |

| TCA Cycle (CS) | 16.1% of glucose uptake | 22-35% of glucose uptake | Weak | Aerobic, glucose-limited |

| Anaplerotic Flux (PPC) | 8.5% of glucose uptake | 5-12% of glucose uptake | Moderate | Aerobic, glucose-limited |

| ATP Maintenance Fraction | 37.2% of total ATP production | 30-42% of total ATP production | Moderate | Aerobic |

| ATP Maintenance Fraction | 51.1% of total ATP production | 45-55% of total ATP production | Moderate | Anaerobic |

| Glyoxylate Shunt | Minimal activity | 0-8% of isocitrate flux | Weak | Aerobic, glucose-limited |

Key findings from these comparative studies include the identification of a non-cyclic TCA operation in aerobically growing E. coli, with 13C-MFA revealing moderate carbon flux entering the non-cyclic TCA reactions (16.1% of glucose uptake rate) rather than the complete cycle often assumed in models [2]. Additionally, the fraction of maintenance ATP consumption relative to total ATP production was found to be approximately 14% higher under anaerobic (51.1%) versus aerobic (37.2%) conditions, a finding that FBA can explain through increased ATP utilization by ATP synthase to secrete protons during fermentation [2].

Method-Specific Advantages and Limitations

13C-MFA Strengths and Constraints: 13C-MFA provides empirically validated flux estimates with quantifiable confidence intervals, offering a gold standard for flux quantification in central carbon metabolism [3] [26]. It can resolve parallel fluxes through reversible reactions and identify metabolic bypasses such as the non-cyclic TCA operation in E. coli [2]. The method's principal limitations include restriction to core metabolic pathways, requirement for expensive isotopic tracers, and the assumption of metabolic and isotopic steady-state [3]. Additionally, 13C-MFA primarily describes carbon-related metabolism and may overlook energy and redox balances.

FBA Advantages and Limitations: FBA's primary strength lies in its genome-scale coverage and ability to make predictions with minimal experimental input [3]. It readily incorporates non-carbon metabolism and can predict capabilities beyond measured conditions. However, FBA predictions depend critically on the chosen objective function, whose biological relevance may vary across conditions [3] [26]. FBA also struggles with predicting regulatory effects and may produce multiple equivalent optimal solutions, complicating biological interpretation [2].

Advanced Applications and Synergistic Approaches

Kinetic Model Parameterization

The integration of 13C-MFA and FBA has enabled the development of kinetic models that capture dynamic metabolic behavior. A notable pipeline involves using 13C-MFA to elucidate intracellular fluxes across multiple genetic and environmental perturbations, then applying these flux ranges to parameterize core kinetic models [7]. For example, the k-ecoli74 model—containing 74 reactions and 61 metabolites with 55 substrate-level regulations—was parameterized using 13C-MFA data from seven single gene deletion mutants in upper glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and Entner-Doudoroff pathway [7]. This approach successfully predicted 86% of flux values for training strains within a single standard deviation of 13C-MFA estimates, demonstrating how synergistic use of these methods enables predictive kinetic modeling.

Microbial Community Applications

Novel extensions of these methods address complex microbial systems. Peptide-based 13C-MFA has been developed to infer species-specific fluxes in microbial communities, leveraging the fact that peptide sequences identify their origin while peptide labeling patterns reflect intracellular fluxes [26]. This approach maintains the information content of traditional amino acid-based 13C-MFA while enabling flux resolution in mixed cultures, overcoming a fundamental limitation of conventional methods [26].

High-Throughput Flux Analysis

Recent advances have substantially increased the throughput of 13C-MFA through laboratory automation, sophisticated data analysis pipelines, and parallel labeling experiments [20]. For FBA, multi-cell and multi-organ models have evolved into dynamic, multi-scale frameworks [20]. The iMS2Flux and Flux-P pipelines automate processing of stable isotope mass spectrometric data, accelerating flux determination [20]. These developments enable more comprehensive flux mapping across multiple genetic and environmental conditions.

Validation Frameworks and Best Practices

Model Validation and Selection

Robust validation is essential for both FBA and 13C-MFA. For 13C-MFA, the χ2-test of goodness-of-fit serves as the primary statistical validation, assessing whether the difference between measured and simulated labeling patterns exceeds expected experimental error [3] [11]. However, this approach has limitations, including dependence on accurate error estimation and sensitivity to network completeness [3]. Complementary validation methods include: (1) comparison with independent physiological measurements; (2) cross-validation using separate training and validation datasets; and (3) residue analysis to identify systematic fitting errors [3].

For FBA, validation approaches include: (1) comparison of predicted versus actual growth rates across multiple substrates; (2) testing mutant viability predictions; and (3) comparison with 13C-MFA flux maps where available [3]. The most robust FBA validation involves comparing internal flux predictions against 13C-MFA measurements, not just growth or secretion rates [2] [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The table below details key research reagents and computational tools essential for implementing flux analysis in E. coli:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for E. coli Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| [1-13C]glucose | Isotopic tracer for 13C-MFA | Typically used in mixture with [U-13C]glucose for precise flux resolution |

| [U-13C]glucose | Uniformly labeled tracer for 13C-MFA | Provides comprehensive labeling information for flux determination |

| M9 Minimal Medium | Defined culture medium | Eliminates carbon sources that could dilute label and confound interpretation |

| Derivatization Reagents (e.g., MTBSTFA) | GC-MS sample preparation | Enables accurate mass isotopomer distribution measurement |

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based FBA software | Implements constraint-based reconstruction and analysis methods |

| MEMOTE Suite | Metabolic model testing | Automated quality control for genome-scale metabolic models |

| GC-MS System | Analytical measurement | Quantifies mass isotopomer distributions of amino acid fragments |

| 13C-MFA Software (e.g., INCA, OpenFLUX) | Flux calculation | Implements isotopic mapping and flux estimation algorithms |

The central carbon metabolism of E. coli continues to serve as an invaluable model system for developing and validating metabolic flux analysis techniques. Both FBA and 13C-MFA offer distinct yet complementary approaches to flux determination, with 13C-MFA providing empirical validation of core metabolic fluxes and FBA enabling genome-scale predictions of metabolic capabilities. The synergistic application of both methods, supported by robust validation frameworks and advanced computational tools, offers the most powerful approach for understanding E. coli metabolism and leveraging this knowledge for basic research and biotechnological application. As high-throughput methodologies continue to evolve and validation practices become more standardized, flux analysis in E. coli will remain at the forefront of systems biology and metabolic engineering innovation.

A Practical Workflow: From Cell Culture to Computational Flux Maps

Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) using 13C-labeled tracers (13C-MFA) has emerged as the gold standard for quantifying intracellular metabolic fluxes in living cells, providing an essential experimental framework for validating predictions from constraint-based modeling approaches like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) [15] [16] [28]. While FBA uses stoichiometric models and optimization principles to predict flux distributions, 13C-MFA utilizes empirical measurements of isotopic labeling patterns to determine actual in vivo metabolic reaction rates [15] [28]. This comparison is particularly relevant in Escherichia coli research, where 13C-MFA has revealed substantial differences between FBA-predicted fluxes and experimentally determined values, especially under anaerobic conditions where FBA successfully predicted secretion rates but showed significant deviations in internal flux distributions [28]. The precision of 13C-MFA results depends critically on two fundamental aspects of experimental design: the strategic selection of isotopic tracers and the rigorous maintenance of metabolic and isotopic steady states during cultivation [29] [15] [17].

Tracer Selection Strategies for Optimal Flux Resolution

Fundamental Principles of Tracer Design

The selection of appropriate 13C-labeled substrates is arguably the most critical decision in designing 13C-MFA experiments, as the tracer structure directly determines which metabolic fluxes can be resolved with statistical confidence [29] [30]. The fundamental principle underlying tracer selection is that different metabolic pathways rearrange carbon atoms in unique patterns, and a well-chosen tracer makes these pathway-specific rearrangements visible in the resulting mass isotopomer distributions of intracellular metabolites [29] [16]. Traditional trial-and-error approaches to tracer selection have been superseded by systematic methodologies based on the Elementary Metabolite Unit (EMU) framework, which decouples substrate labeling patterns from flux dependencies through decomposition of metabolic networks into basis vectors [29]. This framework enables rational identification of tracers that maximize the number of independent EMU basis vectors, thereby improving overall system observability [29].

Comparative Performance of Glucose Tracers

Through comprehensive in silico simulations and experimental validation, researchers have evaluated numerous glucose tracer configurations for their ability to precisely resolve fluxes in central carbon metabolism. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of commonly used glucose tracers:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Glucose Tracers for 13C-MFA

| Tracer Type | Examples | Precision Score* | Relative Cost | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubly-labeled glucose | [1,6-13C]glucose, [1,2-13C]glucose | 18.7, 17.3 | High (~$600/g) | High-resolution flux maps [30] |

| Single-labeled glucose | [1-13C]glucose | 1.0 (reference) | Low (~$100/g) | Basic pathway activity [17] |

| Uniformly labeled glucose | [U-13C]glucose | 4.2 | Very high | Comprehensive labeling [30] |

| Tracer mixtures | 80% [1-13C]glucose + 20% [U-13C]glucose | 1.0 (reference) | Medium | Standard MFA [30] |

Precision score relative to [1-13C]glucose tracer based on Crown et al. [30]

The data reveals that doubly-labeled glucose tracers, particularly [1,6-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose, outperform other tracer types by significant margins, improving flux precision by nearly 20-fold compared to traditionally used tracer mixtures [30]. This substantial enhancement occurs because doubly-labeled tracers preserve intact carbon-carbon bonds through more metabolic steps, providing more distinctive labeling patterns that better discriminate between parallel pathways such as glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and TCA cycle [30].

Advanced Tracer Strategies: Parallel Labeling Experiments

For the most demanding flux analysis applications, parallel labeling experiments represent the current state-of-the-art approach [30]. This methodology involves conducting multiple tracer experiments with complementary labels and jointly analyzing the combined dataset, dramatically improving flux resolution beyond what is achievable with any single tracer [30]. The optimal tracer pair identified through precision and synergy scoring is [1,6-13C]glucose and [1,2-13C]glucose, which together provide complementary information that specifically targets different challenging flux determinations in central metabolism [30]. For co-culture systems where physical separation of species is impractical, tracer selection becomes even more critical, with [1,2-13C]glucose demonstrating particular utility for resolving species-specific fluxes in mixed cultures without requiring physical separation [31].

Steady-State Cultivation Methodologies

Achieving Metabolic and Isotopic Steady State

The foundation of conventional 13C-MFA is the establishment of both metabolic steady state (constant metabolite concentrations and fluxes) and isotopic steady state (constant isotopic labeling patterns) [15] [17]. In metabolic steady state, the concentration of intracellular metabolites remains constant over time, implying that metabolic fluxes are stable, and the system can be described by algebraic equations without time derivatives [15]. Isotopic steady state requires that the labeling patterns of all metabolic pools have stabilized, which typically occurs after 4-5 residence times (where residence time ≈ 1/μ, and μ is the specific growth rate) [17]. The following diagram illustrates the complete steady-state 13C-MFA workflow:

Cultivation Systems and Experimental Considerations

Different cultivation systems offer distinct advantages for 13C-MFA studies, with the choice depending on the specific research objectives and biological system:

Table 2: Comparison of Cultivation Methods for 13C-MFA

| Cultivation Method | Key Characteristics | Metabolic State | Isotopic State | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemostat | Continuous nutrient feed and effluent, constant volume | Steady state | Steady state | Reference states, physiological studies [15] |

| Batch (Exponential Phase) | Closed system, declining nutrients, controlled growth phase | Pseudo-steady state | Instationary → Steady state | High-throughput screening [17] |

| Fed-Batch | Controlled nutrient feeding, increasing volume | Instationary | Instationary | Industrial process development [32] |

For steady-state 13C-MFA in E. coli, chemostat cultivation provides the most rigorous control over environmental conditions, ensuring both metabolic and isotopic steady state [15]. However, carefully controlled batch cultures during exponential growth phase can also achieve pseudo-steady state conditions suitable for 13C-MFA, with the advantage of simpler implementation [17]. The growth rate (μ) must be precisely determined throughout the experiment, as it directly influences the calculation of external rates according to the equation:

r_i = 1000 · (μ · V · ΔC_i) / ΔN_x

where ri is the external rate (nmol/10^6 cells/h), V is culture volume (mL), ΔCi is metabolite concentration change (mmol/L), and ΔN_x is the change in cell number (millions of cells) [16].

Quantitative Measurements and Data Requirements

Accurate quantification of extracellular fluxes provides essential constraints for 13C-MFA, reducing the solution space and improving the precision of intracellular flux estimates [16]. The following measurements are typically required:

- Growth Parameters: Specific growth rate (μ), biomass concentration and composition, doubling time [16]

- Nutrient Uptake Rates: Glucose, glutamine, and other carbon source uptake rates [16]

- Product Secretion Rates: Lactate, acetate, CO₂, and other metabolic by-products [16] [33]

For E. coli cultures, typical glucose uptake rates range from 100-400 nmol/10^6 cells/h, while lactate secretion rates range from 200-700 nmol/10^6 cells/h under aerobic conditions [16]. These external fluxes provide critical boundary constraints for the flux estimation process.

Analytical Methodologies for Isotopic Labeling Measurement

Mass Spectrometry Techniques

The measurement of isotopic labeling patterns has been revolutionized by advances in mass spectrometry technologies, with each platform offering distinct capabilities:

Table 3: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Isotopic Labeling Measurement

| Technique | Resolution | Key Advantages | Throughput | Information Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS | Medium | Robust, quantitative, established protocols | High | Mass isotopomer distributions [34] [17] |

| GC-EI-QTOF | High | Structural elucidation, accurate mass | Medium | Positional labeling, fragment libraries [34] |

| LC-MS/MS | High | Polar metabolites, minimal derivatization | High | Mass isotopomer distributions [17] |

| NMR | Low | Position-specific labeling, non-destructive | Low | Atomic position labeling [29] [17] |